What Is Creative Writing? (Ultimate Guide + 20 Examples)

Creative writing begins with a blank page and the courage to fill it with the stories only you can tell.

I face this intimidating blank page daily–and I have for the better part of 20+ years.

In this guide, you’ll learn all the ins and outs of creative writing with tons of examples.

What Is Creative Writing (Long Description)?

Creative Writing is the art of using words to express ideas and emotions in imaginative ways. It encompasses various forms including novels, poetry, and plays, focusing on narrative craft, character development, and the use of literary tropes.

Table of Contents

Let’s expand on that definition a bit.

Creative writing is an art form that transcends traditional literature boundaries.

It includes professional, journalistic, academic, and technical writing. This type of writing emphasizes narrative craft, character development, and literary tropes. It also explores poetry and poetics traditions.

In essence, creative writing lets you express ideas and emotions uniquely and imaginatively.

It’s about the freedom to invent worlds, characters, and stories. These creations evoke a spectrum of emotions in readers.

Creative writing covers fiction, poetry, and everything in between.

It allows writers to express inner thoughts and feelings. Often, it reflects human experiences through a fabricated lens.

Types of Creative Writing

There are many types of creative writing that we need to explain.

Some of the most common types:

- Short stories

- Screenplays

- Flash fiction

- Creative Nonfiction

Short Stories (The Brief Escape)

Short stories are like narrative treasures.

They are compact but impactful, telling a full story within a limited word count. These tales often focus on a single character or a crucial moment.

Short stories are known for their brevity.

They deliver emotion and insight in a concise yet powerful package. This format is ideal for exploring diverse genres, themes, and characters. It leaves a lasting impression on readers.

Example: Emma discovers an old photo of her smiling grandmother. It’s a rarity. Through flashbacks, Emma learns about her grandmother’s wartime love story. She comes to understand her grandmother’s resilience and the value of joy.

Novels (The Long Journey)

Novels are extensive explorations of character, plot, and setting.

They span thousands of words, giving writers the space to create entire worlds. Novels can weave complex stories across various themes and timelines.

The length of a novel allows for deep narrative and character development.

Readers get an immersive experience.

Example: Across the Divide tells of two siblings separated in childhood. They grow up in different cultures. Their reunion highlights the strength of family bonds, despite distance and differences.

Poetry (The Soul’s Language)

Poetry expresses ideas and emotions through rhythm, sound, and word beauty.

It distills emotions and thoughts into verses. Poetry often uses metaphors, similes, and figurative language to reach the reader’s heart and mind.

Poetry ranges from structured forms, like sonnets, to free verse.

The latter breaks away from traditional formats for more expressive thought.

Example: Whispers of Dawn is a poem collection capturing morning’s quiet moments. “First Light” personifies dawn as a painter. It brings colors of hope and renewal to the world.

Plays (The Dramatic Dialogue)

Plays are meant for performance. They bring characters and conflicts to life through dialogue and action.

This format uniquely explores human relationships and societal issues.

Playwrights face the challenge of conveying setting, emotion, and plot through dialogue and directions.

Example: Echoes of Tomorrow is set in a dystopian future. Memories can be bought and sold. It follows siblings on a quest to retrieve their stolen memories. They learn the cost of living in a world where the past has a price.

Screenplays (Cinema’s Blueprint)

Screenplays outline narratives for films and TV shows.

They require an understanding of visual storytelling, pacing, and dialogue. Screenplays must fit film production constraints.

Example: The Last Light is a screenplay for a sci-fi film. Humanity’s survivors on a dying Earth seek a new planet. The story focuses on spacecraft Argo’s crew as they face mission challenges and internal dynamics.

Memoirs (The Personal Journey)

Memoirs provide insight into an author’s life, focusing on personal experiences and emotional journeys.

They differ from autobiographies by concentrating on specific themes or events.

Memoirs invite readers into the author’s world.

They share lessons learned and hardships overcome.

Example: Under the Mango Tree is a memoir by Maria Gomez. It shares her childhood memories in rural Colombia. The mango tree in their yard symbolizes home, growth, and nostalgia. Maria reflects on her journey to a new life in America.

Flash Fiction (The Quick Twist)

Flash fiction tells stories in under 1,000 words.

It’s about crafting compelling narratives concisely. Each word in flash fiction must count, often leading to a twist.

This format captures life’s vivid moments, delivering quick, impactful insights.

Example: The Last Message features an astronaut’s final Earth message as her spacecraft drifts away. In 500 words, it explores isolation, hope, and the desire to connect against all odds.

Creative Nonfiction (The Factual Tale)

Creative nonfiction combines factual accuracy with creative storytelling.

This genre covers real events, people, and places with a twist. It uses descriptive language and narrative arcs to make true stories engaging.

Creative nonfiction includes biographies, essays, and travelogues.

Example: Echoes of Everest follows the author’s Mount Everest climb. It mixes factual details with personal reflections and the history of past climbers. The narrative captures the climb’s beauty and challenges, offering an immersive experience.

Fantasy (The World Beyond)

Fantasy transports readers to magical and mythical worlds.

It explores themes like good vs. evil and heroism in unreal settings. Fantasy requires careful world-building to create believable yet fantastic realms.

Example: The Crystal of Azmar tells of a young girl destined to save her world from darkness. She learns she’s the last sorceress in a forgotten lineage. Her journey involves mastering powers, forming alliances, and uncovering ancient kingdom myths.

Science Fiction (The Future Imagined)

Science fiction delves into futuristic and scientific themes.

It questions the impact of advancements on society and individuals.

Science fiction ranges from speculative to hard sci-fi, focusing on plausible futures.

Example: When the Stars Whisper is set in a future where humanity communicates with distant galaxies. It centers on a scientist who finds an alien message. This discovery prompts a deep look at humanity’s universe role and interstellar communication.

Watch this great video that explores the question, “What is creative writing?” and “How to get started?”:

What Are the 5 Cs of Creative Writing?

The 5 Cs of creative writing are fundamental pillars.

They guide writers to produce compelling and impactful work. These principles—Clarity, Coherence, Conciseness, Creativity, and Consistency—help craft stories that engage and entertain.

They also resonate deeply with readers. Let’s explore each of these critical components.

Clarity makes your writing understandable and accessible.

It involves choosing the right words and constructing clear sentences. Your narrative should be easy to follow.

In creative writing, clarity means conveying complex ideas in a digestible and enjoyable way.

Coherence ensures your writing flows logically.

It’s crucial for maintaining the reader’s interest. Characters should develop believably, and plots should progress logically. This makes the narrative feel cohesive.

Conciseness

Conciseness is about expressing ideas succinctly.

It’s being economical with words and avoiding redundancy. This principle helps maintain pace and tension, engaging readers throughout the story.

Creativity is the heart of creative writing.

It allows writers to invent new worlds and create memorable characters. Creativity involves originality and imagination. It’s seeing the world in unique ways and sharing that vision.

Consistency

Consistency maintains a uniform tone, style, and voice.

It means being faithful to the world you’ve created. Characters should act true to their development. This builds trust with readers, making your story immersive and believable.

Is Creative Writing Easy?

Creative writing is both rewarding and challenging.

Crafting stories from your imagination involves more than just words on a page. It requires discipline and a deep understanding of language and narrative structure.

Exploring complex characters and themes is also key.

Refining and revising your work is crucial for developing your voice.

The ease of creative writing varies. Some find the freedom of expression liberating.

Others struggle with writer’s block or plot development challenges. However, practice and feedback make creative writing more fulfilling.

What Does a Creative Writer Do?

A creative writer weaves narratives that entertain, enlighten, and inspire.

Writers explore both the world they create and the emotions they wish to evoke. Their tasks are diverse, involving more than just writing.

Creative writers develop ideas, research, and plan their stories.

They create characters and outline plots with attention to detail. Drafting and revising their work is a significant part of their process. They strive for the 5 Cs of compelling writing.

Writers engage with the literary community, seeking feedback and participating in workshops.

They may navigate the publishing world with agents and editors.

Creative writers are storytellers, craftsmen, and artists. They bring narratives to life, enriching our lives and expanding our imaginations.

How to Get Started With Creative Writing?

Embarking on a creative writing journey can feel like standing at the edge of a vast and mysterious forest.

The path is not always clear, but the adventure is calling.

Here’s how to take your first steps into the world of creative writing:

- Find a time of day when your mind is most alert and creative.

