An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.7(8); 2021 Aug

Attitudes and empathy of youth towards physically disabled persons

Associated data.

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

The present study aimed to investigate the attitude and empathy of youth towards physically disabled persons. This study followed a quantitative paradigm. The sample comprised of 100 participants (Male = 50; Female = 50) who were under the age range of 18–25 years. Purposive sampling was taken to gather the data. Attitudes Towards Disabled Persons (ATDP) Scale and the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire were administered on the participants. All the responses were entered on the SPSS software which was analysed through descriptive statistics, t-test, and Pearson's correlation. Findings of this study showed that both males and females had negative attitude towards physically disabled person. Furthermore, males and females were equally empathetic towards physically disabled person. Consequently, there were no gender differences in the attitude and empathy of youth towards physically disabled persons. Also, significant and positive correlation was seen between the two constructs, i.e., attitude and empathy. These results indicated a need of destigmatization about disability especially physical disability in the society.

Attitude; Empathy; Disability; ATDP; Social psychology.

1. Introduction

Disability is described as a physical or a mental health condition which hampers an individual's capacity to carry out day-to-day activities. As per WHO, it is estimated that the aggregate amount of persons with disabilities has already exceeded one billion ( WHO, 2011 ). In India, as per the 2011 Census, there are about 2.68 Crore people who are ‘disabled’ which is approximately 2.21% of the whole population ( Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities, 2016 ; Verma et al., 2016 ). The condition of differently abled people, especially in developing countries like India, is distressing. Regardless the laws and protection provided by government and its agencies, there is an immense stigma associated with disability, and differently abled persons are still seen as dependent persons and are even denied of their basic human rights, including education, employment and movability ( Janardhana and Naidu, 2011 ). Sometimes, the families of disabled person deny that their family member is differently abled because of the fear of losing social status and reputation in society ( Janardhana et al., 2015 ). Basically, disability itself has become a ‘sin’ or ‘taboo’ in the Indian society. Further, there aren't even proper laws which allow disabled people to property rights. The social attitudes of citizens of the country have led to policies by policy makers which aren't favorable to the disabled section of the population.

It is a well-known that attitude has intertwined into the fabric of our daily lives and has become a vital element in the field of social psychology. Renowned social psychologist, Gordon Allport, had dubbed attitude as ‘the primary building stone in the edifice of social psychology’ ( Allport, 1954 ). Whereas, empathy is referred to as an emotional response to the perceived predicament of other person. It is viewed as the ability to experience similar emotions as that of the other person. Howbeit, it is crucial to note that empathy is the genesis that leads to attitude change. This change has become a necessity in our society especially towards certain individuals, groups or communities and thus, the present paper focuses one such group, that is, physically disabled persons. The aforementioned persons are viewed with negative attitude and apathy. In one research, the attitudes of pre-service teachers of Jordan and UAE towards persons with disabilities were explored. The findings exhibited negative attitudes of teachers towards disabled persons ( Alghazo et al., 2003 ).

Therefore, the current paper provides the perception of youth in terms of attitude and empathy towards physically disabled people. Thus, the present research is imperative for the destigmatization of the affected group which is still experiencing exclusion ( Morris, 1991 ) and is vulnerable in the society. Also, the need for modifications in the national policies for persons with disabilities (PWD) laid by the government of India is emphasized.

1.1. Attitude

The word ‘Attitude’ has been derived from the Italian word ‘Attitudine’ which means ‘Attitude, or Aptness’, but this word was originally adapted from the Latin word ‘Aptus’ which means ‘fit, or posture’. Attitude has multiple meanings, but in general, it has an orientation towards actions, or responses. Allport (1935) has defined attitude as, “a mental or neural state of readiness, organized through experience, exerting a directive or dynamic influence on the individual's response to all objects and situations to which it is related”. In the world of social psychology, attitude is used to predict the action of persons. Attitude is divergent from human behavior; this means, as stated by Leon Festinger (1954) that the individual behavior is hardly affected by their changing attitude. Further, attitude can be positive, negative or neutral. For instance, a person may believe that disabled individuals have low intelligence (negative attitude), or a person who practices the art of meditation is healthy (positive attitude).

Furthermore, it has three core dimensions which accumulate to form the well-known ABC model of attitude: Affect (feelings), behavior tendency, and cognition (thoughts). Each of these dimensions is interlinked to one another. These components are also known as the tri-component view (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993). The affective element involves emotional reactions; the behavioral element involves one's predisposition or intention to act in such way that it depicts his/her attitude; and the cognitive element showcases the beliefs and thoughts towards the object of attitude. This model has an underlying assumption: there should be consistency between feelings, beliefs and actions of a person. If a disturbance occurs, then it will lead to anxiety and tension and the individual will try to bring his/her system back to equilibrium. On the contrast, LaPiere inflicted in his study that cognitive and affective component do not always match with behavior ( LaPiere, 1934 ).

Nevertheless, attitude can be summed as evaluation of one's thoughts, beliefs and emotions towards the object or phenomenon, which may be dispositional, constructive or stable memory structures.

1.2. Disability

Disability occurs once in every normal individual's life. It can occur in anybody's old age, childhood, adulthood, or at birth. A person can be disabled for a lifetime or acutely for a short period. Generally, the term disability denotes any relatively chronic impairment of function. When someone is unable to perform one or more activities, which are generally accepted as necessary components of daily living such as self-care, social relationship and economic productivity, such condition is suggestive of disability ( The Japanese Society for Rehabilitation of the Disabled, 1988 ).

The WHO's World report on disability ( World Health Organization, 2011 / 2001 ) depicts disability as dynamic interplay between health conditions and contextual factors, both personal and environmental. In layman terms, the report portrayed disability as a phenomenon which hampers an individual physically, emotionally and mentally as well as socially in both private and public life. More specifically, it is a disturbance in the ‘bio-psycho-social’ model. The Government of India has defined disability as an existing difficulty in performing one or more activities, which are according with an individual's age, sex and normative social role, are generally accepted as crucial basic component of daily living, such as self-care, social relations and economic activity ( Government of India, Ministry of Welfare, 1986 ).

Basically, a person is labeled as a disabled or handicapped based on his/her appearance which is a stigmatized or stereotypical view of the society at large. Disabled persons are perceived as people who cannot perform daily tasks smoothly and such labeling is stamped on all types of disabled persons without knowing their disability. A disability can be cognitive, physical, metal, sensory, developmental, emotional, and at times mixture of few of these. A person can only be called disabled when s/he is unable to perform certain functions of his/her daily life.

1.2.1. Disability and psychology

In today's scenario, disability and psychology are assumed to go hand-in-hand. Disabled individuals go through a lot of discrimination and stigmatization in their routinely lives which causes a lot of mental damage and at times trauma. The World Disability Report ( WHO, 2011 ) has reported the following data on the same:

- • Negative attitude and behavior towards disabled persons causes negative consequences on disabled persons, such as low self-esteem and reduced participation.

- • Disabled persons are harassed for their disability thus, leading social avoidance.

- • Women with disability are less likely to get married to non-disabled person due to social judgement.

- • Kids with disabilities are unlikely to attend schools. Thus, experiencing limited opportunity for employment and decreased productivity in adulthood.

- • Households with a disabled member are more likely to experience material hardship, sanitation issues, accessibility issue with healthcare and so on.

- • Poverty increases the risk of disability.

In addition, disabled persons are rarely viewed in movies or televisions and if they are given a place in the entertainment media, then they are portrayed negatively in society which effects disabled person's self-perception, and also how they are perceived by other persons. Thomas (1999) had found that some disabled individuals internalise the negatively shown social values about disability or among their relationships with family, peers, professionals, or strangers.

