Uncovering a Mystery: Making a Hypothesis

Students will imagine what it might be like to be an art historian or art collector by hypothesizing possible uses of a discovered wooden leg in a descriptive journal entry.

Students will be able to:

- describe activities and challenges of being an art historian or art collector;

- hypothesize possible original use(s) of the wooden Leg ; and

- create a written or illustrated journal entry from an art collector’s perspective that includes realistic, descriptive details.

- Warm-up: Give each student three copies of the handout that shows the shape of a leg. Have students design a background scene for the leg. Encourage them to be creative—they might want to draw the rest of a human being, turn the leg into a lamp, or create something new! Give them 2–3 minutes for each handout.

- Display the Polynesian Leg and ask students to look at it closely. Start by having them describe what they see.

- Have them brainstorm as a class what the Leg might have been used for. No idea is stupid! When they think they have exhausted the possibilities, encourage them to come up with three more ideas.

- Explain to students that archaeologists and art historians often have a general idea about what particular art objects were used for, but many times they do not know for certain. Even the Denver Art Museum isn’t sure why each piece of art was created!

- Have students pretend that they are art collectors who discover this wooden Leg in the Marquesas Islands. For older students, have them write a journal entry about the day they discover the Leg . Their entries should provide realistic, descriptive details that address “who, what, when, where, why, and how” questions. The students should also include some possible ideas about what the wooden Leg was originally used for and their reasons for thinking this way. Which possible use for the wooden Leg is the most likely given the relevant evidence?

- For younger students (and if time allows for older students), have them draw pictures in their journals of the Leg , illustrating different ways it might have been used.

- Encourage students to share their final writing pieces or show their drawings in small groups. Have students share one positive comment and one recommendation for improvement for each piece. You may want to make this a special occasion by bringing in snacks and hosting a writer’s breakfast or tea.

- Lined paper and pen/pencil for each student

- Handout with drawing of Leg , three copies for each student

- About the Art section on the Polynesian Leg

- One color copy of the Leg for every four students, or the ability to project the image onto a wall or screen

- Observe and Learn to Comprehend

- Relate and Connect to Transfer

- Oral Expression and Listening

- Research and Reasoning

- Writing and Composition

- Reading for All Purposes

- Collaboration

- Critical Thinking & Reasoning

- Information Literacy

- Self-Direction

Height: 22.625 in; Width: 5.38 in; Length of Foot: 7.75 in.

Native arts acquisition funds, 1948.795

Photograph © Denver Art Museum 2009. All Rights Reserved.

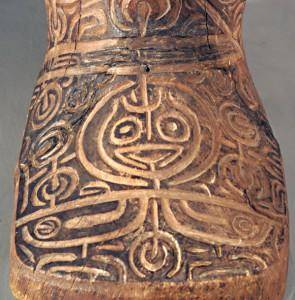

This wooden leg was carved by an artist from the Marquesas [mar-KAY-zas] Islands, a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, located in the Pacific Ocean. The Marquesas are the farthest group of islands from any continent. In terms of the arts, they are well-known for their tattoo art, as well as for their carvings in wood, bone, and shell. The process of tattooing in the Marquesas was treated as a ritual and the tattoo artist was a highly skilled artisan. Even today, many Marquesans beautify their bodies, proclaim their identities, and preserve their memories and experiences with tattoos.

We’re not sure why this particular object was created. It’s possible that it served as the leg for a specially constructed raised bed, made only for certain priests to lie on following the performance of important sacrifices. Tattoos were believed to protect a person’s body from harm and this belief applied to objects as well. Tattooing the bed’s leg may have served to protect these priests’ tapu , or sacred, state by preventing contact with the earth. This leg may also have been a model placed outside of a tattoo shop, advertising the services of the artist inside.

In the past, tattooing was a major art form in the Marquesas Islands and it inevitably influenced other art forms. The tattooing style of the Marquesas was the most elaborate in all of Polynesia. Tattoo images were marks of beauty as well as a reflection of knowledge and cultural beliefs. They also signaled a person’s social status—a higher ranking individual would have more tattoos than an individual of a lesser rank. All-over tattooing was a development unique to this area. Both males and females were tattooed, although only men covered their bodies from head to toe. Designs were also different for women and men.

Tattoo Imagery

Tattoo images have been carved all around the circumference of the wooden leg. The carving is particularly detailed on the foot.

The large crack down the front of the leg happened before the leg came into the Denver Art Museum’s possession. It is evidence of curing of the wood as it aged.

The peg, or wooden block at the top of the leg tells us that it may have been attached to something else.

Related Creativity Resources

Communication Through Clothing

In this lesson, students will explore the symbols, patterns, and colors that are important to the Osage people. Students will create a t-shirt design that expresses information about their own culture and personality, and reflect upon messages communicated by their clothing design.

Say It with Flowers

Students will examine the artistic characteristics of Three Young Girls ; explain the meaning and significance of the flowers in the painting and other well-known flowers.

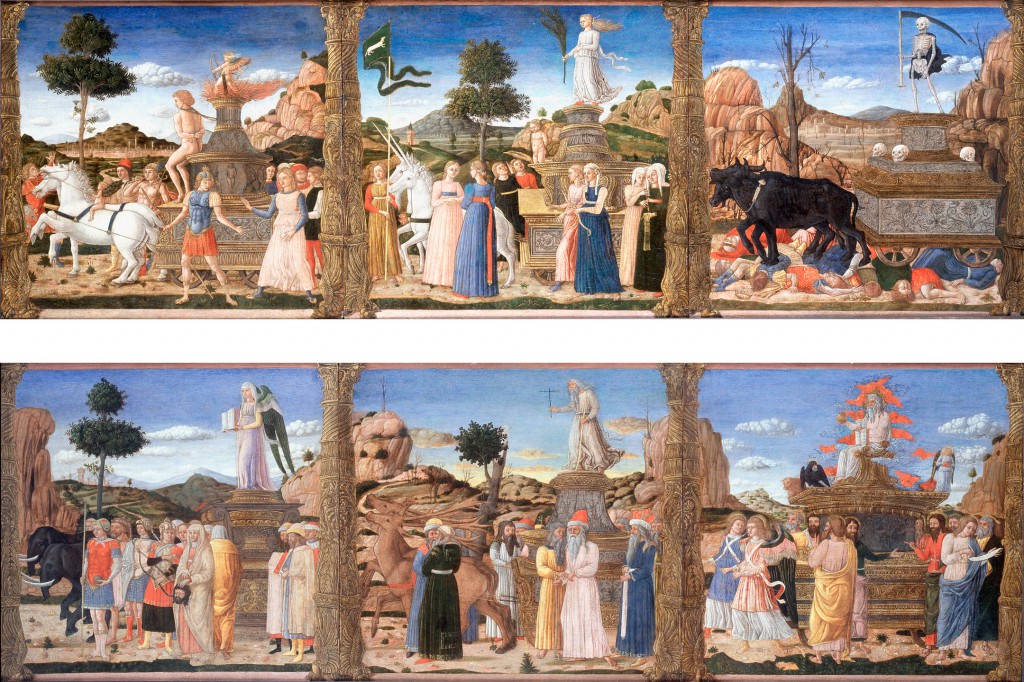

A Triumphant Message

Students will examine the sequencing of events in the paintings and create a six-part story of sequential “triumphs” that ends with an important message.

Poetry with Natural Similes and Metaphors

Students will examine the artistic characteristics of Summer ; make comparisons between physical features of the figure portrayed in Summer with items from the natural world; and create poems using similes and metaphors comparing a person’s physical appearance with items from the natural world.

