How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2020

- Volume 36 , pages 909–913, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Clara Busse ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0178-1000 1 &

- Ella August ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036 1 , 2

266k Accesses

15 Citations

705 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

Sascha Kraus, Matthias Breier, … João J. Ferreira

Plagiarism in research

Gert Helgesson & Stefan Eriksson

Open peer review: promoting transparency in open science

Dietmar Wolfram, Peiling Wang, … Hyoungjoo Park

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

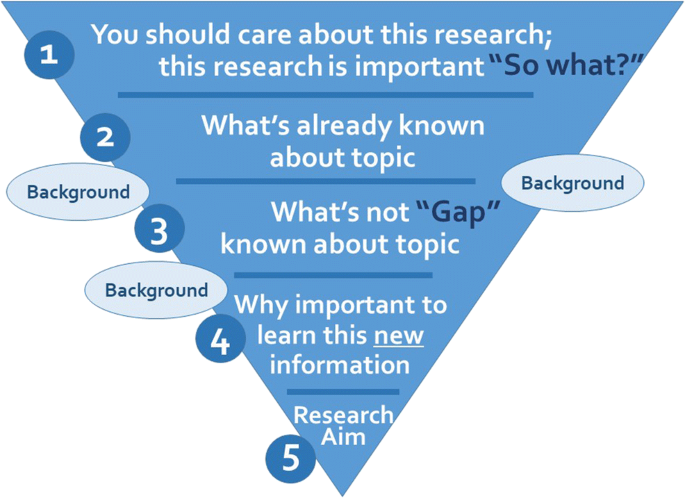

Structure of the Introduction Section

The introduction section should be approximately three to five paragraphs in length. Look at examples from your target journal to decide the appropriate length. This section should include the elements shown in Fig. 1 . Begin with a general context, narrowing to the specific focus of the paper. Include five main elements: why your research is important, what is already known about the topic, the “gap” or what is not yet known about the topic, why it is important to learn the new information that your research adds, and the specific research aim(s) that your paper addresses. Your research aim should address the gap you identified. Be sure to add enough background information to enable readers to understand your study. Table 1 provides common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

The main elements of the introduction section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Methods Section

The purpose of the methods section is twofold: to explain how the study was done in enough detail to enable its replication and to provide enough contextual detail to enable readers to understand and interpret the results. In general, the essential elements of a methods section are the following: a description of the setting and participants, the study design and timing, the recruitment and sampling, the data collection process, the dataset, the dependent and independent variables, the covariates, the analytic approach for each research objective, and the ethical approval. The hallmark of an exemplary methods section is the justification of why each method was used. Table 2 provides common methods section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Results Section

The focus of the results section should be associations, or lack thereof, rather than statistical tests. Two considerations should guide your writing here. First, the results should present answers to each part of the research aim. Second, return to the methods section to ensure that the analysis and variables for each result have been explained.

Begin the results section by describing the number of participants in the final sample and details such as the number who were approached to participate, the proportion who were eligible and who enrolled, and the number of participants who dropped out. The next part of the results should describe the participant characteristics. After that, you may organize your results by the aim or by putting the most exciting results first. Do not forget to report your non-significant associations. These are still findings.

Tables and figures capture the reader’s attention and efficiently communicate your main findings [ 3 ]. Each table and figure should have a clear message and should complement, rather than repeat, the text. Tables and figures should communicate all salient details necessary for a reader to understand the findings without consulting the text. Include information on comparisons and tests, as well as information about the sample and timing of the study in the title, legend, or in a footnote. Note that figures are often more visually interesting than tables, so if it is feasible to make a figure, make a figure. To avoid confusing the reader, either avoid abbreviations in tables and figures, or define them in a footnote. Note that there should not be citations in the results section and you should not interpret results here. Table 3 provides common results section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Discussion Section

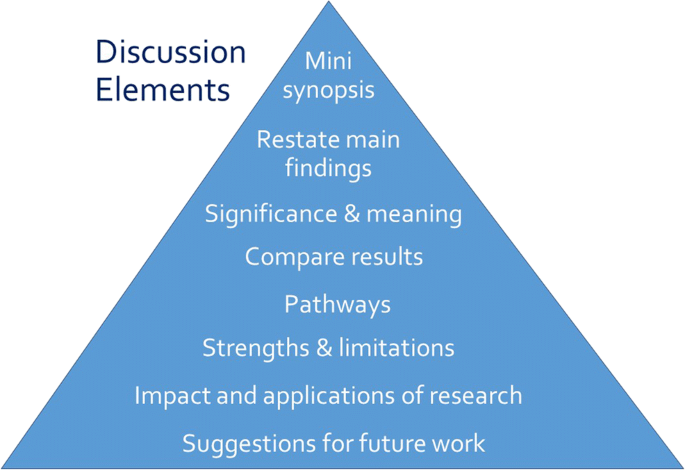

Opposite the introduction section, the discussion should take the form of a right-side-up triangle beginning with interpretation of your results and moving to general implications (Fig. 2 ). This section typically begins with a restatement of the main findings, which can usually be accomplished with a few carefully-crafted sentences.

Major elements of the discussion section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Next, interpret the meaning or explain the significance of your results, lifting the reader’s gaze from the study’s specific findings to more general applications. Then, compare these study findings with other research. Are these findings in agreement or disagreement with those from other studies? Does this study impart additional nuance to well-accepted theories? Situate your findings within the broader context of scientific literature, then explain the pathways or mechanisms that might give rise to, or explain, the results.

Journals vary in their approach to strengths and limitations sections: some are embedded paragraphs within the discussion section, while some mandate separate section headings. Keep in mind that every study has strengths and limitations. Candidly reporting yours helps readers to correctly interpret your research findings.

The next element of the discussion is a summary of the potential impacts and applications of the research. Should these results be used to optimally design an intervention? Does the work have implications for clinical protocols or public policy? These considerations will help the reader to further grasp the possible impacts of the presented work.

Finally, the discussion should conclude with specific suggestions for future work. Here, you have an opportunity to illuminate specific gaps in the literature that compel further study. Avoid the phrase “future research is necessary” because the recommendation is too general to be helpful to readers. Instead, provide substantive and specific recommendations for future studies. Table 4 provides common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Follow the Journal’s Author Guidelines

After you select a target journal, identify the journal’s author guidelines to guide the formatting of your manuscript and references. Author guidelines will often (but not always) include instructions for titles, cover letters, and other components of a manuscript submission. Read the guidelines carefully. If you do not follow the guidelines, your article will be sent back to you.

Finally, do not submit your paper to more than one journal at a time. Even if this is not explicitly stated in the author guidelines of your target journal, it is considered inappropriate and unprofessional.

Your title should invite readers to continue reading beyond the first page [ 4 , 5 ]. It should be informative and interesting. Consider describing the independent and dependent variables, the population and setting, the study design, the timing, and even the main result in your title. Because the focus of the paper can change as you write and revise, we recommend you wait until you have finished writing your paper before composing the title.

