Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 31 October 2022

Food insecurity

Nature Climate Change volume 12 , page 963 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

7249 Accesses

3 Citations

25 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Agriculture

- Climate-change impacts

Climate change is a confounding factor that can affect agriculture and food security in many different ways. Climate-resilient food systems are needed to ensure food security and to support mitigation efforts.

World Food Day — 16 October, with the theme this year of ‘leave no one behind’ — is an appropriate time to reflect on global progress toward Sustainable Development Goal 2: Zero Hunger. The 2022 Global Hunger Index, released October 2022 ( https://www.globalhungerindex.org/ ), highlights that progress has stagnated, with the war in Ukraine, climate change and related extreme events, and the related increased price of food, fuel and fertilizer all contributing. The 2022 Global Hunger Index report 1 highlights that 44 countries are currently suffering serious or alarming levels of hunger, although there is large within-country variability. The report estimates that 828 million people are currently undernourished, with parts of Africa south of the Sahara and South Asia having the highest hunger levels, and being the most vulnerable to future shocks.

Climate change can affect crops in different ways and the impacts of climate change due to higher levels of atmospheric CO 2 are often deleterious. While higher levels of atmospheric CO 2 may enhance photosynthesis and growth in some crops 2 , there isn’t a clear picture on the overall effects on crops. Further, it has been reported that plants grown under higher CO 2 levels have changed nutritional value 3 .

Warming temperatures due to climate change also impact crop productivity, with an example discussed in this issue of Nature Climate Change . In an Article , Peng Zhu and colleagues consider how warming temperatures affect cropping frequency and yields. They find that warmer temperatures are increasing productivity and the possibility of multiple cropping seasons in cold regions, but increased temperatures in warm regions are causing decreases that outweigh the cold-region increases for an overall loss in crop productivity. The authors note that irrigation can offset the losses in warm regions, but water availability and the infrastructure needed suggest that the required 5% expansion of irrigation areas would be difficult to achieve.

Research has highlighted the risks of concurrent regional droughts; for example, work looking at 26 main crop-producing countries that found the probability under a high-emissions scenario to be at least 5% compared with 0% in the historical period 4 , as well as work showing increases by 40–60% for 10 global regions, with disproportionate risk increase across North America and the Amazon region 5 . With many regions relying on rain-fed agriculture, drought is a major risk to crop failure.

The shifting of seasons, in particular wet periods, can also affect planting. The northern USA had heavy spring rains this year that limited corn planting. This reduced planting led the US Department of Agriculture to lower the predicted yield per acre by 4 bushels, which equals more than 9 million tonnes less corn crop across the country. This lower yield, alongside lower-than-expected grain harvests in China, India, South America and part of Europe, reduced the available produce, not only for consumption but also for stock feed.

As well as their impact on production, extreme events can be a major disruption of supply chains. Yet, international trade has been highlighted as a possible way to mitigate climate change impacts on food security. It has been shown that high-emissions climate scenarios lead to increased hunger risk of 33–47% when trade is restricted, but decreases to 11–64% when trade is open 6 . However, production for export does need to be carefully considered to minimize negative effects in the producing region 7 .

The need to transform food systems to ensure resilience to climate change and other external pressures is well recognized, yet in climate change discussions it has not always been at the fore; at COP27, there will be a Food Systems Pavilion for the first time. How to achieve food systems transformation needs careful consideration and discussion, but work needs to begin now to push past the current stagnation and to ensure that no one is left behind.

von Grebmer, K. et al. 2022 Global Hunger Index: Food Systems Transformation and Local Governance (Welthungerhilfe, Concern Worldwide, 2022).

Toreti, A. et al. Nat. Food 1 , 775–782 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Dong, J., Gruda, N., Lam, S. K., Li, X. & Duan, Z. Front. Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00924 (2018).

Article Google Scholar

Qi, W., Feng, L., Yang, H. & Liu, J. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49 , e2021GL097060 (2022).

Google Scholar

Singh, J. et al. Nat. Clim. Change 12 , 163–170 (2022).

Janssens, C. et al. Nat. Clim. Change 10 , 829–835 (2020).

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Repurposing Food and Agricultural Policies to Make Healthy Diets More Affordable (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO, 2022); https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0639en

Download references

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Food insecurity. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12 , 963 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01530-2

Download citation

Published : 31 October 2022

Issue Date : November 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01530-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Feeding the future world.

Nature Climate Change (2024)

Interactions between an arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculum and the root-associated microbiome in shaping the response of Capsicum annuum “Locale di Senise” to different irrigation levels

- Alice Calvo

- Thomas Reitz

- Raffaella Balestrini

Plant and Soil (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Anthropocene newsletter — what matters in anthropocene research, free to your inbox weekly.

- Frontiers in Nutrition

- Nutrition and Sustainable Diets

- Research Topics

Food Insecurity

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

In 2015, at least 795 million people worldwide, some 12.9% of world population, lacked enough food to lead a healthy and active life. The majority lived in developing countries in Asia (512 million) and Sub-Saharan Africa (220 million) and these figures are only increasing. Food insecurity (FI) has ...

Keywords : Food systems, nutrition, hunger, right to food, food insecurity

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines.

Submission closed.

Participating Journals

Total views.

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

Food Insecurity

Economic Stability

About This Literature Summary

This summary of the literature on Food Insecurity as a social determinant of health is a narrowly defined examination that is not intended to be exhaustive and may not address all dimensions of the issue. Please note: The terminology used in each summary is consistent with the respective references. For additional information on cross-cutting topics, please see the Access to Foods that Support Healthy Dietary Patterns literature summary.

Related Objectives (4)

Here's a snapshot of the objectives related to topics covered in this literature summary. Browse all objectives .

- Reduce household food insecurity and hunger — NWS‑01

- Eliminate very low food security in children — NWS‑02

- Increase fruit consumption by people aged 2 years and over — NWS‑06

- Increase vegetable consumption by people aged 2 years and older — NWS‑07

Related Evidence-Based Resources (1)

Here's a snapshot of the evidence-based resources related to topics covered in this literature summary. Browse all evidence-based resources .

- The Role of Law and Policy in Achieving the Healthy People 2020 Nutrition and Weight Status Goals of Increased Fruit and Vegetable Intake in the United States

Literature Summary

Food insecurity is defined as a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food. 1 In 2020, 13.8 million households were food insecure at some time during the year. 2 Food insecurity does not necessarily cause hunger, i but hunger is a possible outcome of food insecurity. 3

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) divides food insecurity into the following 2 categories: 1

- Low food security : “Reports of reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet. Little or no indication of reduced food intake.”

- Very low food security : “Reports of multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.”

Food insecurity may be long term or temporary. 4 , 5 , 6 It may be influenced by a number of factors, including income, employment, race/ethnicity, and disability. The risk for food insecurity increases when money to buy food is limited or not available. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 In 2020, 28.6 percent of low-income households were food insecure, compared to the national average of 10.5 percent. 2 Unemployment can also negatively affect a household’s food security status. 10 High unemployment rates among low-income populations make it more difficult to meet basic household food needs. 10 In addition, children with unemployed parents have higher rates of food insecurity than children with employed parents. 12 Disabled adults may be at a higher risk for food insecurity due to limited employment opportunities and health care-related expenses that reduce the income available to buy food. 13 , 14 Racial and ethnic disparities exist related to food insecurity. In 2020, Black non-Hispanic households were over 2 times more likely to be food insecure than the national average (21.7 percent versus 10.5 percent, respectively). Among Hispanic households, the prevalence of food insecurity was 17.2 percent compared to the national average of 10.5 percent. 2 Potential factors influencing these disparities may include neighborhood conditions, physical access to food, and lack of transportation.