Making the Commonplace Distinguished and Beautiful

Students will learn how William Merritt Chase aimed to portray commonplace objects in ways that made them appear distinguished and beautiful. They will then create a written description of a commonplace object that makes it appear distinguished and beautiful.

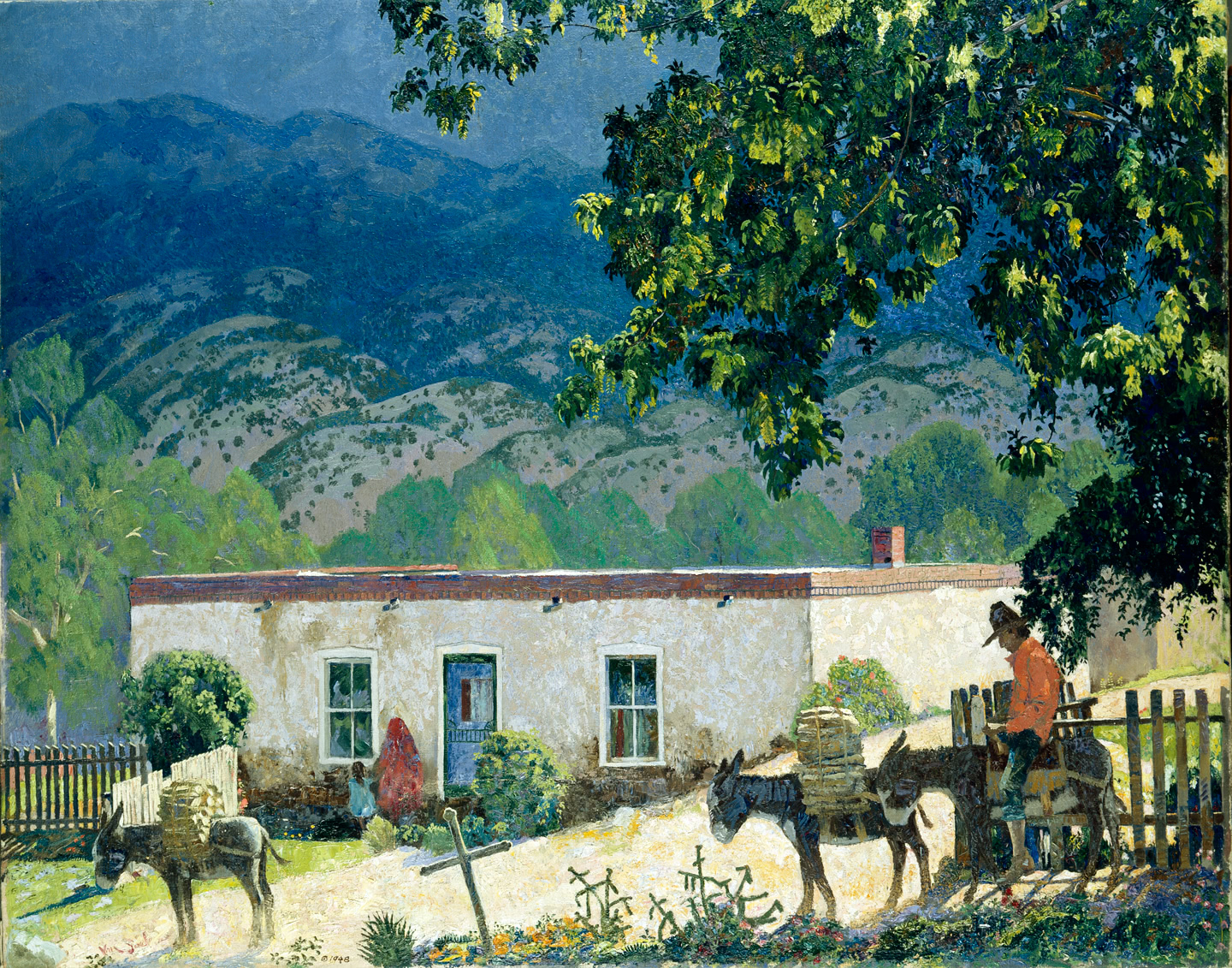

Beyond First Impressions

Students will examine the visual tools used in the painting Road to Santa Fe and how those tools help the painter tell a particular story. They will then use the painting to explore storytelling and use brainstorming strategies to enrich the content and voice of stories they will write. Multiple drafts and peer-editing will help teach students how working and reworking a piece, much like painters do when planning a painting, will strengthen their finished product.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

Published on May 6, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection .

Example: Hypothesis

Daily apple consumption leads to fewer doctor’s visits.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more types of variables .

- An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls.

- A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

If there are any control variables , extraneous variables , or confounding variables , be sure to jot those down as you go to minimize the chances that research bias will affect your results.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Step 1. Ask a question

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2. Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to ensure that you’re embarking on a relevant topic . This can also help you identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalize more complex constructs.

Step 3. Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

4. Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

5. Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if…then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis . The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

- H 0 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has no effect on their final exam scores.

- H 1 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has a positive effect on their final exam scores.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A hypothesis is not just a guess — it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Null and alternative hypotheses are used in statistical hypothesis testing . The null hypothesis of a test always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 17, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/hypothesis/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, operationalization | a guide with examples, pros & cons, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Why Did Prehistoric People Draw in the Caves?

Rock art remains one of the last mysteries of humanity, grotte chauvet - unesco world heritage site.

The secret of natural history Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

How were prehistoric humans represented in the 19th century?

We have known about prehistoric humans for a long time and the Cro-Magnon Man was identified as early as 1868 by Louis Lartet in Dordogne. The first discovery of Neanderthals was even earlier in 1829 in Belgium. In 1856, bones were found in a small cave in the Neander Valley in Germany. All these fossils have since been known as "wild men."

Replica of Chabot Cave (2018/2018) by Thierry Allard Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

The discovery of Paleolithic rock art

Paleolithic rock art was identified shortly after these first paleoanthropological discoveries in 1875 in Altamira, Spain and in 1879 in the Chabot Cave in the Ardèche Valley. Since then, several hypotheses explaining the motivations of our ancestors have been discovered.

Return of a bear hunt - Age of polished stone (1884/1884) by F. Cormon Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

Art for art's sake

This hypothesis suggests that prehistoric humans painted, drew, engraved, or carved for strictly aesthetic reasons in order to represent beauty. However, all the parietal figures, during the 30,000 years that this practice lasted in Europe, do not have the same aesthetic quality.

Megaceros Gallery (Chauvet Cave) by J. Clottes Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

On the other hand, most of the parietal representations found are located in caves (those that may have existed outside may have been destroyed). And so why represent beauty if it is not shared and is hidden in the darkness of deep caves?

Rousseau (1755), "Discourse on Inequality" and the invention of the idea of the noble savage (1755/1755) by J.-J. rousseau (1712-1778) Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

This assumption of art for art's sake was inspired by the myth of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's "noble savage." It was also used to convey anticlerical ideas.

Totems, Original 'Namgis Burial Grounds by R. Parker Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

This hypothesis suggests that each clan or human group is represented by a symbolic animal, its totem, a being possibly worshiped for the protection it brings and the ancestral heritage it embodies.

Red steppe bison in the Altamira cave (Spain) (2003/2003) by J. Clottes Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

If this hypothesis were universally applicable, we would see disparities in Europe. However, European Paleolithic parietal art exhibits a certain symbolic homogeneity with persistence of the same animal species represented. In fact, there are few animal species that were shared and reproduced for thousands of years in very diverse geographical areas. Reindeer, bison, and horses were animals that were very often depicted.

