- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Brown v. Board of Education

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 27, 2024 | Original: October 27, 2009

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was a landmark 1954 Supreme Court case in which the justices ruled unanimously that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional. Brown v. Board of Education was one of the cornerstones of the civil rights movement, and helped establish the precedent that “separate-but-equal” education and other services were not, in fact, equal at all.

Separate But Equal Doctrine

In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that racially segregated public facilities were legal, so long as the facilities for Black people and whites were equal.

The ruling constitutionally sanctioned laws barring African Americans from sharing the same buses, schools and other public facilities as whites—known as “Jim Crow” laws —and established the “separate but equal” doctrine that would stand for the next six decades.

But by the early 1950s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ( NAACP ) was working hard to challenge segregation laws in public schools, and had filed lawsuits on behalf of plaintiffs in states such as South Carolina, Virginia and Delaware.

In the case that would become most famous, a plaintiff named Oliver Brown filed a class-action suit against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, in 1951, after his daughter, Linda Brown , was denied entrance to Topeka’s all-white elementary schools.

In his lawsuit, Brown claimed that schools for Black children were not equal to the white schools, and that segregation violated the so-called “equal protection clause” of the 14th Amendment , which holds that no state can “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The case went before the U.S. District Court in Kansas, which agreed that public school segregation had a “detrimental effect upon the colored children” and contributed to “a sense of inferiority,” but still upheld the “separate but equal” doctrine.

Brown v. Board of Education Verdict

When Brown’s case and four other cases related to school segregation first came before the Supreme Court in 1952, the Court combined them into a single case under the name Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka .

Thurgood Marshall , the head of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, served as chief attorney for the plaintiffs. (Thirteen years later, President Lyndon B. Johnson would appoint Marshall as the first Black Supreme Court justice.)

At first, the justices were divided on how to rule on school segregation, with Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson holding the opinion that the Plessy verdict should stand. But in September 1953, before Brown v. Board of Education was to be heard, Vinson died, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower replaced him with Earl Warren , then governor of California .

Displaying considerable political skill and determination, the new chief justice succeeded in engineering a unanimous verdict against school segregation the following year.

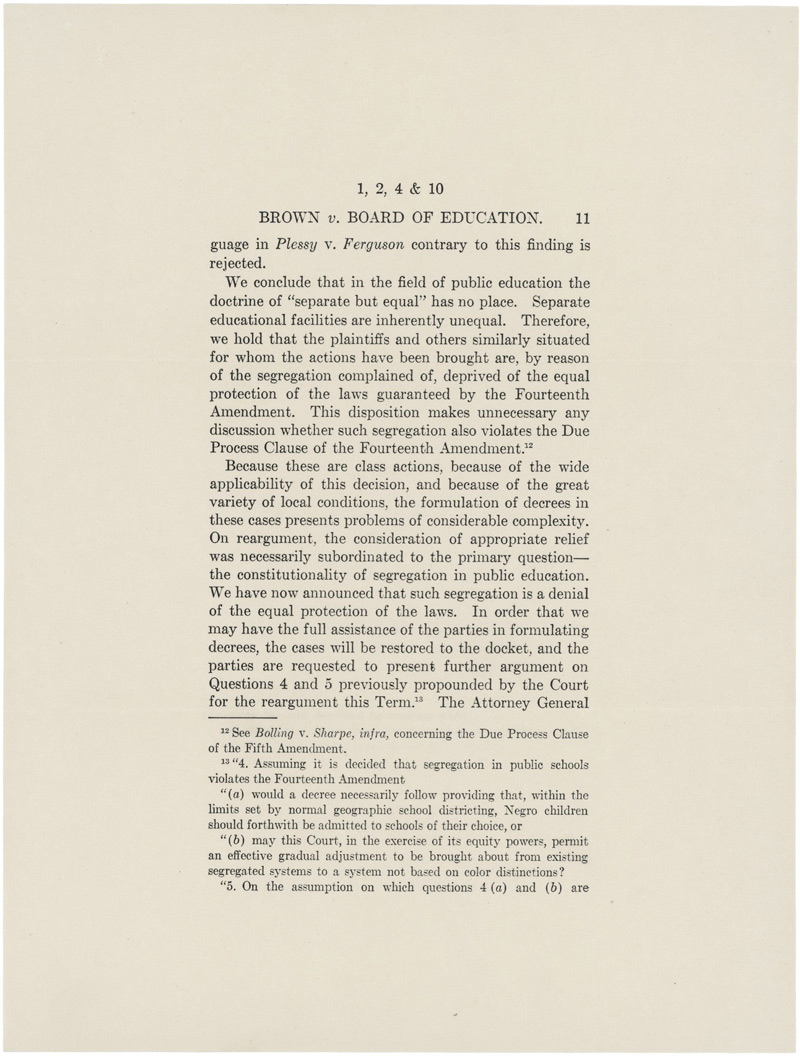

In the decision, issued on May 17, 1954, Warren wrote that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place,” as segregated schools are “inherently unequal.” As a result, the Court ruled that the plaintiffs were being “deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.”

Little Rock Nine

In its verdict, the Supreme Court did not specify how exactly schools should be integrated, but asked for further arguments about it.

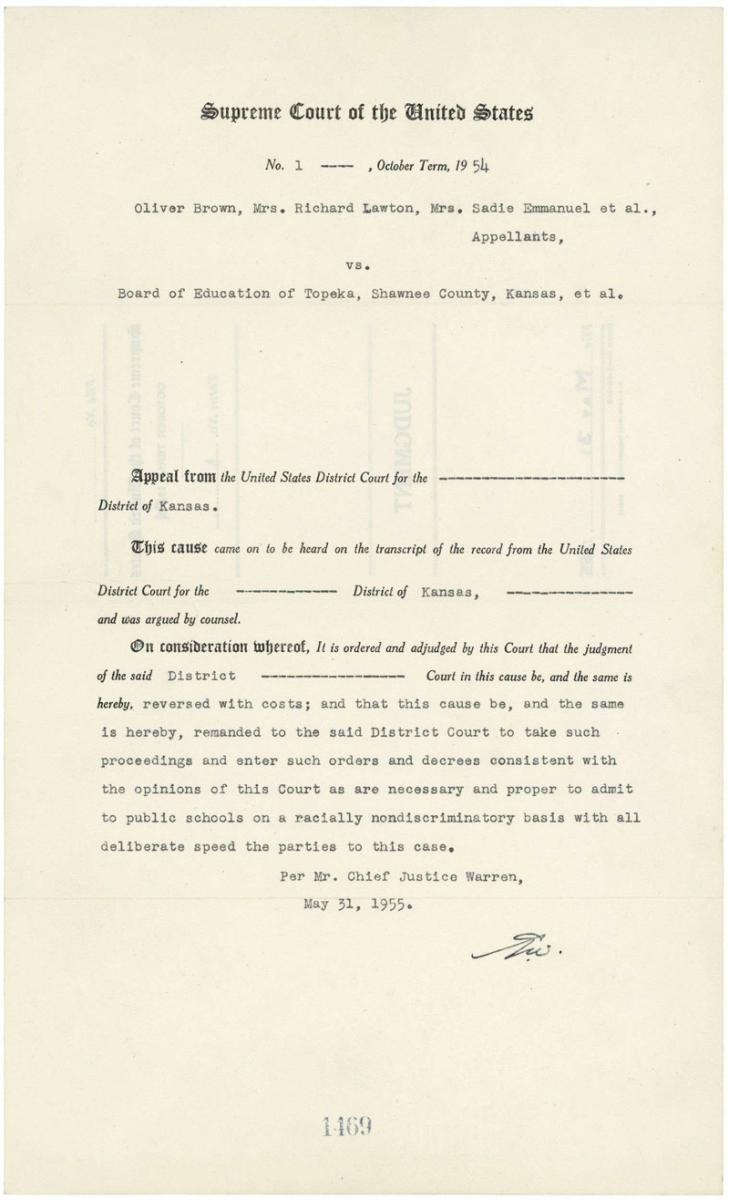

In May 1955, the Court issued a second opinion in the case (known as Brown v. Board of Education II ), which remanded future desegregation cases to lower federal courts and directed district courts and school boards to proceed with desegregation “with all deliberate speed.”

Though well intentioned, the Court’s actions effectively opened the door to local judicial and political evasion of desegregation. While Kansas and some other states acted in accordance with the verdict, many school and local officials in the South defied it.

