- Open access

- Published: 14 September 2023

Children and youth’s perceptions of mental health—a scoping review of qualitative studies

- Linda Beckman 1 , 2 ,

- Sven Hassler 1 &

- Lisa Hellström 3

BMC Psychiatry volume 23 , Article number: 669 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

6140 Accesses

2 Citations

Metrics details

Recent research indicates that understanding how children and youth perceive mental health, how it is manifests, and where the line between mental health issues and everyday challenges should be drawn, is complex and varied. Consequently, it is important to investigate how children and youth perceive and communicate about mental health. With this in mind, our goal is to synthesize the literature on how children and youth (ages 10—25) perceive and conceptualize mental health.

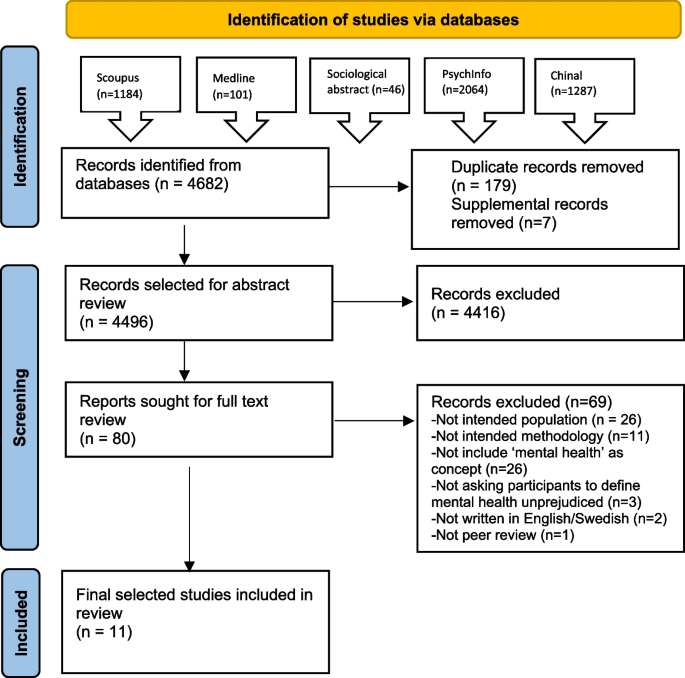

We conducted a preliminary search to identify the keywords, employing a search strategy across electronic databases including Medline, Scopus, CINAHL, PsychInfo, Sociological abstracts and Google Scholar. The search encompassed the period from September 20, 2021, to September 30, 2021. This effort yielded 11 eligible studies. Our scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR Checklist.

As various aspects of uncertainty in understanding of mental health have emerged, the results indicate the importance of establishing a shared language concerning mental health. This is essential for clarifying the distinctions between everyday challenges and issues that require treatment.

We require a language that can direct children, parents, school personnel and professionals toward appropriate support and aid in formulating health interventions. Additionally, it holds significance to promote an understanding of the positive aspects of mental health. This emphasis should extend to the competence development of school personnel, enabling them to integrate insights about mental well-being into routine interactions with young individuals. This approach could empower children and youth to acquire the understanding that mental health is not a static condition but rather something that can be enhanced or, at the very least, maintained.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

In Western society, the prevalence of mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety [ 1 ], as well as recurring psychosomatic health complaints [ 2 ], has increased from the 1980s and 2000s. However, whether these changes in adolescent mental health are actual trends or influenced by alterations in how adolescents perceive, talk about, and report their mental well-being remains ambiguous [ 1 ]. Despite an increase in self-reported mental health problems, levels of mental well-being have remained stable, and severe psychiatric diagnoses have not significantly risen [ 3 , 4 ]. Recent research indicates that understanding how children and youth grasp mental health, its manifestations, and the demarcation between mental health issues and everyday challenges is intricate and diverse. Wickström and Kvist Lindholm [ 5 ] show that problems such as feeling low and nervous are considered deep-seated issues among some adolescents, while others refer to them as everyday challenges. Meanwhile, adolescents in Hellström and Beckman [ 6 ] describe mental health problems as something mainstream, experienced by everyone at some point. Furthermore, Hermann et al. [ 7 ] point out that adolescents can distinguish between positive health and mental health problems. This indicates their understanding of the complexity and holistic nature of mental health and mental health issues. It is plausible that misunderstandings and devaluations of mental health and illness concepts may increase self-reported mental health problems and provide contradictory results when the understanding of mental health is studied. In a previous review on how children and young people perceive the concept of “health,” four major themes have been suggested: health practices, not being sick, feeling good, and being able to do the desired and required activities [ 8 ]. In a study involving 8–11 year olds, children framed both biomedical and holistic perspectives of health [ 9 ]. Regarding the concept of “illness,” themes such as somatic feeling states, functional and affective states [ 10 , 11 ], as well as processes of contagion and contamination, have emerged [ 9 ]. Older age strongly predicts nuances in conceptualizations of health and illness [ 10 , 11 , 12 ].

As the current definitions of mental health and mental illness do not seem to have been successful in guiding how these concepts are perceived, literature has emphasized the importance of understanding individuals’ ideas of health and illness [ 9 , 13 ]. The World Health Organization (WHO) broadly defines mental health as a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively and fruitfully and make a contribution to his or her community [ 14 ] capturing only positive aspects. According to The American Psychology Association [ 15 ], mental illness includes several conditions with varying severity and duration, from milder and transient disorders to long-term conditions affecting daily function. The term can thus cover everything from mild anxiety or depression to severe psychiatric conditions that should be treated by healthcare professionals. As a guide for individual experience, such a definition becomes insufficient in distinguishing mental illness from ordinary emotional expressions. According to the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare et al. [ 16 ], mental health works as an umbrella term for both mental well-being and mental illness : Mental well-being is about being able to handle life's difficulties, feeling satisfied with life, having good social relationships, as well as being able to feel pleasure, desire, and happiness. Mental illness includes both mild to moderate mental health problems and psychiatric conditions . Mild to moderate mental health problems are common and are often reactions to events or situations in life, e.g., worry, feeling low, and sleep difficulties.

It has been argued that increased knowledge of the nature of mental illness can help individuals to cope with the situation and improve their well-being. Increased knowledge about mental illness, how to prevent mental illness and help-seeking behavior has been conceptualized as “mental health literacy” (MHL) [ 17 ], a construct that has emerged from “health literacy” [ 18 ]. Previous literature supports the idea that positive MHL is associated with mental well-being among adolescents [ 19 ]. Conversely, studies point out that low levels of MHL are associated with depression [ 20 ]. Some gender differences have been acknowledged in adolescents, with boys scoring lower than girls on MHL measures [ 20 ] and a social gradient including a positive relationship between MHL and perceived good financial position [ 19 ] or a higher socio-economic status [ 21 ].

While MHL stresses knowledge about signs and treatment of mental illness [ 22 ], the concern from a social constructivist approach would be the conceptualization of mental illness and how it is shaped by society and the thoughts, feelings, and actions of its members [ 23 ]. Studies on the social construction of anxiety and depression through media discourses have shown that language is at the heart of these processes, and that language both constructs the world as people perceive it but also forms the conditions under which an experience is likely to be construed [ 24 , 25 ]. Considering experience as linguistically inflected, the constructionist approach offers an analytical tool to understand the conceptualization of mental illness and to distinguish mental illness from everyday challenges. The essence of mental health is therefore suggested to be psychological constructions identified through how adolescents and society at large perceive, talk about, and report mental health and how that, in turn, feeds a continuous process of conceptual re-construction or adaptation [ 26 ]. Considering experience as linguistically inflected, the constructionist approach could then offer an analytical tool to understand the potential influence of everyday challenges in the conceptualization of mental health.

