Estimating the Health & Economic Cost of Air Pollution in the Philippines

In the Philippines, air pollution is the third highest risk factor driving death and disability due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs), and is also the leading environmental risk to health (IHME 2020). Its costs are not limited to the individual or community level, but also nationally, as air pollution-related health impacts yield corresponding financial and economic costs, which are often unaccounted for in policymaking.

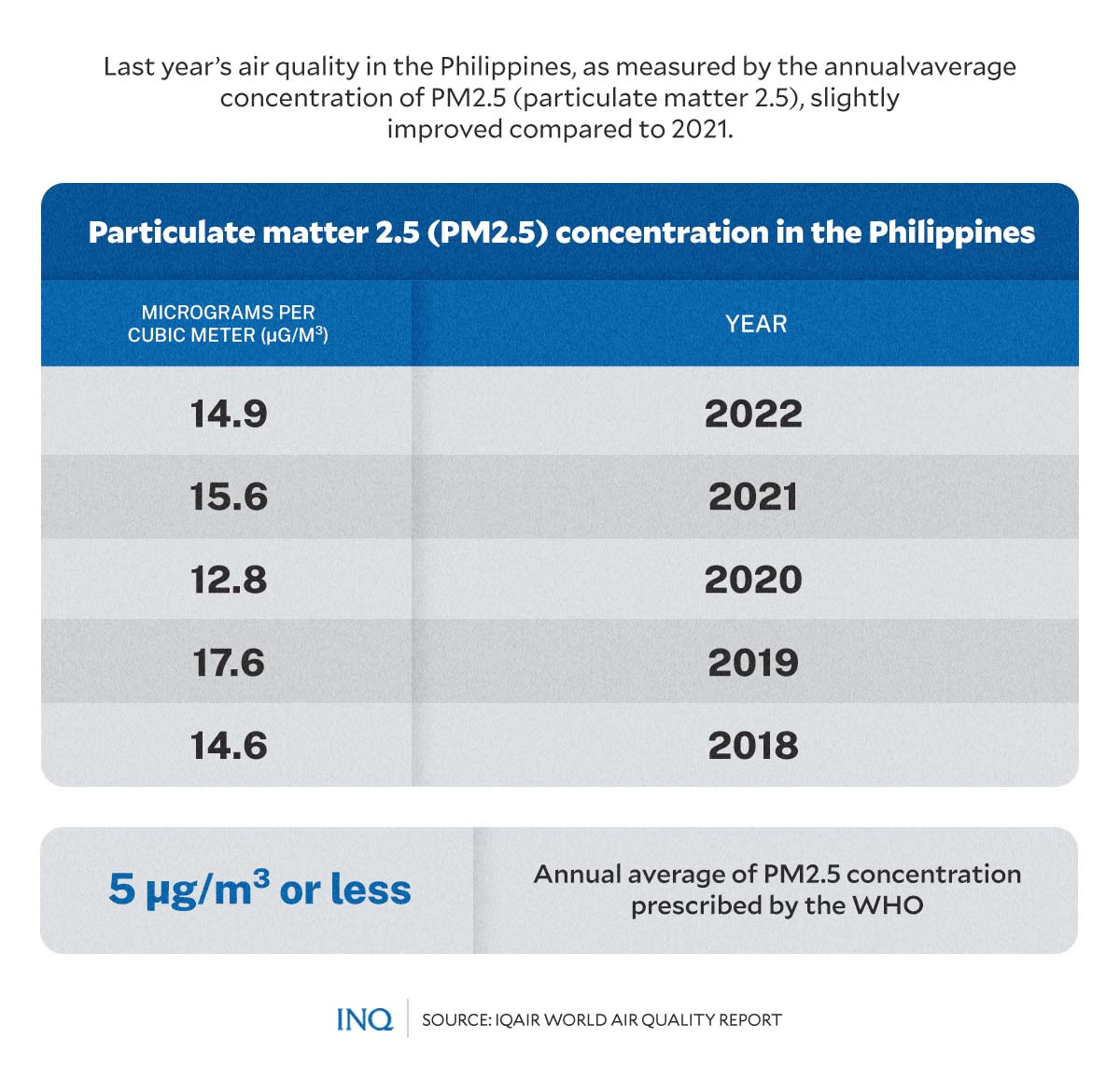

To add urgency to the issue, a growing body of scientific studies and literature are finding that air pollution is more dangerous to human health than previously thought. The World Health Organization updated its National Ambient Air Quality Guidelines (AQG) in September 2021, tightening the guidelines of annual average air pollution exposure to 5µg/m 3 from 10µg/m 3 for PM 2.5 and to 10µg/m 3 from 40µg/m 3 for nitrogen dioxide (NO 2 ).

Quantifying the impacts of air pollution on human health and the economy is important, especially in countries like the Philippines, where air pollution levels are increasing due to a growing number of fossil fuel pollution sources across various sectors.

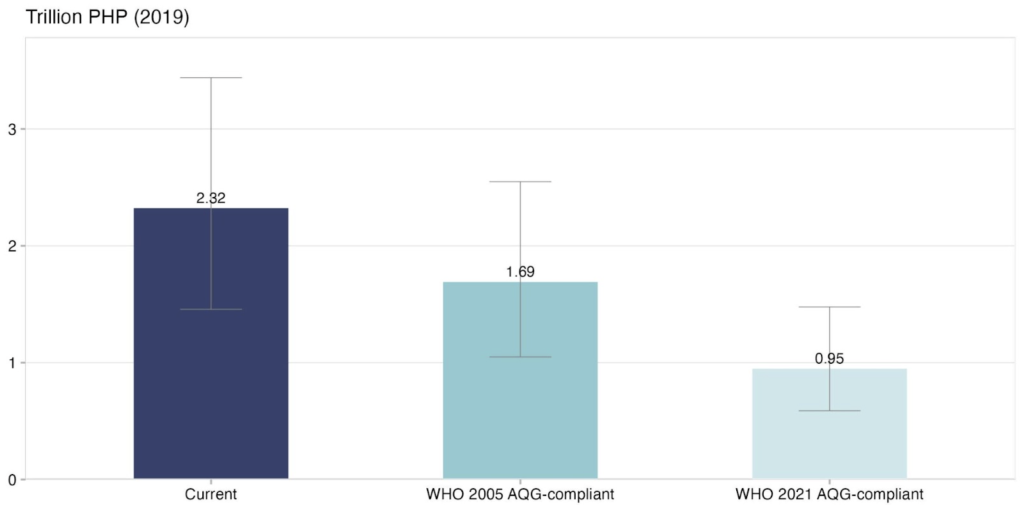

Our research found that air pollution was responsible for 66,230 deaths in the Philippines in 2019, of which 64,920 deaths were estimated to be adults and 1,310 children. This is significantly higher than previous estimates made for the country, aligning the impact with the most recent literature. The corresponding economic cost of exposure to air pollution is estimated at PHP 2.32 trillion (US$ 44.8 billion) in 2019 , or a GDP equivalent of 11.9% of the country’s GDP in 2019. Premature deaths account for most of the estimated economic cost at PHP 2.2 trillion (US$ 42.8 billion).

This report covers the methodology and results of estimating the health and economic cost of air pollution in the Philippines under three scenarios: a baseline scenario, a WHO 2005 AQG-compliant scenario, and a WHO 2021 AQG-compliant scenario.

6 February 2023

Lauri Myllyvirta, Hubert Thieriot, Isabella Suarez

Philippines

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Tackling air pollution in the Philippines

Affiliations.

- 1 College of Medicine, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines.

- 2 Planetary and Global Health Program, St Luke's Medical Center College of Medicine-William H Quasha Memorial, Quezon City 1112, Philippines; Sunway Centre for Planetary Health, Sunway University, Selangor, Malaysia. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 35397217

- DOI: 10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00065-1

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

RRG is a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of The Lancet Planetary Health. OAGT declares no competing interests.

- Global urban temporal trends in fine particulate matter (PM 2·5 ) and attributable health burdens: estimates from global datasets. Southerland VA, Brauer M, Mohegh A, Hammer MS, van Donkelaar A, Martin RV, Apte JS, Anenberg SC. Southerland VA, et al. Lancet Planet Health. 2022 Feb;6(2):e139-e146. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00350-8. Epub 2022 Jan 5. Lancet Planet Health. 2022. PMID: 34998505 Free PMC article.

Similar articles

- We need tougher action on reducing air pollution. Patel L. Patel L. BMJ. 2022 Dec 30;379:o3072. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o3072. BMJ. 2022. PMID: 36585022 No abstract available.

- The poison we breathe. Tandon A, Kanchan T, Tandon A. Tandon A, et al. Lancet. 2020 Feb 1;395(10221):e18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32547-4. Lancet. 2020. PMID: 32007175 No abstract available.

- Air pollution: a global problem needs local fixes. Li X, Jin L, Kan H. Li X, et al. Nature. 2019 Jun;570(7762):437-439. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-01960-7. Nature. 2019. PMID: 31239571 No abstract available.

- [Surveillance of environmental risks in public health. The case of air pollution]. Ballester F. Ballester F. Gac Sanit. 2005 May-Jun;19(3):253-7. doi: 10.1157/13075960. Gac Sanit. 2005. PMID: 15960960 Review. Spanish. No abstract available.

- Public health risks from motor vehicle emissions. Utell MJ, Warren J, Sawyer RF. Utell MJ, et al. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994;15:157-78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.15.050194.001105. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994. PMID: 8054079 Review. No abstract available.

- Examining the endpoint impacts, challenges, and opportunities of fly ash utilization for sustainable concrete construction. Orozco C, Tangtermsirikul S, Sugiyama T, Babel S. Orozco C, et al. Sci Rep. 2023 Oct 25;13(1):18254. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-45632-z. Sci Rep. 2023. PMID: 37880405 Free PMC article.

