Speech Acts in Linguistics

Brooks Kraft LLC/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In linguistics , a speech act is an utterance defined in terms of a speaker's intention and the effect it has on a listener. Essentially, it is the action that the speaker hopes to provoke in his or her audience. Speech acts might be requests, warnings, promises, apologies, greetings, or any number of declarations. As you might imagine, speech acts are an important part of communication.

Speech-Act Theory

Speech-act theory is a subfield of pragmatics . This area of study is concerned with the ways in which words can be used not only to present information but also to carry out actions. It is used in linguistics, philosophy, psychology, legal and literary theories, and even the development of artificial intelligence.

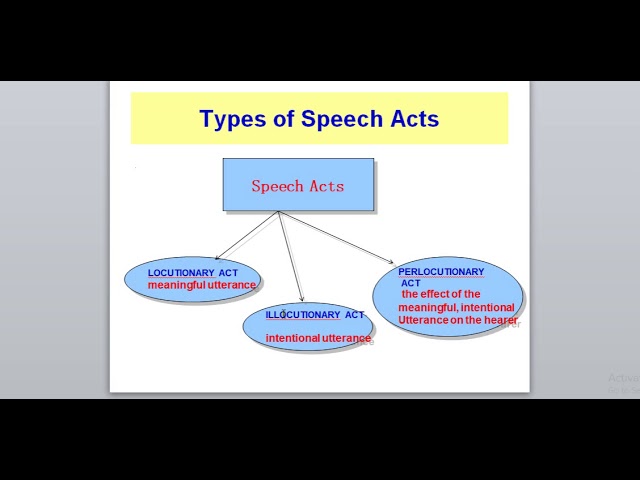

Speech-act theory was introduced in 1975 by Oxford philosopher J.L. Austin in "How to Do Things With Words" and further developed by American philosopher J.R. Searle. It considers three levels or components of utterances: locutionary acts (the making of a meaningful statement, saying something that a hearer understands), illocutionary acts (saying something with a purpose, such as to inform), and perlocutionary acts (saying something that causes someone to act). Illocutionary speech acts can also be broken down into different families, grouped together by their intent of usage.

Locutionary, Illocutionary, and Perlocutionary Acts

To determine which way a speech act is to be interpreted, one must first determine the type of act being performed. Locutionary acts are, according to Susana Nuccetelli and Gary Seay's "Philosophy of Language: The Central Topics," "the mere act of producing some linguistic sounds or marks with a certain meaning and reference." So this is merely an umbrella term, as illocutionary and perlocutionary acts can occur simultaneously when locution of a statement happens.

Illocutionary acts , then, carry a directive for the audience. It might be a promise, an order, an apology, or an expression of thanks—or merely an answer to a question, to inform the other person in the conversation. These express a certain attitude and carry with their statements a certain illocutionary force, which can be broken into families.

Perlocutionary acts , on the other hand, bring about a consequence to the audience. They have an effect on the hearer, in feelings, thoughts, or actions, for example, changing someone's mind. Unlike illocutionary acts, perlocutionary acts can project a sense of fear into the audience.

Take for instance the perlocutionary act of saying, "I will not be your friend." Here, the impending loss of friendship is an illocutionary act, while the effect of frightening the friend into compliance is a perlocutionary act.

Families of Speech Acts

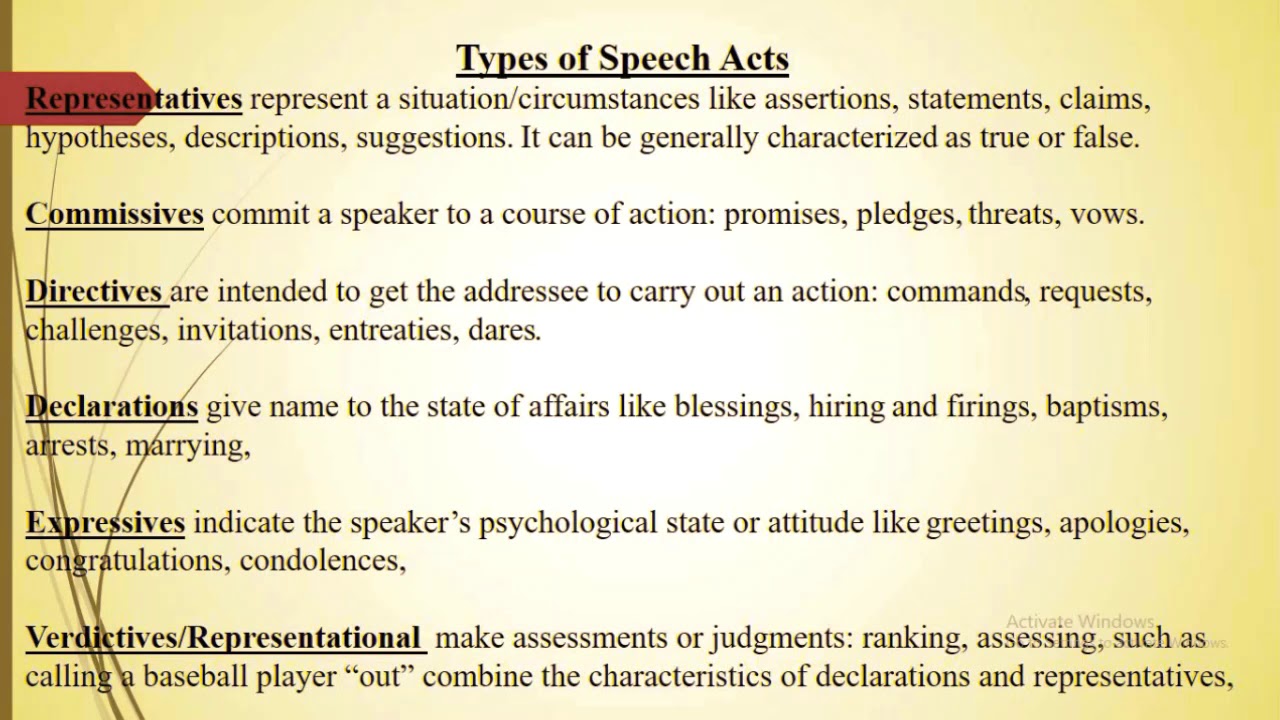

As mentioned, illocutionary acts can be categorized into common families of speech acts. These define the supposed intent of the speaker. Austin again uses "How to Do Things With Words" to argue his case for the five most common classes:

- Verdictives, which present a finding

- Exercitives, which exemplify power or influence

- Commissives, which consist of promising or committing to doing something

- Behabitives, which have to do with social behaviors and attitudes like apologizing and congratulating

- Expositives, which explain how our language interacts with itself

David Crystal, too, argues for these categories in "Dictionary of Linguistics." He lists several proposed categories, including " directives (speakers try to get their listeners to do something, e.g. begging, commanding, requesting), commissives (speakers commit themselves to a future course of action, e.g. promising, guaranteeing), expressives (speakers express their feelings, e.g. apologizing, welcoming, sympathizing), declarations (the speaker's utterance brings about a new external situation, e.g. christening, marrying, resigning)."

It is important to note that these are not the only categories of speech acts, and they are not perfect nor exclusive. Kirsten Malmkjaer points out in "Speech-Act Theory," "There are many marginal cases, and many instances of overlap, and a very large body of research exists as a result of people's efforts to arrive at more precise classifications."

Still, these five commonly accepted categories do a good job of describing the breadth of human expression, at least when it comes to illocutionary acts in speech theory.

Austin, J.L. "How to Do Things With Words." 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975.

Crystal, D. "Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics." 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2008.

Malmkjaer, K. "Speech -Act Theory." In "The Linguistics Encyclopedia," 3rd ed. New York, NY: Routledge, 2010.

Nuccetelli, Susana (Editor). "Philosophy of Language: The Central Topics." Gary Seay (Series Editor), Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, December 24, 2007.

