Argumentative Essay Quiz

Students also viewed

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Download this Handout PDF

Introduction

You’ve written a full draft of an argumentative paper. You’ve figured out what you’re generally saying and have put together one way to say it. But you’re not done. The best writing is revised writing, and you want to re–view, re–see, re–consider your argument to make sure that it’s as strong as possible. You’ll come back to smaller issues later (e.g., Is your language compelling? Are your paragraphs clearly and seamlessly connected? Are any of your sentences confusing?). But before you get into the details of phrases and punctuation, you need to focus on making sure your argument is as strong and persuasive as it can be. This page provides you with eight specific strategies for how to take on the important challenge of revising an argument.

- Give yourself time.

- Outline your argumentative claims and evidence.

- Analyze your argument’s assumptions.

- Revise with your audience in mind.

- Be your own most critical reader.

- Look for dissonance.

- Try “provocative revision.”

- Ask others to look critically at your argument.

1. Give yourself time.

The best way to begin re–seeing your argument is first to stop seeing it. Set your paper aside for a weekend, a day, or even a couple of hours. Of course, this will require you to have started your writing process well before your paper is due. But giving yourself this time allows you to refresh your perspective and separate yourself from your initial ideas and organization. When you return to your paper, try to approach your argument as a tough, critical reader. Reread it carefully. Maybe even read it out loud to hear it in a fresh way. Let the distance you created inform how you now see the paper differently.

2. Outline your argumentative claims and evidence.

This strategy combines the structure of a reverse outline with elements of argument that philosopher Stephen Toulmin detailed in his influential book The Uses of Argument . As you’re rereading your work, have a blank piece of paper or a new document next to you and write out:

- Your main claim (your thesis statement).

- Your sub–claims (the smaller claims that contribute to the larger claim).

- All the evidence you use to back up each of your claims.

Detailing these core elements of your argument helps you see its basic structure and assess whether or not your argument is convincing. This will also help you consider whether the most crucial elements of the argument are supported by the evidence and if they are logically sequenced to build upon each other.

In what follows we’ve provided a full example of what this kind of outline can look like. In this example, we’ve broken down the key argumentative claims and kinds of supporting evidence that Derek Thompson develops in his July/August 2015 Atlantic feature “ A World Without Work. ” This is a provocative and fascinating article, and we highly recommend it.

Charted Argumentative Claims and Evidence “ A World Without Work ” by Derek Thompson ( The Atlantic , July/August 2015) Main claim : Machines are making workers obsolete, and while this has the potential to disrupt and seriously damage American society, if handled strategically through governmental guidance, it also has the potential of helping us to live more communal, creative, and empathetic lives. Sub–claim : The disappearance of work would radically change the United States. Evidence: personal experience and observation Sub–claim : This is because work functions as something of an unofficial religion to Americans. Sub–claim : Technology has always guided the U.S. labor force. Evidence: historical examples Sub–claim: But now technology may be taking over our jobs. Sub–claim : However, the possibility that technology will take over our jobs isn’t anything new, nor is the fear that this possibility generates. Evidence: historical examples Sub–claim : So far, that fear hasn’t been justified, but it may now be because: 1. Businesses don’t require people to work like they used to. Evidence: statistics 2. More and more men and youths are unemployed. Evidence: statistics 3. Computer technology is advancing in majorly sophisticated ways. Evidence: historical examples and expert opinions Counter–argument: But technology has been radically advancing for 300 years and people aren’t out of work yet. Refutation: The same was once said about the horse. It was a key economic player; technology was built around it until technology began to surpass it. This parallels what will happen with retail workers, cashiers, food service employees, and office clerks. Evidence:: an academic study Counter–argument: But technology creates jobs too. Refutation: Yes, but not as quickly as it takes them away. Evidence: statistics Sub–claim : There are three overlapping visions of what the world might look like without work: 1. Consumption —People will not work and instead devote their freedom to leisure. Sub–claim : People don’t like their jobs. Evidence: polling data Sub–claim : But they need them. Evidence: expert insight Sub–claim : People might be happier if they didn’t have to work. Evidence: expert insight Counter–argument: But unemployed people don’t tend to be socially productive. Evidence: survey data Sub–claim : Americans feel guilty if they aren’t working. Evidence: statistics and academic studies Sub–claim : Future leisure activities may be nourishing enough to stave off this guilt. 2. Communal creativity —People will not work and will build productive, artistic, engaging communities outside the workplace. Sub–claim: This could be a good alternative to work. Evidence: personal experience and observation 3. Contingency —People will not work one big job like they used to and so will fight to regain their sense of productivity by piecing together small jobs. Evidence: personal experience and observation. Sub–claim : The internet facilitates gig work culture. Evidence: examples of internet-facilitated gig employment Sub–claim : No matter the form the labor force decline takes, it would require government support/intervention in regards to the issues of taxes and income distribution. Sub–claim : Productive things governments could do: • Local governments should create more and more ambitious community centers to respond to unemployment’s loneliness and its diminishment of community pride. • Government should create more small business incubators. Evidence: This worked in Youngstown. • Governments should encourage job sharing. Evidence: This worked for Germany. Counter–argument: Some jobs can’t be shared, and job sharing doesn’t fix the problem in the long term. Given this counter argument: • Governments should heavily tax the owners of capital and cut checks to all adults. Counter–argument: The capital owners would push against this, and this wouldn’t provide an alternative to the social function work plays. Refutation: Government should pay people to do something instead of nothing via an online job–posting board open up to governments, NGOs, and the like. • Governments should incentivize school by paying people to study. Sub–claim : There is a difference between jobs, careers, and calling, and a fulfilled life is lived in pursuit of a calling. Evidence: personal experience and observations

Some of the possible, revision-informing questions that this kind of outline can raise are:

- Are all the claims thoroughly supported by evidence?

- What kinds of evidence are used across the whole argument? Is the nature of the evidence appropriate given your context, purpose, and audience?

- How are the sub–claims related to each other? How do they build off of each other and work together to logically further the larger claim?

- Do any of your claims need to be qualified in order to be made more precise?

- Where and how are counter–arguments raised? Are they fully and fairly addressed?

For more information about the Toulmin Method, we recommend John Ramage, John Bean, and June Johnson’s book Written Arguments: A Rhetoric with Readings.

3. Analyze your argument’s assumptions.

In building arguments we make assumptions either explicitly or implicitly that connect our evidence to our claims. For example, in “A World Without Work,” as Thompson makes claims about the way technology will change the future of work, he is assuming that computer technology will keep advancing in major and surprising ways. This assumption helps him connect the evidence he provides about technology’s historical precedents to his claims about the future of work. Many of us would agree that it is reasonable to assume that technological advancement will continue, but it’s still important to recognize this as an assumption underlying his argument.

To identify your assumptions, return to the claims and evidence that you outlined in response to recommendation #2. Ask yourself, “What assumptions am I making about this piece of evidence in order to connect this evidence to this claim?” Write down those assumptions, and then ask yourself, “Are these assumptions reasonable? Are they acknowledged in my argument? If not, do they need to be?”

Often you will not overtly acknowledge your assumptions, and that can be fine. But especially if your readers don’t share certain beliefs, values, or knowledge, you can’t guarantee that they will just go along with the assumptions you make. In these situations, it can be valuable to clearly account for some of your assumptions within your paper and maybe even rationalize them by providing additional evidence. For example, if Thompson were writing his article for an audience skeptical that technology will continue advancing, he might choose to identify openly why he is convinced that humanity’s progression towards more complex innovation won’t stop.

