125 Breast Cancer Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best breast cancer topic ideas & essay examples, 💡 most interesting breast cancer topics to write about, 📌 simple & easy breast cancer essay titles, 👍 good essay topics on breast cancer.

- Breast Cancer: Concept Map and Case Study Each member of the interdisciplinary team involved in treating patients with cancer and heart disease should focus on educational priorities such as:

- Breast Cancer and Its Population Burden The other objectives that are central to this paper are highlighted below: To determine which group is at a high risk of breast cancer To elucidate the impact of breast cancer on elderly women and […] We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- Mindfulness Practice During Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer She discusses the significance of the study to the nursing field and how nurses can use the findings to help their patients cope with stress.

- Breast Cancer: The Effective Care Domain Information about how the patient is seen, how often the patient is seen, and whether she will return for mammograms can be collected and analyzed to verify the successful intervention to extend consistency with mammograms.

- Garden Pesticide and Breast Cancer Therefore, taking into account the basic formula, the 1000 person-years case, the number of culture-positive cases of 500, and culture-negative of 10000, the incidence rate will be 20 new cases.

- Breast Cancer as a Genetic Red Flag It is important to note that the genetic red flags in Figure 1 depicted above include heart disease, hypertension, and breast cancer.

- Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium Analysis Simultaneously, the resource is beneficial because it aims to “improve the delivery and quality of breast cancer screening and related outcomes in the United States”.

- Drinking Green Tea: Breast Cancer Patients Therefore, drinking green tea regularly is just a necessity- it will contribute to good health and physical vigor throughout the day and prevent severe diseases.

- Breast Cancer Prevention: Ethical and Scientific Issues Such information can potentially impact the patient and decide in favor of sharing the information about the current condition and risks correlating with the family history.

- Breast Cancer: Epidemiology, Risks, and Prevention In that way, the authors discuss the topics of breast cancer and obesity and the existing methods of prevention while addressing the ethnic disparities persistent in the issue.

- Breast Cancer Development in Black Women With consideration of the mentioned variables and target population, the research question can be formulated: what is the effect of nutrition and lifestyle maintained on breast cancer development in black women?

- Breast Cancer in Miami Florida The situation with the diagnosis of breast cancer is directly related to the availability of medicine in the state and the general awareness of the non-population.

- Breast Cancer: Genetics and Malignancy In the presence of such conditions, the formation of atypical cells is possible in the mammary gland. In the described case, this aspect is the most significant since it includes various details of the patient’s […]

- Genes Cause Breast Cancer Evidence suggests the role of BRCA1 in DNA repair is more expansive than that of BRCA2 and involves many pathways. Therefore, it is suggested that BRCT ambit containing proteins are involved in DNA repair and […]

- Breast Cancer. Service Management The trial specifically looks at the effect on breast-cancer mortality of inviting women to screening from age 40 years compared with invitation from age 50 years as in the current NHS breast-screening programme.

- Fibrocystic Breast Condition or Breast Cancer? The presence of the fibrocystic breast condition means that the tissue of the breast is fibrous, and cysts are filled with the liquid or fluid. The main characteristic feature of this cancer is that it […]

- Coping With Stress in Breast Cancer Patients Therefore, it is important for research experts to ensure and guarantee adherence to methodologies and guidelines that define scientific inquiry. However, various discrepancies manifest with regard to the initiation and propagation of research studies.

- Breast Self-Examination and Breast Cancer Mortality Though it is harsh to dismiss self-exams entirely due to studies that indicate little in deaths of women who performed self-exams and those who did not, the self-exams should not be relied on exclusively as […]

- Breast Self-Exams Curbing Breast Cancer Mortality The results of the study were consistent with the findings of other studies of the same nature on the effectiveness of breast self-examination in detecting and curbing breast cancer.

- Taxol Effectiveness in Inhibiting Breast Cancer Cells The following were the objectives of this experiment: To determine the effectiveness of Taxol in inhibiting breast cancer cells and ovarian cancer cells using culture method.

- Control Breast Cancer: Nursing Phenomenon, Ontology and Epistemology of Health Management Then, the evidence received is presented in an expert way leading to implementation of the decision on the management of the disease.

- Breast Cancer: Effects of Breast Health Education The design of the research focused on research variables like skills, performance, self-efficacy, and knowledge as the researchers aimed at examining the effectiveness of these variables among young women who underwent training in breast cancer […]

- Community Nursing Role in Breast Cancer Prevention However, early detection still remains important in the prevention and treatment of breast cancer. The community has thus undertaken activities aimed at funding the awareness, treatment and research in order to reduce the number of […]

- Self-Examination and Knowledge of Breast Cancer Among Female Students Shin, Park & Mijung found that a quarter of the participants practiced breast self-examination and a half had knowledge regarding breast cancer.

- “Tracking Breast Cancer Cells on the Move” by Gomis The article serves the purpose of examining the role of NOG, a gene that is essential in bone development and its role in breast cancer.

- Breast Cancer Survivorship: Are African American Women Considered? The finding of the analysis is that the issue of cancer survivorship is exclusive, developing, and at the same time it depends on what individuals perceive to be cancer diagnosis as well as personal experiences […]

- Gaining Ground on Breast Cancer: Advances in Treatment The article by Esteva and Hortobagyi discusses breast cancer from the aspect of increased survival rates, the novel treatments that have necessitated this and the promise in even more enhanced management of breast cancer.

- Effects of Hypoxia, Surrounding Fibroblasts, and p16 Expression on Breast Cancer The study was conducted to determine whether migration and invasion of breast cancer cells were stimulated by hypoxia, as well as determining whether the expression of p16 ectopically had the potential to modulate the cell […]

- Breast Cancer: Preventing, Diagnosing, Addressing the Issue In contrast to the MRI, which presupposes that the image of the tissue should be retrieved with the help of magnetic fields, the mammography tool involves the use of x-rays.

- Dietary Fat Intake and Development of Breast Cancer This study aimed to determine the relationship between dietary fat intake and the development of breast cancer in women. The outcome of the study strongly suggests that there is a close relationship between a high […]

- The Detection and Diagnosis of Breast Cancer The severity of cancer depends on the movement of the cancerous cells in the body and the division and growth or cancerous cells.

- Breast Cancer: WMI Research and the Current Approaches Although the conclusions provided by the WHI in the study conducted to research the effects of estrogen and progesterone cessation on the chance of developing a breast cancer do not comply with the results of […]

- Breast Cancer Susceptibility Gene (BRCA2) The mechanisms underlying the genetic predisposition to a particular disease are manifold and this concept is the challenging one to the investigators since the advent of Molecular Biology and database resources.

- Prediction of Breast Cancer Prognosis It has been proposed that the fundamental pathways are alike and that the expression of gene sets, instead of that of individual genes, may give more information in predicting and understanding the basic biological processes.

- Breast Cancer Survivors: Effects of a Psychoeducational Intervention While the conceptual framework is justified in analysis of the quality of life, there is the likelihood of influence of the context with quality of life adopting different meanings to patients in different areas and […]

- Providers’ Role in Quality Assurance in Breast Cancer Screening In order to ensure the quality assurance of mammography, the providers involved in the procedure need to be aware of the roles they ought to play.

- Clinical Laboratory Science of Breast Cancer The word cancer is itself so much dreaded by people that the very occurrence of the disease takes half of the life away from the patient and the relatives.

- Induced and Spontaneous Abortion and Breast Cancer Incidence Among Young Women There is also no question as to whether those who had breast cancer was only as a result of abortion the cohort study does not define the total number of women in population.

