- Manuscript Preparation

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

- 4 minute read

- 11.3K views

Table of Contents

The discussion section in scientific manuscripts might be the last few paragraphs, but its role goes far beyond wrapping up. It’s the part of an article where scientists talk about what they found and what it means, where raw data turns into meaningful insights. Therefore, discussion is a vital component of the article.

An excellent discussion is well-organized. We bring to you authors a classic 6-step method for writing discussion sections, with examples to illustrate the functions and specific writing logic of each step. Take a look at how you can impress journal reviewers with a concise and focused discussion section!

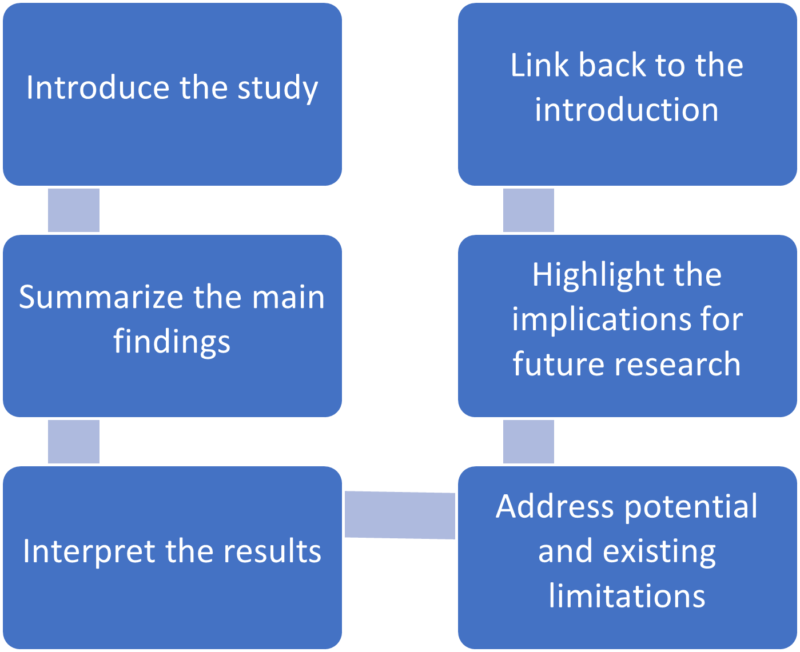

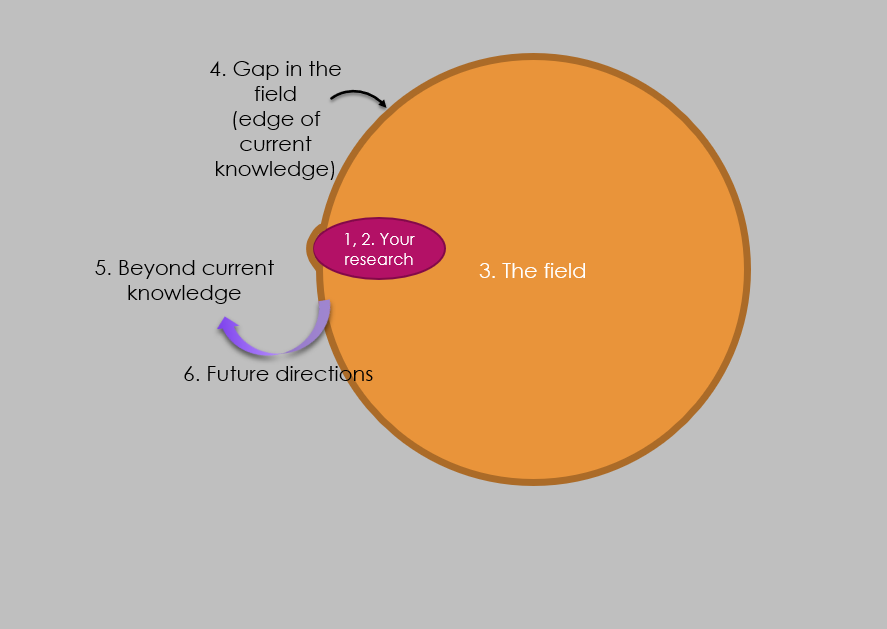

Discussion frame structure

Conventionally, a discussion section has three parts: an introductory paragraph, a few intermediate paragraphs, and a conclusion¹. Please follow the steps below:

1.Introduction—mention gaps in previous research¹⁻ ²

Here, you orient the reader to your study. In the first paragraph, it is advisable to mention the research gap your paper addresses.

Example: This study investigated the cognitive effects of a meat-only diet on adults. While earlier studies have explored the impact of a carnivorous diet on physical attributes and agility, they have not explicitly addressed its influence on cognitively intense tasks involving memory and reasoning.

2. Summarizing key findings—let your data speak ¹⁻ ²

After you have laid out the context for your study, recapitulate some of its key findings. Also, highlight key data and evidence supporting these findings.

Example: We found that risk-taking behavior among teenagers correlates with their tendency to invest in cryptocurrencies. Risk takers in this study, as measured by the Cambridge Gambling Task, tended to have an inordinately higher proportion of their savings invested as crypto coins.

3. Interpreting results—compare with other papers¹⁻²

Here, you must analyze and interpret any results concerning the research question or hypothesis. How do the key findings of your study help verify or disprove the hypothesis? What practical relevance does your discovery have?

Example: Our study suggests that higher daily caffeine intake is not associated with poor performance in major sporting events. Athletes may benefit from the cardiovascular benefits of daily caffeine intake without adversely impacting performance.

Remember, unlike the results section, the discussion ideally focuses on locating your findings in the larger body of existing research. Hence, compare your results with those of other peer-reviewed papers.

Example: Although Miller et al. (2020) found evidence of such political bias in a multicultural population, our findings suggest that the bias is weak or virtually non-existent among politically active citizens.

4. Addressing limitations—their potential impact on the results¹⁻²

Discuss the potential impact of limitations on the results. Most studies have limitations, and it is crucial to acknowledge them in the intermediary paragraphs of the discussion section. Limitations may include low sample size, suspected interference or noise in data, low effect size, etc.

Example: This study explored a comprehensive list of adverse effects associated with the novel drug ‘X’. However, long-term studies may be needed to confirm its safety, especially regarding major cardiac events.

5. Implications for future research—how to explore further¹⁻²

Locate areas of your research where more investigation is needed. Concluding paragraphs of the discussion can explain what research will likely confirm your results or identify knowledge gaps your study left unaddressed.

Example: Our study demonstrates that roads paved with the plastic-infused compound ‘Y’ are more resilient than asphalt. Future studies may explore economically feasible ways of producing compound Y in bulk.

6. Conclusion—summarize content¹⁻²

A good way to wind up the discussion section is by revisiting the research question mentioned in your introduction. Sign off by expressing the main findings of your study.

Example: Recent observations suggest that the fish ‘Z’ is moving upriver in many parts of the Amazon basin. Our findings provide conclusive evidence that this phenomenon is associated with rising sea levels and climate change, not due to elevated numbers of invasive predators.

A rigorous and concise discussion section is one of the keys to achieving an excellent paper. It serves as a critical platform for researchers to interpret and connect their findings with the broader scientific context. By detailing the results, carefully comparing them with existing research, and explaining the limitations of this study, you can effectively help reviewers and readers understand the entire research article more comprehensively and deeply¹⁻² , thereby helping your manuscript to be successfully published and gain wider dissemination.

