We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Introduction to problem solving : strategies for the elementary math classroom

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

Obscured text back cover

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

71 Previews

14 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station51.cebu on September 27, 2020

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the authors

Introduction to Problem Solving: Strategies for the Elementary Math Classroom by O'Connell Susan (2000-02-15) Paperback Paperback – January 1, 1707

- Publisher Heinemann

- Publication date January 1, 1707

- See all details

Product details

- ASIN : B012TPFUY4

- Publisher : Heinemann (January 1, 1707)

About the authors

Susan o'connell.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Susan R. O'Connell

Sue O’Connell has been an elementary classroom teacher, math coach, and district school improvement specialist. She is the lead author for Heinemann's Math in Practice series and has authored numerous K-8 math books. She is particularly focused on instructional strategies that support mathematical thinking. She is Director of Quality Teacher Development, providing on-site professional development for schools and school districts across the country. She lives in Maryland.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Problem Solving

Problem Solving Strategies

Think back to the first problem in this chapter, the ABC Problem . What did you do to solve it? Even if you did not figure it out completely by yourself, you probably worked towards a solution and figured out some things that did not work.

Unlike exercises, there is never a simple recipe for solving a problem. You can get better and better at solving problems, both by building up your background knowledge and by simply practicing. As you solve more problems (and learn how other people solved them), you learn strategies and techniques that can be useful. But no single strategy works every time.

Pólya’s How to Solve It

George Pólya was a great champion in the field of teaching effective problem solving skills. He was born in Hungary in 1887, received his Ph.D. at the University of Budapest, and was a professor at Stanford University (among other universities). He wrote many mathematical papers along with three books, most famously, “How to Solve it.” Pólya died at the age 98 in 1985. [1]

In 1945, Pólya published the short book How to Solve It , which gave a four-step method for solving mathematical problems:

- First, you have to understand the problem.

- After understanding, then make a plan.

- Carry out the plan.

- Look back on your work. How could it be better?

This is all well and good, but how do you actually do these steps?!?! Steps 1. and 2. are particularly mysterious! How do you “make a plan?” That is where you need some tools in your toolbox, and some experience to draw upon.

Much has been written since 1945 to explain these steps in more detail, but the truth is that they are more art than science. This is where math becomes a creative endeavor (and where it becomes so much fun). We will articulate some useful problem solving strategies, but no such list will ever be complete. This is really just a start to help you on your way. The best way to become a skilled problem solver is to learn the background material well, and then to solve a lot of problems!

We have already seen one problem solving strategy, which we call “Wishful Thinking.” Do not be afraid to change the problem! Ask yourself “what if” questions:

- What if the picture was different?

- What if the numbers were simpler?

- What if I just made up some numbers?

You need to be sure to go back to the original problem at the end, but wishful thinking can be a powerful strategy for getting started.

This brings us to the most important problem solving strategy of all:

Problem Solving Strategy 2 (Try Something!). If you are really trying to solve a problem, the whole point is that you do not know what to do right out of the starting gate. You need to just try something! Put pencil to paper (or stylus to screen or chalk to board or whatever!) and try something. This is often an important step in understanding the problem; just mess around with it a bit to understand the situation and figure out what is going on.

And equally important: If what you tried first does not work, try something else! Play around with the problem until you have a feel for what is going on.

Problem 2 (Payback)

Last week, Alex borrowed money from several of his friends. He finally got paid at work, so he brought cash to school to pay back his debts. First he saw Brianna, and he gave her 1/4 of the money he had brought to school. Then Alex saw Chris and gave him 1/3 of what he had left after paying Brianna. Finally, Alex saw David and gave him 1/2 of what he had remaining. Who got the most money from Alex?

Think/Pair/Share

After you have worked on the problem on your own for a while, talk through your ideas with a partner (even if you have not solved it). What did you try? What did you figure out about the problem?

This problem lends itself to two particular strategies. Did you try either of these as you worked on the problem? If not, read about the strategy and then try it out before watching the solution.

Problem Solving Strategy 3 (Draw a Picture). Some problems are obviously about a geometric situation, and it is clear you want to draw a picture and mark down all of the given information before you try to solve it. But even for a problem that is not geometric, like this one, thinking visually can help! Can you represent something in the situation by a picture?

Draw a square to represent all of Alex’s money. Then shade 1/4 of the square — that’s what he gave away to Brianna. How can the picture help you finish the problem?

After you have worked on the problem yourself using this strategy (or if you are completely stuck), you can watch someone else’s solution.

Problem Solving Strategy 4 (Make Up Numbers). Part of what makes this problem difficult is that it is about money, but there are no numbers given. That means the numbers must not be important. So just make them up!

You can work forwards: Assume Alex had some specific amount of money when he showed up at school, say $100. Then figure out how much he gives to each person. Or you can work backwards: suppose he has some specific amount left at the end, like $10. Since he gave Chris half of what he had left, that means he had $20 before running into Chris. Now, work backwards and figure out how much each person got.

Watch the solution only after you tried this strategy for yourself.

If you use the “Make Up Numbers” strategy, it is really important to remember what the original problem was asking! You do not want to answer something like “Everyone got $10.” That is not true in the original problem; that is an artifact of the numbers you made up. So after you work everything out, be sure to re-read the problem and answer what was asked!

Problem 3 (Squares on a Chess Board)

How many squares, of any possible size, are on a 8 × 8 chess board? (The answer is not 64… It’s a lot bigger!)

Remember Pólya’s first step is to understand the problem. If you are not sure what is being asked, or why the answer is not just 64, be sure to ask someone!

Think / Pair / Share

After you have worked on the problem on your own for a while, talk through your ideas with a partner (even if you have not solved it). What did you try? What did you figure out about the problem, even if you have not solved it completely?

It is clear that you want to draw a picture for this problem, but even with the picture it can be hard to know if you have found the correct answer. The numbers get big, and it can be hard to keep track of your work. Your goal at the end is to be absolutely positive that you found the right answer. You should never ask the teacher, “Is this right?” Instead, you should declare, “Here’s my answer, and here is why I know it is correct!”

Problem Solving Strategy 5 (Try a Simpler Problem). Pólya suggested this strategy: “If you can’t solve a problem, then there is an easier problem you can solve: find it.” He also said: “If you cannot solve the proposed problem, try to solve first some related problem. Could you imagine a more accessible related problem?” In this case, an 8 × 8 chess board is pretty big. Can you solve the problem for smaller boards? Like 1 × 1? 2 × 2? 3 × 3?

Of course the ultimate goal is to solve the original problem. But working with smaller boards might give you some insight and help you devise your plan (that is Pólya’s step (2)).

Problem Solving Strategy 6 (Work Systematically). If you are working on simpler problems, it is useful to keep track of what you have figured out and what changes as the problem gets more complicated.

For example, in this problem you might keep track of how many 1 × 1 squares are on each board, how many 2 × 2 squares on are each board, how many 3 × 3 squares are on each board, and so on. You could keep track of the information in a table:

Problem Solving Strategy 7 (Use Manipulatives to Help You Investigate). Sometimes even drawing a picture may not be enough to help you investigate a problem. Having actual materials that you move around can sometimes help a lot!

For example, in this problem it can be difficult to keep track of which squares you have already counted. You might want to cut out 1 × 1 squares, 2 × 2 squares, 3 × 3 squares, and so on. You can actually move the smaller squares across the chess board in a systematic way, making sure that you count everything once and do not count anything twice.

Problem Solving Strategy 8 (Look for and Explain Patterns). Sometimes the numbers in a problem are so big, there is no way you will actually count everything up by hand. For example, if the problem in this section were about a 100 × 100 chess board, you would not want to go through counting all the squares by hand! It would be much more appealing to find a pattern in the smaller boards and then extend that pattern to solve the problem for a 100 × 100 chess board just with a calculation.

If you have not done so already, extend the table above all the way to an 8 × 8 chess board, filling in all the rows and columns. Use your table to find the total number of squares in an 8 × 8 chess board. Then:

- Describe all of the patterns you see in the table.

- Can you explain and justify any of the patterns you see? How can you be sure they will continue?

- What calculation would you do to find the total number of squares on a 100 × 100 chess board?