Research investigating how children and youth perceive and communicate mental health is essential to understand the current rise of reported mental health problems [ 5 ]. Health promotion initiatives are more likely to be successful if they take people’s understanding, beliefs, and concerns into account [ 27 , 28 ]. As far as we know, no review has mapped the literature to explore children’s and youths’ perceptions of mental health and mental illness. Based on previous literature, age, gender, and socioeconomic status seem to influence children's and youths’ knowledge and experiences of mental health [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]; therefore, we aim to analyze these perspectives too. From a social constructivist perspective, experience is linguistically inflected [ 26 ]; hence illuminating the conditions under which a perception of health is formed is of interest.

Therefore, we aim to study the literature on how children and youth (ages 10—25) perceive and conceptualize mental health, and the specific research questions are:

What aspects are most salient in children’s and youths’ perceptions of mental health?

What concepts do children and youth associate with mental health?

In what way are children's and youth’s perceptions of mental health dependent on gender, age, and socioeconomic factors?

Literature search

A scoping review is a review that aims to provide a snapshot of the research that is published within a specific subject area. The purpose is to offer an overview and, on a more comprehensive level, to distinguish central themes compared to a systematic review. We chose to conduct a scoping review since our aim was to clarify the key concepts of mental health in the literature and to identify specific characteristics and concepts surrounding mental health [ 29 , 30 ]. Our scoping review was conducted following the PRISMA-ScR Checklist [ 31 ]. Two authors (L.B and L.H) searched and screened the eligible articles. In the first step, titles and abstracts were screened. If the study included relevant data, the full article was read to determine if it met the eligibility criteria. Articles were excluded if they did not fulfill all the eligibility criteria. Any uncertainties were discussed among L.B. and L.H., and the third author, S.H., and were carefully assessed before making an inclusion or exclusion decision. The software Picoportal was employed for data management. Figure 1 illustrates a flowchart of data inclusion.

PRISMA flow diagram outlining the search process

Eligibility criteria

We incorporated studies involving children and youth aged 10 to 25 years. This age range was chosen to encompass early puberty through young adulthood, a significant developmental period for young individuals in terms of comprehending mental health. Participants were required not to have undergone interviews due to chronic illness, learning disabilities (e.g., mental health linked to a cancer diagnosis), or immigrant status.

Studies conducted in clinical settings were excluded. For the purpose of comparing results under similar conditions, we specifically opted for studies carried out in Western countries .

Given that this review adopts a moderately constructionist approach, intentionally allowing for the exploration of how both young participants and society in general perceive and discuss mental health and how this process contributes to ongoing conceptual re-construction, the emphasis was placed on identifying articles in which participants themselves defined or attributed meaning to mental health and related concepts like mental illness. The criterion of selecting studies adopting an inductive approach to capture the perspectives of the young participants resulted in the exclusion of numerous studies that more overtly applied established concepts to young respondents [ 32 ].

Information sources

We utilized electronic databases and reached out to study authors if the article was not accessible online. Peer-reviewed articles were exclusively included, thereby excluding conference abstracts due to their perceived lack of relevance in addressing the review questions. Only research in English was taken into account. Publication years across all periods were encompassed in the search.

Search strategy

Studies concerning children’s and youths’ perceptions of mental health were published across a range of scientific journals, such as those within psychiatry, psychology, social work, education, and mental health. Therefore, several databases were taken into account, including Medline, Scopus, CINAHL, PsychInfo, Sociological abstracts, and Google Scholar, spanning from inception on September 20, 2021 to September 30, 2021. We involved a university librarian from the start in the search process. The combinations of search terms are displayed in Table 1 .

Quality assessment

We employed the Quality methods for the development of National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE) public health guidance [ 33 ] to evaluate the quality of the studies included. The checklist is based on checklists from Spencer et al. [ 34 ], Public Health Resource Unit (PHRU) [ 26 , 35 ], and the North Thames Research Appraisal Group (NTRAG) [ 36 ] (Refer to S2 for checklist). Eight studies were assigned two plusses, and three studies received one plus. The studies with lower grades generally lacked sufficient descriptions of the researcher’s role, context reporting, and ethical reporting. No study was excluded in this stage.

Data extraction and analysis

We employed a data extraction form that encompassed several key characteristics, including author(s), year, journal, country, details about method/design, participants and socioeconomics, aim, and main results (Table 2 ). The collected data were analyzed and synthesized using the thematic synthesis approach of Thomas and Harden [ 37 ]. This approach encompassed all text categorized as 'results' or 'findings' in study reports – which sometimes included abstracts, although the presentation wasn’t always consistent throughout the text. The size of the study reports ranged from a few sentences to a single page. The synthesis occurred through three interrelated stages that partially overlapped: coding of the findings from primary studies on a line-by-line basis, organization of these 'free codes' into interconnected areas to construct 'descriptive' themes, and the formation of 'analytical' themes.

The objective of this scoping review has been to investigate the literature concerning how children and youth (ages 10—25) conceptualize and perceive mental health. Based on the established inclusion- and exclusion criteria, a total of 11 articles were included representing the United Kingdom ( n = 6), Australia ( n = 3), and Sweden ( n = 2) and were published between 2002 and 2020. Among these, two studies involved university students, while nine incorporated students from compulsory schools.

Salient aspects of children and youth’ perceptions of mental health

Based on the results of the included articles, salient aspects of children’s and youths’ understandings revealed uncertainties about mental health in various ways. This uncertainty emerged as conflicting perceptions, uncertainty about the concept of mental health, and uncertainty regarding where to distinguish between mild to moderate mental health problems and everyday stressors or challenges.

One uncertainty was associated with conflicting perceptions that mental health might be interpreted differently among children and youths, depending on whether it relates to their own mental health or someone else's mental health status. Chisholm et al. [ 42 ] presented this as distinctions being made between ‘them and us’ and between ‘being born with it’. Mental health and mental illness were perceived as a continuum that rather developed’, and distinctions were drawn between ‘crazy’ and ‘diagnosed.’ Participants established strong associations between the term mental illness and derogatory terms like ‘crazy,’ linking extreme symptoms of mental illness with others. However, their attitude was less stigmatizing when it came to individual diagnoses, reflecting a more insightful and empathetic understanding of the adverse impacts of stress based on their personal realities and experiences. Despite the initial reactions reflecting negative stereotypes, further discussion revealed that this did not accurately represent a deeper comprehension of mental health and mental illness.

