Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Inductive vs. Deductive Research Approach | Steps & Examples

Inductive vs. Deductive Research Approach | Steps & Examples

Published on April 18, 2019 by Raimo Streefkerk . Revised on June 22, 2023.

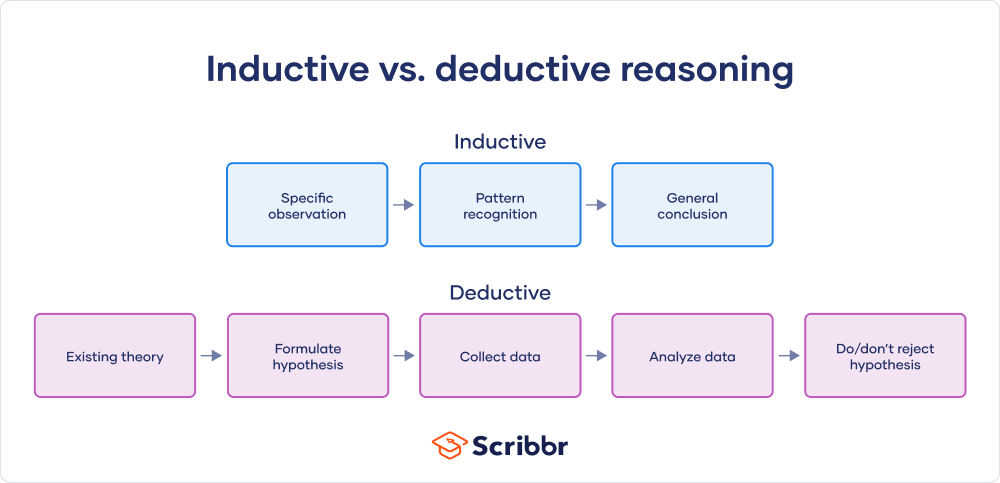

The main difference between inductive and deductive reasoning is that inductive reasoning aims at developing a theory while deductive reasoning aims at testing an existing theory .

In other words, inductive reasoning moves from specific observations to broad generalizations . Deductive reasoning works the other way around.

Both approaches are used in various types of research , and it’s not uncommon to combine them in your work.

Table of contents

Inductive research approach, deductive research approach, combining inductive and deductive research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about inductive vs deductive reasoning.

When there is little to no existing literature on a topic, it is common to perform inductive research , because there is no theory to test. The inductive approach consists of three stages:

- A low-cost airline flight is delayed

- Dogs A and B have fleas

- Elephants depend on water to exist

- Another 20 flights from low-cost airlines are delayed

- All observed dogs have fleas

- All observed animals depend on water to exist

- Low cost airlines always have delays

- All dogs have fleas

- All biological life depends on water to exist

Limitations of an inductive approach

A conclusion drawn on the basis of an inductive method can never be fully proven. However, it can be invalidated.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

When conducting deductive research , you always start with a theory. This is usually the result of inductive research. Reasoning deductively means testing these theories. Remember that if there is no theory yet, you cannot conduct deductive research.

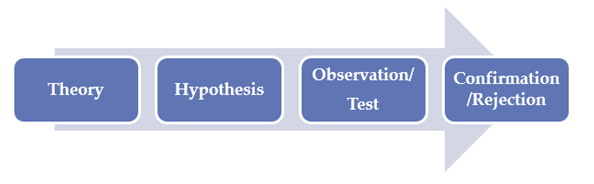

The deductive research approach consists of four stages:

- If passengers fly with a low cost airline, then they will always experience delays

- All pet dogs in my apartment building have fleas

- All land mammals depend on water to exist

- Collect flight data of low-cost airlines

- Test all dogs in the building for fleas

- Study all land mammal species to see if they depend on water

- 5 out of 100 flights of low-cost airlines are not delayed

- 10 out of 20 dogs didn’t have fleas

- All land mammal species depend on water

- 5 out of 100 flights of low-cost airlines are not delayed = reject hypothesis

- 10 out of 20 dogs didn’t have fleas = reject hypothesis

- All land mammal species depend on water = support hypothesis

Limitations of a deductive approach

The conclusions of deductive reasoning can only be true if all the premises set in the inductive study are true and the terms are clear.

- All dogs have fleas (premise)

- Benno is a dog (premise)

- Benno has fleas (conclusion)

Many scientists conducting a larger research project begin with an inductive study. This helps them develop a relevant research topic and construct a strong working theory. The inductive study is followed up with deductive research to confirm or invalidate the conclusion. This can help you formulate a more structured project, and better mitigate the risk of research bias creeping into your work.

Remember that both inductive and deductive approaches are at risk for research biases, particularly confirmation bias and cognitive bias , so it’s important to be aware while you conduct your research.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Inductive reasoning is a bottom-up approach, while deductive reasoning is top-down.

Inductive reasoning takes you from the specific to the general, while in deductive reasoning, you make inferences by going from general premises to specific conclusions.

Inductive reasoning is a method of drawing conclusions by going from the specific to the general. It’s usually contrasted with deductive reasoning, where you proceed from general information to specific conclusions.

Inductive reasoning is also called inductive logic or bottom-up reasoning.

Deductive reasoning is a logical approach where you progress from general ideas to specific conclusions. It’s often contrasted with inductive reasoning , where you start with specific observations and form general conclusions.

Deductive reasoning is also called deductive logic.

Exploratory research aims to explore the main aspects of an under-researched problem, while explanatory research aims to explain the causes and consequences of a well-defined problem.

Explanatory research is used to investigate how or why a phenomenon occurs. Therefore, this type of research is often one of the first stages in the research process , serving as a jumping-off point for future research.

Exploratory research is often used when the issue you’re studying is new or when the data collection process is challenging for some reason.

You can use exploratory research if you have a general idea or a specific question that you want to study but there is no preexisting knowledge or paradigm with which to study it.

A research project is an academic, scientific, or professional undertaking to answer a research question . Research projects can take many forms, such as qualitative or quantitative , descriptive , longitudinal , experimental , or correlational . What kind of research approach you choose will depend on your topic.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Streefkerk, R. (2023, June 22). Inductive vs. Deductive Research Approach | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/inductive-deductive-reasoning/

Is this article helpful?

Raimo Streefkerk

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, explanatory research | definition, guide, & examples, exploratory research | definition, guide, & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Analyzing and Interpreting Qualitative Research After the Interview

- Charles Vanover - University of South Florida, USA

- Paul Mihas - The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA

- Johnny Saldana - Arizona State University, USA

- Description

This text provides comprehensive coverage of the key methods for analyzing, interpreting, and writing up qualitative research in a single volume, and drawing on the expertise of major names in the field. Covering all the steps in the process of analyzing, interpreting, and presenting findings in qualitative research, the authors utilize a consistent chapter structure that provides novice and seasoned researchers with pragmatic, “how-to” strategies. Each chapter introduces the method; uses one of the authors' own research projects as a case study of the method described; shows how the specific analytic method can be used in other types of studies; and concludes with questions and activities to prompt class discussion or personal study.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

This book is a great addition to the library of qualitative books for use with graduate students. Each chapter has examples to use and offers the nuance and complexities that are inherent in qualitative inquiry.

As an instructor of qualitative research courses, I know this text will be immediately useful for my students. Each chapter calls to mind a student who could benefit from its contents. The whole book is written in a way that’s accessible and down-to-earth and it will appeal to graduate students especially; I’ve picked up some new techniques, as well.

A complete guide for qualitative researchers – emerging or experienced. New ways to think about the vital role of qualitative studies!

The chapter authors provide clear, practical, and vibrant examples of their strategies. Individually, each chapter gives care to how the authors have used the strategy in the past. Collectively, the chapters provide a wealth of unique and innovative analysis approaches for all qualitative researchers to consider.

Change of focus in course design.

This was a great supplemental text to use in the Qualitative Research foundations course. This supplemented the main text by providing great detail about the "after" of the interview. Many of my students faced challenges in the coding and analyzing, especially during covid, and virtual interviews, so this was a great almost manual for them to have.

Sample Materials & Chapters

Introduction

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

107: Deductive Qualitative Analysis: Evaluating, Expanding, and Refining Theory

Stephen Fife; Jacob Gossner; Nathalie Saltikoff

About the Session

Theory Construction and Research Methodology Methods (TCRM) Workshop 2

Authors: Stephen Fife, Jacob Gossner

Presider: Nathalie Saltikoff

Summary The advancement of Family Science requires the examination of current theories and the re-examination of previously published findings, whether quantitative or qualitative. Until recently, qualitative researchers have lacked a systematic way to combine inductive and deductive analysis in exploring the applicability of previous findings and existing theory to new samples. Deductive qualitative analysis (DQA) is a qualitative methodology suited to theory testing and refinement that combines deduction and induction to examine evidence that supports, contradicts, expands, or refines theory. We explore two applications of this methodology and offer suggestions for maintaining rigor and trustworthiness of analysis.