(We will come back to this question soon. So if you are not sure right now how to explain and justify the patterns you found, that is OK.)

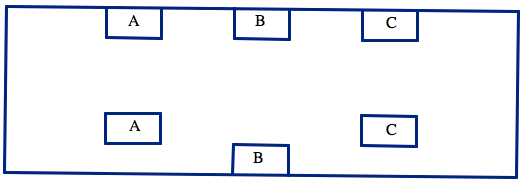

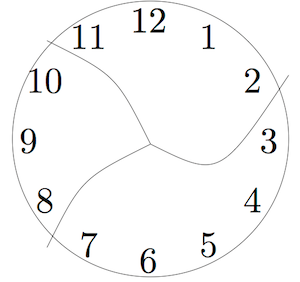

Problem 4 (Broken Clock)

This clock has been broken into three pieces. If you add the numbers in each piece, the sums are consecutive numbers. ( Consecutive numbers are whole numbers that appear one after the other, such as 1, 2, 3, 4 or 13, 14, 15.)

Can you break another clock into a different number of pieces so that the sums are consecutive numbers? Assume that each piece has at least two numbers and that no number is damaged (e.g. 12 isn’t split into two digits 1 and 2.)

Remember that your first step is to understand the problem. Work out what is going on here. What are the sums of the numbers on each piece? Are they consecutive?

After you have worked on the problem on your own for a while, talk through your ideas with a partner (even if you have not solved it). What did you try? What progress have you made?

Problem Solving Strategy 9 (Find the Math, Remove the Context). Sometimes the problem has a lot of details in it that are unimportant, or at least unimportant for getting started. The goal is to find the underlying math problem, then come back to the original question and see if you can solve it using the math.

In this case, worrying about the clock and exactly how the pieces break is less important than worrying about finding consecutive numbers that sum to the correct total. Ask yourself:

- What is the sum of all the numbers on the clock’s face?

- Can I find two consecutive numbers that give the correct sum? Or four consecutive numbers? Or some other amount?

- How do I know when I am done? When should I stop looking?

Of course, solving the question about consecutive numbers is not the same as solving the original problem. You have to go back and see if the clock can actually break apart so that each piece gives you one of those consecutive numbers. Maybe you can solve the math problem, but it does not translate into solving the clock problem.

Problem Solving Strategy 10 (Check Your Assumptions). When solving problems, it is easy to limit your thinking by adding extra assumptions that are not in the problem. Be sure you ask yourself: Am I constraining my thinking too much?

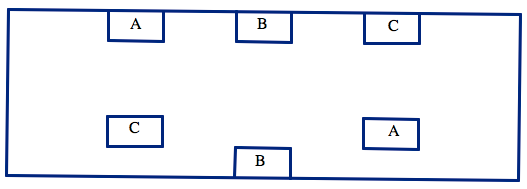

In the clock problem, because the first solution has the clock broken radially (all three pieces meet at the center, so it looks like slicing a pie), many people assume that is how the clock must break. But the problem does not require the clock to break radially. It might break into pieces like this:

Were you assuming the clock would break in a specific way? Try to solve the problem now, if you have not already.

- Image of Pólya by Thane Plambeck from Palo Alto, California (Flickr) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons ↵

Mathematics for Elementary Teachers Copyright © 2018 by Michelle Manes is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Introduction to Problem Solving: Strategies for the Elementary Math Classroom

Susan o'connell.

192 pages, Paperback

First published February 15, 2000

About the author

Ratings & Reviews

What do you think? Rate this book Write a Review

Friends & Following

Community reviews.

Join the discussion

Can't find what you're looking for.

Teaching Problem Solving in Math

- Freebies , Math , Planning

Every year my students can be fantastic at math…until they start to see math with words. For some reason, once math gets translated into reading, even my best readers start to panic. There is just something about word problems, or problem-solving, that causes children to think they don’t know how to complete them.

Every year in math, I start off by teaching my students problem-solving skills and strategies. Every year they moan and groan that they know them. Every year – paragraph one above. It was a vicious cycle. I needed something new.

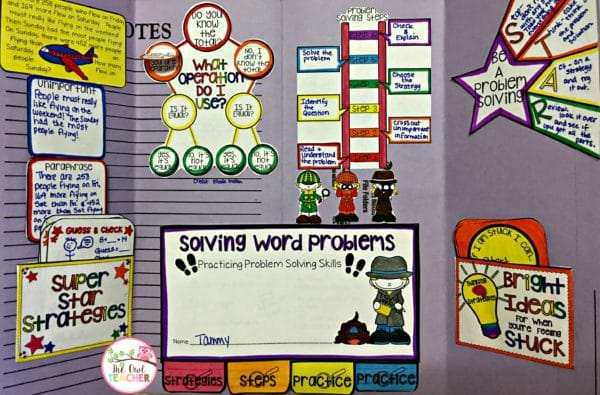

I put together a problem-solving unit that would focus a bit more on strategies and steps in hopes that that would create problem-solving stars.

The Problem Solving Strategies

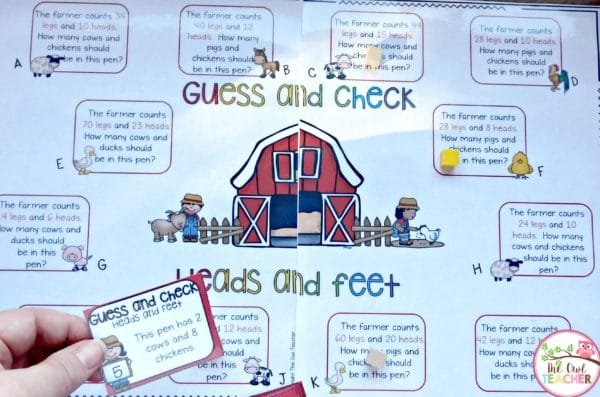

First, I wanted to make sure my students all learned the different strategies to solve problems, such as guess-and-check, using visuals (draw a picture, act it out, and modeling it), working backward, and organizational methods (tables, charts, and lists). In the past, I had used worksheet pages that would introduce one and provide the students with plenty of problems practicing that one strategy. I did like that because students could focus more on practicing the strategy itself, but I also wanted students to know when to use it, too, so I made sure they had both to practice.

I provided students with plenty of practice of the strategies, such as in this guess-and-check game.

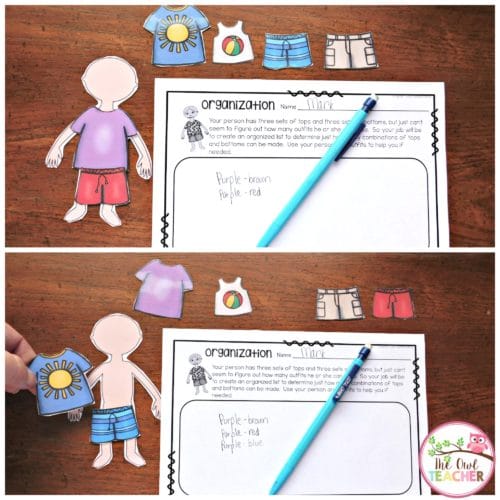

There’s also this visuals strategy wheel practice.

I also provided them with paper dolls and a variety of clothing to create an organized list to determine just how many outfits their “friend” would have.

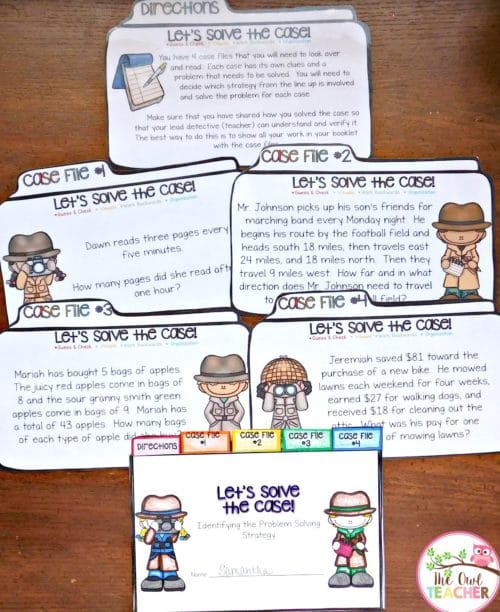

Then, as I said above, we practiced in a variety of ways to make sure we knew exactly when to use them. I really wanted to make sure they had this down!