Neighborhood conditions may affect physical access to food. 15 For example, people living in some urban areas, rural areas, and low-income neighborhoods may have limited access to full-service supermarkets or grocery stores. 16 Predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods may have fewer full-service supermarkets than predominantly White and non-Hispanic neighborhoods. 17 Convenience stores may have higher food prices, lower-quality foods, and less variety of foods than supermarkets or grocery stores. 16 , 18 Access to healthy foods is also affected by lack of transportation and long distances between residences and supermarkets or grocery stores. 16

Residents are at risk for food insecurity in neighborhoods where transportation options are limited, the travel distance to stores is greater, and there are fewer supermarkets. 16 Lack of access to public transportation or a personal vehicle limits access to food. 16 Groups who may lack transportation to healthy food sources include those with chronic diseases or disabilities, residents of rural areas, and some racial/ethnicity groups. 15 , 16 , 19 A study in Detroit found that people living in low-income, predominantly Black neighborhoods travel an average of 1.1 miles farther to the closest supermarket than people living in low-income predominantly White neighborhoods. 20

Adults who are food insecure may be at an increased risk for a variety of negative health outcomes and health disparities. For example, a study found that food-insecure adults may be at an increased risk for obesity. 21 Another study found higher rates of chronic disease in low-income, food-insecure adults between the ages of 18 years and 65 years. 22 Food-insecure children may also be at an increased risk for a variety of negative health outcomes, including obesity. 23 , 24 , 25 They also face a higher risk of developmental problems compared with food-secure children. 12 , 25 , 26 In addition, reduced frequency, quality, variety, and quantity of consumed foods may have a negative effect on children’s mental health. 27

Food assistance programs, such as the National School Lunch Program (NSLP); the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program; and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), address barriers to accessing healthy food. 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 Studies show these programs may reduce food insecurity. 29 , 30 , 31 More research is needed to understand food insecurity and its influence on health outcomes and disparities. Future studies should consider characteristics of communities and households that influence food insecurity. 32 This additional evidence will facilitate public health efforts to address food insecurity as a social determinant of health.

i The term hunger refers to a potential consequence of food insecurity. Hunger is discomfort, illness, weakness, or pain caused by prolonged, involuntary lack of food.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. (n.d.). Definitions of food security . Retrieved March 10, 2022, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/definitions-of-food-security/

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. (n.d.). Key statistics & graphics. Retrieved March 10, 2022, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/key-statistics-graphics.aspx

Carlson, S. J., Andrews, M. S., & Bickel, G. W. (1999). Measuring food insecurity and hunger in the United States: Development of a national benchmark measure and prevalence estimates. Journal of Nutrition, 129 (2S Suppl), 510S–516S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.2.510S

Jones, A. D., Ngure, F. M., Pelto, G., & Young, S. L. (2013). What are we assessing when we measure food security? A compendium and review of current metrics. Advances in Nutrition, 4(5), 481–505.

Food and Agriculture Organization. (2008). An introduction to the basic concepts of food security . Food Security Information for Action Practical Guides. EC–FAO Food Security Programme.

Nord, M., Andrews, M., & Winicki, J. (2002). Frequency and duration of food insecurity and hunger in U.S. households. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 34 (4), 194–201.

Sharkey, J. R., Johnson, C. M., & Dean, W. R. (2011). Relationship of household food insecurity to health-related quality of life in a large sample of rural and urban women. Women & Health, 51 (5), 442–460.

Seefeldt, K. S., & Castelli, T. (2009). Low-income women’s experiences with food programs, food spending, and food-related hardships (no. 57) . USDA Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=84306

Nord, M., Andrews, M., & Carlson, S. (2007). Measuring food security in the United States: household food security in the United States, 2001. Economic Research Report (29).

Nord, M. (2007). Characteristics of low-income households with very low food security: An analysis of the USDA GPRA food security indicator. USDA-ERS Economic Information Bulletin (25).

Klesges, L. M., Pahor, M., Shorr, R. I., Wan, J. Y., Williamson, J. D., & Guralnik, J. M. (2001). Financial difficulty in acquiring food among elderly disabled women: Results from the Women’s Health and Aging Study. American Journal of Public Health, 91 (1), 68.

Nord, M. (2009). Food insecurity in households with children: Prevalence, severity, and household characteristics. USDA-ERS Economic Information Bulletin (56).

Coleman-Jensen, A., & Nord, M. (2013). Food insecurity among households with working-age adults with disabilities. USDA-ERS Economic Research Report (144).

Huang, J., Guo, B., & Kim, Y. (2010). Food insecurity and disability: Do economic resources matter? Social Science Research, 39 (1), 111–124.

Zenk, S. N., Schulz, A. J., Israel, B. A., James, S. A., Bao, S., & Wilson, M. L. (2005). Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and the spatial accessibility of supermarkets in metropolitan Detroit. American Journal of Public Health, 95 (4), 660–667.

Ploeg, M. V., Breneman, V., Farrigan, T., Hamrick, K., Hopkins, D., Kaufman, P., Lin, B.-H., Nord, M., Smith, T. A., Williams, R., Kinnison, K., Olander, C., Singh, A., & Tuckermanty, E. (n.d.). Access to affordable and nutritious food-measuring and understanding food deserts and their consequences: Report to congress. Retrieved March 10, 2022, from http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=42729

Powell, L. M., Slater, S., Mirtcheva, D., Bao, Y., & Chaloupka, F. J. (2007). Food store availability and neighborhood characteristics in the United States. Preventive Medicine, 44 (3), 189–195.

Crockett, E. G., Clancy, K. L., & Bowering, J. (1992). Comparing the cost of a thrifty food plan market basket in three areas of New York State. Journal of Nutrition Education, 24 (1), 71S–78S.

Seligman, H. K., Laraia, B. A., & Kushel, M. B. (2010). Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. Journal of Nutrition, 140 (2), 304–310.

Zenk, S. N., Schulz, A. J., Israel, B. A., James, S. A., Bao, S., & Wilson, M. L. (2005). Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and the spatial accessibility of supermarkets in metropolitan Detroit. American Journal of Public Health , 95(4), 660–667.

Hernandez, D. C., Reesor, L. M., & Murillo, R. (2017). Food insecurity and adult overweight/obesity: Gender and race/ethnic disparities. Appetite, 117, 373–378.

Gregory, C. A., & Coleman-Jensen, A. (n.d.). Food insecurity, chronic disease, and health among working-age adults . Retrieved March 10, 2022, from http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=84466

Gundersen, C., & Kreider, B. (2009). Bounding the effects of food insecurity on children’s health outcomes. Journal of Health Economics , 28 (5), 971–983.

Metallinos-Katsaras, E., Must, A., & Gorman, K. (2012). A longitudinal study of food insecurity on obesity in preschool children. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 112 (12), 1949–1958.

Cook, J. T., & Frank, D. A. (2008). Food security, poverty, and human development in the United States. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136 (1), 193–209.