Steppe bison in the Cave of Niaux (France) (1990/1990) by Jean Clottes Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

Finally, animals are represented pierced with arrows, a symbol that cannot be reconciled with the 'worship' that was to be given to them if these effigies were well and truly adored by our ancestors.

Abbé Breuil in front of Lascaux's entrance Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

The magic hunt

Abbé Breuil (1877-1961) and Henri Begouën (1863-1956) repeated the hypothesis of "prescience magic," suggesting that prehistoric humans attempted to influence the result of their hunt by drawing it in caves.

Abbot Breuil in the cave of Lascaux faces the panel of the Unicorn. (1940/1940) Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

For Abbé Breuil it was more acceptable to allude to magical practice rather than spirituality, which could have steered the discussion towards religious issues.

A piece from the panel of the so-called "Chinese horses" (Lascaux) (1990/1990) by Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

However, the correlation between animal species pierced by arrows and archeological excavations is tenuous. The representations of these animals symbolized with arrows piercing them, besides being few in number in all of European parietal art, has little correspondence to the archeological remains found. The hypothesis of sympathetic magic has been abandoned.

André Leroi-Gourhan (1911-1986) in the Rouffignac cave (Dordogne) by unknown Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

Structuralism

André Leroi-Gourhan (1911-1896) proposed a statistical approach to parietal art. He was hoping to identify a structure within a painting cave. He proposed a spatial approach to adorned caves involving central and marginal symbolic figures. According to Leroi-Gourhan, the most important would be the male/female duality, especially embodied by the auroch-bison association on the one hand, and horses on the other.

Ideal layout of a paleolithic sanctuary after André Leroi-Gourhan. (1965/1965) by A. Leroi-Gourhan Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

This statistical approach has never been scientifically demonstrated despite the influence it had on university education.

Jean Clottes (2015/2015) by Roland KADRINI Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

According to Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams, who decided to re-introduce the shamanic hypothesis advanced by the Romanian historian Mircea Eliade (1907-1986), the figures drawn in the caves would be some representations of visions acquired during a trance-like or near-trance state.

Yakout shaman (1983/1983) Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

In particular, this hypothesis is based on ethnological observations made with groups of modern-day hunter-gatherers. It is also based on the perception of entoptic signs (points, lines, grids, etc.) whose source is the eye itself. These optical phenomena can be caused by the inhalation of products or substances contained in the materials used to make parietal figures (charcoal, ocher). These spontaneous entoptic signs can also be the symptoms of migraines (flashing lights and zig-zag patterns, for example).

Diversity of tectiform signs (2013/2013) by Alain Roussot Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

Although not well received, this hypothesis is not intended to be a global and exclusive explanation but proposes an explanatory framework. Numerous testimonies by speleologists attest to the hallucinogenic character of the caves, where cold, humidity, darkness, and the absence of sensory cues facilitate optical and auditory hallucinations. Thus the caves could have a dual role with fundamentally related aspects: facilitating hallucinatory visions and coming into contact with spirits through the wall.

Chuka dance in the tent of a chef (1868/1868) by Lanoye, F. de (Ferdinand), 1810-1870 Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

Jean Clottes clarifies his hypothesis (2004): "Paintings made in the middle of a large chamber will probably have a meaning quite different from those found in the depths of a narrow diverticulum where only one person could slip through. The latter can be related […] to either the search for visions or the desire to go as far as possible to the bottom of the earth. Spectacular paintings in large spaces could, however, have a didactic and educational role, and serve as the foundation of ceremonies and rituals."

Philippe Descola, anthropologist (Collège de France) (2014/2014) by Cl. Truong-Ngoc Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

The absence of words

According to the anthropologist Philippe Descola (Collège de France), the people of the Chauvet Cave would have been more comfortable using images instead of words to express complex thoughts. In advancing this idea, we can indeed imagine that these people were incapable of naming objects they would have drawn. Perhaps we can also imagine the existence of taboos whereby it was essential to depict things in the drawing without naming them.

Prehistoric Art (2013/2013) by SMERGC / MQB Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

This videos explores the discovery of prehistoric art at the beginning of the 20th century, where several theories have emerged to explain why our ancestors painted in caves. Totemism (where each drawing represented the animal protecting the tribe) was favored but archeological findings and the science of ethnology paved the way for the "sympathical magic" theory of Abbé Breuil. According to him, drawing animals is a way to kill them symbolically before the hunt. Starting from the 1950s, structuralism gained traction, which associates drawings with symbols. In 1994, the discovery of Chauvet was a shock, as no prehistorian thought humans 36, 000 years ago could create such art.

Chauvet Cave Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

The testimony of the Chauvet Cave

The rock art of the Chauvet Cave has the same typology of signs as those observed in other adorned European caves: animal, geometric, and anthropomorphic representations (handprints, the lower body, and the female body), with the latter being the fewest in number.

Central Piece of the Feline Fresco (Chauvet Cave, Ardèche) (2018-08-02/2018-08-02) by L. Guichard/Perazio/Smergc Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

The bestiary of the Chauvet Cave is distinguished by the abundance of animals at the top of the food chain: big cats (the most numerous), mammoths, and woolly rhinos, animals not hunted or infrequently hunted by men, except opportunistically.

Cave bear skull on a rock (Chauvet cave) (2006/2006) by L. Guichard Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

For Jean Clottes, the Chauvet Cave is a space that fosters contact between the real world and spirit world. He even suggested that the cave bear played the role of the mediator. Indeed, the Chauvet Cave is a subterranean space heavily frequented by this animal. However, many recesses around the Chauvet Cave are equally large and accessible, and none of them was chosen by the Palaeolithic people. Only the Chauvet Cave, frequently visited by cave bears, was occupied and adorned by people.

Horses panel (Chauvet cave) (2006/2006) by L. Guichard Grotte Chauvet - UNESCO World Heritage Site

In conclusion, there is still no way of translating rock art. Cave art is a symbolic representation of codes produced by Palaeolithic human thinking. Although this cannot be a definitive conclusion, we can say that parietal art symbolizes the fusion of the Palaeolithic human and animal worlds, whereas today we perceive these two entities as dissociated from each other. In parietal art, man is symbolically represented and present in animal representations.

The Syndicat mixte de l'Espace de restitution de la grotte Chauvet (Public Union to manage the Chauvet Cave/SMERGC) thanks the Ministry of Culture and Communication. This exhibition was created as part of an agreement linking these two partners to promote the Chauvet Cave and its geographical and historical context. SMERGC is the designer, developer and owner of the La Grotte Chauvet 2 site (formerly known as Caverne du Pont d'Arc). It prepared and defended the application package of the Chauvet Cave for inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage List. http://lacavernedupontdarc.org/ https://www.facebook.com/lagrottechauvet2/ SMERGC also thanks Google Arts & Culture.

The Bear Hollow Chamber

The skull chamber and the lattices gallery, the end chamber, the candle chamber, chauvet cave: the first known masterpiece of humanity, the brunel room, the hillaire chamber, the red panels gallery, the megaloceros gallery, meet the people of the chauvet cave.

The Art of Realism

What’s real? See for yourself how five artists represent the reality of their – or other – worlds.

Idea One: The Delight of Deception

Has a painting ever played tricks on your eyes?

When art looks really real, it is called _trompe l’oeil_, a French term meaning “fool the eye.” This Christian painting of Mary and baby Jesus contains a great example of _trompe l’oeil_: check out the fly near the foot of Mary’s throne. It looks so real, it’s tempting to brush it off the canvas!

How do you think the artist created this effect using paint?