1.3. Physical disability

Physical disability is a physical condition which affects the person's mobility, capacity, dexterity or endurance. It is related to the limitation that a person experiences which hampers the overall functioning of that individual. It is also cited as the incapacitation in an individual's physical or mental function resulting from pathological conditions as viewed and reacted within the socio-environmental context ( Safilos-Rothschild, 1970 ). Williams (1984) , Radley (1993) and Bozo (2009) have explained that people can make sense of their disabilities through the context of their personal biographies which in turn must be influenced by and tangled in with, the cultural values of the society in which they reside in. This statement clears that any disability is part of the function of the society which is failed to given recognition. Thus, terms like ‘disabled’, ‘special’, or ‘handicapped’ prevail to exist because they are not physically constructed, but also socially constructed. Nonetheless, physical disability has significant consequences on social relationships, mental health and well-being of a person. For instance, blindness limits a person's mobility and thus, the person is heavily inclined upon other people to finish his/her daily tasks. This causes the blind person to demand diverse things from others which makes him/her an object of ridicule. This affects the disabled person's social relationships and this person even questions his/her identity as a human being and also questions their sense of self.

Since physical disabled individuals are judged based on their appearance, they are viewed as a misfortune or even personal disasters. Consequently, these people react to such opinions by denying their existence and try to pursue their life as “normal” people. Many deaf people even try to hide their deafness by pretending to hear. But, there are some people who accept their physical disability and don't fall into hopelessness and despair and showcase their worth in the society. Yet, these persons are mocked for using their health condition as an excuse for privilege which is not so. Ludwig and Collette (1970) have pointed out that social isolation, economic and personal dependency affects the mental health of disabled persons. Overall, these factors affect their quality of life.

1.3.1. Categories of physical disability

The denotation of physical disability varies across countries and so thus the categorization of physical disability. The Government of India, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, has provided with the following categorization of physical disability:

Physical Disability (as per the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016)

- i. Leprosy Cured Person

- ii. Cerebral Palsy

- iii. Dwarfism

- iv. Muscular Dystrophy

- v. Acid Attack Victims

- i. Blindness

- ii. Low Vision

- ii. Hard of Hearing

- D. Speech and Language Disability

On the other hand, National Educational Association of Disabled Students (NEADS) of Canada has given a totally contradictory categorization of physical disability, that is,

Physical Disability (as per NEADS, 2005 )

- 1. Paraplegia

- 2. Quadriplegia

- 3. Multiple sclerosis (MS)

- 4. Hemiplegia

- 5. Cerebral palsy

- 6. Absent limb/reduced limb function

- 7. Dystrophy

In addition, International Classification of Disease, 10 th revision [ICD-10] ( Diagnostic Codes Related to Family Infant Toddler (FIT) Program, 2015 ; WHO, 1980 ) has provided with a list of codes which connote the health conditions under the category of Physical Impairment ( Table 1 ).

Table 1

ICD-10 Codes for Physical Impairments.

1.4. Empathy

Empathy has been procured from the German word, Einfühlung , which means “feeling into”. Empathy is referred to as an emotional response to the perceived predicament of other person. It is viewed as the ability to experience similar emotions as that of the other person. In positive psychology, empathy is studied along with egotism, and a balance in egotism and empathy is perceived to be a portal towards altruism, forgiveness and gratitude. Egotism infers to the motive that a person pursues either for personal gain or benefit through certain behavior ( Baumister and Vohs, 2007 ). Altruism is the behavior that is aimed at benefitting another person which can be invoked through personal egotism or empathic desire to help another person. Gratitude is the appreciation of the actions of another person and forgiveness is “a freeing from negative attachment to the source that has transgressed against a person” ( Thompson et al., 2005 ). However, renowned philosophers such as Aristotle (384-322 BC), Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) or psychologists as Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) had debated whether empathy, or egotism, or both fuel prosocial human behavior.

Social psychologist, Batson et al. (2002) do not deny that certain forms of altruistic behavior can be exhibited by egotism, but they also believe that under some situations, egotism cannot be motivated for helping. Thus, he gave rise to the empathy-altruism hypothesis which explains that under some instances the desire of “pure” empathy is required for helping other individuals, not egotism. Piliavin and Chang have opined ( 1990 ), “There appears to be a paradigm shift away from the earlier position that behavior that appears to be altruistic must, under closer scrutiny, be revealed as reflecting egoistic motives. Rather, theory and data now being advanced are more compatible with the view that true altruism – acting with the goal of benefiting another – does exist and is part of human nature.”

In sum, human being don't only behave in particular ways just to attain benefits, but they also behave in peculiar ways just for the sake of helping individuals in their turbulent times and out of empathy.

1.4.1. Types of empathy

Empathy is significant in order to form and maintain different forms of social relationships, and also helps in the development of prosocial behaviors ( Roberts et al., 2014 ). However, empathy varies person to person, that is, empathy is categorized into two categories: cognitive and affective empathy. Cognitive empathy is the extent to which one successfully guesses someone's thoughts and feelings ( Wlodarski, 2015 ). This is more associated with visual perspective taking or complex mental challenges such imagining what the other person might be thinking. Also, greater cognitive empathy is known as empathic accuracy, where an individual has the precise knowledge of the contents of the other person's mind (also involves the feelings of that other person). On the other hand, affective empathy is inclined towards the emotional aspect of an individual. Hence, it is also called emotional empathy, which is sub-categorised into three components: i. emotional contagion (having the similar feeling as that of another person); ii. Personal distress (one's own feelings of distress in reaction to perceiving another's plight); and iii. Empathic concern/sympathy (the feeling of compassion towards another person). All of these accumulate to form emotional empathy. However, in social psychology, affective component of empathy is studied and shown more reliance than cognitive empathy as cognitive empathy might be linked to false consensus effects and other egocentric view of social psychology. For instance, in a study by Hynes et al. (2005) , found a differential role of the orbitofrontal cortex in affective and cognitive empathy. They saw that the medial orbitofrontal cortex was more engaged in affective empathy rather than cognitive empathy.

Furthermore, affective and cognitive empathy show possible differences in their executive functions. Executive function refers to a set of mental skills which is composited of working memory, self-control and flexible thinking. These skills are used on day-to-day basis such in planning, remembering, learning, or managing certain tasks. Miyake and colleagues (2000) have posited three subdomains of executive functions, that is, mental set shifting, inhibitory control, and information updating and monitoring. Each of these functions is stimulated by different brain regions to perform diverse functions, like attention. Also, both of these types are considered to be necessary for a successful social interaction to take place.

1.4.2. The biological evidence behind empathy

The foremost genetic hereditary of empathy was traced through twin studies. Studies have shown monozygotic twin correlations in the range of .22–.30 in comparison to dizygotic correlations with the range of .05–.09 ( Davis et al., 1994 ; Zahn-Wexler et al., 1992 ). Another study has showed the correlations of monozygotic and dizygotic adult male twins -.41 and .05, respectively ( Matthews et al., 1981 ).

Neural based studies have shown that the particular areas of the prefrontal and parietal cortices seem to be crucial for empathy ( Damasio, 2002 ). Bechara et al. (1996) have elaborated that any damage to the prefrontal cortex leads to impairment in the appraisal of emotions of other people. Neuroscientist, Giacomo Rizzolatti, the discoverer of mirror neurons, has said that “neurons could help explain how and why we….feel empathy” ( Winerman, 2005 ).

2. Objectives

- 1. To examine the attitudes among youth towards physically disabled persons.

- 2. To investigate the effect of empathy among youth towards physically disabled persons.

- 3. To study the relationship between attitudes and affective empathy among youth towards physically disabled persons.

3. Hypothesis

H1: There will be a significant difference between the attitudes of males and females towards physically disabled person.

H2: There will be a significant difference between the empathy of males and females towards physically disabled person.

H2: There will be a significant relationship between the attitudes and empathy among youth towards physically disabled persons.

H4: There will be a significant relationship between attitudes and the subtypes of affective empathy among youth towards physically disabled persons.

4.1. Design of the study

This study followed quantitative design. Further, the design of the study adopted is between group designs, more specifically, two-randomized-group design. Furthermore, this study administered ‘Attitudes Toward Disabled Persons Scale’ to measure attitude and ‘The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire’ to measure empathy. Descriptive statistics, Independent sample t-test and Pearson's Correlation were used to analyse the responses. Gender (Male and Female) was the independent variable, whereas attitude and empathy towards physically disabled persons were dependent variables.

