An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Syst (Basingstoke)

- v.7(1); 2018

A systematic literature review of operational research methods for modelling patient flow and outcomes within community healthcare and other settings

Ryan palmer.

a Clinical Operational Research Unit, Department of Mathematics, University College London, London, UK

Naomi J. Fulop

b Department of Applied Health Research, University College London, London, UK

Martin Utley

An ambition of healthcare policy has been to move more acute services into community settings. This systematic literature review presents analysis of published operational research methods for modelling patient flow within community healthcare, and for modelling the combination of patient flow and outcomes in all settings. Assessed for inclusion at three levels – with the references from included papers also assessed – 25 “Patient flow within community care”, 23 “Patient flow and outcomes” papers and 5 papers within the intersection are included for review. Comparisons are made between each paper’s setting, definition of states, factors considered to influence flow, output measures and implementation of results. Common complexities and characteristics of community service models are discussed with directions for future work suggested. We found that in developing patient flow models for community services that use outcomes, transplant waiting list may have transferable benefits.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, an ambition of healthcare policy has been to deliver more care in the community by moving acute services closer to patient homes (ENGLand NHS, 2014 ; Munton et al., 2011 ). This is often motivated by assumed benefits such as reduced healthcare costs, improved access to services, improved quality of care, a greater ability to cope with an increasing number of patients, and improved operational performance in relation to patient health and time (Munton et al., 2011 ).

A scoping review analysed the evidence regarding the impact that shifting services may have on the quality and efficiency of care (Sibbald, McDonald, & Roland, 2007 ). It found that under certain conditions moving services into the community may help to increase patient access and reduce waiting times. Across multiple types of care, however (minor surgery, care of chronic disease, outpatient services and GP access to diagnostic tests), the quality of care and health outcomes may be compromised if a patient requires competencies – such as minor surgery – that are considered beyond those of the average primary care clinician. On the evidence for the effect on the monetary cost of services, Sibbald et al. ( 2007 ) stated that it was generally expected that community care would be cheaper when offset against acute savings; however, increases in the overall volume of care (Hensher, 1997 ) and reductions in economies of scale (Powell, 2002 ; Whitten et al., 2002 ) may lead to an increase in overall cost in certain instances.

Considering the questions that remain over the impact of shifting services from acute to community sector, it is important to understand how community services may be best delivered. This is where applying operational research (OR) methods to community care services can contribute. For instance, services may be modelled to evaluate how goals, such as better patient access and improved outcomes, may be achieved considering constraints and objectives, such as fixed capacity or reducing operational costs. An example of one such method is patient flow modelling, the focus of this review.

2. Modelling patient flow

In a model of flow, the relevant system is viewed as comprising a set of distinct compartments or states, through which continuous matter or discrete entities move. Within healthcare applications, the entities of interest are commonly patients (although some applications may consider blood samples or forms of information). Côté ( 2000 ) identified two viewpoints from which patient flow has been understood, an operational perspective and, less commonly, a clinical perspective. From an operational perspective, the states that patients enter, leave and move between are defined by clinical and administrative activities and interactions with the care system, such as consulting a physician or being on the waiting list for surgery. Such states may be each associated with a specific care setting or some other form of resource but this need not be the case. In the clinical perspective of patient flow, the states that patients enter, leave and move between are defined by some aspect of the patient’s health, for instance by whether the patient has symptomatic heart disease, or the clinical stage of a patient’s tumour. A more generic view is that the states within a flow model can represent any amalgam of activity, location, patient health and changeable demographics, say, patient age (Utley, Gallivan, Pagel, & Richards, 2009 ). A key characteristic is that the set of states and the set of transitions between states comprise a complete description of the system as modelled.

Within the modelling process, characteristics of the patient population and of the states of the system are incorporated to evaluate how such factors influence flow. Examples of the former include patient demographics or healthcare requirements, whilst for the latter, capacity constraints relating to staffing, resources, time and budgets may be considered. The characteristics used depend upon the modelled system, modelling technique and questions being addressed. Considering these, the performance of a system may be evaluated through the use of output measures such as resource utilisation (Cochran & Roche, 2009 ), average physician overtime (Cayirli, Veral, & Rosen, 2006 ) and patient waiting times (Zhang, Berman, & Verter, 2009 ).The output measures calculated within an application depends upon the modelled problem, modelling technique and the factors that are consider to influence flow.

Within acute care settings patient flow modelling has been applied to various scenarios – see Bhattacharjee and Ray ( 2014 ). There are also several publications for community care settings; however, no published literature review exists. This systematic literature review was undertaken to gather and analyse two types of patient flow modelling literature relevant for community services. The first were publications that present models of operational patient flow within a community healthcare context, denoted as “Patient flow within community care”. The second were publications that present combinations of patient outcomes and patient flow modelling in any setting, denoted as “Patient flow and outcomes”. Incorporating patient outcomes within the patient flow modelling process is increasingly pertinent within community healthcare. Patient outcomes are used not only to track, monitor and evaluate patient health throughout a care pathway, but also assess the quality of care and inform improvement. The justification for increasing the provision of community care includes improved patient outcomes and satisfaction, thus in combining outcomes and patient flow modelling new and helpful metrics may be developed to evaluate this assertion. Furthermore, such methods help to inform the organisation of healthcare services according to operational capability and the clinical impact on the patient population, unifying two main concerns of providers and patients with a single modelling framework. No specific setting was sought in the “Patient flow and outcomes” to find potentially transferable knowledge and methods for community settings.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first literature review focussing on OR methods for modelling patient flow applied to community healthcare services and the first to review methods for modelling patient flow and outcomes in combination. This review has been undertaken as part of a project in which OR methods will be developed that combine patient flow modelling and patient outcomes for community care services. The aim of this review was thus twofold. Firstly, to explore different applications of OR methods to community services. Secondly, to understand how patient outcomes have been previously incorporated within flow models. In the discussion section of this paper, we suggest directions for the future of patient flow modelling applied to community care.

3. Method of review

We conducted a configurative systematic literature review (Gough, Thomas, & Oliver, 2012 ), an approach intended to gather and analyse a heterogeneous literature with the aim of identifying patterns and developing new concepts. Two searches were performed to find peer-reviewed operational research (OR) publications, relating to “Patient flow within community care” and “Patient flow and outcomes” as previously detailed. We considered all papers published in English before November 2016 with no lower bound publication date, and searched the electronic databases Scopus, PubMed and Web of Science. Using a combination of the search terms listed in Table Table1, 1 , to find papers related to “Patient flow within community care” we sought records with at least one operational research method term in the article title, journal title or keywords AND at least one patient flow term in the article title, journal title, keywords or abstract AND at least one community health setting term in the article title, journal title, keywords or abstract. Likewise, to fi papers related to “Patient flow and outcomes” we sought records with at least operational research method term in the article title, journal title or keywords AND at least one patient fl term in the article title, journal title, keywords or abstract AND at least one outcome term in the article title, journal title, keywords or abstract.

Initial sets of search terms relating to community healthcare settings and OR methods were informed by Hulshof, Kortbeek, Boucherie, Hans, and Bakker ( 2012 ). Synonyms were added to these lists prior to the preliminary searches for papers. For patient flow terms and outcome terms, we formed initial lists that we considered relevant. The first batch of papers found using these lists was examined for further applicable search terms. The initial search terms are highlighted in bold in Table Table1 1 .

Papers obtained from the final searches were assessed for inclusion for full review at three levels. If a paper was not a literature review it was required to meet all the inclusion and none of the exclusion criteria outlined in Table Table2. 2 . For each included paper, references were assessed using the same inclusion and exclusion process to find any papers that may have been missed in the searches.

Literature reviews were included at each level if they were concerned with OR methods for evaluating patient flow; focussed on operational processes of healthcare and no equivalent systematic review was included. Within the “Patient flow within community care” literature, review pieces were included if they focussed on community settings; whilst within the “Patient flow and outcome” literature, review pieces were included if they focussed on uses of patient outcomes in modelling processes.

Data tables were constructed to present key characteristics of the literature and shape our analysis. Informed by the initial readings, papers were grouped into five categories based on analytical method with five key characteristics of each model extracted and tabulated for comparison, given in Tables Tables4, 4 , ,5 5 and and6 6 .

