- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument . Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

Related Words and Phrases

Bottom_desktop desktop:[300x250].

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

List of 50 "In Conclusion" Synonyms—Write Better with ProWritingAid

Alex Simmonds

Table of Contents

Why is it wrong to use "in conclusion" when writing a conclusion, what can i use instead of "in conclusion" for an essay, what are some synonyms for "in conclusion" in formal writing, what are some synonyms for "in conclusion" in informal writing, what is another word for "in conclusion", what should a conclusion do in an article or paper.

The final paragraphs of any paper can be extremely difficult to get right, and yet they are probably the most important. They offer you a chance to summarize the points you have made into a neat package and leave a good impression on the reader.

Many people choose to start the last paragraph with the phrase in conclusion , but this has its downsides.

Firstly, you should only use it once. Any more than that and your essay will sound horribly repetitive. Secondly, there is the question of whether you should even use the phrase at all?

Though it’s okay to use in conclusion in a speech or presentation, when writing an essay it comes across as stating the obvious. The phrase will come across as a bit unnecessary or "on the nose."

Its use in an essay is clichéd, and there are far cleaner and more elegant ways of indicating that you are going to be concluding the paper. Using in conclusion might even irritate and alienate your audience or readers.

Thankfully, there are hundreds of synonyms available in the English language which do a much better (and much more subtle) job of drawing a piece of writing to a close.

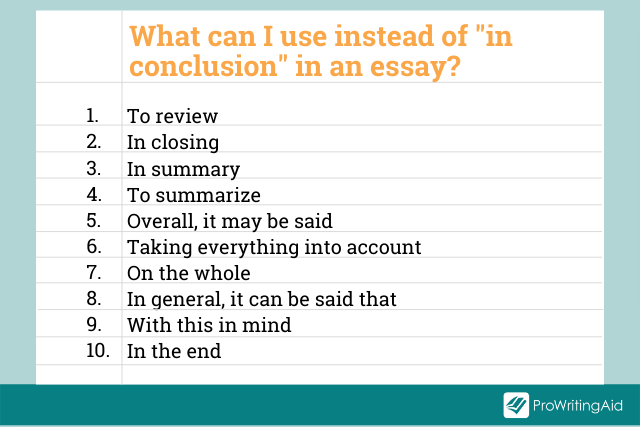

The key is to choose ones which suit the tone of the paper. Here we will look at both formal options for an essay or academic paper, and informal options for light-hearted, low key writing, or speeches.

If you are writing an academic essay, a white paper, a business paper, or any other formal text, you will want to use formal transitional expressions that successfully work as synonyms for in conclusion .

The following are some suggestions you could use:

As has been demonstrated

A simple way of concluding all your points and summarizing everything you have said is to confidently state that those points have convincingly proven your case:

As the research has demonstrated , kids really do love chocolate.

As all the above points have demonstrated , Dan Brown really was the most technically gifted writer of the 20th Century.

As has been demonstrated in this paper , the side-effects of the vaccine are mild in comparison to the consequences of the virus.

As has been shown

This is another way of saying as has been demonstrated , but perhaps less scientific and more literary. As has been shown would work well in literature, history, or philosophy essays.

For example:

As has been shown above , the First World War and industrialization were the drivers for a new way of seeing the world, reflected in Pound’s poetry.

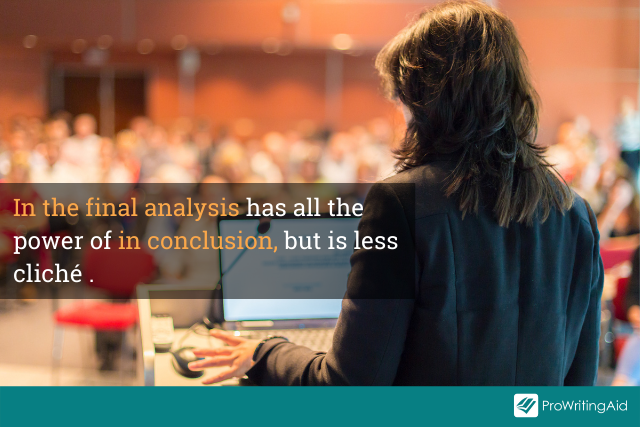

In the final analysis

This is a great expression to use in your conclusion, since it’s almost as blunt as in conclusion , but is a more refined and far less clichéd way of starting the concluding paragraph.

Once you have finished your argument and started drawing things to a close, using in the final analysis allows you to tail nicely into your last summation.

In the final analysis , there can be little doubt that Transformers: Dark of the Moon represents a low point in the history of cinema.

Along with let’s review , this is short and blunt way of announcing that you intend to recap the points you have made so far, rather than actually drawing a conclusion.

It definitely works best when presenting or reading out a speech, but less well in an essay or paper.

However, it does work effectively in a scientific paper or if you wish to recap a long train of thought, argument, or sequence before getting to the final concluding lines.

To review , of the two groups of senior citizens, one was given a placebo and the other a large dose of amphetamines.

Another phrase you could consider is in closing . This is probably better when speaking or presenting because of how double-edged it is. It still has an in conclusion element to it, but arguably it could also work well when drawing an academic or scientific paper to a conclusion.

For example, it is particularly useful in scientific or business papers where you want to sum up your points, and then even have a call to action:

In closing then, it is clear that as a society, we all need to carefully monitor our consumption of gummy bears.

Or in an academic paper, it offers a slightly less blunt way to begin a paragraph:

In closing , how do we tie all these different elements of Ballard’s writing together?

Perhaps the most similar expression to in conclusion is in summary . In summary offers a clear indication to the reader that you are going to restate the main points of your paper and draw a conclusion from those points:

In summary , Existentialism is the only philosophy that has any real validity in the 21st century.

In summary , we believe that by switching to a subscription model...

On top of those previously mentioned, here are some other phrases that you can use as an alternative to in conclusion :

To summarize

Overall, it may be said

Taking everything into account

On the whole

In general, it can be said that

With this in mind

Considering all this

Everything considered

As a final observation

Considering all of the facts

For the most part

In light of these facts

When it comes to finishing up a speech, a light-hearted paper, blog post, or magazine article, there are a couple of informal phrases you can use rather than in conclusion :

In a nutshell

The phrase in a nutshell is extremely informal and can be used both in speech and in writing. However, it should never be used in academic or formal writing.