Family Science is a vibrant and growing discipline. Visit Family.Science to learn more and see how Family Scientists make a difference.

NCFR is a nonpartisan, 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization whose members support all families through research, teaching, practice, and advocacy.

Get the latest updates on NCFR & Family Science in our weekly email newsletter:

Connect with Us

National Council on Family Relations 661 LaSalle Street, Suite 200 Saint Paul, MN 55114 Phone: (888) 781-9331 [email protected] Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

© Copyright 2023 NCFR

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.3: Inductive or Deductive? Two Different Approaches

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 12547

Learning Objectives

- Describe the inductive approach to research, and provide examples of inductive research.

- Describe the deductive approach to research, and provide examples of deductive research.

- Describe the ways that inductive and deductive approaches may be complementary.

Theories structure and inform sociological research. So, too, does research structure and inform theory. The reciprocal relationship between theory and research often becomes evident to students new to these topics when they consider the relationships between theory and research in inductive and deductive approaches to research. In both cases, theory is crucial. But the relationship between theory and research differs for each approach. Inductive and deductive approaches to research are quite different, but they can also be complementary. Let’s start by looking at each one and how they differ from one another. Then we’ll move on to thinking about how they complement one another.

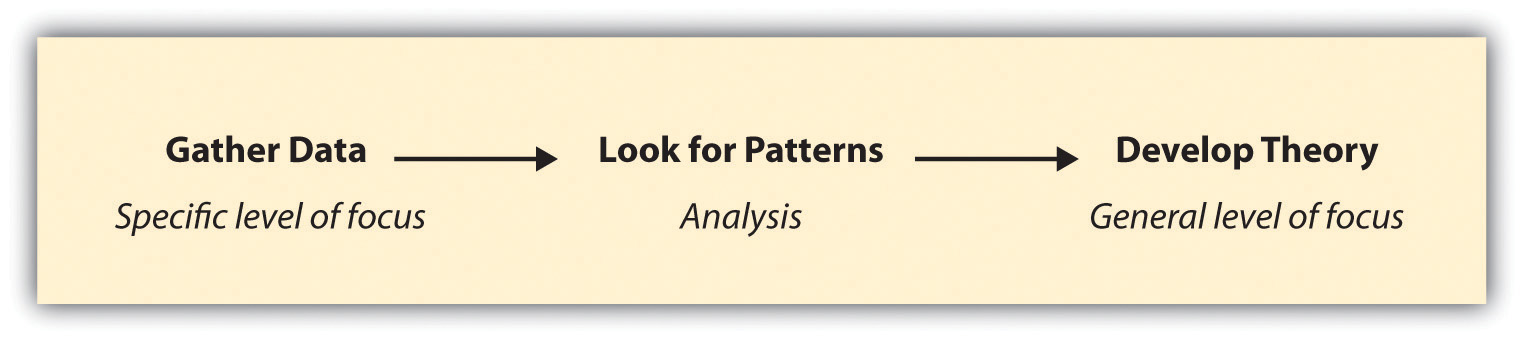

Inductive Approaches and Some Examples

In an inductive approach to research, a researcher begins by collecting data that is relevant to his or her topic of interest. Once a substantial amount of data have been collected, the researcher will then take a breather from data collection, stepping back to get a bird’s eye view of her data. At this stage, the researcher looks for patterns in the data, working to develop a theory that could explain those patterns. Thus when researchers take an inductive approach, they start with a set of observations and then they move from those particular experiences to a more general set of propositions about those experiences. In other words, they move from data to theory, or from the specific to the general. Figure 2.5 outlines the steps involved with an inductive approach to research.

Figure 2.5 Inductive Research

There are many good examples of inductive research, but we’ll look at just a few here. One fascinating recent study in which the researchers took an inductive approach was Katherine Allen, Christine Kaestle, and Abbie Goldberg’s study (2011)Allen, K. R., Kaestle, C. E., & Goldberg, A. E. (2011). More than just a punctuation mark: How boys and young men learn about menstruation. Journal of Family Issues, 32 , 129–156. of how boys and young men learn about menstruation. To understand this process, Allen and her colleagues analyzed the written narratives of 23 young men in which the men described how they learned about menstruation, what they thought of it when they first learned about it, and what they think of it now. By looking for patterns across all 23 men’s narratives, the researchers were able to develop a general theory of how boys and young men learn about this aspect of girls’ and women’s biology. They conclude that sisters play an important role in boys’ early understanding of menstruation, that menstruation makes boys feel somewhat separated from girls, and that as they enter young adulthood and form romantic relationships, young men develop more mature attitudes about menstruation.

In another inductive study, Kristin Ferguson and colleagues (Ferguson, Kim, & McCoy, 2011)Ferguson, K. M., Kim, M. A., & McCoy, S. (2011). Enhancing empowerment and leadership among homeless youth in agency and community settings: A grounded theory approach. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 28 , 1–22. analyzed empirical data to better understand how best to meet the needs of young people who are homeless. The authors analyzed data from focus groups with 20 young people at a homeless shelter. From these data they developed a set of recommendations for those interested in applied interventions that serve homeless youth. The researchers also developed hypotheses for people who might wish to conduct further investigation of the topic. Though Ferguson and her colleagues did not test the hypotheses that they developed from their analysis, their study ends where most deductive investigations begin: with a set of testable hypotheses.

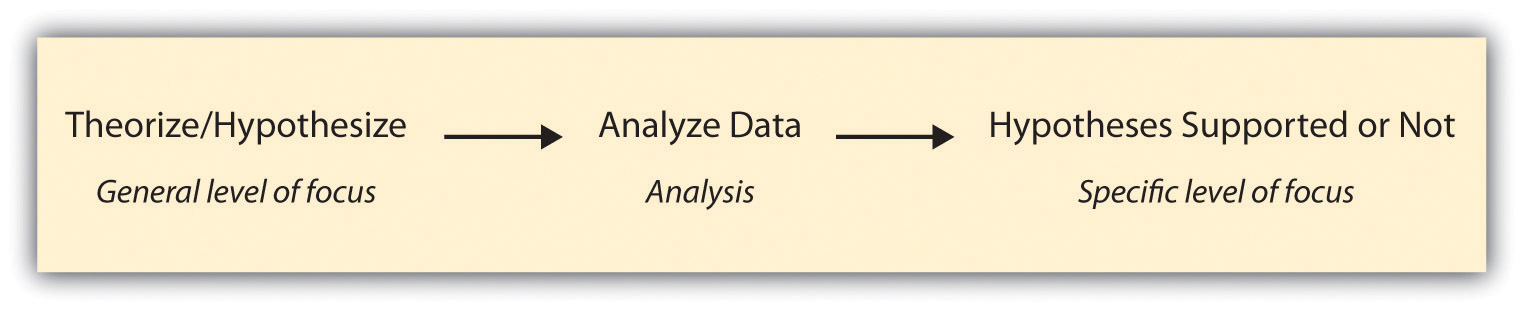

Deductive Approaches and Some Examples

Researchers taking a deductive approach take the steps described earlier for inductive research and reverse their order. They start with a social theory that they find compelling and then test its implications with data. That is, they move from a more general level to a more specific one. A deductive approach to research is the one that people typically associate with scientific investigation. The researcher studies what others have done, reads existing theories of whatever phenomenon he or she is studying, and then tests hypotheses that emerge from those theories. Figure 2.6 outlines the steps involved with a deductive approach to research.

Figure 2.6 Deductive Research

While not all researchers follow a deductive approach, as you have seen in the preceding discussion, many do, and there are a number of excellent recent examples of deductive research. We’ll take a look at a couple of those next.

In a study of US law enforcement responses to hate crimes, Ryan King and colleagues (King, Messner, & Baller, 2009)King, R. D., Messner, S. F., & Baller, R. D. (2009). Contemporary hate crimes, law enforcement, and the legacy of racial violence. American Sociological Review, 74 , 291–315.hypothesized that law enforcement’s response would be less vigorous in areas of the country that had a stronger history of racial violence. The authors developed their hypothesis from their reading of prior research and theories on the topic. Next, they tested the hypothesis by analyzing data on states’ lynching histories and hate crime responses. Overall, the authors found support for their hypothesis.