- Illocutionary Act

- Locutionary Act Definition in Speech-Act Theory

- Speech Act Theory

- Perlocutionary Act Speech

- The Power of Indirectness in Speaking and Writing

- Illocutionary Force in Speech Theory

- Performative Verbs

- What "Literal Meaning" Really Means

- Suprasegmental Definition and Examples

- Definition and Examples of Sarcasm

- Linguistic Variation

- Pragmatics Gives Context to Language

- Rhetoric: Definitions and Observations

- AP English Exam: 101 Key Terms

- What Are Utterances in English (Speech)?

- An Introduction to Semantics

Oratory Club

Public Speaking Helpline

What are the Types of Speech Acts?

Speech acts can be categorized into three types: locutionary acts, illocutionary acts, and perlocutionary acts. In a locutionary act, words are used to make a statement or convey meaning.

Illocutionary acts involve the intention behind the speech, such as making a request or giving an order. Perlocutionary acts focus on the effect the speech has on the listener, like convincing or persuading them. Speech acts have different types, namely locutionary acts, illocutionary acts, and perlocutionary acts.

As the name suggests, locutionary acts involve the use of words to communicate meaning or make a statement. In contrast, illocutionary acts are centered around the intentions behind the speech, such as making a request or giving an order. Lastly, perlocutionary acts focus on the impact the speech has on the listener, such as influencing or persuading them in some way. Understanding these different types of speech acts is crucial for effective communication and interaction.

Credit: www.semanticscholar.org

Table of Contents

Assertive Speech Acts

When it comes to communication, we often use speech acts to convey our intentions and meanings. One such type of speech act is the assertive speech act. In this section, we will explore the definition, examples, and characteristics of assertive speech acts.

Definition And Examples

An assertive speech act, also known as a constative speech act, is used to state or convey factual information or beliefs. It aims to present an accurate representation of reality through statements that are true or false. Assertive speech acts can take various forms, including making statements, reporting facts, providing explanations, or expressing opinions.

Here are a few examples to illustrate assertive speech acts:

- Statement: “The sun rises in the east.”

- Fact Report: “According to the latest research, global warming is increasing.”

- Explanation: “Rainbows occur when sunlight is refracted and reflected by water droplets in the air.”

- Opinion: “In my opinion, smartphones have revolutionized the way we communicate.”

Characteristics

Assertive speech acts possess distinctive characteristics that set them apart from other types of speech acts:

- Truth-oriented: Assertive speech acts aim to convey information that is either true or false, reflecting objective reality.

- Factual in nature: These speech acts are centered around presenting facts, data, evidence, or personal beliefs.

- Verifiability: In most cases, assertive speech acts can be verified or proven through evidence, logical reasoning, scientific methods, or personal experiences.

- Intentional and deliberate: Speakers consciously intend to state or assert something, often with the goal of informing, persuading, or expressing their viewpoint.

- Subject to revision: Unlike certain speech acts, such as directives or commissives, assertive speech acts are open to revision or change when new evidence or information emerges.

Understanding assertive speech acts and their characteristics is crucial for effective communication. It enables us to convey information accurately, express our beliefs and opinions, and engage in meaningful discussions.

Credit: www.youtube.com

Directive Speech Acts

Directive speech acts are a type of speech act in which the speaker intends to get the listener to do something or to influence the listener’s behavior in some way. These speech acts are typically characterized by imperatives, requests, or suggestions. In this section, we will explore the definition and examples of directive speech acts as well as their important characteristics.

A directive speech act is an utterance that is intended to prompt the listener to take a specific action. It involves making a request or giving an instruction to the listener. These speech acts are designed to elicit a response or to bring about a change in the listener’s behavior. They can be classified into various categories, including commands, requests, suggestions, and warnings.

Let’s take a look at some examples of directive speech acts:

- A mother telling her child, “Please clean your room.”

- A teacher instructing the students, “Open your textbooks to page 25.”

- A boss telling an employee, “Finish the report by the end of the day.”

- A friend suggesting, “Why don’t we go out for dinner tonight?”

- A sign warning, “Do not enter without permission.”

Directive speech acts possess a set of characteristics that distinguish them from other types of speech acts. Understanding these characteristics can help us comprehend the intention behind a speaker’s utterance and the impact it may have on the listener. Some key characteristics of directive speech acts are:

- Imperative Forms: Directive speech acts often employ imperative verb forms, such as “clean,” “open,” “finish,” or “do not enter.” These forms convey a sense of command or instruction to the listener.

- Assertiveness: Directive speech acts are typically more assertive in nature than other types of speech acts. They are direct and straightforward, aiming to influence the listener’s behavior without room for ambiguity.

- Intentional: Directive speech acts are purposeful; the speaker intends to bring about a specific action from the listener. The intention behind the speech act is to influence the listener’s behavior or to achieve a desired outcome.

- Power Dynamics: Directive speech acts often involve a power dynamic between the speaker and the listener. For example, a boss giving instructions to an employee or a teacher instructing students. This power dynamic can shape the effectiveness of the directive speech act.

- Context-Dependent: The interpretation of directive speech acts heavily relies on the context in which they occur. The same utterance can have different implications depending on factors like the relationship between the speaker and listener, cultural norms, and the specific situation.

Understanding the characteristics of directive speech acts can help us analyze the underlying intentions and implications of a speaker’s request or instruction. It allows for a deeper understanding of the power dynamics and influence within a given interaction.

Commissive Speech Acts

In the realm of speech acts, commissives are a particularly interesting type. Commissive speech acts are rooted in the realm of promises, commitments, and pledges. When someone makes a commissive statement, they are expressing their intention to carry out a specific action or fulfill a certain obligation in the future. This category of speech acts can have a profound impact on interpersonal relationships and communication dynamics, as they involve making explicit commitments or promises.

A commissive speech act is a type of utterance where the speaker commits themselves to carrying out a future action or fulfilling a certain obligation. It is a declaration of intent or a promise made by the speaker. Here are a few examples to illustrate this type of speech act:

- “I promise I will help you move next weekend.”

- “I swear I will finish this project by the deadline.”

- “I commit to attending the meeting on Friday.”

Commissive speech acts have several distinct characteristics that set them apart from other types of speech acts:

- Future-oriented: Commissive statements refer to actions or obligations that will be fulfilled in the future.

- Intentional: The speaker consciously expresses their intention to carry out the promised action.

- Volitional: Commissives emphasize the speaker’s willingness and commitment to fulfill their promise.

- Binding: Once a commissive statement is made, it creates an expectation and obligation for the speaker to follow through with their commitment.

The power of commissive speech acts lies in their ability to establish trust and reliability within interpersonal relationships. When someone makes a promise or commitment, it creates a sense of accountability and enhances trust between individuals.

Credit: prezi.com

Expressive Speech Acts

Speech acts are expressive forms of communication that can be categorized into various types. These include assertive acts that make statements, directive acts that give commands, commissive acts that make commitments, expressive acts that convey emotions, and declarative acts that change the state of affairs.

Frequently Asked Questions Of What Are The Types Of Speech Acts?

What are the 5 basic types of speech acts.

The 5 basic types of speech acts are: assertives (making assertions or stating facts), directives (giving commands or making requests), commissives (making promises or commitments), expressives (expressing feelings or attitudes), and declaratives (declaring something and causing a change in the world).

What Are The 4 Different Speech Acts?

The 4 different speech acts are assertives, directives, commissives, and expressives. Assertives state facts or provide information. Directives give instructions or requests. Commissives commit to future actions. Expressives convey emotions or feelings.

What Are The 3 Types Of Speech Act And Their Functions?

The three types of speech acts are locutionary, illocutionary, and perlocutionary. Locutionary acts refer to the literal meaning of words. Illocutionary acts express intentions, such as making requests or giving orders. Perlocutionary acts aim to influence the thoughts or actions of others.

What Are The 7 Functions Of Speech Act?

The 7 functions of speech act include stating, commanding, questioning, promising, expressing gratitude, apologizing, and complimenting. These functions help individuals communicate their intentions and convey specific messages in various social interactions.

