- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Harvard Graduate School of Education - Gutman Library

Critical Pedagogy

- Introduction to Critical Pedagogy

About this Guide

What is critical pedagogy, why is critical pedagogy important.

- Types of Critical Pedagogy

- Getting Started with Critical Pedagogy

- Publications in Critical Pedagogy

Critical Pedagogy Research Librarian

This guide gives an overview to critical pedagogy and its vitalness to teaching and education. It is not comprehensive, but is meant to give an introduction to the complex topic of critical pedagogy and impart an understanding of its deeper connection to critical theory and education.

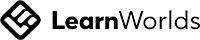

One working definition of critical pedagogy is that it “is an educational theory based on the idea that schools typically serve the interests of those who have power in a society by, usually unintentionally, perpetually unquestioned norms for relationships, expectations, and behaviors” (Billings, 2019). Based on critical theory, it was first theorized in the US in the 70s by the widely-known Brazilian educator Paolo Freire in his canonical book Pedagogy of the Oppressed (2018), but has since taken on a life of its own in its application to all facets of teaching and learning. The "pedagogy of the oppressed," or what what we know today to be the basis of critical pedagogy, is described by Freire as:

"...a pedagogy which must be forged with, not for, the oppressed (whether individuals or peoples) in the incessant struggle to regain their humanity. This pedagogy makes oppression and its causes objects of reflection by the oppressed, and from that reflection will come their necessary engagement in the struggle for liberation. And in the struggle this pedagogy will be made and remade...[It] sis an instrument for their critical discovery that both they and their oppressors are manifestations of dehumanization." (p. 48)

Perhaps a more straightforward definition of critical pedagogy is "a radical approach to education that seeks to transform oppressive structures in society using democratic and activist approaches to teaching and learn" (Braa & Callero, 2006).

There are many applications of theory-based pedagogy that privilege minoritarian thought such as antiracist pedagogy, feminist pedagogy, engaged pedagogy, culturally sustaining pedagogy, and social justice, to name a few.

Billings, S. (2019). Critical pedagogy. Salem press encyclopedia. New York: Salem Press.

Braa, D., & Callero, P. (2006, October). Critical pedagogy and classroom praxis. Teaching Sociology, 34 , 357-369.

Freire, P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Critical Pedagogy is an important framework and tool for teaching and learning because it:

- recognizes systems and patterns of oppression within society at-large and education more specifically, and in doing so, decrease oppression and increase freedom

- empowers students through enabling them to recognize the ways in which "dominant power operates in numerous and often hidden ways

- offers a critique of education that acknowledges its political nature while spotlighting the fact that it is not neutral

- encourages students and instructors to challenge commonly accepted assumptions that reveal hidden power structures, inequities, and injustice

Kincheloe, J. L. (2004). Critical pedagogy primer. P. Lang.

- Next: Types of Critical Pedagogy >>

- Last Updated: Mar 20, 2024 4:33 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/criticalpedagogy

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

- Staff Directory

- Workshops and Events

- For Students

- Digital Tools and Critical Pedagogy: Compassionate Pedagogy as a Classroom Practice

by Thomas Keith | Mar 13, 2024 | Instructional design , Pedagogy , Services , Universal Design for Learning

This post is the third installment in a series on how to implement the principles of critical pedagogy with digital tools. For more information, please see previous installments in this series . The author wishes to thank ATS instructional designers Joe Olivier and Cheryl Walker for valuable suggestions that improved this piece.

A key tenet of critical pedagogy as it is currently practiced is compassionate pedagogy . In this post, we shall examine what compassionate pedagogy does (and does not) entail, as well as simple and easily implemented methods by which you can integrate the principles of compassionate pedagogy into your classroom praxis.

What Is Compassionate Pedagogy?

At its heart, compassionate pedagogy is an educational praxis that takes into consideration the physical and emotional well-being of both students and instructors . It entails a fundamentally cooperative, rather than adversarial, relationship between instructors and students, with each group extending understanding and care to the other.

As a faculty member or instructor, you may be wondering how you can best apply this approach to your students. Some broad considerations to keep in mind are:

- Students have different backgrounds and needs. A “one size fits all” approach to pedagogy runs the risk of ignoring the individuality of students and even leaving some of them behind.

- Circumstances outside the classroom matter. Difficulties such as food insecurity, housing insecurity, or lack of reliable internet access can impede students’ success in your course.

- Flexibility is important. A rigid approach to pedagogy leaves little room to adjust your approach when students are overwhelmed or otherwise in need of help.

What Is Compassionate Pedagogy Not?

It should be stressed at the outset that compassionate pedagogy does not mean either of the following:

- Reducing academic rigor. A compassionate course is not the same as an easy course. It means, instead, that students are not kept from success in the subject matter of your course by circumstances beyond their control.

- Making you a counselor or therapist. It is not your responsibility to take on a mental health professional’s role. Instead, you should know how to lend a sympathetic ear and how to direct students toward personnel and resources who can best help them.

Simple Steps You Can Take Now

Fundamentally rethinking your course to incorporate compassionate pedagogy can be time-consuming. Fortunately, there are a number of simple steps you can take to help make your course more flexible and welcoming. These are discussed below.

Syllabus Steps

Your syllabus is the charter document of your course. Consider incorporating the following suggestions to help ease your students’ anxieties.

- Set out your approach on Day One. Make sure that your students know you are aware of the issues they may be facing. Stress that they should reach out to you without delay when they find themselves in difficulties.

- Make clear how to reach you. How should your students get in touch with you? Email? Phone? How quickly will you respond by each method? (You might give a typical response time, such as two business days.) What are your office hours? (Note that the term “office hours” may be confusing or opaque to some students , so you might consider using a different term such as “drop-in hours”.) All of this should be clearly communicated by your syllabus.

- List resources for students. These may include counseling resources, writing centers, tutors, and so on. Give as much information for each resource as you can, such as phone numbers, hours of operation, email or website addresses, etc. In a digital Canvas syllabus , these can be clickable links. You might also consider building a Canvas page with an ample list of resources. When you copy your Canvas site for reuse in future quarters, you can copy this page to avoid reinventing the wheel.

Assessment Design

When setting up assessments with Canvas, there are ways for you to maximize flexibility so that students have multiple avenues for submitting their work and need not feel overwhelming pressure over grades.

- Allow multiple submission types on Canvas Assignments. When a Canvas Assignment is of type Online Submission, you can allow multiple methods of submission : Text Entry, Website URL, Media Recordings, Student Annotation , and File Uploads . The more options you allow, the more flexibility your students will have, and the more fully you can achieve the principles of universal design for learning (UDL) . You can also increase the ease of submitting your assignment by not limiting the file extensions permissible for File Uploads (e.g. not restricting uploads to .docx or .pdf).

- Use Canvas to give extensions when appropriate. You can use the Assign To functionality supplied with each Canvas Assignment to give particular students or groups of students later due dates, if need be. You can also manually adjust submission status in the Gradebook ; for example, if a student submitted an assignment late but there are extenuating circumstances, you can change their submission status to On Time .

