ESL Speaking

Games + Activities to Try Out Today!

in Activities for Adults · Activities for Kids · ESL Speaking Resources

Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching: CLT, TPR

Teaching a foreign language can be a challenging but rewarding job that opens up entirely new paths of communication to students. It’s beneficial for teachers to have knowledge of the many different language learning techniques including ESL teaching methods so they can be flexible in their instruction methods, adapting them when needed.

Keep on reading for all the details you need to know about the most popular foreign language teaching methods. Some of the ESL pedagogy ideas covered are the communicative approach, total physical response, the direct method, task-based language learning, suggestopedia, grammar-translation, the audio-lingual approach and more.

Language teaching methods

Most Popular Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching

Here’s a helpful rundown of the most common language teaching methods and ESL teaching methods. You may also want to take a look at this: Foreign language teaching philosophies .

#1: The Direct Method

In the direct method ESL, all teaching occurs in the target language, encouraging the learner to think in that language. The learner does not practice translation or use their native language in the classroom. Practitioners of this method believe that learners should experience a second language without any interference from their native tongue.

Instructors do not stress rigid grammar rules but teach it indirectly through induction. This means that learners figure out grammar rules on their own by practicing the language. The goal for students is to develop connections between experience and language. They do this by concentrating on good pronunciation and the development of oral skills.

This method improves understanding, fluency , reading, and listening skills in our students. Standard techniques are question and answer, conversation, reading aloud, writing, and student self-correction for this language learning method. Learn more about this method of foreign language teaching in this video:

#2: Grammar-Translation

With this method, the student learns primarily by translating to and from the target language. Instructors encourage the learner to memorize grammar rules and vocabulary lists. There is little or no focus on speaking and listening. Teachers conduct classes in the student’s native language with this ESL teaching method.

This method’s two primary goals are to progress the learner’s reading ability to understand literature in the second language and promote the learner’s overall intellectual development. Grammar drills are a common approach. Another popular activity is translation exercises that emphasize the form of the writing instead of the content.

Although the grammar-translation approach was one of the most popular language teaching methods in the past, it has significant drawbacks that have caused it to fall out of favour in modern schools . Principally, students often have trouble conversing in the second language because they receive no instruction in oral skills.

#3: Audio-Lingual

The audio-lingual approach encourages students to develop habits that support language learning. Students learn primarily through pattern drills, particularly dialogues, which the teacher uses to help students practice and memorize the language. These dialogues follow standard configurations of communication.

There are four types of dialogues utilized in this method:

- Repetition, in which the student repeats the teacher’s statement exactly

- Inflection, where one of the words appears in a different form from the previous sentence (for example, a word may change from the singular to the plural)

- Replacement, which involves one word being replaced with another while the sentence construction remains the same

- Restatement, where the learner rephrases the teacher’s statement

This technique’s name comes from the order it uses to teach language skills. It starts with listening and speaking, followed by reading and writing, meaning that it emphasizes hearing and speaking the language before experiencing its written form. Because of this, teachers use only the target language in the classroom with this TESOL method.

Many of the current online language learning apps and programs closely follow the audio-lingual language teaching approach. It is a nice option for language learning remotely and/or alone, even though it’s an older ESL teaching method.

#4: Structural Approach

Proponents of the structural approach understand language as a set of grammatical rules that should be learned one at a time in a specific order. It focuses on mastering these structures, building one skill on top of another, instead of memorizing vocabulary. This is similar to how young children learn a new language naturally.

An example of the structural approach is teaching the present tense of a verb, like “to be,” before progressing to more advanced verb tenses, like the present continuous tense that uses “to be” as an auxiliary.

The structural approach teaches all four central language skills: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. It’s a technique that teachers can implement with many other language teaching methods.

Most ESL textbooks take this approach into account. The easier-to-grasp grammatical concepts are taught before the more difficult ones. This is one of the modern language teaching methods.

Most popular methods and approaches and language teaching

#5: Total Physical Response (TPR)

The total physical response method highlights aural comprehension by allowing the learner to respond to basic commands, like “open the door” or “sit down.” It combines language and physical movements for a comprehensive learning experience.

In an ordinary TPR class, the teacher would give verbal commands in the target language with a physical movement. The student would respond by following the command with a physical action of their own. It helps students actively connect meaning to the language and passively recognize the language’s structure.

Many instructors use TPR alongside other methods of language learning. While TPR can help learners of all ages, it is used most often with young students and beginners. It’s a nice option for an English teaching method to use alongside some of the other ones on this list.

An example of a game that could fall under TPR is Simon Says. Or, do the following as a simple review activity. After teaching classroom vocabulary, or prepositions, instruct students to do the following:

- Pick up your pencil.

- Stand behind someone.

- Put your water bottle under your chair.

Are you on your feet all day teaching young learners? Consider picking up some of these teacher shoes .

#6: Communicative Language Teaching (CLT)

These days, CLT is by far one of the most popular approaches and methods in language teaching. Keep reading to find out more about it.

This method stresses interaction and communication to teach a second language effectively. Students participate in everyday situations they are likely to encounter in the target language. For example, learners may practice introductory conversations, offering suggestions, making invitations, complaining, or expressing time or location.

Instructors also incorporate learning topics outside of conventional grammar so that students develop the ability to respond in diverse situations.

- Amazon Kindle Edition

- Bolen, Jackie (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

- 301 Pages - 12/21/2022 (Publication Date)

CLT teachers focus on being facilitators rather than straightforward instructors. Doing so helps students achieve CLT’s primary goal, learning to communicate in the target language instead of emphasizing the mastery of grammar.

Role-play , interviews, group work, and opinion sharing are popular activities practiced in communicative language teaching, along with games like scavenger hunts and information gap exercises that promote student interaction.

Most modern-day ESL teaching textbooks like Four Corners, Smart Choice, or Touchstone are heavy on communicative activities.

#7: Natural Approach

This approach aims to mimic natural language learning with a focus on communication and instruction through exposure. It de-emphasizes formal grammar training. Instead, instructors concentrate on creating a stress-free environment and avoiding forced language production from students.

Teachers also do not explicitly correct student mistakes. The goal is to reduce student anxiety and encourage them to engage with the second language spontaneously.

Classroom procedures commonly used in the natural approach are problem-solving activities, learning games , affective-humanistic tasks that involve the students’ own ideas, and content practices that synthesize various subject matter, like culture.

#8: Task-Based Language Teaching (TBL)

With this method, students complete real-world tasks using their target language. This technique encourages fluency by boosting the learner’s confidence with each task accomplished and reducing direct mistake correction.

Tasks fall under three categories:

- Information gap, or activities that involve the transfer of information from one person, place, or form to another.

- Reasoning gap tasks that ask a student to discover new knowledge from a given set of information using inference, reasoning, perception, and deduction.

- Opinion gap activities, in which students react to a particular situation by expressing their feelings or opinions.

Popular classroom tasks practiced in task-based learning include presentations on an assigned topic and conducting interviews with peers or adults in the target language. Or, having students work together to make a poster and then do a short presentation about a current event. These are just a couple of examples and there are literally thousands of things you can do in the classroom. In terms of ESL pedagogy, this is one of the most popular modern language teaching methods.

