Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 20 December 2019

Secrets to writing a winning grant

- Emily Sohn 0

Emily Sohn is a freelance journalist in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

When Kylie Ball begins a grant-writing workshop, she often alludes to the funding successes and failures that she has experienced in her career. “I say, ‘I’ve attracted more than $25 million in grant funding and have had more than 60 competitive grants funded. But I’ve also had probably twice as many rejected.’ A lot of early-career researchers often find those rejections really tough to take. But I actually think you learn so much from the rejected grants.”

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 577 , 133-135 (2020)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03914-5

Related Articles

- Communication

Londoners see what a scientist looks like up close in 50 photographs

Career News 18 APR 24

Deadly diseases and inflatable suits: how I found my niche in virology research

Spotlight 17 APR 24

How young people benefit from Swiss apprenticeships

Canadian science gets biggest boost to PhD and postdoc pay in 20 years

News 17 APR 24

How India can become a science powerhouse

Editorial 16 APR 24

NASA admits plan to bring Mars rocks to Earth won’t work — and seeks fresh ideas

News 15 APR 24

‘Shrugging off failure is hard’: the $400-million grant setback that shaped the Smithsonian lead scientist’s career

Career Column 15 APR 24

How I harnessed media engagement to supercharge my research career

Career Column 09 APR 24

Tweeting your research paper boosts engagement but not citations

News 27 MAR 24

Research Associate - Brain Cancer

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Senior Manager, Animal Care

Research associate - genomics, postdoctoral associate- artificial intelligence, postdoctoral research fellow.

Looking for postdoctoral fellowship candidates to advance genomic research in the study of lung diseases at Brigham and Women's Hospital and HMS.

Boston, Massachusetts

Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Grant Proposals (or Give me the money!)

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you write and revise grant proposals for research funding in all academic disciplines (sciences, social sciences, humanities, and the arts). It’s targeted primarily to graduate students and faculty, although it will also be helpful to undergraduate students who are seeking funding for research (e.g. for a senior thesis).

The grant writing process

A grant proposal or application is a document or set of documents that is submitted to an organization with the explicit intent of securing funding for a research project. Grant writing varies widely across the disciplines, and research intended for epistemological purposes (philosophy or the arts) rests on very different assumptions than research intended for practical applications (medicine or social policy research). Nonetheless, this handout attempts to provide a general introduction to grant writing across the disciplines.

Before you begin writing your proposal, you need to know what kind of research you will be doing and why. You may have a topic or experiment in mind, but taking the time to define what your ultimate purpose is can be essential to convincing others to fund that project. Although some scholars in the humanities and arts may not have thought about their projects in terms of research design, hypotheses, research questions, or results, reviewers and funding agencies expect you to frame your project in these terms. You may also find that thinking about your project in these terms reveals new aspects of it to you.

Writing successful grant applications is a long process that begins with an idea. Although many people think of grant writing as a linear process (from idea to proposal to award), it is a circular process. Many people start by defining their research question or questions. What knowledge or information will be gained as a direct result of your project? Why is undertaking your research important in a broader sense? You will need to explicitly communicate this purpose to the committee reviewing your application. This is easier when you know what you plan to achieve before you begin the writing process.

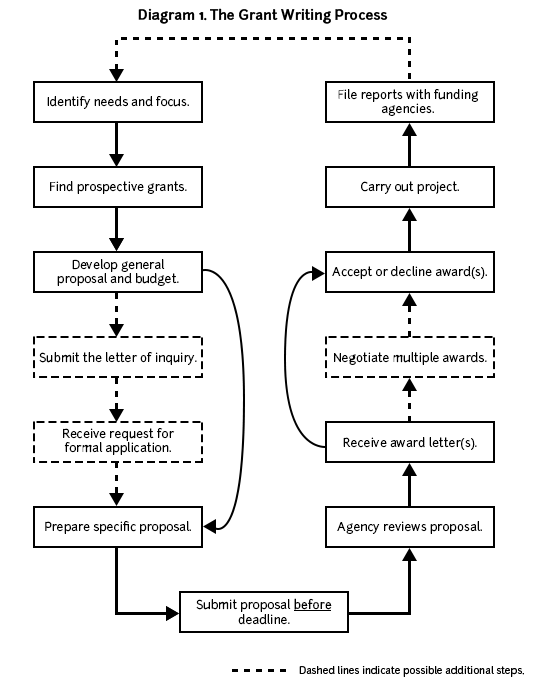

Diagram 1 below provides an overview of the grant writing process and may help you plan your proposal development.

Applicants must write grant proposals, submit them, receive notice of acceptance or rejection, and then revise their proposals. Unsuccessful grant applicants must revise and resubmit their proposals during the next funding cycle. Successful grant applications and the resulting research lead to ideas for further research and new grant proposals.

Cultivating an ongoing, positive relationship with funding agencies may lead to additional grants down the road. Thus, make sure you file progress reports and final reports in a timely and professional manner. Although some successful grant applicants may fear that funding agencies will reject future proposals because they’ve already received “enough” funding, the truth is that money follows money. Individuals or projects awarded grants in the past are more competitive and thus more likely to receive funding in the future.

Some general tips

- Begin early.

- Apply early and often.

- Don’t forget to include a cover letter with your application.

- Answer all questions. (Pre-empt all unstated questions.)

- If rejected, revise your proposal and apply again.

- Give them what they want. Follow the application guidelines exactly.

- Be explicit and specific.

- Be realistic in designing the project.

- Make explicit the connections between your research questions and objectives, your objectives and methods, your methods and results, and your results and dissemination plan.

- Follow the application guidelines exactly. (We have repeated this tip because it is very, very important.)

Before you start writing

Identify your needs and focus.

First, identify your needs. Answering the following questions may help you:

- Are you undertaking preliminary or pilot research in order to develop a full-blown research agenda?

- Are you seeking funding for dissertation research? Pre-dissertation research? Postdoctoral research? Archival research? Experimental research? Fieldwork?

- Are you seeking a stipend so that you can write a dissertation or book? Polish a manuscript?

- Do you want a fellowship in residence at an institution that will offer some programmatic support or other resources to enhance your project?

- Do you want funding for a large research project that will last for several years and involve multiple staff members?

Next, think about the focus of your research/project. Answering the following questions may help you narrow it down:

- What is the topic? Why is this topic important?

- What are the research questions that you’re trying to answer? What relevance do your research questions have?

- What are your hypotheses?

- What are your research methods?

- Why is your research/project important? What is its significance?

- Do you plan on using quantitative methods? Qualitative methods? Both?

- Will you be undertaking experimental research? Clinical research?

Once you have identified your needs and focus, you can begin looking for prospective grants and funding agencies.

Finding prospective grants and funding agencies

Whether your proposal receives funding will rely in large part on whether your purpose and goals closely match the priorities of granting agencies. Locating possible grantors is a time consuming task, but in the long run it will yield the greatest benefits. Even if you have the most appealing research proposal in the world, if you don’t send it to the right institutions, then you’re unlikely to receive funding.

There are many sources of information about granting agencies and grant programs. Most universities and many schools within universities have Offices of Research, whose primary purpose is to support faculty and students in grant-seeking endeavors. These offices usually have libraries or resource centers to help people find prospective grants.

