Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a literary analysis essay | A step-by-step guide

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on January 30, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 14, 2023.

Literary analysis means closely studying a text, interpreting its meanings, and exploring why the author made certain choices. It can be applied to novels, short stories, plays, poems, or any other form of literary writing.

A literary analysis essay is not a rhetorical analysis , nor is it just a summary of the plot or a book review. Instead, it is a type of argumentative essay where you need to analyze elements such as the language, perspective, and structure of the text, and explain how the author uses literary devices to create effects and convey ideas.

Before beginning a literary analysis essay, it’s essential to carefully read the text and c ome up with a thesis statement to keep your essay focused. As you write, follow the standard structure of an academic essay :

- An introduction that tells the reader what your essay will focus on.

- A main body, divided into paragraphs , that builds an argument using evidence from the text.

- A conclusion that clearly states the main point that you have shown with your analysis.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: reading the text and identifying literary devices, step 2: coming up with a thesis, step 3: writing a title and introduction, step 4: writing the body of the essay, step 5: writing a conclusion, other interesting articles.

The first step is to carefully read the text(s) and take initial notes. As you read, pay attention to the things that are most intriguing, surprising, or even confusing in the writing—these are things you can dig into in your analysis.

Your goal in literary analysis is not simply to explain the events described in the text, but to analyze the writing itself and discuss how the text works on a deeper level. Primarily, you’re looking out for literary devices —textual elements that writers use to convey meaning and create effects. If you’re comparing and contrasting multiple texts, you can also look for connections between different texts.

To get started with your analysis, there are several key areas that you can focus on. As you analyze each aspect of the text, try to think about how they all relate to each other. You can use highlights or notes to keep track of important passages and quotes.

Language choices

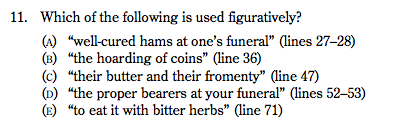

Consider what style of language the author uses. Are the sentences short and simple or more complex and poetic?

What word choices stand out as interesting or unusual? Are words used figuratively to mean something other than their literal definition? Figurative language includes things like metaphor (e.g. “her eyes were oceans”) and simile (e.g. “her eyes were like oceans”).

Also keep an eye out for imagery in the text—recurring images that create a certain atmosphere or symbolize something important. Remember that language is used in literary texts to say more than it means on the surface.

Narrative voice

Ask yourself:

- Who is telling the story?

- How are they telling it?

Is it a first-person narrator (“I”) who is personally involved in the story, or a third-person narrator who tells us about the characters from a distance?

Consider the narrator’s perspective . Is the narrator omniscient (where they know everything about all the characters and events), or do they only have partial knowledge? Are they an unreliable narrator who we are not supposed to take at face value? Authors often hint that their narrator might be giving us a distorted or dishonest version of events.

The tone of the text is also worth considering. Is the story intended to be comic, tragic, or something else? Are usually serious topics treated as funny, or vice versa ? Is the story realistic or fantastical (or somewhere in between)?

Consider how the text is structured, and how the structure relates to the story being told.

- Novels are often divided into chapters and parts.

- Poems are divided into lines, stanzas, and sometime cantos.

- Plays are divided into scenes and acts.

Think about why the author chose to divide the different parts of the text in the way they did.

There are also less formal structural elements to take into account. Does the story unfold in chronological order, or does it jump back and forth in time? Does it begin in medias res —in the middle of the action? Does the plot advance towards a clearly defined climax?

With poetry, consider how the rhyme and meter shape your understanding of the text and your impression of the tone. Try reading the poem aloud to get a sense of this.

In a play, you might consider how relationships between characters are built up through different scenes, and how the setting relates to the action. Watch out for dramatic irony , where the audience knows some detail that the characters don’t, creating a double meaning in their words, thoughts, or actions.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Your thesis in a literary analysis essay is the point you want to make about the text. It’s the core argument that gives your essay direction and prevents it from just being a collection of random observations about a text.

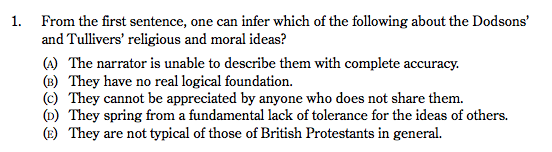

If you’re given a prompt for your essay, your thesis must answer or relate to the prompt. For example:

Essay question example

Is Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” a religious parable?

Your thesis statement should be an answer to this question—not a simple yes or no, but a statement of why this is or isn’t the case:

Thesis statement example

Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” is not a religious parable, but a story about bureaucratic alienation.

Sometimes you’ll be given freedom to choose your own topic; in this case, you’ll have to come up with an original thesis. Consider what stood out to you in the text; ask yourself questions about the elements that interested you, and consider how you might answer them.

Your thesis should be something arguable—that is, something that you think is true about the text, but which is not a simple matter of fact. It must be complex enough to develop through evidence and arguments across the course of your essay.

Say you’re analyzing the novel Frankenstein . You could start by asking yourself:

Your initial answer might be a surface-level description:

The character Frankenstein is portrayed negatively in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein .

However, this statement is too simple to be an interesting thesis. After reading the text and analyzing its narrative voice and structure, you can develop the answer into a more nuanced and arguable thesis statement:

Mary Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as.

Remember that you can revise your thesis statement throughout the writing process , so it doesn’t need to be perfectly formulated at this stage. The aim is to keep you focused as you analyze the text.

Finding textual evidence

To support your thesis statement, your essay will build an argument using textual evidence —specific parts of the text that demonstrate your point. This evidence is quoted and analyzed throughout your essay to explain your argument to the reader.

It can be useful to comb through the text in search of relevant quotations before you start writing. You might not end up using everything you find, and you may have to return to the text for more evidence as you write, but collecting textual evidence from the beginning will help you to structure your arguments and assess whether they’re convincing.

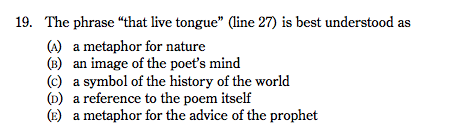

To start your literary analysis paper, you’ll need two things: a good title, and an introduction.

Your title should clearly indicate what your analysis will focus on. It usually contains the name of the author and text(s) you’re analyzing. Keep it as concise and engaging as possible.

A common approach to the title is to use a relevant quote from the text, followed by a colon and then the rest of your title.

If you struggle to come up with a good title at first, don’t worry—this will be easier once you’ve begun writing the essay and have a better sense of your arguments.

“Fearful symmetry” : The violence of creation in William Blake’s “The Tyger”

The introduction

The essay introduction provides a quick overview of where your argument is going. It should include your thesis statement and a summary of the essay’s structure.

A typical structure for an introduction is to begin with a general statement about the text and author, using this to lead into your thesis statement. You might refer to a commonly held idea about the text and show how your thesis will contradict it, or zoom in on a particular device you intend to focus on.