- New Screening Guidelines for Breast Cancer On the whole, the Task Force reports that a 15% reduction in breast cancer mortality that can be ascribed to the use of mammograms seems decidedly low compared to the risks and harm which tend […]

- Breast Cancer in Afro- and Euro-Americans It is seen that in the age group of more than 50 years, EA was more at risk of contracting cancer, as compared to AA.

- Breast Cancer Assessment in London In light of these developments, it is therefore important that an evaluation of breast cancer amongst women in London be carried out, in order to explore strategies and policy formulations that could be implemented, with […]

- Breast Cancer: Crucial Issues The textbook also notes the significant racial differences in survival rates, mainly attributed to socioeconomic and cultural factors, including lack of available specialized care. Medical professionals and local communities highly appreciate the value of early […]

- Breast Cancer: At-Risk Population, Barriers, and Improvement Thus, the principal purpose of Part Two is to explain why older women face a higher risk of getting breast cancer, what barriers lead to this adverse state of affairs, and how to improve the […]

- Breast Cancer: Moral and Medical Aspects In addition to the question of the surgery, there is an ethical problem associated with the genetic characteristics of the disease.

- Breast Cancer and AIDS: Significant Issues in the United States in the Late 20th Century Thus, the given paper is going to explain why these activists challenged regulatory and scientific authorities and what they demanded. That is why the enthusiasts challenged their practices and made specific demands to improve the […]

- Breast Cancer Risk Factors: Genetic and Nutritional Influences However, the problems of genetics contribute to the identification of this disease, since the essence of the problem requires constant monitoring of the state of the mammary glands to detect cancer at an early stage.

- Breast Cancer Genetics & Chromosomal Analysis In this paper, the chromosomal analysis of breast cancer will be assessed, and the causes of the disorder will be detailed.

- Breast Cancer: The Case of Anne H. For this reason, even females with a high level of health literacy and awareness of breast cancer, such as Anne H, might still belong to the group risk and discover the issue at its late […]

- Breast Cancer Diagnosis Procedure in Saudi Arabia The fact is that, the health care program in this geographic area is associated with the encouragement of all the women in the area to be subjected to the examination for the breast cancer, as […]

- Breast Cancer and the Effects of Diet The information in noted clause is only a part of results of the researches spent in the field of the analysis of influence of a diet on a risk level of disease in cancer.

- Genetic Predisposition to Breast Cancer: Genetic Testing Their choice to have their first baby later in life and hormonal treatment for symptoms of menopause further increase the risk of breast cancer in women.

- Health Psychology: Going Through a Breast Cancer Diagnosis He is unaware that she has been diagnosed with depression and that she is going for breast screening Stress from work is also a contributing factor to her condition.

- Breast Cancer: Causes and Treatment According to Iversen et al this situation is comparable to the finding of abnormal cells on the surface of the cervix, curable by excision or vaporization of the tissue.

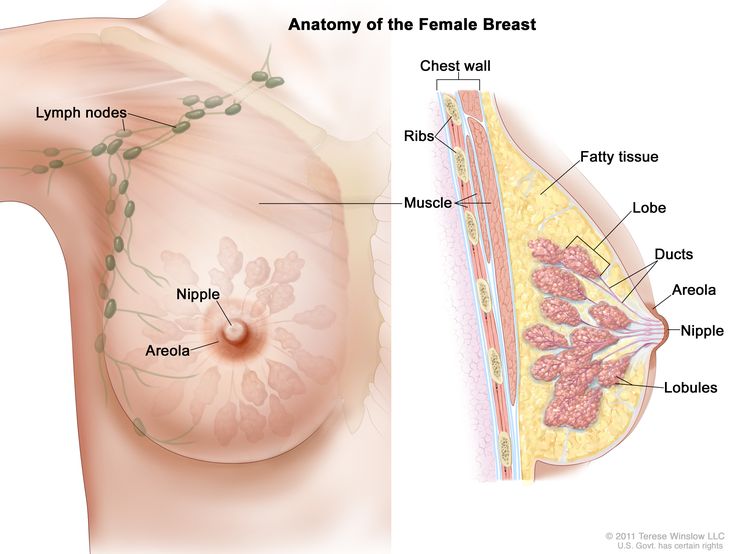

- Monoclonal Antibodies in Treating Breast Cancer The most important function of the lymph glands is that their tissue fluid carries the cancer cells that have been detached from the tumour to the closely located lymph gland.

- Breast Cancer: Women’s Health Initiative & Practices The new standard of care shows evidence that a low-fat diet, deemed insignificant by the WHI study, is beneficial to women for preventing or improving their risks of breast cancer.

- Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer Pathophysiology The contemporary understanding of the etiopathogenesis of breast cancer addresses the origin of invasive cancer through a substantive number of molecular alterations at the cellular level.

- Complex Fibroadenoma and Breast Cancer Risk Furthermore, KB decided that she did not need to remove the lump surgically she was advised to document changes after regular breast exams and return to the clinic in case of new concerns.

- Breast Cancer: Health Psychology Plan The goal of the plan is to identify the psychological issues and health priorities of the subject and propose a strategy for addressing them.

- Best Practices in Breast Cancer Care Based on this, the final stage of therapy should include comprehensive support for patients with breast cancer as one of the main health care practices within the framework of current treatment guidelines.

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Women With Breast Cancer The treatment of breast CA has developed over the past 20 years, and many treatment centers offer a variety of modalities and holistic treatment options in addition to medical management.

- Breast Cancer Screening in Young American Women It is proud to be at the forefront of widespread public health initiatives to improve the education and lives of young women.

- Screening for Breast Cancer The main goal of this paper is to describe the specific set of clinical circumstances under which the application of screening is the most beneficial for women aged 40 to 74 years.

- Annual Breast Cancer Awareness Campaign It may also need more time to be implemented as the development of the advertisement, and all visuals will take time.

- Breast Cancer Patients’ Life Quality and Wellbeing The article “Complementary Exercise and Quality of Life in Patients with Breast Cancer” examines the role of complementary exercises towards improving the lives of women with breast cancer.

- Breast Cancer Patients’ Functions and Suitable Jobs The key symptom of breast cancer is the occurrence of a protuberance in the breast. A screening mammography, scrutiny of the patient’s family history and a breast examination help in the diagnosis of breast cancer.

- Jordanian Breast Cancer Survival Rates in 1997-2002 This objective came from the realization that the best way to test the efficacy of breast cancer treatment and to uncover intervening factors influencing the efficacy of these treatments was to investigate the rates of […]

- Breast Cancer Awareness Among African Americans There are reasons that motivate women to seek mammography for example the belief that early detection will enable them treat the cancer in early stages, and their trust for the safety of mammogram. Social marketing […]

- Breast Cancer Screening Among Non-Adherent Women This is one of the aspects that can be identified. This is one of the short-comings that can be singled out, and this particular model may not be fully appropriate in this context.

- Breast Cancer: Treatment and Rehabilitation Options Depending on the site of occurrence, breast cancer can form ductal carcinomas and lobular carcinomas if they occur in the ducts and lobules of the breast, respectively. Breast cancer and treatment methods have significant effects […]

- Women Healthcare: Breast Cancer Reducing the levels of myoferlin alters the breast cancer cells’ mechanical properties, as it is evident from the fact that the shape and ability of breast cancer cells to spread is low with reduced production […]

- Breast Cancer Public Relations Campaign Audiences It is clear that the breast cancer campaign will target at women in their 30-40s as this is one of the most vulnerable categories of women as they often pay little attention to the […]

- Health Information Seeking and Breast Cancer Diagnosis Emotional support is also concerned with the kind of information given to patients and how the information is conveyed. It is equally significant to underscore the role of information in handling breast cancer patients immediately […]

- Current Standing of Breast Cancer and Its Effects on the Society It then places particular focus on the testing and treatment of breast cancer, the effects and conditions associated with it, from a financial point of view, and the possible improvements worth making in service or […]

- Breast Cancer: Disease Prevention The first indicator of breast cancer is the presence of a lump that feels like a swollen matter that is not tender like the rest of the breast tissues.