- Give additional attempts on Quizzes. There are a number of reasons why you might wish to give students additional quiz attempts. Students with unreliable internet access may experience difficulties while completing Canvas Quizzes. Alternatively, you may wish to use multiple quiz attempts as a learning opportunity . Whatever the case may be, you can manually unlock extra attempts to allow your students to retake the quiz as necessary.

- Use Assignment Groups to drop low grades. Canvas Assignment Groups allow you to set rules such that a given number of low (or high) scores are not counted in grade calculations . You can use these rules to give students breathing room. For example, you might create an Assignment Group of nine weekly writing assignments and set a rule that only the seven highest will be counted, so that students need not panic if they are unable to complete all nine.

- Leverage Poll Everywhere for classroom “temperature checks”. In difficult times, students may find it hard to concentrate on coursework. They (and you) are likely to experience heightened levels of anxiety in the wake of local, national, or global crises. You might consider using Poll Everywhere , the University’s instant polling system, for quick “temperature checks,” asking students how they are doing and what concerns are uppermost in their minds. You can then adjust your pedagogical approach accordingly.

Announcements and Communication

Few strategies are as vital to successful pedagogy as keeping the lines of communication open between you and your students. Canvas and other tools make it straightforward to communicate clearly and effectively.

- Leverage Canvas Announcements. Canvas Announcements are a robust system for reaching all students in your Canvas course site, or specific sections. You can attach files, schedule announcements for later posting, and even record video announcements. Canvas Announcements are also pinned at the top of your Canvas syllabus page, so that they are readily available for students to view. Using Announcements, you can ensure that your students are kept informed about upcoming events, changes to course policies, opportunities for extra credit or make-up work, and so on.

- Use Ed Discussion to supplement office hours. Ed Discussion is a powerful tool for Q&A and other forms of course discussion. Faculty at the University of Chicago have leveraged it with success as a homework help tool, allowing students to ask questions and get assistance from instructors, TAs, and peers at times when traditional office hours may not be available. Ed Discussion is integrated with Canvas, and ATS personnel can help you to get started if you wish to employ it in your course.

Compassionate pedagogy need not be difficult to implement, nor does it need to be a barrier to academic rigor. Through the judicious use of Canvas and other digital tools, you can help to build a sense of community among your students, alleviate the pressure they may feel due to the many stressors of student life, and point them toward help when they need it, thereby contributing to a healthier and more successful course.

Further Resources and Getting Help

For more tips on inclusive and compassionate pedagogy, check out UChicago’s Inclusive Pedagogy site .

If you would like to learn more about compassionate pedagogy and how to implement it, we encourage you to reach out to us. You can drop by our office hours (both virtual and in-person during academic quarters), come to one of our online workshops , or book a consultation with an instructional designer .

(Cover Photo by Dave Lowe on Unsplash )

Search Blog

Subscribe by email.

Please, insert a valid email.

Thank you, your email will be added to the mailing list once you click on the link in the confirmation email.

Spam protection has stopped this request. Please contact site owner for help.

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Recent Posts

- Explore “Hallucinations” to Better Understand AI’s Affordances and Risks: Part One

- Instructors: Participate in Our Academic Technology Survey

- Unlock the Capabilities of the UChicago Lightboard

- Search for a Syllabus in Canvas

- A/V Equipment

- Accessibility

- Canvas Features/Functions

- Digital Accessibility

- Faculty Success Stories

- Instructional design

- Multimedia Development

- Surveys and Feedback

- Symposium for Teaching with Technology

- Uncategorized

- Universal Design for Learning

- Visualization

The Edvocate

- Lynch Educational Consulting

- Dr. Lynch’s Personal Website

- Write For Us

- The Tech Edvocate Product Guide

- The Edvocate Podcast

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Assistive Technology

- Best PreK-12 Schools in America

- Child Development

- Classroom Management

- Early Childhood

- EdTech & Innovation

- Education Leadership

- First Year Teachers

- Gifted and Talented Education

- Special Education

- Parental Involvement

- Policy & Reform

- Best Colleges and Universities

- Best College and University Programs

- HBCU’s

- Higher Education EdTech

- Higher Education

- International Education

- The Awards Process

- Finalists and Winners of The 2022 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Finalists and Winners of The 2021 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Finalists and Winners of The 2020 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Finalists and Winners of The 2019 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Finalists and Winners of The 2018 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Finalists and Winners of The 2017 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Award Seals

- GPA Calculator for College

- GPA Calculator for High School

- Cumulative GPA Calculator

- Grade Calculator

- Weighted Grade Calculator

- Final Grade Calculator

- The Tech Edvocate

- AI Powered Personal Tutor

How to Set Up and Start Using a Cash App Account

Jazz research questions, interesting essay topics to write about japanese culture, good research topics about japanese art, jane eyre essay topics, most interesting invisible man essay topics to write about, most interesting jaguar essay topics to write about, most interesting jackson pollock essay topics to write about, good essay topics on italian renaissance, good research topics about islamophobia, how to implement critical pedagogy into your classroom.

Critical pedagogy is a teaching philosophy that invites educators to encourage students to critique structures of power and oppression. It is rooted in critical theory , which involves becoming aware of and questioning the societal status quo. In critical pedagogy, a teacher uses his or her own enlightenment to encourage students to question and challenge inequalities that exist in families, schools, and societies.

This educational philosophy is considered progressive and even radical by some because of the way it critiques structures that are often taken for granted. If this is an approach that sounds like it is right for you and your students, keep reading. The following five steps can help you concretely implement critical pedagogy into your classroom.

- Challenge yourself. If you are not thinking critically and challenging social structures, you cannot expect your students to do it! Educate yourself using materials that question the common social narrative. For example, if you are a history teacher, immerse yourself in scholars who note the character flaws or problematic structures that allowed many well-known historical figures to be successful. Or, perhaps, read about why their “successes” were not really all that successful when considered in a different light. Critical theory is all about challenging the dominant social structures and the narratives that society has made most familiar. The more you learn, the better equipped you will be to help enlighten your students. Here are some good resources to get you started.

- Change the classroom dynamic. Critical pedagogy is all about challenging power structures, but one of the most common power dynamics in a student’s life is that of the teacher-student relationship. Challenge that! One concrete way to do this is by changing your classroom layout . Rather than having students sit in rows facing you, set up the desks so that they are facing each other in a semicircle or circle. This allows for better conversation in the classroom. You can also try sitting while leading discussions instead of standing. This posture puts you in the same position as the students and levels the student-teacher power dynamic. It is also a good idea, in general, to move from a lecture-based class where an all-wise teacher generously gives knowledge to humble students to a discussion-based class that allows students to think critically and draw their own conclusions.

- Present alternative views. In step 1, you, the teacher had to encounter views that were contrary to the dominant narrative. Now, present these views to your class alongside the traditional ones. Have them discuss both and encourage them to draw their own conclusions. If a student presents a viewpoint, encourage him or her to dig further. Asking questions like “why do you believe that?” or “why is that a good thing” will encourage students to challenge their own beliefs, break free of damaging social narratives, and think independently.