Then you can end with a brief indication of what’s coming up in the main body of the essay. This is called signposting. It will be more elaborate in longer essays, but in a short five-paragraph essay structure, it shouldn’t be more than one sentence.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, protagonist Victor Frankenstein is a stable representation of the callous ambition of modern science throughout the novel. This essay, however, argues that far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as. This essay begins by exploring the positive portrayal of Frankenstein in the first volume, then moves on to the creature’s perception of him, and finally discusses the third volume’s narrative shift toward viewing Frankenstein as the creature views him.

Some students prefer to write the introduction later in the process, and it’s not a bad idea. After all, you’ll have a clearer idea of the overall shape of your arguments once you’ve begun writing them!

If you do write the introduction first, you should still return to it later to make sure it lines up with what you ended up writing, and edit as necessary.

The body of your essay is everything between the introduction and conclusion. It contains your arguments and the textual evidence that supports them.

Paragraph structure

A typical structure for a high school literary analysis essay consists of five paragraphs : the three paragraphs of the body, plus the introduction and conclusion.

Each paragraph in the main body should focus on one topic. In the five-paragraph model, try to divide your argument into three main areas of analysis, all linked to your thesis. Don’t try to include everything you can think of to say about the text—only analysis that drives your argument.

In longer essays, the same principle applies on a broader scale. For example, you might have two or three sections in your main body, each with multiple paragraphs. Within these sections, you still want to begin new paragraphs at logical moments—a turn in the argument or the introduction of a new idea.

Robert’s first encounter with Gil-Martin suggests something of his sinister power. Robert feels “a sort of invisible power that drew me towards him.” He identifies the moment of their meeting as “the beginning of a series of adventures which has puzzled myself, and will puzzle the world when I am no more in it” (p. 89). Gil-Martin’s “invisible power” seems to be at work even at this distance from the moment described; before continuing the story, Robert feels compelled to anticipate at length what readers will make of his narrative after his approaching death. With this interjection, Hogg emphasizes the fatal influence Gil-Martin exercises from his first appearance.

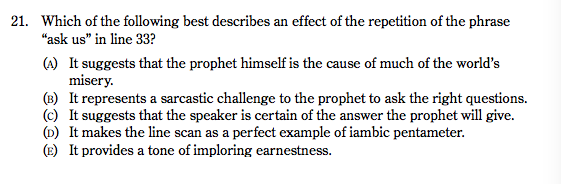

Topic sentences

To keep your points focused, it’s important to use a topic sentence at the beginning of each paragraph.

A good topic sentence allows a reader to see at a glance what the paragraph is about. It can introduce a new line of argument and connect or contrast it with the previous paragraph. Transition words like “however” or “moreover” are useful for creating smooth transitions:

… The story’s focus, therefore, is not upon the divine revelation that may be waiting beyond the door, but upon the mundane process of aging undergone by the man as he waits.

Nevertheless, the “radiance” that appears to stream from the door is typically treated as religious symbolism.

This topic sentence signals that the paragraph will address the question of religious symbolism, while the linking word “nevertheless” points out a contrast with the previous paragraph’s conclusion.

Using textual evidence

A key part of literary analysis is backing up your arguments with relevant evidence from the text. This involves introducing quotes from the text and explaining their significance to your point.

It’s important to contextualize quotes and explain why you’re using them; they should be properly introduced and analyzed, not treated as self-explanatory:

It isn’t always necessary to use a quote. Quoting is useful when you’re discussing the author’s language, but sometimes you’ll have to refer to plot points or structural elements that can’t be captured in a short quote.

In these cases, it’s more appropriate to paraphrase or summarize parts of the text—that is, to describe the relevant part in your own words:

The conclusion of your analysis shouldn’t introduce any new quotations or arguments. Instead, it’s about wrapping up the essay. Here, you summarize your key points and try to emphasize their significance to the reader.

A good way to approach this is to briefly summarize your key arguments, and then stress the conclusion they’ve led you to, highlighting the new perspective your thesis provides on the text as a whole:

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

By tracing the depiction of Frankenstein through the novel’s three volumes, I have demonstrated how the narrative structure shifts our perception of the character. While the Frankenstein of the first volume is depicted as having innocent intentions, the second and third volumes—first in the creature’s accusatory voice, and then in his own voice—increasingly undermine him, causing him to appear alternately ridiculous and vindictive. Far from the one-dimensional villain he is often taken to be, the character of Frankenstein is compelling because of the dynamic narrative frame in which he is placed. In this frame, Frankenstein’s narrative self-presentation responds to the images of him we see from others’ perspectives. This conclusion sheds new light on the novel, foregrounding Shelley’s unique layering of narrative perspectives and its importance for the depiction of character.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, August 14). How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved March 23, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/literary-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to write a narrative essay | example & tips, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

The Ten Best American Essays Since 1950, According to Robert Atwan

in Books , Literature | November 15th, 2012 3 Comments

“Essays can be lots of things, maybe too many things,” writes Atwan in his foreward to the 2012 installment in the Best American series, “but at the core of the genre is an unmistakable receptivity to the ever-shifting processes of our minds and moods. If there is any essential characteristic we can attribute to the essay, it may be this: that the truest examples of the form enact that ever-shifting process, and in that enactment we can find the basis for the essay’s qualification to be regarded seriously as imaginative literature and the essayist’s claim to be taken seriously as a creative writer.”

In 2001 Atwan and Joyce Carol Oates took on the daunting task of tracing that ever-shifting process through the previous 100 years for The Best American Essays of the Century . Recently Atwan returned with a more focused selection for Publishers Weekly : “The Top 10 Essays Since 1950.” To pare it all down to such a small number, Atwan decided to reserve the “New Journalism” category, with its many memorable works by Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Michael Herr and others, for some future list. He also made a point of selecting the best essays , as opposed to examples from the best essayists. “A list of the top ten essayists since 1950 would feature some different writers.”

We were interested to see that six of the ten best essays are available for free reading online. Here is Atwan’s list, along with links to those essays that are on the Web:

- James Baldwin, “Notes of a Native Son,” 1955 (Read it here .)

- Norman Mailer, “The White Negro,” 1957 (Read it here .)

- Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp,’ ” 1964 (Read it here .)

- John McPhee, “The Search for Marvin Gardens,” 1972 (Read it here with a subscription.)

- Joan Didion, “The White Album,” 1979

- Annie Dillard, “Total Eclipse,” 1982

- Phillip Lopate, “Against Joie de Vivre,” 1986 (Read it here .)

- Edward Hoagland, “Heaven and Nature,” 1988

- Jo Ann Beard, “The Fourth State of Matter,” 1996 (Read it here .)

- David Foster Wallace, “Consider the Lobster,” 2004 (Read it here in a version different from the one published in his 2005 book of the same name.)

“To my mind,” writes Atwan in his article, “the best essays are deeply personal (that doesn’t necessarily mean autobiographical) and deeply engaged with issues and ideas. And the best essays show that the name of the genre is also a verb, so they demonstrate a mind in process–reflecting, trying-out, essaying.”

To read more of Atwan’s commentary, see his article in Publishers Weekly .