4.2. Sample

The present study comprises 100 participants. The sample taken was the Indian youth under the age range of 18–25 years old, residing in India. The sample was divided into two parts: Males (50%) and Females (50%). The responses were taken from various social networking sites like WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram through the distribution of questionnaires from Google forms. Purposive sampling was used to collect the data.

In addition, a priori power analysis was conducted using G∗power3 ( Faul et al., 2007 ) to test the difference between two independent group means using a two-tailed test, a large effect size (d = 2.1), and an alpha of .05. Result showed that a total sample of 10 participants was required to achieve a power of .80. This sample size was required in the case of Attitude.

Likewise, another priori power analysis was conducted in the case of Empathy using G∗power3 ( Faul et al., 2007 ) to test the difference between two independent group means using a two-tailed test, a large effect size (d = 0.9), and an alpha of .05. Result showed that a total sample of 42 participants was required to achieve a power of .80. Thus, our proposed sample size of 100 was adequate for the objectives of this study.

4.3. Measures

Two scales were utilized in this study to examine the attitude of youth towards physically disabled persons, and their empathy towards them. Firstly, the scale for attitude was ‘Attitudes Toward Disabled Persons Scale’ (ATDP), which was given by Yuker, Block and Younng (1970). This scale has three different forms: ATDP-O, ATDP-A and ATDP-B. However, for the current study, ATDP-O was utilized. The ATDP-O Scale consists 20 statements to which the participants choose from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree, using a six point Likert Scale. The administration of this questionnaire takes up to 15 min. The reliability was this scale was established through four means: test-re-test, parallel, split-half test, and covariance of test items. ATDP has an average reliability coefficient of .80 ( Yuker and Block, 1986 ). Further, the content validity of this scale was established through literature view, and item analysis. The criterion and construct validity was made by comparisons with other attitude scales. Scores for the ATDP-O Scale ranged from 0 to 120. The interpretation of the scores depends on the perception of respondents, that is, whether they perceive disabled persons as same as non-disabled persons or not.

Secondly, the scale for empathy utilized was ‘The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire’ (TEQ) which was given by Spreng et al. (2009). TEQ Scale is a questionnaire made to measure empathy with a focus on the emotional component, and consists of 16 items. However, the cognitive component for this scale was mutually exclusive. The scale has a good internal consistency of .87, and depicted high test-retest reliability of .81. Also, the convergent validity was good in comparison to other self-report empathy scales. Since this scale is a 5-point rating scale, the scoring for all the items was direct (Never = 0, Rarely = 1, Sometimes = 2, Often = 3, Always = 4), except for items 2, 4, 7, 10, 12, 14, and 15, in which the scoring was reverse. High scores indicated high level of self-reported empathy with the range of scores between 43.46 to 44.45 for males, and 44.62 to 48.93 for females.

4.4. Procedure

The ATDP-O and TEQ questionnaires were made on Google Forms and were distributed online through various social networking applications like WhatsApp, Facebook and Instagram, and via e-mail. The participants were mainly young individuals under the age range of 18–25 years old, and purposely University students were approached through virtual media as they met the required sample criterion which was of interest for this study. The sample was assured that their reactions would be kept confidential and all the data was recorded respectively. Later, the participants were debriefed after they finished the questionnaire. The scores of the respondents were then uploaded on SPSS and their scores were analyzed through Descriptive Statistics, Independent sample t-test and Pearson's Correlation, and the results were obtained.

4.5. Approving Ethical Committee

The present research was approved by the Department of Applied Psychology, Shyama Prasad Mukherji College of Women, University of Delhi.

The current study investigated the attitudes and empathy of youth towards physically disabled persons. Furthermore, the gender differences were examined in this study. The study involved a sample of 100 individuals, that is, 50 males and 50 females in the age range of 18–25 years. Purposive sampling was the sampling techniques used in this study. The responses attained were uploaded on SPSS software and descriptive statistics, independent sample t-test and Pearson's correlation was applied on the responses. Gender (male and female) was the independent variable, and attitude (ATDP – Attitude towards Disabled Persons) and empathy were the dependent variables. Finally, the results were obtained which are elaborated below.

5.1. Attitudes of youth towards physically disabled person

For the first hypothesis, the findings revealed that there was no statistically significant difference in the attitudes of males (M = 60.24; S.D. = 1.315) and females (M = 62.86; S.D. = 1.131) towards physically disabled persons, t (98) = -1.06, p = .288.

In support for the finding, we observed that female showed negative attitude towards physically disabled persons, with the mean of 62.86 which is below than the given female mean of 75.42 (as given in the ATDP [FORM-O] manual). Further, males also had negative attitude towards physically disabled persons with the mean of 60.24 which is below than the given male mean of 72.80 (as given in the ATDP [FORM-O] manual). However, this finding also exhibits that although no significant difference between Genders was found, but it was because both had negative attitude towards physically disabled individuals (one-directional). The finding for H 1 is given in Table 2 .

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics and t-value of ATDP (Attitudes towards Disabled Persons) among youth.

5.2. Empathy of youth towards

The outcome for third hypothesis showed that there was no statistically significant difference in the empathy of males (M = 45.50; S.D. = 6.81) and females (M = 46.14; S.D. = 7.03) towards physically disabled person, t (98) = -.46, p = .645.

The result can be supported by noting that the mean range given by Toronto Empathy Questionnaire is 44.62–48.93 for females, and for males, the mean range is 43.46–44.45. Thus, the empathy result of this study was in between the given mean range, that is, females was 46.14 and males was 45.50 ( Table 3 ). Therefore, this finding showcases that although no significant difference between Genders was found, but it was because both were equally empathetic towards physically disabled people (one-directional). Interestingly, the mean of male (45.50) was higher than the given mean range, depicting a good level of self-reported empathy is assumed uncommon in males in general. The result is shown in Table 3 .

Table 3

Descriptive Statistics and t-value of Empathy among youth.

5.3. Relation between attitudes and empathy

H3: There will be significant relation between the attitudes and empathy among youth towards physically disabled persons.

The findings for this hypothesis displayed strong and positive correlation between attitudes and empathy among youth towards physically disabled persons, r = .305, n = 100, p = .002, which is depicted in Table 4 .

Table 4

Correlation between ATDP (Attitudes towards Disabled Persons) and Empathy among youth.

∗∗p < .01.

5.4. Relation between attitudes and subtypes of affective empathy

H4: There will be significant relation between attitudes and the subtypes of affective empathy among youth towards physically disabled persons.

In the last hypothesis, it was found that there was significant relation between only two subtypes of affective empathy and attitudes among youth towards physically disabled persons, that is, between emotional contagion and ATDP (r = .254, n = 100, p = .011; p < .05), and between sensitive behavior and ATDP (r = .290, n = 100, p = .003; p < .01). The result is given in Table 5 .

Table 5

Correlation between ATDP (Attitudes towards Disabled Persons) and Subtypes of Affective Empathy among youth.

∗p < .05.

6. Discussion

The goal of this study was to explore the attitudes and empathy of youth towards physically disabled persons. Attitudes are viewed as a desired or undesirable appraisal towards a particular object, phenomenon, person, or situation. Such an appraisal comes from the established beliefs, emotions, and behavior towards the object, phenomenon, person, or situation. The attitudes of youth today are mix, with some conservative and some liberal attitudes towards different concepts in life like disability. However, such forms of attitudes can be seen especially among the Indian youth, since the study includes sample of Indian youth. Nevertheless, such attitudes can also be seen in different parts of the world as well, although the youth in developed countries are assumed to be open minded, but the case is opposite of the assumption with people having mixed attitudes – some conservative, some liberal, and some neutral attitudes.