It’s considered to be a modern method of teaching English. I personally try to do at least 1-2 task-based projects in all my classes each semester. It’s a nice change of pace from my usually very communicative-focused activities.

One huge advantage of TBL is that students have some degree of freedom to learn the language they want to learn. Also, they can learn some self-reflection and teamwork skills as well.

#9: Suggestopedia Language Learning Method

This approach and method in language teaching was developed in the 1970s by psychotherapist Georgi Lozanov. It is sometimes also known as the positive suggestion method but it later became sometimes known as desuggestopedia.

Apart from using physical surroundings and a good classroom atmosphere to make students feel comfortable, here are some of the main tenants of this second language teaching method:

- Deciphering, where the teacher introduces new grammar and vocabulary.

- Concert sessions, where the teacher reads a text and the students follow along with music in the background. This can be both active and passive.

- Elaboration where students finish what they’ve learned with dramas, songs, or games.

- Introduction in which the teacher introduces new things in a playful manner.

- Production, where students speak and interact without correction or interruption.

TESOL methods and approaches

#10: The Silent Way

The silent way is an interesting ESL teaching method that isn’t that common but it does have some solid footing. After all, the goal in most language classes is to make them as student-centred as possible.

In the Silent Way, the teacher talks as little as possible, with the idea that students learn best when discovering things on their own. Learners are encouraged to be independent and to discover and figure out language on their own.

Instead of talking, the teacher uses gestures and facial expressions to communicate, as well as props, including the famous Cuisenaire Rods. These are rods of different colours and lengths.

Although it’s not practical to teach an entire course using the silent way, it does certainly have some value as a language teaching approach to remind teachers to talk less and get students talking more!

#11: Functional-Notional Approach

This English teaching method first of all recognizes that language is purposeful communication. The reason people talk is that they want to communicate something to someone else.

Parts of speech like nouns and verbs exist to express language functions and notions. People speak to inform, agree, question, persuade, evaluate, and perform various other functions. Language is also used to talk about concepts or notions like time, events, places, etc.

The role of the teacher in this second language teaching method is to evaluate how students will use the language. This will serve as a guide for what should be taught in class. Teaching specific grammar patterns or vocabulary sets does play a role but the purpose for which students need to know these things should always be kept in mind with the functional-notional Approach to English teaching.

#12: The Bilingual Method

The bilingual method uses two languages in the classroom, the mother tongue and the target language. The mother tongue is briefly used for grammar and vocabulary explanations. Then, the rest of the class is conducted in English. Check out this video for some of the pros and cons of this method:

#13: The Test Teach Test Approach (TTT)

This style of language teaching is ideal for directly targeting students’ needs. It’s best for intermediate and advanced learners. Definitely don’t use it for total beginners!

There are three stages:

- A test or task of some kind that requires students to use the target language.

- Explicit teaching or focus on accuracy with controlled practice exercises.

- Another test or task is to see if students have improved in their use of the target language.

Want to give it a try? Find out what you need to know here:

Test Teach Test TTT .

#14: Community Language Learning

In Community Language Learning, the class is considered to be one unit. They learn together. In this style of class, the teacher is not a lecturer but is more of a counsellor or guide.

In general, there is no set lesson for the day. Instead, students decide what they want to talk about. They sit in the a circle, and decide on what they want to talk about. They may ask the teacher for a translation or for advice on pronunciation or how to say something.

The conversations are recorded, and then transcribed. Students and teacher can analyze the grammar and vocabulary, as well as subject related content.

While community language learning may not comprehensively cover the English language, students will be learning what they want to learn. It’s also student-centred to the max. It’s perhaps a nice change of pace from the usual teacher-led classes, but it’s not often seen these days as the only method of teaching a class.M

#15: The Situational Approach

This approach loosely falls under the behaviourism view of language as habit formation. The situational approach to teaching English was popular in England, starting in the 1930s. Find out more about it:

Language Teaching Approaches FAQs

There are a number of common questions that people have about second or foreign language teaching and learning. Here are the answers to some of the most popular ones.

What is language teaching approaches?

A language teaching approach is a way of thinking about teaching and learning. An approach produces methods, which is the way of teaching something, in this case, a second or foreign language using techniques or activities.

What are method and approach?

Method and approach are similar but there are some key differences. An approach is the way of dealing with something while a method involves the process or steps taken to handle the issue or task.

What is presentation practice production?

How many approaches are there in language learning?

Throughout history, there have been just over 30 popular approaches to language learning. However, there are around 10 that are most widely known including task-based learning, the communicative approach, grammar-translation and the audio-lingual approach. These days, the communicative approach is all the rage.

What is the best method of English language teaching?

It’s difficult to choose the best single approach or method for English language teaching as the one used depends on the age and level of the students as well as the material being taught. Most teachers find that a mix of the communicative approach, audio-lingual approach and task-based teaching works well in most cases.

What is micro teaching?

What are the most effective methods of learning a language?

The most effective methods for learning a language really depends on the person, but in general, here are some of the best options: total immersion, the communicative approach, extensive reading, extensive listening, and spaced repetition.

The Modern Methods of Teaching English

There are several modern methods of teaching English that focus on engaging students and making learning more interactive and effective. Some of these methods include:

Communicative Language Teaching (CLT)

This approach emphasizes communication and interaction as the main goals of language learning. It focuses on real-life situations and encourages students to use English in meaningful contexts.

Task-Based Learning (TBL)

TBL involves designing activities or tasks that require students to use English to complete a specific goal or objective. This approach helps students develop language skills while focusing on the task at hand.

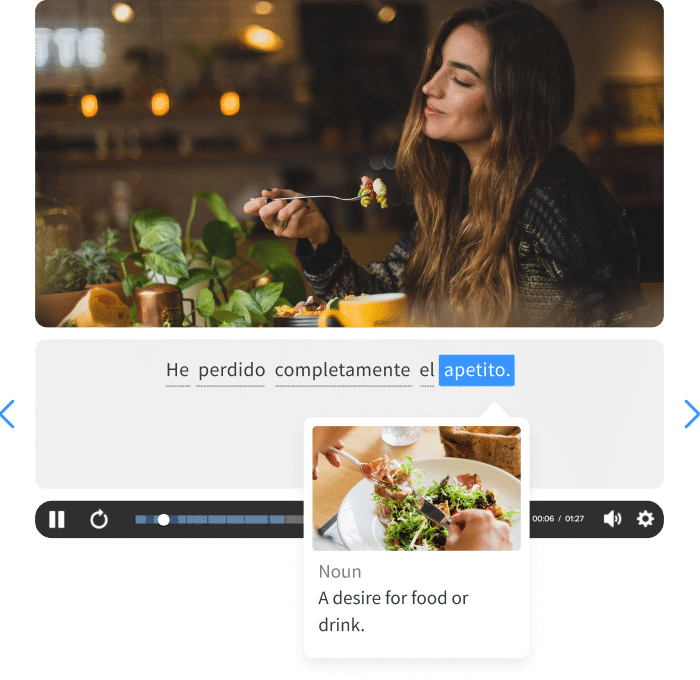

Technology-Enhanced Learning

Using technology such as computers, tablets, and smartphones can make learning more engaging and interactive. Online resources, apps, and educational games can be used to supplement traditional teaching methods.

Flipped Classroom

In a flipped classroom, students learn new material at home through videos or online resources, and then use class time for activities, discussions, and practice exercises. This approach allows for more individualized learning and interaction in the classroom.