In addition to keeping this writing guide, you can also use Elsevier Language Services to improve the quality of your paper more deeply and comprehensively. We have a professional editing team covering multiple disciplines. With our profound disciplinary background and rich polishing experience, we can significantly optimize all paper modules including the discussion, effectively improve the fluency and rigor of your articles, and make your scientific research results consistent, with its value reflected more clearly. We are always committed to ensuring the quality of papers according to the standards of top journals, improving the publishing efficiency of scientific researchers, and helping you on the road to academic success. Check us out here !

Type in wordcount for Standard Total: USD EUR JPY Follow this link if your manuscript is longer than 12,000 words. Upload

References:

- Masic, I. (2018). How to write an efficient discussion? Medical Archives , 72(3), 306. https://doi.org/10.5455/medarh.2018.72.306-307

- Şanlı, Ö., Erdem, S., & Tefik, T. (2014). How to write a discussion section? Urology Research & Practice , 39(1), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.5152/tud.2013.049

- Manuscript Review

Navigating “Chinglish” Errors in Academic English Writing

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

You may also like.

Page-Turner Articles are More Than Just Good Arguments: Be Mindful of Tone and Structure!

A Must-see for Researchers! How to Ensure Inclusivity in Your Scientific Writing

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 8. The Discussion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The purpose of the discussion section is to interpret and describe the significance of your findings in relation to what was already known about the research problem being investigated and to explain any new understanding or insights that emerged as a result of your research. The discussion will always connect to the introduction by way of the research questions or hypotheses you posed and the literature you reviewed, but the discussion does not simply repeat or rearrange the first parts of your paper; the discussion clearly explains how your study advanced the reader's understanding of the research problem from where you left them at the end of your review of prior research.

Annesley, Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Peacock, Matthew. “Communicative Moves in the Discussion Section of Research Articles.” System 30 (December 2002): 479-497.

Importance of a Good Discussion

The discussion section is often considered the most important part of your research paper because it:

- Most effectively demonstrates your ability as a researcher to think critically about an issue, to develop creative solutions to problems based upon a logical synthesis of the findings, and to formulate a deeper, more profound understanding of the research problem under investigation;

- Presents the underlying meaning of your research, notes possible implications in other areas of study, and explores possible improvements that can be made in order to further develop the concerns of your research;

- Highlights the importance of your study and how it can contribute to understanding the research problem within the field of study;

- Presents how the findings from your study revealed and helped fill gaps in the literature that had not been previously exposed or adequately described; and,

- Engages the reader in thinking critically about issues based on an evidence-based interpretation of findings; it is not governed strictly by objective reporting of information.

Annesley Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Bitchener, John and Helen Basturkmen. “Perceptions of the Difficulties of Postgraduate L2 Thesis Students Writing the Discussion Section.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 5 (January 2006): 4-18; Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

These are the general rules you should adopt when composing your discussion of the results :

- Do not be verbose or repetitive; be concise and make your points clearly

- Avoid the use of jargon or undefined technical language

- Follow a logical stream of thought; in general, interpret and discuss the significance of your findings in the same sequence you described them in your results section [a notable exception is to begin by highlighting an unexpected result or a finding that can grab the reader's attention]

- Use the present verb tense, especially for established facts; however, refer to specific works or prior studies in the past tense

- If needed, use subheadings to help organize your discussion or to categorize your interpretations into themes

II. The Content

The content of the discussion section of your paper most often includes :

- Explanation of results : Comment on whether or not the results were expected for each set of findings; go into greater depth to explain findings that were unexpected or especially profound. If appropriate, note any unusual or unanticipated patterns or trends that emerged from your results and explain their meaning in relation to the research problem.

- References to previous research : Either compare your results with the findings from other studies or use the studies to support a claim. This can include re-visiting key sources already cited in your literature review section, or, save them to cite later in the discussion section if they are more important to compare with your results instead of being a part of the general literature review of prior research used to provide context and background information. Note that you can make this decision to highlight specific studies after you have begun writing the discussion section.

- Deduction : A claim for how the results can be applied more generally. For example, describing lessons learned, proposing recommendations that can help improve a situation, or highlighting best practices.

- Hypothesis : A more general claim or possible conclusion arising from the results [which may be proved or disproved in subsequent research]. This can be framed as new research questions that emerged as a consequence of your analysis.

III. Organization and Structure

Keep the following sequential points in mind as you organize and write the discussion section of your paper:

- Think of your discussion as an inverted pyramid. Organize the discussion from the general to the specific, linking your findings to the literature, then to theory, then to practice [if appropriate].

- Use the same key terms, narrative style, and verb tense [present] that you used when describing the research problem in your introduction.

- Begin by briefly re-stating the research problem you were investigating and answer all of the research questions underpinning the problem that you posed in the introduction.

- Describe the patterns, principles, and relationships shown by each major findings and place them in proper perspective. The sequence of this information is important; first state the answer, then the relevant results, then cite the work of others. If appropriate, refer the reader to a figure or table to help enhance the interpretation of the data [either within the text or as an appendix].

- Regardless of where it's mentioned, a good discussion section includes analysis of any unexpected findings. This part of the discussion should begin with a description of the unanticipated finding, followed by a brief interpretation as to why you believe it appeared and, if necessary, its possible significance in relation to the overall study. If more than one unexpected finding emerged during the study, describe each of them in the order they appeared as you gathered or analyzed the data. As noted, the exception to discussing findings in the same order you described them in the results section would be to begin by highlighting the implications of a particularly unexpected or significant finding that emerged from the study, followed by a discussion of the remaining findings.

- Before concluding the discussion, identify potential limitations and weaknesses if you do not plan to do so in the conclusion of the paper. Comment on their relative importance in relation to your overall interpretation of the results and, if necessary, note how they may affect the validity of your findings. Avoid using an apologetic tone; however, be honest and self-critical [e.g., in retrospect, had you included a particular question in a survey instrument, additional data could have been revealed].

- The discussion section should end with a concise summary of the principal implications of the findings regardless of their significance. Give a brief explanation about why you believe the findings and conclusions of your study are important and how they support broader knowledge or understanding of the research problem. This can be followed by any recommendations for further research. However, do not offer recommendations which could have been easily addressed within the study. This would demonstrate to the reader that you have inadequately examined and interpreted the data.

IV. Overall Objectives

The objectives of your discussion section should include the following: I. Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings

Briefly reiterate the research problem or problems you are investigating and the methods you used to investigate them, then move quickly to describe the major findings of the study. You should write a direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results, usually in one paragraph.

II. Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important

No one has thought as long and hard about your study as you have. Systematically explain the underlying meaning of your findings and state why you believe they are significant. After reading the discussion section, you want the reader to think critically about the results and why they are important. You don’t want to force the reader to go through the paper multiple times to figure out what it all means. If applicable, begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most significant or unanticipated finding first, then systematically review each finding. Otherwise, follow the general order you reported the findings presented in the results section.

III. Relate the Findings to Similar Studies

No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for your research. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps to support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your study differs from other research about the topic. Note that any significant or unanticipated finding is often because there was no prior research to indicate the finding could occur. If there is prior research to indicate this, you need to explain why it was significant or unanticipated. IV. Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings

It is important to remember that the purpose of research in the social sciences is to discover and not to prove . When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations for the study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. This is especially important when describing the discovery of significant or unanticipated findings.