Be sure that the title is useful for potential readers searching for your topic. The keywords you select should complement those in your title to maximize the likelihood that a researcher will find your paper through a database search. Avoid using abbreviations in your title unless they are very well known, such as SNP, because it is more likely that someone will use a complete word rather than an abbreviation as a search term to help readers find your paper.

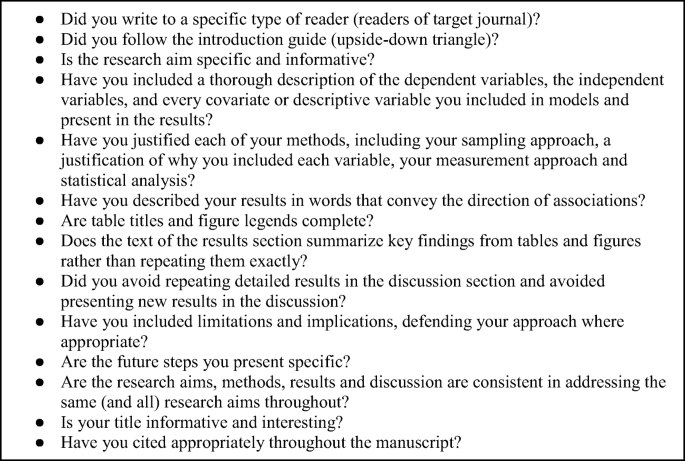

After you have written a complete draft, use the checklist (Fig. 3 ) below to guide your revisions and editing. Additional resources are available on writing the abstract and citing references [ 5 ]. When you feel that your work is ready, ask a trusted colleague or two to read the work and provide informal feedback. The box below provides a checklist that summarizes the key points offered in this article.

Checklist for manuscript quality

Data Availability

Michalek AM (2014) Down the rabbit hole…advice to reviewers. J Cancer Educ 29:4–5

Article Google Scholar

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Defining the role of authors and contributors: who is an author? http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authosrs-and-contributors.html . Accessed 15 January, 2020

Vetto JT (2014) Short and sweet: a short course on concise medical writing. J Cancer Educ 29(1):194–195

Brett M, Kording K (2017) Ten simple rules for structuring papers. PLoS ComputBiol. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619

Lang TA (2017) Writing a better research article. J Public Health Emerg. https://doi.org/10.21037/jphe.2017.11.06

Download references

Acknowledgments

Ella August is grateful to the Sustainable Sciences Institute for mentoring her in training researchers on writing and publishing their research.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Clara Busse & Ella August

Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109-2029, USA

Ella August

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ella August .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 362 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Busse, C., August, E. How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal. J Canc Educ 36 , 909–913 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Download citation

Published : 30 April 2020

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Manuscripts

- Scientific writing

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER BRIEF

- 08 May 2019

Toolkit: How to write a great paper

A clear format will ensure that your research paper is understood by your readers. Follow:

1. Context — your introduction

2. Content — your results

3. Conclusion — your discussion

Plan your paper carefully and decide where each point will sit within the framework before you begin writing.

Collection: Careers toolkit

Straightforward writing

Scientific writing should always aim to be A, B and C: Accurate, Brief, and Clear. Never choose a long word when a short one will do. Use simple language to communicate your results. Always aim to distill your message down into the simplest sentence possible.

Choose a title

A carefully conceived title will communicate the single core message of your research paper. It should be D, E, F: Declarative, Engaging and Focused.

Conclusions

Add a sentence or two at the end of your concluding statement that sets out your plans for further research. What is next for you or others working in your field?

Find out more

See additional information .

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01362-9

Related Articles

How to get published in high impact journals

So you’re writing a paper

Writing for a Nature journal

How I harnessed media engagement to supercharge my research career

Career Column 09 APR 24

Ready or not, AI is coming to science education — and students have opinions

Career Feature 08 APR 24

How we landed job interviews for professorships straight out of our PhD programmes

Career Column 08 APR 24

Brazil’s postgraduate funding model is about rectifying past inequalities

Correspondence 09 APR 24

Declining postdoc numbers threaten the future of US life science

Junior Group Leader Position at IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology

The Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) is one of Europe’s leading institutes for basic research in the life sciences. IMBA is located on t...

Austria (AT)

IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology

Open Rank Faculty, Center for Public Health Genomics

Center for Public Health Genomics & UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center seek 2 tenure-track faculty members in Cancer Precision Medicine/Precision Health.

Charlottesville, Virginia

Center for Public Health Genomics at the University of Virginia

Husbandry Technician I

Memphis, Tennessee

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (St. Jude)

Lead Researcher – Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation & Cellular Therapy

Researcher in the center for in vivo imaging and therapy.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Typical structure of a research paper

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Jerz's Literacy Weblog (est. 1999)

Short research papers: how to write academic essays.

Jerz > Writing > Academic > Research Papers [ Title | Thesis | Blueprint | Quoting | Citing | MLA Format ]

This document focuses on the kind of short, narrowly-focused research papers that might be the final project in a freshman writing class or 200-level literature survey course.

In high school, you probably wrote a lot of personal essays (where your goal was to demonstrate you were engaged) and a lot of info-dump paragraphs (where your goal was to demonstrate you could remember and organize information your teacher told you to learn).

How is a college research essay different from the writing you did in high school?

This short video covers the same topic in a different way; I think the video and handout work together fairly well.

The assignment description your professor has already given you is your best source for understanding your specific writing task, but in general, a college research paper asks you to use evidence to defend some non-obvious, nuanced point about a complex topic.

Some professors may simply want you to explain a situation or describe a process; however, a more challenging task asks you to take a stand, demonstrating you can use credible sources to defend your original ideas.

- Choose a Narrow Topic

- Use Sources Appropriately

Avoid Distractions

Outside the classroom, if I want to “research” which phone I should buy, I would start with Google.

I would watch some YouTube unboxing videos, and I might ask my friends on social media. I’d assume somebody already has written about or knows about the latest phones, and the goal of my “research” is to find what the people I trust think is the correct answer.

An entomologist might do “research” by going into the forest, and catching and observing hundreds or thousands of butterflies. If she had begun and ended her research by Googling for “butterflies of Pennsylvania” she would never have seen, with her own eyes, that unusual specimen that leads her to conclude she has discovered a new species.

Her goal as a field researcher is not to find the “correct answer” that someone else has already published. Instead, her goal is to add something new to the store of human knowledge — something that hasn’t been written down yet.

As an undergraduate with a few short months or weeks to write a research paper, you won’t be expected to discover a new species of butterfly, or convince everyone on the planet to accept what 99.9% of scientists say about vaccines or climate change, or to adopt your personal views on abortion, vaping, or tattoos.

But your professor will probably want you to read essays published by credentialed experts who are presenting their results to other experts, often in excruciating detail that most of us non-experts will probably find boring.

