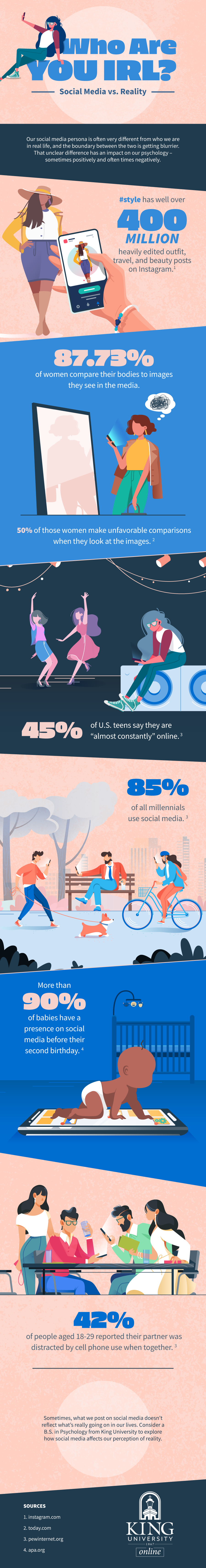

Social Media vs. Reality

Embed this Image On Your Site

Infographic transcript.

Our social media persona is often very different from who we are in real life, and the boundary between the two is getting blurrier. That unclear difference has an impact on our psychology – sometimes positively and often times negatively.

Personal appearance

- #style has well over 400 million heavily edited outfit, travel, and beauty posts on Instagram. [1]

- 73% of women compare their bodies to images they see in the media.

- 50% of those women make unfavorable comparisons when they look at the images. [2]

Social setting with friends

- 45% of U.S. teens say they are “almost constantly” online. [3]

At a concert

- 85% of all millennials use social media. [3]

Being a parent

- More than 90% of babies have a presence on social media before their second birthday. [4]

Marriage / relationships

- 42% of people aged 18-29 reported their partner was distracted by cell phone use when together. [3]

Sometimes, what we post on social media doesn’t reflect what’s really going on in our lives. Consider a B.S. in Psychology from King University to explore how social media affects our perception of reality.

Interested in learning more about social media psychology? Check out King University’s online B.S. in Psychology to start understanding the effects, benefits, and drawbacks of social media. Our flexible program is designed to work around your schedule, and you can earn your degree in as few as 16 months.

- instagram.com

- pewinternet.org

SOCIAL MEDIA VS. REAL LIFE

alum.p.ramos.1

Created on January 25, 2021

More creations to inspire you

History of the earth.

Presentation

3 TIPS FOR AN INTERACTIVE PRESENTATION

49ers gold rush presentation, international events, the eukaryotic cell with review, intro innovate, fall zine 2018.

Discover more incredible creations here

Social media vs. Real life

Social networks are structures formed on the Internet by people or organizations that connect based on common interest or values. Through them, relantionships between individuals or companies are created quickly, without hierarchy or physical limits

What is a social networking site?

Social networks, in the virtual world, are sites and applications that operate at different levels - such as professional, relationship, among others , bur always allowing the exchange of information between people and/or companies

- SOCIAL NETWORK OF RELATIONSHIPS

- ENTERTAINMENT SOCIAL NETWORK

- PROFESSIONAL SOCIAL NETWORK

- NICHE SOCIAL NETWORK

Yoy may think that social networks are all the same, but they are not. In fact, they are usually divides into different types, according to the purpose of the users when creating a profile. And the same social network can be of more than one type.

List the social networking site you know and explain their general rules and the permissions on these apps

- Do not accept friend requests from people we do not know

- Check all our contacts

CHOOSE OUR FRIENDS CAREFULLY:

PAY ATTENTION WHEN WE PUBLISH AND UPLOAD MATERIAL:

- Think carefully about what images, videos and information we choose to publish

- Never post private information

- Use a pseudonym

Golden rules:

- Be careful what we post about other people

Protect our mobile phone and the information stored on it:

- When registering on a social network, use our personal email address.

- Do not mix our work contacts with our friends

- Do not let anyone see our profile or our personal information without permission

- Do not leave our mobile phone unattended

- Do not save our password on our mobile

Protect our work environment and not jeopardize our reputation

- Deactivate services based on geographic location when we are not using them

Pay attention to location-based services and information

- Use privacy-oriented options

- Report immediately if your mobile phone is stolen

- Be careful when using the mobile phone and pay attention to where we leave it

Protect us with privacy settings:

- Read carefully and from beginning to end the privacy policy and the conditions and terms of use of the social network that we choose

THE TOP SOCIAL MEDIA APPS

PERMISSIONS are the set of actions that we allow an application to do with our device and the information it contacins

the top 10 social media apps...FACEBOOK: This is the most versatile and complete social network. A place to generate business, meet people, interact with friends, LEARN, have fun, discuss, among other things INSTAGRAM: Instagram was one of the first exclusive social networks for mobile access. It is a social network for sharing photos and videos between users, with the possibility oF applying filtersWEIBO:many celebrities use this to advertise themselves, to run campaigns with agencies and stay connected with their followers.

WHATSAPP. Whatsapp is the most popular instant messaging social network. Virtually the entire population that has a smartphone also has WhastsApp installed.

TWITTER. Twitter is primarily used as a second screen, where users comment and discuss what they are watching on television, posting comments on news, reality whows, soccer games and other programs.

MESSENGER: Messenger is Facebook's instant messaging social network.

PINTEREST: Pinterest is a social net work of photos that brigns the concept of "wall of references". There it is possible to create folders to save your inspirations and upload images, as well as place links to external URLs.

YOUTUBE: Youtube is the main online video social network today

TIKTOK: It a social network for creating and sharing short videos.QQ: It has email, a bloggining platforma, online shopping, games and even a dating tool.QZone: It is a platform thar allows its users to write blogs anda have a personal journal. You also have an option to send photos, listen to music and watch videos.Snapchat: sNAPCHAT IS A PHOTO, VIDEO AND TEST SHARING APPLICATION FOR MOBILE DEVICES.

- SELECTIVE EXHIBITIONISM

- EXCESS OF VANITY

- FRAGILY OF OUR PRIVACY

- UNCONTESTAD RUMORS

- WASTE OF TIME

- TOO MUCH PUBLICITY?

- ERRORS THAT CAN BE EXPENSIVE

- SPEED OF INFORMATION

- KNOWLEDGE OF PROFILES OF INTEREST

- EASE OF RESUMING CONTACT

- ACCESS TO ALL KINDS OF CONTENT

- SELF-PROMOTION CAPACITY

- SOURCE OF ENTERTAINMENT

- ONLINE SALE

"Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectuer"

TANGET OF ENEMIES AND PROBLEMS WITH SOCIAL MEDIATROLLS ON SOCIAL MEDIA

PERSISTENT TROLLS

FUNNY TROLLS

OPORTUNISTIC TROLLS

GOSSIPING TROLLS

TROLLS OF THE RAE

INSULT TROLLS

TROLLS SPAMMER

TROLLS OF HYPE

TROLLS OFF TROPIC

TROLLS FEW WORDS

HelpUP is the first social network aimed at volunteering. Where you can find the social project in which to collaborate as a volunteer or through a donation.

VOLUNTEERING

- Volunteering between campuses and classrooms.

- Professional and entrepreneurial talent.

- Connected to the mobilization.

- The stoty for social transformation.

- The generation of the community fabric.

- The accompaniment revolution.

- Free time that breaks barries.

- A shared learning path.

Eight great trends and facets of volunteering:

I think social networks are really helpful to know everiting around the world. On the other hand, it is a good tool to help us heach other it we have a problem. In short, social networks are useful in our lives.

