Translate this page from English...

*Machine translated pages not guaranteed for accuracy. Click Here for our professional translations.

A Brief History of the Idea of Critical Thinking

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Philosophical issues in critical thinking.

- Juho Ritola Juho Ritola University of Turku

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1480

- Published online: 26 May 2021

Critical thinking is active, good-quality thinking. This kind of thinking is initiated by an agent’s desire to decide what to believe, it satisfies relevant norms, and the decision on the matter at hand is reached through the use of available reasons under the control of the thinking agent. In the educational context, critical thinking refers to an educational aim that includes certain skills and abilities to think according to relevant standards and corresponding attitudes, habits, and dispositions to apply those skills to problems the agent wants to solve. The basis of this ideal is the conviction that we ought to be rational. This rationality is manifested through the proper use of reasons that a cognizing agent is able to appreciate. From the philosophical perspective, this fascinating ability to appreciate reasons leads into interesting philosophical problems in epistemology, moral philosophy, and political philosophy.

Critical thinking in itself and the educational ideal are closely connected to the idea that we ought to be rational. But why exactly? This profound question seems to contain the elements needed for its solution. To ask why is to ask either for an explanation or for reasons for accepting a claim. Concentrating on the latter, we notice that such a question presupposes that the acceptability of a claim depends on the quality of the reasons that can be given for it: asking this question grants us the claim that we ought to be rational, that is, to make our beliefs fit what we have reason to believe. In the center of this fit are the concepts of knowledge and justified belief. A critical thinker wants to know and strives to achieve the state of knowledge by mentally examining reasons and the relation those reasons bear to candidate beliefs. Both these aspects include fascinating philosophical problems. How does this mental examination bring about knowledge? What is the relation my belief must have to a putative reason for my belief to qualify as knowledge?

The appreciation of reason has been a key theme in the writings of the key figures of philosophy of education, but the ideal of individual justifying reasoning is not the sole value that guides educational theory and practice. It is therefore important to discuss tensions this ideal has with other important concepts and values, such as autonomy, liberty, and political justification. For example, given that we take critical thinking to be essential for the liberty and autonomy of an individual, how far can we try to inculcate a student with this ideal when the student rejects it? These issues underline important practical choices an educator has to make.

- critical thinking

- rationality

- epistemic justification

- internalism

- public reason

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 04 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.148.24.167]

- 185.148.24.167

Character limit 500 /500

Science and the Spectrum of Critical Thinking

- First Online: 02 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Jeffrey Scheuer 3

Part of the book series: Integrated Science ((IS,volume 12))

1009 Accesses

1 Citations

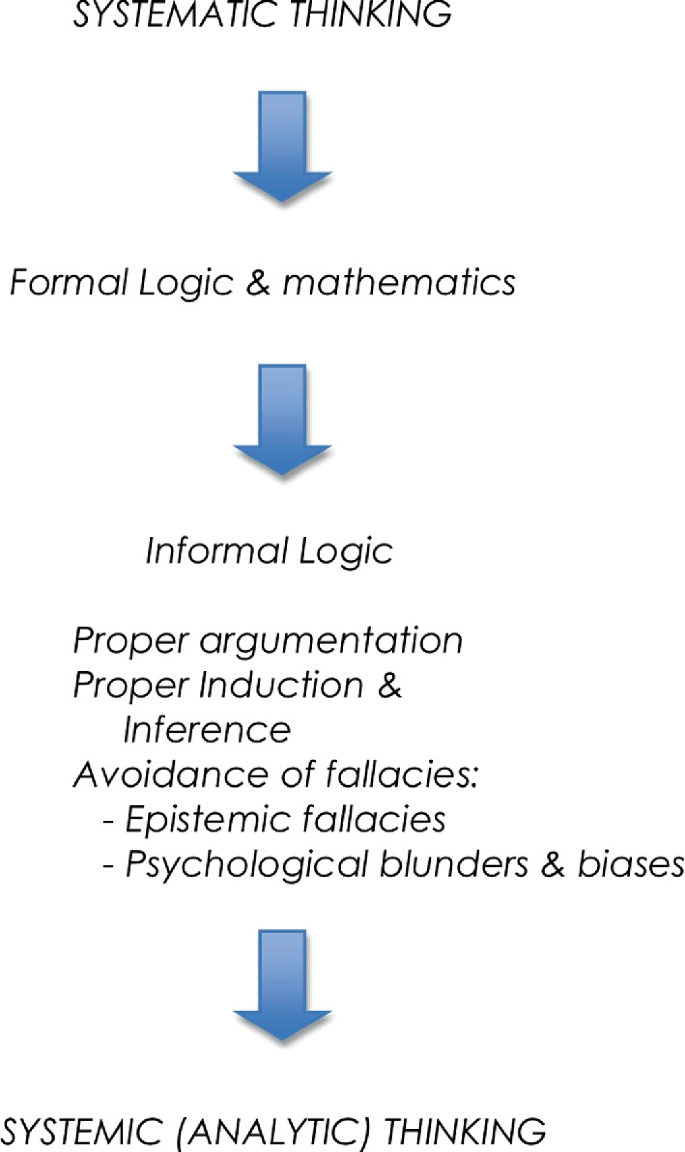

Since the nineteenth century, the scientific method has crystallized as the embodiment of scientific inquiry. But this paradigm of rigor is not confined to the natural sciences, and it has contributed to a sense of scientific “exceptionalism,” which obscures the deep connections between scientific and other kinds of thought. The scientific method has also indirectly given rise to the complex and contested idea of “critical thinking.” Both the scientific method and critical thinking are applications of logic and related forms of rationality that date to the Ancient Greeks. The full spectrum of critical/rational thinking includes logic, informal logic, and systemic or analytic thinking. This common core is shared by the natural sciences and other domains of inquiry share, and it is based on following rules, reasons, and intellectual best practices.

Graphical Abstract/Art Performance

The spectrum of critical thinking.

The term ‘critical thinking ’ is a bit like the Euro: a form of currency that not long ago many were eager to adopt but that has proven troublesome to maintain. And in both cases, the Greeks bear an outsized portion of the blame. Peter Wood [ 1 ]

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Wood P (2012) Some critical thoughts. Chronicle of higher education. chronicle.com/blogs/innovations/some-critical-thoughts/31252/ .

Lepore J (2016) After the fact: in the history of truth, a new chapter begins. The New Yorker, 21 Mar 21, pp 91–94

Google Scholar

Wrightstone JW (1938) Test of critical thinking in the social studies. Bureau of Publications, Teachers College, Columbia University

Novaes CD (2017) What is logic? https://aeon.co/essays/the-rise-and-fall-and-rise-of-logic . Accessed Jan 12, 2017

Williams B (2006) Philosophy as a humanistic discipline

Ferry L (2011) A brief history of thought

Ennis RH (1964) A definition of critical thinking. Read Teach 17(8):599–612

Dobelli R (2013) The art of thinking clearly: better thinking, better decisions. Hachette UK

Phillips DZ (1979) Is moral education really necessary? Br J Educ Stud 27(1):42–56

Article Google Scholar

Kuprenas J, Frederick M (2013) 101 things I learned in engineering school

Grudin R (1997) Time and the art of living. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Bambrough JR (1965) Aristotle on justice: a paradigm of philosophy. In: Bambrough JR (ed) New essays on plato and Aristotle, pp 162–165

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

56 West 10th Street, New York, NY, 10011, USA

Jeffrey Scheuer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jeffrey Scheuer .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Universal Scientific Education and Research Network (USERN), Stockholm, Sweden

Nima Rezaei

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Scheuer, J. (2023). Science and the Spectrum of Critical Thinking. In: Rezaei, N. (eds) Brain, Decision Making and Mental Health. Integrated Science, vol 12. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15959-6_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15959-6_3

Published : 02 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-15958-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-15959-6

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.12: Immanuel Kant’s Critical Philosophy

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 86875

Kant: Synthetic A Priori Judgments

Home the critical philosophy.