Your instructor probably won’t give the results of a random Google search the same weight as peer-reviewed scholarly articles from academic journals. (See “ Academic Journals: What Are They? “)

The best databases are not free, but your student ID will get you access to your school’s collection of databases, so you should never have to pay to access any source. (Your friendly school librarian will help you find out exactly how to access the databases at your school.)

1. Plan to Revise

Even a very short paper is the result of a process.

- You start with one idea, you test it, and you hit on something better.

- You might end up somewhere unexpected. If so, that’s good — it means you learned something.

- If you’re only just starting your paper, and it’s due tomorrow, you have already robbed yourself of your most valuable resource — time.

Showcase your best insights at the beginning of your paper (rather than saving them for the end).

You won’t know what your best ideas are until you’ve written a full draft. Part of revision involves identifying strong ideas and making them more prominent, identifying filler and other weak material, and pruning it away to leave more room to develop your best ideas.

- It’s normal, in a your very first “discovery draft,” to hit on a really good idea about two-thirds of the way through your paper.

- But a polished academic paper is not a mystery novel. (A busy reader will not have the patience to hunt for clues.)

- A thesis statement that includes a clear reasoning blueprint (see “ Blueprinting: Planning Your Essay “) will help your reader identify and follow your ideas.

Before you submit your draft, make sure the title, the introduction, and the conclusion match . (I am amazed at how many students overlook this simple step.)

2. Choose a Narrow Topic

A short undergraduate research paper is not the proper occasion for you to tackle huge issues, such as, “Was Hamlet Shakespeare’s Best Tragedy?” or “Women’s Struggle for Equality” or “How to Eliminate Racism.” You won’t be graded down simply because you don’t have all the answers right away. The trick is to zoom in on one tiny little part of the argument .

Short Research Paper: Sample Topics

How would you improve each of these paper topics? (My responses are at the bottom of the page.)

- Environmentalism in America

- Immigration Trends in Wisconsin’s Chippewa Valley

- Drinking and Driving

- Local TV News

- 10 Ways that Advertisers Lie to the Public

- Athletes on College Campuses

3. Use Sources Appropriately

Unless you were asked to write an opinion paper or a reflection statement, your professor probably expects you to draw a topic from the assigned readings (if any).

- Some students frequently get this backwards — they write the paper first, then “look for quotes” from sources that agree with the opinions they’ve already committed to. (That’s not really doing research to learn anything new — that’s just looking for confirmation of what you already believe.)

- Start with the readings, but don’t pad your paper with summary .

- Many students try doing most of their research using Google. Depending on your topic, the Internet may simply not have good sources available.

- Go ahead and surf as you try to narrow your topic, but remember: you still need to cite whatever you find. (See: “ Researching Academic Papers .”)

When learning about the place of women in Victorian society, Sally is shocked to discover women couldn’t vote or own property. She begins her paper by listing these and other restrictions, and adds personal commentary such as:

Women can be just as strong and capable as men are. Why do men think they have the right to make all the laws and keep all the money, when women stay in the kitchen? People should be judged by what they contribute to society, not by the kind of chromosomes they carry.

After reaching the required number of pages, she tacks on a conclusion about how women are still fighting for their rights today, and submits her paper.

- during the Victorian period, female authors were being published and read like never before

- the public praised Queen Victoria (a woman!) for making England a world empire

- some women actually fought against the new feminists because they distrusted their motives

- many wealthy women in England were downright nasty to their poorer sisters, especially the Irish.

- Sally’s paper focused mainly on her general impression that sexism is unfair (something that she already believed before she started taking the course), but Sally has not engaged with the controversies or surprising details (such as, for instance, the fact that for the first time male writers were writing with female readers in mind; or that upperclass women contributed to the degradation of lower-class women).

On the advice of her professor, Sally revises her paper as follows:

Sally’s focused revision (right) makes specific reference to a particular source , and uses a quote to introduce a point. Sally still injects her own opinion, but she is offering specific comments on complex issues, not bumper-sticker slogans and sweeping generalizations, such as those given on the left.

Documenting Evidence

Back up your claims by quoting reputable sources . If you write”Recent research shows that…” or “Many scholars believe that…”, you are making a claim. You will have to back it up with authoritative evidence. This means that the body of your paper must include references to the specific page numbers where you got your outside information. (If your document is an online source that does not provide page numbers, ask your instructor what you should do. There might be a section title or paragraph number that you could cite, or you might print out the article and count the pages in your printout.)

Avoid using words like “always” or “never,” since all it takes is a single example to the contrary to disprove your claim. Likewise, be careful with words of causation and proof. For example, consider the claim that television causes violence in kids. The evidence might be that kids who commit crimes typically watch more television than kids who don’t. But… maybe the reason kids watch more television is that they’ve dropped out of school, and are unsupervised at home. An unsupervised kid might watch more television, and also commit more crimes — but that doesn’t mean that the television is the cause of those crimes.

You don’t need to cite common facts or observations, such as “a circle has 360 degrees” or “8-tracks and vinyl records are out of date,” but you would need to cite claims such as “circles have religious and philosophical significance in many cultures” or “the sales of 8-track tapes never approached those of vinyl records.”

Don’t waste words referring directly to “quotes” and “sources.”

If you use words like “in the book My Big Boring Academic Study , by Professor H. Pompous Windbag III, it says” or “the following quote by a government study shows that…” you are wasting words that would be better spent developing your ideas.

In the book Gramophone, Film, Typewriter , by Fredrich A. Kittler, it talks about writing and gender, and says on page 186, “an omnipresent metaphor equated women with the white sheet of nature or virginity onto which a very male stylus could inscribe the glory of its authorship.” As you can see from this quote, all this would change when women started working as professional typists.

The “it talks about” and “As you can see from this quote” are weak attempts to engage with the ideas presented by Kittler. “In the book… it talks” is wordy and nonsensical (books don’t talk).

MLA style encourages you to expend fewer words introducing your sources , and more words developing your own ideas. MLA style involves just the author’s last name, a space ( not a comma), and then the page number. Leave the author’s full name and the the title of the source for the Works Cited list at the end of your paper. Using about the same space as the original, see how MLA style helps an author devote more words to developing the idea more fully:

Before the invention of the typewriter, “an omnipresent metaphor” among professional writers concerned “a very male stylus” writing upon the passive, feminized “white sheet of nature or virginity” (Kittler 186). By contrast, the word “typewriter” referred to the machine as well as the female typist who used it (183).

See “ Quotations: Integrating them in MLA-Style Papers. ”

Stay On Topic

It’s fairly normal to sit and stare at the computer screen for a while until you come up with a title, then pick your way through your topic, offering an extremely broad introduction (see glittering generalities , below)..

- You might also type in a few long quotations that you like.

- After writing generalities and just poking and prodding for page or two, you will eventually hit on a fairly good idea .

- You will pursue it for a paragraph or two, perhaps throwing in another quotation.