- Change your assessments. Traditional assessment structures, like traditional power structures, can be confining. You don’t have to use them ! Make sure that your assessments are not about finding the right answer, but are instead about critical thinking skills. Make sure students are not just doing what they think they need to do to get a particular grade. You can do this by encouraging students to discuss and write and by focusing on the ideas presented above presentation style.

- Encourage activism. There is a somewhat cyclic nature to critical pedagogy. After educating yourself, you encourage students to think critically, and they, in turn, take their newfound enlightenment into their families and communities. You can do this by telling your students about opportunities in their community where they can combat oppression, like marches, demonstrations, and organizations. You can help students to start clubs that focus on bringing a voice to the marginalized. You can even encourage students to talk about patterns of power and oppression with their family and peers.

Concluding thoughts

Obviously, implementing critical pedagogy will look different in different subjects, and what works for one class may not work for another. For example, a history teacher may challenge an event that is traditionally seen as progressive, while a literature teacher may question a common cultural stereotype found in a book. A science teacher, on the other hand, may encourage students to look at the impact of scientific discoveries on marginalized groups. Often, this will involve finding common bonds between subjects as the critical approach is not confined to only one area of education and culture.

How have you implemented critical pedagogy in your classroom? What strategies have you found effective? Let us know by commenting below!

How to Support Without Hovering: Avoiding Helicopter ...

Why you don’t need a traditional college ....

Matthew Lynch

Related articles more from author.

4 Ways Americans Can Love Education Again

How to Implement the Reader’s Theater Teaching Strategy in Your Classroom

How Nature Teaches Kids What Technology Can’t

How to Implement Depth of Knowledge in Mathematics

Debate Topics for College Students

Strong Teacher to Student Relationships: A Key to Success

Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory pp 258–263 Cite as

Critical and Social Justice Pedagogies in Practice

- Mary C. Breunig 2

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2018

2654 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Critical pedagogy ; Educational practice ; Social justice pedagogy

Introduction

While pedagogy is most simply conceived of as the study of teaching and learning, the term critical pedagogy embodies notions of how one teaches, what is being taught, and how one learns. Critical pedagogy is a way of thinking about, negotiating, and transforming the relationship among classroom teachings, the production of knowledge, the institutional structures of the school, and the social and material relation of the wider community and society. Critical pedagogy is historically rooted in the critical theory of the Frankfurt School and was greatly influenced by the work of Karl Marx, particularly his views about labor. According to Marx, the essential societal problem was one of socioeconomic inequality, believing that social justice is essentially dependent upon economic conditions. The “New Left scholars” in North America, including Henry Giroux, Roger Simon, Michael Apple, and Peter McLaren...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Ayers, W., Quinn, T., & Stovall, D. (Eds.). (2009). Handbook of social justice education . New York: Routledge.

Google Scholar

Breunig, M. (2011). Problematizing critical pedagogy. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3 (3), 2–23.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed . New York: Continuum.

Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom . New York: Routledge.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2013). “Stakes is high”: Educating new century students. Journal of Negro Education, 82 (2), 105–110.

Article Google Scholar

Malott, C. S., & Porfilio, B. (Eds.). (2011). Critical pedagogy in the twenty-first century: A new generation of scholars . Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

Payne, P., & Wattchow, B. (2009). Phenomenological deconstruction, slow pedagogy, and the corporeal turn in wild environmental outdoor education. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 14 , 15–32.

Rumi. (2004). The essential Rumi (trans: Barks, C.). San Francisco: Harper.

Zmuda, A., Curtis, G., & Ullman, D. (2015). Learning personalized: The evolution of the contemporary classroom . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada

Mary C. Breunig

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mary C. Breunig .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand

Michael A. Peters

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer Science+Business Media Singapore

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Breunig, M.C. (2017). Critical and Social Justice Pedagogies in Practice. In: Peters, M.A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-588-4_234

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-588-4_234

Published : 08 March 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-287-587-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-287-588-4

eBook Packages : Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Paulo Freire and Critical Pedagogy

- An introduction to the course and your part in it. Do you see yourself as a change agent? Do you have an involvement in social change as an activist or organizer?

- What do you think Paulo Freire's message is in Pedagogy of the Oppressed , and is it relevant to your experience?

- Paulo Freire as thinker, teacher and activist

- The key concepts in Freire's work and how they might be understood

- Related thinkers in critical pedagogy and beyond

- Applying Freirean principles and methodologies in a concrete way

- The origins and development of critical pedagogy

- Freire's approach in the classroom and the dangers of treating Freire's approach as simply a set of teaching methods

- How Freire's pedagogy has influenced a variety of approaches, using contemporary examples

What's included?

- 10 main sessions

- 10 reflective tasks

- Community discussion

- 1 end of course assignment

- Course certificate

Situation Analysis

Associate membership, live seminars, sign up for this course and become part of our learning community, sign up for email updates, stay updated | stay current | stay connected, course team, course contents, frequently asked questions, can i view the course material without taking the assignments, how long does the course take, what do i need to do for the course certificate, do i get feedback during the course, paulo freire.

- About Paulo Freire

- Paulo Freire Biography

- Concepts Used by Paulo Freire

- Quotes by Paulo Freire

- All Courses

Online Courses

- CPD and Training

- Study at UCLan

- Consultancy

Coming Soon

- Communities and Conflict

- Social and Solidarity Economy

- Culture, Ideology and Belief

- Power, Politics and the State

- Global and Social Change

- Reading Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed

- Measuring Social Value

- Freire, the Artist and the Community

Professional

- CPD / Training

- Alternative Economics

- Community Wealth-Building

- Decolonizing Education

- Equality, Diversity and Inclusion in the Workplace

- INFACT Strategic Analysis for Action

- INSPIRE Cultural Action

Study at University

- MA at UCLan

- Participatory Budgeting

- Paulo Freire and Global Education

- Paulo Freire Study Workshop

- Starting in Community Organizing

- Sustainable Leadership

- Thinking Critically

Course Categories

- Critical Pedagogy

- Community Organizing

- Social Economy

- Cultural Studies

- Policy and Politics

- Global Studies

- Reading Pedagogy of the Oppressed

- Freire, the Artist & the Community

- INSPIRE Cultural Action

Mini Courses

- Paulo Freire: Life and Works

- Introduction to Cultural Studies

- Policy Analysis

- Globalization

University Degrees

- Masters Degree

Sign in/up with Google

Sign in/up with Facebook

Sign in/up with Linkedin

Sign in/up with Apple

Sign in/up with Twitter

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Kris Shaffer

It is easy for those of us invested in critical pedagogy to see need for major change in education in the U.S. It is also easy for us to write highly ideological manifesti that make sweeping philosophical statements about how things should be. One question I often hear from those getting their feet wet in critical pedagogy is where do I start? Many agree with the ideology and the goals of critical pedagogy and other movements seeking major change, but we cannot simply drop those changes into our current institutional structures. Never mind the fact that we have colleagues and students to win over before we can implement these changes with a chance at success.