Project-Based Learning (PBL)

PBL involves students working on projects or tasks that require them to use English in a real-world context. This approach helps students develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills while improving their language abilities.

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL)

CLIL involves teaching subjects such as science or history in English, rather than teaching English as a separate subject. This approach helps students learn English while also learning about other subjects.

Gamification

Using game elements such as points, badges, and leaderboards can make learning English more fun and engaging. Educational games can help students practice language skills in a playful and interactive way.

These modern methods of teaching English focus on making learning more student-centered, interactive, and engaging, leading to better outcomes for students.

Have your say about Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching

What’s your top pick for a language teaching method? Is it one of the options from this list or do you have another one that you’d like to mention? Leave a comment below and let us know what you think. We’d love to hear from you. And whatever approach or method you use, you’ll want to check out these top 1o tips for new English teachers .

Also, be sure to give this article a share on Facebook, Pinterest, or Twitter. It’ll help other busy teachers, like yourself, find this useful information about approaches and methods in language teaching and learning.

Last update on 2024-04-25 / Affiliate links / Images from Amazon Product Advertising API

About Jackie

Jackie Bolen has been teaching English for more than 15 years to students in South Korea and Canada. She's taught all ages, levels and kinds of TEFL classes. She holds an MA degree, along with the Celta and Delta English teaching certifications.

Jackie is the author of more than 100 books for English teachers and English learners, including 101 ESL Activities for Teenagers and Adults and 1001 English Expressions and Phrases . She loves to share her ESL games, activities, teaching tips, and more with other teachers throughout the world.

You can find her on social media at: YouTube Facebook TikTok Pinterest Instagram

This is wonderful, I have learned a lot!

You’re welcome!

What year did you publish this please?

Recently! Only a few months ago.

Wonderful! Thank you for sharing such useful information. I have learned a lot from them. Thank you!

I am so grateful. Thanks for sharing your kmowledge.

Hi thank you so much for this amazing article. I just wanted to confirm/ask is PPP one of the methods of teaching ESL if so was there a reason it wasn’t included in the article(outdated, not effective etc.?).

PPP is more of a subset of these other ones and not an approach or method in itself.

Good explanation, understandable and clear. Congratulations

That’s good, very short but clear…👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾

I meant the naturalistic approach

This is amazing! Thank you for writing this article, it helped me a lot. I hoped this will reach more people so I will definitely recommend this to others.

Thank you, sir! I just used this article in my PPT presentation at my Post Grad School. More articles from you!

I think this useful because it is teaching me a lot about english. Thank you bro! 😀👍

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Our Top-Seller

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

More ESL Activities

Describing Words that Start with N (“N” Adjectives)

Adjectives with the Letter A | List of A Adjectives

100 Common English Questions and How to Answer Them

Five Letter Words Without Vowels | No Vowel Words

About, contact, privacy policy.

Jackie Bolen has been talking ESL speaking since 2014 and the goal is to bring you the best recommendations for English conversation games, activities, lesson plans and more. It’s your go-to source for everything TEFL!

About and Contact for ESL Speaking .

Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

Email: [email protected]

Address: 2436 Kelly Ave, Port Coquitlam, Canada

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Key Foreign Language Teaching Methods

How do you teach your foreign language students?

Consider for a moment the manners in which you teach reading , writing, listening, speaking, grammar and culture . Why do you use those methods?

In my experience, knowing the history of how your subject has been taught will help you understand your teaching methods.

It will also help you learn to select the best ones for your students at any given moment.

Read on for the most common foreign language teaching methods of today, as well as how to choose which ones to employ.

Grammar-translation

Audio-lingual, total physical response, communicative, task-based learning, community language learning, the silent way, functional-notional, other methods, how to choose a foreign language teaching method.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Those who’ve studied an ancient language like Latin or Sanskrit have likely used this method . It involves learning grammar rules, reading original texts and translating both from and into the target language.

You don’t really learn to speak—although, to be fair, it’s hard to practice speaking languages that have no remaining native speakers.

For the longest time, this approach was also commonly used for teaching modern foreign languages. Though it’s fallen out of favor, there are some benefits to it for occasional use.

- Thousands of learner friendly videos (especially beginners)

- Handpicked, organized, and annotated by FluentU's experts

- Integrated into courses for beginners

With grammar-translation , you might give your students a brief passage in the target language, provide the new vocabulary and give them time to try translating. The reading might include a new verb tense, a new case or a complex grammatical construction.

When it occurs, speaking might only consist of a word or phrase and is typically in the context of completing the exercises. Explanations of the material are in the native language.

After the assignment, you could give students a series of translation sentences or a brief paragraph in the native language for them to translate into the target language as homework.

The direct method , also known as the natural approach, was a response to the grammar-translation method. Here, the emphasis is on the spoken language.

Based on observations of children learning their native tongues, this approach centers on listening and comprehension at the beginning of the language learning process.

Lessons are taught in the target language —in fact, the native language is strictly forbidden. A typical lesson might involve viewing pictures while the teacher repeats the vocabulary words, then listening to recordings of these words used in a comprehensible dialogue.

- Interactive subtitles: click any word to see detailed examples and explanations

- Slow down or loop the tricky parts

- Show or hide subtitles

- Review words with our powerful learning engine

Once students have had time to listen and absorb the sounds of the target language, speaking is encouraged at all times, especially because grammar instruction isn’t taught explicitly.

Rather, students should learn grammar inductively. Allow them to use the language naturally, then gently correct mistakes and give praise to proper language usage. (Note that many have found this method of grammar instruction insufficient.)

Direct method activities might include pantomiming, word-picture association, question-answer patterns, dialogues and role playing.

The theory behind the audio-lingual approach is that repetition is the mother of all learning. This methodology emphasizes drill work in order to make answers to questions instinctive and automatic.

This approach gives highest priority to the spoken form of the target language. New information is first heard by students; written forms come only after extensive drilling. Classes are generally held in the target language.

An example of an audio-lingual activity is a substitution drill. The instructor might start with a basic sentence, such as “I see the ball.” Then they hold up a series of other photos for students to substitute for the word “ball.” These exercises are drilled into students until they get the pronunciations and rhythm right.

The audio-lingual approach borrows from the behaviorist school of psychology, so languages are taught through a system of reinforcement . Reinforcements are anything that makes students feel good about themselves or the situation—clapping, a sticker, etc.

- Learn words in the context of sentences

- Swipe left or right to see more examples from other videos

- Go beyond just a superficial understanding

Full immersion is difficult to achieve in a foreign language classroom—unless, of course, you’re teaching that language in a country where it’s spoken and your students are doing everything in the target language.

For example, ESL students have an immersion experience if they’re studying in an Anglophone country. In addition to studying English, they either work or study other subjects in English for the complete experience.

Attempts at this methodology can be seen in foreign language immersion schools, which are becoming popular in certain districts in the US. The challenge is that, as soon as students leave school, they are once again surrounded by the native language.

One way to get closer to the core of this method is to use an online language immersion program, such as FluentU . The authentic videos are made by and for native speakers and come with a multitude of learning tools.

Expert-vetted, interactive subtitles provide definitions, photo references, example sentences and more. Each lesson contains a quiz personalized to every individual student.