- Pediatric asthma in the Philippines: risk factors, barriers, and steps forward across the child's life stages. Legaspi KEY, Dychiao RGK, Dee EC, Kho-Dychiao RM, Ho FDV. Legaspi KEY, et al. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023 Jun 7;35:100806. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100806. eCollection 2023 Jun. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023. PMID: 37424689 Free PMC article. No abstract available.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Value of clean water resources: estimating the water quality improvement in metro manila, philippines.

1. Introduction

1.1. water quality issues, 1.2. study area and the issue, 1.3. objective, 2. materials and methods, 2.1. contingent valuation method, 2.2. survey design, 2.3. survey administration technique and data collection, 3.1. overview, 3.2. data validation, 3.3. wtp and economic value of water quality improvement, 4. discussion and policy implications, 5. conclusions and future plans, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest, scenario presented in the survey on water quality improvement in metro manila, philippines.

- Building new wastewater treatment plant

- Expansion of existing city’s sewerage system

- WEPA (Water Environment Partnership in Asia). 2017. Available online: http://wepa-db.net/3rd/en/index.html (accessed on 14 June 2017).

- World Bank. Philippines Environmental Monitor. 2003. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/144581468776089600/pdf/282970PH0Environment0monitor.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2017).

- Palanca-Tan, R. Knowledge, attitudes, and willingness to pay for domestic sewerage and sanitation services: A contingent valuation survey in Metro Manila. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Southeast Asian Water Environment, Hanoi, Vietnam, 8–10 November 2012; Volume 10. Part I. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rappler News. Metro Creeks: Less Trash, but Water Quality Not Improving. Available online: http://www.rappler.com/science-nature/environment/70065-metro-manila-creeks-rivers-water-pollution (accessed on 23 February 2016).

- World Bank. Economic Impacts of Sanitation in Southeast Asia: A Four-Country Study Conducted in Cambodia, Indonesai, the Philippines and Vietnam under the Economics of Sanitation Initiative (ESI) ; Research Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; p. 149. [ Google Scholar ]

- UNU-IAS. Low Carbon Urban Water Environment Project—Case Study in the Philippines ; Draft Final Report; UNU: Shibuya, Tokyo, 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Venkatachalam, L. The contingent valuation method: A review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004 , 24 , 89–124. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hanemann, W.M. Valuing the environment through contingent valuation. J. Econ. Perspect. 1994 , 8 , 19–43. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Loomis, J.B. Expanding contingent value sample estimates to aggregate benefit estimates: Current practices and proposed solutions. Land Econ. 1987 , 63 , 396–402. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bateman, I.J.; Carson, R.T.; Day, B.; Hanemann, M.W.; Hanley, N.; Hett, T. Economic Valuation with Stated Preference Techniques: A Manual ; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mitchell, R.C.; Carson, R.T. Using Surveys to Value Public Goods: The Contingent Valuation Method ; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; p. 453. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nelson, M.N.; Loomis, J.B.; Jakus, P.M.; Kealy, M.J.; von Stackelburg, N.; Ostermiller, J. Linking ecological data and economics to estimate the total economic value of improving water quality by reducing nutrients. Ecol. Econ. 2015 , 118 , 1–9. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Van Houtven, G.; Mansfield, C.; Phaneuf, D.J.; von Haefen, R.; Milstead, B.; Kenney, M.A.; Reckhow, K.H. Combining expert elicitation and stated preference methods to value ecosystem services from improved lake water quality. Ecol. Econ. 2014 , 99 , 40–52. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Atkins, J.P.; Burdon, D. An initial economic evaluation of water quality improvements in the Randers Fjord, Denmark. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2006 , 53 , 195–204. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Kramer, R.A.; Eisen-Hecht, J.I. Estimating the economic value of water quality protection in the Catawba River basin. Water Resour. Res. 2002 , 38 , 1–10. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Environmental Management Bureau. National Water Quality Status Report 2006–2013 ; Visayas Avenue, Quezon City; Department of Environment and Natural Resources—Environmental Management Bureau: Metro Manila, Philippines, 2014; p. 76.

- World Bank. Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing. Available online: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/EXTDEC/EXTRESEARCH/EXTPROGRAMS/EXTCOMPTOOLS/0,,contentMDK:23426734~pagePK:64168182~piPK:64168060~theSitePK:8213597,00.html (accessed on 15 May 2016).

- Maddala, G.S. Limited-Dependent and Qualitative Variables in Econometrics ; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1983; p. 401. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kennedy, P. A Guide to Econometrics , 3rd ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992; p. 409. [ Google Scholar ]

- PSA (Philippine Statistics Authority). Philippine Yearbook ; Demography; PSA: Quezon City, Philippines, 2011; p. 77. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/ (accessed on 5 June 2017).

- Jalilov, S.-M. Sustainable Urban Water Environments in Southeast Asia: Addressing the Pollution of Urban Waterbodies in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Viet Nam, United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability. 2016. Available online: http://collections.unu.edu/view/UNU:5796#viewAttachments (accessed on 12 November 2017).

- Water Supply and Sanitation in the Philippines: Turning Finance into Services for the Future ; Service Delivery Assessment, Water and Sanitation Program; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; p. 90.

Click here to enlarge figure

| Classification | Description |

|---|---|

| Class AA | Public Water Supply Class I. Intended primarily for waters having watersheds, which are uninhabited and otherwise protected, and which require only approved disinfection to meet the Philippine National Standards for Drinking Water (PNSDW) |

| Class A | Public Water Supply Class II. For sources of water supply that will require complete treatment (coagulation, sedimentation, filtration, and disinfection) to meet the PNSDW |

| Class B | Recreational Water Class I. For primary contact recreation such as bathing, swimming, skin diving, etc. (particularly those designated for tourism purposes) |

| Class C | (1) Fishery Water for the propagation and growth of fish and other aquatic resources (2) Recreational Water Class II (boating, etc.) (3) Industrial Water Supply Class I (for manufacturing processes after treatment) |

| Class D | (1) For agriculture, irrigation, livestock watering, etc. (2) Industrial Water Supply Class II (e.g., cooling, etc.) (3) Other inland waters, by their quality, belong to this classification |

| Description | Survey Statistics | Philippines’ Statistics * |

|---|---|---|

| 5.3 | 4.6 | |

| Females—46% | Females—49% | |

| Males—54% | Males—51% | |

| Median in interval 26–40 | Median—23.4 | |

| No school—1% | No school—2% | |

| Grade school 1–8—7% | Grade school 1–8—11.7% | |

| Grade school 9–11—29% | Grade school 9–11—19.1% | |

| Some school—29% | Some school—54.4% | |

| College graduate—32% | College graduate—10.1% | |

| Postgraduate—2% | Postgraduate—2.7% | |

| Extreme poverty—11% | Extreme poverty—5.7% | |

| Poverty level—14% | Poverty level—16.5% |

| Variable | N | Min | Max | Mean | StDev | Pr > |t| | Lower 95% CL for Mean | Upper 95% CL for Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTP_Swim | 170 | 0 | 1200 | 102.44 | 156.39 | <0.0001 | 78.76 | 126.12 |

| WTP_Fish | 170 | 0 | 1000 | 102.39 | 156.35 | <0.0001 | 78.72 | 126.07 |

| Variable | WTP Swimmable | WTP Fishable |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 14.58 * | 15.12 * |

| Marital status | 7.91 * | 8.03 * |

| Income | 23.68 ** | 23.91 ** |

| R | 0.18 | 0.19 |

Share and Cite

Jalilov, S.-M. Value of Clean Water Resources: Estimating the Water Quality Improvement in Metro Manila, Philippines. Resources 2018 , 7 , 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources7010001

Jalilov S-M. Value of Clean Water Resources: Estimating the Water Quality Improvement in Metro Manila, Philippines. Resources . 2018; 7(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources7010001

Jalilov, Shokhrukh-Mirzo. 2018. "Value of Clean Water Resources: Estimating the Water Quality Improvement in Metro Manila, Philippines" Resources 7, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources7010001

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

Environmental Challenges in the Philippines

- First Online: 21 April 2017

Cite this chapter

- Yves Boquet 2

Part of the book series: Springer Geography ((SPRINGERGEOGR))

2372 Accesses

5 Citations

6 Altmetric

The Republic of the Philippines is one of most exposed countries in the world to many “natural” hazards: earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunami, lahar flows, typhoons, flooding, landslides, and sea level rise. Earthquake risks make Metro Manila especially vulnerable, due to the high population density and the poor quality of buildings, partly linked to corruption. This chapter examines the current policies to reduce risk in the metropolis and the scales of vulnerability, both at the national, regional, community and individual levels, focusing on the resilience of people and society when confronted with danger. Their vulnerability is heightened with several forms of environmental degradation, such as deforestation, soil impoverishments, mining impacts, all favoring landslides and floods, as well as the loss in biodiversity, both in maritime and land areas. Despite the establishment of protected areas and natural parks, adaptation to climate change and mitigation of damage remains difficult and requires building up a better institutional resilience.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Each event recorded in this database is killed at least ten people, affected at least 100 people or needed international aid.

http://www.preventionweb.net/english/countries/statistics/?cid=135

Adaptations are actions that people do to adjust to stimuli, such as rainfall or flooding. Mitigation, in the context of climate change, is more about reducing greenhouse-gas emission (Mayuga 2015 ). Adaptations are more local in scale, mitigation more global in scope.

For example in 1645 (destruction of Manila’s cathedral), even as the epicenter was far the city, in Gabaldon, Nueva Ecija . The latest major tremor affecting Manila with casualties and destructions was the 1968 Casiguran earthquake, with an epicenter in Aurora province.

http://www.gov.ph/downloads/1977/02feb/19770219-PD-1096-FM.pdf

Twelve non-technical questions, accompanied by simple drawings, easy to answer by any resident: (1) Who built or designed my house? (2) How old is my house? (3) Has my house been damaged by past earthquakes or other disasters? (4) What is the shape of my house? (5) Has my house been extended or expanded? (6) Are the external walls of my house 6-inch (150 mm) thick? (7) Are steel bars of standard size and spacing used in walls? (8) Are there unsupported walls more than 3 m wide? (9) What is the gable wall of my house made of? (10) What is the foundation of my house? (11) What is the soil condition under my house? (12) What is the overall condition of my house?

http://www.ndrrmc.gov.ph/index.php/13-disaster-risk-reduction-and-management-laws/1457-the-valley-fault-system-atlas

http://www.nababaha.com/marikina_valley_fault.htm

http://tremors.instigators.io /

Such as the European Union, CARE Netherlands , GIZ (German Agency for International Cooperation), USAid or JICA.