Cook, J. T. (2013, April). Impacts of child food insecurity and hunger on health and development in children: Implications of measurement approach. In Paper commissioned for the Workshop on Research Gaps and Opportunities on the Causes and Consequences of Child Hunger.

Burke, M. P., Martini, L. H., Çayır, E., Hartline-Grafton, H. L., & Meade, R. L. (2016). Severity of household food insecurity is positively associated with mental disorders among children and adolescents in the United States. Journal of Nutrition , 146(10), 2019–2026.

Bhattarai, G. R., Duffy, P. A., & Raymond, J. (2005). Use of food pantries and food stamps in low‐income households in the United States. Journal of Consumer Affairs , 39(2), 276–298.

Huang, J., & Barnidge, E. (2016). Low-income children's participation in the National School Lunch Program and household food insufficiency. Social Science & Medicine, 150 , 8–14.

Kreider, B., Pepper, J. V., & Roy, M. (2016). Identifying the effects of WIC on food insecurity among infants and children. Southern Economic Journal, 82 (4), 1106–1122.

Ratcliffe, C., McKernan, S. M., & Zhang, S. (2011). How much does the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program reduce food insecurity? American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 93 (4), 1082–1098.

Larson, N. I., & Story, M. T. (2011). Food insecurity and weight status among U.S. children and families: A review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40 (2), 166–173.

Back to top

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

Food Security Update | World Bank Response to Rising Food Insecurity

- Our Projects

- Data & Research

- News & Opinions

- What is Food Security

Latest Update – July 1, 2024

Domestic food price inflation remains high in many low- and middle-income countries. Inflation higher than 5% is experienced in 59.1% of low-income countries (no change since the last update on May 30, 2024), 63% of lower-middle-income countries (no change), 36% of upper-middle-income countries (5.0 percentage points higher), and 10.9 percent of high-income countries (3.6 percentage points lower). In real terms, food price inflation exceeded overall inflation in 46.7% of the 167 countries where data is available.

Download the latest brief on rising food insecurity and World Bank responses

Since the last update on May 30, 2024, the agricultural, cereal, and export price indices closed 8%, 10%, and 9% lower, respectively. A fall in cocoa (16%) and cotton (11%) prices drove the decrease in the export price index. Maize and wheat prices closed 8% and 23% lower, respectively, and rice closed at the same level. Maize prices are 28% lower, wheat prices 8% higher, and rice prices 18% higher on a year-on-year basis. Maize prices are 10% higher, wheat prices 5% lower, and rice prices 46% higher than in January 2020. (See “ pink sheet” data for agricultural commodity and food commodity prices indices, updated monthly.)

In the latest Hunger Hotspots report covering the period between June and October 2024, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and World Food Programme (WFP) have issued a joint warning about the escalating food insecurity crisis in 18 critical hotspots comprising 17 countries or territories and one regional cluster. Mali, the Palestinian Territories, South Sudan, and Sudan are of the highest concern, and Haiti is newly added because of escalating violence by non-state armed groups. These areas are experiencing famine or are at severe risk, requiring urgent action to prevent catastrophic conditions. The report emphasizes the critical need for expanded humanitarian assistance in all 18 hotspots to protect livelihoods and increase access to food. Early intervention is crucial to mitigate food gaps and prevent further deterioration into famine conditions. The international community is urged to invest in integrated solutions that address the multifaceted causes of food insecurity, ensuring sustainable support beyond emergency responses to build resilience and stability in affected regions.

A new report from the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) confirms that the food insecurity situation in Gaza continues to be catastrophic. High risk of famine will persist across the whole Gaza Strip as long as conflict continues, and humanitarian access is restricted. The report finds that 96% of the population, equivalent to 2.15 million people, face acute food insecurity (IPC Phase 3 or above), with 495,000 individuals experiencing catastrophic levels of food insecurity (IPC Phase 5) through September 2024. The gravity of the situation is a reminder of the urgent need to make sure food and other supplies reach all people in Gaza. Only cessation of hostilities in conjunction with sustained humanitarian access to the entire Gaza Strip can reduce the risk of famine occurring in the Gaza Strip, the report argues.

The AMIS Market Monitor for June 2024 highlights the initial forecasts for global cereal production released in May, underscoring significant uncertainty because planting of many crops is pending in the Northern hemisphere. The report scrutinizes the validity of early projections for 2024/25 wheat production, now challenged by adverse weather conditions such as drought and prolonged frost in key Russian regions that affect yield expectations. Consequently, world wheat export prices rose in May, driven by mounting concerns over production constraints, particularly in the Black Sea region. Given wheat's critical role as a staple food with limited substitutes, importing nations are closely monitoring developments for potential impacts on food security.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, trade-related policies imposed by countries have surged. The global food crisis has been partially made worse by the growing number of food and fertilizer trade restrictions put in place by countries with a goal of increasing domestic supply and reducing prices. As of June 26, 2024, 16 countries have implemented 22 food export bans, and 8 have implemented 15 export-limiting measures.

World Bank Action

Our food and nutrition security portfolio now spans across 90 countries. It includes both short term interventions such as expanding social protection, also longer-term resilience such as boosting productivity and climate-smart agriculture. The Bank's intervention is expected to benefit 296 million people. Some examples include:

- In Honduras, the Rural Competitiveness Project series (COMRURAL II and III) aims to generate entrepreneurship and employment opportunities while promoting a climate-conscious, nutrition-smart strategy in agri-food value chains. To date, the program is benefiting around 6,287 rural small-scale producers (of which 33% are women, 15% youth, and 11% indigenous) of coffee, vegetables, dairy, honey, and other commodities through enhanced market connections and adoption of improved agricultural technologies and has created 6,678 new jobs.

- In Honduras, the Corredor Seco Food Security Project (PROSASUR) strives to enhance food security for impoverished and vulnerable rural households in the country’s Dry Corridor. This project has supported 12,202 extremely vulnerable families through nutrition-smart agricultural subprojects, food security plans, community nutrition plans, and nutrition and hygiene education. Within the beneficiary population, 70% of children under the age of five and their mothers now have a dietary diversity score of at least 4 (i.e., consume at least four food groups).

- The $2.75 billion Food Systems Resilience Program for Eastern and Southern Africa , helps countries in Eastern and Southern Africa increase the resilience of the region’s food systems and ability to tackle growing food insecurity. Now in phase three, the program will enhance inter-agency food crisis response also boost medium- and long-term efforts for resilient agricultural production, sustainable development of natural resources, expanded market access, and a greater focus on food systems resilience in policymaking.

- A $95 million credit from IDA for the Malawi Agriculture Commercialization Project (AGCOM) to increase commercialization of select agriculture value chain products and to provide immediate and effective response to an eligible crisis or emergency.

- The $200 million IDA grant for Madagascar to strengthen decentralized service delivery, upgrade water supply, restore and protect landscapes, and strengthen the resilience of food and livelihood systems in the drought-prone ‘Grand Sud’ .

- A $60 million credit for the Integrated Community Development Project that works with refugees and host communities in four northern provinces of Burundi to improve food and nutrition security, build socio-economic infrastructure, and support micro-enterprise development through a participatory approach.

- The $175 million Sahel Irrigation Initiative Regional Support Project is helping build resilience and boost productivity of agricultural and pastoral activities in Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Senegal. More than 130,000 farmers and members of pastoral communities are benefiting from small and medium-sized irrigation initiatives. The project is building a portfolio of bankable irrigation investment projects of around 68,000 ha, particularly in medium and large-scale irrigation in the Sahel region.

- Through the $50 million Emergency Food Security Response project , 329,000 smallholder farmers in Central Africa Republic have received seeds, farming tools and training in agricultural and post-harvest techniques to boost crop production and become more resilient to climate and conflict risks.

- The $15 million Guinea Bissau Emergency Food Security Project is helping increase agriculture production and access to food to vulnerable families. Over 72,000 farmers have received drought-resistant and high-yielding seeds, fertilizers, agricultural equipment; and livestock vaccines for the country-wide vaccination program. In addition, 8,000 vulnerable households have received cash transfer to purchase food and tackle food insecurity.

- The $60 million Accelerating the Impact of CGIAR Research for Africa (AICCRA) project has reached nearly 3 million African farmers (39% women) with critical climate smart agriculture tools and information services in partnership with the Consortium of International Agricultural Research Centers (CGIAR). These tools and services are helping farmers to increase production and build resilience in the face of climate crisis. In Mali, studies showed that farmers using recommendations from the AICCRA-supported RiceAdvice had on average 0.9 ton per hectare higher yield and US$320 per hectare higher income.

- The $766 million West Africa Food Systems Resilience Program is working to increase preparedness against food insecurity and improve the resilience of food systems in West Africa. The program is increasing digital advisory services for agriculture and food crisis prevention and management, boosting adaption capacity of agriculture system actors, and investing in regional food market integration and trade to increase food security. An additional $345 million is currently under preparation for Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo.

- A $150 million grant for the second phase of the Yemen Food Security Response and Resilience Project, which will help address food insecurity, strengthen resilience and protect livelihoods.

- $50 million grant of additional financing for Tajikistan to mitigate food and nutrition insecurity impacts on households and enhance the overall resilience of the agriculture sector.

- A $125 million project in Jordan aims to strengthen the development the agriculture sector by enhancing its climate resilience, increasing competitiveness and inclusion, and ensuring medium- to long-term food security.

- A $300 million project in Bolivia that will contribute to increasing food security, market access and the adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices.

- A $315 million loan to support Chad, Ghana and Sierra Leone to increase their preparedness against food insecurity and to improve the resilience of their food systems.

- A $500 million Emergency Food Security and Resilience Support Project to bolster Egypt's efforts to ensure that poor and vulnerable households have uninterrupted access to bread, help strengthen the country's resilience to food crises, and support to reforms that will help improve nutritional outcomes.

- A $130 million loan for Tunisia , seeking to lessen the impact of the Ukraine war by financing vital soft wheat imports and providing emergency support to cover barley imports for dairy production and seeds for smallholder farmers for the upcoming planting season.

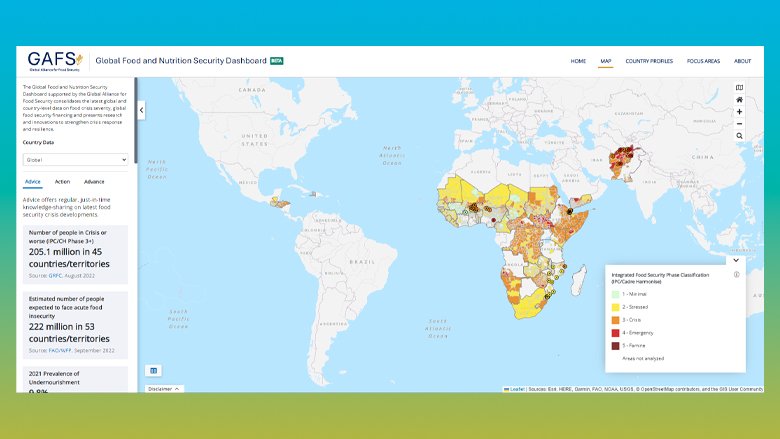

In May 2022, the World Bank Group and the G7 Presidency co-convened the Global Alliance for Food Security , which aims to catalyze an immediate and concerted response to the unfolding global hunger crisis. The Alliance has developed the publicly accessible Global Food and Nutrition Security Dashboard , which provides timely information for global and local decision-makers to help improve coordination of the policy and financial response to the food crisis.

The heads of the FAO, IMF, World Bank Group, WFP, and WTO released a Third Joint Statement on February 8, 2023. The statement calls to prevent a worsening of the food and nutrition security crisis, further urgent actions are required to (i) rescue hunger hotspots, (ii) facilitate trade, improve the functioning of markets, and enhance the role of the private sector, and (iii) reform and repurpose harmful subsidies with careful targeting and efficiency. Countries should balance short-term urgent interventions with longer-term resilience efforts as they respond to the crisis.

Last Updated: Jul 01, 2024

Global Food and Nutrition Security Dashboard

World Bank Scales Up Food and Nutrition Security Crises Response to Benefit 335 ...

Second Update on Food and Nutrition Security (FNS)

Coming Together to Address the Global Food Crisis

World Bank Announces Planned Actions for Global Food Crisis Response

Second Joint Statement by the Heads of FAO, IMF, WBG, WFP, and WTO on the Global ...

Interviews with food security experts, the impact of the war in ukraine on food security | world bank expert answers, stay connected.

- Nicolas Douillet Washington, D.C. [email protected]

- Nugroho Nurdikiawan Sunjoyo Washington, D.C. [email protected]

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

- Alzheimer's disease & dementia

- Arthritis & Rheumatism

- Attention deficit disorders

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Biomedical technology

- Diseases, Conditions, Syndromes

- Endocrinology & Metabolism

- Gastroenterology

- Gerontology & Geriatrics

- Health informatics

- Inflammatory disorders

- Medical economics

- Medical research

- Medications

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics & gynaecology

- Oncology & Cancer

- Ophthalmology

- Overweight & Obesity

- Parkinson's & Movement disorders

- Psychology & Psychiatry

- Radiology & Imaging

- Sleep disorders

- Sports medicine & Kinesiology

- Vaccination

- Breast cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Kidney disease

- Lung cancer

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Ovarian cancer

- Post traumatic stress disorder

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Schizophrenia

- Skin cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Full List »

share this!

August 12, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

Smart food choices at family level can ease chronic illness

by Krisy Gashler, Cornell University

Promoting healthy diets for the entire family can better improve health outcomes for people with chronic illnesses, according to a new Cornell study.

"Families are an essential social unit, and food is a social medium: families pool and negotiate food choices, and it's also the way we pass on dietary preferences, traditions and build kinship," said Ramya Ambikapthi, senior research associate in the Food Systems & Global Change program in the Department of Global Development, in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

"If you can change food behaviors at the family level, you have the opportunity to achieve healthier diets for all, now and for the next generation."

Ambikapthi is the co-first author of the paper, published Aug. 7 in Global Food Security and co-written with colleagues from Purdue University, University of South Carolina, Harvard University, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences in Tanzania, Tanzania Food and Nutrition Center, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and the University of Illinois.