In one major example, Governor Orval Faubus of Arkansas called out the state National Guard to prevent Black students from attending high school in Little Rock in 1957. After a tense standoff, President Eisenhower deployed federal troops, and nine students—known as the “ Little Rock Nine ”— were able to enter Central High School under armed guard.

Impact of Brown v. Board of Education

Though the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board didn’t achieve school desegregation on its own, the ruling (and the steadfast resistance to it across the South) fueled the nascent civil rights movement in the United States.

In 1955, a year after the Brown v. Board of Education decision, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus. Her arrest sparked the Montgomery bus boycott and would lead to other boycotts, sit-ins and demonstrations (many of them led by Martin Luther King Jr .), in a movement that would eventually lead to the toppling of Jim Crow laws across the South.

Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 , backed by enforcement by the Justice Department, began the process of desegregation in earnest. This landmark piece of civil rights legislation was followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 .

Runyon v. McCrary Extends Policy to Private Schools

In 1976, the Supreme Court issued another landmark decision in Runyon v. McCrary , ruling that even private, nonsectarian schools that denied admission to students on the basis of race violated federal civil rights laws.

By overturning the “separate but equal” doctrine, the Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education had set the legal precedent that would be used to overturn laws enforcing segregation in other public facilities. But despite its undoubted impact, the historic verdict fell short of achieving its primary mission of integrating the nation’s public schools.

Today, more than 60 years after Brown v. Board of Education , the debate continues over how to combat racial inequalities in the nation’s school system, largely based on residential patterns and differences in resources between schools in wealthier and economically disadvantaged districts across the country.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

History – Brown v. Board of Education Re-enactment, United States Courts . Brown v. Board of Education, The Civil Rights Movement: Volume I (Salem Press). Cass Sunstein, “Did Brown Matter?” The New Yorker , May 3, 2004. Brown v. Board of Education, PBS.org . Richard Rothstein, Brown v. Board at 60, Economic Policy Institute , April 17, 2014.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Legal Dictionary

The Law Dictionary for Everyone

Brown v. Board of Education

Following is the case brief for Brown v. Board of Education, United States Supreme Court, (1954)

Case Summary of Brown v. Board of Education:

- Oliver Brown was denied admission into a white school

- As a representative of a class action suit, Brown filed a claim alleging that laws permitting segregation in public schools were a violation of the 14 th Amendment equal protection clause .

- After the District Court upheld segregation using Plessy v. Ferguson as authority, Brown petitioned the United States Supreme Court.

- The Supreme Court held that segregation had a profound and detrimental effect on education and segregation deprived minority children of equal protection under the law.

Brown v. Board of Education Case Brief

Statement of Facts:

Oliver Brown and other plaintiffs were denied admission into a public school attended by white children. This was permitted under laws which allowed segregation based on race. Brown claimed that the segregation deprived minority children of equal protection under the 14 th Amendment. Brown filed a class action, consolidating cases from Virginia, South Carolina, Delaware and Kansas against the Board of Education in a federal district court in Kansas.

Procedural History:

Brown filed suit against the Board of Education in District Court. After the District Court held in favor of the Board, Brown appealed to the United States Supreme Court. The Supreme Court granted certiorari.

Issues and Holding:

Does the segregation on the basis of race in public schools deprive minority children of equal educational opportunities, violating the 14 th Amendment? Yes.

The Court Reversed the District Court’s decision.

Rule of Law or Legal Principle Applied:

Separating educational facilities based on racial classifications is unequal in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14 th Amendment.

The Court held that looking to historical legislation and prior cases could not yield a true meaning of the 14 th Amendment because each is inconclusive.

At the time the 14 th Amendment was enacted, almost no African American children were receiving an education. As such, trying to determine the historical intentions surrounding the 14 th Amendment is not helpful. In addition, few public schools existed at the time the amendment was adopted.

Analyzing the text of the amendment itself is necessary to determine its true meaning. The Court held the basic language of the Amendment suggests the intent to prohibit all discriminatory legislation against minorities.

Despite the fact each facility is essentially the same, the Court held it was necessary to examine the actual effect of segregation on education. Over the past few years, public education has turned into one of the most valuable public services both state and local governments have to offer. Since education has a heavy bearing on the future success of each child, the opportunity to be educated must be equal to each student.

The Court stated that the opportunity for education available to segregated minorities has a profound and detrimental effect on both their hearts and minds. Studies showed that segregated students felt less motivated, inferior and have a lower standard of performance than non-minority students. The Court explicitly overturned Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 U.S. 537 (1896), stating that segregation deprives African-American students of equal protection under the 14 th Amendment.

Concurring/ Dissenting opinion :

Unanimous decision led by Justice Warren.

Significance:

Brown v. Board of Education was the landmark case which desegregated public schools in the United States. It abolished the idea of “ separate but equal .”

Student Resources:

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/rights/landmark_brown.html https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/347/483

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 8

- Introduction to the Civil Rights Movement

- African American veterans and the Civil Rights Movement

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

- Emmett Till

- The Montgomery Bus Boycott

- "Massive Resistance" and the Little Rock Nine

- The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

- SNCC and CORE

- Black Power

- The Civil Rights Movement

- In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) a unanimous Supreme Court declared that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.

- The Court declared “separate” educational facilities “inherently unequal.”

- The case electrified the nation, and remains a landmark in legal history and a milestone in civil rights history.

A segregated society

The brown v. board of education case, thurgood marshall, the naacp, and the supreme court, separate is "inherently unequal", brown ii: desegregating with "all deliberate speed”, what do you think.

- James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 387.

- James T. Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 25-27.

- Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, 387.

- Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, 32.

- See Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, and Richard Kluger, Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality (New York: Knopf, 2004).

- Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, 43-45.

- Supreme Court of the United States, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

- Patterson, Grand Expectations, 394-395.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

You are using an outdated browser no longer supported by Oyez. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- Find a Lawyer

- Ask a Lawyer

- Research the Law

- Law Schools

- Laws & Regs

- Newsletters

- Justia Connect

- Pro Membership

- Basic Membership

- Justia Lawyer Directory

- Platinum Placements

- Gold Placements

- Justia Elevate

- Justia Amplify

- PPC Management

- Google Business Profile

- Social Media

- Justia Onward Blog

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits states from segregating public school students on the basis of race. This marked a reversal of the "separate but equal" doctrine from Plessy v. Ferguson that had permitted separate schools for white and colored children provided that the facilities were equal.

Based on an 1879 law, the Board of Education in Topeka, Kansas operated separate elementary schools for white and African-American students in communities with more than 15,000 residents. The NAACP in Topeka sought to challenge this policy of segregation and recruited 13 Topeka parents to challenge the law on behalf of 20 children. In 1951, each of the families attempted to enroll the children in the school closest to them, which were schools designated for whites. Each child was refused admission and directed to the African-American schools, which were much further from where they lived. For example, Linda Brown, the daughter of the named plaintiff, could have attended a white school several blocks from her house but instead was required to walk some distance to a bus stop and then take the bus for a mile to an African-American school. Once the children had been refused admission to the schools designated for whites, the NAACP brought the lawsuit. They were unsuccessful at the trial court level, where the 1896 Supreme Court precedent in Plessy v. Ferguson was found to be decisive. Even though the trial court agreed that educational segregation had a negative effect on African-American children, it applied the standard of Plessy in finding that the white and African-American schools offered sufficiently equal quality of teachers, curricula, facilities, and transportation. Since the NAACP did not challenge the details of those findings, it essentially cast the appeal as a direct challenge to the system imposed by Plessy. When the Supreme Court heard the appeal, it combined Brown with four other cases addressing parallel issues in South Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, and Washington, D.C. The NAACP was responsible for bringing each of these lawsuits, and it had lost on each of them at the trial court level except the Delaware case of Gebhart v. Belton. Brown stood apart from the others in the group as the only case that challenged the separate but equal doctrine on its face. The others were based on assertions of gross inequality, which would have violated the standard in Plessy as well.

