- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

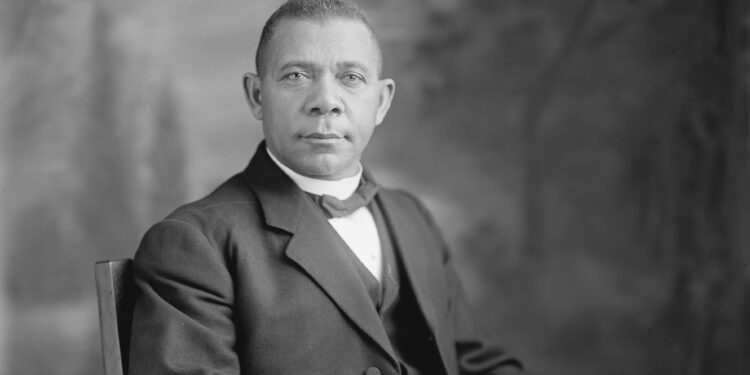

Booker T. Washington

By: History.com Editors

Updated: December 18, 2023 | Original: October 29, 2009

Booker T. Washington (1856-1915) was born into slavery and rose to become a leading African American intellectual of the 19 century, founding Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (Now Tuskegee University) in 1881 and the National Negro Business League two decades later. Washington advised Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. His infamous conflicts with Black leaders like W. E. B. Du Bois over segregation caused a stir, but today, he is remembered as the most influential African American speaker of his time.

Booker T. Washington’s Parents and Early Life

Booker Taliaferro Washington was born on April 5, 1856 in a hut in Franklin County, Virginia . His mother was a cook for the plantation’s owner. His father, a white man, was unknown to Washington. At the close of the Civil War , all the enslaved people owned by James and Elizabeth Burroughs—including 9-year-old Booker, his siblings, and his mother—were freed. Jane moved her family to Malden, West Virginia. Soon after, she married Washington Ferguson, a free Black man.

Booker T. Washington’s Education

In Malden, Washington was only allowed to go to school after working from 4-9 AM each morning in a local salt works before class. It was at a second job in a local coalmine where he first heard two fellow workers discuss the Hampton Institute, a school for formerly enslaved people in southeastern Virginia founded in 1868 by Brigadier General Samuel Chapman. Chapman had been a leader of Black troops for the Union during the Civil War and was dedicated to improving educational opportunities for African Americans.

In 1872, Washington walked the 500 miles to Hampton, where he was an excellent student and received high grades. He went on to study at Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C., but had so impressed Chapman that he was invited to return to Hampton as a teacher in 1879. It was Chapman who would refer Washington for a role as principal of a new school for African Americans in Tuskegee, Alabama : The Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, today’s Tuskegee University. Washington assumed the role in 1881 at age 25 and would work at The Tuskegee Institute until his death in 1915.

It was Washington who hired George Washington Carver to teach agriculture at Tuskegee in 1896. Carver would go on to be a celebrated figure in Black history in his own right, making huge advances in botany and farming technology.

Booker T. Washington Beliefs And Rivalry with W.E.B. Du Bois

Life in the post- Reconstruction era South was challenging for Black people. Discrimination was rife in the age of Jim Crow Laws . Exercising the right to vote under the 15 Amendment was dangerous, and access to jobs and education was severely limited. With the dawn of the Ku Klux Klan , the threat of retaliatory violence for advocating for civil rights was real.

In perhaps his most famous speech, given on September 18, 1895, Washington told a majority white audience in Atlanta that the way forward for African Americans was self-improvement through an attempt to “dignify and glorify common labor.” He felt it was better to remain separate from whites than to attempt desegregation as long as whites granted their Black countrymen and women access to economic progress, education, and justice under U.S. courts:

"The wisest of my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than artificial forcing. The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than to spend a dollar in an opera house."

His speech was sharply criticized by W.E.B. Du Bois , who repudiated what he called “The Atlanta Compromise” in a chapter of his famous 1903 book, “The Souls of Black Folk.” Opposition to Washington’s views on race inspired the Niagara Movement (1905-1909). Du Bois would go on to found the NAACP in 1909.

Because of Washington’s outsized stature in the Black community, dissenting views were strongly squashed. Du Bois and others criticized Washington’s harsh treatment of rival Black newspapers and Black thinkers who dared to challenge his opinions and authority.

Books By Booker T. Washington

Washington, a famed public speaker known for his sense of humor , was also the author of five books:

· “The Story of My Life and Work” (1900)

· “Up From Slavery” (1901)

· “The Story of the Negro: The Rise of the Race from Slavery” (1909)

· “My Larger Education” (1911)

· “The Man Farthest Down” (1912)

Booker T. Washington: First African American in the White House

Booker T. Washington became the first African American to be invited to the White House in 1901, when President Theodore Roosevelt invited him to dine with him. It caused a huge uproar among white Americans—especially in the Jim Crow South—and in the press, and came on the heels of the publication of his autobiography, “Up From Slavery.” But Roosevelt saw Washington as a brilliant advisor on racial matters, a practice his successor, President William Howard Taft , continued.

Booker T. Washington Death And Legacy

Booker T. Washington’s legacy is complex. While he lived through an epic sea change in the lives of African Americans, his public views supporting segregation seem outdated today. His emphasis on economic self-determination over political and civil rights fell out of favor as the views of his largest critic, W.E.B. Du Bois, took root and inspired the civil rights movement . We now know that Washington secretly financed court cases that challenged segregation and wrote letters in code to defend against lynch mobs. His work in the field of education helped give access to new hope for thousands of African Americans.

By 1913, at the dawn of the administration of Woodrow Wilson , Washington had largely fallen out of favor. He remained at the Tuskegee Institute until congestive heart failure ended his life on November 14, 1915. He was 59.

Washington left behind a vastly improved Tuskegee Institute with over 1,500 students, a faculty of 200 and an endowment of nearly $2 million to continue to carry on its work.

Booker T. Washington. Biography.com The Debate Between W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. Frontline . Jim Crow Stories: Booker T. Washington. Thirteen.org. Booker T. Washington. Britannica .

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

"Of Booker T. Washington and Others," from The Souls of Black Folk

- Civil Rights Movement

- Race and Equality

- Social Reform

No study questions

No related resources

Source: Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. “Of Booker T. Washington and Others,” in The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches , 41-59. United States: A. C. McClurg & Company, 1903. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Souls_of_Black_Folk/7psUAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 .

From birth till death enslaved; in word, in deed, unmanned! Hereditary bondsmen! Know ye not Who would be free themselves must strike the blow? BYRON.