Next we turn to the philosophy of Immanuel Kant , a watershed figure who forever altered the course of philosophical thinking in the Western tradition. Long after his thorough indoctrination into the quasi-scholastic German appreciation of the metaphysical systems of Leibniz and Wolff , Kant said, it was a careful reading of David Hume that “interrupted my dogmatic slumbers and gave my investigations in the field of speculative philosophy a quite new direction.” Having appreciated the full force of such skeptical arguments, Kant supposed that the only adequate response would be a “Copernican Revolution” in philosophy, a recognition that the appearance of the external world depends in some measure upon the position and movement of its observers. This central idea became the basis for his life-long project of developing a critical philosophy that could withstand them.

Kant’s aim was to move beyond the traditional dichotomy between rationalism and empiricism. The rationalists had tried to show that we can understand the world by careful use of reason; this guarantees the indubitability of our knowledge but leaves serious questions about its practical content. The empiricists , on the other hand, had argued that all of our knowledge must be firmly grounded in experience; practical content is thus secured, but it turns out that we can be certain of very little. Both approaches have failed, Kant supposed, because both are premised on the same mistaken assumption.

Progress in philosophy, according to Kant, requires that we frame the epistemological problem in an entirely different way. The crucial question is not how we can bring ourselves to understand the world, but how the world comes to be understood by us. Instead of trying, by reason or experience, to make our concepts match the nature of objects, Kant held, we must allow the structure of our concepts shape our experience of objects. This is the purpose of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (1781, 1787): to show how reason determines the conditions under which experience and knowledge are possible.

Home Varieties of Judgment

In the Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysic (1783) Kant presented the central themes of the first Critique in a somewhat different manner, starting from instances in which we do appear to have achieved knowledge and asking under what conditions each case becomes possible. So he began by carefully drawing a pair of crucial distinctions among the judgments we do actually make.

The first distinction separates a priori from a posteriori judgments by reference to the origin of our knowledge of them. A priori judgments are based upon reason alone, independently of all sensory experience, and therefore apply with strict universality. A posteriori judgments, on the other hand, must be grounded upon experience and are consequently limited and uncertain in their application to specific cases. Thus, this distinction also marks the difference traditionally noted in logic between necessary and contingent truths.

But Kant also made a less familiar distinction between analytic and synthetic judgments, according to the information conveyed as their content. Analytic judgments are those whose predicates are wholly contained in their subjects; since they add nothing to our concept of the subject, such judgments are purely explicative and can be deduced from the principle of non-contradiction. Synthetic judgments, on the other hand, are those whose predicates are wholly distinct from their subjects, to which they must be shown to relate because of some real connection external to the concepts themselves. Hence, synthetic judgments are genuinely informative but require justification by reference to some outside principle.

Kant supposed that previous philosophers had failed to differentiate properly between these two distinctions. Both Leibniz and Hume had made just one distinction, between matters of fact based on sensory experience and the uninformative truths of pure reason. In fact, Kant held, the two distinctions are not entirely coextensive; we need at least to consider all four of their logically possible combinations:

- Analytic a posteriori judgments cannot arise, since there is never any need to appeal to experience in support of a purely explicative assertion.

- Synthetic a posteriori judgments are the relatively uncontroversial matters of fact we come to know by means of our sensory experience (though Wolff had tried to derive even these from the principle of contradiction).

- Analytic a priori judgments, everyone agrees, include all merely logical truths and straightforward matters of definition; they are necessarily true.

- Synthetic a priori judgments are the crucial case, since only they could provide new information that is necessarily true. But neither Leibniz nor Hume considered the possibility of any such case.

Unlike his predecessors, Kant maintained that synthetic a priori judgments not only are possible but actually provide the basis for significant portions of human knowledge. In fact, he supposed ( pace Hume) that arithmetic and geometry comprise such judgments and that natural science depends on them for its power to explain and predict events. What is more, metaphysics—if it turns out to be possible at all—must rest upon synthetic a priori judgments, since anything else would be either uninformative or unjustifiable. But how are synthetic a priori judgments possible at all? This is the central question Kant sought to answer.

Home Mathematics

Consider, for example, our knowledge that two plus three is equal to five and that the interior angles of any triangle add up to a straight line. These (and similar) truths of mathematics are synthetic judgments, Kant held, since they contribute significantly to our knowledge of the world; the sum of the interior angles is not contained in the concept of a triangle. Yet, clearly, such truths are known a priori , since they apply with strict and universal necessity to all of the objects of our experience, without having been derived from that experience itself. In these instances, Kant supposed, no one will ask whether or not we have synthetic a priori knowledge; plainly, we do. The question is, how do we come to have such knowledge? If experience does not supply the required connection between the concepts involved, what does?

Kant’s answer is that we do it ourselves. Conformity with the truths of mathematics is a precondition that we impose upon every possible object of our experience. Just as Descartes had noted in the Fifth Meditation, the essence of bodies is manifested to us in Euclidean solid geometry, which determines a priori the structure of the spatial world we experience. In order to be perceived by us, any object must be regarded as being uniquely located in space and time, so it is the spatio-temporal framework itself that provides the missing connection between the concept of the triangle and that of the sum of its angles. Space and time, Kant argued in the “Transcendental Aesthetic” of the first Critique , are the “pure forms of sensible intuition” under which we perceive what we do.

Understanding mathematics in this way makes it possible to rise above an old controversy between rationalists and empiricists regarding the very nature of space and time. Leibniz had maintained that space and time are not intrinsic features of the world itself, but merely a product of our minds. Newton , on the other hand, had insisted that space and time are absolute, not merely a set of spatial and temporal relations. Kant now declares that both of them were correct! Space and time are absolute, and they do derive from our minds. As synthetic a priori judgments, the truths of mathematics are both informative and necessary.

This is our first instance of a transcendental argument , Kant’s method of reasoning from the fact that we have knowledge of a particular sort to the conclusion that all of the logical presuppositions of such knowledge must be satisfied. We will see additional examples in later lessons, and can defer our assessment of them until then. But notice that there is a price to be paid for the certainty we achieve in this manner. Since mathematics derives from our own sensible intuition, we can be absolutely sure that it must apply to everything we perceive, but for the same reason we can have no assurance that it has anything to do with the way things are apart from our perception of them. Next time, we’ll look at Kant’s very similar treatment of the synthetic a priori principles upon which our knowledge of natural science depends.

Home Preconditions for Natural Science

In natural science no less than in mathematics, Kant held, synthetic a priori judgments provide the necessary foundations for human knowledge. The most general laws of nature, like the truths of mathematics, cannot be justified by experience, yet must apply to it universally. In this case, the negative portion of Hume’s analysis—his demonstration that matters of fact rest upon an unjustifiable belief that there is a necessary connection between causes and their effects—was entirely correct. But of course Kant’s more constructive approach is to offer a transcendental argument from the fact that we do have knowledge of the natural world to the truth of synthetic a priori propositions about the structure of our experience of it.