What Are The Different Types Of Speech Acts?

Speech acts are classified into five main categories: assertive, directive, commissive, expressives, and declaratives. Each type serves a different purpose in communication.

To summarize, understanding the different types of speech acts is crucial for effective communication. By recognizing the distinctions between assertive, directive, commissive, expressive, and declarative speech acts, individuals can better navigate social interactions and convey their intentions clearly. Whether in personal or professional settings, mastering these speech acts can enhance relationships, facilitate agreements, and ensure mutual understanding.

By continually honing these skills, we can become more successful communicators in our daily lives.

Similar Posts

Is Communication a Science Or Art?

Communication is both a science and an art that involves the study and practice of conveying information effectively. It combines scientific principles such as understanding human psychology, language, and technology with creative skills like storytelling and persuasion. Effective communication requires a systematic approach to understand the process and principles involved, as well as the creativity…

What Degree is Best for Communication?

The best degree for communication is a Bachelor’s degree in Communications. With this degree, you’ll gain the necessary skills for a successful career in various fields such as public relations, marketing, journalism, or event planning. Additionally, a Communications degree provides a solid foundation in interpersonal and organizational communication, media studies, and critical thinking, equipping you…

What are the Basic Functions of Communication?

The basic functions of communication are to inform and persuade. Effective communication is essential for conveying information and convincing others of a particular viewpoint. Communication allows individuals to exchange ideas, share knowledge, and express emotions. It plays a crucial role in building relationships, both personal and professional. Through communication, we can gather information, clarify doubts,…

What is the Objective of Communication?

The objective of communication is to convey information effectively and efficiently. It plays a crucial role in transmitting ideas, thoughts, and emotions between individuals or groups. Communication helps people understand each other, build relationships, and collaborate towards shared goals. Effective communication ensures clarity, reduces misunderstandings, and fosters positivity. It is instrumental in business success, enabling…

Internal Barriers of Communication

Internal barriers of communication include territorialism, dismissiveness, subjective judgment, and the inability or unwillingness to differentiate perception from reality. These barriers can hinder effective communication and lead to misunderstandings and conflicts. They often arise from individuals who struggle to accept their fallibility and draw unfair and negative conclusions about others. In extreme cases, such as…

What is Ship to Ship Communication?

Ship to ship communication involves the exchange of information and data between two or more ships. It enables direct communication and coordination for various purposes, such as navigational safety, operational efficiency, and emergency situations at sea. It plays a vital role in ensuring smooth and secure maritime operations, allowing ships to communicate effectively with each…

Speech Acts and Conversation

Language use: functional approaches to syntax, language in use, sentence structure and the function of utterances, speech acts, the cooperative principle, violations of the cooperative principles, politeness conventions, speech events, the organization of conversation, cross-cultural communication.

Acts of Speech: Types and Examples

The speech acts they are statements, propositions or statements that serve so that the speaker, beyond declaring something, perform an action. They are usually sentences in the first person and in the present, as "to that you do not !","S I tell you, I do not speak to you" and"l increase its loss", that They can represent a challenge, a threat and a condolence, respectively.

The theory of speech acts was developed by J. L. Austin in 1975. In his theory, Austin does not focus on the function of language to describe reality, represent states of affairs or make claims about the world; instead, Austin analyzes the variety of uses of the language. This was his great contribution to contemporary philosophy.

This theory is related to the concept of illocutionary or illocutionary acts, introduced by Austin. It refers to the attitude or intention of the speaker in pronouncing a statement: c when someone says:"I am going to do it", their intention (or illocutionary act) may be to utter a threat, a warning or a promise; the interpretation depends on the context.

- 1.1 According to its general function

- 1.2 According to its structure

- 3 References

According to its general function

American philosopher John Searle analyzed illocutionary acts and discovered that there are at least a dozen linguistically significant dimensions that differentiate them. Based on this, he made a taxonomy.

Assertive or representative

This type of acts engage the speaker with the truth of an expressed proposition. Some of the illocutionary acts are: affirm, suggest, declare, present, swear, describe, boast and conclude.

"There is no better cook than me."

Direct speech acts seek the recipient to perform an action. Among others, illocutionary acts are: order, request, challenge, invite, advise, beg and beg.

"Would you be so kind as to pass me the salt?"

Commissives

These acts commit the speaker to do something in the future. The different types are: promises, threats, votes, offerings, plans and bets.

"I will not let you do that."

This type of act expresses how the speaker feels about the situation or manifests a psychological state. Among these are: thanks, apologies, welcome, complaints and congratulations.

"Really, I'm sorry I said that."

Declarations

Speech acts classified as statements change or affect a situation or state immediately.

"I now pronounce you husband and wife".

According to its structure

In addition to distinguishing speech acts according to their general function (giving an order, asking permission, inviting), these can also be distinguished with respect to their structure.

In this sense, Austin argued that what is said (locutionary act) does not determine the illocutionary act that is performed. Therefore, speech acts can be direct or indirect.

Direct speech acts

Generally, direct speech acts are performed using performative verbs. This class of verbs explicitly convey the intention of the utterance. Among others, they include: promising, inviting, apologizing and predicting.

Sometimes, a performative verb is not used; however, the illocutionary force is perfectly clear. Thus, the expression"shut up!"In a given context can clearly be an order.

Indirect speech acts

On the other hand, in indirect speech acts, the illocutionary force does not manifest itself directly. Thus, inference must be used to understand the intention of the speaker.

For example, in a work context, if a boss tells his secretary:"Do not you think that skirt is not appropriate for the office?", Is not really consulting his opinion, but ordering him not to use that garment anymore.

- I suggest you go and ask for forgiveness. (Suggestion, direct).

- Why do not you go and ask for forgiveness? (Suggestion, indirect).

- I conclude that this was the best decision. (Conclusion, direct).

- Definitely, this was the best decision. (Conclusion, indirect).

- I boast of being the best seller in my company. (Boasting, direct).

- The best seller in the company is the one that makes the most sales, and I was the one who made the most sales! (Boasting, indirect).

- I beg you not to tell her anything yet. (Supplication, direct).

- Do not tell anything to her yet, please. (Supplication, indirect).

- Because of our friendship, I ask you to reconsider your attitude. (Request, direct).

- For our friendship, can you reconsider your attitude? (Request, indirect).

- I invite you to meet my house next Saturday. (Invitation, direct).

- Come and meet my house next Saturday. (Invitation, indirect).

- I promise I'll be there before nine. (Promise, direct).

- Relax, I'll be there before nine. (Promise, indirect).

- I assure you that if you do not come, I will tell everything to her. (Threat, direct).

- Well, you know how it is... I could tell everything to her if you do not come. (Threat, indirect).

- I bet he will not have the courage to appear before his parents. (Bet, direct).

- If you have the courage to appear before your parents, I invite you to lunch (Bet, indirect).

- Sorry if I did not take you into account. (Sorry, direct).

- I already know that I should have taken you into account. (Sorry, indirect).

- Congratulations for having achieved this success. (Congratulations, direct).

- You must be very proud of having achieved this success. (Congratulations, indirect).

- I appreciate all the support given in this terrible situation. (Gratitude, direct).

- I do not know how to pay all the support given in this terrible situation. (Thanks, indirect).

- By the confession of your mouth I now baptize you in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. (Baptism).

- By the power conferred by law, now I declare you husband and wife." (Declaration of marriage).

- I end the session. (End of a session).

- I declare him innocent of all the charges against him. (Legal acquittal).

- As of this moment, I renounce irrevocably. (Resignation).

- Fromkin, V.; Rodman, R. and Hyams, N. (2013). An Introduction to Language. Boston: Cengage Learning.

- Berdini, F. and Bianchi, C. (s / f). John Langshaw Austin (1911-1960). Taken from iep.utm.edu.

- Nordquist, R. (2017, May 05). Illocutionary Act. Taken from thoughtco.com.

