Available 9 a.m.–10 p.m.

Additional Options

- smartphone Call / Text

- voice_chat Consultation Appointment

- place Visit

- email Email

Chat with a Specific library

- Business Library Offline

- College Library (Undergraduate) Offline

- Ebling Library (Health Sciences) Offline

- Gender and Women's Studies Librarian Offline

- Information School Library (Information Studies) Offline

- Law Library (Law) Offline

- Memorial Library (Humanities & Social Sciences) Offline

- MERIT Library (Education) Offline

- Steenbock Library (Agricultural & Life Sciences, Engineering) Offline

- Ask a Librarian Hours & Policy

- Library Research Tutorials

Search the for Website expand_more Articles Find articles in journals, magazines, newspapers, and more Catalog Explore books, music, movies, and more Databases Locate databases by title and description Journals Find journal titles UWDC Discover digital collections, images, sound recordings, and more Website Find information on spaces, staff, services, and more

Language website search.

Find information on spaces, staff, and services.

- ASK a Librarian

- Library by Appointment

- Locations & Hours

- Resources by Subject

book Catalog Search

Search the physical and online collections at UW-Madison, UW System libraries, and the Wisconsin Historical Society.

- Available Online

- Print/Physical Items

- Limit to UW-Madison

- Advanced Search

- Browse by...

collections_bookmark Database Search

Find databases subscribed to by UW-Madison Libraries, searchable by title and description.

- Browse by Subject/Type

- Introductory Databases

- Top 10 Databases

article Journal Search

Find journal titles available online and in print.

- Browse by Subject / Title

- Citation Search

description Article Search

Find articles in journals, magazines, newspapers, and more.

- Scholarly (peer-reviewed)

- Open Access

- Library Databases

collections UW Digital Collections Search

Discover digital objects and collections curated by the UW Digital Collections Center .

- Browse Collections

- Browse UWDC Items

- University of Wisconsin–Madison

- Email/Calendar

- Google Apps

- Loans & Requests

- Poster Printing

- Account Details

- Archives and Special Collections Requests

- Library Room Reservations

Search the UW-Madison Libraries

Article search, through the wormhole with karl marx: science fiction, utopia, and the future of marxism in p.m.'s "weltgeist superstar".

- This article argues that literature in general and science fiction in particular is able to construct alternative spaces beyond the hegemony of Western liberalism espoused by Francis Fukuyama's declaration of the end of history. It examines the little-known novel Weltgeist Superstar (1980) by the anonymous cult author P.M. that was published a decade before Fukuyama's prediction. As a novel about time travel and temporal paradoxes, it proclaims the death of Marxism both through a repetitive and ideological temporality dooming Marxism to a Hegelian fate that foresees the final victory of capitalism. In this way, the novel performs a Derridean hauntology of the various specters of Marx—here, the specter of Hegel that continues to haunt and dictate Marxism. Whereas Fukuyama pronounced the end of all ideological and theoretical alternatives and Derrida sought to revive Marxism through the repetitive temporality of its specters, this novel reasserts the primacy of literature as a utopian space beyond theory.

- View online access

Having Trouble?

If you are having trouble accessing the article, report a problem.

Physical Copies

Publication details.

- JSTOR Arts and Sciences III

- Wiley Online Library Full Journals 2024

- JSTOR Language & Literature Collection

- Alternatives

- Criticism and interpretation

- end of history

- Fukuyama, Francis

- German literature

- Intellectual History

- Literary Genres

- Marx, Karl (1818-1883)

- Marx, Karl (German political theorist)

- Philosophy, Marxist

- Political Attitudes

- Political theorists

- Revolutions

- Science fiction

- Science fiction & fantasy

- science fiction novel

- Social Systems

- temporality

- Weltgeist Superstar

- Widmer, Hans

Additional Information

Library staff details, keyboard shortcuts, available anywhere, available in search results.

What can a Marxist approach tell us about science?

- font size decrease font size increase font size

Richard Clarke considers how a dialectical methodology can help scientists ask the right questions.

‘Science’ and ‘scientific’ can mean at least three different things, including: 1) the ‘knowledge content’ of different disciplines (as in physics, chemistry, biology) about the universe; 2) the processes by which this understanding is acquired (the ‘scientific method’ and wider issues in the philosophy of science); and 3) the relationship of science to society, in particular the organisation, funding and control of research (in the laboratories of universities, by pharma companies or within the ‘military-industrial complex’) and how access to and use of that knowledge is controlled.

All three of these are connected, and it’s easiest to take them in reverse order.

Science is often conceived as ‘pure’ knowledge or ‘facts’, independent of the way these are produced, controlled or used. Marxists would challenge this, pointing out that throughout history, the changing content of scientific knowledge - what are understood at any point in time as facts - are closely related to the social conditions of their production, though in a dialectical rather than a deterministic way. Marx, writing to Engels about Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection commented: ‘It is remarkable how among beasts and plants Darwin recognises his English society with its division of labour, competition, opening up of new markets, ‘inventions’ and Malthusian ‘struggle for existence.’’ (Letter from Marx to Engels, June 18, 1862)

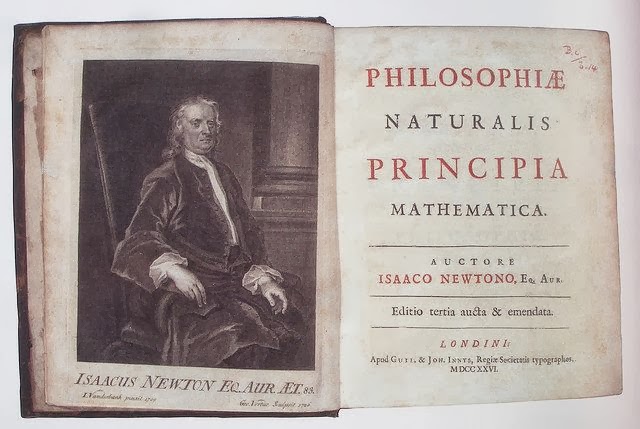

In 1931 a Soviet delegation arrived unannounced at the second International Congress of the History of Science in London, where its leader, Boris Hessen delivered a paper entitled The Socio-Economic Roots of Newton's Principia. Hessen argued that Isaac Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (first published in 1687) - perhaps the single most important scientific treatise of western civilization - was intimately connected to the social conditions of its production. Newton’s Laws of Motion and his ‘discovery’ of gravity were not a gift of divine providence, not (just) the product of individual genius (or the consequence of being hit by a falling apple). They were a response to specific technical problems of early capitalism, in particular the need for improved maritime navigation, the development of new machinery and ballistic weaponry in warfare.

That scientific theories are related to the social context of their production does not of course mean that they are ‘wrong’ or lacking in objectivity. But it challenges the conventional view of science and scientists as autonomous, having an impact ‘on’ society but not being influenced by society. In reality the relationship is two-way; it is dialectical. This approach - emphasising the reciprocal links between science and its social context was later popularised by the communist scientist J D Bernal in his four-volume Science in History , and it is now broadly accepted by the majority of historians of science.