But some of the issues raised by critical pedagogy are major ethical issues. It’s not that we can do something more efficiently or effectively, it’s that we see what we’re doing on the whole as being actually wrong . As a critical pedagogue, I can go along with something less effective much more easily than with something that goes against my newly pricked conscience. So when I disagree fundamentally with the direction something is headed, but am powerless to change it singlehandedly, what do I do? Do I forget about it and wash my hands of the situation? Do I leave in disgust? Do I bide my time until I can really do something? (And hope it doesn’t get worse in the mean time!) Do I try to make incremental changes, appeasing my conscience with the knowledge that I am improving things, albeit slowly?

As I’ve thought about various issues in various contexts, I’ve come to believe that I should work on at least three different planes — or resisting along three different fronts. Sometimes, only one is an option; sometimes all three. But by framing my thoughts and work this way, it helps me to identify what I can and can’t do, and to not feel like every class I teach needs to be a major revolution. I hope these three lines of resistance can help other people seeking to make changes where they are.

The first and highest line of resistance is pushing for major institutional change in policies and practices, like I did at Charleston Southern University with the social media policy. This is where we should push for large, sweeping changes — where our full ideology, even our manifestos, should come to the fore.

The second line of resistance is changing our own day-to-day practices. Major institutional change comes slowly, if at all. And we are unlikely to get everything we want on the highest level. But we can effect significant change on the local level. These changes are often incremental because of the lack of major institutional change, but they are no less important.

Often, I find myself working on both of these levels simultaneously. For example, I may speak against the use of letter grades or standardized tests (first line of resistance). But until there are major university-wide changes, I cannot operate entirely outside of the world of grades and SAT/ACT/GRE scores. However, I can ignore, or at least heavily de-emphasize, GPA and GRE scores in favor of writing samples and unique elements on the C.V. when considering graduate school applications to my department (second line of resistance).

Likewise, I can employ assessment practices in class that focus on formative assessment and verbal feedback over summative assessment and final grades. I can also use a standards-based, or criterion-referenced, grading system where I assign grades of P, B, A, or N (passing, borderline, attempted, not attempted) — encouraging students to think less about ABCDF grades, and to think more about the meaning of an assessment. (The fact that the letter grades stand for a word, and that B is better than A, both contribute to that.) Since these grades are assigned in reference to concepts or skills, rather than assignments, it also invites students to focus on the content we are exploring together and their intellectual development in light of it, rather than just a series of scores. This is by no means ideal, but it is an improvement that still fits inside university policies and draws student attention to the problems with those policies. It also allows me to demonstrate the value of other systems, and have data and student feedback to point to if and when the university actually considers changing its policies.

Not every change we would like to make can be accomplished within the policies set forth by our university, though. That’s where the third line of resistance comes in: teaching underground . Academic instructors can influence the intellectual and social development of our students outside the boundaries of the course. We can also influence the way our colleagues think about things. Further, our role as critical pedagogues need not be limited to the professional relationships we have with students and colleagues. We have an educational role to play outside the university, as well.

For example, while what we do during class, prep, and grading time is important, what happens during office hours often has a greater impact on our students. Even better can be meetings over coffee or the throwing of a frisbee. And education need not be limited to our tuition-paying university students. As a parent and the member of a vibrant faith community, I have two very important educational charges outside my professional life, in which I seek to put my critical-pedagogy ideals to work. Social media is another locus of pedagogy, if we use it as such. Many of us teachers use social media for pedagogical development, seeking the ideas of others that we can can appropriate for our own teaching. But we can also use it as an others-oriented place to teach other educators, especially given the large population of educators seeking to learn from others on those platforms.

These are not the only ways in which we can seek change and resist harmful practices in education. But I have found it helpful to frame my educational work in these three ways. For instance, I used to try and do everything that I found important in every class. When institutional policies or student preferences got in the way, I became frustrated — either with the policies, or the students, or with my own inability to make it all work. However, recognizing the difference between the first and second lines of resistance helps me see the value in making incremental local changes while pursuing big change outside the immediate context of my classes. Likewise, taking opportunities to “teach underground” helps me accomplish aims outside of class that I cannot (yet) accomplish in class. (Don’t underestimate the value of having coffee with education majors, for example, especially if they just read Paulo Freire in one of their education classes!)

Among the Hybrid Pedagogy community, we often focus on the ideology, and thus the first line of resistance. Of course, most of us live in a world where we can have our biggest influence on the second and third lines of resistance. (And communities like Hybrid Pedagogy are examples of that third line of resistance.) We do not live in Luther’s Wittenburg or Calvin’s Geneva; most of us live in Cranmer’s England. Reformation, if it comes at all, will come slowly and incrementally, and we may risk our livelihood if we push too hard on the first line of resistance too soon. But we all have things we can do on the second and third lines of resistance. The more we push there, and the more people we can bring along with us, the greater chance we’ll have of success when we do make that assault on the first line.

As a community that teaches each other underground, let’s keep our eyes fixed on the broad goals and help each other to make significant, incremental gains on the local level, both in class and off the books.

The following is a letter to my first- and second-year music theory and aural skills students at The University of Colorado–Boulder. This is my second semester at CU, and the music students and I are still getting to know each other. For some, this will be their first semester with me; others are still getting used to my pedagogical quirks. To help frame the semester, I will have them read and discuss this open letter.

My most profound educational experience was not a lecture, or a test, and certainly not a homework assignment from a workbook. My most profound educational experience was playing second horn for a brass sectional for our conservatory orchestra. We were playing Richard Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben , a piece full of difficult passages for the brass players. Our principal horn was away for an audition on that day, and our horn professor, Dale Clevenger (principal horn of the Chicago Symphony), played in his place. I sat right next to him, seeing and hearing what he was doing first-hand, and trying to match or complement him as I played. Even though he only talked to me for a fraction of the time, that single two-hour rehearsal was easily worth a year of lessons, or dozens of concerts. And no amount of lectures or readings could have accomplished what was accomplished by playing a hard piece alongside the greatest horn player in the world, trying to match his sound as I heard it.

Now I’m not the world’s greatest music theorist. But I am an expert in the things we will be studying, and I care deeply about fostering the best opportunities I can for you to learn them for yourselves. With that in mind, I’d like to set the tone for this semester by offering a few things to keep in mind as we work together. Though these are not part of the course content, do not appear on the syllabus, and will not be assessed, they are more important than the course content. These things will help us lay the groundwork to be successful in our engagement with the course material, and, even more importantly, they have broad applicability to learning processes in general — in this course, in other courses, and outside the classroom. We will occasionally reflect on these in class, as they apply to specific situations in which we find ourselves.

First, education is more than the transfer of information . Education involves the transfer of information, of course. However, there are things more important, and more difficult, than simply memorizing information. In our class, those things include the assimilation of concepts and the application of those concepts in musical activities. Assimilating concepts often requires engaging multiple perspectives on the same information — multiple theories about the same musical concept, multiple ways to perform the same kind of passage, etc. It also requires attempts at applying the material, such as composing, analyzing, or performing. These things are harder than taking notes and regurgitating them on a test, and often take longer than a single class meeting or homework assignment to figure out. For those of you who are used to courses that “test early and test often,” this may be uncomfortable and may feel, initially, ineffective. However, doing hard things and working to apply concepts leads to deeper, longer-lasting learning than lecture, baby-step homework, and a test you can cram for. That’s a big reason that I rarely lecture and don’t use workbooks: we need to do hard things and engage multiple routes through the material in order to truly understand and master it.