Nicola di Maestro Antonio carefully selected his colors to create texture. He used perspective, a method of combining lines to create the illusion of depth, and also carefully painted shadows to give the figures a 3-D effect. Artists like di Antonio enjoyed painting beautiful pictures that viewers could experience both visually and emotionally. They believed people could feel more connected to paintings that looked realistic.

Di Antonio painted during the early Renaissance, a period of cultural rebirth in Europe. European artists began to use ancient Greek and Roman art as inspiration for their own artwork. They liked how ancient artists portrayed natural-looking people and objects. Even though figures were often idealized, they were dramatic, emotional, and humanlike.

The still life at the bottom of this painting may look realistic, but it also contains hidden meanings. Renaissance artists often put symbols, or iconography, into their art. The fly stands for evil, while the gourds stand for its antidote. The coral necklace around baby Jesus’s neck was a charm against evil.

This painting is an allegory, containing symbols that have deeper meanings. The pots and pans represent the four elements: fire, water, earth, and air.

This etching was inspired by Magritte’s earlier painting, La Trahison des images, which featured a realistic-looking pipe and a caption that read “This is not a pipe.” Magritte reminds the viewer that, no matter how realistic an image looks, it’s not actually real.

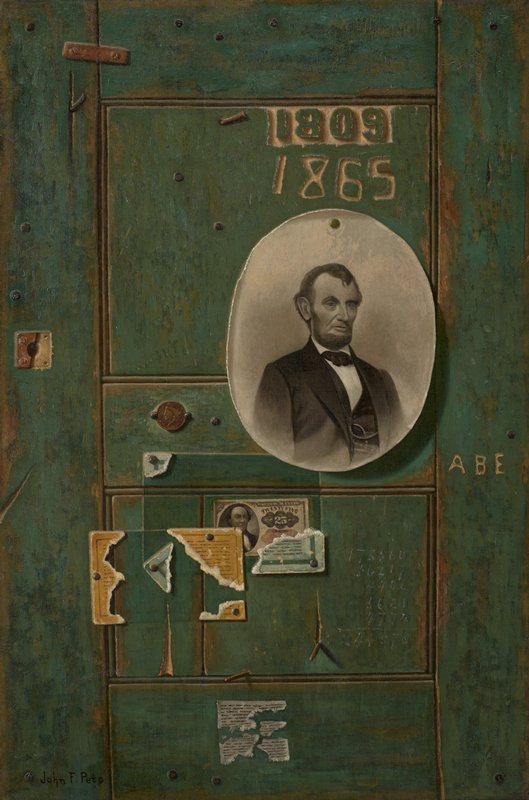

John Frederick Peto was skilled at painting _trompe l’oeil_ illusions. It’s hard to believe this is a painting—not a carved door.

Idea Two: How Real?

Gustave Courbet painted this scene of the French countryside during a period in which people in France expected art to depict a perfect world, much prettier than the one they lived in. But Courbet believed that art should be truthful and depict the actual world, dirt and all. Courbet called himself a “painter of the real,” vowing only to paint what he could see. He believed that art had the power to teach people lessons, or even criticize society.

This painting is of Ornans, the town where Courbet grew up. On the surface the scene is serene. But it also has a revolutionary hidden meaning. The houses on the hill sit atop the ruins of an old castle destroyed by the French government in the 1600s to prevent the provinces from organizing together to take power away from the monarchy. The village built on the ruins represents how the peasants of Courbet’s time were able to thrive over past oppression. Courbet celebrated the everyday lives of the working class in his art; he shows a woman doing laundry in the foreground of this picture.

Courbet’s painting not only depicts the real world, but it also actually includes it. Look closely at the painting. How would you describe the texture?

If it looks gritty and bumpy, it’s because Courbet actually mixed his paint with dirt from the valley. By mixing in dirt, he made the painting that much more real. In fact, his painting style offended the art critics because it was so unrefined. The ruggedness of the painted surface reflects the tough lives of the peasants. The dirt also reminds us of nature’s power in connecting our past, present, and future.

Winslow Homer was an American painter who depicted the world as he saw it. While Realism was a controversial movement in France, it was a traditional style for American artists. Paintings like this one allowed Americans to see worlds about which they may never have known.

The Ife (ee-fay) culture of Nigeria had a rich tradition of realist sculpture dating back to 1050 CE. Portrait heads like this one show careful attention to the details of facial features, including the pattern of scarification.

This closeup shows just how gritty the texture of this painting really is.

Gustave Courbet, French, 1819–77. _Chateau d’Ornans_ (detail), 1855. Oil on canvas. The John R. Van Derlip Fund and the William Hood Dunwoody Fund.

Idea Three: Artistic Role Playing

What seems to be going on in this picture?

This Japanese woodblock print is called a mitate. Mitate are visual puns or similes. They depict scenes from famous stories, plays, or parables, but with a twist: the artist often placed famous people, iconic settings, or beautiful women into the scene, creating a fantasy print that still contained elements of reality. Because mitate often referenced theater, literature, or religious stories, they were a sort of intellectual game. Viewers enjoyed identifying the people and stories in the prints.

One of the most popular types of mitate depicted beautiful women playing the roles of men from famous plays or stories. This image, created by Suzuki Harunobu, an artist who specialized in mitate, shows a scene from a well-known play from the no theatre called Hachi-no-ki (Potted Tree). The play is about an impoverished samurai who offered to burn his last three bonsai trees to keep a traveling monk warm on a cold winter night. The monk, who was really a government official in disguise, was so pleased with the samurai’s sacrifice that he rewarded the samurai with three tracts of land. Each piece of land was named for the sacrificed trees: pine, plum, and cherry. In this print, Harunobu replaces the poor samurai with a well-dressed, charming woman. She is about to daintily chop into the first tree.

Even though this print is a fantasy, Harunobu made it look believable. Describe the visual elements and details he included to make the scene look so real to his audience. For example, think about the props, sense of space, and the setting.

This is a photographic reenactment of Spanish painter Francisco de Goya’s etching, _The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters_. Yinka Shonibare substituted a real person wearing colorful Dutch wax cotton for Goya’s original figure. Yinka Shonibare, English, born 1962. _The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Australia)_, 2008. Chromogenic print mounted on aluminum. The C. Curtis Dunnavan Fund for Contemporary Art. © Yinka Shonibare, courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York.

Yasumasa Morimura recreates famous portraits using his own face and body as the subject. Here, he stands in for the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo. He wears fabric designed by Louis Vuitton and a Japanese-style hair ornament.

Idea Four: Re-presenting Art: Copies and Reproductions

This portrait of George Washington is actually a copy of Gilbert Stuart’s iconic _Landsdowne Portrait_, originally completed in 1796. Stuart’s portrait of Washington proved so popular, many banks, civic buildings, and museums requested copies of the painting. With Stuart’s permission, Thomas Sully began painting replicas because Stuart could not fill the orders by himself.

Both Stuart’s and Sully’s portraits depict Washington as a hero. Washington, the nation’s first president, helped unify and lead the new country, even in the face of political disagreements and foreign threats. Both paintings show Washington’s strong nature through his physical stance, in addition to subtle icons; his sword, for instance, represents his military background, while his simple black suit shows him to be one of “the people,” instead of a privileged and out-of-touch monarch.

The two portraits are very similar, but not exact. While Stuart’s portrait shows Washington holding out his hand, Sully placed Washington’s hand on the Constitution, symbolizing his connection to this important document.

Compare Sully’s portrait to the original painting at the National Gallery to see what other differences you can find.

Do you think Sully’s copy of Stuart’s painting has its own artistic value? Why or why not?

Is this copy worthy of being in a museum? What makes you say that?

Do you think this painting is important because it re-presents an iconic painting, or does it have merit on its own as a well-produced artwork?