Under capitalism, ‘natural science acts as a direct productive force, continuously invading and transforming all areas of human existence.’ It is one of the principal agents of technological and social change. It can be immensely liberating, but also hugely destructive. From the mid-twentieth century onwards, ‘the twin roles of science as a force of production and of social control have become both dominant and manifest, and […] this transition is linked with a change in the mode of production of scientific knowledge, from essentially craft, to industrialised production.’ (Hilary Rose and Steven Rose, The Incorporation of Science, in The Political Economy of Science. )

Coalbrookdale by Night, by Philip James de Loutherbourg, 1801

Science can be exciting. It is one of the things that separates humans from all other animals. But the mode of production of scientific knowledge has changed since Marx’s day, from essentially craft, to industrialised assembly. Today the daily work of most scientists is routine. Most scientific research is conducted by or funded by commercial organisations. The overwhelming majority of scientists are employees, working (often under short-term contracts) under the direction of their managers on specific problems which are part of a greater whole of which they are often unaware - a situation analogous to the Taylorism of factory work (maximising efficiency by breaking jobs down into simple routine elements) and funded either by external grants or directly by the companies for which they work.

Scientific labour (the work of practising scientists) itself produces ‘use value’ as knowledge, much of which, through patenting or commercial secrecy, is appropriated for profit. The activities of pharmaceutical companies, agricultural research and the nuclear industry all demonstrate the subordination of science to capital, often in particularly oppressive and (socially and environmentally) destructive ways.

And capital makes profit from science not only through its technological applications (from foodstuffs and pharmaceuticals to energy technologies and software systems) but also in other, essentially unproductive ways, from restrictive patents to publishing. In 2010, Elsevier’s scientific publishing arm reported profits of £724m on just over £2bn in turnover – a 36% margin, higher than Apple, Google, or Amazon posted that year. The careers of scientists depend on publishing in ‘reputable’ journals which charge extortionate prices for access.

Marxism also has something to say about the philosophy and methodology of science. Marx and Engels both emphasised the way that science itself moves in a dialectical way from induction to deduction, from analysis to synthesis and from the concrete to the abstract, and back again. For example, induction involves making a generalisation from a set of specific observations. This results in the formulation of an hypothesis (an explanation or prediction) which, if not contradicted by further observation, becomes incorporated in a body of theory. Deduction works the other way around - start with a generalisation (a theory), produce an hypothesis about what will happen in a particular situation, then test this through further observations, sometimes involving experiments. The two processes of induction and deduction are inseparable and lead to a progressive refinement of theory as the best explanation, generally supported by the scientific community, of observations to date.

One of the most influential philosophers of science was (Sir) Karl Popper. Popper emphasised that a ‘scientific’ statement (or theory) is not one that is necessarily ‘true’, but rather one that is framed in such a way that it can be tested (or falsified). For Popper, an anti-communist liberal, Marxism is not ‘scientific’ because it is not falsifiable. However the same criticism also applies to most of the social sciences and indeed to much natural science. Darwinism (the theory of evolution through natural selection) is itself primarily inductive.

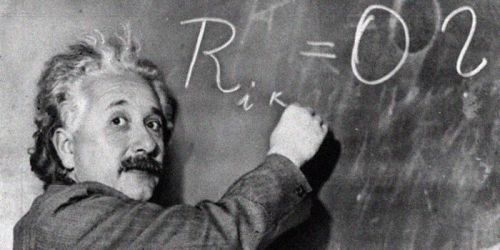

A rather different view of scientific progress was popularised by the philosopher Thomas Kuhn. In his extraordinarily influential The Structure of Scientific Revolutions Kuhn argued against the Popperian notion of science as a gradual orderly progression towards ‘truth’. Most scientists, most of the time, he argued, operate within an unchallenged conceptual framework, or paradigm, filling in bits of a jigsaw or ‘puzzle-solving’ but rarely challenging the overall picture. Periodically, however, anomalies accumulate, ‘normal science’ breaks down and a new paradigm emerges. Examples of such ‘paradigm shifts’ include the Copernican revolution (a heliocentric rather than an earth-centred universe), Darwinian evolution, and Einsteinian relativity theory. Kuhn emphasised that paradigm shifts are not confined to the internal logic of science but involve social and political factors as well.

Kuhn’s work resulted in a surge of interest on the social relations of science — including the rediscovery of Hessen’s paper on Newton a third of a century earlier and of which Kuhn appears to have been unaware. It also chimed with the ‘anti-science swing’ of the 1970s, leading some to argue that science was ‘nothing but’ social relations. Both extremes - the view of science as ‘pure’ knowledge independent of society, but also the argument that science is merely another form of ideology or culture - have always been challenged by Marxists. The questions science asks (and the answers that it gets) are closely related to the way that science is organised, who pays and who profits, as well as to the more general needs of society. But that doesn’t mean that science is necessarily lacking in objectivity (although sometimes this is the case). Scientific knowledge is a special form of knowledge. The scientific method and the knowledge it produces have a relative autonomy.

But a Marxist approach can take us still further in relation to ‘the facts’ of science. The underlying philosophical basis of Marxism, dialectical materialism , is not a magic key to provide the ‘right’ solution to any problem. There have been periods in the not-too-distant history of science where it has been abused, notably during the ‘Lysenko period’ of Soviet genetics. It is, rather, a potentially helpful approach to asking the right questions (and to examining and challenging answers which are put forward by others) – about nature as well as about human society.

The dominant mode of science is reductionist – studying individual parts of a system, isolating one variable at a time and ignoring other aspects. Reductionism is potentially a powerful procedure in science. But of itself it can only provide partial answers to relatively limited questions. Reductionism alone can never provide the whole picture. And in some areas, notably in human biology and psychology, it lends itself to (unintentional or deliberate) abuse. An example is when supposedly ‘scientific’ justifications are put forward for social inequality, discrimination and the status-quo.

This was particularly the case with what came to be known as social Darwinism, pioneered by Herbert Spencer, one of the most influential European intellectuals of the late 19th century, who coined the phrase ‘survival of the fittest’ (never used by Darwin himself) and applied it to human affairs. A free market was the reflection in human society of natural law. Regulation and welfare provision, he argued, should therefore be opposed (he used the phrase ‘There Is No Alternative’ more than a century before Thatcher). Ironically, Spencer’s ashes are interred in Highgate cemetery opposite Karl Marx’s grave.

Science has been used repeatedly since in a similar way. Today sociobiology and evolutionary psychology are still used to justify inequality, racism and sexual discrimination on the basis of supposed inherited biological traits. Competition, aggression, xenophobia are (it is argued) programmed into us from our ancestral past. They are ‘in our genes’. The notion of the ‘selfish gene’ is an example of a reductionist approach which ‘naturalises’ what are essentially social phenomena and fails to look at the relations between different levels of analysis. Sometimes the biases in science are unconscious. Sometimes they are deliberate. Sir Cyril Burt was a hugely influential educational psychologist who ‘proved’ that intelligence was overwhelmingly inherited. His work was used to justify selective schooling and the subordination of black and working class people. His work was always challenged by progressives but it was only after his death in 1971 that it was found to have been fraudulent.

Good science (and major advance) needs to look critically at the evidence for any explanation of phenomena, and also to understand the limits within which those explanations are appropriate. It needs to examine the functions of each part of a complex system but also the interactions between these parts and the way they affect the behaviour of a system as a whole. A dialectical approach in science is valuable both in what Thomas Kuhn called ‘normal science’ but also in the major transformative shifts which change the way that we perceive the world. Many Marxist scientists have found such an approach helpful in their professional work.

An example in the physical sciences is the quantum physicist David Bohm, one of the most significant theoretical physicists of the 20th century. Following his early work on nuclear fission Bohm collaborated with Albert Einstein at Princeton University before being forced to leave the United States because of his links with the Young Communist League and activity in peace movements. At London’s Birkbeck College he showed how entities - from sub-atomic particles to everyday ‘objects’ - can be regarded as ‘semi-autonomous quasi-local features’ of underlying processes, later extending this to the nature of thought and consciousness.