- Earl Warren (Author)

- Hugo Lafayette Black

- Stanley Forman Reed

- Felix Frankfurter

- William Orville Douglas

- Robert Houghwout Jackson

- Harold Hitz Burton

- Tom C. Clark

- Sherman Minton

Supreme Court opinions are rarely unanimous, and it appears that Justice Frankfurter deliberately argued for a re-hearing to stall the case while the Court built a consensus behind its decision. This was designed to prevent proponents of segregation from using dissents to build future challenges to Brown. Despite the eventual unanimity, the judges had a wide range of views. Reed and Clark were not opposed to segregation per se, while Frankfurter and Jackson were hesitant to issue a bold decision that might be difficult to enforce. (Jackson and Reed initially planned to write a dissent together.) Douglas, Black, Burton, and Minton were relatively ready to overturn Plessy from the outset, however, as was Chief Justice Warren. President Dwight D. Eisenhower's appointment of Warren to replace former Chief Justice Frederick Moore Vinson, who died in September 1953, thus may have played a crucial role in how events unfolded. Warren had supported the integration of Mexican-American children into California schools. Warren based much of his opinion on information from social science studies rather than court precedent. This was understandable because few decisions existed on which the Court could rely, yet it would draw criticism for its non-traditional approach. The decision also used language that was relatively accessible to non-lawyers because Warren felt that it was necessary for all Americans to understand its logic.

This decision ranks among the most dramatic issued by the Supreme Court, in part due to Warren's insistence that the Fourteenth Amendment gave the Court the power to end segregation even without Congressional authority. Like the use of non-legal sources to justify his reasoning, Warren's "activist" view of the Court's role remains controversial to the current day. The illegality of segregation does not, however, and a series of later decisions were implemented to try to force states to comply with Brown. Unfortunately, the reality is that this decision's vision of complete desegregation has not been achieved in many areas of the U.S., and the problems of enforcement that Jackson identified have proven difficult to solve.

U.S. Supreme Court

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Argued December 9, 1952

Reargued December 8, 1953

Decided May 17, 1954*

Segregation of white and Negro children in the public schools of a State solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such segregation, denies to Negro children the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment -- even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors of white and Negro schools may be equal. Pp. 486-496.

(a) The history of the Fourteenth Amendment is inconclusive as to its intended effect on public education. Pp. 489-490.

(b) The question presented in these cases must be determined not on the basis of conditions existing when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, but in the light of the full development of public education and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Pp. 492-493.

(c) Where a State has undertaken to provide an opportunity for an education in its public schools, such an opportunity is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms. P. 493.

(d) Segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race deprives children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal. Pp. 493-494.

(e) The "separate but equal" doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 , has no place in the field of public education. P. 495.

(f) The cases are restored to the docket for further argument on specified questions relating to the forms of the decrees. Pp. 495-496.

- Opinions & Dissents

- Copy Citation

Get free summaries of new US Supreme Court opinions delivered to your inbox!

- Bankruptcy Lawyers

- Business Lawyers

- Criminal Lawyers

- Employment Lawyers

- Estate Planning Lawyers

- Family Lawyers

- Personal Injury Lawyers

- Estate Planning

- Personal Injury

- Business Formation

- Business Operations

- Intellectual Property

- International Trade

- Real Estate

- Financial Aid

- Course Outlines

- Law Journals

- US Constitution

- Regulations

- Supreme Court

- Circuit Courts

- District Courts

- Dockets & Filings

- State Constitutions

- State Codes

- State Case Law

- Legal Blogs

- Business Forms

- Product Recalls

- Justia Connect Membership

- Justia Premium Placements

- Justia Elevate (SEO, Websites)

- Justia Amplify (PPC, GBP)

- Testimonials

Some case metadata and case summaries were written with the help of AI, which can produce inaccuracies. You should read the full case before relying on it for legal research purposes.

Educator Resources

Brown v. Board of Education

The Supreme Court's opinion in the Brown v. Board of Education case of 1954 legally ended decades of racial segregation in America's public schools. Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case. State-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th Amendment and was therefore unconstitutional. This historic decision marked the end of the "separate but equal" precedent set by the Supreme Court nearly 60 years earlier and served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement. Read more...

Primary Sources

Links go to DocsTeach , the online tool for teaching with documents from the National Archives.

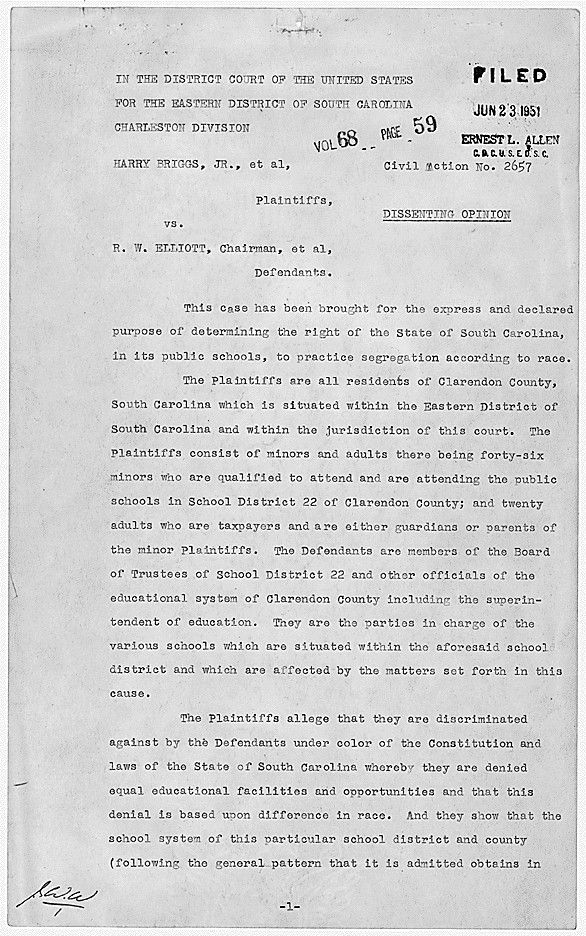

Dissenting opinion in Briggs v. Elliott in which Judge Waties Waring opposed the District Court ruling that "separate but equal" schools were not in violation of the 14th amendment – he presented arguments that would later be used by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas , 6/21/1951

View in National Archives Catalog

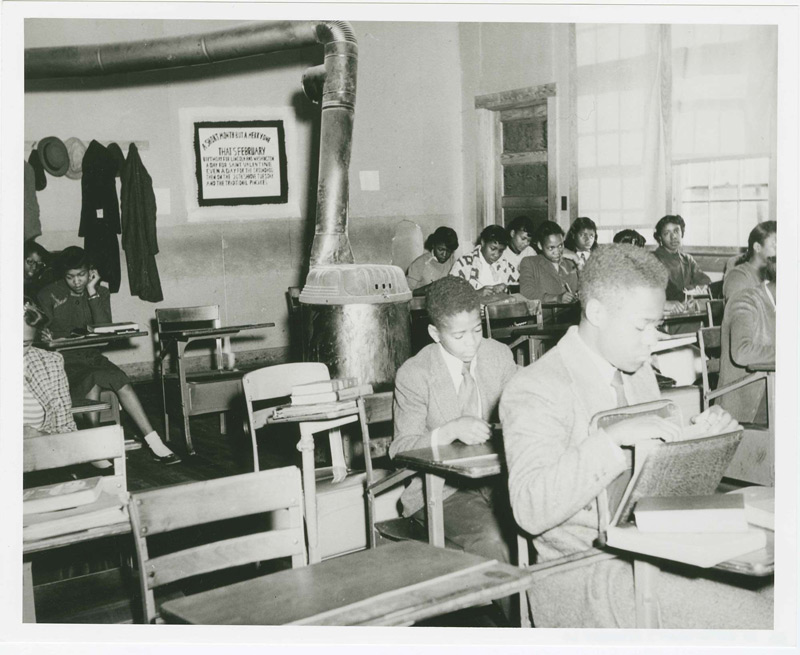

English class at Moton High School , a school for Black students, one of several photographs entered as evidence in the case Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia , which was one of five cases that the Supreme Court consolidated under Brown v. Board of Education , ca. 1951