- IT. (s / f). Realizations of Speech Acts. Direct and indirect speech acts. Taken from it.uos.de.

- Tsovaltzi, D.; Walter, S. and Burchardt, A. (). Searle's Classification of Speech Acts. Taken from coli.uni-saarland.de.

- Fotion, N. (2000). Searle. Teddington: Acumen.

Recent Posts

Examples of Speech acts/direct/indirect/classification

Speech acts

Speech acts are statements that constitute actions. They correspond to the language in use, to the language in practice, in the concrete communicative situation. When we speak, we not only speak words but also perform certain actions: we describe, invite, advise, greet, congratulate, discuss, etc., that is, we do things with words. It matters not only what we say, but how we do it and with what intention. Examples of Speech acts

The origin of speech act theory dates back to the studies of Reid, Reinach, and Austin. To the elements contributed by these authors, Searle adds the primary role of the intentions, both of the speaker and the listener, in the constitution of a complete meaning of the speech act. A speech act, says our author, is the minimum and basic unit of linguistic communication and distinguishes between the act of issuing words , morphemes or sentences – act of issuance – and the act of attributing to those words a reference and preaching – propositional act. When comparing these elements with those proposed by Austin, the coincidence between the two authors regarding the “consecutive” component of the speech act can be appreciated. Searle, in addition, would admit an illocutive and perlocutive dimension in linguistic uses. Examples of Speech acts

From this perspective, the speaker when participating in a communicative process triggers three acts of communication:

Direct speech acts

When the intention of the issuer is clearly understood. For example, if a man asks a boy:

This is a direct speech act because it is clearly stated that it is a command.

Indirect speech acts

When the intention of the issuer is not clearly expressed. If the same man says to the boy:

This is an indirect speech act, as you are not clearly stating the order or request, but the other must “take it for granted” and facilitate the diary. In this case, a hint was made, which within the context can be understood, but which strictly speaking is not a clear order, because the true intention is to make the other facilitate the diary. Examples of Speech acts

If a specific action is requested, the most direct way is to use the imperative, for example, “Turn off the light”, but this statement can be impolite or cause discomfort, both for the speaker and the receiver. Hence, we prefer to use indirect forms that could be manifested with statements such as:

Speech acts are concrete, therefore, they are in the plane of everyday speech. They respond to the situations of the context , that is why they will be different depending on the degree of formality and the standard used. The norm, as we already know, corresponds to the degree of education of the people. Depending on the specific situations that people have to live in, they will be more or less formal. It’s clearly a different situation if someone talks to their boss or talks to friends. In the first case, his speech acts will be of a greater degree of formality and, if he is a person of a cultured level, he will try to speak according to that level. In the second case, if he is a cultured person, he will continue in that registry, but his degree of formality will be different. There will be more closeness and the treatment will be equal to equal.

Classification of Speech Acts Examples of Speech acts

Speech acts can also be classified according to the type of action carried out through them. This action is manifested fundamentally in the verbal form of the sentences that we produce. In this way, we can say that there are five types of speech acts: Examples of Speech acts

1. Assertive

The speaker affirms something about the world, that is, he elaborates a referential content that represents things or states of affairs in the world. For example: Examples of Speech acts

2. Compromising

By means of these acts, the speaker commits himself to carry out an action in the future. For example:

3. Directors

Acts that seek to direct the listener or engage him in an action, making him act according to the wishes of the speaker . For example:

4. Declarative Examples of Speech acts

Acts that create a new state of affairs in the world through the word, for example, when priests bless or marry two people and when judges sentence. It requires a certain level of authority on the part of the issuer. For example, if a teacher says when expelling a student: Examples of Speech acts

5. Expressive

Through these acts, the speaker expresses his feelings and attitudes towards situations in the external world. For example:

Based on this classification, any statement can be categorized as a particular speech act that is carrying out an action in the communicative interaction. Examples of Speech acts

Related Articles

Cataphora and difference with anaphora with illustration, types of inference with examples techniques features, grice’s conversational maxims, cohesive devices examples types substitution conjunction, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Please input characters displayed above.

- Cohesive devices examples Types Substitution Conjunction October 4, 2023

Speech Acts

Speech acts are a staple of everyday communicative life, but only became a topic of sustained investigation, at least in the English-speaking world, in the middle of the Twentieth Century. [ 1 ] Since that time “speech act theory” has been influential not only within philosophy, but also in linguistics, psychology, legal theory, artificial intelligence, literary theory and many other scholarly disciplines. [ 2 ] Recognition of the importance of speech acts has illuminated the ability of language to do other things than describe reality. In the process the boundaries among the philosophy of language, the philosophy of action, the philosophy of mind and even ethics have become less sharp. In addition, an appreciation of speech acts has helped lay bare an implicit normative structure within linguistic practice, including even that part of this practice concerned with describing reality. Much recent research aims at an accurate characterization of this normative structure underlying linguistic practice.

1. Introduction

2.1 the independence of force and content, 2.2 can saying make it so, 2.3 seven components of illocutionary force, 3. illocutions and perlocutions, and indirect speech acts, 4. force, fit and satisfaction, 5.1 force conventionalism, 5.2. an objection to force conventionalism, 6.1 grice's account of speaker meaning, 6.2 objections to grice's account, 6.3 force as an aspect of speaker meaning, 7.1 speech acts and conversation analysis, 7.2 speech acts and scorekeeping, 8. force-indicators and the logically perfect language, 9. do speech acts have a logic, further reading, other internet resources, related entries.

One way of appreciating the distinctive features of speech acts is in contrast with other well-established phenomena within the philosophy of language. Accordingly in this entry I will consider the relation among speech acts and: semantic content, grammatical mood, speaker-meaning, logically perfect languages, perlocutions, performatives, presuppositions, and implicature. This will enable us to situate speech acts within their ecological niche.

Above I shuddered with quotation marks around the expression ‘speech act theory’. It is one thing to say that speech acts are a phenomenon of importance for students of language and communication; another to say that we have a theory of them. While, as we shall see below, we are able to situate speech acts within their niche, having a theory of them would enable us to explain (rather than merely describe) some of their most significant features. Consider a different case. Semantic theory deserves its name: For instance, with the aid of set-theoretic tools it helps us tell the difference between good arguments and bad arguments couched in ordinary language. By contrast, it is not clear that “speech act theory” has comparable credentials. One such credential would be a delineation of logical relations among speech acts, if such there be. To that end I close with a brief discussion of the possibility, envisioned by some, of an “illocutionary logic”.

2. Content, Force, and How Saying Can Make It So

Construed as a bit of observable behavior, a given act may be done with any of a variety of aims. I bow deeply before you. So far you may not know whether I am paying obeisance, responding to indigestion, or looking for a wayward contact lens. So too, a given utterance, such as ‘You'll be more punctual in the future,’ may leave you wondering whether I am making a prediction or issuing a command or even a threat. The colloquial question, “What is the force of those words?” is often used to elicit an answer. In asking such a question we acknowledge a grasp of what those words mean. However, given the dizzying array of uses of ‘meaning’ in philosophy and related cognitive sciences, I will here refer instead to content. While different theories of content abound (as sets of possible worlds, sets of truth conditions, Fregean senses, ordered n -tuples, to name a few), the phenomenon is relatively clear: What the speaker said is that the addressee will be more punctual in the future. The addressee or observer who asks, “What is the force of those words?” is asking, of that content, how it's to be taken–as a threat, as a prediction, or as a command. The addressee is not asking for a further elucidation of that content.