- Create a comfortable writing space free from distractions.

- Use prompts to spark your imagination. They can be as simple as a word, a phrase, or an image.

- Try writing for 15-20 minutes on a prompt without editing yourself. Let the ideas flow freely.

- Reading is fuel for your writing. Explore various genres and styles.

- Pay attention to how your favorite authors construct their sentences, develop characters, and build their worlds.

- Don’t pressure yourself to write a novel right away. Begin with short stories or poems.

- Small projects can help you hone your skills and boost your confidence.

- Look for writing groups in your area or online. These communities offer support, feedback, and motivation.

- Participating in workshops or classes can also provide valuable insights into your writing.

- Understand that your first draft is just the beginning. Revising your work is where the real magic happens.

- Be open to feedback and willing to rework your pieces.

- Carry a notebook or digital recorder to jot down ideas, observations, and snippets of conversations.

- These notes can be gold mines for future writing projects.

Final Thoughts: What Is Creative Writing?

Creative writing is an invitation to explore the unknown, to give voice to the silenced, and to celebrate the human spirit in all its forms.

Check out these creative writing tools (that I highly recommend):

Read This Next:

- What Is a Prompt in Writing? (Ultimate Guide + 200 Examples)

- What Is A Personal Account In Writing? (47 Examples)

- How To Write A Fantasy Short Story (Ultimate Guide + Examples)

- How To Write A Fantasy Romance Novel [21 Tips + Examples)