There was also uncertainty about the concept of mental health , as it was not always clearly understood among the participating youth. Some participants were unable to define mental health, often confusing it with mental illness [ 28 ]. Others simply stated that they did not understand the term, as in O’Reilly [ 44 ]. Additionally, uncertainty was expressed regarding whether mental health was a positive or negative concept [ 27 , 28 , 40 , 44 ], and participants associated mental health with mental illness despite being asked about mental health [ 28 ]. One quote from a grade 9 student illustrates this: “ Interviewer: Can mental health be positive as well? Informant: No, it’s mental” [ 44 ]. In Laidlaw et al. [ 46 ], with participants ranging from 18—22 years of age, most considered mental health distinctly different from and more clinical than mental well-being. However, Roose et al. [ 38 ], for example, the authors discovered a more multifaceted understanding of mental health, encompassing emotions, thoughts, and behavior. In Molenaar et al.[ 45 ], mental health was highlighted as a crucial aspect of health overall. In Chisholm et al. [ 42 ], the older age groups discussed mental health in a more positive sense when they considered themselves or people they knew, relating mental health to emotional well-being. Connected to the uncertainty in defining the concept of mental health was the uncertainty in identifying those with good or poor mental health. Due to the lack of visible proof, children and youths might doubt their peers’ reports of mental illness, wondering if they were pretending or exaggerating their symptoms [ 27 ].

A final uncertainty that emerged was difficulties in drawing the line between psychiatric conditions and mild to moderate mental health problems and everyday stressors or challenges . Perre et al. [ 43 ] described how the participants in their study were uncertain about the meaning of mental illness and mental health issues. While some linked depression to psychosis, others related it to simply ‘feeling down.’ However, most participants indicated that, in contrast to transient feelings of sadness, depression is a recurring concern. Furthermore, the duration of feeling depressed and particularly a loss of interest in socializing was seen as appropriate criteria for distinguishing between ‘feeling down’ and ‘clinical depression.’ Since feelings of anxiety, nervousness, and apprehension are common experiences among children and youth, defining anxiety as an illness as opposed to an everyday stressor was more challenging [ 43 ].

Terms used to conceptualize mental health

When children and youth were asked about mental health, they sometimes used neutral terms such as thoughts and emotions or a general ‘vibe’ [ 27 ], and some described it as ‘peace of mind’ and being able to balance your emotions [ 38 ]. The notion of mental health was also found to be closely linked with rationality and the idea of normality, although, according to the young people, Armstrong et al. [ 28 ], there was no consensus about what ‘normal’ meant. Positive aspects of mental health were described by the participants as good self-esteem, confidence [ 40 ], happiness [ 39 , 43 ], optimism, resilience, extraversion and intelligence [ 27 ], energy [ 43 ], balance, harmony [ 39 , 43 ], good brain, emotional and physical functioning and development, and a clear idea of who they are [ 27 , 41 ]. It also included a feeling of being a good person, feeling liked and loved by your parents, social support, and having people to talk with [ 27 , 39 ], as well as being able to fit in with the world socially and positive peer relationships [ 41 ], according to the children and youths, mental health includes aspects related to individuals (individual factors) as well as to people in their surroundings (relationships). Regarding mental illness, participants defined it as stress and humiliation [ 40 ], psychological distress, traumatic experiences, mental disorders, pessimism, and learning disabilities [ 27 ]. Also, in contrast to the normality concept describing mental health, mental illness was described as somehow ‘not normal’ or ‘different’ in Chisholm et al. [ 42 ].

Depression and bipolar disorder were the most often mentioned mental illnesses [ 27 ]. The inability to balance emotions was seen as negative for mental health, for example, not being able to set aside unhappiness, lying to cover up sadness, and being unable to concentrate on schoolwork [ 38 ]. The understanding of mental illness also included feelings of fear and anxiety [ 42 ]. Other participants [ 46 ] indicated that mental health is distinctly different from, and more clinical than, mental well-being. In that sense, mental health was described using reinforcing terms such as ‘serious’ and ‘clinical,’ being more closely connected to mental illness, whereas mental well-being was described as the absence of illness, feeling happy, confident, being able to function and cope with life’s demands and feeling secure. Among younger participants, a more varied and vague understanding of mental health was shown, framing it as things happening in the brain or in terms of specific conditions like schizophrenia [ 44 ].

Gender, age, socioeconomic status

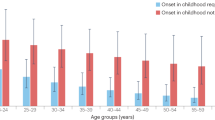

Only one study had a gender theoretical perspective [ 40 ], but the focus of this perspective concerned gender differences in what influences mental health more than the conceptualization of mental health. According to Johansson et al.[ 39 ], older girls expressed deeper negative emotions (e.g., described feelings of lack of meaning and hope in various ways) than older boys and younger children.

Several of the included studies noticed differences in age, where younger participants had difficulty understanding the concept of mental health [ 39 , 44 ], while older participants used more words to explain it [ 39 ]. Furthermore, older participants seemed to view mental health and mental illness as a continuum, with mental illness at one end of the continuum and mental well-being at the other end [ 42 , 46 ].

Socioeconomic status

The role of socioeconomic status was only discussed by Armstrong et al. [ 28 ], finding that young people from schools in the most deprived and rural areas experienced more difficulties defining the term mental health compared to those from a less deprived area.

This scoping review aimed to map children's and youth’s perceptions and conceptualizations of mental health. Our main findings indicate that the concept of mental health is surrounded by uncertainty. This raises the question of where this uncertainty stems from and what it symbolizes. From our perspective, this uncertainty can be understood from two angles. Firstly, the young participants in the different studies show no clear and common understanding of mental health; they express uncertainty about the meaning of the concept and where to draw the line between life experiences and psychiatric conditions. Secondly, uncertainty exists regarding how to apply these concepts in research, making it challenging to interpret and compare research results. The shift from a positivistic understanding of mental health as an objective condition to a more subjective inner experience has left the conceptualization open ranging from a pathological phenomenon to a normal and common human experience [ 47 ]. A dilemma that results in a lack of reliability that mirrors the elusive nature of the concept of mental health from both a respondent and a scientific perspective.

“Happy” was commonly used to describe mental health, whereas "unhappy" was used to describe mental illness. The meaning of happiness for mental health has been acknowledged in the literature, and according to Layard et al. [ 48 ], mental illness is one of the main causes of unhappiness, and happiness is the ultimate goal in human life. Layard et al. [ 48 ] suggest that schools and workplaces need to raise more awareness of mental health and strive to improve happiness to promote mental health and prevent mental illness. On the other hand, being able to experience and express different emotions could also be considered a part of mental health. The notion of normality also surfaced in some studies [ 38 ], understanding mental health as being emotionally balanced or normal or that mental illness was not normal [ 42 ]. To consider mental illness in terms of social norms and behavior followed with the sociological alternative to the medical model that was introduced in the sixties portraying mental illness more as socially unacceptable behavior that is successfully labeled by others as being deviant. Although our results did not indicate any perceptions of what ‘normal’ meant [ 28 ], one crucial starting point to the understanding of mental health among adolescents should be to delineate what constitutes normal functioning [ 23 ]. Children and youths’ understanding of mental illness seems to a large extent, to be on the same continuum as a normality rather than representing a medicalization of deviant behavior and a disjuncture with normality [ 49 ].