V. Acknowledge the Study’s Limitations

It is far better for you to identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor! Note any unanswered questions or issues your study could not address and describe the generalizability of your results to other situations. If a limitation is applicable to the method chosen to gather information, then describe in detail the problems you encountered and why. VI. Make Suggestions for Further Research

You may choose to conclude the discussion section by making suggestions for further research [as opposed to offering suggestions in the conclusion of your paper]. Although your study can offer important insights about the research problem, this is where you can address other questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or highlight hidden issues that were revealed as a result of conducting your research. You should frame your suggestions by linking the need for further research to the limitations of your study [e.g., in future studies, the survey instrument should include more questions that ask..."] or linking to critical issues revealed from the data that were not considered initially in your research.

NOTE: Besides the literature review section, the preponderance of references to sources is usually found in the discussion section . A few historical references may be helpful for perspective, but most of the references should be relatively recent and included to aid in the interpretation of your results, to support the significance of a finding, and/or to place a finding within a particular context. If a study that you cited does not support your findings, don't ignore it--clearly explain why your research findings differ from theirs.

V. Problems to Avoid

- Do not waste time restating your results . Should you need to remind the reader of a finding to be discussed, use "bridge sentences" that relate the result to the interpretation. An example would be: “In the case of determining available housing to single women with children in rural areas of Texas, the findings suggest that access to good schools is important...," then move on to further explaining this finding and its implications.

- As noted, recommendations for further research can be included in either the discussion or conclusion of your paper, but do not repeat your recommendations in the both sections. Think about the overall narrative flow of your paper to determine where best to locate this information. However, if your findings raise a lot of new questions or issues, consider including suggestions for further research in the discussion section.

- Do not introduce new results in the discussion section. Be wary of mistaking the reiteration of a specific finding for an interpretation because it may confuse the reader. The description of findings [results section] and the interpretation of their significance [discussion section] should be distinct parts of your paper. If you choose to combine the results section and the discussion section into a single narrative, you must be clear in how you report the information discovered and your own interpretation of each finding. This approach is not recommended if you lack experience writing college-level research papers.

- Use of the first person pronoun is generally acceptable. Using first person singular pronouns can help emphasize a point or illustrate a contrasting finding. However, keep in mind that too much use of the first person can actually distract the reader from the main points [i.e., I know you're telling me this--just tell me!].

Analyzing vs. Summarizing. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University; Discussion. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Hess, Dean R. "How to Write an Effective Discussion." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004); Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sauaia, A. et al. "The Anatomy of an Article: The Discussion Section: "How Does the Article I Read Today Change What I Will Recommend to my Patients Tomorrow?” The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 74 (June 2013): 1599-1602; Research Limitations & Future Research . Lund Research Ltd., 2012; Summary: Using it Wisely. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Discussion. Writing in Psychology course syllabus. University of Florida; Yellin, Linda L. A Sociology Writer's Guide . Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2009.

Writing Tip

Don’t Over-Interpret the Results!

Interpretation is a subjective exercise. As such, you should always approach the selection and interpretation of your findings introspectively and to think critically about the possibility of judgmental biases unintentionally entering into discussions about the significance of your work. With this in mind, be careful that you do not read more into the findings than can be supported by the evidence you have gathered. Remember that the data are the data: nothing more, nothing less.

MacCoun, Robert J. "Biases in the Interpretation and Use of Research Results." Annual Review of Psychology 49 (February 1998): 259-287; Ward, Paulet al, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Expertise . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Write Two Results Sections!

One of the most common mistakes that you can make when discussing the results of your study is to present a superficial interpretation of the findings that more or less re-states the results section of your paper. Obviously, you must refer to your results when discussing them, but focus on the interpretation of those results and their significance in relation to the research problem, not the data itself.

Azar, Beth. "Discussing Your Findings." American Psychological Association gradPSYCH Magazine (January 2006).

Yet Another Writing Tip

Avoid Unwarranted Speculation!

The discussion section should remain focused on the findings of your study. For example, if the purpose of your research was to measure the impact of foreign aid on increasing access to education among disadvantaged children in Bangladesh, it would not be appropriate to speculate about how your findings might apply to populations in other countries without drawing from existing studies to support your claim or if analysis of other countries was not a part of your original research design. If you feel compelled to speculate, do so in the form of describing possible implications or explaining possible impacts. Be certain that you clearly identify your comments as speculation or as a suggestion for where further research is needed. Sometimes your professor will encourage you to expand your discussion of the results in this way, while others don’t care what your opinion is beyond your effort to interpret the data in relation to the research problem.

- << Previous: Using Non-Textual Elements

- Next: Limitations of the Study >>

- Last Updated: May 25, 2024 4:09 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

What makes an effective discussion?

When you’re ready to write your discussion, you’ve already introduced the purpose of your study and provided an in-depth description of the methodology. The discussion informs readers about the larger implications of your study based on the results. Highlighting these implications while not overstating the findings can be challenging, especially when you’re submitting to a journal that selects articles based on novelty or potential impact. Regardless of what journal you are submitting to, the discussion section always serves the same purpose: concluding what your study results actually mean.

A successful discussion section puts your findings in context. It should include:

- the results of your research,

- a discussion of related research, and

- a comparison between your results and initial hypothesis.

Tip: Not all journals share the same naming conventions.

You can apply the advice in this article to the conclusion, results or discussion sections of your manuscript.

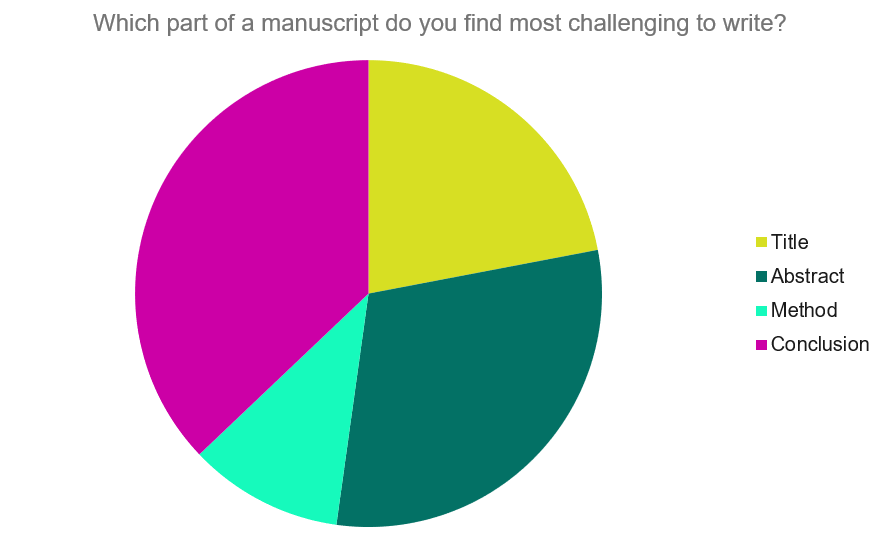

Our Early Career Researcher community tells us that the conclusion is often considered the most difficult aspect of a manuscript to write. To help, this guide provides questions to ask yourself, a basic structure to model your discussion off of and examples from published manuscripts.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Was my hypothesis correct?