Education is training for life, not just a career, and certainly not just a job upon graduation . You are paying too much money and putting too much time into your education for it to be valuable for a few years of work only. Your education should help you develop skills that will last your entire career (which could be upwards of 50 years). We don’t have all the information that will be required of musicians working in 2060. However, what we do in these classes can help you develop the skills of inquiry and analysis you’ll need to figure out how to work in those new settings. We will also take multiple approaches to a single topic so that you can 1) see that there are always a diversity of ways to understand a single topic, and 2) have more tools at your disposal to choose from when facing something new that was not anticipated by your textbook’s authors or your professors.

Ask your private studio teachers, ensemble conductors, or other seasoned professionals you respect (in any field) what their most valuable educational experience was that has prepared them for their life and career. Was it a series of lectures? Was it a textbook reading? A workbook assignment? Or a hard project — maybe even one they created themselves — for which there was no textbook or how-to guide, but which pushed them to develop new ways of thinking about their work, and led them to create something they didn’t think they were capable of? You will get plenty of lectures and readings in your college education. I want you to find the tools and experiences that will help you develop the ability to do good, hard work when there are no lectures and readings.

In other words, I want you to learn how to learn . That means that at times you will be teaching yourself. This is an intentional choice. One of my chief goals is for you to take charge of your own education. Though I will help set a frame in which this will take place, many of you will feel uncomfortable, even overwhelmed, at this. That’s normal. It’s what independent learning feels like quite often. (Because it’s what teaching feels like.) However, if at any time you feel lost, please talk to me. I have gone through the same process many times before, both as a student and as a teacher. I may not remove the discomfort immediately, or at all, but I will help you learn to manage it and harness it to a positive outcome.

Education is about far more than grades . I understand that grades feel incredibly important. The university puts stock in them, your scholarships depend on them, and many of you are only able to be here because of those scholarships. You’re working hard to make sure you can stay here. Other students are, admittedly, minimizing their workload while maximizing their GPA, so they can spend time doing other things, often very good things. However, in both cases, focusing on grades leads us to miss the best things an education has to offer. Some of the most important things in a class are things that are hard to assess, so they’re not part of the grade. You have the opportunity to work with world-class scholars and creative professionals here, some of whom are your fellow students. Take advantage of that! Don’t think about your education as work for a boss who tells you what to do. You are making an investment. Do what you can to reap the greatest return on your investment (which is not only, or even chiefly, financial). Education is not a commodity that can be purchased; it is a process, and your tuition does not buy learning; it buys an opportunity to learn. That means figuring out what else a professor, or a book, or a piece of music, or a campus, or a city, or a group of fellow students has to offer you besides what is on the syllabus or in the course catalog. Yes, grades can be important, but they are not the goal: the goal is an intellectual, musical, professional, and social maturity that will allow you to get the most out of, and contribute the most to, your life.

A class is a negotiated space . Every class is full of students — and an instructor — whose backgrounds, goals, and attitudes differ. Even when students’ goals are congruent, the “best” route for each student towards those goals is different. Thus, a class activity is always a compromise that seeks to enable as many students as possible to make as much progress as possible towards those goals. And even though this means more freedom for all of you, there will be times when I have to make decisions for the group. But they will be made with this need for compromise in mind.

Teaching is not performance . My goal is not to dazzle you with my intellect or to blow your mind with the course content. Nor is it to entertain you or to charm you with my personality (though I may). Instead, my goal is to create an environment that is conducive to your musical and intellectual growth. While I do have some tricks up my sleeve that will help you “get it” quickly, and I do have some class activities that may be entertaining or inspiring, much of our work will look like your daily work in the practice room. Mastering something new is like that, as you know from the hours you’ve spent composing or practicing. However, I will make sure that everything we do, whether mind-blowing or mundane, will have value.

Finally, I am not perfect . Nor are any of your other professors. We are experts in the fields we teach, and some of us are experts in the art of teaching. However, we make mistakes. We also have an imperfect university structure to work within (semesters, grades, class schedules, etc.), and each pass through the material brings new students with different experiences, backgrounds, skills, sensitivities, prejudices, loves, career goals, life goals, financial situations, etc. There is no one way — often not even a best way — to teach a topic to a student, let alone one best way to teach a topic to 15 or 40 (or 400) students simultaneously. So even when we do our jobs well, it won’t fit everyone. And even if it did, you will have bad days, too. This is why I will provide you a variety of resources and tasks to help you learn. If you take charge of your own education, make full use of the resources most helpful to you, and make full use of the people around you (myself and your fellow students), you will make significant strides in your musical growth.

Most of you did not come to music school so that you can make lots of money. And I doubt any of you came here just to get good grades. In fact, I bet all of you are here because you love music. And most of you enjoy making and talking about music together with others. That’s exactly what these classes are about. If you focus on making and exploring music collaboratively in this class, deep learning will happen. (And, yes, good grades will follow.) You will also grow as musicians who can continue to educate yourselves when you leave CU. So let’s make the most of our time together not by seeing how much information we can get from my notebook into yours, but instead by learning how to make music, and to make insights about music, in new ways.

Critical Digital Pedagogy Copyright © 2020 by Kris Shaffer is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Radical Pedagogy (2007)

Issn: 1524-6345, teaching resistance: an exercise in critical pedagogy.

Jennifer Stewart, Ph.D. Department of Sociology Grand Valley State University 1 Campus Drive Allendale, MI 49401 (616) 331-2168 [email protected] College of San Mateo [email protected]

Jennifer Stewart is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Grand Valley State University. Her teaching and reseach interests include Race & Ethnicity, Social Problems, and Pedagogy. Dr. Stewart is currently working with a student anti-racism theater group (Act on Racism) who perform skits based on the incidents gathered from the homework assignment described in this paper.

In this paper I describe a critical pedagogy assignment used in an upper-division Race and Ethnicity course. This is the last assignment in the semester and challenges students to engage in acts of resistance against racism and racial inequality encountered in everyday interactions. I developed this project as a response to students' frustrations regarding the eternal and immutable nature of racism in America. Included are examples of student actions as well as suggestions for how to orient discussions to build up to this activity.

INTRODUCTION

The objective of critical pedagogy is to generate in students the desire and ability to ask questions about relationships observed in society (Freire, 1970). Further, critical pedagogy embraces the perspective that education should be a liberating experience, designed to spur students on to seek social and economic justice (Berling, 1999; Freire, 1970). Modern educational contexts, however, are often not conducive to critical pedagogy. Large class sizes, limited class time, and the demanding work and school schedules of contemporary college students all function to hamper learning beyond the “banking model” in which students receive and then regurgitate information without the application of critical thinking skills, or the ability to learn on their own (Freire, 1970; Nieto, 2002).

Traditionally, sociology is viewed as a science of objective observers of social facts such as inequality (i.e., is “value free”). That sociology does not intend to create activists is unpalatable to many sociology students and teacher/scholars. In fact, learning about social problems without developing concrete solutions to those problems risks rendering sociology obsolete.