“Adaptation” refers to policies helping protect citizens, the economy, and the environment from climate change impacts like storms, drought, flooding, landslides, and heat waves. Climate change “mitigation” refers to policies aiming at a reduction of carbon emissions from the transportation, garbage management, agriculture, energy, and industrial sectors.

The forum was originally composed of 20 developing countries (Afghanistan, Bangladesh , Barbados, Bhutan, Costa Rica , Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Kiribati, Madagascar , Maldives, Nepal , Philippines, Rwanda, St Lucia, Tanzania, Timor Leste, Tuvalu, Vanuatu , Vietnam ), The inaugural meeting of this “V-20” took place in Lima, Peru , in October 2015, in conjunction with the 2015 Annual Meetings of the World Bank Group and International Monetary Fund, with the Philippines serving as chair of the meeting. The call to create the V20 originated from the Climate Vulnerable Forum’s Costa Rica Action Plan (2013–2015) in a major effort to strengthen economic and financial responses to climate change. It foresaw a high-level policy dialogue pertaining to action on climate change and the promotion of climate resilient and low emission development with full competence for addressing economic and financial issues beyond the remit of any one organization. The 20 original members were later joined by 23 more countries (Burkina Faso, Cambodia , Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Dominican Republic, Fiji , Grenada, Guatemala, Haiti , Honduras, Malawi, Marshall Islands, Mongolia, Morocco, Niger, Palau , Papua New Guinea , Senegal, South Sudan, Sri Lanka , Sudan, Tunisia and Yemen).

In Paris , President Aquino pledged a whopping 70% in reduction of carbon emissions by the Philippines, while approving the operation of at least 27 coal-fired power plants, no more than a month after the UN Climate conference, to insure the provision of electricity to the country. Upon his arrival at the Philippine presidency, Rodrigo Duterte announced he was not bound by the “crazy pledges” of his predecessor and would honor the 70% commitment, preferring to re-think the country’s priorities and the right balance between climate change protection and the need to provide economic development tools (energy) for the country.

Such as the May 2015 Climate Vulnerability Regional Forum in Manila attended by delegates from Afghanistan, Cambodia , Maldives, Mongolia, Myanmar, Pakistan , Papua New Guinea , Tajikistan, Timor Leste and Vietnam .

As well as other environmental laws such as the Renewable Energy Act, the Solid Waste Management Act and the Environmental Awareness Education Act.

http://www.pagasa.dost.gov.ph / (Pagasa national weather service), http://weather.com.ph/weathertv/ , http://www.hurricanezone.net/ all offer detailed information about active typhoons

“Resilience Capacity Building for Cities and Municipalities to Reduce Disaster Risks from Climate Change and Natural Hazards”

http://blog.noah.dost.gov.ph/noah-open-file-reports/

Resiliency is another, much less used, form of this word. Resiliency is used mostly in North America, as an alternate to resilience

Etymologically it is derived from “Bathala”, the ancient Supreme Being worshiped by Filipinos during the pre-Spanish Period. It is akin to the Arabic/Muslim expression “Inshallah” (at the will of God)

A word derived from kapwa , a Tagalog term widely used when addressing another with the intention of establishing a connection. Kapwa looks for what people have in common as human beings, not as rich or poor, young or old, man, woman or child. According to this thinking, people always remain just people (“ tao lang ”) despite titles, prestigious positions or wealth, or abject poverty. What really matters is their behavior and their ethics. The essence of humanity is recognizable in everyone, linking (including) people rather than separating (excluding) them from each other.

Pagpapanday ng Kalakasan (finding and cultivating strengths); Paghahanap ng Kalutasan at Kaagapay (seeking solutions and support); Pangangalaga sa Katawan (managing physical reactions); Pagsasaayos ng Kalooban at Isipan (managing thoughts and emotions); Pagsasagawa ng Kapakipakinabang na Gawain (engaging in regular and positive activities); Pag-usad sa Kinabukasan (moving forward).

Abreo N (2016) Ingestion of marine plastic debris by Green Turtle ( Chelonia mydas ) in Davao Gulf, Mindanao, Philippines. Philipp J Sci 145(1):17–23

Google Scholar

Adger N (2000) Social and ecological resilience: are they related? Prog Hum Geogr 24(3):347–364

Article Google Scholar

Adger N (2006) Vulnerability. Glob Environ Chang 16(3):268–281

Adger N, Brooks N (2003) Does global environmental change cause vulnerability to disaster? In: Pelling M (ed) Natural disaster and development in a globalising world. Routledge, New York, pp 325–352

Adviento ML, De Guzman J (2010) Community resilience during Typhoon Ondoy: the case of Ateneoville. Philipp J Psychol 43(1):101–113

Alave K (2011) Sendong disaster foretold three years ago. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 20 Dec 2011

Alegado J (2015) Philippines, a leader in climate change policies—UNDP. Rappler, 21 May 2015

Allen K (2006) Community-based disaster preparedness and climate adaptation: local capacity building in the Philippines. Disasters 30(1):81–101

Ambal R et al (2012) Key biodiversity areas in the Philippines: priorities for conservation. J Threat Taxa 4(8):2788–2796

Ambanta J (2013) Disaster readiness in Asia low. Manila Standard, 2 Jul 2013

Anacio D et al (2016) Dwelling structures in a flood-prone area in the Philippines: sense of place and its functions for mitigating flood experiences. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 15:108–115

Ancog R, Florece L, Nicopior O (2016) Fire occurrence and fire mitigation strategies in a grassland reforestation area in the Philippines. Forest Policy Econ 64:35–45

Andres T (2002) People empowerment by Filipino values. Rex Book Store, Manila, 173 p

Appleton JD et al (1999) Mercury contamination associated with artisanal gold mining on the island of Mindanao, the Philippines. Sci Total Environ 228(2–3):95–109

Appleton JD et al (2006) Impacts of mercury contaminated mining waste on soil quality, crops, bivalves, and fish in the Naboc River area, Mindanao, Philippines. Sci Total Environ 354(2–3):198–211

Aragones L (1994) Observations on dugongs at Calauit Island, Busuanga, Palawan, Phillipines. Wildl Res 21(6):709–717

Aragones L et al (2010) The Philippine Marine Mammal Strandings from 1998 to 2009: animals in the Philippines in Peril? Aquat Mamm 36(3):219–233

Arellano-Carandang ML, Nisperos MK (1996) Pakikipagkapwa-damdamin: accompanying survivors of disasters. Bookmark, Makati, 140p

Asio V (1997) A review of upland agriculture, population pressure, and environmental degradation in the Philippines. Ann Trop Res 19(1):1–18

Asio V, Jahn R, Stahr K, Margraf J (1998) Soils of the tropical forests of Leyte, Philippines. II: impact of different land uses on status of organic matter and nutrient availability. In: Schulte A, Ruhiyat D (eds) Soils of tropical forest ecosystems: characteristics, ecology and management. Springer, Berlin, pp 37–44

Chapter Google Scholar

Asio V, Jahn R, Stahr K (1999) Changes in the properties of a volcanic soil in Leyte due to conversion of forest to other land uses. Philipp J Sci 128(1):1–13

Asio V et al (2009) A review of soil degradation in the Philippines. Ann Trop Res 31(2):69–94

Asuero M et al (2012) Social characteristics and vulnerabilities of disaster-prone communities in Infanta, Quezon, Philippines. J Environ Sci Manage 15(2):19–34

Bagarinao R (2010) Forest fragmentation in central cebu and its potential causes: a landscape ecological approach. J Environ Sci Manage 13(2):66–73

Bankoff G (2002) Cultures of disaster: society and natural hazard in the Philippines. Routledge, New York, 256p

Book Google Scholar

Bankoff G (2003) Cultures of coping: adaptation to hazard and living with disaster in the Philippines. Philipp Sociol Rev 51(1):1–16

Bankoff G (2004a) “The tree as the enemy of man”: changing attitudes to the forests of the Philippines, 1565–1989. Philipp Stud 52(3):320–344

Bankoff G (2004b) In the eye of the storm: the social construction of the forces of nature and the climatic and seismic construction of god in the Philippines. J SE Asian Stud 35(1):91–111

Bankoff G (2007a) One island too many: reappraising the extent of deforestation in the Philippines prior to 1946. J Hist Geogr 33(2):314–334

Bankoff G (2007b) Living with risk, coping with disasters. Hazard as a frequent life experience in the Philippines. Edu About Asia 12(2):26–29

Bankoff G (2007c) Dangers to going it alone: social capital and the origins of community resilience in the Philippines. Contin Chang 22(2):327–355

Bankoff G (2009) Breaking new ground? Gifford Pinchot and the birth of “empire forestry” in the Philippines, 1900–1905. Environ Hist 15(3):369–393

Barrameda T, Barrameda A (2011) Rebuilding communities and lives: the role of damayan and bayanihan in disaster resiliency. Philipp J Soc Dev 3:1–13

Bautista G (1990) The forestry crisis in the Philippines: nature, causes and issues. Dev Econ XXVIII(1):67–94

Bawagan A et al (2015) Shifting paradigms: strengthening institutions for community-based disaster risk reduction and management. University of the Philippines, Quezon City, 225p

Bensel T (2008) Fuelwood, deforestation and land degradation: 10 years of evidence from Cebu province, the Philippines. Land Degrad Dev 19:587–605

Bergonia T (2011) Are Filipinos prepared for the Big One? Philippine Daily Inquirer, 14 Mar 2011

Berlin K (2016) PH leads the way in global fight vs climate change. Rappler, 14 Mar 2016