- If my hypothesis is partially correct or entirely different, what can be learned from the results?

- How do the conclusions reshape or add onto the existing knowledge in the field? What does previous research say about the topic?

- Why are the results important or relevant to your audience? Do they add further evidence to a scientific consensus or disprove prior studies?

- How can future research build on these observations? What are the key experiments that must be done?

- What is the “take-home” message you want your reader to leave with?

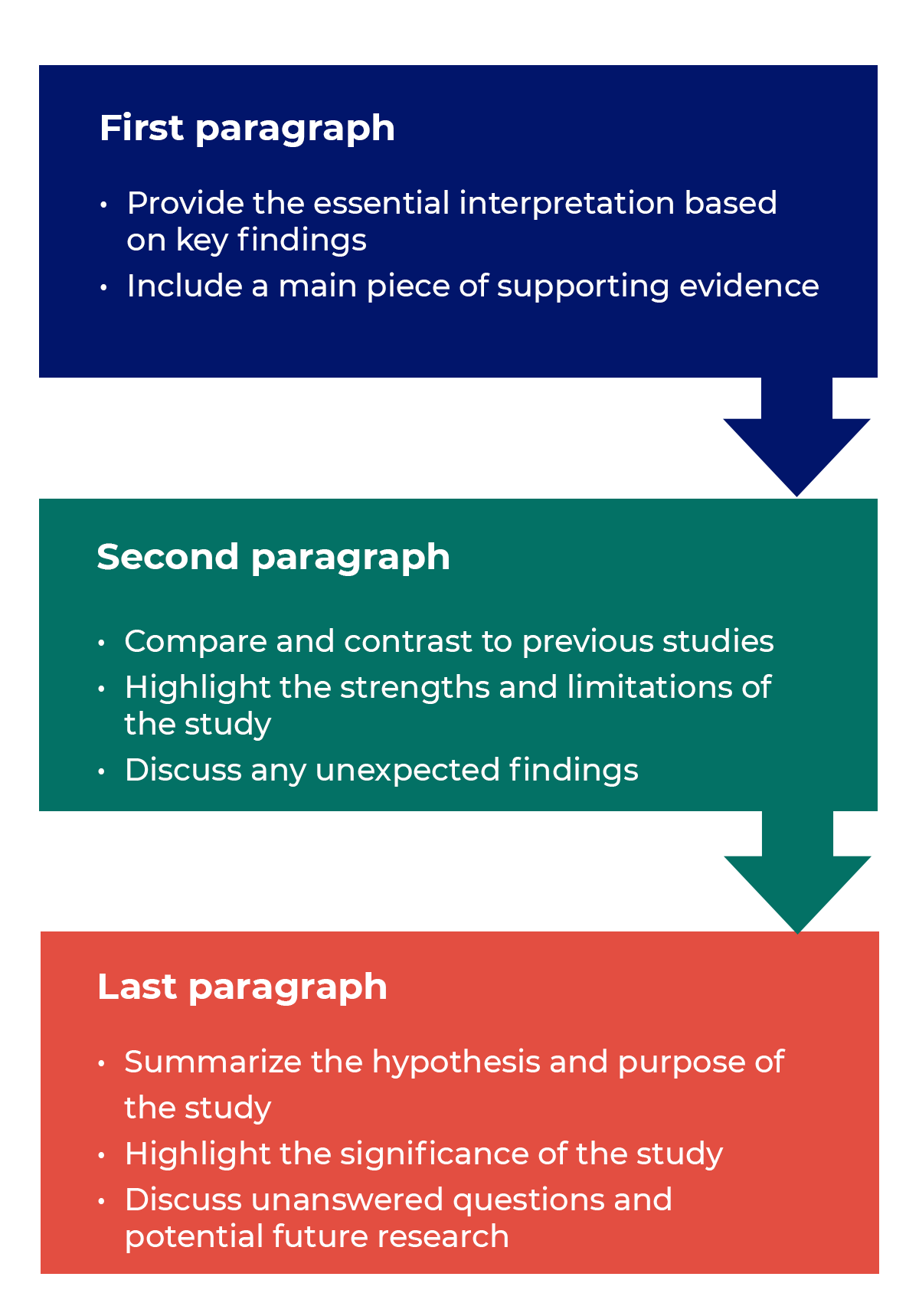

How to structure a discussion

Trying to fit a complete discussion into a single paragraph can add unnecessary stress to the writing process. If possible, you’ll want to give yourself two or three paragraphs to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of your study as a whole. Here’s one way to structure an effective discussion:

Writing Tips

While the above sections can help you brainstorm and structure your discussion, there are many common mistakes that writers revert to when having difficulties with their paper. Writing a discussion can be a delicate balance between summarizing your results, providing proper context for your research and avoiding introducing new information. Remember that your paper should be both confident and honest about the results!

- Read the journal’s guidelines on the discussion and conclusion sections. If possible, learn about the guidelines before writing the discussion to ensure you’re writing to meet their expectations.

- Begin with a clear statement of the principal findings. This will reinforce the main take-away for the reader and set up the rest of the discussion.

- Explain why the outcomes of your study are important to the reader. Discuss the implications of your findings realistically based on previous literature, highlighting both the strengths and limitations of the research.

- State whether the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was disproved, what might be the reasons?

- Introduce new or expanded ways to think about the research question. Indicate what next steps can be taken to further pursue any unresolved questions.

- If dealing with a contemporary or ongoing problem, such as climate change, discuss possible consequences if the problem is avoided.

- Be concise. Adding unnecessary detail can distract from the main findings.

Don’t

- Rewrite your abstract. Statements with “we investigated” or “we studied” generally do not belong in the discussion.

- Include new arguments or evidence not previously discussed. Necessary information and evidence should be introduced in the main body of the paper.

- Apologize. Even if your research contains significant limitations, don’t undermine your authority by including statements that doubt your methodology or execution.

- Shy away from speaking on limitations or negative results. Including limitations and negative results will give readers a complete understanding of the presented research. Potential limitations include sources of potential bias, threats to internal or external validity, barriers to implementing an intervention and other issues inherent to the study design.

- Overstate the importance of your findings. Making grand statements about how a study will fully resolve large questions can lead readers to doubt the success of the research.

Snippets of Effective Discussions:

Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach

Identifying reliable indicators of fitness in polar bears

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

How to Write the Discussion Section of a Research Paper

The discussion section of a research paper analyzes and interprets the findings, provides context, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future research directions.

Updated on September 15, 2023

Structure your discussion section right, and you’ll be cited more often while doing a greater service to the scientific community. So, what actually goes into the discussion section? And how do you write it?

The discussion section of your research paper is where you let the reader know how your study is positioned in the literature, what to take away from your paper, and how your work helps them. It can also include your conclusions and suggestions for future studies.

First, we’ll define all the parts of your discussion paper, and then look into how to write a strong, effective discussion section for your paper or manuscript.

Discussion section: what is it, what it does

The discussion section comes later in your paper, following the introduction, methods, and results. The discussion sets up your study’s conclusions. Its main goals are to present, interpret, and provide a context for your results.

What is it?

The discussion section provides an analysis and interpretation of the findings, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future directions for research.