In another recent deductive study, Melissa Milkie and Catharine Warner (2011)Milkie, M. A., & Warner, C. H. (2011). Classroom learning environments and the mental health of first grade children. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52 , 4–22. studied the effects of different classroom environments on first graders’ mental health. Based on prior research and theory, Milkie and Warner hypothesized that negative classroom features, such as a lack of basic supplies and even heat, would be associated with emotional and behavioral problems in children. The researchers found support for their hypothesis, demonstrating that policymakers should probably be paying more attention to the mental health outcomes of children’s school experiences, just as they track academic outcomes (American Sociological Association, 2011).The American Sociological Association wrote a press release on Milkie and Warner’s findings: American Sociological Association. (2011). Study: Negative classroom environment adversely affects children’s mental health. Retrieved from asanet.org/press/Negative_Cla...tal_Health.cfm

Complementary Approaches?

While inductive and deductive approaches to research seem quite different, they can actually be rather complementary. In some cases, researchers will plan for their research to include multiple components, one inductive and the other deductive. In other cases, a researcher might begin a study with the plan to only conduct either inductive or deductive research, but then he or she discovers along the way that the other approach is needed to help illuminate findings. Here is an example of each such case.

In the case of my collaborative research on sexual harassment, we began the study knowing that we would like to take both a deductive and an inductive approach in our work. We therefore administered a quantitative survey, the responses to which we could analyze in order to test hypotheses, and also conducted qualitative interviews with a number of the survey participants. The survey data were well suited to a deductive approach; we could analyze those data to test hypotheses that were generated based on theories of harassment. The interview data were well suited to an inductive approach; we looked for patterns across the interviews and then tried to make sense of those patterns by theorizing about them.

For one paper (Uggen & Blackstone, 2004),Uggen, C., & Blackstone, A. (2004). Sexual harassment as a gendered expression of power. American Sociological Review, 69 , 64–92. we began with a prominent feminist theory of the sexual harassment of adult women and developed a set of hypotheses outlining how we expected the theory to apply in the case of younger women’s and men’s harassment experiences. We then tested our hypotheses by analyzing the survey data. In general, we found support for the theory that posited that the current gender system, in which heteronormative men wield the most power in the workplace, explained workplace sexual harassment—not just of adult women but of younger women and men as well. In a more recent paper (Blackstone, Houle, & Uggen, 2006),Blackstone, A., Houle, J., & Uggen, C. “At the time I thought it was great”: Age, experience, and workers’ perceptions of sexual harassment. Presented at the 2006 meetings of the American Sociological Association. Currently under review. we did not hypothesize about what we might find but instead inductively analyzed the interview data, looking for patterns that might tell us something about how or whether workers’ perceptions of harassment change as they age and gain workplace experience. From this analysis, we determined that workers’ perceptions of harassment did indeed shift as they gained experience and that their later definitions of harassment were more stringent than those they held during adolescence. Overall, our desire to understand young workers’ harassment experiences fully—in terms of their objective workplace experiences, their perceptions of those experiences, and their stories of their experiences—led us to adopt both deductive and inductive approaches in the work.