At UNC, the Research at Carolina office coordinates research support.

The Funding Information Portal offers a collection of databases and proposal development guidance.

The UNC School of Medicine and School of Public Health each have their own Office of Research.

Writing your proposal

The majority of grant programs recruit academic reviewers with knowledge of the disciplines and/or program areas of the grant. Thus, when writing your grant proposals, assume that you are addressing a colleague who is knowledgeable in the general area, but who does not necessarily know the details about your research questions.

Remember that most readers are lazy and will not respond well to a poorly organized, poorly written, or confusing proposal. Be sure to give readers what they want. Follow all the guidelines for the particular grant you are applying for. This may require you to reframe your project in a different light or language. Reframing your project to fit a specific grant’s requirements is a legitimate and necessary part of the process unless it will fundamentally change your project’s goals or outcomes.

Final decisions about which proposals are funded often come down to whether the proposal convinces the reviewer that the research project is well planned and feasible and whether the investigators are well qualified to execute it. Throughout the proposal, be as explicit as possible. Predict the questions that the reviewer may have and answer them. Przeworski and Salomon (1995) note that reviewers read with three questions in mind:

- What are we going to learn as a result of the proposed project that we do not know now? (goals, aims, and outcomes)

- Why is it worth knowing? (significance)

- How will we know that the conclusions are valid? (criteria for success) (2)

Be sure to answer these questions in your proposal. Keep in mind that reviewers may not read every word of your proposal. Your reviewer may only read the abstract, the sections on research design and methodology, the vitae, and the budget. Make these sections as clear and straightforward as possible.

The way you write your grant will tell the reviewers a lot about you (Reif-Lehrer 82). From reading your proposal, the reviewers will form an idea of who you are as a scholar, a researcher, and a person. They will decide whether you are creative, logical, analytical, up-to-date in the relevant literature of the field, and, most importantly, capable of executing the proposed project. Allow your discipline and its conventions to determine the general style of your writing, but allow your own voice and personality to come through. Be sure to clarify your project’s theoretical orientation.

Develop a general proposal and budget

Because most proposal writers seek funding from several different agencies or granting programs, it is a good idea to begin by developing a general grant proposal and budget. This general proposal is sometimes called a “white paper.” Your general proposal should explain your project to a general academic audience. Before you submit proposals to different grant programs, you will tailor a specific proposal to their guidelines and priorities.

Organizing your proposal

Although each funding agency will have its own (usually very specific) requirements, there are several elements of a proposal that are fairly standard, and they often come in the following order:

- Introduction (statement of the problem, purpose of research or goals, and significance of research)

Literature review

- Project narrative (methods, procedures, objectives, outcomes or deliverables, evaluation, and dissemination)

- Budget and budget justification

Format the proposal so that it is easy to read. Use headings to break the proposal up into sections. If it is long, include a table of contents with page numbers.

The title page usually includes a brief yet explicit title for the research project, the names of the principal investigator(s), the institutional affiliation of the applicants (the department and university), name and address of the granting agency, project dates, amount of funding requested, and signatures of university personnel authorizing the proposal (when necessary). Most funding agencies have specific requirements for the title page; make sure to follow them.

The abstract provides readers with their first impression of your project. To remind themselves of your proposal, readers may glance at your abstract when making their final recommendations, so it may also serve as their last impression of your project. The abstract should explain the key elements of your research project in the future tense. Most abstracts state: (1) the general purpose, (2) specific goals, (3) research design, (4) methods, and (5) significance (contribution and rationale). Be as explicit as possible in your abstract. Use statements such as, “The objective of this study is to …”

Introduction

The introduction should cover the key elements of your proposal, including a statement of the problem, the purpose of research, research goals or objectives, and significance of the research. The statement of problem should provide a background and rationale for the project and establish the need and relevance of the research. How is your project different from previous research on the same topic? Will you be using new methodologies or covering new theoretical territory? The research goals or objectives should identify the anticipated outcomes of the research and should match up to the needs identified in the statement of problem. List only the principle goal(s) or objective(s) of your research and save sub-objectives for the project narrative.

Many proposals require a literature review. Reviewers want to know whether you’ve done the necessary preliminary research to undertake your project. Literature reviews should be selective and critical, not exhaustive. Reviewers want to see your evaluation of pertinent works. For more information, see our handout on literature reviews .

Project narrative

The project narrative provides the meat of your proposal and may require several subsections. The project narrative should supply all the details of the project, including a detailed statement of problem, research objectives or goals, hypotheses, methods, procedures, outcomes or deliverables, and evaluation and dissemination of the research.

For the project narrative, pre-empt and/or answer all of the reviewers’ questions. Don’t leave them wondering about anything. For example, if you propose to conduct unstructured interviews with open-ended questions, be sure you’ve explained why this methodology is best suited to the specific research questions in your proposal. Or, if you’re using item response theory rather than classical test theory to verify the validity of your survey instrument, explain the advantages of this innovative methodology. Or, if you need to travel to Valdez, Alaska to access historical archives at the Valdez Museum, make it clear what documents you hope to find and why they are relevant to your historical novel on the ’98ers in the Alaskan Gold Rush.

Clearly and explicitly state the connections between your research objectives, research questions, hypotheses, methodologies, and outcomes. As the requirements for a strong project narrative vary widely by discipline, consult a discipline-specific guide to grant writing for some additional advice.

Explain staffing requirements in detail and make sure that staffing makes sense. Be very explicit about the skill sets of the personnel already in place (you will probably include their Curriculum Vitae as part of the proposal). Explain the necessary skill sets and functions of personnel you will recruit. To minimize expenses, phase out personnel who are not relevant to later phases of a project.

The budget spells out project costs and usually consists of a spreadsheet or table with the budget detailed as line items and a budget narrative (also known as a budget justification) that explains the various expenses. Even when proposal guidelines do not specifically mention a narrative, be sure to include a one or two page explanation of the budget. To see a sample budget, turn to Example #1 at the end of this handout.

Consider including an exhaustive budget for your project, even if it exceeds the normal grant size of a particular funding organization. Simply make it clear that you are seeking additional funding from other sources. This technique will make it easier for you to combine awards down the road should you have the good fortune of receiving multiple grants.

Make sure that all budget items meet the funding agency’s requirements. For example, all U.S. government agencies have strict requirements for airline travel. Be sure the cost of the airline travel in your budget meets their requirements. If a line item falls outside an agency’s requirements (e.g. some organizations will not cover equipment purchases or other capital expenses), explain in the budget justification that other grant sources will pay for the item.

Many universities require that indirect costs (overhead) be added to grants that they administer. Check with the appropriate offices to find out what the standard (or required) rates are for overhead. Pass a draft budget by the university officer in charge of grant administration for assistance with indirect costs and costs not directly associated with research (e.g. facilities use charges).

Furthermore, make sure you factor in the estimated taxes applicable for your case. Depending on the categories of expenses and your particular circumstances (whether you are a foreign national, for example), estimated tax rates may differ. You can consult respective departmental staff or university services, as well as professional tax assistants. For information on taxes on scholarships and fellowships, see https://cashier.unc.edu/student-tax-information/scholarships-fellowships/ .

