Talking Point

Why study art?

Find out why art education is important from artists, young people and major cultural figures

Art in schools shouldn’t be sidelined… it should be right there right up in the front because I think art teaches you to deal with the world around you. It is the oxygen that makes all the other subjects breathe Alan Parker, filmmaker

Arts education is in crisis. In the UK, school time and budgets are under pressure and school inspections increasingly value ‘core’ subjects as the indicators of school level and success. Subjects including art, music and drama are often sidelined in the curriculum. This has led to a steady decline in the number of students choosing to study arts subjects at school.

In 2018 a landmark research project commissioned by Arts Council England, and undertaken by the University of Nottingham, called Tracking Learning and Engagement in the Arts (TALE) outlined the overwhelmingly positive benefits of arts and cultural education for young people. The research drew from the experience and voices of thousands of young people and their teachers in secondary and special schools.

We have pulled together some of these voices and findings from TALE and other research, as well as helpful resources on studying art.

Whether you’re choosing art as a GCSE; would like to study art or design at university; or are a parent or teacher interested in arts education: explore, join in and have your say!

Why is it important to study art?

School in general is so stressful… this is the one lesson I look forward to every week because I know it’s not going to majorly stress me out. Student, Three Rivers Academy, Surrey

[School is] all very robotic. It’s all very, it needs to be this, this and this. You can’t do this because it is wrong. It’s all following a strict script. That’s not what we’re made to do. We’re made to be our own person, we’re made to go off and do something that someone else hasn’t done before. Student, Ark Helenswood, Hastings

Creativity is critical thinking and without it how are you going to open up and ask harder questions? Art opens up those… possibilities to think beyond what we already know. Catherine Opie, artist

Learning through and about the arts enriches the experience of studying while at school as well as preparing students for life after school.

- Arts subjects encourage self-expression and creativity and can build confidence as well as a sense of individual identity.

- Creativity can also help with wellbeing and improving health and happiness – many students in the TALE study commented that arts lessons acted as an outlet for releasing the pressures of studying as well as those of everyday life.

- Studying arts subjects also help to develop critical thinking and the ability to interpret the world around us.

What are art lessons like? What do you learn?

You feel free because it’s just you sitting down, doing your work. No one is there to tell you what to do. It is just you, sitting there and expressing yourself, and sometimes we listen to music, which is helpful because you get new ideas. Student, Archbishop Tenison School, south London

Art is a non pre-prescribed dangerous world full of possibilities. Cate Blanchett, actor

The art room is a very different space to other spaces in the school. On her visit to Archbishop Tenison School in London TALE researcher Lexi Earl describes the bustle of the art classroom:

‘There are piles of sketchbooks, jars with pencils, paintbrushes, sinks splattered with paint. There are large art books for students to reference. Often there is a kiln, sometimes a dark room too. There are trays for drying work on, or work is pegged up over the sink, like clothing on a washing line.’

- The art room is a space where students have the freedom to express their ideas and thoughts and work creatively.

- The way art is taught means that interaction with other students and with the teacher is different in art and design classes. Students comment on the bonds they form with classmates because of their shared interests and ideas. The art teacher is someone they can bounce ideas off rather than telling them what to do.

- Studying art and design provides the opportunity to acquire new skills. As well as knowledge of different art forms, media and techniques you can also gain specialist skills in areas such as photography and digital technologies.

Have your say!

Do you think art is important? Do you think the arts should be an essential part of education? How do you think studying art is useful for the future?

Why Study Art? 2018 is an artwork by collective practice They Are Here commissioned by the Schools and Teachers team at Tate. The inspiration for the artwork was prompted by Mo, a 14 year old workshop participant who told the artists that ‘art is dead’.

All responses are welcome whether you’ve studied art or not! (You will be re-directed to the Why Study Art? artwork site).

Tate champions art in schools

ASSEMBLY at Tate Modern © Tate

Every year Tate Modern hosts ASSEMBLY, a special event for around 1500 London school students and their teachers. The students are invited to occupy, explore and take part in activities in Tate’s Blavatnik building and Turbine hall – which are closed to all other visitors.

This annual event, first staged in 2016 which invited schools from all over the UK, reflects Tate’s mission to champion the arts as part of every child’s education. The project aims to highlight not only the importance of visual culture in young people's lives, but the importance of those young people as future producers of culture.

Research at Tate

Tracking Arts Learning and Engagement (TALE) was a collaborative research project involving Tate, The Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) and the University of Nottingham. The research focused on thirty secondary schools spread across England and included three special schools.

Over three-years (2015 – 2018) the research investigated four main questions:

- What do teachers learn from deep engagement with cultural organisations?

- How do teachers translate this learning into the classroom?

- What do pupils gain from these learning experiences?

- What do the two different models of teacher professional development at Tate and RSC offer and achieve?

See the findings of the project and explore fascinating insights through the project blogs that feature the voices of students and teachers interviewed during the research.

I don’t want to be an artist – why bother studying art?

It doesn’t matter if you’re going to study history or geography or science, you still need to be creative because the people who are the outliers in those fields are the most creative people. To have art eroded in schools is disastrous… Cornelia Parker, artist

Those skills go with you for the rest of your life as well. If you go for an interview, if they can see that you’re confident it is better for them because they know that they can ask questions that need to be asked. Student, Ark Helenwood, Hastings

Art may not be your favourite subject, but studying the arts alongside other subjects significantly boosts student achievement. Schools that integrate arts into their curriculum show improved student performance in Maths, English, critical thinking and verbal skills.

Arts education can also help with developing skills and ways of working that will benefit you in the future in whatever career you choose.

- The leading people in any field are those who can think creatively and innovatively. These are skills that employers value alongside qualifications. Making and participating in the arts aids the development of these skills

- When you study art you learn to work both independently and collaboratively, you also gain experience in time management – skillsets valued by employers

- Studying the arts teaches determination and resilience – qualities useful to any career. It teaches us that it is okay to fail, to not get things totally right the first time and to have the courage to start again. As a drama student at King Ethelbert’s School, Kent commented: ‘Like with every yes, there is like 10 nos… It has taught me that if I work on it, I will get there eventually. It is determination and commitment. It has definitely helped’

Is art good for society and communities generally?

You don’t have innovation if you don’t have arts. It’s as simple as that Anne-Marie Imafidon, CEO of Stemettes which encourages girls to pursue careers in science and technology

It was really when I was at art school that I started to see the relationship between history, philosophy, politics and art. Prior to that I thought that art was just making pretty pictures – actually art is connected to life. Yinka Shonibare, artist

Art and cultural production is at the centre of what makes a society what it is Wolfgang Tillmans, artist

Arts and cultural learning is more important than ever for the health of our communities and our society

Creativity is essential in a global economy that needs a workforce that is knowledgeable, imaginative and innovative. Studying arts subjects also increases social mobility – encouraging and motivating students from low-income families to go into higher education. Studying the arts can also help with understanding, interpreting and negotiating the complexities and diversity of society

- Students from low-income families who take part in arts activities at school are three times more likely to take a degree

- By making art a part of the national curriculum, we give the next generation of artists, designers, engineers, creators and cultural leaders the opportunity to develop the imagination and skills that are vital to our future

- Engagement with the arts helps young people develop a sense of their own identity and value. This in turn develops personal responsibility within their school and wider community

- Arts and cultural learning encourages awareness, empathy and appreciation of difference and diversity and the views of others

Tate Collective

Tate Collective is for young people aged 15 to 25 years old. Its aim is to facilitate new young audiences in creating, experimenting and engaging in our galleries and online with Tate's collection and exhibitions.

In 2018 Tate launched £5 exhibition tickets for Tate Collective members. If you are 16 to 25 sign-up free to Tate Collective. You don’t have to live in the UK – young people anywhere in the world can join! Enjoy the benefits of exhibition entry for £5 (you can also bring up to three friends to shows, each for £5); as well as discounts in Tate’s cafes and shops.

I love art – but can it be a career?

Studying art and design at school opens the door to a range of careers in the creative industries. The creative industries, which include art, design and music, are an important part of the British economy – one of the areas of the economy that is still growing.