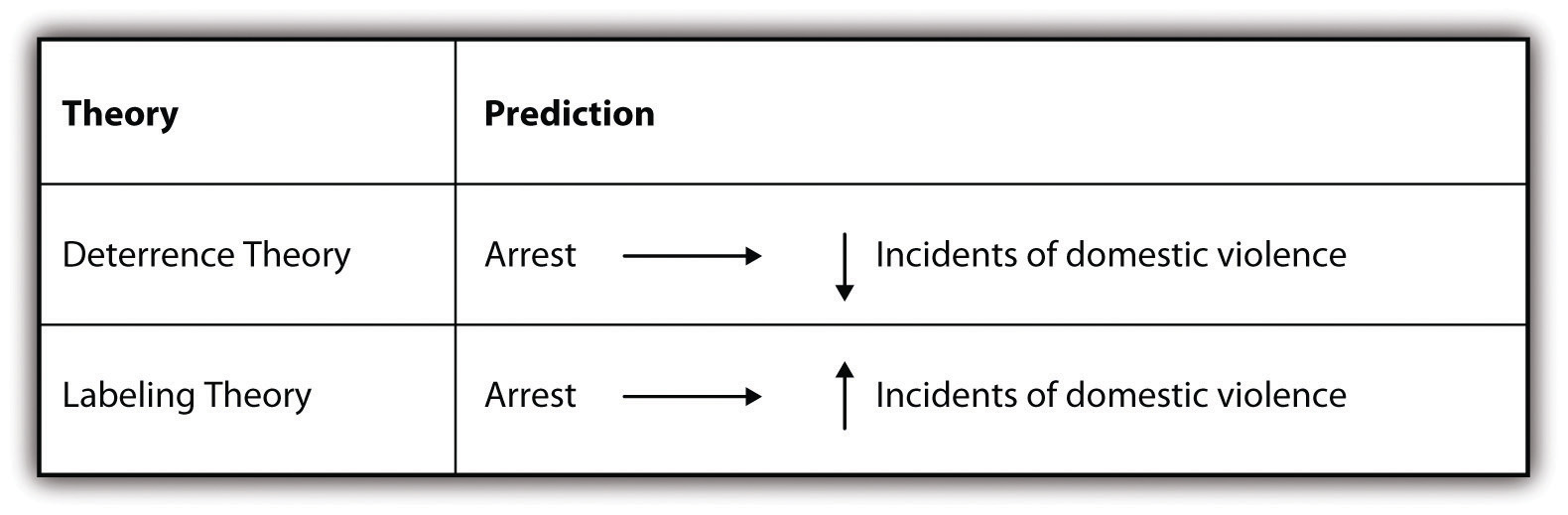

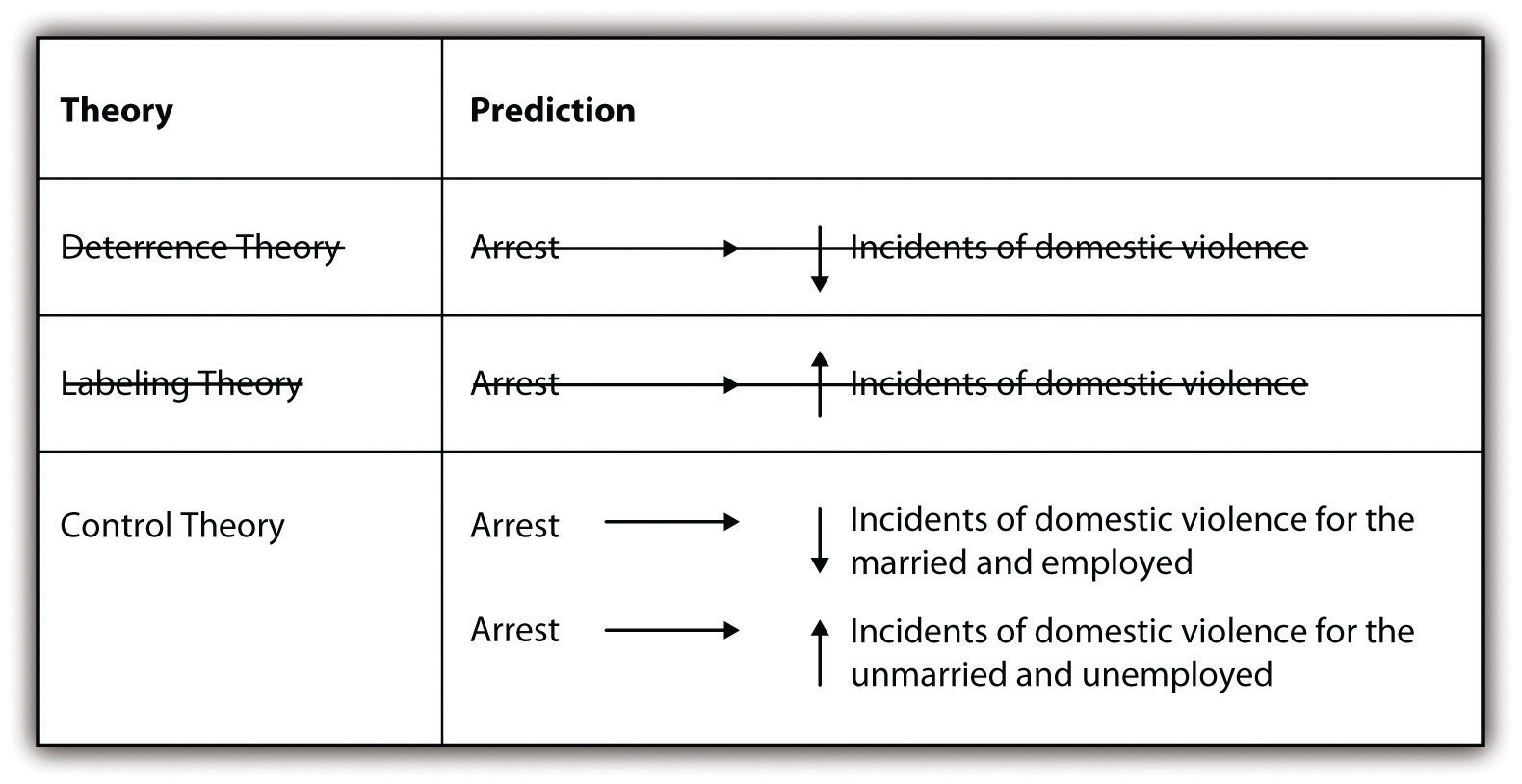

Researchers may not always set out to employ both approaches in their work but sometimes find that their use of one approach leads them to the other. One such example is described eloquently in Russell Schutt’s Investigating the Social World (2006).Schutt, R. K. (2006). Investigating the social world: The process and practice of research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. As Schutt describes, researchers Lawrence Sherman and Richard Berk (1984)Sherman, L. W., & Berk, R. A. (1984). The specific deterrent effects of arrest for domestic assault. American Sociological Review, 49 , 261–272. conducted an experiment to test two competing theories of the effects of punishment on deterring deviance (in this case, domestic violence). Specifically, Sherman and Berk hypothesized that deterrence theory would provide a better explanation of the effects of arresting accused batterers than labeling theory . Deterrence theory predicts that arresting an accused spouse batterer will reduce future incidents of violence. Conversely, labeling theory predicts that arresting accused spouse batterers will increase future incidents. Figure 2.7 summarizes the two competing theories and the predictions that Sherman and Berk set out to test.

Figure 2.7 Predicting the Effects of Arrest on Future Spouse Battery

Sherman and Berk found, after conducting an experiment with the help of local police in one city, that arrest did in fact deter future incidents of violence, thus supporting their hypothesis that deterrence theory would better predict the effect of arrest. After conducting this research, they and other researchers went on to conduct similar experimentsThe researchers did what’s called replication. We’ll learn more about replication in Chapter 3. in six additional cities (Berk, Campbell, Klap, & Western, 1992; Pate & Hamilton, 1992; Sherman & Smith, 1992).Berk, R., Campbell, A., Klap, R., & Western, B. (1992). The deterrent effect of arrest in incidents of domestic violence: A Bayesian analysis of four field experiments. American Sociological Review, 57 , 698–708; Pate, A., & Hamilton, E. (1992). Formal and informal deterrents to domestic violence: The Dade county spouse assault experiment. American Sociological Review, 57 , 691–697; Sherman, L., & Smith, D. (1992). Crime, punishment, and stake in conformity: Legal and informal control of domestic violence. American Sociological Review, 57 , 680–690. Results from these follow-up studies were mixed. In some cases, arrest deterred future incidents of violence. In other cases, it did not. This left the researchers with new data that they needed to explain. The researchers therefore took an inductive approach in an effort to make sense of their latest empirical observations. The new studies revealed that arrest seemed to have a deterrent effect for those who were married and employed but that it led to increased offenses for those who were unmarried and unemployed. Researchers thus turned to control theory, which predicts that having some stake in conformity through the social ties provided by marriage and employment, as the better explanation.

Figure 2.8 Predicting the Effects of Arrest on Future Spouse Battery: A New Theory

What the Sherman and Berk research, along with the follow-up studies, shows us is that we might start with a deductive approach to research, but then, if confronted by new data that we must make sense of, we may move to an inductive approach. Russell Schutt depicts this process quite nicely in his text, and I’ve adapted his depiction here, in Figure 2.9.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The inductive approach involves beginning with a set of empirical observations, seeking patterns in those observations, and then theorizing about those patterns.

- The deductive approach involves beginning with a theory, developing hypotheses from that theory, and then collecting and analyzing data to test those hypotheses.

- Inductive and deductive approaches to research can be employed together for a more complete understanding of the topic that a researcher is studying.

- Though researchers don’t always set out to use both inductive and deductive strategies in their work, they sometimes find that new questions arise in the course of an investigation that can best be answered by employing both approaches.

Monty Python and Holy Grail :

(click to see video)

Do the townspeople take an inductive or deductive approach to determine whether the woman in question is a witch? What are some of the different sources of knowledge (recall Chapter 1) they rely on?

- Think about how you could approach a study of the relationship between gender and driving over the speed limit. How could you learn about this relationship using an inductive approach? What would a study of the same relationship look like if examined using a deductive approach? Try the same thing with any topic of your choice. How might you study the topic inductively? Deductively?

No internet connection.

All search filters on the page have been cleared., your search has been saved..

- All content

- Dictionaries

- Encyclopedias

- Expert Insights

- Foundations

- How-to Guides

- Journal Articles

- Little Blue Books

- Little Green Books

- Project Planner

- Tools Directory

- Sign in to my profile My Profile

- Sign in Signed in

- My profile My Profile

- Offline Playback link

Have you created a personal profile? sign in or create a profile so that you can create alerts, save clips, playlists and searches.

Inductive and Deductive Approaches

- Watching now: Chapter 1: Overview of Inductive and Deductive Approaches in Qualitative Research Start time: 00:00:00 End time: 00:04:37

Video Type: Tutorial

(2018). Inductive and deductive approaches [Video]. Sage Research Methods. https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781529625271

"Inductive and Deductive Approaches." In Sage Video . : Scholarsight Technologies Private Limited, 2018. Video, 00:04:37. https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781529625271.

, 2018. Inductive and Deductive Approaches , Sage Video. [Streaming Video] London: Sage Publications Ltd. Available at: <https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781529625271 & gt; [Accessed 2 Apr 2024].

Inductive and Deductive Approaches . Online video clip. SAGE Video. London: SAGE Publications, Ltd., 2 Dec 2022. doi: https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781529625271. 2 Apr 2024.

Inductive and Deductive Approaches [Streaming video]. 2018. doi:10.4135/9781529625271. Accessed 04/02/2024

Please log in from an authenticated institution or log into your member profile to access the email feature.

- Sign in/register

Add this content to your learning management system or webpage by copying the code below into the HTML editor on the page. Look for the words HTML or </>. Learn More about Embedding Video icon link (opens in new window)

Sample View:

- Download PDF opens in new window

- icon/tools/download-video icon/tools/video-downloaded Download video Downloading... Video downloaded

An overview of inductive and deductive approaches in qualitative research, including examples.

Chapter 1: Overview of Inductive and Deductive Approaches in Qualitative Research

- Start time: 00:00:00

- End time: 00:04:37

- Product: Sage Research Methods Video: Qualitative and Mixed Methods

- Type of Content: Tutorial

- Title: Inductive and Deductive Approaches

- Publisher: Scholarsight Technologies Private Limited

- Series: Theoretical Foundations of Qualitative Research

- Publication year: 2018

- Online pub date: December 02, 2022

- Discipline: Sociology , Communication and Media Studies , History , Public Health , Criminology and Criminal Justice , Counseling and Psychotherapy , Psychology , Health , Education , Social Policy and Public Policy , Social Work , Political Science and International Relations , Geography , Business and Management , Anthropology , Nursing

- Methods: Qualitative measures , Induction , Deduction

- Duration: 00:04:37

- DOI: https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781529625271

- Keywords: deductive reasoning , inductive reasoning , qualitative research methods Show all Show less

- Online ISBN: 9781529625271 Copyright: © Scholarsight Technologies Private Limited. MAXQDA software is the registered trademark of VERBE Gmbh. Any other brand mentioned in examples belong to respective owners. Examples are for demonstration and learning purposes only. More information Less information

Sign in to access this content

Get a 30 day free trial, more like this, sage recommends.

We found other relevant content for you on other Sage platforms.

Have you created a personal profile? Login or create a profile so that you can save clips, playlists and searches

Navigating away from this page will delete your results

Please save your results to "My Self-Assessments" in your profile before navigating away from this page.