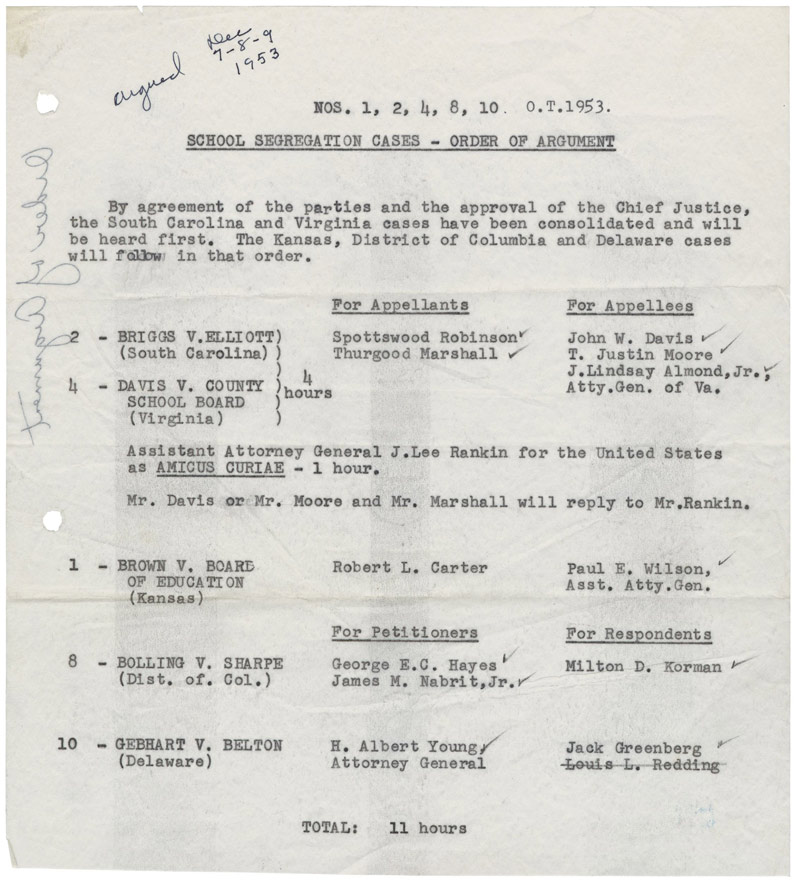

Order of Argument in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka during which attorneys reargued the five cases that the Supreme Court heard collectively and consolidated under the name Brown v. Board of Education , 12/1953

Page 11 of the unanimous Supreme Court ruling of 5/17/1954 in Brown v. Board of Education that state-sanctioned segregation of public schools violated the 14th Amendment, marking the end of the "separate but equal" precedent

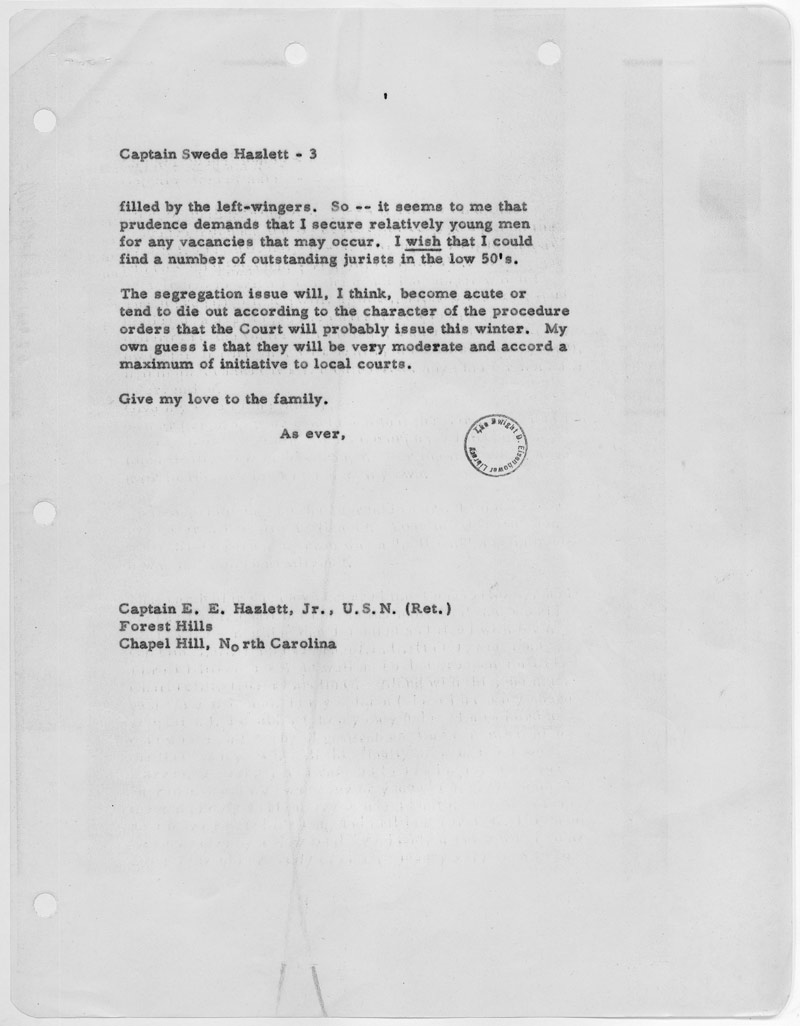

Page 3 of a letter from President Eisenhower to E. E. "Swede" Hazlett in which the President expressed his belief that the new Warren court would be very moderate on the issue of segregation, 10/23/1954

Judgment of May 31, 1955, in Brown v. Board of Education (Brown II) – a year after the ruling that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional – directing that schools be desegregated "with all deliberate speed"

- Brown v. Board of Education Timeline

- Biographies of Key Figures

- Related Primary Sources: Photographs from the Dorothy Davis Case

Teaching Activities

The "Rights in America" page on DocsTeach includes primary sources and document-based teaching activities related to how individuals and groups have asserted their rights as Americans. It includes topics such as segregation, racism, citizenship, women's independence, immigration, and more.

Additional Background Information

While the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution outlawed slavery, it wasn't until three years later, in 1868, that the 14th Amendment guaranteed the rights of citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, including due process and equal protection of the laws. These two amendments, as well as the 15th Amendment protecting voting rights, were intended to eliminate the last remnants of slavery and to protect the citizenship of Black Americans.

In 1875, Congress also passed the first Civil Rights Act, which held the "equality of all men before the law" and called for fines and penalties for anyone found denying patronage of public places, such as theaters and inns, on the basis of race. However, a reactionary Supreme Court reasoned that this act was beyond the scope of the 13th and 14th Amendments, as these amendments only concerned the actions of the government, not those of private citizens. With this ruling, the Supreme Court narrowed the field of legislation that could be supported by the Constitution and at the same time turned the tide against the civil rights movement.

By the late 1800s, segregation laws became almost universal in the South where previous legislation and amendments were, for all practical purposes, ignored. The races were separated in schools, in restaurants, in restrooms, on public transportation, and even in voting and holding office.

Plessy v. Ferguson

In 1896, the Supreme Court upheld the lower courts' decision in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson . Homer Plessy, a Black man from Louisiana, challenged the constitutionality of segregated railroad coaches, first in the state courts and then in the U. S. Supreme Court.

The high court upheld the lower courts, noting that since the separate cars provided equal services, the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment was not violated. Thus, the "separate but equal" doctrine became the constitutional basis for segregation. One dissenter on the Court, Justice John Marshall Harlan, declared the Constitution "color blind" and accurately predicted that this decision would become as baneful as the infamous Dred Scott decision of 1857.

In 1909 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was officially formed to champion the modern Civil Rights Movement. In its early years its primary goals were to eliminate lynching and to obtain fair trials for Black Americans. By the 1930s, however, the activities of the NAACP began focusing on the complete integration of American society. One of their strategies was to force admission of Black Americans into universities at the graduate level where establishing separate but equal facilities would be difficult and expensive for the states.

At the forefront of this movement was Thurgood Marshall, a young Black lawyer who, in 1938, became general counsel for the NAACP's Legal Defense and Education Fund. Significant victories at this level included Gaines v. University of Missouri in 1938, Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma in 1948, and Sweatt v. Painter in 1950. In each of these cases, the goal of the NAACP defense team was to attack the "equal" standard so that the "separate" standard would in turn become susceptible.

Five Cases Consolidated under Brown v. Board of Education

By the 1950s, the NAACP was beginning to support challenges to segregation at the elementary school level. Five separate cases were filed in Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, the District of Columbia, and Delaware:

- Oliver Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas, et al.

- Harry Briggs, Jr., et al. v. R.W. Elliott, et al.

- Dorothy E. Davis et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al.