EASILY the most striking thing in the history of the American Negro since 1876 is the ascendancy of Mr. Booker T. Washington. It began at the time when war memories and ideals were rapidly passing; a day of astonishing commercial development was dawning; a sense of doubt and hesitation overtook the freedmen's sons,—then it was that his leading began. Mr. Washington came, with a simple definite programme, at the psychological moment when the nation was a little ashamed of having bestowed so much sentiment on Negroes, and was concentrating its energies on Dollars. His programme of industrial education, conciliation of the South, and submission and silence as to civil and political rights, was not wholly original; the Free Negroes from 1830 up to war-time had striven to build industrial schools, and the American Missionary Association had from the first taught various trades; and Price and others had sought a way of honorable alliance with the best of the Southerners. But Mr. Washington first indissolubly linked these things; he put enthusiasm, unlimited energy, and perfect faith into his programme, and changed it from a by-path into a veritable Way of Life. And the tale of the methods by which he did this is a fascinating study of human life.

It startled the nation to hear a Negro advocating such a programme after many decades of bitter complaint; it startled and won the applause of the South, it interested and won the admiration of the North; and after a confused murmur of protest, it silenced if it did not convert the Negroes themselves.

To gain the sympathy and coöperation of the various elements comprising the white South was Mr. Washington's first task; and this, at the time Tuskegee was founded, seemed, for a black man, well-nigh impossible. And yet ten years later it was done in the word spoken at Atlanta: "In all things purely social we can be as separate as the five fingers, and yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress ." This "Atlanta Compromise" is by all odds the most notable thing in Mr. Washington's career. The South interpreted it in different ways: the radicals received it as a complete surrender of the demand for civil and political equality; the conservatives, as a generously conceived working basis for mutual understanding. So both approved it, and to-day its author is certainly the most distinguished Southerner since Jefferson Davis, and the one with the largest personal following.

Next to this achievement comes Mr. Washington's work in gaining place and consideration in the North. Others less shrewd and tactful had formerly essayed to sit on these two stools and had fallen between them; but as Mr. Washington knew the heart of the South from birth and training, so by singular insight he intuitively grasped the spirit of the age which was dominating the North. And so thoroughly did he learn the speech and thought of triumphant commercialism, and the ideals of material prosperity, that the picture of a lone black boy poring over a French grammar amid the weeds and dirt of a neglected home soon seemed to him the acme of absurdities. One wonders what Socrates and St. Francis of Assisi would say to this.

And yet this very singleness of vision and thorough oneness with his age is a mark of the successful man. It is as though Nature must needs make men narrow in order to give them force. So Mr. Washington's cult has gained unquestioning followers, his work has wonderfully prospered, his friends are legion, and his enemies are confounded. To-day he stands as the one recognized spokesman of his ten million fellows, and one of the most notable figures in a nation of seventy millions. One hesitates, therefore, to criticise a life which, beginning with so little, has done so much. And yet the time is come when one may speak in all sincerity and utter courtesy of the mistakes and shortcomings of Mr. Washington's career, as well as of his triumphs, without being thought captious or envious, and without forgetting that it is easier to do ill than well in the world.

The criticism that has hitherto met Mr. Washington has not always been of this broad character. In the South especially has he had to walk warily to avoid the harshest judgments,—and naturally so, for he is dealing with the one subject of deepest sensitiveness to that section. Twice—once when at the Chicago celebration of the Spanish-American War he alluded to the color-prejudice that is "eating away the vitals of the South," and once when he dined with President Roosevelt—has the resulting Southern criticism been violent enough to threaten seriously his popularity. In the North the feeling has several times forced itself into words, that Mr. Washington's counsels of submission overlooked certain elements of true manhood, and that his educational programme was unnecessarily narrow. Usually, however, such criticism has not found open expression, although, too, the spiritual sons of the Abolitionists have not been prepared to acknowledge that the schools founded before Tuskegee, by men of broad ideals and self-sacrificing spirit, were wholly failures or worthy of ridicule. While, then, criticism has not failed to follow Mr. Washington, yet the prevailing public opinion of the land has been but too willing to deliver the solution of a wearisome problem into his hands, and say, "If that is all you and your race ask, take it."

Among his own people, however, Mr. Washington has encountered the strongest and most lasting opposition, amounting at times to bitterness, and even to-day continuing strong and insistent even though largely silenced in outward expression by the public opinion of the nation. Some of this opposition is, of course, mere envy; the disappointment of displaced demagogues and the spite of narrow minds. But aside from this, there is among educated and thoughtful colored men in all parts of the land a feeling of deep regret, sorrow, and apprehension at the wide currency and ascendancy which some of Mr. Washington's theories have gained. These same men admire his sincerity of purpose, and are willing to forgive much to honest endeavor which is doing something worth the doing. They coöperate with Mr. Washington as far as they conscientiously can; and, indeed, it is no ordinary tribute to this man's tact and power that, steering as he must between so many diverse interests and opinions, he so largely retains the respect of all.

But the hushing of the criticism of honest opponents is a dangerous thing. It leads some of the best of the critics to unfortunate silence and paralysis of effort, and others to burst into speech so passionately and intemperately as to lose listeners. Honest and earnest criticism from those whose interests are most nearly touched,—criticism of writers by readers, of government by those governed, of leaders by those led,—this is the soul of democracy and the safeguard of modern society. If the best of the American Negroes receive by outer pressure a leader whom they had not recognized before, manifestly there is here a certain palpable gain. Yet there is also irreparable loss,—a loss of that peculiarly valuable education which a group receives when by search and criticism it finds and commissions its own leaders. The way in which this is done is at once the most elementary and the nicest problem of social growth. History is but the record of such group-leadership; and yet how infinitely changeful is its type and character! And of all types and kinds, what can be more instructive than the leadership of a group within a group?—that curious double movement where real progress may be negative and actual advance be relative retrogression. All this is the social student's inspiration and despair.

Now in the past the American Negro has had instructive experience in the choosing of group leaders, founding thus a peculiar dynasty which in the light of present conditions is worth while studying. When sticks and stones and beasts form the sole environment of a people, their attitude is largely one of determined opposition to and conquest of natural forces. But when to earth and brute is added an environment of men and ideas, then the attitude of the imprisoned group may take three main forms,—a feeling of revolt and revenge; an attempt to adjust all thought and action to the will of the greater group; or, finally, a determined effort at self-realization and self-development despite environing opinion. The influence of all of these attitudes at various times can be traced in the history of the American Negro, and in the evolution of his successive leaders.

Before 1750, while the fire of African freedom still burned in the veins of the slaves, there was in all leadership or attempted leadership but the one motive of revolt and revenge,—typified in the terrible Maroons, the Danish blacks, and Cato of Stono, and veiling all the Americas in fear of insurrection. The liberalizing tendencies of the latter half of the eighteenth century brought, along with kindlier relations between black and white, thoughts of ultimate adjustment and assimilation. Such aspiration was especially voiced in the earnest songs of Phyllis, in the martyrdom of Attucks, the fighting of Salem and Poor, the intellectual accomplishments of Banneker and Derham, and the political demands of the Cuffes.