Sign in to my profile

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources have to offer.

You must have a valid academic email address to sign up.

Get off-campus access

- View or download all content my institution has access to.

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Research Methods has to offer.

- view my profile

- view my lists

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1-2 The Nature of Evidence: Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

Renate Kahlke; Jonathan Sherbino; and Sandra Monteiro

Different philosophies of science (Chapter 1-1) inform different approaches to research, characterized by different goals, assumptions, and types of data. In this chapter, we discuss how post-positivist, interpretivist, constructivist, and critical philosophies form a foundation for two broad approaches to generating knowledge: quantitative and qualitative research. There are several often-discussed distinctions between these two approaches, stemming from their philosophical roots, specifically, a commitment to objectivity versus subjective interpretation, numbers versus words, generalizability versus transferability, and deductive versus inductive reasoning. While these distinctions often distinguish qualitative and quantitative research, there are always exceptions. These exceptions demonstrate that quantitative and qualitative research approaches have more in common than what superficial descriptions imply.

Key Points of the Chapter

By the end of this chapter the learner should be able to:

- Describe quantitative research methodologies

- Describe qualitative research methodologies

- Compare and contrast these two approaches to interpreting data

Rayna (they/their) stared at the blinking cursor on her screen. They had been recently invited to revise and resubmit their first qualitative research manuscript. Most of the editor and reviewer comments had been relatively easy to handle, but when Rayna reached Reviewer 2’s comments, they were caught off guard. The reviewer acknowledged that they came from a quantitative background, but then went on to write: “I am worried about the generalizability of this study, with a sample of only 25 residents. Wouldn’t it be better to do a survey to get more perspectives?”

Rayna hadn’t seen any other qualitative studies talk about generalizability, so they weren’t entirely sure how to address this comment. Maybe the study won’t be valuable if the results aren’t generalizable! Reviewer 2 might be right that the sample size is too small! They immediately panic-email one of their co-authors:

Hi Rayna, We get these kinds of reviews all the time. Don’t worry, it’s not a flaw in your study. That said, I think we can build our field’s knowledge about qualitative research approaches by explaining some of these concepts. Start with the one by Monteiro et al. and then read the one by Wright and colleagues. These are both good primers and will give you some language to help respond to this reviewer.

With a sigh of relief, Rayna reads through the attached papers (1-8) and continues her mission to craft a response.

Deeper Dive on this Concept

Qualitative and quantitative research are often talked about as two different ways of thinking and generating knowledge. We contrast a reliance on words with a reliance on numbers, a focus on subjectivity with a focus on objectivity. And to some extent these approaches are different, in precisely the ways described. However, many experienced researchers on both sides of the line will tell you that these differences only go so far.

Drawing on Chapter 1-1, there are different philosophies of science that inform researchers and their research products. Generally, quantitative research is associated with post-positivism; researchers seek to be objective and reduce their bias in order to ensure that their results are as close as possible to the truth. Post-positivists, unlike positivists, acknowledge that a singular truth is impossible to define. However, truth can be defined within a spectrum of probability. Quantitative researchers generate and test hypotheses to make conclusions about a theory they have developed. They conduct experiments that generate numerical data that define the extent to which an observation is “true.” The strength of the numerical data suggests whether the observation can be generalized beyond the study population. This process is called deductive reasoning because it starts with a general theory that narrows to a hypothesis that is tested against observations that support (or refute) the theory.

Qualitative researchers, on the other hand, tend to be guided by interpretivism, constructivism, critical theory or other perspectives that value subjectivity. These analytic approaches do not address bias because bias assumes a misrepresentation of “truth” during collection or analysis of data. Subjectivity emphasizes the position and perspective assumed during analysis, articulating that there is no external objective truth, uninformed by context. ( See Chapter 1-1 .) Qualitative methods seek to deeply understand a phenomenon, using the rich meaning provided by words, symbols, traditions, structures, identity constructs and power dynamics (as opposed to simply numbers). Rather than testing a hypothesis, they generate knowledge by inductively generating new insights or theory (i.e. observations are collected and analyzed to build a theory). These insights are contextual, not universal. Qualitative researchers translate their results within a rich description of context so that readers can assess the similarities and differences between contexts and determine the extent to which the study results are transferable to their setting.

While these distinctions can be helpful in distinguishing quantitative and qualitative research broadly, they also create false divisions. The relationships between these two approaches are more complex, and nuances are important to bear in mind, even for novices, lest we exacerbate hierarchies and divisions between different types of knowledge and evidence.

As an example, the interpretation of quantitative results is not always clear and obvious – findings do not always support or refute a hypothesis. Thus, both qualitative and quantitative researchers need to be attentive to their data. While quantitative research is generally thought to be deductive, quantitative researchers often do a bit of inductive reasoning to find meaning in data that hold surprises. Conversely, qualitative data are stereotypically analyzed inductively, making meaning from the data rather than proving a hypothesis. However, many qualitative researchers apply existing theories or theoretical frameworks, testing the relevance of existing theory in a new context or seeking to explain their data using an existing framework. These approaches are often characterized as deductive qualitative work.

As another example, quantitative researchers use numbers, but these numbers aren’t always meaningful without words. In surveys, interpretation of numerical responses may not be possible without analyzing them alongside free-text responses. And while qualitative researchers rarely use numbers, they do need to think through the frequency with which certain themes appear in their dataset. An idea that only appears once in a qualitative study may have great value to the analysis, but it is also important that researchers acknowledge the views that are most prevalent in a given qualitative dataset.

Key Takeaways

- Quantitative research is generally associated with post-positivism. Since researchers seek to get as close to ‘the truth’, as they can, they value objectivity and seek generalizable results. They generate hypotheses and use deductive reasoning and numerical data numbers to prove or disprove their hypotheses. Replicating patterns of data to validate theories and interpretations is one way to evaluate ‘the truth’.

- Qualitative research is generally associated with worldviews that value subjectivity. Since qualitative researchers seek to understand the interaction between person, place, history, power, gender and other elements of context, they value subjectivity (e.g. interpretivism, constructivism, critical theory). Qualitative research does not seek generalizability of findings (i.e. a universal, decontextualized result), rather it produces results that are inextricably linked to the context of the data and analysis. Data tend to take the form of words, rather than numbers, and are analyzed inductively.

- Qualitative and quantitative research are not opposites. Qualitative and quantitative research are often marked by a set of apparently clear distinctions, but there are always nuances and exceptions. Thus, these approaches should be understood as complementary, rather than diametrically opposed.

Vignette Conclusion

Rayna smiled and read over their paper once more. They had included an explanation of qualitative research, and how it’s about depth of information and nuance of experience. The depth of data generated per participant is significant, therefore fewer people are typically recruited in qualitative studies. Rayna also articulated that while the interpretivist approach she used for analysis isn’t focused on generalizing the results beyond a specific context, they were able to make an argument for how the results can transfer to other, similar contexts. Cal provided a bunch of margin comments in her responses to the reviews, highlighting how savvy Rayna had been in addressing the concerns of Reviewer 2 without betraying their epistemic roots. The editor certainly was right – adding more justification and explanation had made the paper stronger, and would likely help others grow to better understand qualitative work. Now the only challenge left was figuring out how to upload the revised documents to the journal submission portal…

- Wright, S., O’Brien, B. C., Nimmon, L., Law, M., & Mylopoulos, M. (2016). Research Design Considerations. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 8(1), 97–98. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00566.1

- Monteiro S, Sullivan GM, Chan TM. Generalizability theory made simple (r): an introductory primer to G-studies. Journal of graduate medical education. 2019 Aug;11(4):365-70. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-19-00464.1

- Goldenberg MJ. On evidence and evidence-based medicine: lessons from the philosophy of science. Social science & medicine. 2006 Jun 1;62(11):2621-32. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.031

- Varpio L, MacLeod A. Philosophy of science series: Harnessing the multidisciplinary edge effect by exploring paradigms, ontologies, epistemologies, axiologies, and methodologies. Academic Medicine. 2020 May 1;95(5):686-9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003142

- Morse JM, Mitcham C. Exploring qualitatively-derived concepts: Inductive—deductive pitfalls. International journal of qualitative methods. 2002 Dec;1(4):28-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690200100404

- Armat MR, Assarroudi A, Rad M, Sharifi H, Heydari A. Inductive and deductive: Ambiguous labels in qualitative content analysis. The Qualitative Report. 2018;23(1):219-21. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2122314268

- Tavakol M, Sandars J. Quantitative and qualitative methods in medical education research: AMEE Guide No 90: Part I. Medical Teacher. 2014 Sep 1;36(9):746-56. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.915298

- Tavakol M, Sandars J. Quantitative and qualitative methods in medical education research: AMEE Guide No 90: Part II. Medical teacher. 2014 Oct 1;36(10):838-48. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.915297

About the Authors

name: Renate Kahlke

institution: McMaster University

Renate Kahlke is an Assistant Professor within the Division of Education & Innovation, Department of Medicine. She is a scientist within the McMaster Education Research, Innovation and Theory (MERIT) Program.

name: Jonathan Sherbino

name: Sandra Monteiro

Sandra Monteiro is an Associate Professor within the Department of Medicine, Division of Education and Innovation, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University. She holds a joint appointment within the Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact , Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University.

