An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley Open Access Collection

The contagious impact of playing violent video games on aggression: Longitudinal evidence

Tobias greitemeyer.

1 Department of Psychology, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck Austria

Meta‐analyses have shown that violent video game play increases aggression in the player. The present research suggests that violent video game play also affects individuals with whom the player is connected. A longitudinal study ( N = 980) asked participants to report on their amount of violent video game play and level of aggression as well as how they perceive their friends and examined the association between the participant's aggression and their friends’ amount of violent video game play. As hypothesized, friends’ amount of violent video game play at Time 1 was associated with the participant's aggression at Time 2 even when controlling for the impact of the participant's aggression at Time 1. Mediation analyses showed that friends’ aggression at Time 1 accounted for the impact of friends’ amount of violent video game play at Time 1 on the participant's aggression at Time 2. These findings suggest that increased aggression in video game players has an impact on the player's social network.

1. INTRODUCTION

Given its widespread use, the public and psychologists alike are concerned about the impact of violent video game play. In fact, a great number of studies have addressed the effects of exposure to violent video games (where the main goal is to harm other game characters) on aggression and aggression‐related variables. Meta‐analyses have shown that playing violent video games is associated with increased aggression in the player (Anderson et al., 2010 ; Greitemeyer & Mügge, 2014 ). The present longitudinal study examines the idea that violent video game play also affects the player's social network, suggesting that concern about the harmful effects of playing violent video games on a societal level is even more warranted.

1.1. Theoretical perspective

When explaining the effects of playing violent video games, researchers often refer to the General Aggression Model (GAM) proposed by Anderson & Bushman ( 2002 ). According to this theoretical model, person and situation variables (sometimes interactively) may affect a person's internal state, consisting of cognition, affect, and arousal. This internal state then affects how events are perceived and interpreted. Based on this decision process, the person behaves more or less aggressively in a social encounter. For example, playing violent video games is assumed to increase aggressive cognition and affect, which in turn results in behavioral aggression. An extension of this model further assumes that increased aggression due to previous violent video game play may instigate an aggression escalation cycle in that the victim also behaves aggressively (cf. Anderson & Bushman, 2018 , Figure 5). The present research tested key predictions derived from the GAM and its extension, that (a) violent video game play is associated with increased aggression in the player and that (b) individuals who are connected to the player will also become more aggressive.

1.2. Effects of violent video game play on aggression

The relationship between violent video game play and aggression has been examined in studies employing cross‐sectional, longitudinal, and experimental designs. Cross‐sectional correlational studies typically show a positive relationship between the amount of violent video game play and aggression in real‐world contexts (e.g., Gentile, Lynch, Linder, & Walsh, 2004 ; Krahé & Möller, 2004 ). Several longitudinal studies have been conducted, showing that habitual violent video game play predicts later aggression even after controlling for initial aggressiveness (e.g., Anderson, Buckley, & Carnagey, 2008 ). That violent video game play has a causal impact on aggression and related information processing has been demonstrated by experimental work (e.g., Anderson & Carnagey, 2009 ; Gabbiadini & Riva, 2018 ). Finally, meta‐analyses corroborated that violent video game play significantly increases aggressive thoughts, hostile affect, and aggressive behavior (Anderson et al., 2010 ; Greitemeyer & Mügge, 2014 ). Some studies failed to find significant effects (e.g., McCarthy, Coley, Wagner, Zengel, & Basham, 2016 ). However, given that the typical effect of violent video games on aggression is not large, it is to be expected that not all studies reveal significant effects.

1.3. The contagious effects of aggression

Abundant evidence has been collected that aggression and violence can be contagious (Dishion, & Tipsord, 2011 ; Huesmann, 2012 ; Jung, Busching, & Krahé, 2019 ). Indeed, the best predictor of (retaliatory) aggression is arguably previous violent victimization (Anderson et al., 2008 ; Goldstein, Davis, & Herman, 1975 ). However, even the observation of violence can lead to increased violence in the future (Widom, 1989 ). Overall, it is a well‐known finding that aggression begets further aggression. Given that violent video game play increases aggression, it thus may well be that this increased aggression then has an impact on people with whom the player is connected.

Correlational research provides initial evidence for the idea that the level of people's aggression is indeed associated with how often their friends play violent video games (Greitemeyer, 2018 ). In particular, participants who did not play violent video games were more aggressive the more their friends played violent video games. However, due to the cross‐sectional design, no conclusions about the direction of the effect are possible. It may be that violent video game players influence their friends (social influence), but it is also conceivable that similar people attract each other (homophily) or that there is some shared environmental factor that influences the behavior of both the players and their friends (confounding). That is, it is unclear whether indeed aggression due to playing violent video games spreads or whether the effect is reversed, such that aggressive people are prone to befriend others who are attracted to violent video game play. Moreover, it is possible that some third variable affected both, participants’ reported aggression and their friends’ amount of violent video game play. There is also the possibility that people are unsure about the extent to which their friends play violent video games. In this case, they may perceive their friends as behaving aggressively and then (wrongly) infer that the friends play violent video games. To disentangle these possibilities and to show that the effect of violent video game play (i.e., increased aggression in the player) indeed has an impact on the player's social network, relationships among variables have to be assessed over time while covarying prior aggression (Bond & Bushman, 2017 ; Christakis & Fowler, 2013 ).

Verheijen, Burk, Stoltz, van den Berg, and Cillessen ( 2018 ) tested the idea that players of violent video games have a long‐term impact on their social network. These authors found that participants’ exposure to violent video games increased their friend's aggressive behavior 1 year later. However, given that the authors did not examine whether the violent video game player's increased aggression accounts for the impact on their friend's aggressive behavior, it is unknown whether violent video game play indeed instigates an aggression cycle. For example, players of violent video games may influence their friends so that these friends will also play violent video games. Any increases in aggression could then be an effect of the friends playing violent video games on their own.

1.4. The present research

The present study examines the longitudinal association between the participant's aggression and their friends’ amount of violent video game play, employing an egocentric networking approach (Stark & Krosnick, 2017 ). In egocentric networking analyses, participants provide self‐reports but also report on how they perceive their friends. In the following, and in line with Greitemeyer ( 2018 ), the friends were treated as the players and the participant was treated as their friends’ social network. Please note that ties between the participant's friends (i.e., whether friends also know each other) were not assessed (Greitemeyer, 2018 ; Mötteli & Dohle, 2019 ), because this information was not needed for testing the hypothesis that participants become more aggressive if their friends play violent video games. It was expected that friends’ amount of violent video game play at Time 1 would predict the participant's aggression at Time 2 even when controlling for the impact of the participant's aggression and amount of violent video game play at Time 1. It was further examined whether friends’ aggression at Time 1 would account for the impact of friends’ amount of violent video game play at Time 1 on the participant's aggression at Time 2. Such findings would provide suggestive evidence that violent video game play may instigate an aggression cycle. The study received ethical approval from the Internal Review Board for Ethical Questions by the Scientific Ethical Committee of the University of Innsbruck. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://osf.io/jp8ew/ .

2.1. Participants

Participants were citizens of the U.S. who took part on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Because it was unknown how many of the participants will complete both questionnaires, no power analyses were conducted a priori but a large number of participants was run. At Time 1, there were 2,502 participants (1,376 females, 1,126 males; mean age = 35.7 years, SD = 11.8). Of these, 980 participants (522 females, 458 males; mean age = 38.9 years, SD = 12.5) completed the questionnaire at Time 2. Time 1 and Time 2 were 6 months apart. There were no data exclusions, and all participants were run before any analyses were performed. The questionnaire included some further questions (e.g., participant's perceived deprivation) that are not relevant for the present purpose and are reported elsewhere (Greitemeyer & Sagioglou, 2018 ). 1 Given that the questionnaire was relatively short, no attention checks were employed.

2.2. Procedure and measures

Procedure and measures were very similar to Greitemeyer ( 2018 ), with the main difference that individuals participated at two time points (instead of one). After providing demographics, self‐reported aggressive behavior was assessed. As in previous research (e.g., Krahé & Möller, 2010 ), participants indicated for 10 items how often they had shown the respective behavior in the past 6 months. Sample items are: “I have pushed another person” and “I have spread gossip about people I don't like” (5 items each address physical aggression and relational aggression, respectively). All items were rated on a scale from 1 ( never ) to 5 ( very often ), and scores were averaged. Participants were then asked about their amount of violent video game play, employing one item: “How often do you play violent video games (where the goal is to harm other game characters)?” (1 = never to 7 = very often ).

Afterwards, participants learned that they will be asked questions about people they feel closest to. These may be friends, coworkers, neighbors, relatives. They should answer questions for three contacts with whom they talked about important matters in the last few months. For each friend, they reported the level of aggression (αs between = 0.90 and 0.91) and the amount of violent video game play, employing the same questions as for themselves. Responses to the three friends were then averaged. Finally, participants were thanked and asked what they thought this experiment was trying to study, but none noted the hypothesis that their friend's amount of violent video game play would affect their own level of aggression. At Time 2, the same questions were employed. Reliabilities for how participants perceived the level of aggression for each friend were between 0.89 and 0.90.