Concerning gender, it seemed that girls had an easier time conceptualizing mental health than boys. This could be due to the fact that girls mature verbally faster than boys [ 50 ], but also that girls, to a larger extent, share feelings and problems together compared to boys [ 51 ]. However, according to Johansson et al. [ 39 ], the differences in conceptualizations of mental health seem to be more age-related than gender-related. This could be due to the fact that older children have a more complex view of mental health compared to younger children.. Not surprisingly, the older the children and youth were, the more complex the ability to conceptualize mental health becomes. Only one study reported socioeconomic differences in conceptualizations of mental health [ 28 ]. This could be linked to mental health literacy (MHL) [ 18 ], i.e., knowledge about mental illness, how to prevent mental illness, and help-seeking behavior. Research has shown that disadvantaged social and socioeconomic conditions are associated with low MHL, that is, people with low SES tends to know less about symptoms and prevalence of different mental health problems [ 19 , 21 ]. The perception and conceptualizations of mental health are, as we consider, strongly related to knowledge and beliefs about mental health, and according to von dem Knesebeck et al. [ 52 ] linked primarily to SES through level of education.

Chisholm et al. [ 42 ] found that the initial reactions from participants related to negative stereotypes, but further discussion revealed that the participants had more refined knowledge than at first glance. This illuminates the importance of talking to children and helping them verbalize their feelings, in many respects complex and diversified understanding of mental health. It is plausible that misunderstandings and devaluations of mental health and mental illness may increase self-reported mental health problems [ 5 ], as well as decrease them, preventing children and youth from seeking help. Therefore, increased knowledge of the nature of mental health can help individual cope with the situations and improve their mental well-being. Finding ways to incorporate discussions about mental well-being, mental health, and mental illness in schools could be the first step to decreasing the existing uncertainties about mental health. Experiencing feelings of sadness, anger, or upset from time to time is a natural part of life, and these emotions are not harmful and do not necessarily indicate mental illness [ 5 , 6 ]. Adolescents may have an understanding of the complexity of mental health despite using simplified language but may need guidance on how to communicate their feelings and how to manage everyday challenges and normal strains in life [ 7 ].

With the aim of gaining a better understanding of how mental health is perceived among children and youth, this study has highlighted the concept’s uncertainty. Children and youth reveal a variety of understandings, from diagnoses of serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia to moods and different types of behaviors. Is there only one way of understanding mental health, and is it reasonable to believe that we can reach a consensus? Judging by the questions asked, researchers also seem to have different ideas on what to incorporate into the concept of mental health — the researchers behind the present study included. The difficulties in differentiating challenges being part of everyday life with mental health issues need to be paid closer attention to and seems to be symptomatic with the lack of clarity of the concepts.

A constructivist approach would argue that the language of mental health has changed over time and thus influence how adolescents, as well as society at large, perceive, talk about, and report their mental health [ 26 ]. The re-construction or adaptation of concepts could explain why children and youth re struggling with the meaning of mental health and that mental health often is used interchangeably with mental illness. Mental health, rather than being an umbrella term, then represents a continuum with a positive and a negative end, at least among older adolescents. But as mental health according to this review also incorporates subjective expressions of moods and feelings, the reconstruction seems to have shaped it into a multidimensional concept, representing a horizontal continuum of positive and negative mental health and a vertical continuum of positive and negative well-being, similar to the health cross by Tudor [ 53 ] referred to in Laidlaw et al. [ 46 ] A multidimensional understanding of mental health constructs also incorporates evidence from interventions aimed at reducing mental health stigma among adolescents, where attitudes and beliefs as well as emotional responses towards mental health are targeted [ 54 ].

The contextual understanding of mental health, whether it is perceived in positive terms or negative, started with doctors and psychiatrists viewing it as representing a deviation from the normal. A perspective that has long been challenged by health workers, academics and professionals wanting to communicate mental health as a positive concept, as a resource to be promoted and supported. In order to find a common ground for communicating all aspects and dimensions of mental health and its conceptual constituents, it is suggested that we first must understand the subjective meaning ascribed to the use of the term [ 26 ]. This line of thought follows a social-constructionist approach viewing mental health as a concept that has transitioned from representing objective mental descriptions of conditions to personal subjective experiences. Shifting from being conceptualized as a pathological phenomenon to a normal and common human experience [ 47 ]. That a common understanding of mental health can be challenged by the healthcare services tradition and regulation for using diagnosis has been shown in a study of adolescents’ perspectives on shared decision-making in mental healthcare [ 55 ]. A practice perceived as labeling by the adolescents, indicating that steps towards a common understanding of mental health needs to be taken from several directions [ 55 ]. In a constructionist investigation to distinguish everyday challenges from mental health problems, instead of asking the question, “What is mental health?” we should perhaps ask, “How is the word ‘mental health’ used, and in what context and type of mental health episode?” [ 26 ]. This is an area for future studies to explore.

Methodological considerations

The first limitation we want to acknowledge, as for any scoping review, is that the results are limited by the search terms included in the database searches. However, by conducting the searches with the help of an experienced librarian we have taken precautions to make the searches as inclusive as possible. The second limitation concerns the lack of homogeneous, or any results at all, according to different age groups, gender, socioeconomic status, and year when the study was conducted. It is well understood that age is a significant determinant in an individual’s conceptualization of more abstract phenomena such as mental health. Some of the studies approached only one age group but most included a wide age range, making it difficult to say anything specific about a particular age. Similar concerns are valid for gender. Regarding socioeconomic status, only one study reported this as a finding. However, this could be an outcome of the choice of methods we had — i.e., qualitative methods, where the aim seldom is to investigate differences between groups and the sample is often supposed to be a variety. It could also depend on the relatively small number of participants that are often used in focus groups of individual interviews- there are not enough participants to compare groups based on gender or socioeconomic status. Finally, we chose studies from countries that could be viewed as having similar development and perspective on mental health among adolescents. Despite this, cultural differences likely account for many youths’ conceptualizations of mental health. According to Meldahl et al. [ 56 ], adolescents’ perspectives on mental health are affected by a range of factors related to cultural identity, such as ethnicity, race, peer and family influence, religious and political views, for example. We would also like to add organizational cultures, such as the culture of the school and how schools work with mental health and related concepts [ 56 ].

Conclusions and implications

Based on our results, we argue that there is a need to establish a common language for discussing mental health. This common language would enable better communication between adults and children and youth, ensuring that the content of the words used to describe mental health is unambiguous and clear. In this endeavor, it is essential to actively listen to the voices of children and youth, as their perspectives will provide us with clearer understanding of the experiences of being young in today’s world. Another way to develop a common language around mental health is through mental health education. A common language based on children’s and youth’s perspectives can guide school personnel, professionals, and parents when discussing and planning health interventions and mental health education. Achieving a common understanding through mental health education of adults and youth could also help clarify the boundaries between everyday challenges and problems needing treatment. It is further important to raise awareness of the positive aspect of mental health—that is, knowledge of what makes us flourish mentally should be more clearly emphasized in teaching our children and youth about life. It should also be emphasized in competence development for school personnel so that we can incorporate knowledge about mental well-being in everyday meetings with children and youth. In that way, we could help children and youth develop knowledge that mental health could be improved or at least maintained and not a static condition.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Twenge JM, Joiner TE, Rogers ML, Martin GN. Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clin Psychol Sci. 2018;6(1):3–17.

Article Google Scholar

Potrebny T, Wiium N, Lundegård MM-I. Temporal trends in adolescents’ self-reported psychosomatic health complaints from 1980–2016: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS one. 2017;12(11):e0188374. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188374 . [published Online First: Epub Date]|.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Petersen S, Bergström E, Cederblad M, et al. Barns och ungdomars psykiska hälsa i Sverige. En systematisk litteraturöversikt med tonvikt på förändringar över tid. (The mental health of children and young people in Sweden. A systematic literature review with an emphasis on changes over time). Stockholm: Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien; 2010.