- By then, you’ll realize that you’ve got almost three pages written, so you will tack on a hasty conclusion.

Hooray, you’ve finished your paper! Well, not quite…

- At the very least, you ought to rewrite your title and introduction to match your conclusion , so it looks like the place you ended up was where you were intending to go all along. You probably won’t get an A, because you’re still submitting two pages of fluff; but you will get credit for recognizing whatever you actually did accomplish.

- To get an A, you should delete all that fluff, use the “good idea” that you stumbled across as your new starting point , and keep going. Even “good writers” have to work — beefing up their best ideas and shaving away the rest, in order to build a whole paper that serves the good idea, rather than tacking the good idea on at the end and calling it a day.

See: Sally Slacker Writes a Paper , and Sally’s Professor Responds

Avoid Glittering Generalities

Key: Research Paper Topics

15 thoughts on “ Short Research Papers: How to Write Academic Essays ”

Hi, I was searching for some information on how to write quality academic paper when I came across your awesome article on Short Research Papers: How to Writer Academic Essays ( https://jerz.setonhill.edu/writing/academic1/short-research-papers/ ) Great stuff!!! I especially like the way you recommend sticking to the 4 basics of writing academic essays. Very few students have mastered how to avoid distractions and focus on a single topic. Many students think that the broad, sweeping statements could give them better grades but they are wrong.

However, I came across a few links that didn’t seem to be working for you. Want me to forward you the short list I jotted down? Cheers Elias

I see some broken links in the comments, but otherwise I’m not sure what you mean.

I found the part about not using my personal opinion or generalities to be very helpful. I am currently writing a 2 page paper and was having a hard time keeping it short. Now I know why. Thanks. Stick to the facts.

This seem to be old but very relevant. Most of what you have stated are things my professor has stated during class trying to prepare us to write a short thesis reading this information verses hearing it was very helpful. You have done an awesome job! I just hope I can take this and apply it to my papers!

Great Post! Thank u!

Thank you for all your effort and help. You´ve taught me a number of things, especially on what college professors´ look for in assigning students short research papers. I am bookmarking your page, and using it as a reference.

Thank you kindly. YOU´VE HELPED A LOST STUDENT FIND HER WAY!

I appreaciate all the help your web site has given to me. I have referred to it many times. I think there may be a typo under the headline of AVOID GLITTERING GENERALITIES: “Throughout the ages, mankind has found many uses for salt. Ancient tribes used it preserve meat;” This is in no way a slight – I thought you might want to know. Please forgive me if I am incorrect. Thank you again – you rock!

You are right — I’ll fix it the next time I’m at my desktop. Thank you!

i would like to say thank you for your detailed information even though it takes time to read as well as we’ve got learnings out from it . even though it’s holiday next week our teacher assigned us to make a short research paper in accordance of our selected topic ! I’m hoping that we can make it cause if we can’t make it, right away, for sure we will get a grade’s that can drop our jaws ! :) ♥ tnx ! keep it up ! ♪♪

Sorry I have not done this for years

Hello I am the mother of a high school student that needs help doing a paper proposal for her senior project. Her topic is Photography. To be honest I have done this for years and I am trying to help, but i am completely lost. What can you recommend since she told me a little late and the paper is due tomorrow 11/11/11.

This page is designed for college students, but I am sure your daughter’s teacher has assigned readings that will guide your daughter through her homework.

Any paper that your daughter writes herself, even if it is late, will be a valuable learning experience — showing her the value of managing her time better for the next time, and preparing her for the day when she will have to tackle grown-up problems on her own.

I am having a hard time with my government essay. I am 55 taking a college course for the first time, and I barely passed high school. Last year I took this course wrote the essay, and did many things wrong. It was all in the typing. I had good story line, excellent site words, and good points of arguments. It wasn’t right on paper. My format is off. Where can I find and print a format. also I need to learn site words.

Most teachers will provide a model to follow. If it’s not already part of the assignment instructions, you could ask your prof. Better yet, bring a near-complete draft to your prof’s office hours, a few days before the due date, and ask for feedback. Your school probably has a writing center or tutoring center, too.

I would like to thank you for such detailed information. I am not a native speaker and I am doing a research paper;so, as you may think, it is really a hard job for me. A friend of mine who saw my draft of Lit. Rev asked me what type of citation format i was using, MLA or APA and I was puzzeled; then I decided to check the net and came across to this! It is being such a help Elsa

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

How to Write an Article: A Proven Step-by-Step Guide

Are you dreaming of becoming a notable writer or looking to enhance your content writing skills? Whatever your reasons for stepping into the writing world, crafting compelling articles can open numerous opportunities. Writing, when viewed as a skill rather than an innate talent, is something anyone can master with persistence, practice, and the proper guidance.

That’s precisely why I’ve created this comprehensive guide on ‘how to write an article.’ Whether you’re pursuing writing as a hobby or eyeing it as a potential career path, understanding the basics will lead you to higher levels of expertise. This step-by-step guide has been painstakingly designed based on my content creation experience. Let’s embark on this captivating journey toward becoming an accomplished article writer!

What is an Article?

An article is more than words stitched together cohesively; it’s a carefully crafted medium expressing thoughts, presenting facts, sharing knowledge, or narrating stories. Essentially encapsulating any topic under the sun (or beyond!), an article is a versatile format meant to inform, entertain, or persuade readers.

Articles are ubiquitous; they grace your morning newspaper (or digital equivalents), illuminate blogs across various platforms, inhabit scholarly journals, and embellish magazines. Irrespective of their varying lengths and formats, which range from news reports and features to opinion pieces and how-to guides, all articles share some common objectives. Learning how to write this type of content involves mastering the ability to meet these underlying goals effectively.

Objectives of Article Writing

The primary goal behind learning how to write an article is not merely putting words on paper. Instead, you’re trying to communicate ideas effectively. Each piece of writing carries unique objectives intricately tailored according to the creator’s intent and the target audience’s interests. Generally speaking, when you immerse yourself in writing an article, you should aim to achieve several fundamental goals.

First, deliver value to your readers. An engaging and informative article provides insightful information or tackles a problem your audience faces. You’re not merely filling up pages; you must offer solutions, present new perspectives, or provide educational material.

Next comes advancing knowledge within a specific field or subject matter. Especially relevant for academic or industry-focused writings, articles are often used to spread original research findings and innovative concepts that strengthen our collective understanding and drive progress.

Another vital objective for those mastering how to write an article is persuasion. This can come in various forms: convincing people about a particular viewpoint or motivating them to make a specific choice. Articles don’t always have to be neutral; they can be powerful tools for shifting public opinion.

Finally, let’s not forget entertainment – because who said only fictional work can entertain? Articles can stir our emotions or pique our interest with captivating storytelling techniques. It bridges the gap between reader and writer using shared experiences or universal truths.

Remember that high-quality content remains common across all boundaries despite these distinct objectives. No matter what type of writer you aspire to become—informative, persuasive, educational, or entertaining—strive for clarity, accuracy, and stimulation in every sentence you craft.