Bernad M (1957) Our dwindling forests. Philipp Stud 5(1):87–92

Birkmann J et al (2008) Extreme events and disasters: a window of opportunity for change? Analysis of organizational, institutional and political changes, formal and informal responses after mega-disasters. Nat Hazards 55(3):637–669

Boehnert T (2011) Illegal logging causes flash floods, landslides in N. Vizcaya. Daily Tribune, 28 Mar 2011

Bostrom L (1968) Filipini bahala na and American fatalism. Silliman J 15(3):399–413

Boussekey M (2000) An integrated approach to conservation of the Philippine or Red-vented cockatoo Cacatua haematuropygia . Int Zoo Yearb 37(1):137–145

Bracamonte N, Ponce S, Roxas A (2010) Rainforestation project in the Mt. Malindang Range Natural Park: socioeconomic effects a year hence. Mindanao Forum XIII(2):51–78

Bravante M, Holden W (2009) Going through the motions: the environmental impact assessment of nonferrous metals mining projects in the Philippines. Pac Rev 22(4):523–547

Broad R, Cavanagh J, Ehrenreich B (eds) (1993) Plundering paradise: the struggle for the environment in the Philippines. University of California Press, Berkeley, 240p

Brooks T et al (2002) Habitat loss and extinction in the hotspots of biodiversity. Conserv Biol 16(4):909–923

Brown R et al (2013) Evolutionary processes of diversification in a Model Island Archipelago. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 44:411–435

Bryant R (2000) Politicized moral geographies: debating biodiversity and ancestral domain in the Philippines. Polit Geogr 19(6):673–705

Bryant R (2001) Explaining state-environmental NGO relations in the Philippines and Indonesia. Singap J Trop Geogr 22(1):15–37

Bueser G et al (2003) Distribution and nesting density of the Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi on Mindanao Island, Philippines: what do we know after 100 years? Ibis 145:130–135

Button C et al (2013) Vulnerability and resilience to climate change in Sorsogon City, the Philippines: learning from an ordinary city? Local Environ Int J Justice Sustain 18(6):705–722

Cadag J, Gaillard J-C (2012) Integrating knowledge and actions in disaster risk reduction: the contribution of participatory mapping. Area 44(1):100–109

Cagalanan D (2015) Governance challenges in community-based forest management in the Philippines. Soc Nat Res Int J 28(6):609–624

Cairns M (1997) Ancestral domain and national park protection: mutually supportive paradigms? A case study of the Mt. Kitanglad Range National Park, Bukidnon, Philippines. Philipp Q Cult Soc 25(1/2):31–82

Camacho L et al (2012) Traditional forest conservation knowledge/technologies in the Cordillera, Northern Philippines. Forest Policy Econ 22:3–8

Campbell A, Siepen G (1994) Landcare: communities shaping the land and the future. Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 344p

Capili E, Ibay A, Villarin J (2005) Climate change impacts and adaptation on Philippine coasts. In: Proceedings of the international oceans 2005 conference, Washington, DC, pp 1–8

Carandang ML (1996). Pakikipagkapwa-damdamin: Accompanying survivors of disasters. Bookmark, Makati 140p

Carandang A et al (2012) Analysis of key drivers of deforestation and forest degradation in the Philippines. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), Bonn. 110p

Carrion M (2010) Redefining development: the living advocacy of Loren Legarda UNISDR Champion for Asia-Pacific. United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, Asia and the Pacific (UNISDR), Bangkok. 180p

Catibog-Sinha C (2011) Sustainable forest management: heritage tourism, biodiversity, and upland communities in the Philippines. J Herit Tour 6(4):341–352

Catibog-Sinha C, Heaney L (2006) Philippine biodiversity: principles and practice. Haribon Foundation for the Conservation of Natural Resources, Quezon City, 495p

Combalicer M et al (2011) Changes in the forest landscape of Mt. Makiling Forest Reserve. Philipp Forest Sci Tech 7(2):60–67

Combest-Friedman C, Christie P, Miles E (2012) Household perceptions of coastal hazards and climate change in the Central Philippines. J Environ Manag 112:137–148

Coxhead I, Shively G, Shuai X (2001) Agricultural development policies and land expansion in a Southern Philippine Watershed. In: Angelsen A, Kaimowitz D (eds) Agricultural technologies and tropical deforestation. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, pp 347–366

Cramb R (1998) Environment and development in the Philippine uplands: the problem of agricultural land degradation. Asian Stud Rev 22(3):289–308

Cramb R, Garcia J, Gerrits R, Saguiguit G (1999) Smallholder adoption of soil conservation technologies: evidence from upland projects in the Philippines. Land Degrad Dev 10(5):405–423

Cramb R, Garcia J, Gerrits R, Saguiguit G (2000) Conservation farming projects in the Philippine uplands: rhetoric and reality. World Dev 28(5):911–927

Cruz W, Francisco H, Conway Z (1988) The on-site and downstream costs of soil erosion in the Magat and Pantabangan Watersheds. J Philipp Dev XV(1):85–112

Cruz MC, Zosa-Ferranil I, Goce CL (1998) Population pressure and migration: implications for upland development in the Philippines. J Philipp Dev 15(26):15–46

Cuadra C et al (2014) Development of Inundation Map for Bantayan Island, Cebu Using Delft3D-Flow Storm Surge Simulations of Typhoon Haiyan. Project NOAH Open File Rep 3(5):37–44. http://d2lq12osnvd5mn.cloudfront.net/bantayan_ss.pdf

Custodio C, Molinyawe N (2001) The NIPAS law and the management of protected areas in the Philippines: some observations and critique. Silliman J 42(1):202–228

Cyrulnik B (1999) Un merveilleux malheur. Odile Jacob, Paris, 218p

Dalabajan D, Caspe AM (2014) Bearing the cost of climate adaptation: hollande’s historic opportunity. Rappler, 2 Mar 2015

David W (1988) Soil and water conservation planning: policy issues and recommendations. J Philipp Dev XV(1):47–84

De Castro E (2011) Typhoon Sendong: did illegal logging cause flash flooding in Philippines? Christian Science Monitor, 20 Dec 2011

De La Cruz G (2014a) Looking back: the 1968 Casiguran earthquake. Rappler, 2 Aug 2014

De La Cruz G (2014b) How vulnerable is Manila to earthquakes? Rappler, 30 Nov 2014

De La Cruz G (2015a) How do you use local disaster funds? Rappler, 28 Feb 2015

De La Cruz G (2015b) Island communities: are they forgotten in disaster reduction efforts? Rappler, 7 Mar 2015

De La Cruz R (2015c) Restoring the lost forest of Sierra Madre. Manila Bulletin, 23 Sept 2015

De La Paz C (2016) Investors in mining panic over Gina Lopez appointment. Rappler, 22 June 2016

Del Rosario Cuunjieng N (2013) Do not say that the ‘Filipino spirit is waterproof. Manila Times, 17 Nov 2013

Delfin F, Gaillard J-C (2008) Extreme vs. quotidian: addressing temporal dichotomies in Philippine disaster management. Public Adm Dev 28(3):190–199

Delica-Willison Z, Willison R (2004) Vulnerability reduction: a task for the vulnerable people themselves. In: Bankoff G, Frerks G, Hilhorst D (eds) Mapping vulnerability: disasters, development and people. Earthscan, London, pp 145–158

Diamond J (2011) Collapse: how societies choose to fail or succeed. Penguin Books, London, 608p

Diola C (2014a) Manila among world’s least resilient cities. Philippine Star, 9 Apr 2014

Diola C (2014b) Phivolcs chief warns 7.2 quake can isolate Manila. Philippine Star, 16 Jul 2014

Diola C (2015) Are you in a Metro Manila earthquake zone? Philippine Star, 20 May 2015

Doedens A, Persoon G, Wedda C (1995) The relevance of ethnicity in the depletion and management of forest resources in Northeast Luzon, Philippines. Sojourn J Soc Issues SE Asia 10(2):259–279

Dolom B, Serrano R (2005) The Ikalahan: traditions bearing fruit. In: Duerst P et al (eds) In search of excellence. Exemplary forest management in Asia and the Pacific. FAO Asia-Pacific Forestry Commission, Bangkok, pp 83–92

Drash G et al (2001) The Mt. Diwata study on the Philippines 1999—assessing mercury intoxication of the population by small scale gold mining. Sci Total Environ 267:151–168

Dregne H (1992) Erosion and soil productivity in Asia. J Soil Water Conserv 47(1):8–13

Dressler W, Kull C, Meredith T (2006) The politics of decentralizing national parks management in the Philippines. Polit Geogr 25(7):789–816

Dulce L (2014) Defenders of one of last remaining old forests need our support. Bulatlat, 7 May 2014

Eder J (1990) Deforestation and detribalization in the Philippines: the Palawan case. Popul Environ 12(2):99–115

Eder J, Fernandez J (eds) (1997) Palawan at the crossroads: development and the environment on a Philippine Frontier. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 184p

Eigenheer K (1995) La forêt de Palawan: quel avenir? Le Globe. Revue Genevoise de Géographie 135:131–143

Enriquez V (1986) Kapwa: a core concept in Filipino social psychology. In: Enriquez V (ed) Philippine world-view. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, pp 6–19

Espina E, Teng-Calleja M (2015) A Social Cognitive Approach to Disaster Preparedness. Philipp J Psychol 48(2):161–174

Esplanada J (2015) Real disaster risk reduction challenge in PH is at local level. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 19 Mar 2015

Faustino-Eslava D et al (2013) Geohazards, tropical cyclones and disaster risk management in the Philippines: adaptation in a changing climate regime. J Environ Sci Manage 16(1):84–97

Fernandez R (2013) Leyte island now Phl’s ‘disaster capital’—studies. Philippine Star, 22 Dec 2013

Fernandez G, Shaw R (2013) Youth council participation in disaster risk reduction in Infanta and Makati, Philippines: a policy review. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 4(3):126–136

Flores H (2011) Phivolcs: several Metro Manila areas prone to liquefaction. Philippine Star, 24 Mar 2011