This section combines information from the preceding parts of your paper into a coherent story. By this point, the reader already knows why you did your study (introduction), how you did it (methods), and what happened (results). In the discussion, you’ll help the reader connect the ideas from these sections.

Why is it necessary?

The discussion provides context and interpretations for the results. It also answers the questions posed in the introduction. While the results section describes your findings, the discussion explains what they say. This is also where you can describe the impact or implications of your research.

Adds context for your results

Most research studies aim to answer a question, replicate a finding, or address limitations in the literature. These goals are first described in the introduction. However, in the discussion section, the author can refer back to them to explain how the study's objective was achieved.

Shows what your results actually mean and real-world implications

The discussion can also describe the effect of your findings on research or practice. How are your results significant for readers, other researchers, or policymakers?

What to include in your discussion (in the correct order)

A complete and effective discussion section should at least touch on the points described below.

Summary of key findings

The discussion should begin with a brief factual summary of the results. Concisely overview the main results you obtained.

Begin with key findings with supporting evidence

Your results section described a list of findings, but what message do they send when you look at them all together?

Your findings were detailed in the results section, so there’s no need to repeat them here, but do provide at least a few highlights. This will help refresh the reader’s memory and help them focus on the big picture.

Read the first paragraph of the discussion section in this article (PDF) for an example of how to start this part of your paper. Notice how the authors break down their results and follow each description sentence with an explanation of why each finding is relevant.

State clearly and concisely

Following a clear and direct writing style is especially important in the discussion section. After all, this is where you will make some of the most impactful points in your paper. While the results section often contains technical vocabulary, such as statistical terms, the discussion section lets you describe your findings more clearly.

Interpretation of results

Once you’ve given your reader an overview of your results, you need to interpret those results. In other words, what do your results mean? Discuss the findings’ implications and significance in relation to your research question or hypothesis.

Analyze and interpret your findings

Look into your findings and explore what’s behind them or what may have caused them. If your introduction cited theories or studies that could explain your findings, use these sources as a basis to discuss your results.

For example, look at the second paragraph in the discussion section of this article on waggling honey bees. Here, the authors explore their results based on information from the literature.

Unexpected or contradictory results

Sometimes, your findings are not what you expect. Here’s where you describe this and try to find a reason for it. Could it be because of the method you used? Does it have something to do with the variables analyzed? Comparing your methods with those of other similar studies can help with this task.

Context and comparison with previous work

Refer to related studies to place your research in a larger context and the literature. Compare and contrast your findings with existing literature, highlighting similarities, differences, and/or contradictions.

How your work compares or contrasts with previous work

Studies with similar findings to yours can be cited to show the strength of your findings. Information from these studies can also be used to help explain your results. Differences between your findings and others in the literature can also be discussed here.

How to divide this section into subsections

If you have more than one objective in your study or many key findings, you can dedicate a separate section to each of these. Here’s an example of this approach. You can see that the discussion section is divided into topics and even has a separate heading for each of them.

Limitations

Many journals require you to include the limitations of your study in the discussion. Even if they don’t, there are good reasons to mention these in your paper.

Why limitations don’t have a negative connotation

A study’s limitations are points to be improved upon in future research. While some of these may be flaws in your method, many may be due to factors you couldn’t predict.

Examples include time constraints or small sample sizes. Pointing this out will help future researchers avoid or address these issues. This part of the discussion can also include any attempts you have made to reduce the impact of these limitations, as in this study .

How limitations add to a researcher's credibility

Pointing out the limitations of your study demonstrates transparency. It also shows that you know your methods well and can conduct a critical assessment of them.

Implications and significance

The final paragraph of the discussion section should contain the take-home messages for your study. It can also cite the “strong points” of your study, to contrast with the limitations section.

Restate your hypothesis

Remind the reader what your hypothesis was before you conducted the study.

How was it proven or disproven?

Identify your main findings and describe how they relate to your hypothesis.

How your results contribute to the literature

Were you able to answer your research question? Or address a gap in the literature?

Future implications of your research

Describe the impact that your results may have on the topic of study. Your results may show, for instance, that there are still limitations in the literature for future studies to address. There may be a need for studies that extend your findings in a specific way. You also may need additional research to corroborate your findings.

Sample discussion section

This fictitious example covers all the aspects discussed above. Your actual discussion section will probably be much longer, but you can read this to get an idea of everything your discussion should cover.

Our results showed that the presence of cats in a household is associated with higher levels of perceived happiness by its human occupants. These findings support our hypothesis and demonstrate the association between pet ownership and well-being.

The present findings align with those of Bao and Schreer (2016) and Hardie et al. (2023), who observed greater life satisfaction in pet owners relative to non-owners. Although the present study did not directly evaluate life satisfaction, this factor may explain the association between happiness and cat ownership observed in our sample.

Our findings must be interpreted in light of some limitations, such as the focus on cat ownership only rather than pets as a whole. This may limit the generalizability of our results.

Nevertheless, this study had several strengths. These include its strict exclusion criteria and use of a standardized assessment instrument to investigate the relationships between pets and owners. These attributes bolster the accuracy of our results and reduce the influence of confounding factors, increasing the strength of our conclusions. Future studies may examine the factors that mediate the association between pet ownership and happiness to better comprehend this phenomenon.

This brief discussion begins with a quick summary of the results and hypothesis. The next paragraph cites previous research and compares its findings to those of this study. Information from previous studies is also used to help interpret the findings. After discussing the results of the study, some limitations are pointed out. The paper also explains why these limitations may influence the interpretation of results. Then, final conclusions are drawn based on the study, and directions for future research are suggested.

How to make your discussion flow naturally

If you find writing in scientific English challenging, the discussion and conclusions are often the hardest parts of the paper to write. That’s because you’re not just listing up studies, methods, and outcomes. You’re actually expressing your thoughts and interpretations in words.

- How formal should it be?

- What words should you use, or not use?

- How do you meet strict word limits, or make it longer and more informative?

Always give it your best, but sometimes a helping hand can, well, help. Getting a professional edit can help clarify your work’s importance while improving the English used to explain it. When readers know the value of your work, they’ll cite it. We’ll assign your study to an expert editor knowledgeable in your area of research. Their work will clarify your discussion, helping it to tell your story. Find out more about AJE Editing.

Adam Goulston, PsyD, MS, MBA, MISD, ELS

Science Marketing Consultant

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Discussion Section for a Research Paper

We’ve talked about several useful writing tips that authors should consider while drafting or editing their research papers. In particular, we’ve focused on figures and legends , as well as the Introduction , Methods , and Results . Now that we’ve addressed the more technical portions of your journal manuscript, let’s turn to the analytical segments of your research article. In this article, we’ll provide tips on how to write a strong Discussion section that best portrays the significance of your research contributions.

What is the Discussion section of a research paper?

In a nutshell, your Discussion fulfills the promise you made to readers in your Introduction . At the beginning of your paper, you tell us why we should care about your research. You then guide us through a series of intricate images and graphs that capture all the relevant data you collected during your research. We may be dazzled and impressed at first, but none of that matters if you deliver an anti-climactic conclusion in the Discussion section!