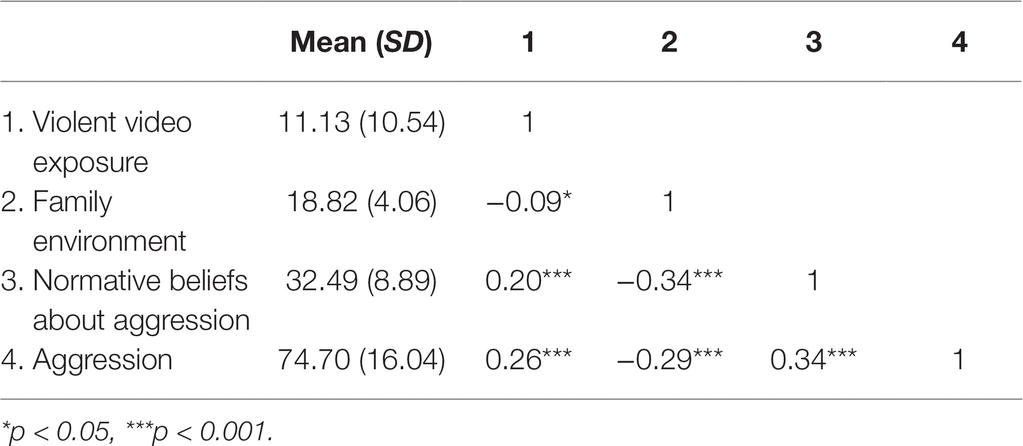

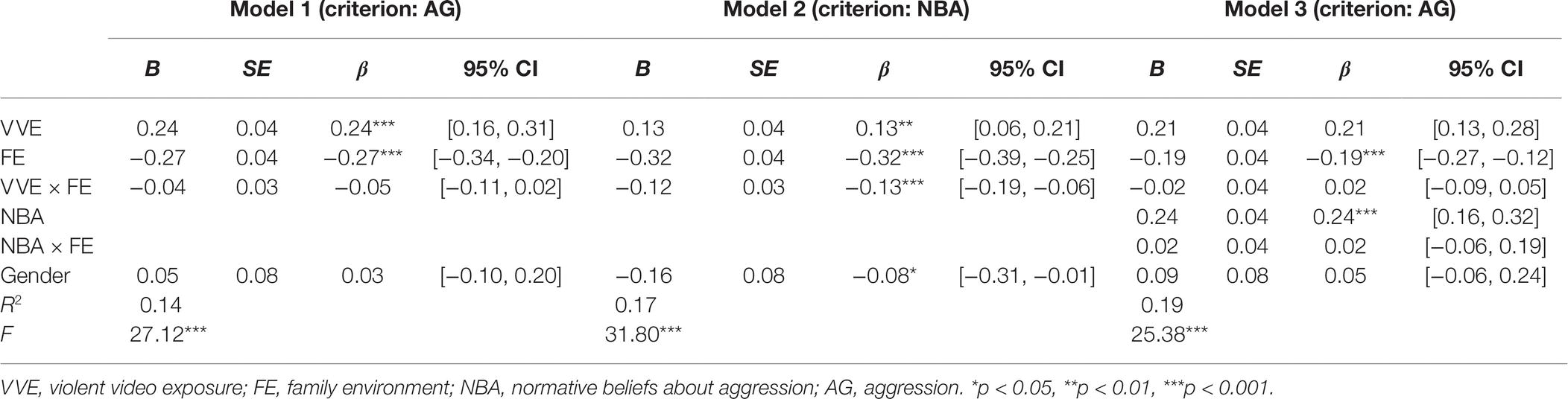

Descriptive statistics, intercorrelations, and internal consistencies of all measures are shown in Table Table1 1 .

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations

Note : For Time 1, N = 2,502; for Time 2, N = 980. All correlation coefficients: p < .001. Where applicable, α reliabilities are presented along the diagonal.

3.1. Time 1 ( N = 2,502)

The relationship between the amount of violent video game play and reported aggression was significant, both for the participant and the friends. That is, violent video game play was associated with increased aggression in the player and participants perceived their friends who play more violent video games to be more aggressive than their less‐playing friends. Participant's and friends’ amount of violent video game play as well as their level of reported aggression, respectively, were also positively associated, indicating that participants perceived their friends to be similar to them. Most importantly, participant's aggression was significantly associated with friends’ amount of violent video game play. 2