It could probably be used in informal business presentations, to let the audience know that you are summing up in a light-hearted manner:

In a nutshell , our new formula Pro Jazzinol shampoo does the same as our old shampoo, but we get to charge 20% more for it!

You can also use it if you want to get straight to the point at the end of a speech or article, without any fluff:

In a nutshell , our new SocialShocka app does what it says on the tin—gives you an electric shock every time you try to access your social media!

At the end of the day

This is a pretty useful expression if you want to informally conclude an argument, having made all your points. It basically means in the final reckoning or the main thing to consider is , but said in a more conversational manner:

At the end of the day , he will never make the national team, but will make a good living as a professional.

At the end of the day , the former President was never destined to unite the country…

Long story short

Another informal option when replacing in conclusion is to opt for to make a long story short —sometimes shortened to long story short .

Again, this is not one you would use when writing an academic or formal paper, as it is much too conversational. It’s a phrase that is far better suited to telling a joke or story to your friends:

Long story short , Billy has only gone and started his own religion!

Would you ever use it in writing? Probably not, except for at the end of friendly, low-key presentations:

Long story short , our conclusion is that you are spending far too much money on after work company bowling trips.

And possibly at the end of an offbeat magazine article or blog post:

Long story short , Henry VIII was a great king—not so great a husband though!

Other "In Conclusion" Synonyms for Informal Writing

You can use any of the synonyms in this article when writing informally, but these are particularly useful when you want your writing to sound conversational:

By and large

On a final note

Last but not least

For all intents and purposes

The bottom line is

To put it bluntly

To wrap things up

To come to the point

To wind things up

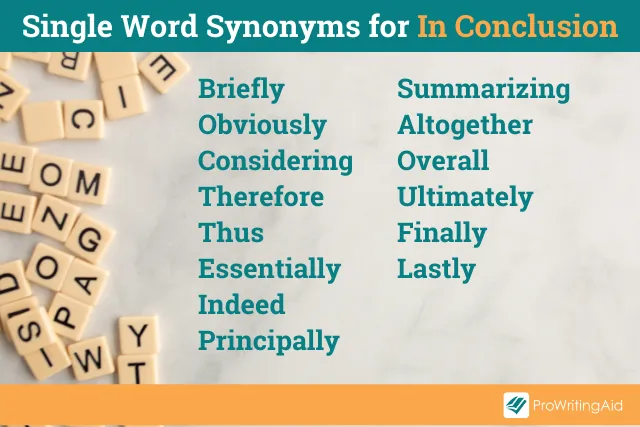

Instead of opting for one of the above expressions or idioms, there are several different singular transition words you can use instead. Here are a couple of examples:

The perfect word to tell the reader you are reaching the end of your argument. Lastly is an adverb that means "at the end" or "in summary." It is best used when you are beginning your conclusion:

Lastly , with all the previous points in mind, there is the question of why Philip K Dick was so fascinated with alternate history?

But can also be used at the very end of your conclusion too:

Lastly then, we are left with Eliot’s own words on his inspiration for "The Waste Land."

Finally does exactly the same job as lastly . It lets the reader know that you are at the final point of your argument or are about to draw your conclusion:

Finally , we can see from all the previous points that...

Another word that can be used at beginning of the conclusion is the adverb ultimately . Meaning "in the end" or "at the end of the day," it can be used as a conclusion to both informal and formal papers or articles:

Ultimately , it comes down to whether one takes an Old Testament view of capital punishment or...

It can also be used in more survey, scientific, or charity appeal style articles as a call to action of some sort:

Ultimately , we will all need to put some thought into our own carbon footprints over the next couple of years.

A good word to conclude a scientific, or survey style paper is overall . It can be used when discussing the points, arguments or results that have been outlined in the paper up until that point.

Thus, you can say:

Overall , our survey showed that most people believe you should spread the cream before you add the jam, when eating scones.

Other Transition Words to Replace "In Conclusion"

Here are a few transition word alternatives to add to your arsenal:

Considering

Essentially

Principally

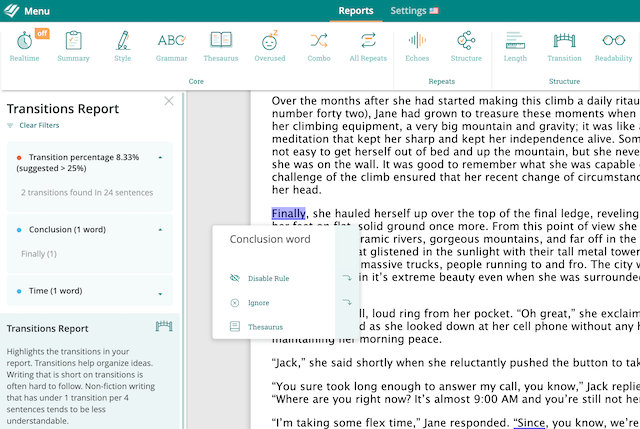

Summarizing

Pro tip: You should use transition words throughout your essay, paper, or article to guide your reader through your ideas towards your conclusion. ProWritingAid’s Transitions Report tells you how many transition words you’ve used throughout your document so you can make sure you’re supporting your readers’ understanding.

It’ll also tell you what type of transitions you’ve used. If there are no conclusion words in your writing, consider using one of the synonyms from this article.

Sign up for a free ProWritingAid account to try the Transitions Report.

One of the most effective ways of finishing up a piece of writing is to ask a question, or return to the question that was asked at the beginning of the paper using. This can be achieved using how , what , why , or who .

This is sometimes referred to as the "so what?" question. This takes all your points and moves your writing (and your reader) back to the broader context, and gets the reader to ask, why are these points important? Your conclusion should answer the question "so what?" .

To answer that, you circle back to the main concept or driving force of the essay / paper (usually found in the title) and tie it together with the points you have made, in a final, elegant few sentences:

How, then, is Kafka’s writing modernist in outlook?

Why should we consider Dickens’ work from a feminist perspective?

What, then , was Blake referring to, when he spoke of mind forged manacles?

In Conclusion

There are plenty of alternatives for drawing an effective and elegant close to your arguments, rather than simply stating in conclusion .