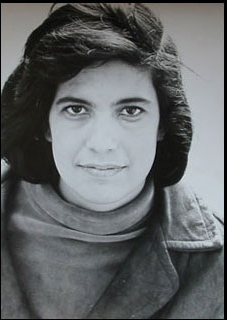

The photo above of Susan Sontag was taken by Peter Hujar in 1966.

Related Content:

30 Free Essays & Stories by David Foster Wallace on the Web

by Mike Springer | Permalink | Comments (3) |

Related posts:

Comments (3), 3 comments so far.

Check out Michael Ventura’s HEAR THAT LONG SNAKE MOAN: The VooDoo Origins of Rock n’ Roll

Wow I think there’s other greater ones out there. Just need to find them.

Boise mulberry bags uk http://www.cool-mulberrybags.info/

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Beat & Tweets

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Book Lists By

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Favorite Movies

- Kurosawa's 100

- David Lynch

- Werner Herzog

- Woody Allen

- Wes Anderson

- Luis Buñuel

- Roger Ebert

- Susan Sontag

- Scorsese Foreign Films

- Philosophy Films

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

©2006-2024 Open Culture, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advertise with Us

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

What Makes a Great American Essay?

Talking to phillip lopate about thwarted expectations, emerson, and the 21st-century essay boom.

Phillip Lopate spoke to Literary Hub about the new anthology he has edited, The Glorious American Essay . He recounts his own development from an “unpatriotic” young man to someone, later in life, who would embrace such writers as Ralph Waldo Emerson, who personified the simultaneous darkness and optimism underlying the history of the United States. Lopate looks back to the Puritans and forward to writers like Wesley Yang and Jia Tolentino. What is the next face of the essay form?

Literary Hub: We’re at a point, politically speaking, when disagreements about the meaning of the word “American” are particularly vehement. What does the term mean to you in 2020? How has your understanding of the word evolved?

Phillip Lopate : First of all, I am fully aware that even using the word “American” to refer only to the United States is something of an insult to Latin American countries, and if I had said “North American” to signify the US, that might have offended Canadians. Still, I went ahead and put “American” in the title as a synonym for the United States, because I wanted to invoke that powerful positive myth of America as an idea, a democratic aspiration for the world, as well as an imperialist juggernaut replete with many unresolved social inequities, in negative terms.

I will admit that when I was younger, I tended to be very unpatriotic and critical of my country, although once I started to travel abroad and witness authoritarian regimes like Spain under Franco, I could never sign on to the fear that a fascist US was just around the corner. I came to the conclusion that we have our faults, but our virtues as well.

The more I’ve become interested in American history, the more I’ve seen how today’s problems and possible solutions are nothing new, but keep returning in cycles: economic booms and recessions, anti-immigrant sentiment, regional competition, racist Jim Crow policies followed by human rights advances, vigorous federal regulations and pendulum swings away from governmental intervention.

Part of the thrill in putting together this anthology was to see it operating simultaneously on two tracks: first, it would record the development of a literary form that I loved, the essay, as it evolved over 400 years in this country. At the same time, it would be a running account of the history of the United States, in the hands of these essayists who were contending, directly or indirectly, with the pressing problems of their day. The promise of America was always being weighed against its failure to live up to that standard.

For instance, we have the educator John Dewey arguing for a more democratic schoolhouse, the founder of the settlement house movement Jane Addams analyzing the alienation of young people in big cities, the progressive writer Randolph Bourne describing his own harsh experiences as a disabled person, the feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton advocating for women’s rights, and W. E. B. Dubois and James Weldon Johnson eloquently addressing racial injustice.

Issues of identity, gender and intersectionality were explored by writers such as Richard Rodriguez, Audre Lorde, Leonard Michaels and N. Scott Momaday, sometimes with touches of irony and self-scrutiny, which have always been assets of the essay form.

LH : If a publisher had asked us to compile an anthology of 100 representative American essays, we wouldn’t know where to start. How did you? What were your criteria?

PL : I thought I knew the field fairly well to begin with, having edited the best-selling Art of the Personal Essay in 1994, taught the form for decades, served on book award juries and so on. But once I started researching and collecting material, I discovered that I had lots of gaps, partly because the mandate I had set for myself was so sweeping.

This time I would not restrict myself to personal essays but would include critical essays, impersonal essays, speeches that were in essence essays (such as George Washington’s Farewell Address or Martin Luther King, Jr’s sermon on Vietnam), letters that functioned as essays (Frederick Douglass’s Letter to His Master).

I wanted to expand the notion of what is an essay, to include, for instance, polemics such as Thomas Paine’s Common Sense , or one of the Federalist Papers; newspaper columnists (Fanny Fern, Christopher Morley); humorists (James Thurber, Finley Peter Dunne, Dorothy Parker).

But it also occurred to me that fine essayists must exist in every discipline, not only literature, which sent me on a hunt that took me to cultural criticism (Clement Greenberg, Kenneth Burke), theology (Paul Tillich), food writing (M.F. K. Fisher), geography (John Brinkerhoff Jackson), nature writing (John Muir, John Burroughs, Edward Abbey), science writing (Loren Eiseley, Lewis Thomas), philosophy (George Santayana). My one consistent criterion was that the essay be lively, engaging and intelligently written. In short, I had to like it myself.

Of course I would need to include the best-known practitioners of the American essay—Emerson, Thoreau, Mencken, Baldwin, Sontag, etc.—and was happy to do so. As it turned out, most of the masters of American fiction and poetry also tried their hand successfully at essay-writing, which meant including Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman, Theodore Dreiser, Willa Cather, Flannery O’Connor, Ralph Ellison. . .

But I was also eager to uncover powerful if almost forgotten voices such as John Jay Chapman, Agnes Repplier, Randolph Bourne, Mary Austin, or buried treasures such as William Dean Howells’ memoir essay of his days working in his father’s printing shop.

Finally, I wanted to show a wide variety of formal approaches, since the essay is by its very nature and nomenclature an experiment, which brought me to Gertrude Stein and Wayne Koestenbaum. Equally important, I was aided in all these searches by colleagues and friends who kept suggesting other names. For every fertile lead, probably four resulted in dead ends. Meanwhile, I was having a real learning adventure.

LH: Do you have a personal favorite among American essayists? If so, what appeals to you the most about them?

PL : I do. It’s Ralph Waldo Emerson. He was the one who cleared the ground for US essayists, in his famous piece, “The American Scholar,” which called on us to free ourselves from slavish imitation of European models and to think for ourselves. So much American thought grows out of Emerson, or is in contention with Emerson, even if that debt is sometimes unacknowledged or unconscious.

What I love about Emerson is his density of thought, and the surprising twists and turns that result from it. I can read an essay of his like “Experience” (the one I included in this anthology) a hundred times and never know where it’s going next. If it was said of Emily Dickenson that her poems made you feel like the top of your head was spinning, that’s what I feel in reading Emerson. He has a playful skepticism, a knack for thinking against himself. Each sentence starts a new rabbit of thought scampering off. He’s difficult but worth the trouble.