- Spottswood Thomas Bolling et al. v. C. Melvin Sharpe et al.

- Francis B. Gebhart et al. v. Ethel Louise Belton et al.

While each case had its unique elements, all were brought on the behalf of elementary school children, and all involved Black schools that were inferior to white schools. Most importantly, rather than just challenging the inferiority of the separate schools, each case claimed that the "separate but equal" ruling violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

The lower courts ruled against the plaintiffs in each case, noting the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling of the United States Supreme Court as precedent. In the case of Brown v. Board of Education , the Federal district court even cited the injurious effects of segregation on Black children, but held that "separate but equal" was still not a violation of the Constitution. It was clear to those involved that the only effective route to terminating segregation in public schools was going to be through the United States Supreme Court.

In 1952 the Supreme Court agreed to hear all five cases collectively. This grouping was significant because it represented school segregation as a national issue, not just a southern one. Thurgood Marshall, one of the lead attorneys for the plaintiffs (he argued the Briggs case), and his fellow lawyers provided testimony from more than 30 social scientists affirming the deleterious effects of segregation on Black and white children. These arguments were similar to those alluded to in the Dissenting Opinion of Judge Waites Waring in Harry Briggs, Jr., et al. v. R. W. Elliott, Chairman, et al . (shown above).

These [social scientists] testified as to their study and researches and their actual tests with children of varying ages and they showed that the humiliation and disgrace of being set aside and segregated as unfit to associate with others of different color had an evil and ineradicable effect upon the mental processes of our young which would remain with them and deform their view on life until and throughout their maturity....They showed beyond a doubt that the evils of segregation and color prejudice come from early training...it is difficult and nearly impossible to change and eradicate these early prejudices however strong may be the appeal to reason…if segregation is wrong then the place to stop it is in the first grade and not in graduate colleges.

The lawyers for the school boards based their defense primarily on precedent, such as the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling, as well as on the importance of states' rights in matters relating to education.

Realizing the significance of their decision and being divided among themselves, the Supreme Court took until June 1953 to decide they would rehear arguments for all five cases.

The arguments were scheduled for the following term. The Court wanted briefs from both sides that would answer five questions, all having to do with the attorneys' opinions on whether or not Congress had segregation in public schools in mind when the 14th amendment was ratified.

The Order of Argument (shown above) offers a window into the three days in December of 1953 during which the attorneys reargued the cases. The document lists the names of each case, the states from which they came, the order in which the Court heard them, the names of the attorneys for the appellants and appellees, the total time allotted for arguments, and the dates over which the arguments took place.

Briggs v. Elliott

The first case listed, Briggs v. Elliott , originated in Clarendon County, South Carolina, in the fall of 1950. Harry Briggs was one of 20 plaintiffs who were charging that R.W. Elliott, as president of the Clarendon County School Board, violated their right to equal protection under the fourteenth amendment by upholding the county's segregated education law. Briggs featured social science testimony on behalf of the plaintiffs from some of the nation's leading child psychologists, such as Dr. Kenneth Clark, whose famous doll study concluded that segregation negatively affected the self-esteem and psyche of African-American children. Such testimony was groundbreaking because on only one other occasion in U.S. history had a plaintiff attempted to present such evidence before the Court.

Thurgood Marshall, the noted NAACP attorney and future Supreme Court Justice, argued the Briggs case at the District and Federal Court levels. The U.S. District Court's three-judge panel ruled against the plaintiffs, with one judge dissenting, stating that "separate but equal" schools were not in violation of the 14th amendment. In his dissenting opinion (shown above), Judge Waties Waring presented some of the arguments that would later be used by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas . The case was appealed to the Supreme Court.

Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia

Marshall also argued the Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, case at the Federal level. Originally filed in May of 1951 by plaintiff's attorneys Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill, the Davis case, like the others, argued that Virginia's segregated schools were unconstitutional because they violated the equal protection clause of the fourteenth amendment. And like the Briggs case, Virginia's three-judge panel ruled against the 117 students who were identified as plaintiffs in the case. (For more on this case, see Photographs from the Dorothy Davis Case .)

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Listed third in the order of arguments, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was initially filed in February of 1951 by three Topeka area lawyers, assisted by the NAACP's Robert Carter and Jack Greenberg. As in the Briggs case, this case featured social science testimony on behalf of the plaintiffs that segregation had a harmful effect on the psychology of African-American children. While that testimony did not prevent the Topeka judges from ruling against the plaintiffs, the evidence from this case eventually found its way into the wording of the Supreme Court's May 17, 1954 opinion. The Court concluded that:

To separate them [children in grade and high schools] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely to ever be undone.

Bolling v. Sharpe

Because Washington, D.C., is a Federal territory governed by Congress and not a state, the Bolling v. Sharpe case was argued as a fifth amendment violation of "due process." The fourteenth amendment only mentions states, so this case could not be argued as a violation of "equal protection," as were the other cases. When a District of Columbia parent, Gardner Bishop, unsuccessfully attempted to get 11 African-American students admitted into a newly constructed white junior high school, he and the Consolidated Parents Group filed suit against C. Melvin Sharpe, president of the Board of Education of the District of Columbia. Charles Hamilton Houston, the NAACP's special counsel, former dean of the Howard University School of Law, and mentor to Thurgood Marshall, took up the Bolling case.

With Houston's health already failing in 1950 when he filed suit, James Nabrit, Jr. replaced Houston as the original attorney. By the time the case reached the Supreme Court on appeal, George E.C. Hayes had been added as an attorney for the petitioners, beside James Nabrit, Jr. According to the Court, due to the decision in Plessy , "the plaintiffs and others similarly situated" had been "deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment," therefore, segregation of America's public schools was unconstitutional.

Belton v. Gebhart

The last case listed in the order of arguments, Belton v. Gebhart , was actually two nearly identical cases (the other being Bulah v. Gebhart ), both originating in the state of Delaware in 1952. Ethel Belton was one of the parents listed as plaintiffs in the case brought in Claymont, while Sarah Bulah brought suit in the town of Hockessin, Delaware. While both of these plaintiffs brought suit because their African-American children had to attend inferior schools, Sarah Bulah's situation was unique in that she was a white woman with an adopted Black child, who was still subject to the segregation laws of the state. Local attorney Louis Redding, Delaware's only African-American attorney at the time, originally argued both cases in Delaware's Court of Chancery. NAACP attorney Jack Greenberg assisted Redding. Belton/Bulah v. Gebhart was argued at the Federal level by Delaware's attorney general, H. Albert Young.

Supreme Court Rehears Arguments

Reargument of the Brown v. Board of Education cases at the Federal level took place December 7-9, 1953. Throngs of spectators lined up outside the Supreme Court by sunrise on the morning of December 7, although arguments did not actually commence until one o'clock that afternoon. Spottswood Robinson began the argument for the appellants, and Thurgood Marshall followed him. Virginia's Assistant Attorney General, T. Justin Moore, followed Marshall, and then the court recessed for the evening.

On the morning of December 8, Moore resumed his argument, followed by his colleague, J. Lindsay Almond, Virginia's Attorney General. Following this argument, Assistant United States Attorney General J. Lee Rankin, presented the U.S. government's amicus curiae brief on behalf of the appellants, which showed its support for desegregation in public education. In the afternoon, Robert Carter began arguments in the Kansas case, and Paul Wilson, Attorney General for the state of Kansas, followed him in rebuttal.

On December 9, after James Nabrit and Milton Korman debated Bolling , and Louis Redding, Jack Greenberg, and Delaware's Attorney General, H. Albert Young argued Gebhart , the Court recessed. The attorneys, the plaintiffs, the defendants, and the nation waited five months and eight days to receive the unanimous opinion of Chief Justice Earl Warren's court, which declared, "in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place."

The Warren Court

In September 1953, President Eisenhower had appointed Earl Warren, governor of California, as the new Supreme Court chief justice. Eisenhower believed Warren would follow a moderate course of action toward desegregation. His feelings regarding the appointment are detailed in the closing paragraphs of a letter he wrote to E. E. "Swede" Hazlett, a childhood friend (shown above). On the issue of segregation, Eisenhower believed that the new Warren court would "be very moderate and accord a maximum initiative to local courts."