4. Results of literature searches

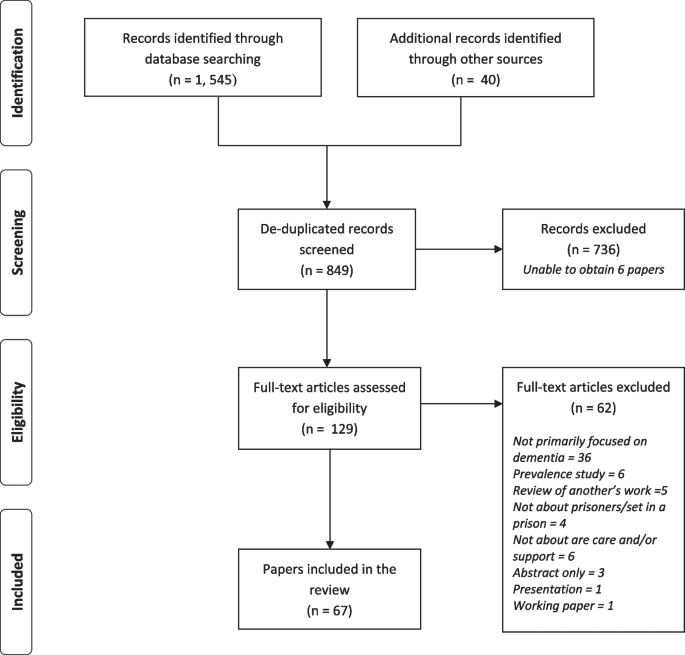

The results of the final searches for and selection of papers are shown in an adapted PRISMA flow chart (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009 ), Figure Figure1. 1 . Reasons for the exclusion of texts at full text assessment are shown in Table Table3 3 .

Flow chart of literature search results – 53 papers were eligible for review.

Overall 25 “Patient flow within community” papers, 23 “Patient flow and outcomes” papers and 5 papers in the intersection entered the full review. An analysis of this literature is now presented with in the intersection of the two searches included in the “Patient flow within community care” section.

5. Analysis

5.1. papers found within the “patient flow within community care” search, 5.1.1. markovian models.

A Markovian model views flow within a system as a random process within which the future movement of an entity is dependent only upon its present state and is independent of time spent in that state or the pathway it previously travelled. Whilst systems of healthcare are not truly Markovian, in using these methods, a steady-state analysis of a system may be formulated from which meaningful long-run averages of system metrics can be calculated.

The settings of these publications, presented in Tables Tables4 4 and and5, 5 , include residential mental healthcare (Koizumi, Kuno, & Smith, 2005 ), post-hospital care pathways (Kucukyazici, Verter, & Mayo, 2011 ), community services and hospital care (Song, Chen, & Wang, 2012 ) and community-based services for elderly patients with diabetes (Chao et al., 2014 ).

Within these models, states were defined as different services or stages of care. Kucukyazici et al. ( 2011 ) and Chao et al. ( 2014 ) also defined states of post-care outcomes. In the former these included patient mortality, admission to long-term care and re-hospitalisation, whilst the latter defined states of subsequent health progression.

Two main factors were considered to influence flow within these models: the effect of congestive blocking caused by limited waiting space (Koizumi et al., 2005 ; Song et al., 2012 ) and the diversity of patients: demographics (Kucukyazici et al., 2011 ) and severity of disease (Chao et al., 2014 ). In considering blocking, flow was influenced by the available capacity and average occupancy of each service.

The output measures were queue lengths and wait times for each state – with and without congestive blocking (Koizumi et al., 2005 ; Song et al., 2012 ) and the probability that patients would be in a given post-care outcome state (Chao et al., 2014 ; Kucukyazici et al., 2011 ).

An analysis of different scenarios was undertaken in both latter papers to identify how alternative treatments may help improve post-care outcomes.

None of the papers explicitly reported implementation of their results. We consider implementation to include any action to share or use the results of the work within the modelled setting.

5.1.2. Non-Markovian steady-state models

An optimisation approach for resource allocation by Bretthauer and Côté ( 1998 ) defined states as services within specified pathways. The aim was to minimise overall costs whilst maintaining a certain level of care as measured by metrics such as desired waiting. Within the model, flow was influenced by capacity constraints, such as number of beds.

5.1.3. System dynamics analysis

System dynamics is a modelling method whereby computer simulations of complex systems can be built and used to design more effective policies and organisations (Sterman, 2000 ). Two applications were found, modelling systems of markedly different sizes. Taylor, Dangerfield, and Le Grand ( 2005 ) evaluated the uses of community care services to bolster acute cardiac services whilst Wolstenholme ( 1999 ) evaluated the UK’s NHS.

States were defined as community or acute services (Taylor et al., 2005 ) and different sectors of care, namely primary, acute, NHS continuing care and community care (Wolstenholme, 1999 ).

Capacity and rate variables, such as waiting list size and clinical referral guidelines were considered to influence flow within both models. A feedback mechanism was used by Taylor et al. ( 2005 ) to evaluate how changes in these variables may stimulate and effect demand.

The main metrics of these models related to demand and access, namely waiting times and patient activity – for example, long-run use of services and length of queues (Wolstenholme, 1999 ). In both papers, a scenario analysis was performed to evaluate how changes within the model affected its output.

Wolstenholme ( 1999 ) reported that some findings were shared with NHS staff.

5.1.4. Analytical methods including time dependence

Applications of analytical methods with time dependence included specialist clinics (Deo, Iravani, Jiang, Smilowitz, & Samuelson, 2013 ; Izady, 2015 ), care after discharge from an acute stroke unit (Garg, McClean, Barton, Meenan, & Fullerton, 2012 ), long-term institutional care (Xie, Chaussalet, & Millard, 2005 , 2006 ), community mental health services (Pagel, Richards, & Utley, 2012 ; Utley et al., 2009 ) and home/community care in British Columbia (Hare, Alimadad, Dodd, Ferguson, & Rutherford, 2009 ).

The state definitions within these models related to stages of care/different services (Garg et al., 2012 ; Hare et al., 2009 ; Pagel et al., 2012 ; Utley et al., 2009 ; Xie et al., 2005 , 2006 ); “waiting” or “in service” (Deo et al., 2013 ; Izady, 2015 ) and health states – in particular stages of health progression (Deo et al., 2013 ) or post-care outcomes (Garg et al., 2012 ).

The factors considered to influence flow included capacity of services (Izady, 2015 ; Pagel et al., 2012 ); patient demographics and care requirements (Garg et al., 2012 ; Hare et al., 2009 ; Xie et al., 2005 , 2006 ); patient health between recurrent appointments (Deo et al., 2013 ) and the length of time in which a person occupied a state (Utley et al., 2009 ).

Commonly, the system metrics used in these papers related to the time a patient spent interacting with parts of the system – such as expected length of stay, waiting times and time spent in states. Garg et al. ( 2012 ) calculated the daily cost of care and likely post-care outcome states for patients of different demographic groups. Pagel et al. ( 2012 ) and Deo et al. ( 2013 ) identified optimal capacity allocations subject to desired levels of queue lengths and wait times, and impact on patient health, respectively. Hare et al. ( 2009 ) evaluated the possible future demand for services under different scenarios and situations.

Of these applications, Pagel et al. ( 2012 ) and Utley et al. ( 2009 ) reported steps towards implementation. In the former, a software tool was created, whilst in the latter the fi dings of the model were shared with key stakeholders. Hare et al. ( 2009 ) also noted the use of their model for care planning within their given setting.

5.1.5. Simulation methods

The settings of these papers included long-term care (Cardoso, Oliveira, & Barbosa-PóVoa, 2012 ; Zhang & Puterman, 2013 ; Zhang, Puterman, Nelson, & Atkins, 2012 ), outpatient services (Chand, Moskowitz, Norris, Shade, & Willis, 2009 ; Clague et al., 1997 ; Matta & Patterson, 2007 ; Pan, Zhang, Kon, Wai, & Ang, 2015 ; Ponis, Delis, Gayialis, Kasimatis, & Tan, 2013 ; Swisher & Jacobson, 2002 ), primary care and ambulatory clinics (Fialho, Oliveira, & Sa, 2011 ; Santibáñez, Chow, French, Puterman, & Tyldesley, 2009 ; Shi, Peng, & Erdem, 2014 ) and provisions of integrated acute and community services (Bayer, Petsoulas, Cox, Honeyman, & Barlow, 2010 ; Patrick, Nelson, & Lane, 2015 ; Qiu, Song, & Liu, 2016 ).