Are you feeling pressured? Don’t worry. To be honest, you will edit the Discussion section of your manuscript numerous times. After all, in as little as one to two paragraphs ( Nature ‘s suggestion based on their 3,000-word main body text limit), you have to explain how your research moves us from point A (issues you raise in the Introduction) to point B (our new understanding of these matters). You must also recommend how we might get to point C (i.e., identify what you think is the next direction for research in this field). That’s a lot to say in two paragraphs!

So, how do you do that? Let’s take a closer look.

What should I include in the Discussion section?

As we stated above, the goal of your Discussion section is to answer the questions you raise in your Introduction by using the results you collected during your research . The content you include in the Discussions segment should include the following information:

- Remind us why we should be interested in this research project.

- Describe the nature of the knowledge gap you were trying to fill using the results of your study.

- Don’t repeat your Introduction. Instead, focus on why this particular study was needed to fill the gap you noticed and why that gap needed filling in the first place.

- Mainly, you want to remind us of how your research will increase our knowledge base and inspire others to conduct further research.

- Clearly tell us what that piece of missing knowledge was.

- Answer each of the questions you asked in your Introduction and explain how your results support those conclusions.

- Make sure to factor in all results relevant to the questions (even if those results were not statistically significant).

- Focus on the significance of the most noteworthy results.

- If conflicting inferences can be drawn from your results, evaluate the merits of all of them.

- Don’t rehash what you said earlier in the Results section. Rather, discuss your findings in the context of answering your hypothesis. Instead of making statements like “[The first result] was this…,” say, “[The first result] suggests [conclusion].”

- Do your conclusions line up with existing literature?

- Discuss whether your findings agree with current knowledge and expectations.

- Keep in mind good persuasive argument skills, such as explaining the strengths of your arguments and highlighting the weaknesses of contrary opinions.

- If you discovered something unexpected, offer reasons. If your conclusions aren’t aligned with current literature, explain.

- Address any limitations of your study and how relevant they are to interpreting your results and validating your findings.

- Make sure to acknowledge any weaknesses in your conclusions and suggest room for further research concerning that aspect of your analysis.

- Make sure your suggestions aren’t ones that should have been conducted during your research! Doing so might raise questions about your initial research design and protocols.

- Similarly, maintain a critical but unapologetic tone. You want to instill confidence in your readers that you have thoroughly examined your results and have objectively assessed them in a way that would benefit the scientific community’s desire to expand our knowledge base.

- Recommend next steps.

- Your suggestions should inspire other researchers to conduct follow-up studies to build upon the knowledge you have shared with them.

- Keep the list short (no more than two).

How to Write the Discussion Section

The above list of what to include in the Discussion section gives an overall idea of what you need to focus on throughout the section. Below are some tips and general suggestions about the technical aspects of writing and organization that you might find useful as you draft or revise the contents we’ve outlined above.

Technical writing elements

- Embrace active voice because it eliminates the awkward phrasing and wordiness that accompanies passive voice.

- Use the present tense, which should also be employed in the Introduction.

- Sprinkle with first person pronouns if needed, but generally, avoid it. We want to focus on your findings.

- Maintain an objective and analytical tone.

Discussion section organization

- Keep the same flow across the Results, Methods, and Discussion sections.

- We develop a rhythm as we read and parallel structures facilitate our comprehension. When you organize information the same way in each of these related parts of your journal manuscript, we can quickly see how a certain result was interpreted and quickly verify the particular methods used to produce that result.

- Notice how using parallel structure will eliminate extra narration in the Discussion part since we can anticipate the flow of your ideas based on what we read in the Results segment. Reducing wordiness is important when you only have a few paragraphs to devote to the Discussion section!

- Within each subpart of a Discussion, the information should flow as follows: (A) conclusion first, (B) relevant results and how they relate to that conclusion and (C) relevant literature.

- End with a concise summary explaining the big-picture impact of your study on our understanding of the subject matter. At the beginning of your Discussion section, you stated why this particular study was needed to fill the gap you noticed and why that gap needed filling in the first place. Now, it is time to end with “how your research filled that gap.”

Discussion Part 1: Summarizing Key Findings

Begin the Discussion section by restating your statement of the problem and briefly summarizing the major results. Do not simply repeat your findings. Rather, try to create a concise statement of the main results that directly answer the central research question that you stated in the Introduction section . This content should not be longer than one paragraph in length.

Many researchers struggle with understanding the precise differences between a Discussion section and a Results section . The most important thing to remember here is that your Discussion section should subjectively evaluate the findings presented in the Results section, and in relatively the same order. Keep these sections distinct by making sure that you do not repeat the findings without providing an interpretation.

Phrase examples: Summarizing the results

- The findings indicate that …

- These results suggest a correlation between A and B …

- The data present here suggest that …

- An interpretation of the findings reveals a connection between…

Discussion Part 2: Interpreting the Findings

What do the results mean? It may seem obvious to you, but simply looking at the figures in the Results section will not necessarily convey to readers the importance of the findings in answering your research questions.

The exact structure of interpretations depends on the type of research being conducted. Here are some common approaches to interpreting data:

- Identifying correlations and relationships in the findings

- Explaining whether the results confirm or undermine your research hypothesis

- Giving the findings context within the history of similar research studies

- Discussing unexpected results and analyzing their significance to your study or general research

- Offering alternative explanations and arguing for your position

Organize the Discussion section around key arguments, themes, hypotheses, or research questions or problems. Again, make sure to follow the same order as you did in the Results section.

Discussion Part 3: Discussing the Implications

In addition to providing your own interpretations, show how your results fit into the wider scholarly literature you surveyed in the literature review section. This section is called the implications of the study . Show where and how these results fit into existing knowledge, what additional insights they contribute, and any possible consequences that might arise from this knowledge, both in the specific research topic and in the wider scientific domain.

Questions to ask yourself when dealing with potential implications:

- Do your findings fall in line with existing theories, or do they challenge these theories or findings? What new information do they contribute to the literature, if any? How exactly do these findings impact or conflict with existing theories or models?

- What are the practical implications on actual subjects or demographics?

- What are the methodological implications for similar studies conducted either in the past or future?

Your purpose in giving the implications is to spell out exactly what your study has contributed and why researchers and other readers should be interested.

Phrase examples: Discussing the implications of the research

- These results confirm the existing evidence in X studies…

- The results are not in line with the foregoing theory that…

- This experiment provides new insights into the connection between…

- These findings present a more nuanced understanding of…

- While previous studies have focused on X, these results demonstrate that Y.

Step 4: Acknowledging the limitations

All research has study limitations of one sort or another. Acknowledging limitations in methodology or approach helps strengthen your credibility as a researcher. Study limitations are not simply a list of mistakes made in the study. Rather, limitations help provide a more detailed picture of what can or cannot be concluded from your findings. In essence, they help temper and qualify the study implications you listed previously.

Study limitations can relate to research design, specific methodological or material choices, or unexpected issues that emerged while you conducted the research. Mention only those limitations directly relate to your research questions, and explain what impact these limitations had on how your study was conducted and the validity of any interpretations.

Possible types of study limitations:

- Insufficient sample size for statistical measurements

- Lack of previous research studies on the topic

- Methods/instruments/techniques used to collect the data

- Limited access to data

- Time constraints in properly preparing and executing the study

After discussing the study limitations, you can also stress that your results are still valid. Give some specific reasons why the limitations do not necessarily handicap your study or narrow its scope.