This is essentially a miniature museum of selected works by artist Marcel Duchamp. Beginning in 1936, Duchamp began making miniature reproductions of his own artwork. He made 350 of these miniature museums. Marcel Duchamp, American (born France), 1887–1968. _Boite-en-Valise_ (Box in a suitcase), conceived 1936–1941; assembled 1961. Linen-covered box containing mixed media assemblage/collage of miniature replicas, photographs, and color reproductions of works by Duchamp. The William Hood Dunwoody Fund, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Estate of Marcel Duchamp.

Idea Five: Realism out of this World

In China, during the Eastern Han dynasty (25 BCE–220 CE), it was customary for people to furnish the tombs of loved ones with ceramic figures, called ming-ch’i, that depicted everyday people, places, and things from the living world. The idea was to recreate the comfort and familiarity of this world in the afterlife. They believed that the contents of the tomb should reflect the deceased’s life so he or she could continue living comfortably in the afterlife.

Ming-ch’i grew even more popular during the T’ang dynasty (7th–8th century CE) when funerals became extravagant festivals. In 742 CE, the government issued an edict that established how many ming-ch’i people could place in tombs. The number and quality corresponded to a person’s social rank and wealth. While notable people were allowed up to 70 pieces, commoners were only allowed about 15.

The person who crafted this model included realistic details of an actual Chinese style pigsty, including piglets, feeding containers—even toilets (located under the roof)!

Look closely at the scene. Describe the everyday details that you see. What can you learn about ancient Chinese culture from this artistic interpretation? What kind of person do you think this set was created for? What makes you say that?

This boat was placed in an Egyptian noble’s tomb to help transport his or her soul to the next life. It is a miniature replica of the boats Egyptians used for fishing and transportation in their daily lives. Egypt, Model Boat and Figures, Middle Kingdom (22nd–18th century BCE). Polychromed wood. The William Hood Dunwoody Fund.

Ceramic figurines, called haniwa, accompanied deceased Japanese aristocrats in their tombs. They may have been thought to provide protection, comfort, and service in the afterlife. Notice the realistic details of her necklace, hairdo, and medicine bag. Japan (Kofun), Haniwa Figure, 6th century. Earthenware. The Christina N. and Swan J. Turnblad Memorial Fund.

Moche, Peru, Andean Region. Vessel, ceramic, pigment, 1st–2nd century. William Hood Dunwoody Fund.

An ancient Peruvian civilization called Moche created pottery that faithfully reflected everyday life, such as this prominent couple feasting on seafood. Vessels like this would have accompanied elite people to their tombs, carrying on their status and serving in the afterlife.

Related Activities

Hidden messages.

An allegory is a creative way of expressing a hidden meaning, like a code. Allegories are often communicated through realistic and familiar images. For instance, sometimes movies use rain to symbolize sadness. Create your own allegory. Be creative—you can write, draw, or even build an allegory out of found objects. Ask your friends and family if they can figure out the meaning of your allegory.

It’s your (casting) call

Who would you like to see playing a character from your favorite story, movie, or even artwork? Create a drawing, poster, or woodblock-style print in which you substitute a friend, family member, pet, or cartoon character for this character. Use your imagination! Sponge Bob could become Cinderella, or your best friend could become Spider Man!

Discussion: Grounding Fantasy in Reality

What is it that makes a fantasy more believable? Think about movies like _Harry Potter_ and _The Avengers_. What do movies need to include in order to be considered believable? Why do you think they need to include these elements? Do you think cartoons can be believable? Why or why not?

Tombs and Time Capsules

Ancient tombs are like time capsules; they preserve some of the most important objects—including artwork—from the past. Such objects teach us a lot about the everyday lives and beliefs of ancient people. Design your own time capsule by drawing or crafting your objects from clay. What objects would you include to represent the important things in your life? Why did you include these objects? What might they say to future people about who you are and how you lived?

Fact vs. fiction

Pretend you’re an archaeologist. Use the search function on Mia’s website or visit the museum in person to create a “collection” of 3-5 objects from the same culture. Try to learn as much as you can about the works, then write a history about them. Talk about who created them, who may have used them, how they were used, when they were made, and what they are. But here’s the twist: Invent fake stories for 1-2 of the objects. Then present to your class, and see if your classmates can tell fact from fiction. Discuss as a class: Can you always believe what you hear? How do you separate fact from fiction? Why is this an important skill to have?

Realism for sale!

Advertisers often use realistic-looking, yet idealized, images to convince people to buy their products. Pick three advertisements in different media (television, magazines, websites, billboards, etc.) that use realistic images. Write a description for each ad. Then write a response to the following statements: 1.This advertising image is realistic because. . . 2.This advertising image is unrealistic because . . . 3.Write whether you believe the ad will be successful at selling the product. Be sure to explain why or why not. Then discuss your essay with your classmates.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 15 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

- Exhibitions and fairs

- The Art Market

- Artworks under the lens

- Famous faces

- Movements and techniques

- Partnerships

- … Collectors

- Collections

- Buy art online

Singulart Magazine > Advice for... > ... Collectors > How to interpret art

How to interpret art

While there’s no right or wrong way to view art, particular pieces can draw up different feelings in us. But how do you go about interpreting a piece of art, knowing that it’s so subjective?

With art-related topics on the rise over the past 12 months 1 , we spoke to our Head Curator, Marion Sailhen , who shared her expert tips on how to interpret your favorite pieces.

When it comes to understanding the artist, you should delve into their background and other pieces of work they’ve created, by taking these four aspects into consideration:

Many schools are famous for specific movements. For example, Goldsmith is known for its alumni of young British artists and was the place of study for Damian Hirst; and the Royal Academy is often referred to as one of the elite schools, with very strong formal training.

By looking into which school the artist went to, you can learn a lot about the environment they practiced in, and their foundations.

Residencies

Once emerging artists have finished school, they often head off to a residency. Find out the name of the residency if you can, including which artists went there before them.

Exhibitions

More often than not, group exhibitions are centered around a specific topic or theme, which in turn can provide a hint to what movements the artist is interested in, associated with, or inspired by.

If an artist’s work is more established, they’re likely to have their work featured in a local – or even national – museum. Take a look at the exhibition their work was featured in, to understand where their practice is situated in the art historical context.

Without basic knowledge of art history, it can be hard to understand the context or meaning of a specific piece of art. The more you read into different themes or movements , the more you learn about it, and you’ll learn your own personal tastes too.

Once you’ve read into the different types of movements, you’ll be able to see what type a particular piece is from (although it’s important to remember that movements are becoming less important in contemporary art).

If the piece of art is conceptual, it might be harder to read, but you can still determine the movement it’s from – you just need to remove the objects depicted and see them as ideas instead.

Situate the artwork into a series and rework the idea and over and over to test the limits of what your idea can do.

When asking questions about the artwork, it’s easy to break it down section-by-section. As a guide, the first things you should be questioning are the medium and the method (e.g. by palette knife or airbrush). To find your answer, you’ll need to get as close to the piece of art as possible.

The second thing to consider and question is the size – sometimes it’s an intentional choice of the artists, but it may not be that considered if they’re more focused on the theme. The same goes for color: have they created a piece of artwork that’s as big as possible so it can be absorbed by the color?

The next thing to consider when interpreting art, is to think about what may have inspired the artist to create their masterpiece – particularly if there was a cultural movement occurring around the time of creation.

Not all artists respond to current or historic events, but the ones that do tend to be more well-known. Just three examples of movements that inspired pieces of art are:

- Futurism : This is an Italian art movement that responded to the spirit of revolution and the progression of tech.