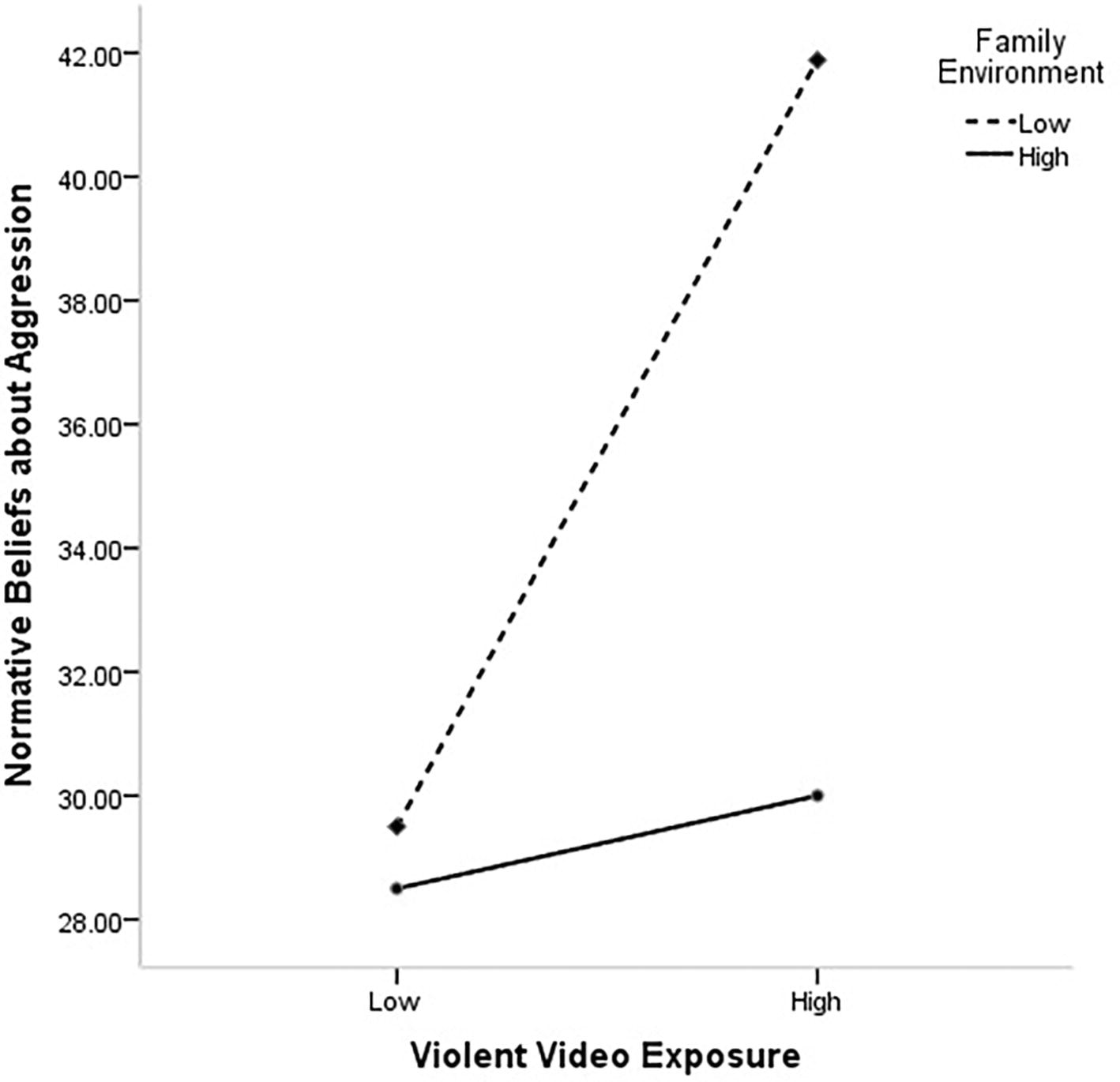

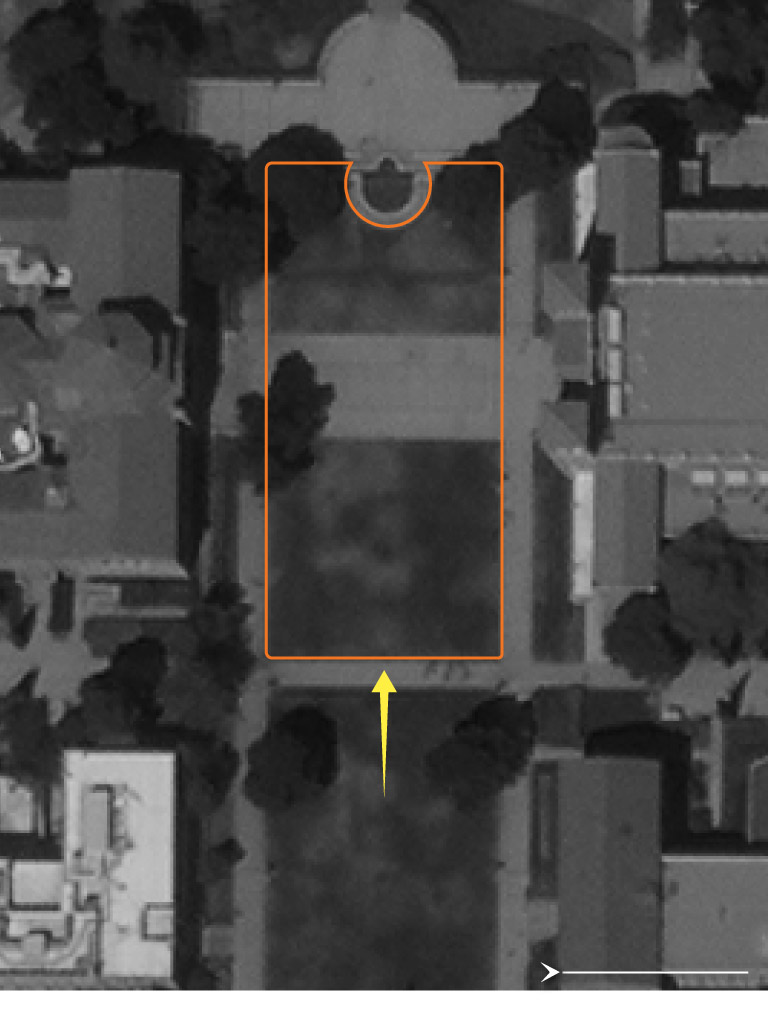

It was then examined whether friends’ amount of violent video game play is still associated with the participant's aggression when controlling for the participant's amount of violent video game play. Participant sex (coded 1 = male, 2 = female) and age were included as covariates. In fact, a bootstrapping analysis showed that the impact of friends’ amount of violent video game play remained significant (point estimate = 0.08, SE = 0.02, t = 4.72, p < .001, 95% confidence interval [CI] = [0.05, 0.11]). Participant's amount of violent video game play (point estimate = 0.03, SE = 0.01, t = 2.18, p = .029, 95% CI = [0.00, 0.05]) and the interaction were also significant (point estimate = −0.01, SE = 0.00, t = 2.41, p = .016, 95% CI = [−0.02, −0.00]). At low levels of the participant's amount of violent video game play (− 1 SD, equals that the participant does not play violent video games in the present data set), friends’ amount of violent video game play was associated with the participant's aggression (point estimate = 0.07, SE = 0.01, t = 5.06, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.10]). At high levels of the participant's amount of violent video game play ( + 1 SD), friends’ amount of violent video game play was also associated with the participant's aggression (point estimate = 0.03, SE = 0.01, t = 3.14, p = .002, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.06]), but the effect was less pronounced. Participants were thus most strongly affected by whether their social network plays violent video games when they do not play violent video games themselves (Figure (Figure1). 1 ). Participant sex was not significantly associated with the participant's aggression (point estimate = −0.04, SE = 0.02, t = 1.95, p = .052, 95% CI = [−0.09, 0.00]), whereas age was (point estimate = −0.01, SE = 0.00, t = 7.84, p < .001, 95% CI = [−0.009, −0.005]).

Simple slopes of the interactive effect of friends’ amount of violent video game play and the participant's amount of violent video game play on the participant's aggression, controlling for participant sex and age (Time 1, N = 2,502)

3.2. Time 1 and Time 2 ( N = 980)

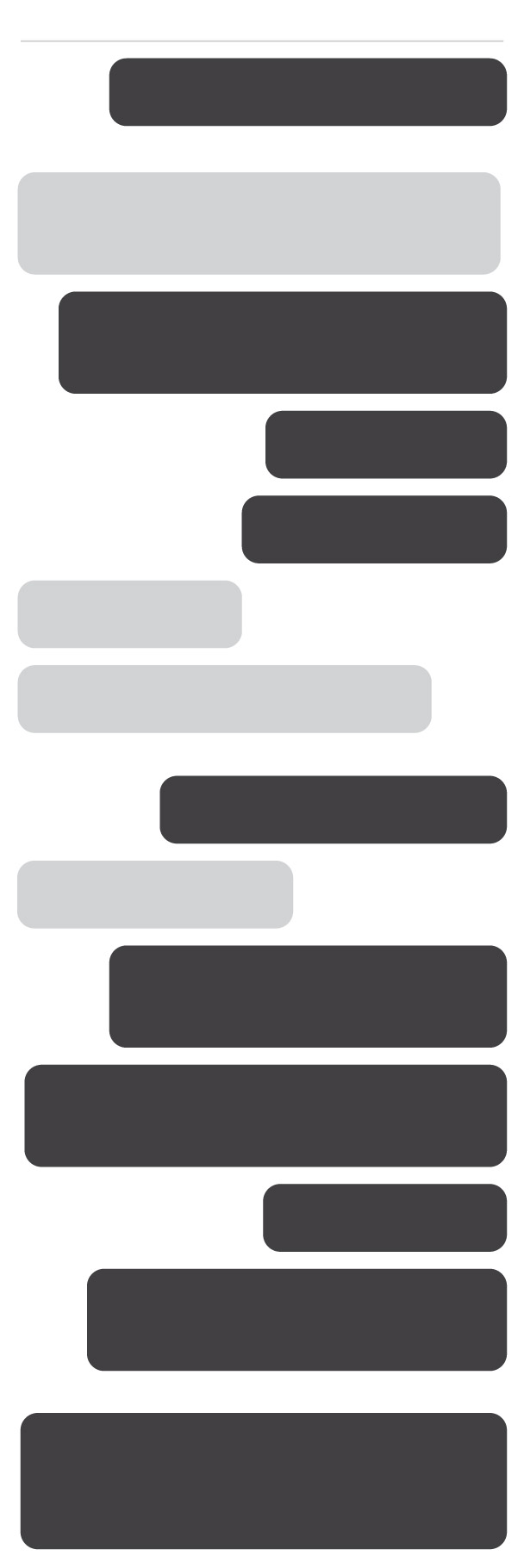

To examine the impact of friends’ amount of violent video game play on the participant's aggression over time, a cross‐lagged regression analysis was performed on the data. Participant's amount of violent video game play, friends’ amount of violent video game play, participant's aggression at Time 1, as well as participant sex and age were used as predictors for participant's aggression at Time 2. The overall regression was significant, F (5,974) = 68.92, R 2 = 0.26, p < .001. Most importantly, friends’ amount of violent video game play at Time 1 significantly predicted participant's aggression at Time 2, t = 2.60, β = .09, 95% CI = (0.02, 0.16), p = .009. Participant's aggression showed high stability, t = 16.77, β = .48, 95% CI = (0.42, 0.53), p < .001, whereas the participant's amount of violent video game play at Time 1 did not significantly predict the participant's aggression at Time 2, t = 1.77, β = −.07, 95% CI = (− 0.14, 0.01), p = .077 (Figure (Figure2 2 ). 3 , 4 Participant sex also received a significant regression weight, t = 2.08, β = −.06, 95% CI = (−0.12, −0.00), p = .038, whereas age did not, t = 1.93, β = −.06, 95% CI = (−0.12, 0.00), p = .054. The reverse effect that the participant's aggression at Time 1 predicts their friends’ amount of violent video game play at Time 2 when controlling for the participant's amount of violent video game play and friends’ amount of violent video game play at Time 1, as well as participant sex and age, was not significant, t = 0.67, β = .02, 95% CI = (−0.03, 0.06), p = .504.

Participant's aggression at Time 2 simultaneously predicted by friends’ amount of violent video game play, participant's aggression, and participant's amount of violent video game play at Time 1. Participant sex and age were controlled for, but were not included in the figure (see the main text for the impact of participant sex and age). * p < .01, ** p < .001 ( N = 980)