Other notable Marxist physicists include the crystallographer and polymath J D Bernal (also based at Birkbeck), Dorothy Hodgkin (pioneer of three dimensional protein structures such as penicillin and insulin) and the biochemist Joseph Needham (the first Head of the Natural Sciences Section of UNESCO). Perhaps unsurprisingly the most productive applications of a dialectical approach have been in biological science. One of the most prominent was J B S Haldane (originator with the Russian biochemist Alexsandr Oparin of the ‘primordial soup’ theory of the origin of life) who combined his scientific work with popularisation of science and Marxist philosophy. And other scientists (including some who would disclaim the descriptor ‘Marxist’) nevertheless see dialectical materialism as a key guide in their science. An example is Ernst Mayr, one of the most eminent biologists of the 20th century, whose 1977 essay Roots of Dialectical Materialism is a good brief introduction to the subject and its controversies.

More recent conspicuous examples of Marxist scientists include Steven Rose in his work on the relationship between consciousness and the human brain, the evolutionary palaeontologist Stephen Jay Gould (author with Niles Eldredge of the theory of punctated equilibrium), the ecologist Richard Levins (a pioneer of metapopulation theory) and the geneticist Dick Lewontin.

So: a Marxist approach can reveal a good deal about the relation of science to society, and it can also help to illuminate the process whereby scientific knowledge is produced. As far as the knowledge content of science is concerned, Marxism of itself offers no especially privileged insights into the workings of nature - that is the job of science and scientists. But a dialectical methodology is an essential complement to reductionism. And in key areas it can help us question the popular presentation of ‘facts’ which might otherwise be taken on trust. A socialist science has the potential to be a better kind of science. An abbreviated version of this answer was published in the Morning Star in two parts on 18 September and 6 November 2017.

Latest from

- The Bleeding Edge

- Marxism and religion

What Do Marxists Have To Say About Art?

Related items, the quest for the materialist jesus: part 1, the combination, is there a marxist perspective on education.

MIA : Marxists : Marx & Engels : Library : 1848 : Manifesto of the Communist Party : Chapter 3: [German Original]