Explain the timeframe for the research project in some detail. When will you begin and complete each step? It may be helpful to reviewers if you present a visual version of your timeline. For less complicated research, a table summarizing the timeline for the project will help reviewers understand and evaluate the planning and feasibility. See Example #2 at the end of this handout.

For multi-year research proposals with numerous procedures and a large staff, a time line diagram can help clarify the feasibility and planning of the study. See Example #3 at the end of this handout.

Revising your proposal

Strong grant proposals take a long time to develop. Start the process early and leave time to get feedback from several readers on different drafts. Seek out a variety of readers, both specialists in your research area and non-specialist colleagues. You may also want to request assistance from knowledgeable readers on specific areas of your proposal. For example, you may want to schedule a meeting with a statistician to help revise your methodology section. Don’t hesitate to seek out specialized assistance from the relevant research offices on your campus. At UNC, the Odum Institute provides a variety of services to graduate students and faculty in the social sciences.

In your revision and editing, ask your readers to give careful consideration to whether you’ve made explicit the connections between your research objectives and methodology. Here are some example questions:

- Have you presented a compelling case?

- Have you made your hypotheses explicit?

- Does your project seem feasible? Is it overly ambitious? Does it have other weaknesses?

- Have you stated the means that grantors can use to evaluate the success of your project after you’ve executed it?

If a granting agency lists particular criteria used for rating and evaluating proposals, be sure to share these with your own reviewers.

Example #1. Sample Budget

Jet travel $6,100 This estimate is based on the commercial high season rate for jet economy travel on Sabena Belgian Airlines. No U.S. carriers fly to Kigali, Rwanda. Sabena has student fare tickets available which will be significantly less expensive (approximately $2,000).

Maintenance allowance $22,788 Based on the Fulbright-Hays Maintenance Allowances published in the grant application guide.

Research assistant/translator $4,800 The research assistant/translator will be a native (and primary) speaker of Kinya-rwanda with at least a four-year university degree. They will accompany the primary investigator during life history interviews to provide assistance in comprehension. In addition, they will provide commentary, explanations, and observations to facilitate the primary investigator’s participant observation. During the first phase of the project in Kigali, the research assistant will work forty hours a week and occasional overtime as needed. During phases two and three in rural Rwanda, the assistant will stay with the investigator overnight in the field when necessary. The salary of $400 per month is based on the average pay rate for individuals with similar qualifications working for international NGO’s in Rwanda.

Transportation within country, phase one $1,200 The primary investigator and research assistant will need regular transportation within Kigali by bus and taxi. The average taxi fare in Kigali is $6-8 and bus fare is $.15. This figure is based on an average of $10 per day in transportation costs during the first project phase.

Transportation within country, phases two and three $12,000 Project personnel will also require regular transportation between rural field sites. If it is not possible to remain overnight, daily trips will be necessary. The average rental rate for a 4×4 vehicle in Rwanda is $130 per day. This estimate is based on an average of $50 per day in transportation costs for the second and third project phases. These costs could be reduced if an arrangement could be made with either a government ministry or international aid agency for transportation assistance.

Email $720 The rate for email service from RwandaTel (the only service provider in Rwanda) is $60 per month. Email access is vital for receiving news reports on Rwanda and the region as well as for staying in contact with dissertation committee members and advisors in the United States.

Audiocassette tapes $400 Audiocassette tapes will be necessary for recording life history interviews, musical performances, community events, story telling, and other pertinent data.

Photographic & slide film $100 Photographic and slide film will be necessary to document visual data such as landscape, environment, marriages, funerals, community events, etc.

Laptop computer $2,895 A laptop computer will be necessary for recording observations, thoughts, and analysis during research project. Price listed is a special offer to UNC students through the Carolina Computing Initiative.

NUD*IST 4.0 software $373.00 NUD*IST, “Nonnumerical, Unstructured Data, Indexing, Searching, and Theorizing,” is necessary for cataloging, indexing, and managing field notes both during and following the field research phase. The program will assist in cataloging themes that emerge during the life history interviews.

Administrative fee $100 Fee set by Fulbright-Hays for the sponsoring institution.

Example #2: Project Timeline in Table Format

Example #3: project timeline in chart format.

Some closing advice

Some of us may feel ashamed or embarrassed about asking for money or promoting ourselves. Often, these feelings have more to do with our own insecurities than with problems in the tone or style of our writing. If you’re having trouble because of these types of hang-ups, the most important thing to keep in mind is that it never hurts to ask. If you never ask for the money, they’ll never give you the money. Besides, the worst thing they can do is say no.

UNC resources for proposal writing

Research at Carolina http://research.unc.edu

The Odum Institute for Research in the Social Sciences https://odum.unc.edu/

UNC Medical School Office of Research https://www.med.unc.edu/oor

UNC School of Public Health Office of Research http://www.sph.unc.edu/research/

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Holloway, Brian R. 2003. Proposal Writing Across the Disciplines. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Levine, S. Joseph. “Guide for Writing a Funding Proposal.” http://www.learnerassociates.net/proposal/ .

Locke, Lawrence F., Waneen Wyrick Spirduso, and Stephen J. Silverman. 2014. Proposals That Work . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Przeworski, Adam, and Frank Salomon. 2012. “Some Candid Suggestions on the Art of Writing Proposals.” Social Science Research Council. https://s3.amazonaws.com/ssrc-cdn2/art-of-writing-proposals-dsd-e-56b50ef814f12.pdf .

Reif-Lehrer, Liane. 1989. Writing a Successful Grant Application . Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Wiggins, Beverly. 2002. “Funding and Proposal Writing for Social Science Faculty and Graduate Student Research.” Chapel Hill: Howard W. Odum Institute for Research in Social Science. 2 Feb. 2004. http://www2.irss.unc.edu/irss/shortcourses/wigginshandouts/granthandout.pdf.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Research Process

Writing a Scientific Research Project Proposal

- 5 minute read

- 98.2K views

Table of Contents

The importance of a well-written research proposal cannot be underestimated. Your research really is only as good as your proposal. A poorly written, or poorly conceived research proposal will doom even an otherwise worthy project. On the other hand, a well-written, high-quality proposal will increase your chances for success.

In this article, we’ll outline the basics of writing an effective scientific research proposal, including the differences between research proposals, grants and cover letters. We’ll also touch on common mistakes made when submitting research proposals, as well as a simple example or template that you can follow.

What is a scientific research proposal?

The main purpose of a scientific research proposal is to convince your audience that your project is worthwhile, and that you have the expertise and wherewithal to complete it. The elements of an effective research proposal mirror those of the research process itself, which we’ll outline below. Essentially, the research proposal should include enough information for the reader to determine if your proposed study is worth pursuing.

It is not an uncommon misunderstanding to think that a research proposal and a cover letter are the same things. However, they are different. The main difference between a research proposal vs cover letter content is distinct. Whereas the research proposal summarizes the proposal for future research, the cover letter connects you to the research, and how you are the right person to complete the proposed research.

There is also sometimes confusion around a research proposal vs grant application. Whereas a research proposal is a statement of intent, related to answering a research question, a grant application is a specific request for funding to complete the research proposed. Of course, there are elements of overlap between the two documents; it’s the purpose of the document that defines one or the other.