What is the Format of an Article?

When considering how to write an article, understanding its foundation – in this case, the format – should be at the top of your list. A proper structure is like a blueprint, providing a direction for your creative construction.

First and foremost, let’s clarify one essential point: articles aren’t just homogenous chunks of text. A well-crafted article embodies different elements that merge to form an engaging, informative body of work. Here are those elements in order:

- The Intriguing Title

At the top sits the title or heading; it’s your first chance to engage with a reader. This element requires serious consideration since it can determine whether someone will continue reading your material.

- Engaging Introduction

Next comes the introduction, where you set expectations and hint at what’s to come. An artfully written introduction generates intrigue and gives readers a compelling reason to stick around.

- Informative Body

The main body entails a detailed exploration of your topic, often broken down into subtopics or points for more manageable consumption and better flow of information.

- Impactful Conclusion

Lastly, you have the conclusion, where you tie everything neatly together by revisiting key points and offering final thoughts.

While these components might appear straightforward on paper, mastering them requires practice, experimentation with writing styles, and a good understanding of your target audience.

By putting in the work to familiarize yourself with how to create articles and how they’re structured, you’ll soon discover new ways to develop engaging content each time you put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard!). Translating complex concepts into digestible content doesn’t need to feel daunting anymore! Now that we’ve tackled the format, our focus can shift to what should be included in an article.

What Should Be in an Article?

Understanding that specific items should be featured in your writing is crucial. A well-crafted article resembles a neatly packed suitcase – everything has its place and purpose.

Key Information

First and foremost, you need essential information. Start by presenting the topic plainly so readers can grasp its relevance immediately. This sets the tone of why you are writing the article. The degree of depth at this point will depend on your audience; be mindful not to overwhelm beginners with too much jargon or over-simplify things for experts.

Introduction

Secondly, every article must have an engaging introduction—this acts as the hook that reels your audience. Think of it as a movie trailer—it offers a taste of what’s to come without giving away all the details.

Third is the body, wherein you get into the crux of your argument or discussion. This is the point at which you present your ideas sequentially, along with supporting evidence or examples. Depending on the nature of your topic and personal style, this may vary from storytelling forms to more analytical breakdowns.

Lastly, you’ll need a fitting conclusion that wraps up all previously discussed points, effectively tying together every loose thread at the end. This helps cement your main ideas within the reader’s mind even after they’ve finished reading.

To summarize:

- Critical Information: Provides context for understanding

- Introduction: Sheds further light on what will follow while piquing interest

- Body: Discusses topic intricacies using narratives or case studies

- Conclusion: Ties up loose ends and reemphasizes important takeaways

In my experience writing articles for beginners and experts alike, I found these elements indispensable when conveying complex topics articulately and professionally. Always keep them at hand when looking to produce written material.

How should you structure an article?

Crafting a well-structured article is akin to assembling a puzzle – every piece has its place and purpose. Let’s look at how to create the perfect skeleton for your content.

The introduction is your article’s welcome mat. It should be inviting and informative, briefly outlining what a reader can expect from your writing. Additionally, it must instantly grab the readers’ attention so they feel compelled to continue reading. To master the art of creating effective introductions, remember these key points:

- Keep it short and precise.

- Use compelling hooks like quotes or intriguing facts.

- State clearly what the article will cover without revealing everything upfront.

Moving on, you encounter the body of your piece. This segment expands on the ideas outlined in the introduction while presenting fresh subtopics related to your core story. If we compare article writing to crossing a bridge, each paragraph represents a step toward the other side (the conclusion). Here are some tips for maintaining orderliness within your body:

- Stick closely to one idea per paragraph as it enhances readability.

- Ensure paragraphs flow logically by utilizing transitional words or sentences.

- Offer evidence or examples supporting your claims and reinforce credibility.

As you approach the far side of our imaginary bridge, we reach an equally essential section of the article known as the conclusion. At this point, you should be looking to wrap your message up neatly while delivering on what was initially promised during the introduction. This section summarizes the main points, providing closure and ensuring readers feel satisfied.

Remember this golden rule when writing the conclusion: follow the “Describe what you’re going to tell them (Introduction), tell them (Body), and then summarize what you told them (Conclusion).” It’s a proven formula for delivering informative, engaging, and well-structured articles.

One final tip before moving on: maintaining an active voice significantly enhances clarity for your readers. It makes them feel like they’re participating actively in the story unfolding within your article. In addition, it helps ensure easy readability, which is vital for keeping your audience engaged.

Tips for Writing a Good Article

A persuasive, engaging, and insightful article requires careful thought and planning. Half the battle won is by knowing how to start writing and make content captivating. Below are vital tips that can enhance your article writing skills.

Heading or Title

An audience’s first impression hinges on the quality of your title. A good heading should be clear, attention-grabbing, and give an accurate snapshot of what’s contained in the piece’s body. Here are a few guidelines on how to create an impactful title:

- Make it Compelling: Your title needs to spark interest and motivate readers to delve further into your work.

- Keep it concise: You want to have a manageable heading. Aim for brevity yet inclusiveness.

- Optimize with keywords: To boost search engine visibility, sprinkle relevant keywords naturally throughout your title.

By applying these techniques, you can increase reader engagement right from the get-go.

Body of the Article

After winning over potential readers with your catchy title, it’s time to provide substantial content in the form of the body text. Here’s how articles are typically structured:

Introduction: Begin by providing an appealing overview that hooks your audience and baits them to read more. You can ask poignant questions or share interesting facts about your topic here.

Main Content: Build on the groundwork set by your introduction. Lay out detailed information in a logical sequence with clear articulation.

Conclusion: This reemphasizes the critical points discussed in the body while delivering a lasting impression of why those points matter.

Remember that clarity is critical when drafting each part because our objective here is to share information and communicate effectively. Properly understanding this approach ensures that the writing experience becomes creative and productive.

Step By Step Guide for Article Writing

How do you write an article that engages your readers from the first line until the last? That’s what most writers, whether beginners or seasoned pros are trying to achieve. I’ll describe a step-by-step process for crafting such gripping articles in this guide.

Step 1: Find Your Target Audience

First and foremost, identify your target readers. Speaking directly to a specific group improves engagement and helps you craft messages that resonate deeply. To pinpoint your audience:

- Take note of demographic attributes like age, gender, and profession.

- Consider their preferences and needs.

- Look into how much knowledge they are likely to possess concerning your topic.

Knowing this will help you decide what tone, language, and style best suits your readers. Remember, by understanding your audience better, you make it much easier to provide them with engaging content.

Step 2: Select a Topic and an Attractive Heading

Having understood your audience, select a relevant topic based on their interests and questions. Be sure it’s one you can competently discuss. When deciding how to start writing an article, ensure it begins with a captivating title.