Google Scholar

Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Ferrari AJ, Norman RE, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Challenging the myth of an “epidemic” of common mental disorders: trends in the global prevalence of anxiety and depression between 1990 and 2010. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(6):506–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22230 . [published Online First: Epub Date]|.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Wickström A, Kvist LS. Young people’s perspectives on the symptoms asked for in the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children survey. Childhood. 2020;27(4):450–67.

Hellström L, Beckman L. Life Challenges and Barriers to Help Seeking: Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Voices of Mental Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(24):13101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413101 . [published Online First: Epub Date]|.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hermann V, Durbeej N, Karlsson AC, Sarkadi A. ‘Feeling down one evening doesn’t count as having mental health problems’—Swedish adolescents’ conceptual views of mental health. J Adv Nurs. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15496 . [published Online First: Epub Date]|.

Boruchovitch E, Mednick BR. The meaning of health and illness: some considerations for health psychology. Psico-USF. 2002;7:175–83.

Piko BF, Bak J. Children’s perceptions of health and illness: images and lay concepts in preadolescence. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(5):643–53.

Millstein SG, Irwin CE. Concepts of health and illness: different constructs or variations on a theme? Health Psychol. 1987;6(6):515.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Campbell JD. Illness is a point of view: the development of children's concepts of illness. Child Dev. 1975;46(1):92–100.

Mouratidi P-S, Bonoti F, Leondari A. Children’s perceptions of illness and health: An analysis of drawings. Health Educ J. 2016;75(4):434–47.

Julia L. Lay experiences of health and illness: past research and future agendas. Sociol Health Illn. 2003;25(3):23–40.

World Health Organization. Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice (Summary Report). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42940 .

American Psychiatric Association. What is mental illness?. Secondary What is mental illness? 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-mentalillness .

National board of health and welfare TSAoLAaRatSAfHTA, Assessment of Social Services. What is mental health and mental illness? Secondary What is mental health and mental illness? 2022. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/kunskapsstod-och-regler/omraden/psykisk-ohalsa/vad-menas-med-psykisk-halsa-och-ohalsa/ .

Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Pollitt P. “Mental health literacy”: a survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust. 1997;166(4):182–6.

Kutcher S, Wei Y, Coniglio C. Mental health literacy: Past, present, and future. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(3):154–8.

Bjørnsen HN, Espnes GA, Eilertsen M-EB, Ringdal R, Moksnes UK. The relationship between positive mental health literacy and mental well-being among adolescents: implications for school health services. J Sch Nurs. 2019;35(2):107–16.

Lam LT. Mental health literacy and mental health status in adolescents: a population-based survey. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2014;8:1–8.

Campos L, Dias P, Duarte A, Veiga E, Dias CC, Palha F. Is it possible to “find space for mental health” in young people? Effectiveness of a school-based mental health literacy promotion program. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):1426.

Mårtensson L, Hensing G. Health literacy–a heterogeneous phenomenon: a literature review. Scand J Caring Sci. 2012;26(1):151–60.

Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, Bierman A. The sociology of mental health: Surveying the field. Handbook of the sociology of mental health: Springer; 2013. p. 1–19.

Book Google Scholar

Johansson EE, Bengs C, Danielsson U, Lehti A, Hammarström A. Gaps between patients, media, and academic medicine in discourses on gender and depression: a metasynthesis. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(5):633–44.

Dowbiggin IR. High anxieties: The social construction of anxiety disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(7):429–36.

Stein JY, Tuval-Mashiach R. The social construction of loneliness: an integrative conceptualization. J Constr Psychol. 2015;28(3):210–27.

Teng E, Crabb S, Winefield H, Venning A. Crying wolf? Australian adolescents’ perceptions of the ambiguity of visible indicators of mental health and authenticity of mental illness. Qual Res Psychol. 2017;14(2):171–99.

Armstrong C, Hill M, Secker J. Young people’s perceptions of mental health. Child Soc. 2000;14(1):60–72.

Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:1–7.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2004;169(7):467–73.

Järvensivu T, Törnroos J-Å. Case study research with moderate constructionism: conceptualization and practical illustration. Ind Mark Manage. 2010;39(1):100–8.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance (third edition). Process and methods PMG4. 2012. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/introduction .

Spencer L, Ritchie J, Lewis J, Dillon L. Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence. Cabinet Office. 2004. Available at: https://www.cebma.org/wp-content/uploads/Spencer-Quality-in-qualitative-evaluation.pdf .

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP qualitative research checklist: 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. 2013. Available at: https://www.casp-uk.net/#!casp-tools-checklists/c18f8 .

North Thames Research Appraisal Group (NTRAG). Critical review form for reading a paper describing qualitative research British Sociological Association (BSA). 1998.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):1–10.

Roose GA, John A. A focus group investigation into young children’s understanding of mental health and their views on appropriate services for their age group. Child Care Health Dev. 2003;29(6):545–50.

Johansson A, Brunnberg E, Eriksson C. Adolescent girls’ and boys’ perceptions of mental health. J Youth Stud. 2007;10(2):183–202.

Landstedt E, Asplund K, Gillander GK. Understanding adolescent mental health: the influence of social processes, doing gender and gendered power relations. Sociol Health Illn. 2009;31(7):962–78.

Svirydzenka N, Bone C, Dogra N. Schoolchildren’s perspectives on the meaning of mental health. J Public Ment Health. 2014;13(1):4–12.

Chisholm K, Patterson P, Greenfield S, Turner E, Birchwood M. Adolescent construction of mental illness: implication for engagement and treatment. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018;12(4):626–36.

Perre NM, Wilson NJ, Smith-Merry J, Murphy G. Australian university students’ perceptions of mental illness: a qualitative study. JANZSSA. 2016;24(2):1–15. Available at: https://janzssa.scholasticahq.com/article/1092-australian-university-students-perceptions-of-mental-illness-a-qualitative-study .

O’reilly M, Dogra N, Whiteman N, Hughes J, Eruyar S, Reilly P. Is social media bad for mental health and wellbeing? Exploring the perspectives of adolescents. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;23(4):601–13.

Molenaar A, Choi TS, Brennan L, et al. Language of health of young Australian adults: a qualitative exploration of perceptions of health, wellbeing and health promotion via online conversations. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):887.

Laidlaw A, McLellan J, Ozakinci G. Understanding undergraduate student perceptions of mental health, mental well-being and help-seeking behaviour. Stud High Educ. 2016;41(12):2156–68.

Nilsson B, Lindström UÅ, Nåden D. Is loneliness a psychological dysfunction? A literary study of the phenomenon of loneliness. Scand J Caring Sci. 2006;20(1):93–101.

Layard R. Happiness and the Teaching of Values. CentrePiece. 2007;12(1):18–23.

Horwitz AV. Transforming normality into pathology: the DSM and the outcomes of stressful social arrangements. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48(3):211–22.

Björkqvist K, Lagerspetz KM, Kaukiainen A. Do girls manipulate and boys fight? Developmental trends in regard to direct and indirect aggression. Aggressive Behav. 1992;18(2):117–27.