Flores H, Romero A (2016) Rising sea levels threaten 13.6 M Pinoys. Philippine Star, 15 Mar 2016

Francesco K (2015a) MMDA pushes for metrowide earthquake drill. Rappler, 22 May 2015

Francesco K (2015b) MMDA wants consolidated earthquake plan for Metro Manila. Rappler, 28 May 2015

Gabieta J (2015) Guian inspiration for Paris climate summit. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 28 Feb 2015

Gaillard J-C (2010) Vulnerability, capacity and resilience: perspectives for climate and development policy. J Int Dev 22(2):218–232

Gaillard J-C (2015) People’s responses to disaster in the Philippines. Palgrave-McMillan, New York, 193p

Gaillard J-C, Cadag J (2009) From marginality to further marginalization: experiences from the victims of the July 2000 Payatas trashslide in the Philippines. J Disaster Risk Stud 2(3):197–215

Gaillard J-C, Liamzon C, Maceda E (2008) Catastrophes dites “naturelles” et développement: réflexions sur l’origine des désastres aux Philippines. Revue Tiers Monde 194(2):371–390

Gaither M, Rocha L (2013) Origins of species richness in the Indo-Malay-Philippine biodiversity hotspot: evidence for the centre of overlap hypothesis. J Biogeogr 40:1638–1648

Gavieta R, Onate C (1997) Building regulations and disaster mitigation: the Philippines. Build Res Inf 25(2):120–123

Geronimo G (2011) Earthquakes’ fiery aftermath. Manila Standard, 12 Apr 2011

Gonzalez J (2011) Enumerating the ethno-ornithological importance of philippine hornbills. Raffles Bull Zool 24:149–161

Gripaldo R (2005) Bahala na [come what may]: a philosophical analysis. In: Gripaldo R (ed) Filipino cultural traits. The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, Washington, DC, pp 203–220

Guevara J (2005) Pakikipagkapwa [sharing/merging oneself with others]. In: Gripaldo R (ed) Filipino cultural traits. The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, Washington, DC, pp 9–20

Guiang E (2001) Impacts and effectiveness of logging bans in natural forests: Philippines. In: Durst P (ed) Forests out of bound. Impacts and effectiveness of logging bans in natural forests in Asia-Pacific. FAO Asia-Pacific Forestry Commission, Bangkok, pp 103–136

Hauge P, Terborgh J, Winter B, Parkinson J (1987) Conservation priorities in the Philippine Archipelago. Forktail 2:83–91

Hayami Y (1976) Agricultural growth against a land resource constraint: the Philippine experience. Austr J Agr Econ 20(3):144–159

Headland T (1988) Ecosystemic change in a Philippine tropical rainforest and its effect on a Negrito foraging society. Trop Ecol 29(2):121–135

Hechanova MR (2014) Resilience, more than reliving experience, crucial for disaster survivors. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 26 Nov 2014

Hechanova MR et al (2015) The development and initial evaluation of Katatagan : a resilience intervention for filipino disaster survivors. Philipp J Psychol 48(2):105–131

Heijmans A, Victoria L (2001) Citizenry-based and development oriented disaster response: experiences and practices in disaster management of the Citizens’ Disaster Response Network in the Philippines. Center for Disaster Preparedness, Quezon City, 171p

Hodgson G, Dixon J (1988) Logging versus fisheries and tourism in Palawan. East-West Environ Policy Inst, Honolulu, 95p

Holden W (2005) Civil society opposition to Nonferrous Metals Mining in the Philippines. Volunt Int J Volunt Nonprofit Org 16(3):223–249

Holden W, Jacobson D (2007) Ecclesial opposition to nonferrous metals mining in the Philippines: neoliberalism encounters liberation theology. Asian Stud Rev 31(2):133–154

Holden W, Jacobson D (2012) Mining and natural hazard vulnerability in the Philippines: digging to development or digging to disaster? Anthem Press, London, 306p

Holden W, Nadeau K, Jacobson D (2011) Exemplifying accumulation by dispossession: mining and indigenous peoples in the Philippines. Geogr Ann Ser B 93(2):141–161

Horigue V, Aliño P, White A, Pressey R (2012) Marine protected area networks in the Philippines: trends and challenges for establishment and governance. Ocean Coast Manag 64:15–26

Hume N (2016) Nickel at 9-month high on Philippine environmental fears. Financial Times, 12 Jul 2016

Innocenti D, Albrito P (2011) Reducing the risks posed by natural hazards and climate change: the need for a participatory dialogue between the scientific community and policy makers. Environ Sci Pol 14(7):730–733

Ishihara S (2015) Long-term community-based monitoring of tamaraw Bubalus mindorensis . Oryx 49(2):352–359

Israel D, Asirot J (2000) Mercury pollution due to small-scale gold mining in the Philippines: an economic analysis. Discussion Paper No. 2000–06, Philippine Institute for Development Studies, Makati, 62p

Iuchi K, Esnard A-M (2008) Earthquake impact mitigation in poor urban areas. The case of Metropolitan Manila. Disaster Prev Manag 17(4):454–469

Izumi T, Shaw R (2012) Roles of stakeholders in disaster risk reduction under the hyogo framework for action: an asian perspective. Asian J Environ Disaster Manage 4(2):164–182

Jahn R, Asio V (1998) Soils of the tropical forests of Leyte, Philippines. I: weathering, soil characteristics, classification and site qualities. In: Schulte A, Ruhiyat D (eds) Soils of tropical forest ecosystems: characteristics, ecology and management. Springer, Berlin, pp 29–36

Janssen M, Schoon M, Weimao KE, Börner K (2006) Scholarly networks on resilience, vulnerability and adaptation within the human dimensions of global environmental change. Glob Environ Chang 16:240–252

Jose A, Cruz N (1999) Climate change impacts and responses in the Philippines: water resources. Clim Res 12:77–84

Klein R, Nicholls R, Thomalla F (2003) Resilience to natural hazards: how useful is this concept? Environ Hazards 5(1–2):35–45

Kummer D (1991) Deforestation in the post-war Philippines. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 201p

Kummer D (1992) Upland agriculture, the land frontier and forest decline in the Philippines. Agrofor Syst 18(1):31–46

Kummer D, Turner BL (1994) The human causes of deforestation in Southeast Asia. Bioscience 44(5):323–328

Kummer D, Concepcion R, Cañizares B (1994) Environmental DEgradation in the Uplands of Cebu. Geogr Rev 84(3):266–276

Kummer D, Concepcion R, Cañizares B (2003) Image and reality; exploring the puzzle of continuing environmental degradation on the uplands of Cebu, the Philippines. Philipp Q Cult Soc 31(3):135–155

La Viña A (2014) After more than 100 years of envitonemental law, what’s next for the Philippines? Philipp Law J 88:195–239

La Viña T, Romero P (2015) The Philippines’ influence on the Paris Agreement. Rappler, 31 Dec 2015

Lacuarta G (1997) RP Biodiversity fast disappearing. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 17 June 1997

Lagmay A (1993) Bahala na! Philipp J Psychol 26(1):31–36

Lagmay A (2016) The importance of hazard maps in averting disasters. Project NOAH Open File Reports 5(1):45–56. http://blog.noah.dost.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/hazard_map_atlas_lagmay.pdf

Lagmay A et al (2013a) Estimate of informal settlers at risk from storm surges vs. number of fatalities in Tacloban City. Project NOAH Open File Rep 1(6):21–23. http://blog.noah.dost.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/tacloban_estimation.pdf

Lagmay A et al (2013b) Devastating storm surges of Typhoon Yolanda. Project NOAH Open File Reports 3(6):45–56. http://d2lq12osnvd5mn.cloudfront.net/SS_yolanda.pdf

Lagsa B (2014) 8 M ha eyed for oil palm plantations. DENR chief says idle lands ideal palm sites. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 26 May 2014

Landa Jocano F (1969) Growing up in a Philippine Barrio. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, 160p

Lapidez JP et al (2014) Identification of storm surge vulnerable areas in the Philippines through simulations of Typhoon Haiyan-induced storm surge using tracks of historical typhoons. Project NOAH Open File Rep 3(1):112–131. http://blog.noah.dost.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/vol3_no1.pdf

Larsen R, Dimaano F, Pido M (2014) The emerging oil palm agro-industry in Palawan, the Philippines: livelihoods, environment and corporate accountability. Working Paper 2014–03, Stockholm Environment Institute, Stockholm, 46p

Lasco R (1998) Management of tropical forests in the Philippines: implications to global warming. World Resour Rev 10(3):410–418

Lasco R (2008) Tropical forests and climate change mitigation: the global potential and cases from the Philippines. Asian J Agric Dev 5(1):81–98

Lasco R, Pulhin F (2003) Philippine forest ecosystems and climate change: carbon stocks, rate of sequestration and the Kyoto Protocol. Ann Trop Res 25(2):37–51

Lasco R, Pulhin F (2009) Carbon budgets for forest ecosystems in the Philippines. J Environ Sci Manage 12(1):1–13

Lasco R, Visco RG, Pulhin F (2001) Secondary forests in the Philippines: formation and transformation in the 20th century. J Trop For Sci 13(4):652–670

Lasco R et al (2008) Climate change and forest ecosystems in the philippines: vulnerability, adaptation and mitigation. J Environ Sci Manage 11(1):–14

Le HD, Smith C, Herbohn J (2014) What drives the success of reforestation projects in tropical developing countries? The case of the Philippines. Glob Environ Chang 24:334–348

Legarda L (2016) The road to decarbonization. Rappler, 15 Mar 2016

Leoncini DL (2005) A conceptual analysis of pakikisama [getting along well with people]. In: Gripaldo R (ed) Filipino cultural traits. The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, Washington, DC, pp 185–202

Lim Ubac M (2012) UN lauds Philippines’ climate change laws as world’s best. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 4 May 2012

Lim Ubac M (2014) Why paralysis, systems collapse, chaos happened. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 15 Nov 2014