You can also import your own flashcard lists and assign tasks directly to learners with FluentU in order to encourage immersive learning outside of class.

Also known as TPR , this teaching method emphasizes aural comprehension. Gestures and movements play a vital role in this approach.

- FluentU builds you up, so you can build sentences on your own

- Start with multiple-choice questions and advance through sentence building to producing your own output

- Go from understanding to speaking in a natural progression.

Children learning their native language hear lots of commands from adults: “Catch the ball,” “Pick up your toy,” “Drink your water.” TPR aims to teach learners a second language in the same manner with as little stress as possible.

The idea is that when students see movement and move themselves, their brains create more neural connections, which makes for more efficient language acquisition.

In a TPR-based classroom, students are therefore trained to respond to simple commands: stand up, sit down, close the door, open your book, etc.

The teacher might demonstrate what “jump” looks like, for example, and then ask students to perform the action themselves. Or, you might simply play Simon Says!

This style can later be expanded to storytelling , where students act out actions from an oral narrative, demonstrating their comprehension of the language.

The communicative approach is the most widely used and accepted approach to classroom-based foreign language teaching today.

- Images, examples, video examples, and tips

- Covering all the tricky edge cases, eg.: phrases, idioms, collocations, and separable verbs

- No reliance on volunteers or open source dictionaries

- 100,000+ hours spent by FluentU's team to create and maintain

It emphasizes the learner’s ability to communicate various functions, such as asking and answering questions, making requests, describing, narrating and comparing.

Task assignment and problem solving —two key components of critical thinking—are the means through which the communicative approach operates.

A communicative classroom includes activities where students can work out a problem or situation through narration or negotiation—composing a dialogue about when and where to eat dinner, for instance, or creating a story based on a series of pictures.

This helps them establish communicative competence and learn vocabulary and grammar in context. Error correction is de-emphasized so students can naturally develop accurate speech through frequent use. Language fluency comes through communicating in the language rather than by analyzing it.

Task-based learning is a refinement of the communicative approach and focuses on the completion of specific tasks through which language is taught and learned.

The purpose is for language learners to use the target language to complete a variety of assignments. They will acquire new structures, forms and vocabulary as they go. Typically, little error correction is provided.

In a task-based learning environment, three- to four-week segments are devoted to a specific topic, such as ecology, security, medicine, religion, youth culture, etc. Students learn about each topic step-by-step with a variety of resources.

Activities are similar to those found in a communicative classroom, but they’re always based around the theme. A unit often culminates in a final project such as a written report or presentation.

In this type of classroom, the teacher serves as a counselor rather than an instructor.

It’s called community language learning because the class learns together as one unit —not by listening to a lecture, but by interacting in the target language.

For instance, students might sit in a circle. You don’t need a set lesson since this approach is learner-led; the students will decide what they want to talk about.

Someone might say, “Hey, why don’t we talk about the weather?” The student will turn to the teacher ( standing outside the circle ) and ask for the translation of this statement. The teacher will provide the translation and ask the student to say it while guiding their pronunciation.

When the pronunciation is correct, the student will repeat the statement to the group. Another student might then say, “I had to wear three layers today!” And the process repeats.

These conversations are always recorded and then transcribed and mined for lesson continuations featuring grammar, vocabulary and subject-related content.

Proponents of this approach believe that teaching too much can sometimes get in the way of learning. It’s argued that students learn best when they discover rather than simply repeat what the teacher says.

By saying as little as possible, you’re encouraging students to do the talking themselves to figure out the language. This is seen as a creative, problem-solving process —an engaging cognitive challenge.

So how does one teach in silence ?

You’ll need to employ plenty of gestures and facial expressions to communicate with your students.

You can also use props. A common prop is Cuisenaire Rods —rods of different colors and lengths. Pick one up and say “rod.” Pick another, point at it and say “rod.” Repeat until students understand that “rod” refers to these objects.

Then, you could pick a green one and say “green rod.” With an economy of words, point to something else green and say, “green.” Repeat until students get that “green” refers to the color.

The functional-notional approach recognizes language as purposeful communication. That is, we use it because we need to communicate something.

Various parts of speech exist because we need them to express functions like informing, persuading, insinuating, agreeing, questioning, requesting, evaluating, etc. We also need to express notions (concepts) such as time, events, action, place, technology, process, emotion, etc.

Teachers using the functional-notional method must evaluate how the students will be using the language .

For example, very young kids need language skills to help them communicate with their parents and friends. Key social phrases like “thank you,” “please” or “may I borrow” are ideal here.

For business professionals, you might want to teach the formal forms of the target language, how to delegate tasks and how to vocally appreciate a job well done. Functions could include asking a question, expressing interest or negotiating a deal. Notions could be prices, quality or quantity.

You can teach grammar and sentence patterns directly, but they’re always subsumed by the purpose for which the language will be used.

A student who wants to learn with the reading method probably never intends to interact with native speakers in the target language.

Perhaps they’re a graduate student who simply needs to read scholarly articles. Maybe they’re a culinary student who only wants to understand the French techniques in her cookbook.

Whoever it is, these students only require one linguistic skill: reading comprehension.

Do away with pronunciation and dialogues. No need to practice listening or speaking, or even much (if any) writing.

With the reading approach, simply help your students build their vocabulary. They’ll likely need a lot of specialized words in a specific field, though they’ll also need to know elements like conjunctions and negation—enough grammar to make it through a standard article in their field.

These approaches are not necessarily as common in the classroom setting but deserve a mention nonetheless:

- Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL): A number of commercial products ( Pimsleur , Rosetta Stone ) and online products ( Duolingo , Babbel ) use the CALL method. With careful planning, you can likely employ some in the classroom as well.

- Cognitive-code: Developed in response to the audio-lingual method , this approach requires essential language structures to be explicitly laid out in examples (dialogues, readings) by the teacher, with lots of opportunities for students to practice .

- Suggestopedia: The idea here is that the more relaxed and comfortable students feel, the more open they are to learning , which therefore makes language acquisition easier.

Now that you know a number of methodologies and how to use them in the classroom, how do you choose the best?

You should always try to choose the methods and approaches that are most effective for your students. After all, our job as teachers is to help our students to learn in the best way for them— not for us or for researchers or for administrators.

So, the best teachers choose the best methodology and the best approach for each lesson or activity. They aren’t wedded to any particular methodology but rather use principled eclecticism:

- Ever taught a grammatical construction that only appears in written form? Had your students practice it by writing? Then you’ve used the grammar-translation method.

- Ever talked to your students in question/answer form, hoping they’d pick up the grammar point? Then you’ve used the direct method.

- Every repeatedly drilled grammatical endings, or numbers, or months, perhaps before showing them to your students? Then you’ve used the audio-lingual method.

- Ever played Simon Says? Or given your students commands to open their textbook to a certain page? Then you’ve used the total physical response method.

- Ever written a thematic unit on a topic not covered by the textbook, incorporating all four skills and culminating in a final assignment? Then you’ve used task-based learning.

If you’ve already done all of these, then you’re already practicing principled eclecticism!

The point is: The best teachers make use of all possible approaches at the appropriate time, for the appropriate activities and for those students whose learning styles require that approach.

The ultimate goal is to choose the foreign language teaching methods that best fit your students, not to force them to adhere to a particular or method.