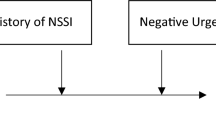

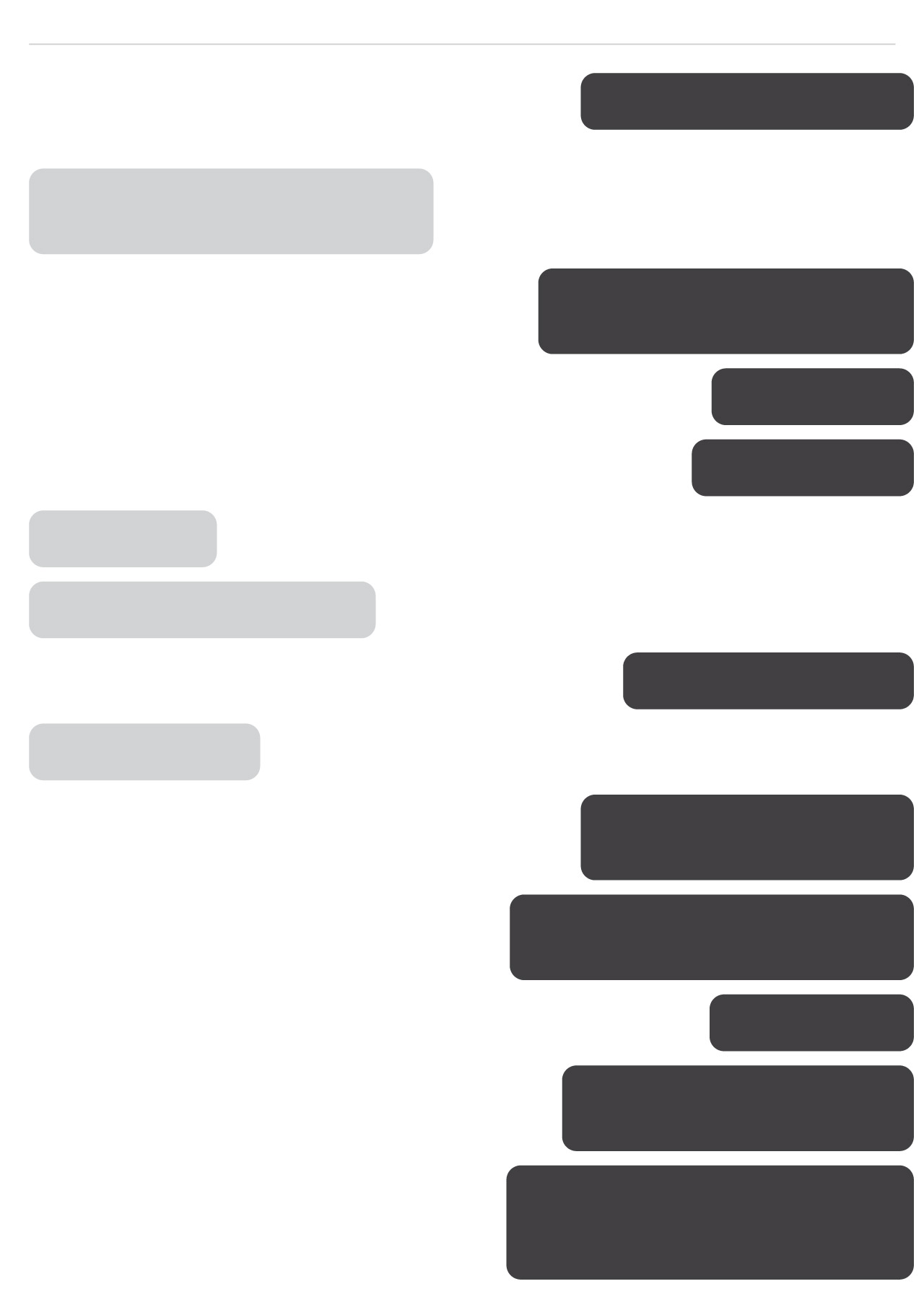

Finally, it was examined whether the impact of friends’ amount of violent video game play at Time 1 on the participant's aggression at Time 2 would be mediated by friends’ level of aggression at Time 1 (while controlling for the participant's aggression and amount of violent video game play at Time 1 as well as participant sex and age). A bootstrapping analysis (with 5.000 iterations) showed that the impact of friends’ level of aggression at Time 1 on the participant's aggression at Time 2 was significant (point estimate = 0.16, SE = 0.04, t = 4.28, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.09, 0.23]). Participant's aggression at Time 1 was also a significant predictor (point estimate = 0.34, SE = 0.03, t = 10.19, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.27, 0.40]). Friends’ amount of violent video game play at Time 1 (point estimate = 0.03, SE = 0.01, t = 1.82, p = .069, 95% CI = [−0.00, 0.05]) and participant's amount of violent video game play at Time 1 (point estimate = −0.01, SE = 0.01, t = 1.65, p = .099, 95% CI = [−0.03, 0.00]) were not significant predictors. Participant sex significantly predicted the participant's aggression at Time 2 (point estimate = −0.06, SE = 0.03, t = 2.31, p = .021, 95% CI = [−0.11, −0.01]), whereas age did not (point estimate = −0.00, SE = 0.00, t = 1.90, p = .058, 95% CI = [−0.00, 0.00]). The indirect effect was significantly different from zero (point estimate = 0.01, 95% CI = [.00, 0.02]), suggesting that participants are more aggressive if their friends play violent video games for the reason that these friends are more aggressive. Figure Figure3 3 displays a simplified version of this mediation effect, based on regression coefficients and without controlling for the participant's aggression at Time 1, the participant's amount of violent video game play at Time 1, participant sex, and age.

Mediation of the impact of friends’ violent video game exposure (VVE) at Time 1 on the participant's aggression at Time 2 by friends’ aggression at Time 1. All paths are significant. β * = the coefficient from friends’ VVE at Time 1 to the participant's aggression at Time 2 when controlling for friends’ aggression at Time 1 ( N = 980)

4. DISCUSSION

Violent video games have an impact on the player's aggression (Anderson et al., 2010 ; Greitemeyer & Mügge, 2014 ), but—as the present study shows—they also increase aggression in the player's social network. In particular, participants who do not play violent video games reported to be more aggressive the more their friends play violent video games. Mediation analyses showed that the increased aggression in the friends accounted for the relationship between friends’ amount of violent video game play and the participant's aggression. Because changes in aggression over time were assessed, the present study provides evidence for the hypothesized effect that violent video game play is associated with increased aggression in the player, which then instigates aggression in their social network. Importantly, the impact of the participant's amount of violent video game play was controlled for, indicating that the relationship between friends’ amount of violent video game play and the participant's aggression is not due to the friends being similar to the participants. Moreover, the reverse effect that aggressive people will become attracted to others who play violent video games was not reliable. The present research thus documents the directional effects that violent video games is associated with increased aggression in the player and that this increased aggression then has an impact on people with whom the player is connected.

Overall, the present study provides comprehensive support for key hypotheses derived from the GAM and its extension (Anderson & Bushman, 2018 ). It shows that violent video game play is associated with increased aggression in the player and it documents that others who are connected to players might be also affected even when controlling for their own amount of violent video game play. To the best of my knowledge, this study is the first that shows that because violent video game players are more aggressive their friends will become aggressive, too. Previous research either employed a cross‐sectional design and thus could not address the direction of the effect (Greitemeyer, 2018 ) or did not examine whether the effect of violent video game play (i.e., increased aggression) indeed spreads (Verheijen et al., 2018 ). As proposed by the GAM and its extension (Anderson & Bushman, 2018 ), increased aggression in violent video game players appears to instigate an aggression escalation cycle (cf. Anderson et al., 2008 ).

It is noteworthy, however, that the longitudinal effect of the participant's amount of violent video game play at Time 1 on the participant's aggression at Time 2 was not reliable. Hence, although there were significant correlations between participants’ aggression and their violent video game use at both time points, the present study does not show that repeatedly playing violent video games leads to long‐term changes in aggression. However, a recent meta‐analysis of the long‐term effects of playing violent video games confirmed that violent video game play does increase physical aggression over time (Prescott, Sargent, & Hull, 2018 ), although the effect size was relatively small ( β = 0.11) and thus single studies that produce nonsignificant results are to be expected. Importantly, in the present study, a single‐item measure of violent video game play was employed. In contrast, previous research on the relationship between violent video game play and the player's aggression has often employed multi‐item measurement scales that are typically more reliable and precise (for an overview, Busching et al., 2015 ). Hence, it may well be that due to the limitations of the single‐item measure of the participant's amount of violent video game play the relationship between participants’ violent game play and their aggressive behavior was artificially reduced.

Even though the longitudinal design allows ruling out a host of alternative explanations for the impact of violent video games on the player's social network, causality can only inferred by using an experimental design. Future research may thus randomly assign participants to play a violent or nonviolent video game (players) and assesses their aggression against new participants (partners). It can be expected that the partners suffer more aggression when the player had played a violent, compared to a nonviolent, video game. Afterwards, it could be tested whether the partner of a violent video game player is more aggressive than a partner of a nonviolent video game player. Given that the partner is not exposed to any video games, firm causal conclusions could be drawn that violent video game play affects aggression in people who are connected to violent video game players. It could be also tested whether the partner of a violent video game player would not only be more likely to retaliate against the player, but also against a third party. In fact, previous research into displaced aggression has shown that people may react aggressively against a target that is innocent of any wrongdoing after they have been provoked by another person (Marcus‐Newhall, Pedersen, Carlson, & Miller, 2000 ). It may thus well be that the effect of playing violent video games spreads in social networks and that even people who are only indirectly linked to violent video game players are affected.

An important limitation of the present egocentric network data is the reliance on the participant's perception of their social network, leaving the possibility that participants did not accurately perceive their friends. It is noteworthy that participants perceived their friends to be highly similar to them. In this regard, it is important to keep in mind that participants always provided self‐ratings first, followed by perceptions of their friends. It is thus conceivable that participants used their self‐ratings as anchors for the perceptions of their friends. Such a tendency, however, would reduce the unique effect of friends’ amount of violent video game play on the participant's aggression when controlling for the participant's amount of violent video game play. The finding that participants in particular who do not play violent video games reported to be more aggressive if their friends play violent video games also suggests that the impact of violent video games on the player's social network is not due to participants providing both self‐reports and how they perceive their friends. Finally, rather than by their friends’ objective qualities, people's behavior should be more likely to be affected by their subjective perceptions of their friends.

As noted in the introduction, participants may not be aware of the extent to which their friends play violent video games and hence used the perception of how aggressive their friends are as an anchor for estimating their friends’ amount of violent video game play. Importantly, however, the participant's aggression at Time 2 was significantly predicted by friends’ amount of violent video game play at Time 1 even when controlling for friends’ level of aggression at Time 1 (see Figure Figure3). 3 ). Moreover, whereas aggression might be used for estimating violent video game exposure of the friends, participants should be well aware of the extent to which they play violent video games so that anchoring effects for participant's self‐reports are unlikely. However, given that it cannot be completely ruled out that the correlation between violent game play of friends at Time 1 and aggressive behavior of participants at Time 2 reflects a pseudocorrelation that is determined by the correlation between aggressive behavior of friends at Time 1 and aggressive behavior of the participant at Time 2, future research that employs sociocentric network analyses where information about the friends is provided by the friends themselves would be informative.

Another limitation is the employment of self‐report measures to assess aggressive behavior. Self‐report measures are quite transparent, so participants may have rated themselves more favorably than is actually warranted. In fact, mean scores of reported aggressive behavior were quite low. This reduced variance, however, typically diminishes associations with other constructs. In any case, observing how actual aggressive behavior is influenced by the social network's violent video game play would be an important endeavor for future work. It also has to be acknowledged that some participants may have reported on different friends at Time 1 and Time 2. Future research would be welcome that ensures that participants consider the same friends at different time points.

Future research may also shed some further light on the psychological processes. In the present study, the violent video game players’ higher levels of aggression accounted for the relationship between their amount of violent video game play and the participants’ reported aggression. It would be interesting to examine why the players’ aggression influences the aggression level of their social network. One possibility is that witnessing increased aggression by others (who play violent video games) leads to greater acceptance of norms condoning aggression, which are known to be an antecedent of aggressive behavior (Huesmann & Guerra, 1997 ). After all, if others behave aggressively, why should one refrain from engaging in the same behavior.