Lim Ubac M (2016) Gore warns PH of looming disaster. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 15 Mar 2016

Liu D, Iverson L, Brown S (1993) Rates and patterns of deforestation in the Philippines: application of geographic information system analysis. For Ecol Manag 57(1–4):1–16

Lozada D (2014) Gov’t adopts new strategy for climate change resiliency. Rappler, 8 Aug 2014

Lozada D (2015) Taguig leads nationwide earthquake drill. Rappler, 24 Jul 2015

Luna E (2001) Disaster mitigation and preparedness: the case of NGOs in the Philippines. Disasters 25(3):216–226

Luna E (2012) Bayanihan in disaster risk reduction for community development. University of the Philippines, Quezon City, 234p

Luna AC et al (1999) The community structure of a logged-over tropical rain forest in Mt Makiling Forest Reserve, Philippines. J Trop For Sci 11(2):446–458

Lusterio R (1996) Policy-making for sustainable development; the case of Makiling Forest Reserve. Philipp Soc Sci Rev 53(1–4)

Lusterio-Rico R (2013) Globalization and local communities: the mining experience in a Southern Luzon, Philippine Province. Philipp Polit Sci J 34(1):48–61

Luz Nelson G, Abrigo GN (2008) Disaster-related social behavior in the Philippines. UP Los Baños Journal 6(1)

Maceda E et al (2009) Experimental use of participatory 3-dimensional models in island community-based disaster risk management. Shima Int J Res Island Cult 3(1):72–84

Madulid D (1992) Mount Pinatubo: a case of mass extinction of plant species in the Philippines. Silliman Journal 36(1):113–121

Maguire B, Hagan P (2007) Disasters and communities: understanding social resilience. Aust J Emerg Manage 22(2):16–20

Mallari N et al (2016) Philippine protected areas are not meeting the biodiversity coverage and management effectiveness requirements of Aichi Target 11. Ambio 45(3):313–322

Manalo R, Alcala A (2015) Conservation of the Philippine crocodile Crocodylus mindorensis (Schmidt 1935): in situ and ex situ measures. Int Zoo Yearb 49(1):113–124

Mandawa A (2013) Philippines: oil palm expansion is tearing apart indigenous peoples lives. IC Magazine, 27 Mar 2013

Mangosing F (2015) Phivolds launches, distributes handbook on West Valley faultline in Metro Manila. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 18 May 2015

Manyena B (2006) The concept of resilience revisited. Disasters 30(4):434–450

Martinez-Villegas M (2011) Tsunami preparedness in PH. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 19 Mar 2011

Matsuoka Y, Shaw R (2011) Linking resilience planning to Hyogo Framework for Action in cities. In: Shaw R, Sharma A (eds) Climate and disaster resilience in cities. Emerald Group Publishing, Bingley, pp 129–148

Matsuoka Y, Shaw R (2012) Hyogo framework for action as an assessment tool of risk reduction: Philippines National Progress and Makati City. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 3(4):18–39

Matsuoka Y, Takeuchi Y, Shaw R (2013) Implementation of hyogo framework for action in Makati City, Philippines. Int J Disaster Resilience Built Environ 4(1):23–42

Mayuga J (2015) Adaptation and mitigation should go together. Business Mirror, 25 Oct 2015

Mayuga J (2016a) PHL center of pitcher-plant diversity. Business Mirror, 26 June 2016

Mayuga J (2016b) PHL will not see new mining projects under Lopez’s watch. Business Mirror, 11 Jul 2016

Mayuga J (2016c) PHL voice at UN key to global climate pact. Business Mirror, 24 Jul 2016

McGranahan G, Balk D, Anderson B (2007) The rising tide: assessing the risks of climate change and human settlements in low elevation coastal zones. Environ Urban 19(1):17–37

Menguito M, Teng-Calleja M (2010) Bahala Na as an Expression of the Filipino’s Courage, Hope, Optimism, Self-efficacy and Search for the Sacred. Philipp J Psych 43(1):1–26

Mercado A, Patindol M, Garrity D (2001) The landcare experience in the Philippines: technical and institutional innovations for conservation farming. Dev Pract 11(4):495–508

Mildenstein T et al (2005) Habitat selection of endangered and endemic large flying-foxes in Subic Bay, Philippines. Biol Conserv 126(1):93–102

Minter T et al (2012) Whose consent? hunter-gatherers and extractive industries in the Northeastern Philippines. Soc Nat Res Int J 25(12):1241–1257

Minter T et al (2014) Limits to indigenous participation: the Agta and the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, the Philippines. Hum Ecol Interdiscip J 42(5):769–778

Mittelmeier R et al (1998) Biodiversity hotspots and major tropical wilderness areas: approaches to setting conservation priorities. Conserv Biol 12(3):516–520

Miura H, Midorikawa S (2006) Updating GIS building inventory data using high-resolution satellite images for earthquake damage assessment: application to Metro Manila, Philippines. Earthquake Spectra 22(1):151–168

Miura H et al (2008) Earthquake damage estimation in Metro Manila, Philippines based on seismic performance of buildings evaluated by local experts’ judgments. Soil Dyn Earthq Eng 28(10–11):764–777

Mohagan A, Mohagan D, Tambuli A (2011) Diversity of butterflies in the selected key biodiversity areas of Mindanao, Philippines. Asian J Biodivers 2(11):121–148

Mondragon A (2015) Small islands, big problems: poverty, isolation increase vulnerability. Rappler, 19 Nov 2015

Mucke P et al (2014) World Risk Report 2014. Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft/United Nations University—Institute for Environment and Human Security, Berlin/Bonn, 74p. www.ehs.unu.edu/article/read/world-risk-report-2014

Myers N (1988a) Environmental Degradation and some economic consequences in the Philippines. Environ Conserv 15(3):205–214

Myers N (1988b) Threatened biotas: “Hot spots” in tropical forests. Environmentalist 8(3):187–208

Myers N et al (2000) Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403:853–858

Natividad S (2012) Daisy Paborada, taking on the fight from where her husband fell. Bulatlat, 8 Dec 2012

Nelson A et al (1996) A cost-benefit analysis of hedgerow intercropping in the Philippine uplands using the SCUAF model. Agrofor Syst 35(2):203–220

Nery L (1979) Pakikisama as a method: a study of a subculture. Philipp J Psychol 12(1):27–32

Neyra-Cabatac N, Pulhin J, Cabanilla D (2012) Indigenous agroforestry in a changing context: the case of the Erumanen ne Menuvu in Southern Philippines. Forest Policy Econ 22:18–27

Nuijten R (2016) The use of genomics in conservation management of the endangered Visayan warty pig ( Sus cebifrons ). Int J Genomics 2016:9. doi: 10.1155/2016/5613862

O’Callaghan T (2009) Regulation and governance in the Philippines Mining Sector. Asia Pac J Public Admin 31(1):91–114

Oliver W (1995) The taxonomy, distribution and status of Philippine wild pigs. J Mount Ecol 3:26–32

Oliveros B (2015) Is the Philippines prepared for another major disaster? Manila Times, 23 May 2015

Palafox F (2014) Waterfront coastal development. Manila Times, 3 Dec 2014

Palafox F (2016) Are we ready for a big quake? Manila Times, 20 Apr 2016

Pamintuan M (2011) Protect Philippine forests. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 5 June 2011

Panela S (2015) How close are you to the West Valley Fault? Here’s a site for that. Rappler, 28 May 2015

Paningbatan E, Ciesolka C, Coughlan K, Rose C (1995) Alley cropping for managing soil erosion of hilly lands in the Philippines. Soil Technol 8(3):193–204

Panti L (2014) Disaster preparedness has not taken root in Philippines. Manila Times, 8 Nov 2014

Parsons O (2016) Earthquake preparedness in the Philippines: the importance of simulations. GSMA, 13 May 2016

Pasicolan P, De Haes E, Sajise P (1997) Farm forestry: an alternative to government-driven reforestation in the Philippines. For Ecol Manag 99(1–2):261–274

Paterno B (2014) Learning from disaster: corruption and environmental catastrophe. Rappler, 9 Nov 2014

Pelling M (2007) Learning from others: the scope and challenges for participatory disaster risk assessment. Disasters 31(4):373–385

Pe-Pua R, Protacio-Marcelino E (2000) Sikolohiyang Pilipino (Filipino psychology). A legacy of Virgilio Enriquez. Asian J Soc Psychol 3:49–71

Perante W (2016) Validity and reproducibility of typhoon damage estimates using satellite maps and images. Asian J Appl Sci Eng 5(2):105–116

Pereira RA et al (2006) Forest clearance and fragmentation in Palawan and Eastern Mindanao Biodiversity Corridors (1990–2000): a time sequence analysis of Landsat Imagery. Banwa 3(1–2):130–147

Peres C, Schneider M (2012) Subsidized agricultural resettlements as drivers of tropical deforestation. Biol Conserv 151(1):65–68

Perez R et al (1996) Potential impacts of sea level rise on the coastal resources of Manila Bay: a preliminary vulnerability assessment. Water Air Soil Pollut 92(1–2):137–147

Perez R, Amadore L, Feir R (1999) Climate change impacts and responses in the Philippines coastal sector. Clim Res 12:92–107

Pimentel D (2006) Soil erosion: a food and environmental threat. Environ Dev Sustain 8(1):119–137

Porio E (2011) Vulnerability, adaptation, and resilience to floods and climate change-related risks among marginal, riverine communities in Metro Manila. Asian J Soc Sci 39:425–445

Porter G, Ganapin D (1988) Resources, population, and the Philippines’ future. A case study. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC, 68p

Posa MR et al (2008) Hope for threatened tropical biodiversity: lessons from the Philippines. Bioscience 58(3):231–240

Poudel D, Midmore D, West L (1999) Erosion and productivity of vegetable systems on sloping volcanic ash-derived Philippine soils. Soil Sci Soc Am J 63(5):1366–1376

Poudel D, Midmore D, West L (2000) Farmer participatory research to minimize soil erosion on steepland vegetable systems in the Philippines. Agric Ecosyst Environ 79(2–3):113–127