I think that the social media are a good way to comunicate ,but they have his desadvantages,the people can have your ubication of your house because you think that are good people

Our personal opinion about social networks

Escribe un título

lunarlogitech

Social Media vs. Real Life: The Battle for Genuine Connections

In today’s digital age, social media has become an integral part of our daily lives. Platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Snapchat have revolutionized the way we connect with others, allowing us to effortlessly stay in touch with friends, family, and even strangers from across the globe. However, as our reliance on social media grows, it begs the question – what impact does this have on our real-life interactions? Are we sacrificing genuine human connections for the allure of virtual friendships and online validation? This article delves into the complex dynamics between social media and real-life interaction, exploring the advantages and disadvantages of each and shedding light on the potential consequences of prioritizing our digital relationships over face-to-face communication. Join us as we navigate this evolving landscape and unravel the true significance of social media in our lives.

Disadvantages

What are the differences between social media and face-to-face social interactions in the real world, what is the impact of social media on in-person interactions, what makes real-life interaction superior, the digital divide: exploring the impact of social media on real-life interactions, from likes to handshakes: navigating the balance between social media and real-life connections, beyond the screen: unveiling the complex relationship between social media and face-to-face interaction.

- Increased Connectivity: One advantage of social media compared to real-life interaction is the ability to connect with a larger and more diverse group of people. Social media platforms allow individuals to connect with others from different parts of the world, regardless of geographical boundaries. This increased connectivity opens up opportunities for cultural exchange, networking, and collaboration that may not be as easily accessible in real-life interactions.

- Enhanced Communication: Social media provides various tools and platforms that can enhance communication in ways that real-life interactions may not always be able to. For example, through social media, individuals can instantly share information, photos, videos, and updates with a wide audience. This quick and efficient communication allows for the rapid dissemination of information, facilitating discussions, organizing events, and even raising awareness about important social issues. Additionally, social media platforms often offer features such as translation tools, which can overcome language barriers and enable effective communication between individuals who speak different languages.

- Lack of Authenticity: One major disadvantage of social media compared to real-life interaction is the lack of authenticity. On social media, people tend to curate and present a carefully constructed image of themselves, often only showcasing the highlights of their lives. This can create a distorted perception of reality and lead to feelings of inadequacy or unrealistic expectations. In contrast, real-life interactions allow for genuine and unfiltered communication, where individuals can express their true emotions, thoughts, and personalities, fostering deeper and more meaningful connections.

- Negative Impact on Mental Health: Another drawback of excessive social media usage is its potential negative impact on mental health. Studies have shown that spending excessive amounts of time on social media platforms can contribute to feelings of loneliness, depression, and anxiety. The constant comparison to others’ seemingly perfect lives, the fear of missing out (FOMO), and the pressure to conform to societal standards can all take a toll on individuals’ well-being. Real-life interactions, on the other hand, provide opportunities for face-to-face connections, emotional support, and human touch, which are essential for maintaining good mental health.

Social media provides a platform for communication, but it lacks the depth and authenticity of face-to-face interactions. Through social media, we may connect with others, but we miss out on the nuances of body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice. These subtleties play a crucial role in understanding and building relationships. While social media creates a sense of connection, it cannot replace the richness and depth of real-world social interactions.

Social media’s emphasis on brevity and instant gratification often leads to shallow and superficial interactions. The lack of nonverbal cues and the ability to truly connect on a deeper level hinder the development of genuine relationships. While social media has its benefits, it cannot fully replace the authenticity and depth of face-to-face interactions.

The impact of social media on in-person interactions is significant. With the veil provided by the internet, individuals often feel more comfortable expressing their thoughts without considering the consequences. This can lead to unfiltered conversations that may not occur in face-to-face interactions. The lack of accountability and immediate feedback in online interactions can also hinder the development of effective communication skills needed in real-life conversations. As a result, social media can detrimentally affect the quality and authenticity of in-person interactions.

Social media’s anonymity can lead to uninhibited expression, hindering the development of essential communication skills required for real-life conversations, ultimately compromising the authenticity and quality of in-person interactions.

Real-life interactions have a unique advantage over virtual connections. They not only promote good health by positively shaping individuals’ lifestyle choices but also offer emotional support to mitigate the detrimental impact of stress. Through meaningful social connections, people find a sense of purpose and meaning in life. These real-time interactions foster a deeper understanding and empathy, which cannot be fully replicated online. The richness of face-to-face conversations and the ability to physically engage with others make real-life interactions superior, providing a holistic experience that positively impacts overall well-being.

Real-life interactions provide a sense of purpose and meaning, promote good health, offer emotional support, and foster a deeper understanding and empathy that cannot be fully replicated online. The richness of face-to-face conversations and physical engagement make real-life interactions superior, positively impacting overall well-being.

In an increasingly interconnected world, social media has become an integral part of our daily lives, transforming the way we communicate and interact with others. However, it is crucial to examine the impact of this digital revolution on our real-life interactions. While social media offers the convenience of staying connected with friends and family across the globe, it also poses challenges to face-to-face communication, leading to a potential digital divide. This article explores the impact of social media on our ability to connect authentically and the need to strike a balance between virtual interactions and meaningful real-life connections.

Speaking, social media has become an essential part of our daily lives, transforming the way we interact with others. However, it is important to consider the impact it has on our real-life connections. While social media allows us to stay connected with loved ones worldwide, it also presents challenges to face-to-face communication, potentially creating a digital divide. Finding a balance between virtual interactions and meaningful real-life connections is crucial.

In today’s digital age, social media has become an integral part of our lives, offering a platform to connect and engage with others. However, it is essential to strike a balance between our online presence and real-life connections. While likes and comments can provide a sense of validation, nothing beats the authenticity of face-to-face interactions. It is crucial to step away from the screen, go out, and engage with people in the real world. By finding this equilibrium, we can foster meaningful relationships and embrace the richness of genuine human connections.

Speaking, social media has become a vital part of our lives, allowing us to connect with others. However, it is crucial to balance our online presence with real-life connections. While likes and comments can feel validating, nothing compares to genuine face-to-face interactions. It is important to step away from screens and engage with people in the real world, fostering meaningful relationships and embracing the authenticity of human connections.

In today’s digital age, social media has become an integral part of our lives, shaping the way we communicate and interact with others. However, its impact extends beyond the screen, as it influences our face-to-face interactions as well. While social media offers convenience and connectivity, it also poses challenges to genuine human connection. Studies reveal that excessive use of social media can lead to decreased empathy and social skills, and even contribute to feelings of loneliness and isolation. Striking a balance between online and offline communication is crucial to maintain meaningful relationships in the modern world.

Speaking, social media has become an integral part of our lives, shaping communication and interactions. However, it also presents challenges to genuine human connection, as excessive use can lead to decreased empathy, social skills, and feelings of loneliness. Striking a balance between online and offline communication is crucial for maintaining meaningful relationships in the digital age.

In conclusion, while social media has undoubtedly revolutionized the way we communicate and connect with others, it cannot replace the depth and authenticity of real-life interaction. While virtual platforms offer convenience and instant gratification, they lack the nuances of body language, tone of voice, and the ability to empathize on a deeper level. Real-life interactions allow for the formation of genuine connections, fostering emotional and social intelligence, and building meaningful relationships. It is essential to strike a balance between the virtual and real world, leveraging the advantages of social media while also prioritizing and nurturing personal connections offline. By consciously allocating time for face-to-face interactions, we can cultivate a richer and more fulfilling social life, ultimately leading to greater overall well-being and satisfaction. So, let us embrace the digital era but not forget the value and importance of genuine human connections in our lives.

Relacionados

Related stories, unveiling to kill a mockingbird’s real-life ties: eye-opening connections.

Unleash Your Creativity with Python: Real-Life Projects for Beginners

Unreal Moments: When Life Fails to Feel Real

You may have missed.

Unveiling Real-Life Bendy & Ink Machine Characters: A Captivating Encounter!