Scientific Research Proposal Format

Although there is no one way to write a scientific research proposal, there are specific guidelines. A lot depends on which journal you’re submitting your research proposal to, so you may need to follow their scientific research proposal template.

In general, however, there are fairly universal sections to every scientific research proposal. These include:

- Title: Make sure the title of your proposal is descriptive and concise. Make it catch and informative at the same time, avoiding dry phrases like, “An investigation…” Your title should pique the interest of the reader.

- Abstract: This is a brief (300-500 words) summary that includes the research question, your rationale for the study, and any applicable hypothesis. You should also include a brief description of your methodology, including procedures, samples, instruments, etc.

- Introduction: The opening paragraph of your research proposal is, perhaps, the most important. Here you want to introduce the research problem in a creative way, and demonstrate your understanding of the need for the research. You want the reader to think that your proposed research is current, important and relevant.

- Background: Include a brief history of the topic and link it to a contemporary context to show its relevance for today. Identify key researchers and institutions also looking at the problem

- Literature Review: This is the section that may take the longest amount of time to assemble. Here you want to synthesize prior research, and place your proposed research into the larger picture of what’s been studied in the past. You want to show your reader that your work is original, and adds to the current knowledge.

- Research Design and Methodology: This section should be very clearly and logically written and organized. You are letting your reader know that you know what you are going to do, and how. The reader should feel confident that you have the skills and knowledge needed to get the project done.

- Preliminary Implications: Here you’ll be outlining how you anticipate your research will extend current knowledge in your field. You might also want to discuss how your findings will impact future research needs.

- Conclusion: This section reinforces the significance and importance of your proposed research, and summarizes the entire proposal.

- References/Citations: Of course, you need to include a full and accurate list of any and all sources you used to write your research proposal.

Common Mistakes in Writing a Scientific Research Project Proposal

Remember, the best research proposal can be rejected if it’s not well written or is ill-conceived. The most common mistakes made include:

- Not providing the proper context for your research question or the problem

- Failing to reference landmark/key studies

- Losing focus of the research question or problem

- Not accurately presenting contributions by other researchers and institutions

- Incompletely developing a persuasive argument for the research that is being proposed

- Misplaced attention on minor points and/or not enough detail on major issues

- Sloppy, low-quality writing without effective logic and flow

- Incorrect or lapses in references and citations, and/or references not in proper format

- The proposal is too long – or too short

Scientific Research Proposal Example

There are countless examples that you can find for successful research proposals. In addition, you can also find examples of unsuccessful research proposals. Search for successful research proposals in your field, and even for your target journal, to get a good idea on what specifically your audience may be looking for.

While there’s no one example that will show you everything you need to know, looking at a few will give you a good idea of what you need to include in your own research proposal. Talk, also, to colleagues in your field, especially if you are a student or a new researcher. We can often learn from the mistakes of others. The more prepared and knowledgeable you are prior to writing your research proposal, the more likely you are to succeed.

Language Editing Services

One of the top reasons scientific research proposals are rejected is due to poor logic and flow. Check out our Language Editing Services to ensure a great proposal , that’s clear and concise, and properly referenced. Check our video for more information, and get started today.

- Manuscript Review

Research Fraud: Falsification and Fabrication in Research Data

Research Team Structure

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Basics of scientific and technical writing: Grant proposals

- Career Central

- Published: 23 April 2021

- Volume 46 , pages 455–457, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Morteza Monavarian 1

5055 Accesses

148 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Grant proposals

A grant proposal is a formal document you submit to a funding agency or an investing organization to persuade them to provide the requested support by showing that (1) you have a plan to advance a certain valuable cause and (2) that the team is fully capable of reaching the proposed goals. The document may contain a description of the ideas and preliminary results relative to the state of the art, goals, as well as research and budget plans. This article provides an overview of some steps toward preparation of grant proposal applications, with a particular focus on proposals for research activities in academia, industry, and research institutes.

Different types of proposals

There are different types of grant proposals depending on the objectives, activity period, and funding organization source: (1) research proposals, (2) equipment proposals, and (3) industry-related proposals. Research proposals are those that seek funding to support research activities for a certain period of time, while equipment proposals aim for a certain equipment to be purchased. For equipment proposals to be granted, you need to carefully explain how its purchase could help advance research activities in different directions. Unlike research proposals, which are focused on a specific direction within a certain field of research, equipment proposals can have different directions within different areas of research, as long as the proposed equipment can be used in those areas.

There are also industry-related funding opportunities. For example, the National Science Foundation (NSF) has programs within its Division of Industrial Innovation and Partnerships, in which small businesses and industries can involve research funding opportunities. Examples of such programs include Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer programs. These opportunities are separate from any opportunities directly involving the companies funding your research, where the companies are the source of the funding.

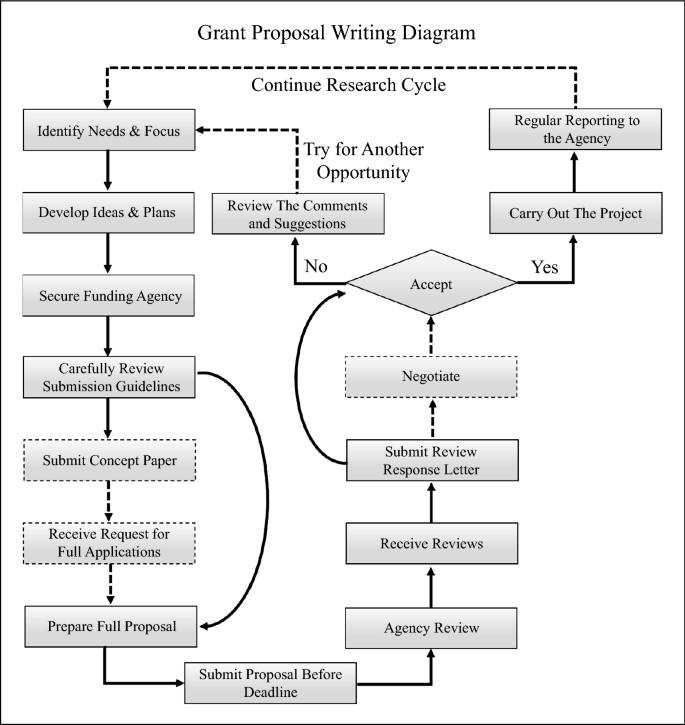

Steps to submit a proposal

Figure 1 shows an overview of a standard process flow for a grant proposal application, from identifying the needs and focus to acceptance and starting the project. As shown, the process of writing grants is not linear, but rather a loop, indicating the need for consistent modifications and development of your ideas, depending on the input you receive from the funding agencies or the results you obtained from previously funded projects.

Diagram of grant proposal preparation.

Before starting, you need to define the ultimate purpose of the research you want to pursue and to convince others that the work is indeed worth pursuing. Think about your proposed research in the context of problems to solve, potential hypotheses, and research design. To start shaping the idea you are pursuing, ask yourself: (1) What knowledge do I gain from finishing this project? (2) What is the significance of the end goal of the project? (3) How would the completion of this project be useful in a broader sense? Having convincing answers to these questions would be extremely helpful in developing a good grant proposal.