- Breast Cancer Definition and Treatment In the case where “the cells which appear like breast cancer are still confined to the ducts or lobules of the breast, it is called pre-invasive breast cancer”.”The most widespread pre-invasive type of breast cancer […]

- Breast Cancer Symptoms and Causes The mammogram is the first indication of breast cancer, even though other indications such as the presence of the lymph nodes in the armpits are also the early indications of breast cancer.

- Breast Cancer Incidence and Ethnicity This paper explores the different rates of breast cancer incidence as far as the different ethnic groups in the US are concerned as well as the most probable way of reducing the rates of incidence […]

- Treatment Options for Breast Cancer This type of breast cancer manifests itself in the tubes/ducts which form the channel for transporting milk from the breast to the nipple.”Lobular carcinoma: this type of cancer usually begins in the milk producing regions […]

- Risk Factors, Staging, and Treatment of Breast Cancer This is so because huge amounts of resources have been used in the research and the development of the breast cancer drugs that in effect help the body to combat the cancer by providing additional […]

- Case Management for Breast Cancer Patients In this respect, preventive measures should be taken in order to decrease the mortality rates all over the world in terms of cancer illness and breast cancer in particular.

- The Second Leading Cause of Death is the Breast Cancer

- The Benefits and Effects of Exercise on Post-Treatment Breast Cancer Patients

- Women’s Experiences Undergoing Reconstructive Surgery After Mastectomy Due To Breast Cancer

- Advanced Technology Of The Treatment Of Breast Cancer

- Using Genetic Testing For Breast Cancer

- The role of Perivascular Macrophages in Breast Cancer Metastasis

- The Psychological Aspect Of Coping With Breast Cancer

- An Analysis of an Alternative Prevention in Breast Cancer for Young Women in America

- The Complicated Biology of Breast Cancer

- The Impact Of Tamoxifen Adjuvant Therapy On Breast Cancer

- The Prevalence Of Breast Cancer Among Black Women

- The Embodiment Theory, Holistic Approach And Breast Cancer In The South African Context

- The Long-Term Evolution of Quality of Life for Breast Cancer Treated Patients

- The Signs and Early Prevention of Breast Cancer

- The Effect of Fast Food In Developing Breast Cancer among Saudi Populations

- The Effect Of Breastfeeding On Ovarian And Breast Cancer

- The Best Method Of Medicine For The Treatment Of Breast Cancer: Cam Or Drugs

- The Causes of Breast Cancer – Genetically or Environmentally Influenced

- The Symptoms, Causes and Treatment of Breast Cancer, a Malignant Disease

- The Risks, Characteristics and Symptoms of Breast Cancer, a Malignant Disease

- The Most Common Cancer In The UK: Breast Cancer

- Types Of Preventive Services For A Higher Risk Of Breast Cancer

- The Effect of Raloxifene on Risk of Breast Cancer in Postmenopausal Women

- The Impact of Culture and Location on Breast Cancer Around the World

- Understanding Breast Cancer, Its Triggers and Treatment Options

- The Risk, Development, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Breast Cancer in Women

- The Pathophysiology of Breast Cancer

- The Effects Of DNA Methylation On Breast Cancer

- The Treatment and Management Options for Breast Cancer Patients

- Alternative Forms Of Medicine For Breast Cancer Rates

- The Impact of Nutrition on Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer

- The Economic Evaluation of Screening for Breast Cancer: A Tentative Methodology

- The Etymology of Breast Cancer, Types, Risk Factors, Early Detection Methods, and Demographics

- What Are The Symptoms And Treatments For Breast Cancer

- Treatments And Treatment Of Breast Cancer Therapy

- The Various Views and Approaches in the Treatment and Management of Breast Cancer

- The Growing Health Problem of Breast Cancer in the United States

- The Importance of Considering Breast Cancer Prevention Aside from Treatment

- The Different Ways That Can Reduce the Risk of Having Breast Cancer

- The Use of Radiation for Detection and Treatment of Breast Cancer

- The Condition Of Breast Cancer And Its Relevant Treatment

- The Relationship between a High-Dairy Diet and Breast Cancer in Women

- Treatment of Solid Tumors including Metastatic Breast Cancer

- Which Is More Effective In Reducing Arm Lymphoedema For Breast Cancer Patients

- The Use Of Telomerase In Diagnosis, Prognosis, And Treatment Of Cancer: With A Special Look At Breast Cancer

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 2). 125 Breast Cancer Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/breast-cancer-essay-topics/

"125 Breast Cancer Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 2 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/breast-cancer-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '125 Breast Cancer Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 2 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "125 Breast Cancer Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/breast-cancer-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "125 Breast Cancer Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/breast-cancer-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "125 Breast Cancer Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/breast-cancer-essay-topics/.

- Cancer Essay Ideas

- Skin Cancer Questions

- Leukemia Topics

- Palliative Care Research Topics

- Pathogenesis Research Ideas

- Tuberculosis Questions

- DNA Essay Ideas

- Biochemistry Research Topics

- Gene Titles

- Human Papillomavirus Paper Topics

- Nursing Care Plan Paper Topics

- Hypertension Topics

- Stem Cell Essay Titles

- Osteoarthritis Ideas

- Diabetes Questions

- About Breast Cancer

- Find Support

- Get Involved

- Free Resources

- Mammogram Pledge

- Wall of Support

- In The News

- Recursos en Espa ñ ol

About Breast Cancer > Diagnosis > Breast Cancer Screening

- What Is Cancer?

- Causes of Breast Cancer

- Breast Cancer Facts & Stats

- Breast Tumors

- Breast Anatomy

- Male Breast Cancer

- Growth of Cancer

- Risk Factors

- Genetic Testing for Breast Cancer

- Other Breast Cancer Genes

- BRCA: The Breast Cancer Gene

- What To Do If You Tested Positive

- Breast Cancer Signs and Symptoms

- Breast Lump

- Breast Pain

- Breast Cyst

Breast Self-Exam

Clinical breast exam.

- How to Schedule a Mammogram

- Healthy Habits

Breast Cancer Screening

- Diagnostic Mammogram

- Breast Biopsy

- Waiting For Results

- Breast Cancer Stages

- Stage 2 (II) And Stage 2A (IIA)

- Stage 3 (III) A, B, And C

- Stage 4 (IV) Breast Cancer

- Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS)

- Invasive Ductal Carcinoma (IDC)

- Lobular Carcinoma In Situ (LCIS)

- Invasive Lobular Cancer (ILC)

- Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC)

- Inflammatory Breast Cancer (IBC)

- Metastatic Breast Cancer (MBC)

- Breast Cancer During Pregnancy

- Other Types

- Choosing Your Doctor

- Lymph Node Removal & Lymphedema

- Breast Reconstruction

- Chemotherapy

- Radiation Therapy

- Hormone Therapy

- Targeted Therapy

- Side Effects of Breast Cancer Treatment and How to Manage Them

- Metastatic Breast Cancer Trial Search

- Standard Treatment vs. Clinical Trials

- Physical Activity, Wellness & Nutrition

- Bone Health Guide for Breast Cancer Survivors

- Follow-Up Care

- Myth: Finding a lump in your breast means you have breast cancer

- Myth: Men do not get breast cancer; it affects women only

- Myth: A mammogram can cause breast cancer or spread it

- Myth: If you have a family history of breast cancer, you are likely to develop breast cancer, too

- Myth: Breast cancer is contagious

- Myth: If the gene mutation BRCA1 or BRCA2 is detected in your DNA, you will definitely develop breast cancer

- Myth: Antiperspirants and deodorants cause breast cancer

- Myth: A breast injury can cause breast cancer

- Myth: Breast cancer is more common in women with bigger breasts

- Myth: Breast cancer only affects middle-aged or older women

- Myth: Breast pain is a definite sign of breast cancer

- Myth: Consuming sugar causes breast cancer

- Myth: Carrying a phone in your bra can cause breast cancer

- Myth: All breast cancers are the same

- Myth: Bras with underwire can cause breast cancer

- Can physical activity reduce the risk of breast cancer?