Remember: Teaching is always about our students! You got this!

Related posts:

Enter your e-mail address to get your free pdf.

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

- MoraModules

Second and Foreign Language Teaching Methods

This module provides a description of the basic principles and procedures of the most recognized and commonly used approaches and methods for teaching a second or foreign language. Each approach or method has an articulated theoretical orientation and a collection of strategies and learning activities designed to reach the specified goals and achieve the learning outcomes of the teaching and learning processes.

Jill Kerper Mora

The following approaches and methods are described below:

Grammar-Translation Approach

Direct Approach

Reading Approach

Audiolingual Approach

Community Language Learning

The silent way.

The Communicative Approach

Functional Notional Approach

Total Physical Response Approach

The Natural Approach

Click here for a link to an overview of the history of second or foreign language teaching .

Theoretical Orientations to L2 Methods & Approaches

There are four general orientations among modern second-language methods and approaches:

1. STRUCTURAL/LINGUISTIC : Based on beliefs about the structure of language and descriptive or contrastive linguistics. Involves isolation of grammatical and syntactic elements of L2 taught either deductively or inductively in a predetermined sequence. Often involves much meta-linguistic content or “learning about the language” in order to learn the language.

2. COGNITIVE : Based on theories of learning applied specifically to second language learning. Focus is on the learning strategies that are compatible with the learners own style. L2 content is selected according to concepts and techniques that facilitate generalizations about the language, memorization and “competence” leading to “performance”.

3. AFFECTIVE/INTERPERSONAL: Focuses on the psychological and affective pre-dispositions of the learner that enhance or inhibit learning. Emphasizes interaction among and between teacher and students and the atmosphere of the learning situation as well as students’ motivation for learning. Based on concepts adapted from counseling and social psychology.

4. FUNCTIONAL/COMMUNICATIVE : Based on theories of language acquisition, often referred to as the “natural” approach, and on the use of language for communication. Encompasses multiple aspects of the communicative act, with language structures selected according to their utility in achieving a communicative purpose. Instruction is concerned with the input students receive, comprehension of the “message” of language and student involvement at the students’ level of competence.

The Grammar-Translation Approach

This approach was historically used in teaching Greek and Latin. The approach was generalized to teaching modern languages.

Classes are taught in the students’ mother tongue, with little active use of the target language. Vocabulary is taught in the form of isolated word lists. Elaborate explanations of grammar are always provided. Grammar instruction provides the rules for putting words together; instruction often focuses on the form and inflection of words. Reading of difficult texts is begun early in the course of study. Little attention is paid to the content of texts, which are treated as exercises in grammatical analysis. Often the only drills are exercises in translating disconnected sentences from the target language into the mother tongue, and vice versa. Little or no attention is given to pronunciation.

The Direct Approach

This approach was developed initially as a reaction to the grammar-translation approach in an attempt to integrate more use of the target language in instruction.

Lessons begin with a dialogue using a modern conversational style in the target language. Material is first presented orally with actions or pictures. The mother tongue is NEVER, NEVER used. There is no translation. The preferred type of exercise is a series of questions in the target language based on the dialogue or an anecdotal narrative. Questions are answered in the target language. Grammar is taught inductively–rules are generalized from the practice and experience with the target language. Verbs are used first and systematically conjugated only much later after some oral mastery of the target language. Advanced students read literature for comprehension and pleasure. Literary texts are not analyzed grammatically. The culture associated with the target language is also taught inductively. Culture is considered an important aspect of learning the language.

The Reading Approach

This approach is selected for practical and academic reasons. For specific uses of the language in graduate or scientific studies. The approach is for people who do not travel abroad for whom reading is the one usable skill in a foreign language.

The priority in studying the target language is first, reading ability and second, current and/or historical knowledge of the country where the target language is spoken.Only the grammar necessary for reading comprehension and fluency is taught. Minimal attention is paid to pronunciation or gaining conversational skills in the target language. From the beginning, a great amount of reading is done in L2, both in and out of class. The vocabulary of the early reading passages and texts is strictly controlled for difficulty. Vocabulary is expanded as quickly as possible, since the acquisition of vocabulary is considered more important that grammatical skill.Translation reappears in this approach as a respectable classroom procedure related to comprehension of the written text.

The Audiolingual Method

This method is based on the principles of behavior psychology. It adapted many of the principles and procedures of the Direct Method, in part as a reaction to the lack of speaking skills of the Reading Approach.

New material is presented in the form of a dialogue. Based on the principle that language learning is habit formation, the method fosters dependence on mimicry, memorization of set phrases and over-learning. Structures are sequenced and taught one at a time. Structural patterns are taught using repetitive drills. Little or no grammatical explanations are provided; grammar is taught inductively. Skills are sequenced: Listening, speaking, reading and writing are developed in order.Vocabulary is strictly limited and learned in context. Teaching points are determined by contrastive analysis between L1 and L2. There is abundant use of language laboratories, tapes and visual aids. There is an extended pre-reading period at the beginning of the course. Great importance is given to precise native-like pronunciation. Use of the mother tongue by the teacher is permitted, but discouraged among and by the students. Successful responses are reinforced; great care is taken to prevent learner errors. There is a tendency to focus on manipulation of the target language and to disregard content and meaning.

Hints for Using Audio-lingual Drills in L2 Teaching

1. The teacher must be careful to insure that all of the utterances which students will make are actually within the practiced pattern. For example, the use of the AUX verb have should not suddenly switch to have as a main verb.

2. Drills should be conducted as rapidly as possibly so as to insure automaticity and to establish a system.

3. Ignore all but gross errors of pronunciation when drilling for grammar practice.

4. Use of shortcuts to keep the pace o drills at a maximum. Use hand motions, signal cards, notes, etc. to cue response. You are a choir director.

5. Use normal English stress, intonation, and juncture patterns conscientiously.

6. Drill material should always be meaningful. If the content words are not known, teach their meanings.

7. Intersperse short periods of drill (about 10 minutes) with very brief alternative activities to avoid fatigue and boredom.

8. Introduce the drill in this way:

a. Focus (by writing on the board, for example)

b. Exemplify (by speaking model sentences)

c. Explain (if a simple grammatical explanation is needed)

9. Don’t stand in one place; move about the room standing next to as many different students as possible to spot check their production. Thus you will know who to give more practice to during individual drilling.

10. Use the “backward buildup” technique for long and/or difficult patterns.

–tomorrow

–in the cafeteria tomorrow

–will be eating in the cafeteria tomorrow

–Those boys will be eating in the cafeteria tomorrow.

11. Arrange to present drills in the order of increasing complexity of student response. The question is: How much internal organization or decision making must the student do in order to make a response in this drill. Thus: imitation first, single-slot substitution next, then free response last.

Curran, C.A. (1976). Counseling-Learning in Second Languages . Apple River, Illinois: Apple River Press, 1976.

This methodology created by Charles Curran is not based on the usual methods by which languages are taught. Rather the approach is patterned upon counseling techniques and adapted to the peculiar anxiety and threat as well as the personal and language problems a person encounters in the learning of foreign languages. Consequently, the learner is not thought of as a student but as a client. The native instructors of the language are not considered teachers but, rather are trained in counseling skills adapted to their roles as language counselors.