As we saw last time, applying the concepts of space and time as forms of sensible intuition is necessary condition for any perception. But the possibility of scientific knowledge requires that our experience of the world be not only perceivable but thinkable as well, and Kant held that the general intelligibility of experience entails the satisfaction of two further conditions:

First, it must be possible in principle to arrange and organize the chaos of our many individual sensory images by tracing the connections that hold among them. This Kant called the synthetic unity of the sensory manifold.

Second, it must be possible in principle for a single subject to perform this organization by discovering the connections among perceived images. This is satisfied by what Kant called the transcendental unity of apperception. Experiential knowledge is thinkable only if there is some regularity in what is known and there is some knower in whom that regularity can be represented. Since we do actually have knowledge of the world as we experience it, Kant held, both of these conditions must in fact obtain.

Home Deduction of the Categories

Since (as Hume had noted) individual images are perfectly separable as they occur within the sensory manifold, connections between them can be drawn only by the knowing subject, in which the principles of connection are to be found. As in mathematics, so in science the synthetic a priori judgments must derive from the structure of the understanding itself.

Consider, then, the sorts of judgments distinguished by logicians (in Kant ‘s day): each of them has some quantity (applying to all things, some, or only one); some quality (affirmative, negative, or complementary); some relation (absolute, conditional, or alternative); and some modality ( problematic, assertoric, or apodeictic ). Kant supposed that any intelligible thought can be expressed in judgments of these sorts. But then it follows that any thinkable experience must be understood in these ways, and we are justified in projecting this entire way of thinking outside ourselves, as the inevitable structure of any possible experience.

The result of this “Transcendental Logic” is the schematized table of categories, Kant’s summary of the central concepts we employ in thinking about the world, each of which is discussed in a separate section of the Critique :

Our most fundamental convictions about the natural world derive from these concepts, according to Kant. The most general principles of natural science are not empirical generalizations from what we have experienced, but synthetic a priori judgments about what we could experience, in which these concepts provide the crucial connectives.

- The Philosophy Pages. Authored by : Garth Kemerling. Located at : http://www.philosophypages.com/hy/5f.htm . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

Critical Thinking: What is it to be a Critical Thinker?

Author: Carolina Flores Categories: Logic and Reasoning , Philosophy of Education , Epistemology, or Theory of Knowledge Word count: 997

Listen here

We often urge others to think critically. What does that really mean? How can we think critically?

This essay presents a general account of what it is to be a critical thinker and outlines both traditional and more recent approaches to critical thinking.

1. What is Critical Thinking?

Speaking generally, critical thinking consists of reasoning and inquiring in careful ways, so as to form and update one’s beliefs based on good reasons . [1] A critical thinker is someone who typically reasons and inquires in these ways, having mastered relevant skills and developed the disposition to apply them. [2]

2. Traditional Components: Logic and Fallacies

Traditional views of critical thinking focus on deductive arguments. Arguments are sets of reasons given for a conclusion. Deductive arguments are arguments where the reasons given are supposed to be logically conclusive, that is, to guarantee the conclusion. E.g., the following is a deductive argument:

- Socrates is a man.

- All men are mortal.

- Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

Arriving at new beliefs through deductive arguments is a way of forming beliefs based on good reasons. Accordingly, critical thinking traditionally focusses on these skills: [3]

- distinguishing arguments (instances where you are offered reasons for a conclusion) from mere assertions, rhetorical questions, and attempts at manipulation through irrelevant considerations;

- identifying conclusions of arguments (what the person offering the argument wants to persuade you to believe), and the reasons or premises for that conclusion;

- reconstructing streamlined, complete statements of arguments in standard form (as a numbered list of premises with the conclusion at the end), or using diagrams; [4]

- assessing the logical structure of deductive arguments: answering ‘Is there any way for the premises to be true while the conclusion is false?’

- understanding arguments’ claims: e.g., defining unclear terms;

- determining whether premises are true or likely;

- imagining, proposing, and charitably responding to objections, i.e, reasons given to doubt or deny arguments’ logic, premise(s), or conclusion. [5]

To develop these skills, traditional critical thinking courses typically include propositional logic and the study of common good argument forms. [6]

They also often teach how to identify fallacies —faulty patterns of reasoning that deceptively appear to be good arguments. [7] These include:

- affirming the consequent (“If Kat had won the prize, she would have had an A; Kat had an A; therefore, Kat won the prize”);

- the ad hominem fallacy—where people attack the person making an argument instead of considering their argument;

- begging the question —offering reasons for a conclusion that assume the conclusion, and many others. [8]

3. Additional Formal Tools: Evidence and Statistics

We often form beliefs based on observations that, unlike deductive arguments, do not provide conclusive reasons for a belief: e.g., you might conclude that your sibling is angry at you from their facial expressions or come to believe you have a cold because you have a runny nose. Here, these observations or evidence might support the belief formed but do not guarantee the truth of your belief.

Critical thinkers know how to adjust their beliefs appropriately in light of their evidence. [9] So critical thinking requires developing abilities to:

- assess evidence without being unduly swayed by what one already believes;

- recognize when a claim counts as evidence for (or against) a conclusion;

- identify when evidence is strong (or weak);

- determine the extent to which people’s views should change, given their evidence.

To develop these abilities, drawing on knowledge of probability can be helpful: e.g., basic probability offers a recipe for determining when an observation counts as evidence for a belief: when that observation is more likely if the belief is true than if it is not . It also teaches us that updating your beliefs when you get new evidence requires taking into account both (a) how confident you were on that belief beforehand and (b) how strongly the evidence supports that (new) belief. [10]

For these reasons, recent approaches to critical thinking often include instruction in probability. [11] And, because we often get evidence in the form of statistics, often presented through diagrams and graphs, such approaches tend to highlight the importance of basic statistical concepts, [12] and the ability to interpret diagrams and graphs. [13]

4. Applied Skills as Part of Being a Critical Thinker

Being a critical thinker requires more than having technical tools (such as the tools of logic or probability) stored away. It requires consistently applying them in the real world .

In recent discussions of what it is to be a critical thinker, there has been increased emphasis on navigating our informational environments in savvy ways. This requires avoiding false, misleading, manipulative, or distracting claims online, as well as making sure that one gathers information from a wide variety of reliable sources. [14] It also requires calibrating one’s trust well: one should remain open to hearing those who disagree and not let prejudice and implicit bias affect whom one trusts. [15] , [16]

Applying the tools of critical thinking throughout one’s life requires overcoming cognitive biases: [17] e.g.:

- not always accepting answers that come to mind first;

- resisting confirmation bias (the tendency to gather and interpret evidence in ways that confirm our beliefs), [18] and;

- avoiding motivated reasoning (the tendency to reason in ways that help us believe what we wish were true, and not what is true). [19]

More generally, becoming a critical thinker requires shifting from a defensive mindset to a truth-seeking one and developing intellectual virtues such as intellectual humility and open-minded curiosity. [20] , [21] Without those, the tools of critical thinking may end up being deployed to entrench false or unreasonable beliefs.

5. Conclusion

Critical thinking is about reasoning and inquiring so as to form and update one’s beliefs based on good reasons. Because critical thinking skills are valuable in a world that emphasizes the ability to navigate information, becoming a critical thinker is practically useful to us as individuals.

It is also of crucial social and political value: e.g., a well-functioning democracy requires citizens who think critically about the world. [22] And critical thinking has liberatory potential: it provides us with tools to criticize oppressive social structures and envisage a more just, fair society. [23]

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Teaching Philosophy Facebook Group for literature recommendations. Thanks to Chelsea Haramia, Sabrina Huwang, Izilda Jorge, Thomas Metcalf, Nathan Nobis, Elise Woodard, and anonymous referees for feedback.