4. Revise with your audience in mind.

We touched on this in the previous recommendation, but it’s important enough to expand on it further. Just as you should think about what your readers know, believe, and value as you consider the kinds of assumptions you make in your argument, you should also think about your audience in relationship to the kind of evidence you use. Given who will read your paper, what kind of argumentative support will they find to be the most persuasive? Are these readers who are compelled by numbers and data? Would they be interested by a personal narrative? Would they expect you to draw from certain key scholars in their field or avoid popular press sources or only look to scholarship that has been published in the past ten years? Return to your argument and think about how your readers might respond to it and its supporting evidence.

5. Be your own most critical reader.

Sometimes writing handbooks call this being the devil’s advocate. It is about intentionally pushing against your own ideas. Reread your draft while embracing a skeptical attitude. Ask questions like, “Is that really true?” and, “Where’s the proof?” Be as hard on your argument as you can be, and then let your criticisms inform what you need to expand on, clarify, and eliminate.

This kind of reading can also help you think about how you might incorporate or strengthen a counter–argument. By focusing on possible criticisms to your argument, you might encounter some that are particularly compelling that you’ll need to include in your paper. Sometimes the best way to revise with criticism in mind is to face that criticism head on, fairly explain what it is and why it’s important to consider, and then rationalize why your argument still holds even in light of this other perspective.

6. Look for dissonance.

In her influential 1980 article about how expert and novice writers revise differently, writing studies scholar Nancy Sommers claims that “at the heart of revision is the process by which writers recognize and resolve the dissonance they sense in their writing” (385). In this case, dissonance can be understood as the tension that exists between what you want your text to be, do, or sound like and what is actually on the page. One strategy for re–seeing your argument is to seek out the places where you feel dissonance within your argument—that is, substantive differences between what, in your mind, you want to be arguing, and what is actually in your draft.

A key to strengthening a paper through considering dissonance is to look critically—really critically—at your draft. Read through your paper with an eye towards content, assertions, or logical leaps that you feel uncertain about, that make you squirm a little bit, or that just don’t line up as nicely as you’d like. Some possible sources of dissonance might include:

- logical steps that are missing

- questions a skeptical reader might raise that are left unanswered

- examples that don’t actually connect to what you’re arguing

- pieces of evidence that contradict each other

- sources you read but aren’t mentioning because they disagree with you

Once you’ve identified dissonance within your paper, you have to decide what to do with it. Sometimes it’s tempting to take the easy way out and just delete the idea, claim, or section that is generating this sense of dissonance—to remove what seems to be causing the trouble. But don’t limit yourself to what is easy. Perhaps you need to add material or qualify something to make your argumentative claim more nuanced or more contextualized.

Even if the dissonance isn’t easily resolved, it’s still important to recognize. In fact, sometimes you can factor that recognition into how you revise; maybe your revision can involve considering how certain concepts or ideas don’t easily fit but are still important in some way. Maybe your revision can involve openly acknowledging and justifying the dissonance.

Sommers claims that whether expert writers are substituting, adding, deleting, or reordering material in response to dissonance, what they are really doing is locating and creating new meaning. Let your recognition of dissonance within your argument lead you through a process of discovery.

7. Try “provocative revision.”

Composition and writing center scholar Toby Fulwiler wrote in 1992 about the benefits of what he calls “provocative revision.” He says this kind of revision can take four forms. As you think about revising your argument, consider adopting one of these four strategies.

a. Limiting

As Fulwiler writes, “Generalization is death to good writing. Limiting is the cure for generality” (191). Generalization often takes the form of sweeping introduction statements (e.g., “Since the beginning of time, development has struggled against destruction.”), but arguments can be too general as well. Look back at your paper and ask yourself, “Is my argument ever not grounded in specifics? Is my evidence connected to a particular time, place, community, and circumstance?” If your claims are too broad, you may need to limit your scope and zoom in to the particular.

Inserting new content is a particularly common revision strategy. But when your focus is on revising an argument, make sure your addition of another source, another example, a more detailed description, or a closer analysis is in direct service to strengthening the argument. Adding material may be one way to respond to dissonance. It also can be useful for offering clarifications or for making previously implicit assumptions explicit. But adding isn’t just a matter of dropping new content into a paragraph. Adding something new in one place will probably influence other parts of the paper, so be prepared to make other additions to seamlessly weave together your new ideas.

c. Switching

For Fulwiler, switching is about radically altering the voice or tone of a text—changing from the first–person perspective to a third–person perspective or switching from an earnest appeal to a sarcastic critique. When it comes to revising your argument, it might not make sense to make any of these switches, but imaging what your argument might sound like coming from a very different voice might be generative. For example, how would Thompson’s “A World Without Work,” be altered if it was written from the voice and perspective of an unemployed steel mill worker or someone running for public office in Ohio or a mechanical robotics engineer? Re–visioning how your argument might come across if the primary voice, tone, and perspective was switched might help you think about how someone disinclined to agree with your ideas might approach your text and open additional avenues for revision.

d. Transforming

According to Fulwiler, transformation is about altering the genre and/or modality of a text—revising an expository essay into a letter to the editor, turning a persuasive research paper into a ballad. If you’re writing in response to a specific assignment, you may not have the chance to transform your argument in this way. But, as with switching, even reflecting on the possibilities of a genre or modality transformation can be useful in helping you think differently about your argument. If Thompson has been writing a commencement address instead of an article, how would “A World Without Work” need to change? How would he need to alter his focus and approach if it was a policy paper or a short documentary? Imagining your argument in a completely different context can help you to rethink how you are presenting your argument and engaging with your audience.

8. Ask others to look critically at your argument.

Sometimes the best thing you can do to figure out how your argument could improve is to get a second opinion. Of course, if you are a currently enrolled student at UW–Madison, you are welcome to make an appointment to talk with a tutor at our main center or stop by one of our satellite locations. But you have other ways to access quality feedback from other readers. You may want to ask someone else in your class, a roommate, or a friend to read through your paper with an eye towards how the argument could be improved. Be sure to provide your reader with specific questions to guide his or her attention towards specific parts of your argument (e.g., “How convincing do you find the connection I make between the claims on page 3 and the evidence on page 4?” “What would clarify further the causal relationship I’m suggesting between the first and second sub-argument?”). Be ready to listen graciously and critically to any recommendations these readers provide.

Works Cited

Fulwiler, Toby. “Provocative Revision.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 12, no. 2, 1992, pp. 190-204.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. Writing Arguments: A Rhetoric with Readings, 8th ed., Longman, 2010.

Sommers, Nancy. “Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 31, no. 4, 1980, pp. 378-88.

Thompson, Derek. “A World Without Work.” The Atlantic, July/August 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/07/world-without-work/395294/. Accessed 11 July 2017.

Toulmin, Stephen. The Uses of Argument. Updated ed., Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Developing a Thesis Statement

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Reviewing and Revising an Argument

Finishing a draft of your argument is an important milestone, but it's not the last step. Most arguments, especially research-based arguments, require careful revision to be fully effective. As you review and revise your draft, you might discover yourself reconsidering your audience, and then revising your focus. You might then reconsider your evidence and revising your claim. Reviewing and revising almost never occurs in the same manner twice. Be prepared to circle back several times through the choices below as you prepare your final argument.

Reviewing Your Position

One of the most common student remarks in argument drafting workshops is: "Now that I've written the whole paper, my position, or claim has changed." Be sure to take the time to review and revise your position statement so that it reflects the exact claim you support in your argument.

The Structure of Your Claim

After you've drafted your argument, you'll know if you're relying on cause/effect, "because" statements, or pro/con strategy. Make sure that the structure of your claim reflects the overall structure of your argument. For example, a first draft claim--"Fraternity hazing has serious negative effects on everyone involved"--can be revised to reflect the cause/effect reasoning in the rest of the argument-="because hazing causes psychological trauma to victims and perpetrators, fraternity hazing is much more serious than an initiation prank."