Phrase examples: Limitations sentence beginners

- “There may be some possible limitations in this study.”

- “The findings of this study have to be seen in light of some limitations.”

- “The first limitation is the…The second limitation concerns the…”

- “The empirical results reported herein should be considered in the light of some limitations.”

- “This research, however, is subject to several limitations.”

- “The primary limitation to the generalization of these results is…”

- “Nonetheless, these results must be interpreted with caution and a number of limitations should be borne in mind.”

Discussion Part 5: Giving Recommendations for Further Research

Based on your interpretation and discussion of the findings, your recommendations can include practical changes to the study or specific further research to be conducted to clarify the research questions. Recommendations are often listed in a separate Conclusion section , but often this is just the final paragraph of the Discussion section.

Suggestions for further research often stem directly from the limitations outlined. Rather than simply stating that “further research should be conducted,” provide concrete specifics for how future can help answer questions that your research could not.

Phrase examples: Recommendation sentence beginners

- Further research is needed to establish …

- There is abundant space for further progress in analyzing…

- A further study with more focus on X should be done to investigate…

- Further studies of X that account for these variables must be undertaken.

Consider Receiving Professional Language Editing

As you edit or draft your research manuscript, we hope that you implement these guidelines to produce a more effective Discussion section. And after completing your draft, don’t forget to submit your work to a professional proofreading and English editing service like Wordvice, including our manuscript editing service for paper editing , cover letter editing , SOP editing , and personal statement proofreading services. Language editors not only proofread and correct errors in grammar, punctuation, mechanics, and formatting but also improve terms and revise phrases so they read more naturally. Wordvice is an industry leader in providing high-quality revision for all types of academic documents.

For additional information about how to write a strong research paper, make sure to check out our full research writing series !

Wordvice Writing Resources

- How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

- Which Verb Tenses to Use in a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Title

- Useful Phrases for Academic Writing

- Common Transition Terms in Academic Papers

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- 100+ Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- Tips for Paraphrasing in Research Papers

Additional Academic Resources

- Guide for Authors. (Elsevier)

- How to Write the Results Section of a Research Paper. (Bates College)

- Structure of a Research Paper. (University of Minnesota Biomedical Library)

- How to Choose a Target Journal (Springer)

- How to Write Figures and Tables (UNC Writing Center)

- Langson Library

- Science Library

- Grunigen Medical Library

- Law Library

- Connect From Off-Campus

- Accessibility

- Gateway Study Center

Email this link

Writing a scientific paper.

- Writing a lab report

- INTRODUCTION

Writing a "good" discussion section

"discussion and conclusions checklist" from: how to write a good scientific paper. chris a. mack. spie. 2018., peer review.

- LITERATURE CITED

- Bibliography of guides to scientific writing and presenting

- Presentations

- Lab Report Writing Guides on the Web

This is is usually the hardest section to write. You are trying to bring out the true meaning of your data without being too long. Do not use words to conceal your facts or reasoning. Also do not repeat your results, this is a discussion.

- Present principles, relationships and generalizations shown by the results

- Point out exceptions or lack of correlations. Define why you think this is so.

- Show how your results agree or disagree with previously published works

- Discuss the theoretical implications of your work as well as practical applications

- State your conclusions clearly. Summarize your evidence for each conclusion.

- Discuss the significance of the results

- Evidence does not explain itself; the results must be presented and then explained.

- Typical stages in the discussion: summarizing the results, discussing whether results are expected or unexpected, comparing these results to previous work, interpreting and explaining the results (often by comparison to a theory or model), and hypothesizing about their generality.

- Discuss any problems or shortcomings encountered during the course of the work.

- Discuss possible alternate explanations for the results.

- Avoid: presenting results that are never discussed; presenting discussion that does not relate to any of the results; presenting results and discussion in chronological order rather than logical order; ignoring results that do not support the conclusions; drawing conclusions from results without logical arguments to back them up.

CONCLUSIONS

- Provide a very brief summary of the Results and Discussion.

- Emphasize the implications of the findings, explaining how the work is significant and providing the key message(s) the author wishes to convey.

- Provide the most general claims that can be supported by the evidence.

- Provide a future perspective on the work.

- Avoid: repeating the abstract; repeating background information from the Introduction; introducing new evidence or new arguments not found in the Results and Discussion; repeating the arguments made in the Results and Discussion; failing to address all of the research questions set out in the Introduction.

WHAT HAPPENS AFTER I COMPLETE MY PAPER?

The peer review process is the quality control step in the publication of ideas. Papers that are submitted to a journal for publication are sent out to several scientists (peers) who look carefully at the paper to see if it is "good science". These reviewers then recommend to the editor of a journal whether or not a paper should be published. Most journals have publication guidelines. Ask for them and follow them exactly. Peer reviewers examine the soundness of the materials and methods section. Are the materials and methods used written clearly enough for another scientist to reproduce the experiment? Other areas they look at are: originality of research, significance of research question studied, soundness of the discussion and interpretation, correct spelling and use of technical terms, and length of the article.

- << Previous: RESULTS

- Next: LITERATURE CITED >>

- Last Updated: Aug 4, 2023 9:33 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uci.edu/scientificwriting

Off-campus? Please use the Software VPN and choose the group UCIFull to access licensed content. For more information, please Click here

Software VPN is not available for guests, so they may not have access to some content when connecting from off-campus.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

General Research Paper Guidelines: Discussion

Discussion section.

The overall purpose of a research paper’s discussion section is to evaluate and interpret results, while explaining both the implications and limitations of your findings. Per APA (2020) guidelines, this section requires you to “examine, interpret, and qualify the results and draw inferences and conclusions from them” (p. 89). Discussion sections also require you to detail any new insights, think through areas for future research, highlight the work that still needs to be done to further your topic, and provide a clear conclusion to your research paper. In a good discussion section, you should do the following:

- Clearly connect the discussion of your results to your introduction, including your central argument, thesis, or problem statement.

- Provide readers with a critical thinking through of your results, answering the “so what?” question about each of your findings. In other words, why is this finding important?

- Detail how your research findings might address critical gaps or problems in your field

- Compare your results to similar studies’ findings

- Provide the possibility of alternative interpretations, as your goal as a researcher is to “discover” and “examine” and not to “prove” or “disprove.” Instead of trying to fit your results into your hypothesis, critically engage with alternative interpretations to your results.

For more specific details on your Discussion section, be sure to review Sections 3.8 (pp. 89-90) and 3.16 (pp. 103-104) of your 7 th edition APA manual

*Box content adapted from:

University of Southern California (n.d.). Organizing your social sciences research paper: 8 the discussion . https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/discussion

Limitations

Limitations of generalizability or utility of findings, often over which the researcher has no control, should be detailed in your Discussion section. Including limitations for your reader allows you to demonstrate you have thought critically about your given topic, understood relevant literature addressing your topic, and chosen the methodology most appropriate for your research. It also allows you an opportunity to suggest avenues for future research on your topic. An effective limitations section will include the following:

- Detail (a) sources of potential bias, (b) possible imprecision of measures, (c) other limitations or weaknesses of the study, including any methodological or researcher limitations.

- Sample size: In quantitative research, if a sample size is too small, it is more difficult to generalize results.

- Lack of available/reliable data : In some cases, data might not be available or reliable, which will ultimately affect the overall scope of your research. Use this as an opportunity to explain areas for future study.