- Pop Art : This was a response to consumerism, the production of work and the rise of capitalism in the mid-20 th century – Andy Warhol is particularly well-known in this movement.

- Black Lives Matter : More recently, the BLM movement saw a huge increase in artists of color; and the African art market is still continuing to grow, with more grants and investments on offer.

Art can be influential, so by taking the time to think about how looking at a particular piece makes you feel, it could help you to understand what it means.

Whether you love it, hate it, or find it disgusting, good art makes you feel something. By feeling these emotions, you’ll think more deeply into the piece of art, which will probably make you want to find out even more about it.

One of the most important things to remember, is that art is subjective, and there’s no right or wrong answer. However, you want to interpret it at a surface or deeper level, remember that all reasonings are relevant and valid.

When an artist releases a piece of art into the world, they are giving up control behind the understanding and interpretation of their work, as everyone can view it as they choose to.

By talking to different people about how they feel and view the piece of work, you can start to build up a bigger picture, and it may even change your feelings towards it. After all, art is available to everyone – anyone can go to a gallery and enjoy and appreciate it. So, when interpreting a piece of art, speak to others who have seen it, to get their views on it.

Whether you’re a seasoned art appreciator or are just beginning to experience a new-found love for it, don’t be afraid to dig a little deeper into that particular piece of work you love, to see how you – and others around you – interpret it.

For more inspiration – whether it’s for tips on how to start your own art collection , or how to look at artwork online – head on over to our magazine .

- Google Search Trends for the topic ‘art guide’ increased by +160% in America over the past 12 months. Data correct as of 15.07.21.

You May Also Like

Singulart’s Collectors – Ralph and Marita Anstoetz

How to Start your Art Collection

How to transport an artwork?

How Artists Throughout History Became Famous

Does an artist really have to die before their work gains fame?

Leonardo Da Vinci was famous in his lifetime—a rare feat achieved by few other artists. He was skilled not only in painting and drawing, but also as a scientist, mathematician and inventor. He had a good start on his path to fame when, at 14, he was apprenticed to one of the best painters of the time, Andrea del Verrocchio.

As a fully-fledged artist, Da Vinci was commissioned by nobility and clergymen to paint; his success is often attributed to this. The Last Supper (1498) and Virgin of the Rocks (1483) were both religious commissions. In 1482, he was also employed by Lorenzo di Medici, the ruler of Florence, to make a silver lyre for the Duke of Milan as a peace offering.

People celebrated his genius both during his life and after his death. He was one of the first to start dissecting human bodies. The Mona Lisa is undeniably one of the most famous paintings in the world today, and Dan Brown’s incredibly popular 2003 novel, The Da Vinci Code propelled the artist into popular culture.

Michaelangelo is another rare artist who gained fame during his lifetime. The same Lorenzo di Medici also played a part in helping Michelangelo gain fame.

His most famous work, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, took four years to complete. He became so popular during in his lifetime that he had two biographies written about him before he died.

Struggling artists

What about artists who weren’t as fortunate to gain fame before they died? Vincent Van Gogh is probably the most well known for being a struggling artist. Some will say that it’s his innovative command of colour and shape that makes him so well known today, others will say his mental illness overshadows that. Referred to as the ‘mad artist’, a lot of people know him for cutting off his own ear.

Van Gogh became famous very soon after his death with memorial exhibitions held in Brussels, Paris, The Hague and Antwerp. His work was brought to public attention by critic Albert Aurier who in 1890 published an article praising the intensity of Van Gogh’s artistic vision. His fame reached its peak in the early 20th century when his letters were published, leading the public to a curiosity surrounding the mystique of the troubled genius. Additionally, Irving Stone wrote a biographical novel about the artist that started Van Gogh’s fame in America. His work went on to inspire and influence many other artists.

Like Van Gogh, Monet was underappreciated in his lifetime. Many people didn’t understand or like his unique style, and many of his works were rejected for deviating from tradition.

Picasso is one of the biggest names in art, and his work has broken the record price for art sold at auction multiple times. He studied under his father, a fine art teacher, and slowly began to gain fame for his work over time. He became involved in the art community, but didn’t really start making a profit until 1905 when he caught the attention of collector Gertrude Stein. He continued to grow in fame because of his ever-changing artistic development, from realism to cubism to surrealism, and is now known as an artistic trailblazer.

What about famous artists who are still alive today? Perhaps the most interesting of them all is Banksy, an artist who managed to gain fame and sell for millions without even revealing his identity.

Banksy has been working since the 1990s using graffiti to illustrate anti-establishment and anti-capitalist messages. Due to the very public setting of the work, Banksy’s pieces gain attention very quickly. This, combined with the elusivity of the artist, makes each one quickly gain worth. A number of celebrities have bought Banksy’s work, and there have been many disputes about who owns a piece of artwork when it shows up on their property.

How do artists become famous?

It’s safe to say that the most famous artists are the great innovators. Their ideas may be appreciated in their time or they may not; their rise to fame may be slow or explosive. There’s no definitive way to find fame as an artist—though it seems to be a combination of skill, imagination, cultural readiness and a little bit of luck.

Audrey Hepburn: Behind the Hollywood Legend

A river runs through it: an exhibition.

Related Posts

Maria Kreyn Presents Chronos in Venice

Tokyo Gendai Returns in July

Photographer Till Brönner in Budapest

Slider Status

By submitting this request for more information, you are giving your express written consent for Lindenwood University and its partners to contact you regarding our educational programs and services using email, telephone or text - including our use of automated technology for calls and periodic texts to the wireless number you provide. Message and data rates may apply. This consent is not required to purchase good or services and you may always email us directly, including to opt out, at [email protected] .

Home Blog Why is Art History Important? 12 Key Lessons

Why is Art History Important? 12 Key Lessons

December 8, 2023

Contributing Author: Dr. James Hutson

31 mins read

What comes to mind when you hear the term "Art History"? Perhaps you envision iconic works like the Mona Lisa or the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel. Maybe your imagination leans more contemporary, bringing up associations with Dan Brown novels or the latest auction at Sotheby's. Regardless, art history offers us far more than a collection of "greatest hits" or objects of market value; it provides a panoramic view of humanity itself, a timeline textured with the very fibers of human experience.

The History of Art History

Art history as a discipline has its own colorful past, rich with its own set of pioneers and landmark moments. One might start the journey with Giorgio Vasari, an Italian painter and architect, who wrote biographies of famous artists in his seminal work Lives of the Artists in the 16th century. Fast-forward to the 18th century and we encounter Johann Winckelmann, often hailed as the father of art history. He shifted the discipline towards scientific rigor and the understanding of art within its historical context, catalyzed in part by the archaeological excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii. These unearthed cities, frozen in time by the ash of Mount Vesuvius, offered a tangible link to antiquity and ignited a fascination with the art and culture of the past.

By the 19th century, art history became institutionalized in German universities, moving from the realm of personal inquiry and connoisseurship to an academic discipline. This trend later crossed the Atlantic, finding a home in universities across the United States, shaping the study of art history into the multi-faceted field we know today.

And what a multi-faceted field it is! Art history didn't just sprout from a singular interest in visual artifacts. It's an interdisciplinary mecca that integrates elements of history, sociology, connoisseurship, archaeology, and even philosophy and psychology; it extends across multiple domains, providing a holistic understanding of artworks within the fabric of the societies that produced them.

So, as we prepare to explore the 12 key lessons that make art history an indispensable realm of study, let's keep in mind that we're not just talking about pictures on a wall or statues in a museum. We're delving into a discipline that captures the essence of humanity, one that has been shaped by a tapestry of influences as diverse and complex as the artworks it studies. Are you ready to dive in?