Stern financial and social stress after the war cooled much of the previous humanitarian ardor. The disappointment and impatience of the Negroes at the persistence of slavery and serfdom voiced itself in two movements. The slaves in the South, aroused undoubtedly by vague rumors of the Haytian revolt, made three fierce attempts at insurrection,—in 1800 under Gabriel in Virginia, in 1822 under Vesey in Carolina, and in 1831 again in Virginia under the terrible Nat Turner. In the Free States, on the other hand, a new and curious attempt at self-development was made. In Philadelphia and New York color-prescription led to a withdrawal of Negro communicants from white churches and the formation of a peculiar socio-religious institution among the Negroes known as the African Church,—an organization still living and controlling in its various branches over a million of men.

Walker's wild appeal against the trend of the times showed how the world was changing after the coming of the cotton-gin. By 1830 slavery seemed hopelessly fastened on the South, and the slaves thoroughly cowed into submission. The free Negroes of the North, inspired by the mulatto immigrants from the West Indies, began to change the basis of their demands; they recognized the slavery of slaves, but insisted that they themselves were freemen, and sought assimilation and amalgamation with the nation on the same terms with other men. Thus, Forten and Purvis of Philadelphia, Shad of Wilmington, Du Bois of New Haven, Barbadoes of Boston, and others, strove singly and together as men, they said, not as slaves; as "people of color," not as "Negroes." The trend of the times, however, refused them recognition save in individual and exceptional cases, considered them as one with all the despised blacks, and they soon found themselves striving to keep even the rights they formerly had of voting and working and moving as freemen. Schemes of migration and colonization arose among them; but these they refused to entertain, and they eventually turned to the Abolition movement as a final refuge.

Here, led by Remond, Nell, Wells-Brown, and Douglass, a new period of self-assertion and self-development dawned. To be sure, ultimate freedom and assimilation was the ideal before the leaders, but the assertion of the manhood rights of the Negro by himself was the main reliance, and John Brown's raid was the extreme of its logic. After the war and emancipation, the great form of Frederick Douglass, the greatest of American Negro leaders, still led the host. Self-assertion, especially in political lines, was the main programme, and behind Douglass came Elliot, Bruce, and Langston, and the Reconstruction politicians, and, less conspicuous but of greater social significance, Alexander Crummell and Bishop Daniel Payne.

Then came the Revolution of 1876, the suppression of the Negro votes, the changing and shifting of ideals, and the seeking of new lights in the great night. Douglass, in his old age, still bravely stood for the ideals of his early manhood,—ultimate assimilation through self-assertion, and on no other terms. For a time Price arose as a new leader, destined, it seemed, not to give up, but to re-state the old ideals in a form less repugnant to the white South. But he passed away in his prime. Then came the new leader. Nearly all the former ones had become leaders by the silent suffrage of their fellows, had sought to lead their own people alone, and were usually, save Douglass, little known outside their race. But Booker T. Washington arose as essentially the leader not of one race but of two,—a compromiser between the South, the North, and the Negro. Naturally the Negroes resented, at first bitterly, signs of compromise which surrendered their civil and political rights, even though this was to be exchanged for larger chances of economic development. The rich and dominating North, however, was not only weary of the race problem, but was investing largely in Southern enterprises, and welcomed any method of peaceful coöperation. Thus, by national opinion, the Negroes began to recognize Mr. Washington's leadership; and the voice of criticism was hushed.

Mr. Washington represents in Negro thought the old attitude of adjustment and submission; but adjustment at such a peculiar time as to make his programme unique. This is an age of unusual economic development, and Mr. Washington's programme naturally takes an economic cast, becoming a gospel of Work and Money to such an extent as apparently almost completely to overshadow the higher aims of life. Moreover, this is an age when the more advanced races are coming in closer contact with the less developed races, and the race-feeling is therefore intensified; and Mr. Washington's programme practically accepts the alleged inferiority of the Negro races. Again, in our own land, the reaction from the sentiment of war time has given impetus to race-prejudice against Negroes, and Mr. Washington withdraws many of the high demands of Negroes as men and American citizens. In other periods of intensified prejudice all the Negro's tendency to self-assertion has been called forth; at this period a policy of submission is advocated. In the history of nearly all other races and peoples the doctrine preached at such crises has been that manly self-respect is worth more than lands and houses, and that a people who voluntarily surrender such respect, or cease striving for it, are not worth civilizing.

In answer to this, it has been claimed that the Negro can survive only through submission. Mr. Washington distinctly asks that black people give up, at least for the present, three things,—

First, political power,

Second, insistence on civil rights,

Third, higher education of Negro youth,—and concentrate all their energies on industrial education, and accumulation of wealth, and the conciliation of the South. This policy has been courageously and insistently advocated for over fifteen years, and has been triumphant for perhaps ten years. As a result of this tender of the palm-branch, what has been the return? In these years there have occurred:

1. The disfranchisement of the Negro.

2. The legal creation of a distinct status of civil inferiority for the Negro.

3. The steady withdrawal of aid from institutions for the higher training of the Negro.

These movements are not, to be sure, direct results of Mr. Washington's teachings; but his propaganda has, without a shadow of doubt, helped their speedier accomplishment. The question then comes: Is it possible, and probable, that nine millions of men can make effective progress in economic lines if they are deprived of political rights, made a servile caste, and allowed only the most meagre chance for developing their exceptional men? If history and reason give any distinct answer to these questions, it is an emphatic No . And Mr. Washington thus faces the triple paradox of his career:

1. He is striving nobly to make Negro artisans business men and property-owners; but it is utterly impossible, under modern competitive methods, for workingmen and property- owners to defend their rights and exist without the right of suffrage.

2. He insists on thrift and self-respect, but at the same time counsels a silent submission to civic inferiority such as is bound to sap the manhood of any race in the long run.

3. He advocates common-school and industrial training, and depreciates institutions of higher learning; but neither the Negro common-schools, nor Tuskegee itself, could remain open a day were it not for teachers trained in Negro colleges, or trained by their graduates.

This triple paradox in Mr. Washington's position is the object of criticism by two classes of colored Americans. One class is spiritually descended from Toussaint the Savior, through Gabriel, Vesey, and Turner, and they represent the attitude of revolt and revenge; they hate the white South blindly and distrust the white race generally, and so far as they agree on definite action, think that the Negro's only hope lies in emigration beyond the borders of the United States. And yet, by the irony of fate, nothing has more effectually made this programme seem hopeless than the recent course of the United States toward weaker and darker peoples in the West Indies, Hawaii, and the Philippines,—for where in the world may we go and be safe from lying and brute force?