- Lack of prior research on your study topic: In some cases, you might find that there is very little or no similar research on your study topic, which hinders the credibility and scope of your own research. If this is the case, use this limitation as an opportunity to call for future research. However, make sure you have done a thorough search of the available literature before making this claim.

- Flaws in measurement of data: Hindsight is 20/20, and you might realize after you have completed your research that the data tool you used actually limited the scope or results of your study in some way. Again, acknowledge the weakness and use it as an opportunity to highlight areas for future study.

- Limits of self-reported data: In your research, you are assuming that any participants will be honest and forthcoming with responses or information they provide to you. Simply acknowledging this assumption as a possible limitation is important in your research.

- Access: Most research requires that you have access to people, documents, organizations, etc.. However, for various reasons, access is sometimes limited or denied altogether. If this is the case, you will want to acknowledge access as a limitation to your research.

- Time: Choosing a research focus that is narrow enough in scope to finish in a given time period is important. If such limitations of time prevent you from certain forms of research, access, or study designs, acknowledging this time restraint is important. Acknowledging such limitations is important, as they can point other researchers to areas that require future study.

- Potential Bias: All researchers have some biases, so when reading and revising your draft, pay special attention to the possibilities for bias in your own work. Such bias could be in the form you organized people, places, participants, or events. They might also exist in the method you selected or the interpretation of your results. Acknowledging such bias is an important part of the research process.

- Language Fluency: On occasion, researchers or research participants might have language fluency issues, which could potentially hinder results or how effectively you interpret results. If this is an issue in your research, make sure to acknowledge it in your limitations section.

University of Southern California (n.d.). Organizing your social sciences research paper: Limitations of the study . https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/limitations

In many research papers, the conclusion, like the limitations section, is folded into the larger discussion section. If you are unsure whether to include the conclusion as part of your discussion or as a separate section, be sure to defer to the assignment instructions or ask your instructor.

The conclusion is important, as it is specifically designed to highlight your research’s larger importance outside of the specific results of your study. Your conclusion section allows you to reiterate the main findings of your study, highlight their importance, and point out areas for future research. Based on the scope of your paper, your conclusion could be anywhere from one to three paragraphs long. An effective conclusion section should include the following:

- Describe the possibilities for continued research on your topic, including what might be improved, adapted, or added to ensure useful and informed future research.

- Provide a detailed account of the importance of your findings

- Reiterate why your problem is important, detail how your interpretation of results impacts the subfield of study, and what larger issues both within and outside of your field might be affected from such results

University of Southern California (n.d.). Organizing your social sciences research paper: 9. the conclusion . https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/conclusion

- Previous Page: Results

- Next Page: References

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

How To Write The Discussion Chapter

A Simple Explainer With Examples + Free Template

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2021

If you’re reading this, chances are you’ve reached the discussion chapter of your thesis or dissertation and are looking for a bit of guidance. Well, you’ve come to the right place ! In this post, we’ll unpack and demystify the typical discussion chapter in straightforward, easy to understand language, with loads of examples .

Overview: The Discussion Chapter

- What the discussion chapter is

- What to include in your discussion

- How to write up your discussion

- A few tips and tricks to help you along the way

- Free discussion template

What (exactly) is the discussion chapter?

The discussion chapter is where you interpret and explain your results within your thesis or dissertation. This contrasts with the results chapter, where you merely present and describe the analysis findings (whether qualitative or quantitative ). In the discussion chapter, you elaborate on and evaluate your research findings, and discuss the significance and implications of your results .

In this chapter, you’ll situate your research findings in terms of your research questions or hypotheses and tie them back to previous studies and literature (which you would have covered in your literature review chapter). You’ll also have a look at how relevant and/or significant your findings are to your field of research, and you’ll argue for the conclusions that you draw from your analysis. Simply put, the discussion chapter is there for you to interact with and explain your research findings in a thorough and coherent manner.

What should I include in the discussion chapter?

First things first: in some studies, the results and discussion chapter are combined into one chapter . This depends on the type of study you conducted (i.e., the nature of the study and methodology adopted), as well as the standards set by the university. So, check in with your university regarding their norms and expectations before getting started. In this post, we’ll treat the two chapters as separate, as this is most common.

Basically, your discussion chapter should analyse , explore the meaning and identify the importance of the data you presented in your results chapter. In the discussion chapter, you’ll give your results some form of meaning by evaluating and interpreting them. This will help answer your research questions, achieve your research aims and support your overall conclusion (s). Therefore, you discussion chapter should focus on findings that are directly connected to your research aims and questions. Don’t waste precious time and word count on findings that are not central to the purpose of your research project.

As this chapter is a reflection of your results chapter, it’s vital that you don’t report any new findings . In other words, you can’t present claims here if you didn’t present the relevant data in the results chapter first. So, make sure that for every discussion point you raise in this chapter, you’ve covered the respective data analysis in the results chapter. If you haven’t, you’ll need to go back and adjust your results chapter accordingly.

If you’re struggling to get started, try writing down a bullet point list everything you found in your results chapter. From this, you can make a list of everything you need to cover in your discussion chapter. Also, make sure you revisit your research questions or hypotheses and incorporate the relevant discussion to address these. This will also help you to see how you can structure your chapter logically.

Need a helping hand?

How to write the discussion chapter

Now that you’ve got a clear idea of what the discussion chapter is and what it needs to include, let’s look at how you can go about structuring this critically important chapter. Broadly speaking, there are six core components that need to be included, and these can be treated as steps in the chapter writing process.

Step 1: Restate your research problem and research questions

The first step in writing up your discussion chapter is to remind your reader of your research problem , as well as your research aim(s) and research questions . If you have hypotheses, you can also briefly mention these. This “reminder” is very important because, after reading dozens of pages, the reader may have forgotten the original point of your research or been swayed in another direction. It’s also likely that some readers skip straight to your discussion chapter from the introduction chapter , so make sure that your research aims and research questions are clear.

Step 2: Summarise your key findings

Next, you’ll want to summarise your key findings from your results chapter. This may look different for qualitative and quantitative research , where qualitative research may report on themes and relationships, whereas quantitative research may touch on correlations and causal relationships. Regardless of the methodology, in this section you need to highlight the overall key findings in relation to your research questions.

Typically, this section only requires one or two paragraphs , depending on how many research questions you have. Aim to be concise here, as you will unpack these findings in more detail later in the chapter. For now, a few lines that directly address your research questions are all that you need.

Some examples of the kind of language you’d use here include:

- The data suggest that…

- The data support/oppose the theory that…

- The analysis identifies…

These are purely examples. What you present here will be completely dependent on your original research questions, so make sure that you are led by them .

Step 3: Interpret your results

Once you’ve restated your research problem and research question(s) and briefly presented your key findings, you can unpack your findings by interpreting your results. Remember: only include what you reported in your results section – don’t introduce new information.

From a structural perspective, it can be a wise approach to follow a similar structure in this chapter as you did in your results chapter. This would help improve readability and make it easier for your reader to follow your arguments. For example, if you structured you results discussion by qualitative themes, it may make sense to do the same here.

Alternatively, you may structure this chapter by research questions, or based on an overarching theoretical framework that your study revolved around. Every study is different, so you’ll need to assess what structure works best for you.