Understanding Reading and Writing Differences Across Disciplines

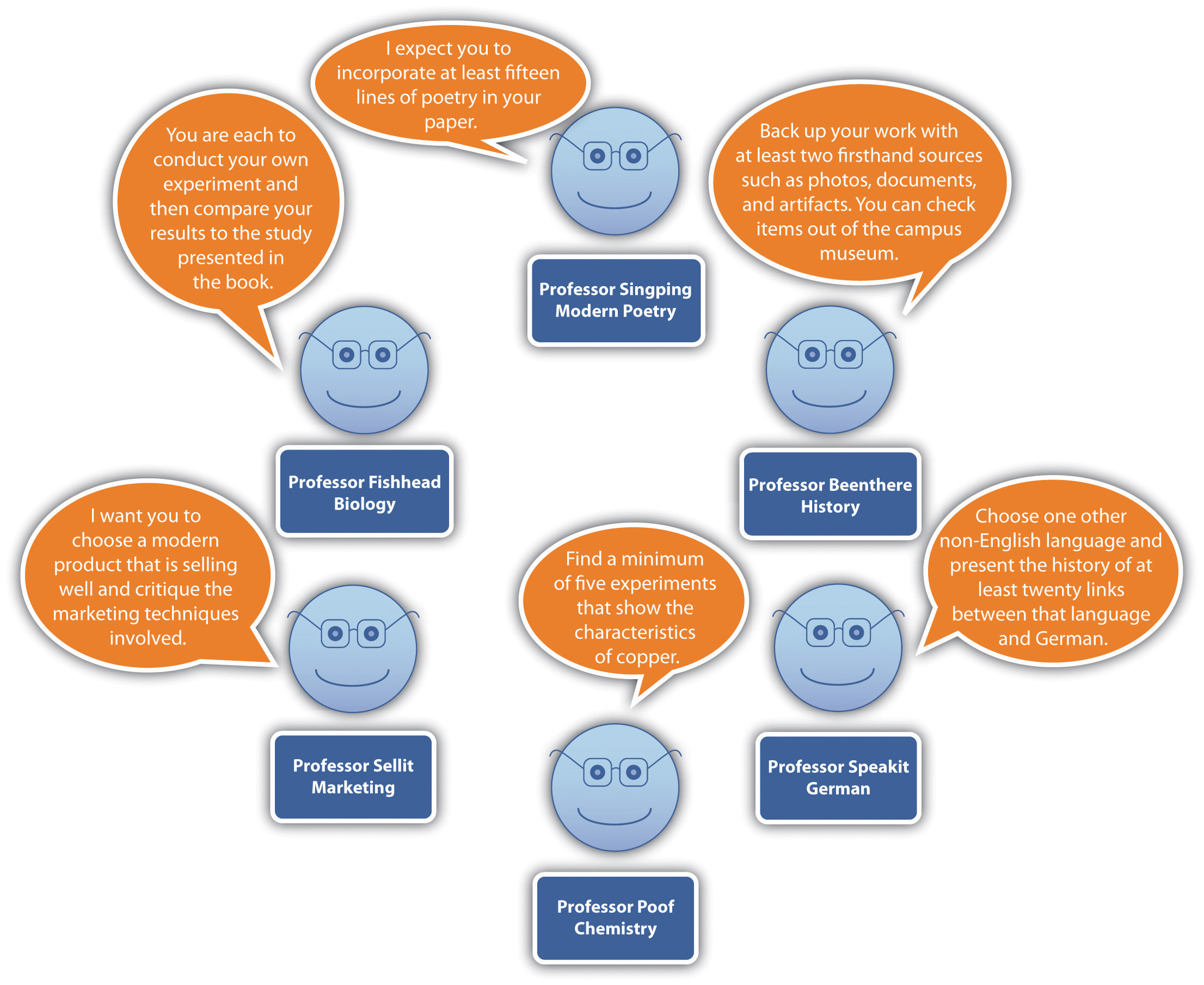

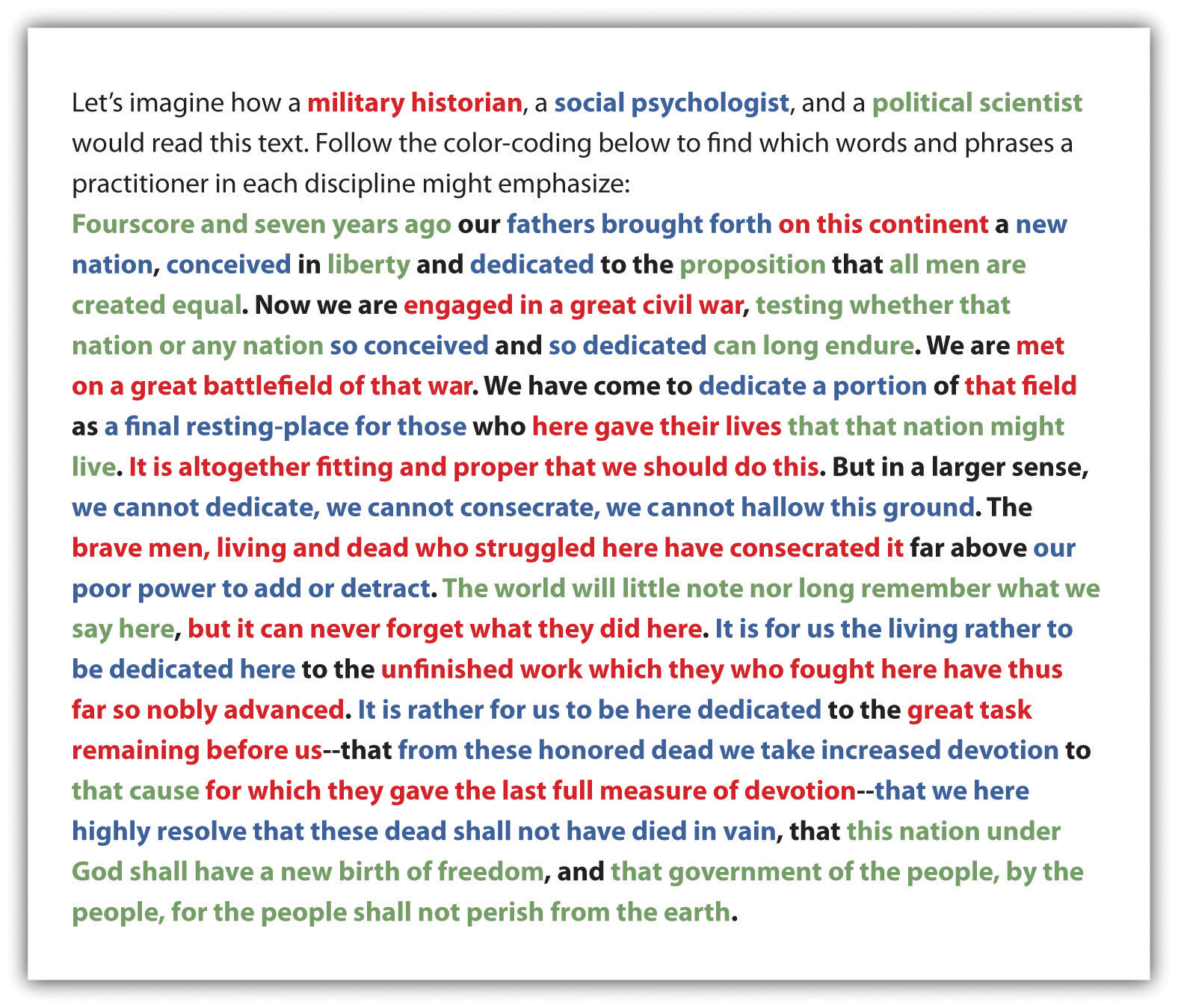

LESSON Critical reading A thorough examination of a text to understand and evaluate not just what it says but also its purpose, meaning, and effectiveness. In this context, critical means careful and thoughtful, not negative. requires more than understanding new vocabulary words and identifying the main idea The most important or central thought of a reading selection. It also includes what the author wants the reader to understand about the topic he or she has chosen to write about. and supporting details Statements within a reading that tie directly to major details that support the main idea. These can be provided in examples, statistics, anecdotes, definitions, descriptions, or comparisons within the work. . Effective readers know that they must use different strategies when they approach different types of writing. Depending upon which academic field you find yourself in, you will find that each discipline An area of study, like history, science, or psychology. has its own way of communicating. Even when writing on the same topic The subject of a reading. , historians, scientists, artists, and psychologists will tackle the topic differently. In this lesson, you will learn how to approach three particular disciplines—science, history, and pop culture.

Whenever you approach a piece of writing in a particular discipline, consider these six aspects:

- Writer's purpose

- Writing tone and style

- Reader's goal

- Specific language

- Organization

- Discipline-specific features

The writer's purpose for writing. Writers change their purpose The reason the writer is writing about a topic. It is what the writer wants the reader to know, feel, or do after reading the work. for writing depending on the discipline they are writing for, the topic they will cover, and the goals of that particular writing task.

The writing tone and style . When you speak with someone, you listen for what is said, but you also listen for how it is said. People's tones The feeling or attitude that a writer expresses toward a topic. The words the writer chooses express this tone. Examples of tones can include: objective, biased, humorous, optimistic, and cynical, among many others. often reveal more than their words, and the same holds true in writing. Different disciplines will have different tones depending on the material they need to present and their audience. For example, when a writer creates an article A non-fiction, often informative writing that forms a part of a publication, such as a magazine or newspaper. for a science journal that updates a new finding, the tone will reflect the information or educational goal by presenting the information in a straightforward, possibly formal manner. This would differ from a writer who wants to create enthusiasm for a topic or persuade To convince someone of a claim or idea. the reader to take an action. The same is true for style. An article in a science journal would be written in a formal academic style with distinct sections including an abstract A summary of an article often written by the author and reviewed by the editor of the article. The abstract provides an overview of the contents of the reading, including its main arguments, results, and evidence, allowing you to compare it to other sources without requiring an in-depth review. , research and methods, findings, and conclusions. An article in a popular magazine or website, on the other hand, would follow a more entertaining and approachable style.

The reader's goal for reading the text. Your goal as a reader will change depending upon what you are reading. When you understand your goal in picking up a biology text or historical journal, you will save time because you can more quickly find what you should be looking for.

The specific language that the writer uses . Just as Italian is spoken in Italy and Spanish in Spain, all academic disciplines have their own jargon Technical language pertaining to a specific activity and used by a particular group of people. and language particulars. When you understand these specifics, you will be one step closer to understanding the text.

The organization of the reading A piece of writing to be read. A reading can either be a full work (i.e., a book) or partial (i.e., a passage). . Just as poetry and short stories are structured differently, readings across all disciplines are also organized and structured in specific ways. Becoming familiar with these differences will help you find the essential information while using pre-reading strategies as well during active reading.

The discipline-specific features of the text. Lastly, each discipline has traits The specific parts of a person, place, or thing that distinguish it from another. that are specific to that particular field. For example, scientific writing often includes charts and figures that you will not see in a pop culture piece.

Giving the "ok" symbol (formed by creating a circle with your thumb and index finger) is a very positive sign in the United States. It lets others know that you and/or they are doing well. However, if you make that same exact sign in Brazil, you will not make friends because Brazilians understand that sign in the same way Americans would if someone raised a middle finger at them! Reading discipline-specific texts can be equally confusing if you don’t understand how to read them. You risk spending time and effort focusing on the wrong details. As a result, you will not understand the author's purpose or main ideas.

In your career, you may have to read different sources A person, book, article, or other thing that supplies information. to gather information for projects or plans. It is important to recognize what type of discipline you are reading for your research. For example, reading a pop culture magazine article on the economy when compiling a report on the financial outlook of your company is probably not the right choice. Instead, you should look for information in peer-reviewed Writings that have been evaluated by experts in a subject before they are published. economic journals or other more fact-based sources.

Below are two introductory paragraphs to two readings that both approach the same topic with two different discipline-specific tactics. Read each passage A short portion of a writing taken from a larger source, such as a book, article, speech, or poem. , and consider the following questions about the intended audience, purpose, and differences in the readings.

A. In the early days of World War I, German submarines devastated the British and American fleets. Submariners would sneak up on a moving ship, watch it just long enough to figure out its speed and direction, and then fire torpedoes into the ship's path. There was little that surface boats could do to hide from submarines. Although the military was very good at camouflaging troops and tanks on land, ships couldn't be painted to blend into the background because the colors of the sea and the sky are always changing. But then the British had a startling idea—if they can’t hide them, why not make the ships stand out instead? They decided to paint them in contrasting colors and random patterns, like zebras and giraffes, animals that are easy to spot but hard to track because the patterns they wear break up their outline. The Navy called this disruptive camouflage razzle dazzle : odd, irregular patterns and colors that would confuse enemy gunners and throw off their aim by disguising the shape and motion of their ships.

B. Looking for a red carpet transformation? It's tempting to reach for the go-to tools. After all, a dangerously high heel can make a short frame statuesque, and industrial shapewear can turn a pear into an hourglass. But combine stilettos with a cincher and a swanky affair could end in a visit to the emergency room. Thankfully, this season's hot trend offers an alternative for literal fashion victims in the form of high-contrast stripes and strategic color-blocking all perfectly placed to minimize, enhance, elongate, and taper.

- Who is the intended audience for passage A and B?

Passage A is beneficial for the reader who has a basic understanding of WW I. It introduces an idea that may have given the British an advantage in the war.

Passage B is written for the reader who is concerned with looking good, especially in regards to her figure. With its discussion of stilettos, it seems to be intended more for women.

- What is the intended purpose of passage A and B?

Passage A provides needed context to introduce the idea of razzle dazzle .

Passage B uses a question to draw the reader in to the article. It is also trying to convince the reader to abandon high heels and corsets in favor of outfits with stripes and color-blocking.

- What are the major differences in passage A and B?

Passage A tells a story. While overall, much of the language is objective, the author also inserts subjective language, such as startling and devastated .

Passage B uses more informal and friendly writing. Overall, its language is heavily subjective.

Below are two body paragraphs The part of an essay that comes after the introduction and before the conclusion. Body paragraphs lay out the main ideas of an argument and provide the support for the thesis. All body paragraphs should include these elements: a topic sentence, major and minor details, and a concluding statement. Each body paragraph should stand on its own but also fit into the context of the entire essay, as well as support the thesis and work with the other supporting paragraphs. to two readings that both approach the same topic with two different discipline-specific tactics. Read each passage, and answer the following questions about the intended audience, purpose, and differences in the readings.

A. There are many different methods of camouflage. Octopi and lizards match the color and texture of their skins with nearby rocks and vegetation to blend into the background, and manmade hunting gear is painted or woven to do the same thing. Zebras have wild stripes that disrupt their outlines, especially when they move in groups, and so did dazzle-painted warships in World War I. Moths and caterpillars are shaped like leaves and twigs to fool predators, while cell phone towers are built like trees to hide their industrial clutter from neighbors. Gazelles and whales have counter-shaded sides that flatten and minimize rounded shapes, as do color-blocked dresses.