[1] This definition is similar to Ennis’s (1991) definition: critical thinking, in his view, is “reasonable reflective thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do” (Ennis 1991, p. 6). See Hitchcock 2010 for an overview of definitions of critical thinking.

[2] While I define critical thinking in a general way here, there is disagreement about whether there are any general tools for critical thinking, as opposed to merely topic-specific ones.

There are also closely related debates about the extent to which specific critical thinking skills transfer to new domains and tasks, and about whether we should teach critical thinking on its own or, instead, in the context of specific disciplines, with discipline-internal standards made clear and an emphasis on content acquisition. See Willingham 2019 for discussion, including references to relevant empirical research.

People who have mastered critical thinking skills in a domain or subject area tend to be experts in those areas. See Expertise: What is an Expert? by Jamie Carlin Watson

[3] See this Khan Academy/Wi Phi Philosophy course for an overview.

[4] An example of an argument in standard form is: 1. Socrates is a man; 2. All men are mortal; 3. Therefore, Socrates is mortal. For other examples of arguments in standard form, see Anderson’s “Putting an Argument in Standard Form.” For examples of argument diagrams, as well as a useful program to construct such diagrams, see Cullen’s “Philosophy Mapped” website .

[5] Charitably responding involves responding to the strongest version of the objection.

[6] Propositional logic is the simplest branch of logic, i.e. the formal study of arguments and reasoning. See Tom Metcalf’s Formal Logic: Symbolizing Arguments in Sentential Logic by for an introduction.

[7] Wikipedia has extensive lists of good argument forms and of common fallacies . See Boardman et al. 2017, Howard-Snyder 2020, Lau 2011 , Vaughn 2018 for examples of critical thinking textbooks that take the traditional approach.

[8] To see why these are fallacies, note that, for all that is said, Kat could have had an A without winning the prize; perhaps she simply had high exam scores. And note that morally bad people can give good arguments.

[9] Philosophers also use the term ‘evidence’ in more technical senses than ‘relevant observations’. See Kelly 2016 for discussion of these different senses.

[10] Indeed, we can capture this insight into a domain-general formula for how to update beliefs: Bayes’ theorem. Bayes’ theorem tells us how to weigh our previous confidence and the strength of evidence. For a short explanation of Bayes’ Theorem, see Better Explained, “A Short and Intuitive Explanation of Bayes’ Theorem” . For more detailed discussion of Bayesianism, see Joyce 2019.

[11] Manley 2019.

[12] See Gigerenzer et al. 2007 for discussion of the practical importance of these concepts. An especially important statistical concept is that of base rate . The base rate of a feature in a population is what fraction of the population have that feature. Neglecting the base rate leads to the base rate fallacy , where one ends up adjusting one’s beliefs incorrectly in response to evidence (for example, taking a fallible positive test for a rare disease to indicate that one is extremely likely to have that disease, where, given the rarity of the disease, that remains unlikely).

[13] Battersby 2016.

[14] See Bergstorm and West’s “Calling Bullshit” syllabus for a range of helpful tools for avoiding such claims, and The News Literacy Project for resources on developing a healthy news diet.

[15] See Nguyen’s “Escape the Echo Chamber.” for helpful discussion of common issues with trust calibration and with information gathering.

[16] Implicit bias involves believing and acting “on basis of prejudice and stereotypes without intending to do so”: see Brownstein 2019.

When one discredits members of marginalized groups due to (conscious or unconscious) prejudice, one commits an epistemic injustice: see Fricker 2007. For an introduction to epistemic injustice, see Huzeyfe Demitras’s Epistemic Injustice .

[17] Cognitive biases are systematic deviations from how we should reason. See Kahneman 2011 for an accessible overview of research on cognitive biases.

[18] Nickerson 1998 .

[19] Kunda 1990.

[20] An intellectual virtue is a personality trait or disposition that is helpful in reasoning well and acquiring knowledge. Some examples are intellectual humility, open-mindedness, curiosity, and perseverance. See Zagzebski 1996.

[21] See Galef’s TED talk “Why you think you’re right – even if you’re wrong” for discussion of the importance of these traits.

[22] Dewey 1923.

[23] Freire 1968/2018, hooks 2010.

Anderson, Jeremy. “Putting an Argument in Standard Form.”

Battersby, Mark. 2016. Is That a Fact?: A Field Guide to Statistical and Scientific Information . Broadview Press.

Bergstrom, Carl T. and West, Jevin. 2019. “Calling Bullshit: Data Reasoning in a Digital World.” (website)

Better Explained. 2020. “A Short and Intuitive Explanation of Bayes’ Theorem.” (website)

Boardman, Frank, Cavender, Nancy M, and Kahane, Howard . 2017. Logic and Contemporary Rhetoric: The Use of Reason in Everyday Life. Cengage Learning.

Brownstein, Michael, “Implicit Bias”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

Cullen, Simon. “Philosophy Mapped: Open Resources for Philosophy Visualization.”

Demirtas, Huzeyfe. 2020. “Epistemic Injustice.” 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology .

Dewey, John. 1923. Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. Macmillan.

Ennis, Robert. 1991. “Critical Thinking: A Streamlined Conception.” Teaching Philosophy , 14(1):5-24.

Frankfurt, Harry G. 1986. On Bullshit . Princeton University Press.

Freire, Paulo. 2018 [1968]. Pedagogy of the Oppressed . Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Fricker, Miranda. 2007. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing . Oxford University Press.

Galef, Julia. 2016. “Why You Think You’re Right – Even If You’re Wrong.” TED Talk.

Gigerenzer, Gerd, Gaissmaier, Wolfgang, Kurz-Milcke, Elke, Schwartz, Lisa M and Woloshin, Steven. 2007. “Helping Doctors and Patients Make Sense of Health Statistics.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest , 8(2):53-96.

bell hooks. 2010. Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom . New York and London: Routledge.

Hitchcock, David. 2020. “ Critical Thinking ” , The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

Howard-Snyder, Frances, Howard-Snyder, Daniel, and Wasserman, Ryan. 2020. The Power of Logic . McGraw-Hill.

Joyce, James, “ Bayes’ Theorem ” , The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow . Macmillan.

Kelly, Thomas. 2016. “ Evidence ” , The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

Kunda, Ziva. 1990. “The Case for Motivated Reasoning.” Psychological Bulletin , 108(3): 480-498.

Lai, Emily R. 2011. “Critical Thinking: A Literature Review.” Pearson’s Research Reports , 6: 40-41.

Lau, Joe YF. 2011. An Introduction to Critical Thinking and Creativity: Think More, Think Better . John Wiley & Sons.

Manley, David. 2019. Reason Better: An Interdisciplinary Guide to Critical Thinking . Toronto, ON, Canada: Tophat Monocle.

Metcalf, Thomas. 2020. “Formal Logic: Symbolizing Arguments in Sentential Logic.” 1,000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology .

The News Literacy Project.

Nguyen, Thi. 2018. “Escape the Echo Chamber.” Aeon.

Nickerson, Raymond S. 1998. “Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises.” Review of General Psychology , 2(2):175-220.

Pynn, Geoff. 2020. “Critical Thinking: Fundamentals.” Wireless Philosophy/Khan Academy .

Vaughn, Lewis. 2018. The Power of Critical Thinking: Effective Reasoning About Ordinary and Extraordinary Claims . Oxford University Press.

Willingham, Daniel T. 2019. “How to Teach Critical Thinking.” Education: Future Frontiers , 1:1-17.