Presbitero A et al (1995) Erodability evaluation and the effect of land management practices on soil erosion from steep slopes in Leyte, the Philippines. Soil Technol 8(3):205–213

Presbitero A et al (2005) Investigation of soil erosion from bare steep slopes of the humid tropic Philippines. Earth Interact 9(5):1–30

Pulhin J, Tapia M (2005) History of a legend: managing the Makiling firest reserve. In: Duerst P et al (eds) In search of excellence. Exemplary forest management in Asia and the Pacific. FAO Asia-Pacific Forestry Commission, Bangkok, pp 261–269

Pulhin F, Reyes L, Pecson D (eds) (1998) Mega issues in Philippine forestry: key policies and programs. UPLB Forestry Development Center, Los Baños, 76p

Quismondo T (2012) St Bernard disaster-ready model after '06 earthquake. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 30 Sept 2012

Quismondo T (2015) Gore coming here to train PH climate warriors. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 15 Dec 2015

Rabor D (1971) The present status of conservation of the Monkey-eating Eagle of the Philippines. Philipp Geogr J 15:90–103

Ragragio A (2014) Why we should defend Pantaron. Davao Today, 14 Apr 2014

Ranada P (2013) What made Tacloban so vulnerable to Haiyan? Rappler, 15 Nov 2013

Ranada P (2014a) Climate change threatens economy of 4 PH cities. Rappler, 15 Jan 2014

Ranada P (2014b) 12-point checklist for an earthquake-resistant house. Rappler, 19 Feb 2014

Ranada P (2014c) Is the gov’t reforestation program planting the right trees? Rappler, 21 Feb 2014

Ranada P (2014d) PH natural parks management rated ‘poor’ to ‘fair’. Rappler, 26 Feb 2014

Ranada P (2014e) More than 5,000 PH villages have flood hazard maps—DOST. Rappler, 22 Jul 2014

Ranada P (2014f) Yolanda a year after: few LGUs asking for multi-hazard maps. Rappler, 28 Oct 2014

Ranada P (2015) High resolution West Valley Fault maps launched. Rappler, 18 May 2015

Rede-Blolong R, Olofson H (1997) Ivatan agroforestry and ecological history. Philipp Q Cult Soc 25(1/2):94–123

Rey A (2015) LGUs frustrated over delayed use of People’s Survival Fund. Rappler, 30 May 2015

Rietbroek R et al (2016) Revisiting the contemporary sea-level budget on global and regional scales. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113(6):1504–1509

Roces M et al (1992) Risk factors for injuries due to the 1990 earthquake in Luzon, Philippines. Bull World Health Organ 70(4):509–514

Rodriguez F (2015a) What’s eating up Mindoro’s forests? If there really is no logging, then why are trees disappearing? Rappler, 10 Nov 2015

Rodriguez F (2015b) Mangyans and kaingin. How are indigenous people’s rights, kaingin, and the environment linked? Rappler, 10 Nov 2015

Rodriguez F (2015c) When there’s smoke, there’s fire? Rappler, 10 Nov 2015

Romero R (2014) Is Metro Manila ready for The Big One? Manila Standard, 25 Nov 2014

Rosales A (2011) Phivolcs’ dire forecast: quake anytime this year. Daily Tribune, 17 Mar 2011

Sabillo K (2015) PH to lead vulnerable countries in climate change fight—French envoy. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 20 May 2015

Salamat M (2012a) Philex’s ‘responsible mining’ put to test in tailings dam spill. Bulatlat, 7 Aug 2012

Salamat M (2012b) Mindanao lumad, green groups blame Aquino’s mining policies for devastation wreaked by typhoon Pablo. Bulatlat, 8 Dec 2012

Sales R (2009) Vulnerability and adaptation of coastal communities to climate variability and sea-level rise: their implications for integrated coastal management in Cavite City, Philippines. Ocean Coast Manag 52(7):395–404

Salvador D, Ibañez J (2006) Ecology and conservation of Philippine Eagles. Ornithol Sci 5(2):171–176

Santos P (2011) MMDA eyeing big golf courses as evacuation centers in case of major earthquake. Daily Tribune, 24 Mar 2011

Saxena S (2016) Ocean levels in the Philippines rising at 5 times the global average. http://arstechnica.com/science/2016/02/ocean-levels-in-the-philippines-rising-at-five-times-the-global-average/

Schmitt Olabisi L (2012) Uncovering the Root Causes of Soil Erosion in the Philippines. Soc Nat Res Int J 25(1):37–51

See D (2014) Logger denude Mt Pulag. Daily Tribune, 13 June 2014

Serrano J (2015) Site seeing in virtual social space; uses of posts in times of disaster. J NatStud 14(2):96–103

Serrano R, Cadaweng E (2005) The Ifugao Muyong: sustaining water, culture and life. In: Duerst P et al (eds) In search of excellence. Exemplary forest management in Asia and the Pacific. FAO Asia-Pacific Forestry Commission, Bangkok, pp 103–112

Sheeran K (2006) Forest conservation in the Philippines: a cost-effective approach to mitigating climate change? Ecol Econ 58:338–349

Shively G, Martinez E (2001) Deforestation, irrigation, employment and cautious optimism in Southern Palawan, the Philippines. In: Angelsen A, Kaimowitz D (eds) Agricultural technologies and tropical deforestation. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, pp 335–346

Siebert S (1987) Land use intensification in tropical uplands: effects on vegetation, soil fertility and erosion. For Ecol Manag 21(1–2):37–56

Siler C et al (2014) Cryptic diversity and population genetic structure in the rare, endemic, forest-obligate, slender geckos of the Philippines. Mol Phylogenet Evol 70:204–209

Sison S (2014) The problem with Filipino resilience. Rappler, 30 Oct 2014

Smit B, Wandel J (2006) Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Glob Environ Chang 16:282–292

Solmerin F (2012) Illegal loggers still at it in ‘timber corridor’. Manila Standard, 26 Jul 2012

Suarez R, Sajise P (2010) Deforestation, Swidden Agriculture and Philippine Biodiversity. Philipp Sci Lett 3(1):91–99

Sy Egco J (2016) Less than 1 percent of LGUs ready for disasters. Manila Times, 6 Jul 2016

Tablazon J et al (2014) Developing an early warning system for storm surge inundation in the Philippines. Project NOAH Open File Rep 3(7):57–72. http://d2lq12osnvd5mn.cloudfront.net/SS_warning_system.pdf

Talavera C (2015) Big One to waste Metro. Manila Times, 21 Jul 2015

Teehankee J (1993) The state, illegal logging, and environmental NGOs, in the Philippines. Kasarinlan Philipp J Third World Stud 9(1):19–34

Torrevillas D (2015) Preparing for the ‘Big One’. Philippine Star, 4 June 2015

Tuason MT (2010) The poor in the Philippines—some insights from psychological research. Psychol Dev Soc 22(2):299–330

Tumaneng-Diete T, Ferguson I, Mac Laren D (2005) Log export restrictions and trade policies in the Philippines: bane or blessing to sustainable forest management? Forest Policy Econ 7(2):187–198

Tupaz V (2013a) Climate change resilience starts in the village. Rappler, 27 Jul 2013

Tupaz V (2013b) Defining resilience to climate change. Rappler, 31 Jul 2013

Urich P (2000) Deforestation and declining irrigation in Bohol. Philipp Q Cult Soc 28(4):476–497

Urich P, Day M, Lynagh F (2001) Policy and practice in karst landscape protection: Bohol, the Philippines. Geogr J 167(4):305–323

Usamah M, Handmer J, Mitchell D, Ahmed I (2014) Can the vulnerable be resilient? co-existence of vulnerability and disaster resilience: informal settlements in the Philippines. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 10:178–189

Van Der Ploeg J, Araño R, Van Weerd M (2011a) What local people think about crocodiles: challenging environmental policy narratives in the Philippines. J Environ Dev 20(3):303–328

Van Der Ploeg J, Van Weerd M, Masipiqueña A, Persoon G (2011b) Illegal logging in the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, the Philippines. Conserv Soc 9(3):202–215

Van Weerd M (2010) Philippine Crocodile Crocodylus mindorensis . In: Manolis C, Stevenson C (eds) Crocodiles. Status survey and conservation action plan. Crocodile Specialist Group, Darwin, pp 71–78

Verburg P et al (2006) Analysis of the effects of land use change on protected areas in the Philippines. Appl Geogr 26(2):153–173

Vergano D (2013) 5 Reasons the Philippines Is So Disaster Prone. National Geographic News, 12 Nov 2013

Vickers M, Kouzmin A (2001) “Resilience” in organisational actors and rearticulating “voice”: towards a critique of new public management. Public Manage Rev 3(1):95–119

Victoria L (2003) Community-based disaster management in the Philippines: making a difference in people’s lives. Philipp Sociol Rev 51(1):65–80

Victoria L (2008) Combining indigenous and scientific knowledge in the Dagupan City Flood Warning System. In: Shaw R (ed) Indigenous knowledge for disaster risk reduction: good practices and lessons learned from experiences in the Asia-Pacific Region. UN ISDR Asia and Pacific, Bangkok, pp 52–54

Villanueva J (2006) Assessing the role of landcare in enhancing adaptive capacity in the communities in Claveria, Misamis oriental, to climate variability. Master of Science in Geography, University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City, 222p

Villanueva J (2011) Oil palm expansion in the Philippines analysis of land rights, environment and food security issues. In: Colchester M, Chao S (eds) Oil palm expansion in South East Asia: trends and implications for local communities and indigenous peoples. Forest Peoples Program, Moreton-in-Marsh, pp 110–216

Wallace B (2011) Village-based Illegal Logging in Northern Luzon. Asia-Pac Soc Sci Rev 11(2):19–26

Wee DT (2013) Oil palm farming pushed in Mindanao. Business World Online, 22 May 2013

White A, Courtney C, Salamanca A (2010) Experience with marine protected area planning and management in the Philippines. Coast Manag 30(1):1–26

Williams T et al (1999) Assessment of mercury contamination and human exposure associated with coastal disposal of waste from a cinnabar mining operation, Palawan, Philippines. Environ Geol 39(1):51–60

Yamsuan C, Alave K (2011) Climate change blamed for storms, flooding, drought. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2 Oct 2011

Yap DJ (2012) What if 7.6 quake hit Metro Manila? Philippine Daily Inquirer, 5 Sept 2012

Zurbano J (2015a) If mega-quake hits, golf courses on tap. Manila Standard, 21 May 2015

Zurbano J (2015b) Govt starts marking paths of Metro faults. Manila Standard, 20 June 2015

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Département de Géographie, Université de Bourgogne, Dijon, France

Yves Boquet

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Boquet, Y. (2017). Environmental Challenges in the Philippines. In: The Philippine Archipelago. Springer Geography. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51926-5_22

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51926-5_22

Published : 21 April 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-51925-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-51926-5

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Earth and Environmental Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Climate Change

- Policy & Economics

- Biodiversity

- Conservation

Get focused newsletters especially designed to be concise and easy to digest

- ESSENTIAL BRIEFING 3 times weekly

- TOP STORY ROUNDUP Once a week

- MONTHLY OVERVIEW Once a month

- Enter your email *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

How Did the Philippines Become the World’s Biggest Ocean Plastic Polluter?