Anyway, after I knew they had down the various strategies and when to use them, then we went into the actual problem-solving steps.

The Problem Solving Steps

I wanted students to understand that when they see a story problem, it isn’t scary. Really, it’s just the equation written out in words in a real-life situation. Then, I provided them with the “keys to success.”

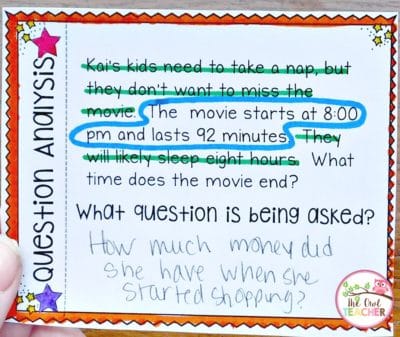

S tep 1 – Understand the Problem. To help students understand the problem, I provided them with sample problems, and together we did five important things:

- read the problem carefully

- restated the problem in our own words

- crossed out unimportant information

- circled any important information

- stated the goal or question to be solved

We did this over and over with example problems.

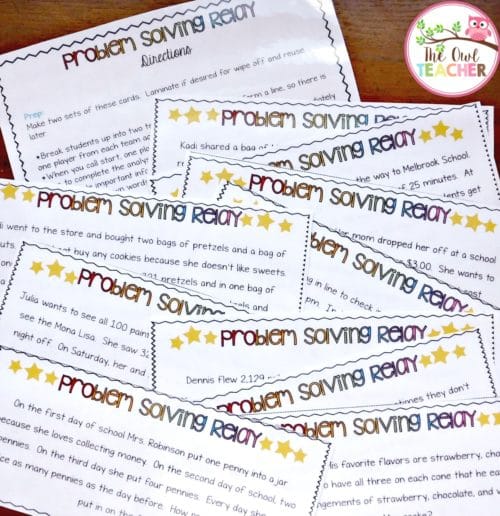

Once I felt the students had it down, we practiced it in a game of problem-solving relay. Students raced one another to see how quickly they could get down to the nitty-gritty of the word problems. We weren’t solving the problems – yet.

Then, we were on to Step 2 – Make a Plan . We talked about how this was where we were going to choose which strategy we were going to use. We also discussed how this was where we were going to figure out what operation to use. I taught the students Sheila Melton’s operation concept map.

We talked about how if you know the total and know if it is equal or not, that will determine what operation you are doing. So, we took an example problem, such as:

Sheldon wants to make a cupcake for each of his 28 classmates. He can make 7 cupcakes with one box of cupcake mix. How many boxes will he need to buy?

We started off by asking ourselves, “Do we know the total?” We know there are a total of 28 classmates. So, yes, we are separating. Then, we ask, “Is it equal?” Yes, he wants to make a cupcake for EACH of his classmates. So, we are dividing: 28 divided by 7 = 4. He will need to buy 4 boxes. (I actually went ahead and solved it here – which is the next step, too.)

Step 3 – Solving the problem . We talked about how solving the problem involves the following:

- taking our time

- working the problem out

- showing all our work

- estimating the answer

- using thinking strategies

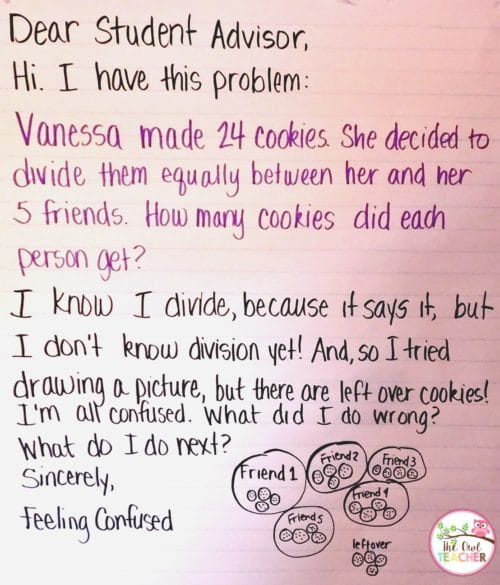

We talked specifically about thinking strategies. Just like in reading, there are thinking strategies in math. I wanted students to be aware that sometimes when we are working on a problem, a particular strategy may not be working, and we may need to switch strategies. We also discussed that sometimes we may need to rethink the problem, to think of related content, or to even start over. We discussed these thinking strategies:

- switch strategies or try a different one

- rethink the problem

- think of related content

- decide if you need to make changes

- check your work

- but most important…don’t give up!

To make sure they were getting in practice utilizing these thinking strategies, I gave each group chart paper with a letter from a fellow “student” (not a real student), and they had to give advice on how to help them solve their problem using the thinking strategies above.

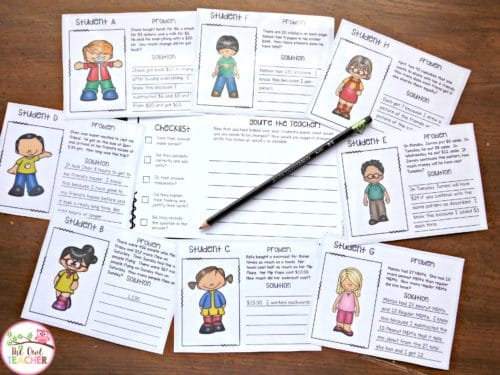

Finally, Step 4 – Check It. This is the step that students often miss. I wanted to emphasize just how important it is! I went over it with them, discussing that when they check their problems, they should always look for these things:

- compare your answer to your estimate

- check for reasonableness

- check your calculations

- add the units

- restate the question in the answer

- explain how you solved the problem

Then, I gave students practice cards. I provided them with example cards of “students” who had completed their assignments already, and I wanted them to be the teacher. They needed to check the work and make sure it was completed correctly. If it wasn’t, then they needed to tell what they missed and correct it.

To demonstrate their understanding of the entire unit, we completed an adorable lap book (my first time ever putting together one or even creating one – I was surprised how well it turned out, actually). It was a great way to put everything we discussed in there.

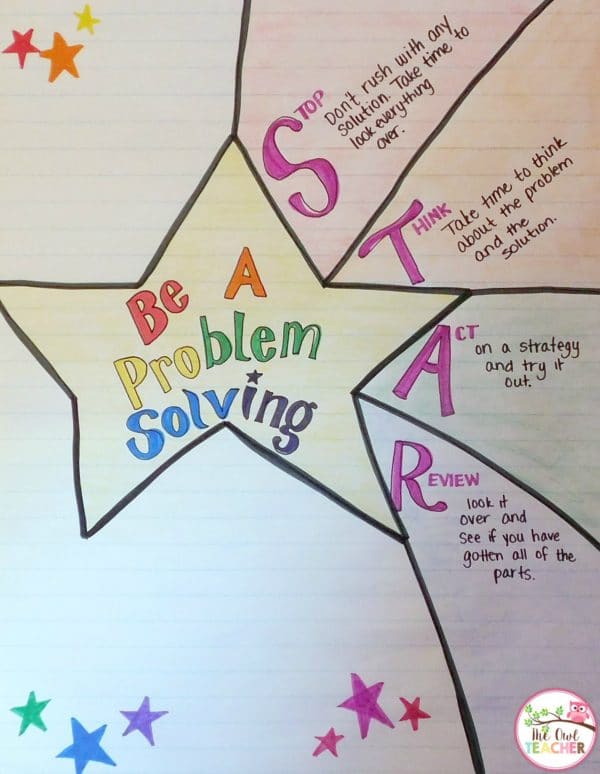

Once we were all done, students were officially Problem Solving S.T.A.R.S. I just reminded students frequently of this acronym.

Stop – Don’t rush with any solution; just take your time and look everything over.

Think – Take your time to think about the problem and solution.

Act – Act on a strategy and try it out.

Review – Look it over and see if you got all the parts.