B. Applying the razzle dazzle idea took a lot more than handing sailors buckets of paint and letting them have it. First, a wooden model of each ship was built to scale and then handed off to artists who designed and painted individualized patterns. Next, the dazzled model was placed next to a matching one painted plain gray and then the two were placed in front of various simulated backgrounds of water and sky. Designers studied the pair through periscopes to judge how well the camouflage worked and made adjustments as needed. After the pattern was approved, precise plans of the color scheme were drafted and sent to where the actual ship was docked.

Sample Answer

Passage A is meant for the reader who wants to understand the full scope of camouflage in nature.

Passage B is intended for the reader who wants to know about the process of razzle dazzle from conception to execution.

The purpose of passage A is to explain the different ways that camouflage is used in the natural world.

The purpose of passage B is to inform the reader about the process the Navy used to design and paint razzle dazzle ships.

Passage A uses classification to organize its ideas. The entire paragraph breaks camouflage into a number of different categories, including that of octopi and lizards; zebras; moths and caterpillars; and gazelles and whales.

Passage B, on the other hand, is organized according to time order. It outlines the process of painting the ships. It also uses a number of signal words to identify when the supporting details happened i.e. first , next, and after .

Since psychology is a type of science, I will rely on Greek and Latin roots to help me understand unfamiliar vocabulary. I will also look for charts and figures that may summarize the results. To judge its validity, I will pay close attention to the methodology used to come to particular conclusions.

Reading literature is not like most of my other academic reading. In order to get the big picture, it is necessary to read an entire book from front to back. It is not possible to skip from one chapter to the next. To understand an author or idea, it may be necessary to read more than one text by the same author or along the same theme.

Copyright ©2022 The NROC Project

8.8 Spotlight on … Discipline-Specific and Technical Language

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the role of discipline-specific and technical language in various situations and contexts.

- Implement purposeful shifts in voice, tone, level of formality, and word choice.

- Pursue options for publishing your report.

Proficient report writers in all academic disciplines and professions use language that is clear, direct, economical, and conventional. Moreover, they often use a specialized vocabulary to convey information to others in their field. These technical words allow specialists to communicate precisely and efficiently with other experts, but such terms can be confusing to nonspecialists. The following guidelines can help you shape the language of a report in a social science, natural science, or technical field:

student sample text Computer storage space is measured in units called kilobytes (KB). Each KB equals 1,024 “bytes,” or approximately 1000 single typewriter characters. Therefore, one KB equals about 180 English words, or a little less than half of a single-spaced typed page, or maybe three minutes of fast typing. One terabyte (TB) is 1024 gigabytes (GB), one GB is 1024 megabytes (MB), and one MB is 1024 KB. end student sample text

student sample text After the first U.S. coronavirus case was confirmed in 2020, the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) was named to lead a task force on a response, but after several months he was replaced when then vice president Mike Pence was officially charged with leading the White House Coronavirus Task Force (Ballhaus & Armour, 2020). end student sample text

student sample text The causes of obesity are complex and involve multiple factors, including genetics, underlying health conditions, cultural attitudes toward food and exercise, access to healthy food and health care, safe outdoor spaces, income, and leisure time. end student sample text student sample text The survey respondents self-identified as cisgender female (153), cisgender male (131), gender nonbinary (12), and transgender (4). end student sample text

- Consider occasional use of the passive voice. Traditionally, writers in the sciences and technical fields have used the passive voice for objectivity and neutrality. In the passive voice , the subject of the sentence is acted upon; in the active voice , the subject acts. Increasingly, scientific and technical writers use the active voice in the introduction and conclusion sections of reports, which are more interpretative. They use the passive voice in the method and results sections, which are more straight-up reporting.

Notice that by using the passive voice, the writer is able to avoid naming the person or group who conducted the survey. The passive voice is a technique that writers often use when they don’t want to make the name of an individual or group public. See Clear and Effective Sentences for more on passive and active voice.

Passive voice: A survey of 300 students underline was conducted end underline at a large state university in the southern United States. Active voice: underline We conducted end underline a survey of 300 students at a large state university in the southern United States.

- Pay attention to the details of meaning, grammar, punctuation, and mechanics. Each discipline values precision and correctness, and each has its own specialized vocabulary for talking about knowledge. Writers are expected to use terms precisely and to spell them correctly. Your writing will gain greater respect when it reflects standard grammar, punctuation, and mechanics.

Publish Your Report

Now that you have completed all stages of your report, you may want to think about sharing it with students at your school or other colleges. Your college may have a journal that publishes undergraduate research work. If so, find out about submitting your work. Also, listed here are some of the many publications that feature undergraduate student research. Check them out.

- Papers & Publications: Interdisciplinary Journal of Undergraduate Research (accepts work from students in the southeastern United States)

- Journal of Undergraduate Research (peer-reviewed undergraduate journal; accepts research work in all subjects)

- Journal of Student Research (accepts student work from high school through graduate school)

- Crossing Borders: A Multidisciplinary Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship (published at Kansas State University; accepts student research in all disciplines from undergraduates throughout the country)

- 1890: A Journal of Undergraduate Research (accepts undergraduate works of research, creative writing, poetry, reviews, and art)

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/8-8-spotlight-on-discipline-specific-and-technical-language

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Nov 12, 2021

- 10 min read

Creative Writing 101: Theorizing Creative Writing as a Discipline

Vanderbilt University. (2012, September 11). [Kate Daniels (center, near window) addresses students in a creative writing master’s class. (Vanderbilt University)]. Vanderbilt.Edu. https://news.vanderbilt.edu/2012/09/11/creative-writing-top-10/

Creative Writing 101 articles serve as one of the academic courses in the field of Literary Theory and Literature. The course, which is a fundamental guide within the scope of general knowledge compared to the technical knowledge of Literary Theory and Literature, also addresses students and the general readership alike. With this goal in mind, the author has opted to write the article in very plain and basic English to convey just the necessary understanding of Creative Writing by making the article merely an introduction.

Creative Writing 101 is mainly divided into five chapters including:

- Creative Writing 101: Into the Writer’s Creative Mind: Overview & Dynamics

- Creative Writing 101: Theorizing Creative Writing as a Discipline

- Creative Writing 101: Insights on Writing Poetry

- Creative Writing 101: Insights on Writing Short Stories

- Creative Writing 101: Insights on Writing Novels

In the previous article of Creative Writing 101 series entitled “Into the Writer’s Creative Mind: Overview & Dynamics”, the focus was on the dynamics of the author’s creative mind along with an overview of the core of creative writing, exemplified in Tolkien’s short story Leaf by Niggle and Aristotle’s Poetics. In the second article of Creative Writing 101, the historical background of the subject will be further discussed and elaborated, paving the way to question and comprehend the means by which scholars, professors, and teacher-writers, for example, succeeded in structuring and framing Creative Writing in a discipline taught at American and English universities.

Dianne J. Donnelly (2009) explains that “Creative Writing and Creative Writing studies are two distinct enterprises” (p.2), for the success of teaching the subject was initially included in workshops, before being set in an undergraduate curriculum program and taught by many specialized instructors in the U.K, the U.S.A and other countries around the world. The institutionalization of Creative Writing has become popular in many universities worldwide, training international writers to enhance their creative writing skills in order to become better writers, whose writing potential can be much more appealing for future employers, editors, and publishing houses. To better understand the establishment of Creative Writing as a discipline, if ever applicable to be called so or agreed to be fully institutionalized as such, there has to be a mapping of the prominent historical events that led to its emergence in institutions.

Towards a Historical Background

The traces of teaching Creative Writing at universities were claimed to have appeared in the 1880s in the U.S.A at Harvard College, initiated by the Professor of English Barrett Wendell (1855-1921) as the writer and Professor of Literature, Lauri Ramey (2007) asserts. Wendell’s teaching of “English composition and literature from 1880 until his retirement in 1917” ( newnetherlandinstitute ) was a method of composing literary narratives like poetry. Correspondingly, Lauri Ramey (2007) further explains that “the class stressed ‘practice, aesthetics, personal observation, and creativity’ as opposed to the ‘theory, history, tradition and literary conservation’ taken as the concerns of newly developing departments of English” (pp.43). In other words, the appearance of Creative Writing has emerged initially in American universities.