Or so it seems. Perhaps whether the utterance is meant as a threat, a prediction or a command will depend on some part of her content that was left unpronounced? According to this suggestion, really what she said was, “I predict you'll be more punctual,” or “I command you to be more punctual,” as the case may be. Were that so, however, she'd be contradicting herself in uttering ‘You'll be more punctual in the future’ as a prediction while going on to point out, ‘I don't mean that as a prediction.’ While such a juxtaposition of utterances is surely odd, it is not a self-contradiction, any more than “It's raining but I don't believe it,” is a self-contradiction when the left conjunct is put forth as an expression of belief. What is more, ‘I predict you'll be more punctual,’ is itself a sentence with a content, and will be being put forth with some force or other when–as per our current suggestion—the speaker says it in the course of making a prediction. So that sentence, ‘I predict you'll be more punctual’ is put forth with some force–say as an assertion. This implies, according to the present suggestion, that really the speaker said, ‘I assert that I predict that you'll be more punctual.’ Continuing this same style of reasoning will enable us to infer that performance of a single speech act requires saying–though perhaps not pronouncing—infinitely many things. That is reason for rejecting the hypothesis that implied it, and for the rest of this entry I will assume that force is no part of content.

In chemical parlance, a radical is a group of atoms normally incapable of independent existence, whereas a functional group is the grouping of those atoms in a compound that is responsible for certain of the compound's properties. Analogously, it is often remarked that a proposition is itself communicatively inert; for instance, merely expressing the proposition that snow is white is not to make a move in a “language game”. Rather, such moves are only made by putting forth a proposition with an illocutionary force such as assertion, conjecture, command, etc. The chemical analogy gains further plausibility from the fact that just as a chemist might isolate radicals held in common among various compounds, the student of language may isolate a common element held among ‘Is the door shut?’, ‘Shut the door!’, and ‘The door is shut’. This common element is the proposition that the door is shut, queried in the first sentence, commanded to be made true in the second, and asserted in the third. According to the chemical analogy, then:

Illocutionary force : propositional content :: functional group : radical

In light of this analogy we may see, following Stenius 1967, that just as the grouping of a set of atoms is not itself another atom or set of atoms, so too the forwarding of a proposition with a particular illocutionary force is not itself a further component of propositional content.

Encouraged by the chemical analogy, a central tenet in the study of speech acts is that content may remain fixed while force varies. Another way of putting the point is that the content of one's communicative act underdetermines the force of that act. That's why, from the fact that someone has said, “You'll be more punctual in the future,” we cannot infer the utterance's force. The force of an utterance also underdetermines its content: Just from the fact that a speaker has made a promise, we cannot deduce what she has promised to do. For these reasons, students of speech acts contend that a given communicative act may be analyzed into two components: force and content. While semantics studies the contents of speech acts, pragmatics studies, inter alia , their force. The bulk of this entry may be seen as an elucidation of force.

Need we bother with such an elucidation? That A is an important component of communication, and that A underdetermines B , do not justify the conclusion that B is an important component of communication. Content also underdetermines the decibel level at which we speak but this fact does not justify adding decibel level to our repertoire of core concepts for the philosophy of language. Why should force be thought any more worthy of admission to this set of core concepts than decibel level? One reason for an asymmetry in our treatment of force and decibel level is that the former, but not the latter, seems to be a component of speaker meaning : Force is a feature not of what is meant but of how it is meant; decibel level, by contrast, is a feature at most of the way in which something is said. This point is developed in Section 6 below.

Speech acts are not to be confused with acts of speech. One can perform a speech act such as issuing a warning without saying anything: A gesture or even a minatory facial expression will do the trick. So too, one can perform an act of speech, say by uttering words in order to test a microphone, without performing a speech act. [ 3 ] For a first-blush delineation of the range of speech acts, then, consider that in some cases we can make something the case by saying that it is. Alas, I can't lose ten pounds by saying that I am doing so, nor can I persuade you of a proposition by saying that I am doing so. On the other hand I can promise to meet you tomorrow by uttering the words, “I promise to meet you tomorrow,” and if I have the authority to do so, I can even appoint you to an office by saying, “I hereby appoint you.” (I can also appoint you without making the force of my act explicit: I might just say, “You are now Treasurer of the Corporation.” Here I appoint you without saying that I am doing so.) A necessary and, perhaps, sufficient condition of a type of act's being a speech act is that acts of that type can–whether or not all are—be carried out by saying that one is doing so.

Saying can make it so, but that is not to suggest that any old saying by any speaker constitutes the performance of a speech act. Only an appropriate authority, speaking at the appropriate time and place, can: christen a ship, pronounce a couple married, appoint someone to an administrative post, declare the proceedings open, or rescind an offer. Austin, in How To Do Things With Words, spends considerable effort detailing the conditions that must be met for a given speech act to be performed felicitously . Failures of felicity fall into two classes: misfires and abuses . The former are cases in which the putative speech act fails to be performed at all. If I utter, before the QEII, “I declare this ship the Noam Chomsky,” I have not succeeded in naming anything simply because I lack the authority to do so. My act thus misfires in that I've performed an act of speech but no speech act. Other attempts at speech acts might misfire because their addressee fails to respond with an appropriate uptake : I cannot bet you $100 on who will win the election unless you accept that bet. If you don't accept that bet, then I have tried to bet but have not succeeded in betting.

Some speech acts can be performed–that is, not misfire—while still being less than felicitous. I promise to meet you for lunch tomorrow, but haven't the least intention of keeping the promise. Here I have promised all right, but the act is not felicitous because it is not sincere. My act is, more precisely, an abuse because although it is a speech act, it fails to live up to a standard appropriate for a speech act of its kind. Sincerity is a paradigm condition for the felicity of speech acts. Austin foresaw a program of research in which individual speech acts would be studied in detail, with felicity conditions elucidated for each one. [ 4 ]

Here are three further features of the “saying makes it so” condition. First, the saying appealed to in the “saying makes it so” test is not an act of speech: My singing in the shower, “I promise to meet you tomorrow for lunch,” when my purpose is simply to enjoy the sound of my voice, is not a promise, even if you overhear me. Rather, the saying (or singing) in question must itself be something that I mean. We will return in Section 6 to the task of elucidating the notion of meaning at issue here.

Second, the making relation that this “saying makes it so” condition appeals to needs to be treated with some care. My uttering, “I am causing molecular agitation,” makes it the case that I am causing molecular agitation. Yet causing molecular agitation is not a speech act on any intuitive understanding of that notion. One might propose that the notion of making at issue here marks a constitutive relation rather than a causal relation. That may be so, but as we'll see in Section 5, this suggests the controversial conclusion that all speech acts depend for their existence on conventions over and above those that imbue our words with meaning.

Finally, the saying makes it so condition has a flip side. Not only can I perform a speech act by saying that I am doing so, I can also rescind that act later on by saying (in the speech act sense) that I take it back. I cannot, of course, change the past, and so nothing I can do on Wednesday can change the fact that I made a promise or an assertion on Monday. However, on Wednesday I may be able to retract a claim I made on Monday. I can't take back a punch or a burp; the most I can do is apologize for one of these infractions, and perhaps make amends. By contrast, not only can I apologize or make amends for a claim I now regret; I can also take it back. Likewise, you may allow me on Wednesday to retract the promise I made to you on Monday. In both these cases of assertion and promise, I am no longer beholden to the commitments that the speech acts engender in spite of the fact that the past is fixed. Just as one can, under appropriate conditions, perform a speech act by saying that one is doing so, so too one can, under the right conditions, retract that very speech act.

Searle and Vanderveken 1985 distinguish between those illocutionary forces employed by speakers within a given linguistic community, and the set of all possible illocutionary forces. While a certain linguistic community may make no use of a force such as conjecturing or appointing, these two are among the set of all possible forces. (These authors appear to assume that while the set of possible forces may be infinite, it has a definite cardinality.) Searle and Vanderveken go on to define illocutionary force in terms of seven features, claiming that every possible illocutionary force may be identified with a septuple of such values. The features are:

1. Illocutionary point : This is the characteristic aim of each type of speech act. For instance, the characteristic aim of an assertion is to describe how things are; the characteristic point of a promise is to commit oneself to a future course of action.

2. Degree of strength of the illocutionary point : Two illocutions can have the same point but differ along the dimension of strength. For instance, requesting and insisting that the addressee do something both have the point of attempting to get the addressee to do that thing; however, the latter is stronger than the former.