After identifying the needs and focus and initially developing the ideas and plans, the next step is to secure a funding agency to which you would like to submit the grant proposal. It is a good practice to keep track of programs and corresponding funding opportunity announcements for different funding agencies relevant to your field of research. Once you secure a funding agency and find the deadline for submission, review the submission guidelines for the program carefully. The grant proposal document should be perfectly aligned with the structure and content proposed in the guidelines provided by the agency program to avoid any premature rejection of your application. Some programs only require a few documents, while others many more. Some agencies may require a concept paper: a short version of the proposal submitted before you are eligible for a full proposal submission.

After securing the agency/program and reviewing the guidelines, the next step is to write the full proposal document, according to the guidelines proposed by the funding agency. Before submission, review your documents multiple times to ensure the sections are well written and are consistent with one another and that they perfectly convey your messages. Some institutes have experts in reviewing proposal documents for potential linguistic and/or technical edits. Submit at least a day before the deadline to ensure that all documents safely go through. Some agencies have strict deadlines, which you do not want to miss, or you may have to wait upwards of a year to submit again. The agency then usually sends your documents to a few expert reviewers for their comments. The review may be graded or have written comments that require attention and response. A response letter has to be prepared and submitted (according to the agency guidelines) by a new deadline imposed by the agency for consideration by the program manager.

After reviewing the full response and revised documents, the agency will contact you with notification of their decision. If your proposal is accepted, the agency will provide details regarding funding and a start date. During the term of the project, agencies normally require a periodic (quarterly or annually) report in either a written or oral form. Different agencies may have rules for any publications or patents that could potentially result during the project term, when the work is complete or the idea is developed as a result of the awarded grant. As shown in the figure, even if the proposal is rejected, upon careful review, revision, and further development or adjustment of the proposal, you may try for another funding opportunity. After finishing a recently funded project, you can further develop an idea and submit another proposal for funding.

Structure of proposals (NSF example)

The structure of proposals differs with funding agencies. Included is an overview of an NSF proposal as a guide.

In addition to the technical volume (narrative) document, containing all the major descriptions of the project, other necessary documents include bio sketches, budget, justifications, management plan, and project summary. Bio sketches contain resumes of all the principal investigators (PIs), including any prior experience, relevant publications, and outreach activities. Budget and justifications are two separate documents relevant to a breakdown of the required budgets for the project, including salaries for the PIs and the team, travel, publication costs, equipment costs, materials and supplies, and any other relevant expenses. The budget document could be an Excel spreadsheet, indicating the exact dollar amounts, while the justification indicates the rationale for each charge. Depending on the agency and program, some expenses are allowed to be included in the budget list (carefully read related guidelines). Other potential requirements for submission may include a description of the project summary, management plans, and the facilities in which the work will be performed.

The technical volume is likely the one you will spend the most time preparing. It consists of several sections. Included is an example of a structure (read the Proposal and Award Policies and Procedures Guide on the NSF website for details). The total technical volume should not exceed 15 pages, excluding the reference section, which will be submitted as a separate document. While there are different review criteria for an NSF proposal, the main two are intellectual merit (encompasses the potential to advance knowledge) and broader impacts (potential to benefit society). Your proposal should reflect that the work will be rich in these two criteria. NSF reviewers typically provide qualitative grades (ranging from poor to excellent) to the proposal and feedback in their review.

Introduction and overview

The first section of the technical volume may start with an introduction/motivation and overview of the proposed work. This section should be no longer than a page, but should give an overview of the background and state of the art in the research area, motivations, objectives of the proposed work (maybe in the context of intellectual merit and broader impacts), and a brief description of the work breakdown (tasks). The last couple of paragraphs of the introduction could summarize the education and outreach plans, as well as the PIs’ experience and expertise. Feel free to highlight any major statements in this section to serve as main takeaways for the reviewers. Also, making an overview figure for this section may help summarize the information.

Background and relationship to the state of the art

The second section gives more details of background and relationship to the state of the art. This section may be a few pages long and contain figures and relevant citations.

Technical methods and preliminary results

This section should describe the technical methods and preliminary results relevant to the proposed research from your prior work. It should contain illustrative figures and plots to back up the proposed work.

Research plan

After discussing the prior art and the technical methods and preliminary results (in previous sections), you should discuss the proposed research and plan. A good standard is to divide your work into two to three thrusts, with each thrust containing two to three tasks. You can also prepare a timetable (also called a Gantt chart) to indicate when the tasks will be completed with respect to the project term, which is usually between three to five years.

Integration of education and research

The last section should describe any plans for integration of education and research, including any K-12 programs or planned outreach activities.

Results from prior supports

Finally, describe results from all of your prior NSF supports. For each project, provide a paragraph describing the goal of the project, the outcomes, and any related publications. You can also write this section in the context of intellectual merit and broader impacts.

Things to remember when preparing grant proposals

Find the proper timing for any idea to explore. Sometimes the idea you think is worth pursuing is either too early or too late to explore, depending on the existing body of literature.

Begin early to avoid missing any deadlines. Give the process some time, as it could take a while.

Try to have sufficient preliminary results as seeds for the proposal.

Have a decent balance between the amount of ideas and preliminary results you put in the grant proposal. Too many ideas but too few results may make your proposal sound too ambitious, while too few ideas and too many results may make your proposed work seem complete, therefore no need for funding.

Try to attend funding agency panels. It will help you understand the review process, grading criteria, and mindsets of program managers. Learn about proposals that are funded.

Locate any related funding agency announcements to know the deadlines in advance.

Be mindful of deadlines. Last day submissions may jeopardize your funding opportunities.

Learn what is customary. One figure per page is ideal for the proposed technical volume. A wordy proposal with not enough figures will be boring and more difficult for the reviewers to follow.

Do not give up! You may need to submit several proposals (to different programs/agencies) to get one awarded.

Be cautious about self-plagiarism! Do not copy and paste texts/figures from your previously supported proposal or papers in your new submissions.

Be ambitious but practical when developing ideas.

Develop a solid research program. It is not all about hunting grants; it is also how to execute your funded projects. You may have periods (waves) of grant hunting followed by periods of delivering on the funded projects. Any successful prior research can help you gain more funding in the next wave.

Enjoy your research!

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Materials Department and Solid State Lighting & Energy Electronics Center, University of California, Santa Barbara, USA

Morteza Monavarian

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Additional information

This article is the third in a three-part series in MRS Bulletin that will focus on writing papers, patents, and proposals.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Monavarian, M. Basics of scientific and technical writing: Grant proposals. MRS Bulletin 46 , 455–457 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1557/s43577-021-00105-4

Download citation

Published : 23 April 2021

Issue Date : May 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1557/s43577-021-00105-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

DAI is proud to announce a new partnership with Beckman Coulter. If you are looking for a centrifuge, check out what we have. View Centrifuges

- Support & Sales: 800-816-8388

- Find Your Rep

Your Guide to Writing Research Funding Applications

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Grant funding is critical for all types of research. Without it, many projects wouldn’t even get off the ground, so what’s the key to securing the right funding? The not-so-simple answer: a stellar grant application.