Zagzebski, Linda Trinkaus. 1996. Virtues of the Mind: An Inquiry into the Nature of Virtue and the Ethical Foundations of Knowledge . Cambridge University Press.

Related Essays

Arguments: Why Do You Believe What You Believe? by Thomas Metcalf

Classical Syllogisms by Timothy Eshing

Contemporary Syllogisms by Timothy Eshing

Philosophy as a Way of Life by Christine Darr

Expertise by Jamie Carlin Watson

Epistemic Justification: What is Rational Belief? by Todd R. Long

Is it Wrong to Believe Without Sufficient Evidence? W.K. Clifford’s “The Ethics of Belief” by Spencer Case

Indoctrination: What is it to Indoctrinate Someone? by Chris Ranalli

Epistemic Injust ice by Huzeyfe Demitras

Formal Logic: Symbolizing Arguments in Sentential Logic by Thomas Metcalf

Epistemology, or Theory of Knowledge by Thomas Metcalf

Bayesianism by Thomas Metcalf

Conspiracy Theories by Jared Millson

Philosophical Inquiry in Childhood by Jana Mohr Lone

Translation

Pdf download.

Download this essay in PDF .

About the Author

Carolina Flores is a post-doctoral fellow at UC Irvine and will be an assistant professor at UC Santa Cruz starting in 2023. She earned her Ph.D. at Rutgers University, New Jersey. She specializes in philosophy of mind and social epistemology. She is especially interested in why it is so hard to change people’s minds, and in what that tells us about the mind and about human relationships and political persuasion. CarolinaFlores.org

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook , Twitter and subscribe to receive email notifications of new essays at 1000WordPhilosophy.com.

Share this:

12 thoughts on “ critical thinking: what is it to be a critical thinker ”.

- Pingback: 비판적 사고: 비판적으로 사고한다는 것은 무엇일까? – Carolina Flores - Doing Philosophy

- Pingback: Philosophy as a Way of Life – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Epistemic Justification: What is Rational Belief? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Arguments: Why Do You Believe What You Believe? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Contemporary Syllogisms – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Classical Syllogisms – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Formal Logic: Symbolizing Arguments in Quantificational or Predicate Logic – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Bayesianism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Is it Wrong to Believe Without Sufficient Evidence? W.K. Clifford’s “The Ethics of Belief” – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Indoctrination: What is it to Indoctrinate Someone? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Cultural Relativism: Do Cultural Norms Make Actions Right and Wrong? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: What is Philosophy? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Comments are closed.

Introduction

Chapter outline.

You have likely heard the term “critical thinking” and have probably been instructed to become a “good critical thinker.” Unfortunately, you are probably also unclear what exactly this means because the term is poorly defined and infrequently taught. “But I know how to think,” you might say, and that is certainly true. Critical thinking , however, is a specific skill. This chapter is an informal and practical guide to critical thinking and will also guide you in how to conduct research, reading, and writing for philosophy classes.

Critical thinking is set of skills, habits, and attitudes that promote reflective, clear reasoning. Studying philosophy can be particularly helpful for developing good critical thinking skills, but often the connection between the two is not made clear. This chapter will approach critical thinking from a practical standpoint, with the goal of helping you become more aware of some of the pitfalls of everyday thinking and making you a better philosophy student.

While you may have learned research, reading, and writing skills in other classes—for instance, in a typical English composition course—the intellectual demands in a philosophy class are different. Here you will find useful advice about how to approach research, reading, and writing in philosophy.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Nathan Smith

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Philosophy

- Publication date: Jun 15, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/2-introduction

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Critical Thinking

I. definition.

Critical thinking is the ability to reflect on (and so improve ) your thoughts, beliefs, and expectations. It’s a combination of several skills and habits such as:

Curiosity : the desire for knowledge and understanding

Curious people are never content with their current understanding of the world, but are driven to raise questions and pursue the answers. Curiosity is endless — the better you understand a given topic, the more you realize how much more there is to learn!

Humility : or the recognition that your own understanding is limited

This is closely connected to curiosity — if you’re arrogant and think you know everything already, then you have no reason to be curious. But a humble person always recognizes the limitations and gaps in their knowledge . This makes them more receptive to information, better listeners and learners.

Skepticism : a suspicious attitude toward what other people say

Skepticism means you always demand evidence and don’t simply accept what others tell you. At the same time, skepticism has to be inwardly focused as well! You have to be equally skeptical of your own beliefs and instincts as you are of others’.

Rationality or logic: The formal skills of logic are indispensable for critical thinkers

Skepticism keeps you on the lookout for bad arguments, and rationality helps you figure out exactly why they’re bad. But rationality also allows you to identify good arguments when you see them, and then to move beyond them and understand their further implications.

Creativity: or the ability to come up with new combinations of ideas

It’s not enough to just be skeptical and knock the holes in every argument that you hear. Sooner or later you have to come up with your own ideas, your own solutions, and your own visions. That requires a creative and independent mind, but one that is also capable of listening and learning.

Empathy : the ability to see things from another person’s perspective

Too often, people talk about critical thinkers as though they’re solitary explorers, forging their own path through the jungle of ideas without help from others. But this isn’t true at all. Real critical thinking means you constantly engage with other people, listen to what they have to say, and try to imagine how they see the world. By seeing things from someone else’s perspective, you can generate far more new ideas than you could by relying on your own knowledge alone.

II. Examples

Although video games are sometimes simply a passive way to enjoy yourself, they sometimes rely on critical thinking skills. This is particularly true of puzzle games and role playing games (RPGs) that present your character with puzzles at critical moments. For example, at one stage in the classic RPG Neverwinter Nights , your character has the option to serve as a juror on another character’s trial. In order to save the innocent man, you have to talk to people throughout the town and, using a combination of empathy and skepticism, figure out what really happened.

In one episode of South Park , Cartman becomes obsessed with conspiracy theories and sings a song about needing to think for himself and find out the truth. The show is poking fun at conspiracy theorists, who often think that they are exercising critical thinking when in fact they are simply exercising too much skepticism towards common sense and popular beliefs, and not enough skepticism towards new, unnecessarily complicated explanations.

III. Critical Thinking vs. Traditional Thinking

Critical thinking, in the history of modern Western thought, is strongly associated with the Enlightenment, the period when European and American philosophers decided to approach the world with a rational eye, rejecting blind faith and questioning traditional authority. It was this moment in history that gave us modern medicine, democracy , and the early forms of industrial technology.

At the same time, the Enlightenment also came with many downsides, particularly the fact that it was so hostile to tradition. This hostility is understandable given the state of Europe at the time — ripped apart by bloody conflict between different religions, and oppressed by traditional monarchs who rooted their power in that of the Church. Enlightenment thinkers understandably rejected traditional thinking, holding it responsible for all this violence and injustice. But still, the Enlightenment sometimes went too far in the opposite direction. After all, rejecting tradition just for the sake of rejecting it is not really any better than accepting tradition just for the sake of accepting it! Traditions provide valuable resources for critical thinking, and without them it would be impossible. Think about this: the English language is a tradition, and without it you wouldn’t be sitting there reading these (hopefully useful) words about critical thinking!

So critical thinking absolutely depends on traditions. There’s no question that critical thinking means something more than just accepting traditions; but it doesn’t mean you necessarily reject them, either. It just means that you’re not blindly following tradition for its own sake ; rather, your relationship to your tradition is based on humility, creativity, skepticism, and all the other attributes of critical thinking.

