By the People: Essays on Democracy

Harvard Kennedy School faculty explore aspects of democracy in their own words—from increasing civic participation and decreasing extreme partisanship to strengthening democratic institutions and making them more fair.

Winter 2020

By Archon Fung , Nancy Gibbs , Tarek Masoud , Julia Minson , Cornell William Brooks , Jane Mansbridge , Arthur Brooks , Pippa Norris , Benjamin Schneer

The basic terms of democratic governance are shifting before our eyes, and we don’t know what the future holds. Some fear the rise of hateful populism and the collapse of democratic norms and practices. Others see opportunities for marginalized people and groups to exercise greater voice and influence. At the Kennedy School, we are striving to produce ideas and insights to meet these great uncertainties and to help make democratic governance successful in the future. In the pages that follow, you can read about the varied ways our faculty members think about facets of democracy and democratic institutions and making democracy better in practice.

Explore essays on democracy

Archon fung: we voted, nancy gibbs: truth and trust, tarek masoud: a fragile state, julia minson: just listen, cornell william brooks: democracy behind bars, jane mansbridge: a teachable skill, arthur brooks: healthy competition, pippa norris: kicking the sandcastle, benjamin schneer: drawing a line.

Get smart & reliable public policy insights right in your inbox.

Beyond Intractability

The Hyper-Polarization Challenge to the Conflict Resolution Field We invite you to participate in an online exploration of what those with conflict and peacebuilding expertise can do to help defend liberal democracies and encourage them live up to their ideals.

Follow BI and the Hyper-Polarization Discussion on BI's New Substack Newsletter .

Hyper-Polarization, COVID, Racism, and the Constructive Conflict Initiative Read about (and contribute to) the Constructive Conflict Initiative and its associated Blog —our effort to assemble what we collectively know about how to move beyond our hyperpolarized politics and start solving society's problems.

By Sarah Peterson

Originally published in July 2003, Current Implications added by Heidi Burgess in December, 2019

Current Implications

When Sarah wrote this essay in 2003, social media existed, but it hadn't yet become popular or widespread. Facebook and Twitter hadn't started yet (Facebook started in 2004, Twitter in 2006.) More ....

What is Tolerance?

| Hobbes: "How are you doing on your New Year's resolutions?" Calvin: "I didn't make any. See, in order to improve oneself, one must have some idea of what's 'good.' That implies certain values. But as we all know, values are relative. Every system of belief is equally valid and we need to tolerate diversity. Virtue isn't 'better' than vice. It's just different." Hobbes: "I don't know if I can tolerate that much tolerance." Calvin: "I refuse to be victimized by notions of virtuous behavior." -- |

Tolerance is the appreciation of diversity and the ability to live and let others live. It is the ability to exercise a fair and objective attitude towards those whose opinions, practices, religion, nationality, and so on differ from one's own.[1] As William Ury notes, "tolerance is not just agreeing with one another or remaining indifferent in the face of injustice, but rather showing respect for the essential humanity in every person."[2]

Intolerance is the failure to appreciate and respect the practices, opinions and beliefs of another group. For instance, there is a high degree of intolerance between Israeli Jews and Palestinians who are at odds over issues of identity , security , self-determination , statehood, the right of return for refugees, the status of Jerusalem and many other issues. The result is continuing intergroup conflict and violence .

Why Does Tolerance Matter?

At a post-9/11 conference on multiculturalism in the United States, participants asked, "How can we be tolerant of those who are intolerant of us?"[3] For many, tolerating intolerance is neither acceptable nor possible.

Though tolerance may seem an impossible exercise in certain situations -- as illustrated by Hobbes in the inset box on the right -- being tolerant, nonetheless, remains key to easing hostile tensions between groups and to helping communities move past intractable conflict. That is because tolerance is integral to different groups relating to one another in a respectful and understanding way. In cases where communities have been deeply entrenched in violent conflict, being tolerant helps the affected groups endure the pain of the past and resolve their differences. In Rwanda, the Hutus and the Tutsis have tolerated a reconciliation process , which has helped them to work through their anger and resentment towards one another.

The Origins of Intolerance

In situations where conditions are economically depressed and politically charged, groups and individuals may find it hard to tolerate those that are different from them or have caused them harm. In such cases, discrimination, dehumanization, repression, and violence may occur. This can be seen in the context of Kosovo, where Kosovar Alabanians, grappling with poverty and unemployment, needed a scapegoat, and supported an aggressive Serbian attack against neighboring Bosnian Muslim and Croatian neighbors.

The Consequences of Intolerance

Intolerance will drive groups apart, creating a sense of permanent separation between them. For example, though the laws of apartheid in South Africa were abolished nine years ago, there still exists a noticeable level of personal separation between black and white South Africans, as evidenced in studies on the levels of perceived social distance between the two groups.[4] This continued racial division perpetuates the problems of intergroup resentment and hostility.

| |

How is Intolerance Perpetuated?

Between Individuals: In the absence of their own experiences, individuals base their impressions and opinions of one another on assumptions. These assumptions can be influenced by the positive or negative beliefs of those who are either closest or most influential in their lives, including parents or other family members, colleagues, educators, and/or role models.

In the Media: Individual attitudes are influenced by the images of other groups in the media, and the press. For instance, many Serbian communities believed that the western media portrayed a negative image of the Serbian people during the NATO bombing in Kosovo and Serbia.[5] This de-humanization may have contributed to the West's willingness to bomb Serbia. However, there are studies that suggest media images may not influence individuals in all cases. For example, a study conducted on stereotypes discovered people of specific towns in southeastern Australia did not agree with the negative stereotypes of Muslims presented in the media.[6]

In Education: There exists school curriculum and educational literature that provide biased and/or negative historical accounts of world cultures. Education or schooling based on myths can demonize and dehumanize other cultures rather than promote cultural understanding and a tolerance for diversity and differences.

| This post is also part of the

|

What Can Be Done to Deal with Intolerance?

To encourage tolerance, parties to a conflict and third parties must remind themselves and others that tolerating tolerance is preferable to tolerating intolerance. Following are some useful strategies that may be used as tools to promote tolerance.

Intergroup Contact: There is evidence that casual intergroup contact does not necessarily reduce intergroup tensions, and may in fact exacerbate existing animosities. However, through intimate intergroup contact, groups will base their opinions of one another on personal experiences, which can reduce prejudices . Intimate intergroup contact should be sustained over a week or longer in order for it to be effective.[7]

In Dialogue: To enhance communication between both sides, dialogue mechanisms such as dialogue groups or problem solving workshops provide opportunities for both sides to express their needs and interests. In such cases, actors engaged in the workshops or similar forums feel their concerns have been heard and recognized. Restorative justice programs such as victim-offender mediation provide this kind of opportunity as well. For instance, through victim-offender mediation, victims can ask for an apology from the offender and the offender can make restitution and ask for forgiveness.[8]

What Individuals Can Do

Individuals should continually focus on being tolerant of others in their daily lives. This involves consciously challenging the stereotypes and assumptions that they typically encounter in making decisions about others and/or working with others either in a social or a professional environment.

What the Media Can Do

The media should use positive images to promote understanding and cultural sensitivity. The more groups and individuals are exposed to positive media messages about other cultures, the less they are likely to find faults with one another -- particularly those communities who have little access to the outside world and are susceptible to what the media tells them. See the section on stereotypes to learn more about how the media perpetuate negative images of different groups.