Another limitation of the present work is that it was not assessed how participants and their friends play violent video games. A recent survey (Lenhart, Smith, Anderson, Duggan, & Perrin, 2015 ) showed that many video game users play video games together with their friends, either cooperatively or competitively. This is insofar noteworthy as there might be some overlap between participants’ and their friends’ violent video game play. Moreover, cooperative video games have been shown to increase prosocial tendencies (Greitemeyer, 2013 ; Greitemeyer & Cox, 2013 ; but see Verheijen, Stoltz, van den Berg, & Cillessen, 2019 ) and decrease aggression (Velez, Greitemeyer, Whitaker, Ewoldsen, & Bushman, 2016 ). In contrast, competitive video game play increases aggressive affect and behavior (e.g., Adachi & Willoughby, 2016 ). Hence, future research should examine more closely whether participants play violent video games on their own, competitively, or cooperatively. The latter may show some positive effects of video game play, both on the player and the player's friends, whereas opposing effects should be found for competitive video games.

To obtain high statistical power and thus to increase the probability to detect significant effects, data were collected via an online survey. The current sample was drawn from the MTurk population (for a review of the trend to rely on MTurk samples in social and personality psychology, see Anderson et al., 2019 ). Samples drawn from MTurk are not demographically representative of the U.S. population as a whole. For example, MTurk samples are disproportionally young and female and they are better educated but tend to be unemployed (for a review, Keith, Tay, & Harms, 2017 ). On the other hand, MTurk samples are more representative of the U.S. population than are college student samples (Paolacci & Chandler, 2014 ) and the pool of participants is geographically diverse. Moreover, MTurk participants appear to be more attentive to survey instructions than are undergraduate students (Hauser & Schwarz, 2016 ). Nevertheless, future research on the impact of violent video game play on the player's social network that employs other samples would improve the generalizability of the present findings.

In conclusion, violent video game play is not only associated with increased aggression in the player but also in the player's social network. In fact, increased aggression due to violent video game play appears to instigate further aggression in the player's social network. This study thus provides suggestive evidence that not only players of violent video games are more aggressive, but also individuals become more aggressive who do not play violent video games themselves but are connected to others who do play.

Greitemeyer T. The contagious impact of playing violent video games on aggression: Longitudinal evidence . Aggressive Behavior . 2019; 45 :635–642. 10.1002/ab.21857 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

1 Participant's perceived deprivation was positively related to both violent video game exposure, r (2,502) = 0.08, p < .001, and reported aggression, r (2,502) = 0.14, p < .001. However, the relationship between violent video game exposure and reported aggression, r (2,502) = 0.15, p < .001, was relatively unaffected when controlling for perceived deprivation, r (2,499) = 0.14, p < .001.

2 Given that the measures of violent video game exposure and aggressive behavior violated the normal distribution, Spearman's ρ coefficients were also calculated. However, the pattern of finding was very similar (e.g., the crucial relationship between the participant's aggression and friends’ amount of violent video game play was 0.18 [Pearson] and 0.17 [Spearman]). All these analyses can be obtained from the author upon request.

3 When dropping friends’ amount of violent video game play from the analysis, the participant's amount of violent video game play at Time 1 still did not predict participant's aggression at Time 2, t = 0.44, β = −.01, 95% CI = (− 0.02, 0.01), p = .657 (when controlling for participant's aggression at Time 1, participant sex, and age).

4 Given that violent video games primarily model physical aggression, violent video games should have a stronger effect on the player's physical aggression than on other types of aggression. In fact, the impact of the participant's amount of violent video game play at Time 1 on the participant's physical aggression at Time 2, t = 1.49, β = .04, 95% CI = (− 0.00, 0.02), p = .136 (when controlling for the participant's physical aggression at Time 1), was more pronounced than the impact on the participant's relational aggression at Time 2, t = 0.52, β = .02, 95% CI = (− 0.01, 0.02), p = .603 (when controlling for the participant's relational aggression at Time 1), but both effects were not significant.

- Adachi, P. J. C. , & Willoughby, T. (2016). The longitudinal association between competitive video game play and aggression among adolescents and young adults . Child Development , 87 , 1877–1892. 10.1111/cdev.12556 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, C. A. , Allen, J. J. , Plante, C. , Quigley‐McBride, A. , Lovett, A. , & Rokkum, J. N. (2019). The MTurkification of social and personality psychology . Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 45 , 842–850. 10.1177%2F0146167218798821 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, C. A. , Buckley, K. E. , & Carnagey, N. L. (2008). Creating your own hostile environment: A laboratory examination of trait aggressiveness and the violence escalation cycle . Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 34 , 462–473. 10.1177/0146167207311282 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, C. A. , & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human aggression . Annual Review of Psychology , 53 , 27–51. 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, C. A. , & Bushman, B. J. (2018). Media violence and the General Aggression Model . Journal of Social Issues , 74 , 386–413. 10.1111/josi.12275 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, C. A. , & Carnagey, N. L. (2009). Causal effects of violent sports video games on aggression: Is it competitiveness or violent content? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , 45 , 731–739. 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.04.019 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, C. A. , Sakamoto, A. , Gentile, D. A. , Ihori, N. , Shibuya, A. , Yukawa, S. , … Kobayashi, K. (2008). Longitudinal effects of violent video games on aggression in Japan and the United States . Pediatrics , 122 , e1067–e1072. 10.1542/peds.2008-1425 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, C. A. , Shibuya, A. , Ihori, N. , Swing, E. L. , Bushman, B. J. , Sakamoto, A. , … Saleem, M. (2010). Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in Eastern and Western countries . Psychological Bulletin , 136 , 151–173. 10.1037/a0018251 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bond, R. M. , & Bushman, B. J. (2017). The contagious spread of violence among US adolescents through social networks . American Journal of Public Health , 107 , 288–294. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303550 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Busching, R. , Gentile, D. A. , Krahé, B. , Möller, I. , Khoo, A. , Walsh, D. A. , & Anderson, C. A. (2015). Testing the reliability and validity of different measures of violent video game use in the United States, Singapore, and Germany . Psychology of Popular Media Culture , 4 , 97–111. [ Google Scholar ]

- Christakis, N. A. , & Fowler, J. H. (2013). Social contagion theory: Examining dynamic social networks and human behavior . Statistics in Medicine , 32 , 556–577. 10.1002/sim.5408 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dishion, T. J. , & Tipsord, J. M. (2011). Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development . Annual Review of Psychology , 62 , 189–214. 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100412 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gabbiadini, A. , & Riva, P. (2018). The lone gamer: Social exclusion predicts violent video game preferences and fuels aggressive inclinations in adolescent players . Aggressive Behavior , 44 , 113–124. 10.1002/ab.21735 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gentile, D. A. , Lynch, P. J. , Linder, J. R. , & Walsh, D. A. (2004). The effects of violent video game habits on adolescent hostility, aggressive behaviors, and school performance . Journal of Adolescence , 27 , 5–22. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.10.002 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldstein, J. H. , Davis, R. W. , & Herman, D. (1975). Escalation of aggression: Experimental studies . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 31 , 162–170. 10.1037/h0076241 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greitemeyer, T. (2013). Playing video games cooperatively increases empathic concern . Social Psychology , 44 , 408–413. 10.1027/1864-9335/a000154 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greitemeyer, T. (2018). The spreading impact of playing violent video games on aggression . Computers in Human Behavior , 80 , 216–219. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.11.022 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greitemeyer, T. , & Cox, C. (2013). There's no “I” in team: Effects of cooperative video games on cooperative behavior: Video games and cooperation . European Journal of Social Psychology , 43 , 224–228. 10.1002/ejsp.1940 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greitemeyer, T. , & Mügge, D. O. (2014). Video games do affect social outcomes: A meta‐analytic review of the effects of violent and prosocial video game play . Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 40 , 578–589. 10.1177/0146167213520459 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greitemeyer, T. , & Sagioglou, C. (2018). The impact of personal relative deprivation on aggression over time . The Journal of Social Psychology , 3–7. 10.1080/00224545.2018.1549013 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hauser, D. J. , & Schwarz, N. (2016). Attentive Turkers: MTurk participants perform better on online attention checks than do subject pool participants . Behavior Research Methods , 48 , 400–407. 10.3758/s13428-015-0578-z [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huesmann, L. R. (2012). The contagion of violence: The extent, the processes, and the outcomes. Social and economic costs of violence: Workshop summary (pp. 63–69). Washington, DC: IOM (Institute of Medicine) and NRC (National, Research Council). [ Google Scholar ]

- Huesmann, L. R. , & Guerra, N. G. (1997). Children's normative beliefs about aggression and aggressive behavior . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 72 , 408–419. 10.1037/0022-3514.72.2.408 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jung, J. , Busching, R. , & Krahé, B. (2019). Catching aggression from one's peers: A longitudinal and multilevel analysis . Social and Personality Psychology Compass , 13 , e12433 10.1111/spc3.12433 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keith, M. G. , Tay, L. , & Harms, P. D. (2017). Systems perspective of Amazon Mechanical Turk for organizational research: Review and recommendations . Frontiers in Psychology , 8 , 1359 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01359 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krahé, B. , & Möller, I. (2004). Playing violent electronic games, hostile attributional style, and aggression‐related norms in German adolescents . Journal of Adolescence , 27 , 53–69. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.10.006 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krahé, B. , & Möller, I. (2010). Longitudinal effects of media violence on aggression and empathy among German adolescents . Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology , 31 , 401–409. 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.07.003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lenhart, A. , Smith, A. , Anderson, M. , Duggan, M. , & Perrin, A. (2015). Teens, technology and friendships Pew Internet and American Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/08/06/teens-technology-and-friendships/