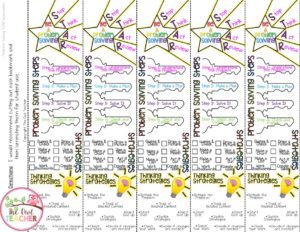

Wow, you are a true trooper sticking it out in this lengthy post! To sum up the majority of what I have written here, I have some problem-solving bookmarks FREE to help you remember and to help your students!

You can grab these problem-solving bookmarks for FREE by clicking here .

You can do any of these ideas without having to purchase anything. However, if you are looking to save some time and energy, then they are all found in my Math Workshop Problem Solving Unit . The unit is for grade three, but it may work for other grade levels. The practice problems are all for the early third-grade level.

- freebie , Math Workshop , Problem Solving

FIND IT NOW!

Check me out on tpt.

CHECK THESE OUT

Three Types of Rocks and Minerals with Rock Cycle Circle Book

Partitioning Shapes Equal Share Fractions Halves, Thirds, Fourths Math Puzzles

Want to save time?

COPYRIGHT © 2016-2024. The Owl Teacher | Privacy page | Disclosure Page | Shipping | Returns/Refunds

BOGO on EVERYTHING!

How Students Learn: Mathematics in the Classroom (2005)

Chapter: 5 mathematical understanding: an introduction.

Below is the uncorrected machine-read text of this chapter, intended to provide our own search engines and external engines with highly rich, chapter-representative searchable text of each book. Because it is UNCORRECTED material, please consider the following text as a useful but insufficient proxy for the authoritative book pages.

217 MATHEMATICAL UNDERSTANDING: AN INTRODUCTION 5 Mathematical Understanding: An Introduction Karen C. Fuson, Mindy Kalchman, and John D. Bransford For many people, free association with the word âmathematicsâ would produce strong, negative images. Gary Larson published a cartoon entitled âHellâs Libraryâ that consisted of nothing but book after book of math word problems. Many studentsâand teachersâresonate strongly with this cartoonâs message. It is not just funny to them; it is true. Why are associations with mathematics so negative for so many people? If we look through the lens of How People Learn, we see a subject that is rarely taught in a way that makes use of the three principles that are the focus of this volume. Instead of connecting with, building on, and refining the mathematical understandings, intuitions, and resourcefulness that stu- dents bring to the classroom (Principle 1), mathematics instruction often overrides studentsâ reasoning processes, replacing them with a set of rules and procedures that disconnects problem solving from meaning making. Instead of organizing the skills and competences required to do mathemat- ics fluently around a set of core mathematical concepts (Principle 2), those skills and competencies are often themselves the center, and sometimes the whole, of instruction. And precisely because the acquisition of procedural knowledge is often divorced from meaning making, students do not use metacognitive strategies (Principle 3) when they engage in solving math- ematics problems. Box 5-1 provides a vignette involving a student who gives an answer to a problem that is quite obviously impossible. When quizzed, he can see that his answer does not make sense, but he does not consider it wrong because he believes he followed the rule. Not only did he neglect to use metacognitive strategies to monitor whether his answer made sense, but he believes that sense making is irrelevant.

218 HOW STUDENTS LEARN: MATHEMATICS IN THE CLASSROOM BOX 5-1 Computation Without Comprehension: An Observation by John Holt One boy, quite a good student, was working on the problem, âIf you have 6 jugs, and you want to put 2/3 of a pint of lemonade into each jug, how much lemonade will you need?â His answer was 18 pints. I said, âHow much in each jug?â âTwo- thirds of a pint.â I said, âIs that more or less that a pint?â âLess.â I said, âHow many jugs are there?â âSix.â I said, âBut that [the answer of 18 pints] doesnât make any sense.â He shrugged his shoulders and said, âWell, thatâs the way the system worked out.â Holt argues: âHe has long since quit expecting school to make sense. They tell you these facts and rules, and your job is to put them down on paper the way they tell you. Never mind whether they mean anything or not.â1 A recent report of the National Research Council,2 Adding It Up, reviews a broad research base on the teaching and learning of elementary school mathematics. The report argues for an instructional goal of âmathematical proficiency,â a much broader outcome than mastery of procedures. The report argues that five intertwining strands constitute mathematical profi- ciency: 1. Conceptual understandingâcomprehension of mathematical con- cepts, operations, and relations 2. Procedural fluencyâskill in carrying out procedures flexibly, accu- rately, efficiently, and appropriately 3. Strategic competenceâability to formulate, represent, and solve math- ematical problems 4. Adaptive reasoningâcapacity for logical thought, reflection, expla- nation, and justification 5. Productive dispositionâhabitual inclination to see mathematics as sensible, useful, and worthwhile, coupled with a belief in diligence and oneâs own efficacy These strands map directly to the principles of How People Learn. Prin- ciple 2 argues for a foundation of factual knowledge (procedural fluency), tied to a conceptual framework (conceptual understanding), and organized in a way to facilitate retrieval and problem solving (strategic competence). Metacognition and adaptive reasoning both describe the phenomenon of ongoing sense making, reflection, and explanation to oneself and others. And, as we argue below, the preconceptions students bring to the study of mathematics affect more than their understanding and problem solving; those preconceptions also play a major role in whether students have a productive

219 MATHEMATICAL UNDERSTANDING: AN INTRODUCTION disposition toward mathematics, as do, of course, their experiences in learn- ing mathematics. The chapters that follow on whole number, rational number, and func- tions look at the principles of How People Learn as they apply to those specific domains. In this introduction, we explore how those principles ap- ply to the subject of mathematics more generally. We draw on examples from the Childrenâs Math World project, a decade-long research project in urban and suburban English-speaking and Spanish-speaking classrooms.3 PRINCIPLE #1: TEACHERS MUST ENGAGE STUDENTSâ PRECONCEPTIONS At a very early age, children begin to demonstrate an awareness of number.4 As with language, that awareness appears to be universal in nor- mally developing children, though the rate of development varies at least in part because of environmental influences.5 But it is not only the awareness of quantity that develops without formal training. Both children and adults engage in mathematical problem solving, developing untrained strategies to do so successfully when formal experi- ences are not provided. For example, it was found that Brazilian street chil- dren could perform mathematics when making sales in the street, but were unable to answer similar problems presented in a school context.6 Likewise, a study of housewives in California uncovered an ability to solve mathemati- cal problems when comparison shopping, even though the women could not solve problems presented abstractly in a classroom that required the same mathematics.7 A similar result was found in a study of a group of Weight Watchers, who used strategies for solving mathematical measure- ment problems related to dieting that they could not solve when the prob- lems were presented more abstractly.8 And men who successfully handi- capped horse races could not apply the same skill to securities in the stock market.9 These examples suggest that people possess resources in the form of informal strategy development and mathematical reasoning that can serve as a foundation for learning more abstract mathematics. But they also suggest that the link is not automatic. If there is no bridge between informal and formal mathematics, the two often remain disconnected. The first principle of How People Learn emphasizes both the need to build on existing knowledge and the need to engage studentsâ preconcep- tionsâparticularly when they interfere with learning. In mathematics, cer- tain preconceptions that are often fostered early on in school settings are in fact counterproductive. Students who believe them can easily conclude that the study of mathematics is ânot for themâ and should be avoided if at all possible. We discuss these preconceptions below.