IV. Quotes about Critical Thinking

“If I have seen further than others, it is because I have stood on the shoulders of giants.” (Isaac Newton)

Until Einstein, no physicist was ever more influential than Isaac Newton. Through curiosity and probable skepticism, he not only worked out the basic rules for matter and energy in the universe — he also realized that the force causing objects to fall was the same as the force causing celestial objects to orbit around each other (thus discovering the modern theory of gravity). He was also known for having a big ego and being a little arrogant with those he considered beneath his intellect — but even Newton had enough humility to recognize that he wasn’t doing it alone. He was deeply indebted to the whole tradition of scientists that had come before him — Europeans, Greeks, Arabs, Indians, and all the rest.

“It seems to me what is called for is an exquisite balance between two conflicting needs: the most skeptical scrutiny of all hypotheses… and at the same time a great openness to new ideas. Obviously those two modes of thought are in some tension. But if you are able to exercise only one of these modes, whichever one it is, you’re in deep trouble.” (Carl Sagan, The Burden of Skepticism )

In this quote, Carl Sagan offers a sensitive analysis of a tension within the idea of critical thinking. He points out that skepticism is extremely important to critical thinking, but at the same time it can go too far and become an obstacle. Notice, too, that you could replace the word “new” with “old” in this quote and it would still make sense. Critical thinkers need to be both open to new ideas and skeptical of them; similarly, they need to have a balanced attitude toward old and traditional ideas as well.

V. The History and Importance of Critical Thinking

Critical thinking has emerged as a cultural value in various times and places, from the Islamic scholars of medieval Central Asia to the secular philosophers of 18th-century America or the scientists and engineers of 21st-century Japan. In each case, critical thinking has taken a slightly different form, sometimes emphasizing skepticism above the other dimensions (as occurred in the European Enlightenment), sometimes emphasizing other dimensions such as creativity or rationality.

Today, many leaders in science, education, and business worry that we are seeing a decline in critical thinking. Education around the world has turned increasingly toward standardized testing and the mechanical memorization of facts, an approach that doesn’t leave time for critical thinking or creative arts. Some politicians view critical and creative education as a waste of time, believing that education should only focus on job skills and nothing else — an attitude which clearly overlooks the fact that critical thinking is an important job skill for everyone from auto mechanics to cognitive scientists.

a. Creativity

b. Skepticism

d. These are all dimensions of critical thinking

a. They are opposites

b. They are synonyms

c. They are in tension, but not incompatible

d. None of the above

a. The Enlightenment

b. The Renaissance

c. The current era

d. All of the above

a. Being constantly skeptical

b. Not being skeptical

c. Having a balance between too much skepticism and too little

d. No relation to skepticism

- Search Search Search …

- Search Search …

Philosophy Behind Critical Thinking: A Concise Overview

The philosophy behind critical thinking delves into the deeper understanding of what it means to think critically and to develop the ability to reason, analyze, and evaluate information in a structured and systematic manner. Critical thinking has intricate connections with philosophy, mainly because it originated from ancient philosophical teachings. At its core, the concept of critical thinking is rooted in the Socratic method of questioning, which emphasizes the importance of inquiry and rational thinking as a means to achieve knowledge.

Understanding critical thinking necessitates exploring the various philosophical groundings, which delves into epistemology, the branch of philosophy that deals with knowledge, truth, and belief. Epistemological theories help elucidate different approaches to critical thinking, such as the psychological approach, focusing on cognitive processes, and the cultural and social context approach, emphasizing the importance of context in shaping critical thought. In the realm of education, the role of critical thinking cannot be understated, as it is a vital component of teaching and learning, shaping the way individuals process and interpret information and develop intellectually.

Key Takeaways

- Critical thinking is deeply rooted in ancient philosophical teachings, particularly the Socratic method of questioning.

- Different philosophical groundings provide varying approaches to critical thinking, such as psychological and cultural/social context approaches.

- The importance of critical thinking in education is paramount, as it shapes how individuals process, interpret, and develop intellectually.

Understanding Critical Thinking

Definition and Process

Critical thinking is the ability to think clearly and rationally about what to do or what to believe. It involves engaging in reflective and independent thinking . To understand the logical connections between ideas, one needs to identify, construct, and evaluate arguments.

Logic, Reason, Rationality

Logic, reason, and rationality are essential components of critical thinking. Logic refers to the systematic approach to reasoning and validating claims through principles and rules. Reasoning, on the other hand, is the process of drawing conclusions based on logic, evidence, and assumptions. Rationality encompasses the use of logic and reason to make well-informed decisions, judgments, and evaluations.

Strategies and Patterns

To develop critical thinking skills, individuals must employ various strategies and recognize patterns in their thinking. Some common strategies include:

- Analysis : Breaking down complex problems, data, or texts into simpler parts to understand what they mean and explain the implications to others.

- Interpretation : Making sense of information and grasping its relevance in a given context.

- Inference : Drawing reasonable conclusions based on available evidence and logic.

- Evaluation : Assessing the credibility and validity of claims, arguments, or sources of information.

Recognizing patterns in thinking involves identifying common errors, biases, and other factors that might hinder critical thinking and refining one’s thought process accordingly.

Justification and Argumentation

Justification and argumentation play a crucial role in critical thinking. Justification refers to providing reasons or evidence in support of a claim, while argumentation involves constructing and evaluating arguments . Both justification and argumentation require logical reasoning, analysis of evidence, and clear communication of ideas.

Clarity and Reflection

Clarity is essential for effective critical thinking. This entails expressing ideas and arguments in a clear, concise, and organized manner. Furthermore, critical thinkers must also engage in reflection — the process of examining their own thought processes, assumptions, and biases. Reflecting on one’s beliefs and values helps individuals refine their thinking and develop a more nuanced understanding of the world around them.

In conclusion, understanding critical thinking involves exploring its definition, process, and key components, such as logic, reason, rationality, strategies, patterns, justification, argumentation, clarity, and reflection. By cultivating a strong foundation in these areas, individuals can develop their ability to think critically and make well-informed decisions in various aspects of life.

Psychological Approach to Critical Thinking

Cognition and Pattern Recognition

The psychological approach to critical thinking emphasizes the role of cognition and pattern recognition in the process. Cognitive psychologists recognize that our minds have a natural ability to identify patterns and relationships in the information we encounter. This involves categorizing, comparing, and evaluating various pieces of information. By developing cognitive skills, individuals can more effectively analyze and evaluate complex arguments, ultimately fostering their critical thinking abilities.

Bias and Judgments

Another aspect of the psychological approach to critical thinking is the examination of biases and judgments. Bias refers to the systematic errors or distortions in human reasoning that can arise from emotions, beliefs, or external factors. When individuals possess a strong bias, it can impede their ability to think critically and accurately evaluate information. By being aware of these biases and actively seeking to minimize their influence, one can improve their critical thinking skills and make more accurate judgments.

Problem-Solving and Decision-Making

Finally, the psychological approach to critical thinking also emphasizes the importance of problem-solving and decision-making abilities. Effective problem-solving is accomplished by identifying the problem, gathering and evaluating relevant information, and formulating potential solutions. Strong decision-making skills involve comparing potential solutions and selecting the most effective one based on logical reasoning and evidence.

In conclusion, the psychological approach to critical thinking focuses on fostering cognitive skills, identifying and minimizing biases, and developing strong problem-solving and decision-making abilities. By enhancing these aspects, individuals can become more effective critical thinkers and make well-informed decisions throughout their lives.

Philosophical Groundings

Roots of critical thought.