If you’ve ever wondered how to write a successful proposal — or if you’re looking for some new resources and a few refresher tips — we have the right resource for you. In this comprehensive guide, we explore all types of grant funding opportunities, provide a step-by-step proposal breakdown and offer insider tips for ultimate grant application success.

The information in this guide was provided by Mike Hendrickson, Project Manager at BrainXell, Inc; Dr. Shannon M. Lauberth, Associate Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics at Northwestern University; Dr. Darshan Sapkota, Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences at the University of Texas at Dallas; and Dr. Ward Tucker, Director of Research and Development at BioSentinel, Inc.

Find a Grant: What Opportunities Are Available?

This isn’t a comprehensive list, but these are the most popular types of grant funding opportunities.

National Institutes of Health (NIH)

The National Institutes of Health provides more than $32 billion each year for biomedical research funding. The NIH grants and funding opportunities page publishes opportunities daily and issues a table of contents weekly. You can also subscribe to a weekly email for updates.

National Science Foundation (NSF)

The National Science Foundation funds approximately 25% of all federally supported research in higher education. The NSF is divided into a number of specific research areas , including:

- Biological Sciences

- Computer and Information Science and Engineering

- Education and Human Resources

- Engineering

- Environmental Research and Education

- Geosciences

- Integrative Activities

- International Science and Engineering

- Mathematical and Physical Sciences

- Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences

You can search for NSF funding opportunities here .

Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR)

SBIR and STTR grants are geared toward small U.S. businesses that are looking for funding opportunities in research or research and development “with the potential for commercialization.” Eligible businesses must be for-profit, located in the United States, and more than 50% owned and controlled by one or more U.S. citizens. The company must also have fewer than 500 employees.

Non-Federal Agencies & Foundations

Many grant opportunities are available through non-federal avenues. This is just a sample of some of the agencies and foundations that provide these types of funding opportunities.

- Alliance for Cancer Gene Therapy

- Alzheimer’s Association

- American Federation for Aging Research

- American Heart Association

- American Cancer Society

- American Chemical Society

- American Diabetes Association

- Foundation for Women’s Wellness

- March of Dimes

Early Stage Investigator Awards

An early stage investigato r is “a new investigator who has completed his or her terminal research degree or medical residency — whichever date is later — within the past 10 years and has not yet competed successfully for a substantial, competing NIH research grant.”

- American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grants

- Pew Scholar Program

- Sidney Kimmel Foundation

- NIH New & Early Stage Investigator Program

Step-By-Step Grant Proposal & Application Breakdown

Once you’ve found your grant opportunity, it’s time to take action. Here’s what you need to know:

1. Build a timeline.

There are a lot of moving parts in the application process, so the first step is to create a timeline. You want to allow yourself enough time to gather information and write the proposal without feeling rushed. Plus, you need to factor in time for editing and internal reviews. Write down the due date of the application and work backwards. Remember, it’s always best to err on the side of having too much time rather than not enough.

2. Create a robust outline.

This is the most important part of the application process, and the more detail, the better. Be specific in your questions, hypothesis, aims and goals. Detail your experiments and expected outcomes.

3. Gather your appropriate tools and resources.

Before you begin writing, make sure you gather everything in one place. If you need to request certain documents, do so now. Create a folder on your computer that houses everything related to your grant application — and make sure to back up your files if you aren’t using Google or another cloud-based provider. It sounds like a simple reminder, but the last thing you want is to lose all your hard work.

4. Read through the application instructions carefully and don’t be afraid to ask questions. Familiarize yourself with the request, rules and requirements.

Read through everything , noting any documents you need to include. Every document that is requested must be included in the application. And if you have any questions about the process or you’re looking for clarification on a particular item, reach out to the program officer. It’s also better to ask questions as early as possible in the process.

5. Include strong preliminary data.

Even if grant requests say it is not necessary to include any data, you are unlikely to be funded if you don’t include any preliminary data. It is a major piece of any application. The stronger the data, the better shot you have of receiving funding.

6. Write, write, write!

Now it’s time to put pen to paper, so to speak. Here are some important tips to keep in mind during this important process:

- Be realistic: If you’re applying for a Phase 1 grant, it’s important to remember that Phase 1 is supposed to be “proof of concept” — in other words, not product development. Some people try to squeeze five years worth of work into one year, but you need to be realistic. Think carefully, and be modest about your objectives. If you end up applying for a Phase 2 grant, the reviewers will look at your goals and objectives for Phase 1. If you didn’t deliver then, there’s a good chance your Phase 2 proposal will be rejected.

- Tell a story. With any type of good writing, you want to build a case — in other words, tell a story. Start with an introduction that hooks the audience. Talk about the wider problem you’re hoping to explore and why you are the right person for the job. Explain your hypothesis and how you plan to tackle it.

- Include two or three specific aims. This is the heart of the grant. Again, be reasonable. Don’t bite off more than you can chew in order to seem overly ambitious. Include two or three challenging yet exciting aims (or goals) that you believe are doable in the set amount of time. Include clear objectives and clear milestones of success.

- Be mindful of your language. Be specific, informative and engaging but also concise. Use active voice and strong verbs like “determine and distinguish.” Quantify information or data.

- Don’t get too technical or use too much jargon. Remember, you know your field inside and out, but your reviewers in some cases may not. Make your application clear and readable. Write for an educated but diverse audience.

- Include preliminary data. It’s important, so it bears repeating!

- Add pictures, illustrations or graphics. No one wants to read a 15-page proposal of extremely dense text. Break up your application with a few visuals.

7. Make sure the budget matches what is allocated.

It sounds obvious, but don’t ask for more than the set budget amount. If you work at a higher education institution, you will likely work with a research office on the budget.

8. Have multiple people review your application.

Once you’ve written your grant proposal (congratulations!), you want to seek out multiple reviewers before you click submit. These reviewers should be inside your company, organization or institution, or experts in your field; you may also benefit from review by non-experts. It’s important to give your reviewers plenty of time, too. Here are some good questions to ask:

- Is the proposal clear and concise?

- Do I need more data?

- Are any parts confusing or in need of additional explanation?

- Am I telling an interesting story?

- Could I add any other visuals?

9. Give yourself enough time to familiarize yourself with the application portal — and then submit!

If you work with a research office, they will upload the application on your behalf. If you don’t, you want to make sure you familiarize yourself with the application portal before your deadline.

Insider Tips for Grant Writing Experience & Creating a Standout Application

We spoke to the experts, and here’s what they had to say:

- Talk to the program officers early and often. There are people who don’t put the time and energy into reviewing the instructions, rules and requirements of a grant application. Make sure you understand everything, and if you don’t, talk to the program officers. Remember — you don’t have to figure out everything by yourself!

- Don’t break the rules. If the application requires certain documents, make sure to include them.

- Don’t be “non-responsive.” This is grant proposal-speak for not answering a question that is asked of you. Reviewers will take note.

- Put yourself in the shoes of a reviewer. What questions will the reviewers have, and how can you answer them ahead of time? Ideally you want to address these questions with preliminary data. If you don’t have the data, it’s important to at least address those questions in your proposal — and how you plan to tackle them.