Harvard Faculty of Arts and Science. (2021). [1915 portrait of Barrett Wendell is part of the Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers at Biblioteca Berenson at Villa I Tatti, The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.]. Harvard.Edu.

https://histlit.fas.harvard.edu/since-1906

During the 1920s, the University of Iowa included a newly subject, described as “imaginative writing” (Swander et al., 2007, p.12) to its artistic list of disciplines already part of the university program, such as Painting, Sculpture, Theatre, and Dance. In 1931, “Paisley Shawl”, a collection of poetry written by Mary Hoover Roberts was the first master thesis to have been accepted by the University of Iowa, before other theses, written by former students Wallace Stegner and Paul Engle, were submitted and approved by the university. The instance of “Worn Earth” written by Paul Engle was “the 1932 winner of the Yale Younger Poets Award,” and also, “became the first poetry thesis at the University of Iowa to be published.” (Swander et al., 2007, p.12).

Years before Paul Engle (1908-1991) became a prominent literary figure, fostering other students to enhance their writing skills through workshops, Norman Foerster, the former director of the school of Letters, explains Swander et al. (2007), engaged further much with the writing program at university during the 1930s. Once Paul Engle became a member of the University of Iowa in 1937, he organized the Iowa Writers Workshop and in 1943, he became its director as he is “ best remembered as the long-time director of the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop and founder of the UI’s International Writing Program ”, aside from the fact that he “also was a well-regarded poet, playwright, essayist, editor and critic. ” (iowacityofliterature.org, 2020) .

Poetry Foundation. (2021). [A Photograph of Paul Engle (1908–1991)]. Poetryfoundation.Org. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/paul-engle

Engle, a hard-driving, egocentric genius, possessed the early vision of both the Writers Workshop and the International Writing Program. He foresaw first-rate programmes where young writers could come to receive criticism of their work. A native Iowan who had studied in England on a Rhodes Scholarship and travelled widely throughout Europe, Engle was dissatisfied with merely a regional approach. He defined his ambition in a 1963 letter to his university president as a desire ‘to run the future of American literature, and a great deal of European and Asian, through Iowa City’ (Wilbers 1980: 85–6).

As a matter of fact, Engel’s academic contribution in institutionalizing Creative Writing within workshops and programs by training American and international writers, giving them constructive criticism on their elaborated literary works to enhance their writing skills and help them succeed in their endeavors and literary achievements, and also frame more adequate and effective creative writing programs in the American institutions. For instance, Engel divided and categorized creative writing workshops into various genres as Poetry and Fiction to be fully devoted and in charge of the training of the writers. Connoisseurs of Literature such as Robert Frost, Dylan Thomas, and W.H Auden were invited to attend and run workshops organized by Engel on campus to contribute to the betterment of future writers’ creative writing skills.

[Robert Frost (left) and Paul Engle (right) addressing Workshop students in 1959]. (n.d.). https://Writersworkshop.Uiowa.Edu/about/about-Workshop/history.

Frederick W. Kent Collection of Photographs. [Paul Engle with Iowa Writers’ Workshop students, ca. 1960]. The University of Iowa Libraries. https://www.lib.uiowa.edu/sc/archives/faq/faqphotocollections/

In the 1940s, the discipline of Creative Writing became more established through postgraduate degrees delivered by American universities like Johns Hopkins University, University of Denver, University of Iowa, and Stanford University explains Lauri Ramey (2007). The debate over framing Creative Writing in a discipline that could be taught at American universities was controversial to some extent until approved by scholars and members of the academia to design Creative Writing programs for students that are willing to major in such discipline. Presumably, the period between the late 1960s and early 1970s witnessed more attendance of many American students, willing to graduate in Creative Writing, in American universities.

Jeffcutt, P. (2013, September 7). [A group of writers attending a Writing Workshop organized by the poet Philip Hobsbaum in 1962. Belfast, Northern Ireland.]. Writing2survive.Blogspot. http://writing2survive.blogspot.com/2013/09/the-writers-group-and-seamus-heaney.html

In parallel, the discipline of Creative Writing, originally called as Imaginative Writing, was introduced in the U.K starting from the 1950s and 1960s through several initiatives made by academics like the British writer Angus Wilson through organizing workshops for the Undergraduates at the University of East Anglia (UEA) and also thanks to the poet Philip Hobsbaum’s writing group events organized in 1952 at Cambridge, London, Belfast and Glasgow, explains Andrew Cowan (2016), Professor of Creative Writing at the UEA. Moreover, the discipline of Creative Writing was institutionalized in the U.K in 1969 when the University of Lancaster offered a Master of Arts in Creative Writing, assert Swander et al. (2007), followed by the UEA a year later as it launched its own MA in Creative Writing states Andrew Cowan (2016). Writers-teachers such Angus Wilson and Malcolm Bradbury, who had similar university teaching experiences in American universities, were invited to teach Literature at UEA, by adopting the American method.

Shutterstock. (2000, December 1). [Sir Malcolm Bradbury Writer, with Angus Wilson at University of East Anglia in the Eighties]. Shutterstock.

https://www.shutterstock.com/editorial/image-editorial/sir-malcolm-bradbury-writer-at-uea-in-the-eighties-329502i

The Observer. [Malcolm Bradbury with students on the University of East Anglia’s creative writing course, 1983]. Theguardian.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/jan/22/body-of-work-review-foden

The Imaginative Writing classes in high education, before it turned to be known as Creative Writing, started to soar from “ 2,745 in 2003 to 6,945 in 2012” ( Andrew Cowan, 2016). The learning of the new discipline was much appreciated by undergraduate students in the U.K that it was combined with other art classes such as Film, Literature, and Language studies to engage a larger number of students in the specialty. Andrew Cowan (2016) claims that Higher Education Institutions “ offering BA courses (in a variety of combinations) rose from 24 to 83, while the number of MA courses rose from 21 to 200, and the number of PhD programs from 19 to more than 50.”

MA in Creative Writing in the U.K

Jenny Newman (2007) explains that MA in Creative Writing in the U.K can be studied for over a year in case it is a full-time study program or done over two consecutive years as in a part-time study program. The students are given the possibility to choose one course out of three: Poetry, fiction or screenwriting. When it comes to the method of assessment, the numerous tasks elaborated by the student are done through, for example, an analytical essay, an oral presentation, the creation of a website of his or her own, workshops to attend, an exercise of editing and proofreading, and an analytical essay of another student’s work. Still, a divergence of opinions on the curriculum to teach Creative Writing studies is palpable as it is similar yet slightly distinct from Literary studies.

“With certain exceptions, and many variations, the “typical” MA course continues to emphasise the acquisition of technical skills and the completion of a publishable manuscript over the concerns of critical scholarship. And while Creative Writing and Literary Studies frequently reside in a relationship of departmental proximity, they continue to take divergent approaches to the conception and study of literature.” ( Andrew Cowan, 2016)

Creative Writing Master of Fine Arts (MFA) in the U.S.A

The MFA is the American version of the English MA in Creative Writing, which was initiated at the University of Iowa in the 1930s . It is longer than the MA, for it is characterized by “expanded credit hour requirements, such as a thesis, or substantial body of creative work and special coursework.” (Vanderslice, 2007, p.37). Conceived differently from the English version of the Master's degree, it is the combination of the studio arts tradition and the English literature tradition at American high institutions.

“Some programs include traditional literature courses in the degree, taught by literature faculty and assessed by traditional means – analytical papers, essay exams and so forth (also read by one reader – the professor – unlike in the UK).” (Vanderslice, 2007, p.39).

PhD in Creative Writing

Paul Dawson (2007) states that for any person willing to teach at American universities, there has to be an additional doctoral degree to the MFA. Taking into account the importance of the PhD, some researchers in the field, such as Kelly Ritter advocates the idea that the MFA is considered insufficient for teaching Creative Writing at universities and that a PhD along with the publication of several books are required for such vocation; also, Patrick Bizarro and Kelly Ritter, both think that a PhD in Creative Writing should be framed otherwise. In other words, the MFA and PhD programs are two distinct areas of studies that have to be reshaped for a better acquisition of the teaching skills of the discipline, as further explains Paul Dawson (2007).

“The debates over the PhD in Australia and the UK have differed from those in America because the degree structure itself is different. Whereas in America doctoral students must complete substantial coursework and language requirements as well as sitting for comprehensive examinations before submitting their dissertation, in these countries there is no formal coursework and the degree is assessable by thesis only. The thesis consists of a creative dissertation and a substantial critical essay, often referred to as the ‘exegesis’, of up to 50 per cent of the word limit.” (Paul Dawson, 2007, pp.88).