The other class of Negroes who cannot agree with Mr. Washington has hitherto said little aloud. They deprecate the sight of scattered counsels, of internal disagreement; and especially they dislike making their just criticism of a useful and earnest man an excuse for a general discharge of venom from small-minded opponents. Nevertheless, the questions involved are so fundamental and serious that it is difficult to see how men like the Grimkes, Kelly Miller, J. W. E. Bowen, and other representatives of this group, can much longer be silent. Such men feel in conscience bound to ask of this nation three things:

1. The right to vote.

2. Civic equality.

3. The education of youth according to ability.

They acknowledge Mr. Washington's invaluable service in counselling patience and courtesy in such demands; they do not ask that ignorant black men vote when ignorant whites are debarred, or that any reasonable restrictions in the suffrage should not be applied; they know that the low social level of the mass of the race is responsible for much discrimination against it, but they also know, and the nation knows, that relentless color-prejudice is more often a cause than a result of the Negro's degradation; they seek the abatement of this relic of barbarism, and not its systematic encouragement and pampering by all agencies of social power from the Associated Press to the Church of Christ. They advocate, with Mr. Washington, a broad system of Negro common schools supplemented by thorough industrial training; but they are surprised that a man of Mr. Washington's insight cannot see that no such educational system ever has rested or can rest on any other basis than that of the well-equipped college and university, and they insist that there is a demand for a few such institutions throughout the South to train the best of the Negro youth as teachers, professional men, and leaders.

This group of men honor Mr. Washington for his attitude of conciliation toward the white South; they accept the "Atlanta Compromise" in its broadest interpretation; they recognize, with him, many signs of promise, many men of high purpose and fair judgment, in this section; they know that no easy task has been laid upon a region already tottering under heavy burdens. But, nevertheless, they insist that the way to truth and right lies in straightforward honesty, not in indiscriminate flattery; in praising those of the South who do well and criticizing uncompromisingly those who do ill; in taking advantage of the opportunities at hand and urging their fellows to do the same, but at the same time in remembering that only a firm adherence to their higher ideals and aspirations will ever keep those ideals within the realm of possibility. They do not expect that the free right to vote, to enjoy civic rights, and to be educated, will come in a moment; they do not expect to see the bias and prejudices of years disappear at the blast of a trumpet; but they are absolutely certain that the way for a people to gain their reasonable rights is not by voluntarily throwing them away and insisting that they do not want them; that the way for a people to gain respect is not by continually belittling and ridiculing themselves; that, on the contrary, Negroes must insist continually, in season and out of season, that voting is necessary to modern manhood, that color discrimination is barbarism, and that black boys need education as well as white boys.

In failing thus to state plainly and unequivocally the legitimate demands of their people, even at the cost of opposing an honored leader, the thinking classes of American Negroes would shirk a heavy responsibility,—a responsibility to themselves, a responsibility to the struggling masses, a responsibility to the darker races of men whose future depends so largely on this American experiment, but especially a responsibility to this nation,—this common Fatherland. It is wrong to encourage a man or a people in evil-doing; it is wrong to aid and abet a national crime simply because it is unpopular not to do so. The growing spirit of kindliness and reconciliation between the North and South after the frightful differences of a generation ago ought to be a source of deep congratulation to all, and especially to those whose mistreatment caused the war; but if that reconciliation is to be marked by the industrial slavery and civic death of those same black men, with permanent legislation into a position of inferiority, then those black men, if they are really men, are called upon by every consideration of patriotism and loyalty to oppose such a course by all civilized methods, even though such opposition involves disagreement with Mr. Booker T. Washington. We have no right to sit silently by while the inevitable seeds are sown for a harvest of disaster to our children, black and white.

First, it is the duty of black men to judge the South discriminatingly. The present generation of Southerners are not responsible for the past, and they should not be blindly hated or blamed for it. Furthermore, to no class is the indiscriminate endorsement of the recent course of the South toward Negroes more nauseating than to the best thought of the South. The South is not "solid"; it is a land in the ferment of social change, wherein forces of all kinds are fighting for supremacy; and to praise the ill the South is to-day perpetrating is just as wrong as to condemn the good. Discriminating and broad-minded criticism is what the South needs,—needs it for the sake of her own white sons and daughters, and for the insurance of robust, healthy mental and moral development.

To-day even the attitude of the Southern whites toward the blacks is not, as so many assume, in all cases the same; the ignorant Southerner hates the Negro, the workingmen fear his competition, the money-makers wish to use him as a laborer, some of the educated see a menace in his upward development, while others—usually the sons of the masters—wish to help him to rise. National opinion has enabled this last class to maintain the Negro common schools, and to protect the Negro partially in property, life, and limb. Through the pressure of the money-makers, the Negro is in danger of being reduced to semi-slavery, especially in the country districts; the workingmen, and those of the educated who fear the Negro, have united to disfranchise him, and some have urged his deportation; while the passions of the ignorant are easily aroused to lynch and abuse any black man. To praise this intricate whirl of thought and prejudice is nonsense; to inveigh indiscriminately against "the South" is unjust; but to use the same breath in praising Governor Aycock, exposing Senator Morgan, arguing with Mr. Thomas Nelson Page, and denouncing Senator Ben Tillman, is not only sane, but the imperative duty of thinking black men.

It would be unjust to Mr. Washington not to acknowledge that in several instances he has opposed movements in the South which were unjust to the Negro; he sent memorials to the Louisiana and Alabama constitutional conventions, he has spoken against lynching, and in other ways has openly or silently set his influence against sinister schemes and unfortunate happenings. Notwithstanding this, it is equally true to assert that on the whole the distinct impression left by Mr. Washington's propaganda is, first, that the South is justified in its present attitude toward the Negro because of the Negro's degradation; secondly, that the prime cause of the Negro's failure to rise more quickly is his wrong education in the past; and, thirdly, that his future rise depends primarily on his own efforts. Each of these propositions is a dangerous half-truth. The supplementary truths must never be lost sight of: first, slavery and race-prejudice are potent if not sufficient causes of the Negro's position; second, industrial and common-school training were necessarily slow in planting because they had to await the black teachers trained by higher institutions,—it being extremely doubtful if any essentially different development was possible, and certainly a Tuskegee was unthinkable before 1880; and, third, while it is a great truth to say that the Negro must strive and strive mightily to help himself, it is equally true that unless his striving be not simply seconded, but rather aroused and encouraged, by the initiative of the richer and wiser environing group, he cannot hope for great success.

In his failure to realize and impress this last point, Mr. Washington is especially to be criticised. His doctrine has tended to make the whites, North and South, shift the burden of the Negro problem to the Negro's shoulders and stand aside as critical and rather pessimistic spectators; when in fact the burden belongs to the nation, and the hands of none of us are clean if we bend not our energies to righting these great wrongs.

The South ought to be led, by candid and honest criticism, to assert her better self and do her full duty to the race she has cruelly wronged and is still wronging. The North—her co-partner in guilt—cannot salve her conscience by plastering it with gold. We cannot settle this problem by diplomacy and suaveness, by "policy" alone. If worse come to worst, can the moral fibre of this country survive the slow throttling and murder of nine millions of men?