- Marcus‐Newhall, A. , Pedersen, W. C. , Carlson, M. , & Miller, N. (2000). Displaced aggression is alive and well: A meta‐analytic review . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 78 , 670–689. 10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.670 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McCarthy, R. J. , Coley, S. L. , Wagner, M. F. , Zengel, B. , & Basham, A. (2016). Does playing video games with violent content temporarily increase aggressive inclinations? A pre‐registered experimental study . Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , 67 , 13–19. 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.10.009 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mötteli, S. , & Dohle, S. (2019). Egocentric social network correlates of physical activity . Journal of Sport and Health Science , 2–8. 10.1016/j.jshs.2017.01.002 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paolacci, G. , & Chandler, J. (2014). Inside the Turk: Understanding Mechanical Turk as a participant pool . Current Directions in Psychological Science , 23 , 184–188. 10.1177/0963721414531598 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Prescott, A. T. , Sargent, J. D. , & Hull, J. G. (2018). Metaanalysis of the relationship between violent video game play and physical aggression over time . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 115 , 9882–9888. 10.1073/pnas.1611617114 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stark, T. H. , & Krosnick, J. A. (2017). GENSI: A new graphical tool to collect ego‐centered network data . Social Networks , 48 , 36–45. 10.1016/j.socnet.2016.07.007 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Velez, J. A. , Greitemeyer, T. , Whitaker, J. L. , Ewoldsen, D. R. , & Bushman, B. J. (2016). Violent video games and reciprocity: The attenuating effects of cooperative game play on subsequent aggression . Communication Research , 43 , 447–467. 10.1177/0093650214552519 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Verheijen, G. P. , Burk, W. J. , Stoltz, S. E. M. J. , van den Berg, Y. H. M. , & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2018). Friendly fire: Longitudinal effects of exposure to violent video games on aggressive behavior in adolescent friendship dyads . Aggressive Behavior , 44 , 257–267. 10.1002/ab.21748 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Verheijen, G. P. , Stoltz, S. E. M. J. , van den Berg, Y. H. M. , & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2019). The influence of competitive and cooperative video games on behavior during play and friendship quality in adolescence . Computers in Human Behavior , 91 , 297–304. 10.1016/j.chb.2018.10.023 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Widom, C. S. (1989). Does violence beget violence? A critical examination of the literature . Psychological Bulletin , 106 , 3–28. 10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.287 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 March 2018

Does playing violent video games cause aggression? A longitudinal intervention study

- Simone Kühn 1 , 2 ,

- Dimitrij Tycho Kugler 2 ,

- Katharina Schmalen 1 ,

- Markus Weichenberger 1 ,

- Charlotte Witt 1 &

- Jürgen Gallinat 2

Molecular Psychiatry volume 24 , pages 1220–1234 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

551k Accesses

103 Citations

2343 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neuroscience

It is a widespread concern that violent video games promote aggression, reduce pro-social behaviour, increase impulsivity and interfere with cognition as well as mood in its players. Previous experimental studies have focussed on short-term effects of violent video gameplay on aggression, yet there are reasons to believe that these effects are mostly the result of priming. In contrast, the present study is the first to investigate the effects of long-term violent video gameplay using a large battery of tests spanning questionnaires, behavioural measures of aggression, sexist attitudes, empathy and interpersonal competencies, impulsivity-related constructs (such as sensation seeking, boredom proneness, risk taking, delay discounting), mental health (depressivity, anxiety) as well as executive control functions, before and after 2 months of gameplay. Our participants played the violent video game Grand Theft Auto V, the non-violent video game The Sims 3 or no game at all for 2 months on a daily basis. No significant changes were observed, neither when comparing the group playing a violent video game to a group playing a non-violent game, nor to a passive control group. Also, no effects were observed between baseline and posttest directly after the intervention, nor between baseline and a follow-up assessment 2 months after the intervention period had ended. The present results thus provide strong evidence against the frequently debated negative effects of playing violent video games in adults and will therefore help to communicate a more realistic scientific perspective on the effects of violent video gaming.

Similar content being viewed by others

No effect of short term exposure to gambling like reward systems on post game risk taking

Increasing prosocial behavior and decreasing selfishness in the lab and everyday life

Dynamics of the immediate behavioral response to partial social exclusion

The concern that violent video games may promote aggression or reduce empathy in its players is pervasive and given the popularity of these games their psychological impact is an urgent issue for society at large. Contrary to the custom, this topic has also been passionately debated in the scientific literature. One research camp has strongly argued that violent video games increase aggression in its players [ 1 , 2 ], whereas the other camp [ 3 , 4 ] repeatedly concluded that the effects are minimal at best, if not absent. Importantly, it appears that these fundamental inconsistencies cannot be attributed to differences in research methodology since even meta-analyses, with the goal to integrate the results of all prior studies on the topic of aggression caused by video games led to disparate conclusions [ 2 , 3 ]. These meta-analyses had a strong focus on children, and one of them [ 2 ] reported a marginal age effect suggesting that children might be even more susceptible to violent video game effects.

To unravel this topic of research, we designed a randomised controlled trial on adults to draw causal conclusions on the influence of video games on aggression. At present, almost all experimental studies targeting the effects of violent video games on aggression and/or empathy focussed on the effects of short-term video gameplay. In these studies the duration for which participants were instructed to play the games ranged from 4 min to maximally 2 h (mean = 22 min, median = 15 min, when considering all experimental studies reviewed in two of the recent major meta-analyses in the field [ 3 , 5 ]) and most frequently the effects of video gaming have been tested directly after gameplay.

It has been suggested that the effects of studies focussing on consequences of short-term video gameplay (mostly conducted on college student populations) are mainly the result of priming effects, meaning that exposure to violent content increases the accessibility of aggressive thoughts and affect when participants are in the immediate situation [ 6 ]. However, above and beyond this the General Aggression Model (GAM, [ 7 ]) assumes that repeatedly primed thoughts and feelings influence the perception of ongoing events and therewith elicits aggressive behaviour as a long-term effect. We think that priming effects are interesting and worthwhile exploring, but in contrast to the notion of the GAM our reading of the literature is that priming effects are short-lived (suggested to only last for <5 min and may potentially reverse after that time [ 8 ]). Priming effects should therefore only play a role in very close temporal proximity to gameplay. Moreover, there are a multitude of studies on college students that have failed to replicate priming effects [ 9 , 10 , 11 ] and associated predictions of the so-called GAM such as a desensitisation against violent content [ 12 , 13 , 14 ] in adolescents and college students or a decrease of empathy [ 15 ] and pro-social behaviour [ 16 , 17 ] as a result of playing violent video games.

However, in our view the question that society is actually interested in is not: “Are people more aggressive after having played violent video games for a few minutes? And are these people more aggressive minutes after gameplay ended?”, but rather “What are the effects of frequent, habitual violent video game playing? And for how long do these effects persist (not in the range of minutes but rather weeks and months)?” For this reason studies are needed in which participants are trained over longer periods of time, tested after a longer delay after acute playing and tested with broader batteries assessing aggression but also other relevant domains such as empathy as well as mood and cognition. Moreover, long-term follow-up assessments are needed to demonstrate long-term effects of frequent violent video gameplay. To fill this gap, we set out to expose adult participants to two different types of video games for a period of 2 months and investigate changes in measures of various constructs of interest at least one day after the last gaming session and test them once more 2 months after the end of the gameplay intervention. In contrast to the GAM, we hypothesised no increases of aggression or decreases in pro-social behaviour even after long-term exposure to a violent video game due to our reasoning that priming effects of violent video games are short-lived and should therefore not influence measures of aggression if they are not measured directly after acute gaming. In the present study, we assessed potential changes in the following domains: behavioural as well as questionnaire measures of aggression, empathy and interpersonal competencies, impulsivity-related constructs (such as sensation seeking, boredom proneness, risk taking, delay discounting), and depressivity and anxiety as well as executive control functions. As the effects on aggression and pro-social behaviour were the core targets of the present study, we implemented multiple tests for these domains. This broad range of domains with its wide coverage and the longitudinal nature of the study design enabled us to draw more general conclusions regarding the causal effects of violent video games.

Materials and methods

Participants.

Ninety healthy participants (mean age = 28 years, SD = 7.3, range: 18–45, 48 females) were recruited by means of flyers and internet advertisements. The sample consisted of college students as well as of participants from the general community. The advertisement mentioned that we were recruiting for a longitudinal study on video gaming, but did not mention that we would offer an intervention or that we were expecting training effects. Participants were randomly assigned to the three groups ruling out self-selection effects. The sample size was based on estimates from a previous study with a similar design [ 18 ]. After complete description of the study, the participants’ informed written consent was obtained. The local ethics committee of the Charité University Clinic, Germany, approved of the study. We included participants that reported little, preferably no video game usage in the past 6 months (none of the participants ever played the game Grand Theft Auto V (GTA) or Sims 3 in any of its versions before). We excluded participants with psychological or neurological problems. The participants received financial compensation for the testing sessions (200 Euros) and performance-dependent additional payment for two behavioural tasks detailed below, but received no money for the training itself.

Training procedure

The violent video game group (5 participants dropped out between pre- and posttest, resulting in a group of n = 25, mean age = 26.6 years, SD = 6.0, 14 females) played the game Grand Theft Auto V on a Playstation 3 console over a period of 8 weeks. The active control group played the non-violent video game Sims 3 on the same console (6 participants dropped out, resulting in a group of n = 24, mean age = 25.8 years, SD = 6.8, 12 females). The passive control group (2 participants dropped out, resulting in a group of n = 28, mean age = 30.9 years, SD = 8.4, 12 females) was not given a gaming console and had no task but underwent the same testing procedure as the two other groups. The passive control group was not aware of the fact that they were part of a control group to prevent self-training attempts. The experimenters testing the participants were blind to group membership, but we were unable to prevent participants from talking about the game during testing, which in some cases lead to an unblinding of experimental condition. Both training groups were instructed to play the game for at least 30 min a day. Participants were only reimbursed for the sessions in which they came to the lab. Our previous research suggests that the perceived fun in gaming was positively associated with training outcome [ 18 ] and we speculated that enforcing training sessions through payment would impair motivation and thus diminish the potential effect of the intervention. Participants underwent a testing session before (baseline) and after the training period of 2 months (posttest 1) as well as a follow-up testing sessions 2 months after the training period (posttest 2).