- Don’t save everything until the last minute. There’s a very good chance you heard this mantra in high school and college — and it still rings true.

- Consider hiring someone who can handle the grant application process. If you have the budget, it may be valuable to hire a person who can handle the administrative and logistical aspects of the application process. Some companies and organizations also hire part-time or full-time grant writers to handle the actual proposal writing.

- Explore all types of funding opportunities. In addition to traditional federal agencies like NIH and NSF that routinely offer grants, you should explore any internal funding opportunities for faculty and researchers. Sign up for as many email lists, newsletters and daily grant alert notifications from federal and non-federal agencies as possible. If you work in an academic setting, ask your department chair about these opportunities.

- Simultaneous submissions are allowed. It’s just illegal to accept funding from two different institutions for the same work.

Ask to help out on a grant application. Grant writing is a skill that is honed with time and experience, and the best way to get better is to practice. Review applications that your colleagues have been working on or ask them if you can help out in any way. Practice makes perfect.

- The Grant Application Writer’s Workbook: It’s one of the best tools and a resource you’ll return to again and again.

- Ask to participate in a review committee. This will give you the opportunity to see grant applications from a different perspective, which will be beneficial in your own funding quests.

- Attend grant writing workshops. This is another important way to gain insight and experience.

- Remember the big picture. As Shannon Lauberth, associate professor at Northwestern University, explains: “Remember that the exercise of writing a grant helps you to carve out clear directions for your lab.”

Grant Application Resources

This is not an exhaustive list, but here are some helpful tools and resources you may want to explore or bookmark:

- Fundamentals of the NIH Grant Process & Need to Know Resources [VIDEO]

- The Grant Application Writer’s Workbook

- NIH Grants Process Overview

- NSF Funding Search

- NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts

- SMARTS — Email alert system about funding opportunities

Specific Questions About Lab Equipment?

D.A.I. Scientific works closely with a variety of federally funded organizations, private businesses and higher education institutions to provide products and services to analytical laboratories in the pharmaceutical, educational, biotechnology and clinical industries. If you’re writing a grant application and need a budgetary quote for equipment, contact us today. Our knowledgeable experts would be happy to help.

Jamie is the regional sales manager of DAI Scientific and leads a team of 13 equipment sales consultants. His background includes 20 years of experience working with customers in academic, clinical, industrial and bio/pharma laboratories.

Jamie works with architects, engineers and lab planners to identify the correct equipment for each user’s specific needs. He also leverages his previous role as a DAI sales representative to help his sales consultants work with customers to ensure informed decisions and customer satisfaction. He stays involved in recent research by continuously attending seminars and educating himself on the products and industries he serves.

Jamie holds a bachelor’s degree in communications from the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater.

Related Posts

North Hennepin Community College

Loyola university’s new center for translational research and education, d.a.i. launches new website.

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Grant Proposal – Example, Template and Guide

Grant Proposal – Example, Template and Guide

Table of Contents

Grant Proposal

Grant Proposal is a written document that outlines a request for funding from a grant-making organization, such as a government agency, foundation, or private donor. The purpose of a grant proposal is to present a compelling case for why an individual, organization, or project deserves financial support.

Grant Proposal Outline

While the structure and specific sections of a grant proposal can vary depending on the funder’s requirements, here is a common outline that you can use as a starting point for developing your grant proposal:

- Brief overview of the project and its significance.

- Summary of the funding request and project goals.

- Key highlights and anticipated outcomes.

- Background information on the issue or problem being addressed.

- Explanation of the project’s relevance and importance.

- Clear statement of the project’s objectives.

- Detailed description of the problem or need to be addressed.

- Supporting evidence and data to demonstrate the extent and impact of the problem.

- Identification of the target population or beneficiaries.

- Broad goals that describe the desired outcomes of the project.

- Specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) objectives that contribute to the goals.

- Description of the strategies, activities, and interventions to achieve the objectives.

- Explanation of the project’s implementation plan, timeline, and key milestones.

- Roles and responsibilities of project staff and partners.

- Plan for assessing the project’s effectiveness and measuring its impact.

- Description of the data collection methods, tools, and indicators used for evaluation.

- Explanation of how the results will be used to improve the project.

- Comprehensive breakdown of project expenses, including personnel, supplies, equipment, and other costs.

- Clear justification for each budget item.

- Information about any matching funds or in-kind contributions, if applicable.

- Explanation of how the project will be sustained beyond the grant period.

- Discussion of long-term funding strategies, partnerships, and community involvement.

- Description of how the project will continue to address the identified problem in the future.

- Overview of the organization’s mission, history , and track record.

- Description of the organization’s experience and qualifications related to the proposed project.

- Summary of key staff and their roles.

- Recap of the project’s goals, objectives, and anticipated outcomes.

- Appreciation for the funder’s consideration.

- Contact information for further inquiries.

Grant Proposal Template

Here is a template for a grant proposal that you can use as a starting point. Remember to customize and adapt it based on the specific requirements and guidelines provided by the funding organization.

Dear [Grant-making Organization Name],

Executive Summary:

I. Introduction:

II. Needs Assessment:

III. Goals and Objectives:

IV. Project Methods and Approach:

V. Evaluation and Monitoring:

VI. Budget:

VII. Sustainability:

VIII. Organizational Capacity and Expertise:

IX. Conclusion:

Thank you for considering our grant proposal. We believe that this project will make a significant impact and address an important need in our community. We look forward to the opportunity to discuss our proposal further.

Grant Proposal Example

Here is an example of a grant proposal to provide you with a better understanding of how it could be structured and written:

Executive Summary: We are pleased to submit this grant proposal on behalf of [Your Organization’s Name]. Our proposal seeks funding in the amount of [Requested Amount] to support our project titled [Project Title]. This project aims to address [Describe the problem or need being addressed] in [Target Location]. By implementing a comprehensive approach, we aim to achieve [State the project’s goals and anticipated outcomes].

I. Introduction: We express our gratitude for the opportunity to present this proposal to your esteemed organization. At [Your Organization’s Name], our mission is to [Describe your organization’s mission]. Through this project, we aim to make a significant impact on [Describe the issue or problem being addressed] by [Explain the significance and relevance of the project].

II. Needs Assessment: After conducting thorough research and needs assessments in [Target Location], we have identified a pressing need for [Describe the problem or need]. The lack of [Identify key issues or challenges] has resulted in [Explain the consequences and impact of the problem]. The [Describe the target population or beneficiaries] are particularly affected, and our project aims to address their specific needs.

III. Goals and Objectives: The primary goal of our project is to [State the broad goal]. To achieve this, we have outlined the following objectives:

- [Objective 1]

- [Objective 2]

- [Objective 3] [Include additional objectives as necessary]

IV. Project Methods and Approach: To address the identified needs and accomplish our objectives, we propose the following methods and approach:

- [Describe the activities and strategies to be implemented]

- [Explain the timeline and key milestones]

- [Outline the roles and responsibilities of project staff and partners]

V. Evaluation and Monitoring: We recognize the importance of assessing the effectiveness and impact of our project. Therefore, we have developed a comprehensive evaluation plan, which includes the following:

- [Describe the data collection methods and tools]

- [Identify the indicators and metrics to measure progress]

- [Explain how the results will be analyzed and utilized]

VI. Budget: We have prepared a detailed budget for the project, totaling [Total Project Budget]. The budget includes the following key components:

- Personnel: [Salary and benefits for project staff]

- Supplies and Materials: [List necessary supplies and materials]

- Equipment: [Include any required equipment]

- Training and Capacity Building: [Specify any training or workshops]

- Other Expenses: [Additional costs, such as travel, marketing, etc.]