Art lessons at school include teaching functional and useful skills that prepare students for future careers in the arts. Art departments also forge links with arts organisations and creative practitioners, companies and agencies. They organise visits and workshops which provide inspiring opportunities to for students to see what it’s like to ‘do’ a particular job and hear how artists and designers got where they are. As a student at Uxbride High School commented:

When it is from someone who has actually been through it and does it now you get the push where you’re like ‘oh, so I could actually genuinely do that myself’, without having a teacher say it to you.

If you are interested in pursuing a career in art and design explore our art school and art career resources:

Working at Tate

Find out about working at Tate including how to apply, current jobs or vacancies and what we do

Art School Debate

Battling about where to study art or whether it's a good idea? Get a second opinion from those in the know...

Explore more

Student resources.

From GCSE and A level exam help and advice on applying for art school, to fun resources you can use when you visit our galleries.

Play, make and explore on Tate Kids

Why Study Art from the Past?

Attributed to the Maestro delle Storie del Pane (Italian [Emilian], active late 15th century). Portrait of a Man, possibly Matteo di Sebastiano di Bernardino Gozzadini (left) and Portrait of a Woman, possibly Ginevra d'Antonio Lupari Gozzadini (right), ca. 1485–95. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.95, 96)

«Art from the past holds clues to life in the past. By looking at a work of art's symbolism, colors, and materials, we can learn about the culture that produced it.» For example, the two portraits above are full of symbolism referring to virtues of an ideal marriage during the fifteenth century. The young woman's portrait contains symbols of chastity (the unicorn) and fertility (the rabbits), virtues that were important for a Renaissance woman to possess. After decoding the symbolism in these portraits, we can learn what was important to these people and how they wanted to be remembered.

We also can compare artwork, which provides different perspectives, and gives us a well-rounded way of looking at events, situations, and people. By analyzing artworks from the past and looking at their details, we can rewind time and experience what a time period different from our own was like.

Looking at art from the past contributes to who we are as people. By looking at what has been done before, we gather knowledge and inspiration that contribute to how we speak, feel, and view the world around us.

Related Links Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History : Portrait of a Man, possibly Matteo di Sebastiano di Bernardino Gozzadini ; and Portrait of a Woman, possibly Ginevra d'Antonio Lupari Gozzadini

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History : " Paintings of Love and Marriage in the Italian Renaissance "

What do you think we can learn from looking at works of art from the past?

We welcome your responses to this question below.

Kristen undefined

Kristen is a member of the Museum's Teen Advisory Group.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Courtney B. Vance, Angela Bassett honored as Artists of the Year

Is Beyoncé’s new album country?

Storytelling through body language

Project Zero senior researcher Ellen Winner’s latest book, “How Art Works: A Psychological Exploration,” is based on years of research at Harvard and Boston College.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

The aesthetic attitude to art

Colleen Walsh

Harvard Staff Writer

Harvard researcher’s latest book explores how and why we react to it

Ellen Winner ’69, Ph.D. ’78, BI ’99 concentrated in English at Radcliffe, but she’d always planned to be an artist. She attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts after college to study painting but soon realized “it was not the life I wanted.” Instead, Winner turned her focus to psychology, earning her doctorate at Harvard.

A summer job listing at the University’s career office led her to the Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Project Zero, where she interviewed with her future husband, Howard Gardner — currently the John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs Professor of Cognition and the senior director of the project — and took a two-year position researching the psychology of art. For her doctoral degree at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Winner studied developmental psychology. She is currently a senior research associate at Project Zero and a professor of psychology at Boston College, where she founded and directs the Arts and Mind Lab , which focuses on cognition in the arts in typical and gifted children as well as adults. Her latest book, “How Art Works: A Psychological Exploration,” is based on years of research at both Harvard and BC, and looks at art through psychological and philosophical lenses. The Gazette spoke with her recently about her findings.

Ellen Winner

GAZETTE: Why do we need art?

WINNER: It’s interesting to note that the arts have been with us since the earliest humans — long before the sciences — and no one has ever discovered a culture without one or more forms of art. Evolutionary psychologists have postulated various ways in which natural selection could explain why we have art. For example, fiction allows us to safely practice interpersonal relationships and those with strong interpersonal skills are more likely to mate and spread their genes. Sexual selection could also be at work: Artists might attract mates because artistic talent might signal high reproductive fitness. There is no way of testing such claims, though. My best guess is that art itself is not a direct product of natural selection, but is a byproduct of our bigger brains — which themselves evolved for survival reasons. Art is just something we cannot help but do. While we may not need art to survive, our lives would be entirely different without it. The arts are a way of making sense of and understanding ourselves and others, a form of meaning-making just as important as are the sciences.

GAZETTE: In your book you suggest that people have stronger emotional reactions to music than to the visual arts. Why?

WINNER: Of course, we do respond emotionally to both music and visual art, but people report stronger emotional responses to music. I have asked my students to look at a painting for one uninterrupted hour and write down everything they are seeing and thinking (inspired by Jennifer Roberts, art historian at Harvard, who asked her students to do this for three hours). The students wrote about all of the things they started to notice, but strikingly absent was any mention of emotions. They reported being mesmerized by the experience but no one talked about being close to tears, something people often report with music.

There seem to be several reasons for music eliciting stronger emotional reactions than the visual arts. The experience of music unrolls over time, and often quite a long time. A work of visual art can be perceived at a glance and people typically spend very little time with each work of art they encounter in a museum. We can turn away from a painting, but we can’t turn away from music, and so a painting doesn’t envelop us in the same way music does. In addition, music, but not visual art, makes us feel like moving, and moving to music intensifies the emotional reaction. One of the most powerful explanations for the emotional power of music has to do with the fact that the same properties that universally convey emotion in the voice (tempo, volume, regularity, etc.) also convey emotion in music. Thus, for example, a slow tempo in speech and music is typically perceived as sad, a loud and uneven tempo as agitated, etc. The visual arts do not have such a connection to emotion. Movies may be the most powerful art form in eliciting emotion since they unfold over time, tell a story, and of course include music.

GAZETTE: Can you talk more about your studies involving a person’s ability to distinguish between artwork by an abstract master and a painting done by a monkey with a paintbrush and palette?

WINNER: We were interested in the often-heard claim about abstract art that, “My kid could have done that.” We wanted to find out whether people really cannot tell the difference between preschool art and the works of great abstract expressionists like Hans Hofmann or Willem de Kooning. We also threw animal art into the mix: Chimps and monkeys and elephants have been given paint brushes laden with paint, and they often make charming, childlike markings — with the experimenter taking the paper away when the experimenter deems it “finished.” My former doctoral student Angelina Hawley-Dolan created 30 pairs of paintings in which she matched works by abstract expressionists with works by children and animals — matched so that the members of each pair were superficially similar in color and composition and kinds of brush strokes. In a series of studies, we showed people these pairs and asked them to decide which work was better, which they liked more, and which was done by an artist rather than a child or animal. Sometimes we unpaired the works and asked people the same questions when they were presented one at a time.

“When you hear someone say, ‘My kid could have done that,’ you can say, ‘Not so!’”

We found in each study that people unschooled in abstract expressionism selected the artists’ works as better and more liked, identified them as by artists rather than animals and children, and did this at a rate significantly above chance. Even when we tried to trick people (mislabeling the child work as by an artist and the artist work as by a child or animal), people recognized the actual artist’s work as the better work of art, uninfluenced by the false label. In addition, working with a computer scientist, we showed that a deep learning algorithm was able to learn to differentiate works by artists versus by children and animals, and succeeded at the same rate of correctness as did humans. And so, when you hear someone say, “My kid could have done that,” you can say, “Not so!”

GAZETTE: What do you think was going on?

WINNER: To get at this we asked another group of people to look at each of the 60 paintings, 30 by the preschoolers and animals and 30 by the great artists, one at a time and randomly ordered. We asked them to rate each work in terms of how intentional it looked, and how much visual structure they saw. The works by the artists were on average rated as more intentional and higher in visual structure. When we asked people why they thought the artists’ paintings were better works of art, they gave us mentalistic answers, saying things like, “It looks more planned” or, “It looks more thought-out.” So, it appears that we make a clear discrimination: We perceive artists’ abstract paintings as highly planned, and those by children and animals as unplanned and somewhat random. Tellingly, we found that some paintings by artists were incorrectly identified as by children or animals, and these turned out to be the ones that had been rated as low in intentionality and structure. Our conclusion is that people see more in abstract art than they think they see. They can see the mind behind the work.