A title should hint at what readers will gain from the article without revealing everything. Maintain some element of intrigue or provocation. For example, ‘6 Essentials You Probably Don’t Know About Gardening’ instead of just ‘Gardening Tips’.

Step 3: Research is Key

Good research is crucial to building credibility for beginners and experts alike. It prevents errors that could tarnish your piece immensely.

Thoroughly explore relevant books, scholarly articles, or reputable online resources. Find facts that build authenticity while debunking misconceptions that relate to your topic. Take notes on critical points discovered during this process—it’ll save you time when creating your first draft.

Step 4: Write a Comprehensive Brief

Having done your research, it’s time to write an outline or a brief—a roadmap for your article. This conveys how articles are written systematically without losing track of the main points.

Begin by starting the introduction with a punchy opener that draws readers in and a summary of what they’ll glean from reading. Section out specific points and ideas as separate headings and bullet points under each section to form the body. A conclusion rounds things up by restating key takeaways.

Step 5: Write and Proofread

Now comes the bulk of the work—writing. Respect the brief created earlier to ensure consistency and structure while drafting content. Use short, clear sentences while largely avoiding jargon unless absolutely necessary.

Post-writing, proofread ardently to check for typographical errors, inconsistent tenses, and poor sentence structures—and don’t forget factual correctness! It helps to read aloud, which can reveal awkward phrases that slipped through initial edits.

Step 6: Add Images and Infographics

To break text monotony and increase comprehension, introduce visuals such as images, infographics, or videos into your piece. They provide aesthetic relief while supporting the main ideas, increasing overall engagement.

Remember to source royalty-free images or get permission for copyrighted ones—you don’t want legal battles later!

Common Mistakes to Avoid in Article Writing

Regarding article writing, a few pitfalls can compromise the quality of your content. Knowing these and how to avoid them will enhance your work’s clarity, depth, and impact.

The first mistake often made is skimping on research. An article without solid underpinnings won’t merely be bland – it might mislead readers. Therefore, prioritize comprehensive investigation before penning down anything. Understanding common misconceptions or misinterpretations about your topic will strengthen your case.

Next, sidestep unnecessary jargon or excessively complex language. While showcasing an impressive vocabulary might seem appealing, remember that your primary objective is imparting information efficiently and effectively.

Moreover, failing to structure articles effectively represents another standard error. A structured piece aids in delivering complex ideas coherently. Maintaining a logical sequence facilitates reader comprehension, whether explaining a detailed concept or narrating an incident.

A piece lacking aesthetic allure can fail its purpose regardless of the value of its text. That’s where images come into play. Neglecting them is an all-too-common mistake among beginners. Relevant pictures inserted at appropriate junctures serve as visual breaks from texts and stimulate interest among readers.

Lastly, proofreading is vital in determining whether you can deliver a well-written article. Typos and grammatical errors can significantly undermine professional credibility while disrupting a smooth reading experience.

So, when pondering how articles are written, avoiding these mistakes goes a long way toward producing high-quality content that embodies both substance and style. Remember: practice is paramount when learning how to write excellent material!

How to Write an Article with SEOwind AI Writer?

Harnessing the power of artificial intelligence has been a major step in many industries. One such significant tool is SEOwind AI Writer , which is critical for those curious about how to write an article leveraging AI. In this section, I’ll cover how you can effectively use SEOwind AI writer to create compelling articles.

Step 1: Create a Brief and Outline

The first step in writing an article revolves around understanding your audience’s interests and then articulating them in a comprehensive brief that outlines the content’s framework.

- Decide on the topic: What ideas will you share via your article?

- Define your audience: Knowing who will read your text significantly influences your tone, style, and content depth.

- Establish main points: Highlight the key points or arguments you wish to exhibit in your drafted piece. This helps create a skeleton for your work and maintain a logical flow of information.

With SEOwind:

- you get all the content and keyword research for top-performing content in one place,

- you can generate a comprehensive AI outline with one click,

- users can quickly create a title, description, and keywords that match the topic you’re writing about.

As insightful as it might seem, having a roadmap doubles as a guide throughout the creative process. SEOwind offers a user-friendly interface that allows the easy input of essential elements like keywords, title suggestions, content length, etc. These provide an insightful outline, saving time with an indispensable tool that demonstrates the practicality of article writing.

Step 2: Write an AI Article using SEOwind

Once you have a brief ready, you can write an AI article with a single click. It will consider all the data you provided and much more, such as copywriting and SEO best practices , to deliver content that ranks.

Step 3: Give it a Human Touch

Finally, SEOwind’s intuitive platform delivers impeccably constructed content to dispel any confusion about writing an article. The result is inevitably exceptional, with well-structured sentences and logically sequenced sections that meet your demands.

However, artificial intelligence can sometimes miss the unique personal touch that enhances relatability in communication—making articles more compelling. Let’s master adding individualistic charm to personalize articles so that they resonate with audiences.

Tailoring the AI-generated piece with personal anecdotes or custom inputs helps to break the monotony and bolster engagement rates. Always remember to tweak essential SEO elements like meta descriptions and relevant backlinks.

So, whether it’s enhancing casual language flow or eliminating robotic consistency, the slightest modifications can breathe life into the text and transform your article into a harmonious man-machine effort. Remember – it’s not just about technology making life easy but also how effectively we utilize this emerging trend!

Common Questions on how to write an article

Delving into the writing world, especially regarding articles, can often lead to a swarm of questions. Let’s tackle some common queries that newbies and seasoned writers frequently stumble upon to make your journey more comfortable and rewarding.

What is the easiest way to write an article?

The easiest way to write an article begins with a clear structure. Here are five simple steps you can follow:

- Identify your audience: The first thing you should consider while planning your article is who will read it? Identifying your target audience helps shape the article’s content, style, and purpose.

- Decide on a topic and outline: Determining what to write about can sometimes be a formidable task. Try to ensure you cover a topic you can cover effectively or for which you feel great passion. Next, outline the main points you want to present throughout your piece.

- Do the research: Dig deep into resources for pertinent information regarding your topic and gather as much knowledge as possible. An informed writer paves the way for a knowledgeable reader.

- Drafting phase: Begin with an engaging introduction followed by systematically fleshing out each point from your outline in body paragraphs before ending with conclusive remarks tying together all the earlier arguments.

- Fine-tune through editing and proofreading: Errors happen no matter how qualified or experienced a writer may be! So make sure to edit and proofread before publishing.

Keep these keys in mind and remain patient and persistent. There’s no easier alternative for writing an article.

How can I write an article without knowing about the topic?

We sometimes need to write about less familiar subjects – but do not fret! Here’s my approach:

- First off, start by thoroughly researching subject-centric reliable sources. The more information you have, the better poised you are to write confidently about it.

- While researching, take notes and highlight the most essential points.

- Create an outline by organizing these points logically – this essentially becomes your article’s backbone.

- Start writing based on your research and outlined structure. If certain aspects remain unclear, keep investigating until clarity prevails.