In his brief to the Warren Court that December, Thurgood Marshall described the separate but equal ruling as erroneous and called for an immediate reversal under the 14th Amendment. He argued that it allowed the government to prohibit any state action based on race, including segregation in public schools. The defense countered this interpretation pointing to several states that were practicing segregation at the time they ratified the 14th Amendment. Surely they would not have done so if they had believed the 14th Amendment applied to segregation laws. The U.S. Department of Justice also filed a brief; it was in favor of desegregation but asked for a gradual changeover.

Over the next few months, the new chief justice worked to bring the splintered Court together. He knew that clear guidelines and gradual implementation were going to be important considerations, as the largest concern remaining among the justices was the racial unrest that would doubtless follow their ruling.

The Supreme Court Ruling

Finally, on May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren read the unanimous opinion: school segregation by law was unconstitutional (shown above). Arguments were to be heard during the next term to determine exactly how the ruling would be imposed.

Just over one year later, on May 31, 1955, Warren read the Court's unanimous decision, now referred to as Brown II (also shown above). It instructed states to begin desegregation plans "with all deliberate speed." Warren employed careful wording in order to ensure backing of the full Court in his official judgment.

The Brown decision was a watershed in American legal and civil rights history because it overturned the "separate but equal" doctrine first articulated in the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896. By overturning Plessy , the Court ended America's 58-year-long practice of legal racial segregation and paved the way for the integration of America's public school systems.

Despite two unanimous decisions and careful, if not vague, wording, there was considerable resistance to the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education . In addition to the obvious disapproving segregationists were some constitutional scholars who felt that the decision went against legal tradition by relying heavily on data supplied by social scientists rather than precedent or established law. Supporters of judicial restraint believed the Court had overstepped its constitutional powers by essentially writing new law.

However, minority groups and members of the Civil Rights Movement were buoyed by the Brown decision even without specific directions for implementation. Proponents of judicial activism believed the Supreme Court had appropriately used its position to adapt the basis of the Constitution to address new problems in new times. The Warren Court stayed this course for the next 15 years, deciding cases that significantly affected not only race relations, but also the administration of criminal justice, the operation of the political process, and the separation of church and state.

Parts of this text were adapted from an article written by Mary Frances Greene, a teacher at Marie Murphy School in Wilmette, IL.

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

1954: brown v. board of education.

On May 17, 1954, in a landmark decision in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the U.S. Supreme Court declared state laws establishing separate public schools for students of different races to be unconstitutional. The decision dismantled the legal framework for racial segregation in public schools and Jim Crow laws, which limited the rights of African Americans, particularly in the South.

Segregation in Schools

Naacp challenges segregation in court, separate, but equal has 'no place', brown v board quick facts.

What is it? A landmark Supreme Court case.

Significance: Ended 'Separate, but equal,' desegregated public schools.

Date: May 17, 1954

Associated Sites: Brown v Board of Education National Historic Site; US Supreme Court Building

You Might Also Like

- brown v. board of education national historical park

- little rock central high school national historic site

- civil rights

- civil rights movement

- desegregation

- african american history

- brown v. the board of education of topeka

- public education

Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park , Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site

Last updated: July 12, 2023

Street Law Inc. Case Summary Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Street Law Case Summary

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Argued: December 9–11, 1952

Reargued : December 7–9, 1953

Decided : May 17, 1954

In 1868, the 14 th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in the wake of the Civil War. It says that states must give people equal protection of the laws and empowered Congress to pass laws to enforce the provisions of the Amendment. Although Congress attempted to outlaw racial segregation in places like hotels and theaters with the Civil Rights Act of 1875, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that law unconstitutional because it regulated private conduct. A few years later, the Supreme Court affirmed the legality of segregation in public facilities in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision . There, the justices said that as long as segregated facilities were of equal quality, segregation did not violate the U.S. Constitution. This concept was known as “separate but equal” and provided the legal foundation for Jim Crow segregation. In Plessy , the Supreme Court said that segregation was a matter of social equality, not legal equality; therefore, the justice system could not interfere. “If one race be inferior to the other socially, the constitution of the United States cannot put them on the same plane.”

By the 1950s, many public facilities had been segregated by race for decades, including many schools across the country. This case is about whether such racial segregation violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14 th Amendment.

In the early 1950s, Linda Brown was a young African American student in Topeka, Kansas. Every day she and her sister, Terry Lynn, had to walk through the Rock Island Railroad Switchyard to get to the bus stop for the ride to the all-Black Monroe School. Linda Brown tried to gain admission to the Sumner School, which was closer to her house, but her application was denied by the Board of Education of Topeka because of her race. The Sumner School was for White children only.

At the time of the Brown case, a Kansas statute permitted, but did not require, cities of more than 15,000 people to maintain separate school facilities for Black and White students. On that basis, the Board of Education of Topeka elected to establish segregated elementary schools.

The Browns felt that the decision of the Board violated the Constitution. They and a group of parents of students denied permission to White-only schools sued the Board of Education of Topeka, alleging that the segregated school system deprived Linda Brown of the equal protection of the laws required under the 14 th Amendment.

The federal district court decided that segregation in public education had a detrimental (harmful) effect upon Black children, but the court denied that there was any violation of Brown’s rights because of the “separate but equal” doctrine established in Plessy. The court said that the schools were substantially equal with respect to buildings, transportation, curricula, and educational qualifications of teachers. The Browns asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review that decision, and it agreed to do so. The Court combined the Brown’s case with similar cases from South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware.

Does segregation of public schools by race violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14 th Amendment?

Constitutional Amendment and Supreme Court Precedents

- 14 th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

“No State shall…deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

- Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

A Louisiana law required railroad companies to provide equal but separate facilities for White and Black passengers. A mixed-race customer named Homer Plessy rode in the Whites-only car and was arrested. Plessy argued that the Louisiana law violated the 14 th Amendment by treating Black passengers as inferior to White passengers. The Supreme Court declared that segregation was legal as long as facilities provided to each race were equal. The justices reasoned that the legal separation of the races did not automatically imply that African Americans were inferior, and that legislation and court rulings could not overcome social prejudices. Justice Harlan wrote a strong dissent, arguing that segregation violated the Constitution because it permitted and enforced inequality among people of different races.

- Sweatt v. Painter (1950)

Herman Sweatt was rejected from the University of Texas School of Law because he was African American. He sued school officials alleging a violation of the 14 th Amendment. The Supreme Court examined the educational opportunities at the University of Texas School of Law and the Texas State University for Negroes’ new law school and determined that the facilities, curricula, faculty, and other tangible factors were not equal. Therefore, they ruled that Sweatt’s rights had been violated. In addition to the more straightforward criteria the justices examined at the two schools, they reasoned that other factors, such as the reputation of the faculty and influence of the alumni, could not be equalized.

Arguments for Brown (petitioner)

- The 14 th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause promises equal protection of the laws. That means that states cannot treat people differently based on their race without an extremely good reason. There is not a good reason to keep Black children and White children from attending the same schools.

- Racial segregation in public schools reduces the benefits of education to Black children, solely based on their race. Schools for Black children are often inadequate and have less money and other resources than schools for White children.

- Even if states were ordered by courts to “equalize” their segregated schools, the problems would not go away. State-sponsored segregation creates and reinforces feelings of superiority among White students and inferiority among Black students. Segregation places a badge of inferiority on the Black students, perpetuates a system of separation beyond school, and gives unequal benefits to White students as a result of their informal contacts with one another. It undermines Black students’ motivation to seek educational opportunities and damages identity formation.

- At least two of the high schools in Topeka, Kansas, were already desegregated with no negative effects. The policy should be consistent in all of Topeka’s public primary and secondary schools.

- Segregation is morally wrong.

Arguments for Board of Education of Topeka (respondent)

- The 14 th Amendment states that people should be treated equally; it does not state that people should be treated the same. Treating people equally means giving them what they need. This could include providing an educational environment in which they are most comfortable learning. White students are probably more comfortable learning with other White students; Black students are probably more comfortable learning with other Black students. These students do not have to attend the same schools to be treated equally under the law; they must simply be given an equal environment for learning.

- In Topeka, unlike in Sweatt v. Painter , the schools for Black and White students have similar, equal facilities.

- The United States has a federal system of government that leaves educational decision-making to state and local legislatures. States and local school boards should make decisions about the best environments for school-aged children.

- Housing and schooling have become interdependent. Segregated housing has led to and reinforced segregated schools. Students might need to travel far away from their local school to attend an integrated school. This places a heavy burden on local government to deal with the changes.