1. The Culture Canvas: Unveiling Identity Through Art

Here we explore how art is not just a product of culture but an influencer as well. Understanding art can serve as a gateway to comprehending the values, norms, and practices of different civilizations. For instance, when gazing upon an artwork, be it a delicate Japanese ukiyo-e print or the vibrant geometric patterns of an African kente cloth , we're not just observing colors, shapes, and forms; we're diving deep into a narrative – a tale that speaks of traditions, beliefs, societal norms, and historical events. Each piece of art stands as a sentinel, guarding the stories of the civilization it stems from, allowing us to catch a glimpse of its cultural soul.

Renaissance Reflections: The Mirrors of European Soul

Journey now to Renaissance Europe, a period marked by a fervent revival of art, science, and intellect, bridging the gap between the medieval and modern eras.

The Last Supper - A Feast for the Eyes and Soul

Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper is not just a religious depiction of Jesus Christ's final meal with his disciples. It’s a cultural emblem of its time. Set in the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, this masterpiece goes beyond its religious significance.

Look closely, and you'll see the careful play of light and shadow, the meticulous detailing of human expressions, and the geometric precision that structures the entire scene. Leonardo's choice to capture the exact moment when Jesus reveals that one of his disciples will betray him showcases not just his artistic brilliance but also the intellectual spirit of the Renaissance. The astonishment, despair, and confusion depicted in each disciple's reaction are a testament to the era's emphasis on individualism, human emotion, and realism.

Furthermore, the use of linear perspective, with all orthogonal lines converging on Christ, underlines the union of art and science, a hallmark of the Renaissance period. This artwork isn't just a religious scene; it’s a snapshot of European culture during the 15th century, embodying its values, its newfound methodologies, and its inexorable drive towards realism and human-centric narratives.

Through The Last Supper , we see a Europe on the cusp of change, moving from the shackles of the medieval era to the enlightening waves of modernity. It's a vivid reminder that Western art, much like its global counterparts, serves as a cultural compass, guiding us through the annals of history, one brushstroke at a time.

The Delicate Dance of Indian Miniatures

But looking globally, art history is able to tell us so much about other cultures. Consider the intricate miniatures from India . These dainty, detailed paintings often narrate tales from ancient epics, royal court life, or even the delicate nuances of nature. But they do more than just tell a story. The radiant hues, the meticulous details of clothing, and the ornate backgrounds reveal a culture that values detail, storytelling, and the interplay of nature and humans. Through these miniatures, we not only see the scenes they depict but also grasp the values of the bygone Mughal or Rajput courts.

The Resounding Echoes of Australian Aboriginal Art

Shift your gaze to the mesmerizing dot paintings of Australian Aboriginal art . At first glance, they might seem like abstract patterns, but these art forms are, in reality, topographical maps, ancestral tales, and spiritual stories. The repetitive use of dots and earthly colors paints a picture of a culture deeply rooted in its land and legends. Each artwork is not just an aesthetic endeavor but a testament to the timeless bond between the Aboriginal people and the Australian terrain.

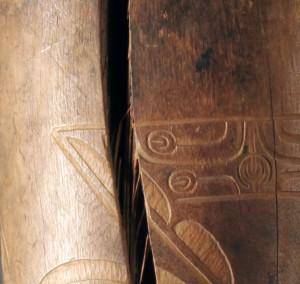

The Majestic Totems of the Pacific Northwest

Now, journey to the Pacific Northwest, where the indigenous peoples craft towering totem poles. These aren't merely grand sculptures but layered narratives carved in wood. Every figure, whether it's an eagle, bear, or mythical being, holds significance, representing ancestry, history, and clan legends. The very act of erecting a totem pole is a communal endeavor, underscoring the culture's emphasis on community, nature, and spirituality.

These examples reinforce the notion that art is more than aesthetic pleasure. It's a window into the heart of cultures, a guide to the values and beliefs that shape civilizations. Through art, we unravel the rich tapestry of humanity, appreciating the unique threads that each culture weaves into this grand design. Whether you're an art aficionado or a curious observer, remember that behind every artwork lies a story, waiting to be told and understood. So, the next time you encounter a piece of art from a far-off land or a bygone era, pause and reflect, for you're about to embark on a journey into the very soul of a culture.

2. Emoticon of the Ages: Art as Humanity's Emotional Diary

How has art captured the collective emotional psyche across time? This section delves into how artworks serve as emotional touchstones, revealing the feelings and moods of different epochs.

Art has always been the voice of the silent, the expression of the inexpressible, and the visible form of the invisible. Across continents and centuries, it has faithfully chronicled the ever-evolving tapestry of human emotion, acting as a barometer for societal moods, collective fears, shared joys, and common dreams. Like an age-old diary filled with vibrant sketches, poignant colors, and soul-stirring narratives, art captures the heartbeat of humanity across eras.

The Somber Hues of The Dutch Golden Age

Journey back to 17th-century Netherlands, a period marked by great maritime and economic power but also political turmoil and socio-religious tensions. Artists like Johannes Vermeer and Rembrandt captured this duality beautifully. In paintings such as Girl with a Pearl Earring or The Night Watch, we witness a silent introspection and a deep contemplation. The play of light and shadow isn't just a technical achievement; it's an emotional dance, highlighting the juxtaposition of wealth and uncertainty, power and vulnerability.

Passion and Rebellion in Romanticism

Fast forward to the late 18th and early 19th century, and you'll find yourself in the embrace of Romanticism. Artists like Francisco Goya and Eugène Delacroix painted not just scenes but emotions. Goya's The Third of May 1808 isn't merely a depiction of the Spanish resistance to the Napoleonic regimes; it's a raw, unfiltered scream of despair, sacrifice, and defiance. The stark contrasts, the horrified faces, and the looming darkness encapsulate the pain and passion of a nation in turmoil.

Modern Angst and the Scream

No discussion on art as an emotional diary would be complete without Edvard Munch's The Scream. This iconic late nineteenth-century piece is more than a painting; it's an emotion manifested. The swirling skies, the distorted figure, and the haunting ambiance capture the anxiety, alienation, and existential dread of the modern age. At a time of rapid industrialization, urbanization, and societal change, Munch's masterpiece echoed the collective unease and dislocation many felt.

Art, in its myriad forms, serves as an emotional anchor, allowing us to feel, reflect upon, and understand the deep-seated emotions of epochs gone by. It's a mirror reflecting not just individual faces but the collective soul of society. Through it, we journey across the emotional landscapes of history, touching the joys, sorrows, hopes, and fears of generations past. As we stand before an artwork, we're not just spectators; we're time travelers, empathetically connected to the heartbeats of artists and societies from ages past.

3. Brushstrokes and Microscopes: Where Art and Science Converge

Innovation is not exclusive to the laboratory. Artists often pioneer techniques that echo scientific discoveries and technological innovations. This interconnection is the focus of this section.

Art and science, often perceived as polar opposites, are, in truth, two sides of the same coin. Both are driven by an insatiable curiosity, a desire to explore, understand, and represent the world around us. While one uses brushstrokes, the other employs microscopes, yet their trajectories often intersect, revealing astonishing synergies. The convergence of these disciplines has given birth to some of the most groundbreaking achievements in human history.

Renaissance and the Perfect Proportions

Perhaps no era exemplifies the marriage of art and science better than the Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci, a polymath, blurred the lines between artist and scientist. His anatomical sketches, based on detailed dissections, brought an unprecedented accuracy and vitality to his paintings. Consider his masterpiece, the Vitruvian Man . Here, art and anatomy meld to illustrate the ideal human proportions, echoing both the aesthetics of classical art and the precision of scientific observation.