As summer vacation commences, tourists are bound to flock to the Philippines, a nation known for its iconic islands that house some of the world’s whitest sands and most transparent waters. Unfortunately, the Asian nation has also made waves by being crowned as the world’s biggest ocean plastic polluter. In this article, we dive into the persistent plastic pollution in the country’s waters.

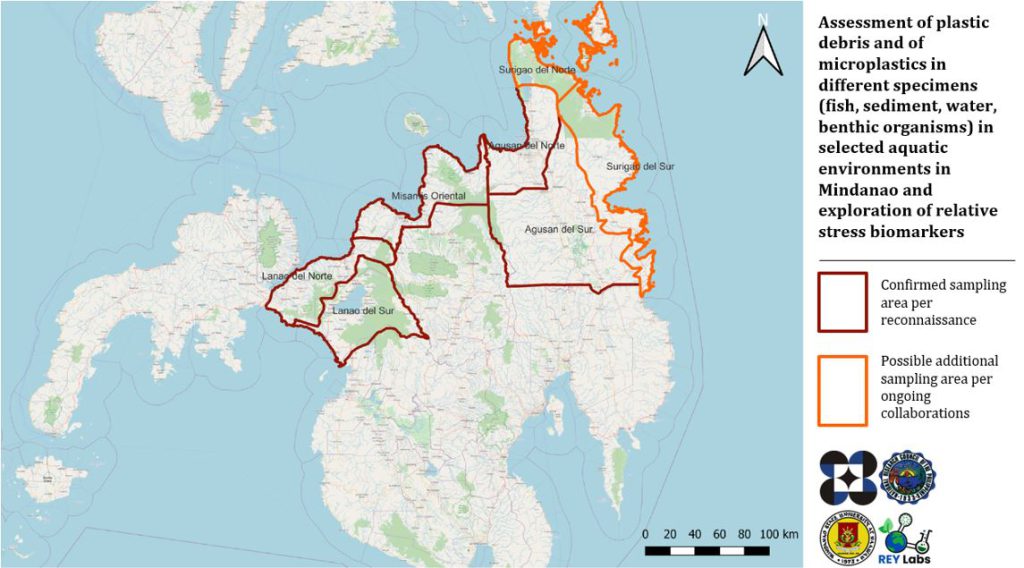

Assessing Ocean Plastic Pollution in the Philippines

The Philippines had the largest share of global plastic waste discarded in the ocean in 2019. The country was responsible for 36.38% of global oceanic plastic waste, far more than the second-largest plastic polluter, India, which in the same year accounted for about 12.92% of the total.

Contrary to popular belief, most plastic waste does not enter the sea directly. Conversely, it makes its way to the sea from smaller water streams.

According to a 2021 study , 80% of plastic waste comes from rivers and seven of the top ten plastic-polluted rivers in the world are in the Philippines. Pasig River even dethrones the previously most polluted river in 2017 , the Yangtze River of China.

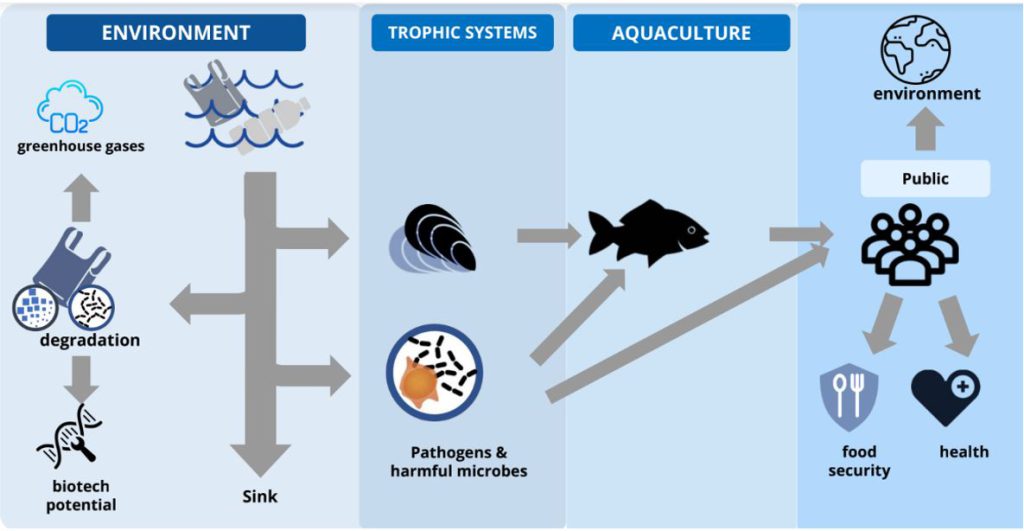

How Does Plastic Pollution Affect the Environment?

The Philippines prides itself on having one of the world’s most diverse marine biodiversity. By being at the apex of the Coral Triangle, the country holds an extensive system of coral reefs occupying more than 27,000 square kilometres (10,425 square miles).

Dubbed the “rainforest of the sea”, coral reefs are the essence of marine ecosystems , with 25% of the ocean’s fish relying on them for shelter, food, and reproduction.

Unfortunately, this centralisation of dependence is easily overthrown once coral reefs encounter threats such as rising ocean temperatures and plastic pollution.

A 2018 study showed that, without the presence of plastic, coral reefs have a 4% likelihood of contracting a disease. With plastic, the risk dramatically increases to 89% due to the spread of pathogens.

This phenomenon triggers a chain reaction, as it disrupts marine ecosystems and causes nearby sea animals to consume microplastics. Microplastics are smaller pieces of plastic generated through processes such as weathering and exposure to wave action and more. Their consumption is evidently persisting in the Philippines, where nearly half of all rabbitfish , a commonly consumed fish species, were found to contain traces of microplastics.

By dumping plastics into the sea, these eventually enter our bloodstream. According to the United Nations, more than 51 trillion microplastic particles litter the world’s seas, a quantity that outnumbers the stars in our galaxy by 500 times.

While we are increasingly aware of where microplastics can be found, we are still relatively in the dark about their impact on the environment and especially on human health. Yet, there is no doubt that microplastics contain highly toxic and harmful chemicals.

You might also like: 5 Coral Reefs That Are Currently Under Threat and Dying

What’s Behind the Philippines’ Plastic Pollution Crisis?

The Philippines has a peculiar culture of consuming products in small quantities. For example, instead of buying a regular bottle of shampoo, many people opt for sachets sold at local stores at a much lower price.

With a reported 20 million people living below the poverty line in 2021, the country’s widespread poverty leaves citizens hunting for the cheapest alternative. Large corporations exploit this situation by offering palm-sized packages of products and building a “sachet economy”, further exacerbating plastic pollution in the country.

Nonetheless, it is said that there is no other material that offers safer and quicker transportation of food like plastic does.

Instead of merely focusing on reducing plastic use, governments should also consider increasing the accessibility to proper disposal facilities. Indeed, the head of Philippine Alliance for Recycling and Materials Sustainability Crispian Lao states that 70% of Filipinos lack access to disposal facilities, which steers plastic waste directly to oceans. With minimal exposure to environmentally-friendly options for plastic disposal, the population often lacks awareness of plastic pollution.

This highlights another problem: The lack of government action.

Among the reasons behind plastic pollution being such a big issue in the Philippines is government mismanagement. More specifically, the government is criticised for merely having good laws surrounding waste disposal but often failing to properly enforce them .

In 2001, the government established the Waste Management Act to tackle the nation’s growing solid waste problem through methods such as prohibition of open dumps for solid waste and by adopting systematic waste segregation. Two decades later, the Commission on Audit stated that there has still been a “steady” increase in waste generation.

You might also like: 4 Biggest Environmental Issues in the Philippines in 2024

How Do We Fix This?

In the grand scheme of things, most of the causes of plastic pollution could be addressed with proper government intervention. Instead of feeding into the corporate agenda that maximises plastic production, the government could take notes from its surrounding Asian regions.

For example, Taiwan was responsible for a meagre 0.05% of global oceanic plastic waste in 2019, owing to numerous legislation to protect its waters from plastic that the country enforced in recent years, including the Marine Pollution Control Act in 2000 and the Action Plan of Marine Debris Governance in 2018. In 2020, the Environmental Protection Administration declared a ban on all free plastic straws and has now pledged to ban all single-use plastics by 2030. With years of revising and enforcing plans, Taiwan can now aim for bigger environmental goals.

Another great example is China. Up until 2017, the country was the largest importer of plastic . Since the introduction of a ban on imported waste in 2018, including different types of plastics, things have drastically changed. The ban effectively halved the amount of imported waste. Ultimately, China was responsible for only 7.22% of global oceanic plastic pollution in 2019.