Getting outside your comfort zone can be daunting, but is also a thrilling chance to expand your horizons.

What is your process for writing an article quickly?

In terms of speed versus quality in writing an article – strikingly enough, they aren’t mutually exclusive. To produce a high-quality piece swiftly, adhere to the following steps:

- Establish purpose and audience: Before cogs start turning on phrase-spinning, be clear on why you’re writing and who will likely read it.

- Brainstorm broadly, then refine: Cast a wide net initially regarding ideas around your topic. Then, narrow down those areas that amplify your core message or meet objectives.

- Create a robust outline: A detailed roadmap prevents meandering during actual writing and saves time!

- Ignore perfection in the first draft: Speed up initial drafting by prioritizing getting your thoughts on paper over perfect grammar or sentence compositions.

- Be disciplined with edits and revisions: Try adopting a cut, shorten, and replace mantra while trimming fluff without mercy!

Writing quickly requires practice and strategic planning – but rest assured, it’s entirely possible!

Seasoned SaaS and agency growth expert with deep expertise in AI, content marketing, and SEO. With SEOwind, he crafts AI-powered content that tops Google searches and magnetizes clicks. With a track record of rocketing startups to global reach and coaching teams to smash growth, Tom's all about sharing his rich arsenal of strategies through engaging podcasts and webinars. He's your go-to guy for transforming organic traffic, supercharging content creation, and driving sales through the roof.

Table of Contents

- 1 What is an Article?

- 2 Objectives of Article Writing

- 3 What is the Format of an Article?

- 4 What Should Be in an Article?

- 5 How should you structure an article?

- 6 Tips for Writing a Good Article

- 7 Step By Step Guide for Article Writing

- 8 Common Mistakes to Avoid in Article Writing

- 9 How to Write an Article with SEOwind AI Writer?

- 10 Common Questions on how to write an article

Related Posts

AI for Content Creators: Unleashing Potential in 2024

AI-Generated Content: Unveiling the Future

AI Copywriting Techniques: The Secret to Captivating and Engaging Content

- #100Posts30DaysChallenge

- Affiliate program

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

Latest Posts

- Top Marketing Agency Business Models to Maximize Profit

- Best ChatGPT Alternatives for 2024: Choose Smarter AI!

- Top 13 Jasper AI Alternatives for 2024 – Switch Now!

- Win B2B Clients: Content Marketing Funnel 2024

- SEOwind vs MarketMuse vs Frase

- SEOwind vs Marketmuse vs Clearscope

- SEOwind vs Clearscope vs Frase

- SEOwind vs Surfer SEO vs Clearscope

- SEOwind vs Surfer SEO vs Frase

- SEOwind vs Jasper AI vs Frase

- SEOwind vs Rytr vs Jasper

- SEOwind vs Writesonic vs Rytr

- SEOwind vs Writesonic vs Copy.ai

© 2024 SEOwind.

- AI Article Writer

- Content Brief Generator

- Human vs AI Experiment

Privacy Overview

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Med Libr Assoc

- v.103(2); 2015 Apr

How to write an original research paper (and get it published)

The purpose of the Journal of the Medical Library Association (JMLA) is more than just archiving data from librarian research. Our goal is to present research findings to end users in the most useful way. The “Knowledge Transfer” model, in its simplest form, has three components: creating the knowledge (doing the research), translating and transferring it to the user, and incorporating the knowledge into use. The JMLA is in the middle part, transferring and translating to the user. We, the JMLA, must obtain the information and knowledge from researchers and then work with them to present it in the most useable form. That means the information must be in a standard acceptable format and be easily readable.

There is a standard, preferred way to write an original research paper. For format, we follow the IMRAD structure. The acronym, IMRAD, stands for I ntroduction, M ethods, R esults A nd D iscussion. IMRAD has dominated academic, scientific, and public health journals since the second half of the twentieth century. It is recommended in the “Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals” [ 1 ]. The IMRAD structure helps to eliminate unnecessary detail and allows relevant information to be presented clearly in a logical sequence [ 2 , 3 ].

Here are descriptions of the IMRAD sections, along with our comments and suggestions. If you use this guide for submission to another journal, be sure to check the publisher's prescribed formats.

The Introduction sets the stage for your presentation. It has three parts: what is known, what is unknown, and what your burning question, hypothesis, or aim is. Keep this section short, and write for a general audience (clear, concise, and as nontechnical as you can be). How would you explain to a distant colleague why and how you did the study? Take your readers through the three steps ending with your specific question. Emphasize how your study fills in the gaps (the unknown), and explicitly state your research question. Do not answer the research question. Remember to leave details, descriptions, speculations, and criticisms of other studies for the Discussion .

The Methods section gives a clear overview of what you did. Give enough information that your readers can evaluate the persuasiveness of your study. Describe the steps you took, as in a recipe, but be wary of too much detail. If you are doing qualitative research, explain how you picked your subjects to be representative.

You may want to break it into smaller sections with subheadings, for example, context: when, where, authority or approval, sample selection, data collection (how), follow-up, method of analysis. Cite a reference for commonly used methods or previously used methods rather than explaining all the details. Flow diagrams and tables can simplify explanations of methods.

You may use first person voice when describing your methods.

The Results section summarizes what the data show. Point out relationships, and describe trends. Avoid simply repeating the numbers that are already available in the tables and figures. Data should be restricted to tables as much as possible. Be the friendly narrator, and summarize the tables; do not write the data again in the text. For example, if you had a demographic table with a row of ages, and age was not significantly different among groups, your text could say, “The median age of all subjects was 47 years. There was no significant difference between groups (Table).” This is preferable to, “The mean age of group 1 was 48.6 (7.5) years and group 2 was 46.3 (5.8) years, a nonsignificant difference.”

Break the Results section into subsections, with headings if needed. Complement the information that is already in the tables and figures. And remember to repeat and highlight in the text only the most important numbers. Use the active voice in the Results section, and make it lively. Information about what you did belongs in the Methods section, not here. And reserve comments on the meaning of your results for the Discussion section.

Other tips to help you with the Results section:

- ▪ If you need to cite the number in the text (not just in the table), and the total in the group is less than 50, do not include percentage. Write “7 of 34,” not “7 (21%).”

- ▪ Do not forget, if you have multiple comparisons, you probably need adjustment. Ask your statistician if you are not sure.

The Discussion section gives you the most freedom. Most authors begin with a brief reiteration of what they did. Every author should restate the key findings and answer the question noted in the Introduction . Focus on what your data prove, not what you hoped they would prove. Start with “We found that…” (or something similar), and explain what the data mean. Anticipate your readers' questions, and explain why your results are of interest.

Then compare your results with other people's results. This is where that literature review you did comes in handy. Discuss how your findings support or challenge other studies.