Grand Theft Auto V (GTA)

GTA is an action-adventure video game situated in a fictional highly violent game world in which players are rewarded for their use of violence as a means to advance in the game. The single-player story follows three criminals and their efforts to commit heists while under pressure from a government agency. The gameplay focuses on an open world (sandbox game) where the player can choose between different behaviours. The game also allows the player to engage in various side activities, such as action-adventure, driving, third-person shooting, occasional role-playing, stealth and racing elements. The open world design lets players freely roam around the fictional world so that gamers could in principle decide not to commit violent acts.

The Sims 3 (Sims)

Sims is a life simulation game and also classified as a sandbox game because it lacks clearly defined goals. The player creates virtual individuals called “Sims”, and customises their appearance, their personalities and places them in a home, directs their moods, satisfies their desires and accompanies them in their daily activities and by becoming part of a social network. It offers opportunities, which the player may choose to pursue or to refuse, similar as GTA but is generally considered as a pro-social and clearly non-violent game.

Assessment battery

To assess aggression and associated constructs we used the following questionnaires: Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire [ 19 ], State Hostility Scale [ 20 ], Updated Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale [ 21 , 22 ], Moral Disengagement Scale [ 23 , 24 ], the Rosenzweig Picture Frustration Test [ 25 , 26 ] and a so-called World View Measure [ 27 ]. All of these measures have previously been used in research investigating the effects of violent video gameplay, however, the first two most prominently. Additionally, behavioural measures of aggression were used: a Word Completion Task, a Lexical Decision Task [ 28 ] and the Delay frustration task [ 29 ] (an inter-correlation matrix is depicted in Supplementary Figure 1 1). From these behavioural measures, the first two were previously used in research on the effects of violent video gameplay. To assess variables that have been related to the construct of impulsivity, we used the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale [ 30 ] and the Boredom Propensity Scale [ 31 ] as well as tasks assessing risk taking and delay discounting behaviourally, namely the Balloon Analogue Risk Task [ 32 ] and a Delay-Discounting Task [ 33 ]. To quantify pro-social behaviour, we employed: Interpersonal Reactivity Index [ 34 ] (frequently used in research on the effects of violent video gameplay), Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale [ 35 ], Reading the Mind in the Eyes test [ 36 ], Interpersonal Competence Questionnaire [ 37 ] and Richardson Conflict Response Questionnaire [ 38 ]. To assess depressivity and anxiety, which has previously been associated with intense video game playing [ 39 ], we used Beck Depression Inventory [ 40 ] and State Trait Anxiety Inventory [ 41 ]. To characterise executive control function, we used a Stop Signal Task [ 42 ], a Multi-Source Interference Task [ 43 ] and a Task Switching Task [ 44 ] which have all been previously used to assess effects of video gameplay. More details on all instruments used can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Data analysis

On the basis of the research question whether violent video game playing enhances aggression and reduces empathy, the focus of the present analysis was on time by group interactions. We conducted these interaction analyses separately, comparing the violent video game group against the active control group (GTA vs. Sims) and separately against the passive control group (GTA vs. Controls) that did not receive any intervention and separately for the potential changes during the intervention period (baseline vs. posttest 1) and to test for potential long-term changes (baseline vs. posttest 2). We employed classical frequentist statistics running a repeated-measures ANOVA controlling for the covariates sex and age.

Since we collected 52 separate outcome variables and conduced four different tests with each (GTA vs. Sims, GTA vs. Controls, crossed with baseline vs. posttest 1, baseline vs. posttest 2), we had to conduct 52 × 4 = 208 frequentist statistical tests. Setting the alpha value to 0.05 means that by pure chance about 10.4 analyses should become significant. To account for this multiple testing problem and the associated alpha inflation, we conducted a Bonferroni correction. According to Bonferroni, the critical value for the entire set of n tests is set to an alpha value of 0.05 by taking alpha/ n = 0.00024.

Since the Bonferroni correction has sometimes been criticised as overly conservative, we conducted false discovery rate (FDR) correction [ 45 ]. FDR correction also determines adjusted p -values for each test, however, it controls only for the number of false discoveries in those tests that result in a discovery (namely a significant result).

Moreover, we tested for group differences at the baseline assessment using independent t -tests, since those may hamper the interpretation of significant interactions between group and time that we were primarily interested in.

Since the frequentist framework does not enable to evaluate whether the observed null effect of the hypothesised interaction is indicative of the absence of a relation between violent video gaming and our dependent variables, the amount of evidence in favour of the null hypothesis has been tested using a Bayesian framework. Within the Bayesian framework both the evidence in favour of the null and the alternative hypothesis are directly computed based on the observed data, giving rise to the possibility of comparing the two. We conducted Bayesian repeated-measures ANOVAs comparing the model in favour of the null and the model in favour of the alternative hypothesis resulting in a Bayes factor (BF) using Bayesian Information criteria [ 46 ]. The BF 01 suggests how much more likely the data is to occur under the null hypothesis. All analyses were performed using the JASP software package ( https://jasp-stats.org ).

Sex distribution in the present study did not differ across the groups ( χ 2 p -value > 0.414). However, due to the fact that differences between males and females have been observed in terms of aggression and empathy [ 47 ], we present analyses controlling for sex. Since our random assignment to the three groups did result in significant age differences between groups, with the passive control group being significantly older than the GTA ( t (51) = −2.10, p = 0.041) and the Sims group ( t (50) = −2.38, p = 0.021), we also controlled for age.

The participants in the violent video game group played on average 35 h and the non-violent video game group 32 h spread out across the 8 weeks interval (with no significant group difference p = 0.48).

To test whether participants assigned to the violent GTA game show emotional, cognitive and behavioural changes, we present the results of repeated-measure ANOVA time x group interaction analyses separately for GTA vs. Sims and GTA vs. Controls (Tables 1 – 3 ). Moreover, we split the analyses according to the time domain into effects from baseline assessment to posttest 1 (Table 2 ) and effects from baseline assessment to posttest 2 (Table 3 ) to capture more long-lasting or evolving effects. In addition to the statistical test values, we report partial omega squared ( ω 2 ) as an effect size measure. Next to the classical frequentist statistics, we report the results of a Bayesian statistical approach, namely BF 01 , the likelihood with which the data is to occur under the null hypothesis that there is no significant time × group interaction. In Table 2 , we report the presence of significant group differences at baseline in the right most column.

Since we conducted 208 separate frequentist tests we expected 10.4 significant effects simply by chance when setting the alpha value to 0.05. In fact we found only eight significant time × group interactions (these are marked with an asterisk in Tables 2 and 3 ).

When applying a conservative Bonferroni correction, none of those tests survive the corrected threshold of p < 0.00024. Neither does any test survive the more lenient FDR correction. The arithmetic mean of the frequentist test statistics likewise shows that on average no significant effect was found (bottom rows in Tables 2 and 3 ).

In line with the findings from a frequentist approach, the harmonic mean of the Bayesian factor BF 01 is consistently above one but not very far from one. This likewise suggests that there is very likely no interaction between group × time and therewith no detrimental effects of the violent video game GTA in the domains tested. The evidence in favour of the null hypothesis based on the Bayes factor is not massive, but clearly above 1. Some of the harmonic means are above 1.6 and constitute substantial evidence [ 48 ]. However, the harmonic mean has been criticised as unstable. Owing to the fact that the sum is dominated by occasional small terms in the likelihood, one may underestimate the actual evidence in favour of the null hypothesis [ 49 ].

To test the sensitivity of the present study to detect relevant effects we computed the effect size that we would have been able to detect. The information we used consisted of alpha error probability = 0.05, power = 0.95, our sample size, number of groups and of measurement occasions and correlation between the repeated measures at posttest 1 and posttest 2 (average r = 0.68). According to G*Power [ 50 ], we could detect small effect sizes of f = 0.16 (equals η 2 = 0.025 and r = 0.16) in each separate test. When accounting for the conservative Bonferroni-corrected p -value of 0.00024, still a medium effect size of f = 0.23 (equals η 2 = 0.05 and r = 0.22) would have been detectable. A meta-analysis by Anderson [ 2 ] reported an average effects size of r = 0.18 for experimental studies testing for aggressive behaviour and another by Greitmeyer [ 5 ] reported average effect sizes of r = 0.19, 0.25 and 0.17 for effects of violent games on aggressive behaviour, cognition and affect, all of which should have been detectable at least before multiple test correction.

Within the scope of the present study we tested the potential effects of playing the violent video game GTA V for 2 months against an active control group that played the non-violent, rather pro-social life simulation game The Sims 3 and a passive control group. Participants were tested before and after the long-term intervention and at a follow-up appointment 2 months later. Although we used a comprehensive test battery consisting of questionnaires and computerised behavioural tests assessing aggression, impulsivity-related constructs, mood, anxiety, empathy, interpersonal competencies and executive control functions, we did not find relevant negative effects in response to violent video game playing. In fact, only three tests of the 208 statistical tests performed showed a significant interaction pattern that would be in line with this hypothesis. Since at least ten significant effects would be expected purely by chance, we conclude that there were no detrimental effects of violent video gameplay.