I once asked Susan Sontag who her favorite American essayist was, and she replied “Emerson, of course.” It’s no surprise that Nietzsche revered Emerson, as did Carlyle, and in our own time, Harold Bloom, Stanley Cavell, Richard Poirier. But here’s a confession: it took me awhile to come around to him.

I found his preacher’s manner and abstractions initially off-putting, I wasn’t sure about the character of the man who was speaking to me. Then I read his Notebooks and the mystery was cracked: suddenly I was able to follow essays such as “Circles” with pure pleasure, seeing as I could the darkness and complexity underneath the optimism.

LH: You make the interesting decision to open the anthology with an essay written in 1726, 50 years before the founding of the republic. Why?

PL : I wanted to start the anthology with the first fully-formed essayistic voices in this land, which turned out to belong to the Puritans. Regardless of the negative associations of zealous prudishness that have come to attach to the adjective “puritanical,” those American colonies founded as religious settlements were spearheaded by some remarkably learned and articulate spokespersons, whose robust prose enriched the American literary canon.

Cotton Mather and Jonathan Edwards were highly cultivated readers, familiar with the traditions of essay-writing, Montaigne and the English, and with the latest science, even as they inveighed against witchcraft. I will admit that it also amused me to open the book with Cotton Mather, a prescriptive, strait-is-the-gate character, and end it with Zadie Smith, who is not only bi-racial but bi-national, dividing her year between London and New York, and whose openness to self-doubt is signaled by her essay collection title, Changing My Mind .

The next group of writers I focused on were the Founding Fathers, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, and a foundational feminist, Judith Sargent Murray, who wrote the 1790 essay “On the Equality of the Sexes.” These authors, whose essays preceded, occurred during or immediately followed the founding of the republic, were in some ways the opposite of the Puritans, being for the most part Deists or secular followers of the Enlightenment.

Their attraction to reasoned argument and willingness to entertain possible objections to their points of view inspired a vigorous strand of American essay-writing. So, while we may fix the founding of the United States to a specific year, the actual culture and literature of the country book-ended that date.

LH: You end with Zadie Smith’s “Speaking in Tongues,” published in 2008. Which essay in the last 12 years would be your 101st selection?

PL : Funny you should ask. As it happens, I am currently putting the finishing touches on another anthology, this one entirely devoted to the Contemporary (i.e., 21st century) American Essay. I have been immersed in reading younger, up-and-coming writers, established mid-career writers, and some oldsters who are still going strong (Janet Malcolm, Vivian Gornick, Barry Lopez, John McPhee, for example).

It would be impossible for me to single out any one contemporary essayist, as they are all in different ways contributing to the stew, but just to name some I’ve been tracking recently: Meghan Daum, Maggie Nelson, Sloane Crosley, Eula Biss, Charles D’Ambrosio, Teju Cole, Lia Purpura, John D’Agata, Samantha Irby, Anne Carson, Alexander Chee, Aleksander Hemon, Hilton Als, Mary Cappello, Bernard Cooper, Leslie Jamison, Laura Kipnis, Rivka Galchen, Emily Fox Gordon, Darryl Pinckney, Yiyun Li, David Lazar, Lynn Freed, Ander Monson, David Shields, Rebecca Solnit, John Jeremiah Sullivan, Eileen Myles, Amy Tan, Jonathan Lethem, Chelsea Hodson, Ross Gay, Jia Tolentino, Jenny Boully, Durga Chew-Bose, Brian Blanchfield, Thomas Beller, Terry Castle, Wesley Yang, Floyd Skloot, David Sedaris. . .

Such a banquet of names speaks to the intergenerational appeal of the form. We’re going through a particularly rich time for American essays: especially compared to, 20 years ago, when editors wouldn’t even dare put the word “essays” on the cover, but kept trying to package these variegated assortments as single-theme discourses, we’ve seen many collections that have been commercially successful and attracted considerable critical attention.

It has something to do with the current moment, which has everyone more than a little confused and therefore trusting more than ever those strong individual voices that are willing to cop to their subjective fears, anxieties, doubts and ecstasies.

__________________________________

The Glorious American Essay , edited by Phillip Lopate, is available now.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Phillip Lopate

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Recent History: Lessons From Obama, Both Cautionary and Hopeful

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

12.14: Sample Student Literary Analysis Essays

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 40514

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

The following examples are essays where student writers focused on close-reading a literary work.

While reading these examples, ask yourself the following questions:

- What is the essay's thesis statement, and how do you know it is the thesis statement?

- What is the main idea or topic sentence of each body paragraph, and how does it relate back to the thesis statement?

- Where and how does each essay use evidence (quotes or paraphrase from the literature)?

- What are some of the literary devices or structures the essays analyze or discuss?

- How does each author structure their conclusion, and how does their conclusion differ from their introduction?

Example 1: Poetry

Victoria Morillo

Instructor Heather Ringo

3 August 2022

How Nguyen’s Structure Solidifies the Impact of Sexual Violence in “The Study”

Stripped of innocence, your body taken from you. No matter how much you try to block out the instance in which these two things occurred, memories surface and come back to haunt you. How does a person, a young boy , cope with an event that forever changes his life? Hieu Minh Nguyen deconstructs this very way in which an act of sexual violence affects a survivor. In his poem, “The Study,” the poem's speaker recounts the year in which his molestation took place, describing how his memory filters in and out. Throughout the poem, Nguyen writes in free verse, permitting a structural liberation to become the foundation for his message to shine through. While he moves the readers with this poignant narrative, Nguyen effectively conveys the resulting internal struggles of feeling alone and unseen.

The speaker recalls his experience with such painful memory through the use of specific punctuation choices. Just by looking at the poem, we see that the first period doesn’t appear until line 14. It finally comes after the speaker reveals to his readers the possible, central purpose for writing this poem: the speaker's molestation. In the first half, the poem makes use of commas, em dashes, and colons, which lends itself to the idea of the speaker stringing along all of these details to make sense of this time in his life. If reading the poem following the conventions of punctuation, a sense of urgency is present here, as well. This is exemplified by the lack of periods to finalize a thought; and instead, Nguyen uses other punctuation marks to connect them. Serving as another connector of thoughts, the two em dashes give emphasis to the role memory plays when the speaker discusses how “no one [had] a face” during that time (Nguyen 9-11). He speaks in this urgent manner until the 14th line, and when he finally gets it off his chest, the pace of the poem changes, as does the more frequent use of the period. This stream-of-consciousness-like section when juxtaposed with the latter half of the poem, causes readers to slow down and pay attention to the details. It also splits the poem in two: a section that talks of the fogginess of memory then transitions into one that remembers it all.