You do not need every article from your literature review listed in your paper or reference list, unless you are writing a narrative review or systematic review. Your manuscript is not intended to be an exhaustive review of the topic. Do not provide a long review of the literature—discuss only previous work that is directly pertinent to your findings. Contrary to some beliefs, having a long list in the References section does not mean the paper is more scholarly; it does suggest the author is trying to look scholarly. (If your article is a systematic review, the citation list might be long.)

Do not overreach your results. Finding a perceived knowledge need, for example, does not necessarily mean that library colleges must immediately overhaul their curricula and that it will improve health care and save lives and money (unless your data show that, in which case give us a chance to publish it!). You can say “has the potential to,” though.

Always note limitations that matter, not generic limitations.

Point out unanswered questions and future directions. Give the big-picture implications of your findings, and tell your readers why they should care. End with the main findings of your study, and do not travel too far from your data. Remember to give a final take-home message along with implications.

Notice that this format does not include a separate Conclusion section. The conclusion is built into the Discussion . For example, here is the last paragraph of the Discussion section in a recent NEJM article:

In conclusion, our trial did not show the hypothesized benefit [of the intervention] in patients…who were at high risk for complications.

However, a separate Conclusion section is usually appropriate for abstracts. Systematic reviews should have an Interpretation section.

Other parts of your research paper independent of IMRAD include:

Tables and figures are the foundation for your story. They are the story. Editors, reviewers, and readers usually look at titles, abstracts, and tables and figures first. Figures and tables should stand alone and tell a complete story. Your readers should not need to refer back to the main text.

Abstracts can be free-form or structured with subheadings. Always follow the format indicated by the publisher; the JMLA uses structured abstracts for research articles. The main parts of an abstract may include introduction (background, question or hypothesis), methods, results, conclusions, and implications. So begin your abstract with the background of your study, followed by the question asked. Next, give a quick summary of the methods used in your study. Key results come next with limited raw data if any, followed by the conclusion, which answers the questions asked (the take-home message).

- ▪ Recommended order for writing a manuscript is first to start with your tables and figures. They tell your story. You can write your sections in any order. Many recommend writing your Result s, followed by Methods, Introduction, Discussion , and Abstract.

- ▪ We suggest authors read their manuscripts out loud to a group of librarians. Look for evidence of MEGO, “My Eyes Glaze Over” (attributed to Washington Post publisher Ben Bradlee and others). Modify as necessary.

- ▪ Every single paragraph should be lucid.

- ▪ Every paragraph should answer your readers' question, “Why are you telling me this?”

The JMLA welcomes all sizes of research manuscripts: definitive studies, preliminary studies, critical descriptive studies, and test-of-concept studies. We welcome brief reports and research letters. But the JMLA is more than a research journal. We also welcome case studies, commentaries, letters to the editor about articles, and subject reviews.

- +91 8287801801

- [email protected]

Research Paper | Book Publication | Collaborations | Patent

- Research Paper

- Book Publication

- Collaboration

- SCIE, SSCI, ESCI, and AHCI

How to Write a Research Article: A Comprehensive Guide

Writing a Research Article can be an unbelievably daunting task, but it is a vital skill for any researcher or academic. This blog post intends to provide a detailed instruction on how to create a Research Paper. It will delve into the crucial elements of a Research Article, including its format, various types, and how it differs from a Research Paper. By following the steps provided, you will get vital insights on how to write a well-structured and successful research piece. Whether you are a student, researcher, or professional writer, this article will help you understand the key components required to produce a high-quality Research article.

Table of Content

What is a research article .

A Research Article is a written document that represents the findings of original and authentic research. It is typically published in a peer-reviewed academic journal and is used to communicate new knowledge and ideas to the research community. Research Articles are often used as a basis for further research and are an essential part of scientific discourse.

Components of a Research Article

A Research Article typically consists of the following components:

- Abstract – A summary of the research article, including the research question, methodology, results, and conclusion.

- Introduction – This is an explanation of the purpose behind conducting the study, and a summary of the methodology adopted for the research. This section serves as the foundation of the research article and provides the reader with a contextual background for understanding the study’s objectives and methodology. It basically outlines the reason for conducting the research and provides a glimpse of the approach that will be used to answer the research question.

- Literature Review – This section entails a comprehensive examination of the relevant literature that offers a framework for the research question and presents the existing knowledge on the subject.

- Methodology – This section explains the study’s research design, data gathering, and analysis methods.

- Results – A description of the findings of the research.

- Discussion – An interpretation of the results, including their significance and implications, as well as a discussion of the limitations of the study.

- Conclusion – A summary of the research findings, their implications, and recommendations for future research.

Research Article Format

A Research Article typically follows a standard format including:

- Title : A clear and concise title that accurately reflects the research question.

- Authors : A list of authors who contributed to the research.

- Affiliations : The institutions or organizations that the authors are affiliated with.

- Abstract : A summary of the research article.

- Keywords : A list of keywords that describe the research topic.

- Introduction : A fine background of the research question and a complete overview of the methodology used.

- Literature Review : A review of the relevant literature.

- Methodology : A description of the research design, data collection, and analysis methods used.

- Results : A description of the findings of the research.

- Discussion : An interpretation of the results and their implications, as well as a discussion of the limitations of the study.

- Conclusion: A summary of the research findings and recommendations for future research.

Types of Research Articles

There are several types of research articles including:

- Original Research Articles : These are articles that report on original research.

- Review articles : These are articles that summarize and synthesize the findings of existing research.

- Case studies : These are articles that describe and analyze a specific case or cases.

- Short communications : These are brief articles that report on original research.

Research Article vs Research Paper

While research articles and Research Papers are often used interchangeably, there are some differences between the two. A research article is typically a formal, peer-reviewed document that presents the findings of original research. A research paper, on the other hand, is a broader term that can refer to any written work that presents the findings of research, including essays, reports, and dissertations.

Example of a Research Article

Here is an example of a research article:

- Title: The effects of exercise on mental health in older adults.

- Abstract : This study investigated the effects of exercise on mental health in older adults. A sample of 100 participants aged 65 and over were randomly assigned to an exercise or control group. The exercise group participated in a 12-week exercise program, while the control group received no intervention. The results showed that the exercise group had significantly lower levels of depression and anxiety compared to the control group. Additionally, the exercise group reported higher levels of well-being and satisfaction with life. These findings suggest that exercise can be an effective intervention for improving mental health in older adults.

- Introduction: Mental health issues such as depression and anxiety are common among older adults and can have a significant impact on quality of life. Exercise has been shown to have numerous physical health benefits, but its effects on mental health in older adults are less clear. This study aimed to investigate the effects of exercise on mental health outcomes in older adults.

- Literature Review: Previous research has suggested that exercise can improve mental health outcomes in older adults. For example, a study by Mather et al. (2016) found that a 12-week exercise program resulted in significant improvements in depression and anxiety in a sample of older adults. Similarly, a meta-analysis by Smith et al. (2018) found that exercise interventions were associated with improvements in various mental health outcomes, including depression and anxiety, in older adults.