The language-counseling relationship begins with the client’s linguistic confusion and conflict. The aim of the language counselor’s skill is first to communicate an empathy for the client’s threatened inadequate state and to aid him linguistically. Then slowly the teacher-counselor strives to enable him to arrive at his own increasingly independent language adequacy. This process is furthered by the language counselor’s ability to establish a warm, understanding, and accepting relationship, thus becoming an “other-language self” for the client. The process involves five stages of adaptation:

The client is completely dependent on the language counselor.

1. First, he expresses only to the counselor and in English what he wishes to say to the group. Each group member overhears this English exchange but no other members of the group are involved in the interaction.

2. The counselor then reflects these ideas back to the client in the foreign language in a warm, accepting tone, in simple language in phrases of five or six words.

3. The client turns to the group and presents his ideas in the foreign language. He has the counselor’s aid if he mispronounces or hesitates on a word or phrase. This is the client’s maximum security stage.

1. Same as above.

2. The client turns and begins to speak the foreign language directly to the group.

3. The counselor aids only as the client hesitates or turns for help. These small independent steps are signs of positive confidence and hope.

1. The client speaks directly to the group in the foreign language. This presumes that the group has now acquired the ability to understand his simple phrases.

2. Same as 3 above. This presumes the client’s greater confidence, independence, and proportionate insight into the relationship of phrases, grammar, and ideas. Translation is given only when a group member desires it.

1. The client is now speaking freely and complexly in the foreign language. Presumes group’s understanding.

2. The counselor directly intervenes in grammatical error, mispronunciation, or where aid in complex expression is needed. The client is sufficiently secure to take correction.

1. Same as stage 4.

2. The counselor intervenes not only to offer correction but to add idioms and more elegant constructions.

3. At this stage the client can become counselor to the group in stages 1, 2, and 3.

Gattegno, C. (1972). Teaching Foreign Languages in Schools: The Silent Way . New York City: Educational Solutions.

This method created by Caleb Gattegno begins by using a set of colored rods and verbal commands in order to achieve the following:

To avoid the use of the vernacular. To create simple linguistic situations that remain under the complete control of the teacher To pass on to the learners the responsibility for the utterances of the descriptions of the objects shown or the actions performed. To let the teacher concentrate on what the students say and how they are saying it, drawing their attention to the differences in pronunciation and the flow of words. To generate a serious game-like situation in which the rules are implicitly agreed upon by giving meaning to the gestures of the teacher and his mime. To permit almost from the start a switch from the lone voice of the teacher using the foreign language to a number of voices using it. This introduces components of pitch, timbre and intensity that will constantly reduce the impact of one voice and hence reduce imitation and encourage personal production of one’s own brand of the sounds.

To provide the support of perception and action to the intellectual guess of what the noises mean, thus bring in the arsenal of the usual criteria of experience already developed and automatic in one’s use of the mother tongue. To provide a duration of spontaneous speech upon which the teacher and the students can work to obtain a similarity of melody to the one heard, thus providing melodic integrative schemata from the start.

The complete set of materials utilized as the language learning progresses include:

A set of colored wooden rods A set of wall charts containing words of a “functional” vocabulary and some additional ones; a pointer for use with the charts in Visual Dictation A color coded phonic chart(s) Tapes or discs, as required; films Drawings and pictures, and a set of accompanying worksheets Transparencies, three texts, a Book of Stories, worksheets.

The Communicative Approach

What is communicative competence?

- Communicative competence is the progressive acquisition of the ability to use a language to achieve one’s communicative purpose.

- Communicative competence involves the negotiation of meaning between meaning between two or more persons sharing the same symbolic system.

- Communicative competence applies to both spoken and written language.

- Communicative competence is context specific based on the situation, the role of the participants and the appropriate choices of register and style. For example: The variation of language used by persons in different jobs or professions can be either formal or informal. The use of jargon or slang may or may not be appropriate.

- Communicative competence represents a shift in focus from the grammatical to the communicative properties of the language; i.e. the functions of language and the process of discourse.

- Communicative competence requires the mastery of the production and comprehension of communicative acts or speech acts that are relevant to the needs of the L2 learner.

Characteristics of the Communicative Classroom

- The classroom is devoted primarily to activities that foster acquisition of L2. Learning activities involving practice and drill are assigned as homework.

- The instructor does not correct speech errors directly.

- Students are allowed to respond in the target language, their native language, or a mixture of the two.

- The focus of all learning and speaking activities is on the interchange of a message that the acquirer understands and wishes to transmit, i.e. meaningful communication.

- The students receive comprehensible input in a low-anxiety environment and are personally involved in class activities. Comprehensible input has the following major components:

a. a context

b. gestures and other body language cues

c. a message to be comprehended

d. a knowledge of the meaning of key lexical items in the utterance

Stages of language acquisition in the communicative approach

1. Comprehension or pre-production

a. Total physical response

b. Answer with names–objects, students, pictures

2. Early speech production

a. Yes-no questions

b. Either-or questions

c. Single/two-word answers

d. Open-ended questions

e. Open dialogs

f. Interviews

3. Speech emerges

a. Games and recreational activities

b. Content activities

c. Humanistic-affective activities

d. Information-problem-solving activities

Functional-Notional Approach

Finocchiaro, M. & Brumfit, C. (1983). The Functional-Notional Approach . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

This method of language teaching is categorized along with others under the rubric of a communicative approach. The method stresses a means of organizing a language syllabus. The emphasis is on breaking down the global concept of language into units of analysis in terms of communicative situations in which they are used.

Notions are meaning elements that may be expressed through nouns, pronouns, verbs, prepositions, conjunctions, adjectives or adverbs. The use of particular notions depends on three major factors: a. the functions b. the elements in the situation, and c. the topic being discussed.

A situation may affect variations of language such as the use of dialects, the formality or informality of the language and the mode of expression. Situation includes the following elements:

A. The persons taking part in the speech act

B. The place where the conversation occurs

C. The time the speech act is taking place

D. The topic or activity that is being discussed

Exponents are the language utterances or statements that stem from the function, the situation and the topic.

Code is the shared language of a community of speakers.

Code-switching is a change or switch in code during the speech act, which many theorists believe is purposeful behavior to convey bonding, language prestige or other elements of interpersonal relations between the speakers.

Functional Categories of Language

Mary Finocchiaro (1983, p. 65-66) has placed the functional categories under five headings as noted below: personal, interpersonal, directive, referential, and imaginative.