The black men of America have a duty to perform, a duty stern and delicate,—a forward movement to oppose a part of the work of their greatest leader. So far as Mr. Washington preaches Thrift, Patience, and Industrial Training for the masses, we must hold up his hands and strive with him, rejoicing in his honors and glorying in the strength of this Joshua called of God and of man to lead the headless host. But so far as Mr. Washington apologizes for injustice, North or South, does not rightly value the privilege and duty of voting, belittles the emasculating effects of caste distinctions, and opposes the higher training and ambition of our brighter minds,—so far as he, the South, or the Nation, does this,—we must unceasingly and firmly oppose them. By every civilized and peaceful method we must strive for the rights which the world accords to men, clinging unwaveringly to those great words which the sons of the Fathers would fain forget: "We hold these truths to be self-evident: That all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

Of Our Spiritual Strivings

Of the training of black men, see our list of programs.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

Check out our collection of primary source readers

Our Core Document Collection allows students to read history in the words of those who made it. Available in hard copy and for download.

The ROTUNDA DIGITAL EDITION includes the full contents of the 14-volume letterpress edition, including speeches, correspondence, major autobiographical writing, and cumulative index.

The Booker T. Washington Papers Digital Edition The University of Virginia Press Copyright © 2021 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All content deriving from the letterpress edition, The Booker T. Washington Papers , © 1972–1989 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois; reproduced by permission.

ISBN: 978-0-8139-4752-5

Images: Booker T. Washington, crop of photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston from the Library of Congress; 1946 commemorative half-dollar, photo courtesy of Raymond Smock.

Copyright policy · Privacy policy · Feedback and support

Rotunda editions were established by generous grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the President’s Office of the University of Virginia

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Booker T. Washington in perspective : essays of Louis R. Harlan

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

87 Previews

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station12.cebu on February 17, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- Education & Teaching

- Schools & Teaching

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Booker T. Washington in Perspective: Essays of Louis R. Harlan Hardcover – January 1, 1989

Written over a span of a quarter of a century, they present a remarkably rich and complex look at Washington, the educator and leading precursor of the Civil Rights Movement who rose from slavery to be the dominant force in black America at the opening of the twentieth century.

Harlan's mastery of biography is revealed in essays printed here exploring the nature of biographical writing. Readers interested in the art of historiography and biography will find here Harlan's essays detailing his experience in crafting his acclaimed biography of Washington, which received two Bancroft Awards, the Beveridge Award, and the Pulitzer Prize.

Booker T. Washington in Perspective reveals Harlan as historian and biographer in the essays that were the prelude to his masterwork.

- Language English

- Publisher Univ Pr of Mississippi

- Publication date January 1, 1989

- Dimensions 6.5 x 0.75 x 9.25 inches

- ISBN-10 0878053743

- ISBN-13 978-0878053742

- Lexile measure 1480L

- See all details

Product details

- Publisher : Univ Pr of Mississippi; First Edition (January 1, 1989)

- Language : English

- ISBN-10 : 0878053743

- ISBN-13 : 978-0878053742

- Lexile measure : 1480L

- Item Weight : 1.2 pounds

- Dimensions : 6.5 x 0.75 x 9.25 inches

About the author

Louis r. harlan.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

No customer reviews

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- English Literature

- Short Stories

- Literary Terms

- Web Stories

Booker T. Washington a Pioneer of Education and Literary Influence

Table of Contents

What did Booker T. Washington influence?, What was Booker T. Washington education?, What was Booker T. Washington’s literary work?,Booker Taliaferro Washington occupies a significant place in American history, renowned for his relentless efforts in advancing African American education and societal progress. Beyond his pivotal role in shaping the socio-political landscape, Washington made substantial contributions to American literature through his writings, speeches, and autobiographical works. This essay delves into the life, influences, and literary legacy of Booker T. Washington, shedding light on his enduring impact on education and literature in the United States.

Early Life and Formative Years

Born into slavery on April 5, 1856, in Hale’s Ford, Virginia, Washington experienced the harsh realities of bondage during his formative years. The Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 marked a turning point, providing him with the opportunity to pursue an education. Washington’s determination and commitment to learning became apparent during the post-war years, laying the foundation for his later advocacy of education as a catalyst for empowerment.

Educational Pursuits and Influences

- Charles Waddell Chesnutt is a famous American Novelist

- Willa Cather is Shaping American Literature through Novels

- James Weldon Johnson is a Literary Luminary in American Poetry

Founding Tuskegee Institute

In 1881, Washington assumed leadership at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Alabama, marking a pivotal moment in his career. His vision for Tuskegee went beyond mere academics; it embraced a holistic approach to education, addressing the economic and social upliftment of African Americans. Through Tuskegee, Washington sought to equip students with practical skills and instill in them the values of industry and self-sufficiency.

Literary Contributions

1. “Up from Slavery” (1901):

2. Speeches and Writings:

Washington emerged as a prolific writer and speaker, addressing diverse audiences across the nation. His speeches, articles, and essays often emphasized themes of self-help, industrial education, and racial upliftment. Notable addresses, including the Atlanta Compromise speech in 1895, reflected his pragmatic approach to race relations, urging African Americans to focus on economic advancement through education and skills.

3. “The Future of the American Negro” (1899):

This collection of essays further exemplifies Washington’s thoughts on the future of African Americans in the United States. He advocated for a patient and gradual approach to social and economic progress, emphasizing the importance of practical education and economic self-sufficiency.

Literary Style and Rhetorical Techniques

1. Accessible Language:

Washington’s literary style is characterized by its accessibility. Whether in his autobiography or speeches, he employed straightforward and relatable language that resonated with a broad audience. This accessibility contributed to the widespread dissemination of his ideas and principles.

Washington skillfully employed rhetorical appeals, particularly ethos and pathos, in his writings and speeches. By drawing on his personal experiences and emphasizing the transformative power of education, he sought to establish credibility and evoke emotional responses from his audience.

3. Pragmatic Tone:

The pragmatic tone in Washington’s writings reflected his practical approach to problem-solving. He focused on actionable steps, advocating for economic self-improvement and the acquisition of practical skills as key components of racial progress.

Criticism and Controversies

While Washington’s contributions to American literature and education are widely acknowledged, his accommodationist stance and the Atlanta Compromise speech sparked debates within the African American community. Critics, including W. E. B. Du Bois, argued that Washington’s emphasis on vocational training perpetuated social inequality and limited the pursuit of higher education and civil rights.

Legacy and Impact

1. Educational Legacy:

Washington’s most enduring legacy lies in his contributions to African American education. Tuskegee Institute, under his leadership, became a model for industrial education, empowering generations of African Americans with practical skills and a strong work ethic.

2. Literary Legacy:

Washington’s literary contributions, particularly “Up from Slavery,” remain influential in the study of African American literature. His writings offer valuable insights into the challenges faced by African Americans in the post-Civil War era and the transformative potential of education.