States were defined as different services, clinics or sectors of care; or healthcare tasks within single clinics (Chand et al., 2009 ; Clague et al., 1997 ; Fialho et al., 2011 ; Santibáñez et al., 2009 ; Shi et al., 2014 ; Swisher & Jacobson, 2002 ). Chand et al. ( 2009 ) and Pan et al. ( 2015 ) modelled the flow of patient information alongside patient flow and thus defined states of information flow.

Factors considered to influence flow commonly included the healthcare requirements/demographics of patients (Chand et al., 2009 ; Clague et al., 1997 ; Fialho et al., 2011 ; Shi et al., 2014 ; Swisher & Jacobson, 2002 ), constrained capacity and rates of no show/reneging (Clague et al., 1997 ; Shi et al., 2014 ; Swisher & Jacobson, 2002 ). Bayer et al. ( 2010 ), Cardoso et al. ( 2012 ), Ponis et al. ( 2013 ), and Qiu et al. ( 2016 ) considered monetary influences such as budgetary constraints, cost of care and profitability. Chand et al. ( 2009 ) used the variability of time in completing care tasks.

Common metrics related to the time that a patient spent waiting in a state or in the system as whole. Optimised capacity levels relating to key performance measures were also widely considered (Ponis et al., 2013 ; Zhang & Puterman, 2013 ; Zhang et al., 2012 ). Matta and Patterson ( 2007 ) calculated a single system metric – an aggregate of multiple performance measures stratified by day, facility routing and patient group. This single metric was formed of measures such as average throughput, average system time and average queue time.

The implementation of suggested changes was recorded in several applications (Chand et al., 2009 ; Clague et al., 1997 ; Matta & Patterson, 2007 ; Pan et al., 2015 ; Santibáñez et al., 2009 ; Shi et al., 2014 ; Zhang et al., 2012 ).

5.2. Papers found within the “Patient flow and outcomes” search

5.2.1. markovian models.

As outlined in Tables Tables5 5 and and6, 6 , seven publications used Markovian methods and outcomes, two of which were also included within the “Patient flow within community care” section. The five new papers modelled transplant waiting lists (Drekic, Stanford, Woolford, & McAlister, 2015 ; Wang, 2004 ; Zenios, 1999 ), intensive care units (Shmueli, Sprung, & Kaplan, 2003 ) and emergency care (Kim & Kim, 2015 ).

In these models, states related to whether patients were “waiting” or had obtained a service/transplant. Drekic et al. ( 2015 ) defined patient priority states to reflect health deterioration.

The factors that influenced flow related to patient health with groups or states used to assign priorities (Drekic et al., 2015 ; Wang, 2004 ) or, represent patient demographics and care requirements. The reneging characteristics of different groups of patients were also considered in each transplant paper with patients modelled as leaving the waiting list due to death or for other reasons. (Drekic et al., 2015 ; Zenios, 1999 ).

The output measures of these papers commonly related to the wait time faced by patients. Other metrics included the probability of reneging per patient group (Drekic et al., 2015 ) and the expected number of deaths for waiting patients (Wang, 2004 ) or lives saved by an admission policy (Shmueli et al., 2003 ). Zenios ( 1999 ) calculated the average time spent in the system and in the queue for each demographic group, and the fraction of patients from each group who received a transplant.

None of the papers reported an implementation of their results within their care setting.

5.2.2. Non-Markovian steady-state models

The modelled settings and applications included an emergency department (Cochran & Roche, 2009 ) and two waiting lists, one for hospital care (Goddard & Tavakoli, 2008 ), the other for transplant patients (Stanford, Lee, Chandok, & McAlister, 2014 ). States were defined as stages of hospital care and as “waiting” or “in service”.

The factors considered to influence flow were patient group and seasonality (Cochran & Roche, 2009 ) and resource availability and patient health (Goddard & Tavakoli, 2008 ; Stanford et al., 2014 ). Each model used metrics relating to the amount of time a patient spent within parts of the system.

Cochran and Roche ( 2009 ) reported an implementation of their results with software developed and made available for clinicians and care managers. Feedback and educational sessions were also organised to help key stakeholders to understand the work.

5.2.3. System dynamics analysis

Diaz, Behr, Kumar, and Britton ( 2015 ) evaluated patient flow between states of acute care and home care for patients with chronic disease. The factors considered to influence flow related to patient groups based on their care requirements and whether they possessed insurance. Congestion and capacity of resources were also considered. A scenario analysis was performed to evaluate the impact of different patient routes and resource allocations on the level of demand for services and the cost of providing care.

5.2.4. Analytical methods including time dependence

Nine papers were found, two of which were included in the “Patient flow within community care” section. Of the seven remaining, the settings were care for chronic diseases (Deo, Rajaram, Rath, Karmarkar, & Goetz, 2015 ), two intensive care models (Chan, Farias, Bambos, & Escobar, 2012 ; Liquet, Timsit, & Rondeau, 2012 ), two radiotherapy models (Li, Geng, & Xie, 2015 ; Thomsen & Nørrevang, 2009 ) and two transplant waiting lists (Alagoz, Maillart, Schaefer, & Roberts, 2004 ; Zenios & Wein, 2000 ).

States were defined as “in service” or “waiting”, different services or different appointment slots (Li et al., 2015 ; Thomsen & Nørrevang, 2009 ). Alagoz et al. ( 2004 ), Liquet et al. ( 2012 ), and Deo et al. ( 2015 ) also defined multiple health states.

The factors considered to influence flow were commonly related to differences within the patient population pertaining to health (Alagoz et al., 2004 ; Deo et al., 2015 ); care requirements or demographic/health-related groups (Zenios & Wein, 2000 ) and the availability of resources such as organs (Alagoz et al., 2004 ; Zenios & Wein, 2000 ) or appointment slots (Deo et al., 2015 ; Li et al., 2015 ; Thomsen & Nørrevang, 2009 ).

Common metrics used by these methods focussed on the amount of time a patient spent waiting for a service – for example, the optimal timing of appointments (Deo et al., 2015 ) or transplants (Alagoz et al., 2004 ) subject to changes in patient health. Zenios and Wein ( 2000 ) calculated output measures for different groups of patients to evaluate equity within the process of organ allocation. Forecasts of capacity requirements and optimal allocation of resources based on patient groups were also common.

Thomsen and Nørrevang ( 2009 ) and Deo et al. ( 2015 ) reported that some of their suggestions had influenced decision-making.

5.2.5. Simulation methods

Eight applications were found with one included in the “Patient flow within community care” (Matta & Patterson, 2007 ). Of the seven remaining, applications included a cardiac catheterisation clinic (Gupta et al., 2007 ), three transplant waiting lists (McLean & Jardine, 2005 ; Shechter et al., 2005 ; Yuan, Gafni, Russell, & Ludwin, 1994 ), an evaluation of an emergency department (Panayiotopoulos & Vassilacopoulos, 1984 ), neonatal intensive care (Derienzo et al., 2016 ) and a healthcare resource allocation model (van Zon & Kommer, 1999 ).

Within these papers, states were defined as healthcare tasks (Gupta et al., 2007 ; van Zon & Kommer, 1999 ), number of beds and “waiting” or “in service”.

The factors considered to influence flow within these models included demographics/care requirements (Gupta et al., 2007 ; McLean & Jardine, 2005 ; Shechter et al., 2005 ; van Zon & Kommer, 1999 ); the health, mortality and survival rates of patients (McLean & Jardine, 2005 ; Shechter et al., 2005 ; van Zon & Kommer, 1999 ) and resource capacity.

Several metrics were calculated within these methods, with the time patients spent interacting with or waiting within parts of the system a common measure. Other outputs of interest included capacity allocation (Derienzo et al., 2016 ; Gupta et al., 2007 ; Yuan et al., 1994 ); the cost of care, health benefits of service (van Zon & Kommer, 1999 ) and the expected survival rate of patients (McLean & Jardine, 2005 ; Shechter et al., 2005 ).

Panayiotopoulos and Vassilacopoulos ( 1984 ) and Gupta et al. ( 2007 ) both noted that some of their suggested changes had been implemented.