Since the study examines the attitudes of youth towards physically disabled persons, it is necessary to know the perception of people towards disability in general. As per Article 1, Convention on the Rights of persons with Disability, disability is recognized as a “long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may impede their complete and effective contribution in society on an equal basis with others”. Finkelstein (1980) has told that countries where division of classes exist, in such societies, disabled persons are looked upon as a misfortune to both the family and the person suffering from disability itself. Moreover, physically disabled person suffer the most especially in Indian society ( Bhat, 1963 ). She says that in some tribes, children with physical disability were killed at birth, and in urban cities, the concept of infanticide, that is, killing a child at birth, was practiced, especially in Asia, Africa, Oceania, and America because of their detected physical disability. Also, UNICEF has told that a disability becomes problematic when people in the society hold problematic attitudes and create environmental barriers for them.

Another crucial concept that was studied in this research was empathy towards physically disabled persons. Empathy means to understand and share the emotions of another person as if it is your own feelings. Empathy is of two types mainly: affective and cognitive empathy. The former taps the emotional empathy within the person, whereas the latter taps a person's thoughts and feelings of another person. In general, people look at any individual with disability with pity, which is basically sympathy. People think that a person with disability cannot carry out most of the life tasks, and they also are sensitive in nature. Such assumptions are false because people who are disabled, let it be physical disability can carry most of the task on their own and they are normal individuals like non-disabled persons. But, due to the lack of empathy in our society, a stigma and discrimination towards disabled pupil still prevails. Further, this study leaned more towards affective empathy, although cognitive empathy was mutually exclusive in some items of the questionnaire used (Toronto Empathy Questionnaire). The current research also used a well-known questionnaire, namely, ‘Attitudes Toward Disabled Persons’ (ATDP) Scale ( Yuker et al., 1960 ). This study used purposive sampling to attain the desired population, that is, youth, and applied descriptive statistics, Independent samples t-test and Pearson's correlation on the respective responses.

Moreover, gender differences in attitudes and empathy of youth were explored. However, no significant difference was found in the attitudes of male and females towards physically disabled persons (H 1; t = -1.06). Similarly, no significant difference was present in the empathy between males and females towards physically disabled persons (H 2; t = -.46). This is because of certain cultural factors present in our society and also because certain males and females look at disabled people with equality rather than inferior to them ( Tamm and Prellwitz, 2001 ). In a country like India, disabled individuals are seen as vulnerable and burdensome. Such an ideology arises from the Indian scriptures and folklores which has been passing on from one generation to another, and still prevails in the modernized society where laws and benefits exist for any disabled person. In India, a term called ‘Charak Sinhala’ exists which means that diseases or any sort of misfortune exists due to the result of misdeed in the previous life ( Mukherjee and Wahile, 2006 ). Even though we live in a rapid world of development and advancement, yet such ideology exists in the minds of youth today. Thus, due to such mind-sets in both the genders, getting a difference in their attitudes became difficult.

In addition, on the basis of review of literature, it was assumed that females would hold a positive attitude towards physically disabled persons (H 1 ). Contradictory, the result came out to be negative in both females as well as males, that is, no significant difference between the two genders. Similarly, Wilson and Scior (2013) did a review of past literatures on the attitudes of physical and intellectual disabilities. They found that most of the studies depicted males and females having negative attitude towards physically disabled persons. They also mentioned that it was due to the implicit attitudes of non-disabled people. Implicit attitude refers to the unintentional introspection of one's personal past experiences which mediate in favourable or unfavourable response (feelings, thoughts, behavior) towards a social object - person, thing, situation, or any phenomenon ( Greenwald and Banaji, 1995 ). Furthermore, in developing countries like India, there are several factors due to which a negative attitude has been created in the minds of youth. For instance, the superstitious traditions which still view physically disabled persons as a sin, and therefore, at times, subject disabled individuals to various detrimental treatments ( Sengupta, 1996 ). Also, prevention of physically disabled person to participate in social gathering by families, or the lack of education or employment opportunities towards the disabled sector ( Kalyanpur, 2008 ) have created a narrow mind-set in the young minds that the disabled people are more of a burden to the society than an asset itself.

Likewise to the previous hypothesis, another hypothesis was tested in this study to see whether females were more empathetic than males or not towards physically disabled persons (H 2 ). Fortunately, the findings although non-significant depicted that females and males were equally empathetic towards physically disabled people, though females slightly more empathetic than the latter. This is because girls seemed to be more sensitive and social when it comes to approaching people with disability ( Georgiadi et al., 2012 ). Also, in the present research, it was checked whether there was any significant relation between the attitudes and empathy among youth towards physically disabled persons (H 3 ). The result for this hypothesis came out to be true that there was a significant relation between the attitudes and empathy of youth towards physically disabled persons (r = .305). This means that the more empathy in a person, the more positive attitude of a person towards physically disabled persons and vice versa. Such a finding was found in another study where empathetic activities applied on nursing students in order to make their attitudes positive towards disabled persons ( Geçkil et al., 2017 ). Lastly, a statistically significant relation was tested between attitudes and subtypes of affective empathy among youth towards physically disabled persons (H 4 ). Surprisingly, the result came out be positively correlated to two subtypes of affective empathy, that is, emotional contagion and sensitive behavior. This result was interesting because some items in both the types had aspects of cognitive empathy. Emotional contagion refers to the tendency of a person to mimic and coordinate the facial expressions, vocalizations, postures, and movements with those of another individual ( Hatfield et al., 1994 ). Basically, someone's triggering of certain emotions and behaviors in other person. Whereas, sensitive behavior refers to ‘assessment of emotional states in others by indexing the frequency of behaviors demonstrating appropriate sensitivity’ ( Spreng et al., 2009 ). Both of these subtypes tap not only affective empathy, but also the thoughts and feelings of other person, that is, cognitive aspect of empathy. This showcases empathy plays a crucial role in the attitude of youth towards physically disabled persons.

Finally, the physically disabled sector of the Indian population have various unmet challenges which needs to be tackled which will help to change the attitude of youth, and alleviate their empathy towards them: the necessity to eliminate attitudinal deterrents among communities ( Janardhana and Naidu, 2012 ); the necessity to provide disabled friendly infrastructures in schools and to train teachers to provide optimal support to disabled students; the necessity to embrace a down to top approach when it comes to policy design.; the necessity to monitor and promote service outreach for disabled people below district level ( Pinto and Sahur, 2001 ); and others. Thus, an effective and extensive strategy is urgently needed by the disabled section of India which empowers them at all levels and makes them feel more accepted in the society.

7. Limitation

The study had some limitations. First, data collection became difficult due to the sudden enforcement of lockdown because of COVID-19 in the nation. Therefore, the data had to be accumulated through virtual media. Secondly, complete responses were not provided by the participants in the questionnaire which led to discarding of participants and re-sending of questionnaires to new subjects. Third, cognitive empathy was not fully tested, although some aspects of it were present in certain items of the Toronto empathy questionnaire. Fourth, data of physically disabled persons was not included. Finally, the study can be improved by increasing the number of subjects for more generalized results.

8. Future implications

The results from this study indicates that attitude plays a significant role in creating a specific impression of a person in the society especially physically disabled persons who are seen with negative attitudes and vulnerability, and also a need for empathetic people in the society. A change in the attitudes of people in the system of the society is the need of the hour. The Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities can use the findings of this study to understand the gap that exists in the implementation of the policies in diverse organizations, therefore understanding the current conditions of physically disabled persons and take necessary actions to create awareness of disability in general, and how disabled people are a valuable asset to the nation rather than misfortunes. Corporate sectors can utilize this study to understand the stigmatization and discrimination of physically disabled persons due to negative thoughts and beliefs at an organizational level, and the need for attitude-empathy intervention among employees to change their attitudes (negative if present) towards physically disabled persons into a positive one. Also, this study can be used in schools and universities in order to create positive attitudes and sensitization among students of all ages towards disabled persons and make them more empathetic as the students will be future of tomorrow.

9. Conclusion

The findings of this research provided a deeper understanding in attitude and empathy of youth towards physically disabled persons. The insights of the study showed how physically disabled people are still seen as crippled, or disadvantaged by the current youth which was surprising because we live in a world where we have accepted other communities like LGBTQ, yet the youth feels uncomfortable when it comes to disabled people. However, they are becoming more accepting with time as it was visible through the results of empathy. Still, awareness and interventions at different sectors of the society is required to normalize disability in our society.

Declarations

Author contribution statement.