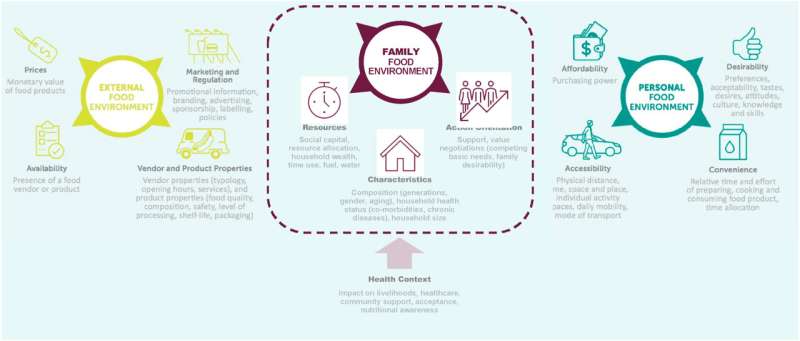

Research and policy on nutrition support have historically focused on external factors, such as market prices and availability, and individual factors, including affordability and physical distance from food resources . In the last few years, researchers have begun emphasizing the importance of family food dynamics as both a factor influencing individual food choices and as a policy lever to improve healthy, sustainable diets for all, Ambikapthi said.

In the current study, researchers used HIV as a case study to understand family food dynamics, reviewing almost 7,000 relevant articles. Then they developed a Family Dynamics Food Environment Framework (FDF), which they hope will inform research and policy on an array of chronic illnesses , especially as diet-related illnesses such as diabetes and heart disease grow across the globe.

Because of improvements in disease management, HIV has become a chronic illness that many people can live with for decades; however, such a diagnosis can have devastating economic impacts for individuals and families, especially those already living in poverty in the Global South. HIV-positive individuals may lack energy to perform farm labor or be denied employment because of social stigma.

"If your family supports you, that determines how well you survive, and food is an important part of family support," Ambikapthi said. Food security is particularly important for HIV patients prescribed antiretroviral therapy (ART) drugs, which require a full meal to be absorbed. "When people who have HIV and are food insecure are told to take ART, they don't take it, because if they don't have enough food, ART just makes them throw up."

In low-income households, families also have to cope with the constant pressure of competing basic needs , such as allocating scarce resources to fuel or schooling, or choosing which family members will receive sufficient nutritious food: children, elderly family members, those performing the most manual labor or individuals with HIV.

"Nutrition programs generally focus on pregnant women and small children, due to their critical nutrition needs. But what we want is healthy diets for all," Ambikapthi said. "Understanding how family dynamics impact food choices can help people who implement nutrition policies to structure intervention messages in ways that enable healthy diets for the entire family."

The researchers plan for future work on this topic to explore how family food dynamics can be applied in other contexts; for example, achieving sustainable, healthy diets in urban areas.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Pre-surgical antibody treatment might prevent heart transplant rejection

Researchers enhance natural killer cells to target pediatric brain cancer

Study reveals OLAH enzyme underpins lethal respiratory viral disease

2 hours ago

MRI technique accurately predicts heart failure risk in general population

3 hours ago

Harnessing deep learning, new research suggests phased COVID-19 vaccine rollout was a mixed bag for mental health

New findings suggest alternative mechanisms behind Alzheimer's disease

Hooked on a feeling: Opioids evoke positive feelings through a newly identified brain region

Comprehensive atlas of normal breast cells offers new tool for understanding breast cancer origin

Parents who use humor have better relationships with their children, study finds

Researchers urge Medicare coverage of driving assessments for at-risk, older adults

4 hours ago

Related Stories

Moms and caregivers facing family food insecurity need help with more than just food, researchers say

Jul 24, 2024

Examining existing gaps in food insecurity research

LA County faces a dual challenge: Food insecurity and nutrition insecurity

Jul 9, 2024

Better food policies needed to combat obesity and overnutrition in South Asia, says study

Jul 11, 2024

One in eight military families with children use a food bank to make ends meet, finds study

Nov 7, 2023

Household food waste reduced through whole-family food literacy intervention

Feb 6, 2024

Recommended for you

Study suggests heat caused over 47,000 deaths in Europe in 2023, the second highest burden of the last decade

5 hours ago

Getting fats from plants vs. animals boosts your life span: Study

Pathways linking body and brain health and impacts to mental health revealed

Aug 9, 2024

Vegan diet better than Mediterranean, finds new research

Study finds baked potatoes can improve heart health for diabetics

'PTNM' system provides new classification for Peyronie's disease and penile curvature

Let us know if there is a problem with our content.

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Medical Xpress in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Special Issues

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self Archiving Policy

- Why publish with this journal?

- About Translational Behavioral Medicine

- About Society of Behavioral Medicine

- Journal Staff

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, acknowledgements, compliant with ethical standards.

- < Previous

Food insecurity and obesity: research gaps, opportunities, and challenges

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Alison G M Brown, Layla E Esposito, Rachel A Fisher, Holly L Nicastro, Derrick C Tabor, Jenelle R Walker, Food insecurity and obesity: research gaps, opportunities, and challenges, Translational Behavioral Medicine , Volume 9, Issue 5, October 2019, Pages 980–987, https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibz117

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Food insecurity, defined as a lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life, is a major public health concern with 11.8% of U.S. households (15.0 million) estimated to be affected at some point in 2017 according to the United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. While the link between food insecurity, diet quality, and obesity is well documented in the literature, additional research and policy considerations are needed to better understand underlying mechanisms, associated risks, and effective strategies to mitigate the adverse impact of obesity related food insecurity on health. With its Strategic Plan for NIH Obesity Research, the NIH has invested in a broad spectrum of obesity research over the past 10 years to understand the multifaceted factors that contribute to the disease. The issue of food insecurity, obesity and nutrition is cross-cutting and relates to many activities and research priorities of the institutes and centers within the NIH. Several research gaps exist, including the mechanisms and pathways that underscore the complex relationship between food insecurity, diet, and weight outcomes, the impacts on pregnant and lactating women, children, and other vulnerable populations, its cumulative impact over the life course, and the development of effective multi-level intervention strategies to address this critical social determinant of health. Challenges and barriers such as the episodic nature of food insecurity and the inconsistencies of how food insecurity is measured in different studies also remain. Overall, food insecurity research aligns with the upcoming release of the Strategic Plan for NIH Nutrition Research and will continue to be prioritized in order to enhance health, lengthen life, reduce illness and disability and health disparities.

Practice : This research can provide evidence of effective programs or strategies to reduce food insecurity or obesity related to food insecurity that can be integrated into practices in the real-world setting.

Policy : Food insecurity and obesity are serious public health challenges and research related to programs, policies, and/or environmental strategies could be considered to reduce risk factors associated with food insecurity patterns and promote sustainable approaches for healthy food access, especially among the most vulnerable.

Research : To address gaps in food insecurity and obesity research, the National Institutes of Health supports a broad-spectrum of biomedical and behavioral research that seeks to identify underlying mechanisms, associated risks, and effective strategies to mitigate this public health concern.

Food insecurity—a lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life—is a significant global and domestic public health concern. An estimated 11.8 per cent of American households were food insecure at some point during 2017 [ 1 ]. About 4.5 per cent of households had very low food security , a more severe range of food insecurity in which the food intake of some household members was reduced, and normal eating patterns were disrupted at times during the year due to limited resources. Overall, rates of food insecurity were higher than the national average in low-income households, Black- and Hispanic-headed households, and households with children [ 1 ].