What the Educational System Can Do

Educators are instrumental in promoting tolerance and peaceful coexistence . For instance, schools that create a tolerant environment help young people respect and understand different cultures. In Israel, an Arab and Israeli community called Neve Shalom or Wahat Al-Salam ("Oasis of Peace") created a school designed to support inter-cultural understanding by providing children between the first and sixth grades the opportunity to learn and grow together in a tolerant environment.[9]

What Other Third Parties Can Do

Conflict transformation NGOs (non-governmental organizations) and other actors in the field of peacebuilding can offer mechanisms such as trainings to help parties to a conflict communicate better with one another. For instance, several organizations have launched a series of projects in Macedonia that aim to reduce tensions between the country's Albanian, Romani and Macedonian populations, including activities that promote democracy, ethnic tolerance, and respect for human rights.[10]

International organizations need to find ways to enshrine the principles of tolerance in policy. For instance, the United Nations has already created The Declaration of Moral Principles on Tolerance, adopted and signed in Paris by UNESCO's 185 member states on Nov. 16, 1995, which qualifies tolerance as a moral, political, and legal requirement for individuals, groups, and states.[11]

Governments also should aim to institutionalize policies of tolerance. For example, in South Africa, the Education Ministry has advocated the integration of a public school tolerance curriculum into the classroom; the curriculum promotes a holistic approach to learning . The United States government has recognized one week a year as international education week, encouraging schools, organizations, institutions, and individuals to engage in projects and exchanges to heighten global awareness of cultural differences.

The Diaspora community can also play an important role in promoting and sustaining tolerance. They can provide resources to ease tensions and affect institutional policies in a positive way. For example, Jewish, Irish, and Islamic communities have contributed to the peacebuilding effort within their places of origin from their places of residence in the United States. [12]

When Sarah wrote this essay in 2003, social media existed, but it hadn't yet become popular or widespread. Facebook and Twitter hadn't started yet (Facebook started in 2004, Twitter in 2006.)

In addition, while the conflict between the right and the left and the different races certainly existed in the United States, it was not nearly as escalated or polarized as it is now in 2019. For those reasons (and others), the original version of this essay didn't discuss political or racial tolerance or intolerance in the United States. Rather than re-writing the original essay, all of which is still valid, I have chosen to update it with these "Current Implications."

In 2019, the intolerance between the Left and the Right in the United States has gotten extreme. Neither side is willing to accept the legitimacy of the values, beliefs, or actions of the other side, and they are not willing to tolerate those values, beliefs or actions whatsoever. That means, in essence, that they will not tolerate the people who hold those views, and are doing everything they can to disempower, delegitimize, and in some cases, dehumanize the other side.

Further, while intolerance is not new, efforts to spread and strengthen it have been greatly enhanced with the current day traditional media and social media environments: the proliferation of cable channels that allow narrowcasting to particular audiences, and Facebook and Twitter (among many others) that serve people only information that corresponds to (or even strengthens) their already biased views. The availability of such information channels both helps spread intolerance; it also makes the effects of that intolerance more harmful.

Intolerance and its correlaries (disempowerment, delegitimization, and dehumanization) are perhaps clearest on the right, as the right currently holds the U.S. presidency and controls the statehouses in many states. This gives them more power to assert their views and disempower, delegitimize and dehumanize the other. (Consider the growing restrictions on minority voting rights, the delegitimization of transgendered people and supporters, and the dehumanizing treatment of would-be immigrants at the southern border.)

But the left is doing the same thing when it can. By accusing the right of being "haters," the left delegitimizes the right's values and beliefs, many of which are not borne of animus, but rather a combination of bad information being spewed by fake news in social and regular media, and natural neurobiological tendencies which cause half of the population to be biologically more fearful, more reluctant to change, and more accepting of (and needing) a strong leader.

Put together, such attitudes feed upon one another, causing an apparently never-ending escalation and polarization spiral of intolerance. Efforts to build understanding and tolerance, just as described in the original article, are still much needed today both in the United States and across the world.

The good news is that many such efforts exist. The Bridge Alliance , for instance, is an organization of almost 100 member organizations which are working to bridge the right-left divide in the U.S. While the Bridge Alliance doesn't use the term "tolerance" or "coexistence" in its framing " Four Principles ," they do call for U.S. leaders and the population to "work together" to meet our challenges. "Working together" requires not only "tolerance for " and "coexistence with" the other side; it also requires respect for other people's views. That is something that many of the member organizations are trying to establish with red-blue dialogues, public fora, and other bridge-building activities. We need much, much more of that now in 2019 if we are to be able to strengthen tolerance against the current intolerance onslaught.

One other thing we'd like to mention that was touched upon in the original article, but not explored much, is what can and should be done when the views or actions taken by the other side are so abhorent that they cannot and should not be tolerated? A subset of that question is one Sarah did pose above '"How can we be tolerant of those who are intolerant of us?"[3] For many, tolerating intolerance is neither acceptable nor possible." Sarah answers that by arguing that tolerance is beneficial--by implication, even in those situations.

What she doesn't explicitly consider, however, is the context of the intolerance. If one is considering the beliefs or behavior of another that doesn't affect anyone else--a personal decision to live in a particular way (such as following a particular religion for example), we would agree that tolerance is almost always beneficial, as it is more likely to lead to interpersonal trust and further understanding.

However, if one is considering beliefs or actions of another that does affect other people--particularly actions that affect large numbers of people, then that is a different situation. We do not tolerate policies that allow the widespread dissemination of fake news and allow foreign governments to manipulate our minds such that they can manipulate our elections. That, in our minds is intolerable. So too are actions that destroy the rule of law in this country; actions that threaten our democratic system.

But that doesn't mean that we should respond to intolerance in kind. Rather, we would argue, one should respond to intolerance with respectful dissent--explaining why the intolerance is unfairly stereotyping an entire group of people; explaining why such stereotyping is both untrue and harmful; why a particular action is unacceptable because it threatens the integrity of our democratic system, explaining alternative ways of getting one's needs met.

This can be done without attacking the people who are guilty of intolerance with direct personal attacks--calling them "haters," or shaming them for having voted a particular way. That just hardens the other sides' intolerance.

Still, reason-based arguments probably won't be accepted right away. Much neuroscience research explains that emotions trump facts and that people won't change their minds when presented with alternative facts--they will just reject those facts. But if people are presented with facts in the form of respectful discussion instead of personal attacks, that is both a factual and an emotional approach that can help de-escalate tensions and eventually allow for the development of tolerance. Personal attacks on the intolerant will not do that. So when Sarah asked whether one should tolerate intolerance, I would say "no, one should not." But that doesn't mean that you have to treat the intolerant person disrespectfully or "intolerantly." Rather, model good, respectful behavior. Model the behavior you would like them to adopt. And use that to try to fight the intolerance, rather than simply "tolerating it."

-- Heidi and Guy Burgess. December, 2019.

Back to Essay Top

---------------------------------------------------------

[1] The American Heritage Dictionary (New York: Dell Publishing, 1994).

[2] William Ury, Getting To Peace (New York: The Penguin Group, 1999), 127.

[3] As identified by Serge Schmemann, a New York Times columnist noted in his piece of Dec. 29, 2002, in The New York Times entitled "The Burden of Tolerance in a World of Division" that tolerance is a burden rather than a blessing in today's society.

[4] Jannie Malan, "From Exclusive Aversion to Inclusive Coexistence," Short Paper, African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), Conference on Coexistence Community Consultations, Durban, South Africa, January 2003, 6.

[5] As noted by Susan Sachs, a New York Times columnist in her piece of Dec. 16, 2001, in The New York Times entitled "In One Muslim Land, an Effort to Enforce Lessons of Tolerance."

[6] Amber Hague, "Attitudes of high school students and teachers towards Muslims and Islam in a southeaster Australian community," Intercultural Education 2 (2001): 185-196.

[7] Yehuda Amir, "Contact Hypothesis in Ethnic Relations," in Weiner, Eugene, eds. The Handbook of Interethnic Coexistence (New York: The Continuing Publishing Company, 2000), 162-181.

[8] The Ukrainian Centre for Common Ground has launched a successful restorative justice project. Information available on-line at www.sfcg.org .

[9] Neve Shalom homepage [on-line]; available at www.nswas.com ; Internet.

[10] Lessons in Tolerance after Conflict. http://www.beyondintractability.org/library/external-resource?biblio=9997

[11] "A Global Quest for Tolerance" [article on-line] (UNESCO, 1995, accessed 11 February 2003); available at http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-sciences/themes/fight-against-discrimination/promoting-tolerance/ ; Internet.