Discover Nature’s Curves: Embracing Organic Shapes in Everyday Life!

Molly’s Game: Unveiling the Real-Life Molly Behind the Sensational Movie!

- Personality

Self-Presentation in the Digital World

Do traditional personality theories predict digital behaviour.

Posted August 31, 2021 | Reviewed by Chloe Williams

- What Is Personality?

- Find a therapist near me

- Personality theories can help explain real-world differences in self-presentation behaviours but they may not apply to online behaviours.

- In the real world, women have higher levels of behavioural inhibition tendencies than men and are more likely to avoid displeasing others.

- Based on this assumption, one would expect women to present themselves less on social media, but women tend to use social media more than men.

Digital technology allows people to construct and vary their self-identity more easily than they can in the real world. This novel digital- personality construction may, or may not, be helpful to that person in the long run, but it is certainly more possible than it is in the real world. Yet how this relates to "personality," as described by traditional personality theories, is not really known. Who will tend to manipulate their personality online, and would traditional personality theories predict these effects? A look at what we do know about gender differences in the real and digital worlds suggests that many aspects of digital behaviour may not conform to the expectations of personality theories developed for the real world.

Half a century ago, Goffman suggested that individuals establish social identities by employing self-presentation tactics and impression management . Self-presentational tactics are techniques for constructing or manipulating others’ impressions of the individual and ultimately help to develop that person’s identity in the eyes of the world. The ways other people react are altered by choosing how to present oneself – that is, self-presentation strategies are used for impression management . Others then uphold, shape, or alter that self-image , depending on how they react to the tactics employed. This implies that self-presentation is a form of social communication, by which people establish, maintain, and alter their social identity.

These self-presentational strategies can be " assertive " or "defensive." 1 Assertive strategies are associated with active control of the person’s self-image; and defensive strategies are associated with protecting a desired identity that is under threat. In the real world, the use of self-presentational tactics has been widely studied and has been found to relate to many behaviours and personalities 2 . Yet, despite the enormous amounts of time spent on social media , the types of self-presentational tactics employed on these platforms have not received a huge amount of study. In fact, social media appears to provide an ideal opportunity for the use of self-presentational tactics, especially assertive strategies aimed at creating an identity in the eyes of others.

Seeking to Experience Different Types of Reward

Social media allows individuals to present themselves in ways that are entirely reliant on their own behaviours – and not on factors largely beyond their ability to instantly control, such as their appearance, gender, etc. That is, the impression that the viewer of the social media post receives is dependent, almost entirely, on how or what another person posts 3,4 . Thus, the digital medium does not present the difficulties for individuals who wish to divorce the newly-presented self from the established self. New personalities or "images" may be difficult to establish in real-world interactions, as others may have known the person beforehand, and their established patterns of interaction. Alternatively, others may not let people get away with "out of character" behaviours, or they may react to their stereotype of the person in front of them, not to their actual behaviours. All of which makes real-life identity construction harder.

Engaging in such impression management may stem from motivations to experience different types of reward 5 . In terms of one personality theory, individuals displaying behavioural approach tendencies (the Behavioural Activation System; BAS) and behavioural inhibition tendencies (the Behavioural Inhibition System; BIS) will differ in terms of self-presentation behaviours. Those with strong BAS seek opportunities to receive or experience reward (approach motivation ); whereas, those with strong BIS attempt to avoid punishment (avoidance motivation). People who need to receive a lot of external praise may actively seek out social interactions and develop a lot of social goals in their lives. Those who are more concerned about not incurring other people’s displeasure may seek to defend against this possibility and tend to withdraw from people. Although this is a well-established view of personality in the real world, it has not received strong attention in terms of digital behaviours.

Real-World Personality Theories May Not Apply Online

One test bed for the application of this theory in the digital domain is predicted gender differences in social media behaviour in relation to self-presentation. Both self-presentation 1 , and BAS and BIS 6 , have been noted to show gender differences. In the real world, women have shown higher levels of BIS than men (at least, to this point in time), although levels of BAS are less clearly differentiated between genders. This view would suggest that, in order to avoid disapproval, women will present themselves less often on social media; and, where they do have a presence, adopt defensive self-presentational strategies.

The first of these hypotheses is demonstrably false – where there are any differences in usage (and there are not that many), women tend to use social media more often than men. What we don’t really know, with any certainty, is how women use social media for self-presentation, and whether this differs from men’s usage. In contrast to the BAS/BIS view of personality, developed for the real world, several studies have suggested that selfie posting can be an assertive, or even aggressive, behaviour for females – used in forming a new personality 3 . In contrast, sometimes selfie posting by males is related to less aggressive, and more defensive, aspects of personality 7 . It may be that women take the opportunity to present very different images of themselves online from their real-world personalities. All of this suggests that theories developed for personality in the real world may not apply online – certainly not in terms of putative gender-related behaviours.

We know that social media allows a new personality to be presented easily, which is not usually seen in real-world interactions, and it may be that real-world gender differences are not repeated in digital contexts. Alternatively, it may suggest that these personality theories are now simply hopelessly anachronistic – based on assumptions that no longer apply. If that were the case, it would certainly rule out any suggestion that such personalities are genetically determined – as we know that structure hasn’t changed dramatically in the last 20 years.

1. Lee, S.J., Quigley, B.M., Nesler, M.S., Corbett, A.B., & Tedeschi, J.T. (1999). Development of a self-presentation tactics scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 26(4), 701-722.

2. Laghi, F., Pallini, S., & Baiocco, R. (2015). Autopresentazione efficace, tattiche difensive e assertive e caratteristiche di personalità in Adolescenza. Rassegna di Psicologia, 32(3), 65-82.

3. Chua, T.H.H., & Chang, L. (2016). Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 190-197.

4. Fox, J., & Rooney, M.C. (2015). The Dark Triad and trait self-objectification as predictors of men’s use and self-presentation behaviors on social networking sites. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 161-165.

5. Hermann, A.D., Teutemacher, A.M., & Lehtman, M.J. (2015). Revisiting the unmitigated approach model of narcissism: Replication and extension. Journal of Research in Personality, 55, 41-45.

6. Carver, C.S., & White, T.L. (1994). Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 319.

7. Sorokowski, P., Sorokowska, A., Frackowiak, T., Karwowski, M., Rusicka, I., & Oleszkiewicz, A. (2016). Sex differences in online selfie posting behaviors predict histrionic personality scores among men but not women. Computers in Human Behavior, 59, 368-373.

Phil Reed, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology at Swansea University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Opinion

Are You the Same Person on Social Media as You Are in Real Life?

By Caroline Crosson Gilpin

- May 9, 2017

Do you ever suspect people are posting images on social media that show them in a one-dimensional way, to make others think they are perfect, with a perfect life?

Is your social media presence an accurate depiction of who you are in real life?

Talk with a classmate about social media personas, for famous people and for ordinary citizens, and how those personas are crafted and presented online.

In “ My So-Called (Instagram) Life ,” Clara Dollar writes:

“You’re like a cartoon character,” he said. “Always wearing the same thing every day.” He meant it as an intimate observation, the kind you can make only after spending a lot of time getting to know each other. You flip your hair to the right. You only eat ice cream out of mugs. You always wear a black leather jacket. I know you. And he did know me. Rather, he knew the caricature of me that I had created and meticulously cultivated. The me I broadcast to the world on Instagram and Facebook. The witty, creative me, always detached and never cheesy or needy. That version of me got her start online as my social media persona, but over time (and I suppose for the sake of consistency), she bled off the screen and overtook my real-life personality, too. And once you master what is essentially an onstage performance of yourself, it can be hard to break character. There was a time when I allowed myself to be more than what could fit onto a 2-by-4-inch screen. When I wasn’t so self-conscious about how I was seen. When I embraced my contradictions and desires with less fear of embarrassment or rejection. There was a time when I swore in front of my friends and said grace in front of my grandmother. When I wore lipstick after seeing “Clueless,” and sneakers after seeing “Remember the Titans.” When I flipped my hair every way, ate ice cream out of anything, and wore coats of all types and colors. Since then, I have consolidated that variety — scrubbed it away, really — to emerge as one consistently cool girl: one face, two arms, one black leather jacket.