All things considered, in spite of the controversies over the establishment of Creative Writing as an institutionalized discipline in high education as in the instance of the American and the Anglophone academy, the specialty was officially approved by scholars and academics, for it has been revised and reconfigured over the years for better acquisition of the mechanisms of creative writing in various genres like poetry, fiction, and scriptwriting. The discipline has been expanded and taught by other foreign academic institutions worldwide, in parallel leading to an increase of “the membership listings on the website of the Asia-Pacific Writers & Translators Association (APWT 2018) or by the growth in membership of the European Association of Creative Writing Programmes (EACWP).” ( Andrew Cowan, 2016).

Image Sources

Harvard Faculty of Arts and Science. (2021). [1915 portrait of Barrett Wendell is part of the Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers at Biblioteca Berenson at Villa I Tatti, The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.]. Harvard.Edu. https://histlit.fas.harvard.edu/since-1906

[Robert Frost (left) and Paul Engle (right) addressing Workshop students in 1959]. (n.d.). Https://Writersworkshop.Uiowa.Edu/about/about-Workshop/History.

Shutterstock. (2000, December 1). [Sir Malcolm Bradbury Writer, with Angus Wilson at University of East Anglia in the Eighties]. Shutterstock. https://www.shutterstock.com/editorial/image-editorial/sir-malcolm-bradbury-writer-at-uea-in-the-eighties-329502i

The Observer. [Malcolm Bradbury with students on the University of East Anglia’s creative writing course, 1983]. Theguardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/jan/22/body-of-work-review-foden

Barrett Wendell [1855-1921] . (n.d.). Newnetherlandinstitute.Org. Retrieved November 9, 2021,

From https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.org/history-and-heritage/dutch_americans/barrett-wendell/

City of Literature Paul Engle Prize . (2020). Iowacityofliterature.Org. Retrieved November 8, 2021,

from https://www.iowacityofliterature.org/paul-engle-prize/

Cowan, A. (2016). The Rise of Creative Writing. Writing in Education , 4 (Previous Issues). https://www.nawe.co.uk/DB/wip-editions/articles/the-rise-of-creative-writing.html

Creative Writing Studies as an Academic Discipline (No. 3809). Scholar Commons. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5005&context=etd

Dawson, P. (2007). The Future of Creative Writing. In S. Earnshaw (Ed.), The Handbook of Creative Writing (pp. 78–90). Edinburgh University Press.

Donnelly, D. J. & University of South Florida. (2009, July). Establishing Creative Writing Studies as an Academic Discipline (No. 3809). Scholar Commons.https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5005&context=etd

Newman, J. (2007). The Evaluation of Creative Writing at MA Level (UK). In S. Earnshaw (Ed.), The Handbook of Creative Writing (pp. 24–36). Edinburgh University Press.

Ramey, L. (2007). Creative Writing and Critical Theory. In S. Earnshaw (Ed.), The Handbook of Creative Writing (pp. 42–53). Edinburgh University Press.

Swander, M., Leahy, A., & Cantrell, M. (2007). Theories of Creativity and Creative Writing Pedagogy. In S. Earnshaw (Ed.), The Handbook of Creative Writing (pp. 11–23). Edinburgh University Press.

Vanderslice, S. (2007). The Creative Writing MFA. In S. Earnshaw (Ed.), The Handbook of Creative Writing (pp. 37–41). Edinburgh University Press.

Wilbers, Stephen (1980), The Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press.

Arcadia, has many categories starting from Literature to Science. If you liked this article and would like to read more, you can subscribe from below or click the bar and discover unique more experiences in our articles in many categories

Let the posts come to you.

Thanks for submitting!

- Departments

- For Students

- For Faculty

- Writing Center

For Instructors

- Teaching Writing in the Age of ChatGPT

- FYW Teaching Resources

- Proposing and Renewing JYW Courses

- Assignment Design

- Peer Review

- Teacher Feedback and Paperloads

- Further Reading About Teaching Writing

- Professional Development

- Teaching Associate Employment

- Additional Opportunities

Useful Links

- English Department

- College of Humanities & Fine Arts

- HFA Advising & Career Center

- HFA Careers & Internships

Designing Discipline-Specific Writing Assignments

Learn to write (ltw) activities.

Writing can help students learn and think critically about course content. When students are asked to write discipline-specific genres, they learn to think and write like professionals in those disciplines. Two approaches to integrating writing in courses include write to learn (WTL) and learn to write (LTW) activities; for more about WTL activities, see our Principles page . LTW activities are high-stakes writing in which students learn to think like and communicate as professionals in discipline-specific genres.

Objectives for Learn to Write Activities

- Learn course content

- Practice disciplinary ways of thinking

- Learn about discipline-specific genres

- Practice writing discipline-specific genres

- Adapt one’s writing to a variety of audiences

Which Genres Matter Most in Your Discipline?

Genres often vary by discipline and reflect what, how, and to whom the discipline communicates. Here are just some of the genres that we’ve seen in JYW courses at UMass: personal narratives about students’ disciplinary interests; critical responses to scholarship; analyses of images, texts, or other cultural artifacts; literature reviews; research proposals; research articles; lab reports; op-eds; oral presentations; informational videos on YouTube or other media; blog posts for public audiences; and more.

When thinking about the select disciplinary genres that you assign, consider the form, habits of mind, or audiences that professionals in your discipline recognize. By form, how is this particular genre often structured? When considering the habits of mind, ask what ways of thinking, kind of evidence and logic, and skills students might need to write successfully in disciplinary genres. Lastly, you’ll want to consider the intended audiences for the genre and assignment.

It’s worth noting that some assignments may require similar content skills, but in terms of writing, they require different audiences and habits of mind. A lab notebook might be more about the detail and process, including some personal observations of the process, for an audience of the writer and perhaps few others. On the other hand, a lab report is more contained, focused on the findings, and the audience might be just the professor or possibly a lab group. Lastly, an article is a polished, finalized product of this research. The emphasis is on persuasive and strong evidence, with a much far-reaching audience.

Sequence the Assignments

It’s important to consider in what order students should work through assignments. How can you require multiple occasions for writing? What might students need to practice in order to be successful on future writing assignments? For example, the curriculum may sequence assignments along one or more of the following tracks:

- first, specialists; then, non-specialist scientists (e.g.: NSF); last, popular audience

- literature review, methodology, analysis of teacher-provided or new data; conclusions; new research proposal based on findings

- literature review; lab report with teacher-provided methodology and data; research proposal to specialist audience; research proposal to funding agency

Designing Effective Assignments

- Identify and communicate 3-4 learning goals for the assignment.

- Make the prompt meaningful by helping students identify their purpose and intended readers.

- Create scaffolded activities to help students meet those learning goals.

- Set a plan with clear expectations and deadlines.

- Be sure to include multiple opportunities for drafting, feedback (both peer and instructor ), and revision throughout.

Questions to Ask Yourself when Designing Assignments

- What are the main units (and associated assignments) in your course?

- What are the main learning objectives for each unit?

- What are the chief concepts or principles you want students to learn?

- What thinking skills or habits of mind are you trying to develop in your students?

- How should you write the assignment to convey the learning goals to students?

- Does the assignment clearly articulate the desired learning outcomes?

Further Reading

- Bean, John C. “Designing and Sequencing Assignments to Teach Undergraduate Research.” Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom , 2nd Edition , Jossey-Bass, 2011, pp. 224-63.

- –. “Part Two: Designing Problem-Based Assignments.” Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom , 2nd Edition , Jossey-Bass, 2011, pp. 89-145.

- Glenn, Cheryl and Melissa A. Goldthwaite. “Successful Writing Assignments.” The St. Martin’s Guide to Teaching Writing , 7th Edition , Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2014, pp. 95-124.

- UMass Amherst University Writing Program. “ Sourcebook for Junior Year Writing Courses .” 2007-2008.

Writing & Stylistics Guides

- General Writing & Stylistics Guides

Writing in the Disciplines

- Arts & Humanities

- Creative Writing & Journalism

- Social Sciences

- Computer Science, Data Science, Engineering

- Writing in Business

- Literature Reviews & Writing Your Thesis

- Publishing Books & Articles

- MLA Stylistics

- Chicago Stylistics

- APA Stylistics

- Harvard Stylistics

Need Help? Ask a Librarian!