Whether you ask a question or opt for a transition expression or a single transition word, just taking the time to choose the right synonyms will make all the difference to what is, essentially, the most important part of your paper.

Want to improve your essay writing skills?

Use prowritingaid.

Are your teachers always pulling you up on the same errors? Maybe you’re losing clarity by writing overly long sentences or using the passive voice too much.

ProWritingAid helps you catch these issues in your essay before you submit it.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Alex Simmonds is a freelance copywriter based in the UK and has been using words to help people sell things for over 20 years. He has an MA in English Lit and has been struggling to write a novel for most of the last decade. He can be found at alexsimmonds.co.uk.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Academic writing

- Transition Words & Phrases | List & Examples

Transition Words & Phrases | List & Examples

Published on May 29, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 23, 2023.

Transition words and phrases (also called linking words, connecting words, or transitional words) are used to link together different ideas in your text. They help the reader to follow your arguments by expressing the relationships between different sentences or parts of a sentence.

The proposed solution to the problem did not work. Therefore , we attempted a second solution. However , this solution was also unsuccessful.

For clear writing, it’s essential to understand the meaning of transition words and use them correctly.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

When and how to use transition words, types and examples of transition words, common mistakes with transition words, other interesting articles.

Transition words commonly appear at the start of a new sentence or clause (followed by a comma ), serving to express how this clause relates to the previous one.

Transition words can also appear in the middle of a clause. It’s important to place them correctly to convey the meaning you intend.

Example text with and without transition words

The text below describes all the events it needs to, but it does not use any transition words to connect them. Because of this, it’s not clear exactly how these different events are related or what point the author is making by telling us about them.

If we add some transition words at appropriate moments, the text reads more smoothly and the relationship among the events described becomes clearer.

Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Consequently , France and the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. The Soviet Union initially worked with Germany in order to partition Poland. However , Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941.

Don’t overuse transition words

While transition words are essential to clear writing, it’s possible to use too many of them. Consider the following example, in which the overuse of linking words slows down the text and makes it feel repetitive.

In this case the best way to fix the problem is to simplify the text so that fewer linking words are needed.

The key to using transition words effectively is striking the right balance. It is difficult to follow the logic of a text with no transition words, but a text where every sentence begins with a transition word can feel over-explained.

Check for common mistakes

Use the best grammar checker available to check for common mistakes in your text.

Fix mistakes for free

There are four main types of transition word: additive, adversative, causal, and sequential. Within each category, words are divided into several more specific functions.

Remember that transition words with similar meanings are not necessarily interchangeable. It’s important to understand the meaning of all the transition words you use. If unsure, consult a dictionary to find the precise definition.

Additive transition words

Additive transition words introduce new information or examples. They can be used to expand upon, compare with, or clarify the preceding text.

Adversative transition words

Adversative transition words always signal a contrast of some kind. They can be used to introduce information that disagrees or contrasts with the preceding text.

Causal transition words

Causal transition words are used to describe cause and effect. They can be used to express purpose, consequence, and condition.

Sequential transition words

Sequential transition words indicate a sequence, whether it’s the order in which events occurred chronologically or the order you’re presenting them in your text. They can be used for signposting in academic texts.

Transition words are often used incorrectly. Make sure you understand the proper usage of transition words and phrases, and remember that words with similar meanings don’t necessarily work the same way grammatically.

Misused transition words can make your writing unclear or illogical. Your audience will be easily lost if you misrepresent the connections between your sentences and ideas.

Confused use of therefore

“Therefore” and similar cause-and-effect words are used to state that something is the result of, or follows logically from, the previous. Make sure not to use these words in a way that implies illogical connections.

- We asked participants to rate their satisfaction with their work from 1 to 10. Therefore , the average satisfaction among participants was 7.5.

The use of “therefore” in this example is illogical: it suggests that the result of 7.5 follows logically from the question being asked, when in fact many other results were possible. To fix this, we simply remove the word “therefore.”

- We asked participants to rate their satisfaction with their work from 1 to 10. The average satisfaction among participants was 7.5.

Starting a sentence with also , and , or so

While the words “also,” “and,” and “so” are used in academic writing, they are considered too informal when used at the start of a sentence.

- Also , a second round of testing was carried out.

To fix this issue, we can either move the transition word to a different point in the sentence or use a more formal alternative.

- A second round of testing was also carried out.

- Additionally , a second round of testing was carried out.

Transition words creating sentence fragments

Words like “although” and “because” are called subordinating conjunctions . This means that they introduce clauses which cannot stand on their own. A clause introduced by one of these words should always follow or be followed by another clause in the same sentence.

The second sentence in this example is a fragment, because it consists only of the “although” clause.

- Smith (2015) argues that the period should be reassessed. Although other researchers disagree.

We can fix this in two different ways. One option is to combine the two sentences into one using a comma. The other option is to use a different transition word that does not create this problem, like “however.”

- Smith (2015) argues that the period should be reassessed, although other researchers disagree.

- Smith (2015) argues that the period should be reassessed. However , other researchers disagree.

And vs. as well as

Students often use the phrase “ as well as ” in place of “and,” but its usage is slightly different. Using “and” suggests that the things you’re listing are of equal importance, while “as well as” introduces additional information that is less important.

- Chapter 1 discusses some background information on Woolf, as well as presenting my analysis of To the Lighthouse .

In this example, the analysis is more important than the background information. To fix this mistake, we can use “and,” or we can change the order of the sentence so that the most important information comes first. Note that we add a comma before “as well as” but not before “and.”

- Chapter 1 discusses some background information on Woolf and presents my analysis of To the Lighthouse .

- Chapter 1 presents my analysis of To the Lighthouse , as well as discussing some background information on Woolf.

Note that in fixed phrases like “both x and y ,” you must use “and,” not “as well as.”

- Both my results as well as my interpretations are presented below.

- Both my results and my interpretations are presented below.

Use of and/or

The combination of transition words “and/or” should generally be avoided in academic writing. It makes your text look messy and is usually unnecessary to your meaning.

First consider whether you really do mean “and/or” and not just “and” or “or.” If you are certain that you need both, it’s best to separate them to make your meaning as clear as possible.

- Participants were asked whether they used the bus and/or the train.

- Participants were asked whether they used the bus, the train, or both.