Students: Read the entire article, then tell us:

— Could you identify with, or at least understand, Clara Dollar’s online persona problem, and how it conflicts with her real life needs and wants? Why or why not, and, if so, how? Do you think she will find a way to reconcile or integrate her online presence with her real life?

— Do you know others who have the same problem? What are their stories?

— Are you the same persona on social media as you are in real life? Why or why not? Give examples. Does your online persona prevent you from expressing yourself in a real way, and if so, are you interested in changing it? Why or why not?

Students 13 and older are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.

Balancing Social Media and Real-Life for Communication

Eloquence Everly

As an affiliate, we may earn a commission from qualifying purchases. We get commissions for purchases made through links on this website from Amazon and other third parties.

Welcome to our article on balancing social media and real-life interactions for effective communication . In today’s digital age, social media has become an integral part of our lives, allowing us to connect with others and share our experiences. However, it’s essential to find a balance between our online presence and our real-life interactions to ensure that we communicate effectively in both realms.

Social media offers numerous benefits, such as staying connected with friends and family, discovering new opportunities, and accessing information at our fingertips. However, excessive use can hinder our ability to engage in face-to-face interactions, impact our mental and physical health, and create a sense of disconnection from the world around us. It’s important to navigate the digital landscape with intention and find a healthy balance between our online and offline lives.

Key Takeaways:

- Find a balance between social media and real-life interactions for effective communication .

- Excessive use of social media can hinder face-to-face interactions and impact our well-being.

- Stay connected online while prioritizing meaningful conversations and experiences offline.

- Be mindful of the negative impacts of social media and take steps to manage your digital presence.

- By setting boundaries and using technology wisely, we can ensure that social media enhances our real-life communication .

The Importance of Finding Balance

Engaging in healthy social media communication means finding a balance between online and offline interactions . In today’s digital age, social media has become an integral part of our lives, allowing us to connect with others and share our thoughts and experiences. However, excessive use of social media can have detrimental effects on our real-life communication skills and overall well-being.

Developing strong communication skills requires regular face-to-face interactions and the ability to effectively convey our thoughts, emotions, and ideas. Real-life conversations provide us with opportunities to practice active listening, interpret non-verbal cues, and engage in meaningful discussions.

Social media interactions , on the other hand, often rely solely on digital communication , which can lack the depth and nuance of offline interactions . It is essential to prioritize real-life connections and engage in offline interactions to sharpen our communication skills and foster genuine relationships.

However, this doesn’t mean that we should completely cut off our online interactions . Social media can play a significant role in our lives, allowing us to stay connected with friends and family, access valuable information, and engage in various communities and interests.

By finding a balance between our online and offline interactions , we can reap the benefits of both worlds. We can enhance our communication skills through real-life interactions while using social media as a tool for staying connected and engaging with a broader network.

The Power of Real-Life Communication

Offline interactions offer unique advantages that cannot be replicated through online interactions . Through face-to-face conversations, we can establish deeper connections, understand others on a more personal level, and build trust and rapport. Real-life communication allows us to read facial expressions, body language, and tone of voice , providing us with valuable context and enhancing the emotional connection.

Additionally, offline interactions allow us to engage in shared activities and experiences, fostering a sense of camaraderie and belonging. Whether it’s attending social events, participating in hobbies, or simply spending quality time together, these offline interactions strengthen our relationships and contribute to our overall well-being.

While social media can be a convenient and efficient way to communicate, it should never replace the richness and authenticity of face-to-face interactions. By finding a healthy balance between our online and offline interactions, we can cultivate strong communication skills and foster meaningful connections with others.

Stay tuned for the next section, where we will explore the signs of an unbalanced social media use and its negative impacts on our well-being.

Signs of an Unbalanced Social Media Use

Unbalanced social media use can have a negative impact on our well-being and daily lives. It is essential to recognize the signs of unhealthy social media habits to ensure a healthier and more balanced approach to our online interactions .

1. Checking Social Media During Work or Important Events

One of the signs of an unbalanced social media use is constantly checking social media platforms during work or important events. Whether it’s scrolling through news feeds, responding to messages, or liking posts, this behavior can hinder productivity and negatively affect our professional or personal lives.

2. Feeling Anxious When Separated from Social Media

A telltale sign of social media addiction or an unhealthy reliance on social media is feeling anxious or restless when separated from our devices. If we experience discomfort or a constant need to check our social media accounts, it may indicate an unhealthy attachment and lack of balance in our online and offline lives.

3. Experiencing Negative Impacts on Mental Health

An unbalanced use of social media can have detrimental effects on our mental health. Consuming excessive amounts of social media content can lead to feelings of comparison, inadequacy, and loneliness. Moreover, constantly being engaged in social media can disrupt sleep patterns and lead to decreased overall well-being.

Unbalanced social media use can lead to a range of negative consequences, affecting our productivity, mental health, and overall well-being. Recognizing these signs is crucial in order to address the issue and find a healthier balance in our online and offline lives.

By being aware of these signs, we can take steps towards achieving a more balanced approach to social media. It is essential to set boundaries , limit screen time, and prioritize real-life interactions to maintain a healthy balance between our online and offline lives. Prioritizing self-care, engaging in offline activities, and seeking support when needed are also important in overcoming social media addiction or unhealthy usage patterns.

Positive Aspects of Social Media on Real-Life Communication

Social media has revolutionized the way we communicate, bringing numerous positive changes to our real-life interactions. Let’s explore some of the key advantages it offers.

Increased Connectivity

Social media platforms have made it easier than ever to connect with people across the globe. We can maintain relationships with friends, family, and acquaintances, regardless of geographical distances. Through messaging, video calls, and sharing updates, we can stay connected and bridge the gap created by physical barriers.

Information Dissemination

Social media serves as a powerful tool for spreading information quickly and effectively. Whether it’s news, events, or educational content, social media platforms enable us to share valuable information with a wide audience. This enhances our ability to stay informed and engaged with current issues.

Networking Opportunities

Social media platforms provide excellent networking opportunities for personal and professional growth. We can connect with like-minded individuals, industry experts, and potential collaborators or business partners. Through groups and communities, we can engage in meaningful conversations , exchange ideas, and expand our network, opening up new possibilities.

Support and Advocacy

Social media has become a vital platform for support and advocacy . It brings together communities facing similar challenges, allowing them to share experiences, offer support, and find comfort in knowing they are not alone. Social media also amplifies voices and raises awareness about important social issues, providing a space for advocacy and fostering positive change.

“Social media has given us the power to connect, share knowledge, and drive meaningful conversations for a better world.”

With all these positive aspects, it’s clear that social media has significantly enhanced our real-life communication experiences. It has given us the ability to connect, collaborate, and make a difference. However, we must also be mindful of the potential challenges and negative impacts that can arise, which we will explore in the next section.

Negative Aspects of Social Media on Real-Life Communication

In our digital age, social media has become an integral part of our lives, offering numerous benefits and opportunities. However, it is important to acknowledge the negative impacts it can have on real-life communication. Let’s explore some of the drawbacks:

1. Reduced Face-to-Face Interaction

Social media platforms often replace traditional face-to-face interactions, leading to a decline in meaningful in-person connections. Spending excessive time online can isolate individuals and hinder the development of strong interpersonal relationships.

2. Superficial Relationships

While social media allows us to connect with a wide network of individuals, it can result in superficial relationships lacking depth and genuine connection. Limited interaction through text and images can prevent the development of authentic emotional bonds.

3. Distraction from Real-Life Interactions

The constant presence of social media can be a major distraction , diverting our attention from real-life interactions and experiences. Engaging in online activities can reduce the quality and quantity of time spent with loved ones and hinder our ability to communicate effectively in real-world scenarios.

4. Miscommunication and Ambiguity

Interacting through text-based communication on social media platforms often leads to misinterpretation and misunderstandings. The absence of non-verbal cues and tone of voice can make it challenging to convey emotions accurately, resulting in miscommunication and unnecessary conflicts.

5. Cyberbullying and Harassment

Social media platforms provide a breeding ground for cyberbullying and harassment , causing significant harm to individuals’ mental and emotional well-being. The anonymity and distance offered by these platforms can embolden individuals to engage in harmful behaviors without facing immediate consequences.

6. Privacy Concerns

The vast amount of personal information shared on social media platforms raises privacy concerns . Oversharing can lead to vulnerabilities, compromising personal safety and potentially contributing to identity theft or online stalking.

7. Comparison and Self-Esteem Issues

Social media feeds are filled with carefully curated highlight reels that may foster comparison and negatively impact individuals’ self-esteem. Endless streams of idealized lifestyles and appearances can create unrealistic expectations and feelings of inadequacy.

It is crucial to be aware of these negative aspects of social media and take proactive measures to minimize their impact on our real-life communication. By understanding the potential consequences, we can navigate social media platforms responsibly, ensuring a healthier balance between online and offline interactions.

Strategies for Balancing Social Media and Real-Life Communication

To achieve a healthy balance between social media and real-life interactions , we need to implement a range of strategies. By prioritizing our well-being and being mindful of how we engage with technology, we can foster meaningful connections and enhance our overall communication skills .

Set Boundaries

Setting boundaries on our social media use is essential. We can allocate specific timeframes for checking social media and establish technology-free zones in our daily routines. By creating clear boundaries, we can prevent social media from overtaking our lives and interfere with face-to-face interactions.

Practice Digital Detox

Regularly taking breaks from social media can have a positive impact on our mental well-being. During a digital detox, we can disconnect from our screens and engage in offline activities. This break allows us to recharge, be present in the moment, and strengthen our real-life connections.

Quote: “Taking a break from social media can help us reconnect with ourselves and others in meaningful ways.” – John Smith, Psychologist

Engage in Meaningful Conversations

When engaging with others, both online and offline, we should strive for meaningful conversations. This means actively listening, sharing our thoughts and feelings, and fostering deeper connections. By engaging in conversations that go beyond superficiality, we can create more fulfilling relationships.

Be Mindful of Privacy

Protecting our privacy online is crucial. We should be cautious about the personal information we share on social media platforms and adjust privacy settings accordingly. Being mindful of privacy helps us maintain control over our digital presence and safeguard our personal lives.

Promote Digital Literacy

Understanding the digital landscape empowers us to navigate it wisely. By promoting digital literacy, we can educate ourselves and others about online safety, responsible online behavior, and the potential pitfalls of excessive social media use. With digital literacy, we can make informed decisions and use social media to our advantage.

Encourage Offline Activities

We should actively encourage and participate in offline activities. This can include hobbies, physical exercise, spending time with loved ones, and exploring the world around us. By diversifying our experiences, we become less reliant on social media for entertainment and develop a more balanced lifestyle.

Use Technology Wisely

Technology is a valuable tool, but it should not replace real-life communication. We should use technology wisely by leveraging its benefits to enhance our connections and experiences. This means using social media purposefully, being selective about the platforms we engage with, and ensuring that technology serves as a supplement rather than a substitute for real-life interaction.

In conclusion, finding a balance between social media and real-life communication requires intentional effort. By setting boundaries, practicing digital detox, engaging in meaningful conversations, being mindful of privacy, promoting digital literacy, encouraging offline activities, and using technology wisely, we can cultivate healthier relationships, improve our communication skills , and lead more fulfilling lives.

Impact on Intimate Relationships

When it comes to intimate relationships, social media can have both positive and negative impacts. On one hand, it allows couples to maintain constant communication and share moments of their lives with each other, no matter the distance. Platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat provide a space for couples to express affection publicly, creating a sense of connection and intimacy.

However, excessive use of social media in relationships can lead to negative consequences. Jealousy and insecurity can arise when partners see each other’s interactions with others on social media. It’s easy to feel threatened or inadequate when comparing oneself to the carefully curated highlight reels of others. Privacy concerns also come into play, as couples may feel compelled to constantly share their relationship online, potentially exposing themselves to unwanted attention or judgment.

Furthermore, spending excessive time on social media can take away from the quality time couples spend together. Instead of engaging in meaningful face-to-face interactions, partners may find themselves scrolling through their feeds, distracted by the allure of virtual connections. This can weaken the bond between partners and lead to feelings of disconnect.

“Social media has become a breeding ground for jealousy, comparison, and insecurity in relationships. It’s important for couples to establish boundaries and prioritize each other’s emotional needs offline.”

Impact of Social Media on Jealousy and Insecurity

Social media has the power to intensify feelings of jealousy and insecurity within intimate relationships. Seeing your partner interact with others online can evoke a range of emotions, from fleeting pangs of jealousy to deep-seated insecurities.

The visibility of likes, comments, and direct messages on social media platforms can fuel feelings of jealousy. It’s easy to misinterpret innocent interactions as signs of potential infidelity or disinterest, leading to unnecessary conflict and mistrust. Insecurity can be magnified when comparing oneself to the idealized versions of others portrayed on social media, creating a sense of inadequacy.

It’s essential for couples to address these feelings and have open, honest conversations about their concerns. Establishing clear boundaries and developing trust offline can help mitigate the negative impact of social media on jealousy and insecurity .

Privacy Concerns in Intimate Relationships

Social media blurs the boundaries between public and private life, which can lead to privacy concerns in intimate relationships. Constantly sharing every aspect of the relationship online may expose it to unwanted scrutiny or judgment from others. Partners might feel pressured to display their love publicly, potentially compromising their privacy and creating tension in the relationship.

Additionally, the permanence of online content can lead to regrettable incidents. Innocent posts or comments made in the heat of the moment can have long-lasting consequences, adding strain and even damaging the relationship.

“Maintaining a sense of privacy is crucial for the health of an intimate relationship. Couples should have open discussions about what is comfortable to share online and establish boundaries that protect their privacy.”

Ultimately, finding a balance between sharing aspects of the relationship online and maintaining privacy is crucial for the health of intimate relationships in the digital age.

Impact on Family Dynamics

Social media has become an integral part of our daily lives, including the dynamics within our families. While it can offer a means of staying connected and providing support, excessive use of social media and devices can have a detrimental impact on family relationships.

When family members prioritize their devices over in-person interactions, it can lead to a breakdown in communication and a sense of isolation among family members. Instead of engaging in meaningful conversations and spending quality time together, everyone may find themselves engrossed in their screens, missing out on valuable moments and opportunities for bonding.

Managing screen time and setting boundaries is crucial for maintaining healthy family relationships. By limiting the amount of time spent on devices and promoting offline activities, families can create an environment that encourages face-to-face interactions and strengthens their connections.

Effects of Excessive Device Use on Family Dynamics

Excessive use of devices and social media can have several negative effects on family dynamics:

- Breakdown in Communication : Constant distractions from devices can hinder effective communication within the family. It becomes challenging to have meaningful conversations and address important issues when everyone is preoccupied with their online lives.

- Isolation and Disconnection: Excessive screen time can create a sense of isolation among family members. Instead of engaging with each other, individuals may feel disconnected and turn to virtual interactions for social connection.

- Conflict and Misunderstandings: Spending excessive time on social media can lead to misunderstandings and conflicts within the family. Miscommunication can occur when important messages are conveyed through digital platforms rather than in person.