The Supreme Court ruled for Linda Brown and the other students; the decision was unanimous. Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the opinion of the Court, ruling that segregation in public schools violates the 14 th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

The Court noted that public education was central to American life. Calling it “the very foundation of good citizenship,” they acknowledged that public education was not only necessary to prepare children for their future professions and to enable them to actively participate in the democratic process, but that it was also “a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values” present in their communities. The justices found it very unlikely that a child would be able to succeed in life without a good education. Access to such an education was thus “a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.”

The justices then compared the facilities that the Board of Education of Topeka provided for the education of Black children against those provided for White children. Ruling that they were substantially equal in “tangible factors” that could be measured easily (such as “buildings, curricula, and qualifications and salaries of teachers”), they concluded that the Court must instead examine the more subtle, intangible effect of segregation on the system of public education. The justices then said that separating children solely on the basis of race created a feeling of inferiority in the “hearts and minds” of African American children. Segregating children in public education created and perpetuated the idea that Black children held a lower status in the community than White children, even if their separate educational facilities were substantially equal in “tangible” factors. This deprived Black children of some of the benefits they would receive in an integrated school. The opinion said, “We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place.” Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. This ruling was a clear departure from the reasoning in Plessy v. Ferguson , and, in many ways, it echoed aspects of Justice Harlan’s dissent in that earlier case.

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was a single decision signed by all nine Justices. The Court acknowledged the importance and potential controversy of this decision, so they acted uniformly to try to lessen dissent in society. The decision that ordered the desegregation of public schools was praised by many Americans who supported the civil rights movement.

One year after the decision, the Court addressed the implementation of its decision in a case known as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka II. Chief Justice Warren once again wrote an opinion for the unanimous Court. The Court acknowledged that desegregating public schools would take place in various ways, depending on the unique problems faced by individual school districts. After charging local school authorities with the responsibility for solving these problems, the Court instructed federal trial courts to oversee the process and determine whether local authorities were desegregating schools in good faith, mandating that desegregation take place with “with all deliberate speed.”

That language proved unfortunate, as it gave the Southern states an incentive to delay compliance with the Court’s mandate.

Many White people fought the implementation of the decision. In Little Rock, Arkansas, the school board agreed to desegregate its schools. But when nine African American students tried to enter Little Rock Central High School, those who still supported segregation, along with the Arkansas National Guard, physically blocked the African American students from entering the school. President Eisenhower quickly deployed the U.S. Army to enforce the integration decision by providing an armed escort to the African American students.

Resistance to integration led to further litigation. In Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (1964), the Court stated that “[t]he time for mere ‘deliberate speed’ has run out, and that phrase can no longer justify denying . . . school children their constitutional rights.”

Today all segregation by law ( de jure segregation) in public education is unconstitutional. However, many schools are still largely made up of students from a single racial or ethnic group because enrollment is assigned based on neighborhoods. This is call de facto segregation because it occurs in practice without a law mandating it.

License and restrictions

This license allows reusers to reproduce, distribute, perform, and display the material for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.

The reusers will not modify, adapt or create any derivative works from Street Law Inc. material.

John Jay College Social Justice Landmark Cases eReader Copyright © by John Jay College of Criminal Justice is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Brown Foundation Story

- Books for Kids

- Scholarships

- Visiting Scholars

- Make a Donation

- Audit Reports

- Building Blocks

- Timeline Poster

- Thurgood Marshall Book

- Myths vs. Truths

- Activity Booklets

- Traveling Exhibit

- The Brown Quarterly

- Black/White & Brown

- Background Overview

- Cases Before Brown

- Brown v. Board Visionary

- Combined Brown Cases

- Plaintiffs & Attorneys

- Opinions from the Courts

- Oral History

- The Preservation Effort

- Online Tour of Park

- Grand Opening & 50th Anniversary

- Brown Sites in Topeka

- Grants for Tours

- National Historic Site

- Speakers Bureau

- Contacts For Interviews

- Case Summaries

Brown Case - Brown v. Board

Brown et. al. v. The Board of Education of Topeka, et. al.

In Kansas there were eleven school integration cases dating from 1881 to 1949, prior to Brown in 1954. In many instances the schools for African American children were substandard facilities with out-of-date textbooks and often no basic school supplies. What was not in question was the dedication and qualifications of the African American teachers and principals assigned to these schools.

In response to numerous unsuccessful attempts to ensure equal opportunities for all children, African American community leaders and organizations stepped up efforts to change the education system. In the fall of 1950 members of the Topeka, Kansas, Chapter of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) agreed to again challenge the "separate but equal" doctrine governing public education.

The strategy was conceived by the chapter president, McKinley Burnett, the secretary Lucinda Todd and attorneys Charles Scott, John Scott, and Charles Bledsoe. For a period of two years Mr. Burnett had attempted to have Topeka Public School Officials simply chose to integrate schools because the Kansas law did not require segregated public schools only at the elementary level in first class cities. Filing suit against the District was a final attempt to secure integrated public schools.

Their plan involved enlisting the support of fellow NAACP members and personal friends as plaintiffs in what would be a class action suit filed against the Board of Education of Topeka Public Schools. A group of thirteen parents agreed to participate on behalf of their children (twenty children).

Each plaintiff was to watch the paper for enrollment dates and take their child to the school for white children that was nearest to their home. Once they attempted enrollment and were denied, they were to report back to the NAACP. This would provide the attorneys with the documentation needed to file a lawsuit against the Topeka School Board. The African American schools appeared equal in facilities and teacher salaries but some programs were not offered and some textbooks were not available. In addition, there were only four elementary schools for African American children as compared to eighteen for white children. This made attending neighborhood schools impossible for African American children. Junior and Senior high schools were integrated.

Oliver Brown was assigned as lead plaintiff, principally because he was the only man among the plaintiffs. On February 28, 1951 the NAACP filed their case as Oliver L. Brown et. al. vs. The Board of Education of Topeka (KS). The District Court ruled in favor of the school board and the case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. When the Topeka case made its way to the United States Supreme Court, it was combined with the other NAACP cases from Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia and Washington, D.C. The combined cases became known as Oliver L. Brown et. al. vs. The Board of Education of Topeka, et. al.

On May 17, 1954 at 12:52 p.m. the United States Supreme Court issued a unanimous decision that it was unconstitutional, violating the 14th amendment, to separate children in public schools for no other reason than their race. Brown vs. The Board of Education helped change America forever.

In 1979 a group of young attorneys were concerned about a policy in Topeka Public Schools that allowed open enrollment. Their fear was that this would lead to resegregation. They believed that with this type of choice white parents would shift their children to other schools creating predominately African American or predominately white schools. As a result these attorneys petitioned the federal court to reopen the original Brown case to determine if Topeka Public Schools had in fact ever complied with the court=s ruling of 1954.

This case is commonly known as Brown III. These young attorneys were Richard Jones, Joseph Johnson and Charles Scott, Jr. (son of one of the attorneys in the original case) in association with Chris Hansen from the ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) in New York. In the late 1980s Topeka Public Schools were found to be out of compliance. On October 28, 1992, after several appeals the U.S. Supreme Court denied Topeka Public School's petition to once again hear the Brown case. As a result the school was directed to develop plans for compliance and have since built three magnet schools. These schools are excellent facilities and make every effort to be racially balanced. Ironically one of these new schools is named after the Scott family attorneys for their role in the Brown case and civil rights. It is the Scott Computer and Mathematics Magnet School.

Make A Donation

The Brown Foundation succeeds because of your support. We use the support from individuals, businesses, and foundations to help ensure a sustained investment in children and youth and to foster programs that educate the public about Brown v. Board of Education in the context of the civil rights movement and to advance civic engagement.

Make a Donation Online here .

Learn more about how your donation will be used or find out how to mail in a donation on our donation page here .

View photos from past events here .

Quick Links:

Financial Audits Board of Directors

The Brown V. Board of Education Decision

This essay about the landmark Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education, outlines its significant impact on the United States, particularly in ending legal segregation in public schools on May 17, 1954. It explains how the case consolidated several challenges against segregated schooling across the country, leading to a unanimous Supreme Court decision that declared segregated schools inherently unequal under the Fourteenth Amendment. The ruling marked a monumental step in the civil rights movement, challenging societal norms and paving the way for further legislation and action towards racial equality. Despite resistance, especially in the South, the decision remains a pivotal moment in America’s ongoing journey towards justice and equality for all, symbolizing the potential for change through legal avenues and collective action.