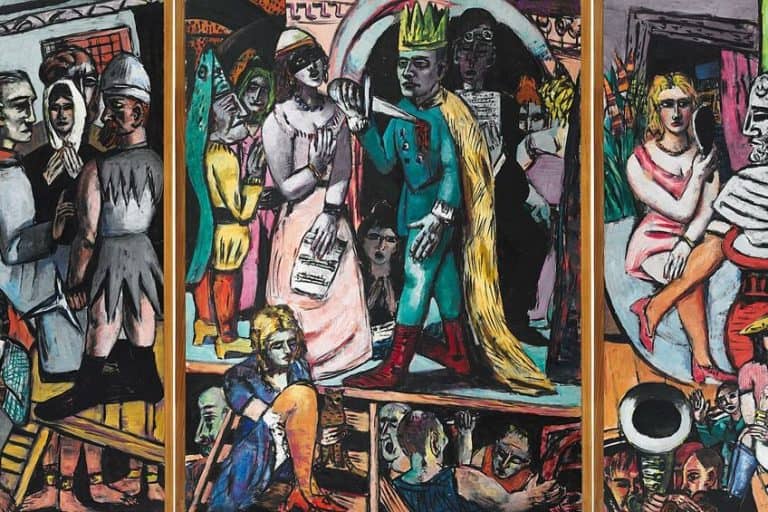

GAZETTE: You mention that art that evokes negative emotions can also be positive thing. Can you explain?

More like this

Seeing more

The nature of sounds

Songs in the key of humanity

WINNER: We gravitate toward art that depicts tragic or horrifying events (think of paintings by Hieronymus Bosch or Lucian Freud, whose portraits are often distorted and somewhat grotesque); we flock to sad or suspenseful or horrifying movies or plays or novels; we listen to music that conveys grief. Given how we strive to avoid feelings of sorrow and terror and horror in our personal lives, this presents us with a paradox — one that interested philosophers such as Aristotle, Immanuel Kant, and David Hume. This puzzle is resolved by studies showing that when we view something as art, any negative feelings about the content are matched by positive ones. For instance, one study demonstrated that presenting photographs of disgusting things like rotting food either as art photography or illustrations to teach people about hygiene led to different reactions: Those who viewed the images as art reported positive feelings along with the negative ones; those who viewed them as hygiene illustrations reported only negative feelings. Other studies have shown that people report being highly moved by art with negative content, and the experience of feeling moved combines negative affect with an equal level of positive affect. In short, we can allow ourselves to be moved by tragedy and horror in art because it is not about us; we have entered a fictional world of virtual reality. And the experience of being moved by such works is not only pleasurable, but can also be highly meaningful as we reflect on the nature of our feelings.

GAZETTE: You also explore how theater can inspire empathy.

WINNER: We often hear that the arts are good for our children because they make them more empathetic. But this is the kind of claim that ought to be closely examined. Is there truth to this claim, and if so does it apply to all the arts? My former doctoral student Thalia Goldstein, now an assistant professor at George Mason University, reasoned that it is in acting that empathy is most likely to be nurtured. She directed a longitudinal study of children and adolescents involved in acting classes over the course of a year, comparing them to students taking visual arts classes. At the end of the year, the acting students in both age groups had gained more than the visual arts students on a self-report empathy scale, and the adolescent acting students had also grown stronger in perspective-taking. These results have the plausible explanation that acting entails stepping into different characters’ shoes over and over, practicing seeing the world from another’s eyes.

There is still a lot we don’t know about the arts and empathy. Does reading fiction or watching a drama on stage have the same effect as enacting fictional characters? And if so, can any of these experiences change people’s behaviors (in the direction of greater compassion), or do they just change people’s ability to identify and mirror what others are feeling? The answer is not obvious. William James asked us to consider a person at the theater weeping over the fate of a fictional character onstage while unconcerned about her freezing coachman waiting outside in the snow. It is possible that when we expend our empathy on fictional characters, we feel we have paid our empathy dues. This fascinating problem cries out for further research, which I hope to be able to do.

GAZETTE: After all of your research, have you landed on any concise definition of what art is?

WINNER: Since philosophers have been unable to agree on a definition of art that involves necessary and sufficient features, I certainly do not think that I will come up with one! Art will never be defined in a way that will distinguish all things we do and do not call art. Art is a mind-dependent concept: There is no litmus test to decide whether something is or is not art (as opposed to whether some liquid is or is not water). Our minds group together the things we call art despite the fact that no two instances of “art” need share any features. And artists are continually challenging our concept of what counts as art, making the concept impossible ever to close.

But philosophers such as Nelson Goodman, who was the founder of Project Zero at the Harvard Graduate School of Education — a group that had a deep influence on my thinking — had something profound to say about this. Don’t ask, “What is art?”; rather, ask, “When is art?” Anything can be treated as art or not. And when we treat something as art, we attend to it in a special way — for example, noting its surface formal features and its nonliteral expressive features as part of the many meanings of the work. So maybe we can’t define art, but we can specify what it means to adopt an aesthetic attitude. And while elephants and chimps may make “art,” and while birds may make “music,” I am confident that humans are the only creatures who step back from something they are making to decide how it looks or sounds and how it should be altered — in short, to adopt that aesthetic attitude.

Share this article

You might like.

Cultural Rhythms’ weeklong celebration highlights student performers, food, and fashion

Release ignites hot talk about genre’s less-discussed Black roots, what constitutes authenticity

Veteran of Blue Man Group teaches students art of building a character without saying a word

College accepts 1,937 to Class of 2028

Students represent 94 countries, all 50 states

Pushing back on DEI ‘orthodoxy’

Panelists support diversity efforts but worry that current model is too narrow, denying institutions the benefit of other voices, ideas

So what exactly makes Taylor Swift so great?

Experts weigh in on pop superstar's cultural and financial impact as her tours and albums continue to break records.

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

Why Study Art History? Awesome Ways It Can Impact Your Life

Art history is all about knowing where we come from and where we’ve been, from the perspective of works of art. Art history is also about knowing how art has changed over time. Both of which are more relevant than you think. Why study art history? Let’s count the many reasons.

Art Vs. Artifact: What Is Art History?

It’s an excellent question — what makes something art , and what makes something an artifact? Furthermore, what separates an artist from an artisan? The answers may lie in the study of art history.

Some say art is made of creativity, originality, or imagination. Art historians say that art is visually striking, and blends beauty and culture.

Studying art is to look at a piece of art and see the artist’s use of lines, shape, composition, tecture, and approach, and to make inferences about their intentions and meaning.

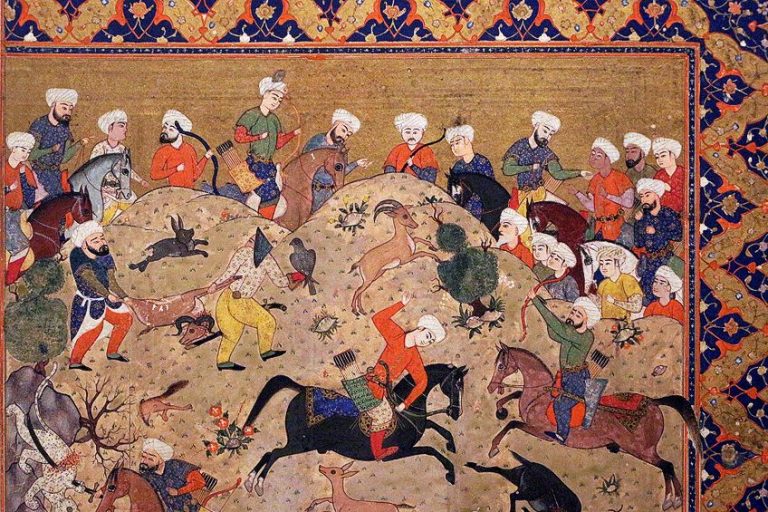

Art history is looking at those same aspects, throughout periods of history, to learn more about a certain time period or peoples.