[12] Louis Kriesberg, "Coexistence and the Reconciliation of Communal Conflicts." In Weiner, Eugene, eds. The Handbook of Interethnic Coexistence (New York: The Continuing Publishing Company, 2000), 182-198.

Use the following to cite this article: Peterson, Sarah. "Tolerance." Beyond Intractability . Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: July 2003 < http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/tolerance >.

Additional Resources

The intractable conflict challenge.

Our inability to constructively handle intractable conflict is the most serious, and the most neglected, problem facing humanity. Solving today's tough problems depends upon finding better ways of dealing with these conflicts. More...

Selected Recent BI Posts Including Hyper-Polarization Posts

- Democratic Subversion - Part 2 -- Part 2 of 2 newsletters looking at an old, but eerily accurate, description of political events in the United States over the last ten-twenty years, explaining why we are well on our way to a destroyed democracy and what we can do about it.

- Democratic Subversion - Part 1 -- Part 1 of 2 newsletters looking at an old, but eerily accurate, way of looking at the chain of political events that have done so much to undermine democratic societies in recent decades.

- Massively Parallel Peace and Democracy Building Links for the Week of June 9, 2024 -- More links to interesting things we -- and our readers -- are reading.

Get the Newsletter Check Out Our Quick Start Guide

Educators Consider a low-cost BI-based custom text .

Constructive Conflict Initiative

Join Us in calling for a dramatic expansion of efforts to limit the destructiveness of intractable conflict.

Things You Can Do to Help Ideas

Practical things we can all do to limit the destructive conflicts threatening our future.

Conflict Frontiers

A free, open, online seminar exploring new approaches for addressing difficult and intractable conflicts. Major topic areas include:

Scale, Complexity, & Intractability

Massively Parallel Peacebuilding

Authoritarian Populism

Constructive Confrontation

Conflict Fundamentals

An look at to the fundamental building blocks of the peace and conflict field covering both “tractable” and intractable conflict.

Beyond Intractability / CRInfo Knowledge Base

Home / Browse | Essays | Search | About

BI in Context

Links to thought-provoking articles exploring the larger, societal dimension of intractability.

Colleague Activities

Information about interesting conflict and peacebuilding efforts.

Disclaimer: All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Beyond Intractability or the Conflict Information Consortium.

Beyond Intractability

Unless otherwise noted on individual pages, all content is... Copyright © 2003-2022 The Beyond Intractability Project c/o the Conflict Information Consortium All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced without prior written permission.

Guidelines for Using Beyond Intractability resources.

Citing Beyond Intractability resources.

Photo Credits for Homepage, Sidebars, and Landing Pages

Contact Beyond Intractability Privacy Policy The Beyond Intractability Knowledge Base Project Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess , Co-Directors and Editors c/o Conflict Information Consortium Mailing Address: Beyond Intractability, #1188, 1601 29th St. Suite 1292, Boulder CO 80301, USA Contact Form

Powered by Drupal

production_1

Explore our publications and services.

University of michigan press.

Publishes award-winning books that advance humanities and social science fields, as well as English language teaching and regional resources.

Michigan Publishing Services

Assists the U-M community of faculty, staff, and students in achieving their publishing ambitions.

Deep Blue Repositories

Share and access research data, articles, chapters, dissertations and more produced by the U-M community.

A community-based, open source publishing platform that helps publishers present the full richness of their authors' research outputs in a durable, discoverable, accessible and flexible form. Developed by Michigan Publishing and University of Michigan Library.

- shopping_cart Cart

Browse Our Books

- See All Books

- Distributed Clients

Feature Selections

- New Releases

- Forthcoming

- Bestsellers

- Great Lakes

English Language Teaching

- Companion Websites

- Subject Index

- Resources for Teachers and Students

By Skill Area

- Academic Skills/EAP

- Teacher Training

For Authors

Prospective authors.

- Why Publish with Michigan?

- Open Access

- Our Publishing Program

- Submission Guidelines

Author's Guide

- Introduction

- Final Manuscript Preparation

- Production Process

- Marketing and Sales

- Guidelines for Indexing

For Instructors

- Exam Copies

- Desk Copies

For Librarians and Booksellers

- Our Ebook Collection

- Ordering Information for Booksellers

- Review Copies

Background and Contacts

- About the Press

- Customer Service

- Staff Directory

News and Information

- Conferences and Events

Policies and Requests

- Rights and Permissions

- Accessibility

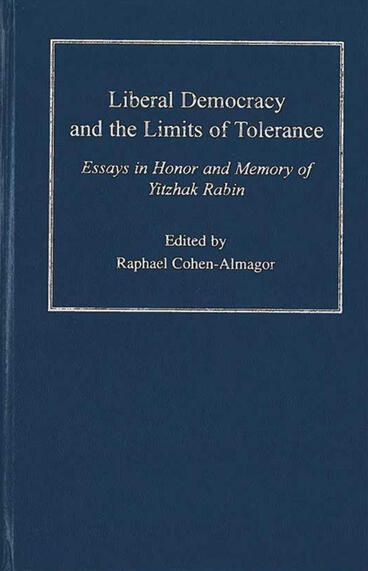

Liberal Democracy and the Limits of Tolerance

Essays in honor and memory of yitzhak rabin.

How to prevent the enemies of democracy from using its freedoms to attack its existence

Look Inside

Table of Contents:

- The legacy of Yitzhak Rabin / Lea Rabin

- The cost of communicative tolerance / Frederick Schauer

- Protest and tolerance: legal values and the control of public-order policing / David Feldman

- Freedom of speech and political violence / Owen Fiss

- Boundaries of freedom of expression before and after Prime Minister Rabin's assassination / Raphael Cohen-Almagor

- The dual threat to modern citizenship: liberal indifference and nonconsensual violence / Harvey Chisick

- The paradox of Israeli civil disobedience and political revolt in light of the Jewish tradition / Sam Lehman-Wilzig

- Should hate speech be free speech? John Stuart Mill and the limits of tolerance / L.W. Sumner

- Holocaust denial, equality, and harm: boundaries of liberty and tolerance in a liberal democracy / Irwin Cotler

- The regulation of racist expression / Richard Moon

- Freedom of the press and terrorism / Joseph Eliot Magnet

- Reporting on political extremists in the United States: the unabomber, the Ku Klux Klan, and the militias / David E. Boeyink

- Pragmatic liberalism and the press in violent times / Edmund B. Lambeth

- Protecting wider purposes: hate speech, communication, and the international community / David Goldberg

- Riding the electronic tiger: censorship in global, distributed networks / J. Michael Jaffe.

Description

An irony inherent in all political systems is that the principles that underlie and characterize them can also endanger and destroy them. This collection examines the limits that need to be imposed on democracy, liberty, and tolerance in order to ensure the survival of the societies that cherish them. The essays in this volume consider the philosophical difficulties inherent in the concepts of liberty and tolerance; at the same time, they ponder practical problems arising from the tensions between the forces of democracy and the destructive elements that take advantage of liberty to bring harm that undermines democracy. Written in the wake of the assasination of Yitzhak Rabin, this volume is thus dedicated to the question of boundaries: how should democracies cope with antidemocratic forces that challenge its system? How should we respond to threats that undermine democracy and at the same time retain our values and maintain our commitment to democracy and to its underlying values? All the essays here share a belief in the urgency of the need to tackle and find adequate answers to radicalism and political extremism. They cover such topics as the dilemmas embodied in the notion of tolerance, including the cost and regulation of free speech; incitement as distinct from advocacy; the challenge of religious extremism to liberal democracy; the problematics of hate speech; free communication, freedom of the media, and especially the relationships between media and terrorism. The contributors to this volume are David E. Boeyink, Harvey Chisick, Irwin Cotler, David Feldman, Owen Fiss, David Goldberg, J. Michael Jaffe, Edmund B. Lambeth, Sam Lehman-Wilzig, Joseph Eliot Magnet, Richard Moon, Frederick Schauer, and L.W. Sumner. The volume includes the opening remarks of Mrs.Yitzhak Rabin to the conference--dedicated to the late Yitzhak Rabin--at which these papers were originally presented. These studies will appeal to politicians, sociologists, media educators and professionals, jurists and lawyers, as well as the general public.