Personal = Clarifying or arranging one’s ideas; expressing one’s thoughts or feelings: love, joy, pleasure, happiness, surprise, likes, satisfaction, dislikes, disappointment, distress, pain, anger, anguish, fear, anxiety, sorrow, frustration, annoyance at missed opportunities, moral, intellectual and social concerns; and the everyday feelings of hunger, thirst, fatigue, sleepiness, cold, or warmth

Interpersonal = Enabling us to establish and maintain desirable social and working relationships: Enabling us to establish and maintain desirable social and working relationships:

- greetings and leave takings

- introducing people to others

- identifying oneself to others

- expressing joy at another’s success

- expressing concern for other people’s welfare

- extending and accepting invitations

- refusing invitations politely or making alternative arrangements

- making appointments for meetings

- breaking appointments politely and arranging another mutually convenient time

- apologizing

- excusing oneself and accepting excuses for not meeting commitments

- indicating agreement or disagreement

- interrupting another speaker politely

- changing an embarrassing subject

- receiving visitors and paying visits to others

- offering food or drinks and accepting or declining politely

- sharing wishes, hopes, desires, problems

- making promises and committing oneself to some action

- complimenting someone

- making excuses

- expressing and acknowledging gratitude

Directive = Attempting to influence the actions of others; accepting or refusing direction:

- making suggestions in which the speaker is included

- making requests; making suggestions

- refusing to accept a suggestion or a request but offering an alternative

- persuading someone to change his point of view

- requesting and granting permission

- asking for help and responding to a plea for help

- forbidding someone to do something; issuing a command

- giving and responding to instructions

- warning someone

- discouraging someone from pursuing a course of action

- establishing guidelines and deadlines for the completion of actions

- asking for directions or instructions

Referential = talking or reporting about things, actions, events, or people in the environment in the past or in the future; talking about language (what is termed the metalinguistic function: = talking or reporting about things, actions, events, or people in the environment in the past or in the future; talking about language (what is termed the metalinguistic function:

- identifying items or people in the classroom, the school the home, the community

- asking for a description of someone or something

- defining something or a language item or asking for a definition

- paraphrasing, summarizing, or translating (L1 to L2 or vice versa)

- explaining or asking for explanations of how something works

- comparing or contrasting things

- discussing possibilities, probabilities, or capabilities of doing something

- requesting or reporting facts about events or actions

- evaluating the results of an action or event

Imaginative = Discussions involving elements of creativity and artistic expression

- discussing a poem, a story, a piece of music, a play, a painting, a film, a TV program, etc.

- expanding ideas suggested by other or by a piece of literature or reading material

- creating rhymes, poetry, stories or plays

- recombining familiar dialogs or passages creatively

- suggesting original beginnings or endings to dialogs or stories

- solving problems or mysteries

Total Physical Response

Asher, J.C. (1979). Learning Another Language Through Actions . San Jose, California: AccuPrint.

James J. Asher defines the Total Physical Response (TPR) method as one that combines information and skills through the use of the kinesthetic sensory system. This combination of skills allows the student to assimilate information and skills at a rapid rate. As a result, this success leads to a high degree of motivation. The basic tenets are:

Understanding the spoken language before developing the skills of speaking. Imperatives are the main structures to transfer or communicate information. The student is not forced to speak, but is allowed an individual readiness period and allowed to spontaneously begin to speak when the student feels comfortable and confident in understanding and producing the utterances.

Step I The teacher says the commands as he himself performs the action.

Step 2 The teacher says the command as both the teacher and the students then perform the action.

Step 3 The teacher says the command but only students perform the action

Step 4 The teacher tells one student at a time to do commands

Step 5 The roles of teacher and student are reversed. Students give commands to teacher and to other students.

Step 6 The teacher and student allow for command expansion or produces new sentences.

The Natural Approach and the Communicative Approach share a common theoretical and philosophical base.The Natural Approach to L2 teaching is based on the following hypotheses:

1. The acquisition-learning distinction hypothesis

Adults can “get” a second language much as they learn their first language, through informal, implicit, subconscious learning. The conscious, explicit, formal linguistic knowledge of a language is a different, and often non-essential process.

2. The natural order of acquisition hypothesis

L2 learners acquire forms in a predictable order. This order very closely parallels the acquisition of grammatical and syntactic structures in the first language.

3. The monitor hypothesis

Fluency in L2 comes from the acquisition process. Learning produces a “monitoring” or editor of performance. The application of the monitor function requires time, focus on form and knowledge of the rule .

4. The input hypothesis

Language is acquired through comprehensible input. If an L2 learner is at a certain stage in language acquisition and he/she understands something that includes a structure at the next stage, this helps him/her to acquire that structure. Thus, the i+1 concept, where i= the stage of acquisition.

5. The affective hypothesis

People with certain personalities and certain motivations perform better in L2 acquisition. Learners with high self-esteem and high levels of self-confidence acquire L2 faster. Also, certain low-anxiety pleasant situations are more conducive to L2 acquisition.

6. The filter hypothesis

There exists an affective filter or “mental block” that can prevent input from “getting in.” Pedagogically, the more that is done to lower the filter, the more acquisition can take place. A low filter is achieved through low-anxiety, relaxation, non-defensiveness.

7. The aptitude hypothesis

There is such a thing as a language learning aptitude. This aptitude can be measured and is highly correlated with general learning aptitude. However, aptitude relates more to learning while attitude relates more to acquisition .

8. The first language hypothesis

The L2 learner will naturally substitute competence in L1 for competence in L2. Learners should not be forced to use the L1 to generate L2 performance. A silent period and insertion of L1 into L2 utterances should be expected and tolerated.

9. The textuality hypothesis

The event-structures of experience are textual in nature and will be easier to produce, understand, and recall to the extent that discourse or text is motivated and structured episodically. Consequently, L2 teaching materials are more successful when they incorporate principles of good story writing along with sound linguistic analysis.

10. The expectancy hypothesis

Discourse has a type of “cognitive momentum.” The activation of correct expectancies will enhance the processing of textual structures. Consequently, L2 learners must be guided to develop the sort of native-speaker “intuitions” that make discourse predictable.

Source: Krashen, S.D. , & Terrell, T.D. (1983). The Natural Approach . Hayward, CA: The Alemany Press.

Click here for a PPT slide presentation on the Theoretical Basis for the Natural Approach

- Study Guides

- Mission Statement

- Dr. Mora’s Book

- Professional Development

- Testimonials

- Bilingual Education

- Biliteracy Instruction

- ELD/SDAIE Instruction

- ESL/EFL Teaching Methods

- Thematic Planning for ELD

- Getting Started

- Introduction

- The Teacher

- The Learner

Foreign Language Teaching Methods: Introduction

- Meet the Class

The online course is designed to give you the virtual experience of participating in the methods course alongside a diverse group of beginning foreign language teachers. A rich, interactive experience is facilitated by multimedia content, including

- footage of the actual methods course,

- videos of actual foreign language classrooms,

- self-correcting exercises,

- portfolios of sample activities, and

- interviews with beginning teachers.

The site is divided into 12 modules, each focusing on one important aspect of language teaching, and each based primarily on a single class within the methods course. Within each module, the sequencing of content mirrors the real-life class—as you progress through the module, you are presented with the same material, looking at the same examples, completing the same tasks, and "sitting in" on the classroom discussions of the material. Take a moment to go on a virtual tour of the site to familiarize yourself with the structure and features.

Demonstration of the structure and features of this site.

Duration: 04:33

Flash player not found. Play in new window.

Each module ends by showing how the beginning teachers put into practice what they learned by creating real activities and lesson plans. The design of this course gives you the opportunity to compare your own ideas to those of other teachers with an ultimate goal of bringing new methods and teaching practices back into your own classroom.

Tell us what you think and help us improve this page.

Send a comment

Name (optional)

Email (optional)

Comment or Message

CC BY-NC-SA 2010 | COERLL | UT Austin | Copyright & Legal | Help | Credits | Contact

CC BY-NC-SA | 2010 | COERLL | UT Austin | http://coerll.utexas.edu/methods

PPP TEFL Teaching Methodology

What is presentation, practice and production (ppp).