Rose AJ, Smith RL, Glick GC, Schwartz-Mette RA. Girls’ and boys’ problem talk: Implications for emotional closeness in friendships. Dev Psychol. 2016;52(4):629.

von dem Knesebeck O, Mnich E, Daubmann A, et al. Socioeconomic status and beliefs about depression, schizophrenia and eating disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(5):775–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0599-1 . [published Online First: Epub Date]|.

Tudor K. Mental health promotion: paradigms and practice (1st ed.). Routledge: 1996. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315812670 .

Ma KKY, Anderson JK, Burn AM. School-based interventions to improve mental health literacy and reduce mental health stigma–a systematic review. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2023;28(2):230–40.

Bjønness S, Grønnestad T, Storm M. I’m not a diagnosis: Adolescents’ perspectives on user participation and shared decision-making in mental healthcare. Scand J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Psychol. 2020;8(1):139–48.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Meldahl LG, Krijger L, Andvik MM, et al. Characteristics of the ideal healthcare services to meet adolescents’ mental health needs: A qualitative study of adolescents’ perspectives. Health Expect. 2022;25(6):2924–36.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Karlstad University. The authors report no funding source.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Health Service, Management and Policy, University of Florida, 1125, Central Dr. 32610, Gainesville, FL, USA

Linda Beckman & Sven Hassler

Department of Public Health Science, Karlstad University, Universitetsgatan 2, 651 88, Karlstad, Sweden

Linda Beckman

Department of School Development and Leadership, Malmö University, 211 19, Malmö, Sweden

Lisa Hellström

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

L.B and L.H conducted the literature search and scanned the abstracts. L.B drafted the manuscript, figures, and tables. All (L.B, L.H., S.H.) authors discussed and wrote the results, as well as the discussion. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sven Hassler .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Since data is based on published articles, no ethical approval is necessary.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Beckman, L., Hassler, S. & Hellström, L. Children and youth’s perceptions of mental health—a scoping review of qualitative studies. BMC Psychiatry 23 , 669 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05169-x

Download citation

Received : 06 May 2023

Accepted : 05 September 2023

Published : 14 September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05169-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Perceptions

- Public health

- Scoping review

BMC Psychiatry

ISSN: 1471-244X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Children’s Mental Health Research

- Mental health in the community

- Different data sources

- National data sets

Research on children’s mental health in the community

Project to learn about youth – mental health.

The Project to Learn About Youth – Mental Health (PLAY-MH) analyzed information collected from four communities. The focus was to study attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and other externalizing and internalizing disorders, as well as tic disorders in school-aged children. The purpose was to learn more about public health prevention and intervention strategies to support children’s health and development.

Read about the results of the Play-MH study

Study questions included:

- What percentage of children in the community had one or more externalizing, internalizing, or tic disorders?

- How frequently did these disorders appear together?

- What types of treatment were children receiving in their communities?

This project used the same methodology as the original Project to Learn about ADHD in Youth (PLAY) project. Read more about the original study approach here .

Other research

Read more about research on

- Tourette syndrome

CDC and partner agencies are working to understand the prevalence of mental disorders in children and how they impact their lives. Currently, it is not known exactly how many children have any mental disorder, or how often different disorders occur together, because no national dataset is available that looks at all mental, emotional, or behavioral disorders together.

Research on prevalence

What is It and Why is It Important?

Using different data sources

Healthcare providers, public health researchers, educators, and policy makers can get information about the prevalence of children’s mental health disorders from a variety of sources. Data sources, such as national surveys, community-based studies, and administrative claims data (like healthcare insurance claims), use different study methods and provide different types of information, each with advantages and disadvantages. Advantages and disadvantages for different data sources include the following:

- National surveys have large sample sizes that are needed to create estimates at the national and state levels. However, they also generally use a parent’s report of the child’s diagnosis, which means that the healthcare provider has to give an accurate diagnosis and the parent has to accurately remember what it was.

- Community-based studies offer the opportunity to observe children’s symptoms, which means that even children who have not been diagnosed or do not have the right diagnosis could be found. However, these studies are typically done in small geographic areas, so findings are not necessarily the same in other communities.

- Administrative claims are typically very large datasets with information on diagnosis and treatment directly from the providers, which allows tracking changes over time. Because they are recorded for billing purposes, diagnoses or services that would not be reimbursed from the specific health insurance might not be recorded in the data.

Using different sources of data together provides more information because it is possible to describe the following:

- Children with a diagnosed condition compared to children who have the same symptoms, but are not diagnosed

- Differences between populations with or without health insurance

- How estimates for mental health disorders change over time

Read more about using different data sources.

National data on children’s mental health

A comprehensive report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Mental Health Surveillance Among Children — United States, 2013 – 2019 , described federal efforts on monitoring mental disorders, and presented estimates of the number of children with specific mental disorders as well as for positive indicators of mental health. The report was developed in collaboration with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA ), the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH ), and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA ). It represents an update to the first ever cross-agency children’s mental health surveillance report in 2013.

Read a summary of the findings for the current report using data from 2012-2019

Read a summary of the findings for the first report using data from 2005-2011 .

The goal is now to build on the strengths of federal agencies serving children with mental disorders to:

- Develop better ways to document how many children have these disorders,

- Better understand the impacts of mental disorders,

- Inform needs for treatment and intervention strategies, and

- Promote the mental health of children.

This report is an important step on the road to recognizing the impact of childhood mental disorders and developing a public health approach to address children’s mental health.

Holbrook JR, Bitsko RB, Danielson ML, Visser SN. Interpreting the Prevalence of Mental Disorders in Children: Tribulation and Triangulation. Health Promotion Practice. Published online November 15, 2016 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27852820 .

To receive email updates about this topic, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

A Children's Health Perspective on Nano- and Microplastics

Affiliations.

- 1 Centre for Digital Life Norway, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway.

- 2 Centre for Global Health Inequalities Research (CHAIN), NTNU, Trondheim, Norway.

- 3 Ergonomics and Aerosol Technology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

- 4 Centre for Healthy Indoor Environments, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

- 5 Arctic Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland.

- 6 Department of Pesticides, Menoufia University, Menoufia, Egypt.

- 7 Institute of Environmental Assessment and Water Research, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain.

- 8 Department of Materials Science and Engineering, NTNU, Trondheim, Norway.

- 9 School of Health Systems and Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

- 10 Environment and Health Research Unit, Medical Research Council, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- 11 Department of Occupational Medicine and Public Health, Faroese Hospital System, Faroe Islands.

- 12 Department of Public Health and Nursing, Faculty of Medicine and Health Science, NTNU, Trondheim, Norway.

- 13 Laboratoire Biogéochimie des Contaminants Organiques, Institut français de recherche pour l'exploitation de la mer, Nantes, France.

- 14 Department of Biotechnology and Nanomedicine, SINTEF Industry, Trondheim, Norway.

- 15 Arctic Health, Thule Institute, University of Oulu and University of the Arctic, Oulu, Finland.

- 16 Department of General Hygiene, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Moscow, Russia.

- 17 Department of Biology, NTNU, Trondheim, Norway.

- PMID: 35080434

- PMCID: PMC8791070

- DOI: 10.1289/EHP9086

Background: Pregnancy, infancy, and childhood are sensitive windows for environmental exposures. Yet the health effects of exposure to nano- and microplastics (NMPs) remain largely uninvestigated or unknown. Although plastic chemicals are a well-established research topic, the impacts of plastic particles are unexplored, especially with regard to early life exposures.