Word Choice in Your Claim

Quite often an early draft of a claim makes a broader or more general point than an argument can actually support or prove. As you revise, consider where you might limit your claim. Narrow the cases your claim applies to or state more precisely who is affected by a problem or how a solution can be implemented. Challenging each word in a claim is a good way to be sure that you've stated your claim as narrowly and as precisely as possible. Look also for loaded words that might carry negative connotations. Be sure to consider their effect on your target audience.

Your Claim as a Roadmap

An audience uses the claim to help anticipate what will appear in the rest of the argument. You want to revise your claim so that it makes the most sense in light of the argument that follows. Note obvious exceptions to your position right in the claim itself so that the audience understands exactly to what the claim applies. Continue revising your claim as you continue revising your argument so that it continues to function as a clear roadmap for the benefit of your audience.

Reviewing Your Audience Analysis

Once you've got a working draft, literally re-view your argument through the eyes of the audience. Here are several strategies that can help:

Role Playing: Become the Audience

Put the argument aside and make up a list of questions your audience might ask about the issue. Try to role play the way you assume they might think. Enlist other people's help with this list. Then, return to the paper and see if these questions have been answered.

Profile the Audience

Write a quick audience profile:

- What does your audience believe to be true?

- What kinds of proof will they find most persuasive?

- What do they already think about the issue?

Then, look back at your draft to see if you've supplied the kind of evidence likely to persuade your audience and whether you've addressed what they already think. If not, consider replacing or adding further evidence and refuting positions you have not included.

Play Devil's Advocate

Read through your argument as if you don't believe a single word. Look at each reason and the pieces of evidence you present and list any objections that could be made. Then, look at your objections and judge which of these your audience might hold. Revise to counter those objections.

Peer Review

Ask a friend (or several) to read through your argument. Ideally, get at least one who does not hold the same views as you on the issue. Ask them to write down any questions they didn't get answered and any counter-arguments they might make.

Reviewing Your Evidence

Once you've got a working draft of your argument, you want to make sure that you have adequate support for all your claims. The best way to do this is to go through your argument, sentence by sentence, circling all the claims you have made. List them on a sheet of paper and ask whether it is a claim with which any member of your audience might disagree.

Under each claim, list what evidence you offer in its support. If none is offered, perhaps further research is in order: If only one piece is offered, judge whether it is authoritative enough to support the claim and whether it should be included at all.

Familiar Sources

When relying on sources with which the audience is familiar--an article, book, or study, for instance--providing a lot of detail in the content isn't always necessary. It's fair enough to make a simple generalization place a proper citation in parentheses or a footnote.

Similarly, if you are relying on multiple studies that make the same point, a single sentence might be used to summarize the point all the works share, followed by a citation listing numerous studies and articles. For example:

As numerous studies have shown, students tend to revise more when writing on a computer (Selfe; Hawisher and Selfe; Kiefer; Palmquist).

Note: This advice may not apply to course assignments. Many times teachers want to assess your understanding of the content. As a result, they will expect details. Check with your instructor about how much knowledge you are allowed to assume on the part of your audience.

Key Piece of Evidence

When relying on one key piece of evidence to make a point, you will want to provide a detailed summary placing it in the context of its source. The more the audience knows about this context, the more they are likely to be convinced of its validity and that it does indeed support the specific point you are trying to make.

Evidence from Original Field Research

When relying on evidence from original field research to support your point you should provide as much information as possible. Describe your methods, the data collected and finally, the findings and conclusions you draw from the study. Here's a sample outline:

- Introduction: presents either the issue to be examined or the position you are taking.

- Literature Review (optional): discusses previous work done on an issue and the reasons why it is insufficient to answer a question.

- Methods: describes research design and the methods involved.

- Findings: describes research results, even that which isn't relevant or conclusive.

- Conclusions: advocates for the position or claim using relevant portions of the data.

Original Field Research as One of Many Forms of Evidence

When original field research is only one of many forms of evidence, a brief description of the method and data relevant to the argument is sufficient. For instance, here's a sample paragraph:

Rather than learning for the sake of becoming a better person, grades encourage performance for the sake of a better GPA. The focus grading puts on performance undercuts learning opportunities when students choose courses according to what might be easiest rather than what they'd like to know more about. [Sub-point in a paper arguing that grades should be abolished in non-major courses.]

For example, [Summary of Published Study.] students polled at CSU in a College of Liberal Arts study cite the following reasons for choosing non-major courses:

Easy grading (80%) Low quantity of work (60%) What was available (40%) Personality of teacher (30%) Interested in the class (10%)

Similarly, in an interview I conducted with graduating seniors, only two of the 20 people I spoke with found their non-major courses valuable. [A description of field research methods and findings.] The other 18 reported that non-major courses were a waste of time for a variety of reasons:

I'm never going to do anything with them. I just took whatever wouldn't distract me from my major so I didn't work very hard in them, just studying enough to get an A on the test. Non-major courses are a joke. Everyone I know took the simplest, stupidest, 100-level courses needed to fulfill the requirements. I can't even remember the ones I took now. [Other relevant details from field research; note answers about taking courses with friends and other non-relevant answers are not summarized.]

Only a Small Part of Work is Relevant

When only a small part of someone else's work is relevant, such as a statistic or quote, it need only be summarized or quoted. However, it is important to inform your audience when that work, as a whole, does not support your point or isn't relevant. The best way to work with data or information from an outside source is to provide a short, context-setting summary of the entire piece and only the detail of what is relevant to your argument.

This summary can be as little as a phrase or clause. For instance:

Although Smythe is against multicultural education in general...

It can also be an entire sentence as:

In Back to the Basics Smythe argues for a common curriculum for all students. Some of his examples, however, can also support the exact opposite conclusion.

After such a context-setting phrase or sentence, you are free to summarize only those points you intend to use. For example:

Although a discussion of recycling forms only a small part of Harrison's argument about global warming, his statistics on recycling are directly relevant here. As Harrison reports, although 60% of American families recycle in some way, only 2% of that 60% recycle all of their recyclable waste.

Multiple Sources

When multiple sources support a single point in your argument, even though each differs contextually somewhat from the other, try synthesizing them into a single unit supportive of your common theme. Coming from a variety of sources the audience will be more likely to find the combined evidence more compelling and persuasive. Your argument will be stronger in the long run.

Tangential Evidence

When tangential evidence is relevant but not exactly on point, you must show its relation, or connection, to your claim. Either a logical appeal or arguing for a particular interpretation of the evidence might do the trick. On the other hand, it might be better to present an outright refutation.

In both cases, the best way to incorporate the evidence is to combine a summary with textual analysis. That is, provide a fair summary of the outside source and then present an analysis, interpretation, or refutation that makes your point.

Making a Logical Appeal Using Tangential Evidence

One of the primary reasons I am claiming the media mishandled the Ebonics issue is that they never asked the right language questions about bilingual education. [Author's point] That is, the media presented it as a dialect issue--teaching Non-Standard English--without examining the language implications of bilingual education. To propose a program of bilingual education, one must first demonstrate that there are two languages involved, Ebonics and English. The appropriateness of teaching both is a separate issue. Yet, the media failed to even consider whether Ebonics can be considered a viable language. [Logical extension of claim of mishandled media attention to the question of Ebonics as a language]

By linguistic definitions, a language can be said to exist when speakers of different dialects no longer understand one another. [Evidence is tangential to point about the media but now relevant through the logical appeal above] Long recognized as a dialect of English, Ebonics (or Black English Vernacular as it is more commonly called) has roots in African languages, Southern dialects, and has been shown to evolve with each new generation. Yet, no linguistic evidence has yet been presented that speakers of English cannot understand someone speaking Ebonics. Similarly, none has been presented to prove Ebonics is not a language. [Tangential evidence on media but relevant to reformed issue of language]

By referring to Ebonics as a language, the media assumed the Oakland School district's definition without any investigation. Further, they turned the issue into an argument about dialect-Standard English versus another form of English-even while discussing Ebonics as a language. Neither perspective is fair or objective: if the media wanted to present a bilingual education issue, they should have dealt with Ebonics as a language. If they wanted to present a dialect issue, they should have demonstrated why Ebonics should not be considered a language. [Logical appeal connects language issue back to point about media, i.e., why failure to look at language definition leads to unfair reporting on Ebonics issue.]