In tandem with the fluctuating nature of memory, the utilization of line breaks and word choice help reflect the damage the molestation has had. Within the first couple of lines of the poem, the poem demands the readers’ attention when the line breaks from “floating” to “dead” as the speaker describes his memory of Little Billy (Nguyen 1-4). This line break averts the readers’ expectation of the direction of the narrative and immediately shifts the tone of the poem. The break also speaks to the effect his trauma has ingrained in him and how “[f]or the longest time,” his only memory of that year revolves around an image of a boy’s death. In a way, the speaker sees himself in Little Billy; or perhaps, he’s representative of the tragic death of his boyhood, how the speaker felt so “dead” after enduring such a traumatic experience, even referring to himself as a “ghost” that he tries to evict from his conscience (Nguyen 24). The feeling that a part of him has died is solidified at the very end of the poem when the speaker describes himself as a nine-year-old boy who’s been “fossilized,” forever changed by this act (Nguyen 29). By choosing words associated with permanence and death, the speaker tries to recreate the atmosphere (for which he felt trapped in) in order for readers to understand the loneliness that came as a result of his trauma. With the assistance of line breaks, more attention is drawn to the speaker's words, intensifying their importance, and demanding to be felt by the readers.

Most importantly, the speaker expresses eloquently, and so heartbreakingly, about the effect sexual violence has on a person. Perhaps what seems to be the most frustrating are the people who fail to believe survivors of these types of crimes. This is evident when he describes “how angry” the tenants were when they filled the pool with cement (Nguyen 4). They seem to represent how people in the speaker's life were dismissive of his assault and who viewed his tragedy as a nuisance of some sorts. This sentiment is bookended when he says, “They say, give us details , so I give them my body. / They say, give us proof , so I give them my body,” (Nguyen 25-26). The repetition of these two lines reinforces the feeling many feel in these scenarios, as they’re often left to deal with trying to make people believe them, or to even see them.

It’s important to recognize how the structure of this poem gives the speaker space to express the pain he’s had to carry for so long. As a characteristic of free verse, the poem doesn’t follow any structured rhyme scheme or meter; which in turn, allows him to not have any constraints in telling his story the way he wants to. The speaker has the freedom to display his experience in a way that evades predictability and engenders authenticity of a story very personal to him. As readers, we abandon anticipating the next rhyme, and instead focus our attention to the other ways, like his punctuation or word choice, in which he effectively tells his story. The speaker recognizes that some part of him no longer belongs to himself, but by writing “The Study,” he shows other survivors that they’re not alone and encourages hope that eventually, they will be freed from the shackles of sexual violence.

Works Cited

Nguyen, Hieu Minh. “The Study” Poets.Org. Academy of American Poets, Coffee House Press, 2018, https://poets.org/poem/study-0 .

Example 2: Fiction

Todd Goodwin

Professor Stan Matyshak

Advanced Expository Writing

Sept. 17, 20—

Poe’s “Usher”: A Mirror of the Fall of the House of Humanity

Right from the outset of the grim story, “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Edgar Allan Poe enmeshes us in a dark, gloomy, hopeless world, alienating his characters and the reader from any sort of physical or psychological norm where such values as hope and happiness could possibly exist. He fatalistically tells the story of how a man (the narrator) comes from the outside world of hope, religion, and everyday society and tries to bring some kind of redeeming happiness to his boyhood friend, Roderick Usher, who not only has physically and psychologically wasted away but is entrapped in a dilapidated house of ever-looming terror with an emaciated and deranged twin sister. Roderick Usher embodies the wasting away of what once was vibrant and alive, and his house of “insufferable gloom” (273), which contains his morbid sister, seems to mirror or reflect this fear of death and annihilation that he most horribly endures. A close reading of the story reveals that Poe uses mirror images, or reflections, to contribute to the fatalistic theme of “Usher”: each reflection serves to intensify an already prevalent tone of hopelessness, darkness, and fatalism.

It could be argued that the house of Roderick Usher is a “house of mirrors,” whose unpleasant and grim reflections create a dark and hopeless setting. For example, the narrator first approaches “the melancholy house of Usher on a dark and soundless day,” and finds a building which causes him a “sense of insufferable gloom,” which “pervades his spirit and causes an iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heart, an undiscerned dreariness of thought” (273). The narrator then optimistically states: “I reflected that a mere different arrangement of the scene, of the details of the picture, would be sufficient to modify, or perhaps annihilate its capacity for sorrowful impression” (274). But the narrator then sees the reflection of the house in the tarn and experiences a “shudder even more thrilling than before” (274). Thus the reader begins to realize that the narrator cannot change or stop the impending doom that will befall the house of Usher, and maybe humanity. The story cleverly plays with the word reflection : the narrator sees a physical reflection that leads him to a mental reflection about Usher’s surroundings.

The narrator’s disillusionment by such grim reflection continues in the story. For example, he describes Roderick Usher’s face as distinct with signs of old strength but lost vigor: the remains of what used to be. He describes the house as a once happy and vibrant place, which, like Roderick, lost its vitality. Also, the narrator describes Usher’s hair as growing wild on his rather obtrusive head, which directly mirrors the eerie moss and straw covering the outside of the house. The narrator continually longs to see these bleak reflections as a dream, for he states: “Shaking off from my spirit what must have been a dream, I scanned more narrowly the real aspect of the building” (276). He does not want to face the reality that Usher and his home are doomed to fall, regardless of what he does.

Although there are almost countless examples of these mirror images, two others stand out as important. First, Roderick and his sister, Madeline, are twins. The narrator aptly states just as he and Roderick are entombing Madeline that there is “a striking similitude between brother and sister” (288). Indeed, they are mirror images of each other. Madeline is fading away psychologically and physically, and Roderick is not too far behind! The reflection of “doom” that these two share helps intensify and symbolize the hopelessness of the entire situation; thus, they further develop the fatalistic theme. Second, in the climactic scene where Madeline has been mistakenly entombed alive, there is a pairing of images and sounds as the narrator tries to calm Roderick by reading him a romance story. Events in the story simultaneously unfold with events of the sister escaping her tomb. In the story, the hero breaks out of the coffin. Then, in the story, the dragon’s shriek as he is slain parallels Madeline’s shriek. Finally, the story tells of the clangor of a shield, matched by the sister’s clanging along a metal passageway. As the suspense reaches its climax, Roderick shrieks his last words to his “friend,” the narrator: “Madman! I tell you that she now stands without the door” (296).

Roderick, who slowly falls into insanity, ironically calls the narrator the “Madman.” We are left to reflect on what Poe means by this ironic twist. Poe’s bleak and dark imagery, and his use of mirror reflections, seem only to intensify the hopelessness of “Usher.” We can plausibly conclude that, indeed, the narrator is the “Madman,” for he comes from everyday society, which is a place where hope and faith exist. Poe would probably argue that such a place is opposite to the world of Usher because a world where death is inevitable could not possibly hold such positive values. Therefore, just as Roderick mirrors his sister, the reflection in the tarn mirrors the dilapidation of the house, and the story mirrors the final actions before the death of Usher. “The Fall of the House of Usher” reflects Poe’s view that humanity is hopelessly doomed.

Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Fall of the House of Usher.” 1839. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library . 1995. Web. 1 July 2012. < http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/PoeFall.html >.

Example 3: Poetry

Amy Chisnell

Professor Laura Neary

Writing and Literature

April 17, 20—

Don’t Listen to the Egg!: A Close Reading of Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky”

“You seem very clever at explaining words, Sir,” said Alice. “Would you kindly tell me the meaning of the poem called ‘Jabberwocky’?”