220 HOW STUDENTS LEARN: MATHEMATICS IN THE CLASSROOM Some Common Preconceptions About Mathematics Preconception #1: Mathematics is about learning to compute. Many of us who attended school in the United States had mathematics instruction that focused primarily on computation, with little attention to learning with understanding. To illustrate, try to answer the following ques- tion: What, approximately, is the sum of 8/9 plus 12/13? Many people immediately try to find the lowest common denominator for the two sets of fractions and then add them because that is the procedure they learned in school. Finding the lowest common denominator is not easy in this instance, and the problem seems difficult. A few people take a con- ceptual rather than a procedural (computational) approach and realize that 8/9 is almost 1, and so is 12/13, so the approximate answer is a little less than 2. The point of this example is not that computation should not be taught or is unimportant; indeed, it is very often critical to efficient problem solv- ing. But if one believes that mathematics is about problem solving and that computation is a tool for use to that end when it is helpful, then the above problem is viewed not as a ârequest for a computation,â but as a problem to be solved that may or may not require computationâand in this case, it does not. If one needs to find the exact answer to the above problem, computa- tion is the way to go. But even in this case, conceptual understanding of the nature of the problem remains central, providing a way to estimate the cor- rectness of a computation. If an answer is computed that is more than 2 or less than 1, it is obvious that some aspect of problem solving has gone awry. If one believes that mathematics is about computation, however, then sense making may never take place. Preconception #2: Mathematics is about âfollowing rulesâ to guarantee correct answers. Related to the conception of mathematics as computation is that of math- ematics as a cut-and-dried discipline that specifies rules for finding the right answers. Rule following is more general than performing specific computa- tions. When students learn procedures for keeping track of and canceling units, for example, or learn algebraic procedures for solving equations, many

221 MATHEMATICAL UNDERSTANDING: AN INTRODUCTION view use of these procedures only as following the rules. But the ârulesâ should not be confused with the game itself. The authors of the chapters in this part of the book provide important suggestions about the much broader nature of mathematical proficiency and about ways to make the involving nature of mathematical inquiry visible to students. Groups such as the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics10 and the National Research Council11 have provided important guidelines for the kinds of mathematics instruction that accord with what is currently known about the principles of How People Learn. The authors of the following chapters have paid careful attention to this work and illustrate some of its important aspects. In reality, mathematics is a constantly evolving field that is far from cut and dried. It involves systematic pattern finding and continuing invention. As a simple example, consider the selection of units that are relevant to quantify an idea such as the fuel efficiency of a vehicle. If we choose miles per gallon, a two-seater sports car will be more efficient than a large bus. If we choose passenger miles per gallon, the bus will be more fuel efficient (assuming it carries large numbers of passengers). Many disciplines make progress by inventing new units and metrics that provide insights into previ- ously invisible relationships. Attention to the history of mathematics illustrates that what is taught at one point in time as a set of procedures really was a set of clever inventions designed to solve pervasive problems of everyday life. In Europe in the Middle Ages, for example, people used calculating cloths marked with ver- tical columns and carried out procedures with counters to perform calcula- tions. Other cultures fastened their counters on a rod to make an abacus. Both of these physical means were at least partially replaced by written methods of calculating with numerals and more recently by methods that involve pushing buttons on a calculator. If mathematics procedures are un- derstood as inventions designed to make common problems more easily solvable, and to facilitate communications involving quantity, those proce- dures take on a new meaning. Different procedures can be compared for their advantages and disadvantages. Such discussions in the classroom can deepen studentsâ understanding and skill. Preconception #3: Some people have the ability to âdo mathâ and some donât. This is a serious preconception that is widespread in the United States, but not necessarily in other countries. It can easily become a self-fulfilling prophesy. In many countries, the ability to âdo mathâ is assumed to be attributable to the amount of effort people put into learning it.12 Of course,

222 HOW STUDENTS LEARN: MATHEMATICS IN THE CLASSROOM some people in these countries do progress further than others, and some appear to have an easier time learning mathematics than others. But effort is still considered to be the key variable in success. In contrast, in the United States we are more likely to assume that ability is much more important than effort, and it is socially acceptable, and often even desirable, not to put forth effort in learning mathematics. This difference is also related to cultural differences in the value attributed to struggle. Teachers in some countries believe it is desirable for students to struggle for a while with problems, whereas teachers in the United States simplify things so that students need not struggle at all.13 This preconception likely shares a common root with the others. If mathematics learning is not grounded in an understanding of the nature of the problem to be solved and does not build on a studentâs own reasoning and strategy development, then solving problems successfully will depend on the ability to recall memorized rules. If a student has not reviewed those rules recently (as is the case when a summer has passed), they can easily be forgotten. Without a conceptual understanding of the nature of problems and strategies for solving them, failure to retrieve learned procedures can leave a student completely at a loss. Yet students can feel lost not only when they have forgotten, but also when they fail to âget itâ from the start. Many of the conventions of math- ematics have been adopted for the convenience of communicating efficiently in a shared language. If students learn to memorize procedures but do not understand that the procedures are full of such conventions adopted for efficiency, they can be baffled by things that are left unexplained. If students never understand that x and y have no intrinsic meaning, but are conven- tional notations for labeling unknowns, they will be baffled when a z ap- pears. When an m precedes an x in the equation of a line, students may wonder, Why m? Why not s for slope? If there is no m, then is there no slope? To someone with a secure mathematics understanding, the missing m is simply an unstated m = 1. But to a student who does not understand that the point is to write the equation efficiently, the missing m can be baffling. Unlike language learning, in which new expressions can often be figured out because they are couched in meaningful contexts, there are few clues to help a student who is lost in mathematics. Providing a secure conceptual understanding of the mathematics enterprise that is linked to studentsâ sense- making capacities is critical so that students can puzzle productively over new material, identify the source of their confusion, and ask questions when they do not understand.

223 MATHEMATICAL UNDERSTANDING: AN INTRODUCTION Engaging Studentsâ Preconceptions and Building on Existing Knowledge Engaging and building on student preconceptions, then, poses two in- structional challenges. First, how can we teach mathematics so students come to appreciate that it is not about computation and following rules, but about solving important and relevant quantitative problems? This perspective in- cludes an understanding that the rules for computation and solution are a set of clever human inventions that in many cases allow us to solve complex problems more easily, and to communicate about those problems with each other effectively and efficiently. Second, how can we link formal mathemat- ics training with studentsâ informal knowledge and problem-solving capaci- ties? Many recent research and curriculum development efforts, including those of the authors of the chapters that follow, have addressed these ques- tions. While there is surely no single best instructional approach, it is pos- sible to identify certain features of instruction that support the above goals: ⢠Allowing students to use their own informal problem-solving strate- gies, at least initially, and then guiding their mathematical thinking toward more effective strategies and advanced understandings. ⢠Encouraging math talk so that students can clarify their strategies to themselves and others, and compare the benefits and limitations of alternate approaches. ⢠Designing instructional activities that can effectively bridge commonly held conceptions and targeted mathematical understandings. Allowing Multiple Strategies To illustrate how instruction can be connected to studentsâ existing knowl- edge, consider three subtraction methods encountered frequently in urban second-grade classrooms involved in the Childrenâs Math Worlds Project (see Box 5-2). Maria, Peter, and Manuelâs teacher has invited them to share their methods for solving a problem, and each of them has displayed a different method. Two of the methods are correct, and one is mostly correct but has one error. What the teacher does depends on her conception of what math- ematics is. One approach is to show the students the ârightâ way to subtract and have them and everyone else practice that procedure. A very different ap- proach is to help students explore their methods and see what is easy and difficult about each. If students are taught that for each kind of math situa- tion or problem, there is one correct method that needs to be taught and learned, the seeds of the disconnection between their reasoning and strat- egy development and âdoing mathâ are sown. An answer is either wrong or

224 HOW STUDENTS LEARN: MATHEMATICS IN THE CLASSROOM Three Subtraction Methods BOX 5-2 Mariaâs add-equal- Peterâs ungrouping Manuelâs mixed quantities method method method 11 14 11 14 1 2 14 12 4 12 4 â 15 6 â 15 â56 6 68 68 5 8 right, and one does not need to look at wrong answers more deeplyâone needs to look at how to get the right answer. The problem is not that stu- dents will fail to solve the problem accurately with this instructional ap- proach; indeed, they may solve it more accurately. But when the nature of the problem changes slightly, or students have not used the taught approach for a while, they may feel completely lost when confronting a novel prob- lem because the approach of developing strategies to grapple with a prob- lem situation has been short-circuited. If, on the other hand, students believe that for each kind of math situa- tion or problem there can be several correct methods, their engagement in strategy development is kept alive. This does not mean that all strategies are equally good. But students can learn to evaluate different strategies for their advantages and disadvantages. What is more, a wrong answer is usually partially correct and reflects some understanding; finding the part that is wrong and understanding why it is wrong can be a powerful aid to under- standing and promotes metacognitive competencies. A vignette of students engaged in the kind of mathematical reasoning that supports active strategy development and evaluation appears in Box 5-3. It can be initially unsettling for a teacher to open up the classroom to calculation methods that are new to the teacher. But a teacher does not have to understand a new method immediately or alone, as indicated in the de- scription in the vignette of how the class together figured out over time how Mariaâs method worked (this method is commonly taught in Latin America and Europe). Understanding a new method can be a worthwhile mathemati- cal project for the class, and others can be involved in trying to figure out why a method works. This illustrates one way in which a classroom commu- nity can function. If one relates a calculation method to the quantities in- volved, one can usually puzzle out what the method is and why it works. This also demonstrates that not all mathematical issues are solved or under- stood immediately; sometimes sustained work is necessary.

225 MATHEMATICAL UNDERSTANDING: AN INTRODUCTION Engaging Studentsâ Problem-Solving Strategies BOX 5-3 The following example of a classroom discussion shows how second- grade students can explain their methods rather than simply performing steps in a memorized procedure. It also shows how to make student thinking visible. After several months of teaching and learning, the stu- dents reached the point illustrated below. The studentsâ methods are shown in Box 5-2. Teacher Maria, can you please explain to your friends in the class how you solved the problem? Maria Six is bigger than 4, so I canât subtract here [pointing] in the ones. So I have to get more ones. But I have to be fair when I get more ones, so I add ten to both my numbers. I add a ten here in the top of the ones place [pointing] to change the 4 to a 14, and I add a ten here in the bottom in the tens place, so I write another ten by my 5. So now I count up from 6 to 14, and I get 8 ones [demonstrating by counting â6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14â while raising a finger for each word from 7 to 14]. And I know my doubles, so 6 plus 6 is 12, so I have 6 tens left. [She thought, â1 + 5 = 6 tens and 6 + ? = 12 tens. Oh, I know 6 + 6 = 12, so my answer is 6 tens.â] Jorge I donât see the other 6 in your tens. I only see one 6 in your answer. Maria The other 6 is from adding my 1 ten to the 5 tens to get 6 tens. I didnât write it down. Andy But youâre changing the problem. How do you get the right answer? Maria If I make both numbers bigger by the same amount, the difference will stay the same. Remember we looked at that on drawings last week and on the meter stick. Michelle Why did you count up? Maria Counting down is too hard, and my mother taught me to count up to subtract in first grade.

226 HOW STUDENTS LEARN: MATHEMATICS IN THE CLASSROOM Continued BOX 5-3 Teacher How many of you remember how confused we were when we first saw Mariaâs method last week? Some of us could not figure out what she was doing even though Elena and Juan and Elba did it the same way. What did we do? Rafael We made drawings with our ten-sticks and dots to see what those numbers meant. And we figured out they were both tens. Even though the 5 looked like a 15, it was really just 6. And we went home to see if any of our parents could explain it to us, but we had to figure it out ourselves and it took us 2 days. Teacher Yes, I was asking other teachers, too. We worked on other methods too, but we kept trying to understand what this method was and why it worked. And Elena and Juan decided it was clearer if they crossed out the 5 and wrote a 6, but Elba and Maria liked to do it the way they learned at home. Any other questions or comments for Maria? No? Ok, Peter, can you explain your method? Peter Yes, I like to ungroup my top number when I donât have enough to subtract everywhere. So here I ungrouped 1 ten and gave it to the 4 ones to make 14 ones, so I had 1 ten left here. So 6 up to 10 is 4 and 4 more up to 14 is 8, so 14 minus 6 is 8 ones. And 5 tens up to 11 tens is 6 tens. So my answer is 68. Carmen How did you know it was 11 tens? Peter Because it is 1 hundred and 1 ten and that is 11 tens. Carmen I donât get it. Peter Because 1 hundred is 10 tens. Carmen Oh, so why didnât you cross out the 1 hundred and put it with the tens to make 11 tens like Manuel? Peter I donât need to. I just know it is 11 tens by looking at it. Teacher Manuel, donât erase your problem. I know you think it is probably wrong because you got a different answer, but remember how making a mistake helps everyone learnâbecause other

227 MATHEMATICAL UNDERSTANDING: AN INTRODUCTION students make that same mistake and you helped us talk about it. Do you want to draw a picture and think about your method while we do the next problem, or do you want someone to help you? Manuel Can Rafael help me? Teacher Yes, but what kind of helping should Rafael do? Manuel He should just help me with what I need help on and not do it for me. Teacher Ok, Rafael, go up and help Manuel that way while we go on to the next problem. I think it would help you to draw quick-tens and ones to see what your numbers mean. [These draw- ings are explained later.] But leave your first solution so we can all see where the problem is. That helps us all get good at debuggingâ finding our mistakes. Do we all make mis- takes? Class Yes. Teacher Can we all get help from each other? Class Yes. Teacher So mistakes are just a part of learning. We learn from our mistakes. Manuel is going to be brave and share his mistake with us so we can all learn from it. Manuelâs method combined Mariaâs add-equal-quantities method, which he had learned at home, and Peterâs ungrouping method, which he had learned at school. It increases the ones once and decreases the tens twice by subtracting a ten from the top number and adding a ten to the bottom subtracted number. In the Childrenâs Math Worlds Project, we rarely found children forming such a meaningless combination of meth- ods if they understood tens and ones and had a method of drawing them so they could think about the quantities in a problem (a point discussed more later). Students who transferred into our classes did sometimes initially use Manuelâs mixed approach. But students were eventually helped to understand both the strengths and weaknesses of their existing meth- ods and to find ways of improving their approaches. SOURCE: Karen Fuson, Childrenâs Math Worlds Project.

228 HOW STUDENTS LEARN: MATHEMATICS IN THE CLASSROOM Encouraging Math Talk One important way to make studentsâ thinking visible is through math talkâtalking about mathematical thinking. This technique may appear obvi- ous, but it is quite different from simply giving lectures or assigning text- book readings and then having students work in isolation on problem sets or homework problems. Instead, students and teachers actively discuss how they approached various problems and why. Such communication about mathematical thinking can help everyone in the classroom understand a given concept or method because it elucidates contrasting approaches, some of which are wrongâbut often for interesting reasons. Furthermore, com- municating about oneâs thinking is an important goal in itself that also facili- tates other sorts of learning. In the lower grades, for example, such math talk can provide initial experiences with mathematical justification that cul- minate in later grades with more formal kinds of mathematical proof. An emphasis on math talk is also important for helping teachers become more learner focused and make stronger connections with each of their students. When teachers adopt the role of learners who try to understand their studentsâ methods (rather than just marking the studentsâ procedures and answers as correct or incorrect), they frequently discover thinking that can provide a springboard for further instruction, enabling them to extend thinking more deeply or understand and correct errors. Note that, when beginning to make student thinking visible, teachers must focus on the com- munity-centered aspects of their instruction. Students need to feel comfort- able expressing their ideas and revising their thinking when feedback sug- gests the need to do so. Math talk allows teachers to draw out and work with the preconcep- tions students bring with them to the classroom and then helps students learn how to do this sort of work for themselves and for others. We have found that it is also helpful for students to make math drawings of their thinking to help themselves in problem solving and to make their thinking more visible (see Figure 5-1). Such drawings also support the classroom math talk because they are a common visual referent for all participants. Students need an effective bridge between their developing understandings and formal mathematics. Teachers need to use carefully designed visual, linguistic, and situational conceptual supports to help students connect their experiences to formal mathematical words, notations, and methods. The idea of conceptual support for math talk can be further clarified by considering the language students used in the vignette in Box 5-3 when they explained their different multidigit methods. For these explanations to be- come meaningful in the classroom, it was crucially important that the stu- dents explain their multidigit adding or subtracting methods using the mean- ingful words in the middle pedagogical triangle of Figure 5-2 (e.g., âthree

229 MATHEMATICAL UNDERSTANDING: AN INTRODUCTION Drawings for Jackieâs and Drawing for âShow All Totalsâ Method Juanâs Addition Methods 100 10 100 10 Jackie Juan 1 68 68 68 + 56 + 56 + 56 1 110 124 124 14 124 110 + 14 100 + 20 + 4 Peterâs Ungrouping Method Mariaâs Add-Equal-Quantities Method 1 124 1 â 56 68 11 14 124 + 10 to + 10 to â 56 bottom top number number 11 tens + 14 68 110 + 14 FIGURE 5-1 tens six onesâ), as well as the usual math words (e.g., âthirty-sixâ). It is through such extended connected explanations and use of the quantity words âtensâ and âonesâ that the students in the Childrenâs Math Worlds Project came to explain their methods. Their explanations did not begin that way, and the students did not spontaneously use the meaningful language when describing their methods. The teacher needed to model the language and help students use it in their descriptions. More-advanced students also helped less-advanced students learn by modeling, asking questions, and helping others form more complete descriptions. Initially in the Childrenâs Math Worlds Project, all students made con- ceptual support drawings such as those in Figure 5-1. They explicitly linked these drawings to their written methods during explanations. Such drawings linked to the numerical methods facilitated understanding, accuracy, com- munication, and helping. Students stopped making drawings when they were no longer needed (this varied across students by months). Eventually, most students applied numerical methods without drawings, but these numerical

230 Everyday Formal experiential Classroom Referential and Representational Supports school informal math knowledge: knowledge: meaningful words, notations, methods, drawings words and words quantities in notations the real world methods pennies dimes pennies Meaningful Math Pedagogical Drawing RealâWorld Referent (Model) Referent RealâWorld RealâWorld Meaningful Meaningful Math Math Words Notation Pedagogical Pedagogical Words Notation Words Notation thirty-six 3 dimes 6 pennies $.36 36 thirty-six cents 36¢ three tens six ones tens ones or three groups of ten and six loose ones 3 6 T O 3 6 3D 6P 30 6 D P 3 6 36 FIGURE 5-2

231 MATHEMATICAL UNDERSTANDING: AN INTRODUCTION methods then carried for the members of the classroom the meanings from the conceptual support drawings. If errors crept in, students were asked to think about (or make) a drawing and most errors were then self-corrected. Designing Bridging Instructional Activities The first two features of instruction discussed above provide opportuni- ties for students to use their own strategies and to make their thinking visible so it can be built on, revised, and made more formal. This third strategy is more proactive. Research has uncovered common student preconceptions and points of difficulty with learning new mathematical concepts that can be addressed preemptively with carefully designed instructional activities. This kind of bridging activity is used in the Childrenâs Math Worlds curriculum to help students relate their everyday, experiential, informal un- derstanding of money to the formal school concepts of multidigit numbers. Real-world money is confusing for many students (e.g., dimes are smaller than pennies but are worth 10 times as much). Also, the formal school math number words and notations are abstract and potentially misleading (e.g., 36 looks like a 3 and a 6, not like 30 and 6) and need to be linked to visual quantities of tens and ones to become meaningful. Fuson designed concep- tual âsupportsâ into the curriculum to bridge the two. The middle portion of Figure 5-2 shows an example of the supports that were used to help stu- dents build meaning. A teacher or curriculum designer can make a frame- work like that of Figure 5-2 for any math domain by selecting those concep- tual supports that will help students make links among the math words, written notations, and quantities in that domain. Identifying real-world contexts whose features help direct studentsâ at- tention and thinking in mathematically productive ways is particularly help- ful in building conceptual bridges between studentsâ informal experiences and the new formal mathematics they are learning. Examples of such bridg- ing contexts are a key feature of each of the three chapters that follow. PRINCIPLE #2: UNDERSTANDING REQUIRES FACTUAL KNOWLEDGE AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS The second principle of How People Learn suggests the importance of both conceptual understanding and procedural fluency, as well as an effec- tive organization of knowledgeâin this case one that facilitates strategy development and adaptive reasoning. It would be difficult to name a disci- pline in which the approach to achieving this goal is more hotly debated than mathematics. Recognition of the weakness in the conceptual under-

232 HOW STUDENTS LEARN: MATHEMATICS IN THE CLASSROOM standing of students in the United States has resulted in increasing attention to the problems involved in teaching mathematics as a set of procedural competences.14 At the same time, students with too little knowledge of pro- cedures do not become competent and efficient problem solvers. When in- struction places too little emphasis on factual and procedural knowledge, the problem is not solved; it is only changed. Both are clearly critical. Equally important, procedural knowledge and conceptual understand- ings must be closely linked. As the mathematics confronted by students becomes more complex through the school years, new knowledge and com- petencies require that those already mastered be brought to bear. Box 1-6 in Chapter 1, for example, describes a set of links in procedural and conceptual knowledge required to support the ability to do multidigit subtraction with regroupingâa topic encountered relatively early in elementary school. By the time a student begins algebra years later, the network of knowledge must include many new concepts and procedures (including those for ratio- nal number) that must be effectively linked and available to support new algebraic understandings. The teacherâs challenge, then, is to help students build and consolidate prerequisite competencies, understand new concepts in depth, and organize both concepts and competencies in a network of knowledge. Furthermore, teachers must provide sustained and then increas- ingly spaced opportunities to consolidate new understandings and proce- dures. In mathematics, such networks of knowledge often are organized as learning paths from informal concrete methods to abbreviated, more gen- eral, and more abstract methods. Discussing multiple methods in the class- roomâdrawing attention to why different methods work and to the relative efficiency and reliability of eachâcan help provide a conceptual ladder that helps students move in a connected way from where they are to a more efficient and abstract approach. Students also can adopt or adapt an inter- mediate method with which they might feel more comfortable. Teachers can help students move at least to intermediate âgood-enoughâ methods that can be understood and explained. Box 5-4 describes such a learning path for single-digit addition and subtraction that is seen worldwide. Teachers in some countries support students in moving through this learning path. Developing Mathematical Proficiency Developing mathematical proficiency requires that students master both the concepts and procedural skills needed to reason and solve problems effectively in a particular domain. Deciding which advanced methods all students should learn to attain proficiency is a policy matter involving judg- ments about how to use scarce instructional time. For example, the level 2 counting-on methods in Box 5-4 may be considered âgood-enoughâ meth-

233 MATHEMATICAL UNDERSTANDING: AN INTRODUCTION ods; they are general, rapid, and sufficiently accurate that valuable school time might better be spent on topics other than mastery of the whole net- work of knowledge required for carrying out the level 3 methods. Decisions about which methods to teach must also take into account that some meth- ods are clearer conceptually and procedurally than the multidigit methods usually taught in the United States (see Box 5-5). The National Research Councilâs Adding It Up reviews these and other accessible algorithms in other domains. This view of mathematics as involving different methods does not imply that a teacher or curriculum must teach multiple methods for every domain. However, alternative methods will frequently arise in a classroom, either because students bring them from home (e.g., Mariaâs add-equal-quantities subtraction method, widely taught in other countries) or because students think differently about many mathematical problems. Frequently there are viable alternative methods for solving a problem, and discussing the advan- tages and disadvantages of each can facilitate flexibility and deep under- standing of the mathematics involved. In some countries, teachers empha- size multiple solution methods and purposely give students problems that are conducive to such solutions, and students solve a problem in more than one way. However, the less-advanced students in a classroom also need to be considered. It can be helpful for either a curriculum or teacher or such less- advanced students to select an accessible method that can be understood and is efficient enough for the future, and for these students to concentrate on learning that method and being able to explain it. Teachers in some countries do this while also facilitating problem solving with alternative methods. Overall, knowing about student learning paths and knowledge networks helps teachers direct math talk along productive lines toward valued knowl- edge networks. Research in mathematics learning has uncovered important information on a number of typical learning paths and knowledge networks involved in acquiring knowledge about a variety of concepts in mathematics (see the next three chapters for examples). Instruction to Support Mathematical Proficiency To teach in a way that supports both conceptual understanding and procedural fluency requires that the primary concepts underlying an area of mathematics be clear to the teacher or become clear during the process of teaching for mathematical proficiency. Because mathematics has tradition- ally been taught with an emphasis on procedure, adults who were taught this way may initially have difficulty identifying or using the core conceptual understandings in a mathematics domain.