Photo by Aaron J on Unsplash

Why study art history.

So, why study art history, you ask? So many reasons!

1. Every Picture Has A Story

Learning about art history can be fun, and the most fun part about it is uncovering the story behind the art piece. Looking at a picture, performance, or physical object, you get to be a detective searching for meaning behind what you see in front of you. You get to find the story behind the picture.

2. There’s More To Art History Than You Think

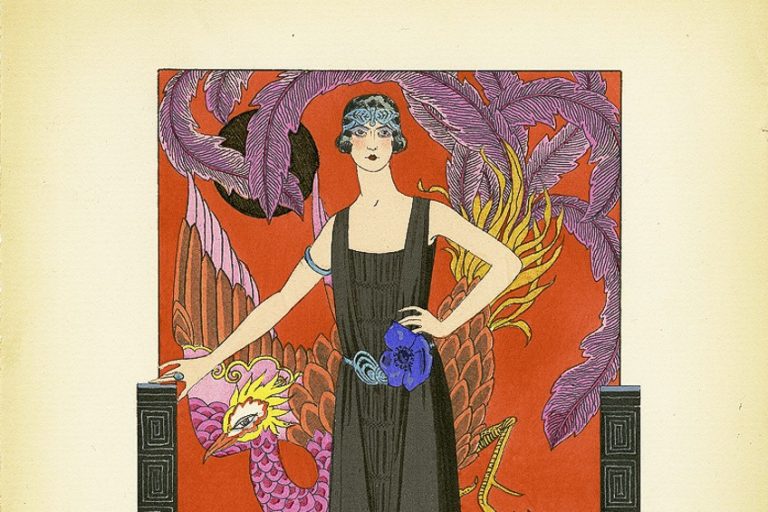

Many people think of art history as just memorizing old paintings from the 15th century. That is not the case! Art is much more than just paintings. In art history, you study all types of art — from film, to media, landscaping, ceramics, arms and armour, furniture, fashion and jewelry, photography, performances, and more.

Photo by Tim Gouw on Unsplash

3. art history strengthens your skills.

There is so much more to art history than just memorizing names, dates, and images. Studying art history makes you become a master of visual analysis, written communication, and critical thinking. There is plenty of writing in art history as well, and you may become an expert writer and communicator if you study art history.

4. We Live In A Visual World

In today’s world, everything is visual — just think of how much of your day is spent looking at a computer, tablet, television, or phone screen. We are processing images, both moving and still, all day long. Everyone is shifting from verbal thinking to visual thinking, and art history is one of the best ways to prepare for this, and succeed in this new visual world.

5. Art History Is Your History

True, we are all part of the human race, so any piece of art created by humans is technically our history. But beyond that, make art history your own by studying more about the art history that came specifically from your culture or your ancestors. You’ll gain a deeper understanding of your past and your present self if you can connect to art works of your people’s past.

6. Making Sense Of The Past

Studying art history helps us to make sense of the past. Art shows us what was important and valuable over time from depictions within the art itself. Equally important, we learn what aspects of life were significant for certain cultures over time.

For example, we can find great European paintings from certain periods of time, beautiful African masks from other cultures and times, and econic gold jewelry from Central and South America. Each has their own explanation of the time period they were made in.

Photo by Monika Braskon on Unsplash

What does it mean to study art history.

Well, it certainly doesn’t mean spending time in old museums or with hundreds of flashcards, as you may have thought. Getting a degree in art history usually means you also have a choice of specialization in areas such as performing arts, literature or music. You will study all things art, and how art changes over history. To study art history, you also need to have a background in philosophy, language arts, and other social sciences.

What Are The Benefits Of Studying Art History?

Incorporating so many fields such as history, economics, anthropology, political science, design, and aesthetics means that you reap many benefits of studying this discipline. By studying art history, you learn to draw conclusions, make inferences, argue a point, and increase your skills such as critical thinking , visual comprehension, and written communication.

What Can We Learn From Works Of The Past?

Art gives us clues to what life was like in the past. Just by identifying an art piece’s colors, materials, and symbolism, we can learn about the culture and time period that created it. We can learn what was important to those people, and how they wanted these importances to be remembered.

Looking at art from the past by studying art history can contribute to who we are as a people today. We can look at what has been done before us, and are able to view the world today with more complete perspectives and better understanding.

The Bottom Line

Why study art history? Art history tells a story, and studying art means you get to uncover the past. Not only can art history be fun and rewarding, but you’ll improve your critical thinking skills, and learn so much along the way.

Related Articles

Ever wondered…why study art of the past?

Special thanks Rachel Bower, Nicole Gherry, Livia Alexander, Derek Burdette, Rachel Miller, Kim Richter, and Rachel Barron-Duncan whose voices and insights are featured here.

This video was made possible thanks to the Macaulay Family Foundation

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY

Why study art history.

Art history provides an excellent opportunity to develop the essential skills and talents that lie at the core of a good liberal arts education, including informed and critical reading, writing, and speaking. To these, it adds a particular attention to critical looking, building core skills in analyzing how the visual and physical qualities of buildings, images and objects can be used to communicate. In art history, we study the art and architecture of cultures around the world and across the millennia. We take a variety of approaches to our objects, but focus on understanding their aesthetic and historical significance as well as their social relevance. We ask how people make meaning in visual terms and, in turn, how we read and understand a world that is largely presented to us as visual information. Since Chicago is fortunate enough to boast a large number of world-famous museum collections and some of the world’s most extraordinary architecture, many of our classes emphasize on-site study and field trips.

With its broad historical, cultural, geographic, and methodological range, art history satisfies the expectations of burgeoning specialists while it also offers an excellent formation for those who intend to specialize in other areas. While many of our majors go on to careers in museums, galleries, arts reporting or academe, many others have successfully brought the skills honed in art history classrooms to the worlds of business, law, medicine and international relations.

Why Should I Study Art History?

- Art History

- Architecture

Each semester students find themselves enrolled in Art History classes for the first time. Ideally, they enrolled because they wanted to study the history of art and are enthusiastic about the prospect. This isn't always the case, however. Students may take Art History because it is required, or it seems like a good choice for AP credit in high school, or even because it is the only elective that fits into that semester's class schedule. When one of the latter three scenarios apply and a student realizes that Art History is not going to be an easy "A," questions invariably arise: why did I take this class? What's in it for me? Why should I study art history?

Why? Here are five compelling reasons to cheer you.

Because Every Picture Tells a Story

The single most fun reason to study Art History is the story it tells, and that doesn't just apply to pictures (that was merely a catchy headline for folks who were Rod Stewart fans back in the day).

You see, every artist operates under a unique set of circumstances and all of them affect his or her work. Pre-literate cultures had to appease their gods, ensure fertility and frighten their enemies through art. Italian Renaissance artists had to please either the Catholic Church, rich patrons, or both. Korean artists had compelling nationalistic reasons to distinguish their art from Chinese art. Modern artists strove to find new ways of seeing even while catastrophic wars and economic depression swirled around them. Contemporary artists are every bit as creative, and also have contemporary rents to pay—they need to balance creativity with sales.

No matter which piece of art or architecture you see, there were personal, political, sociological, and religious factors behind its creation. Untangling them and seeing how they connect to other pieces of art is huge, delicious fun.

Because There Is More to Art History than You May Think

This may come as news, but art history is not just about drawing, painting, and sculpture. You will also run across calligraphy, architecture , photography, film, mass media, performance art , installations, animation, video art, landscape design, and decorative arts like arms and armor, furniture, ceramics, woodworking, goldsmithing, and much more. If someone created something worth seeing—even a particularly fine black velvet Elvis—art history will offer it to you.

Because Art History Hones Your Skills

As was mentioned in the introductory paragraph, art history is not an easy "A." There is more to it than memorizing names, dates, and titles.

An art history class also requires you analyze, think critically, and write well. Yes, the five paragraph essay will rear its head with alarming frequency. Grammar and spelling will become your best friends, and you cannot escape citing sources .

Don't despair. These are all excellent skills to have, no matter where you want to go in life. Suppose you decide to become an engineer, scientist, or physician—analysis and critical thinking define these careers. And if you want to be a lawyer, get used to writing now. See? Excellent skills.