You can always e-mail your librarian for help with your questions, book an online consultation with a research specialist, or chat with us in real-time!

Once you've gotten comfortable with the basic elements of style and conventions of writing, you'll find that the craft of writing is not a one-size-fits-all pursuit: different disciplines employ different conventions and styles, which you'll need to be familiar with. Learn more about the discipline-specific styles for Creative Writing (including journalism, writing fiction, and creative non-fiction), writing in the Social Sciences (including psychology, gender & sexuality studies, sociology, social work, international relations, and politics), and crafting your essay in the Arts and Humanities (including history, literature, music, and the fine arts).

- << Previous: General Writing & Stylistics Guides

- Next: Arts & Humanities >>

- Last Updated: Apr 15, 2024 2:39 AM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/WritingGuides

Eberly Center

Teaching excellence & educational innovation.

Students lack discipline-specific writing skills

Good writing in one discipline is not necessarily good writing in another. Indeed, effective writing for one task (e.g., a grant proposal) is not necessarily effective for another task (e.g., a journal article or article in the popular press) even within the same discipline.

Students may have reasonably good writing skills yet not be conversant with the writing conventions in your discipline. Moreover, even though students may have read papers or books exemplifying the writing style of your discipline, this does not guarantee that they can reproduce it in their own writing. Research has shown this phenomenon holds fairly generally: it is easier to comprehend new information or a new style of presentation than it is to generate it.

Students may bring with them habits from other disciplines that are not appropriate in yours. For example, students familiar with expressive styles of writing (from English or creative writing) may bring these habits into scientific or engineering contexts where writing concisely is more appropriate. A subtler example arises in a discipline such as anthropology where many pieces of writing do not follow the argument/evidence format used in history writing or the persuasive style of a political piece of writing, but rather a description/interpretation framework.

Strategies:

Identify the key features of writing in your discipline., make your expectations explicit., model how you approach writing tasks..

Point out to students the characteristic features of writing in your discipline. For example, in an introductory anthropology class, you might point out that authors often identify a cultural assumption that they then challenge using cross-cultural evidence. Having identified this trope, you might ask students questions (in homework or in discussion) that require students to identify these characteristics in their readings (e.g., What assumption was the author challenging? What cross-cultural evidence did she employ to do it?).

Also point out variations in writing conventions within your discipline, and give students practice recognizing the features of different kinds of writing. For example, in a dramaturgy class, you might ask students to analyze the characteristics of an effective drama review vs. a persuasive academic article. This kind of exercise makes students more conscious of different conventions within the same discipline and better able to apply them in their own writing.

There is tremendous variation among disciplines in writing styles, citation conventions, etc. Thus, it is only fair to clarify to students what styles and conventions are appropriate for your discipline and course. For example, you might specify that you want students to use MLA style for citations and direct them to appropriate examples or references. In an engineering class, you might choose to emphasize clarity and parsimony by explaining their value in engineering writing, giving examples of clear, concise writing, and designing your grading criteria to give weight to this expectation. Performance rubrics can help to make explicit what aspects of writing are particularly valued in your discipline.

Help students see how experts in your discipline approach writing by modeling how you do it:

- What questions do you ask yourself before you begin? (You might, for example, ask: Who is my audience? What am I trying to convince them of? What do I want to say, and what evidence can I use to back it up?)

- How do you go about writing? (Do you sketch out ideas on scrap paper? write an outline? hold off on writing your introductory paragraph until you have written the body of the paper?)

- How do you go about diagnosing problems and making revisions in your writing? (Do you ask a friend to read and comment on your work? Do you step away from the paper for a day and return to it with fresh eyes?)

This is not always easy: the instructor must become aware of and then make explicit the processes she engages in unconsciously and automatically. However, it is a useful exercise, illuminating to both you and your students the complex steps involved in writing and revising.

This site supplements our 1-on-1 teaching consultations. CONTACT US to talk with an Eberly colleague in person!

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Understanding Disciplinary Expectations for Writing

Dawn Atkinson

Chapter Overview

As a college student, you will likely be exposed to various disciplines , or fields of study, as you take a range of courses to complete your academic qualification. This situation presents an opportunity to diversify your knowledge and skill sets as you engage with ideas, theories, texts, genres, writing conventions, and even referencing and formatting styles that may differ from what you are already familiar with. Furthermore, as your courses become more specialized, your instructors will probably insist that your writing reflect the disciplinary expectations of your field. The ability to produce texts in line with disciplinary requirements is a mark of professionalism that will serve you well as you enter the workplace.

Although this chapter cannot outline the disciplinary expectations for writing in every field, it can encourage you to explore what texts are written in your field of interest and how they are composed. The understanding that different disciplines have different expectations for writing is a crucial first step in this discovery process.

Making Disciplinary Connections between Academic and Professional Work

To initiate your exploration of disciplinary expectations for writing, read the following text, adapted from Stanford and Jory’s (2016) chapter entitled “So You Wanna Be an Engineer, a Welder, a Teacher? Academic Disciplines and Professional Literacies.” The authors are faculty in the Department of English, Linguistics and Writing Studies at Salt Lake Community College. Think about your responses to the text as you read.

Many people today arrive at college because they feel it’s necessary. Some arrive immediately after high school, thinking that college seems like the obvious next step. Others arrive after years in the workforce, knowing college provides the credentials needed to advance their careers. And still others show up because college is a change, providing a way out of less than desirable life conditions.

We understand this tendency to view college as a necessary part of contemporary life. We did too as students. And now that we’re teachers, we still believe it’s necessary because we know it opens doors and grants access to new places, people, and ideas. And these things present opportunities for personal and professional growth. We hear about these opportunities every day when talking with our students.

But viewing college simply as a necessity can lead to a troublesome way of thinking about what it means to be a student. Because so many students today may feel like they must go to college, their time at school may feel like part of the daily grind. They may feel like they have to go to school to take classes; they may feel like they are only taking classes to get credit; and they may feel like the credit only matters because it earns the degree that leads to more opportunity. When students carry the added pressure of feeling like they must earn high grades to be successful learners and eventually professionals (we don’t think this is necessarily true, by the way), the college experience can be downright stressful. All of these things can lead students to feel like they should get through school as quickly as possible so they can get a job and begin their lives.

Regardless of why you find yourself enrolled in college courses, we want to let you know that there are productive ways to approach your work as a student in college, and we argue they will pay off in the long run.

Students who see formal schooling as more than a means to an end will likely have a more positive academic experience. The savviest students will see the connections between disciplines, literacy development, professionalism, and their chosen career path. These students will have the opportunity to use their time in school to transform themselves into professionals in their chosen fields. They will know how to make this transformation happen and where to go to do it. They’ll understand that disciplinary and professional language matters and will view school as a time to acquire new language and participate in new communities that will help them meet their goals beyond the classroom. This transformation begins with an understanding of how the language and literacy practices within your field of study, your discipline, will transfer to your life as a professional.

Even students who are unsure about what to study or which professions they may find interesting can use their time spent in school to discover possibilities. While taking classes, for instance, they might pay attention to the practices, ideas, and general ways of thinking about the world represented in their class lectures, readings, and other materials, and they can consider the ways that these disciplinary values intersect with their own life goals and interests.

UNDERSTANDING DISCIPLINARITY IN THE PROFESSIONS

When you come to college, you are not just coming to a place that grants degrees. When you go to class, you’re not only learning skills and subject matter; you are also learning about an academic discipline and acquiring disciplinary knowledge. In fact, you’re entering into a network of disciplines (e.g., engineering, English, and computer science), and in this network, knowledge is produced that filters into the world, and in particular, into professional industries. An academic discipline is defined as a field of knowledge within the university system with distinct problems and assumptions, methodologies, and ways of communicating information.1 (Think, for instance, about how scientists view the world and conduct their studies of things in the world in ways different than historians do.)

Entering into a discipline requires us to become literate in the discipline’s language and practice. If membership in a disciplinary community is what we’re after, we must learn to both “talk the talk” and “walk the walk.” At its foundation, disciplinarity is developed and supported through language—through what we say to those within a disciplinary community and to those outside of the community. Students begin to develop as members of a disciplinary community when they learn to communicate with the discipline’s common symbols and genres, when they learn to “talk the talk.” In addition, students must also learn the common practices and ways of thinking of the disciplinary community in order to “walk the walk.”

The great part of being a student is that you have an opportunity to learn about many disciplinary communities, languages, and practices, and savvy students can leverage the knowledge and relationships they develop in school into professional contexts. When we leave our degree programs, we hope to go on the job with a disciplined mind—a disposition toward the world and our work that is informed by the knowledge, language, and practices of a discipline.

Do you ever wonder why nearly every job calls for people who are critical thinkers and have good written communication skills? Underlying this call is an interest in disciplined ways of thinking and communicating. Therefore, using schooling to acquire the knowledge and language of a discipline will afford an individual with ways of thinking, reading, writing, and speaking that will be useful in the professional world.2 The professions extend from disciplines and in turn, disciplines become informed by the professionals working out in the world. In nursing, for example, academic instructors of nursing teach nursing students the knowledge, language, and practices of nursing. Trained nurses then go out to work in the world with their disciplined minds to guide them. At the same time, nurses working out in the world will meet new challenges that they must work through, which will eventually circle back to inform the discipline of nursing and what academic instructors of nursing teach in their classrooms.

It is important to realize that not all college professors and courses will “frame” teaching and learning in terms of disciplinarity or professionalism, even though it informs almost everything that happens in any classroom. As a result, it may be difficult to see the forest for the trees. Courses can become nothing more than a series of lectures, quizzes, assignments, activities, readings, and homework, and there may be few identifiable connections among these things. Therefore, students who are using school to mindfully transform into professionals will build into their academic lives periodic reflections in which they consider their disciplines and the ways they’re being trained in disciplinary thinking. They might stop to ask themselves: What have I just learned about being a nurse? About thinking like a nurse? About the language of nursing? This reflection may happen at various times throughout individual courses, after you complete a course, or at the end of completing a series of courses in a particular discipline. And don’t ever underestimate the value of forming relationships with your professors. They’re insiders in the discipline and profession and can provide great mentorship.

Okay, okay. Be more mindful of your education so that you acquire disciplinary and professional literacies. You get it. But what can you do—where can you look specifically—to start developing these literacies? There are many possible responses, but as writing teachers we will say this: Follow your discipline’s and profession’s texts. In these texts—and around them—is where literacy happens. It’s where you’re expected to demonstrate you can read and write (and think and act) like a professional.

PROFESSIONAL LITERACY: READING AND WRITING LIKE A PROFESSIONAL

So you wanna be a teacher, a welder, an engineer? Something else? It doesn’t matter what profession you’re interested in. One thing that holds true across all professions is that, although the types of reading and writing will differ, you’ll spend a great deal of time reading and writing. Your ability to apply, demonstrate, and develop your reading and writing practices in school and then on the job will contribute greatly to your success as a professional.

You may be thinking, “I’m going to be a culinary artist and want to open a bakery. Culinary artists and bakers don’t have to know how to read and write, or at least not in the ways we’re learning to read and write in school.” While you may not write many academic essays after college, we can confidently say that you will be reading and writing no matter your job because modern businesses and organizations—whether large corporations or mom-and-pop startups—are built and sustained through reading and writing. When we say reading and writing builds and sustains organizations we mean that they produce all the things necessary to run organizations—every day. Reading and writing reflect and produce the ideas that drive business; they record and document productivity and work to be completed; they enable the production and delivery of an organization’s products and services; they create policies and procedures that dictate acceptable behaviors and actions; and perhaps most importantly, they bring individuals into relationships with one another and shape the way these people perceive themselves and others as members of an organization.

As a professional, you will encounter a variety of texts; you will be expected to read and respond appropriately to texts and to follow best practices when producing your own. This holds true whether you aspire to be a mechanic, welder, teacher, nurse, occupational health and safety specialist, computer programmer, or engineer. If you bring your disciplined mind to these reading and writing tasks, you will likely have more success navigating the tasks and challenges you meet on a daily basis.

We hope this reading can transform the way you understand the discipline-specific ways of reading, writing, thinking, and using language that you encounter in all your college courses—even if these ways are not always brought to the forefront by your instructors. We might think of college courses as opportunities to begin acquiring disciplinary literacy and professional reading and writing practices that facilitate our transformation into the professionals we want to become. Said another way, if language is a demonstration of how we think and who we are, then we want to be sure we’re using it to the best of our ability to pursue our professional goals and interests in the 21st Century.

- The term “discipline” refers to both a system of knowledge and a practice. The word “discipline” stems from the Greek word didasko (teach) and the Latin word disco (learn). In Middle English, the word “discipline” referred to the branches of knowledge, especially medicine, law, and theology. Shumway and Messer-Davidow, historians of disciplinarity, explain that during this time “discipline” also referred to “the ‘rule’ of monasteries and later to the methods of training used in armies and schools.” So the conceptualization of “discipline” as both a system of knowledge and as a kind of self-mastery or practice has been around for quite some time. In the 19th century, our modern definition of “discipline” emerged out of the many scientific societies, divisions, and specializations that occurred over time during the 17th and 18th centuries. Our modern conception of disciplinarity frames it not only as a collection of knowledge but also as the social practices that operate within a disciplinary community.

- The basic relationship between disciplines and professions is that disciplines create knowledge and professions apply it. Each discipline comes with a particular way of thinking about the world and particular ways of communicating ideas. An experienced mathematician, for example, will have ways of thinking and using language that are distinct from those of an experienced historian. The professions outside of institutions of higher education also come with particular ways of thinking and communicating, which are often informed by related academic disciplines. So an experienced electrician will have ways of thinking and using language that are different from those of an experienced social worker. Both the electrician and the social worker could have learned these ways of thinking and using language within a discipline in a formal school setting, although formal schooling is not the only place to learn these ways of thinking and communicating.

Mansilla, V.B., and Gardner, H. (2008). Disciplining the Mind. Educational Leadership, 65(5), 14-19.

Russell, D.R., and Yanez, A. (2003). Big Picture People Rarely Become Historians’: Genre Systems and the Contradictions of General Education. In C. Bazerman and D.R. Russell (Eds), Writing Selves/

Writing Societies: Research From Activity Perspectives (331-362). Fort Collins, Colorado: The WAC Clearinghouse.

Shumway, D.R., and Messer-Davidow, E. (1991). Disciplinarity: An Introduction. Poetics Today, 12(2), 201-225.

Having read Stanford and Jory’s text, now work in small groups to answer the following questions about it. Be prepared to discuss your answers in class.

What are your reactions to the text?

How does the text compare with your own ideas about college and professional work?

What differences do you notice between the text and the writing advice given in this textbook? How might the differences be attributable to varying disciplinary conventions?

Using a Writing Sample to Explore Disciplinary Expectations

Journal articles , peer-reviewed reports of research studies, are expected to follow the conventions for writing in specific fields. Thus, they are useful artifacts for study when trying to identify disciplinary expectations.

To gain insight into disciplinary expectations for writing in your field, locate a journal article that focuses on your area of study. If you have not yet decided upon a major, find a journal article about a topic that interests you. Ask a librarian or your instructor for assistance if you need help finding an article.

Next, use the following handout, produced by Student Academic Success Services, Joseph S. Stauffer Library at Queen’s University (2018), to work with the article.

Analyzing disciplinary expectations tool

Now compare what you found out about disciplinary expectations for writing in your field with what your classmates discovered. Your instructor may ask you to work in a group with peers who are studying similar or different subjects. Present your group’s findings in a brief, informal presentation to the class.

Continuing Exploration of Disciplinary Expectations for Writing

The sources below provide further information about disciplinary expectations for writing. Consult these resources to learn more about writing in your field of interest.

Centre for Writing and Scholarly Communication. (n.d.). Academic and professional writing resources . The University of British Columbia. https://learningcommons.ubc.ca/improve-your-writing/writing-resources/

Debby Ellis Writing Center. (n.d.). Writing for different disciplines . Southwestern University. https://www.southwestern.edu/offices/writing/writing-for-different-disciplines/

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020). Writing in the disciplines . https://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-in-the-disciplines/

Fred Meijer Center for Writing & Michigan Authors. (2019). Writing in your major . Grand Valley State University. https://www.gvsu.edu/wc/writing-in-your-major-49.htm

Harvard Writing Project. (2020). Writing guides . Harvard University. https://writingproject.fas.harvard.edu/pages/writing-guides