- Distraction from Responsibilities: When devices take precedence over family responsibilities, it can lead to neglect of household chores, family commitments, and even compromised academic and professional performance.

Strategies for Managing Screen Time and Promoting Healthy Family Dynamics

It is essential for families to find a balance between digital and offline interactions and establish guidelines for healthy device use. Here are some strategies to manage screen time and promote healthy family dynamics:

- Set Screen Time Limits: Establish specific time limits for device use and encourage dedicated family time where devices are put aside.

- Create Device-Free Zones: Designate certain areas or times in the house where devices are not allowed, such as the dinner table or during family outings.

- Engage in Family Activities: Plan and engage in activities that promote interaction and quality time together, such as game nights, outings, or shared hobbies.

- Encourage Open Communication: Foster an environment where family members feel comfortable discussing their experiences and concerns related to social media and device use.

- Lead by Example: Parents should model responsible technology use by practicing healthy device habits themselves.

By implementing these strategies, families can ensure that social media and devices do not negatively impact their dynamics. Balancing screen time with face-to-face interactions is key to creating a nurturing and connected family environment.

In the next section, we will explore the impact of social media on intimate relationships and discuss strategies for maintaining a healthy balance.

In today’s digital world, it is essential to find a balance between social media and real-life communication. While social media offers numerous benefits, it is crucial to be aware of its potential negative effects on face-to-face interactions. By implementing a few strategies and adopting a mindful approach, we can ensure that social media enhances, rather than hinders, our real-life communication.

Setting boundaries is the first step towards finding balance. It is important to establish limits on the time spent on social media and prioritize in-person interactions with family, friends, and colleagues. By doing so, we can foster stronger relationships and improve our communication skills.

Practicing digital detox is another effective strategy. Taking regular breaks from social media allows us to reconnect with ourselves and the world around us. During these breaks, engaging in offline activities such as hobbies, exercise, and spending time in nature can enrich our lives and contribute to a healthier lifestyle.

Engaging in meaningful conversations both online and offline is key to maintaining healthy relationships. By actively listening, expressing empathy, and sharing genuine thoughts and feelings, we can deepen our connections and enhance the quality of our communication. Additionally, promoting responsible online behavior, such as being mindful of privacy settings and avoiding cyberbullying, ensures a safe and positive digital space for everyone.

About the author

Latest Posts

Overcoming Language Barrier for Immigrants

Immigrants face significant challenges due to language barriers when they relocate to a new country. This can hinder their ability to communicate effectively, obtain basic needs, and integrate into their new community. Language barriers impact various aspects of their lives, […]

Overcoming Language Barriers in Learning

Language barriers can significantly impact the learning experience and academic performance of students. It is essential to address these barriers to ensure that all students have equal opportunities to succeed in education. By overcoming language barriers, students can improve their […]

Overcome Language Barriers with Effective Solutions

In today’s globalized world, language barriers can pose significant challenges to effective communication. However, there are various solutions available to overcome these barriers and bridge the language gap. By utilizing language translation services, language interpretation services, and other language access […]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 06 October 2020

Authentic self-expression on social media is associated with greater subjective well-being

- Erica R. Bailey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2924-2500 1 na1 ,

- Sandra C. Matz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0969-4403 1 na1 ,

- Wu Youyou 2 &

- Sheena S. Iyengar 1

Nature Communications volume 11 , Article number: 4889 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

112k Accesses

54 Citations

427 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

Social media users face a tension between presenting themselves in an idealized or authentic way. Here, we explore how prioritizing one over the other impacts users’ well-being. We estimate the degree of self-idealized vs. authentic self-expression as the proximity between a user’s self-reported personality and the automated personality judgements made on the basis Facebook Likes and status updates. Analyzing data of 10,560 Facebook users, we find that individuals who are more authentic in their self-expression also report greater Life Satisfaction. This effect appears consistent across different personality profiles, countering the proposition that individuals with socially desirable personalities benefit from authentic self-expression more than others. We extend this finding in a pre-registered, longitudinal experiment, demonstrating the causal relationship between authentic posting and positive affect and mood on a within-person level. Our findings suggest that the extent to which social media use is related to well-being depends on how individuals use it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Variation in social media sensitivity across people and contexts

Characteristics of online user-generated text predict the emotional intelligence of individuals

Like-minded sources on Facebook are prevalent but not polarizing

Introduction.

Social media can seem like an artificial world in which people’s lives consist entirely of exotic vacations, thriving friendships, and photogenic, healthy meals. In fact, there is an entire industry built around people’s desire to present idealistic self-representations on social media. Popular applications like FaceTune, for example, allow users to modify everything about themselves, from skin tone to the size of their physical features. In line with this “self-idealization perspective”, research has shown that self-expressions on social media platforms are often idealized, exaggerated, and unrealistic 1 . That is, social media users often act as virtual curators of their online selves 2 by staging or editing content they present to others 3 .

A contrasting body of research suggests that social media platforms constitute extensions of offline identities, with users presenting relatively authentic versions of themselves 4 . While users might engage in some degree of self-idealization, the social nature of the platforms is thought to provide a degree of accountability that prevents individuals from starkly misrepresenting their identities 5 . This is particularly true for platforms such as Facebook, where the majority of friends in a user’s network also have an offline connection 6 . In fact, modern social media sites like Facebook and Instagram are far more realistic than early social media websites such as Second Life, where users presented themselves as avatars that were often fully divorced from reality 7 . In line with this authentic self-expression perspective, research has shown that individuals on Facebook are more likely to express their actual rather than their idealized personalities 8 , 9 .

The desire to present the self in a way that is ideal and authentic is not mutually exclusive; on the contrary, an individual is likely to desire both simultaneously 10 . This occurs in part because self-idealization and authentic self-expression fulfill different psychological needs and are associated with different psychological costs. On the one hand, self-idealization has been called a “fundamental part of human nature” 11 because it allows individuals to cultivate a positive self-view and to create positive impressions of themselves in others 12 . In addition, authentic self-expression allows individuals to verify and affirm their sense of self 13 , 14 which can increase self-esteem 15 , and a sense of belonging 16 . On the other hand, self-idealizing behavior can be psychologically costly, as acting out of character is associated with feelings of internal conflict, psychological discomfort, and strong emotional reactions 17 , 18 ; individuals may also possess characteristics that are more or less socially desirable, bringing their desire to present themselves in an authentic way into conflict with their desire to present the best version of themselves.

Here, we explore the tension between self-idealization and authentic self-expression on social media, and test how prioritizing one over the other impacts users’ well-being. We focus our analysis on a core component of the self: personality 19 . Personality captures fundamental differences in the way that people think, feel and behave, reflecting the psychological characteristics that make individuals uniquely themselves 20 , 21 . Building on the Five Factor Model of personality 22 , we test the extent to which authentic self-expression of personality characteristics are related to Life Satisfaction, hypothesizing that greater authentic self-expression will be positively correlated with Life Satisfaction. In exploratory analyses, we also consider whether this relationship is moderated by the personality characteristics of the individual. That is, not all individuals might benefit from authentic self-expression equally. Given that some personality traits are more socially desirable than others 23 , individuals who possess more desirable personality traits are likely to experience a reduced tension between self-idealization and authentic self-expression. Consequently, individuals with more socially desirable profiles might disproportionality benefit from authentic self-expression because the motivational pulls of self-idealization and authentic self-expression point in the same—rather than the opposite—direction.

Previous literature on authentic self-expression has predominantly relied on self-reported perceptions of authenticity as (i) a state of feeling authentic 24 , or (ii) a judgement about the honesty or consistency of one’s self 25 . However, such self-reported measures have been shown to be biased by valence states, and social desirability 26 , 27 . To overcome these limitations, in Study 1 we introduce a measure of Quantified Authenticity. If authenticity is most simply defined as the unobstructed expression of one’s self 28 , then authenticity can be estimated as the proximity of an individual’s self-view and their observable self-expression. We calculate Quantified Authenticity by comparing self-reported personality to personality judgements made by computers on the basis of observable behaviors on Facebook (i.e., Likes and status updates).