Chapter III. Socialist and Communist Literature 1. Reactionary Socialism A. Feudal Socialism Owing to their historical position, it became the vocation of the aristocracies of France and England to write pamphlets against modern bourgeois society. In the French Revolution of July 1830, and in the English reform agitation [A] , these aristocracies again succumbed to the hateful upstart. Thenceforth, a serious political struggle was altogether out of the question. A literary battle alone remained possible. But even in the domain of literature the old cries of the restoration period had become impossible. (1) In order to arouse sympathy, the aristocracy was obliged to lose sight, apparently, of its own interests, and to formulate their indictment against the bourgeoisie in the interest of the exploited working class alone. Thus, the aristocracy took their revenge by singing lampoons on their new masters and whispering in his ears sinister prophesies of coming catastrophe. In this way arose feudal Socialism: half lamentation, half lampoon; half an echo of the past, half menace of the future; at times, by its bitter, witty and incisive criticism, striking the bourgeoisie to the very heart’s core; but always ludicrous in its effect, through total incapacity to comprehend the march of modern history. The aristocracy, in order to rally the people to them, waved the proletarian alms-bag in front for a banner. But the people, so often as it joined them, saw on their hindquarters the old feudal coats of arms, and deserted with loud and irreverent laughter. One section of the French Legitimists and “ Young England ” exhibited this spectacle. In pointing out that their mode of exploitation was different to that of the bourgeoisie, the feudalists forget that they exploited under circumstances and conditions that were quite different and that are now antiquated. In showing that, under their rule, the modern proletariat never existed, they forget that the modern bourgeoisie is the necessary offspring of their own form of society. For the rest, so little do they conceal the reactionary character of their criticism that their chief accusation against the bourgeois amounts to this, that under the bourgeois ré gime a class is being developed which is destined to cut up root and branch the old order of society. What they upbraid the bourgeoisie with is not so much that it creates a proletariat as that it creates a revolutionary proletariat. In political practice, therefore, they join in all coercive measures against the working class; and in ordinary life, despite their high-falutin phrases, they stoop to pick up the golden apples dropped from the tree of industry, and to barter truth, love, and honour, for traffic in wool, beetroot-sugar, and potato spirits. (2) As the parson has ever gone hand in hand with the landlord, so has Clerical Socialism with Feudal Socialism. Nothing is easier than to give Christian asceticism a Socialist tinge. Has not Christianity declaimed against private property, against marriage, against the State? Has it not preached in the place of these, charity and poverty, celibacy and mortification of the flesh, monastic life and Mother Church? Christian Socialism is but the holy water with which the priest consecrates the heart-burnings of the aristocrat. B. Petty-Bourgeois Socialism The feudal aristocracy was not the only class that was ruined by the bourgeoisie, not the only class whose conditions of existence pined and perished in the atmosphere of modern bourgeois society. The medieval burgesses and the small peasant proprietors were the precursors of the modern bourgeoisie. In those countries which are but little developed, industrially and commercially, these two classes still vegetate side by side with the rising bourgeoisie. In countries where modern civilisation has become fully developed, a new class of petty bourgeois has been formed, fluctuating between proletariat and bourgeoisie, and ever renewing itself as a supplementary part of bourgeois society. The individual members of this class, however, are being constantly hurled down into the proletariat by the action of competition, and, as modern industry develops, they even see the moment approaching when they will completely disappear as an independent section of modern society, to be replaced in manufactures, agriculture and commerce, by overlookers, bailiffs and shopmen. In countries like France, where the peasants constitute far more than half of the population, it was natural that writers who sided with the proletariat against the bourgeoisie should use, in their criticism of the bourgeois régime , the standard of the peasant and petty bourgeois, and from the standpoint of these intermediate classes, should take up the cudgels for the working class. Thus arose petty-bourgeois Socialism. Sismondi was the head of this school, not only in France but also in England. This school of Socialism dissected with great acuteness the contradictions in the conditions of modern production. It laid bare the hypocritical apologies of economists. It proved, incontrovertibly, the disastrous effects of machinery and division of labour; the concentration of capital and land in a few hands; overproduction and crises; it pointed out the inevitable ruin of the petty bourgeois and peasant, the misery of the proletariat, the anarchy in production, the crying inequalities in the distribution of wealth, the industrial war of extermination between nations, the dissolution of old moral bonds, of the old family relations, of the old nationalities. In its positive aims, however, this form of Socialism aspires either to restoring the old means of production and of exchange, and with them the old property relations, and the old society, or to cramping the modern means of production and of exchange within the framework of the old property relations that have been, and were bound to be, exploded by those means. In either case, it is both reactionary and Utopian. Its last words are: corporate guilds for manufacture; patriarchal relations in agriculture. Ultimately, when stubborn historical facts had dispersed all intoxicating effects of self-deception, this form of Socialism ended in a miserable fit of the blues. C. German or “True” Socialism The Socialist and Communist literature of France, a literature that originated under the pressure of a bourgeoisie in power, and that was the expressions of the struggle against this power, was introduced into Germany at a time when the bourgeoisie, in that country, had just begun its contest with feudal absolutism. German philosophers, would-be philosophers, and beaux esprits (men of letters) , eagerly seized on this literature, only forgetting, that when these writings immigrated from France into Germany, French social conditions had not immigrated along with them. In contact with German social conditions, this French literature lost all its immediate practical significance and assumed a purely literary aspect. Thus, to the German philosophers of the Eighteenth Century, the demands of the first French Revolution were nothing more than the demands of “Practical Reason” in general, and the utterance of the will of the revolutionary French bourgeoisie signified, in their eyes, the laws of pure Will, of Will as it was bound to be, of true human Will generally. The work of the German literati consisted solely in bringing the new French ideas into harmony with their ancient philosophical conscience, or rather, in annexing the French ideas without deserting their own philosophic point of view. This annexation took place in the same way in which a foreign language is appropriated, namely, by translation. It is well known how the monks wrote silly lives of Catholic Saints over the manuscripts on which the classical works of ancient heathendom had been written. The German literati reversed this process with the profane French literature. They wrote their philosophical nonsense beneath the French original. For instance, beneath the French criticism of the economic functions of money, they wrote “Alienation of Humanity”, and beneath the French criticism of the bourgeois state they wrote “Dethronement of the Category of the General”, and so forth. The introduction of these philosophical phrases at the back of the French historical criticisms, they dubbed “Philosophy of Action”, “True Socialism”, “German Science of Socialism”, “Philosophical Foundation of Socialism”, and so on. The French Socialist and Communist literature was thus completely emasculated. And, since it ceased in the hands of the German to express the struggle of one class with the other, he felt conscious of having overcome “French one-sidedness” and of representing, not true requirements, but the requirements of Truth; not the interests of the proletariat, but the interests of Human Nature, of Man in general, who belongs to no class, has no reality, who exists only in the misty realm of philosophical fantasy. This German socialism, which took its schoolboy task so seriously and solemnly, and extolled its poor stock-in-trade in such a mountebank fashion, meanwhile gradually lost its pedantic innocence. The fight of the Germans, and especially of the Prussian bourgeoisie, against feudal aristocracy and absolute monarchy, in other words, the liberal movement, became more earnest. By this, the long-wished for opportunity was offered to “True” Socialism of confronting the political movement with the Socialist demands, of hurling the traditional anathemas against liberalism, against representative government, against bourgeois competition, bourgeois freedom of the press, bourgeois legislation, bourgeois liberty and equality, and of preaching to the masses that they had nothing to gain, and everything to lose, by this bourgeois movement. German Socialism forgot, in the nick of time, that the French criticism, whose silly echo it was, presupposed the existence of modern bourgeois society, with its corresponding economic conditions of existence, and the political constitution adapted thereto, the very things those attainment was the object of the pending struggle in Germany. To the absolute governments, with their following of parsons, professors, country squires, and officials, it served as a welcome scarecrow against the threatening bourgeoisie. It was a sweet finish, after the bitter pills of flogging and bullets, with which these same governments, just at that time, dosed the German working-class risings. While this “True” Socialism thus served the government as a weapon for fighting the German bourgeoisie, it, at the same time, directly represented a reactionary interest, the interest of German Philistines. In Germany, the petty-bourgeois class, a relic of the sixteenth century, and since then constantly cropping up again under the various forms, is the real social basis of the existing state of things. To preserve this class is to preserve the existing state of things in Germany. The industrial and political supremacy of the bourgeoisie threatens it with certain destruction — on the one hand, from the concentration of capital; on the other, from the rise of a revolutionary proletariat. “True” Socialism appeared to kill these two birds with one stone. It spread like an epidemic. The robe of speculative cobwebs, embroidered with flowers of rhetoric, steeped in the dew of sickly sentiment, this transcendental robe in which the German Socialists wrapped their sorry “eternal truths”, all skin and bone, served to wonderfully increase the sale of their goods amongst such a public. And on its part German Socialism recognised, more and more, its own calling as the bombastic representative of the petty-bourgeois Philistine. It proclaimed the German nation to be the model nation, and the German petty Philistine to be the typical man. To every villainous meanness of this model man, it gave a hidden, higher, Socialistic interpretation, the exact contrary of its real character. It went to the extreme length of directly opposing the “brutally destructive” tendency of Communism, and of proclaiming its supreme and impartial contempt of all class struggles. With very few exceptions, all the so-called Socialist and Communist publications that now (1847) circulate in Germany belong to the domain of this foul and enervating literature. (3) 2. Conservative or Bourgeois Socialism A part of the bourgeoisie is desirous of redressing social grievances in order to secure the continued existence of bourgeois society. To this section belong economists, philanthropists, humanitarians, improvers of the condition of the working class, organisers of charity, members of societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals, temperance fanatics, hole-and-corner reformers of every imaginable kind. This form of socialism has, moreover, been worked out into complete systems. We may cite Proudhon’s Philosophie de la Misère as an example of this form. The Socialistic bourgeois want all the advantages of modern social conditions without the struggles and dangers necessarily resulting therefrom. They desire the existing state of society, minus its revolutionary and disintegrating elements. They wish for a bourgeoisie without a proletariat. The bourgeoisie naturally conceives the world in which it is supreme to be the best; and bourgeois Socialism develops this comfortable conception into various more or less complete systems. In requiring the proletariat to carry out such a system, and thereby to march straightway into the social New Jerusalem, it but requires in reality, that the proletariat should remain within the bounds of existing society, but should cast away all its hateful ideas concerning the bourgeoisie. A second, and more practical, but less systematic, form of this Socialism sought to depreciate every revolutionary movement in the eyes of the working class by showing that no mere political reform, but only a change in the material conditions of existence, in economical relations, could be of any advantage to them. By changes in the material conditions of existence, this form of Socialism, however, by no means understands abolition of the bourgeois relations of production, an abolition that can be affected only by a revolution, but administrative reforms, based on the continued existence of these relations; reforms, therefore, that in no respect affect the relations between capital and labour, but, at the best, lessen the cost, and simplify the administrative work, of bourgeois government. Bourgeois Socialism attains adequate expression when, and only when, it becomes a mere figure of speech. Free trade: for the benefit of the working class. Protective duties: for the benefit of the working class. Prison Reform: for the benefit of the working class. This is the last word and the only seriously meant word of bourgeois socialism. It is summed up in the phrase: the bourgeois is a bourgeois — for the benefit of the working class. 3. Critical-Utopian Socialism and Communism We do not here refer to that literature which, in every great modern revolution, has always given voice to the demands of the proletariat, such as the writings of Babeuf and others. The first direct attempts of the proletariat to attain its own ends, made in times of universal excitement, when feudal society was being overthrown, necessarily failed, owing to the then undeveloped state of the proletariat, as well as to the absence of the economic conditions for its emancipation, conditions that had yet to be produced, and could be produced by the impending bourgeois epoch alone. The revolutionary literature that accompanied these first movements of the proletariat had necessarily a reactionary character. It inculcated universal asceticism and social levelling in its crudest form. The Socialist and Communist systems, properly so called, those of Saint-Simon , Fourier , Owen , and others, spring into existence in the early undeveloped period, described above, of the struggle between proletariat and bourgeoisie (see Section 1. Bourgeois and Proletarians ). The founders of these systems see, indeed, the class antagonisms, as well as the action of the decomposing elements in the prevailing form of society. But the proletariat, as yet in its infancy, offers to them the spectacle of a class without any historical initiative or any independent political movement. Since the development of class antagonism keeps even pace with the development of industry, the economic situation, as they find it, does not as yet offer to them the material conditions for the emancipation of the proletariat. They therefore search after a new social science, after new social laws, that are to create these conditions. Historical action is to yield to their personal inventive action; historically created conditions of emancipation to fantastic ones; and the gradual, spontaneous class organisation of the proletariat to an organisation of society especially contrived by these inventors. Future history resolves itself, in their eyes, into the propaganda and the practical carrying out of their social plans. In the formation of their plans, they are conscious of caring chiefly for the interests of the working class, as being the most suffering class. Only from the point of view of being the most suffering class does the proletariat exist for them. The undeveloped state of the class struggle, as well as their own surroundings, causes Socialists of this kind to consider themselves far superior to all class antagonisms. They want to improve the condition of every member of society, even that of the most favoured. Hence, they habitually appeal to society at large, without the distinction of class; nay, by preference, to the ruling class. For how can people, when once they understand their system, fail to see in it the best possible plan of the best possible state of society? Hence, they reject all political, and especially all revolutionary action; they wish to attain their ends by peaceful means, necessarily doomed to failure, and by the force of example, to pave the way for the new social Gospel. Such fantastic pictures of future society, painted at a time when the proletariat is still in a very undeveloped state and has but a fantastic conception of its own position, correspond with the first instinctive yearnings of that class for a general reconstruction of society. But these Socialist and Communist publications contain also a critical element. They attack every principle of existing society. Hence, they are full of the most valuable materials for the enlightenment of the working class. The practical measures proposed in them — such as the abolition of the distinction between town and country, of the family, of the carrying on of industries for the account of private individuals, and of the wage system, the proclamation of social harmony, the conversion of the function of the state into a mere superintendence of production — all these proposals point solely to the disappearance of class antagonisms which were, at that time, only just cropping up, and which, in these publications, are recognised in their earliest indistinct and undefined forms only. These proposals, therefore, are of a purely Utopian character. The significance of Critical-Utopian Socialism and Communism bears an inverse relation to historical development. In proportion as the modern class struggle develops and takes definite shape, this fantastic standing apart from the contest, these fantastic attacks on it, lose all practical value and all theoretical justification. Therefore, although the originators of these systems were, in many respects, revolutionary, their disciples have, in every case, formed mere reactionary sects. They hold fast by the original views of their masters, in opposition to the progressive historical development of the proletariat. They, therefore, endeavour, and that consistently, to deaden the class struggle and to reconcile the class antagonisms. They still dream of experimental realisation of their social Utopias, of founding isolated “phalansteres”, of establishing “Home Colonies”, or setting up a “Little Icaria” (4) — duodecimo editions of the New Jerusalem — and to realise all these castles in the air, they are compelled to appeal to the feelings and purses of the bourgeois. By degrees, they sink into the category of the reactionary [or] conservative Socialists depicted above, differing from these only by more systematic pedantry, and by their fanatical and superstitious belief in the miraculous effects of their social science. They, therefore, violently oppose all political action on the part of the working class; such action, according to them, can only result from blind unbelief in the new Gospel. The Owenites in England, and the Fourierists in France, respectively, oppose the Chartists and the Réformistes . Chapter 4: Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Existing Opposition Parties (1) Not the English Restoration (1660-1689), but the French Restoration (1814-1830). [Note by Engels to the English edition of 1888.] (2) This applies chiefly to Germany, where the landed aristocracy and squirearchy have large portions of their estates cultivated for their own account by stewards, and are, moreover, extensive beetroot-sugar manufacturers and distillers of potato spirits. The wealthier British aristocracy are, as yet, rather above that; but they, too, know how to make up for declining rents by lending their names to floaters or more or less shady joint-stock companies. [Note by Engels to the English edition of 1888.] (3) The revolutionary storm of 1848 swept away this whole shabby tendency and cured its protagonists of the desire to dabble in socialism. The chief representative and classical type of this tendency is Mr Karl Gruen. [Note by Engels to the German edition of 1890.] (4) Phalanstéres were Socialist colonies on the plan of Charles Fourier; Icaria was the name given by Cabet to his Utopia and, later on, to his American Communist colony. [Note by Engels to the English edition of 1888.] “Home Colonies” were what Owen called his Communist model societies. Phalanstéres was the name of the public palaces planned by Fourier. Icaria was the name given to the Utopian land of fancy, whose Communist institutions Cabet portrayed. [Note by Engels to the German edition of 1890.] [A] A reference to the movement for a reform of the electoral law which, under the pressure of the working class, was passed by the British House of Commons in 1831 and finally endorsed by the House of Lords in June, 1832. The reform was directed against monopoly rule of the landed and finance aristocracy and opened the way to Parliament for the representatives of the industrial bourgeoisie. Neither workers nor the petty-bourgeois were allowed electoral rights, despite assurances they would. Table of Contents: Manifesto of the Communist Party | Marx-Engels Archive