The roots of critical thought can be traced back to ancient Greek philosophy, particularly the ideas developed by Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. In their teachings, these philosophers emphasized the importance of questioning and examining beliefs, seeking evidence, and evaluating arguments logically. Through these pursuits, they laid a strong foundation for the development of critical thinking in modern times.

Major Philosophers and Approaches

Several major philosophers and their approaches have significantly contributed to the evolution of critical thinking. Among them, Socrates’ method of inquiry, known as the Socratic Method, involves continuous questioning and probing for deeper understanding. Plato, a student of Socrates, focused on the power of dialectical reasoning, urging individuals to engage in dialogue and debate to examine their own beliefs and the beliefs of others.

Aristotle contributed to critical thinking by emphasizing the importance of logic and coherent reasoning to gain knowledge. He also explored rhetoric, expounding on its role in persuasive argumentation. In more recent times, figures such as John Dewey and Karl Marx have provided insights into the role of critical thinking in education and social transformation.

Informal Logic and its Importance

Informal logic plays a crucial role in critical thinking as it concerns the principles and methods used to analyze everyday arguments and reasoning beyond the scope of formal logic. It complements formal logic, which deals strictly with logical systems and symbols. Informal logic helps individuals assess the validity, soundness, and context of arguments encountered in daily life. By honing their skills in informal logic, individuals can become better critical thinkers and more adept at navigating complex situations and decision-making processes.

Through the teachings of philosophers like Plato, Aristotle, and Socrates, as well as the application of informal logic and logical reasoning, the concept of critical thinking has evolved into an essential aspect of learning and decision-making in modern society. Embracing these foundational elements can empower individuals to develop the skills necessary to think critically and effectively in various aspects of life.

Critical Thinking in Cultural and Social Context

Race and gender perspectives.

Critical thinking is a universal skill that transcends cultural and social boundaries. However, it is essential to consider the impact of race and gender on the development and exercise of critical thinking skills. People from marginalized groups may experience unique challenges and perspectives that influence their critical thinking abilities. For example, in a cross-cultural study examining critical thinking among nurse scholars in Thailand and the United States, distinctive perspectives on critical thinking were observed due to cultural differences. Understanding the intersections of race, gender, and critical thinking can help create more inclusive education and workplace environments that foster critical thinking for everyone.

Critical Thinking in a Democratic Society

In a democratic society, critical thinking plays a crucial role in informed decision-making, civic engagement, and open discussion. The healthy functioning of a democracy relies on the citizens’ capacity to discern reliable information, assess arguments, and make rational choices. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , critical thinking includes abilities and dispositions that lead individuals to think critically when appropriate. Developing these skills allows members of democratic societies to engage in productive debates, evaluate policies, and hold leaders accountable.

Culture, Society, and Critical Thinking

Cultural backgrounds and societal norms can significantly impact how individuals approach critical thinking. Different cultures may emphasize various ways of thinking, problem-solving, and expressing ideas. As a result, critical thinking can manifest differently across cultures, often influenced by aspects such as language, traditions, and values. A study discussing critical thinking in its historical and social contexts highlights the importance of considering cultural influences when evaluating and teaching critical thinking.

In summary, critical thinking is an essential skill across various cultural, racial, gender, and social contexts. By acknowledging these differences and understanding the significance of critical thinking in democratic societies, educators and societies can promote a more inclusive environment for cultivating critical thinking skills.

Role of Critical Thinking in Education

Aims of education.

The primary aim of education is to foster the development of individuals’ cognitive capabilities, empowering them to grow into confident, knowledgeable and discerning adults. Critical thinking plays a significant role in education as it helps students acquire and apply knowledge more effectively, by analyzing, evaluating, and synthesizing information from diverse sources in a systematic manner, leading to more accurate and informed decisions.

In addition, critical thinking allows students to question existing knowledge and challenge conventional wisdom, thus avoiding indoctrination and promoting intellectual independence. This helps in nurturing open-minded and critical citizens who can contribute positively to society.

Skills Development

Critical thinking involves a variety of skills and abilities that are essential for students’ personal and professional success. These include problem-solving, decision making, logical reasoning, and effective communication, among others. By teaching these skills in the classroom, educators enable learners to confront complex issues and dilemmas with confidence and clarity, fostering their cognitive, social, and emotional growth.

Classroom activities focused on critical thinking are essential to help students develop a systematic approach to problem-solving and sharpen their analytical skills. Practical tasks, like debates, group discussions, case studies, or role plays, can be employed to engage students in active learning, thus enhancing their critical thought processes.

Standardized Tests vs. Critical Thought

While standardized tests have dominated the contemporary education system, there is growing concern regarding their effectiveness in promoting critical thinking. Some argue that standardized tests prioritize the acquisition of specific knowledge over the development of essential skills and abilities, leading to an education that is more focused on rote memorization than meaningful learning.

However, introducing critical thinking elements in the curriculum or classroom activities does not require a complete removal of standardized tests. Educators can strike a balance between knowledge acquisition and skill development by incorporating critical thinking exercises in conjunction with traditional assessments. In doing so, students can better prepare for life beyond the classroom, developing a mindset that values continuous learning, reflection, and intellectual curiosity.

Importance of Open-Mindedness and Skepticism

Being skeptical vs. being cynical.

It is essential to understand the difference between being skeptical and being cynical. Skepticism in critical thinking involves questioning assertions and assumptions, seeking evidence, and evaluating arguments from a neutral, objective viewpoint. On the other hand, cynicism is a distrustful attitude, where one assumes negative intentions or outcomes.

A critical thinker should strive to be skeptical rather than cynical. Approaching situations with skepticism allows for the exploration of different viewpoints and the willingness to change one’s mind based on new evidence, while cynicism can lead to the dismissal of valid arguments due to preconceived negative beliefs.

Traits of an Open-Minded Thinker

Open-mindedness is an essential trait for critical thinkers. Some key characteristics of an open-minded thinker include:

- Cognitive flexibility : Adapting to and considering new information or perspectives.

- Tolerance for ambiguity : Accepting the possibility that there may be multiple valid solutions or interpretations.

- Willingness to change : Being open to revising beliefs and opinions when presented with strong evidence or arguments.

Being open-minded allows critical thinkers to explore various perspectives and ideas and to evaluate them fairly. This inclination towards cognitive flexibility helps in avoiding rigidity in thinking, enabling better decision-making and problem-solving.

Role of Curiosity and Empathy in Critical Thinking

Curiosity and empathy play crucial roles in effective critical thinking. A curious individual seeks knowledge and understanding, thus asking relevant questions and engaging in Socratic questioning. Socratic questioning is a method of probing and analyzing through questions to encourage self-reflection and deeper understanding. This technique fosters critical thinking by challenging assumptions and providing opportunities to explore diverse viewpoints.

Empathy, on the other hand, permits critical thinkers to comprehend and appreciate different perspectives by placing themselves in others’ shoes. An empathetic approach contributes to open-mindedness and cultivates a sense of humility, recognizing that individuals may hold contrasting opinions based on personal experiences or beliefs. The combination of curiosity and empathy enhances critical thinking by promoting a more inclusive and nuanced understanding of complex issues and scenarios.

In the realm of philosophy, critical thinking holds a prominent position. It is a process that revolves around using and assessing reasons to evaluate statements, assumptions, and arguments in ordinary situations. The ultimate goal of critical thinking is to foster good beliefs, aligning them with goals such as truth, usefulness, and rationality 1 .

John Dewey played a crucial role in shaping the concept of critical thinking by introducing it as an educational goal 2 . He connected it with a scientific attitude of mind, highlighting the importance of reflective thought in the process of critical thinking. This approach enhances one’s ability to understand and analyze situations, leading to informed and rational decisions.

Critical thinking equips individuals with the tools necessary to think carefully with clarity, depth, precision, accuracy, and logic 3 . It has applications across various domains, such as science, where great scientists like Albert Einstein have benefited from critical thinking skills to discover groundbreaking concepts.

In conclusion, the philosophy behind critical thinking emphasizes the importance of cultivating a rational and reflective mindset. As an essential skill for problem-solving and decision-making, critical thinking plays a vital role in developing well-rounded individuals ready to navigate the complexities of the world.

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy ↩

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy ↩

- SlideShare ↩

You may also like

Best Children’s Books on Critical Thinking: Top Picks for Young Minds in 2023

Introducing children to critical thinking at an early age is essential for their cognitive development. Engaging in thought-provoking activities not only helps […]

The Role of Critical Thinking in Modern Business: Enhancing Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

In today’s fast-paced and complex business landscape, the ability to think critically has become increasingly important. Critical thinking skills are essential to […]

What is Critical Thinking?

Critical Thinking: Its Definition, Applications, Elements and Processes Experts and educators argue on the definition of critical thinking for centuries. No matter […]

Unleash Your True Mental Power with These 10 Critical Thinking Habits

Critical thinking is an extremely useful skill no matter where you are in life. Whether you are with the top decision-making bodies […]

Philosophical Issues in Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is active, good-quality thinking. This kind of thinking is initiated by an agent’s desire to decide what to believe, it satisfies relevant norms, and the decision on the matter at hand is reached through the use of available reasons under the control of the thinking agent. In the educational context, critical thinking refers to an educational aim that includes certain skills and abilities to think according to relevant standards and corresponding attitudes, habits, and dispositions to apply those skills to problems the agent wants to solve. The basis of this ideal is the conviction that we ought to be rational. This rationality is manifested through the proper use of reasons that a cognizing agent is able to appreciate. From the philosophical perspective, this fascinating ability to appreciate reasons leads into interesting philosophical problems in epistemology, moral philosophy, and political philosophy. Critical thinking in itself and the educational ideal are closely connected to the idea that we ought to be rational. But why exactly? This profound question seems to contain the elements needed for its solution. To ask why is to ask either for an explanation or for reasons for accepting a claim. Concentrating on the latter, we notice that such a question presupposes that the acceptability of a claim depends on the quality of the reasons that can be given for it: asking this question grants us the claim that we ought to be rational, that is, to make our beliefs fit what we have reason to believe. In the center of this fit are the concepts of knowledge and justified belief. A critical thinker wants to know and strives to achieve the state of knowledge by mentally examining reasons and the relation those reasons bear to candidate beliefs. Both these aspects include fascinating philosophical problems. How does this mental examination bring about knowledge? What is the relation my belief must have to a putative reason for my belief to qualify as knowledge? The appreciation of reason has been a key theme in the writings of the key figures of philosophy of education, but the ideal of individual justifying reasoning is not the sole value that guides educational theory and practice. It is therefore important to discuss tensions this ideal has with other important concepts and values, such as autonomy, liberty, and political justification. For example, given that we take critical thinking to be essential for the liberty and autonomy of an individual, how far can we try to inculcate a student with this ideal when the student rejects it? These issues underline important practical choices an educator has to make.

- Related Documents

Open-Mindedness, Critical Thinking, and Indoctrination

William Hare has made fundamental contributions to philosophy of education. His work on various matters of educational theory and practice is of the first importance and will influence the field for decades to come. Among the most important of these contributions is his hugely important work on open-mindedness, an ideal that Hare has clarified and defended powerfully and tellingly. In this paper I explore the several relationships that exist between Hare’s favored educational ideal (open-mindedness) and my own (critical thinking). Both are important educational aims, but I argue here that while both are of central importance, it is the latter that is the more fundamental of the two.

Education's Epistemology

This collection extends and further defends the “reasons conception” of critical thinking that Harvey Siegel has articulated and defended over the last three-plus decades. This conception analyzes and emphasizes both the epistemic quality of candidate beliefs, and the dispositions and character traits that constitute the “critical spirit”, that are central to a proper account of critical thinking; argues that epistemic quality must be understood ultimately in terms of epistemic rationality; defends a conception of rationality that involves both rules and judgment; and argues that critical thinking has normative value over and above its instrumental tie to truth. Siegel also argues, contrary to currently popular multiculturalist thought, for both transcultural and universal philosophical ideals, including those of multiculturalism and critical thinking themselves. Over seventeen chapters, Siegel makes the case for regarding critical thinking, or the cultivation of rationality, as a preeminent educational ideal, and the fostering of it as a fundamental educational aim. A wide range of alternative views are critically examined. Important related topics, including indoctrination, moral education, open-mindedness, testimony, epistemological diversity, and cultural difference are treated. The result is a systematic account and defense of critical thinking, an educational ideal widely proclaimed but seldom submitted to critical scrutiny itself.

SOME BASIC AND BEGINNING ISSUES FOR KHMER ETHNIC COMMUNITY, NOW

With the majority of the population working in agriculture, the economy of Khmer people is mainly agricultural. At present, the Khmer ethnic group has a workingstructure in the ideal age, but the number of young and healthy workers who have not been trained is still high and laborers lack knowledge and skills to do business. Labor productivity is still very low ... Problems in education quality, human resources; the transformation of traditional religion; effects of climate change; Cross-border relations of the people have always been and are of great interest and challenges to the development of the Khmer ethnic community. Identifying fundamental and urgent issues, forecasting the socio-economic trends in areas with large numbers of Khmer people living in the future will be the basis for the theory and practice for us to have. Solutions in the development and implementation of policies for Khmer compatriots suitable and effective.

EL PENSAMIENTO CRÍTICO EN LA EDUCACIÓN DE POSGRADO: PROPUESTA DE UN MODELO PARA SU INTEGRACIÓN AL PROCESO EDUCATIVO

La presente investigación, analiza los conceptos más importantes del pensamiento Crítico, así como su importancia y utilidad en los procesos de formación profesional a nivel de Posgrado. Se hace un análisis detallado de los conceptos más ampliamente aceptado y de los factores inmersos en el desarrollo y aplicación de este tipo de pensamiento. Finalmente se propone un modelo que engloba los conceptos y factores analizados y como se interrelacionan entre ellos; el objetivo final es brindar a los docentes y directivos de Instituciones de Educación Superior, una herramienta que posibilite la inclusión de este tipo de pensamiento en sus procesos enseñanza-aprendizaje con el fin último de mejorar la calidad de los procesos de formación. Palabras Clave: Pensamiento Crítico, Educación Superior, Educación ABSTRACT This research analyzes the most important concepts of critical thinking as well as their importance and usefulness for the educational processes at graduate level. A detailed analysis of the most widely accepted concepts and factors involved in the development and application of this kind of thinking has been made. Finally, a model that includes the concepts and analyzed factors and their interrelations is proposed; the ultimate goal is to provide teachers and directors of Institutions in Higher Education, a tool that enables the inclusion of this type of thinking in their teaching and learning processes with the ultimate intention of improving the quality of the training processes. Keywords: Critical thinking, Higher Education, Education Recibido: mayo de 2016Aprobado: septiembre de 2016

Modifikasi Model Pembelajaran Problem Based Learning (PBL) dengan Strategi Pembelajaran Tugas dan Paksa