Naveli Sharma: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Virendra Pratap Yadav: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Aashima Sharma: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Declaration of interests statement.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the involvement of participants in the study.

- Alghazo E.M., Dodeen H., Aliqaryouti I.A. Attitudes of pre-service teachers towards persons with disabilities: predictions for the success of inclusion. Coll. Student J. 2003; 37 (4):515–521. [ Google Scholar ]

- Allport G.W. In: Handbook of Social Psychology. Murchison C., editor. Clark University Press; Worcester, MA: 1935. Attitudes; pp. 798–844. [ Google Scholar ]

- Allport G. Addison-Wesley; Reading, Massachusetts: 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. [ Google Scholar ]

- Batson C.D., Ahmad N., Lishner D.A., Tsang J. In: The Handbook of Positive Psychology. Snyder C.R., Lopez S.J., editors. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. Empathy and altruism; pp. 485–498. [ Google Scholar ]

- Baumister R.F., Vohs K.D. Sage Publications Pvt. Ltd; California, USA: 2007. Encyclopaedia of Social Psychology. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bechara A., Tranel D., Damasio H., Damasio A.R. Failure to respond autonomically to anticipated future outcomes following damage to prefrontal cortex. Cerebr. Cortex. 1996; 6 :215–225. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bhat U. first ed. Popular Book Depot; Bombay: 1963. The Psychically Handicapped in India: A Growing National Problem. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bozo S. Ahmadu Bello University Press; Zaria, Nigeria: 2009. The Impact of Cultural Norms and Values on Disability. [ Google Scholar ]

- Damasio A.R. In: Altruism and Altruistic Love: Science, Philosophy, and Religion in Dialogue. Post S.G., Underwood L.G., Schloss J.P., Hurlbut W.B., editors. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. A note on the neurobiology of emotions; pp. 264–271. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis M.H., Luce C., Kraus S.J. The heritability of characteristics associated with dispositional empathy. J. Pers. 1994; 62 :369–391. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities . 2016. Home Acts. http://disabilityaffairs.gov.in/content/page/acts.php Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- Diagnostic Codes Related to Family Infant Toddler (FIT) Program . 2015. International Classification of Disease. https://nmhealth.org/publication/view/general/3561/ 10th Revision (ICD-10). Retrieved from: [ Google Scholar ]

- Faul F., Erdfelder E., Lang A.-G., Buchner A. G∗Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 2007; 39 :175–191. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 1954; 7 :117–140. [ Google Scholar ]

- Finkelstein V. In: Handicap in a Social World. Brechin Ann., editor. Vol. 1981. Kent Hodder and Stoughton; 1980. Attitude and disabled people: Issues for discussion , New York: world rehabilitation fund: similar views are expressed in to deny or not deny disability and disability and the helper/helped relation: an historical view; pp. 58–63. [ Google Scholar ]

- Georgiadi M., Kalyva E., Kourkoutas E., Tsakiris V. Young children's attitudes toward peers with intellectual disabilities: effect of the type of school. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2012; 25 (6):531–541. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Geçkil E., Kaleci E., Cingil D., Hisar F. The effect of disability empathy activity on the attitude of nursing students towards disabled persons: a pilot study. Contemp. Nurse. 2017 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Government of India . Ministry of Welfare; 1986. Uniform Definitions of the Physically Handicapped; p. 4. [ Google Scholar ]

- Greenwald A.G., Banaji M.R. Implicit social cognition: attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychol. Rev. 1995; 102 (1):4–27. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hatfield E., Cacioppo J., Rapson R.L. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1994. Emotional Contagion. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hynes C.A., Baird A.A., Grafton S.T. Differential role of the orbital frontal lobe in emotional versus cognitive perspective-taking. Neuropsychologia. 2005; 44 (3):374–383. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Janardhana N., Naidu D.M. Stigma and Discrimination experiences by families of mentally ill Victims of mental illness. Contemp. Soc. Work J. 2011; 3 :83–88. [ Google Scholar ]

- Janardhana N., Naidu D.M. Inclusion of people with mental illness in community based rehabilitation: need of the day. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2012; 16 :117–124. [ Google Scholar ]

- Janardhana N., Muralidhar D., Naidu D.M., Raghevendra G. Discrimination against differently abled children among rural communities in India: need for Action. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2015; 6 (1):7–11. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kalyanpur M. The paradox of majority underrepresentation in special education in India: constructions of difference in a developing country. J. Spec. Educ. 2008; 42 :55–64. [ Google Scholar ]

- LaPiere R.T. Attitudes vs. Actions. Soc. Forces. 1934; 13 :230–237. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ludwig E.C., Collette J. Dependency, social isolation and mental health in a disabled population. Soc. Psychiatry. 1970; 5 :92–95. [ Google Scholar ]

- Matthews K.A., Batson C.D., Horn J., Rosenman R.H. "Principles in his nature which interest him in the fortune of others ... ": the heritability of empathic concern for others. J. Pers. 1981; 49 :237–247. [ Google Scholar ]

- Morris J. “Us” and “them”? Feminist research, community care and disability. Crit. Soc. Policy. 1991; 11 (33):22–39. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mukherjee P.R., Waheli A.A. Lntegrated approach towards drug development from ayurveda and others Indian systems of medicines. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006; 103 (1):25–35. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- NEADS . 2005. Making Extra-curricular Activities Inclusive: an Accessibility Guide for Campus Programmers. www.neads.ca/en/about/projects/inclusion/guide/ Retrieved from: [ Google Scholar ]

- Piliavin J.A., Chang H.-W. Altruism: a review of recent theory and research. Am. Socio. Rev. 1990; 16 :27–65. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pinto P.E., Sahur N. 2001. Working with People with Disabilities an Indian Perspective. http://www.cirrie.buffalo.edu Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- Radley A. Routledge; United Kingdom: 1993. Worlds of Illness: Biographical and Cultural Perspectives on Health and Disease. [ Google Scholar ]

- Roberts W., Strayer J., Denham S. Empathy, anger, guilt: emotions and prosocial behaviour. Can. J. Behav. Sci./Rev. Can. Sci. Comport. 2014; 46 (4):465–474. [ Google Scholar ]

- Safilos-Rothschild C. Random House Inc; New York, USA: 1970. The Sociology and Social Psychology of Disability and Rehabilitation. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sengupta I. 1996. Voices of South Asian Communities. http://www.ethnomed.org/ethnomed/voices/soasia.html Retrieved from: [ Google Scholar ]

- Spreng R.N., McKinnon M.C., Mar R.A., Levine B. The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire: scale development and initial validation of a factor-analytic solution to multiple empathy measures. J. Pers. Assess. 2009; 91 (1):62–71. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tamm M., Prellwitz M. "If I had a friend in a wheelchair": children's thoughts on disabilities. Child Care Health Dev. 2001; 27 (3):223–240. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- The Japanese Society for Rehabilitation of the Disabled . 1988. Rehabilitation in Asia and the Pacific Tokyo. Tokyo. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thomas C. Open University Press; Buckingham: 1999. Female Forms: Experiencing and Understanding Disability. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thompson Dispositional forgiveness of self, others, and situations: the Heartland Forgiveness Scale. J. Pers. 2005; 73 :313–359. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Verma D., Dash P., Bhaskar S., Pal R.P., Jain K., Srivastava R.P., Hansraj Namit, Kesan H.P. Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation, Government of India; 2016. Disabled Persons in India-A Statistical Profile 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Williams G. The genesis of chronic illness: narrative reconstruction. Sociol. Health Illness. 1984; 6 :175–820. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilson M.C., Scior K. Attitudes towards individuals with disabilities as measured by the Implicit Association Test: a literature review. Elseveir. 2013; 35 :294–321. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Winerman L. Mirror neurons: the mind's mirror. Monitor. 2005; 36 :49–50. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wlodarski R. The relationship between cognitive and affective empathy and human mating strategies. Evol. Psychol. Sci. 2015; 1 :232–240. [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization . 1980. International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/41003/9241541261_eng.pdf;jsessionid=C04FF8DBBA52EEFEB8B68995E01461AB?sequence=1 Retrieved from: [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization . Disability and Health; Geneva: 2001. The International Classification of Functioning. [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization . 2011. World Report on Disability. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789240685215_eng.pdf?ua=1 Retrieved from. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yuker H.E., Block J.R. Hofstra University; NY: 1986. Research with the Attitude toward Disabled Persons Scales (ATDP) 1960-1985. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yuker H.E., Block J.R., Campbell W.J. Human Resources; NY: 1960. A Scale to Measure Attitudes toward Disabled Persons: Human Resources Study Number 5. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zahn-Wexler C., Robinson J., Emde R.N. The development of empathy in twins. Dev. Psychol. 1992; 28 :1038–1047. [ Google Scholar ]

- What is the ADA?

- ADA Anniversary

- Learn About the National Network

- Contact Your Region/ADA Center

- ADA National Network Portfolio

- ADA Success Stories

- Projects of the National Network

- Research of the National Network

- Ask ADA Questions

- View ADA Publications & Videos

- Find ADA Training

- Request ADA Training

- Search ADA Web Portal

- Federal Agencies and Resources

- Federal ADA Regulations and Standards

- Architects/Contractors

- People with Disabilities

- State and Local Government

- Emergency Preparedness

- Employment (ADA Title I)

- Facility Access

- General ADA Information

- Hospitality

- Public Accommodations (ADA Title III)

- Service Animals

- State and Local Government (ADA Title II)

- Technology (Accessible)

- Telecommunication (ADA Title IV)

- Transportation

- Region 1 - New England ADA Center

- Region 2 - Northeast ADA Center

- Region 3 - Mid-Atlantic ADA Center

- Region 4 - Southeast ADA Center

- Region 5 - Great Lakes ADA Center

- Region 6 - Southwest ADA Center at ILRU

- Region 7 - Great Plains ADA Center

- Region 8 - Rocky Mountain ADA Center

- Region 9 - Pacific ADA Center

- Region 10 - Northwest ADA Center

- ADA Knowledge Translation Center

- Substance Use and the ADA April 25, 2024

- How the ADA Applies to Addiction and Recovery April 25, 2024

- The ADA, Addiction, Recovery and Employment May 6, 2024

- Title III of the ADA and Readily Achievable Barrier Removal May 21, 2024

- Self-Evaluation Part I June 13, 2024

- Self-Evaluation Part II June 14, 2024

- Engaging Kids About Disability Through Animated Cartoons July 16, 2024

You are here

Guidelines for writing about people with disabilities.

( Printer-friendly PDF version | 311 KB) (Large Print PDF version | 319 KB) ( Spanish version )

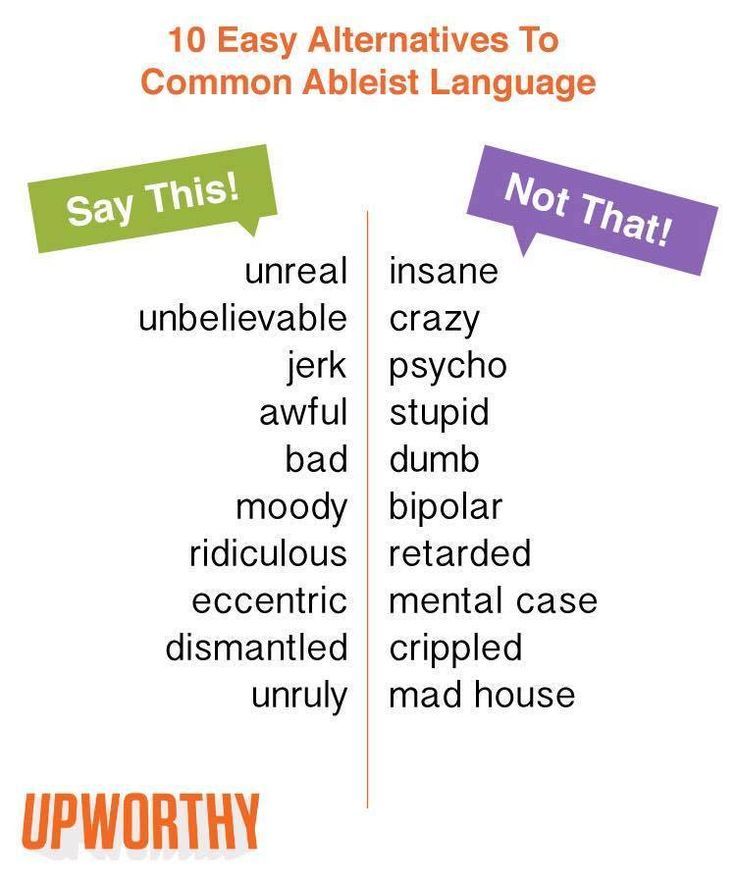

Words are powerful.

The words you use and the way you portray individuals with disabilities matters. This factsheet provides guidelines for portraying individuals with disabilities in a respectful and balanced way by using language that is accurate, neutral and objective.

1. Ask to find out if an individual is willing to disclose their disability.

Do not assume that people with disabilities are willing to disclose their disability. While some people prefer to be public about their disability, such as including information about their disability in a media article, others choose to not be publically identified as a person with a disability.

2. Emphasize abilities, not limitations.

Choosing language that emphasizes what people can do instead of what they can’t do is empowering.

3. In general, refer to the person first and the disability second.

People with disabilities are, first and foremost, people. Labeling a person equates the person with a condition and can be disrespectful and dehumanizing. A person isn’t a disability, condition or diagnosis; a person has a disability, condition or diagnosis. This is called Person-First Language.

4. However, always ask to find out an individual’s language preferences.

People with disabilities have different preferences when referring to their disability. Some people see their disability as an essential part of who they are and prefer to be identified with their disability first – this is called Identity-First Language. Others prefer Person-First Language. Examples of Identity-First Language include identifying someone as a deaf person instead of a person who is deaf , or an autistic person instead of a person with autism .

5. Use neutral language.

Do not use language that portrays the person as passive or suggests a lack of something: victim , invalid , defective.

6. Use language that emphasizes the need for accessibility rather than the presence of a disability.

Note that ‘handicapped’ is an outdated and unacceptable term to use when referring to individuals or accessible environments.

7. Do not use condescending euphemisms.

Terms like differently-abled , challenged , handi-capable or special are often considered condescending.

8. Do not use offensive language.

Examples of offensive language include freak, retard, lame, imbecile, vegetable, cripple, crazy, or psycho.

9. Describing people without disabilities.

In discussions that include people both with and without disabilities, do not use words that imply negative stereotypes of those with disabilities.

10. Remember that disability is not an illness and people with disabilities are not patients.

People with disabilities can be healthy, although they may have a chronic condition such as arthritis or diabetes. Only refer to someone as a patient when his or her relationship with a health care provider is under discussion.

11. Do not use language that perpetuates negative stereotypes about psychiatric disabilities.

Much work needs to be done to break down stigma around psychiatric disabilities. The American Psychiatric Association has new guidelines for communicating responsibly about mental health.

12. Portray successful people with disabilities in a balanced way, not as heroic or superhuman.

Do not make assumptions by saying a person with a disability is heroic or inspiring because they are simply living their lives. Stereotypes may raise false expectations that everyone with a disability is or should be an inspiration. People may be inspired by them just as they may be inspired by anyone else. Everyone faces challenges in life.

13. Do not mention someone’s disability unless it is essential to the story.

The fact that someone is blind or uses a wheelchair may or may not be relevant to the article you are writing. Only identify a person as having a disability if this information is essential to the story. For example, say “Board president Chris Jones called the meeting to order.” Do not say, “Board president Chris Jones, who is blind, called the meeting to order.” It’s ok to identify someone’s disability if it is essential to the story. For example, “Amy Jones, who uses a wheelchair, spoke about her experience with using accessible transportation.”

14. Create balanced human-interest stories instead of tear-jerking stories.

Tearjerkers about incurable diseases, congenital disabilities or severe injury that are intended to elicit pity perpetuate negative stereotypes.

People First Language and More, Disability is Natural !

Guidelines: How to Write and Report About People with Disabilities, and “Your Words, Our Image ” (poster), Research & Training Center on Independent Living, University of Kansas, 8th Edition, 2013.

Mental Health Terminology: Words Matter and “Associated Press Style Book on Mental Illness, ” American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Language:

Provide feedback on this factsheet.

1-800-949-4232

Grant Disclaimer

Accessibility

The website was last updated April, 2024

- Default Style

- Green Style

- Orange Style

Insight and inspiration in turbulent times.

- All Latest Articles

- Environment

- Food & Water

- Featured Topics

- Get Started

- Online Course

- Holding the Fire

- What Could Possibly Go Right?

- About Resilience

- Fundamentals

- Submission Guidelines

- Commenting Guidelines

Act: Inspiration

Accessibility and resilience: rebuilding a society for all bodies and needs.

By Andrei Mihail , originally published by Resilience.org

April 13, 2022

Resilience is the capacity of a system to bounce back to a previous state after a disturbance. A key concept present in many works focusing on it is the role diversity plays. A diverse system has inherent fail-safes, alternatives and redundancies which allow it to better tolerate disturbances and crisis situations. And to brave the challenges of the Anthropocene, we need to foster and protect diversity – not just in natural ecosystems but in our society as well. Yet due to our mistaken perception of disability, we isolate and devalue people that diverge from what is considered a “normal” human.

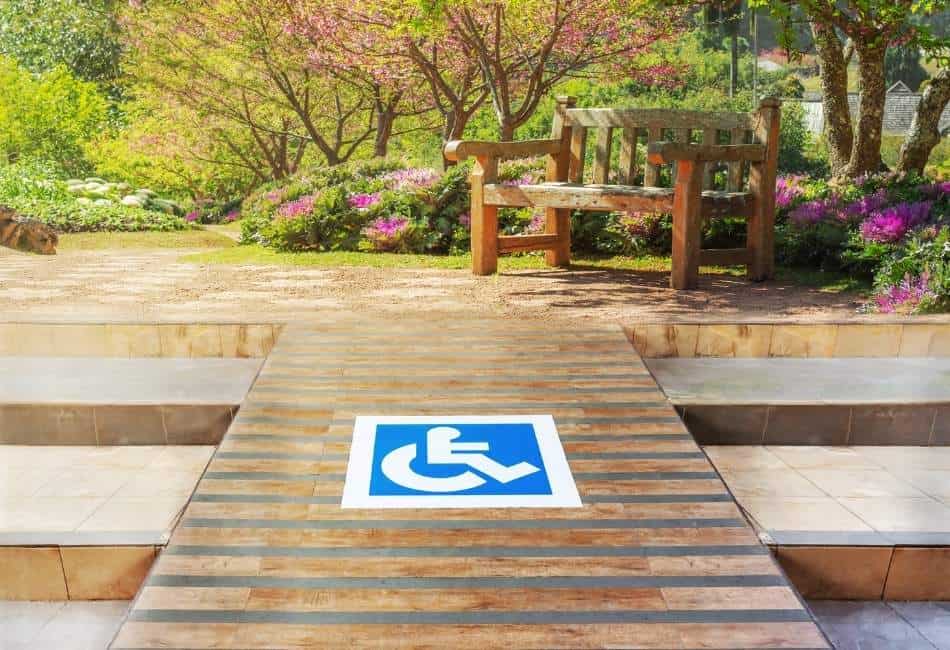

What is disability? There are multiple ways to look at it. The medical model views disabilities as wrongs to be fixed, disability means impairment. The social model goes further and looks at the wider picture: disability is seen as the interaction between people’s impairments and social barriers.

Let’s picture a person unable to use stairs. If we view disability through a strictly medical lens, we will focus on giving the person the ability to climb them through various medical and technological procedures. In contrast, the social model looks at the lack of alternatives to stairs, which is the real barrier. Advocates would focus their resources on building ramps, elevators and so on. The impairment is still there but is no longer disabling – the individual can function with autonomy and dignity.

There are many creative approaches to making society more accessible. And when we strive for an accessible society, we uncover many possibilities for climate change mitigation and adaptation. I will return to this point in a second, but I want to make clear why disability and climate change are related.

First, we live in a deeply inaccessible society, and despite some considerable progress in disability rights and challenging existing biases, there are still deep-rooted issues. Disabled and differently abled people are still frequently physically barred from places needed for personal development, political participation, and entertainment. From cinemas and townhalls to schools and workplaces, too many spaces are not designed for anything but a “normal” person. The inaccessibility of society in the context of a changing climate creates an existential risk for us.

Given the structural devaluation of disabled lives, the different material needs, the links to poverty and isolation and the frequent lack of government foresight, it’s easy to see why we are significantly more vulnerable to natural disasters and supply chain disruptions. Whenever a catastrophe happens, the victims will be disproportionately disabled people. They are ignored during warnings, left behind during evacuation attempts, and neglected during relief efforts.

There are countless examples of governments and humanitarian NGOs failing to accommodate the unique needs of blind, deaf, immobile, neurodivergent and otherwise disabled people. Whether we look at the lack of interpreters during Hurricane Katrina evacuation efforts or the treatment of disabled climate refugees, governments happily ignore the needs of disabled people – be they citizens or not.

The COVID pandemic gave many politicians and celebrities the chance to make official what disability activists have been saying for ages. They touted, loud and clear, that only the vulnerable are at risk of losing their lives. This narrative shows the complete disregard, or even contempt, for the safety of the vulnerable population, which includes the immunocompromised, the elderly and those with pre-existing conditions. While people with learning disabilities were being given blanket Do Not Resuscitate orders in the UK during the first wave of the pandemic, others were protesting to end the lockdown early to get haircuts or massages. Medically vulnerable and socially considered disposable, disabled people and their allies have no choice but to organize, self-advocate and fight back.

We must recognize the many forms of oppression which, through their origins, history, and interactions gave rise to (and maintain) the existing ecocidal, ableist, white supremacist, patriarchal, colonial system. If our climate activism is genuinely radical, if it wishes to transform society on the fundamental level and ensure a better future for all, then it must recognize the ways in which climate change, disability and other forms of opression interact. It must fight ecoableism and lift the voices of disabled leaders.

Ecoableism is when our approaches to environmental activism end up hurting disabled people. It is ‘a failure by non-disabled environmentalists to recognize that many of the climate actions they’re promoting make life difficult for disabled people’. There is a need for constructive dialogue rather than punishing those engaging in it.

A good example of ecoableism: bike lanes. Many car-free routes have barriers designed to stop motorbikes. The “ableist” part becomes clear when you consider that many disabled people would still want to use them, but must use nonconventional bikes, frequently harder to maneuver, such as recliners or wheelchair hand bikes. Moreover, city planners admit that a determined person can still maneuver through the barriers with a motorcycle, while for some modified bicycles, this is simply impossible.

Up and over – cycle barrier in Greenwich Park This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license. Attribution: Stephen Craven https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Up_and_over_-_cycle_barrier_in_Greenwich_Park_-_geograph.org.uk_-_951419.jpg

Glucose monitor applicator wrapping, author supplied.

I hope I made it clear that the needs of disabled people vary. Like all people, individual access needs to change from individual to individual. By restructuring both our societal values, our mindsets, and our economies to fight climate change, we have the unique chance to design novel support systems and supply chain structures able to cater to varied individual needs, including those of disabled people. This unique chance will build resilience within our communities by ensuring everyone’s needs are met, fostering social cohesiveness and increasing participation.

An inaccessible society strangles itself. It stops people with unique talents and skills from participating in the problem-solving and decision-making processes. An accessible one will have more diversity in its approaches, more perspectives to see the world from. Our means to achieve this must be different from forcing disabled people into poverty by cutting benefits when there is a worker shortage, as done with the American “incentive model.” We need to provide an environment where everyone can participate in activities which are both fulfilling and necessary for society, not force people into dead end jobs where their needs are not accounted for using poverty as a threat.

Moreover, accessibility is good for everyone. We will all benefit from a less judgmental, more empathetic society. While wheelchair users need ramps, they also benefit the elderly, injured people and people with strollers. Remote working benefits the disabled primarily, but by reducing commute requirements, it improves overall work-life balance and helps fight climate change by reducing the need for individual cars and putting less pressure on public transport systems.

Importantly, anyone can become disabled. The already ongoing climate emergency is increasing the frequency and intensity of natural disasters and increasing the risk of diseases. This means that building strong, flexible and resilient healthcare and support systems is a vital climate adaptation goal.

Life as a disabled person is not easy. But beyond the “inspiration porn” designed to make abled people feel better about their own suffering, there are important lessons to learn regarding both personal perseverance and community building. The green transition offers an unprecedented chance to both rebuild physical infrastructure and change social norms.

By joining the forces of the disability rights movement and environmental activism and using the hard learned lessons of both we can strive to dismantle existing systems of oppression and build a new society where accessibility, resilience, and sustainability are fundamental values, rather than afterthoughts.

https://ncd.gov/publications/2005/09022005 National Council on Disability on Hurricane Katrina Affected Areas II

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09687599.2019.1655856 Seeking a disability lens within climate change migration discourses, policies and practices

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-013-1011-1 Simulations of Hurricane Katrina (2005) under sea level and climate conditions for 1900

https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/news/disability-environmental-movement-exclusion/?%24Version=0 For disabled environmentalists, discrimination and exclusion are a daily reality

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/13/new-do-not-resuscitate-orders-imposed-on-covid-19-patients-with-learning-difficulties Guardian: Fury at ‘do not resuscitate’ notices given to Covid patients with learning disabilities

https://www.ncd.gov/publications/2006/Aug072006 The Impact of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita on People with Disabilities: A Look Back and Remaining Challenges

https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2005/oct/5/20051005-095340-4787r/ katrina on deaf people

https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000413842300001?SID=D3PWMUgbz6A5Rf9LjdQ Factors Associated with the Climate Change Vulnerability and the Adaptive Capacity of People with Disability: A Systematic Review

Teaser photo credit: New Orleans : Wheelchair with flood damaged possessions on curb as trash. Own work Infrogmation . Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License , Version 1.2 or any later version https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HollygroveJan1106Wheelchaircurb.jpg

Andrei Mihail

Related articles.

Earth Isn’t Just Where We’re From

By Richard Heinberg , Resilience.org

Earth is it. It’s not just where we’re from, it’s where we belong, and it’s the only home we will ever know. If we don’t take care of it, we will cease to exist.

April 22, 2024

Energy Descent: Public Letter

By Isaiah Ritzmann , Resilience.org

There will be less energy to go around – but there will be more equality and more meaningful ways of living. This future may have less energy – but it will have more of what really matters.

April 19, 2024

Taking Paradigm Shift To A Wider Audience, Part One

By Jan Spencer , Resilience.org

This article is part of the Primer For Paradigm Shift Series and will describe taking the ideals and actions of paradigm shift to a wider audience. We have many allies and assets to work with for sharing what paradigm shift has to offer the wider world.

- Inclusive Skill Development: India and Differently-abled Livelihood

- On: January 17, 2023

- By: Smile Foundation

“Development can only be sustainable when it is equitable, inclusive and accessible for all. Persons with disabilities need therefore to be included at all stages of development processes, from inception to monitoring and evaluation.” Ban Ki Moon

The Context

People who are differently abled perceive the world quite differently from those without them. Their experiences, joys, difficulties, and more might find similar patterns with others but it would be true to say here that their journey toward independent living is filled with difficulties unimaginable for most of us. What can we do in such a case? Enrollments in online skill development courses are one way to go about it.

We can support them while they build their own bridges to get where they want to be. Sometimes, being a fully supporting character in someone’s life is more than enough.

What does Disability mean in India?

The Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act was approved by the Indian government in 1995. According to the Act, a person who qualifies as “disabled” has at least a 40% handicap, as determined by a medical authority. Such a person is also called PwD, a Person with Disability.

Additionally, there are various frameworks that are now utilised in India to describe and define disability. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was ratified by the Indian government.

In October 2007, (UNCRPD), according to Article 1 of the Convention, “Persons with disabilities include individuals who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments that, when combined with other factors, may prevent them from fully and effectively participating in society on an equal basis with others.”

As a result, disability is not viewed as a distinct medical illness but rather as the result of interactions between a person’s health and their environment in general.

In India, there were over 22 million people with disabilities, which is about 2.13 percent of the population, according to the Census of 2012. This encompasses those who have physical, mental, or communicative difficulties. Nevertheless, the 2009 World Bank Report estimates that there are about 6% of disabled people in India. To top it off, the World Health Organization estimates that 10% of the population is affected.

Disability is a complicated phenomenon, making it difficult to precisely estimate its prevalence through a national survey. Given these difficulties, it is not unexpected that there is disagreement over the best ways to quantify handicaps, leading to a range of numbers.

Value Proposition of Including People with Disabilities in the Workforce

Despite having a sizable population, PwDs are rarely regarded as the nation-state’s productive human resource. National states sometimes disregard the relationship between disability and poverty, which creates a vicious cycle in which people with disabilities and their families are more likely to be poor than the general population because they have fewer opportunities to earn money and higher expenditures.

The talent, hard work, and potential of PwDs in India are mostly unrealized, underutilized, or underdeveloped. Additionally, the employment and education rates for people with disabilities are significantly lower than those of other people.

PwDs are one of the poorest populations in India since there are fewer options for them to make money and more expenditures to cover. Even though work prospects have risen over the past 20 years and India’s GDP grows by an average of 6.3% percent , the employment rate for people with disabilities actually decreased.

Many not-for-profit organisations working in tandem with the rising needs of the Government of India and the nation, have been trying to skill the Indian youth from underprivileged sections to prepare them better for employment opportunities, and online skill development courses are high on their agenda.

Suggestions for the Private Sector

So how can the private sector rise up and make their workplace more diverse and representative of different communities?

According to the PwD Act 1995, the Government of India will provide incentives to the public and commercial sectors to encourage the hiring of people with disabilities. However despite the incentive program’s passage, 13 the outcomes need major improvements.

To evaluate current incentive programmes and develop new ones that will encourage the hiring of handicapped people in the commercial sector, the private sector’s engagement, in especially the business world, requires considerably more creativity and should ideally go beyond simple incentives like tax breaks and Provident Fund payments, etc.

Creating accessibility in the workplace, and providing assistive technology, gadgets, personal attendants, etc. are just a few examples of improvements and concessions that might be made to the workplace to support and promote employment for PwDs.

It’s a great idea to hold private meetings with corporations and business groups, together with an executive decision-maker, to discuss how they might help PwDs have a better quality of life. Create a composite livelihood plan as a pilot project, and appoint an impartial committee to oversee it. The committee should have suitable representation from PwDs, business entities, the government, and civil society.

Some Points for Urban Livelihoods, Self Employment and Entrepreneurship

A good starting point would be to Include the interests and needs of the differently-abled as a vulnerable group in new or current poverty reduction programmes to provide chances for livelihood (wage and self-employment) for those living in urban areas, particularly slums and from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

Also, create incentive programmes (such as exemptions from sales tax, VAT, excise tax, and service tax) for disabled business owners, companies that employ more than 50% of disabled people, and companies that produce assistive technology or gadgets for people with disabilities.

Points for Rural Livelihoods

Under major government initiatives, like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) which already includes provisions for PwDs, disability-specific sub-programmes might be launched. Disability audits should be conducted on a regular basis to make sure the programme is effective for the handicapped community. These will highlight the creases and assist in determining the best tactics for ironing them out.

Additionally, campaigns may be launched to raise awareness of the rights granted to the disabled under the programme.

In order to guarantee that the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) is inclusive with a provision for reasonable accommodations/adjustments, there should also be an extra focus on vulnerable groups like women with disabilities, etc., ensuring that 3% of the target population benefits from the scheme, and have regular reviews undertaken to determine the impact of the programme on the livelihood patterns of PwDs.