The Play of Light: Impressionism meets Physics

Fast forward to the 19th century. The Impressionists, with their fascination for capturing fleeting moments, turned their eyes to the changing quality of light. Artists like Monet began experimenting with color, trying to represent how natural light interacts with objects at different times of the day. This artistic endeavor paralleled the scientific explorations of the time, as physicists dissected light's properties, leading to discoveries about its spectrum and wave nature. Monet's Haystacks series , portraying the same subject under various lighting conditions, can be seen as a visual representation of these scientific revelations.

The Digital Art Revolution: Pixels and Programs

In our contemporary age, the bond between art and science is perhaps most evident in the realm of digital art. Advances in computer technology and software development have given artists tools that would have seemed like magic just a few decades ago. Generative art, where algorithms dictate patterns, and virtual reality art installations, are just a few examples of how coding and artistic creativity come together to redefine the boundaries of expression.

The intertwining of art and science reminds us that human ingenuity knows no bounds. When brush meets beaker, and canvas converges with code, the results are nothing short of revolutionary. This synergy underscores a fundamental truth: our most profound achievements often arise when diverse fields of study intersect, illuminating our world in ways previously unimagined. In the dance of brushstrokes and microscopes, we see a testament to humanity's boundless capacity for innovation and creativity.

4. Canvas as Protest Sign: The Activism in Art

Art isn't always about beauty; it often serves to highlight social and political issues. From Picasso's Guernica to Banksy's street art , we look at how art can be a potent vehicle for change.

Throughout history, the art world has been a tempestuous stage where societal issues play out in color, form, and imagery. Beyond ornate frames and prestigious galleries, art becomes a formidable force when it transforms into a medium for activism. It speaks, protests, and sometimes shouts, challenging conventions and questioning societal norms. When art wears the cloak of activism, it becomes a catalyst for social change, awakening consciousness and mobilizing public opinion.

The Cries from Guernica

When the town of Guernica in Spain was bombed in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War, it wasn't just a tragedy; it was a brutal assault on civilians. Pablo Picasso responded to this atrocity not with words, but with brushstrokes. His mural-sized painting, "Guernica," is a chaotic panorama of anguish. The distorted figures, the agonized horse, and the fallen warrior serve as a poignant critique of the horrors of war. Every stroke serves as a cry against fascism, violence, and human suffering. Picasso's Guernica is more than a painting; it's a political statement, a protest, and a reminder of the cost of war.

Banksy's Walls of Awareness

In stark contrast to the grandeur of Picasso's murals, Banksy, the elusive street artist, uses the urban landscape as his canvas. With a unique blend of satire, dark humor, and stark imagery, Banksy's works tackle issues ranging from war and corruption to consumerism and poverty. Whether it's a girl letting go of a balloon in the shape of a heart or a protester throwing a bouquet instead of a Molotov cocktail, Banksy turns street corners into platforms for social commentary. His art isn't locked behind museum doors; it's out in the open, urging passersby to stop, think, and hopefully, act.

The AIDS Quilt: Stitching Stories of Loss

Art activism isn't confined to paintings alone. The NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt is a poignant example of how art can be a collective effort to mourn, remember, and protest. Launched in 1987, this quilt is a patchwork of thousands of individual panels, each commemorating a life lost to AIDS. Each square, lovingly stitched with names, dates, and personal symbols, stands as a testament to a life lost and the collective negligence of a society slow to respond to the AIDS epidemic. Displayed in its entirety on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the quilt became both a memorial and a potent call for more aggressive research, care, and understanding.

From large-scale paintings to guerrilla street art, and from quilts to sculptures, art's role as a voice of protest is undeniable. It not only reflects the world but also challenges and reshapes it. In its most activist form, art disrupts, questions, and compels us to confront uncomfortable truths, reminding us that beauty isn't just in aesthetics but also in the courage to demand change.

5. A Tapestry of Knowledge: Art in the Interdisciplinary Nexus

Can a painting be a historical document? Is a poem connected to a sculpture? This section elaborates on how art history is intertwined with literature, history, and other disciplines, creating a rich, interconnected web of knowledge.

In the vast universe of academia, subjects and disciplines are often likened to stars, each shining brightly in its own right. But just as stars form constellations, academic disciplines interconnect, creating patterns that tell a larger story. Art, with its vibrant strokes and intricate details, serves as a thread weaving through these constellations, binding them into a grand tapestry of interconnected knowledge.

Paintings as Pages of History

Consider Jacques-Louis David's iconic painting, The Death of Socrates. At first glance, it's a dramatic portrayal of the Athenian philosopher's final moments. But delve deeper, and you find a rich chronicle of the sociopolitical atmosphere of both ancient Athens and post-revolutionary France. The painting isn't merely an artistic representation; it's a bridge between art and history, inviting discussions on democracy, martyrdom, and political ethics.

The Romantic Movement: Where Poems Meet Paintings

The Romantic era, flourishing in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, saw a profound intermingling of art and literature. Wordsworth's poetic landscapes find echoes in Turner's ethereal paintings. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and Henry Fuseli's The Nightmare both explore the gothic, the sublime, and the boundaries of human ambition. Here, brushstrokes and pen strokes intertwine, each enhancing and amplifying the other's message.

Mythology in Mosaics: A Window to Ancient Beliefs

Wander through the ruins of ancient Pompeii or the halls of Istanbul's Hagia Sophia, and you'll find stunning mosaics depicting gods, goddesses, and mythological tales. These intricate tile works are not just decorative art; they offer insights into the spiritual beliefs, cosmologies, and moral codes of ancient civilizations. Interpreting these mosaics becomes an interdisciplinary journey, merging art history with religious studies and cultural anthropology.

In this multidisciplinary dance, art history emerges as a pivotal partner, gracefully leading its counterparts and enriching the academic waltz. It encourages us to look beyond siloed knowledge, to see the interconnectedness of human endeavors, and to appreciate the nuanced, multifaceted nature of our shared heritage. In the nexus of disciplines, art history stands as a testament to the intertwined nature of human knowledge, reminding us that in unity, there is depth, richness, and unparalleled beauty.

6. Art Without Borders: The Universal Language of Creativity

Art is an international affair, its influence and inspiration often traversing geographical and cultural boundaries. Here, we explore how art serves as a universal language, fostering global communication and understanding.

In a world marked by diverse languages, traditions, and beliefs, there remains one constant: the universal resonance of art. Whether it's a haunting melody from a distant land, the graceful arc of a dancer's leap, or the silent profundity of a painted canvas, art has an innate ability to transcend borders, touch souls, and unite people from all walks of life.

The Silk Road: A Cultural Exchange Beyond Trade

Long before globalization became a buzzword, the ancient Silk Road facilitated not just the exchange of goods, but also of ideas, beliefs, and artistic expressions. Chinese silks, Persian miniatures, and Greek sculptures converged and intermingled on this vast network. This wasn't merely a trade route; it was a conduit of cultural dialogue, where a Chinese vase might be inspired by Persian motifs, or a Central Asian tapestry might depict scenes from Greek mythology.

The Global Appeal of Japanese Anime

Venture into the world of contemporary pop culture, and you'll be hard-pressed not to notice the global dominance of Japanese anime. What began as a local art form has now captured imaginations worldwide. Anime series, with their intricate plots and unique aesthetics, resonate with audiences from North America to Africa. They foster cross-cultural dialogues, as fans across the world discuss themes, characters, and narratives, united in their shared appreciation.

Biennales and Art Festivals: A Global Artistic Melting Pot