As not all students of sociology will enter academic workplaces, they need to be given the tools to interpret the world through a sociological lens and to apply critical thinking skills in devising solutions to social problems (Basirico, 1990). The creation and application of sociological solutions implies a deeper understanding of sociological concepts and theories (Basirico, 1990). Students who passionately wish to change conditions discussed in courses need to acquire those skills. I have found ways to help students develop strategies of resistance in the context of a Race and Ethnicity course.

White students have been socialized to believe that we live in a color-blind society or that the denial of the existence of race is the only workable solution with regard to structured racial inequality. Students of color, on the other hand, are all too aware that we do not live in a color-blind society, nor is that the goal of all Americans. In fact, appeals to a color-blind society threaten to negate some of the individuality students of color have cultivated based on race (Dalton, 1995). A big part of the challenge of teaching about racial and ethnic inequality is to get students to understand that while some of the more “obvious” or overt forms of racism have been collectively deemed unacceptable, many more insidious forms of racism and racial inequality remain deeply entrenched in American social interactions and institutions. Once that understanding is achieved, however, it is imperative that students be given tools to deal with their newly acquired awareness of racism and the mechanisms through which modern racism operates.

Increasingly, colleges and universities (following the lead of long-standing sociology programs) are requiring their students to complete “diversity” and/or race and ethnicity courses. Learning about racial oppression can be disheartening to say the least, producing in students a sense of futility with regard to addressing social problems that appear to be such an entrenched part of American history. In fact, students often comment that systems of racial inequality are immutable and somehow inevitable.

Given that racism and racial inequality have persisted for centuries in the United States, a semester is surely not enough time to change such systems of oppression…or is it? In this paper, I describe an assignment that allows students the opportunity to actively confront some aspect of racism and inequality. I developed this assignment specifically to address the frustration voiced by students: they feel powerless to alter what they find to be a reprehensible component of American life. This assignment also provides wide latitude of avenues of action for individual student engagement. Finally, this exercise could be extended to other dimensions of inequality such as gender, sexuality, and social class.

Although, when I initially assigned this activity I worried that the “acts of resistance” would be fairly trivial (e.g., limited to enforcing “political correctness” in speech), the response and range of actions taken by students suggests the potential power and appeal of this assignment. I now instruct students that there is no such thing as a “trivial” act of resistance.

In addition to Richard Schaefer’s (2003) Racial and Ethnic Groups , students are assigned Paula Rothenberg’s (2001) White Privilege: Essential Readings on the Other Side of Racism, as well as Doane and Bonilla-Silva’s (2003) White Out: The Continuing Significance of Racism. Over the course of the semester, we have several discussions oriented around the pieces in these texts. Their acts of resistance often reflect or draw on the concepts, theories, and suggestions for change provided by the authors included in this collection.

The Context

Lake State University is located in the Midwest. The student body, as well as the surrounding community, is fairly homogenous with respect to race : 88.5 percent of the student body is identified as white, 4.7 percent African American, 2.4 percent Hispanic, 2.1 percent Asian/Pacific Islander, and .6 percent American Indian. Although segregation in the surrounding region has declined somewhat in recent years, many of the communities from which Lake State University’s students are drawn are “hyper-segregated” (Glaeser and Vigdor, 2001). In fact, many white students relate that there were no students of color in any of the primary and secondary schools they attended.

I use this assignment in an upper-division course titled “Race and Ethnicity”. This course is required for Sociology, Criminal Justice, and Social Work majors. It is also a course that fulfills a general education requirement. Therefore students’ fields of study range from art and business, to nursing and physical therapy.

Description of Assignment

The assignment is the last in a series of five assignments. Students have 3 options. The first option is open to those who are privileged on the basis of race. Students who consider themselves racially privileged discuss 2 or 3 privileges they were unaware accrued to their racial category/status before taking the class (i.e., not having to think about their racial status in a variety of situations, finding barbers and hairdressers). The second option is open to those who are disadvantaged on the basis of race. Students who choose this option discuss experiences that they believe reflect or were shaped by racial disadvantage (i.e., driving while black or brown, being denied housing, being followed or ignored in stores). I provide these first two options for those who are uncomfortable with the third option that is the focus of this piece.

The third option is a challenge for students to engage in an act of resistance. I try not to restrict the range of responses available to students but some rules are necessary to ensure personal safety and/or liberty. The rules for the act of resistance are as follows: 1) students may not use violence; 2) students should attempt to refrain from using insults and inflammatory language; and 3) students may not violate any laws in the course of completing this assignment. In contemporary society, students tend to perceive racism and/or racial inequality as social problems solved through grand measures and/or policies. The purpose of this assignment is to make students aware that racism and racial inequality can be addressed, in part, through everyday interactions and individual decision-making.

Because confronting racism often invokes fears of acts violence and rejection (Kivel 1996; Tatum 2003), I am very explicit about giving examples of unacceptable and acceptable acts of resistance for the purposes of this assignment. For instance, we have deemed face-to-face confrontation of hate groups such as KKK, white supremacy movements, or Christian Identity as off-limits for this assignment. We do discuss ways that we can safely confront these groups such as writing letters to the editor or to elected officials. These rules are intended to steer students away from endangering themselves or others and often challenge them to think more critically about the everyday places that racism lives.

Similarly, we try to steer ourselves away from insulting language that could escalate a confrontation. As Wildman and Davis (1997) argue, calling someone a “racist” generally results in defensive posturing and a focus on the individual, attitudinal nature of racism rather than on the institutional and social components of racism. For this assignment, emphasis is placed on trying to question the rationale behind prejudicial notions and actions. Students are challenged to focus on the myths and stereotypes prevalent about minority groups in American society and to deconstruct those factors in the formation of prejudicial beliefs and behaviors.

We discuss this assignment about midway through the semester even though it is not due until the last day of class. It is important to give students time to think about the nature of their acts of resistance so some of the fears attached to this option can be allayed and so they are prepared to engage in resistance. Many students respond in their assignments that the first time they had an opportunity to resist, they were caught off guard and failed to act. It is also important to provide ample time for students to complete the assignment as many acts of resistance occur spontaneously (e.g., while waiting in line at a grocery store).

I have used this assignment for two courses per semester, three semesters per year for three years. The percentage of students electing to engage in the third option (the act of resistance) rather than the discussions of privilege and disadvantage have ranged from a low of 60% to a high of 90%. On average 75% of students choose this option.

Challenging “White” As Normal

Critical studies of whiteness have generated a wealth of research on the meaning of whiteness. Whiteness has been defined as “normal”, invisible, unspoken, and the standard by which all other groups are measured (Dyer, 1997; Frankenberg, 1993; Lipsitz, 1995). Tied to the perception that whiteness is the normative state of being, is the idea that racism and racial inequality are phenomena disconnected from whites. In other words, the burden of finding solutions to racism and discrimination is a burden not for whites but for people of color (Lipsitz, 1995; Kivel, 1996; Morrison 1992). In setting the scene for her act of resistance, one white student wrote,

“In white people, talking about discrimination, prejudices, or racism is frowned upon…I think white people can choose whether they want to believe that discrimination exists or not.”