Favorably Interpreting Tangential Evidence

THESIS: Attention to multiculturalism in writing curricula is cursory and does not pay enough attention to linguistic diversity even though the research does give it lip service.

INTERPRETATION: [Part of a section on how seemingly multicultural pedagogies ignore linguistic diversity.] Many curricular proposals, admittedly, seem to pay attention to linguistic diversity. [Author's point] For example, in an article in College English, Tory Smith begins by arguing that current writing curriculums don't pay enough attention to linguistic diversity. To support his argument, he cites several studies showing that when a student's dialect or cultural perspective is not valued by school, the student tends to disassociate from school. Finally, he presents a proposal for making room for culturally diverse topics in the classroom through the use of newsletters, personal anecdotes, etc. [Summary of tangential evidence] Although the proposal seems to address his concerns, a closer examination reveals that Smith does not meet his own goals. That is, his specific proposals clearly allow for assignments with more cultural content but make no mention of the linguistic diversity he cites as central to a multicultural curriculum. For example... [Paper goes on to directly quote an assignment example and then discusses how linguistic diversity is ignored-analysis of textual evidence.]

Refuting Tangential Evidence

George Will's editorial in Newsweek states that the reason "Johnny Can't Write" is the misguided nature of English teachers who focus more on issues of multiculturalism, "political correctness," new theories of reading-such as deconstruction-and so on, than on the hard and fast rules for paragraph development, grammar, and sentence structure. [Summary of Will's main argument and the tangential evidence he used] Although Will interviews students and uses sample course descriptions to back up his opinion, he misses the main point: all the theories and approaches he decries as "fashionable" are actually proven to teach people to write more effectively than the traditional methods he favors. In short, he ignores the research that invalidates his position. [Textual analysis focused on flaws in Will's editorial]

Citation Information

Donna LeCourt, Kate Kiefer, and Peter Connor. (1994-2024). Reviewing and Revising an Argument. The WAC Clearinghouse. Colorado State University. Available at https://wac.colostate.edu/repository/writing/guides/.

Copyright Information

Copyright © 1994-2024 Colorado State University and/or this site's authors, developers, and contributors . Some material displayed on this site is used with permission.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

9.3: The Argumentative Essay

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 58378

- Lumen Learning

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Examine types of argumentative essays

Argumentative Essays

You may have heard it said that all writing is an argument of some kind. Even if you’re writing an informative essay, you still have the job of trying to convince your audience that the information is important. However, there are times you’ll be asked to write an essay that is specifically an argumentative piece.

An argumentative essay is one that makes a clear assertion or argument about some topic or issue. When you’re writing an argumentative essay, it’s important to remember that an academic argument is quite different from a regular, emotional argument. Note that sometimes students forget the academic aspect of an argumentative essay and write essays that are much too emotional for an academic audience. It’s important for you to choose a topic you feel passionately about (if you’re allowed to pick your topic), but you have to be sure you aren’t too emotionally attached to a topic. In an academic argument, you’ll have a lot more constraints you have to consider, and you’ll focus much more on logic and reasoning than emotions.

Argumentative essays are quite common in academic writing and are often an important part of writing in all disciplines. You may be asked to take a stand on a social issue in your introduction to writing course, but you could also be asked to take a stand on an issue related to health care in your nursing courses or make a case for solving a local environmental problem in your biology class. And, since argument is such a common essay assignment, it’s important to be aware of some basic elements of a good argumentative essay.

When your professor asks you to write an argumentative essay, you’ll often be given something specific to write about. For example, you may be asked to take a stand on an issue you have been discussing in class. Perhaps, in your education class, you would be asked to write about standardized testing in public schools. Or, in your literature class, you might be asked to argue the effects of protest literature on public policy in the United States.

However, there are times when you’ll be given a choice of topics. You might even be asked to write an argumentative essay on any topic related to your field of study or a topic you feel that is important personally.

Whatever the case, having some knowledge of some basic argumentative techniques or strategies will be helpful as you write. Below are some common types of arguments.

Causal Arguments

- In this type of argument, you argue that something has caused something else. For example, you might explore the causes of the decline of large mammals in the world’s ocean and make a case for your cause.

Evaluation Arguments

- In this type of argument, you make an argumentative evaluation of something as “good” or “bad,” but you need to establish the criteria for “good” or “bad.” For example, you might evaluate a children’s book for your education class, but you would need to establish clear criteria for your evaluation for your audience.

Proposal Arguments

- In this type of argument, you must propose a solution to a problem. First, you must establish a clear problem and then propose a specific solution to that problem. For example, you might argue for a proposal that would increase retention rates at your college.

Narrative Arguments

- In this type of argument, you make your case by telling a story with a clear point related to your argument. For example, you might write a narrative about your experiences with standardized testing in order to make a case for reform.

Rebuttal Arguments

- In a rebuttal argument, you build your case around refuting an idea or ideas that have come before. In other words, your starting point is to challenge the ideas of the past.

Definition Arguments

- In this type of argument, you use a definition as the starting point for making your case. For example, in a definition argument, you might argue that NCAA basketball players should be defined as professional players and, therefore, should be paid.

https://assessments.lumenlearning.co...essments/20277

Essay Examples

- Click here to read an argumentative essay on the consequences of fast fashion . Read it and look at the comments to recognize strategies and techniques the author uses to convey her ideas.

- In this example, you’ll see a sample argumentative paper from a psychology class submitted in APA format. Key parts of the argumentative structure have been noted for you in the sample.

Link to Learning

For more examples of types of argumentative essays, visit the Argumentative Purposes section of the Excelsior OWL .

Contributors and Attributions

- Argumentative Essay. Provided by : Excelsior OWL. Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/rhetorical-styles/argumentative-essay/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of a man with a heart and a brain. Authored by : Mohamed Hassan. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : pixabay.com/illustrations/decision-brain-heart-mind-4083469/. License : Other . License Terms : pixabay.com/service/terms/#license

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to revise an essay in 3 simple steps

How to Revise an Essay in 3 Simple Steps

Published on December 2, 2014 by Shane Bryson . Revised on December 8, 2023 by Shona McCombes.

Revising and editing an essay is a crucial step of the writing process . It often takes up at least as much time as producing the first draft, so make sure you leave enough time to revise thoroughly. Although you can save considerable time using our essay checker .

The most effective approach to revising an essay is to move from general to specific:

- Start by looking at the big picture: does your essay achieve its overall purpose, and does it proceed in a logical order?

- Next, dive into each paragraph: do all the sentences contribute to the point of the paragraph, and do all your points fit together smoothly?

- Finally, polish up the details: is your grammar on point, your punctuation perfect, and your meaning crystal clear?

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: look at the essay as a whole, step 2: dive into each paragraph, step 3: polish the language, other interesting articles.

There’s no sense in perfecting a sentence if the whole paragraph will later be cut, and there’s no sense in focusing on a paragraph if the whole section needs to be reworked.

For these reasons, work from general to specific: start by looking at the overall purpose and organization of your text, and don’t worry about the details for now.

Double-check your assignment sheet and any feedback you’ve been given to make sure you’ve addressed each point of instruction. In other words, confirm that the essay completes every task it needs to complete.

Then go back to your thesis statement . Does every paragraph in the essay have a clear purpose that advances your argument? If there are any sections that are irrelevant or whose connection to the thesis is uncertain, consider cutting them or revising to make your points clearer.

Organization

Next, check for logical organization . Consider the ordering of paragraphs and sections, and think about what type of information you give in them. Ask yourself :

- Do you define terms, theories and concepts before you use them?

- Do you give all the necessary background information before you go into details?

- Does the argument build up logically from one point to the next?

- Is each paragraph clearly related to what comes before it?

Ensure each paragraph has a clear topic sentence that sums up its point. Then, try copying and pasting these topic sentences into a new document in the order that they appear in the paper.

This allows you to see the ordering of the sections and paragraphs of your paper in a glance, giving you a sense of your entire paper all at once. You can also play with the ordering of these topic sentences to try alternative organizations.

If some topic sentences seem too similar, consider whether one of the paragraphs is redundant , or if its specific contribution needs to be clarified. If the connection between paragraphs is unclear, use transition sentences to strengthen your structure.

Finally, use your intuition. If a paragraph or section feels out of place to you, even if you can’t decide why, it probably is. Think about it for a while and try to get a second opinion. Work out the organizational issues as best you can before moving on to more specific writing issues.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Next, you want to make sure the content of each paragraph is as strong as it can be, ensuring that every sentence is relevant and necessary:

- Make sure each sentence helps support the topic sentence .

- Check for redundancies – if a sentence repeats something you’ve already said, cut it.

- Check for inconsistencies in content. Do any of your assertions seem to contradict one another? If so, resolve the disagreement and cut as necessary.

Once you’re happy with the overall shape and content of your essay, it’s time to focus on polishing it at a sentence level, making sure that you’ve expressed yourself clearly and fluently.

You’re now less concerned with what you say than with how you say it. Aim to simplify, condense, and clarify each sentence, making it as easy as possible for your reader to understand what you want to say.

- Try to avoid complex sentence construction – be as direct and straightforward as possible.

- If you have a lot of very long sentences, split some of them into shorter ones.

- If you have a lot of very short sentences that sound choppy, combine some of them using conjunctions or semicolons .

- Make sure you’ve used appropriate transition words to show the connections between different points.

- Cut every unnecessary word.

- Avoid any complex word where a simpler one will do.

- Look out for typos and grammatical mistakes.

If you lack confidence in your grammar, our essay editing service provides an extra pair of eyes.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bryson, S. (2023, December 08). How to Revise an Essay in 3 Simple Steps. Scribbr. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/revising/

Is this article helpful?

Shane Bryson

Shane finished his master's degree in English literature in 2013 and has been working as a writing tutor and editor since 2009. He began proofreading and editing essays with Scribbr in early summer, 2014.

What is your plagiarism score?

Revising & Editing

Revision strategies.

When you revise and are spending time thinking about how well your content works in your essay, there are some strategies to keep in mind that can help. First and foremost, during the revision process, you should seek outside feedback . It’s especially helpful if you can find someone to review your work who disagrees with your perspective. This can help you better understand the opposing view and can help you see where you may need to strengthen your argument.

If you’re in a writing class, chances are you’ll have some kind of peer review for your argument. It’s important to take advantage of any peer review you receive on your essay. Even if you don’t take all of the advice you receive in a peer review, having advice to consider is going to help you as a writer.

Finally, in addition to the outside feedback, there are some revision strategies that you can engage in on your own. Read your essay carefully and think about the lessons you have learned about logic, fallacies, and audience. For an example of the revision process, check out this first video on revising from the Research & Citations area of the OWL.

A post draft outline can also help you during the revision process. A post draft outline can help you quickly see where you went with your essay and can help you more easily see if you need to make broad changes to content or to organizations.

For more information on creating a post draft outline, you can view the Prezi linked here . (It will take you to the writing lab’s site where you can then click on the Prezi to run it.) Be sure the volume is turned up on your computer!

- Revision Strategies. Authored by : OWL Excelsior Writing Lab. Provided by : Excelsior College. Located at : http://owl.excelsior.edu/argument-and-critical-thinking/revising-your-argument/revising-your-argument-revision-strategies/ . Project : OWL Excelsior. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Customer Reviews

- Extended Essays

- IB Internal Assessment

- Theory of Knowledge

- Literature Review

- Dissertations

- Essay Writing

- Research Writing

- Assignment Help

- Capstone Projects

- College Application

- Online Class

How to Revise an Argumentative Essay: The Complete Guide

by Antony W

April 7, 2022

You’ve spent a lot of time working on your argumentative essay. Your argument’s title is on point, you have a strong introduction for the argument , with a powerful hook that easily grabs the reader’s attention, and an arguable thesis statement .

Throughout the body section, you’ve structured your assignment so that every paragraph addresses its own idea, beginning with a topic sentence and ending with a closing link that transition to the next consecutive paragraph.

Your essay even addresses the opposing point of views and ends with a very strong conclusion . Your essay has addressed the issue in the prompt, and you now feel confident enough to submit it for review.

However, there’s one more thing you need to do before you can have your instructor look at your paper. You have to revise the essay thoroughly. So in this guide, you’ll learn how to revise an argumentative essay to give it a more refined touch than what it already has.

How to Revise An Argumentative Essay

Take a break from writing.

While you can do everything in one sitting, it’s not always the best thing to do if you want to earn full marks.

Take a break from the essay as soon as you finish writing the conclusion. A 24 hour break isn’t bad, although you can relax for a couple of hours if you have a strict deadline to beat.

Taking a break has a benefit:

It gives you the opportunity to refresh your mind, which could yield some great ideas and arguments different from what you already have in your essay.

In the end, you come back to your paper as a critical thinker who’s ready to read the essay from the standpoint of a reader, not a writer.

When you come back to working on your paper, read the essay carefully word by word, this time from a reader’s perspective.

Use Revise Outline to Review Your Claims and Evidence

In reverse outlining, you take away all the supporting writing and leave your paper with the main ideas. The approach allows you to assess if your ideas features the logical sequence of points and it helps to determine the success of your paper.

Reverse outlining your argumentative essay allow you to:

- See if your paper meets its goals

- Find places to analyze or expand

- Look for gaps in your structure where readers may otherwise find your organization somehow weak

To reverse outline your argumentative essay, take a separate blank piece of paper and start organizing your thoughts.

- Write your main claim at the top, or simply the thesis statement, right at the top

- Follow this with all the sub claims that you made in your paper

- Write down all the evidences that you used to support each claim

Since reverse outlining allows you to detail the core elements of your arguments in the most basic form possible, it becomes easy to see whether your argument would be convincing without the supporting writing.

Again, you’re able to look at your evidence more critically to determine if they’re sufficient to support the most crucial elements in the essay.

This revision technique raises a few important questions that you can use to refine your argumentative essay:

- Does your argument provide sufficient evidence to support your claim?

- How well has the essay addressed the counterarguments presented?

- Do you need to qualify any of your claims to make it more precise?

Look Into the Assumptions of Your Arguments

As you write your argumentative essay , you’ll find yourself making implicit and explicit assumptions to connect your audience to your claims. Should this the case, you should read your argumentative essay to identify the assumptions you make about a piece of evidence. Then, ask yourself the following questions:

- Are the assumptions that I have made on a claim in my argumentative essay reasonable?

- Can my readers acknowledge the assumptions that I make in my argumentative writing?

- Should I leave the assumptions in my argumentative essay if my target audience doesn’t acknowledge them?

It’s uncertain if readers will openly recognize and share your assumptions, and especially if they don’t accept certain knowledge, value or beliefs.

So if you’ve explicitly or implicitly made assumptions in your work, account for them and, if possible, provide more evidence to validate these assumptions.

Revise Your Argumentative Essay with Your Audience in Mind

It’s important to think about your audience when revising your paper, and especially in relation to the evidence you use in your argumentative essay.

Since you already know who will be reading your paper anyway, you need to identify the kind of evidence that they’ll find more persuasive.

- Do they need numbers and statistics?

- Are they looking for evidence draw from certain scholars in the field you’re trying to explore?

- Or will the essay be more convincing if it included personal narratives?

It’s going to take some time to figure out how exactly your readers may respond to your arguments.

And that can go a long way to make it easy for you to include the right supporting evidence in your work.

Let Someone Else Read Your Argumentative Essay

Sometimes playing the devil’s advocate in an argumentative essay that you’ve written yourself can be somewhat hard.

Should that be the case, it’s best to find someone more objective to read your paper.

This kind of approach is helpful because it helps you think about how you may handle opposing point of views when they arise.

Quite too often, another objective reader will certainly embrace a more skeptical attitude and will help you identify gaps that can help you improve your writing.

In this situation, questions such as truth and the burden of proof will easily arise. Allowing them to be hard on your arguments can give you helpful criticism, which you can use to either expand, clarify, or remove an issue from your argument.

About the author

Antony W is a professional writer and coach at Help for Assessment. He spends countless hours every day researching and writing great content filled with expert advice on how to write engaging essays, research papers, and assignments.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.4 Revising and Editing

Learning objectives.

- Identify major areas of concern in the draft essay during revising and editing.

- Use peer reviews and editing checklists to assist revising and editing.

- Revise and edit the first draft of your essay and produce a final draft.

Revising and editing are the two tasks you undertake to significantly improve your essay. Both are very important elements of the writing process. You may think that a completed first draft means little improvement is needed. However, even experienced writers need to improve their drafts and rely on peers during revising and editing. You may know that athletes miss catches, fumble balls, or overshoot goals. Dancers forget steps, turn too slowly, or miss beats. For both athletes and dancers, the more they practice, the stronger their performance will become. Web designers seek better images, a more clever design, or a more appealing background for their web pages. Writing has the same capacity to profit from improvement and revision.

Understanding the Purpose of Revising and Editing

Revising and editing allow you to examine two important aspects of your writing separately, so that you can give each task your undivided attention.

- When you revise , you take a second look at your ideas. You might add, cut, move, or change information in order to make your ideas clearer, more accurate, more interesting, or more convincing.

- When you edit , you take a second look at how you expressed your ideas. You add or change words. You fix any problems in grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure. You improve your writing style. You make your essay into a polished, mature piece of writing, the end product of your best efforts.

How do you get the best out of your revisions and editing? Here are some strategies that writers have developed to look at their first drafts from a fresh perspective. Try them over the course of this semester; then keep using the ones that bring results.

- Take a break. You are proud of what you wrote, but you might be too close to it to make changes. Set aside your writing for a few hours or even a day until you can look at it objectively.

- Ask someone you trust for feedback and constructive criticism.

- Pretend you are one of your readers. Are you satisfied or dissatisfied? Why?

- Use the resources that your college provides. Find out where your school’s writing lab is located and ask about the assistance they provide online and in person.

Many people hear the words critic , critical , and criticism and pick up only negative vibes that provoke feelings that make them blush, grumble, or shout. However, as a writer and a thinker, you need to learn to be critical of yourself in a positive way and have high expectations for your work. You also need to train your eye and trust your ability to fix what needs fixing. For this, you need to teach yourself where to look.

Creating Unity and Coherence

Following your outline closely offers you a reasonable guarantee that your writing will stay on purpose and not drift away from the controlling idea. However, when writers are rushed, are tired, or cannot find the right words, their writing may become less than they want it to be. Their writing may no longer be clear and concise, and they may be adding information that is not needed to develop the main idea.

When a piece of writing has unity , all the ideas in each paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense. When the writing has coherence , the ideas flow smoothly. The wording clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and from paragraph to paragraph.

Reading your writing aloud will often help you find problems with unity and coherence. Listen for the clarity and flow of your ideas. Identify places where you find yourself confused, and write a note to yourself about possible fixes.

Creating Unity

Sometimes writers get caught up in the moment and cannot resist a good digression. Even though you might enjoy such detours when you chat with friends, unplanned digressions usually harm a piece of writing.

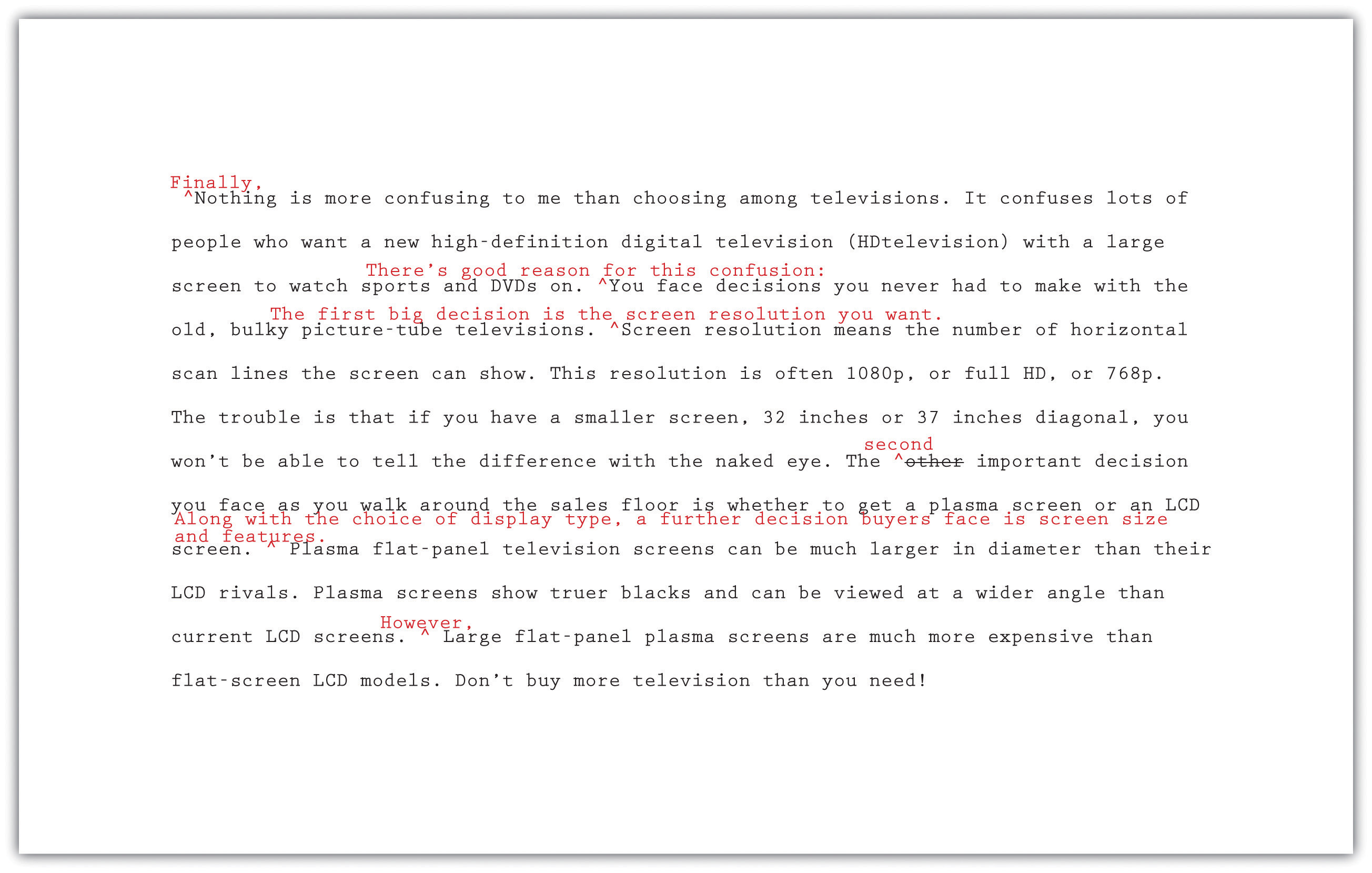

Mariah stayed close to her outline when she drafted the three body paragraphs of her essay she tentatively titled “Digital Technology: The Newest and the Best at What Price?” But a recent shopping trip for an HDTV upset her enough that she digressed from the main topic of her third paragraph and included comments about the sales staff at the electronics store she visited. When she revised her essay, she deleted the off-topic sentences that affected the unity of the paragraph.

Read the following paragraph twice, the first time without Mariah’s changes, and the second time with them.

Nothing is more confusing to me than choosing among televisions. It confuses lots of people who want a new high-definition digital television (HDTV) with a large screen to watch sports and DVDs on. You could listen to the guys in the electronics store, but word has it they know little more than you do. They want to sell what they have in stock, not what best fits your needs. You face decisions you never had to make with the old, bulky picture-tube televisions. Screen resolution means the number of horizontal scan lines the screen can show. This resolution is often 1080p, or full HD, or 768p. The trouble is that if you have a smaller screen, 32 inches or 37 inches diagonal, you won’t be able to tell the difference with the naked eye. The 1080p televisions cost more, though, so those are what the salespeople want you to buy. They get bigger commissions. The other important decision you face as you walk around the sales floor is whether to get a plasma screen or an LCD screen. Now here the salespeople may finally give you decent info. Plasma flat-panel television screens can be much larger in diameter than their LCD rivals. Plasma screens show truer blacks and can be viewed at a wider angle than current LCD screens. But be careful and tell the salesperson you have budget constraints. Large flat-panel plasma screens are much more expensive than flat-screen LCD models. Don’t let someone make you by more television than you need!

Answer the following two questions about Mariah’s paragraph:

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

- Now start to revise the first draft of the essay you wrote in Section 8 “Writing Your Own First Draft” . Reread it to find any statements that affect the unity of your writing. Decide how best to revise.

When you reread your writing to find revisions to make, look for each type of problem in a separate sweep. Read it straight through once to locate any problems with unity. Read it straight through a second time to find problems with coherence. You may follow this same practice during many stages of the writing process.

Writing at Work

Many companies hire copyeditors and proofreaders to help them produce the cleanest possible final drafts of large writing projects. Copyeditors are responsible for suggesting revisions and style changes; proofreaders check documents for any errors in capitalization, spelling, and punctuation that have crept in. Many times, these tasks are done on a freelance basis, with one freelancer working for a variety of clients.

Creating Coherence

Careful writers use transitions to clarify how the ideas in their sentences and paragraphs are related. These words and phrases help the writing flow smoothly. Adding transitions is not the only way to improve coherence, but they are often useful and give a mature feel to your essays. Table 8.3 “Common Transitional Words and Phrases” groups many common transitions according to their purpose.

Table 8.3 Common Transitional Words and Phrases

| after | before | later |

| afterward | before long | meanwhile |

| as soon as | finally | next |

| at first | first, second, third | soon |

| at last | in the first place | then |

| above | across | at the bottom |

| at the top | behind | below |

| beside | beyond | inside |

| near | next to | opposite |

| to the left, to the right, to the side | under | where |

| indeed | hence | in conclusion |

| in the final analysis | therefore | thus |

| consequently | furthermore | additionally |

| because | besides the fact | following this idea further |

| in addition | in the same way | moreover |

| looking further | considering…, it is clear that | |

| but | yet | however |

| nevertheless | on the contrary | on the other hand |

| above all | best | especially |

| in fact | more important | most important |

| most | worst | |

| finally | last | in conclusion |

| most of all | least of all | last of all |

| admittedly | at this point | certainly |

| granted | it is true | generally speaking |

| in general | in this situation | no doubt |

| no one denies | obviously | of course |

| to be sure | undoubtedly | unquestionably |

| for instance | for example | |

| first, second, third | generally, furthermore, finally | in the first place, also, last |

| in the first place, furthermore, finally | in the first place, likewise, lastly | |

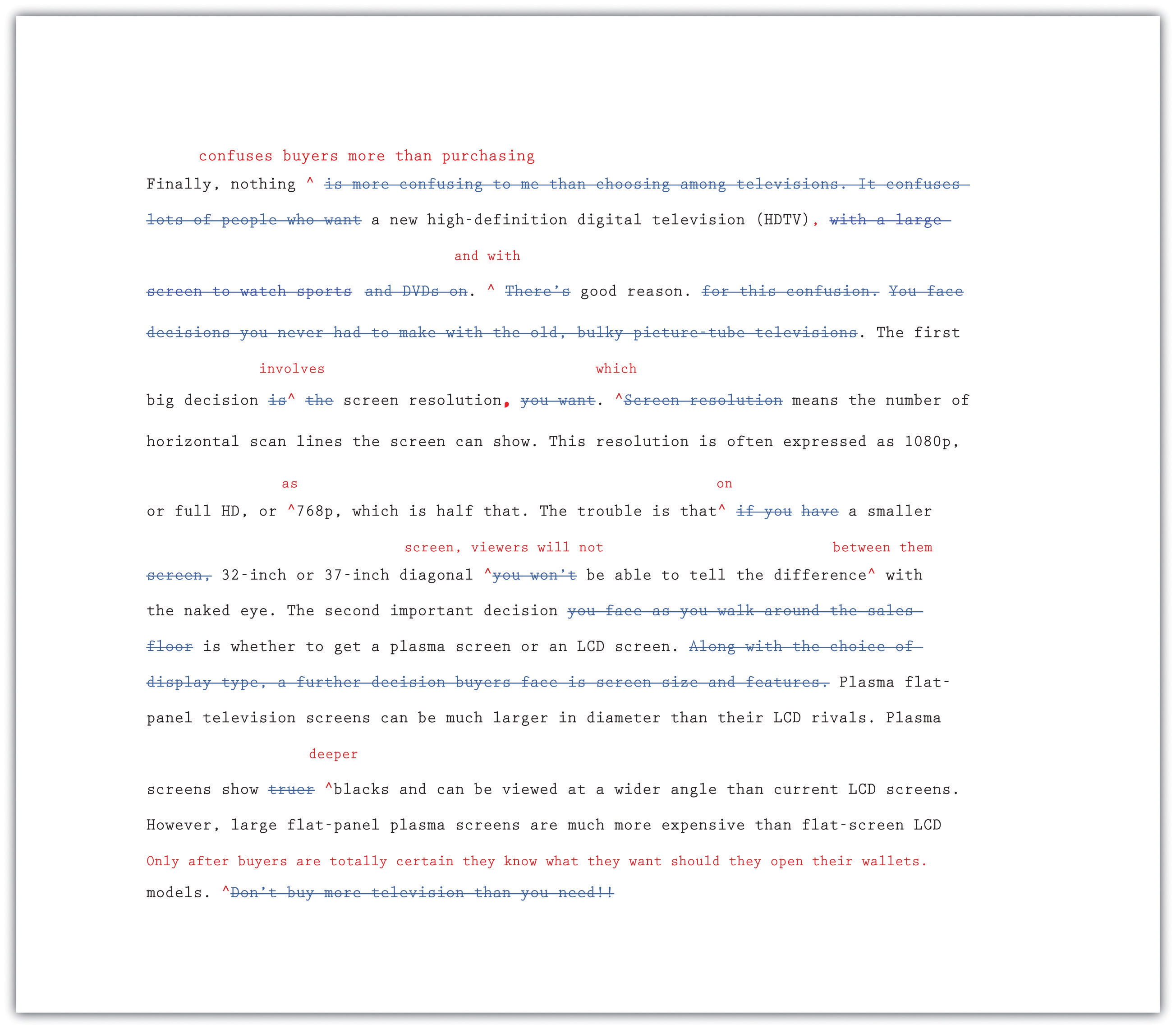

After Maria revised for unity, she next examined her paragraph about televisions to check for coherence. She looked for places where she needed to add a transition or perhaps reword the text to make the flow of ideas clear. In the version that follows, she has already deleted the sentences that were off topic.