Because Our World Is Becoming More and More Visual

Think, really think about the amount of visual stimulation with which we are bombarded on a daily basis. You are reading this on your computer monitor, smartphone, iPad or tablet. Realistically, you may own all of these. In your spare time, you might watch television or videos on the internet, or play graphic-intensive video games. We ask our brains to process immense amounts of images from the time we wake until we fall asleep—and even then, some of us are vivid dreamers.

As a species, we are shifting from predominantly verbal thinking to visual thinking. Learning is becoming more visually- and less text-oriented; this requires us to respond not just with analysis or rote memorization, but also with emotional insight.

Art History offers you the tools you need to respond to this cavalcade of imagery. Think of it as a type of language, one that allows the user to successfully navigate new territory. Either way, you benefit.

Because Art History Is YOUR History

Each of us springs from a genetic soup seasoned by innumerable generations of cooks. It is the most human thing imaginable to want to know about our ancestors, the people who made us us . What did they look like? How did they dress? Where did they gather, work, and live? Which gods did they worship, enemies did they fight, and rituals did they observe?

Now consider this: photography has been around less than 200 years, film is even more recent, and digital images are relative newcomers. If we want to see any person that existed prior to these technologies we must rely on an artist. This isn't a problem if you come from a royal family where portraits of every King Tom, Dick, and Harry are hanging on the palace walls, but the other seven-or-so billion of us have to do a little art-historic digging.

The good news is that digging through art history is a fascinating pastime so, please, grab your mental shovel and commence. You will discover visual evidence of who and where you came from—and gain some insight on that genetic soup recipe. Tasty stuff!

- Free Art History Coloring Pages

- 10 Tips for Art History Students

- 13 Things Aspiring Architects Need to Know

- 10 Topic Ideas for Art History Papers

- What Is Meant by "Emphasis" in Art?

- How to Homeschool Art Instruction

- An Art History Timeline From Ancient to Contemporary Art

- The Feminist Movement in Art

- Tips for Writing an Art History Paper

- Art History 101: A Brisk Walk Through the Art Eras

- What Are the Visual Arts?

- Art History: Difference Between Era, Period, and Movement

- Art of the Civil Rights Movement

- The Proto-Renaissance - Art History 101 Basics

- Romanticism in Art History From 1800-1880

- Great Summer Dance Programs for High School Students

Department of Art History

Why Study Art History?

Art history teaches students to analyze the visual, sensual evidence to be found in diverse works of art, architecture, and design in combination with textual evidence. By honing skills of close looking, description, and the judicious use of historical sources, art history offers tools and vocabulary for interpreting the wealth of visual culture that surrounds us, as well as building a historically grounded understanding of artistic production in varied social and cultural contexts.

The major and minor in art history, as well as the minor in architectural studies, introduce students to a diversity of cultures and approaches that reflect the correspondingly global and interdisciplinary commitments of the department. Courses frequently draw upon the rich collections of the Smart Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Field Museum, and other cultural institutions across the city as well as the city’s built environment in order to enhance traditional classroom experiences with the distinctive kind of object-driven learning that art history has to offer.

The unique combination of skills that art history teaches—visual analysis and its written communication—are valuable to any future career. University of Chicago art history students have gone on to work in academia, museums, art galleries, and auction houses, as well as to careers in architecture, preservation, finance, consulting, advertising, law, and medicine.

Department of History of Art

Art both reflects and helps to create a culture’s vision of itself. Studying the art of the past teaches us how people have seen themselves and their world, and how they want to show this to others.

Why study history of art?

Art history provides a means by which we can understand our human past and its relationship to our present, because the act of making art is one of humanity’s most ubiquitous activities.

As an art historian you will learn about this rich and fundamental strand of human culture. You will learn to talk and write about works of art from different periods and places, in the same way that other students learn to write about literature or history.

But you will also learn skills unique to art historians. You will learn to make visual arguments and, above all, you will train your eyes and brain in the skills of critical looking. Don't take our word for it! Neuroscientists have shown that trained art historians see the world differently .

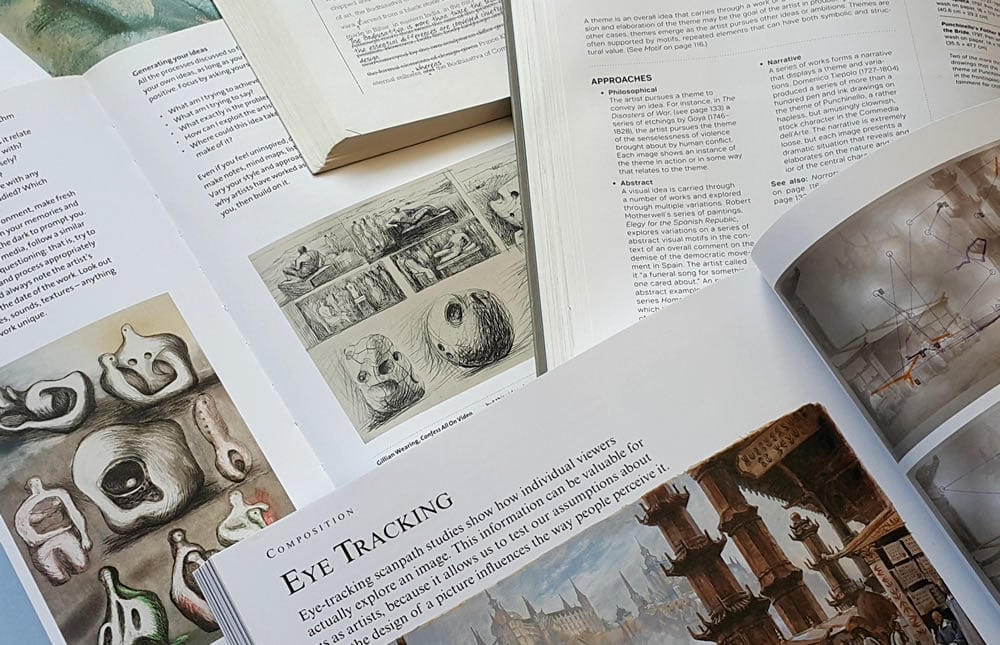

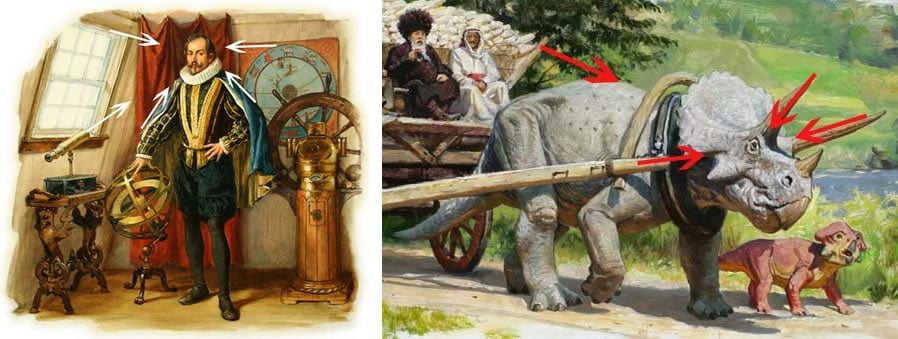

Scientists have tracked the movements of an art historian’s eyes: the results show how they scan, fixate and linger on particular points of the canvas reveals their skill and is entirely different to someone with an untrained eye.

Prospective Students

Why Study the Arts?

“By participating in the arts, our students develop cognitive abilities and forms of intelligence that complement training in other disciplines, and in some cases they discover talents and interests that will shape their careers and principal avocations.” – Shirley M. Tilghman (Princeton University President, 2001 – 2013)

The Princeton campus is always buzzing with creativity: plays, readings, a capella concerts in the archways, breakdancing and bhangra and everything in between. But art isn’t just for kicks—it’s a cornerstone of the academic life of the University. Art makes us human. It helps us to make sense of our own lives and identify with the lives of others. It is also increasingly recognized as a driver of the innovative thinking needed to solve our world’s most pressing problems. Learning and practicing art, and tapping into your creativity, can make you better at whatever you do. So in your four years at Princeton (which will race by), do yourself a favor: take a course in the Lewis Center for the Arts. You have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to explore and make art with some of the best working artists who will ever set foot in a classroom, as well as unparalleled resources to make your creative visions a reality.

Photo by Denise Applewhite

Photo by Frank Wojciechowski

Photo by Bentley Drezner

Photo by Kemy Lin

Receive Lewis Center Events & News Updates

Get the FREE Quick Start Guide to Teaching about the Orchestra here!

10 Reasons to Study Art and the Great Artists

“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” So goes an old saying, for each person on this earth has his or her own interpretation of what is beautiful, what is good art, and what one likes. What you consider to be meaningful art, I may not, but as educators of our children, it is important to expose our children to formal art and the Great Artists. (Of course, our opinions may also vary as to who the Great Artists really are, but there are generally accepted famous and influential artists whose work and lives are worthy of study.) So why should we study art and the Great Artists?

10 Reasons to study art and Great Artists:

1. It fulfills a human need to enjoy God and beauty . God is the Creator and author of creativity and beauty. Is not God an artist? As we study his creation (a form of art we call science), we get to know more about God and thus glorify Him as Creator. Man has long desired to capture the beauty of creation in pictures too, and thus we as humans, who are made in God’s image, desire to imitate his creative skills. Not all of us are as skilled in producing art, so we can appreciate the art of others, who are mere imitators of God the Creator and Artist.

2. The more one understands something, the more one appreciates it . I first heard this idea in my 10 th grade humanities class where we studied art amongst other things. It was my first exposure to studying art, and I can’t say I was too impressed with Cezanne’s paintings of still life. (Note: Children who are exposed to art early also develop appreciation more easily than teenagers.) My father had some art of John Constable and Monet on the walls in our home, but I hadn’t studied these artists or what they might have been trying to express before. With exposure to the artists’ stories and intentions, I began to enjoy or at least appreciate the art and what went into a painting. As a musician, I have also found that the pieces I spent hours practicing and performing are the ones I have the greatest appreciation and love for.

3. Art tells a story and is a means of communication . We are drawn to stories. We become curious about the subjects of paintings or why there is a giant sculpture of parts of farm equipment in the park. This leads to the next two reasons.

4. We learn history and culture . Through art study, we connect with others across centuries and cultures, especially when we pair art study with history. For example, pre-Renaissance European art is mostly church art – flat expressionless icons – because after the fall of Rome when the barbarian hordes destroyed most of the art of Rome, the Catholic Church was the main power and influence in the Middle Ages and so “controlled” art. Later, during the Renaissance, people developed humanistic ideas and became interested in studying and drawing the human body so that nudity is a regular part of art of this period. The historical context helps one to understand the subjects and whys of the art works of the time. Also, while I am not a lover of Picasso, when I understood that his famous painting Guernica was a response to a horrific slaughter of citizens in a Spanish town by the Nazis in WWII, the black, white and grey colors and disjointed style of Cubism actually seem a fitting expression of this topic.

5. We discern world view . Rembrandt grew up at the same time (early 1600s) as the pilgrims were living in Leiden, Holland, and Christian faith was an important aspect of many issues of the time. Thus, his paintings are realistic and one of his favorite subjects was Bible stories. Picasso, on the other hand, had no allegiance to faith in God and lived all the pleasures of the flesh, being a womanizer, for example. His world view was self-centered and anti-God and so we see this in his confused, distorted art works of Cubism and Surrealism. Children can observe these art works and see the results of world view, and so develop discernment.

6. It helps us develop critical thinking through skills of observation, interpretation, and criticism . Taking time to observe shapes, colors, styles, etc. is a basic skill children develop – remember the Spot the Difference pictures found in children’s books? The next step is to interpret what we see – again go back to the reasons #3 (In art study, we learn history and culture) and #4 (In studying art, we discern worldview.) Then we can criticize and form opinions. Criticizing art and forming opinions about it help to develop the critical thinking needed for bigger life choices, decisions and opinions.

7. It teaches concrete and abstract thought . Some art is very realistic while other art shows impressions of a view (think Impressionism and Monet’s paintings of the Houses of Parliament in London in the fog) or many angles of the same object at the same time (think Surrealism and Picasso’s view of a woman from many angles). Exposure to a wide variety of art can then help us interpret reality but also show that there are abstract concepts.

8. We have become a visual culture, so knowledge of graphic symbolism is helpful to navigate marketing logos . We need tools to respond to imagery, so the critical thinking skills and understanding of concrete and abstract thought (reasons #6 and #7) are essential in not giving in to every marketing slogan and symbol.

9. It promotes emotional well-being . Taking time to study art and music or visit museums and attend concerts means one is involved with life and the world around. Two recent studies show that being engaged and enthusiastic about the arts preserves a sense of purpose in life and hence emotional well-being for adults.* For students, regular field trips to museums or concerts promote positive engagement in school and less disciplinary problems because school is not considered boring.**

10. It develops the brain and keeps it active . Students who attended arts field trips made more academic gains and scored better on standardized tests.** Adults who participate in the arts or visit museums show less cognitive decline.*** Again, art engages our brains and promote purpose and involvement in life.

Art is a fundamental human expression as we imitate God the Creator and enriches our lives as we enjoy God and beauty. Through art we learn people’s stories, history, culture, world view, discernment, and critical thinking. We enjoy emotional well-being and purpose and keep our brains active. The more we study and understand art, the more we will appreciate it!

* The art of life and death: 14 year follow-up analyses of associations between arts engagement and mortality in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing

** University of Arkansas Researchers Find Social-Emotional and Academic Benefits from K-12 Arts Field Trips

*** Staying Engaged: Health Patterns of Older Americans Who Participate in the Arts

Do you want to dig deeper into art studies? Are you not sure where to start? Check out The Artist Detective unit studies or full course.

Jus’ Classical is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. You can help support Jus’ Classical in keeping resources free when you purchase anything through our link to Amazon.

For adults:

*For those concerned about violating the 2nd Commandment, the above books may have a few infractions.

Jus’ Classical Artist Biographies:

Rembrandt Biography for Kids

Thomas Gainsborough Biography for Kids

Edgar Degas Biography for Kids

Claude Monet Biography for Kids

Berthe Morisot Biography for Kids

Vincent van gogh biography for kids, similar posts.

12 Ways Drawing Grows the Brain and Helps Students Academically

As homeschooling parents, we might not give much thought to the study of art, the benefits of drawing, and teaching our children to draw when we are first researching our homeschool methods and which curriculum to use. “Reading, writing and ‘rithmetic – that’s the foundation,” we think. It is true that reading, writing and ‘rithmetic are an extremely important basis of learning, but the arts are also essential parts of education and of being human. In fact, there are many benefits of learning to draw (as well as of studying music appreciation and art appreciation and of learning to play…

Bonjour! I am Berthe Morisot, and I am a woman painter! This is the Berthe Morisot biography for kids! I was born in and always lived in France. When I was 16, my mother paid for me to take art lessons… …but I was barred from the famous art school because I am a female, not a male. They only wanted male students. But I often went to the Louvre – you know, the famous museum in Paris – to copy the Old Masters. Perhaps you’ve heard of some of the Old Masters? You know, like Giotto, …Ghiberti, …Fra Angelico,…

10 Reasons to Study the Orchestra, Composers and Music Appreciation

Music appreciation means that everyone appreciates music in some form. But many parents are hesitant to have their children study formal music appreciation – that is, the orchestra, composers and classical music – because they think their child is not interested in this kind of music. Certainly, classical music offers more depth than your regular country or pop song, so it can take a little longer to understand and appreciate it. Also, many pieces – like symphonies – are as long as 45 minutes, so attention span can be an issue. However, when children are exposed to all kinds of…

How to Recover from Homeschool Burnout

Are you experiencing homeschool burnout? It is a real problem. While a lot of homeschool moms (and public school moms too for that matter) may feel a real lull in the school year in January and February and wish schooling could be done for the year, homeschool burnout is a deeper issue. If you are an exhausted homeschooling mom, here are tips for how to recover from homeschool burnout so you can thrive, not just survive! My Road to Homeschool Burnout A few years ago, I had been homeschooling for eight years – one on my own and seven involved…

Hello, my name is Vincent van Gogh. I am a Post-Impressionist painter, and I’d like to tell you my story. This is the Vincent van Gogh biography for kids. I was born in Groot Zundert, Netherlands in 1853. My father was a pastor of a Dutch Reformed Church, so I learned the Bible growing up, but even from my youth, I was often depressed and suffered from a mood disorder. I did not study art formally while growing up, and by age 16, I went to work in an art dealership in The Hague, a city in the south of…

Why Participate in Classical Conversations

I discovered Classical Conversations (CC) when my friend’s daughter sang a few skip counting and history songs to me. “Where can I find those great skip counting songs?” I asked. As I looked into Classical Conversations, I loved that you can find a song to learn anything and actually memorize meaningful information! But it is the depth of the program that has kept me participating and growing along with my children. Why Participate in Classical Conversations Classical Conversations because it is a Christian homeschool community which utilizes the classical model. Their byline is classical Christian community: classical means how we…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Why Is Art Important? – The Value of Creative Expression

The importance of art is an important topic and has been debated for many years. Some might think art is not as important as other disciplines like science or technology. Some might ask what art is able to offer the world in terms of evolution in culture and society, or perhaps how can art change us and the world. This article aims to explore these weighty questions and more. So, why is art important to our culture? Let us take a look.

Table of Contents

- 1.1 The Definition of Art

- 1.2 The Types and Genres of Art

- 2.1 Art Is a Universal Language

- 2.2 Art Allows for Self-Expression

- 2.3 Art Keeps Track of History and Culture

- 2.4 Art Assists in Education and Human Development

- 2.5 Art Adds Beauty for Art’s Sake

- 2.6 Art Is Socially and Financially Rewarding

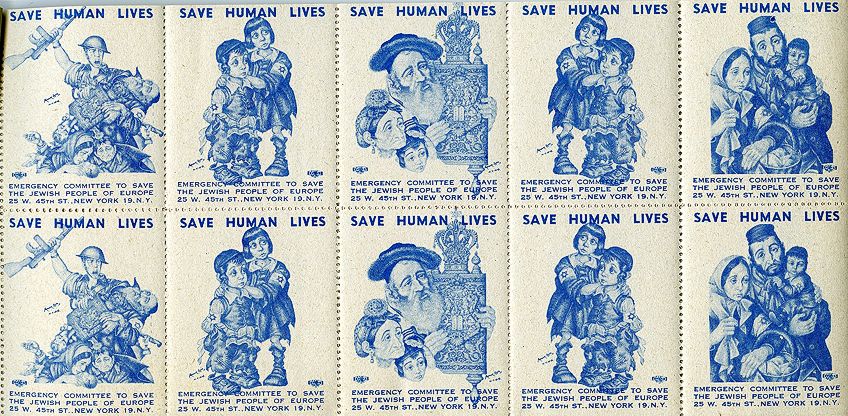

- 2.7 Art Is a Powerful (Political) Tool

- 3 Art Will Always Be There

- 4.1 What Is the Importance of Arts?

- 4.2 Why Is Art Important to Culture?

- 4.3 What Are the Different Types of Art?

- 4.4 What Is the Definition of Art?

What Is Art?

There is no logical answer when we ponder the importance of arts. It is, instead, molded by centuries upon centuries of creation and philosophical ideas and concepts. These not only shaped and informed the way people did things, but they inspired people to do things and live certain ways.

We could even go so far as to say the importance of art is borne from the very act of making art. In other words, it is formulated from abstract ideas, which then turn into the action of creating something (designated as “art”, although this is also a contested topic). This then evokes an impetus or movement within the human individual.

This impetus or movement can be anything from stirred up emotions, crying, feeling inspired, education, the sheer pleasure of aesthetics, or the simple convenience of functional household items – as we said earlier, the importance of art does not have a logical answer.

Before we go deeper into this question and concept, we need some context. Below, we look at some definitions of art to help shape our understanding of art and what it is for us as humans, thus allowing us to better understand its importance.

The Definition of Art

Simply put, the definition of the word “art” originates from the Latin ars or artem , which means “skill”, “craft”, “work of art”, among other similar descriptions. According to Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary, the word has various meanings; art may be a “skill acquired by experience, study, or observation”, a “branch of learning”, “an occupation requiring knowledge or skill”, or “the conscious use of skill and creative imagination especially in the production of aesthetic objects”.

We might also tend to think of art in terms of the latter definition provided above, “the conscious use of skill” in the “production of aesthetic objects”. However, does art only serve aesthetic purposes? That will also depend on what art means to us personally, and not how it is collectively defined. If a painting done with great skill is considered to be art, would a piece of furniture that is also made with great skill receive the same label as being art?

Thus, art is defined by our very own perceptions.

Art has also been molded by different definitions throughout history. When we look at it during the Classical or Renaissance periods , it was very much defined by a set of rules, especially through the various art academies in the major European regions like Italy (Academy and Company for the Arts of Drawing in Florence), France (French Academy of Fine Arts), and England (Royal Academy of Arts in London).

In other words, art had an academic component to it so as to distinguish artists from craftsmen.

The defining factor has always been between art for art’s sake , art for aesthetic purposes, and art that serves a purpose or a function, which is also referred to as “utilitarianism”. It was during the Classical and Renaissance periods that art was defined according to these various predetermined rules, but that leaves us with the question of whether these so-called rules are able to illustrate the deeper meaning of what art is?

If we move forward in time to the 20 th century and the more modern periods of art history, we find ourselves amidst a whole new art world. People have changed considerably between now and the Renaissance era, but we can count on art to be like a trusted friend, reflecting and expressing what is inherent in the cultures and people of the time.

During the 20 th century, art was not confined to rules like perspective, symmetry, religious subject matter, or only certain types of media like oil paints . Art was freed, so to say, and we see the definition of it changing (literally) in front of our very own eyes over a variety of canvases and objects. Art movements like Cubism , Fauvism, Dadaism, and Surrealism, among others, facilitated this newfound freedom in art.

Artists no longer subscribed to a set of rules and created art from a more subjective vantage point.

Additionally, more resources became available beyond only paint, and artists were able to explore new methods and techniques previously not available. This undoubtedly changed the preconceived notions of what art was. Art became commercialized, aestheticized, and devoid of the traditional Classical meaning from before. We can see this in other art movements like Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism, among others.

The Types and Genres of Art

There are also different types and genres of art, and all have had their own evolution in terms of being classified as art. These are the fine arts, consisting of painting, drawing, sculpting, and printmaking; applied arts like architecture; as well as different forms of design such as interior, graphic, and fashion design, which give day-to-day objects aesthetic value.

Other types of art include more decorative or ornamental pieces like ceramics, pottery, jewelry, mosaics, metalwork, woodwork, and fabrics like textiles. Performance arts involve theater and drama, music, and other forms of movement-based modalities like dancing, for example. Lastly, Plastic arts include works made with different materials that are pliable and able to be formed into the subject matter, thus becoming a more hands-on approach with three-dimensional interaction.

Top Reasons for the Importance of Art

Now that we have a reasonable understanding of what art is, and a definition that is ironically undefinable due to the ever-evolving and fluid nature of art, we can look at how the art that we have come to understand is important to culture and society. Below, we will outline some of the top reasons for the importance of art.

Art Is a Universal Language

Art does not need to explain in words how someone feels – it only shows. Almost anyone can create something that conveys a message on a personal or public level, whether it is political, social, cultural, historical, religious, or completely void of any message or purpose. Art becomes a universal language for all of us to tell our stories; it is the ultimate storyteller.

We can tell our stories through paintings, songs, poetry, and many other modalities.

Art connects us with others too. Whenever we view a specific artwork, which was painted by a person with a particular idea in mind, the viewer will feel or think a certain way, which is informed by the artwork (and artist’s) message. As a result, art becomes a universal language used to speak, paint, perform, or build that goes beyond different cultures, religions, ethnicities, or languages. It touches the deepest aspects of being human, which is something we all share.

Art Allows for Self-Expression

Touching on the above point, art touches the deepest aspects of being human and allows us to express these deeper aspects when words fail us. Art becomes like a best friend, giving us the freedom and space to be creative and explore our talents, gifts, and abilities. It can also help us when we need to express difficult emotions and feelings or when we need mental clarity – it gives us an outlet.

Art is widely utilized as a therapeutic tool for many people and is an important vehicle to maintain mental and emotional health. Art also allows us to create something new that will add value to the lives of others. Consistently expressing ourselves through a chosen art modality will also enable us to become more proficient and disciplined in our skills.

Art Keeps Track of History and Culture

We might wonder, why is art important to culture? As a universal language and an expression of our deepest human nature, art has always been the go-to to keep track of everyday events, almost like a visual diary. From the geometric motifs and animals found in early prehistoric cave paintings to portrait paintings from the Renaissance, every artwork is a small window into the ways of life of people from various periods in history. Art connects us with our ancestors and lineage.

When we find different artifacts from all over the world, we are shown how different cultures lived thousands of years ago. We can keep track of our current cultural trends and learn from past societal challenges. We can draw inspiration from past art and artifacts and in turn, create new forms of art.

Art is both timeless and a testament to the different times in our history.

Art Assists in Education and Human Development

Art helps with human development in terms of learning and understanding difficult concepts, as it accesses different parts of the human brain. It allows people to problem-solve as well as make more complex concepts easier to understand by providing a visual format instead of just words or numbers. Other areas that art assists learners in (range from children to adults) are the development of motor skills, critical thinking, creativity, social skills, as well as the ability to think from different perspectives.

Art subjects will also help students improve on other subjects like maths or science. Various research states the positive effects art has on students in public schools – it increases discipline and attendance and decreases the level of unruly behavior.

According to resources and questions asked to students about how art benefits them, they reported that they look forward to their art lesson more than all their other lessons during their school day. Additionally, others dislike the structured format of their school days, and art allows for more creativity and expression away from all the rules. It makes students feel free to do and be themselves.

Art Adds Beauty for Art’s Sake

Art is versatile. Not only can it help us in terms of more complex emotional and mental challenges and enhance our well-being, but it can also simply add beauty to our lives. It can be used in numerous ways to make spaces and areas visually appealing.

When we look at something beautiful, we immediately feel better. A piece of art in a room or office can either create a sense of calm and peace or a sense of movement and dynamism.

Art can lift a space either through a painting on a wall, a piece of colorful furniture, a sculpture, an ornamental object, or even the whole building itself, as we see from so many examples in the world of architecture. Sometimes, art can be just for art’s sake.

Art Is Socially and Financially Rewarding

Art can be socially and financially rewarding in so many ways. It can become a profession where artists of varying modalities can earn an income doing what they love. In turn, it becomes part of the economy. If artists sell their works, whether in an art gallery, a park, or online, this will attract more people to their location. Thus, it could even become a beacon for improved tourism to a city or country.

The best examples are cities in Europe where there are numerous art galleries and architectural landmarks celebrating artists from different periods in art history, from Gothic cathedrals like the Notre Dame in Paris to the Vincent van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Art can also encourage people to do exercise by hiking up mountains to visit pre-historic rock art caves.

Art Is a Powerful (Political) Tool

Knowing that art is so versatile, that it can be our best friend and teacher, makes it a very powerful tool. The history of humankind gives us thousands of examples that show how art has been used in the hands of people who mean well and people who do not mean well.

Therefore, understanding the role of art in our lives as a powerful tool gives us a strong indication of its importance.

Art is also used as a political medium. Examples include memorials to celebrate significant changemakers in our history, and conveying powerful messages to society in the form of posters, banners, murals, and even graffiti. It has been used throughout history by those who have rebelled as well as those who created propaganda to show the world their intentions, as extreme as wanting to take over the world or disrupt existing regimes.

The Futurist art movement is an example of art combined with a group of men who sought to change the way of the future, informed by significant changes in society like the industrial revolution. It also became a mode of expression of the political stances of its members.

Other movements like Constructivism and Suprematism used art to convey socialist ideals, also referred to as Socialist Realism.

Other artists like Jacques-Louis David from the Neoclassical movement produced paintings influenced by political events; the subject matter also included themes like patriotism. Other artists include Pablo Picasso and his famous oil painting , Guernica (1937), which is a symbol and allegory intended to reach people with its message.

The above examples all illustrate to us that various wars, conflicts, and revolutions throughout history, notably World Wars I and II, have influenced both men and women to produce art that either celebrates or instigates changes in society. The power of art’s visual and symbolic impact has been able to convey and appeal to the masses.

Art Will Always Be There

The importance of art is an easy concept to understand because there are so many reasons that explain its benefits in our lives. We do not have to look too hard to determine its importance. We can also test it on our lives by the effects it has on how we feel and think when we engage with it as onlookers or as active participants – whether it is painting, sculpting, or standing in an art gallery.

What art continuously shows us is that it is a constant in our lives, our cultures, and the world. It has always been there to assist us in self-expression and telling our story in any way we want to. It has also given us glimpses of other cultures along the way.

Art is fluid and versatile, just like a piece of clay that can be molded into a beautiful bowl or a slab of marble carved into a statue. Art is also a powerful tool that can be used for the good of humanity good or as a political weapon.

Art is important because it gives us the power to mold and shape our lives and experiences. It allows us to respond to our circumstances on micro- and macroscopic levels, whether it is to appreciate beauty, enhance our wellbeing, delve deeper into the spiritual or metaphysical, celebrate changes, or to rebel and revolt.

Take a look at our purpose of art webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the importance of arts.

There are many reasons that explain the importance of art. It is a universal language because it crosses language and cultural barriers, making it a visual language that anyone can understand; it helps with self-expression and self-awareness because it acts as a vehicle wherein we can explore our emotions and thoughts; it is a record of past cultures and history; it helps with education and developing different skill sets; it can be financially rewarding, it can be a powerful political tool, and it adds beauty and ambiance to our lives and makes us feel good.

Why Is Art Important to Culture?

Art is important to culture because it can bridge the gap between different racial groups, religious groups, dialects, and ethnicities. It can express common values, virtues, and morals that we can all understand and feel. Art allows us to ask important questions about life and society. It allows reflection, it opens our hearts to empathy for others, as well as how we treat and relate to one another as human beings.

What Are the Different Types of Art?

There are many different types of art, including fine arts like painting, drawing, sculpture, and printmaking, as well as applied arts like architecture, design such as interior, graphic, and fashion. Other types of art include decorative arts like ceramics, pottery, jewelry, mosaics, metalwork, woodwork, and fabrics like textiles; performance arts like theater, music, dancing; and Plastic arts that work with different pliable materials.

What Is the Definition of Art?

The definition of the word “art” originates from the Latin ars or artem , which means “skill”, “craft”, and a “work of art”. The Merriam-Webster online dictionary offers several meanings, for example, art is a “skill acquired by experience, study, or observation”, it is a “branch of learning”, “an occupation requiring knowledge or skill”, or “the conscious use of skill and creative imagination especially in the production of aesthetic objects”.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20 th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Why Is Art Important? – The Value of Creative Expression.” Art in Context. July 26, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/why-is-art-important/

Meyer, I. (2021, 26 July). Why Is Art Important? – The Value of Creative Expression. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/why-is-art-important/

Meyer, Isabella. “Why Is Art Important? – The Value of Creative Expression.” Art in Context , July 26, 2021. https://artincontext.org/why-is-art-important/ .

Similar Posts

Texture in Art – Exploring the Element of Texture in Art

Types of Illustration – Functions and Styles of Visual Depiction

Land Art – Famous Earth Artists and the Ephemerality of Land Art

New Objectivity Art – Explore German Post-Expressionism

Renaissance Facts – A Brief Overview of Renaissance History

Islamic Art – A Deep Dive into the Gilded World of Islamic Art

One comment.

It’s great that you talked about how there are various kinds and genres of art. I was reading an art book earlier and it was quite interesting to learn more about the history of art. I also learned other things, like the existence of online american indian art auctions.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Most Famous Artists and Artworks

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors…in all of history!

MOST FAMOUS ARTISTS AND ARTWORKS

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors!

How to analyze an artwork: a step-by-step guide

Last Updated on August 16, 2023