A negative association between food insecurity and health has been consistently demonstrated in the literature [ 2 ]. Among children and adolescents, food insecurity has been associated with a variety of outcomes such as asthma [ 3 ], anemia [ 4 ], and behavioral, academic, and emotional problems [ 5 ]. Among adults, studies have shown that food insecurity is associated with poor dietary quality [ 6 ], depression [ 7 ], cardiometabolic diseases [ 8 ], diabetes and poor diabetes control [ 9 ] and obesity, particularly among adult women [ 8 , 10 , 11 ]. The question of whether food insecurity causes obesity was first published in 1995 [ 12 ]. Since then, the body of evidence exploring this relationship has grown substantially. Despite several hypotheses that have been proposed in the literature to explain the link between food insecurity and body weight, it is not well understood if food insecurity plays a causative role in the development of obesity, and if it does, what mechanisms are involved [ 10 ].

Food insecurity, nutrition, and obesity are cross-cutting scientific topics that are within the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-supported research, however, are often not examined in tandem within individual studies. This research is facilitated across several Institutes and Centers to progress toward reducing chronic diseases; understanding genetic, behavioral, and environmental causes; and studying impacts of innovative prevention and treatment strategies designed to address them. The NIH and other funding agencies have made investments in this area of research; however, additional studies are needed to better understand underlying mechanisms, associated risks, and effective strategies to mitigate these public health concerns. Furthermore, the NIH has the opportunity and ability to promote translational research and implementation science to adequately address issues of food security and obesity within the U.S. population.

The purpose of this commentary was to consider the challenges, gaps, and opportunities in the research exploring the link between food insecurity and obesity. In this commentary, we:

Describe the food insecurity and obesity research within the various NIH Institutes and Centers;

Identify key fundamental challenges with how food insecurity is defined;

Explain research gaps ranging from the need for more research and potential strategies to explore the continuum of research from the mechanisms and pathways of the relationship to more longitudinal and multilevel intervention research; and

Highlight research opportunities through existing funding mechanisms and epidemiological cohort studies and future research stemming from the Strategic Plan for NIH Nutrition Research.

NIH-wide investments

With its Strategic Plan for NIH Obesity Research, the NIH has invested in a broad-spectrum of obesity research over the past 10 years to understand the multifaceted factors that contribute to the disease [ 13 ]). The issues of food insecurity, obesity, and nutrition are cross-cutting and relate to many funded research studies throughout the Institutes and Centers within the NIH. There is also a specific focus within the NIH to promote implementation science and study the methods and strategies that enhance the uptake of effective interventions into routine practice with the aim of improving population health [ 14 ]. From fiscal years (FY) 2009–2017, the most recent year for which complete data were available, the NIH funded 30 grants, related to food insecurity and obesity (NIH RePORTER tool, search terms “food insecurity” or “food desert” + RCDC code = “obesity”, fiscal years 2009-2017, awarded grants only). The NIH spent $31.6 million from FY09 to FY17 on these grants. Eight (27 per cent) of these grants were funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Other major funders included the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (five grants, 17 per cent), the National Cancer Institute (four grants, 13 per cent), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (three grants, 10 per cent), and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (three grants, 10 per cent). The majority (22; 73 per cent) of these grants were research project grants, whereas 3 (10 per cent) used training mechanisms, and the remainder were intramural or other.

Prominent thematic and topical areas covered by the most recent grants, identified using the NIH iSearch tool, include maternal stress, food stamps, pediatric obesity, and corner or convenience stores. Studies ranged from secondary data analysis of existing datasets to community-based interventions to change individual-level dietary behaviors and food insecurity outcomes. For example, one study explored the influence of stress on household food insecurity and dysregulated eating behaviors on weight among women postpartum [ 15 ]. Formative research from a community-based participatory research study, Tribal Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environment Study, assessed for correlates of food insecurity within an Oklahoma tribal community to inform development of a community-based intervention within convenience stores to increase the availability of fruit and vegetables [ 16 ]. This research included practical applications to expand the impact of the research. For example, the partnerships formed as a result of the study informed policies used to address the issue of food insecurity, including the development of a community supported agriculture and community food program, increased access to culturally appropriate produce at local farmers' markets, restructuring the placement of healthy foods in local grocery stores, and the introduction of Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT; the method for which Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the largest federal food assistance program, is redeemed) [ 16 ] ( Fig. 1 ).

The National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded grants on food insecurity and obesity, 2009–2017, by the NIH Institute/Center. “Other” category includes National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, National Institute on Aging, and National Institute of Nursing Research. Each Institute/Center in the “Other” category funded one grant. Abbreviations: NICHD, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIDDK, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; NCI, National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Mental Health; NHLBI, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NIMHD, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; NIMH, National Institute of Mental Health.

Research challenges and barriers

Despite investments by the NIH and others in this area, key challenges and barriers remain, particularly on the accuracy of measurement, definitions, and operationalization of the food security measure. Although there is variation in how food security is assessed across the literature, most studies in U.S. population use instruments that are based on the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food Security Supplement, which is administered annually in conjunction with the Census Bureau's nationally representative Current Population Survey. The Food Security Supplement includes a series of 18 questions (10 questions if no children are included in the household) that ask respondents about their experiences over the past 12 months related to concerns that food would run out, perceptions about the quantity and quality of the meals they could afford, and whether any adults or children had to forgo food due to a lack of resources. A validated 6-item “short form” has also been created by the USDA for surveys that cannot implement the 18-item or 10-item questionnaire [ 17 ]. Instruments used in the literature range from a single question to all 18 items [ 8 ]. In addition to the instrument developed by the USDA, a review by Ashby et al. [ 18 ] identified eight other multi-item tools that were used to assess food security in developed countries. These tools were shown to have moderate-to-high internal consistency but varying levels of validity among the subpopulations at risk for food insecurity [ 18 ].

The severity and duration of exposure to food insecurity can be difficult to quantify. This is due in part to the heterogeneous circumstances of food-insecure individuals and a range of situations that can fluctuate throughout the year causing many households to cycle in and out of food insecurity [ 8 , 19 ]. Categories of food insecurity include marginal food security, low food security, and very low food security; however, current measurement tools do not distinguish between acute and chronic food insecurity and may not adequately capture information in vulnerable subgroups (i.e., among non-English speakers) or the nuance of the experience of food insecurity among different cultures, for example, among immigrant populations [ 20 , 21 ]. In addition, the USDA metric of food insecurity primarily focuses on the economic definition of food insecurity and does not capture behavioral coping patterns such as the trade-offs between food purchases and other expenses [ 22 ]. There are few longitudinal surveys that assess food insecurity at multiple time points or over the life course. These limitations create a challenge when evaluating the relationship between food insecurity and health outcomes, such as obesity.

Another research challenge comes from the fact that many studies measure food insecurity at the household level, which may not accurately reflect the degree of food insecurity experienced by any one individual. Studies in the international context suggest differences in intra-household food allocation based on gender and age [ 23 ]. For example, children in a food-insecure household may be shielded from the impact of a food shortage by their parents, and thus, will not be affected by food insecurity to the same extent as an adult living in the same household [ 24 ]. Even among food-insecure adults, there may be a large variation in the severity of the food insecurity that they experience. This variation is difficult to capture and may explain some of the mixed results in the literature.