Objectives: This commentary aims to summarize the knowns and unknowns around child- and pregnancy-relevant exposures to NMPs via inhalation, placental transfer, ingestion and breastmilk, and dermal absorption.

Methods: A comprehensive literature search to map the state of the science on NMPs found 37 primary research articles on the health relevance of NMPs during early life and revealed major knowledge gaps in the field. We discuss opportunities and challenges for quantifying child-specific exposures (e.g., NMPs in breastmilk or infant formula) and health effects, in light of global inequalities in baby bottle use, consumption of packaged foods, air pollution, hazardous plastic disposal, and regulatory safeguards. We also summarize research needs for linking child health and NMP exposures and address the unknowns in the context of public health action.

Discussion: Few studies have addressed child-specific sources of exposure, and exposure estimates currently rely on generic assumptions rather than empirical measurements. Furthermore, toxicological research on NMPs has not specifically focused on child health, yet children's immature defense mechanisms make them particularly vulnerable. Apart from few studies investigating the placental transfer of NMPs, the physicochemical properties (e.g., polymer, size, shape, charge) driving the absorption, biodistribution, and elimination in early life have yet to be benchmarked. Accordingly, the evidence base regarding the potential health impacts of NMPs in early life remains sparse. Based on the evidence to date, we provide recommendations to fill research gaps, stimulate policymakers and industry to address the safety of NMPs, and point to opportunities for families to reduce early life exposures to plastic. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP9086.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Child Health

- Environmental Exposure

- Microplastics*

- Tissue Distribution

- Microplastics

The DHS Program

- Childhood Mortality

- Family Planning

- Maternal Mortality

- Wealth Index

- MORE TOPICS

- Alcohol and Tobacco

- Child Health

- Fertility and Fertility Preferences

- Household and Respondent Characteristics

- Male Circumcision

- Maternal Health

- Tuberculosis

What child health-related data does The DHS Program collect?

DHS surveys routinely collect data on vaccination of children, prevalence and treatment of acute respiratory infections (ARI) and fever , and diarrhea . Prevention and treatment of malaria in children is usually presented in the malaria chapter of DHS final reports.

What are the DHS indicators related to child health?

- Vaccinations by source of information

- Vaccinations by background characteristics

- Prevalence and treatment of acute respiratory infection and of fever

- Diarrhea prevalence

- Hand-washing materials and facilities

- Disposal of child's stools

- Knowledge of diarrhea care

- Treatment of diarrhea

- Feeding practices during diarrhea

DHS surveys routinely collect data on infant and child mortality.

What are the SPA indicators related to child health?

SPA surveys collect a large range of child health service provision indicators. The SPA is designed to assess the availability of preventive services (such as immunization and growth monitoring) and outpatient care for sick children.

- Measuring Immunizations: The SPA examines adherence to the Expanded Program of Immunization (EPI) which includes one dose of TB (BCG) and measles vaccines and three doses of DPT and polio vaccines.

- Growth Monitoring: The SPA includes weighing of children and plotting the weight against standards to identify nutritional problems.

- Quality of Care for the Sick Child: The SPA assesses the availability of equipment, supplies and health system components necessary to provide quality outpatient care for sick children. Observation of the provider-patient interaction allows for evaluation of counseling and treatment, as well as adherence to IMCI (Integrated Management of Childhood Illness) protocols .

What is child health?

Child health refers to the period between birth and five years old when children are particularly vulnerable to disease, illness and death. From one month to five years of age, the main causes of death are pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, measles and HIV . Malnutrition is estimated to contribute to more than one third of all child deaths. Pneumonia is the prime cause of death in children under five years of age. Nearly three-quarters of all cases occur in just 15 countries. Addressing the major risk factors – including malnutrition and indoor air pollution – is essential to preventing pneumonia, as are vaccination and breastfeeding. Diarrheal diseases are a leading cause of sickness and death among children in developing countries. Breastfeeding helps prevent diarrhea among young children. Treatment for sick children with oral rehydration salts (ORS) combined with zinc supplements is safe, cost-effective, and saves lives. Though it is preventable with immunization, measles still kills an estimated 164,000 people each year – mostly children less than five years of age. A major factor contributing to child mortality is malnutrition, which weakens children and reduces their resistance to disease. About 20 million children under five worldwide are severely malnourished.

Photo credit: © 2007 Leah Gilbert, Courtesy of Photoshare. An Inca child in the Andes Mountains of Peru.

Featured publication.

Online Tool

Child health indicators involving vaccinations, acute respiratory infection and fever, and diarrheal disease are available on STATcompiler; compare among countries and analyze trends over time.

- Child Health at a Glance

- WHO - Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses (IMCI)

- Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health

- Maternal, Newborn and Child Survival Country Profiles

- UNICEF - pneumonia statistics

- UNICEF - diarrheal disease statistics

- UNICEF - immunization statistics

- Immunization Summary: a statistical reference containing data through 2009

- Measles Initiative

Maternal and Child Health Journal

- Timothy Dye

Latest issue

Volume 28, Issue 6

Latest articles

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patient-initiated encounters before the 6-week postpartum visit.

- Danielle L. Falde

- Lillian J. Dyre

- Enid Y. Rivera-Chiauzzi

Unpacking Breastfeeding Disparities: Baby-Friendly Hospital Designation Associated with Reduced In-Hospital Exclusive Breastfeeding Disparity Attributed to Neighborhood Poverty

- Larelle H. Bookhart

- Erica H. Anstey

- Melissa F. Young

Cross Sectional Survey of Antenatal Educators’ Views About Current Antenatal Education Provision

- Tamarind Russell-Webster

- Anna Davies

- Abi Merriel

Gestational Diabetes Prevalence Estimates from Three Data Sources, 2018

- Michele L.F. Bolduc

- Carla I. Mercado

- Denise C. Carty

Disparities in Postpartum Care Visits: The Dynamics of Parental Leave Duration and Postpartum Care Attendance

- Brianna Keefe-Oates

- Elizabeth Janiak

- Jarvis T. Chen

Journal updates

Call for papers: reducing poverty and its consequences.

Submission Deadline: Jul. 1, 2023

As one of the most enduring and complex social problems in the world, poverty, and its eradication, must be addressed through a variety of research and practice domains including social, behavioral, and public health perspectives. Our journal is calling for submissions to a multi-journal collection exploring this significant global issue.

Call for Papers: MCH History

MCH History: the past, the present, and the future — celebrating the 100th anniversary of the MCH Section in APHA and the 150th anniversary of APHA.

Guide to Reviewing Manuscripts

Alexander A Guide to Reviewing Manuscripts.pdf

Behind the Scenes: Publishing in the Maternal and Child Health Journal

Behind the Scenes: Publishing in the Maternal and Child Health Journal.pdf

Journal information

- Current Contents/Social & Behavioral Sciences

- Google Scholar

- IFIS Publishing

- Japanese Science and Technology Agency (JST)

- OCLC WorldCat Discovery Service

- Semantic Scholar

- Social Science Citation Index

- TD Net Discovery Service

- UGC-CARE List (India)

Rights and permissions

Editorial policies

© Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Pediatric Nursing Research Topics for Students: A Comprehensive Guide

This article was written in collaboration with Christine T. and ChatGPT, our little helper developed by OpenAI.