5.3. Summary of findings and discussion across literatures

Findings from across the literature will now be summarised and discussed, drawing together common themes and key characteristics as presented in Tables Tables4, 4 , ,5 5 and and6. 6 . In combination, we reviewed 53 papers presenting models of patient flow. 30 applied to community care services which included mental health services, physical health services, outpatient care and patient flow within acute and community settings. Furthermore, 32 applications used, in some form, either queue lengths or the amount of time that a patient spent within states as output measures. The next most common metrics were monetary costs in relation to patient use and the allocation of capacity-related resources.

Within the “Patient flow and community care” literature a range of flow characteristics were considered. For instance, patients access and arrivals to community services were modelled as unscheduled (e.g. Taylor et al., 2005 ), by appointment (e.g. Deo et al., 2013 , 2015 ), by external referral (e.g. Koizumi et al., 2005 ), or a mixture of the above (e.g. Chand et al., 2009 ; Song et al., 2012 ). Furthermore, multiple care interactions were modelled as either sequential visits to different services (e.g. Koizumi et al., 2005 ; Song et al., 2012 ) or as single visits where multiple tasks were carried out (e.g. Chand et al., 2009 ). In either instance patients were sometimes modelled as being able to recurrently visit the same service over time with some patients using the service more frequently (e.g. Deo et al., 2013 ; Shi et al., 2014 ).

Within the “Patient flow and outcome” literature, there were 10 models of transplant/waiting lists, 8 of community, ambulatory and outpatient services, 3 of emergency departments, 4 for intensive care, 2 for radiotherapy and 1 general model of resource allocation. Outcome measures were incorporated within the outputs of these models in three broad ways: (1) system metrics were stratified by outcome related groups; (2) variable patient or population level health was used as an objective or constraint within a model to influence resource allocation or (3) health outcomes – such as patient mortality or future use of care – were used as system metrics. Notably, 15 papers used patient groups to represent differing health/outcomes, whilst 13 papers incorporated variable health/outcome which could change during a course of care. By including variable health/outcome, a model’s output was informed by the effect of a care interaction, or absence of a care interaction, on patient outcomes and on the operation of the system.

Patient groups relating to health/outcome were used in models of each method and were commonly used in resource and service capacity allocations. Notably, their application within steady-state methods is limited since it is difficult to model differing group-dependent variables, such as service times, since the order of patients within these queues is unknown.

Variable health/outcome which could change during a course of care was commonly used within time-dependent methods. They were used to model the effect of care on a population where the modelled time period was large, such as stays with residential care or where multiple interactions were considered.

Across both literatures, queues could be categorised as either physical – constrained demand – or non-physical – unconstrained demand, as per Tables Tables4, 4 , ,5 5 and and6. 6 . Physical queues form when patients wait for service within a fixed physical space. Examples include, arrivals forming a queue within a clinic or emergency care (e.g. Chand et al., 2009 ; Santiba′n˜ ez et al., 2009 ; Shi et al., 2014 ) or when patients move between care interactions and immediately wait within another single physical location (e.g. Cochran & Roche, 2009 ; Xie et al., 2005 , 2006 ). When physical queues occur, the time a patient spends waiting for service is typically of the order of their expected service time. These queues are constrained and patient demand is modelled from the point when they physically arrive to the service.

Given these dynamics, the most common analysis of physical queues related to the daily operation of single services. Such models were used to gain insight into the delivery of care (e.g. flow between multiple treatments/consultations in a single visit). Studies of physical queues were carried out using each type of method. The choice of method depended on the desired insight, factors considered to influence flow and size of the system. Steady-state methods were sufficient if queue lengths and wait times were of primary concern. However, if variability in input parameters or periodic influences were important, time variable methods were more appropriate. These models typically focus on shorter time frames of care, therefore health/outcome groups were used within these models.

Alternatively, non-physical queues occur when patients may wait in any location away from the service such as their place of residence-e.g. when care is scheduled (Deo et al., 2013 ) or a patients wait is potentially long and unknown (Zenios & Wein, 2000 ). Non-physical queues represent unconstrained demand which begins from the point when a patient is referred to a service. A patient’s wait is therefore typically of an order larger than their expected service time. Such models are commonly used to model the demand and access at a system level.

The most common analysis of non-physical queues related to waiting lists and multiple uses of a single or multiple services. Studies of these scenarios were carried out using steady-state analysis or time-dependent methods. Due to the long-run nature of steady-state models these models were appropriate for such situations, especially when variability and differences within the patient population were negligible. In scenarios of scarce appointment or resource allocation, time variable methods were increasingly used. Within these models, variable health/outcome was widely considered due to the longer time frames of care, possible multiple interactions and the benefits stated previously.

It should be noted that this work is limited due to the difficulty of systematically reviewing this literature. In particular, we found two main difficulties. Firstly, these papers are published within a wide range of journals, some within healthcare journals, others in operational research (OR) journals, whilst a proportion was found within journals that were neither health-specific nor OR specific. Secondly, we found that patient flow is described and referred to in myriad ways within literature. No clear standards were found; thus, locating these papers was particularly difficult.

Due to the complexity of finding literature, we cannot claim our findings to be exhaustive. However, by following an iterative process of literature searching our findings are representative of this literature, allowing us to draw meaningful conclusions in the next section.

As a final observation, the reporting of implementation and collaboration varied greatly within each group of analytical method.

6. Conclusions and directions for future work

Community healthcare consists of a diverse range of geographically disparate services, each providing treatment to patients with specific health needs. As a result, the factors that are considered to influence patient flow are often markedly different to acute services and vary from one service to another. Considering the characteristics discussed in this review, it is common for a mixture of complex dynamics to be modelled within community care applications. Modelling these services can thus become complicated, requiring innovative methods to include all or some of these dynamics. This is highlighted by the range of different methods presented in this review.

Future directions for patient flow modelling within community care are now explored motivated by known challenges for community care, gaps found within the literature and any transferable knowledge between the two sets of literature.

Few models considered patient flow within systems of differing community services with most studies focussing on single services. Likewise, few also considered the mix of patients within these services. Consider, however, a diabetes pathway where patients may require treatment for comorbidities from multiple services based in the community. Each of these services will also provide care to a range of patients, not just those with diabetes. This example highlights a significant challenge in the management of community services. Namely, how to co-ordinate and deliver care within physically distributed, co-dependent services considering increasing episodic use by patients with differing needs. With a shift of focus towards care for the increasing number of patients with multiple long-term illnesses (ENGLand NHS, 2014 ), the patient mix within each service further exacerbates this challenge. Therefore, it would be beneficial to develop methods for modelling patient fl through multiple services to investigate these scenarios.

Considering the above, another useful direction would be to develop time-dependent analytical methods and simulation models for these scenarios. Whilst often analytically difficult, there are important benefits in using these methods as shown by the wide range of applications within this review. Given the characteristics of community services previously discussed, a helpful addition to the research landscape would be models of systems for which steady-state assumptions do not hold or where capacity, demand and timing of patient use vary. This would be helpful in community care where – due to the decentralisation – it can be hard to measure and interpret the impact that changes to one part of the system have on the whole system over short-term and long-term time periods. In considering flow in a system of inter-related services, or situations where patients may re-use the same service over a time period, the development of system level, timedependent methods would be beneficial in analysing the time variable impact of changes in the immediate, short term and long term for the whole system.

Finally, 13 papers used variable health/outcomes, of which 5 applied to multiple care interactions. Again considering the purpose and nature of community care, we suggest that methods which use multiple health states to model the improvement and decline of patient health throughout a course of care would be a useful direction for future study. A good example of these methods is presented by Deo et al. ( 2013 , 2015 ). Having otherwise not been widely explored, methods that quantify and evaluate the quality of care and include an interaction between patient outcomes, care pathways and flow within the system would be valuable and appropriate for community care modelling.

In considering OR methods for community services which combine patient flow modelling and patient outcomes, there may be some transferable knowledge from transplant models. For situations where non-physical are modelled, transplant list models may provide a useful basis as they share some distinct similarities to community care services – such as reneging, time-varying demand, limited resources and in some cases re-entrant patients. Transplant models may be informative for both scheduled care and unscheduled care.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care North Thames at Barts Health NHS Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The first author was supported by the Health Foundation as part of the Improvement Science PhD programme. The Health Foundation is an independent charity committed to bringing about better health and healthcare for people in the UK.

- Alagoz O., Maillart L. M., Schaefer A. J., & Roberts M. S. (2004). The optimal timing of living-donor liver transplantation . Management Science , 50 ( 10 ), 1420–1430. 10.1287/mnsc.1040.0287 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bayer S., Petsoulas C., Cox B., Honeyman A., & Barlow J. (2010). Facilitating stroke care planning through simulation modelling . Health Informatics Journal , 16 ( 2 ), 129–143. 10.1177/1460458209361142 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bhattacharjee P., & Ray P. K. (2014). Patient flow modelling and performance analysis of healthcare delivery processes in hospitals: A review and reflections . Computers & Industrial Engineering , 78 , 299–312. 10.1016/j.cie.2014.04.016 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bretthauer K. M., & Côté M. J. (1998). A model for planning resource requirements in health care organizations . Decision Sciences , 29 ( 1 ), 243–270. 10.1111/deci.1998.29.issue-1 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cardoso T., Oliveira M. D., & Barbosa-PóVoa A. (2012). Modeling the demand for long-term care services under uncertain information . Health Care Management Science , 15 ( 4 ), 385–412. 10.1007/s10729-012-9204-0 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cayirli T., Veral E., & Rosen H. (2006). Designing appointment scheduling systems for ambulatory care services . Health Care Management Science , 9 ( 1 ), 47–58. 10.1007/s10729-006-6279-5 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chan C. W., Farias V. F., Bambos N., & Escobar G. J. (2012). Optimizing intensive care unit discharge decisions with patient readmissions . Operations Research , 60 ( 6 ), 1323–1341. 10.1287/opre.1120.1105 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chand S., Moskowitz H., Norris J. B., Shade S., & Willis D. R. (2009). Improving patient flow at an outpatient clinic: Study of sources of variability and improvement factors . Health Care Management Science , 12 ( 3 ), 325–340. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chao J., et al. (2014). The long-term effect of community-based health management on the elderly with type 2 diabetes by the Markov modeling . Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics , 59 ( 2 ), 353–359. 10.1016/j.archger.2014.05.006 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clague J. E., Reed P. G., Barlow J., Rada R., & CLARKE M., & Edwards R. H. T. (1997). Improving outpatient clinic efficiency using computer simulation . International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance , 10 ( 5 ), 197–201. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cochran J. K., & Roche K. T. (2009). A multi-class queuing network analysis methodology for improving hospital emergency department performance . Computers & Operations Research , 36 ( 5 ), 1497–1512. [ Google Scholar ]

- Côté M. J. (2000). Understanding patient flow . Decision Line , 31 ( 2 ), 8–10. [ Google Scholar ]

- Deo S., Iravani S., Jiang T., Smilowitz K., & Samuelson S. (2013). Improving health outcomes through better capacity allocation in a community-based chronic care model . Operations Research , 61 ( 6 ), 1277–1294. 10.1287/opre.2013.1214 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Deo S., Rajaram K., Rath S., Karmarkar U. S., & Goetz M. B. (2015). Planning for HIV screening, testing, and care at the Veterans Health Administration . Operations Research , 63 ( 2 ), 287–304. 10.1287/opre.2015.1353 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Derienzo C. M., Shaw R. J., Meanor P., Lada E., Ferranti J., & Tanaka D. (2016). A discrete event simulation tool to support and predict hospital and clinic staffing . Health Informatics Journal 1460458216628314. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Diaz R., Behr J., Kumar S., & Britton B. (2015). Modeling chronic disease patient flows diverted from emergency departments to patient centered medical homes . IIE Transactions on Healthcare Systems Engineering , 5 ( 4 ), 268–285. 10.1080/19488300.2015.1095824 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Drekic S., Stanford D. A., Woolford D. G., & McAlister V. C. (2015). A model for deceased-donor transplant queue waiting times . Queueing Systems , 79 ( 1 ), 87–115. 10.1007/s11134-014-9417-7 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- ENGLand NHS (2014). Five year forward view . London: HM Government. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fialho A. S., Oliveira M. D., & Sa A. B. (2011). Using discrete event simulation to compare the performance of family health unit and primary health care centre organizational models in Portugal . BMC Health Services Research , 11 , 274–000. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garg L., McClean S., Barton M., Meenan B. J., & Fullerton B. J. (2012). Intelligent patient management and resource planning for complex, heterogeneous, and stochastic healthcare systems . IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics Part A: Systems and Humans , 42 ( 6 ), 1332–1345. 10.1109/TSMCA.2012.2210211 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goddard J., & Tavakoli M. (2008). Efficiency and welfare implications of managed public sector hospital waiting lists . European Journal of Operational Research , 184 ( 2 ), 778–792. 10.1016/j.ejor.2006.12.003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gough D., Thomas J., & Oliver S. (2012). Clarifying differences between review designs and methods . Systematic Reviews , 1 , 35. 10.1186/2046-4053-1-28 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gupta D., et al. (2007). Capacity planning for cardiac catheterization: A case study . Health Policy , 82 ( 1 ), 1–11. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.07.010 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hare W. L., Alimadad A., Dodd H., Ferguson R., & Rutherford A. (2009). A deterministic model of home and community care client counts in British Columbia . Health Care Management Science , 12 ( 1 ), 80–98. 10.1007/s10729-008-9082-7 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hensher M. (1997). Improving general practitioner access to physiotherapy: A review of the economic evidence . Health Services Management Research , 10 ( 4 ), 225–230. 10.1177/095148489701000403 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hulshof P. J. H., Kortbeek N., Boucherie R. J., Hans E. W., & Bakker P. J. M. (2012). Taxonomic classification of planning decisions in health care: A structured review of the state of the art in OR/MS . Health Systems , 1 , 129–175. 10.1057/hs.2012.18 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Izady N. (2015). Appointment capacity planning in specialty clinics: A queueing approach . Operations Research , 63 ( 4 ), 916–930. 10.1287/opre.2015.1391 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim S., & Kim S. (2015). Differentiated waiting time management according to patient class in an emergency care center using an open Jackson network integrated with pooling and prioritizing . Annals of Operations Research , 230 ( 1 ), 35–55. 10.1007/s10479-013-1477-2 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Koizumi N., Kuno E., & Smith T. E. (2005). Modeling patient flows using a queuing network with blocking . Health Care Management Science , 8 ( 1 ), 49–60. 10.1007/s10729-005-5216-3 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kucukyazici B., Verter V., & Mayo N. E. (2011). An analytical framework for designing community-based care for chronic diseases . Production and Operations Management , 20 ( 3 ), 474–488. 10.1111/poms.2011.20.issue-3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li S., Geng N., & Xie X. (2015). Radiation queue: meeting patient waiting time targets . IEEE Robotics and Automation Magazine , 22 ( 2 ), 51–63. [ Google Scholar ]

- Liquet B., Timsit J. F., & Rondeau V. (2012). Investigating hospital hetero-geneity with a multi-state frailty model: Application to nosocomial pneumonia disease in intensive care units . BMC Medical Research Methodology , 12 ( 1 ), 1. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Matta M. E., & Patterson S. S. (2007). Evaluating multiple performance measures across several dimensions at a multi-facility outpatient center . Health Care Management Science , 10 ( 2 ), 173–194. 10.1007/s10729-007-9010-2 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McLean D. R., & Jardine A. G. (2005). A simulation model to investigate the impact of cardiovascular risk in renal transplantation . Transplantation Proceedings , 37 ( 5 ), 2135–2143. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.03.057 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., & Altman D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement . Annals of Internal Medicine , 151 ( 4 ), 264–269. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Munton T., Martin A., Marrero I., Llewellyn A., Gibson K., & Gomersall A. (2011). Evidence: Getting out of hospital? The Health Foundation . [ Google Scholar ]

- Pagel C., Richards D. A., & Utley M. (2012). A mathematical modelling approach for systems where the servers are almost always busy . Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine . [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pan C., Zhang D., Kon A. W. M., Wai S. L., & Ang W. B. (2015). Patient flow improvement for an ophthalmic specialist outpatient clinic with aid of discrete event simulation and design of experiment . Health Care Management Science , 18 ( 2 ), 137–155. 10.1007/s10729-014-9291-1 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Panayiotopoulos J. C., & Vassilacopoulos G. (1984). Simulating hospital emergency departments queuing systems: (GI/G/m(t)) : (IHFF/N/∞) . European Journal of Operational Research , 18 ( 2 ), 250–258. 10.1016/0377-2217(84)90191-7 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Patrick J., Nelson K., & Lane D. (2015). A simulation model for capacity planning in community care . Journal of Simulation , 9 ( 2 ), 111–120. 10.1057/jos.2014.23 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ponis S. T., Delis A., Gayialis S. P., Kasimatis P., & Tan J. (2013). Applying discrete event simulation (DES) in healthcare . International Journal of Healthcare Information Systems and Informatics , 8 ( 3 ), 58–79. 10.4018/IJHISI [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Powell J. (2002). Systematic review of outreach clinics in primary care in the UK . Journal of Health Services Research and Policy , 7 ( 3 ), 177–183. 10.1258/135581902760082490 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Qiu Y., Song J., & Liu Z. (2016). A simulation optimisation on the hierarchical health care delivery system patient flow based on multi-fidelity models . International Journal of Production Research , 54 ( 21 ), 6478–6493. 10.1080/00207543.2016.1197437 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Santibáñez P., Chow V. S., French J., Puterman M. L., & Tyldesley S (2009). Reducing patient wait times and improving resource utilization at British Columbia Cancer Agency’s ambulatory care unit through simulation . Health Care Management Science , 12 ( 4 ), 392–407. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shechter S. M., et al. (2005). A clinically based discrete-event simulation of end-stage liver disease and the organ allocation process . Medical Decision Making , 25 ( 2 ), 199–209. 10.1177/0272989X04268956 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shi J., Peng Y., & Erdem E. (2014). Simulation analysis on patient visit efficiency of a typical VA primary care clinic with complex characteristics . Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory , 47 , 165–181. 10.1016/j.simpat.2014.06.003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shmueli A., Sprung C. L., & Kaplan E. H. (2003). Optimizing admissions to an intensive care unit . Health Care Management Science , 6 ( 3 ), 131–136. 10.1023/A:1024457800682 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sibbald B., McDonald R., & Roland M. (2007). Shifting care from hospitals to the community: A review of the evidence on quality and efficiency . Journal of Health Services Research and Policy , 12 ( 2 ), 110–117. 10.1258/135581907780279611 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Song J., Chen W., & Wang L. (2012). A block queueing network model for control patients flow congestion in urban healthcare system . International Journal of Services Operations and Informatics , 7 ( 2/3 ), 82–95. 10.1504/IJSOI.2012.051394 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stanford D. A., Lee J. M., Chandok N., & McAlister V. (2014). A queuing model to address waiting time inconsistency in solid-organ transplantation . Operations Research for Health Care , 3 ( 1 ), 40–45. 10.1016/j.orhc.2014.01.001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sterman J. D. (2000). Business dynamics: Systems thinking and modeling for a complex world . Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. [ Google Scholar ]

- Swisher J. R., & Jacobson S. H. (2002). Evaluating the design of a family practice healthcare clinic using discrete-event simulation . Health Care Management Science , 5 ( 2 ), 75–88. 10.1023/A:1014464529565 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Taylor K., Dangerfield B., & Le Grand J. (2005). Simulation analysis of the consequences of shifting the balance of health care: A system dynamics approach . Journal of Health Services Research & Policy , 10 ( 4 ), 196–202. 10.1258/135581905774414169 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thomsen M. S., & Nørrevang O. (2009). A model for managing patient booking in a radiotherapy department with differentiated waiting times . Acta Oncologica , 48 ( 2 ), 251–258. 10.1080/02841860802266680 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Utley M., Gallivan S., Pagel C., & Richards D. (2009). Analytical methods for calculating the distribution of the occupancy of each state within a multi-state flow system . IMA Journal of Management Mathematics , 20 ( 4 ), 345–355. 10.1093/imaman/dpn031 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- van Zon A. H., & Kommer G. J. (1999). Patient flows and optimal health-care resource allocation at the macro-level: A dynamic linear programming approach . Health Care Management Science , 2 ( 2 ), 87–96. 10.1023/A:1019083627580 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang Q. (2004). Modeling and analysis of high risk patient queues . European Journal of Operational Research , 155 ( 2 ), 502–515. 10.1016/S0377-2217(02)00916-5 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Whitten P. S., Mair F. S., Haycox A., May C. R., Williams T. L., & Hellmich S. (2002). Systematic review of cost effectiveness studies of telemedicine interventions . BMJ , 324 , 1434–1437. 10.1136/bmj.324.7351.1434 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wolstenholme E. (1999). A patient flow perspective of U.K. health services: Exploring the case for new “intermediate care” initiatives . System Dynamics Review , 15 ( 3 ), 253–271. 10.1002/(ISSN)1099-1727 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Xie H., Chaussalet T. J., & Millard P. H. (2005). A continuous time Markov model for the length of stay of elderly people in institutional long-term care . Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) , 168 ( 1 ), 51–61. 10.1111/rssa.2005.168.issue-1 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Xie H., Chaussalet T. J., & Millard P. H. (2006). A model-based approach to the analysis of patterns of length of stay in institutional long-term care . IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine , 10 ( 3 ), 512–518. 10.1109/TITB.2005.863820 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yuan Y., Gafni A., Russell J. D., & Ludwin D. (1994). Development of a central matching system for the allocation of cadaveric kidneys . Medical Decision Making , 14 ( 2 ), 124–136. 10.1177/0272989X9401400205 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zenios S. A. (1999). Modeling the transplant waiting list: A queueing model with reneging . Queueing Systems , 31 ( 3/4 ), 239–251. 10.1023/A:1019162331525 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zenios S. A., & Wein L. M. (2000). Dynamic allocation of kidneys to candidates on the transplant waiting list . Operations Research , 48 ( 4 ), 549–569. 10.1287/opre.48.4.549.12418 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang Y., Berman O., & Verter V. (2009). Incorporating congestion in preventive healthcare facility network design . European Journal of Operational Research , 198 ( 3 ), 922–935. 10.1016/j.ejor.2008.10.037 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang Y., & Puterman M. L. (2013). Developing an adaptive policy for long-term care capacity planning . Health Care Management Science , 16 ( 3 ), 271–279. 10.1007/s10729-013-9229-z [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang Y., Puterman M. L., Nelson N., & Atkins D. (2012). A simulation optimization approach to long-term care capacity planning . Operations Research , 60 ( 2 ), 249–261. 10.1287/opre.1110.1026 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Operations research in intensive care unit management: a literature review

Affiliations.

- 1 Universitäres Zentrum für Gesundheitswissenschaften am Klinikum Augsburg (UNIKA-T), Universitätsstraße 16, 86159, Augsburg, Germany.

- 2 School of Business and Economics, University of Augsburg, Universitätsstraße 16, 86159, Augsburg, Germany.

- 3 Faculty of Management, Economics and Social Science, University of Cologne, Albertus-Magnus-Platz, 50923, Köln, Germany. [email protected].

- PMID: 27518713

- DOI: 10.1007/s10729-016-9375-1

The intensive care unit (ICU) is a crucial and expensive resource largely affected by uncertainty and variability. Insufficient ICU capacity causes many negative effects not only in the ICU itself, but also in other connected departments along the patient care path. Operations research/management science (OR/MS) plays an important role in identifying ways to manage ICU capacities efficiently and in ensuring desired levels of service quality. As a consequence, numerous papers on the topic exist. The goal of this paper is to provide the first structured literature review on how OR/MS may support ICU management. We start our review by illustrating the important role the ICU plays in the hospital patient flow. Then we focus on the ICU management problem (single department management problem) and classify the literature from multiple angles, including decision horizons, problem settings, and modeling and solution techniques. Based on the classification logic, research gaps and opportunities are highlighted, e.g., combining bed capacity planning and personnel scheduling, modeling uncertainty with non-homogenous distribution functions, and exploring more efficient solution approaches.

Keywords: Capacity management; Health care; Intensive care unit; Management science; Operations research.

Publication types

- Hospital Administration

- Intensive Care Units / organization & administration*

- Operations Research*

- Quality of Health Care

Operations strategy: A literature review

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

Competitive pressures on American business have created the need for improved understanding and practice of operations strategy. Over the past 20 years some 80 articles and several books have been written on the subject. These writings, while diverse in nature and placement, serve to shape what we know about operations strategy and the opportunities for improved practice and meaningful research. This paper examines an underlying argument that exists within the literature that proper strategic positioning or aligning of operations capabilities can significantly impact competitive strength and business performance of an organization. The discussion is organized around four related premises: (1) that there exists a strategic, as opposed to a tactical, view of operations, (2) that there must be some synergistic process of integrating business and operations strategic issues, (3) that there are operations decision or policy areas which demonstrate strategic opportunities, and (4) that conceptual structures exist by which to target and focus operations strategy. The paper concludes that the literature and emerging research support each of these premises to varying degrees. The authors believe that further understanding of these premises could be benefited by more careful and consistent definition of operations strategy concepts and terminology, by more attention being placed on the content and process of operations strategy, by more empirical study, and finally by more emphasis being placed on service operations strategy.

Publisher link

- 10.1016/0272-6963(89)90016-8

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to the citations in Scopus

Fingerprint

- Operation Strategy Keyphrases 100%

- Literature Reviews Social Sciences 100%

- Operations Strategy Social Sciences 100%

- Research Support Keyphrases 16%

- Policy Area Keyphrases 16%

- Strategic Opportunities Keyphrases 16%

- Strength Performance Keyphrases 16%

- Business Performance Keyphrases 16%

T1 - Operations strategy

T2 - A literature review

AU - Anderson, John C.

AU - Cleveland, Gary

AU - Schroeder, Roger G.

PY - 1989/4

Y1 - 1989/4

N2 - Competitive pressures on American business have created the need for improved understanding and practice of operations strategy. Over the past 20 years some 80 articles and several books have been written on the subject. These writings, while diverse in nature and placement, serve to shape what we know about operations strategy and the opportunities for improved practice and meaningful research. This paper examines an underlying argument that exists within the literature that proper strategic positioning or aligning of operations capabilities can significantly impact competitive strength and business performance of an organization. The discussion is organized around four related premises: (1) that there exists a strategic, as opposed to a tactical, view of operations, (2) that there must be some synergistic process of integrating business and operations strategic issues, (3) that there are operations decision or policy areas which demonstrate strategic opportunities, and (4) that conceptual structures exist by which to target and focus operations strategy. The paper concludes that the literature and emerging research support each of these premises to varying degrees. The authors believe that further understanding of these premises could be benefited by more careful and consistent definition of operations strategy concepts and terminology, by more attention being placed on the content and process of operations strategy, by more empirical study, and finally by more emphasis being placed on service operations strategy.

AB - Competitive pressures on American business have created the need for improved understanding and practice of operations strategy. Over the past 20 years some 80 articles and several books have been written on the subject. These writings, while diverse in nature and placement, serve to shape what we know about operations strategy and the opportunities for improved practice and meaningful research. This paper examines an underlying argument that exists within the literature that proper strategic positioning or aligning of operations capabilities can significantly impact competitive strength and business performance of an organization. The discussion is organized around four related premises: (1) that there exists a strategic, as opposed to a tactical, view of operations, (2) that there must be some synergistic process of integrating business and operations strategic issues, (3) that there are operations decision or policy areas which demonstrate strategic opportunities, and (4) that conceptual structures exist by which to target and focus operations strategy. The paper concludes that the literature and emerging research support each of these premises to varying degrees. The authors believe that further understanding of these premises could be benefited by more careful and consistent definition of operations strategy concepts and terminology, by more attention being placed on the content and process of operations strategy, by more empirical study, and finally by more emphasis being placed on service operations strategy.

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=0000186218&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=0000186218&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1016/0272-6963(89)90016-8

DO - 10.1016/0272-6963(89)90016-8

M3 - Article

AN - SCOPUS:0000186218

SN - 0272-6963

JO - Journal of Operations Management

JF - Journal of Operations Management

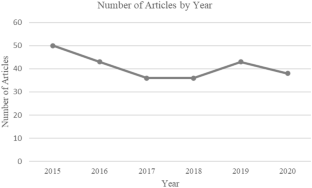

Current Trends in Operating Room Scheduling 2015 to 2020: a Literature Review

- Original Research

- Published: 03 March 2022

- Volume 3 , article number 21 , ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Sean Harris ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1567-1339 1 &

- David Claudio 2

914 Accesses

4 Citations

Explore all metrics

The operating room scheduling problem is a popular research topic due to its complexity and relevance. Previous literature reviews established a useful classification system for categorizing technical operating room scheduling articles through 2014. The increasing number of technical operating room scheduling articles published per year necessitates another literature review to allow researchers to react more quickly to emerging trends. This review builds upon previous classification schemes and categorizes 246 technical operating room scheduling articles from 2015 to 2020. Current trends and areas for future research are identified. Most notably, two major themes emerge. First, researchers continue to develop and innovate across each category. Second, the lack of real-life model implementation remains the greatest challenge facing the field.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The role of artificial intelligence in healthcare: a structured literature review

Silvana Secinaro, Davide Calandra, … Paolo Biancone

Interventions to improve team effectiveness within health care: a systematic review of the past decade

Martina Buljac-Samardzic, Kirti D. Doekhie & Jeroen D. H. van Wijngaarden

Exploring the gap between research and practice in human resource management (HRM): a scoping review and agenda for future research

Philip Negt & Axel Haunschild

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Cardoen B, Demeulemeester E, Beliën J (2010) Operating room planning and scheduling: a literature review. Eur J Oper Res 201(3):921–932

Article Google Scholar

Denton B, Viapiano J, Vogl A (2007) Optimization of surgery sequencing and scheduling decisions under uncertainty. Health Care Manag Sci 10(1):13–24

Macario A et al (1995) Where are the costs in perioperative care? Analysis of hospital costs and charges for inpatient surgical care. J Am Soc Anesthesiol 83(6):1138–1144

Demeulemeester E et al (2013) Operating room planning and scheduling. Handbook of healthcare operations management. Springer, pp 121–152

Chapter Google Scholar

Samudra M et al (2016) Scheduling operating rooms: achievements, challenges and pitfalls. J Sched 19(5):493–525

Guerriero F, Guido R (2011) Operational research in the management of the operating theatre: a survey. Health Care Manag Sci 14(1):89–114

Erdogan SA, Denton BT (2010) Surgery planning and scheduling . Wiley encyclopedia of operations research and management science

Zhu S et al (2019) Operating room planning and surgical case scheduling: a review of literature. J Comb Optim 37(3):757–805

Rahimi I, Gandomi AH (2020) A comprehensive review and analysis of operating room and surgery scheduling . Arch Comput Methods Eng

Abedini A, Li W, Ye H (2017) An optimization model for operating room scheduling to reduce blocking across the perioperative process. Proc Manuf 10:60–70

Google Scholar

Al-Refaie A, Judeh M, Chen T (2018) Optimal multiple-period scheduling and sequencing of operating room and intensive care unit. Oper Res Int J 18(3):645–670

Aringhieri R et al (2015) A two level metaheuristic for the operating room scheduling and assignment problem. Comput Oper Res 54:21–34

Aringhieri R, Landa P, Tànfani E (2015) Assigning surgery cases to operating rooms: a VNS approach for leveling ward beds occupancies. Electron Notes Discrete Math 47:173–180

Ballestín F, Pérez Á, Quintanilla S (2019) Scheduling and rescheduling elective patients in operating rooms to minimise the percentage of tardy patients. J Sched 22(1):107–118

Bam M et al (2017) Surgery scheduling with recovery resources. IISE Trans 49(10):942–955

Behmanesh R, Zandieh M (2019) Surgical case scheduling problem with fuzzy surgery time: an advanced bi-objective ant system approach . Know Based Syst 186:104913

Behmanesh R, Zandieh M, Hadji Molana SM (2019) The surgical case scheduling problem with fuzzy duration time: An ant system algorithm . Scientia Iranica 26(3):1824–1841

Ben-Arieh D (2015) Optimizing surgery schedule with PICU nursing constraints. In: Shih YC, Liang SFM (eds) Bridging Research and Good Practices Towards Patient Welfare: Healthcare Systems Ergonomics and Patient Safety 2014. Taylor and Francis Group, London, pp 251–258

Benchoff B, Yano CA, Newman A (2017) Kaiser permanente Oakland medical center optimizes operating room block schedule for new hospital. Interfaces 47(3):214–229

Calegari R et al (2020) Surgery scheduling heuristic considering OR downstream and upstream facilities and resources. BMC Health Serv Res 20:1–11

Chiang AJ et al (2019) Multi-objective optimization for simultaneous operating room and nursing unit scheduling. Int J Eng Bus Manag 11:1847979019891022