1-2 The Nature of Evidence: Inductive and Deductive Reasoning Copyright © 2022 by Renate Kahlke; Jonathan Sherbino; and Sandra Monteiro is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Principles of Social Research Methodology pp 59–71 Cite as

Inductive and/or Deductive Research Designs

- Md. Shahidul Haque 4

- First Online: 27 October 2022

2491 Accesses

1 Citations

This chapter aims to introduce the readers, especially the Bangladeshi undergraduate and postgraduate students to some fundamental considerations of inductive and deductive research designs. The deductive approach refers to testing a theory, where the researcher builds up a theory or hypotheses and plans a research stratagem to examine the formulated theory. On the contrary, the inductive approach intends to construct a theory, where the researcher begins by gathering data to establish a theory. In the beginning, a researcher must clarify which approach he/she will follow in his/her research work. The chapter discusses basic concepts, characteristics, steps and examples of inductive and deductive research designs. Here, also a comparison between inductive and deductive research designs is shown. It concludes with a look at how both inductive and deductive designs are used comprehensively to constitute a clearer image of research work.

- Deductive research design

- Inductive research design

- Research design

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Beiske, B. (2007). Research methods: Uses and limitations of questionnaires, interviews and case studies . GRIN Verlag.

Google Scholar

Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices (2nd ed.). Global Text Project.

Brewer, J., & Hunter, A. (1989). Multi method research: A synthesis of styles . Sage Publications Ltd.

Burns, N., & Grove, S. K. (2003). Understanding nursing research (3rd ed.). Saunders.

Cambridge Dictionary. (2016a). Hypothesis. In Dictionary.cambridge.org . Retrieved October, 15, 2016, from http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/hypothesis .

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13 , 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593

Article Google Scholar

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications Inc.

Crowther, D., & Lancaster, G. (2009). Research methods: A concise introduction to research in management and business . Butterworth-Heinemann.

Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., & Lowe, A. (2002). Management research: An introduction . Sage Publications Ltd.

Engel, R. J., & Schutt, R. K. (2005). The practice of research in social work . Sage Publications Inc.

Gill, J., & Johnson, P. (2010). Research Methods for Managers (4th ed.). Sage Publications Ltd.

Goddard, W., & Melville, S. (2004). Research methodology: An introduction (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishing.

Godfrey, J., Hodgson, A., Tarca, A., Hamilton, J., & Holmes, S. (2010). Accounting theory (7th ed). Wiley. ISBN: 978-0-470-81815-2.

Gray, D. E. (2004). Doing research in the real world . Sage Publications Ltd.

Hackley, C. (2003). Doing research projects in marketing, management and consumer research . Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Lodico, M. G., Spaulding, D. T., & Voegtle, K. H. (2006). Methods in educational research: From theory to practice . John Wiley & Sons.

Merriam-Webster. (2016a). Inductive. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary . Retrieved October 12, 2016a, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/inductive .

Merriam-Webster. (2016b). Deductive. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary . Retrieved October 12, 2016b, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/deductive .

Morgan, D. L. (2014). Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: A Pragmatic Approach. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781544304533

Neuman, W. L. (2003). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Allyn and Bacon.

Oxford Dictionary. (2016a). Inductive. In Oxford online dictionary . Retrieved October 15, 2016a, from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/inductive .

Oxford Dictionary. (2016b). Deductive. In Oxford online dictionary . Retrieved October 15, 2016b, from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/deductive .

Oxford Dictionary. (2016c). Theory. In Oxford online dictionary . Retrieved October 15, 2016c, from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/theory .

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2007). Research methods for business students (5th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Sherman, L. W., & Berk, R. A. (1984). The specific deterrent effects of arrest for domestic assault. American Sociological Review, 49 (2), 261–272.

Singh, K. (2006). Fundamental of research methodology and statistics. New Age International (P) Limited.

Snieder, R., & Larner, K. (2009). The art of being a scientist: A guide for graduate students and their mentors . Cambridge University Press.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Sage Publications Ltd.

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27 (2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748

Trochim, W. M. K. (2006). Research methods knowledge base. Retrieved on October 12, 2016, from http://www.socialresearchmethods.net .

Wilson, J. (2010). Essentials of business research: A guide to doing your research project . Sage Publishers Ltd.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Social Work, Jagannath University, Dhaka, 1100, Bangladesh

Md. Shahidul Haque

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Md. Shahidul Haque .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Centre for Family and Child Studies, Research Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

M. Rezaul Islam

Department of Development Studies, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Niaz Ahmed Khan

Department of Social Work, School of Humanities, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Rajendra Baikady

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Haque, M.S. (2022). Inductive and/or Deductive Research Designs. In: Islam, M.R., Khan, N.A., Baikady, R. (eds) Principles of Social Research Methodology. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5441-2_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5441-2_5

Published : 27 October 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-19-5219-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-19-5441-2

eBook Packages : Social Sciences

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, qualitative research: deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis.

Qualitative Research Journal

ISSN : 1443-9883

Article publication date: 31 October 2018

Issue publication date: 15 November 2018

The purpose of this paper is to explain the rationale for choosing the qualitative approach to research human resources practices, namely, recruitment and selection, training and development, performance management, rewards management, employee communication and participation, diversity management and work and life balance using deductive and inductive approaches to analyse data. The paper adopts an emic perspective that favours the study of transfer of human resource management practices from the point of view of employees and host country managers in subsidiaries of western multinational enterprises in Ghana.

Design/methodology/approach

Despite the numerous examples of qualitative methods of data generation, little is known particularly to the novice researcher about how to analyse qualitative data. This paper develops a model to explain in a systematic manner how to methodically analyse qualitative data using both deductive and inductive approaches.

The deductive and inductive approaches provide a comprehensive approach in analysing qualitative data. The process involves immersing oneself in the data reading and digesting in order to make sense of the whole set of data and to understand what is going on.

Originality/value

This paper fills a serious gap in qualitative data analysis which is deemed complex and challenging with limited attention in the methodological literature particularly in a developing country context, Ghana.

- Qualitative

- Emic interviews documents

Azungah, T. (2018), "Qualitative research: deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis", Qualitative Research Journal , Vol. 18 No. 4, pp. 383-400. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-D-18-00035

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2018, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Deductive Approach (Deductive Reasoning)

A deductive approach is concerned with “developing a hypothesis (or hypotheses) based on existing theory, and then designing a research strategy to test the hypothesis” [1]

It has been stated that “deductive means reasoning from the particular to the general. If a causal relationship or link seems to be implied by a particular theory or case example, it might be true in many cases. A deductive design might test to see if this relationship or link did obtain on more general circumstances” [2] .

Deductive approach can be explained by the means of hypotheses, which can be derived from the propositions of the theory. In other words, deductive approach is concerned with deducting conclusions from premises or propositions.

Deduction begins with an expected pattern “that is tested against observations, whereas induction begins with observations and seeks to find a pattern within them” [3] .

Advantages of Deductive Approach

Deductive approach offers the following advantages:

- Possibility to explain causal relationships between concepts and variables

- Possibility to measure concepts quantitatively

- Possibility to generalize research findings to a certain extent

Alternative to deductive approach is inductive approach. The table below guides the choice of specific approach depending on circumstances:

Choice between deductive and inductive approaches

Deductive research approach explores a known theory or phenomenon and tests if that theory is valid in given circumstances. It has been noted that “the deductive approach follows the path of logic most closely. The reasoning starts with a theory and leads to a new hypothesis. This hypothesis is put to the test by confronting it with observations that either lead to a confirmation or a rejection of the hypothesis” [4] .