Some white students, therefore, choose as their act of resistance to start and maintain a discussion about racism and racial inequality with their family members or within other network contexts. Though at first I deemed this a relatively “easy” act of resistance, I soon understood my perceptions about the ease of talking about racism with family members were flawed, especially given power relationships between parents and children. For example, one student whose son was in the hospital recounted an event in which her mother refused to buy a magazine requested by her son.

“After we left his room, my mother let me know she had found The Source , but refused to buy it for him. Sounding totally disgusted, she went on to say how she thought the magazine was inappropriate for him to be reading. When I asked her why, she said it was because it was all about black people and their “hip hop” music….I decided this was a great opportunity to confront my mother about her prejudice and discrimination…my mother’s prejudices were not only limiting her, but in this circumstance were also limiting to my son. I took this opportunity to explain that when I was growing up, her beliefs of prejudice and actions of discrimination impacted my view as well, adding that I have chosen to raise my children with a much different view towards minority group members. I want my children to experience a more balanced life; I also want for them to understand the effects prejudice and discrimination have on individuals and on society.” (white female)

Parents and family members are often shocked, angered, and, conversely, sometimes even relieved to hear their children discuss the topic of racism. In general, students are quite anxious about their family’s responses but report a sense of accomplishment and independence in expressing their views about the validity of societal (and parental) beliefs about race and racial inequality.

Additionally, some students have used this assignment to challenge their own comfort boundaries. For example, white students have attended events sponsored by minority student groups on campus that white students have historically avoided. They relate their experiences as the “other” to the experiences of minority students attending a predominately white institution. Additionally, students have attended multi-cultural events taking place in the larger community. These events have included potlatches, a Juneteenth celebration, and a local “Summit on Racism”.

Attacking “Racial Codes”

Tatum (2003) and Sleeter (1994) argue that whites employ racial codes to delineate racial boundaries. Incorporated in this code are race - based and biased jokes, behaviors and actions that establish group boundaries, and the direction of conversation to whites only. Another trend in students’ acts of resistance is the dismantling of this racial code. The opportunities to do so often present themselves spontaneously in a variety of “real world” settings. Students have confronted family members, roommates, strangers, and, professors and challenged their use of racial slurs. For example, one student who works as a bank teller addressed the emerging stereotyping of persons of Arab descent (or those mistakenly assumed to be of Arab descent), increasingly prevalent since the events of 2001. A white male customer made the following comment regarding an Indian customer of the bank to the student: “Doesn’t it make you scared to have towel heads coming in here?” The student attempted to confront the in-group boundary establishment by pointing out the erroneous assumption of the white male customer:

“I asked him if he knew that the Indian customer wasn’t Middle Eastern, if that was what he was implying, and that he was from India. I also told him that even if he were Middle Eastern, I still would have no reason to be scared of him...Our Indian customer had overheard this entire conversation and came over to me. He laughed and said ‘I need you to come with me everyplace. No one believes I’m not Middle Eastern and I get treated badly.” (white female)

Another student with a penchant for on-line games described his efforts at rejecting racial codes and racist language even in an “anonymous” setting:

“One player called another player a “nigger” because he thought the other guy was cheating. I typed in that he better stop using racial slurs or I would begin a vote to have him kicked out. He...ignored me. I left that particular game server and went to another server to play.”

After a short period of time, the player who had used the racial slur caught up to the student and demanded an explanation.

“I typed in that yes, he was being racist in the last match I played and that I left because I have a no-racial-insults policy while I am playing on-line. Another player typed in “Right On!” Maybe this was not a life changing act of resistance but it showed about eighty-five on-line players that there are some people out there who find racial slurs and bigotry intolerable.” (white male)

Yet another student chose a more public setting, the student union, for his act of resistance:

“My friend and I shoot a lot of pool. We are there probably 3 or 4 days a week so we know the crowd that hangs out there a lot. There is this one kid, that me and my friends frequently play with…one particular day there happened to be a very large group of African American girls who seemed to be possibly celebrating a birthday party. At several points in time the girls got rather loud and it became very obvious that it was very annoying to our fellow pool-playing partner. After about five or six games, the kid made an extremely racist and offensive remark. After my shot I stopped and informed him that they were doing nothing wrong, they didn’t have to be quiet, and that if he was celebrating a friend’s birthday with all his buddies they would probably be twice as loud as these girls. I then put my cue away and told my friend and the kid who made the remark that I was leaving.” (white male)

Not long after the beginning of the war between the U.S. and Iraq, while riding the campus bus, a student observed an interaction between a white male and an Arab American male. The white male demanded to know whether the Arab American student was a supporter of the Iraqi regime. In her assignment, the student wrote:

“I was shocked that he had asked such a question. My mind started to fill up with some thoughts of anger. Before I even knew it I had turned to the man who had asked the question and asked him why he didn’t ask me that question also. He got very quiet then he said that he didn’t ask me that question because I was an American. So I told him just because someone is Arab it doesn’t...mean that they are either supporter of terrorism or supporters of the Iraqi government. I went on to say that he didn’t know where the student was born so he didn’t know if he was an American or not. I tried to point out to him that it didn’t matter where he was from; the only thing that matters is he is here now.” (African American female)

The student reported that a conversation about ethnic profiling and the war, lasting twenty minutes, occurred after this incident between the students traveling to campus on the bus.

Institutional Contexts

Some students attempt to address an institutional aspect of discrimination. This

trend is much less common than others discussed as students rarely have positions from which to influence institutional components of discrimination. When they do resist institutional discrimination they do so by either drawing attention to an issue or attempting to change that institutional component. For example, one minority student, who held a position of relative influence on campus, tried to point out that the University had neglected the interests of minority students in programming entertainment.

“One student even told me he thought it was really ‘shady the way the African American community was disregarded’. I decided that I had better tell the others that some of the students that we are elected to represent are angry, for racial reasons. I let them know that we had been, in a quiet fashion, accused of racial discrimination. Later some… would say that contrary to my report, they heard nothing but positive reactions…They made no mention of race. I just hope that no one ever asks why Lake State University can only retain seventy percent of its minority freshman yearly. They might not like the answer.” (African American male)

Another student chose to use her responsibility for hiring and firing new employees at her work site as a way to challenge institutional contexts of inequality. She worked at a health and fitness club whose members were exclusively white. We had discussed in class how the tendency to hire family members and friends can, when combined with residential and school segregation, create homogenous work settings as well. During the semester, a position for a new lifeguard opened up. Though in the past she might have selected a lifeguard recommended by a member, this time she selected the most qualified person for the job. The most qualified person was a woman of Asian American descent. Immediately upon being hired, members began to lodge complaints with the student regarding the abilities and competency of the new lifeguard. The student patiently addressed each complaint, defending the right of the woman to work at the club. After two months, the lifeguard had become a very popular and well-liked member of the club staff. In her written assignment, the student reflected on the isolation and sense of “otherness” potentially experienced by the lifeguard and vowed to increase the diversity of the staff at her club.