Herbert Marcuse

Repressive tolerance (full text).

| (Boston: Beacon Press, 1969), pp. 95-137. ; . by Arun Chandra, music composer and performer at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, originally posted in 2003.

|

| limited on the dual ground of legalized violence or suppression (police, armed forces, guards of all sorts) and of the privileged position held by the predominant interests and their 'connections'. society, but of the society in which man is no longer enslaved by institutions which vitiate self-determination from the beginning. In other words, freedom is still to be created even for the freest of the existing societies. And the direction in which it must be sought, and the institutional and cultural changes which may help to attain the goal are, at least in developed civilization, that is to say, they can be identified and projected, on the basis of experience, by human reason. conducive to a free and rational society, what impedes and distorts the possibilities of its creation. Freedom is liberation, a specific historical process in theory and practice, and as such it has its right and wrong, its truth and falsehood. However, this tolerance cannot be indiscriminate and equal with respect to the contents of expression, neither in word nor in deed; it cannot protect false words and wrong deeds which demonstrate that they contradict and counteract the' possibilities of liberation. Such indiscriminate tolerance is justified in harmless debates, in conversation, in academic discussion; it is indispensable in the scientific enterprise, in private religion. But society cannot be indiscriminate where the pacification of existence, where freedom and happiness themselves are at stake: here, certain things cannot be said, certain ideas cannot be expressed, certain policies cannot be proposed, certain behavior cannot be permitted without making tolerance an instrument for the continuation of servitude. The danger of 'destructive tolerance' (Baudelaire), of 'benevolent neutrality' toward has been recognized: the market, which absorbs equally well (although with often quite sudden fluctuations) art, anti-art, and non-art, all possible conflicting styles, schools, forms, provides a 'complacent receptacle, a friendly abyss'[ ] in which the radical impact of art, the protest of art against the established reality is swallowed up. However, censorship of art and literature is regressive under all circumstances. The authentic oeuvre is not and cannot be a prop of oppression, and pseudo-art (which can be such a prop) is not art. Art stands against history, withstands history which has been the history of oppression, for art subjects reality to laws other than the established ones: to the laws of the Form which creates a different reality--negation of the established one even where art depicts the established reality. But in its struggle with history, art subjects itself to history: history enters the definition of art and enters into the distinction between art and pseudo-art. Thus it happens that what was once art becomes pseudo-art. Previous forms, styles, and qualities, previous modes of protest and refusal cannot be recaptured in or against a different society. There are cases where an authentic oeuvre carries a regressive political message--Dostoevski is a case in point. But then, the message is canceled by the oeuvre itself: the regressive political content is absorbed, in the artistic form: in the work as literature. because there is no objective truth, and improvement must necessarily be a compromise between a variety of opinions, but because there an objective truth which can be discovered, ascertained only in learning and comprehending that which is and that which can be and ought to be done for the sake of improving the lot of mankind. This common and historical 'ought' is not immediately evident, at hand: it has to be uncovered by 'cutting through', 'splitting', 'breaking asunder' the given material--separating right and wrong, good and bad, correct and incorrect. The subject whose 'improvement' depends on a progressive historical practice is each man as man, and this universality is reflected in that of the discussion, which a priori does not exclude any group or individual. But even the all-inclusive character of liberalist tolerance was, at least in theory, based on the proposition that men were (potential) who could learn to hear and see and feel by themselves, to develop their own thoughts, to grasp their true interests and rights and capabilities, also against established authority and opinion. This was the rationale of free speech and assembly. Universal toleration becomes questionable when its rationale no longer prevails, when tolerance is administered to manipulated and indoctrinated individuals who parrot, as their own, the opinion of their masters, for whom heteronomy has become autonomy. triumph over persecution by virtue of its 'inherent power', which in fact has no inherent power 'against the dungeon and the stake'. And he enumerates the 'truths' which were cruelly and successfully liquidated in the dungeons and at the stake: that of Arnold of Brescia, of Fra Dolcino, of Savonarola, of the Albigensians, Waldensians, Lollards, and Hussites. Tolerance is first and foremost for the sake of the heretics--the historical road toward appears as heresy: target of persecution by the powers that be. Heresy by itself, however, is no token of truth. The underlying assumption is that the established society is free, and that any improvement, even a change in the social structure and social values, would come about in the normal course of events, prepared, defined, and tested in free and equal discussion, on the open marketplace of ideas and goods.[ ] Now in recalling John Stuart Mill's passage, I drew attention to the premise hidden in this assumption: free and equal discussion can fulfill the function attributed to it only if it is expression and development of independent thinking, free from indoctrination, manipulation, extraneous authority. The notion of pluralism and countervailing powers is no substitute for this requirement. One might in theory construct a state in which a multitude of different pressures, interests, and authorities balance each other out and result in a truly general and rational interest. However, such a construction badly fits a society in which powers are and remain unequal and even increase their unequal weight when they run their own course. It fits even worse when the variety of pressures unifies and coagulates into an overwhelming whole, integrating the particular countervailing powers by virtue of an increasing standard of living and an increasing concentration of power. Then, the laborer, whose real interest conflicts with that of management, the common consumer whose real interest conflicts with that of the producer, the intellectual whose vocation conflicts with that of his employer find themselves submitting to a system against which they are powerless and appear unreasonable. The idea of the available alternatives evaporates into an utterly utopian dimension in which it is at home, for a free society is indeed unrealistically and undefinably different from the existing ones. Under these circumstances, whatever improvement may occur 'in the normal course of events' and without subversion is likely to be an improvement in the direction determined by the particular interests which control the whole. working for peace. Peace is redefined as necessarily, in the prevailing situation, including preparation for war (or even war) and in this Orwellian form, the meaning of the word 'peace' is stabilized. Thus, the basic vocabulary of the Orwellian language operates as a priori categories of understanding: preforming all content. These conditions invalidate the logic of tolerance which involves the rational development of meaning and precludes the 'closing of meaning. Consequently, persuasion through discussion and the equal presentation of opposites (even where it is really, equal) easily lose their liberating force as factors of understanding and learning; they are far more likely to strengthen the established thesis and to repel the alternatives. of opposites, a neutralization, however, which takes place on the firm grounds of the structural limitation of tolerance and within a preformed mentality. When a magazine prints side by side a negative and a positive report on the FBI, it fulfills honestly the requirements of objectivity: however, the chances are that the positive wins because the image of the institution is deeply engraved in the mind of the people. Or, if a newscaster reports the torture and murder of civil rights workers in the same unemotional tone he uses to describe the stockmarket or the weather, or with the same great emotion with which he says his commercials, then such objectivity is spurious--more, it offends against humanity and truth by being calm where one should be enraged, by refraining from accusation where accusation is in the facts themselves. The tolerance expressed in such impartiality serves to minimize or even absolve prevailing intolerance and suppression. If objectivity has anything to do with truth, and if truth is more than a matter of logic and science, then this kind of objectivity is false, and this kind of tolerance inhuman. And if it is necessary to break the established universe of meaning (and the practice enclosed in this universe) in order to enable man to find out what is true and false, this deceptive impartiality would have to be abandoned. The people exposed to this impartiality are no they are indoctrinated by the conditions under which they live and think and which they do not transcend. To enable them to become autonomous, to find by themselves what is true and what is false for man in the existing society, they would have to be freed from the prevailing indoctrination (which is no longer recognized as indoctrination). But this means that the trend would have to be reversed: they would have to get information slanted in the opposite direction. For the facts are never given immediately and never accessible immediately; they are established, 'mediated' by those who made them; the truth, 'the whole truth' surpasses these facts and requires the rupture with their appearance. This rupture--prerequisite and token of all freedom of thought and of speech--cannot be accomplished within the established framework of abstract tolerance and spurious objectivity because these are precisely the factors which precondition the mind the rupture. by them and the consumer at large. However, it would be ridiculous to speak of a possible withdrawal of tolerance with respect to these practices and to the ideologies promoted by them. For they pertain to the basis on which the repressive affluent society rests and reproduces itself and its vital defenses - their removal would be that total revolution which this society so effectively repels. To start applying them at the point where the oppressed rebel against the oppressors, the have-nots against the haves is serving the cause of actual violence by weakening the protest against it. ] --abstraction, not from the historical possibilities, but from the realities of the prevailing societies. is not the opposite of Plato's: the liberal too demands the authority of Reason not only as an intellectual but also as a political power. In Plato, rationality is confined to the small number of philosopher-kings; in Mill, every rational human being participates in the discussion and decision--but only as a rational being. Where society has entered the phase of total administration and indoctrination, this would be a small number indeed, and not necessarily that of the elected representatives of the people. The problem is not that of an educational dictatorship, but that of breaking the tyranny of public opinion and its makers in the closed society. In contrast, the one historical change from one social system to another, marking the beginning of a new period in civilization, which was sparked and driven by an effective movement 'from below', namely, the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West, brought about a long period of regression for long centuries, until a new, higher period of civilization was painfully born in the violence of the heretic revolts of the thirteenth century and in the peasant and laborer revolts of the fourteenth century.[ ] of freedom. Where the mind has been made into a subject-object of politics and policies, intellectual autonomy, the realm of 'pure' thought has become a matter of (or rather: counter-education). the extent to which history was the development of oppression. And this oppression is in the facts themselves which it establishes; thus they themselves carry a negative value as part and aspect of their facticity. To treat the great crusades humanity (like that against the Albigensians) with the same impartiality as the desperate struggles humanity means neutralizing their opposite historical function, reconciling the executioners with their victims, distorting the record. Such spurious neutrality serves to reproduce acceptance of the dominion of the victors in the consciousness of man. Here, too, in the education of those who are not yet maturely integrated, in the mind of the young, the ground for liberating tolerance is still to be created. It isolates the individual from the one dimension where he could 'find himself': from his political existence, which is at the core of his entire existence. Instead, it encourages non-conformity and letting-go in ways which leave the real engines of repression in the society entirely intact, which even strengthen these engines by substituting the satisfactions of private, and personal rebellion for a more than private and personal, and therefore more authentic, opposition. The desublimation involved in this sort of self-actualization is itself repressive inasmuch as it weakens the necessity and the power of the intellect, the catalytic force of that unhappy consciousness which does not revel in the archetypal personal release of frustration - hopeless resurgence of the Id which will sooner or later succumb to the omnipresent rationality of the administered world - but which recognizes the horror of the whole in the most private frustration and actualizes itself in this recognition. Since they will be punished, they know the risk, and when they are willing to take it, no third person, and least of all the educator and intellectual, has the right to preach them abstention. [ ] it a majority. In its very structure this majority is 'closed', petrified; it repels a priori any change other than changes within the system. But this means that the majority is no longer justified in claiming the democratic title of the best guardian of the common interest. And such a majority is all but the opposite of Rousseau's 'general will': it is composed, not of individuals who, in their political functions, have made effective 'abstraction' from their private interests, but, on the contrary, of individuals who have effectively identified their private. interests with their political functions. And the representatives of this majority, in ascertaining and executing its will, ascertain and execute the will of the vested interests, which have formed the majority. The ideology of democracy hides its lack of substance. representation of the Left would be equalization of the prevailing inequality. Mill believed that 'individual mental superiority' justifies 'reckoning one person's opinion as equivalent to more than one': Until there shall have been devised, and until opinion is willing to accept, some mode of plural voting which may assign to education as such the degree of superior influence due to it, and sufficient as a counterpoise to the numerical weight of the least educated class, for so long the benefits of completely universal suffrage cannot be obtained without bringing with them, as it appears to me, more than equivalent evils.[ ] ] a dictatorship or elite, no matter how intellectual and intelligent, but the struggle for a real democracy. Part of this struggle is the fight against an ideology of tolerance which, in reality, favors and fortifies the conservation of the status quo of inequality and discrimination. For this struggle, I proposed the practice of discriminating tolerance. To be sure, this practice already presupposes the radical goal which it seeks to achieve. I committed this in order to combat the pernicious ideology that tolerance is already institutionalized in this society. The tolerance which is the life element, the token of a free society, will never be the gift of the powers that be; it can, under the prevailing conditions of tyranny by the majority, only be won in the sustained effort of radical minorities, willing to break this tyranny and to work for the emergence of a free and sovereign majority - minorities intolerant, militantly intolerant and disobedient to the rules of behavior which tolerate destruction and suppression. |