VII. Sustainability: Ensuring the sustainability of our project beyond the grant period is of utmost importance to us. We have devised the following strategies to ensure its long-term impact:

- [Describe plans for securing future funding]

- [Explain partnerships and collaborations with other organizations]

- [Outline community engagement and support]

VIII. Organizational Capacity and Expertise: [Your Organization’s Name] has a proven track record in successfully implementing projects of a similar nature. Our experienced team possesses the necessary skills and expertise to carry out this project effectively. Key personnel involved in the project include [List key staff and their qualifications].

IX. Conclusion: Thank you for considering our grant proposal. We firmly believe that [Project Title] will address a critical need in [Target Location] and contribute to the well-being of the [Target Population]. We are available to provide any additional information or clarification as required. We look forward to the

opportunity to discuss our proposal further and demonstrate the potential impact of this project.

Please find attached the required supporting documents, including our detailed budget, organizational information, and any additional materials that may be helpful in evaluating our proposal.

Thank you once again for considering our grant proposal. We appreciate your dedication to supporting projects that create positive change in our community. We eagerly await your response and the possibility of partnering with your esteemed organization to make a meaningful difference.

- Detailed Budget

- Organizational Information

- Additional Supporting Documents]

Grant Proposal Writing Guide

Writing a grant proposal can be a complex process, but with careful planning and attention to detail, you can create a compelling proposal. Here’s a step-by-step guide to help you through the grant proposal writing process:

- Carefully review the grant guidelines and requirements provided by the funding organization.

- Take note of the eligibility criteria, funding priorities, submission deadlines, and any specific instructions for the proposal.

- Familiarize yourself with the funding organization’s mission, goals, and previous projects they have supported.

- Gather relevant data, statistics, and evidence to support the need for your proposed project.

- Clearly define the problem or need your project aims to address.

- Identify the specific goals and objectives of your project.

- Consider how your project aligns with the mission and priorities of the funding organization.

- Organize your proposal by creating an outline that includes all the required sections.

- Arrange the sections logically and ensure a clear flow of ideas.

- Start with a concise and engaging executive summary to capture the reader’s attention.

- Provide a brief overview of your organization and the project.

- Present a clear and compelling case for the problem or need your project addresses.

- Use relevant data, research findings, and real-life examples to demonstrate the significance of the issue.

- Clearly articulate the overarching goals of your project.

- Define specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) objectives that align with the goals.

- Explain the strategies and activities you will implement to achieve the project objectives.

- Describe the timeline, milestones, and resources required for each activity.

- Highlight the uniqueness and innovation of your approach, if applicable.

- Outline your plan for evaluating the project’s effectiveness and measuring its impact.

- Discuss how you will collect and analyze data to assess the outcomes.

- Explain how the project will be sustained beyond the grant period, including future funding strategies and partnerships.

- Prepare a comprehensive budget that includes all the anticipated expenses and revenue sources.

- Clearly justify each budget item and ensure it aligns with the project activities and goals.

- Include a budget narrative that explains any cost assumptions or calculations.

- Review your proposal multiple times for clarity, coherence, and grammatical accuracy.

- Ensure that the proposal follows the formatting and length requirements specified by the funder.

- Consider seeking feedback from colleagues or experts in the field to improve your proposal.

- Gather all the necessary supporting documents, such as your organization’s background information, financial statements, resumes of key staff, and letters of support or partnership.

- Follow the submission instructions provided by the funding organization.

- Submit the proposal before the specified deadline, keeping in mind any additional submission requirements, such as online forms or hard copies.

- If possible, send a thank-you note or email to the funding organization for considering your proposal.

- Keep track of the notification date for the funding decision.

- In case of rejection, politely ask for feedback to improve future proposals.

Importance of Grant Proposal

Grant proposals play a crucial role in securing funding for organizations and projects. Here are some key reasons why grant proposals are important:

- Access to Funding: Grant proposals provide organizations with an opportunity to access financial resources that can support the implementation of projects and initiatives. Grants can provide the necessary funds for research, program development, capacity building, infrastructure improvement, and more.

- Project Development: Writing a grant proposal requires organizations to carefully plan and develop their projects. This process involves setting clear goals and objectives, identifying target populations, designing activities and strategies, and establishing timelines and budgets. Through this comprehensive planning process, organizations can enhance the effectiveness and impact of their projects.

- Validation and Credibility: Successfully securing a grant can enhance an organization’s credibility and reputation. It demonstrates to funders, partners, and stakeholders that the organization has a well-thought-out plan, sound management practices, and the capacity to execute projects effectively. Grant funding can provide validation for an organization’s work and attract further support.

- Increased Impact and Sustainability: Grant funding enables organizations to expand their reach and increase their impact. With financial resources, organizations can implement projects on a larger scale, reach more beneficiaries, and make a more significant difference in their communities. Additionally, grants often require organizations to consider long-term sustainability, encouraging them to develop strategies for continued project success beyond the grant period.

- Collaboration and Partnerships: Grant proposals often require organizations to form partnerships and collaborations with other entities, such as government agencies, nonprofit organizations, or community groups. These collaborations can lead to shared resources, expertise, and knowledge, fostering synergy and innovation in project implementation.

- Learning and Growth: The grant proposal writing process can be a valuable learning experience for organizations. It encourages them to conduct research, analyze data, and critically evaluate their programs and initiatives. Through this process, organizations can identify areas for improvement, refine their strategies, and strengthen their overall operations.

- Networking Opportunities: While preparing and submitting grant proposals, organizations have the opportunity to connect with funders, program officers, and other stakeholders. These connections can provide valuable networking opportunities, leading to future funding prospects, partnerships, and collaborations.

Purpose of Grant Proposal

The purpose of a grant proposal is to seek financial support from grant-making organizations or foundations for a specific project or initiative. Grant proposals serve several key purposes:

- Funding Acquisition: The primary purpose of a grant proposal is to secure funding for a project or program. Organizations rely on grants to obtain the financial resources necessary to implement and sustain their activities. Grant proposals outline the project’s goals, objectives, activities, and budget, making a compelling case for why the funding organization should invest in the proposed initiative.

- Project Planning and Development: Grant proposals require organizations to thoroughly plan and develop their projects before seeking funding. This includes clearly defining the problem or need the project aims to address, establishing measurable goals and objectives, and outlining the strategies and activities that will be implemented. Writing a grant proposal forces organizations to think critically about the project’s feasibility, anticipated outcomes, and impact.

- Communication and Persuasion: Grant proposals are persuasive documents designed to convince funding organizations that the proposed project is worthy of their investment. They must effectively communicate the organization’s mission, vision, and track record, as well as the specific problem being addressed and the potential benefits and impact of the project. Grant proposals use evidence, data, and compelling narratives to make a strong case for funding support.