By observing self-presentation on social media and comparing it to the individual’s self-view, we are able to quantify the extent to which an individual deviates from their authentic self. That is, we locate each individual on a continuum that ranges from low authenticity (i.e., large discrepancy between the self-view and observable self-expression) to high authenticity (i.e., perfect alignment between the self-view and observable self-expression). Importantly, our approach rests on the assumption that any deviation from the self-view on social media constitutes an attempt to present oneself in a more positive light, and therefore a form of self-idealization. While a deviation could theoretically indicate both self-idealization and self-deprecation, it is unlikely that users will deviate from their true selves in a way that makes them look worse in the eyes of others. A strength of our measures is that we do not postulate that self-idealization takes a particular form of deviation from the self or is associated with striving for a particular profile. Although research suggests that there are certain personality traits that are more desirable on average 29 , 30 , the extent to which a person sees scoring high or low on a given trait is likely somewhat idiosyncratic and depends—at least in part—on other people in their social network. For example, behaving in a more extraverted way might be self-enhancing for most people; however, there might be individuals for whom behaving in a more introverted way might be more desirable (e.g. because the norm of their social network is more introverted). Hence, our conceptualization of Quantified Authenticity allows for deviations in different directions (see Supplementary Information for more detail).

Quantified Authenticity and subjective well-being

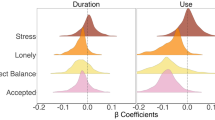

In Study 1, we analyzed the data of 10,560 Facebook users who had completed a personality assessment and reported on their Life Satisfaction through the myPersonality application 31 , 32 . To estimate the extent to which their Facebook profiles represent authentic expressions of their personality, we compared their self-ratings to two observational sources: predictions of personality from Facebook Likes ( N = 9237) 33 and predictions of personality from Facebook status updates ( N = 3215) 34 . These are based on recent advances in the automatic assessment of psychological traits from the digital traces they leave on Facebook 35 . For each of the observable sources, we calculated Quantified Authenticity as the inverse Euclidean distance between all five self-rated and observable personality traits. Our measure of Quantified Authenticity exhibits a desirable level of variance, ranging all the way from highly authentic self-expression to considerable levels of self-idealization (see ridgeline plot of Quantified Authenticity calculated for self-language and Self-Likes in Supplementary Fig. 3 , see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 for zero-order correlations among variables).

To test the extent to which authentic self-expression is related to Life Satisfaction, we ran linear regression analyses predicting Life Satisfaction from the two measures of Quantified Authenticity (Likes, status updates). The results support the hypothesis that higher levels of authenticity (i.e. lower distance scores) are positively correlated with Life Satisfaction (Table 1 , Model 1 without controls). These effects remained statistically significant when controlling for self-reported personality traits. Additionally, we included a control variable for the overall extremeness of an individual’s personality profile (deviation from the population mean across all five traits), as people with more extreme personality profiles might find it more difficult to blend into society and therefore experience lower levels of well-being 36 (see Table 1 , Model 2 with controls; the results are largely robust when controlling for gender and age, see Supplementary Table 3 ; see Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 for interactions between individual self-reported and predicted personality traits).

To further explore the mechanisms of Quantified Authenticity, we conducted analyses that distinguished between normative self-enhancement (i.e., rating oneself as more Extraverted, Agreeable, Conscientiousness, Emotionally Stable, and Open-minded than is indicated by one’s Facebook behavior) from self-deprecation (i.e., rating oneself lower on all of these traits). While normative self-enhancement has a negative effect on well-being, normative self-deprecation has no effect. These findings suggest that self-enhancement specifically, rather than overall self-discrepancy/lack of authenticity, is detrimental to subjective well-being (see Supplementary Fig. 4 ).

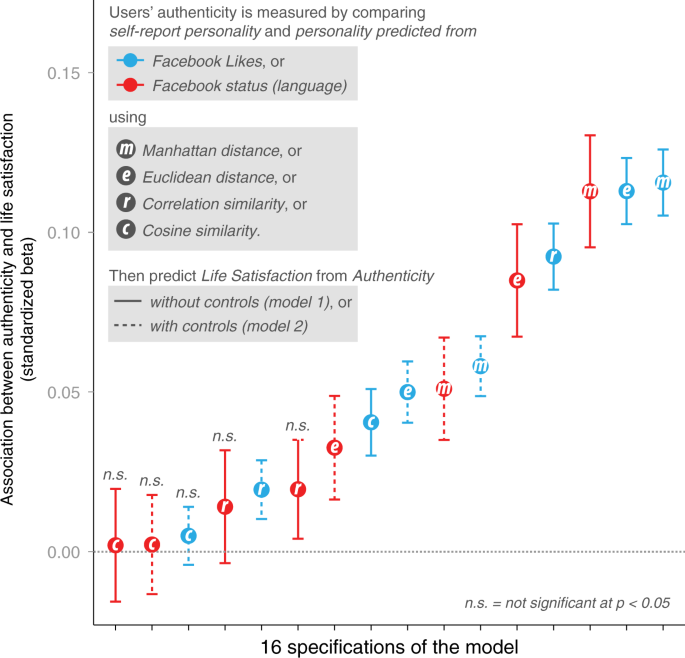

To test the robustness of our effects, we regressed Life Satisfaction on three additional measures of Quantified Authenticity (i.e., calculated using Manhattan Distance, Cosine Similarity, and Correlational Similarity; see SI for details on these measures). In both comparison sets (likes and status updates), we found significant and positive correlations between the various ways of estimating Quantified Authenticity (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 ). The standardized beta-coefficients across all four metrics of Quantified Authenticity and observable sources are displayed in Fig. 1 . Despite variance in effect sizes across measures and model specifications, the majority of estimates are statistically significant and positive (11 out of 16). Importantly, no coefficients were observed in the opposite direction. These results suggest that those who are more authentic in their self-expression on Facebook (i.e., those who present themselves in a way that is closer to their self-view) also report higher levels of Life Satisfaction.

Figure 1 presents standardized beta coefficients for Quantified Authenticity using ordinary least squares regressions in 16 individual regressions predicting Life Satisfaction. Quantified Authenticity is significantly associated with Life Satisfaction in 11 out of the 16 models. Quantified Authenticity is measured as the consistency between self-reported personality and two other sources of personality data: language and Likes, respectively, (indicated in red and blue color). Quantified Authenticity is defined using four distance metrics, respectively: Manhattan, Euclidean, correlation, and cosine similarity (indicated with a letter in the dots). Models with and without control variables are indicated with dashed and solid line, respectively.

In exploratory analyses, we considered whether authenticity might benefit individuals of different personalities differentially. In order to examine this, we regressed Life Satisfaction on the interactions between Quantified Authenticity and each of the five personality traits (e.g., Quantified Authenticity × Extraversion). The results of these interaction analyses did not provide reliable evidence for the proposition that individuals with socially desirable profiles (i.e., high openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and low neuroticism) benefit from authentic self-expression more than individuals with less socially desirable profiles (see Table 1 , Model 3). While the interactions of the five personality traits with Quantified Authenticity reached significance for some traits and measures, the results were not consistent across both observable sources of self-expression (Likes-based and Language-based). Consequently, we did not find reliable evidence that having a socially desirable personality profile boosts the effect of authenticity on well-being. Instead, individuals reported increased Life Satisfaction when they presented authentic self-expression, regardless of their personality profile.