Archaic transition words

Words like “hereby,” “therewith,” and most others formed by the combination of “here,” “there,” or “where” with a preposition are typically avoided in modern academic writing. Using them makes your writing feel old-fashioned and strained and can sometimes obscure your meaning.

- Poverty is best understood as a disease. Hereby , we not only see that it is hereditary, but acknowledge its devastating effects on a person’s health.

These words should usually be replaced with a more explicit phrasing expressing how the current statement relates to the preceding one.

- Poverty is best understood as a disease. Understanding it as such , we not only see that it is hereditary, but also acknowledge its devastating effects on a person’s health.

Using a paraphrasing tool for clear writing

With the use of certain tools, you can make your writing clear. One of these tools is a paraphrasing tool . One thing the tool does is help your sentences make more sense. It has different modes where it checks how your text can be improved. For example, automatically adding transition words where needed.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or writing rules make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Academic Writing

- Avoiding repetition

- Effective headings

- Passive voice

- Taboo words

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, August 23). Transition Words & Phrases | List & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 20, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-writing/transition-words/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, using conjunctions | definition, rules & examples, transition sentences | tips & examples for clear writing, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

Vocabulary Tips: Alternatives to “But” for Academic Writing

4-minute read

- 6th November 2019

You’ll use some terms frequently in your written work. “But” is one of these words: the twenty-second most common word in English, in fact! Consequently, you shouldn’t worry too much about the repetition of “but” in your writing . But if you find yourself using it in every other sentence, you might want to try a few alternatives. How about the following?

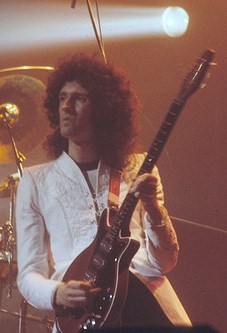

Other Conjunctions

“But” is a conjunction (i.e., a linking word) used to introduce a contrast. For example, we could use it in a sentence expressing contrasting opinions about Queen guitarist Brian May and his hairdo:

I like Brian May, but I find his hair ridiculous.

One option to reduce repetition of “but” in writing is to use the word “yet:”

I like Brian May, yet I find his hair ridiculous.

“Yet” can often replace “but” in a sentence without changing anything else, as both are coordinating conjunctions that can introduce a contrast.

Alternatively, you could use one of these subordinating conjunctions :

- Although (e.g., I like Brian May, although I find his hair ridiculous .)

- Though (e.g., I like Brian May, though I find his hair ridiculous. )

- Even though (e.g., I like Brian May, even though I find his hair ridiculous. )

As subordinating conjunctions, these terms can also be used at the start of a sentence. This isn’t the case with “but,” though:

Though I like Brian May, I find his hair ridiculous. – Correct

But I like Brian May, I find his hair ridiculous. – Incorrect

Other subordinating conjunctions used to introduce a contrast include “despite” and “whereas.” If you’re going to use “despite” in place of “but,” you may need to rephrase the sentence slightly. For instance:

Despite liking Brian May, I find his hair ridiculous.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

I like Brian May’s guitar solos, whereas I find his hair ridiculous.

How to Use “However”

One common replacement for “but” in academic writing is “however.” But we use this adverb to show a sentence contrasts with something previously said. As such, rather than connecting two parts of a sentence, it should only be used after a semicolon or in a new sentence:

I like Brian May’s guitar solos. However , I find his hair ridiculous.

I like Brian May’s guitar solos; however , I find his hair ridiculous.

“However” can be used mid-sentence, separated by commas. Even then, though, you should separate the sentence in which it appears from the one with which it is being contrasted. For instance:

I like Brian May’s guitar solos. I do, however , find his hair ridiculous.

Here, again, the “however” sentence contrasts with the preceding one.

Other Adverbial Alternatives to “But”

Other contrasting adverbs and adverbial phrases can be used in similar ways to “however” above. Alternatives include:

- Conversely ( I like Brian May’s guitar solos. Conversely , I find his hair ridiculous. )

- Nevertheless ( I like Brian May; nevertheless , I find his hair ridiculous. )

- In contrast ( I like Brian May’s guitar solos. In contrast , I find his hair ridiculous. )

One popular phrase for introducing a contrast is “on the other hand.” In formal writing, though, this should always follow from “on the one hand:”

On the one hand , I like Brian May’s music, so I do admire him. On the other hand , his hairstyle is terrifying, so I do worry about him .

Finally, if you’re ever unsure which terms to use as alternatives to “but” in writing, having your document proofread by the experts can help.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

What is market research.

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

3-minute read

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

The 5 Best Ecommerce Website Design Tools

A visually appealing and user-friendly website is essential for success in today’s competitive ecommerce landscape....

The 7 Best Market Research Tools in 2024

Market research is the backbone of successful marketing strategies. To gain a competitive edge, businesses...

Google Patents: Tutorial and Guide

Google Patents is a valuable resource for anyone who wants to learn more about patents, whether...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Refine Your Final Word With 10 Alternatives To “In Conclusion”

- Alternatives To In Conclusion

Wrapping up a presentation or a paper can be deceptively difficult. It seems like it should be easy—after all, your goal is to summarize the ideas you’ve already presented and possibly make a call to action. You don’t have to find new information; you just have to share what you already know.

Here’s where it gets tricky, though. Oftentimes, it turns out that the hardest part about writing a good conclusion is avoiding repetition.

That’s where we can help, at least a little bit. When it comes to using a transition word or phrase to kick off your conclusion, the phrase in conclusion is frequently overused. It’s easy to understand why—it is straightforward. But there are far more interesting and attention-grabbing words and phrases you can use in your papers and speeches to signal that you have reached the end.

One of the simplest synonyms of in conclusion is in summary . This transition phrase signals that you are going to briefly state the main idea or conclusion of your research. Like in conclusion , it is formal enough to be used both when writing an academic paper and when giving a presentation.

- In summary, despite multiple experimental designs, the research remains inconclusive.

- In summary , there is currently unprecedented interest in our new products.

A less formal version of in summary is to sum up . While this phrase expresses the same idea, it's more commonly found in oral presentations rather than written papers in this use.