Moreover, deductive reasoning can be explained as “reasoning from the general to the particular” [5] , whereas inductive reasoning is the opposite. In other words, deductive approach involves formulation of hypotheses and their subjection to testing during the research process, while inductive studies do not deal with hypotheses in any ways.

Application of Deductive Approach (Deductive Reasoning) in Business Research

In studies with deductive approach, the researcher formulates a set of hypotheses at the start of the research. Then, relevant research methods are chosen and applied to test the hypotheses to prove them right or wrong.

Generally, studies using deductive approach follow the following stages:

- Deducing hypothesis from theory.

- Formulating hypothesis in operational terms and proposing relationships between two specific variables

- Testing hypothesis with the application of relevant method(s). These are quantitative methods such as regression and correlation analysis, mean, mode and median and others.

- Examining the outcome of the test, and thus confirming or rejecting the theory. When analysing the outcome of tests, it is important to compare research findings with the literature review findings.

- Modifying theory in instances when hypothesis is not confirmed.

My e-book, The Ultimate Guide to Writing a Dissertation in Business Studies: a step by step assistance contains discussions of theory and application of research approaches. The e-book also explains all stages of the research process starting from the selection of the research area to writing personal reflection. Important elements of dissertations such as research philosophy , research design , methods of data collection , data analysis and sampling are explained in this e-book in simple words.

John Dudovskiy

[1] Wilson, J. (2010) “Essentials of Business Research: A Guide to Doing Your Research Project” SAGE Publications, p.7

[2] Gulati, PM, 2009, Research Management: Fundamental and Applied Research, Global India Publications, p.42

[3] Babbie, E. R. (2010) “The Practice of Social Research” Cengage Learning, p.52

[4] Snieder, R. & Larner, K. (2009) “The Art of Being a Scientist: A Guide for Graduate Students and their Mentors”, Cambridge University Press, p.16

[5] Pelissier, R. (2008) “Business Research Made Easy” Juta & Co., p.3

- Open access

- Published: 28 March 2024

Nurses’ perceptions of how their professional autonomy influences the moral dimension of end-of-life care to nursing home residents– a qualitative study

- Rachel Gilbert 1 &

- Daniela Lillekroken ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7463-8977 1

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 216 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

131 Accesses

Metrics details

Over the years, caring has been explained in various ways, thus presenting various meanings to different people. Caring is central to nursing discipline and care ethics have always had an important place in nursing ethics discussions. In the literature, Joan Tronto’s theory of ethics of care is mostly discussed at the personal level, but there are still a few studies that address its influence on caring within the nursing context, especially during the provision of end-of-life care. This study aims to explore nurses’ perceptions of how their professional autonomy influences the moral dimension of end-of-life care provided to nursing home residents.

This study has a qualitative descriptive design. Data were collected by conducting five individual interviews and one focus group during a seven-month period between April 2022 and September 2022. Nine nurses employed at four Norwegian nursing homes were the participants in this study. Data were analysed by employing a qualitative deductive content analysis method.

The content analysis generated five categories that were labelled similar to Tronto’s five phases of the care process: (i) caring about, (ii) caring for, (iii) care giving, (iv) care receiving and (v) caring with. The findings revealed that nurses’ autonomy more or less influences the decision-making care process at all five phases, demonstrating that the Tronto’s theory contributes to greater reflectiveness around what may constitute ‘good’ end-of-life care.

Conclusions

Tronto’s care ethics is useful for understanding end-of-life care practice in nursing homes. Tronto’s care ethics provides a framework for an in-depth analysis of the asymmetric relationships that may or may not exist between nurses and nursing home residents and their next-of-kin. This can help nurses see and understand the moral dimension of end-of-life care provided to nursing home residents during their final days. Moreover, it helps handle moral responsibility around end-of-life care issues, providing a more complex picture of what ‘good’ end-of-life care should be.

Peer Review reports

In recent decades, improving end-of-life care has become a global priority [ 1 ]. The proportion of older residents dying in nursing homes is rising across the world [ 2 ], resulting in a significant need to improve the quality of end-of-life care provided to residents. Therefore, throughout the world, nursing homes are becoming increasingly important as end-of-life care facilities [ 3 ]. As the largest professional group in healthcare [ 4 ], nurses primarily engage in direct care activities [ 5 ] and patient communication [ 6 ] positioning them in close proximity to patients. This proximity affords them the opportunity to serve as information brokers and mediators in end-of-life decision-making [ 7 ]. They also develop trusting relationships with residents and their next-of-kin, relationships that may be beneficial for the assessment of residents and their next-of-kin’s needs [ 8 ]. Moreover, nurses have the opportunity to gain a unique perspective that allows them to become aware of if and when a resident is not responding to a treatment [ 9 ].

When caring for residents in their critical end-of-life stage, nurses form a direct and intense bond with the resident’s next-of-kin, hence nurses become central to end-of-life care provision and decision-making in nursing homes [ 10 ]. The degree of residents and their next-of-kin involvement in the decision-making process in practice remains a question [ 11 ]. Results from a study conducted in six European countries [ 12 ], demonstrate that, in long-term care facilities, too many care providers are often involved, resulting in difficulties in reaching a consensus in care. Although nurses believe that their involvement is beneficial to residents and families, there is a need for more empirical evidence of these benefits at the end-of-life stage. However, the question of who should be responsible for making decisions is still difficult to answer [ 13 ]. One study exploring nurse’s involvement in end-of-life decisions revealed that nurses experience ethical problems and uncertainty about the end-of-life care needs of residents [ 14 ]. Another study [ 10 ] reported patients being hesitant to discuss end-of‐life issues with their next-of-kin, resulting in nurses taking over; thus, discussing end-of-life issues became their responsibility. A study conducted in several nursing homes from the UK demonstrated that ethical issues associated with palliative care occurred most frequently during decision-making, causing greater distress among care providers [ 15 ].

Previous research has revealed that there are some conflicts over end-of-life care that consume nurses’ time and attention at the resident’s end-of-life period [ 16 ]. The findings from a meta-synthesis presenting nurses’ perspectives dealing with ethical dilemmas and ethical problems in end-of-life care revealed that nurses are deeply involved with patients as human beings and display an inner responsibility to fight for their best interests and wishes in end-of-life care [ 17 ].

Within the Norwegian context, several studies have explored nurses’ experiences with ethical dilemmas when providing end-of-life care in nursing homes. One study describing nurses’ ethical dilemmas concerning limitation of life-prolonging treatment suggested that there are several disagreements between the next-of-kin’s wishes and what the resident may want or between the wishes of the next-of-kin and what the staff consider to be right [ 18 ]. Another study revealed that nurses provide ‘more of everything’ and ‘are left to dealing with everything on their own’ during the end-of-life care process [ 19 ] (p.13) . Several studies aiming to explore end-of-life decision-making in nursing homes revealed that nurses experience challenges in protecting the patient’s autonomy regarding issues of life-prolonging treatment, hydration, nutrition and hospitalisation [ 20 , 21 , 22 ]. Other studies conducted in the same context have described that nurses perceive ethical problems as a burden and as barriers to decision-making in end-of-life care [ 8 , 23 ].

Nursing, as a practice, is fundamentally grounded in moral values. The nurse-patient relationship, central to nursing care provision, holds ethical importance and significance. It is crucial to recognise that the context within which nurses practice can both shape and be shaped by nursing’s moral values. These values collectively constitute what can be termed the ethical dimension of nursing [ 24 ]. Nursing ethos and practices are rooted in ethical values and principles; therefore, one of the position statements of the International Council of Nurses [ 25 ] refers to nurses’ role in providing care to dying patients and their families as an inherent part of the International Classification for Nursing Practice [ 26 ] (e.g., dignity, autonomy, privacy and dignified dying). Furthermore, ethical competence is recognised as an essential element of nursing practice [ 27 ], and it should be considered from the following viewpoints: ethical decision-making, ethical sensitivity, ethical knowledge and ethical reflection.

The term ‘end-of-life care’ is often used interchangeably with various terms such as terminal care, hospice care, or palliative care. End-of life care is defined as care ‘to assist persons who are facing imminent or distant death to have the best quality of life possible till the end of their life regardless of their medical diagnosis, health conditions, or ages’ [ 28 ] (p.613) . From this perspective, professional autonomy is an important feature of nurses’ professionalism [ 29 ]. Professional autonomy can be defined based on two elements: independence in decision-making and the ability to use competence, which is underpinned by three themes: shared leadership, professional skills, inter- and intraprofessional collaboration and a healthy work environment [ 30 ].