During your SEE TEFL certification course you will become more familiar with an established methodology for teaching English as a foreign language known as 3Ps or PPP – presentation, practice, production. The PPP method could be characterized as a common-sense approach to teaching as it consists of 3 stages that most people who have learnt how to do anything will be familiar with.

The first stage is the presentation of an aspect of language in a context that students are familiar with, much the same way that a swimming instructor would demonstrate a stroke outside the pool to beginners.

The second stage is practice, where students will be given an activity that gives them plenty of opportunities to practice the new aspect of language and become familiar with it whilst receiving limited and appropriate assistance from the teacher. To continue with the analogy, the swimming instructor allowing the children to rehearse the stroke in the pool whilst being close enough to give any support required and plenty of encouragement.

The final stage is production where the students will use the language in context, in an activity set up by the teacher who will be giving minimal assistance, like the swimming instructor allowing his young charges to take their first few tentative strokes on their own.

Advantages of the PPP (3Ps) Method

As with any well-established methodology, PPP has its critics and a couple of relatively new methodologies are starting to gain in popularity such as TBL (task based learning) and ESA (engage, study, activate) . However, even strong advocates of these new methodologies do concede that new EFL (English as a foreign language) teachers find the PPP methodology easiest to grasp, and that these new teachers, once familiar with the PPP methodology, are able to use TBL and ESA more effectively than new trainees that are only exposed to either TBL or ESA.

Indeed, there are strong arguments to suggest that experienced teachers trained in PPP use many aspects of TBL and ESA in their lessons, and that these new methodologies are in truth, the PPP methodology with some minor adjustments.

At this stage you might well be asking, It’s all very well having a clear methodology for how to teach but how do I know what to teach? The language that we call English today has absorbed a great many influences over the last thousand years or so. It has resulted in it becoming a language that can provide us with a sparklingly witty pop culture reference from a Tarantino script, 4 simple words spoken by Dr. Martin Luther King that continue to inspire us today, and something as simple and mundane as a road traffic sign.

The Job of the EFL Teacher

As EFL teachers our job is to break down this rich and complex language into manageable chunks for our students. These chunks of language are what EFL teachers call target languageWe are going to look at an example of what a piece of target language might be and then you will be given more detail on how this would be taught in a PPP lesson before finally watching three videos with some key aspects of each stage of the lesson highlighted for you.

During the course we will spend a great deal of time in the training room equipping you with the tools to employ a successful methodology for teaching the English language. You are going to get opportunities to both hone these skills in the training room and put them into practice in authentic classroom settings.

Of course you might be thinking, I don’t have any experience of being in a classroom! How on earth am I going to cope with standing at the front of a class with 20 plus pairs of eyes looking at me waiting to see what I do?

All good TEFL courses are designed to train those with no teaching experience whatsoever. We will spend the first part of the course in the training room making you familiar with all the new skills you will need whilst giving you opportunities to practice them in a supported and controlled environment.

Only after that, will you be put in an authentic classroom environment. It goes without saying that the first time anybody stands up and delivers their first lesson will be a nerve-racking experience. However, it is also an experience that mellows over time, and one that all teachers remember fondly as time goes by and they feel more at home in a classroom.

There will be some of you out there with experience of teaching in a classroom already. You may be well versed in employing many different methodologies and strategies in your classroom already, but many or most will have been with native English speaking students, or those with a near-native levels of English. This means that some of the skills we will be equipping you with may feel a little alien at first, but your experience will not prove to be a hindrance. Indeed, you will already have successful classroom management skills that can be adapted to fit a second language classroom fairly easily and other trainees on the course will benefit from your presence.

In addition, some of the skills that you will learn on the course can also be adapted to work in a classroom of native speakers too, and it is not unusual for experienced teachers to comment on exactly this after completing a good TEFL course.

Target Language in an EFL Lesson

Recall how it is the job of the EFL teacher to break down the rich tapestry of the English language into manageable bite-size chunks, suitable for study in an average study period of 50 minutes. As mentioned, we refer to these chunks as target language. As EFL teachers we will select target language that is appropriate for both the skill level and the age of the students.

The target language that you will see being presented in the videos is Likes and dislikes for 6 food items.

The teacher you will watch in the video has a clear aim, which is to ensure that:

**By the end of the lesson, students will know the names of 6 food items in English and will be able to express whether or not they like them in a spoken form by entering into a simple dialogue consisting of,

- Do you like ___?,

- Yes, I like ___., or

- No, I don’t like ___.

The six food items are ___. In short, the students will be able to name the 6 food items by the end of the lesson and tell whether they like them or not.**

Presentation – Part 1 of PPP

You may have delivered a few presentations in your time but the type of presentation we deliver in a second language classroom will differ quite a bit from those. For a start, you were speaking to proficient users of the English language about something they were, most likely, vaguely familiar with anyway. In an EFL classroom we don’t have those luxuries, so we have to be careful about the language we use and how clearly we present the new language that we wish for our students to acquire.

Let’s look at 4 key things that should be occurring in an effective second language classroom presentation:

1 – Attention in the Classroom

Learners are alert, have focused their attention on the new language and are responsive to cues that show them that something new is coming up. A simple way to ensure some of the above is if the teacher makes the target language interesting to the students.

The language will of course, be of more interest to the students if it is put into some type of context that the students are familiar with. In the case of likes and dislikes for young learners a visual associated with a facial expression will be something they can relate to. Naturally, the easier it is for them to relate to the context, the more likely they are to be interested in the language presented.

In the case of the target language for the videos a smiley face visual and a sad face visual on the whiteboard linked to the phrases I like ___. and I don’t like ___., respectively. A teacher might make exaggerated facial expressions whilst presenting these ideas to make the ideas both fun and easy to perceive for the students. This is often referred to as contextualization in EFL classrooms.

2 – Perception and Grading of Language

We want to ensure that the learners both see and hear the target language easily. So if a whiteboard is being used, it should be well organized with different colors being used to differentiate between different ideas. If images are being used, there should be no ambiguity as to what they represent and sounds made by the teacher should not only be clear, but should be repeated and the teacher needs to check the material has been perceived correctly, and can do this by asking the students to repeat the sounds he or she is making.

Learners will be bombarded with a series of images corresponding to sounds made by the teacher during the presentation stage and it is the teacher’s responsibility to ensure that they are not overloaded with information and that clear links are being made between the images and the associated sounds.

Therefore, there is an onus on the teacher not to use any unnecessary language at this stage. That is to say the grading of their language should be appropriate for the level of their students and the language they use should consist of the target language and any other essential language required to present the ideas clearly such as commands like listen! The commands should, whenever possible, be supported by clear body language.

3 – Target Language Understanding

The learners must be able to understand the meaning of the material. So in the case of likes and dislikes they perhaps need to see an image of a happy face and associate it with liking something and a sad face and associate that with disliking something.

We also need to have a way of checking if the learners did indeed, understand the material presented without asking the question, Do you understand? as this invariably triggers the response yes! from learners who are keen to please their teacher and not to lose face. We, as teachers, need to be a little more imaginative in checking our student’s understanding of material presented. Ideally, we should be checking the learners’ understanding in context. In the videos you will see, expect to see the teacher doing this during the presentation stage.

4 – Short-term Memory in the Classroom