Research gaps

To explore the state of the research in this area and identify predominate research gaps, we examined the existing literature and systematic reviews on the topic. Four main research gap areas emerged ( Table 1 ) including: (a) the mechanisms and pathways underlying the relationship between food insecurity and obesity; (b) the impact of food insecurity on pregnant and lactating women, children, and other vulnerable populations; (c) longitudinal studies; and (d) effective multilevel intervention strategies that could be used for greater real-world impact.

Research gaps and direction for future research

| Topic . | Research gaps and opportunities . |

|---|---|

| 1. Mechanisms and pathways | • Underlying mechanisms and pathways that explain the relationship between food insecurity and obesity and contradictory findings in the literature based on demographic groups • Research drawing from the intersection of evolutionary biology, ecology, and obesity literature |

| 2. Impact on pregnant and lactating women, children, and other vulnerable populations | • Short- and long-term impact of food insecurity on weight outcomes among pregnant and lactating women, infants, children, and adolescents • Impact of food insecurity and dietary patterns on the onset and progression of chronic diseases such as obesity and diabetes • Influence of food insecurity across the life course and critical periods of development • Influence of food insecurity on racial/ethnic and rural/urban health disparities |

| 3. Longitudinal studies | • Well-designed longitudinal studies to support the temporality criteria for Bradford Hill's criteria for causality and explore pathways, mechanisms, and dietary patterns underlying this relationship |

| 4. Effective multilevel intervention strategies | • Strategies that integrate several aspects of the socioecological model for change (individual, organizational community, policy, etc.) • Interventions that target federal food and nutrition programs (i.e., SNAP and WIC) and their recipients • Natural experiment studies that leverage federal and local policy changes that influence food insecurity • Interventions that use electronic and other innovative technologies |

| Topic . | Research gaps and opportunities . |

|---|---|

| 1. Mechanisms and pathways | • Underlying mechanisms and pathways that explain the relationship between food insecurity and obesity and contradictory findings in the literature based on demographic groups • Research drawing from the intersection of evolutionary biology, ecology, and obesity literature |

| 2. Impact on pregnant and lactating women, children, and other vulnerable populations | • Short- and long-term impact of food insecurity on weight outcomes among pregnant and lactating women, infants, children, and adolescents • Impact of food insecurity and dietary patterns on the onset and progression of chronic diseases such as obesity and diabetes • Influence of food insecurity across the life course and critical periods of development • Influence of food insecurity on racial/ethnic and rural/urban health disparities |

| 3. Longitudinal studies | • Well-designed longitudinal studies to support the temporality criteria for Bradford Hill's criteria for causality and explore pathways, mechanisms, and dietary patterns underlying this relationship |

| 4. Effective multilevel intervention strategies | • Strategies that integrate several aspects of the socioecological model for change (individual, organizational community, policy, etc.) • Interventions that target federal food and nutrition programs (i.e., SNAP and WIC) and their recipients • Natural experiment studies that leverage federal and local policy changes that influence food insecurity • Interventions that use electronic and other innovative technologies |

Mechanisms and pathways

Although the link between obesity, food insecurity, and diet has been examined, the research literature shows conflicting results depending on the subpopulation and dataset used [ 11 , 25 , 26 ]. The varying effects and contradictory findings that differ by gender, race, ethnicity, and age group warrant further exploration. Future research should also explain the underlying mechanisms and pathways underscoring this relationship and contradictory findings.

Previous research has posited that food insecurity contributes to irregular eating patterns characterized by periods of underconsumption and food deprivation when resources are limited, and compensatory overconsumption when resources are adequate, contributing to adiposity [ 27–29 . Coupled with this cycle is the widespread availability of high calorie, low-cost foods consumed by those experiencing food insecurity. Theoretical models have proposed a mechanistic explanation drawing in findings from the intersection of evolutionary biology, ecology, and obesity research [ 10 , 30 ]. Yet, the driving mechanisms remain unclear.

Impact on pregnant and lactating women, children, and other populations

Given the critical role nutrition plays in fetal and childhood development, additional research exploring the long-term impact of food insecurity on pregnant and lactating women, and during infancy, toddlerhood, and adolescence are still needed [ 8 , 31 ]. Understanding the influence of food insecurity patterns on the onset and progression of chronic diseases such as obesity and diabetes and its influence across the life course and critical periods of development are of particular interest. Existing studies show food insecurity in pregnancy and postpartum to be associated with disordered eating, variations in gestational weight gain depending on prepregnancy weight [ 15 , 32 ], and decreased duration of breastfeeding [ 32 ]. In addition, as previously stated, most of the literature measures food insecurity at the household level and extrapolates these data to represent the childhood experience, meanwhile children may be protected from the influence of food insecurity due to intra-household food allocation strategies (i.e., a mother feeding her children before herself to shield her children from food insecurity) [ 8 , 23 ].

Examining the consequences of food insecurity at different stages of child and adolescent development is also important. For instance, one study found that infants and toddlers from low-income households that had food insecurity were at significantly greater developmental risk (in areas such as language, motor, and socio-emotional development) than those from low-income households without food insecurity [ 33 ]. Another study showed that in a large sample of U.S. adolescents, food insecurity was associated with greater risk of mental disorders, after controlling for other socioeconomic (SES)-related variables, such as extreme poverty [ 34 ]. Understanding how food insecurity affects development across the lifespan is key to informing both interventions and policy approaches for particular segments of the population.

Additional research among other diverse and vulnerable populations is also a priority to ensure that the knowledge and evidence base and results are relevant, reliable, and valid in these populations. Food insecurity, for example, affects a greater proportion of racial/ethnic minority and socially disadvantaged groups in the USA that are already at increased risk for diseases related to diet such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes. Typically, such populations are underrepresented in research studies and are considered hard to reach due to a lack of responsiveness to interventions that are designed for general audiences within dissemination and implementation research [ 35 ]. However, there are broader levels of influence to be understood such as the role of inadequate outreach and engagement, insufficient capacity or infrastructure within these communities, use of culturally unacceptable research methods, and in some populations, low participation due to various issues, including historical mistrust [ 35 , 36 ]. Examining food insecurity in rural and urban settings and coping strategies people use to mitigate consequences of food-related hardship in each context is also important and will assist in unraveling these complex associations [ 37 , 38 ]. Improving our understanding of food insecurity among diverse population groups will ultimately help to design interventions and pragmatic approaches to address these known health disparities. By expanding knowledge related to the specific barriers, moderators, and mediating pathways of each group, successful interventions can be better designed and implemented through targeted screening and referral programs or the establishment of new food distribution programs or innovative partnerships.

Longitudinal studies

Because of the complexity of the relationship between food insecurity, diet, and obesity, additional cross-sectional analyses are limited in their ability to answer key research questions. For example, cross-sectional studies cannot establish directionality of associations between food insecurity and obesity. In addition, researchers can statistically control for a variety of sociodemographic factors such as income, education, and race to consider the influence of these factors on both weight and food insecurity, but other unmeasured variables related to food insecurity (i.e., timing, duration, and coping strategies) cannot be accounted for in cross-sectional studies. Although longitudinal studies present similar concerns of unmeasured confounders, the time sequence of events can be clarified with this approach. To the best of our knowledge, there are very few longitudinal studies that explore this area [ 39 , 40 ].