- To sum up, we have only begun to discover the possible applications of this finding.

let's review or to review

A conclusion doesn't simply review the main idea or argument of a presentation. In some cases, a conclusion includes a more complete assessment of the evidence presented. For example, in some cases, you might choose to briefly review the chain of logic of an argument to demonstrate how you reached your conclusion. In these instances, the expressions let's review or to review are good signposts.

The transition phrases let's review and to review are most often used in spoken presentations, not in written papers. Unlike the other examples we have looked at, let's review is a complete sentence on its own.

- Let's review. First, he tricked the guard. Then, he escaped out the front door.

- To review: we developed a special kind of soil, and then we planted the seeds in it.

A classy alternative to in conclusion , both in papers and presentations, is in closing . It is a somewhat formal expression, without being flowery. This transition phrase is especially useful for the last or penultimate sentence of a conclusion. It is a good way to signal that you are nearly at the bitter end of your essay or speech. A particularly common way to use in closing is to signal in an argumentative piece that you are about to give your call to action (what you want your audience to do).

- In closing, we should all do more to help save the rainforest.

- In closing, I urge all parties to consider alternative solutions such as the ones I have presented.

in a nutshell

The expression in a nutshell is a cute and informal metaphor used to indicate that you are about to give a short summary. (Imagine you're taking all of the information and shrinking it down so it can fit in a nutshell.) It's appropriate to use in a nutshell both in writing and in speeches, but it should be avoided in contexts where you're expected to use a serious, formal register .

- In a nutshell, the life of this artist was one of great triumph and great sadness.

- In a nutshell, the company spent too much money and failed to turn a profit.

The expression in a nutshell can also be used to signal you've reached the end of a summarized story or argument that you are relating orally, as in "That's the whole story, in a nutshell."

[To make a] long story short

Another informal expression that signals you're about to give a short summary is to make a long story short , sometimes abbreviated to simply long story short. The implication of this expression is that a lengthy saga has been cut down to just the most important facts. (Not uncommonly, long story short is used ironically to indicate that a story has, in fact, been far too long and detailed.)

Because it is so casual, long story short is most often found in presentations rather than written papers. Either the full expression or the shortened version are appropriate, as long as there isn't an expectation that you be formal with your language.

- Long story short, the explorers were never able to find the Northwest Passage.

- To make a long story short, our assessments have found that there is a large crack in the foundation.

If using a transitional expression doesn't appeal to you, and you would rather stick to a straightforward transition word, you have quite a few options. We are going to cover a couple of the transition words you may choose to use to signal you are wrapping up, either when giving a presentation or writing a paper.

The first term we are going to look at is ultimately . Ultimately is an adverb that means "in the end; at last; finally." Typically, you will want to use it in the first or last sentence of your conclusion. Like in closing , it is particularly effective at signaling a call to action.

- Ultimately, each and every single person has a responsibility to care about this issue.

- Ultimately, the army beat a hasty retreat and the war was over.

Another transition word that is good for conclusions is lastly , an adverb meaning "in conclusion; in the last place; finally." Lastly can be used in informational or argumentative essays or speeches. It is a way to signal that you are about to provide the last point in your summary or argument. The word lastly is most often used in the first or last sentence of a conclusion.

- Lastly, I would like to thank the members of the committee and all of you for being such a gracious audience.

- Lastly, it must be noted that the institution has not been able to address these many complaints adequately.

The word overall is particularly good for summing up an idea or argument as part of your conclusion. Meaning "covering or including everything," overall is a bit like a formal synonym for "in a nutshell."

Unlike the other examples we have looked at in this slideshow, it is not unusual for overall to be found at the end of a sentence, rather than only at the beginning.

- Overall, we were very pleased with the results of our experiment.

- The findings of our study indicate that there is a lot of dissatisfaction with internet providers overall.

asking questions

Using traditional language like the options we have outlined so far is not your only choice when it comes to crafting a strong conclusion. If you are writing an argumentative essay or speech, you might also choose to end with one or a short series of open-ended or leading questions. These function as a creative call to action and leave the audience thinking about the arguments you have made.

In many cases, these questions begin with a WH-word , such as who or what. The specifics will vary spending on the argument being made, but here are a few general examples:

- When it comes to keeping our oceans clean, shouldn't we be doing more?

- Who is ultimately responsible for these terrible mistakes?

on a final note

Before we wrap up, we want to leave you with one last alternative for in conclusion . The expression on a final note signals that you are about to give your final point or argument. On a final note is formal enough to be used both in writing and in speeches. In fact, it can be used in a speech as a natural way to transition to your final thank yous.

- On a final note, thank you for your time and attention.

- On a final note, you can find more synonyms for in conclusion here.

The next time you are working on a conclusion and find yourself stuck for inspiration, try out some of these expressions. After all, there is always more than one way to write an ending.

No matter how you wrap up your project, keep in mind there are some rules you don't always have to follow! Let's look at them here.

Ways To Say

Synonym of the day

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

Other Ways of Saying ‘Because’

- 2-minute read

- 16th December 2015

If English is not your first language , you may not know that there are lots of words that you can use instead of ‘because’. This is important, since using ‘because’ too often in your written work can make it seem stilted or repetitive.

By comparison, varying word choice can make your work easier to read and more engaging. Today, we’re going to share several synonyms for ‘because’ that will make your work look more academic .

Synonyms for ‘Because’

Let’s start with an example sentence:

Marjorie was angry because the moles kept digging up her garden.

Here , we could use several words and phrases instead of ‘ because ‘:

Marjorie was angry due to the moles that kept digging up her garden.

Marjorie was angry on account of the moles that were digging up her garden.

Notice that you need to adjust the sentence slightly to suit the alternative words used.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Other Options

Another way to get round the use of ‘because’ is to rearrange the sentence:

The way the moles kept digging up Marjorie’s garden made her very angry.

Here, we have reversed the elements of the sentence and used the word ‘made’ to indicate the relationship between Marjorie’s anger and the moles in her garden. This can be a good way of varying your sentence structure.

You could also try the following variations:

The moles dug up Marjorie’s garden, making her very angry.

The moles dug up Marjorie’s garden and made her very angry.

The moles dug up Marjorie’s garden, which made her very angry.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Get help from a language expert. Try our proofreading services for free.

4-minute read

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

3-minute read

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

The 5 Best Ecommerce Website Design Tools

A visually appealing and user-friendly website is essential for success in today’s competitive ecommerce landscape....

The 7 Best Market Research Tools in 2024

Market research is the backbone of successful marketing strategies. To gain a competitive edge, businesses...

Google Patents: Tutorial and Guide

Google Patents is a valuable resource for anyone who wants to learn more about patents, whether...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

12 Alternatives to “Firstly, Secondly, Thirdly” in an Essay

Essays are hard enough to get right without constantly worrying about introducing new points of discussion.

You might have tried using “firstly, secondly, thirdly” in an essay, but are there better alternatives out there?

This article will explore some synonyms to give you other ways to say “firstly, secondly, thirdly” in academic writing.

Can I Say “Firstly, Secondly, Thirdly”?

You can not say “firstly, secondly, thirdly” in academic writing. It sounds jarring to most readers, so you’re better off using “first, second, third” (removing the -ly suffix).

Technically, it is correct to say “firstly, secondly, thirdly.” You could even go on to say “fourthly” and “fifthly” when making further points. However, none of these words have a place in formal writing and essays.

Still, these examples will show you how to use all three of them:

Firstly , I would like to touch on why this is problematic behavior. Secondly , we need to discuss the solutions to make it better. Thirdly , I will finalize the discussion and determine the best course of action.

- It allows you to enumerate your points.

- It’s easy to follow for a reader.

- It’s very informal.

- There’s no reason to add the “-ly” suffix.

Clearly, “firstly, secondly, thirdly” are not appropriate in essays. Therefore, it’s best to have a few alternatives ready to go.

Keep reading to learn the best synonyms showing you what to use instead of “firstly, secondly, thirdly.” Then, we’ll provide examples for each as well.

What to Say Instead of “Firstly, Secondly, Thirdly”

- First of all

- One reason is

- Continuing on

- In addition

1. First of All

“First of all” is a great way to replace “firstly” at the start of a list .

We recommend using it to show that you have more points to make. Usually, it implies you start with the most important point .

Here are some examples to show you how it works:

First of all , I would like to draw your attention to the issues in question. Then, it’s important that we discuss what comes next. Finally, you should know that we’re going to work out the best solution.

2. To Begin

Another great way to start an essay or sentence is “to begin.” It shows that you’re beginning on one point and willing to move on to other important ones.

It’s up to you to decide which phrases come after “to begin.” As long as there’s a clear way for the reader to follow along , you’re all good.

These examples will also help you with it:

To begin , we should decide which variables will be the most appropriate for it. After that, it’s worth exploring the alternatives to see which one works best. In conclusion, I will decide whether there are any more appropriate options available.

“First” is much better than “firstly” in every written situation. You can include it in academic writing because it is more concise and professional .

Also, it’s somewhat more effective than “first of all” (the first synonym). It’s much easier to use one word to start a list. Naturally, “second” and “third” can follow when listing items in this way.

Here are a few examples to help you understand it:

First , you should know that I have explored all the relevant options to help us. Second, there has to be a more efficient protocol. Third, I would like to decide on a better task-completion method.

4. One Reason Is

You may also use “one reason is” to start a discussion that includes multiple points . Generally, you would follow it up with “another reason is” and “the final reason is.”

It’s a more streamlined alternative to “firstly, secondly, thirdly.” So, we recommend using it when you want to clearly discuss all points involved in a situation.

This essay sample will help you understand more about it:

One reason is that it makes more sense to explore these options together. Another reason comes from being able to understand each other’s instincts. The final reason is related to knowing what you want and how to get it.

“Second” is a great follow-on from “first.” Again, it’s better than writing “secondly” because it sounds more formal and is acceptable in most essays.

We highly recommend using “second” after you’ve started a list with “first.” It allows you to cover the second point in a list without having to explain the flow to the reader.

Check out the following examples to help you:

First, you should consider the answer before we get there. Second , your answer will be questioned and discussed to determine both sides. Third, you will have a new, unbiased opinion based on the previous discussion.

6. Continuing On

You can use “continuing on” as a follow-up to most introductory points in a list.

It works well after something like “to begin,” as it shows that you’re continuing the list reasonably and clearly.

Perhaps these examples will shed some light on it:

To begin, there needs to be a clear example of how this should work. Continuing on , I will look into other options to keep the experiment fair. Finally, the result will reveal itself, making it clear whether my idea worked.

Generally, “next” is one of the most versatile options to continue a list . You can include it after almost any introductory phrase (like “first,” “to begin,” or “one reason is”).

It’s great to include in essays, but be careful with it. It can become too repetitive if you say “next” too many times. Try to limit how many times you include it in your lists to keep your essay interesting.

Check out the following examples if you’re still unsure:

To start, it’s wise to validate the method to ensure there were no initial errors. Next , I think exploring alternatives is important, as you never know which is most effective. Then, you can touch on new ideas that might help.

One of the most effective and versatile words to include in a list is “then.”

It works at any stage during the list (after the first stage, of course). So, it’s worth including it when you want to continue talking about something.

For instance:

First of all, the discussion about rights was necessary. Then , it was important to determine whether we agreed or not. After that, we had to convince the rest of the team to come to our way of thinking.

9. In Addition

Making additions to your essays allows the reader to easily follow your lists. We recommend using “in addition” as the second (or third) option in a list .

It’s a great one to include after any list opener. It shows that you’ve got something specific to add that’s worth mentioning.

These essay samples should help you understand it better:

First, it’s important that we iron out any of the problems we had before. In addition , it’s clear that we have to move on to more sustainable options. Then, we can figure out the costs behind each option.

Naturally, “third” is the next in line when following “first” and “second.” Again, it’s more effective than “thirdly,” making it a much more suitable option in essays.

We recommend using it to make your third (and often final) point. It’s a great way to close a list , allowing you to finalize your discussion. The reader will appreciate your clarity when using “third” to list three items.

Here are some examples to demonstrate how it works:

First, you need to understand the basics of the mechanism. Second, I will teach you how to change most fundamentals. Third , you will build your own mechanism with the knowledge you’ve gained.

11. Finally

“Finally” is an excellent way to close a list in an essay . It’s very final (hence the name) and shows that you have no more points to list .

Generally, “finally” allows you to explain the most important part of the list. “Finally” generally means you are touching on something that’s more important than everything that came before it.

For example:

First, thank you for reading my essay, as it will help me determine if I’m on to something. Next, I would like to start working on this immediately to see what I can learn. Finally , you will learn for yourself what it takes to complete a task like this.

12. To Wrap Up

Readers like closure. They will always look for ways to wrap up plot points and lists. So, “to wrap up” is a great phrase to include in your academic writing .

It shows that you are concluding a list , regardless of how many points came before it. Generally, “to wrap up” covers everything you’ve been through previously to ensure the reader follows everything you said.

To start with, I requested that we change venues to ensure optimal conditions. Following that, we moved on to the variables that might have the biggest impact. To wrap up , the experiment went as well as could be expected, with a few minor issues.

- 10 Professional Ways to Say “I Appreciate It”

- 10 Ways to Ask if Someone Received Your Email

- 9 Other Ways to Say “I Look Forward to Speaking With You”

- How to Write a Thank-You Email to Your Professor (Samples)

We are a team of dedicated English teachers.

Our mission is to help you create a professional impression toward colleagues, clients, and executives.

© EnglishRecap

10 Other Words for “This Shows” in an Essay

Showing how one thing affects another is great in academic writing. It shows that you’ve connected two points with each other, making sure the reader follows along.

However, is “this shows” the only appropriate choice when linking two ideas?

We have gathered some helpful synonyms teaching you other ways to say “this shows” in an essay.

- Demonstrating

- This implies

- This allows

- This displays

Keep reading to learn more words to replace “this shows” in an essay. You can also review the examples we provide under each heading.

Removing “this” from “this shows” creates a simple formal synonym to mix up your writing. You can instead write “showing” in academic writing to demonstrate an effect .

Typically, this is a great way to limit your word count . Sure, you’re only removing one word from your essay, but if you can find other areas to do something similar, you’ll be more efficient .

Efficient essays often make for the most interesting ones. They also make it much easier for the reader to follow, and the reviewer will usually be able to give you a more appropriate grade.

Check out these examples if you still need help:

- The facts state most of the information here, showing that we still have a lot of work to do before moving forward.

- This is the only way to complete the project, showing that things aren’t quite ready to progress.

2. Demonstrating

Following a similar idea to using “showing,” you can also use “demonstrating.” This comes from the idea that “this demonstrates” is a bit redundant. So, you can remove “this.”

Again, demonstrating ideas is a great way to engage the reader . You can use it in the middle of a sentence to explain how two things affect each other.

You can also review the following examples:

- These are the leading causes, demonstrating the fundamental ways to get through it. Which do you think is worth pursuing?

- I would like to direct your attention to this poll, demonstrating the do’s and don’ts for tasks like this one.

3. Leading To

There are plenty of ways to talk about different causes and effects in your writing. A good choice to include in the middle of a sentence is “leading to.”

When something “leads to” something else, it is a direct cause . Therefore, it’s worth including “leading to” in an essay when making relevant connections in your text.

Here are some examples to help you understand it:

- This is what we are looking to achieve, leading to huge capital gains for everyone associated with it.

- I would like to direct your attention to this assignment, leading to what could be huge changes in the status quo.

4. Creating

Often, you can create cause-and-effect relationships in your writing by including two similar ideas. Therefore, it’s worth including “creating” to demonstrate a connection to the reader.

Including “creating” in the middle of a sentence allows you to clarify certain causes . This helps to streamline your academic writing and ensures the reader knows what you’re talking about.

Perhaps these essay samples will also help you:

- We could not complete the task quickly, creating a problem when it came to the next part of the movement.

- I thought about the ideas, creating the process that we know today. I’m glad I took the time to work through it.

5. This Implies

For a more formal way to say “this shows,” try “this implies.” Of course, it doesn’t change much from the original phrase, but that doesn’t mean it’s ineffective.

In fact, using “this implies” (or “implying” for streamlining) allows you to discuss implications and facts from the previous sentence.

You will often start a sentence with “this implies.” It shows you have relevant and useful information to discuss with the reader.

However, it only works when starting a sentence. You cannot use it to start a new paragraph as it does not relate to anything. “This implies” must always relate to something mentioned before.

You can also review these examples:

- I appreciate everything that they did for us. This implies they’re willing to work together on other projects.

- You can’t always get these things right. This implies we still have a lot of work to do before we can finalize anything.

“Proving” is a word you can use instead of “this shows” in an essay. It comes from “this proves,” showing how something creates another situation .

Proof is often the most important in scientific studies and arguments. Therefore, it’s very common to use “proving” instead of “this shows” in scientific essays and writing.

We recommend using this when discussing your experiments and explaining how it might cause something specific to happen. It helps the reader follow your ideas on the page.

Perhaps the following examples will also help you:

- They provided us with multiple variables, proving that we weren’t the only ones working on the experiment.

- I could not figure out the way forward, proving that it came down to a choice. I didn’t know the best course of action.

7. This Allows

Often, when you talk about a cause in your essays, it allows an effect to take place. You can talk more about this relationship with a phrase like “this allows.”

At the start of a sentence , “this allows” is a great way to describe a cause-and-effect relationship . It keeps the reader engaged and ensures they know what you’re talking about.

Also, using “this allows” directly after expressing your views explains the purpose of your writing. This could show a reader why you’ve even decided to write the essay in the first place.

- Many scenarios work here. This allows us to explore different situations to see which works best.

- I found the best way to address the situation. This allows me to provide more ideas to upper management.

8. This Displays

It might not be as common, but “this displays” is still a great choice in academic writing. You can use it when discussing how one thing leads to another .

Usually, “this displays” works best when discussing data points or figures . It’s a great way to show how you can display your information within your writing to make things easy for the reader .

You can refer to these examples if you’re still unsure:

- We have not considered every outcome. This displays a lack of planning and poor judgment regarding the team.

- I’m afraid this is the only way we can continue it. This displays a problem for most of the senior shareholders.

9. Indicating

Indicating how things connect to each other helps readers to pay attention. The clearer your connections, the better your essay will be.

Therefore, it’s worth including “indicating” in the middle of a sentence . It shows you two points relate to each other .

Often, this allows you to talk about specific effects. It’s a great way to explain the purpose of a paragraph (or the essay as a whole, depending on the context).

If you’re still stuck, review these examples:

- There are plenty of great alternatives to use, indicating that you don’t have to be so close-minded about the process.

- I have compiled a list of information to help you, indicating the plethora of ways you can complete it.

10. Suggesting

Finally, “suggesting” is a word you can use instead of “this shows” in an essay. It’s quite formal and works well in academic writing.

We highly recommend using it when creating a suggestion from a previous sentence . It allows the reader to follow along and see how one thing affects another.

Also, it’s not particularly common in essays. Therefore, it’s a great choice to mix things up and keep things a little more interesting.

Here are a few essay samples to help you with it:

- You could have done it in many other ways, suggesting that there was always a better outcome than the one you got.

- I didn’t know what to think of it, suggesting that I was tempted by the offer. I’m still weighing up the options.

Martin holds a Master’s degree in Finance and International Business. He has six years of experience in professional communication with clients, executives, and colleagues. Furthermore, he has teaching experience from Aarhus University. Martin has been featured as an expert in communication and teaching on Forbes and Shopify. Read more about Martin here .

- 10 Better Ways To Write “In This Essay, I Will…”

- 10 Other Ways to Say “I Am” in an Essay

- 11 Formal Synonyms for “As a Result”

- 10 Other Words for “Said” in an Essay

33 Transition Words and Phrases

Transitional terms give writers the opportunity to prepare readers for a new idea, connecting the previous sentence to the next one.

Many transitional words are nearly synonymous: words that broadly indicate that “this follows logically from the preceding” include accordingly, therefore, and consequently . Words that mean “in addition to” include moreover, besides, and further . Words that mean “contrary to what was just stated” include however, nevertheless , and nonetheless .

as a result : THEREFORE : CONSEQUENTLY

The executive’s flight was delayed and they accordingly arrived late.

in or by way of addition : FURTHERMORE

The mountain has many marked hiking trails; additionally, there are several unmarked trails that lead to the summit.

at a later or succeeding time : SUBSEQUENTLY, THEREAFTER

Afterward, she got a promotion.

even though : ALTHOUGH

She appeared as a guest star on the show, albeit briefly.

in spite of the fact that : even though —used when making a statement that differs from or contrasts with a statement you have just made

They are good friends, although they don't see each other very often.

in addition to what has been said : MOREOVER, FURTHERMORE

I can't go, and besides, I wouldn't go if I could.

as a result : in view of the foregoing : ACCORDINGLY

The words are often confused and are consequently misused.

in a contrasting or opposite way —used to introduce a statement that contrasts with a previous statement or presents a differing interpretation or possibility

Large objects appear to be closer. Conversely, small objects seem farther away.

used to introduce a statement that is somehow different from what has just been said

These problems are not as bad as they were. Even so, there is much more work to be done.

used as a stronger way to say "though" or "although"

I'm planning to go even though it may rain.

in addition : MOREOVER

I had some money to invest, and, further, I realized that the risk was small.

in addition to what precedes : BESIDES —used to introduce a statement that supports or adds to a previous statement

These findings seem plausible. Furthermore, several studies have confirmed them.

because of a preceding fact or premise : for this reason : THEREFORE

He was a newcomer and hence had no close friends here.

from this point on : starting now

She announced that henceforth she would be running the company.

in spite of that : on the other hand —used when you are saying something that is different from or contrasts with a previous statement

I'd like to go; however, I'd better not.

as something more : BESIDES —used for adding information to a statement

The city has the largest population in the country and in addition is a major shipping port.

all things considered : as a matter of fact —used when making a statement that adds to or strengthens a previous statement

He likes to have things his own way; indeed, he can be very stubborn.

for fear that —often used after an expression denoting fear or apprehension

He was concerned lest anyone think that he was guilty.

in addition : ALSO —often used to introduce a statement that adds to and is related to a previous statement

She is an acclaimed painter who is likewise a sculptor.

at or during the same time : in the meantime

You can set the table. Meanwhile, I'll start making dinner.

BESIDES, FURTHER : in addition to what has been said —used to introduce a statement that supports or adds to a previous statement

It probably wouldn't work. Moreover, it would be very expensive to try it.

in spite of that : HOWEVER

It was a predictable, but nevertheless funny, story.

in spite of what has just been said : NEVERTHELESS

The hike was difficult, but fun nonetheless.

without being prevented by (something) : despite—used to say that something happens or is true even though there is something that might prevent it from happening or being true

Notwithstanding their youth and inexperience, the team won the championship.

if not : or else

Finish your dinner. Otherwise, you won't get any dessert.

more correctly speaking —used to introduce a statement that corrects what you have just said

We can take the car, or rather, the van.

in spite of that —used to say that something happens or is true even though there is something that might prevent it from happening or being true

I tried again and still I failed.

by that : by that means

He signed the contract, thereby forfeiting his right to the property.

for that reason : because of that

This tablet is thin and light and therefore very convenient to carry around.

immediately after that

The committee reviewed the documents and thereupon decided to accept the proposal.

because of this or that : HENCE, CONSEQUENTLY

This detergent is highly concentrated and thus you will need to dilute it.

while on the contrary —used to make a statement that describes how two people, groups, etc., are different

Some of these species have flourished, whereas others have struggled.

NEVERTHELESS, HOWEVER —used to introduce a statement that adds something to a previous statement and usually contrasts with it in some way

It was pouring rain out, yet his clothes didn’t seem very wet.

Word of the Day

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Games & Quizzes

Usage Notes

Prepositions, ending a sentence with, hypercorrections: are you making these 6 common mistakes, a comprehensive guide to forming compounds, can ‘criteria’ ever be singular, singular nonbinary ‘they’: is it ‘they are’ or ‘they is’, grammar & usage, words commonly mispronounced, more commonly misspelled words, is 'irregardless' a real word, 8 grammar terms you used to know, but forgot, homophones, homographs, and homonyms, great big list of beautiful and useless words, vol. 3, even more words that sound like insults but aren't, the words of the week - mar. 22, 12 words for signs of spring.

Tips for Writing an Effective Application Essay

How to Write an Effective Essay

Writing an essay for college admission gives you a chance to use your authentic voice and show your personality. It's an excellent opportunity to personalize your application beyond your academic credentials, and a well-written essay can have a positive influence come decision time.

Want to know how to draft an essay for your college application ? Here are some tips to keep in mind when writing.

Tips for Essay Writing