“Let’s hear it,” said Humpty Dumpty. “I can explain all the poems that ever were invented—and a good many that haven’t been invented just yet.” (Carroll 164)

In Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass , Humpty Dumpty confidently translates (to a not so confident Alice) the complicated language of the poem “Jabberwocky.” The words of the poem, though nonsense, aptly tell the story of the slaying of the Jabberwock. Upon finding “Jabberwocky” on a table in the looking-glass room, Alice is confused by the strange words. She is quite certain that “ somebody killed something ,” but she does not understand much more than that. When later she encounters Humpty Dumpty, she seizes the opportunity at having the knowledgeable egg interpret—or translate—the poem. Since Humpty Dumpty professes to be able to “make a word work” for him, he is quick to agree. Thus he acts like a New Critic who interprets the poem by performing a close reading of it. Through Humpty’s interpretation of the first stanza, however, we see the poem’s deeper comment concerning the practice of interpreting poetry and literature in general—that strict analytical translation destroys the beauty of a poem. In fact, Humpty Dumpty commits the “heresy of paraphrase,” for he fails to understand that meaning cannot be separated from the form or structure of the literary work.

Of the 71 words found in “Jabberwocky,” 43 have no known meaning. They are simply nonsense. Yet through this nonsensical language, the poem manages not only to tell a story but also gives the reader a sense of setting and characterization. One feels, rather than concretely knows, that the setting is dark, wooded, and frightening. The characters, such as the Jubjub bird, the Bandersnatch, and the doomed Jabberwock, also appear in the reader’s head, even though they will not be found in the local zoo. Even though most of the words are not real, the reader is able to understand what goes on because he or she is given free license to imagine what the words denote and connote. Simply, the poem’s nonsense words are the meaning.

Therefore, when Humpty interprets “Jabberwocky” for Alice, he is not doing her any favors, for he actually misreads the poem. Although the poem in its original is constructed from nonsense words, by the time Humpty is done interpreting it, it truly does not make any sense. The first stanza of the original poem is as follows:

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogroves,

An the mome raths outgrabe. (Carroll 164)

If we replace, however, the nonsense words of “Jabberwocky” with Humpty’s translated words, the effect would be something like this:

’Twas four o’clock in the afternoon, and the lithe and slimy badger-lizard-corkscrew creatures

Did go round and round and make holes in the grass-plot round the sun-dial:

All flimsy and miserable were the shabby-looking birds

with mop feathers,

And the lost green pigs bellowed-sneezed-whistled.

By translating the poem in such a way, Humpty removes the charm or essence—and the beauty, grace, and rhythm—from the poem. The poetry is sacrificed for meaning. Humpty Dumpty commits the heresy of paraphrase. As Cleanth Brooks argues, “The structure of a poem resembles that of a ballet or musical composition. It is a pattern of resolutions and balances and harmonizations” (203). When the poem is left as nonsense, the reader can easily imagine what a “slithy tove” might be, but when Humpty tells us what it is, he takes that imaginative license away from the reader. The beauty (if that is the proper word) of “Jabberwocky” is in not knowing what the words mean, and yet understanding. By translating the poem, Humpty takes that privilege from the reader. In addition, Humpty fails to recognize that meaning cannot be separated from the structure itself: the nonsense poem reflects this literally—it means “nothing” and achieves this meaning by using “nonsense” words.

Furthermore, the nonsense words Carroll chooses to use in “Jabberwocky” have a magical effect upon the reader; the shadowy sound of the words create the atmosphere, which may be described as a trance-like mood. When Alice first reads the poem, she says it seems to fill her head “with ideas.” The strange-sounding words in the original poem do give one ideas. Why is this? Even though the reader has never heard these words before, he or she is instantly aware of the murky, mysterious mood they set. In other words, diction operates not on the denotative level (the dictionary meaning) but on the connotative level (the emotion(s) they evoke). Thus “Jabberwocky” creates a shadowy mood, and the nonsense words are instrumental in creating this mood. Carroll could not have simply used any nonsense words.

For example, let us change the “dark,” “ominous” words of the first stanza to “lighter,” more “comic” words:

’Twas mearly, and the churly pells

Did bimble and ringle in the tink;

All timpy were the brimbledimps,

And the bip plips outlink.

Shifting the sounds of the words from dark to light merely takes a shift in thought. To create a specific mood using nonsense words, one must create new words from old words that convey the desired mood. In “Jabberwocky,” Carroll mixes “slimy,” a grim idea, “lithe,” a pliable image, to get a new adjective: “slithy” (a portmanteau word). In this translation, brighter words were used to get a lighter effect. “Mearly” is a combination of “morning” and “early,” and “ringle” is a blend of “ring” and "dingle.” The point is that “Jabberwocky’s” nonsense words are created specifically to convey this shadowy or mysterious mood and are integral to the “meaning.”

Consequently, Humpty’s rendering of the poem leaves the reader with a completely different feeling than does the original poem, which provided us with a sense of ethereal mystery, of a dark and foreign land with exotic creatures and fantastic settings. The mysteriousness is destroyed by Humpty’s literal paraphrase of the creatures and the setting; by doing so, he has taken the beauty away from the poem in his attempt to understand it. He has committed the heresy of paraphrase: “If we allow ourselves to be misled by it [this heresy], we distort the relation of the poem to its ‘truth’… we split the poem between its ‘form’ and its ‘content’” (Brooks 201). Humpty Dumpty’s ultimate demise might be seen to symbolize the heretical split between form and content: as a literary creation, Humpty Dumpty is an egg, a well-wrought urn of nonsense. His fall from the wall cracks him and separates the contents from the container, and not even all the King’s men can put the scrambled egg back together again!

Through the odd characters of a little girl and a foolish egg, “Jabberwocky” suggests a bit of sage advice about reading poetry, advice that the New Critics built their theories on. The importance lies not solely within strict analytical translation or interpretation, but in the overall effect of the imagery and word choice that evokes a meaning inseparable from those literary devices. As Archibald MacLeish so aptly writes: “A poem should not mean / But be.” Sometimes it takes a little nonsense to show us the sense in something.

Brooks, Cleanth. The Well-Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry . 1942. San Diego: Harcourt Brace, 1956. Print.

Carroll, Lewis. Through the Looking-Glass. Alice in Wonderland . 2nd ed. Ed. Donald J. Gray. New York: Norton, 1992. Print.

MacLeish, Archibald. “Ars Poetica.” The Oxford Book of American Poetry . Ed. David Lehman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006. 385–86. Print.

Attribution

- Sample Essay 1 received permission from Victoria Morillo to publish, licensed Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International ( CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 )

- Sample Essays 2 and 3 adapted from Cordell, Ryan and John Pennington. "2.5: Student Sample Papers" from Creating Literary Analysis. 2012. Licensed Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported ( CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 )

The Contemporary American Essay

This page is available to subscribers. Click here to sign in or get access .