3. Mode of achievement : This is the special way, if any, in which the illocutionary point of a speech act must be achieved. Testifying and asserting both have the point of describing how things are; however, the former also involves invoking one's authority as a witness while the latter does not. To testify is to assert in one's capacity as a witness. Commanding and requesting both aim to get the addressee to do something; yet only someone issuing a command does so in her capacity as a person in a position of authority.

4. Propositional content conditions : Some illocutions can only be achieved with an appropriate propositional content. For instance, I can only promise what is in the future and under my control. I can only apologize for what is in some sense under my control and already the case. For this reason, promising to make it the case that the sun did not rise yesterday is not possible; neither can I apologize for the truth of Snell's Law.

5. Preparatory conditions : These are all other conditions that must be met for the speech act not to misfire. Such conditions often concern the social status of interlocutors. For instance, a person cannot bequeath an object unless she already owns it or has power of attorney; a person cannot marry a couple unless she is legally invested with the authority to do so.

6. Sincerity conditions : Many speech acts involve the expression of a psychological state. Assertion expresses belief; apology expresses regret, a promise expresses an intention, and so on. A speech act is sincere only if the speaker is in the psychological state that her speech act expresses.

7. Degree of strength of the sincerity conditions : Two speech acts might be the same along other dimensions, but express psychological states that differ from one another in the dimension of strength. Requesting and imploring both express desires, and are identical along the other six dimensions above; however, the latter expresses a stronger desire than the former.

Searle and Vanderveken suggest, in light of these seven characteristics, that each illocutionary force may be defined as a septuple of values, each of which is a “setting” of a value within one of the seven characteristics. It follows, according to this suggestion, that two illocutionary forces F 1 and F 2 are identical just in case they correspond to the same septuple.

I cannot lose ten pounds by saying that I am doing so, and I cannot convince you of the truth of a claim by saying that I am doing so. However, these two cases differ in that the latter, but not the former, is a characteristic aim of a speech act. One characteristic aim of assertion is the production of belief in an addressee, whereas there is no speech act one of whose characteristic aims is the reduction of adipose tissue. A type of speech act can have a characteristic aim without each speech act of that type being issued with that aim: Speakers sometimes make assertions without aiming to produce belief in anyone, even themselves. Instead, the view that a speech act-type has a characteristic aim is akin to the view that a biological trait has a function. The characteristic role of wings is to aid in flight, but some flightless creatures have wings.

Austin called these characteristic aims of speech acts perlocutions (1962, p. 101). I can both urge and persuade you to shut the door, yet the former is an illocution while the latter is a perlocution. How can we tell the difference? We can do this by noting that one can urge by saying, “I urge you to shut the door,” while there are no circumstances in which I can persuade you by saying, “I persuade you to shut the door.” A characteristic aim of urging is, nevertheless, the production of a resolution to act. (1962, p. 107)

Perlocutions are characteristic aims of one or more illocution, but are not themselves illocutions. Nevertheless, a speech act can be performed by virtue of the performance of another one. For instance, my remark that you are standing on my foot is normally taken as, in addition, a demand that you move; my question whether you can pass the salt is normally taken as a request that you do so. These are examples of so-called indirect speech acts (Searle 1975b).

Indirect speech acts are less common than might first appear. In asking whether you are intending to quit smoking, I might be taken as well to be suggesting that you quit. However, while the embattled smoker might indeed jump to this interpretation, we do well to consider what evidence would mandate it. After all, while I probably would not have asked whether you intended to quit smoking unless I hoped you would quit, I can evince such a hope without suggesting anything. Similarly, the advertiser who tells us that Miracle Cream reversed hair loss in Bob, Mike, and Fred, also most likely hopes that I will believe it will reverse my own hair loss. That does not show that he is (indirectly) asserting that it will. Whether he is asserting this depends, it would seem, on whether he can be accused of being a liar if in fact he does not believe that Miracle Cream will staunch my hair loss.

Whether, in addition to a given speech act, I am also performing an indirect speech act would seem to depend on my intentions. My question whether you can pass the salt is also a request that you do so only if I intend to be so understood. My remark that Miracle Cream helped Bob, Mike and Fred is also an assertion that it will help you only if I intend to be so committed. What is more, these intentions must be feasibly discernible on the part of one's audience. Even if, in remarking on the fine weather, I intend as well to request that you pass the salt, I have not done so. I need to make that intention manifest in some way.

How might I do this? One way is by virtue of inference to the best explanation. All else being equal, the best explanation of my asking whether you can pass the salt is that I mean to be requesting that you do so. All else equal, the best explanation of my remarking that you are standing on my foot, particularly if I use a stentorian tone of voice, is that I mean to be demanding that you desist. By contrast, it is doubtful that the best explanation of my asking whether you intend to quit smoking is my intention to suggest that you do so. Another explanation at least as plausible is my hope that you do so. Bertolet 1994, however, develops an even more skeptical position than that suggested here, arguing that any alleged case of an indirect speech act can be construed just as an indication, by means of contextual clues, of the speaker's intentional state–hope, desire, etc., as the case may be. Postulation of a further speech act beyond what has been (relatively) explicitly performed is explanatorily unmotivated.

These considerations suggest that indirect speech acts, if they do occur, can be explained within the framework of conversational implicature–that process by which we mean more than we say, but in a way not due exclusively to the conventional meanings of our words. Conversational implicature, too, depends both upon communicative intentions and the availability of inference to the best explanation. (Grice, 1989). In fact, Searle's 1979b account of indirect speech acts was in terms of conversational implicature. The study of speech acts is in this respect intertwined with the study of conversations; we return to this connection in Section 7.

Force is often characterized in terms of the notions of direction of fit and conditions of satisfaction. The first of these may be illustrated with an example derived from Anscombe (1963). A woman sends her husband to the grocery store with a list of things to get; unbeknownst to him he is also being trailed by a detective concerned to make a list of what the man buys. By the time the husband and detective are in the checkout line, their two lists contain exactly the same items. The contents of the two lists is the same, yet they differ along another dimension. For the contents of the husband's list guide what he puts in his shopping cart. Insofar, his list exhibits world-to-word direction of fit : It is, so to speak, the job of the items in his cart to conform to what is on his list. By contrast, it is the job of the detective's list to conform with the world, in particular to what is in the husband's cart. As such, the detective's list has word-to-world direction of fit : The onus is on those words to conform to how things are. Speech acts such as assertions and predictions have word-to-world direction of fit, while speech acts such as commands have world-to-word direction of fit.

Not all speech acts appear to have direction of fit. I can thank you by saying “Thank you,” and it is widely agreed that thanking is a speech act. However, thanking seems to have neither of the directions of fit we have discussed thus far. Similarly, asking who is at the door is a speech act, but it does not seem to have either of the directions of fit we have thus far mentioned. Some would respond by construing questions as a form of imperative (e.g., “Tell me who is at the door!”), and then ascribing the direction of fit characteristic of imperatives to questions. This leaves untouched, however, banal cases such as thanking or even, “Hooray for Arsenal!” Some authors, such as Searle and Vanderveken 1985, describe such cases as having “null” direction of fit. That characterization is evidently distinct from saying such speech acts have no direction of fit at all. (The characterization is thus analogous to the way in which some non-classical logical theories describe some proposition as being neither True nor False, but as having a third truth value, N : Evidently that is not to say that such propositions are bereft of truth value.) It is difficult to discern from such accounts how one sheds light on a speech act in characterizing it as having a null direction of fit, as opposed to having no direction of fit at all. [ 5 ]

Direction of fit is also not so fine-grained as to enable us to distinguish speech acts meriting different treatment. Consider asserting that the center of the Milky Way is inhabited by a black hole, as opposed to conjecturing that the center of the Milky Way is so inhabited. These two acts seem subject to norms: The former purports to be a manifestation of knowledge, while the latter does not. This is suggested by the fact that it is appropriate to reply to the assertion with, “How do you know?”, while that is not an appropriate response to the conjecture. (Williamson 1996) Nevertheless, both the assertion and conjecture have word-to-world direction of fit. Might there be other notions enabling us to mark differences between speech acts with the same direction of fit? This is not to say that the difference between assertion and conjecture cannot be expressed as a difference among Searle and Vanderveken's seven components of illocutionary force; for instance that difference might be thought of as a difference in parameter 2, namely the degree of strength of illocutionary point. Rather, what we are seeking is an account of, rather than a label for, that difference.

One suggestion might come from the related notion of conditions of satisfaction . This notion generalizes that of truth. As we saw in 2.3, it is internal to the activity of assertion that it aims to capture how things are. When an assertion does so, not only is it true, it has hit its target; the aim of the assertion has been met. A similar point may be made of imperatives: It is internal to the activity of issuing an imperative that the world is enjoined to conform to it. The imperative is satisfied just in case it is fulfilled. Assertions and imperatives both have conditions of satisfaction–truth in the first place, and conformity in the second. In addition, it might be held that questions have answerhood as their conditions of satisfaction: A question hits its target just in case it finds an answer, typically in a speech act, performed by an addressee, such as an assertion that answers the question posed. Like the notion of direction of fit, however, the notion of conditions of satisfaction is too coarse-grained to enable us to make some valuable distinctions among speech acts. Just to use our earlier case again: An assertion and a conjecture that P have identical conditions of satisfaction, namely that P be the case. May we discern features distinguishing these two speech acts, and that may enable us to make finer-grained distinctions among other speech acts as well? I shall return to this question in Section 7.

5. Mood, Force and Convention

Just as content underdetermines force and force underdetermines content; so too even grammatical mood together with content underdetermine force. ‘You'll be more punctual in the future’ is in the indicative grammatical mood, but as we have seen that fact does not determine its force. The same may be said of other grammatical moods. Although I overhear you utter the words, ‘shut the door’, I cannot infer yet that you are issuing a command. Perhaps instead you are simply describing your own intention, in the course of saying, “I intend to shut the door.” If so, you've used the imperative mood without issuing a command. So too with the interrogative mood: I overhear your words, ‘who is on the phone.’ Thus far I don't know whether you've asked a question. After all, you may have so spoken in the course of stating, “John wonders who is on the phone.” Might either or both of initial capitalization or final punctuation settle the issue? Apparently not: What puzzles John is the following question: Who is on the phone?

Mood together with content underdetermine force. On the other hand it is a plausible hypothesis that grammatical mood is one of the devices we use, together with contextual clues, intonation and so on to indicate the force with which we are expressing a content. Understood in this weak way, it is unexceptionable to construe the interrogative mood as used for asking questions, the imperatival mood as used for issuing commands, and so on. So understood, we might go on to ask how speakers indicate the force of their speech acts given that grammatical mood and content cannot be relied on alone to do so.

One well known answer we may term force conventionalism . According to a strong version of this view, for every speech act that is performed, there is some convention that will have been invoked in order to make that speech act occur. This convention transcends those imbuing words with their literal meaning. Thus, force conventionalism implies that in order for use of ‘I promise to meet you tomorrow at noon,’ to constitute a promise, not only must the words used possess their standard conventional meanings, there must also exist a convention to the effect that the use, under the right conditions, of some such words as these constitutes a promise. J.L. Austin, who introduced the English-speaking world to the study of speech acts, seems to have held this view. For instance in his characterization of “felicity conditions” for speech acts, Austin holds that for each speech act

There must exist an accepted conventional procedure having a certain conventional effect, that procedure to include the uttering of certain words by certain persons in certain circumstances… (1962, p. 14).

Austin's student Searle follows him in this, writing

…utterance acts stand to propositional and illocutionary acts in the way in which, e.g., making an X on a ballot paper stands to voting. (1969, p. 24)

Searle goes on to clarify this commitment in averring,

…the semantic structure of a language may be regarded as a conventional realization of a series of sets of underlying constitutive rules, and …speech acts are acts characteristically performed by uttering sentences in accordance with these sets of constitutive rules. (1969, p. 37)

Searle espouses a weaker form of force conventionalism than does Austin in leaving open the possibility that some speech acts can be performed without constitutive rules; Searle considers the case of a dog requesting to be let outside (1969, p. 39). Nevertheless Searle does contend that speech acts are characteristically performed by invoking constitutive rules.

Force-conventionalism, even in the weaker form just adumbrated, has been challenged by Strawson, who writes,

I do not want to deny that there may be conventional postures or procedures for entreating: one can, for example, kneel down, raise one's arms, and say, “I entreat you.” But I do want to deny that an act of entreaty can be performed only as conforming to such conventions….[T]o suppose that there is always and necessarily a convention conformed to would be like supposing that there could be no love affairs which did not proceed on lines laid down in the Roman de la Rose or that every dispute between men must follow the pattern specified in Touchstone's speech about the countercheck quarrelsome and the lie direct. (1964, p. 444)

Strawson contends that rather than appealing to a series of extra-semantic conventions to account for the possibility of speech acts, we explain that possibility in terms of our ability to discern one another's communicative intentions. What makes an utterance of a sentence in the indicative mood a prediction rather than a command, for instance, is that it is intended to be so taken; likewise for promises rather than predictions. This position is compatible with holding that in special cases linguistic communities have instituted conventions for particular speech acts such as entreating and excommunicating.

Intending to make an assertion, promise, or request, however, is not enough to perform one of these acts. Those intentions must be efficacious. The same point applies to cases of trying to perform a speech act, even when what one is trying to do is clear to others. This fact emerges from reflecting on an oft-quoted passage from Searle:

Human communication has some extraordinary properties, not shared by most other kinds of human behavior. One of the most extraordinary is this: If I am trying to tell someone something, then (assuming certain conditions are satisfied) as soon as he recognizes that I am trying to tell him something and exactly what it is I am trying to tell him, I have succeeded in telling it to him. (1969, p. 47.)

An analogous point would not apply to the act of sending : Just from the facts that I am trying to send my addressee something, and that he recognizes that I am trying to do so (and what it is I am trying to send him), we cannot infer that I have succeeded in sending it to him. However, while Searle's point about telling looks more plausible at first glance than would a point about sending, it also is not accurate. Suppose I am trying to tell somebody that I love her, and that she recognizes this fact on the basis of background knowledge, my visible embarrassment, and my inability to get past the letter ‘l’. Here we cannot infer that I have succeeded in avowing my love for her. Nothing short of coming out and saying it will do. Similarly, it might be common knowledge that my moribund uncle is trying, as he breathes his last, to bequeath me his fortune; still, I won't inherit a penny if he expires before saying what he was trying to. [ 6 ]

The gist of these examples is not the requirement that words be uttered in every speech act–we have already observed that speech acts can be performed silently. Rather, its gist is that speech acts involve intentional undertaking of one or another form of commitment; further, that commitment is not undertaken simply by virtue of my intending to undertake it, even when it is common knowledge that this is what I am trying to do. Can we, however, give a more illuminating characterization of the relevant intentions than merely saying that, for instance, to assert P one must intentionally put forth P as an assertion? [ 7 ] Strawson (1964) proposes that we can do so with aid of the notion of speaker meaning–a topic to which I now turn.

6. Speaker-Meaning and Force

As we have seen, that A is an important component of communication, and that A underdetermines B , do not justify the conclusion that B is an important component of communication. One reason for an asymmetry in our treatment of force and decibel level is that the former, but not the latter, seems to be a component of speaker meaning. I intend to speak at a certain volume, and sometimes succeed, but in most cases it is no part of what I mean that I happen to be speaking at the volume that I do. On the other hand, the force of my utterance is part of what I mean. It is not, as we have seen, part of what I say–that notion being closely associated with content. However, whether I mean what I say as an assertion, a conjecture, a promise or something else will be a feature of how I mean what I do.

Let us elucidate this notion of speaker meaning (née non-natural meaning). In his influential 1957 article, Grice distinguished between two senses of ‘mean’. One sense is exemplified by remarks such as ‘Those clouds mean rain,’ and ‘Those spots mean measles.’ The notion of meaning in play in such cases Grice dubs ‘natural meaning’. Grice suggests that we may distinguish this sense of ‘mean’ from another sense of the word more relevant to communication, exemplified in such utterances as

In saying “You make a better door than a window”, George meant that you should move,

In gesticulating that way, Salvatore means that there's quicksand over there,

Grice used the term ‘non-natural meaning’ for this sense of ‘mean’, and in more recent literature this jargon has been replaced with the term ‘speaker meaning’. [ 8 ] After distinguishing between natural and (what we shall heretofore call) speaker meaning, Grice attempts to characterize the latter. It is not enough that I do something that influences the beliefs of an observer: In putting on a coat I might lead an observer to conclude that I am going for a walk. Yet in such a case it is not plausible that I mean that I am going for a walk in the sense germane to speaker meaning. Might performing an action with an intention of influencing someone's beliefs be sufficient for speaker meaning? No: I might leave Smith's handkerchief at the crime scene to make the police think that Smith is the culprit. However, whether or not I am successful in getting the authorities to think that Smith is the culprit, in this case it is not plausible that I mean that Smith is the culprit.

What is missing in the handkerchief example is the element of overtness. This suggests another criterion: Performing an action with the, or an, intention of influencing someone's beliefs, while intending that this very intention be recognized. Grice contends that even here we do not have enough for speaker meaning. Herod presents Salome with St. John's severed head on a charger, intending that she discern that St. John is dead and intending that this very intention of his be recognized. Grice observes that in so doing Herod is not telling Salome anything, but is instead deliberately and openly letting her know something. Grice concludes that Herod's action is not a case of speaker meaning either. The problem is not that Herod is not using words; we have already considered hunters who mean things wordlessly. The problem seems to be that to infer what Herod intends her to, Salome does not have to take his word for anything. She can see the severed head for herself if she can bring herself to look. By contrast, in its central uses, telling requires a speaker to intend to convey information (or alleged information) in a way that relies crucially upon taking her at her word. Grice appears to assume that at least for the case in which what is meant is a proposition (rather than a question or an imperative), speaker meaning requires a telling in this central sense. What is more, this last example is a case of performing an action with an intention of influencing someone's beliefs, even while intending that this very intention be recognized; yet it is not a case of telling. Grice infers that it is not a case of speaker meaning either.

Grice holds that for speaker meaning to occur, not only must one (a) intend to produce an effect on an audience, and (b) intend that this very intention be recognized by that audience, but also (c) one must intend this effect on the audience to be produced at least in part by their recognition of the speaker's intention. The intention to produce a belief or other attitude by means (at least in part) of recognition of this very intention, has come to be called a reflexive communicative intention .

It has, however, been shown that intentions to produce cognitive or other effects on an audience are not necessary for speaker meaning. Davis 1992 offers many cases of speaker meaning in the absence of reflexive communicative intentions. Indeed, he forcefully argues that speaker meaning can occur without a speaker intending to produce any beliefs in an audience. [ 9 ] [ 10 ] Instead of intentions to produce certain effects in an audience, some authors have proposed that speaker meaning is a matter of overtly indicating some aspect of oneself. (Green, 2007). Compare my going to the closet to take out my overcoat (not a case of speaker meaning), with the following case: After heatedly arguing about the weather, I march to the closet while beadily meeting your stare, then storm out the front door while ostentatiously donning the coat. Here it's a lot more plausible that I mean that it's raining outside, and the reason seems to be that I am making some attitude of mine overt: I am not only showing it, I am making clear my intention to do just that.

How does this help to elucidate the notion of force? One way of asserting that P , it seems, is overtly to manifest my commitment to P , and indeed commitment of a particular kind: commitment to defend P in response to challenges of the form, “How do you know that?” I must also overtly manifest my liability to be either right or wrong on the issue of P depending on whether P is the case. By contrast, I conjecture P by overtly manifesting my commitment to P in this same “liability to error” way; but I am not committed to responding to challenges demanding justification. I must, however, give some reason for believing P ; this much cannot, however, be said of a guess.

We perform a speech act, then, when we overtly commit ourselves in a certain way to a content–where that way is an aspect of how we speaker-mean that content. One way to do that is to invoke a convention for undertaking commitment; another way is overtly to manifest one's intention to be so committed. We may elucidate the relevant forms of commitment by spelling out the norms underlying them. We have already adumbrated such an approach in our discussion of the differences among asserting and conjecturing. Developing that discussion a bit further, compare

- conjecturing

All three of these acts have word-to-world direction of fit, and all three have conditions of satisfaction mandating that they are satisfied just in case the world is as their content says it is. Further, one who asserts, conjectures, or guesses that P is right or wrong on the issue of P depending on whether P is in fact so. However, as we move from left to right we find a decreasing order of stringency in commitment. One who asserts P lays herself open to the challenge, “How do you know that?”, and she is obliged to retract P if she is unable to respond to that challenge adequately. By contrast, this challenge is inappropriate for either a conjecture or a guess. On the other hand, we may justifiably demand of the conjecturer that she give some reason for her conjecture; yet not even this much may be said of one who makes a guess. (The “educated guess” is intermediate between these two cases.)

We may think of this illocutionary dimension of speaker meaning as characterizing not what is meant, but rather how it is meant. Just as we may consider your remark, directed toward me, “You're tired,” and my remark, “I'm tired,” as having said the same thing but in different ways; so too we may consider my assertion of P , followed by a retraction and then followed by a conjecture of P , as two consecutive cases in which I speaker-mean that P but do so in different ways. This idea will be developed a bit further in Section 9 under the rubric of “mode” of illocutionary commitment.

Speaker meaning, then, applies not just to content but also to force, and we may elucidate that claim with a further articulation of the normative structure characteristic of each speech act: When you overtly display a commitment characteristic of that speech act, you have performed that speech act. Is this a necessary condition as well? That depends on whether I can perform a speech act without intending to do so—a topic for Section 9 below. For now, however, compare the view at which we have arrived with Searle's view that one performs a speech act when others become aware of one's intention, or at least one's attempt, to perform that act. What is missing from Searle's characterization is the notion of overtness: The agent in question must not only make her intention to undertake a certain commitment manifest; she must also intend that that very intention be manifest. There is more to overtness than wearing one's heart (or mind) on one's sleeve.

7. Force, Norms, and Conversation

In elucidating this normative dimension of force, we have brought speech acts into their conversational context. That is not to say that speech acts can only be performed in the setting of a conversation: I can approach you, point out that your vehicle is blocking mine, and storm off. Here I have made an assertion but have not engaged in a conversation. Perhaps I can ask myself a question in the privacy of my study and leave it at that–not continuing into a conversation with myself. However, it might reasonably be held that a speech act's ecological niche is nevertheless the conversation. In that spirit, while we may be able to remove it from its environment and scrutinize it in isolated captivity, doing so may leave us blind to some of its distinctive features.

This ecological analogy sheds light on a dispute over the question whether speech acts can profitably be studied in isolation from the conversations in which they occur. An empiricist framework, exemplified in John Stuart Mill's, A System of Logic , suggests attempting to discern the meaning of a word, for instance a proper name, in isolation. By contrast, Gottlob Frege (1884) enjoins us to understand a word's meaning in terms of the contribution it makes to an entire sentence. Such a method is indispensable for a proper treatment of such expressions as quantifiers, and represents a major advance over empiricist approaches. Yet students of speech acts have espoused going even further, insisting that the unit of significance is not the proposition but the speech act. Vanderveken writes,

Illocutionary acts are important for the purpose of philosophical semantics because they are the primary units of meaning in the use and comprehension of natural language. (Vanderveken, 1990, p. 1.)

Why not go even further, since speech acts characteristically occur in conversations? Is the unit of significance really the debate, the colloquy, the interrogation?