- Can a healthy diet help to prevent breast cancer?

- Does smoking cause breast cancer?

- Can drinking alcohol increase the risk of breast cancer?

- Is there a link between oral contraceptives and breast cancer?

- Is there a link between hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and breast cancer?

- How often should I do a breast self exam (BSE)?

- Does a family history of breast cancer put someone at a higher risk?

- Are mammograms painful?

- How does menstrual and reproductive history affect breast cancer risks?

- How often should I go to my doctor for a check-up?

- What kind of impact does stress have on breast cancer?

- What celebrities have or have had breast cancer?

- Where can I find a breast cancer support group?

- Can breastfeeding reduce the risk of breast cancer?

- Is dairy (milk) linked to a higher risk of breast cancer?

- Is hair dye linked to a higher risk of breast cancer?

- NEW! Smart Bites Cookbook: 7 Wholesome Recipes in 35 Minutes (or Less!)

- Weekly Healthy Living Tips: Volume 2

- Most Asked Questions: Breast Cancer Signs & Symptoms

- Cancer Caregiver Guide

- Breast Cancer Surgery eBook

- 10 Prompts to Mindfulness

- How to Talk About Breast Health

- Family Medical History Checklist

- Healthy Recipes for Cancer Patients eBook

- Chemo Messages

- Most Asked Questions About Breast Cancer Recurrence

- Breast Problems That Arent Breast Cancer eBook

- Nutrition Care for Breast Cancer Patients eBook

- Finding Hope that Heals eBook

- Dense Breasts Q&A Guide

- Breast Cancer Recurrence eBook

- What to Say to a Cancer Patient eBook

- Weekly Healthy Living Tips

- Bra Fit Guide

- Know the Symptoms Guide

- Breast Health Guide

- Mammogram 101 eBook

- 3 Steps to Early Detection Guide

- Abnormal Mammogram eBook

- Healthy Living & Personal Risk Guide

- What Every Woman Needs to Know eBook

- Breast Cancer Resources

Last updated on Jan 17, 2024

Breast cancer screening can detect cancer before signs or symptoms develop. While breast cancer screening cannot prevent breast cancer, it can help find breast cancer in its earliest and most treatable stage. When detected in the localized (early) stage, breast cancer has a 5-year relative survival rate of 99%, according to the American Cancer Society.

Regardless of your risk of breast cancer, it is important to talk with your healthcare provider about the best screening tests, recommendations, and timelines for screening.

Table of Contents

Use these links to jump to the breast cancer screening information you need:

What is Breast Cancer Screening? Breast Cancer Screening Recommendations Breast Cancer Screening Tests Breast Cancer Diagnostic Tests Benefits and Risks of Breast Cancer Screening Breast Cancer Screening for Men Breast Cancer Screening Facts Breast Cancer Screening FAQs

What is Breast Cancer Screening?

Breast cancer screening can detect breast cancer before it has spread and before there are symptoms to help reduce the number of people who die from cancer. Screening can also identify those who may need more frequent or additional tests to check for breast cancer.

There are different types of breast cancer screening tests, as well as different age recommendations to begin screenings. The different tests and recommendations are listed below, and you can also check with your doctor to determine which screenings are right for you and at what ages.

The more you know about breast cancer screening, the more you can take charge of your breast health.

Breast Cancer Screening Recommendations

The U.S. Preventative Services Task Force states that women should start receiving mammograms at the age of 40. However, women at higher risk of developing breast cancer may benefit from beginning regular mammography earlier than the age of 40. Family health history can inform the decision to undergo earlier breast cancer screening.

Below are general breast health screening recommendations for women at average risk of breast cancer. Please consult with your healthcare provider on when is the best time for you to begin breast health screenings based on your specific situation and any risk factors that may be present.

High Risk Breast Cancer Screening

Women at higher risk for breast cancer can benefit from screening at an earlier age, as well as from annual breast MRIs in addition to mammography. The American Cancer Society recommends most women at high risk begin screening at age 30, or upon your doctor’s recommendation.

Your doctor can help you assess if you are at higher risk of developing breast cancer. Risk factors include a personal or family history of breast cancer, a BRCA1 or BRCA2 inherited gene mutation , previous radiation to the chest area, and other gene mutations or health conditions.

In addition, breast cancer screening for dense breasts can be more challenging. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) now requires mammogram providers to notify women if they have dense breast tissue and recommend consultation with a healthcare provider on potential additional screening, since dense breast tissue can make it more difficult to spot breast cancer.

Breast cancer screening after mastectomy is not needed on the side of the body where breast tissue was removed; breast cancer screening after double mastectomy should no longer be required since there likely won’t be enough breast tissue remaining for a mammogram.

Talk with your doctor or healthcare provider to assess breast cancer risk and determine the best age for you to begin breast cancer screening.

Breast Cancer Screening Tests

Although there are several types of breast cancer screening tests available, mammography is the most common and most accurate form of screening.

A breast self-exam involves looking at and feeling your breasts for potential lumps or swelling. If you are familiar with how your breasts typically look and feel, you will be more likely to notice any changes.

A breast self-exam should be performed once a month by all women. Premenopausal women should perform their self-exam the week after their cycle. Postmenopausal women should choose a consistent time each month to perform their self-exam.

While the majority of breast lumps are not breast cancer , all breast lumps should be investigated by a healthcare professional. If you’re not sure how to perform a breast self-exam, download the Know the Symptoms Guide for instructions.

During a clinical breast examination , a healthcare professional carefully looks and feels for any differences in breast shape and size, as well as lumps, dimpling, rashes, or anything else unusual. Clinical breast exams are often performed during your annual medical check-up or well-woman exam, beginning around the age of 20.

A low-dose x-ray of the breasts, mammograms are the best way to find breast cancer in its early stages. Mammograms can often find breast cancer or breast changes long before symptoms develop. If something is detected on an annual mammogram, typically known as a screening mammogram, additional tests, such as a diagnostic mammogram , will likely be ordered.

Mammograms are performed with a machine that has two plates that compress the breast and spread the tissue apart, providing a clearer picture of the breast.

2D screening mammography, which typically takes one picture of the breast from the side and one from above, was the standard for many years.

Today, 3D mammograms, also known as digital breast tomosynthesis, are more common and more accurate at detecting breast cancer. They also work well for women with dense breast tissue and reduce the need for follow-up screening. A more advanced type of imaging, a 3D mammogram takes multiple images of the breast from different angles. Not every insurance plan covers 3D mammography, although more are now doing so.

NBCF offers a free Mammogram 101 resource that helps you prepare for your mammogram.

Breast Cancer Diagnostic Tests

A breast MRI uses radio waves and magnets to take pictures of the breast and may be used in conjunction with mammograms for women at higher risk of breast cancer or those who have dense breast tissue . Likewise, if your initial breast screening exam is not conclusive, your doctor may order an MRI to take a closer look.

Breast MRI imaging creates detailed pictures of specific areas within the breast that can help your medical team distinguish between normal and potentially cancerous tissue.