TITLES CAN BE MISLEADING. In one sense, The Contemporary American Essay is perfectly chosen. It describes with commendable exactitude the nature of this volume. But though it pinpoints period, country, and genre, its matter-of-fact plainness belies the verve and color of the contents. What Phillip Lopate has so skilfully assembled is “a vast and variegated treasure.” That description is taken from another brilliant anthology, Lydia Fakundiny’s The Art of the Essay (1991). Fakundiny says that essays “make the language of the day” perform the essential task of “saying where we are in the moment of writing.” In so doing, she reckons that—over the centuries—this form of writing has done no less than amass “the memorabilia of individual responsiveness to all that is.” This is the treasure she talks about and that anthologists tap into. Even limiting himself to a fraction of it—just one nation’s essays, written between 2000 and the present—Lopate lays a rare trove of riches before readers.

There are forty-nine essays. To attempt to list—still less summarize—them would be inappropriate in a review. In any case, essays are resistant to summary. While academic articles submit to abstracts of their main points, essays, where the voice of the individual is paramount, are a different matter. Reading a book like this is not dissimilar to taking a long, invigorating walk that winds its way through a variety of fascinating terrains. Without attempting to condense its 600-plus pages into a paragraph, noting a few of the landmarks that particularly struck this reader should give some indication of the ground covered.

Lina Ferreira, in “CID-LAX-BOG,” talks about taking part in medical trials that involve being injected with the rabies virus—and through this unlikely lens gives considerable insight into issues of immigration, deportation, and belonging, in particular as these affect international students in America who wish to prolong their stay. Floyd Skloot, in “Gray Area: Thinking with a Damaged Brain,” touches on the nature of mind, brain, and consciousness. He considers how boxing inflicted serious brain injury on his childhood hero, Floyd Patterson. With considerable honesty, courage, and self-awareness, his essay shows how he’s come to terms with his own neurological impairment. Meghan O’Gieblyn’s “Homeschool” poses a whole catalog of questions about education, particularly the ideas behind homeschooling. Her presentation of Rousseau’s Émile as “the vade mecum of modern homeschooling” is particularly revealing—and it’s useful to be reminded that Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was written in part “as a critique of Rousseau’s pedagogy” rather than being simply the “parable about technological hubris” that it’s often presented as.

Aleksandar Hemon writes a heartbreaking account of a daughter’s death from a rare and virulent form of cancer, showing the power of words in a situation where they may seem powerless. Thomas Beller gives a luminously affectionate and atmospheric memoir about working in a bagel factory. Patricia Hampl’s “Other People’s Secrets” is an at times uncomfortable meditation on the ethics of writing. Joyce Carol Oates, in a rawly disturbing piece about imprisonment and execution, recounts her visit to San Quentin. Rebecca Solnit’s “Cassandra among the Creeps” deftly explores gender inequalities. There are also essays about disfigurement, revenge, race, vaccination, interior design, domestic abuse, and failure. And this is merely to skate over a fraction of what’s offered. Naturally, some essays appeal more than others. But all are finely written pieces. Lest the fluency of the writing make it seem easy, it’s good to have John McPhee’s “Draft No. 4,” a reminder of the sheer hard work involved in writing, and the many revisions that will have happened before each of these impressively polished essays emerged into publication.

In his short and moving “Invitation,” in which he reflects on what he learned from his years of traveling with Indigenous people, Barry Lopez suggests that “perhaps the first rule of everything we endeavor to do is to pay attention.” All of the pieces in The Contemporary American Essay are written by individuals who have followed that rule. Whatever their subject, no matter what stance they take, regardless of their background, or the cadence of the voice they elect to use, these essays are exercises in paying attention. Indeed, it’s almost as if Phillip Lopate used this first rule as his criterion for choosing what to include. It’s sad that Barry Lopez—surely one of the most accomplished nature essayists of our time—died before the book he contributed to appeared.

Unsurprisingly, given the quality of the writing that’s been assembled, the volume beautifully exemplifies many of the key features of the genre. In his influential book The Observing Self: Rediscovering the Essay , Graham Good argues that “anyone who can look attentively, think freely, and write clearly can be as essayist.” The forty-nine essays in Lopate’s selection are pleasingly varied—this is a richly diverse collection—but they all exhibit the attentive looking, freethinking, and clear writing that Good identifies as essential prerequisites. In another well-known characterization of the genre, Edward Hoagland says that essays “hang somewhere on a line between two sturdy poles: this is what I think, and this is what I am.” Again, these forty-nine essays could be arranged on precisely the line Hoagland identifies, some inclining more to one pole, some to the other, some almost dead center between them.

Many readers will be familiar with Phillip Lopate’s landmark 1994 anthology, The Art of the Personal Essay , which—deservedly—remains a key text. Putting it alongside his The Glorious American Essay: One Hundred Essays from Colonial Times to the Present (2020), The Golden Age of the American Essay, 1945–1970 (2021), and now The Contemporary American Essay makes for an impressive quartet. Each volume puts a treasury of first-rate writing before readers. Cumulatively, they constitute an important literary milestone, celebrating—demonstrating—the history, development, and present vigor of this mercurial genre. They also suggest a topic for a future essay: “On the Art of the Anthologist.” It is an art in which Phillip Lopate clearly excels.

Chris Arthur St. Andrews, Scotland

More Reviews

Here Is a Body Basma Abdel Aziz. Trans. Jonathan Wright

Testamint fan de siel Hylke Speerstra

The Morning Star Karl Ove Knausgaard. Trans. Martin Aitken

The Books of Jacob: A Novel Olga Tokarczuk. Trans. Jennifer Croft

Homecoming Trails in Mexican American Cultural History: Biography, Nationhood, and Globalism Ed. Roberto Cantú

Dendrarium Alexander Shurbanov. Trans. Valentina Meloni & Francesco Tomada

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity David Graeber & David Wengrow

How Literatures Begin: A Global History Ed. Joel B. Lande & Denis Feeney

Three Novels Yuri Herrera. Trans. Lisa Dillman

L.A. Weather María Amparo Escandón

Whisper Chang Yu-Ko. Trans. Roddy Flagg

14 International Younger Poets Ed. Philip Nikolayev

Purple Perilla Can Xue. Trans. Karen Gernant & Chen Zeping

Ancestral Demon of a Grieving Bride Sy Hoahwah

Chasing Homer László Krasznahorkai. Trans. John Batki

De quoi aimer vivre Fatou Diome

Heard-Hoard Atsuro Riley.

The Contemporary American Essay Ed. Phillip Lopate

Notes on Grief Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

The Prairie Chicken Dance Tour Dawn Dumont

The Best Asian Short Stories 2020 Ed. Zafar Anjum

E-newsletter, join the mailing list.