More innovative longitudinal evidence is thus a priority. These studies would elucidate the issue of timing and temporality and support an important criterion for causality as well as shed light on the long-term effect of food insecurity on diet and weight status. In addition, well-designed longitudinal studies would allow for the exploration of the pathways and mechanisms underlying this relationship, which is also critical. Although causality cannot be confirmed given the limitations of longitudinal studies, the inability to conduct conventional randomized control trials to examine this issue should also be acknowledged [ 41 ]. Instead, comparative effectiveness studies offer another alternative to explore these associations.

Development of effective multilevel intervention strategies

Given the systems and social factors that contribute and perpetuate food insecurity and the complexity of the issue, the development of innovative multilevel interventions strategies to address obesity among those experiencing food insecurity is an additional priority. Existing interventions mainly focus on low-income families participating in federal food and nutrition programs (i.e., Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) and have targeted individual-level behaviors, such as diet and physical activity [ 42–44 ]. A more policy-focused initiative includes the USDA-funded Healthy Incentives Pilot, which evaluated the short-term impact of financial incentives to purchase fruit, vegetables, or other healthful foods on the diet quality of SNAP participants [ 45 ]. Because of the pilot nature of the study, the long-term impacts on weight outcomes were not explored. However, this pilot program and other USDA-funded incentive programs have led to permanent funding in the 2018 Farm Bill in what is called the Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program, providing opportunity for future research and evaluation [ 46 ]). Meanwhile, relatively few intervention studies have considered the influence of the various elements of food and nutrition programs (i.e., amount and timing of EBT benefit, and length of time on benefits) on reducing the risk of obesity in their design. Meanwhile, research suggests that these factors may have implications in the link between food insecurity and food programs and obesity [ 47 , 48 ], and therefore should be examined further.

Novel methods that leverage natural experiments or evaluation of the influence of large-scale programs and policies on food access (i.e., policy changes resulting in reductions in EBT benefits) and health outcomes should be explored. It is also important to examine how food environments affect food insecurity and improve the ability to collect more granular geographic data to quantify better local or small area variation of food environments and accessibility to healthy, affordable food resources. These data could improve research efforts related to various disease outcomes and help identify contextual features that may facilitate or hinder successful implementation of intervention strategies. For example, the differential impacts of interventions in rural and urban environments are of interest. In addition, leveraging of electronic and other technologies to address issues of food insecurity are also opportunities for future research growth.

Research opportunities

Current funding opportunity announcements.

Recognizing the need for more research to explore the link between obesity and food insecurity and effectively address these concerns, the NIH is currently seeking innovative applications to address these research gaps. In addition to supporting investigator-initiated grant applications through parent funding opportunity announcements (FOAs), the NIH solicits potential projects related to food insecurity and obesity through three targeted funding opportunity announcements. PAR-18-854, “Time-Sensitive Obesity Policy and Program Evaluation (R01 Clinical Trial Not Allowed)” supports research to evaluate programs and policies that target obesity-related behaviors and/or weight outcomes in an effort to prevent or reduce obesity. It also uses an expedited review and award process to support time-sensitive evaluation of programs or policies with imminent implementation. PA-18-032, “Understanding Factors in Infancy and Early Childhood (Birth to 24 months) That Influence Obesity Development (R01 Clinical Trial Optional)” seeks applications that propose research to identify or characterize factors from birth to 24 months that affect obesity risk in children, a key demographic vulnerable to the effects of food insecurity.

Current and former cohorts available for analysis

A few large current and former NIH studies have included the assessment of household-level food insecurity among study participants, which provides the potential for future research studies on the topic. For example, launched in 2015, the Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes Program is a 7-year initiative to understand the effects of environmental exposures on children's health [ 49 ]. Through the synergistic study of multiple extant longitudinal cohorts, researchers are collecting food insecurity measures, as well as data on physical, chemical, biological, social, behavioral, natural, and built environments on child health outcomes, such as obesity [ 49 ]. The Healthy Communities Study, conducted between 2010 and 2016, is another NIH-funded study that collected dietary data and a food insecurity measure [ 50 ]. The goal of the study included the examination of community characteristics and how these relate to children's dietary and physical activity behaviors, and health outcomes, particularly childhood obesity. The diverse cohort represented 130 communities and over 5,000 children and their families in the USA [ 50 ]. Ultimately, these cohorts include measures that would support the development of research to strengthen our understanding of the impact of food insecurity on the weight status of children over time.

The Strategic Plan for NIH Nutrition Research

The upcoming release of the Strategic Plan for NIH Nutrition Research will continue to prioritize research to expand our understanding of the link between food insecurity and obesity. In October 2016, Dr. Francis Collins, the Director of NIH, established an NIH Nutrition Research Task Force to coordinate and accelerate progress in the NIH-funded nutrition research and to guide the development of the first NIH-wide Strategic Plan for Nutrition Research. Through a collaborative process of gathering information across the various Institutes, Offices, and Centers within the NIH and from the external nutrition research community, literature searches, and public crowdsourcing opportunities, the NIH identified research gaps and areas of opportunity to prioritize the future of nutrition research. The culmination of these efforts is the Strategic Plan for NIH Nutrition Research , which will serve as a guide to accelerate basic, translational, and clinical research, as well as research training activities, over the next 10 years. The Plan is organized by seven themes that each contain major research priorities and examples of related research activities. Equally important to the identification of evidence-based nutrition strategies to improve health is the translation of this research into practice so that health-care providers, patients, families, caregivers, and communities are equipped with tools to adapt and sustain successful nutrition practices. Therefore, the Plan specifically prioritizes efforts to expand implementation science (i.e., the study of methods to promote the adoption and integration of evidence-based practices, interventions, and policies into routine health care and public health settings to improve the impact on population health).

A need for further research related to the direct and indirect consequences of food insecurity and how these consequences alter nutrition and health relationships is highlighted in the Strategic Plan. How food insecurity and other social determinants of health and environmental factors contribute individually and in combination to interindividual variability in the relationships between diet and health requires further elucidation. In addition, research areas aimed at determining the mechanisms underlying the co-existence of food insecurity, obesity, and other related metabolic conditions are described.

The Strategic Plan also calls for increased efforts in systems science and advancement in bioinformatics and computational approaches in nutrition research. As these approaches continue to advance, new opportunities to evaluate the systemic factors and relationships that affect and are affected by nutrition are emerging and may offer opportunities to expand research capabilities. Such approaches may help to untangle the pathways and mechanisms associated with the complex relationships between food insecurity, diet, and weight status or other health outcomes that are difficult to investigate. Insights provided by this research may provide new opportunities for interventions to address food insecurity and related health consequences.

Translational implications

Beyond the topics identified as challenges and gaps for food insecurity and obesity in this article, there is the importance of putting research into practice to positively affect the 11.8 per cent of American households who face food insecurity every year in the USA. As mentioned, implementation science plays an important role in identifying barriers to, and enablers of, effective health programming and policymaking, and leveraging that knowledge to develop evidence-based innovations in effective delivery approaches. It is important for researchers to go beyond studying outcomes for effectiveness and begin systematically targeting implementation outcomes as well. This would include outcomes such as acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, cost, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, and sustainability that are key in the effective translation of evidence-based outcomes into any population [ 51 ].