3. Impact on Civil Rights Movement:

While criticized for his accommodationist stance, Washington’s influence extended to the early phases of the Civil Rights Movement. His emphasis on economic empowerment and education laid the groundwork for subsequent leaders and movements that sought to address racial inequalities in American society.

4. Continued Relevance:

Washington’s ideas on education, self-help, and economic empowerment continue to be relevant today. His emphasis on practical skills and self-sufficiency resonates in discussions on education and economic advancement within marginalized communities.

Booker T. Washington’s legacy is woven into the fabric of American history, marked by his unwavering dedication to African American education and his influential literary contributions. Born into slavery, Washington’s transformative journey from bondage to becoming a prominent figure is chronicled in his seminal work, “Up from Slavery.” His commitment to practical education and economic empowerment at the Tuskegee Institute laid the foundation for generations of African Americans.

His educational legacy endures through Tuskegee Institute, which continues to empower individuals with practical skills. In the realm of literature, Washington’s autobiographical narrative serves as a significant historical document and a source of inspiration for those advocating for equality and education.

As we reflect on Booker T. Washington’s contributions, his ideas on self-help, economic empowerment, and practical education remain relevant in contemporary discussions on societal progress. His enduring impact underscores the ongoing pursuit of a more inclusive and equitable society.

1. What was Booker T. Washington’s most significant literary work?

Booker T. Washington’s most significant literary work is “Up from Slavery” (1901), his autobiography. This seminal work chronicles his life, from slavery to prominence, and serves as a cornerstone in African American literature, providing valuable insights into the post-Civil War era.

2. How did Booker T. Washington contribute to African American education?

Booker T. Washington made significant contributions to African American education by founding and leading the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. His emphasis on practical skills and economic self-sufficiency empowered generations of African Americans, providing them with the tools for success.

3. What was the Atlanta Compromise speech, and why was it significant?

The Atlanta Compromise speech (1895) was a pivotal address by Booker T. Washington. In it, he advocated for racial cooperation and economic self-improvement for African Americans. While criticized by some for its accommodationist tone, the speech reflected Washington’s pragmatic approach to addressing racial disparities.

4. How did Booker T. Washington’s literary style contribute to his influence?

Washington’s literary style, characterized by accessible language and a pragmatic tone, contributed to his wide influence. His writings, including speeches and essays, resonated with diverse audiences, making his ideas and principles more accessible to a broad spectrum of readers.

Related Posts

Washington Irving developing a American Fictional Prose

Henry David Thoreau is Shaping American Literature

Nathaniel Hawthorne is Shaping the Landscape of American Literature

Attempt a critical appreciation of The Triumph of Life by P.B. Shelley.

Consider The Garden by Andrew Marvell as a didactic poem.

Why does Plato want the artists to be kept away from the ideal state

MEG 05 LITERARY CRITICISM & THEORY Solved Assignment 2023-24

William Shakespeare Biography and Works

Discuss the theme of freedom in Frederick Douglass’ Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

How does William Shakespeare use the concept of power in Richard III

Analyze the use of imagery in William Shakespeare’s sonnets

Which australian poet wrote “the love song of j. alfred prufrock”, what is the premise of “the book thief” by markus zusak, who is the author of “gould’s book of fish”, name an australian author known for their young adult fiction.

- Advertisement

- Privacy & Policy

- Other Links

© 2023 Literopedia

Welcome Back!

Login to your account below

Remember Me

Retrieve your password

Please enter your username or email address to reset your password.

Are you sure want to unlock this post?

Are you sure want to cancel subscription.

Booker T. Washington and His Ideas

Introduction, social darwinism and faith in the fairness of the free market, the impact on the place of blacks in society, the origin and credibility of washington’s ideas, the success of washington’s approach to black advancement.

Booker T. Washington was one of the most influential leaders of ethnic minorities in the United States of the nineteenth century. He was also a researcher who proposed a row of practical actions to resolve the issues of these population groups, mostly of economic nature (Tozer et al., 2020). Therefore, this activist’s suggestions were distinct from other proposals regarding the matter by the orientation of specific measures, which should be taken to improve the lives of African American citizens (Washington, 2018). Hence, this paper aims to consider his ideas related to the problems of Blacks, their origin and impact on their place in society, as well as the outcome of this leader’s activity.

The development of Washington’s thought had several directions, which represented his position regarding the methods of establishing a reasonable quality of life for all people. The first consideration was the concept of Social Darwinism he learned when attending Hampton, which applies to societal and economic aspects of human activity and means the survival of the most capable members of society (Tozer et al., 2020). However, it did not correlate with the circumstances of Blacks’ lives, and the political initiatives were not useful for ensuring their development. From Washington’s perspective, the principal area, which should be covered by the policy intended to help these people, was industrial education intended to provide them with opportunities for material prosperity (Washington, 2018). In this way, he emphasized the importance of economic security and vocational skills in contrast to politics.

His opinion was underpinned by the considerations of the fairness of the free market in business as a principal circumstance leading to African Americans’ future prosperity. Thus, Washington claimed that their acceptance by white people is possible only in the case if they are economical, not politically, equal (Tozer et al., 2020). This perspective allowed the leader to prove the importance for Blacks to work and acquire new skills instead of attempting to be more active in the political arena.

The perceptions of Washington regarding the predominant role of economic factors not only shaped his views but also significantly affected the intention of African Americans to find their place in society. Their influence was conditional upon the fact that representatives of this population group did not have any efficient means to improve their situation at the time (Washington, 2018). On the contrary, most Black leaders were trying to attract public attention to their problems without suggesting any practical ways to solve them and gain equality (Tozer et al., 2020). From this point of view, the economic considerations of Washington based on the concept of Social Darwinism and his belief in the fairness of the free market were transmitted to Blacks. They demonstrated the appropriate course of action leading to improvements in quality of life.

The ideas of Booker T. Washington originated from his personal experience, and this fact adds credibility to them. Being born as a slave and further emancipated, he faced the challenge of the need to take responsibility for the future since freedom implied the ability to provide for himself (Washington, 2018). Washington noticed that Blacks did not possess the skills allowing them to survive in the world of white men. In his opinion, this situation could be explained by the lack of understanding of economic processes and, therefore, participation in them (Tozer et al., 2020). Nevertheless, despite the apparent logic of such thinking, his judgment seems to be naïve from the psychological perspective. The active participation of African Americans in business affairs resembles a utopia since the white population was unwilling to deal with them.

The approach of Booker T. Washington to Black advancement was quite successful in terms of initiating their economic involvement. However, his goals underlying the foundation of the National Negro Business League were not fully met (Washington, 2018). Thus, for example, the initiative to build a network of African American entrepreneurs was hindered by the civil rights movement, which came to the fore (Tozer et al., 2020). In this way, the attention of representatives of this ethnic group was focused on the actions for establishing equality rather than material prosperity as an indirect method to achieve this objective (Washington, 2018). Nevertheless, the economic movement started with the implementation of Washington’s ideas and marked the beginning of Black’s progress in this area.