Many writers make their revisions on a printed copy and then transfer them to the version on-screen. They conventionally use a small arrow called a caret (^) to show where to insert an addition or correction.

1. Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph.

2. Now return to the first draft of the essay you wrote in Section 8 “Writing Your Own First Draft” and revise it for coherence. Add transition words and phrases where they are needed, and make any other changes that are needed to improve the flow and connection between ideas.

Being Clear and Concise

Some writers are very methodical and painstaking when they write a first draft. Other writers unleash a lot of words in order to get out all that they feel they need to say. Do either of these composing styles match your style? Or is your composing style somewhere in between? No matter which description best fits you, the first draft of almost every piece of writing, no matter its author, can be made clearer and more concise.

If you have a tendency to write too much, you will need to look for unnecessary words. If you have a tendency to be vague or imprecise in your wording, you will need to find specific words to replace any overly general language.

Identifying Wordiness

Sometimes writers use too many words when fewer words will appeal more to their audience and better fit their purpose. Here are some common examples of wordiness to look for in your draft. Eliminating wordiness helps all readers, because it makes your ideas clear, direct, and straightforward.

Sentences that begin with There is or There are .

Wordy: There are two major experiments that the Biology Department sponsors.

Revised: The Biology Department sponsors two major experiments.

Sentences with unnecessary modifiers.

Wordy: Two extremely famous and well-known consumer advocates spoke eloquently in favor of the proposed important legislation.

Revised: Two well-known consumer advocates spoke in favor of the proposed legislation.

Sentences with deadwood phrases that add little to the meaning. Be judicious when you use phrases such as in terms of , with a mind to , on the subject of , as to whether or not , more or less , as far as…is concerned , and similar expressions. You can usually find a more straightforward way to state your point.

Wordy: As a world leader in the field of green technology, the company plans to focus its efforts in the area of geothermal energy.

A report as to whether or not to use geysers as an energy source is in the process of preparation.

Revised: As a world leader in green technology, the company plans to focus on geothermal energy.

A report about using geysers as an energy source is in preparation.

Sentences in the passive voice or with forms of the verb to be . Sentences with passive-voice verbs often create confusion, because the subject of the sentence does not perform an action. Sentences are clearer when the subject of the sentence performs the action and is followed by a strong verb. Use strong active-voice verbs in place of forms of to be , which can lead to wordiness. Avoid passive voice when you can.

Wordy: It might perhaps be said that using a GPS device is something that is a benefit to drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Revised: Using a GPS device benefits drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Sentences with constructions that can be shortened.

Wordy: The e-book reader, which is a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone.

My over-sixty uncle bought an e-book reader, and his wife bought an e-book reader, too.

Revised: The e-book reader, a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone.

My over-sixty uncle and his wife both bought e-book readers.

Now return once more to the first draft of the essay you have been revising. Check it for unnecessary words. Try making your sentences as concise as they can be.

Choosing Specific, Appropriate Words

Most college essays should be written in formal English suitable for an academic situation. Follow these principles to be sure that your word choice is appropriate. For more information about word choice, see Chapter 4 “Working with Words: Which Word Is Right?” .

- Avoid slang. Find alternatives to bummer , kewl , and rad .

- Avoid language that is overly casual. Write about “men and women” rather than “girls and guys” unless you are trying to create a specific effect. A formal tone calls for formal language.

- Avoid contractions. Use do not in place of don’t , I am in place of I’m , have not in place of haven’t , and so on. Contractions are considered casual speech.

- Avoid clichés. Overused expressions such as green with envy , face the music , better late than never , and similar expressions are empty of meaning and may not appeal to your audience.

- Be careful when you use words that sound alike but have different meanings. Some examples are allusion/illusion , complement/compliment , council/counsel , concurrent/consecutive , founder/flounder , and historic/historical . When in doubt, check a dictionary.

- Choose words with the connotations you want. Choosing a word for its connotations is as important in formal essay writing as it is in all kinds of writing. Compare the positive connotations of the word proud and the negative connotations of arrogant and conceited .

- Use specific words rather than overly general words. Find synonyms for thing , people , nice , good , bad , interesting , and other vague words. Or use specific details to make your exact meaning clear.

Now read the revisions Mariah made to make her third paragraph clearer and more concise. She has already incorporated the changes she made to improve unity and coherence.

1. Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph:

2. Now return once more to your essay in progress. Read carefully for problems with word choice. Be sure that your draft is written in formal language and that your word choice is specific and appropriate.

Completing a Peer Review

After working so closely with a piece of writing, writers often need to step back and ask for a more objective reader. What writers most need is feedback from readers who can respond only to the words on the page. When they are ready, writers show their drafts to someone they respect and who can give an honest response about its strengths and weaknesses.

You, too, can ask a peer to read your draft when it is ready. After evaluating the feedback and assessing what is most helpful, the reader’s feedback will help you when you revise your draft. This process is called peer review .

You can work with a partner in your class and identify specific ways to strengthen each other’s essays. Although you may be uncomfortable sharing your writing at first, remember that each writer is working toward the same goal: a final draft that fits the audience and the purpose. Maintaining a positive attitude when providing feedback will put you and your partner at ease. The box that follows provides a useful framework for the peer review session.

Questions for Peer Review

Title of essay: ____________________________________________

Date: ____________________________________________

Writer’s name: ____________________________________________

Peer reviewer’s name: _________________________________________

- This essay is about____________________________________________.

- Your main points in this essay are____________________________________________.

- What I most liked about this essay is____________________________________________.

These three points struck me as your strongest:

These places in your essay are not clear to me:

a. Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because__________________________________________

b. Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because ____________________________________________

c. Where: ____________________________________________

The one additional change you could make that would improve this essay significantly is ____________________________________________.

One of the reasons why word-processing programs build in a reviewing feature is that workgroups have become a common feature in many businesses. Writing is often collaborative, and the members of a workgroup and their supervisors often critique group members’ work and offer feedback that will lead to a better final product.

Exchange essays with a classmate and complete a peer review of each other’s draft in progress. Remember to give positive feedback and to be courteous and polite in your responses. Focus on providing one positive comment and one question for more information to the author.

Using Feedback Objectively

The purpose of peer feedback is to receive constructive criticism of your essay. Your peer reviewer is your first real audience, and you have the opportunity to learn what confuses and delights a reader so that you can improve your work before sharing the final draft with a wider audience (or your intended audience).

It may not be necessary to incorporate every recommendation your peer reviewer makes. However, if you start to observe a pattern in the responses you receive from peer reviewers, you might want to take that feedback into consideration in future assignments. For example, if you read consistent comments about a need for more research, then you may want to consider including more research in future assignments.

Using Feedback from Multiple Sources

You might get feedback from more than one reader as you share different stages of your revised draft. In this situation, you may receive feedback from readers who do not understand the assignment or who lack your involvement with and enthusiasm for it.

You need to evaluate the responses you receive according to two important criteria:

- Determine if the feedback supports the purpose of the assignment.

- Determine if the suggested revisions are appropriate to the audience.

Then, using these standards, accept or reject revision feedback.

Work with two partners. Go back to Note 8.81 “Exercise 4” in this lesson and compare your responses to Activity A, about Mariah’s paragraph, with your partners’. Recall Mariah’s purpose for writing and her audience. Then, working individually, list where you agree and where you disagree about revision needs.

Editing Your Draft