Sometimes used in conjunction with other breast cancer screening tests, a breast ultrasound uses sound waves to view the inside of the breasts. The ultrasound generates a picture called a sonogram, which can help measure the size and location of a lump and determine if it is a cyst , which is not typically cancerous, or a cancerous tumor.

Genetic Screening

Genetic screening for breast cancer scans for mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes . Some people inherit mutations in these genes, which can increase their risk of breast cancer as well as ovarian and pancreatic cancer.

Women with a family history of breast cancer are also at higher risk of getting breast cancer; however, most women with a family history of breast cancer do not have an inherited gene that increases their risk. It is important to weigh the pros and cons of genetic testing and screening with your family and doctor. To keep track of your family medical history to share with family members and your healthcare team, use NBCF’s free Family Medical History Checklist .

Benefits and Risks of Breast Cancer Screening

As with many medical tests, there are both benefits and risks. However, the benefits of breast cancer screening far outweigh the risks.

Benefits of Screening

The most significant benefit of breast cancer screening is reduced mortality. Women who receive annual mammograms from the ages of 40 to 84 experience a 40% lower breast cancer mortality rate than women with no screenings, according to research . Mammograms also decrease the number of women diagnosed with cancer in a later stage, when it is more difficult to treat and more likely to have spread.

Regular breast cancer screening also decreases healthcare costs, since cancer diagnosed at an earlier stage is usually less expensive to treat. Finally, breast cancer screening can provide peace of mind and a reminder of the importance of focusing on overall health and wellness.

Risks of Screening

The chief risk of screening is a false positive result, and the anxiety that may cause. A false positive is when something may initially look like cancer, but turns out not to be cancer upon further examination. Initial false-positive results may lead to additional testing, such as a biopsy, and can create unwarranted anxiety.

However, with recent advancements in mammogram technology, radiologists consider the risk of a false positive to be relatively small. The general consensus is that most women and doctors are willing to risk the small chance of a false positive over missing something suspicious found on a routine mammogram.

Radiation can be risky for women who are pregnant. Pregnant women should always let their doctor or x-ray technician know that they are expecting since pregnant women should limit or forgo any screenings or treatments involving radiation.

While no screening test is 100% accurate, regular mammograms have been repeatedly shown to significantly reduce the risk of dying from breast cancer.

Breast Cancer Screening for Men

Currently, there are no guidelines on screening men for breast cancer, and male breast cancer remains extremely rare, representing less than 1% of all breast cancer cases.

It is generally easier for men and their healthcare providers to feel a breast tumor since men have little breast tissue, yet men with breast cancer have a higher mortality rate than women due to lower awareness and likelihood of seeking treatment. Breast exams and occasionally mammograms and ultrasound may be appropriate for men who have a strong family history of male or female breast cancer or who have BRCA gene mutations .

Breast Cancer Screening Facts

In the United States, 1 in 8 women will develop breast cancer in her lifetime. It is the second most common type of cancer for women, following skin cancer.

About 65% of breast cancer cases are diagnosed in the localized stage, before the cancer has spread outside of the breast. The 5-year relative survival rate for breast cancer detected at this stage is 99%, which is why awareness and regular screenings are so critically important.

Unfortunately, there are notable disparities in breast cancer screening. Nearly half of uninsured women delay or go without care due to costs. In addition, the death rate for breast cancer among Black women is 40% higher than it is for white women, and it is the leading cause of cancer death for Hispanic women in the United States.

National Breast Cancer Foundation shares the latest statistics on breast cancer and breast cancer disparities. In addition, NBCF’s National Mammography Program provides resources on free mammograms and diagnostic services.

Breast Cancer Screening FAQs

When should you start screening for breast cancer .

Well-woman exams, which can include clinical breast exams, and Pap tests are recommended starting at age 20.

Mammograms are recommended starting at age 40 for women of average breast cancer risk. However, if you have a significant family history of breast cancer, such as one or more first-degree relatives diagnosed with breast cancer, or a first-degree relative diagnosed under the age of 50, then you may need to begin screening earlier. For example, if a mother was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 42, her biological daughter would likely benefit from breast cancer screening beginning at age 32. Talk with your healthcare provider about the best schedule for mammograms.

What are the screening tests for breast cancer?

In addition to mammograms, which are the best screening tests for finding breast cancer in its early stages , other screening tests for breast cancer include breast self-exams and clinical exams. Other forms of imaging studies for screening include ultrasounds and breast MRIs.

Can men get breast cancer?

While it is rare, men do get breast cancer. In 2023, an estimated 2,800 men will be diagnosed with breast cancer, according to the American Cancer Society. Men diagnosed with breast cancer may be encouraged to undergo genetic counseling and genetic testing to see if they carry a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation . The most common gene mutation for men is BRCA2.

What is the risk of radiation from mammograms?

Mammograms require very small doses of radiation, lower than that of a typical x-ray. The total radiation for a typical mammogram is about 0.4 millisieverts—the same amount women are exposed to in their natural environment in about seven weeks. Studies consistently show that the benefits of receiving mammograms outweigh the risks of radiation exposure for most women. However, always let your healthcare provider know if you are pregnant or could be pregnant as radiation exposure risk for pregnant women is higher.

American Cancer Society Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Cancer Institute U.S. Preventative Services Task Force

Related reading:

We use cookies on our website to personalize your experience and improve our efforts. By continuing, you agree to the terms of our Privacy & Cookies Policies.

MUNEEZA KHAN, MD, AND ANNA CHOLLET, MD, MPH

This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(1):33-41

Patient information: See related handout on mammogram screening for breast cancer , written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Breast cancer is the most common nonskin cancer in women and accounts for 30% of all new cancers in the United States. The highest incidence of breast cancer is in women 70 to 74 years of age. Numerous risk factors are associated with the development of breast cancer. A risk assessment tool can be used to determine individual risk and help guide screening decisions. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recommend against teaching average-risk women to perform breast self-examinations. The USPSTF and AAFP recommend biennial screening mammography for average-risk women 50 to 74 years of age. However, there is no strong evidence supporting a net benefit of mammography screening in average-risk women 40 to 49 years of age; therefore, the USPSTF and AAFP recommend individualized decision-making in these women. For average-risk women 75 years and older, the USPSTF and AAFP conclude that there is insufficient evidence to recommend screening, but the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Cancer Society state that screening may continue depending on the woman's health status and life expectancy. Women at high risk of breast cancer may benefit from mammography starting at 30 years of age or earlier, with supplemental screening such as magnetic resonance imaging. Supplemental ultrasonography in women with dense breasts increases cancer detection but also false-positive results.

Breast cancer is the most common nonskin cancer in women and accounts for 30% of all new cancers in the United States. 1 From 2001 to 2016, more than 2.3 million women in the United States were diagnosed with breast cancer. 2 The incidence of breast cancer increases after 25 years of age, peaking between 70 and 74 years. 2 Approximately one in eight women will develop invasive breast cancer (12.8% lifetime risk). 1

WHAT'S NEW ON THIS TOPIC

Breast Cancer Screening

A 2016 meta-analysis calculated that per 10,000 women screened with mammography, three breast cancer deaths are avoided over 10 years in women 40 to 49 years of age, eight deaths are avoided in women 50 to 59 years, 21 deaths are avoided in women 60 to 69 years, and 13 deaths are avoided in women 70 to 74 years. [ corrected ]

One out of every eight women 40 to 49 years of age who has a screening mammogram will subsequently undergo additional imaging, and for every case of invasive breast cancer detected by screening mammography in this age group, 10 women will have had a biopsy.

In a large, multicenter trial, women with dense breasts and a negative standard mammogram result had two-year screening with MRI or standard mammography. The interval cancer rate was lower in the MRI group than in the mammography group; however, MRI had a high false-positive rate with hundreds of negative breast biopsy results among the 4,738 women who underwent MRI screening.

MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

The overall mortality rate in U.S. women with breast cancer is about 20 per 100,000. Mortality rates are highest in women 85 years and older (170 per 100,000). 2 White women have the highest rate of breast cancer diagnosis, whereas Black women have the highest rate of breast cancer–related death. 2 Breast cancer is also the most common cause of cancer-related death in Hispanic women and the second leading cause of cancer-related death behind lung cancer among all women. 2

Cancer screening recommendations are determined by the patient's current anatomy. Transgender females with breast tissue and transgender males who have not undergone complete mastectomy should receive screening mammography based on guidelines for cisgender persons (see https://www.aafp.org/afp/2018/1201/p645.html#sec-4 ).

What Are the Risk Factors for Breast Cancer?

The strongest risk factors are a history of childhood chest radiation, older age, increased breast density, family history of breast cancer, and certain genetic mutations ( Table 1 ). 3 – 16 However, most women who develop invasive breast cancer do not have any of these risk factors . 3

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A retrospective cohort study demonstrated a standardized incidence ratio (i.e., the ratio of observed to expected number of cases) of 21.9 for breast cancer in women who received chest radiation during childhood. 4 Higher doses of radiation were associated with higher risk, and the highest risk was in those who received whole lung radiation (standardized incidence ratio = 43.6). The overall cumulative risk of developing breast cancer by 50 years of age was 30%. 4

Increasing age is another strong risk factor. Invasive breast cancer will be diagnosed in one out of 42 women 50 to 59 years of age, and this rate increases to one out of 14 in women 70 years and older. 5

Breast density is the amount of glandular and stromal tissue compared with adipose tissue shown on a mammogram. A systematic review and meta-analysis found that compared with women who do not have dense breasts, the relative risk of developing breast cancer is 1.79 for women with breast density between 5% and 24% and 4.64 for those with breast density of 75% or higher. 6

Data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium and the Collaborative Breast Cancer Study showed that having a first-degree relative with breast cancer increases a woman's personal risk by a hazard ratio of 1.61 and odds ratio of 1.64. 7 For patients with BRCA mutations, the risk of developing breast cancer by 80 years of age is 60% to 63%, regardless of family history. 8

How Can Physicians Estimate the Risk of Developing Breast Cancer?

Several validated risk assessment tools are available to stratify breast cancer risk ( Table 2 ). 17 These tools can assist physicians and patients in developing individualized plans regarding screening, genetic testing, or chemoprevention .

A large retrospective cohort study compared the six-year accuracy of five validated risk assessment tools among 35,921 women 40 to 84 years of age who underwent screening mammography in the United States from 2007 to 2009. 17 The models were BRCAPRO ( https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/bayesmendel/bayesmendel-r-package ); Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool, or Gail model ( https://bcrisktool.cancer.gov , https://www.mdcalc.com/gail-model-breast-cancer-risk ); Tyrer-Cuzick model, or International Breast Cancer Intervention Study model ( http://www.ems-trials.org/riskevaluator ); Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium model ( https://tools.bcsc-scc.org/BC5yearRisk/calculator.htm ); and Claus model (computer program).

Based on overall performance, the positive predictive values were 2.6% for BRCAPRO and the Tyrer-Cuzick model, 2.9% for the Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool and Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium model, and 3.9% for the Claus model. The negative predictive values were high at 97% or more for all of the models. 17

Does Screening Mammography Reduce Breast Cancer–Related Mortality?

Screening mammography reduces breast cancer–related mortality, with larger reductions as women get older .

Modeling studies estimate that in women 40 to 49 years of age, the number needed to screen (NNS) with annual mammography to prevent one breast cancer death is 746. The NNS decreases to 351 in women 50 to 59 years and to 233 in women 60 to 69 years. The NNS is 377 in women 70 to 79 years of age. 18 However, randomized controlled trials have demonstrated a substantially higher NNS. A meta-analysis performed for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) calculated that per 10,000 women screened with mammography, only three breast cancer deaths are avoided over 10 years in women 40 to 49 years of age, eight deaths are avoided in women 50 to 59 years, 21 deaths are avoided in women 60 to 69 years, and 13 deaths are avoided in women 70 to 74 years. 19 [ corrected ]

Between 2008 and 2017, yearly rates of newly diagnosed breast cancer increased by 0.3%, and rates of breast cancer death fell by 1.5%. 20 This may be partly attributable to early detection of small, curable breast cancers that have a five-year relative survival rate of 98.8% posttreatment. 20 Studies have shown a reduction in the incidence of large tumors, which is also likely because of early detection of smaller tumors by mammography. 21

Lower death rates, however, may also reflect improved treatments. With older treatments, the reduction in mortality after screening mammography was approximately 12 deaths per 100,000 women. With improved treatments, the reduction in mortality after screening mammography is now about eight deaths per 100,000 women. 21

What Are the Potential Harms of Breast Cancer Screening?

False-positive results are common with screening mammography, especially in younger women, leading to further imaging and radiation exposure and subsequent breast biopsies that can be painful, can cause anxiety, and usually yield benign results. Furthermore, screening can lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment of cancers that may never have become symptomatic or life-threatening .

According to the USPSTF, the false-positive rate of mammography is highest in women 40 to 49 years of age at 121 per 1,000 and decreases with age to 69.6 per 1,000 women 70 to 79 years of age. 22 About one of every eight women 40 to 49 years of age who has a screening mammogram will subsequently undergo additional imaging, and for every case of invasive breast cancer detected by screening mammography in this age group, 10 women will have had a biopsy, compared with only three women in their 70s. 22

False-positive results are associated with increased antidepressant and anxiolytic prescriptions, with a relative risk of 1.13 to 1.19. 23 Women at highest risk of needing antidepressant and anxiolytic therapy are those 40 to 49 years of age who underwent multiple tests, including a biopsy, and who had to wait more than one week to be told the results were false-positive. 23

Systematic reviews have found that screening mammography leads to an overdiagnosis rate of 10% to 30%. 24 , 26 [ corrected ] Overdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary treatments for screening-detected breast cancers. Sometimes this involves treating ductal carcinoma in situ that would have been inconsequential over a woman's lifetime. 3 A study based on a large U.S. cancer registry reported that out of 297,000 women 40 years and older who had a mastectomy in 2013, 18% may not have needed one. 25 Thus, the USPSTF concludes that there is no strong evidence supporting mammography screening of average-risk women in their 40s. 26

What Are the Screening Recommendations for Patients at Average Risk?

Recommendations for breast self-examinations, clinical breast examinations, and mammography vary among organizations . Table 3 summarizes recommendations from the USPSTF, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American College of Radiology (ACR), the American Cancer Society (ACS), and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) . 3 , 26 – 33

Breast Self-Examination . The USPSTF and AAFP recommend against teaching patients to perform breast self-examinations because of a lack of supporting evidence. 26 , 27 ACOG, the NCCN, and the ACS encourage breast self-awareness (i.e., patient familiarity with how her breasts usually feel and look) and advise women to seek medical attention if they notice breast changes. 3 , 31 , 33 There may be some rationale for breast self-awareness based on the frequency of self-detection cited in some studies. For example, out of 361 breast cancer survivors who participated in the 2003 National Health Interview Survey, 43% reported detecting their own cancers. 34

Clinical Breast Examination . The USPSTF and AAFP state that there is insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of clinical breast examinations. 26 , 28 The ACS recommends against these examinations because of insufficient evidence of benefit and a high rate of false-positive results (55 false-positives for every breast cancer detected). 31 , 35 For average-risk women 40 years and older, ACOG says that annual clinical breast examinations may be offered, and the NCCN recommends annual clinical breast examinations. 3 , 33