To summarize, the political thought of Booker T. Washington based on the concept of Social Darwinism and the free market contributing to the improvement of the quality of life of African Americans had positive results. It allowed promoting their economic rights as a principal condition of future equality with the white population and, therefore, finding their place in society. The origin of Washington’s ideas related to his personal experience and struggles adds to the reasonability of his initiatives regarding the Blacks’ participation in business. Even though his perceptions were naïve from the perspective of all citizens’ acceptance of their intervention in this field, it can be concluded that they still significantly affected their wellbeing. Thus, Black advancement was a successful endeavor in terms of promoting the rights of African Americans throughout the country.

Tozer, S., Senese, G., & Violas, P. (2020). School and society: Historical and contemporary perspectives (8 th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Washington, B. T. (2018). The future of the American Negro. Outlook Verlag GmbH.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, March 9). Booker T. Washington and His Ideas. https://studycorgi.com/booker-t-washington-and-his-ideas/

"Booker T. Washington and His Ideas." StudyCorgi , 9 Mar. 2022, studycorgi.com/booker-t-washington-and-his-ideas/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) 'Booker T. Washington and His Ideas'. 9 March.

1. StudyCorgi . "Booker T. Washington and His Ideas." March 9, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/booker-t-washington-and-his-ideas/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Booker T. Washington and His Ideas." March 9, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/booker-t-washington-and-his-ideas/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "Booker T. Washington and His Ideas." March 9, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/booker-t-washington-and-his-ideas/.

This paper, “Booker T. Washington and His Ideas”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: May 23, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Biography : Booker T. Washington

How it works

‘’He was born in Franklin County, Virginia. His father was a white slave owner and his mother was a black slave. He grew up and studied under physical labor. At the age of sixteen, he came to the Normal and Agricultural College in Hampton, Virginia, for teacher training. He was appointed president of a college. He also received two master’s degrees. Booker Taliaferro Washington is an American politician, educator and writer. He was one of the most important figures in black American history between 1890 and 1915.

’’(Angelique) ‘’He made an important role in this time, and had an extraordinary influence. He has his own beliefs. He has great opinions on the issue of racial discrimination. He also discussed this issue in public speeches. Because he made a very important role, he was invited to dinner at the White House. He was the first African American to win an honor.’’(Mark)

- 1 Personal background

- 2 History Context

- 4 Obstacles

- 5 Accomplishments

- 6 Long –term Significance

- 7 Conclusion

Personal background

He is politically active, and many political leaders in the United States consult him on black issues. He works with many white politicians and celebrities. He believes that the most effective way for black people to achieve equal rights is to show the virtues of patience, diligence and thrift. He says these are the keys to improving the living standards of black Americans. IN 1895, Booker T. Washington publicly put forth his philosophy on race relations in a speech at the Cotton States, the main point of his speech was that whites could regain their civil rights and social status as long as they were allowed to receive improvements in economic education and fair treatment. ‘’This speech caused a part of the rise, because it made many people feel that they had been treated unfairly, mainly in the north, and finally led to rigid isolation and discrimination patterns throughout the South and the country institutionalized.’’ (Walker, Clarence E)

History Context

‘’Born into a slave family, he had little hope of living in Washington. Like most states before the Civil War, slave children would become slaves. His mother is the cook of planter James. His father, an unknown white man, was sent to the factory when he was very young. He was beaten up for his unsatisfactory work in transporting grain. Once he saw people of his age reading books, so he wanted to do the same, but he was a slave and it was illegal to teach slaves to read. ‘’(Alex)After the end of the civil war. He and his mother moved to West Virginia, where he learned to read and write, and he worked hard every day, after which he decided to talk about his unfair treatment. After that, his speech was very successful and caused a sensation. After this incident, because of his great influence, he was invited to dinner at the White House.

Buck Washington believes that as long as black people possess knowledge, property and good moral character, they will naturally have their due civil rights. So blacks don’t have to agitate or fight against racial discrimination and apartheid. ‘’He believed that the social order of racial discrimination and apartheid was disrupted. It pays for nothing. He warned blacks not to let them know what they want to do. Every part of the United States, like every other part of the world, has its own “customs” and it is wise to respect them.

He put forward the political thought of taking self-help as the core, temporarily abandoning the pursuit of political rights as the premise, prospering the black economy as the foundation, developing black industrial education as the means, and aiming at racial integration. He demanded that the black race ultimately acquire every beauty endowed by the American Constitution through hard work, frugal lifestyle, down-to-earth working attitude and the shaping of Christian personality. The rights of citizens of a country. He practiced physically, founded Tessie Black Teachers College under extremely difficult circumstances, and went around to publicize his views on black struggle and to practice his political thoughts with practical actions, which had a far-reaching impact on the development of the Afro-American Movement after the reconstruction.‘’? Smokey, Robinson?‘’ At the end of 19th century and the beginning of 20th century, in American society, racial relations were bad, white superiors were in power, and black struggle was very complicated.

In this special historical environment, Buck T. Washington did not follow the traditional political struggle line, but did the opposite. He called on black races to abandon the pursuit of political rights and social equality for the time being, to avoid bloody struggle, and to devote themselves to the economic construction of black people. Efforts should be made to improve their moral quality and develop black industrial education. ‘’?Hall Association in Philadelphia?

‘’Booker Washington believes that the development of Vocational and technical education is the cornerstone of the plan to solve the problem of blacks. He believed that blacks in the South had no culture and technology, were extremely poor, and were at the bottom of the economic world. Therefore, it was necessary to teach them PR He placed his full hopes on his vocational and technical education plan and the pure economic line, calling on blacks to temporarily renounce all rights, including the right to vote. In his view, blacks blindly devoted themselves to politics during the reconstruction period, instead of praying for their own economic conditions, and as a result became tools of political struggle, neglecting the “fundamental problem of self-improvement”. Tactical skills through vocational and technical education to make a living and achieve self-reliance. ‘’ (PARK CLOSURES)

Abandoning the legitimate demands of blacks as human beings and American citizens is tantamount to accepting blacks ‘view of racial inferiority.

Point. ‘’He pointed out that although eliminating racial discrimination and obtaining equal rights is a long-term task, blacks should never voluntarily renounce their civil rights, on the contrary, they should persevere in fighting for their rights and fighting against racial discrimination. He said that all the great reform movements and social movements in history were led by encouragement.’’ (Smokey, Robinson)

I think this problem is a matter of principle, or a matter of bottom line. The abolition of slavery in 1865, that is, the legal denial of the existence of slavery is reasonable, the former black slaves are now free people. According to the definition of citizen, “citizen” refers to a person who has the nationality of a country and enjoys rights and obligations according to the law of that country. Citizen consciousness is relative to subject consciousness, which refers to people’s participation consciousness in society and state governance in a country.

Civil political rights refer to citizens ‘rights to participate in the political life of the country according to law. At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the rampant racism in the United States, the growing tension between black and white races and the deterioration of the black situation made Du Bois gradually realize that his limited research on some aspects of the black problem could not cope with the critical moments of black history. He also recognized that Buck Washington’s advice to blacks to give up agitation, to acquiesce in racial discrimination and segregation, to stay away from politics and to immerse themselves in business, made white racists more arrogant and made the situation of blacks worse.

‘’So in 1903, Du Bois published the book The Soul of the Black, which openly challenged Booker Washington. Since then, besides continuing to emphasize the efforts of the black people themselves, he advocated that the black people should stand up and actively encourage them to fight for the equal rights of the black people in politics and society.

Booker-Washington kept silent about the white people’s responsibility for blacks, emphasizing blacks ‘own problems. He said that the backwardness in education and economic poverty of blacks did not make them eligible for civil rights. Likewise, his hope for solving the problem of blacks was mainly placed on blacks. “Everyone, every race, must save themselves,” he said. Du Bois, like Buck Washington, recognizes that the low level of social development of black people is a cause of racial discrimination, but he also emphasizes that racial discrimination is more a cause than a result of the backwardness of black economy and culture. He pointed out that if blacks were poor, it was because they deprived themselves of the fruits of their labor; if blacks were ignorant, it was because white people obstructed the education of blacks. Therefore, Du Bois believes that in order to solve the problem of black Americans, black people should strive to eliminate their own problems, while white people are more responsible for the problem of black Americans. He criticized Buck Washington for putting all the blacks ‘responsibilities on their shoulders.’’ (Hall Association in Philadelphia)

Accomplishments

‘’Between 1980 and 1915, Washington played a very important role in black politics. Washington’s famous speech in Atlanta in 1895 made him famous throughout the country as a black leader of political and public concern. Working with white people, he raised money to create hundreds of community schools and institutions of higher education to improve the education of blacks. Washington has improved racial relations in the United States. His autobiography Beyond Slavery, first published in 1901, is the bedside book of President Barack Obama and is still widely circulated today. ‘’(Alex) And he developed into Tuskegee College. Tuskegee provided academic education and knowledge for teachers, but also a large number of practical technical education for black youth.

Running schools is Washington’s ambition. ‘’He believed that providing practical technical education for black youth would enable blacks to occupy a place in society and gain recognition from white Americans. He believed that when the blacks showed that they were responsible and reliable people, they would be able to get all the civil rights. He was the principal of the school until his death in 1915. He succeeded in giving black people equal education, improving their status and self-cultivation. So he realized a large part of his ideal. After that, he praised his contribution to American society. In 1946, the United States coined the first commemorative coin with a black Washington head. On April 7, 1940, Washington became the first African American to appear on American stamps.’’(Angelique)

Long –term Significance

He put forward the political thought of taking self-help as the core, temporarily abandoning the pursuit of political rights as the premise, prospering the black economy as the foundation, developing black industrial education as the means, and aiming at racial integration. He demanded that the black race ultimately acquire every beauty endowed by the American Constitution through hard work, frugal lifestyle, down-to-earth working attitude and the shaping of Christian personality. (Walker, Clarence E). The rights of citizens of a country. ‘’He practiced physically, founded Talkie Black Teachers College under extremely difficult circumstances, and went around to publicize his views on black struggle and to practice his political thoughts with practical actions, which had a far-reaching impact on the development of the Afro-American Movement after the reconstruction. (Robert J. Norrell.)

His political thought has a far-reaching impact on the black movement in the United States. It is of great significance to understand the black movement in the United States as a whole and to explore the way out for the black people by analyzing the historical background of his political thought formation, deeply analyzing its basic content and peeping into its influence on the black movement, the development of the black people themselves, the black politics, economy and education after the Civil War. So his thoughts have played a vital role for the present.’’ (Michael Rudolph)

Booker T. Washington’s political thought has a far-reaching impact on the black movement in the United States. It is of great significance to understand the black movement in the United States as a whole and to explore the way out for the black people by exploring the historical background of his political thought formation, deeply analyzing its basic content and peering into its influence on the black movement, the development of the black people themselves, the black politics, economy and education after the Civil War. His educational thought is based on the needs of the development of the black race and bears the obvious brand of the times. He tried to achieve the self-help and development of the black race through vocational education, and help the black people to acquire the accumulation of economic basis and improve their comprehensive quality. The emphasis on the application of knowledge, practice and the connection with social life in his educational thoughts embodied the characteristics of the times in the development of American education at that time.

Cite this page

Biography : Booker T. Washington. (2019, Aug 01). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/biography-booker-t-washington/

"Biography : Booker T. Washington." PapersOwl.com , 1 Aug 2019, https://papersowl.com/examples/biography-booker-t-washington/

PapersOwl.com. (2019). Biography : Booker T. Washington . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/biography-booker-t-washington/ [Accessed: 12 May. 2024]

"Biography : Booker T. Washington." PapersOwl.com, Aug 01, 2019. Accessed May 12, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/biography-booker-t-washington/

"Biography : Booker T. Washington," PapersOwl.com , 01-Aug-2019. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/biography-booker-t-washington/. [Accessed: 12-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2019). Biography : Booker T. Washington . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/biography-booker-t-washington/ [Accessed: 12-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Web Dubois — Compare And Contrast Booker T Washington And Dubois

Compare and Contrast Booker T Washington and Dubois

- Categories: Web Dubois

About this sample

Words: 742 |

Published: Mar 5, 2024

Words: 742 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Booker t. washington, w.e.b. du bois, comparison and criticisms, contributions and conclusion, washington's emphasis on vocational education, du bois's advocacy for higher education and political rights.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1725 words

4.5 pages / 1980 words

2 pages / 887 words

3.5 pages / 2123 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Web Dubois

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, two prominent African American leaders, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois, emerged as key figures in the fight for racial equality. While both individuals sought to empower [...]

Immediately following the Civil War, African Americans were faced with great discrimination and suffering. The newly free slaves were faced with the problem of making their stance in society that once looked at them as nothing [...]

W.E.B. Du Bois, an African American scholar and activist, penned the seminal work "The Souls of Black Folk" in the late 19th century. This masterpiece delves into the complex issues surrounding slavery, labor struggles, [...]

Booker T. Washington focused on having education for real life jobs and not asking for equality from the whites. He just focused on getting help from the whites and accepting their place as blacks on earth. WEB Dubois focused on [...]

The life and career of W.E.B Dubois was vastly multi-faceted and prolific, and his scope of talents and global citizenship encompasses various disciplines. “While his contributions to civil rights, sociology, history, African [...]

W.E.B Du Bois is one of the renowned scholars in the field of history, civil rights activism and above all, sociology. There is an interesting story of his life, deep-rooted in his well-spent years of success in the career of [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?