This finding stands in contrast to some experimental studies, in which short-term effects of violent video game exposure have been investigated and where increases in aggressive thoughts and affect as well as decreases in helping behaviour have been observed [ 1 ]. However, these effects of violent video gaming on aggressiveness—if present at all (see above)—seem to be rather short-lived, potentially lasting <15 min [ 8 , 51 ]. In addition, these short-term effects of video gaming are far from consistent as multiple studies fail to demonstrate or replicate them [ 16 , 17 ]. This may in part be due to problems, that are very prominent in this field of research, namely that the outcome measures of aggression and pro-social behaviour, are poorly standardised, do not easily generalise to real-life behaviour and may have lead to selective reporting of the results [ 3 ]. We tried to address these concerns by including a large set of outcome measures that were mostly inspired by previous studies demonstrating effects of short-term violent video gameplay on aggressive behaviour and thoughts, that we report exhaustively.

Since effects observed only for a few minutes after short sessions of video gaming are not representative of what society at large is actually interested in, namely how habitual violent video gameplay affects behaviour on a more long-term basis, studies employing longer training intervals are highly relevant. Two previous studies have employed longer training intervals. In an online study, participants with a broad age range (14–68 years) have been trained in a violent video game for 4 weeks [ 52 ]. In comparison to a passive control group no changes were observed, neither in aggression-related beliefs, nor in aggressive social interactions assessed by means of two questions. In a more recent study, participants played a previous version of GTA for 12 h spread across 3 weeks [ 53 ]. Participants were compared to a passive control group using the Buss–Perry aggression questionnaire, a questionnaire assessing impulsive or reactive aggression, attitude towards violence, and empathy. The authors only report a limited increase in pro-violent attitude. Unfortunately, this study only assessed posttest measures, which precludes the assessment of actual changes caused by the game intervention.

The present study goes beyond these studies by showing that 2 months of violent video gameplay does neither lead to any significant negative effects in a broad assessment battery administered directly after the intervention nor at a follow-up assessment 2 months after the intervention. The fact that we assessed multiple domains, not finding an effect in any of them, makes the present study the most comprehensive in the field. Our battery included self-report instruments on aggression (Buss–Perry aggression questionnaire, State Hostility scale, Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance scale, Moral Disengagement scale, World View Measure and Rosenzweig Picture Frustration test) as well as computer-based tests measuring aggressive behaviour such as the delay frustration task and measuring the availability of aggressive words using the word completion test and a lexical decision task. Moreover, we assessed impulse-related concepts such as sensation seeking, boredom proneness and associated behavioural measures such as the computerised Balloon analogue risk task, and delay discounting. Four scales assessing empathy and interpersonal competence scales, including the reading the mind in the eyes test revealed no effects of violent video gameplay. Neither did we find any effects on depressivity (Becks depression inventory) nor anxiety measured as a state as well as a trait. This is an important point, since several studies reported higher rates of depressivity and anxiety in populations of habitual video gamers [ 54 , 55 ]. Last but not least, our results revealed also no substantial changes in executive control tasks performance, neither in the Stop signal task, the Multi-source interference task or a Task switching task. Previous studies have shown higher performance of habitual action video gamers in executive tasks such as task switching [ 56 , 57 , 58 ] and another study suggests that training with action video games improves task performance that relates to executive functions [ 59 ], however, these associations were not confirmed by a meta-analysis in the field [ 60 ]. The absence of changes in the stop signal task fits well with previous studies that likewise revealed no difference between in habitual action video gamers and controls in terms of action inhibition [ 61 , 62 ]. Although GTA does not qualify as a classical first-person shooter as most of the previously tested action video games, it is classified as an action-adventure game and shares multiple features with those action video games previously related to increases in executive function, including the need for hand–eye coordination and fast reaction times.

Taken together, the findings of the present study show that an extensive game intervention over the course of 2 months did not reveal any specific changes in aggression, empathy, interpersonal competencies, impulsivity-related constructs, depressivity, anxiety or executive control functions; neither in comparison to an active control group that played a non-violent video game nor to a passive control group. We observed no effects when comparing a baseline and a post-training assessment, nor when focussing on more long-term effects between baseline and a follow-up interval 2 months after the participants stopped training. To our knowledge, the present study employed the most comprehensive test battery spanning a multitude of domains in which changes due to violent video games may have been expected. Therefore the present results provide strong evidence against the frequently debated negative effects of playing violent video games. This debate has mostly been informed by studies showing short-term effects of violent video games when tests were administered immediately after a short playtime of a few minutes; effects that may in large be caused by short-lived priming effects that vanish after minutes. The presented results will therefore help to communicate a more realistic scientific perspective of the real-life effects of violent video gaming. However, future research is needed to demonstrate the absence of effects of violent video gameplay in children.

Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behavior: a meta-analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychol Sci. 2001;12:353–9.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Anderson CA, Shibuya A, Ihori N, Swing EL, Bushman BJ, Sakamoto A, et al. Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in eastern and western countries: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:151–73.

Article Google Scholar

Ferguson CJ. Do angry birds make for angry children? A meta-analysis of video game influences on children’s and adolescents’ aggression, mental health, prosocial behavior, and academic performance. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:646–66.

Ferguson CJ, Kilburn J. Much ado about nothing: the misestimation and overinterpretation of violent video game effects in eastern and western nations: comment on Anderson et al. (2010). Psychol Bull. 2010;136:174–8.

Greitemeyer T, Mugge DO. Video games do affect social outcomes: a meta-analytic review of the effects of violent and prosocial video game play. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2014;40:578–89.

Anderson CA, Carnagey NL, Eubanks J. Exposure to violent media: The effects of songs with violent lyrics on aggressive thoughts and feelings. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:960–71.

DeWall CN, Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. The general aggression model: theoretical extensions to violence. Psychol Violence. 2011;1:245–58.

Sestire MA, Bartholow BD. Violent and non-violent video games produce opposing effects on aggressive and prosocial outcomes. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46:934–42.

Kneer J, Elson M, Knapp F. Fight fire with rainbows: The effects of displayed violence, difficulty, and performance in digital games on affect, aggression, and physiological arousal. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;54:142–8.

Kneer J, Glock S, Beskes S, Bente G. Are digital games perceived as fun or danger? Supporting and suppressing different game-related concepts. Cyber Beh Soc N. 2012;15:604–9.

Sauer JD, Drummond A, Nova N. Violent video games: the effects of narrative context and reward structure on in-game and postgame aggression. J Exp Psychol Appl. 2015;21:205–14.

Ballard M, Visser K, Jocoy K. Social context and video game play: impact on cardiovascular and affective responses. Mass Commun Soc. 2012;15:875–98.

Read GL, Ballard M, Emery LJ, Bazzini DG. Examining desensitization using facial electromyography: violent video games, gender, and affective responding. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;62:201–11.

Szycik GR, Mohammadi B, Hake M, Kneer J, Samii A, Munte TF, et al. Excessive users of violent video games do not show emotional desensitization: an fMRI study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017;11:736–43.

Szycik GR, Mohammadi B, Munte TF, Te Wildt BT. Lack of evidence that neural empathic responses are blunted in excessive users of violent video games: an fMRI study. Front Psychol. 2017;8:174.

Tear MJ, Nielsen M. Failure to demonstrate that playing violent video games diminishes prosocial behavior. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e68382.

Tear MJ, Nielsen M. Video games and prosocial behavior: a study of the effects of non-violent, violent and ultra-violent gameplay. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;41:8–13.

Kühn S, Gleich T, Lorenz RC, Lindenberger U, Gallinat J. Playing super Mario induces structural brain plasticity: gray matter changes resulting from training with a commercial video game. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:265–71.

Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:452.

Anderson CA, Deuser WE, DeNeve KM. Hot temperatures, hostile affect, hostile cognition, and arousal: Tests of a general model of affective aggression. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1995;21:434–48.

Payne DL, Lonsway KA, Fitzgerald LF. Rape myth acceptance: exploration of its structure and its measurement using the illinois rape myth acceptance scale. J Res Pers. 1999;33:27–68.

McMahon S, Farmer GL. An updated measure for assessing subtle rape myths. Social Work Res. 2011; 35:71–81.

Detert JR, Trevino LK, Sweitzer VL. Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: a study of antecedents and outcomes. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93:374–91.

Bandura A, Barbaranelli C, Caprara G, Pastorelli C. Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71:364–74.

Rosenzweig S. The picture-association method and its application in a study of reactions to frustration. J Pers. 1945;14:23.

Hörmann H, Moog W, Der Rosenzweig P-F. Test für Erwachsene deutsche Bearbeitung. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1957.

Anderson CA, Dill KE. Video games and aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behavior in the laboratory and in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78:772–90.

Przybylski AK, Deci EL, Rigby CS, Ryan RM. Competence-impeding electronic games and players’ aggressive feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;106:441.

Bitsakou P, Antrop I, Wiersema JR, Sonuga-Barke EJ. Probing the limits of delay intolerance: preliminary young adult data from the Delay Frustration Task (DeFT). J Neurosci Methods. 2006;151:38–44.

Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT, Palmgreen P, Lorch EP, Donohew RL. Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Pers Individ Dif. 2002;32:401–14.

Farmer R, Sundberg ND. Boredom proneness: the development and correlates of a new scale. J Pers Assess. 1986;50:4–17.

Lejuez CW, Read JP, Kahler CW, Richards JB, Ramsey SE, Stuart GL, et al. Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk taking: the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART). J Exp Psychol Appl. 2002;8:75–84.

Richards JB, Zhang L, Mitchell SH, de Wit H. Delay or probability discounting in a model of impulsive behavior: effect of alcohol. J Exp Anal Behav. 1999;71:121–43.

Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Cat Sel Doc Psychol. 1980;10:85.

Google Scholar