Marx�s Crisis of Capitalism

From Sociocultural Systems: Principles of Structure and Change .

Agriculture too is transformed through science to become an exploitive relationship in which the crops and people are treated as commodities; millions are removed from the land as corporate farms replace the family farms of the past. In effect capital uses science and technology to transform agri culture into agri business , in the process not only exploiting the worker but exploiting and ultimately destroying the natural fertility of the land as well (8524-8533). [3]

In addition to the booms and busts of capitalism that swing wider as capitalism evolves there is a constant churning of employment as machines replace men in one industry after another, throwing thousands out of work, thus swamping the labor market and lowering the cost of labor (7407-7420). [5] In all of this the labourers suffer. Mass production, machine technology, and economies of scale will increasingly be applied to all economic activities; unemployment and misery for many men and women results (11676-11684). [6] As capitalism develops the system must necessarily create enormous differences in wealth and power. The social problems it creates in its wake of boom and bust�of unemployment and under employment, of poverty amidst affluence will continue to mount. The vast majority of people will fall into the lower classes; the wealthy will become richer but ever fewer in number (11665-11681). [7]

Over the course of its evolution, capitalism brings into being a working class (the proletariat) consisting of those who have a fundamental antagonism to the owners of capital. The control of the state by the wealthy makes it ineffective in fundamental reform of the system and leads to the passage of laws favoring their interests and incurring the wrath of a growing number of workers. �The executive of the modern State is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie� (Marx and Engels 1848, 2). Now highly urbanized and thrown together in factories and workplaces by the forces of capital, the workers of the world increasingly recognize that they are being exploited, that their needs are not being met by the present political-economic system. The monopoly of capital is preventing the production of goods and services for the many. Needed social goods and services are not being produced because there is no profit in it for the capitalists who control the means of production. Exorbitant wealth for the few amid widespread poverty for the many will become the norm.

As the crisis mount , Marx argues, the proletariat will become more progressive, though governments will be blocked from providing real structural change because of the dominance of the capitalists and their organization, money, and power. In time, the further development of production becomes impossible within a capitalist framework and this framework becomes the target of revolt. Eventually, Marx says, these contradictions of capitalism will produce a revolutionary crisis.

Along with the constantly diminishing number of the magnates of capital, who usurp and monopolize all advantages of this process of transformation, grows the mass of misery, oppression, slavery, degradation, exploitation; but with this too grows the revolt of the working-class, a class always increasing in numbers, and disciplined, united, organized by the very mechanism of the process of capitalist production itself. The monopoly of capital becomes a fetter upon the mode of production, which has sprung up and flourished along with, and under it. Centralization of the means of production and socialization of labor at last reach a point where they become incompatible with their capitalist integument. Thus integument is burst asunder. The knell of capitalist private property sounds. The expropriators are expropriated (Marx 1867/1887, 14204-14210).

With the revolution the production processes that were developed under the spur of capital accumulation will be harnessed to serve broad human needs rather than the needs of a few capitalists. For example, p harmaceutical companies could focus on developing drugs to fight the tuberculosis or malaria, diseases that kill millions in Africa. However, far more profit can be made by developing additional drugs to treat impotence and baldness (Bakan 2004, 49). Thus the need for profit keeps drug companies from serving broader human needs. In the Communist Manifesto Marx and Engels (1848) write: �We have seen above, that the first step in the revolution by the working class, is to raise the proletariat to the position of ruling as to win the battle of democracy. The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degrees, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total of productive forces as rapidly as possible� (14).