As presented earlier, research studies have reported that nurses experience a range of difficulties or shortcomings during the decision-making process; therefore, autonomous practice is essential for safe and quality care [ 31 ]. Moreover, autonomous practice is particularly important for the moral dimension in end-of-life care, where nurses may need to assume more responsibility in the sense of defining and giving support to matters that are at risk of not respecting ethical principles or fulfilling their ethical, legal and professional duties towards the residents they care for.

To the best of the researchers’ knowledge, little is known about nurses’ perceptions of how their professional autonomy influences the moral dimension of end-of-life care provided to nursing home residents; therefore, the aim of this study is to explore nurses’ perceptions of how their professional autonomy influences the moral dimension of end-of-life care provided to nursing home residents.

Theoretical framework

Joan Tronto is an American political philosopher and one of the most influential care ethicists. Her theory of the ethics of care [ 32 , 33 , 34 ] has been chosen as the present study’s theoretical framework. The ethics of care is a feminist-based ethical theory, focusing on caring as a moral attitude and a sensitive and supportive response of the nurse to the situation and circumstances of a vulnerable human being who is in need of help [ 33 , 34 , 35 ]. In this sense, nurses’ caring behaviour has the character of a means—helping to reach the goal of nursing practice—which here entails providing competent end-of-life care.

Thinking about the process of care, in her early works [ 32 , 33 , 34 ], Tronto proposes four different phases of caring and four elements of care. Although the phases may be interchangeable and often overlap with each other, the elements of care are fundamental to demonstrate caring. The phases of caring involve cognitive, emotional and action strategies.

The first phase of caring is caring about , which involves the nurse’s recognition of being in need of care and includes concern, worry about someone or something. In this phase, the element of care is attentiveness, which entails the detection of the patient and/or family need.

The second phase is caring for , which implies nurses taking responsibility for the caring process. In this phase, responsibility is the element of care and requires nurses to take responsibility to meet a need that has been identified.

The third phase is care giving , which encompasses the actual physical work of providing care and requires direct engagement with care. The element of care in this phase is competence, which involves nurses having the knowledge, skills and values necessary to meet the goals of care.

The fourth phase is care receiving , which involves an evaluation of how well the care giving meets the caring needs. In this phase, responsiveness is the element of care and requires the nurse to assess whether the care provided has met the patient/next-of-kin care needs. This phase helps preserve the patient–nurse relationship, which is a distinctive aspect of the ethics of care [ 36 ].

In 2013, Tronto [ 35 ] updated the ethics of care by adding a fifth phase of caring— caring with —which is the common thread weaving among the four phases. When care is responded to through care receiving and new needs are identified, nurses return to the first phase and begin again. The care elements in this phase are trust and solidarity. Within a healthcare context, trust builds as patients and nurses realise that they can rely on each other to participate in their care and care activities. Solidarity occurs when patients, next-of-kin, nurses and others (i.e., ward leaders, institutional management) engage in these processes of care together rather than alone.

To the best of our knowledge, these five phases of caring and their elements of caring have never been interpreted within the context of end-of-life care. The ethics of care framework offers a context-specific way of understanding how nurses’ professional autonomy influences the moral dimension of end-of-life care provided to nursing home residents, revealing similarities with Tronto’s five phases, which has motivated choosing her theory.

Aim of the study

The present study aims to explore nurses’ perceptions of how their professional autonomy influences the moral dimension of end-of-life care provided to nursing home residents.

The current study has a qualitative descriptive design using five individual interviews and one focus group to explore nurses’ perceptions of how their professional autonomy influences the moral dimension of end-of-life care provided to nursing home residents.

Setting and participants

The setting for the study was four nursing homes located in different municipalities from the South-Eastern region of Norway. Nursing homes in Norway are usually public assisted living facilities and offer all-inclusive accommodation to dependent individuals on a temporary or permanent basis [ 37 ]. The provision of care in the Norwegian nursing homes is regulated by the ‘Regulation of Quality of Care’ [ 38 ], aiming to improve nursing home residents’ quality of life by offering quality care that meets residents’ fundamental physiological and psychosocial needs and to support their individual autonomy through the provision of daily nursing care and activities tailored to their specific needs, and, when the time comes, a dignified end-of-life care in safe milieu.

End-of-life care is usually planned and provided by nurses having a post graduate diploma in either palliative nursing or oncology nursing– often holding an expert role, hence ensuring that the provision of end-of-life care meets the quality criteria and the resident’s needs and preferences [ 39 ].

To obtain rich information to answer the research question, it was important to involve participants familiar with the topic of study and who had experience working in nursing homes and providing end-of-life care to residents; therefore, a purposive sample was chosen. In this study, a heterogeneous sampling was employed, which involved including participants from different nursing homes with varying lengths of employment and diverse experiences in providing end-of-life care to residents. This approach was chosen to gather data rich in information [ 40 ]. Furthermore, when recruiting participants, the first author was guided by Malterud et al.’s [ 41 ] pragmatic principle, suggesting that the more ‘information power’ the participants provided, the smaller the sample size needed to be, and vice versa. Therefore, the sample size was not determined by saturation but instead by the number of participants who agreed to participate. However, participants were chosen because they had particular characteristics such as experience and roles which would enable understanding how their professional autonomy influences the moral dimension of end-of-life care provided to nursing home residents.

The inclusion criteria for the participants were as follows: (i) to be a registered nurse, (ii) had a minimum work experience of two years employed at a nursing home, and (iii) had clinical experience with end-of-life/palliative care. To recruit participants, the first author sent a formal application with information about the study to four nursing homes. After approval had been given, the participants were asked and recruited by the leadership from each nursing home. The participants were then contacted by the first author by e-mail and scheduled a time for meeting and conducting the interviews.

Ten nurses from four different nursing homes were invited to participate, but only nine agreed. The participants were all women, aged between 27 and 65 and their work experience ranged from 4 to 21 years. Two participants had specialist education in palliative care, and one was currently engaged in a master’s degree in nursing science. Characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1 :

Data collection methods

Data were collected through five semistructured individual and one focus group interviews. Both authors conducted the interviews together. The study was carried out between April and September 2022. Due to the insecurity related to the situation caused by the post-SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic and concerns about potential new social distancing regulations imposed by the Norwegian government, four participants from the same nursing home opted for a focus group interview format. This decision was motivated by a desire to mitigate the potential negative impact that distancing regulations might have on data collection. The interviews were guided by an interview guide developed after reviewing relevant literature on end-of-life care and ethical dilemmas. The development of the interview guide consisted of five phases: (i) identifying the prerequisites for using semi-structured interviews; (ii) retrieving and using previous knowledge; (iii) formulating the preliminary semi-structured interview guide; (iv) pilot testing the interview guide; and (v) presenting the complete semistructured interview guide [ 42 ]. The interview guide was developed by both authors prior to the onset of the project and consisted of two demographic questions and eight main open-ended questions. The interview guide underwent initial testing with a colleague employed at the same nursing home as the first author. After the pilot phase in phase four, minor language revisions were made to specific questions to bolster the credibility of the interview process and ensure the collection of comprehensive and accurate data. The same interview guide was used to conduct individual interviews and focus group (Table 2 ).

The interviews were all conducted in a quiet room at a nursing home. Each interview lasted between 30 and 60 min and were digitally recorded. The individual interviews were transcribed verbatim by the first author. The focus group interview was transcribed by the second author.

Ethical perspectives

Prior to the onset of the data collection, ethical approval and permission to conduct the study were sought from the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (Sikt/Ref. number 360,657) and from each leader of the nursing home. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association [ 43 ]: informed consent, consequences and confidentiality. The participants received written information about the aim of the study, how the researcher would ensure their confidentiality and, if they chose to withdraw from the study, their withdrawal would not have any negative consequences for their employment at nursing homes. Data were anonymised, and the digital records of the interviews were stored safely on a password-protected personal computer. The transcripts were stored in a locked cabinet in accordance with the existing rules and regulations for research data storage at Oslo Metropolitan University. The participants did not receive any financial or other benefits from participating in the study. Written consent was obtained prior to data collection, but verbal consent was also provided before each interview. None of the participants withdrew from the study.

Data analysis

The data were analysed by employing a qualitative deductive content analysis, as described by Kyngäs and Kaakinen [ 44 ]. Both researchers independently conducted the data analysis manually. The empirical data consisted of 63 pages (34,727 words) of transcripts from both individual and focus group interviews. The deductive content analysis was performed in three steps: (i) preparation, (ii) organisation and (iii) reporting of the results.