How it works

May 17, 1954, witnessed a paradigm shift in American education and society with a landmark ruling from the United States Supreme Court. In the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, legal segregation in public schools was abolished, representing a monumental stride in the civil rights movement. This verdict not only overturned the precedent set by Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, which upheld the notion of “separate but equal,” but it also challenged the very essence of racial segregation in the United States.

The narrative of Brown v. Board of Education originates from various legal battles across the nation, all contesting the legality of segregated educational institutions. These disparate cases were consolidated into one under the banner of Oliver Brown, a concerned parent from Topeka, Kansas. The crux of the argument was deceptively simple yet profoundly impactful: segregated schools, irrespective of their purported equality, could never truly be equitable. This inherent inequality contravened the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Thurgood Marshall, who later ascended to become the first African American Supreme Court Justice, championed the plaintiffs’ cause, leaving an indelible mark on American law and society.

Chief Justice Earl Warren authored the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision, asserting that “in the realm of public education, the concept of ‘separate but equal’ is untenable, as segregated schools are inherently unequal.” This ruling transcended the confines of the case itself, reshaping societal and legal attitudes towards segregation and equality.

Nevertheless, the aftermath of the Brown ruling was fraught with challenges as the transition to integration encountered widespread resistance, particularly in the Southern states. “Massive resistance” campaigns and the subsequent Little Rock Crisis vividly illustrated the entrenched obstacles to desegregation. Despite these impediments, Brown v. Board of Education galvanized further civil rights activism, sparking initiatives such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the formation of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and ultimately, the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education decision transcends its immediate impact on education and civil rights. It serves as a testament to the potency of judicial review and the pivotal role of the Supreme Court in shaping societal norms. Most importantly, it reaffirms the fundamental principle that legal equality must not be compromised based on race or any other arbitrary distinction.

In hindsight, May 17, 1954, signifies more than a legal triumph; it symbolizes a pivotal juncture in America’s quest to actualize its core tenets of liberty and justice for all. While the quest for equality and justice endures, the Brown v. Board of Education ruling stands as a beacon of hope and a testament to the progress attainable when individuals confront systemic injustice.

Cite this page

The Brown v. Board of Education Decision. (2024, Mar 18). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-brown-v-board-of-education-decision/

"The Brown v. Board of Education Decision." PapersOwl.com , 18 Mar 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-brown-v-board-of-education-decision/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Brown v. Board of Education Decision . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-brown-v-board-of-education-decision/ [Accessed: 13 Apr. 2024]

"The Brown v. Board of Education Decision." PapersOwl.com, Mar 18, 2024. Accessed April 13, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/the-brown-v-board-of-education-decision/

"The Brown v. Board of Education Decision," PapersOwl.com , 18-Mar-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-brown-v-board-of-education-decision/. [Accessed: 13-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Brown v. Board of Education Decision . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-brown-v-board-of-education-decision/ [Accessed: 13-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Board of Education of Topeka was a landmark 1954 Supreme Court case in which the justices ruled unanimously that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional. Brown v ...

The 1954 decision found that the historical evidence bearing on the issue was inconclusive. Brown v. Board of Education, case in which, on May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously (9-0) that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. It was one of the most important cases in the Court's history, and it helped ...

Case Summary of Brown v. Board of Education: Oliver Brown was denied admission into a white school. As a representative of a class action suit, Brown filed a claim alleging that laws permitting segregation in public schools were a violation of the 14 th Amendment equal protection clause. After the District Court upheld segregation using Plessy v.

Kentucky (1908) Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), [1] was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segregated schools are otherwise equal in quality. The decision partially overruled the Court's 1896 ...

In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) a unanimous Supreme Court declared that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional. The Court declared "separate" educational facilities "inherently unequal.". The case electrified the nation, and remains a landmark in legal history and a milestone in civil rights history.

That is why the case is called Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, even though the case involved plaintiffs in multiple states. Most simply refer to it as Brown v. Board. The Supreme Court took the relatively unusual step in Brown v. Board of hearing oral arguments twice, once in 1953 and again in 1954. The second round of oral arguments was ...

Board of Education . Brown v. Board of Education (of Topeka), (1954) U.S. Supreme Court case in which the court ruled unanimously that racial segregation in public schools violated the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The amendment says that no state may deny equal protection of the laws to any person within its jurisdiction.

Ferguson case. On May 17, 1954, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. State-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th amendment and was therefore unconstitutional. This historic decision marked the end of ...

This case was the consolidation of cases arising in Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, and Washington D.C. relating to the segregation of public schools on the basis of race. In each of the cases, African American students had been denied admittance to certain public schools based on laws allowing public education to be segregated by ...

U.S. Supreme Court. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Argued December 9, 1952 Reargued December 8, 1953 Decided May 17, 1954* APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS MR. CHIEF JUSTICE WARREN delivered the opinion of the Court.

In a subsequent opinion on the question of relief, commonly referred to as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (II), argued April 11-14, 1955, and decided on May 31 of that year, Warren ordered the district courts and local school authorities to take appropriate steps to integrate public schools in their jurisdictions "with all deliberate ...

The Supreme Court's opinion in the Brown v. Board of Education case of 1954 legally ended decades of racial segregation in America's public schools. Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case. State-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th Amendment and was therefore ...

Citation349 U.S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed. 1083, 1955 U.S. 734. Brief Fact Summary. In [Brown I], the Supreme Court of the United States (Supreme Court) held that racial discrimination in public education is unconstitutional. Synopsis of Rule of Law. In fashioning and effectuating decrees, which require varied solutions, the courts will.

Citation347 U.S.483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873, 1954 U.S. 2094. Brief Fact Summary. Black children were denied admission to schools attended by white children under laws that permitted or required segregation by race. The children sued. Synopsis of Rule of Law.

1954: Brown v. Board of Education. On May 17, 1954, in a landmark decision in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the U.S. Supreme Court declared state laws establishing separate public schools for students of different races to be unconstitutional. The decision dismantled the legal framework for racial segregation in ...

Street Law Case Summary . Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. Argued: December 9-11, 1952 Reargued: December 7-9, 1953. Decided: May 17, 1954. Background. In 1868, the 14 th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in the wake of the Civil War. It says that states must give people equal protection of the laws and empowered Congress to pass laws to enforce the provisions of the ...

Citation. 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686, 98 L.Ed. 873 (1954). Brief Fact Summary. Plaintiffs were denied admission to public schools on the basis of race and challenged the decisions in this consolidated opinion. Synopsis of Rule of Law. In the field of public education, the doctrine of separate but equal has no place.

The combined cases became known as Oliver L. Brown et. al. vs. The Board of Education of Topeka, et. al. On May 17, 1954 at 12:52 p.m. the United States Supreme Court issued a unanimous decision that it was unconstitutional, violating the 14th amendment, to separate children in public schools for no other reason than their race. Brown vs.

Street Law Case Summary ... Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) Argued: December 9-11, 1952 . Reargued: December 7-9, 1953 . Decided: May 17, 1954. Background . In 1868, the 14. th. Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in the wake of the Civil War. It says

Read Brown v. Board of Educ. of Topeka, 892 F.2d 851, see flags on bad law, and search Casetext's comprehensive legal database ... Summary of this case from Robinson v. Kansas. See 2 Summaries. Opinion. No. 87-1668. ... Id. art. 6, § 2; State ex rel. Miller v. Board of Education, 212 Kan. 482, 511 P.2d 705, 709 (1973). Because the State ...

In the Kansas case, Brown v.Board of Education, the plaintiffs are Negro children of elementary school age residing in Topeka.They brought this action in the United States District Court for the District of Kansas to enjoin enforcement of a Kansas statute which permits, but does not require, cities of more than 15,000 population to maintain separate school facilities for Negro and white students.

Essay Example: May 17, 1954, witnessed a paradigm shift in American education and society with a landmark ruling from the United States Supreme Court. In the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, legal segregation in public schools was abolished, representing a monumental stride

These cases come to us from the States of Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware. They are pre-mised on different facts and different local conditions, but a common legal question justifies their consideration together in this consolidated opinion.' ' In the Kansas case, Brown v. Board of Education, the plaintiffs