For a more extensive discussion of Marx�s theories refer to Macro Social Theory by Frank W. Elwell. Also see Sociocultural Systems: Principles of Structure and Change to learn how his insights contribute to a more complete understanding of modern societies.

References:

Elwell, Frank W. 2013. Sociocultural Systems: Principles of Structure and Change . Alberta: Athabasca University Press.

Engels, Frederick. (1847) 1999. �The Principles of Communism . � Translated by Paul Sweezy. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/11/prin-com.htm .

Marx, Karl. 1867/1887. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. 1, The Process of Production of Capital. Edited by Frederick Engels. Translated by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling. Public Domain Books, Kindle Edition (2008-11-19). Originally published as Das Kapital: Kritik der politischen �konomie, vol. 1.

Marx, Karl, and Frederick Engels. 1848. The Communist Manifesto. Edited and translated by Frederick Engels. Public Domain Books, Kindle Edition, (2005). Originally published as Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei.

Referencing this Site:

Marx's Crisis of Capitalism is copyrighted by Athabasca University Press and is for educational use only. Should you wish to quote from this material the format should be as follows:

Elwell, Frank, 2013, "Marx's Crisis of Capitalism ," Retrieved August 28, 2013 [use actual date], http://www.faculty.rsu.edu/~felwell/Theorists/Essays/Marx5.htm

- Signup for G K Online test for 2 years

- 1 lakh+ Questions

- General Knowledge practice

- Current Affairs Q & A in Quiz format

- Daily Current Affairs News

- Get Instant news updates

- Anthropology notes

- Management notes

- Current affairs Digest

Sociology App

- Basic Concepts

- Anthropology

- Automation Society

- Branches of Sociology

- Census of India

- Civil Society

- Dalit Movement

- Economy and Society

- Environment and Sociology

- Ethnomethodology

- Folkways And Mores

- Indian Society

- Indian Thinkers

- Individual and Society

- Industrial and Urban Society

- Introduction To Sociology

- International Economy

- Market as a social institution

- Marriage, Family & Kinship

- Nation Community

- Neo Positivism

- Organization and Individual

- People's Participation

- Personality

- Phenomenology

- Political Modernization

- Political Processes

- Political System

- Post Modernism

- Post Structuralism

- Public Opinion

- Research Method & Statistics

- Rural Sociology

- Science, Technology

- Social Action

- Social Change

- Social Control

- Social Demography

- Sociology of Fashion

- Social Inequality

- Social Justice

- Social Mobility

- Social Movements

- Sociology News

- Social Pathology

- Social Problems

- Social Structure

- Social Stratification

- Sociology of Law

- Sociology of Social Media

- Sociology of Development

- Social Relationship

- Theoretical Perspectives

- Tribal Society

- Interest and Attitude

- Neo Functionalism

- Neo-Marxism

- Weaker Section & Minorities

- Women And Society

- Symbolic Interactionism

- Jurisprudence

- Sociology Of Environment

- Sir Edward Evans Pritchard

- Ruth Benedict

- Margaret Mead

- B. Malinowski

- Alfred Schultz

- Herbert Marcuse

- Edmund Leach

- Ralph Linton

- Peter M. Blau

- Auguste Comte

- Emile Durkheim

- Herbert Spencer

- Karl Mannheim

- Sigmund Freud

- Pitirim Sorokin

- Talcott Parsons

- Ferdinand Tonnies

- Thomas Hobbes

- Sir Edward Burnett Taylor

- Karl Polyani

- Alfred Louis Kroeber

- Erving Goffman

- James George Frazer

- Ralph Dahrendorf

- Raymond Firth

- Radcliffe Brown

- Thomas Kuhn

- Poverty Line Debate

- UN Summit on Non- Communicable Diseases

- UN Summit on Non- UN Report on Domestic Violence

- New Women of Tomorrow:Study by Nielsen

- World Population Projections

- Status of Healthcare Services in Bihar

- HIV/AIDS and Mobility in South Asia- UNDP Report 2010

- Levels and Trends in Child Mortality

- India's Development Report Card vis-a-vis MDG

- Sex Ratio in India

- Urban Slum Population

- Short Notes

- Chicago School of Sociology

- Harriet Martineau(1802-876)

- Power of Sociology

- Why we need sociology

- The Sociological Imagination ( 1959)

- Theories of Socialization

- Street Corner Society

- Research Tools

- The social construction of Reality

- Feminization of Poverty

- The Politics of Information

- Global Stratification

- Population and Urbanization

- Sociological Perspectives on Health and Illness

- Sociological Perspectives

- Scientific Method in Sociological Research

- Research Designs in Sociology

- What we need to know about the Gender

- Statistics and Graphs in Sociology

- Mass Media and Communications

- Rites and Secularization

- Caste System

- Communalism and Secularism

- Social Institution

- Social Thinkers

- Edward Burnett Taylor

- Karl Marx Supply

- Office supply

Your Article Library

Karl marx: read the essay on karl marx.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Karl Marx was one of the greatest revolutionaries of the nineteenth century. He initiated the historical dimension to an understanding of society, culture and economics. He created the concept of ideology in the sense of beliefs that shape and control social actions, analyzed the fundamental nature of class as a mechanism of governance and social interaction. His thought and action, during the span of four decades, changed the course of history in Europe. While his friend and collaborator Frederick Engels accompanied Marx in his social adventures, Communism is identified with Marx alone.

Hence, its description as Marxism is widely accepted. Further, the basic thrust of Marxism is to reform and update socialism. In doing so, Marx borrowed certain concepts from his teacher and political philosopher, Hegel. Communism is also popularized as the scientific socialism.

Marxism had evoked prompt response in both the protagonists as well as antagonists of this ideology. In view of basing its arguments on the analysis of capitalism, Marxism appeared as its antidote, and aimed at establishing scientific socialism in any advanced capitalist state.

A thorough study of Marxism makes one believe that the capitalism would be replaced by socialism. For, the basic premises of Marxism are put forward, on a rational and logical format. And, as Marx observed, ‘the philosophers of the world have interpreted it in many ways, but the point, however, is to change it’.

Hence, the mission and goal of Marxism is to change the existing socio-economic order in any society, more so in the capitalist one. That, of course, is possible if the party based on the principles of Marxism is founded on and undertakes the task of a revolution. In other words, Marxism is not just a philosophy but also an action-oriented ideology.

Background :

Further, the fascinating thing about Marxism is that it decries all hitherto existing ideologies as false consciousness of social reality and offers an ideology of its own. Marx’s ideology begins with his criticism of Feuerbach’s Essence of Christianity, wherein he denounced the significance of religious myths in understanding the reality of man’s life.

Marx carried his point further in his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts wherein he observed that man is the sole object of ultimate value and that the distinctly human quality is reason or consciousness. Later on, in his Thesis on Feuerbach, he emphasized the practical nature of thought and denied the importance of unpractical thinking. To him, it is the thought or consciousness that can change the world. And, the consciousness is governed by the conditions of objective reality. To quote Marx:

Man’s ideas, views and conceptions, in one word, man’s consciousness, changes with every change in the conditions of his material existence, in his social relations and in his social life.

However, Marx criticized bourgeois ideology as false consciousness and also linked it up with the notion of class domination. In his perception, the German thinkers failed to realize the fundamental advance made by the materialist philosophy. Marx believed that the ideology is integrally connected with the interests of the ruling class.