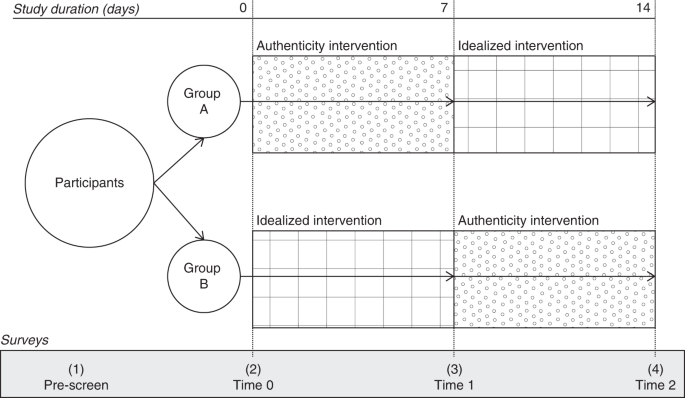

The findings of Study 1 provide evidence for the link between authenticity on social media and well-being in a setting of high external validity. However, given the correlational nature of the study, we cannot make any claims about the causality of the effects. While we hypothesize that expressing oneself authentically on social media results in higher levels of well-being, it is also plausible that individuals who experience higher levels of well-being are more likely to express themselves authentically on social media. To provide evidence for the directionality of authenticity on well-being, we conducted a pre-registered, longitudinal experiment in Study 2 (see Fig. 2 for an illustration of the experimental design).

Figure 2 presents the longitudinal experimental study design for Study 2 with key timepoints, interventions, and surveys.

Experimental manipulation of authentic self-expression on well-being

We recruited 90 students and social media users at a Northeastern University to participate in a 2-week study ( M age = 22.98, SD age = 4.17, 72.22% female). The sample size deviates from our pre-registered sample size of 200. The reason for this is that the behavioral research lab of the university was shut down after the first wave of data collection due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

All participants completed two intervention stages during which they were asked to post on their social media profiles in a way that was: (1) authentic for 7 days and (2) self-idealized for 7 days. The order in which participants completed the two interventions was randomly assigned. This experimental set-up allowed us to study the effects of authentic versus idealized self-expression on social media in between-person (week 1) and within-person analyses (comparison between week 1 and week 2). All analyses were pre-registered prior to data collection 37 . Given the reduced sample size, the effects reported in this paper are all as expected in effect size, but only partially reached significance at the conventional alpha = 0.05 level. Consequently, we also consider effects that reach significance at alpha = 0.10 as marginally significant.

All participants completed a personality pre-screen (IPIP) 38 prior to beginning the study, and received personalized feedback report at the beginning of the treatment period (t0). Both the authentic and self-idealized interventions (see Methods for details) asked participants to reflect on that feedback report and identify specific ways in which they could alter their self-expression on social media to align their posts more closely with their actual personality profile (authentic intervention) or to align their posts more closely with how they wanted to be seen by others (see Supplementary Information for treatment text and examples of responses). The operationalization of the treatment follows our conceptualization of Quantified Authenticity in Study 1 in that it does not prescribe the direction of personality change (e.g. towards higher levels of extraversion). Instead, this design leaves it up to participants what posting in a more desirable way means in relation to their current profile.

Participants self-reported their subjective well-being as Life Satisfaction 39 , a single-item mood measure, and positive and negative affect 40 a week after the first intervention (t1), and a week after the second intervention (t2). This design allowed us to examine the causal nature of posting for a week in which participants posted authentically (“authentic, real, or true”), compared to a week in which they posted in a self-idealized way (“ideal, popular or pleasing to others”). Specifically, we hypothesized that individuals who post more authentically over the course of a week would self-report greater subjective well-being at the end of that week, both at the between and within-person level.

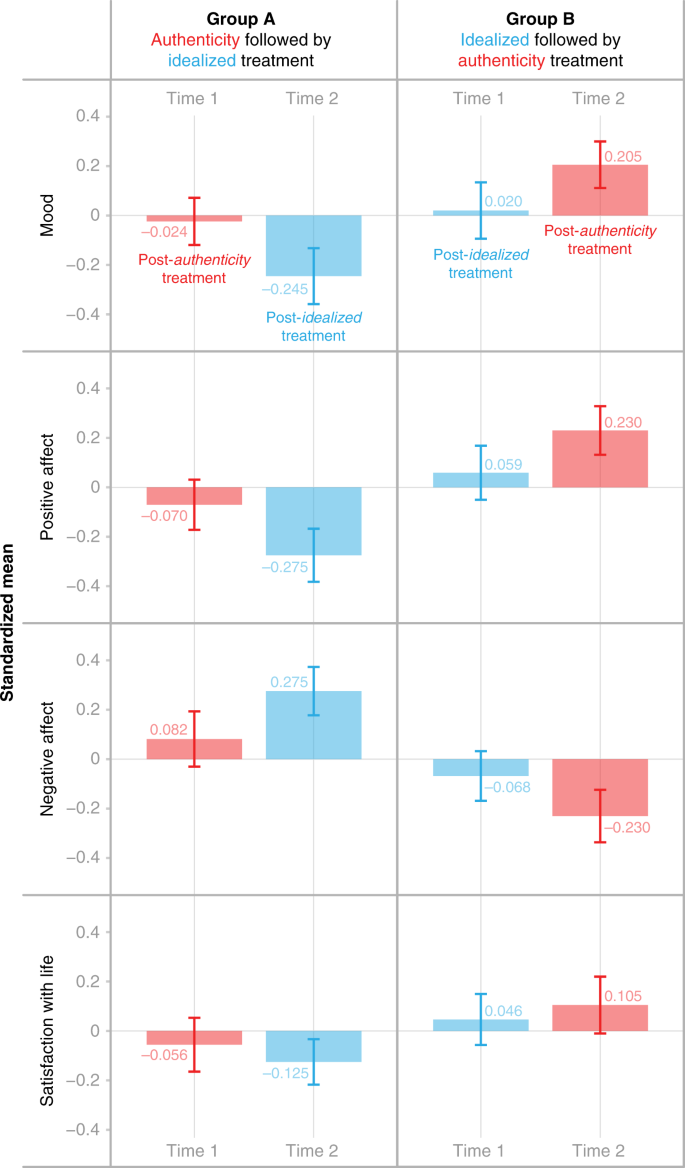

We examined the effect of authentic versus self-idealized expression at the between person level at t1 (see t1 in Fig. 3 ) using independent t -tests. Contrary to our expectations, we did not find any significant differences between the two conditions for any of the well-being indicators. This suggests that individuals in the authentic vs. self-idealized conditions did not differ from one another in their level of well-being after the first week of the study. However, when examining the effect within subjects using dependent t -tests we found that participants reported significantly higher levels of well-being after the week in which they posted authentically as compared to the week in which they posted in a self-idealized way. Specifically, the well-being scores in the authentic week were found to be significantly higher than in the self-idealized week for mood (mean difference = 0.19 [0.003, 0.374], t = 2.02, d = 0.43, p = 0.046) and for positive affect (mean difference = 0.17 [0.012, 0.318], t = 2.14, d = 0.45, p = 0.035), and marginally significant for negative affect (mean difference = −0.20 [−0.419, 0.016], t = −1.84, d = 0.39, p = 0.069). There was no significant effect on Life Satisfaction (mean difference = 0.09 [−0.096, 0.274], t = 0.96, d = 0.20, p = 0.342).

The bar chars illustrate the standardized mean of well-being indicators (mood, positive affect, negative affect, and Life Satisfaction) across two study time points by condition. The red bars indicate scores for the weeks in which participants were asked to post authentically, and the blue bars scores for the weeks in which they were asked to post in a self-idealized way. Error bars represent standard errors. The left-side panel presents Group A who received the authenticity treatment followed by the idealized treatment. The right-side panel presents Group B who received the idealized treatment followed by the authenticity treatment. This experiment was conducted once with independent samples in each group.