Pediatric nursing is a rewarding and specialized field that focuses on the care of infants, children, and adolescents. Research in pediatric nursing plays a crucial role in advancing knowledge, improving patient outcomes, and informing evidence-based practice. This article aims to provide a comprehensive guide on pediatric nursing research topics for students, offering examples and tips to help you select the perfect topic for your project.

Common Areas of Pediatric Nursing Research

Pediatric nursing research encompasses a wide range of topics aimed at improving the health and well-being of children. Find below some of the most common areas of research.

Neonatal and Infant Care

This area of research focuses on the health and development of newborns and infants, as well as the interventions and strategies that can enhance their well-being. Studies may investigate the impact of skin-to-skin contact on neonatal outcomes, the role of breastfeeding in infant nutrition and health, and the efficacy of various interventions for premature infants, such as music therapy, to reduce stress and improve development.

Topic Examples to Explore:

- The impact of skin-to-skin contact on neonatal bonding and breastfeeding success

- The role of kangaroo care in improving outcomes for preterm infants

- Strategies for managing neonatal abstinence syndrome in infants exposed to opioids in utero

- The effectiveness of different neonatal resuscitation techniques

- The impact of maternal mental health on infant development and attachment

- The role of probiotics in preventing necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants

- The benefits of human milk fortifiers for premature infants

- The long-term effects of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) environments on infant development

- The impact of neonatal jaundice on infant health and development

- The role of early intervention in improving outcomes for infants with congenital heart disease

- The benefits of non-invasive ventilation techniques in neonatal care

- The impact of delayed cord clamping on infant health

- The role of family-centered care in the NICU

- The effectiveness of developmental care interventions in the NICU

- The impact of neonatal hypoglycemia on long-term outcomes

- The role of therapeutic hypothermia in the management of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- The impact of various feeding methods on growth and development in preterm infants

- The effectiveness of music therapy for reducing stress and promoting development in the NICU

- The role of antibiotics in preventing early-onset neonatal sepsis

- The impact of antenatal corticosteroids on neonatal respiratory outcomes

- The effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for neonatal pain relief

- The role of parental involvement in infant care in the NICU

- The impact of noise and light reduction strategies on infant outcomes in the NICU

Medical Studies Overwhelming?

Delegate Your Nursing Papers to the Pros!

Get 15% Discount

+ Plagiarism Report for FREE

Child Development and Growth

Research in this area examines the various factors that influence a child’s physical, cognitive, and emotional development. Topics may include the effects of parenting styles on children’s behavior, the role of nutrition in growth and development, and the impact of early intervention programs on cognitive and language development.

- The effects of parenting styles on children’s cognitive and emotional development

- The impact of screen time on children’s language and social skills

- The role of play in promoting cognitive, social, and emotional development

- The impact of early literacy interventions on children’s reading skills and academic achievement

- The effects of childhood nutrition on cognitive development and school performance

- The role of sleep in children’s growth and development

- The impact of early intervention programs on language development in children with hearing loss

- The effectiveness of physical activity interventions for promoting motor development in children with disabilities

- Bridging the gap: tackling maternal and child health disparities between developed and underdeveloped countries

- The role of attachment and bonding in early childhood development

- The impact of adverse childhood experiences on cognitive and emotional development

- The role of cultural factors in shaping children’s development and socialization

- The effects of poverty on children’s cognitive, social, and emotional development

- The impact of preschool and kindergarten programs on children’s school readiness

- The role of creativity in promoting cognitive and emotional development in children

- The impact of bilingualism on children’s cognitive development and academic achievement

- The effects of parental involvement on children’s academic success and social development

- The role of nutrition in preventing stunted growth and promoting healthy development

- The impact of early exposure to music on children’s cognitive and social development

- The effectiveness of interventions for promoting resilience in children exposed to trauma

- The role of sports and physical activity in promoting children’s mental health and well-being

- The impact of bullying on children’s social and emotional development

- The role of peer relationships in children’s social and emotional development

- The effects of parental mental health on children’s development and well-being

Pediatric Mental Health

With increasing awareness of mental health issues in children, research in this area is crucial to understanding and addressing the mental health needs of young patients. Studies may explore the prevalence and risk factors of various mental health disorders, such as autism, ADHD, and depression, as well as the effectiveness of interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychopharmacological treatments.

- The prevalence and impact of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents

- The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for treating childhood depression

- The role of early intervention in preventing and treating childhood trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- The impact of bullying on the mental health of children and adolescents

- The relationship between autism spectrum disorders and mental health challenges in children

- The effectiveness of play therapy in addressing emotional and behavioral issues in children

- The role of family therapy in promoting positive mental health outcomes for children and adolescents

- The impact of substance abuse on the mental health of adolescents

- The effectiveness of school-based mental health interventions for children and adolescents

- The role of peer support in promoting positive mental health outcomes in children and adolescents

- The impact of social media on the mental health of children and adolescents

- The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions for promoting mental health in children and adolescents

- The role of resilience in protecting children’s mental health

- The impact of adverse childhood experiences on the development of mental health disorders in children and adolescents

- The effectiveness of early intervention programs for children at risk of developing mental health disorders

- The role of cultural factors in shaping children’s mental health and well-being

- The impact of parenting styles on children’s mental health outcomes

- The effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for treating mental health disorders in children and adolescents

- The role of sleep in promoting mental health and well-being in children and adolescents

- The impact of chronic illness on the mental health of children and adolescents

- The effectiveness of art therapy in promoting mental health and well-being in children and adolescents

- The role of sports and physical activity in promoting mental health and well-being in children and adolescents

- The impact of parental mental health on children’s mental health and well-being

Childhood Chronic Illness

Research in this area investigates the management, treatment, and long-term outcomes of chronic conditions in children, such as asthma, diabetes, and cystic fibrosis. Studies may examine the effectiveness of different management strategies, the role of family support in disease management, and the impact of these conditions on children’s quality of life.

- The impact of chronic illness on children’s growth and development

- The role of family-centered care in the management of childhood chronic illnesses

- The effectiveness of transition programs for adolescents with chronic illnesses moving to adult healthcare services

- The impact of school-based interventions for children with chronic illnesses

- The role of psychosocial interventions in promoting positive outcomes for children with chronic illnesses

- The impact of chronic illness on children’s mental health and well-being

- The effectiveness of telehealth interventions for managing childhood chronic illnesses

- The role of nutrition in the management of chronic illnesses in children

- The impact of chronic illness on children’s academic achievement and school performance

- The role of parent and caregiver support in managing childhood chronic illnesses

- The effectiveness of pain management strategies for children with chronic illnesses

- The impact of chronic illness on children’s social and emotional development

- The role of peer support in promoting positive outcomes for children with chronic illnesses

- The effectiveness of exercise and physical activity interventions for children with chronic illnesses

- The impact of chronic illness on the family system and sibling relationships

- The role of cultural factors in shaping the experiences of children with chronic illnesses

- The effectiveness of community-based programs for supporting children with chronic illnesses

- The impact of chronic illness on children’s quality of life

- The role of healthcare coordination in the management of childhood chronic illnesses

- The effectiveness of integrative medicine approaches for managing chronic illnesses in children

- The impact of chronic illness on children’s self-concept and identity development