January 2022

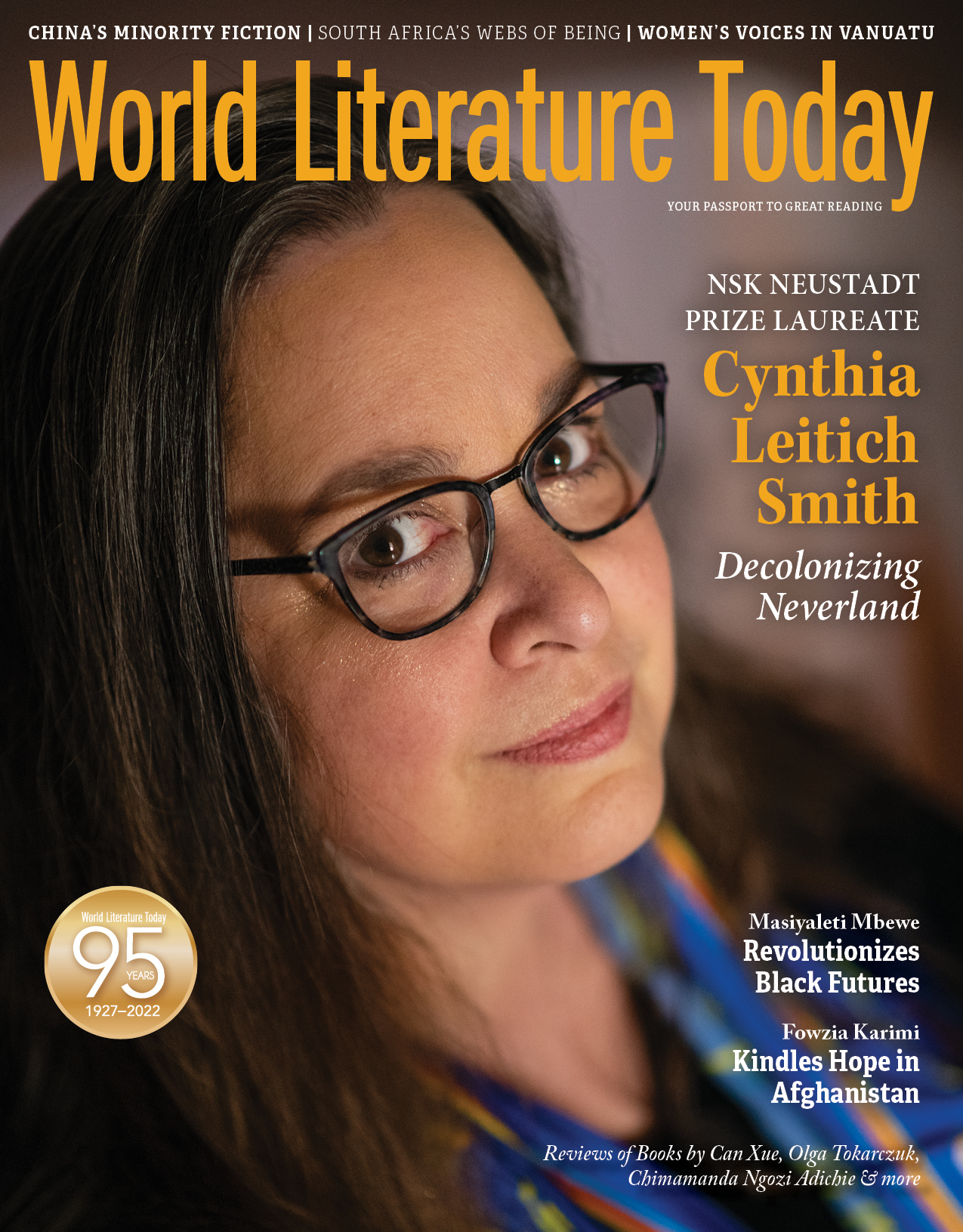

Muscogee writer Cynthia Leitich Smith , winner of the 2021 NSK Neustadt Prize for Children’s & Young Adult Literature, headlines the January 2022 issue with a reflective essay on “Decolonizing Neverland” in YA lit. Also inside, essays, poetry, fiction, and interview, as well as more than twenty book reviews—plus recommended reads and other great content—make the latest issue of WLT , like every issue, your passport to great reading.

Purchase this Issue »

Table of Contents

In every issue, creative nonfiction, the nsk neustadt prize: cynthia leitich smith, book reviews.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Studying Literature

How to Write a Conclusion to a Literary Essay

Last Updated: July 3, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Stephanie Wong Ken, MFA . Stephanie Wong Ken is a writer based in Canada. Stephanie's writing has appeared in Joyland, Catapult, Pithead Chapel, Cosmonaut's Avenue, and other publications. She holds an MFA in Fiction and Creative Writing from Portland State University. There are 9 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 78,253 times.

A literary essay should analyze and evaluate a work of literature or an aspect of a work of literature. You may be required to write a literary essay for Language Arts class or as an assignment for an English Literature course. After a lot of hard work, you may have the majority of your literary essay done and be stuck on the conclusion. A strong conclusion will restate the thesis statement and broaden the scope of the essay in four to six sentences. You should also have an effective last sentence in the essay so you can wrap it up on a high note.

Reworking Your Thesis Statement

- For example, maybe your original thesis statement was, “Though there are elements of tragedy in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream , the structure, themes, and staging of the play fall into the genre of comedy.”

- You may then rephrase your thesis statement by shifting around some of the language in the original and by using a more precise word choice. For example, the rephrased thesis statement may be, “While there are tragic moments in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream , the structure, themes, and staging of the play fit within the genre of comedy.”

- You may then revise it to better reflect your essay as a whole, “While tragic events do occur in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream , the three-act structure, the themes of magic and dreams, as well as the farcical staging of the play indicate that it fits in the genre of comedy.”

- Keep in mind if you make major revisions to your thesis statement, it should only be done to reflect the rest of your essay as a whole. Make sure the original thesis statement in your introduction still compliments or reflects the revised thesis statement in your conclusion.

- You do not need to put “In conclusion,” “In summary,” or “To conclude” before your thesis statement to start the conclusion. This can feel too formal and stilted. Instead, start a new paragraph and launch right into your rephrased thesis statement at the beginning of the conclusion.

Writing the Middle Section of the Conclusion

- For example, you may have a sentence about how the staging of the play affects the genre of the play in your introduction. You could then rephrase this sentence and include it in your conclusion.

- If you read over your introduction and realize some of your ideas have shifted in your body paragraphs, you may need to revise your introduction and use the revisions to then write the middle section of the conclusion.

- For example, maybe you focus on the theme of magic in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the body section of your essay. You can then reiterate the theme of magic by using an image from the play that illustrates the magical element of the text.

- For example, if your essay focuses on how the theme of love in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream , you may include a quote from the text that illustrates this theme.

- For example, if you are writing an essay about Harper Lee's To Kill A Mockingbird , you may answer the question “so what?” by thinking about how and why Harper Lee's novel discusses issues of race and identity in the South. You could then use your response in the conclusion of the essay.

- For example, you may summarize your essay by noting, "An analysis of scenes between white characters and African-American characters in the novel, as done in this essay, make it clear that Lee is addressing questions of race and identity in the South head-on."

Wrapping Up the Conclusion

- For example, if the focus of your essay is the theme of magic in the text, you may end with an image for the text that includes a magical element that is important to the main character.