Because many students work in retail establishments, discussions of racial profiling in retail settings is a prominent topic in classes. White students state that they are often pressured to be hyper-vigilant when minority group members enter. They are often instructed that they must do this to limit theft. One student observed, and reacted to the following incident which she believed to be racial profiling in a retail context:

I watched as a white man walked towards the exit with three little boys trailing behind him, each was pushing a brand new bike out the door. The white woman who is the store greeter just kept doing her business of straightening her flyers, and work area. The man and kids left with no need to display proof of purchase to the greeter, and I went back to watching my kids. A black man soon came to the door pushing a bike as well. I then witnessed the greeter step from behind her little desk and ask the man for proof of purchase. He searched for his receipt, showed it to the greeter, and was on his way. I approached her and began to speak stating that I had noticed that she asked a black man who was pushing a bike for a receipt while not questioning the white man with three bikes for a receipt. ...I went on trying to explain to her that it is common for people not to even notice their racist behavior because of the fact that the society in which we live condones the behavior.” (white female)

Students who address the issue of profiling in retail settings often point out that their own experience contradicts the validity of profiling as a strategy to reduce inventory losses. They have found shoplifting to be equally distributed among all racial and ethnic groups.

Discrimination Tests

During the semester, we examine many components of discrimination. For example, the students watch media reports on instances of racial discrimination in

housing, lending, and sales. They also watch pieces on “linguistic profiling”. These media reports are often based on the results of discrimination tests in which two testers are matched along all dimensions (e.g., gender, age, ability) except race. A final example of the outcome of this assignment can be shown in the form of tests devised by students to detect discriminatory behavior.

“On Saturday nights my friends and I usually go to the same bar around the same time. ...The dress code at this particular establishment is relatively relaxed and in the 6 months or so that I have been going there I have only seen one person get asked to leave because they were wearing something inappropriate. It just so happens that that one person was a black male.” (white male)

The student went on to describe the details of this incident. The black male described was a co-worker of a friend of the student. The man who was denied entry due to his clothing was wearing a “Nike fleece sweat suit”. The students were discussing what had happened on the way back to the car and debated whether they had ever seen a patron at this establishment wearing a sweat suit. The general consensus was that they had. So, the black male and the student writing this assignment traded clothes in the parking lot. The white student, wearing the same sweat suit for which the black male had been denied entry, was allowed into the club fifteen minutes later. He pointed out this discrepancy in race and treatment to the bouncer making the decision and left the club. He and his friends have not returned since. As a class we discussed how this student’s experience illustrates the use of supposedly “neutral” rules to enforce racial discrimination.

Finally, a Mexican American student enlisted the help of a friend to determine whether his suspicions were correct regarding his own experience of discrimination. The student described how he feels he must carry his I.D. at all times. Part of this need, he argues, is due to his age and the fact that he is in a college town where store and bar owners must, by law, be very vigilant about checking I.D. for age tested purchases (i.e., cigarettes and alcohol). His white friends, he states, are subject to the same rule so he is confident that it is being applied fairly. That was not the case, however, when he went to the bank. He decided to test his suspicions.

“We went to our bank in a different neighborhood so the tellers would not know us, and we both went without ID’s and attempted to cash our checks. It was busy inside so we did not get the same teller as I had hoped...I was denied the ability to cash my check and my friend walked out with his money. I vocally pointed out how I was not allowed to cash my check without ID and my friend who was white was allowed to cash his check without ID.” (Mexican American male)

The students went back to their car, picked up their IDs and closed their accounts at that bank.

I would include one final step in this assignment: allow students to share their experiences and acts of resistance with each other. As previously mentioned, I introduce this assignment midway through the semester. I have found that the more we discuss our actions as a class, the greater the likelihood that students will choose the act of resistance for their final homework. Every week I ask if anyone has encountered an opportunity to engage in an act of resistance. Sometimes students are unsure if their acts “count” or were done according to the rules of the assignment. I allow the class to vote on whether certain acts qualify or not as long as they can defend their decision. I also encourage students to essentially ignore me and ask questions of each other. They query fellow students about the level of anxiety they felt before, during, and after their actions.

On the day that the assignment is due, we devote the entire class period to discussing students’ actions. We debate about the types of discrimination or inequality addressed by each act of resistance. We critique our own behavior and discuss whether there are other ways to address the specific instance of racism being examined. We even talk about how nervous we were or what types of responses we anticipated. It is helpful for students to know that many were scared to act; but they were happy with their actions and often the responses to their actions afterwards.

There is one difficulty that teachers may have in instituting this assignment: assessment. Educational institutions demand that students’ work be assessed based on some “objective” criteria. Students are also demanding of the need to be assessed through the assignment of grades. Unfortunately, assessment, particularly in this case, assigns “value” and differentiates among acts of resistance , demanding that some criterion be developed which ranks various student acts (Spademan, 1999). I find this

practice contrary to the goals of critical pedagogy. Therefore, I use this assignment almost as an extra credit assignment. When students are informed that their actions will not be ranked, they are able to act without the constant worry of assessment.

There are long-range implications of this assignment. Resistance can be addictive. After their semester was over, several members of one class protested a billboard campaign sponsored by a local developer. They wrote letters to the advertiser and developer explaining their objections to the advertising campaign. Students also report that they hope for, and have observed occasionally, a “pay it forward” effect. In other words, the students often state that they think their actions can serve as the basis for action for friends, roommates, and siblings, among others. Whites hesitate to act against racism for fear of backlash and loss of privilege (Kivel 1996). Many students counter that they can serve as role models for acts of resistance.

This assignment fulfills the goals of critical pedagogy. It causes students to ask questions regarding observed inequalities: What is the basis for the differential outcomes we observe? Is race a determinant of inequality in specific situations? What can I do to change the inequalities I observe? Furthermore, by maintaining relationships with students after the semesters end, I would argue that the ability and tendency to ask questions about race and racism and to formulate solutions does not end with the assignment of final grades but extends into the future.

In this paper, I have given examples of an assignment that calls on students to resist racism and racial discrimination. This assignment is meant to empower students and address an often-voiced frustration on the part of students who learn about American systems of racial inequality. Clearly acts of resistance could also occur along multiple lines of difference.For example, students could be challenged to address systems of gender-based privileges. The same methods described in this paper could be applied to developing a critical and liberating approach to dismantling gender inequality (as well as inequality based on social class and heterosexist privilege).

It is also a hope that this assignment, when students graduate, will be a reminder of the agency possessed by individuals to create, maintain, alter, and dismantle social inequalities. By providing an initial insight into that agency, graduates may learn to question institutional rules and effects in order to eradicate structures of inequality from positions of relative power.

Basirico, L. 1990. “Integrating Sociological Practice into Traditional Sociology Courses,” Teaching Sociology, 18: 57-62.

Berling, J. 1999. “Student-Centered Collaborative Learning as a “Liberating” Model of Learning and Teaching,” Journal of Women and Religion, 17: 43-55.

Dalton, H. 1995. Racial Healing. Doubleday.

Doane, A. and E. Bonilla-Silva (eds.). 2003. White Out: The Continuing Significance of Racism.” New York: Routledge.

Dyer, R. 1997. White. New York: Routledge.