| [ ] (Faber, London, 1963). [ ] tolerance is indiscriminate and 'pure' even in the most democratic society The 'background limitations' stated on page [2 of this book?] restrict tolerance before it begins to operate. The antagonistic structure of society rigs the rules of the game. Those who stand against the established system are a priori at a disadvantage, which is not removed by the toleration of their ideas, speeches, and newspapers. [ ] (Maspéro, Paris, 1961). p. 22. [ ] a revolution. See Barrington Moore, (Allen Lane, London, 1963). [ ] (Chicago: Gateway Edition, 1962), p. 183. [ ] (Chicago: Gateway Edition, 1962), p. 181. [ ] |

The Freedom Writers Diary

Erin gruwell, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

| Theme Analysis |

The students at Wilson High School are used to navigating racial and ethnic divisions. The rivalry between black, Asian, and Latino gangs affect their everyday lives, constantly making them potential victims in a war where only external appearances and group loyalty matter. As a consequence, at school and in their neighborhood, students learn to remain within the confines of their own identity group. However, when Ms. Gruwell begins to teach her class about the historical consequences of ethnic violence around the world, focusing on the stories of Anne Frank in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands and Zlata Filipović in contemporary war-torn Bosnia and Herzegovina, her students are forced to confront the horrific consequences of ethnic hatred. Inspired by Anne and Zlata’s experiences, Ms. Gruwell’s students learn to see beyond the barriers of race and ethnicity, discovering that peace and tolerance are infinitely greater goals than remaining focused on people’s different identities. Ultimately, the Freedom Writers commit to focusing only on everyone’s inherent humanity, concluding that there is only one race that matters: the united human race.

The students at Wilson High School are immersed in the urban world of Long Beach, where racial tensions and a vicious gang war divide the population along ethnic and racial lines. As a result, one’s social identity and appearance determine one’s entire life, from one’s friend group to one’s chances of survival in the street. Erin Gruwell begins to teach in a historical context of racial tensions. Two years earlier, in 1992, officers in the Los Angeles Police Department were filmed brutally beating Rodney King, an unarmed black man, before arresting him. When the police officers were acquitted for this act, six days of violent rioting erupted in Los Angeles, protesting the long-standing discrimination and abuse that the African-American community has suffered from the police. This long stretch of rioting had a severe effect on increasing racial tensions in the area, and Ms. Gruwell notes that the tension could be felt in the school itself. Later events, such as California’s Proposition 187, meant to prohibit illegal immigrants from using various services in California (including health care and public education), only heightened the sense of discrimination and exclusion that many minority communities experienced at the time, in particular Asian and Latino immigrants.

Ethnic and racial communities were also in direct rivalry with each other, as African-American, Asian, and Latino gangs engaged in a ruthless war for power and territory. To remain safe, people generally stayed loyal to their own group, as one could be shot at for the mere fact of having the wrong skin color—regardless of whether or not one actually belonged to a rival gang. At Wilson High School, these divisions are strikingly visible. The school quad is divided according to color and ethnicity, as people mostly make friends with members of their own identity group.

This ethnic hatred and violence affects all students. Most of them have been shot at, have directly witnessed gang-related violence, and have seen their friends die over the course of the years due to gang rivalry. After Ms. Gruwell questions a student about the rivalry between the Latino and Asian gangs, trying to make that student realize that this war is just as senseless as that of the Capulets and Montagues in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet , the student comes to realize that Ms. Gruwell is probably right. Yet even though he cannot justify the gang’s divisions, he still abides by their logic: “[Ms. Gruwell] always tries to corner you into accepting that there’s another side, when there really isn’t. I don’t even remember how the whole thing got started, but it’s obvious that if you’re from one family, you need to be loyal and try to get some payback.”

Through Ms. Gruwell’s teaching, the students discover that racial and ethnic tensions have deep historical consequences in other places in the world. Reading the diaries of Anne Frank, who was killed in Nazi Germany for being a Jew, and of Zlata Filipović, a young girl caught in the contemporary Bosnian war, divided among nationalities and religions, allows the students to examine ethnic divisions from a distance. They come to realize that peace and tolerance are much more inspiring messages than ethnic hatred and rivalry.

When, as a student teacher, Erin Gruwell intercepts a racist caricature of an African-American boy in her class, she becomes furious and tells her students that such stereotyping is precisely what led to horrific events such as the Holocaust. She soon realizes that most of her students have never heard of the Holocaust. As a result, she decides to devote her teaching to the promotion of tolerance. When her students discover the stories of two fellow teenagers, Anne Frank and Zlata Filipović, they come to terms with the devastation that ethnic divisions can cause. During World War II, adolescent Anne Frank is forced to hide for years and is ultimately sent to a concentration camp, where she ultimately dies—all because of the mere fact that she is Jewish. In early-1990s Bosnia and Herzegovina, another young girl, Zlata, is forced to hide in a basement to escape the brutal ethnic war that is tearing her country apart. Ms. Gruwell’s students soon note similarities between their own lives and the senseless violence that these two young girls had to endure. Inspired by these young diarists’ messages of tolerance, the students become inspired to write their own diaries, chronicling their lives in a world where racial tensions and gang violence are rife.

It is when the students delve into a geographically closer past, that of the United States, that they find the inspiration to make a commitment against racial violence and injustice. They read about the Freedom Riders, a group of civil rights activists—seven black and six white—who rode a bus across the American South in the early 1960s to protest the segregation of public buses. In Alabama, the Freedom Riders were violently beaten by a mob of Ku Klux Klan members. When Ms. Gruwell’s students discover that these black and white activists were ready to sacrifice their lives to champion equal rights, they realize that they can use this episode in American history as inspiration in their own fight for diversity and tolerance. Making a pun with the original activists’ name, they decide to call themselves the “Freedom Writers.”

After long months of studying the historical consequences of racial hatred, the Freedom Riders conclude that dividing people according to their appearance or group identity is absurd and dangerous. They commit to the ideal of unity, based on the premise of recognizing everyone’s humanity. The students come to terms with the fact that separating people among racial or ethnic groups can generate injustice and harm. In Diary 33, a student recounts a time when she had to testify in court. After having seen her friend Paco kill another man, she is supposed to defend Paco and lie about his involvement in the murder, so as to defend her fellow Latino “people,” her “blood.” However, in court, she sees the despair in the eyes of the accused man’s mother—who is black—and realizes that this woman reminds her of her own Mexican mom. In this moment, she realizes that both sides of the conflict are affected by the same, senseless violence, and that protecting injustice in the name of her group identity will only tear more families apart. In a courageous move, she decides to tell the truth and accuse Paco of murder, therefore going against her presumed loyalty to Latinos in order to defend a greater ideal of justice. This decision demonstrates her commitment to recognizing everyone’s humanity and dignity, regardless of their race or identity.

However courageous and inspiring the Freedom Writers’ messages of diversity and tolerance might be, the young students often experience resistance from close-minded adults. When the Freedom Writers invite Zlata to come to the United States, she gives a speech at the Croatian Hall where she talks about her experience of ethnic hatred in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Even though she is a direct survivor of severe ethnic violence, some adults still ask her what her ethnicity is: Serbian, Croatian, Muslim? The adults’ reaction demonstrates their resistance to conceiving of the world in a color- or ethnicity-blind way. Yet Zlata boldly answers: “I am a human being” and the Freedom Writers stand by her, confirming that people’s humanity—and not their nationality, religion, or skin color—should be the only thing that ever matters. In Diary 17, a Freedom Writer reiterates this conclusion in her own words: “As long as I know that I am a human being, I don’t need to worry about what other people say. In the end, we all are the same!”

Race, Ethnicity, and Tolerance ThemeTracker

Race, Ethnicity, and Tolerance Quotes in The Freedom Writers Diary

I asked, “How many of you have heard of the Holocaust?” Not a single person raised his hand. Then I asked, “How many of you have been shot at?” Nearly every hand went up. I immediately decided to throw out my meticulously planned lessons and make tolerance the core of my curriculum. From that moment on, I would try to bring history to life by using new books, inviting guest speakers, and going on field trips.

My P.O. hasn’t realized yet that schools are just like the city and the city is just like prison. All of them are divided into separate sections, depending on race. On the streets, you kick it in different ’hoods, depending on your race, or where you’re from. And at school, we separate ourselves from people who are different from us. That’s just the way it is, and we all respect that. So when the Asians started trying to claim parts of the ’hood, we had to set them straight.

I’m not afraid of anyone anymore. Now I’m my own gang. I protect myself. I got my own back. I still carry my gun with me just in case I run into some trouble, and now I’m not afraid to use it. Running with gangs and carrying a gun can create some problems, but being of a different race can get you into trouble, too, so I figure I might as well be prepared. Lately, a lot of shit’s been going down. All I know is that I'm not gonna be the next one to get killed.

[I]t’s obvious that if you’re from a Latino gang you don’t get along with the Asian gang, and if you’re from the Asian gang, you don’t get along with the Latino gang. All this rivalry is more of a tradition. Who cares about the history behind it? Who cares about any kind of history? It’s just two sides who tripped on each other way back when and to this day make other people suffer because of their problems. Then I realized she was right, it’s exactly like that stupid play. So our reasons might be stupid, but it's still going on, and who am I to try to change things?

“Do not let Anne’s death be in vain,” Miep said, using her words to bring it all together. Miep wanted us to keep Anne’s message alive, it was up to us to remember it. Miep and Ms. Gruwell had had the same purpose all along. They wanted us to seize the moment. Ms. Gruwell wanted us to realize that we could change the way things were, and Miep wanted to take Anne’s message and share it with the world.

I have always been taught to be proud of being Latina, proud of being Mexican, and I was. I was probably more proud of being a “label” than of being a human being, that’s the way most of us were taught. Since the day we enter this world we were a label, a number, a statistic, that’s just the way it is. Now if you ask me what race I am, like Zlata, I’ll simply say, “I’m a human being.”

When I was born, the doctor must have stamped “National Spokesperson for the Plight of Black People” on my forehead; a stamp visible only to my teachers. The majority of my teachers treat me as if I, and I alone, hold the answers to the mysterious creatures that African Americans are, like I’m the Rosetta Stone of black people. It was like that until I transferred to Ms. Gruwell’s class. Up until that point it had always been: “So Joyce, how do black people feel about Affirmative Action?” Poignant looks follow. “Joyce, can you give us the black perspective on The Color Purple?”

I believe that I will never again feel uncomfortable with a person of a different race. When I have my own children someday, the custom I was taught as a child will be broken, because I know it's not right. My children will learn how special it is to bond with another person who looks different but is actually just like them. All these years I knew something was missing in my life, and I am glad that I finally found it.

As I got older, people who heard my story would ask me how I dealt with the idea of death and dying. I would think about it for a minute and reply, “See, being poor, black, and living in the ghetto was kind of like a disease that I was born with, sort of like AIDS or cancer.” It was nothing I could control.

You may opt out or contact us anytime.

Get More Zócalo

Eclectic but curated. Smart without snark. Ideas journalism with a head and heart.

Zócalo Podcasts

Why Tolerate Intolerance?

It’s easy to cancel political opponents with harmful views—it’s also dangerous to democracy.

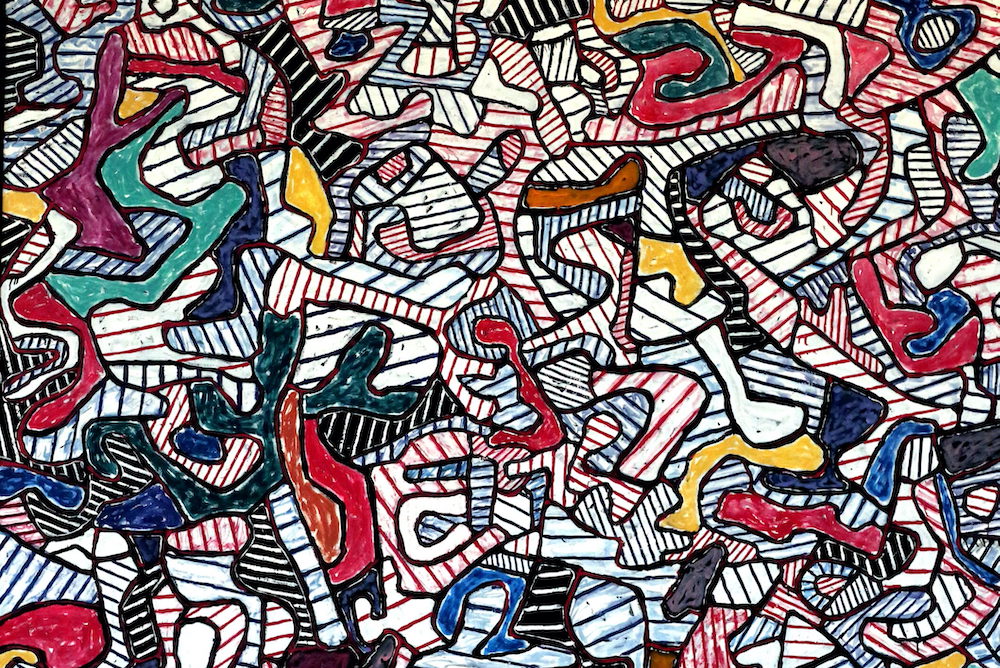

Crop of Jean Dubuffet’s “ Houle du virtuel ” (“ Swell of the Virtual” ) (1963). Courtesy of Flickr/jean louis mazieres.

by TAYLOR DOTSON | November 15, 2021

Is it better to tolerate seemingly prejudiced political opinions, or should we be intolerant of people whose views on diversity, equity, and identity strike us as harmful?

I am an advocate for radically tolerating political disagreement, even if that disagreement strikes us as unmoored from facts or common sense. One reason is that dissent makes democracy more intelligent. While many believe that vaccine skeptics misunderstand the relevant science and threaten public health, their opposition to vaccines nevertheless draws attention to chronic problems within our medical system: financial conflicts of interest, racism and sexism, and other legitimate reasons for mistrust. People should have their voices heard because politics shapes the things citizens care about , not just the things they know .

Tolerating disagreement also ensures the practice of democracy. Otherwise, we may find ourselves handing off ever more political control to experts and bureaucrats. Political truths can motivate fanaticism. Whether it is “follow the science” or “commonsense conservatism,” the belief that policy must actualize one’s own view of reality divides the world into “enlightened” good guys and ignorant enemies who just need to go away.

But what about beliefs that seem harmful and intolerant? You might question , as the political philosopher Jonathan Marks does, whether a zealous belief in the idea “that all men are created equal” is so problematic. Why not divide the political world into citizens who believe in equality and harmfully ignorant people to be ignored? The trouble is that doing so makes actually achieving equality more difficult.

Marks’ challenge to divide ourselves around equality makes me think of the great 20th century Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper’s “Paradox of Tolerance,” or at least the meme version of it. This edition of the paradox holds that tolerating the openly intolerant leads to the destruction of tolerant people and tolerance. While the meme depicts the literal Nazis, it is less clear who else it should apply to. Should it extend to dangerous misinformation from right-wing politicians?

Popper’s actual writing departs from its depiction on social media. He argued for the suppression of intolerant ideas only if those speaking them were not willing to engage in rational argument, if their followers “answer arguments by the use of their fists or pistols.” The philosopher’s tolerance was less about combating internalized prejudice than the willingness to practice democracy.

The underlying issue when it comes to tolerance in the public square is the tension between liberalism and democracy. Although liberalism is often equated with leftism, liberal philosophy is far more encompassing. Right-wing liberals champion property and business rights, while left liberals see inclusion and equal outcomes as more important.

Liberalism often conflicts with democracy, because each proposes a different way to protect rights and ensure equality. Democratic solutions seek to broaden public participation and diversify the representation of interests in the policy process, while liberalism’s answer is to protect rights by guarding them from legislative debate. The U.S. Supreme Court, for instance, is thought to be a more reliable steward of the rights of Americans to free speech, abortion, and firearms, because justices are presumed to be far wiser, more virtuous, and less “political” than voters and representatives.

Such liberal guardianship is dominant in left-wing politics. Boston University professor Ibram X. Kendi has advocated for a constitutional amendment establishing a “Department of Anti-Racism,” an expert body with the power to review and veto legislation that seems poised to exacerbate racially unequal outcomes. For instance, if new zoning laws in New York City seemed likely to decrease rates of Black homeownership, this agency could intervene to prevent their passing.

“No-platforming,” the effort to prevent controversial speakers from presenting their views, seems far removed from judicial and expert bodies, but it guards rights in a similar way. Take Charles Murray, whose book The Bell Curve partly attributed the racial achievement gap to genetic inheritance. When a student club invited him to Middlebury College in 2017, the chants and yells of protestors prevented him from publicly speaking. A group of students justified this in light of Murray’s views not merely being factually dubious but also “[denying] the basic equality” of audience members. No-platforming posits that some ideas harm people’s rights, even if not directly inciting violence or the loss of political freedoms, and that an audience knowledgeable about these harms can prevent people from speaking in order to momentarily safeguard equality.

Karl Popper would find Kendi’s proposal, no-platforming, and perhaps even the Supreme Court inconsistent with open societies. They all rely on the idea that people with certain authoritative knowledge ought to be allowed to constrain democratic practices, whether in legislatures or briefly within an auditorium. They presume that some matters are too important to be decided, or even discussed, by unenlightened citizens and their representatives.

The work of German American philosopher Herbert Marcuse offers another, more contextual way of looking at the question. He argued that “the function and value of tolerance depend on the equality prevalent in the society in which tolerance is practiced.”

Abstract tolerance is a good thing, contended Marcuse, but it falls short in practice. The first reason was that citizens are “manipulated and indoctrinated” and lack “authentic information” and the ability to think “autonomously.” The second reason was that media, educational, and other social institutions are hopelessly monopolized by conservative thought, blocking change. Because tolerance really just “[served] the cause of oppression” in the absence of equality, Marcuse advocated “new and rigid restrictions” and “the withdrawal of toleration of speech” to restore “freedom of thought.”

While there is no doubt that citizens ought to be more often challenged to rethink the status quo, Marcuse proposed an extreme version of liberal guardianship: an “educational dictatorship,” a class of people, namely Marcuse and those who agreed with him, who can think rationally and autonomously.

Despite the democratic deficits of such a regime, it is strikingly close to what we hear from establishment voices today. After all, the presumption that some people disagree only because they are misinformed, if not completely deluded, is at the core of our current political predicament. Just consider the public controversy over how schools should teach students about race. One side claims that parental concerns over the influence of “critical race theory” on education are steeped in myth and misinformation, while the other side accuses schools of peddling “indoctrination in ahistorical nonsense.”

Such statements fail to account for a very important historical fact: it has often taken civil disobedience, from groups of citizens drawing attention to a state of affairs they believe is no longer tolerable, to break the monopolistic grip of status quo thinking. Whether it is via teachers introducing challenging ideas into the classroom or via parents pushing against school boards and teachers’ unions appearing to overstep their authority, disobedience drives political change. But liberal guardianship seeks to establish new monopolies, rather than to promote productive disagreement. That’s the dynamic in media and higher education today, where “no-platforming” is aimed at out-of-fashion political thought.

Still, no-platforming is appealing in part because political progress in addressing inequality is so frustratingly slow. Charles Murray’s racial ideas rightfully feel menacing, because they might justify even less representation of Black people in politics and higher education . Liberal guardianship looks attractive when democracy is dysfunctional, as a way to compensate for the persistence of social inequalities, not to mention ineffectual governance. Perhaps those shouting down their opponents hope that loudly opposing problematic utterances within social media and on college campuses will lead to chronic diversity issues finally being resolved. But it hasn’t worked that way.

We are seeing, right now, that liberal “thought guardianship” leads to a winnowing in the range of acceptable opinions. Each side becomes fanaticized around their own notion of justice, and public conversation becomes narrowly focused on policing the boundaries of heresy. The problem of institutions falling short of realizing equal treatment gets blurred with the issue of too many citizens thinking and saying the wrong things.

The political philosopher Robert Talisse, a Vanderbilt professor, articulates a similar concern. A consequence of ongoing political polarization is people’s partisan identities becoming core to their sense of self. In turn, they demand more conformity of belief from friends and allies.

One could call this “intolerance creep.” Efforts that begin with no-platforming more obvious opponents of equality like Charles Murray later target potential allies. For instance, geoscience professor Dorian Abbot’s recent disinvitation from speaking at MIT was not because he opposed addressing diversity problems at universities but because he believes that affirmative action is the wrong tool to use.

One problem with intolerance creep is that a range of views on equality are compatible with democracy. Philosophical debates about equality of opportunity, outcomes, status, and capabilities have persisted for centuries, with no signs of forthcoming agreement. But when citizens embrace their own version as Truth, partial allies become political enemies. The variegated, “big tent” coalitions that traditionally helped to end harmful and discriminatory politics are rendered impossible. Polarized politics leads to gridlock, not victory.

How can we avoid intolerance creep? Consider the starkly polarized debate over trans rights. Progressives’ political goal seems clear: equal treatment. Yet the conversation is dominated by ontological claims. “Trans men are men” and “Trans women are women,” insists the ACLU when issues like restroom access arise, while opponents chant “sex is real” in response. Each side is only further fanaticized by the belief that “science” vindicates their own position, as if we could just get citizens to accept certain facts, certain truths , then the thorny policy disagreements will disappear.

Some parts of the debate are not spectacularly complicated, even if they are contentious. For instance, which currently sex-segregated spaces should allow trans people entrance without intrusive forms of questioning? In other cases, discerning equal treatment is less clear-cut. Controversy over sports participation and hormone treatments for minors are beset with overlapping dilemmas and trade-offs concerning autonomy and fairness, largely obscured by competing ontological claims. For instance, a “sex realist” approach gets natal women kicked out of the Olympics, while extending transition rights to teens would mean being willing to use governmental authority to revoke parental custody. Again, politics is a matter of caring, not knowing.

This might seem like a pedantic distinction, but it’s important. As Popper wrote, “‘Equality before the law’ is not a fact but a political demand based upon a moral decision , and it is quite independent of the theory—which is probably false—that ‘all men are born equal.’” Citizens need not believe anything specific about the nature of equality or that transwomen are women. They only need to be willing to listen to people’s reasons for caring about an issue, to share their own experiences, and to make policy compromises and concessions. And studies of political canvassing show that this kind of democratic talk actually works for trans rights issues.

This looked to be the approach Nancy Kelley hoped to take when appointed chief executive of Stonewall, the LGBTQ+ human rights organization. “We don’t have to convert everybody to our way of understanding gender,” Kelley said in an interview, “for the experience of trans people’s lives to be more positive, and for them to have lower levels of hate crime, better access to health services and more inclusive schools and workplaces, we don’t need people to agree on what constitutes womanhood.”

A society that tolerates political disagreement invariably tolerates some risk of harmfully intolerant beliefs. But dissent isn’t just some abstract democratic value. As a buffer against intolerance creep, it helps ensure progress against harmful policies. We tolerate some of the opinions that strike us as distasteful because it pays off later.

So, we should resist the impulse to demand conformity in order to compensate for current democratic deficiencies. People whose speech directly promotes or inspires violence should be prevented from entering politics, but extending that intolerance to those who simply see equality differently deprives us of potential allies. As uncomfortable as it may be to talk to people whose beliefs fall short of our own, it is a discomfort that I hope more of us can learn to live with.

Send A Letter To the Editors

Please tell us your thoughts. Include your name and daytime phone number, and a link to the article you’re responding to. We may edit your letter for length and clarity and publish it on our site.

(Optional) Attach an image to your letter. Jpeg, PNG or GIF accepted, 1MB maximum.

By continuing to use our website, you agree to our privacy and cookie policy . Zócalo wants to hear from you. Please take our survey !-->

No paywall. No ads. No partisan hacks. Ideas journalism with a head and a heart.

Explaining the Paradox of Tolerance

An essential element of a democratic society is the universal tolerance of all political perspectives. Through tolerance, interactions between the multitude of perspectives within the spectrum take place. Democracy is the product of these interactions being expressed at the ballot.

It is because of tolerance that political ideas can coexist and that no one perspective is held sacred. Citizens are free to form opinions and vote based on those opinions. However there exists a concept that has become increasingly relevant in the past decade, the idea that universal tolerance is dangerous.

In his influential work The Open Society and Its Enemie s, Karl Popper posited a self-contradictory idea known as the ‘paradox of tolerance.’ This concept holds that a tolerant society should not have unlimited tolerance. The reason for this contradiction is that unlimited tolerance implies the toleration of those who are intolerant.

He argues that without tolerance limits, those who are intolerant will work with impunity to subvert those whom they consider to be the ‘other.’ If these intolerant ideas are allowed to exist and eventually spread, they will bring about the dissolution of the tolerant society from within.

It is a paradox because a tolerant society must fortify against intolerance by being tolerant. Popper states “We should claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant. Furthermore, he says intolerant ideas should be “placed outside of the law,” in other words, certain ideas should be made illegal.

Currently, there exists a debate along this line of thinking. Should democratic societies allow for intolerant and anti-democratic ideas to persist, despite their implied protection under the democratic principle of tolerance?

It has long been understood that there is a political spectrum and that at either side of that spectrum lies extreme political ideologies. Both of these ends of the spectrum include intolerant ideas. The extreme right generally is intolerant of modernist ideas like egalitarianism and multiculturalism. The extreme left is generally intolerant of traditionalism, nationalism and hierarchical structures.

Antifa serves as an example of the manifestation of Popper's thought. It is a far-left organized political movement that looks to prevent the spread of intolerant racist and neo-fascist ideologies. These ideas are detested by Antifa based on their intolerance and potential for violence. Passively denouncing or exposing these ideas as falsifiable, bigoted and unsophisticated is not enough–as that allows the ideology to persist and continue its intolerant bigotry. Instead, Antifa kinetically persecutes those who hold intolerant beliefs. Put simply, Antifa does not tolerate ideas that are perceived as intolerant and seeks to eradicate them by force.

Political extremes are defined by their distance from the center. While extreme ideas are not favored by the majority of citizens due to their deviation from the norm, they exist because of the right to hold any opinion and the principle of universal tolerance. To counter intolerant extremism and protect a tolerant society, Popper suggests overriding the democratic principle of universal tolerance.

- Expl - Politics

Recent Posts

The "Civil War" Movie

Explaining the $95 Billion in Foreign Aid

Antigua and Barbuda-Mainland China Deal

Wayne Price

Free speech, democracy, and “repressive tolerance” the use of herbert marcuse to justify left suppression of free speech.

Herbert Marcuse’s Opposition to “Tolerance”

Marcuse’s Reasons for Rejecting Toleranc e

Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Analysis

The Benefits of Free Speech and Tolerance for the Left

What About Fascism?

What Are We For?