Hence, the ideology of the bourgeoisie is the programme of the capitalistic expansion and power. Further, the system of ideas that tends to justify and further the aims of the ruling class is the predominant ideas of that age. For, the ruling class can control all the products, be they goods or ideas.

In other words, the main function of the ideology is justification, not explanation. Ideology supports class interests. The interest of a ruling class is the maintenance of its political and economic power. Hence, if the ideology of the ruling class is being used to spread false consciousness, the working class can develop its ideology and overthrow the ruling class in the proletarian revolution.

As part of praxis, the Marxist ideology, having been implemented in Russia, China and many countries quite successfully, dominated at least till the collapse of the Soviet Union. Despite some setbacks, Marxist ideology certainly evokes positive attention even today. While its practitioners might have failed in comprehending its basic principles and in the application of it, the hopes it created in the vast masses the world over, particularly in the third world, are long lasting.

Meanwhile, there emerged many variants of Marxism, revised forms as per the conditions of different countries, which are also put to tests, every now and then. In any case, progressive ideologies are those that help the state and government in improving the living conditions of the people in a given society.

Related Articles:

- Marx’s Ideas on Dialectical Materialism

- Marx’s Theory of Historical Materialism

No comments yet.

Leave a reply click here to cancel reply..

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

Marxian Economics: Definition, Theories, Vs. Classical Economics

Daniel Liberto is a journalist with over 10 years of experience working with publications such as the Financial Times, The Independent, and Investors Chronicle.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/daniel_liberto-5bfc2715c9e77c0051432901.jpg)

What Is Marxian Economics?

Marxian economics is a school of economic thought based on the work of 19th-century economist and philosopher Karl Marx .

Marxian economics, or Marxist economics, focuses on the role of labor in the development of an economy and is critical of the classical approach to wages and productivity developed by Adam Smith . Marx argued that the specialization of the labor force, coupled with a growing population, pushes wages down, adding that the value placed on goods and services does not accurately account for the true cost of labor.

Key Takeaways

- Marxian economics is a school of economic thought based on the work of 19th-century economist and philosopher Karl Marx.

- Marx claimed there are two major flaws in capitalism that lead to exploitation: the chaotic nature of the free market and surplus labor.

- He argued that the specialization of the labor force, coupled with a growing population, pushes wages down, adding that the value placed on goods and services does not accurately account for the true cost of labor.

- Eventually, he predicted that capitalism will lead more people to get relegated to worker status, sparking a revolution and production being turned over to the state.

Understanding Marxian Economics

Much of Marxian economics is drawn from Karl Marx's seminal work "Das Kapital," his magnum opus first published in 1867. In the book, Marx described his theory of the capitalist system, its dynamism, and its tendencies toward self-destruction.

Much of Das Kapital spells out Marx’s concept of the “surplus value” of labor and its consequences for capitalism. According to Marx, it was not the pressure of labor pools that drove wages to the subsistence level but rather the existence of a large army of unemployed, which he blamed on capitalists. He maintained that within the capitalist system, labor was a mere commodity that could gain only subsistence wages.

Capitalists, however, could force workers to spend more time on the job than was necessary to earn their subsistence and then appropriate the excess product, or surplus value, created by the workers. In other words, Marx argued that workers create value through their labor but are not properly compensated. Their hard work, he said, is exploited by the ruling classes, who generate profits not by selling their products at a higher price but by paying staff less than the value of their labor.

Marx claimed there are two major flaws inherent in capitalism that lead to exploitation: the chaotic nature of the free market and surplus labor.

Marxian Economics vs. Classical Economics

Marxian economics is a rejection of the classical view of economics developed by economists such as Adam Smith. Smith and his peers believed that the free market, an economic system powered by supply and demand with little or no government control, and an onus on maximizing profit, automatically benefits society.

Marx disagreed, arguing that capitalism consistently only benefits a select few. Under this economic model, he argued that the ruling class becomes richer by extracting value out of cheap labor provided by the working class.

In contrast to classical approaches to economic theory, Marx’s favored government intervention. Economic decisions, he said, should not be made by producers and consumers and instead ought to be carefully managed by the state to ensure that everyone benefits.

He predicted that capitalism would eventually destroy itself as more people get relegated to worker status, leading to a revolution and production being turned over to the state.

Special Considerations

Marxian economics is considered separate from Marxism , even if the two ideologies are closely related. Where it differs is that it focuses less on social and political matters. More broadly, Marxian economic principles clash with the virtues of capitalist pursuits.

During the first half of the twentieth century, with the Bolshevik revolution in Russia and the spread of communism throughout Eastern Europe, it seemed the Marxist dream had finally and firmly taken root.

However, that dream collapsed before the century had ended. The people of Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Romania, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Albania, and the USSR rejected Marxist ideology and entered a remarkable transition toward private property rights and a market-exchange based system.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/marxism-final-6a8c13e1cbbf42658aa2c06266eb82d3.png)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Home — Essay Samples — Philosophy — Karl Marx — Karl Marx and Labor

Karl Marx and Labor

- Categories: Karl Marx

About this sample

Words: 727 |

Published: Aug 14, 2018

Words: 727 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Philosophy

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3.5 pages / 1553 words

3.5 pages / 1504 words

11 pages / 1713 words

1.5 pages / 717 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

The assertion that "religion is the opiate of the masses" is a provocative statement famously attributed to Karl Marx, the influential philosopher and political theorist. Marx's view on religion, often paraphrased as a means of [...]

Karl Marx, a German philosopher, economist, and revolutionary socialist, is known for his groundbreaking contributions to the field of sociology, particularly his conflict theory. Marx’s conflict theory provides a framework for [...]

Karl Marx introduces the trinity formula to us near the end of the work. One interpretation of the trinity formula is that it's a description of how capital (the collective value of the means of production), land (arable [...]

Marx’s and Engels’ book talks extensively from the Conflict perspective, which deals with the Proletariat and the Bourgeoisie. The purpose of it is to expose the viewpoint and workings of the Communist Party. The Proletariat is [...]

There can be no doubt over the wide-ranging influence of Karl Marx’s theories on sociology and political thought. His concept of communism overcoming the socioeconomic pitfalls of capitalism has not been a theory that has seen [...]

Karl Marx’s “The Communist Manifesto” informed the world about the political and economic conflict of the proletariat against the bourgeois and by extension, the aristocracy. Marx disputes that the proletariat should possess the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

The Catholic Case for Communism

“It is when the Communists are good that they are dangerous.”

That is how Dorothy Day begins an article in America , published just before the launch of the Catholic Worker on May Day in 1933. In contrast to the reactions of many Catholics of the time, Day painted a sympathetic, if critical view of the communists she encountered in Depression-era New York City. Her deep personalism allowed her to see the human stories through the ideological struggle; and yet she concluded that Catholicism and communism were not only incompatible, but mutual threats. A whole Cold War has passed since her reflection, and a few clarifying notes are now worthwhile.

Communists are attracted to communism by their goodness, Day argued, that unerasable quality of the good that can be found within and outside the church alike, woven into our very nature. It might have been an easier thing to say back in 1933, when American communists were well known to the general public for putting their lives on the line to support striking workers, but it was also the kind of thing that could land you in a lot of trouble, not least in the Catholic Church.

By affirming the goodness that drives so many communists then and now, Day aimed to soften the perceptions of Catholics who were more comfortable with villainous caricatures of the communists of their era than with more challenging depictions of them as laborers for peace and economic justice. Most people who join communist parties and movements, Day rightly noted, are motivated not by some deep hatred toward God or frothing anti-theism, but by an aspiration for a world liberated from a political economy that demands vast exploitation of the many for the comfort of a few.