234 HOW STUDENTS LEARN: MATHEMATICS IN THE CLASSROOM BOX 5-4 A Learning Path from Childrenâs Math Worlds for Single-Digit Addition and Subtraction Children around the world pass through three levels of increasing sophis- tication in methods of single-digit addition and subtraction. The first level is direct modeling by counting all of the objects at each step (counting all or taking away). Students can be helped to move rapidly from this first level to counting on, in which counting begins with one addend. For ex- ample, 8 + 6 is not solved by counting from 1 to 14 (counting all), but by counting on 6 from 8: counting 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 while keeping track of the 6 counted on. For subtraction, Childrenâs Math Worlds does what is common in many countries: it helps students see subtraction as involving a mystery addend. Students then solve a subtraction problem by counting on from the known addend to the known total. Earlier we saw how Maria solved 14 - 6 by counting up from 6 to 14, raising 8 fingers while doing so to find that 6 plus 8 more is 14. Many students in the United States instead follow a learning path that moves from drawing little sticks or circles for all of the objects and crossing some out (e.g., drawing 14 sticks, crossing out 6, and counting the rest) to counting down (14, 13, 12, 11, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6). But counting down is difficult and error prone. When first or second graders are helped to move to a different learning path that solves sub- traction problems by forward methods, such as counting on or adding on over 10 (see below), subtraction becomes as easy as addition. For many students, this is very empowering. The third level of single-digit addition and subtraction is exemplified by Peter in the vignette in Box 5-2. At this level, students can chunk The approaches in the three chapters that follow identify the central conceptual structures in several areas of mathematics. The areas of focusâ whole number, rational number, and functionsâwere identified by Case and his colleagues as requiring major conceptual shifts. In the first, students are required to master the concept of quantity; in the second, the concept of proportion and relative number; and in the third, the concept of dependence in quantitative relationships. Each of these understandings requires that a supporting set of concepts and procedural abilities be put in place. The extensive research done by Griffin and Case on whole number, by Case and Moss on rational number, and by Case and Kalchman on functions provides a strong foundation for identifying the major conceptual challenges students

235 MATHEMATICAL UNDERSTANDING: AN INTRODUCTION numbers and relate these chunks. The chunking enables them to carry out make-a-ten methods: they give part of one number to the other num- ber to make a ten. These methods are taught in many countries. They are very helpful in multidigit addition and subtraction because a number found in this way is already thought of as 1 ten and some ones. For example, for 8 + 6, 6 gives 2 to 8 to make 10, leaving 4 in the 6, so 10 + 4 = 14. Solving 14 â 8 is done similarly: with 8, how many make 10 (2), plus the 4 in 14, so the answer is 6. These make-a-ten methods demonstrate the learning paths and network of knowledge required for advanced solution meth- ods. Children may also use a âdoublesâ strategy for some problemsâ e.g., 7 + 6 = 6 + 6 + 1= 12 + 1 = 13âbecause the doubles (for example, 6 + 6 or 8 + 8) are easy to learn. The make-a-ten methods illustrate the importance of a network of knowledge. Students must master three kinds of knowledge to be able to carry out a make-a-ten method fluently: they must (1) for each number below 10, know how much more makes 10; (2) break up any number below 10 into all possible pairs of parts (because 9 + 6 requires knowing 6 = 1 + 5, but 8 + 6 requires knowing 6 = 2 + 4, etc.); and (3) know 10 + 1 = 11, 10 + 2 = 12, 10 + 3 = 13, etc., rapidly without counting. Note that particular methods may be more or less easy for learners from different backgrounds. For example, the make-a-ten methods are easier for East Asian students, whose language says, âTen plus one is ten one, ten plus two is ten two,â than for English-speaking students, whose language says, âTen plus one is eleven, ten plus two is twelve, etc.â face in mastering these areas. This research program traced developmental/ experiential changes in childrenâs thinking as they engaged with innovative curriculum. In each area of focus, instructional approaches were developed that enable teachers to help children move through learning paths in pro- ductive ways. In doing so, teachers often find that they also build a more extensive knowledge network. As teachers guide a class through learning paths, a balance must be maintained between learner-centered and knowledge-centered needs. The learning path of the class must also continually relate to individual learner knowledge. Box 5-6 outlines two frameworks that can facilitate such balance.

236 HOW STUDENTS LEARN: MATHEMATICS IN THE CLASSROOM Accessible Algorithms BOX 5-5 In over a decade of working with a range of urban and suburban classrooms in the Childrenâs Math Worlds Project, we found that one multidigit addition method and one multidigit subtraction method were accessible to all students. The students easily learned, understood, and remembered these methods and learned to draw quantities for and explain them. Both methods are modifications of the usual U.S. methods. The addition method is the write-new-groups-below method, in which the new 1 ten or 1 hundred, etc., is written below the column on the line rather than above the column (see Jackieâs method in Figure 5-1). In the subtraction fix- everything-first method, every column in the top number that needs ungrouping is ungrouped (in any order), and then the subtracting in every column is done (in any order). Because this method can be done from either direction and is only a minor modification of the common U.S. methods, learning-disabled and special-needs students find it especially accessible. Both of these methods stimulate productive discussions in class because they are easily related to the usual U.S. methods that are likely to be brought to class by other students. PRINCIPLE #3: A METACOGNITIVE APPROACH ENABLES STUDENT SELF-MONITORING Learning about oneself as a learner, thinker, and problem solver is an important aspect of metacognition (see Chapter 1). In the area of mathemat- ics, as noted earlier, many people who take mathematics courses âlearnâ that âthey are not mathematical.â This is an unintended, highly unfortunate, con- sequence of some approaches to teaching mathematics. It is a consequence that can influence people for a lifetime because they continue to avoid anything mathematical, which in turn ensures that their belief about being ânonmathematicalâ is true.15 An article written in 1940 by Charles Gragg, entitled âBecause Wisdom Canât be Told,â is relevant to issues of metacognition and mathematics learn- ing. Gragg begins with the following quotation from Balzac: So he had grown rich at last, and thought to transmit to his only son all the cut-and-dried experience which he himself had purchased at the price of his lost illusions; a noble last illusion of age. Except for the part about growing rich, Balzacâs ideas fit many peoplesâ experiences quite well. In our roles as parents, friends, supervisors, and professional educators, we frequently attempt to prepare people for the future by imparting the wisdom gleaned from our own experiences. Some-

237 MATHEMATICAL UNDERSTANDING: AN INTRODUCTION BOX 5-6 Supporting Student and Teacher Learning Through a Classroom Discourse Community Eliciting and then building on and using studentsâ mathematical thinking can be challenging. Yet recent research indicates that teachers can move their students through increasingly productive levels of classroom discourse. Hufferd-Ackles and colleagues16 describe four levels of a âmath-talk learning community,â beginning with a traditional, teacher-directed format in which the teacher asks short-answer questions, and student responses are directed to the teacher. At the next level, âgetting started,â the teacher begins to pursue and assess studentsâ mathemati- cal thinking, focusing less on answers alone. In response, students provide brief descriptions of their thinking. The third level is called âbuilding.â At this point the teacher elicits and students respond with fuller descriptions of their thinking, and multiple methods are volunteered. The teacher also facilitates student-to-student talk about mathematics. The final level is âmath-talk.â Here students share re- sponsibility for discourse with the teacher, justifying their own ideas and asking questions of and helping other students. Key shifts in teacher practice that support a class moving through these lev- els include asking questions that focus on mathematical thinking rather than just on answers, probing extensively for student thinking, modeling and expanding on explanations when necessary, fading physically from the center of the classroom discourse (e.g., moving to the back of the classroom), and coaching students in their participatory roles in the discourse (âEveryone have a thinker question ready.â). Related research indicates that when building a successful classroom dis- course community, it is important to balance the process of discourse, that is, the ways in which student ideas are elicited, with the content of discourse, the sub- stance of the ideas that are discussed. In other words, how does a teacher ensure both that class discussions provide sufficient space for students to share their ideas and that discussions are mathematically productive? Sherin17 describes one model for doing so whereby class discussions begin with a focus on âidea genera- tion,â in which many student ideas are solicited. Next, discussion moves into a âcomparison and evaluationâ phase, in which the class looks more closely at the ideas that have been raised, but no new ideas are raised. The teacher then âfiltersâ ideas for the class, highlighting a subset of ideas for further pursuit. In this way, student ideas are valued throughout discussion, but the teacher also plays a role in determining the extent to which specific math- ematical ideas are considered in detail. A class may proceed through several cycles of these three phases in a single discussion.