Farzad G, Mohammad SM (2016) A stochastic surgery sequencing model considering the moral and human virtues. Mod Appl Sci 10(9):68

Fügener A (2015) An integrated strategic and tactical master surgery scheduling approach with stochastic resource demand. J Bus Logist 36(4):374–387

Fügener A et al (2016) Improving intensive care unit and ward utilization by adapting master surgery schedules. A&A Case Rep 6(6):172–180

Hamid M et al (2019) Operating room scheduling by considering the decision-making styles of surgical team members: a comprehensive approach. Comput Oper Res 108:166–181

Hooshmand F, MirHassani S, Akhavein A (2017) A scenario-based approach for master surgery scheduling under uncertainty. Int J Healthc Technol Manag 16(3–4):177–203

Jebali A, Diabat A (2015) A stochastic model for operating room planning under capacity constraints. Int J Prod Res 53(24):1–19

Li X et al (2015) Scheduling elective surgeries: the tradeoff among bed capacity, waiting patients and operating room utilization using goal programming . Health Care Manag Sci 1–22

Liu N et al (2019) Integrated scheduling and capacity planning with considerations for patients’ length-of-stays. Prod Oper Manag 28(7):1735–1756

Marques I, Captivo ME (2017) Different stakeholders’ perspectives for a surgical case assignment problem: Deterministic and robust approaches. Eur J Oper Res 261(1):260–278

Ozen A et al (2015) Optimization and simulation of orthopedic spine surgery cases at Mayo Clinic. Manuf Serv Oper Manag 18(1):157–175

Rath S, Rajaram K, Mahajan A (2017) Integrated anesthesiologist and room scheduling for surgeries: Methodology and application. Oper Res 65(6):1460–1478

Rowse E et al (2015) Applying set partitioning methods in the construction of operating theatre schedules . Proceedings of the European Conference on Data Mining 2015 and International Conferences on Intelligent Systems and Agents 2015 and Theory and Practice in Modern Computing 2015:133–140

Riise A, Mannino C, Burke EK (2016) Modelling and solving generalised operational surgery scheduling problems. Comput Oper Res 66:1–11

Santoso LW et al (2017) Operating room scheduling using hybrid clustering priority rule and genetic algorithm. In: AIP Conference Proceedings. AIP Publishing

Saremi A et al (2015) Bi-criteria appointment scheduling of patients with heterogeneous service sequences. Expert Syst Appl 42(8):4029–4041

Schiele J, Koperna T, Brunner JO (2020) Predicting intensive care unit bed occupancy for integrated operating room scheduling via neural networks . Naval Res Logist (NRL)

Van Huele C, Vanhoucke M (2015) Operating theatre modelling: integrating social measures. J Simul 9(2):121–128

Vancroonenburg W, De Causmaecker P, Berghe GV (2019) Chance-constrained admission scheduling of elective surgical patients in a dynamic, uncertain setting . Oper Res Health Care 22:100196

Villarreal MC, Keskinocak P (2016) Staff planning for operating rooms with different surgical services lines. Health Care Manag Sci 19(2):144–169

Visintin F, Cappanera P, Banditori C (2016) Evaluating the impact of flexible practices on the master surgical scheduling process: an empirical analysis. Flex Serv Manuf J 28(1–2):182–205

Wang D et al (2015) Prioritized surgery scheduling in face of surgeon tiredness and fixed off-duty period. J Comb Optim 30(4):967–981

Wang S, Su H, Wan G (2015) Resource-constrained machine scheduling with machine eligibility restriction and its applications to surgical operations scheduling. J Comb Optim 30(4):982–995

Yahia Z, Eltawil AB, Harraz NA (2016) The operating room case-mix problem under uncertainty and nurses capacity constraints. Health Care Manag Sci 19(4):383–394

Zenteno AC et al (2016) Systematic OR block allocation at a large academic medical center: Comprehensive review on a data-driven surgical scheduling strategy. Ann Surg 264(6):973–981

Zhang J, Dridi M, El Moudni A (2019) A two-level optimization model for elective surgery scheduling with downstream capacity constraints. Eur J Oper Res 276(2):602–613

Berg BP, Denton BT (2017) Fast approximation methods for online scheduling of outpatient procedure centers. INFORMS J Comput 29(4):631–644

Burns P, Konda S, Alvarado M (2020) Discrete-event simulation and scheduling for Mohs micrographic surgery . J Simul 1–15

Gul S, Denton BT, Fowler JW (2015) A progressive hedging approach for surgery planning under uncertainty. INFORMS J Comput 27(4):755–772

Nemati S et al (2016) The surgical patient routing problem: a central planner approach. INFORMS J Comput 28(4):657–673

Wu Q, Xie N, Shao Y (2020) Day surgery appointment scheduling with patient preferences and stochastic operation duration . Technol Health Care 1–12. Preprint

Abdeljaouad MA et al (2020) A simulated annealing for a daily operating room scheduling problem under constraints of uncertainty and setup . INFOR: Info Syst Oper Res 1–22

Abedini A, Ye H, Li W (2016) Operating room planning under surgery type and priority constraints. Proc Manuf 5:15–25

Addis B et al (2016) Operating room scheduling and rescheduling: a rolling horizon approach. Flex Serv Manuf J 28(1–2):206–232

Agrawal V et al (2019) Minimax c th percentile of makespan in surgical scheduling . Health Syst 1–13

Ahmed A, Ali H (2020) Modeling patient preference in an operating room scheduling problem . Oper Res Health Care 100257

Aissaoui NO, Khlif HH, Zeghal FM (2020) Integrated proactive surgery scheduling in private healthcare facilities . Comput Ind Eng 148:106686

Akbarzadeh B et al (2019) The re-planning and scheduling of surgical cases in the operating room department after block release time with resource rescheduling. Eur J Oper Res 278(2):596–614

Akbarzadeh B et al (2020) A diving heuristic for planning and scheduling surgical cases in the operating room department with nurse re-rostering . J Sched 1–24

Al-Refaie A, Judeh M, Li M-H (2018) Optimal fuzzy scheduling and sequencing of multiple-period operating room. AI EDAM 32(1):108–121

Al Hasan H et al (2018) Surgical case scheduling with sterilising activity constraints . Int J Prod Res 1–19

Ali HH, Lamsali H, Othman SN (2019) Operating rooms scheduling for elective surgeries in a hospital affected by war-related incidents. J Med Syst 43(5):139

Ansarifar J et al (2018) Multi-objective integrated planning and scheduling model for operating rooms under uncertainty. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part H: J Eng Med 232(9):930–948

Assad DBN, Spiegel T (2019) Maximizing the efficiency of residents operating room scheduling: a case study at a teaching hospital . Production 29

Astaraky D, Patrick J (2015) A simulation based approximate dynamic programming approach to multi-class, multi-resource surgical scheduling. Eur J Oper Res 245(1):309–319

Atighehchian A, Sepehri MM, Shadpour P (2015) Operating room scheduling in teaching hospitals: a novel stochastic optimization model. Int J Hosp Res 4(4):171–176

Atighehchian A et al (2019) A two-step stochastic approach for operating rooms scheduling in multi-resource environment . Ann Oper Res 1–24

Baesler F, Gatica J, Correa R (2015) Simulation optimisation for operating room scheduling. Int J Simul Model (IJSIMM) 14(2):215–226

Bai M, Storer RH, Tonkay GL (2017) A sample gradient-based algorithm for a multiple-OR and PACU surgery scheduling problem . IISE Trans 1–14

Bandi C, Gupta D (2020) Operating room staffing and scheduling. Manuf Serv Oper Manag 22(5):958–974

Barbagallo S et al (2015) Optimization and planning of operating theatre activities: an original definition of pathways and process modeling. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 15(1):38

Barrera J et al (2020) Operating room scheduling under waiting time constraints: the Chilean GES plan. Ann Oper Res 286(1):501–527

Barz C, Rajaram K (2015) Elective patient admission and scheduling under multiple resource constraints. Prod Oper Manag 24(12):1907–1930

Behmanesh R, Zandieh M, Hadji Molana SM (2020) Multiple resource surgical case scheduling problem: ant colony system approach . Econ Comput Econ Cyber Stud Res 54(1)

Belkhamsa M, Jarboui B, Masmoudi M (2018) Two metaheuristics for solving no-wait operating room surgery scheduling problem under various resource constraints. Comput Ind Eng 126:494–506