[Matt Malone, S.J.: Why we published an essay sympathetic to communism]

But in her attempt to create sympathy for the people attracted to communism and to overcome a knee-jerk prejudice against them, Day needlessly perpetuated two other prejudices against communism. First, she said that under all the goodness that draws people to communism, the movement is, in the final analysis, a program “with the distinct view of tearing down the church.”

Then, talking about a young communist in her neighborhood who was killed after being struck by a brick thrown by a Trotskyite, she concluded that young people who follow the goodness in their hearts that may lead them to communism are not fully aware of what it is they are participating in—even at the risk of their lives. In other words, we should hate the communism but love the communist.

Though Day’s sympathetic criticism of communism is in many ways commendable, nearly a century of history shows there is much more to the story than these two judgments suggest. Communist political movements the world over have been full of unexpected characters, strange developments and more complicated motivations than a desire to undo the church; and even through the challenges of the 20th century, Catholics and communists have found natural reasons to offer one another a sign of peace.

A Complicated History

Christianity and communism have obviously had a complicated relationship. That adjective “complicated” will surely cause some readers to roll their eyes. Communist states and movements have indeed persecuted religious people at different moments in history. At the same time, Christians have been passionately represented in communist and socialist movements around the world. And these Christians, like their atheist comrades, are communists not because they misunderstand the final goals of communism but because they authentically understand the communist ambition of a classless society.

“From each according to ability, to each according to need,” Marx summarizes in “ Critique of the Gotha Program ,” a near echo of Luke’s description of the early church in Acts 4:35 and 11:29 . Perhaps it was Day, not her young communist neighbor, who misunderstood communism.

It is true that Marx, Engels, Lenin and a number of other major communists were committed Enlightenment thinkers, atheists who sometimes assumed religion would fade away in the bright light of scientific reason, and at other times advocated propagandizing against it (though not, as Lenin argued, in a way that would divide the movement against capitalism, the actual opponent). That should not be so scandalous in itself. They are hardly alone as modern atheists, and their atheism is understandable, when Christianity has so often been a force allied to the ruling powers that exploit the poor. Catholics have found plenty of philosophical resources in non-Christian sources in the past; why not moderns?

Despite and beyond theoretical differences, priests like Herbert McCabe, O.P., Ernesto and Fernando Cardenal , S.J., Frei Betto , O.P., Camilo Torres and many other Catholics—members of the clergy, religious and laypeople—have been inspired by communists and in many places contributed to communist and communist-influenced movements as members. Some still do—for example in the Philippines, where the “Christians for National Liberation,” an activist group first organized by nuns, priests and exploited Christians, are politically housed within the National Democratic Front, a coalition of movements that includes a strong communist thread currently fighting the far-right authoritarian leader Rodrigo Duterte .

Closer to home and outside of armed struggles, Christians are also present today in communist movements in the United States and Canada. Whatever hostilities may have existed in the past, some of these movements are quite open to Christian participation now. Many of my friends in the Party for Socialism and Liberation , for example, a Marxist-Leninist party, are churchgoing Christians or folks without a grudge against their Christian upbringing, as are lots of people in the radical wing of the Democratic Socialists of America .

The Communist Party USA has published essays affirming the connections between Christianity and communism and encouraging Marxists not to write off Christians as hopelessly lost to the right (the C.P.U.S.A. paper, People’s World , even reported on Sister Simone Campbell and Network’s Nuns on the Bus campaign to agitate for immigration reform). In Canada, Dave McKee, former leader of the Communist Party of Canada in Ontario, was once an Anglican theology student at a Catholic seminary, radicalized in part by his contact with base communities in Nicaragua. For my part, I have talked more about Karl Rahner, S.J., St. Óscar Romero and liberation theology at May Day celebrations and communist meetings than at my own Catholic parish.

In other words, though some communists would undoubtedly prefer a world without Christianity, communism is not simply a program for destroying the church. Many who committed their very lives to the church felt compelled to work alongside communists as part of their Christian calling. The history of communism, whatever else it might be, will always contain a history of Christianity, and vice versa, whether members of either faction like it or not.

Communism in its socio-political expression has at times caused great human and ecological suffering. Any good communist is quick to admit as much, not least because communism is an unfinished project that depends on the recognition of its real and tragic mistakes.

But communists are not the only ones who have to answer for creating human suffering. Far from being a friendly game of world competition, capitalism, Marx argued, emerged through the privatization of what was once public, like shared land, a process enforced first by physical violence and then continued by law. As time went on, human beings themselves would become the private property of other human beings.

[Questions or comments about this essay? Join the author for a live Q&A on America’s Facebook page on Thursday, July 25 at 2 p.m. EST]

Colonial capitalism, together with the assumptions of white supremacy, ushered in centuries of unbridled terrorism on populations around the world, creating a system in which people could be bought and sold as commodities. Even after the official abolition of slavery in the largest world economies—which required a costly civil war in the United States—the effects of that system live on, and capitalist nations and transnational companies continue to exploit poor and working people at home and abroad. For many people around the globe today, being on the wrong side of capitalism can still mean the difference between life and death.

What Motivates a Communist?

Communism has provided one of the few sustainable oppositions to capitalism, a global political order responsible for the ongoing suffering of millions. It is that suffering, reproduced by economic patterns that Marx and others tried to explain, and not the secret plot of atheism (as Day once argued), that motivates communists.

According to a report by Oxfam released in 2018, global inequality is staggering and still on the rise. Oxfam, which is not run by communists, observed that “82 percent of the wealth created [in 2017] went to the richest one percent of the global population, while the 3.7 billion people who make up the poorest half of humanity got nothing.”

While entrepreneurs like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos are investing in space travel, their workers are grounded in daily economic struggle here on earth. In Mr. Musk’s Tesla factories, workers suffer serious injuries more than twice the industrial average , and they report being so exhausted that they collapse on the factory floor .

An undercover journalist reports workers urinate into bottles in a U.K. Amazon warehouse for fear of being disciplined for “idle time,” and the company has a long list of previous offenses. In Pennsylvania , Amazon workers needed medical attention both for exposure to the cold in the winter and for heat exhaustion in the summer. These hardly seem like prices worth paying so a few billionaires can vacation in the black expanse of space. As one Detroit Tesla worker put it: “Everything feels like the future but us.”

For communists, global inequality and the abuse of workers at highly profitable corporations are not the result only of unkind employers or unfair labor regulations. They are symptoms of a specific way of organizing wealth, one that did not exist at the creation of the world and one that represents part of a “culture of death,” to borrow a familiar phrase. We already live in a world where wealth is redistributed, but it goes up, not down or across.

Though polls show U.S. citizens have become increasingly skeptical of capitalism— one Gallup survey even reports that Democrats currently view socialism more positively than capitalism—that attitude is not widely popular among electoral representatives. A revival of socialist hysteria typified the response to Bernie Sanders’s inspiring 2016 primary bid and the electoral success of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Rashida Tlaib, members of the Democratic Socialists of America , a party co-founded by a former Catholic Worker, Michael Harrington. Republican and Democratic politicians have made it abundantly clear that whatever their differences, they both agree that in U.S. political culture support for capitalism is non-negotiable, as Nancy Pelosi told a socialist questioner during a CNN town hall.

Communists are not content with the back-and-forth of capitalist parties, who point fingers at one another while maintaining, jointly, a system that exploits multitudes of people, including their own constituents. Communists think we can build better ways of being together in society.