Mammography . Evidence of benefit varies with a woman's age. The USPSTF found lower mortality rates and a reduced risk of advanced breast cancer in women 50 years and older who had mammography screening (relative risk = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.46 to 0.83) but not in women 39 to 49 years of age (relative risk = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.37). 19 The number of breast cancer deaths prevented with screening over 10 years was 12.5 per 10,000 women 50 years and older but only 2.9 per 10,000 women in their 40s. 19 Overall, women 50 to 59 years of age have the best balance of risks and benefits from mammography. 3 , 19

ACS data, however, showed improved mortality benefit across all age groups, although the benefit was lower in younger women. The NNS to reduce mortality rates by 20% was 1,770 for women in their 40s, 1,087 for women in their 50s, and 835 for women in their 60s. 31

The USPSTF recommends biennial screening mammography for women 50 to 74 years of age. 26 This recommendation excludes women 40 to 49 years of age because the number needed to invite (NNI) of 1,904 and the NNS of 1,034 to detect one case of breast cancer with screening mammography were considered too high. The NNI of 1,339 and NNS of 455 in women 50 to 59 years of age and the NNI of 377 and NNS of 233 for women 60 to 69 years of age were considered acceptable. 18 The AAFP supports the USPSTF recommendation. 29

The ACS recommends annual screening mammography starting at 45 years of age and transitioning to biennial screening at 55 years of age. 31 This recommendation is based on multivariable analyses suggesting that women in the younger age group are more likely than older women to have advanced stage cancer when screened biennially rather than annually. 31

The NCCN recommends annual screening mammography. 33 , 36 ACOG recommends shared decision-making based on a discussion of benefits and harms when deciding between annual and biennial screening intervals. 3

At What Age Should Breast Cancer Screening Be Discontinued?

Women at average risk should continue screening mammography through 74 years of age . 3 , 26 , 29 – 31 , 33 Starting at 75 years of age, women should be involved in shared decision-making based on overall health status and life expectancy according to ACOG recommendations . 3 The ACS and NCCN recommend continued screening after 75 years of age if life expectancy is at least 10 years, and the ACR recommends continued screening if life expectancy is at least five to seven years . 30 , 31 , 33 The USPSTF states that there is insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of screening past 74 years of age, and the AAFP supports this finding . 26 , 29

Randomized controlled trials have shown that when mammography screening prevents a death, the death would have occurred within five to seven years after screening; thus, screening women with limited life expectancy is not warranted. 36 In addition, the number of life-years gained from screening decreases from 7.8 to 11.4 per 1,000 mammograms at 74 years of age to 4.8 to 7.8 per 1,000 at 80 years and to 1.4 to 2.4 per 1,000 at 90 years. 37 When adjusted for quality of life, the number of life-years gained decreases even further, and by 90 to 92 years of age, all life-years gained are counter-balanced by a loss in quality of life, presumably because of treatment adverse effects. 37 Yet, despite these data and the corresponding recommendations, 62% of women 75 to 79 years of age and 50% of women 80 years or older get mammograms, and 70% to 86% of physicians recommend mammography for 80-year-old women. 38 , 39

What Are the Screening Recommendations for Patients at Increased Risk?

ACS recommends that women with a 20% or higher lifetime risk of breast cancer (assessed using a risk assessment tool [ Table 2 17 ] ) be offered annual mammography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), typically starting at 30 years of age . 32 For high-risk women 25 to 29 years of age, ACOG recommends a clinical breast examination every six to 12 months and annual breast MRI with contrast. For patients 30 years and older, ACOG recommends annual mammography and MRI with contrast . 40 The NCCN recommends that women with a lifetime risk of more than 20% have breast self-awareness and receive a clinical breast examination every six to 12 months starting at 21 years of age. Annual breast MRI is recommended starting at 25 years of age with annual screening mammography starting at 30 years . 33 Women younger than 25 years with a history of chest radiation should have breast self-awareness and receive a clinical breast examination every six to 12 months starting 10 years after radiation therapy. Once these women are 25 years old, annual breast MRI is recommended, then screening mammography starting at 30 years of age . 33 The USPSTF states that there is insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of using MRI for breast cancer screening, and the AAFP supports this finding . 26 , 29

The evidence for adding annual MRI screening to mammography and clinical breast examinations in women with more than a 20% lifetime risk of breast cancer is based on nonrandomized screening trials and observational studies from the 1990s. 32 These studies showed that MRI has a sensitivity of 71% to 100% for detecting breast cancer in high-risk women vs. mammography's sensitivity of 16% to 40% in the same population. However, MRI is less specific (81% to 99%) compared with mammography (93% to more than 99%), resulting in higher rates of false-positives, subsequent medical appointments, and biopsies, with a positive predictive value of 20% to 40%. No data were collected on survival rates with MRI screening or on the optimal MRI screening interval. 32

Does Supplemental Imaging Have a Role in Evaluating Dense Breasts?

Almost 50% of women 40 to 74 years of age have dense breasts, which is a risk factor for breast cancer and for false-negative results on standard mammography . 41 Ultrasonography, MRI, and digital breast tomosynthesis (also known as 3D mammography) have been proposed as methods to detect breast cancers that might be missed on mammography in women with dense breasts .

The ACR recommends considering ultrasonography in addition to screening mammography based on a randomized multicenter trial showing improved cancer detection rates compared with mammography alone (1.9 vs. 4.2 per 1,000). 30 , 42 Ultrasonography may be particularly useful for women who have a 15% to 20% lifetime risk of breast cancer and dense breasts but no additional risk factors. 43

Data from the Connecticut Experiments showed an additional 2.3 cancers detected per 1,000 women with dense breasts who were screened with ultrasonography in addition to mammography. 43 By the fourth year of the study, the positive predictive value had increased from 7.3% to 20.1%, indicating an improved learning curve for the radiologists regarding which lesions to biopsy. Another study, involving 2,662 women with dense breasts plus one other risk factor for breast cancer, showed that adding ultrasonography to mammography increased the sensitivity of breast cancer detection compared with mammography alone (52% vs. 76%). 42

It is important to note, however, that the increased sensitivity comes at the cost of increasing false-positives. An observational cohort study of 6,081 women with varying risk of breast cancer showed that the false-positive rate was 22.2 per 1,000 screens for mammography alone vs. 52 per 1,000 screens for mammography plus ultrasonography (relative risk = 2.23). 44

MRI has also been studied as a screening option in women with dense breasts. A large multicenter trial randomized women with dense breasts and a negative result on standard mammography to two-year screening with either MRI or standard mammography. 45 The cancer detection rate during the two years was lower in the MRI group than in the mammography group (2.5 vs. 5 per 1,000 screens). More than 90% of MRI-detected cancers, however, were stage 0 or 1, and MRI screening resulted in a high false-positive rate (79.8 per 1,000 screens) with hundreds of negative breast biopsy results among the 4,738 women who underwent MRI screening.

MRI has also been compared with digital breast tomosynthesis. There were higher rates of cancer detection with MRI (11.8 per 1,000 screens) than with digital breast tomosynthesis (4.8 per 1,000 screens), but no data are available on long-term outcomes. 46 A study comparing standard mammography with digital breast tomosynthesis is underway. 47

The long-term survival of women whose breast cancers were detected with supplemental imaging modalities has not been studied.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Tirona , 48 Knutson and Steiner , 49 and Apantaku . 50

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms breast cancer, breast cancer screening, risk factors for breast cancer, breast cancer risk assessment tools, breast cancer screening recommendations, breast density, mammography, supplemental screening. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Healthcare Reports, the Cochrane database, and Essential Evidence Plus. Search date: April 2020.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2020. Accessed April 4, 2020. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and-figures-2020.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. United States cancer statistics: data visualizations. Accessed August 2, 2020. https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/DataViz.html

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 179. Breast cancer risk assessment and screening in average-risk women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):e1-e16.

Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Wolden SL, et al. Breast cancer after chest radiation therapy for childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(21):2217-2223.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7-30.

McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(6):1159-1169.

Shiyanbola OO, Arao RF, Miglioretti DL, et al. Emerging trends in family history of breast cancer and associated risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(12):1753-1760.

Metcalfe KA, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, et al.; Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. The risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers without a first-degree relative with breast cancer. Clin Genet. 2018;93(5):1063-1068.

Chen S, Iversen ES, Friebel T, et al. Characterization of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a large United States sample. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(6):863-871.

American Cancer Society. Breast cancer facts and figures 2019–2020. Accessed August 2, 2020. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2019-2020.pdf

Schacht DV, Yamaguchi K, Lai J, et al. Importance of a personal history of breast cancer as a risk factor for the development of subsequent breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202(2):289-292.

Dyrstad SW, Yan Y, Fowler AM, et al. Breast cancer risk associated with benign breast disease. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149(3):569-575.

Liu Y, Colditz GA, Rosner B, et al. Alcohol intake between menarche and first pregnancy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(20):1571-1578.

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. Lancet. 2019;394(10204):1159-1168.

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(11):1141-1151.

Colditz GA, Rosner B. Cumulative risk of breast cancer to age 70 years according to risk factor status. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(10):950-964.

McCarthy AM, Guan Z, Welch M, et al. Performance of breast cancer risk-assessment models in a large mammography cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(5):489-497.

Hendrick RE, Helvie MA. Mammography screening. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(3):723-728.

Nelson HD, Fu R, Cantor A, et al. Effectiveness of breast cancer screening: systematic review and meta-analysis to update the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):244-255.

National Cancer Institute. Female breast cancer. Accessed August 2, 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html

Welch HG, Prorok PC, O'Malley AJ, et al. Breast-cancer tumor size, overdiagnosis, and mammography screening effectiveness. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1438-1447.

Nelson HD, O'Meara ES, Kerlikowske K, et al. Factors associated with rates of false-positive and false-negative results from digital mammography screening. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):226-235.

Segel JE, Balkrishnan R, Hirth RA. The effect of false-positive mammograms on antidepressant and anxiolytic initiation. Med Care. 2017;55(8):752-758.

Monticciolo DL, Helvie MA, Hendrick RE. Current issues in the overdiagnosis and overtreatment of breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;210(2):285-291.

Harding C, Pompei F, Burmistrov D, et al. Use of mastectomy for overdiagnosed breast cancer in the United States. J Cancer Epidemiol. ;2019:5072506.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Breast cancer: screening. January 11, 2016. Accessed July 20, 2019. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/breast-cancer-screening

American Academy of Family Physicians. Breast cancer, breast self exam (BSE). Accessed July 20, 2019. https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/breast-cancer-self-bse.html

American Academy of Family Physicians. Breast cancer, clinical breast examination (CBE). Accessed July 20, 2019. https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/breast-cancer-cbe.html

American Academy of Family Physicians. Breast cancer. Accessed May 31, 2020. https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/breast-cancer.html

Lee CH, Dershaw DD, Kopans D, et al. Breast cancer screening with imaging: recommendations from the Society of Breast Imaging and the ACR on the use of mammography, breast MRI, breast ultrasound, and other technologies for the detection of clinically occult breast cancer. J Am Coll Radiol. 2010;7(1):18-27.

Oeffinger KC, Fontham ETH, Etzioni R, et al.; American Cancer Society. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk [published correction appears in JAMA . 2016;315(13):1406]. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599-1614.

Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography [published correction appears in CA Cancer J Clin . 2007;57(3):185]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(2):75-89.

Bevers TB, Helvie M, Bonaccio E, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis. Version 3.2019. May 17, 2019. Accessed May 31, 2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf

Roth MY, Elmore JG, Yi-Frazier JP, et al. Self-detection remains a key method of breast cancer detection for U.S. women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011;20(8):1135-1139.

Meyers ER, Moorman P, Gierisch JM, et al. Benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: a systematic review [published correction appears in JAMA . 2016;315(13):1406]. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1615-1634.

Helvie MA, Bevers TB. Screening mammography for average-risk women. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(11):1398-1404.

van Ravesteyn NT, Stout NK, Schechter CB, et al. Benefits and harms of mammography screening after age 74 years. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(7):djv103.

Bellizzi KM, Breslau ES, Burness A, et al. Prevalence of cancer screening in older, racially diverse adults. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(22):2031-2037.

Leach CR, Klabunde CN, Alfano CM, et al. Physician over-recommendation of mammography for terminally ill women. Cancer. 2012;118(1):27-37.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Practice bulletin no. 182. September 2017. Accessed August 2, 2020. https://bit.ly/37Kl2M4

Sprague BL, Gangnon RE, Burt V, et al. Prevalence of mammographically dense breasts in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(10):dju255.

Berg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D, et al.; ACRIN 6666 Investigators. Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2012;307(13):1394-1404.

Thigpen D, Kappler A, Brem R. The role of ultrasound in screening dense breasts. Diagnostics (Basel). 2018;8(1):20.

Lee JM, Arao RF, Sprague BL, et al. Performance of screening ultrasonography as an adjunct to screening mammography in women across the spectrum of breast cancer risk [published correction appears in JAMA Intern Med . 2019;179(5):733]. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(5):658-667.

Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al.; DENSE Trial Study Group. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(22):2091-2102.

Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening [published correction appears in JAMA . 2020;323(12):1194]. JAMA. 2020;323(8):746-756.

National Cancer Institute. TMIST (Tomosynthesis Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial). Accessed January 10, 2020. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials/nci-supported/tmist

Tirona MT. Breast cancer screening update. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87(4):274-278. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2013/0215/p274.html

Knutson D, Steiner E. Screening for breast cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(11):1660-1666. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2007/0601/p1660.html

Apantaku LM. Breast cancer diagnosis and screening. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62(3):596-602. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://aafp.org/afp/2000/0801/p596.html

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2021 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Bioethics in Medicine and Society

Ethical Concerns Regarding Breast Cancer Screening

Submitted: 04 June 2020 Reviewed: 23 September 2020 Published: 13 October 2020

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.94159

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Bioethics in Medicine and Society

Edited by Thomas F. Heston and Sujoy Ray

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

749 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

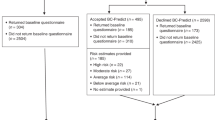

The incidence and mortality of breast cancer are rising in the whole world in the past few decades, adding up to a total of around two million new cases and 620,000 deaths in 2018. Unlike what occurs in developed countries, most of the cases diagnosed in the developing world are already in advanced stages and also in women younger than 50 years old. As most screening programs suggest annual mammograms starting at the age of 50, we can infer that a considerable portion of the new breast cancer cases is missed with this strategy. Here, we will propose the adoption of an alternative hierarchical patient flow, with the creation of a diagnostic fast track with referral to timely treatment, promoting better resources reallocation favoring the least advantaged strata of the population, which is not only ethically acceptable but also a way of promoting social justice.

- breast cancer

- public health

Author Information

Rodrigo goncalves *.

- Breast Surgery Sector, Discipline of Gynecology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hospital das Clinicas of the University of Sao Paulo Medical School, Brazil

Maria Carolina Formigoni

José maria soares.

- Discipline of Gynecology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hospital das Clinicas of the University of Sao Paulo Medical School, Brazil

Edmund Chada Baracat

José roberto filassi.

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction