Jotted Lines

A Collection Of Essays

Do The Right Thing: Summary, Analysis

Summary: .

Set on a city block during the hottest day of the summer in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant (‘Bed-Stuy’), Do The Right Thing follows the character of ‘Mookie’ (Spike Lee), a pizza delivery boy, and a day in the life of the neighborhood residents as the climate gives way to escalating encounters and disputes around culture, ethnicity and community.

Do The Right Thing was Spike Lee’s third feature film following School Daze (1988) and She’s Gotta Have It (1986). The film came a decade removed from the Blaxploitation film cycle and two years before the ‘black film explosion’ of 1991.1 A prolific film auteur, Lee continues to challenge the idea of black film and American cinema.

The opening credits of Do The Right Thing open to the strains of a soprano saxophone rendition of James Weldon Johnson’s ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’. The song ends screen black and the title sequence begins with Public Enemy’s ‘Fight The Power’ and a cut to a stage. Evoking the conceit of the film musical’s opening number, the montage of the sequence features the hip-hop dance of Rosie Perez in multiple costumes against a changing backdrop of Brooklyn photographs backlit by an array of colour schemes. This opening montage is cut to match the movements of Perez’s dance, a dance of militancy and popping contractions with a face that never smiles. She is more than merely a woman to be leered at or reductively posed as an object of pleasure. Her dance signals a cultural politics of hip-hop and what Guthrie Ramsey notes as the mark of ‘a present that has urgency, particularity, politics, and pleasure’. 2 With these two compositions and their distinct spatiotemporal origins, the present of Do The Right Thing demonstrates a century of urgency.

‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’ began as a poem by James Weldon Johnson that debuted in 1900. Johnson and Johnson’s brother, J. Rosamond, would set the poem to music and this composition would eventually be dubbed the ‘The Negro National Anthem’ and adopted as the official song of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The NAACP promoted the use of the song as an anthem for the black struggle for access to freedoms and inalienable rights denied by the discriminatory and terrorist practices of white supremacy and the Racial Contract. Moreover, the use of the song during the Civil Rights Movement and its eventual retitling (‘The Black National Anthem’) continued the purposing of the song as black anthem of protest. As Shana Redmond points out,

“Black anthems become incubators not only for a race/sound fusion but also the merger of art and practice. The conditions that give rise to these anthems within diaspora include colonialism, Jim Crow segregation, and myriad legal and extralegal enactments of persistent inequality; therefore liberation and its pursuit are necessarily narrated and exercised in tandem with philosophies and acts of resistance.” 3

Public Enemy offers an anthem less reconciled to the Christian doctrine of social protest and nonviolence but nonetheless remains a song compelled by conditions that animate defiant verse.

While the first song offers the perseverance of faith and belief in inalienable rights, the latter demonstrates a cultural nationalist tact, a more politicised sense of culture and the black lifeworld. Cultural nationalism shifted the meaning of race from the biological to a deliberate posing of race as cultural praxis and a matter of engagement with the anti-hegemonic struggle against white supremacy as embodying features of black personhood. Moreover, the distance between the poles is made plainer with the modal of hip-hop modernism and not that of the sacred verse of gospel. As a sorrow song of what Mark Anthony Neal calls ‘postindustrial soul’, ‘Fight The Power’ offers a sobering and artful discontent from streets far removed from Birmingham, but a relation nonetheless.4

The depth of Do The Right Thing demonstrates the staging of a political art richly informed by multiple historiographies of black visual and expressive culture. The film is propelled by an intersection of history, music, cinema and blackness. This generative nexus of historical scripts encompasses such issues as gentrification, the black public sphere, police brutality, the popular, cultural and ethnic conflict, and the everyday urban. In other words, anti-realist in its stance, the film positions itself in the matrix of black representation as an interpretative echo and refabulation of race and art. The film employs a 24-hour conceit of the hottest day of the summer in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant (‘Bed-Stuy’). This plotting of a ‘day in the life’ amplifies the masterful way the film functions as a discrete representational system. The seamless accounting of the day on the block through continuity editing is facilitated by such things as Mister Señor Love Daddy’s radio broadcast, colour, physical movements, emblematic framing, an intricate orchestration of ensemble casting in the depth of field, and sound bridges. With the deliberateness of the film structure, one learns to watch the film and recognise the spatiality of the setting. Eventually, one recognises that at one end of the block is Mookie and Jade’s building, Mother Sister’s brownstone, the Korean-run grocery, and across the street against the red wall are the corner crew (Sweet Dick Willie, ML, and Coconut Sid). At the other end of the block, starting across from the grocery is Sal’s Famous Pizzeria, the stoop where the Puerto Ricans sit, the station home for 108FM ‘We Love Radio’, and the brownstone owned by the Celtics’ fan. The film details a dynamic community of personalities and histories, a space textured by infinite encounters.

The cohesiveness of this spatial conceit does not comply with the platitudes of Our Town, USA. The film proves that the most rewarding consequence of America as ‘The Melting Pot’ is that the analogy has never worked. We the people are not the same: we have different cultures, belief systems, and freedom dreams. These differences Do The Right Thing (1989) 209 represent at times collateral interests but never truly identical ones. In this way, the interethnic conflicts that circulate up and down the block are but a red herring. Do The Right Thing vitally avoids the classical tact of the social problem film to present the problem of differences as systemic or a result of the idea of America itself. In the social problem film, these staged eruptions of racial conflict are resolved and contained with a tacit framing of our spectatorship in terms of cinematically enacted cures.

As Michael Rogin writes, ‘Hollywood, inheriting and universalizing blackface in the blackface musical, celebrated itself as the institutional locus of American identity. In the social problem film it allied itself with the therapeutic society. Generic overlap suggests institutional overlap; Hollywood was not just Hortense Powdermaker’s dream factory, but also the American interpreter of dreams, employing roleplaying as national mass therapy.’ 5 Social problem films with race as their object choice usually enact a limited and circumspect sense of social problem-solving. In particular, the way these films are saddled with the extra-diegetic responsibilities of reconciliation between the races promotes a dangerously ridiculous sense of film as social policy. After all, what James Baldwin called the ‘price of the ticket’ should mean more than matinee admission. Do The Right Thing poignantly demands that one’s spectatorship entail a recognition of our respective subject positions and/or complicities in a productively non-patronising way.

The central conflict of Do The Right Thing cycles around the issue of How come there ain’t no brothas on the wall? Outraged by the absence of black representation on the pizzeria wall, Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito) organises a boycott against Sal’s Pizzeria in response to the ‘Wall of Fame’, a collage of photographs devoted to Italian Americans. The call for economic sanctions echoes the use of these strategies throughout the twentieth century by churches, unions and civic leaders as a way of combatting the economic disenfranchisement of anti-black racism. This call for representation is emblematic of a diacritical sense of value. First, there is the value suggested by economic empowerment of a raced consumer-citizen. Second, there is the measure of culture as value. In this way, the central conflict that accrues over the course of the film becomes that of the political and cultural value of blackness.

However, the film’s vessel of civil disobedience and cultural nationalism is far from sound. Buggin’ Out does not articulate a clear plan of black economic development. His persona is that of empty rhetoric; more hothead than firebrand. Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn) lumbers and speaks like a heroic throwback from the mind of Jack Kirby. A laconic giant, his voice and being are embodied by ‘Fight the Power’, the only thing constantly blaring from his boombox. His ‘Love vs. Hate’ direct address constitutes the most that he ever speaks, a gesture to the absurd holyroller ways of Robert Mitchum’s itinerant honeymoon killer in Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton, 1955). Yet, this ad infinitum struggle between good and evil, coupled with Raheem’s devotion to the gospel of Public Enemy, frame him as a very textured figure. He wanders throughout Bed-Stuy spreading the word, battling any and all windmills along the way. Every interaction is a contest and exclamation of his being. Finally, closing out the rebel band is Smiley (Roger Guenveur Smith). Mentally disabled and physically spastic, Smiley’s speech is as indecipherable as the irreconcilable coupling of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. in the photograph postcards he marks and peddles. Stumbling through the film, Smiley tags his cherished wares in a style imitative of Jean-Michel Basquiat.6

This crisis of representation emblematic of this rebel ensemble embodies the necessary tensions surrounding the political question of black representation and film as an art practice. Specifically, what is the purpose of the term ‘black film’? Does it represent an entirely foreign film practice? Is it merely a reflection of black people, not art but simply black existential dictation? Like all other expressions of the idea of black film, Do The Right Thing should not be thought as mimetically tied to the social category of race. The ‘black’ of black film represents something other than merely people. Instead it must be appreciated in terms of the art of film and enactments of black visual and expressive culture. In this way, film blackness functions as a critical term for the way race is rendered and mediated by the art of film.7

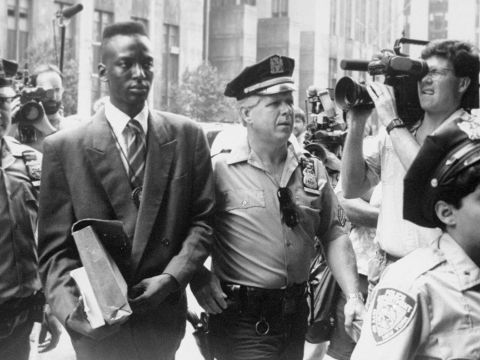

This alienation effect of the film escalates with the final sequence of Radio Raheem’s murder by 210 Do The Right Thing (1989) the police. The broken band of rebels storm the pizzeria and what begins as canted and absurd quickly accelerates. Sal begins a litany of ‘nigger’ and pulls out a baseball bat. He then proceeds to destroy Raheem’s boombox, silencing the roar of the Public Enemy anthem.8 Yes, the film resonates with prejudices and interethnic conflict but it also gestures towards the idea of communities constituted by ambivalences. Regardless, the confusion of this confrontation signals a shattering break. Things have gone too far and as Radio Raheem strangles Sal, pulling him over the counter, the fight spills into the street. The fight draws a crowd and the NYPD arrive. A police hold is administered with a nightstick against Raheem’s neck as he is raised and lynched until his kicks wind down. He is murdered. Radio Raheem is dead.

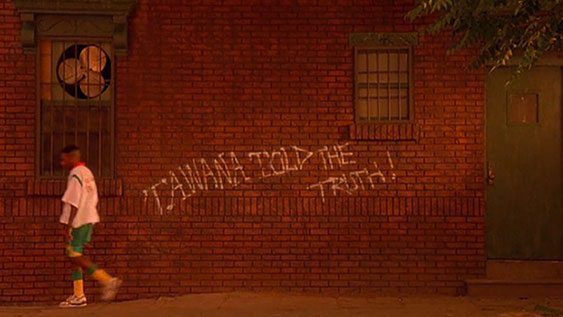

A void appears in the quick exit of the police with a corpse and Buggin’ Out in tow. There is the mournful calm of what has happened and how it has come to this. Mookie they killed him. They killed Radio Raheem. A divide appears, with Mookie, Sal, Pino and Vito on one side and the witnesses from the neighbourhood frozen still, growing angrier in the street. Everyone is a stranger; everyone is revealed. Murder. They did it again. Just like Michael Stewart. Murder. Eleanor Bumpers. Murder.9 The extradiegetic victims of murder at the hands of the police (not persons unknown) now have Raheem among their ranks. Mookie walks away before returning into this breach, throwing a garbage can through the pizzerio’s window. Fireman and police readied in riot gear arrive and the historical rupture is complete. Even in the absence of Birmingham’s finest with German Shepherds at hand, Sweet Dick Willie makes it plain: Yo where’s Bull Connor?10 Smiley begins a new Wall of Fame amid the wreckage by tacking one of his postcards on the smouldering wall: finally some brothers are on the wall. But, was this really what it was all about? Smiley with his ever-delirious visage appears to be the only one to claim some semblance of a victory.

The day after brings the new normal of an awkward, yet tender, meeting between Mookie and Sal. In the end, Mister Señor Love Daddy broadcasts the only available closure – a reminder to register to vote and a mournful shout-out to Radio Raheem.11 The film ends with scrolling citations from Martin Luther King Jr. and X before the film’s final image: the King and X photograph. The offering of these two contrasting political positions – the immorality of violence and the pragmatism of self-defence – is one of the major reasons that the film continues to haunt, inspire, and provoke. For only there on the screen does their proximity hint at some kind of dialectical resolve or compatibility. Do The Right Thing orchestrates the tensions and distinctions between social categories of racial being and the art of film. The film is a question masquerading in the form of a call to action. In other words, the film functions in a way too irresolute to be thought of as merely provocative protest. If the film is troubling, so be it. Killing the messenger has always been convenient, but it never truly disavows that a message has been sent. Always do the right thing. That’s it? That’s it. I got it. I’m gone.

Michael B. Gillespie

Notes

1. For more on the history of the Blaxploitation cycle and the significance of 1991, see Ed Guerrero, Framing Blackness, Philadelphia, PA, Temple University Press, 1993.

2. Guthrie Ramsey, Race Music: Black Cultures from Be Bop to Hip-Hop, Berkeley, CA, University of California Press, 2003, p. 178.

3. Shana L. Redmond, ‘Citizens of Sound: Negotiations of Race and Diaspora in the Anthems of the UNIA and NAACP’, African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2011, p. 22.

4. See Mark Anthony Neal, What The Music Said: Black Popular Music and Black Public Culture, London and New York, Routledge, 1999, pp. 125–57.

5. Michael Rogin, Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot, Berkeley, CA, University of California Press, 1998, p. 221.

6. The photograph was taken on March 26, 1964, in the halls of the United States Capitol Building during Senate debates on the Civil Rights Bill. It documents the only meeting between the two men and lasted only a few minutes.

7. For more on ‘film blackness’, see Michael B. Gillespie, ‘Reckless Eyeballing: Coonskin, Film Blackness, and the Racial Grotesque’, in Mia Mask (ed.), Contemporary Black American Cinema: Race, Gender and Sexuality at the Movies, New York, Routledge, 2012. Also, see the press conference (May 1989) that followed the premiere screening of Do The Right Thing at the Cannes Film Festival. (Available on the Criterion Collection and 20th Anniversary Edition DVD releases of the film.) The insistence by much of the audience on reading Do The Right Thing in social reflectionist terms glaringly illustrates the need to distinguish between black people and black film.

8. The baseball bat references Howard Beach and the death of Michael Griffith. On the evening of 19 December 1986, a group of black men entered a pizzeria in the Queens neighbourhood of Howard Beach seeking help after their car broke down a few miles away. Upon leaving, the men were confronted by a group of Italian Americans from the neighbourhood armed with baseball bats. Attempting to escape from a continued beating by the mob, Griffith was struck and killed by a car on the highway.

9. Michael Stewart was a New York City graffiti artist killed while in the custody of New York Transit Police (1983). Eleanor Bumpers was a mentally ill, African American senior citizen killed by NYPD officers during the eviction from her home (1984).

10.Eugene ‘Bull’ Connor served as Public Safety Commissioner of Birmingham, Alabama (1957–1963). A rabid white supremacist, Connor was responsible for the brutal and violent responses (the use of police dogs and fire hoses against protestors) to the desegregation campaigns spearheaded by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

11.This call to vote was part of Lee’s endorsement of David Dinkins’ mayoral run. Dinkins would be elected New York City’s first African American mayor the following year.

Cast and Crew:

[Country: USA. Production Company: A Forty Acres and a Mule Filmworks Production. Director: Spike Lee. Producer: Spike Lee. Co-producer: Monty Ross. Line Producer: Jon Kilik. Screenwriter: Spike Lee. Cinematographer: Ernest Dickerson. Editor: Barry Alexander Brown. Music: Bill Lee, featuring Branford Marsalis. Cast: Danny Aiello (Sal), Ossie Davis (Da Mayor), Ruby Dee (Mother Sister), Richard Edson (Vito), Giancarlo Esposito (Buggin’ Out), Spike Lee (Mookie), Bill Nunn (Radio Raheem), John Turturro (Pino), Paul Benjamin (ML), Frankie Faison (Coconut Sid), Robin Harris (Sweet Dick Willie), Joie Lee (Jade), Miguel Sandoval (Officer Ponte), Rick Aiello (Officer Long), John Savage (Clifton), Samuel L. Jackson (Mister Señor Love Daddy), Rosie Perez (Tina), Roger Guenveur Smith (Smiley), Steve White (Ahmad), Martin Lawrence (Cee), Leonard Thomas (Punchy), Christa Rivers (Ella), Frank Vincent (Charlie).]

Further Reading:

Darby English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness, Boston, MIT Press, 2007.

Ed Guerrero, Do The Right Thing, London, BFI Publishing, 2001.

Stuart Hall, ‘What is this “black” in black popular culture?’ and ‘New Ethnicities’ in David Morely and Kuan-Hsing Chen (eds), Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, New York, Routledge, 1996, pp. 468–78.

Spike Lee with Lisa Jones, Do the Right Thing, New York, Fireside, 1989.

Mia Mask (ed.), Contemporary Black American Cinema: Race, Gender and Sexuality at the Movies, New York, Routledge, 2012.

Paula J. Massood (ed.), The Spike Lee Reader, Philadelphia, PA, Temple University Press, 2007.

W. J. T. Mitchell, ‘The Violence of Public Art: Do the Right Thing’, Critical Inquiry, Vol. 16, No. 4, Summer, 1990, pp. 880–99.

Source Credits:

The Routledge Encyclopedia of Films, Edited by Sarah Barrow, Sabine Haenni and John White, first published in 2015.

Related Posts:

- She’s Gotta Have It (Movie): Summary & Analysis

- Killer of Sheep: Summary & Analysis

- The Cool World (Movie): Summary & Analysis

- Towards a Definition of Film Noir (1955) by Raymond Borde and Etienne Chaumeton

- Notes on Film Noir (1972) by Paul Schrader

- Malcolm X – Movie Report

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Film Colossus

Your Guide to Movies

Do the Right Thing (1989) | The Definitive Explanation

Welcome to our Colossus Movie Guide for Do the Right Thing . This guide contains everything you need to understand the film. Dive into our detailed library of content, covering key aspects of the movie. We encourage your comments to help us create the best possible guide. Thank you!

What is Do the Right Thing about?

Do the Right Thing is an emblematic narrative about racial tension, policing, and the consequences of pent-up frustration in a culturally diverse community. The film presents a microcosm of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, on the hottest day of the summer, where a boiling point of racial conflict reaches its inevitable climax. Central to this tale is the inherent paradox of “doing the right thing,” a theme that is complex and is constantly reframed, thereby triggering the audience to question its own moral compass.

The movie’s core conflict derives from the systemic divide and racial disparity witnessed within the urban neighborhood, projecting both subtle and overt displays of prejudice. From Sal’s pizzeria, a locus of contention due to its Wall of Fame lacking black celebrities, to the fatal chokehold incident, Do the Right Thing continually forces audiences to grapple with what is just and unjust. The film’s conclusion leaves an impression of cyclical violence, suggesting that the resolution of societal conflicts can’t be achieved through violent retaliation, but also pointing out that peaceful protests often go unheard. By not providing a clear answer to what the “right thing” is, the movie suggests that the path towards justice is labyrinthine and fraught with challenging ethical dilemmas.

Movie Guide table of contents

The ending of do the right thing explained, the themes and meaning of do the right thing.

- Why is the movie called Do the Right Thing?

Important motifs in Do the Right Thing

Questions & answers about do the right thing.

- Spike Lee – Mookie (also writer and director)

- Danny Aiello – Sal

- John Turturro – Pino

- Richard Edson – Vito

- Bill Nunn – Radio Raheem

- Rosie Perez – Tina

- Giancarlo Esposito – Buggin’ Out

- Ossie Davis – Da Mayor

- Ruby Dee – Mother Sister

- Samuel L. Jackson – Mister Señor Love Daddy

- Roger Guenveur Smith – Smiley

- Rick Aiello – Officer Gary Long

- Miguel Sandoval – Officer Mark Ponte

- Joie Lee – Jade

- Martin Lawrence – Cee

- Leonard L. Thomas – Punchy

- Christa Rivers – Ella

- Robin Harris – Sweet Dick Willie

- Paul Benjamin – ML

- Frankie Faison – Coconut Sid

A recap of the ending

Buggin’ Out, Radio Raheem, and Smiley storm into Sal’s Pizzeria, protesting Sal’s Wall of Fame. Sal orders Raheem to turn off his blaring boombox, but Radio Raheem refuses. Fueled by the tension, Buggin’ Out becomes derogatory towards Sal and his sons, vowing to close the establishment until Black people are represented on the Wall.

Sal retaliates in a fit of anger, racially insulting Buggin’ Out and smashing Raheem’s boombox, sparking a brawl that quickly engulfs the pizzeria and spills onto the streets, attracting a crowd. As Raheem puts Sal in a chokehold, Officers Long and Ponte arrive to quell the chaos. Raheem and Buggin’ Out are apprehended, and in an alarming twist, Long chokes Raheem with his nightstick despite pleas from Ponte and the crowd. Raheem’s life is tragically taken and the officers, cognizant of their error, hastily drive off with his body.

The crowd, shattered and incensed over Radio Raheem’s death, hold Sal and his sons accountable. Da Mayor tries to reason with the crowd about Sal’s innocence but to no avail. Overcome by fury and sorrow, Mookie hurls a trash can through Sal’s Pizzeria window, catalyzing the mob to raid and wreck the establishment. Smiley sets it ablaze as Da Mayor rescues Sal and his sons from the impending mob, now fixated on Sonny’s store.

Sonny, in a state of dread, successfully dissuades the mob. With the arrival of the police, firemen, and riot patrols, the crowd is dispersed, and the fire is extinguished amidst continued discord and arrests. A bewildered Mookie and Jade observe the scene from a safe distance while Smiley, reentering the charred premises, places one of his photos on the remnants of Sal’s Wall.

In the aftermath, Mookie confronts Sal about his due pay, following an argument with Tina. The two men bicker, reach an uneasy truce, and Sal finally pays Mookie his wages. Local DJ Mister Señor Love Daddy memorializes Radio Raheem with a dedicated song.

As the film nears its end, contrasting quotes on violence by Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X appear, followed by an image of the two leaders in a handshake.

Here is the quote from Martin Luther King, Jr.:

Violence as a way of achieving racial justice is both impractical and immoral. It is impractical because it is a descending spiral ending in destruction for all. The old law of an eye for an eye leaves everybody blind. It is immoral because it seeks to humiliate the opponent rather than win his understanding; it seeks to annihilate rather than to convert. Violence is immoral because it thrives on hatred rather than love. It destroys community and makes brotherhood impossible. It leaves society in monologue rather than dialogue. Violence ends by destroying itself. It creates bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers.

And the quote from Malcolm X:

I think there are plenty of good people in America, but there are also plenty of bad people in America and the bad ones are the ones who seem to have all the power and be in these positions to block things that you and I need. Because this is the situation, you and I have to preserve the right to do what is necessary to bring an end to that situation, and it doesn’t mean that I advocate violence, but at the same time I am not against using violence in self-defense. I don’t even call it violence when it’s self-defense, I call it intelligence.

The film is then dedicated to the families of six victims of police brutality or racial violence: Eleanor Bumpurs, Michael Griffith, Arthur Miller Jr., Edmund Perry, Yvonne Smallwood, and Michael Stewart.

The escalation of racial tensions

The climactic confrontation in Do the Right Thing is a reflection of escalating racial tensions that have been brewing throughout the entire film. The tension between the different racial groups in the neighborhood is palpable from the onset, underscored by motifs of incredible heat and Sal’s Wall of Fame.

The heat represents the smoldering racial tensions within the community. The sweltering summer weather creates an atmosphere of restlessness and agitation that mirrors the community’s emotional state. It’s a visual and sensory metaphor for how racial tension and frustration can simmer below the surface, intensifying until they reach a boiling point.

Sal’s Wall of Fame acts as another significant symbol, representing the denial of racial recognition. The wall, adorned with only Italian-American celebrities, starkly contrasts with the predominantly Black neighborhood the pizzeria resides in. This omission doesn’t go unnoticed, especially by Buggin’ Out, and becomes a significant point of contention that adds to the building tension.

When Sal destroys Raheem’s boombox after a heated confrontation over the Wall of Fame, it is not merely an act of aggression but a metaphorical dismissal of the Black community’s culture and identity, thus igniting the existing tension into a full-blown conflict. The fight spills onto the streets, attracting a crowd and the police’s attention, which culminates in Raheem’s tragic death by chokehold.

Radio Raheem’s death thus underscores the deadly consequences of systemic racism and racial tension. Even though Sal didn’t instigate the fight, he becomes the community’s target due to Raheem’s unjust death, showing how racial tension can distort perceptions and escalate conflicts. This escalation reflects the destructive cycle of racial prejudice, illustrating how deep-seated biases can lead to unjustifiable violence.

The riot and its symbolism

Riots are often a manifestation of pent-up frustrations of marginalized communities. In Do the Right Thing , the destruction of Sal’s Pizzeria is the physical representation of this suppressed anger breaking free. The community feels disenfranchised, and this explosive display of defiance becomes a means to voice their longstanding grievances.

The riot, in this sense, becomes a form of catharsis, an emotional release for the community. For them, it’s a reaction against systemic inequities that they have been forced to endure. It is a destructive, yet significant, means of rebellion against a system that consistently overlooks their needs and concerns. While the destruction may seem senseless to an outside observer, for the people involved, it is an act of reclaiming power and agency, however transient it might be.

This act of rebellion is further underscored by Radio Raheem’s earlier “Love and Hate” speech. Here is that speech in full:

Let me tell you the story of Right Hand, Left Hand. It’s a tale of good and evil. Hate: it was with this hand that Cain iced his brother. Love: these five fingers, they go straight to the soul of man. The right hand: the hand of love. The story of life is this: static. One hand is always fighting the other hand, and the left hand is kicking much ass. I mean, it looks like the right hand, Love, is finished. But hold on, stop the presses, the right hand is coming back. Yeah, he got the left hand on the ropes, now, that’s right. Ooh, it’s a devastating right and Hate is hurt, he’s down. Left-Hand Hate KOed by Love.

That speech takes on an ironic tone as the riot unfolds. The community, driven by love for their own and a sense of justice, turns to what can be perceived as an act of hate: the destruction of Sal’s pizzeria.

This irony embodies the complex reality of racial struggles, where love for one’s community can lead to actions perceived as hateful. The riot, while destructive, embodies this struggle, highlighting the community’s desperate need for acknowledgment and change. It shows that when pushed to the brink, when love seems to be losing the fight, actions born out of frustration and a thirst for justice can be misunderstood as acts of hate.

Mookie’s act of throwing the trash can is a powerful image and a potent symbol for the ongoing struggle between love and hate that Radio Raheem talks about. Mookie loves his community and sees it suffer. He’s also aware that Sal’s pizzeria, at that moment, is a symbol of the community’s oppression—an embodiment of the racial tensions and the lack of recognition that sparked the fight and led to Raheem’s death. Mookie chooses an act of apparent hate, not because he hates Sal personally, but out of love for his community and a need for justice. You could also argue that he throws the trash can out of love in order to protect Sal and his sons.

The struggle for recognition and respect

In the aftermath of the riot, Mookie’s return to Sal to demand his weekly pay carries significant symbolic weight. Mookie’s insistence on being paid, despite the previous night’s catastrophic events, underscores a fundamental theme of the film: the struggle for recognition and respect.

Mookie’s demand for his salary, against the backdrop of the smoldering remnants of Sal’s pizzeria, isn’t just about money. It represents his assertion of self-worth and dignity in a system that consistently undermines it. Mookie, a pizza delivery man, has spent his days serving the community, and his demand for pay is symbolic of his fight for acknowledgment of his labor’s value, even amidst chaos. And Sal’s eventual decision to pay Mookie, albeit begrudgingly, signifies a moment of recognition.

This scene, however, doesn’t suggest a complete resolution of the racial tension. Instead, it reveals a moment of temporary truce within the ongoing struggle, a small step towards mutual recognition. It emphasizes that the journey towards racial harmony and recognition is fraught with conflict, but not devoid of the potential for understanding and change. This small act of transaction underscores the film’s commentary on the complex dynamics of race, labor, and respect in a racially diverse community.

Ending with contrasting philosophies

At the end of Do the Right Thing , Spike Lee presents quotes from two iconic figures in the civil rights movement: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. These quotes reflect their respective philosophies towards social change: King’s nonviolent resistance and Malcolm X’s belief in self-defense in the face of oppression.

King once said, “The old law of an eye for an eye leaves everyone blind.” This speaks to his conviction that violent reprisals, while initially gratifying, are ultimately detrimental to the larger goal of societal harmony.

In contrast, Malcolm X once stated, “I am for violence if non-violence means we continue postponing a solution to the American black man’s problem—just to avoid violence.” This is emblematic of his belief in the legitimacy of violence as a tool for self-defense, asserting that black people have the right to protect themselves when institutions fail to do so.

Spike Lee’s decision to include these seemingly contrasting statements is a reflection of the complex nature of racial struggle, particularly as it’s depicted in the movie. The narrative doesn’t promote one approach over the other. Instead, it showcases the multifaceted and often conflicting responses to racial oppression.

By juxtaposing these quotes, Lee suggests that the film’s narrative is not a prescriptive solution to racial tensions, but an exploration of the myriad ways individuals might respond to the same. It’s a recognition that the struggle for racial equality is not monolithic and that different approaches can coexist, even if they seem contradictory.

In the end, Do the Right Thing doesn’t definitively answer what the “right thing” is. Instead, it encourages viewers to contemplate the complexities of racial tension and the multitude of responses it evokes. This makes the film not just a depiction of racial tension, but also a platform for dialo

Racial tension

Racial tension is a pervasive theme in Do the Right Thing , manifesting through various characters, their interactions, and conflicts. The film provides a microcosmic view of the broader racial dynamics in America by focusing on a single day in a Brooklyn neighborhood. It presents racial tension not as an external force, but as an inherent part of everyday life in an ethnically diverse society.

The struggle for racial recognition

Racial recognition, or the lack thereof, serves as a significant driving force behind the tension and conflict in Do the Right Thing . The struggle for recognition and respect of one’s racial identity and culture is a shared experience among many characters, creating an undercurrent of resentment and frustration that fuels the escalating tension throughout the film.

The struggle for racial recognition is deeply entwined with the motif of Sal’s Wall of Fame. The Wall, solely featuring Italian-American celebrities, stands in Sal’s Pizzeria, a business operating in a predominantly black neighborhood and serving mostly black customers. The Wall becomes a symbolic site of contention because it omits representation of the black community, even though the pizzeria is a shared community space. This omission is a stark reminder of the broader societal bias that often overlooks the contributions of marginalized groups.

Buggin’ Out, recognizing this lack of representation, challenges Sal to include African American icons on the Wall. Sal’s refusal and his argument that it’s his pizzeria and he can display whomever he wishes shows an entrenched racial bias and disregard for the cultural contributions of his black customers. This conflict underlines the struggle for racial recognition, illustrating how the lack of representation can lead to feelings of erasure and fuel discontent.

The motif of baseball serves a similar purpose, highlighting the struggle for racial recognition within shared cultural experiences. The heated argument between Buggin’ Out and Pino over the best baseball player becomes a proxy battle for racial pride and recognition. Each character argues for a player of their own race, emphasizing the divide that persists even within universal cultural symbols like baseball. This conversation illuminates the fact that even in areas of shared national identity, racial disparities and the struggle for recognition persist.

In Do the Right Thing , these motifs accentuate the constant struggle for racial recognition faced by the characters. This struggle is not a mere subplot but forms the foundation of the narrative, driving the actions and reactions of the characters. The growing frustration and tension due to this lack of recognition eventually erupt in the film’s climax, manifesting in the form of the riot. The riot, therefore, is not just an act of wanton violence, but a bold assertion for racial recognition, marking a culmination of the characters’ long-standing struggle.

The use of racial slurs

Language plays a pivotal role in Do the Right Thing , serving as a mirror to reflect the simmering racial tension in the neighborhood and offering a critique of the casual prejudice that permeates everyday society.

Throughout the film, characters express their racial prejudices and underlying tensions through their choice of words and phrases, revealing how deeply ingrained these biases are in their everyday interactions. For instance, the loaded conversation between Pino and Mookie about famous African-Americans reveals Pino’s subconscious racial bias. Although he admires several black celebrities, he harbors prejudice against the black community in his immediate vicinity. His words, heavy with contradiction, illustrate how stereotypes and prejudice can coexist with admiration, underscoring the complex nature of racial bias.

A particularly potent example of language reflecting racial tension is the scene often referred to as the “racial slur montage.” Here, characters unleash a flurry of racial slurs against various racial groups, unveiling the raw, unfiltered racial prejudices that exist beneath the surface of their daily interactions. This verbal violence serves as a metaphor for societal tension, laying bare the stereotypes each racial group harbors about the others. By doing so, the film depicts the multifaceted nature of prejudice, where individuals can be both victims and perpetrators of bigotry.

The casual and conversational manner in which these slurs and biased comments are tossed around further demonstrates how racial prejudice has seeped into the fabric of everyday life, often normalized and unchallenged. This habitual use of racially loaded language illustrates how racial tension can simmer beneath the surface of a community, ready to boil over at any provocation.

The need to riot

The riot at the end of the movie is triggered by the unjust death of Radio Raheem, a black man, at the hands of the police. This brutal event resonates with real-world instances where violence against black individuals has sparked widespread public outrage and unrest, such as the murder of George Floyd. The representation of Radio Raheem’s death and the subsequent riot underscores the film’s critique of systemic racism and police brutality, issues that remain pertinent decades after the movie’s release.

The film portrays the riot as an eruption of pent-up racial tension, accumulated resentment, and shared frustration. It is a chaotic, violent, and emotional response to the violence inflicted upon Radio Raheem and, by extension, the black community. The act of Mookie throwing the trash can through the window of Sal’s Pizzeria can be interpreted as an act of deflection, diverting the mob’s wrath from Sal to his property, or as an act of rebellion, symbolically challenging the system that continually marginalizes his community.

In this context, Do the Right Thing is neither justifying nor condemning the riot but presenting it as a complex reaction to a deeply embedded societal problem. The film, instead of simplifying the event into a matter of right or wrong, forces audiences to grapple with the circumstances that lead to such incidents. It challenges viewers to question the structures and biases that perpetuate racial violence and injustice, eventually leading to such outbursts.

Ethics and morality

The theme of ethics and morality runs deep in Do the Right Thing , challenging audiences to grapple with what constitutes “the right thing” in a racially charged context. The film presents various characters wrestling with their moral convictions amidst escalating racial tensions, forcing audiences to reflect on the relativity of moral judgments.

What is the “right thing”?

The advice from Da Mayor to Mookie to “do the right thing” is a significant narrative element that sets the stage for the exploration of ethics and morality in Do the Right Thing . This seemingly simple advice, delivered early in the film, introduces the audience to the complex moral universe they are about to navigate.

By positioning Da Mayor, an older character with life experience, as the deliverer of this advice, the film establishes a sense of generational wisdom. Da Mayor is portrayed as a somewhat flawed but wise figure who has witnessed and understood the complex nature of morality in their racially charged environment. His advice underscores the inherent moral quandaries the characters face and positions him as a moral compass, albeit a nebulous one, as he doesn’t spell out what the “right thing” is.

The phrase “do the right thing” is deceptively simple but inherently complex due to its subjective nature. It presents morality as a fluid concept, shaped by personal perspectives, societal norms, and cultural backgrounds. This leaves room for interpretation, setting the stage for the moral dilemmas that unfold throughout the movie. It allows for multiple interpretations of what the “right thing” is, reflecting the diversity of viewpoints in the neighborhood and the wider world.

The climax of the film, where Mookie throws a trash can through the window of Sal’s Pizzeria, culminates in this theme of moral ambiguity. Mookie’s action can be viewed from different ethical perspectives: as a betrayal of his employer, as a justified act of defiance against a system that devalues black lives, or as a strategic move to redirect the mob’s anger away from Sal and onto his property.

The film does not provide a definitive answer on whether Mookie’s actions constitute “the right thing,” which aligns with the film’s broader approach to ethics and morality. It suggests that morality isn’t fixed or universally agreed upon, but rather a product of individual circumstances, societal influences, and personal interpretations. This approach encourages the audience to engage with these complexities, asking them to consider the factors that shape their understanding of “the right thing.”

Love vs. Hate

Radio Raheem’s “Love and Hate” speech in Do the Right Thing is a pivotal moment that delves into the thematic exploration of ethics and morality. Holding up his brass knuckle-adorned hands, one reading ‘LOVE’ and the other ‘HATE,’ Raheem delivers a dramatic monologue about the eternal struggle between these two forces.

Here’s the entire speech:

This speech is a nod to the dichotomy of good and evil, love and hate that has been a central theme in literature and philosophy for centuries. It introduces the concept of ethical and moral dualism, the conflict between positive and negative moral forces, into the narrative. Radio Raheem’s hands become metaphors for these opposing forces, demonstrating how closely they can coexist and how one’s actions can tip the balance in either direction.

In terms of ethics and morality, this speech underscores the complexity of the characters’ choices and actions throughout the film. The struggle between love and hate is reflected in the characters’ interpersonal dynamics, their actions, and their reactions to the escalating racial tension. It symbolizes the ethical quandaries they face, the choices they make, and the consequences they bear.

For instance, Mookie’s decision to throw a trash can through Sal’s Pizzeria’s window can be viewed through the lens of this dichotomy. Was it an act of hate against Sal, or an act of love to divert the crowd’s anger away from Sal to his property, potentially saving his life? This act, like many others in the film, doesn’t fit neatly into categories of “right” or “wrong,” reflecting the intricate interplay between love and hate, good and evil, ethical and unethical.

Radio Raheem’s speech encapsulates this moral complexity, reminding viewers that actions are often motivated by a mix of love and hate, righteousness and anger, morality and immorality. It reflects the film’s overall stance on ethics and morality, demonstrating that these concepts aren’t clear-cut but rather a product of constant struggle and negotiation between conflicting forces.

Community and identity

Do the Right Thing presents community and identity as intertwined themes, exploring how individual identities contribute to community dynamics and vice versa. The motif of the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, with its diversity, is a melting pot of identities, all coexisting in a delicate balance of harmony and discord.

The tension between community and identity

Do the Right Thing delves into the tension between maintaining individual identity and fostering community harmony, shedding light on the complexity and delicate balance of multicultural societies. Throughout the film, characters grapple with expressing their unique cultural identities while cohabitating a shared community space, revealing the inherent challenges and conflicts that can arise from such a dynamic.

Sal’s Pizzeria serves as a central location for this tension. Sal, an Italian-American, runs this establishment in a predominantly black neighborhood, leading to clashes of cultural expression. The Wall of Fame, adorned with only Italian-American icons, is a clear symbol of Sal’s insistence on maintaining his individual identity. Yet, his pizzeria operates as a communal hub for a black neighborhood, raising questions about representation and the inclusivity of community spaces.

Buggin’ Out’s demand to include black icons on the Wall of Fame exemplifies the tension between individual identity and community harmony. Buggin’ Out seeks acknowledgment of the neighborhood’s cultural identity, believing that the community’s patronage should be reflected in the space they frequent. This is seen as a threat by Sal, who feels his personal identity within his business is being undermined.

The coexistence of community and identity

However, the film does not present this tension as a simplistic binary conflict. Characters such as Da Mayor and Mother Sister demonstrate a more harmonious coexistence of individual identity within the community fabric. Da Mayor, though often at odds with younger community members, ultimately embodies wisdom and peacekeeping. Mother Sister, while maintaining a somewhat aloof and watchful role, shows concern and care for her neighborhood.

The climax of the film underscores the devastating potential of these tensions when left unresolved. The riot that engulfs Sal’s Pizzeria can be viewed as an explosive expression of suppressed individual identities that felt unheard and unrecognized within the shared community space.

At the same time, the film emphasizes the strength of the community. Despite the conflicts, there is a sense of shared experience and mutual support among the residents. The community’s collective outrage at Radio Raheem’s death and the subsequent riot signify a shared sense of injustice and a collective struggle for change. This shared experience, born out of adversity, underlines the power of community and the importance of collective identity in challenging societal structures.

Why is the movie called Do the Right Thing ?

The title Do the Right Thing might appear straightforward, suggesting a simple moral directive to make ethically correct decisions. However, as the film unfolds, it becomes clear that determining what constitutes the “right thing” is steeped in layers of complexity, ambiguity, and subjectivity.

Da Mayor’s directive to Mookie to “do the right thing” early in the film sets the stage for the narrative’s exploration of morality, ethics, and societal pressures. His advice, though seemingly simple, resonates throughout the movie as we observe characters navigating their personal moral landscapes amid escalating tensions. Initially, the quote seems to foreshadow a traditional morality tale where characters will face clear choices between right and wrong, a concept most audiences are familiar with.

The deeper meaning of the title lies in the fact that what may be deemed as “right” is often a matter of perspective. Depending on one’s values, experiences, beliefs, and even their place in a social or racial hierarchy, the definition of the “right thing” can drastically differ. For instance, the character Mookie throws a trash can through the window of Sal’s pizzeria, which, on the surface, is a violent act of vandalism. However, in the context of the story, it can be viewed as an expression of pent-up anger, frustration, and a desperate cry for justice following the death of Radio Raheem. Is Mookie doing the right thing? From his viewpoint, this act was perhaps a necessary measure to draw attention to racial violence. However, to others, his actions might seem destructive and unproductive, potentially escalating the conflict.

By the end of the movie, Da Mayor’s quote takes on a more profound significance. The climactic conflict at Sal’s pizzeria, culminating in Mookie’s act of throwing the trash can through the window and the subsequent riot, forces the audience to grapple with what the “right thing” truly means in such circumstances. Is it peace at the cost of justice, or is it a disruptive act to draw attention to a grave injustice? The ambiguity inherent in Da Mayor’s advice thus becomes a point of reflection for the audience, prompting them to reconsider their understanding of morality and justice.

In the broader context, the title serves as a commentary on systemic racial and social inequalities that still persist in society. It underscores the fact that individuals from marginalized communities often have to navigate a complex moral landscape where the “right thing” may differ vastly from the mainstream narrative. In the face of systemic oppression, their fight for equality might be deemed as an act of defiance, disobedience, or even criminal activity by those in power.

The title’s deeper meaning lies in its challenge to the audience. As viewers, we’re urged to question our notions of what is “right” and “wrong.” We’re prompted to examine our biases, our preconceived notions, and the societal narratives we’ve accepted. This demand for introspection and self-reflection continues to resonate long after the film ends, causing us to grapple with these issues in our own lives.

In Do the Right Thing , heat is a constant presence that accentuates the rising racial tensions. The temperature, which continues to escalate throughout the day, not only aggravates the discomfort and irritability of the characters but also symbolizes their growing frustration and anger. The heat-induced exhaustion and agitation of the characters mirror the societal fatigue that stems from enduring racial inequalities. The film’s climactic riot occurs at the peak of the day’s heat, symbolizing that when tensions, like temperatures, rise too high, a boiling point is inevitable, resulting in an explosive reaction.

Sal’s wall of fame

Sal’s Wall of Fame serves as a constant visual reminder of the racial divide and lack of representation. By exclusively displaying Italian-American celebrities, Sal subtly dismisses the cultural contributions of his predominantly black clientele. This oversight escalates into an issue of contention, leading to the pivotal conflict in the movie. The Wall of Fame is a representation of the cultural erasure and systemic bias faced by the black community. Its destruction during the riot is a symbolic act of rebellion against this exclusion, highlighting the community’s demand for recognition and respect.

Love and hate

The “Love” and “Hate” rings worn by Radio Raheem serve as a metaphor for the societal and personal struggles the characters face. They depict the internal struggle between love, represented by understanding and acceptance, and hate, characterized by prejudice and anger. The symbolic battle between these forces reflects the volatile dynamics within the community. The narrative arc of these rings also mirrors the film’s progression: while Radio Raheem’s monologue about love conquering hate initially offers hope, his death at the hands of the police, a tragic symbol of hate, paints a grim reality.

Music is used in Do the Right Thing to give voice to the community’s struggle. Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” resounds throughout the film, symbolizing the black community’s resistance against systemic oppression. It’s more than just a background score—it becomes a rallying cry that reflects the anger and defiance of the community. This repetition serves as a constant auditory reminder of the unresolved societal issues at hand. The conflict around the volume of Radio Raheem’s radio is also indicative of the clash between individual expression and conformity.

The trash can

The act of Mookie throwing the trash can through the window of Sal’s pizzeria is one of the film’s most iconic scenes. The trash can is symbolic of the pent-up frustrations, racial tensions, and simmering anger within the community. Mookie’s action is not merely an act of vandalism—it is a bold assertion of protest against racial injustice. This act of rebellion, caused by the metaphorical “heat” of the conflict, challenges the status quo and demands immediate attention to the unjust death of Radio Raheem, making the trash can a powerful motif of resistance and call for justice.

Radio Raheem’s radio

Radio Raheem’s boombox serves as an extension of his identity, broadcasting his presence and his defiance against the norms of society. The persistent blare of “Fight the Power” underscores the theme of resistance against racial injustice. When Sal destroys the radio, it signifies a violation of Radio Raheem’s personal space and an outright dismissal of his cultural expression. This act escalates the existing tensions, leading to the climactic confrontation. Therefore, the radio functions not only as a symbol of individual autonomy but also as a catalyst for the events that unfold.

In Do the Right Thing , pizza serves as a symbol of cultural interaction and, paradoxically, cultural division. Sal’s pizza joint, a primarily Italian establishment in the heart of a black neighborhood, becomes a meeting point of cultures. However, Sal’s decision to only honor Italian-American celebrities in a place frequented by mostly black patrons underscores the racial disparities. The pizzas, sold to black customers but representative of Sal’s Italian heritage, also symbolize the economic transaction that doesn’t necessarily translate into cultural respect or understanding, reflecting the real-world dynamic often found in racially diverse urban settings.

The neighborhood

The Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Do the Right Thing is not just a setting—it’s a character in its own right. The neighborhood, with its vibrant mix of racial and ethnic groups, embodies a microcosm of broader societal relationships. The dynamics between the residents, their shared spaces, and escalating tensions serve as a reflection of real-world racial conflicts and complexities. The tight-knit urban setting amplifies the personal and social issues faced by the characters, making the neighborhood a crucial motif in the narrative.

Baseball, as a motif in the film, serves as a conduit to discuss racial tension and cultural pride. The sport, considered a quintessential part of American culture, becomes a battleground to challenge racial representation. The debate between Buggin’ Out and Pino over who the best baseball player is, with each arguing for a player of their own race, exemplifies the struggle for recognition and respect within the same national fabric. This motif underscores the racial divide that persists even within shared cultural experiences.

Police brutality

Police brutality is a recurring motif in Do the Right Thing , symbolizing the systemic violence and racial injustice prevalent in society. The unjustifiable killing of Radio Raheem serves as a stark reminder of this societal issue. The scene of the police car driving away after the act symbolizes the impunity often enjoyed by law enforcement in cases of police misconduct. This motif is a grim commentary on the ongoing struggle against racial discrimination and police brutality, resonating beyond the narrative of the film into real-life societal discussions.

Why won’t Sal put any Black people on the Wall of Fame?

In Do the Right Thing , Sal’s Wall of Fame becomes a focal point of the movie’s racial tension. It prominently features Italian-American celebrities, a fact that Buggin’ Out points out as problematic, given that the pizzeria is situated in a predominantly African-American neighborhood.

Sal’s refusal to put up pictures of black celebrities is a complex issue. It’s not merely an act of racism, but rather, a testament to his personal identity and history. Sal’s pizzeria, including the Wall of Fame, is a microcosm of his Italian heritage, a testament to the figures he admires and identifies with. In a neighborhood that is rapidly changing, it serves as a symbol of stability and tradition, something that he holds onto tightly.

However, this adherence to his tradition comes at the cost of acknowledging the changing demographic of his customer base. His customers are predominantly African-American, and his refusal to represent them on the Wall of Fame could be interpreted as a lack of respect for their culture and contributions.

Sal’s resistance to alter the Wall of Fame is a visual representation of the broader struggle for recognition and representation in the film. It becomes a symbol of racial tension and cultural clash, representing Sal’s unwillingness to fully acknowledge and respect the African-American community that sustains his business. It’s a potent symbol of the unspoken racial divide in the neighborhood, which ultimately escalates to the destructive climax of the film.

Why did Mookie throw the trash can?

Mookie’s act of throwing the trash can through Sal’s pizzeria window is a pivotal moment in Do the Right Thing and has been the subject of much debate. It’s a symbolic act that represents a culmination of the racial tension simmering throughout the film. Mookie’s act of destruction is not necessarily directed at Sal personally, but more towards the system that he sees as responsible for Radio Raheem’s death and the general racial inequality that the community faces.

Several interpretations can be drawn from this moment. Some argue that Mookie is redirecting the crowd’s anger towards property instead of people, possibly saving Sal and his sons from physical harm. Sal’s pizzeria becomes a stand-in for the systemic injustices they’ve been enduring. By targeting the property, Mookie sparks a riot that expresses the community’s rage and grief without directly harming the individuals they’ve associated with the cause.

Others interpret this as Mookie’s personal tipping point, where he can no longer remain neutral amidst the racial tensions. Despite his affiliation with Sal, he identifies more strongly with his community’s anger over Radio Raheem’s death, leading to his drastic action. It’s an act of rebellion against the racial injustices he and his community face, aligning himself firmly with them.

Regardless of the interpretation, this moment underscores the film’s central theme of racial tension and serves as a tangible manifestation of the community’s collective frustration and anger. Mookie’s act is a decisive response to an ambiguous command given earlier in the film: to “do the right thing.”

Now it’s your turn

Have more unanswered questions about Do the Right Thing ? Are there themes or motifs we missed? Is there more to explain about the ending? Please post your questions and thoughts in the comments section! We’ll do our best to address every one of them. If we like what you have to say, you could become part of our movie guide!

Travis is co-founder of Colossus. He writes about the impact of art on his life and the world around us.

Like Do the Right Thing?

Join our movie club to get similar movie recommendations and stories delivered to your inbox every Friday.

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

We hate bad email too, so we don’t send it or share your email with anyone.

Reader Interactions

Write a response cancel reply.

- 1-844-845-1517

- 1-424-210-8369

- PLACE ORDER

- Enron: The Smartest Guys in The Room June 21, 2024

- Security Defence System June 20, 2024

- SLO: Teamwork and Collaboration (Response) June 19, 2024

- Opioids June 18, 2024

DO THE RIGHT THING: AN ANALYSIS

Sample by My Essay Writer

The film shows that it is very difficult for the back people to go about their daily lives with the police authority appearing to keep a discriminatory eye on them. But the dynamic is challenging because when the black people wanted to cool off in the water, the police came and turned it off. It seems as though the black people weren’t malevolent in the film, for the most part, but were just victims of circumstance. I think many people who don’t have air conditioning would support opening up a fire hydrant to cool off on a day that is tempting the 100 degrees Fahrenheit mark. It was just one or two people who decided to turn on the fire hydrant that were the real criminals, but that seemed to paint a dark picture for all of the black people in the neighbourhood, and that type of behaviour led the police to stereotype the black people and fueled much of the hate that they had towards them. This is an example of how the film does a tremendous job at showing how one or two bad apples can spoil the bunch.

Another example is when the police kill Radio Raheem. The black people retaliate by trashing Sal’s pizza restaurant, which a few felt didn’t belong in their neighbourhood because it didn’t have pictures of black people in it. This shows that the behaviour of the police, because they were white, reflected poorly on other white people, and Sal, even though he appeared to like black people most of the time, had to pay the price. Sal’s character showed the conflicting opinions about black people that white people possessed. Sal was in love with his black worker, Mookie’s, sister and he looked at Mookie as a son. However, when Radio Raheem wouldn’t turn his music down when he was in the restaurant, he started saying racial slurs. This shows how magnified the actions of each race was at the time, and when a member of one race did something wrong, it painted a bad picture for everyone belonging to the racial group.

While keeping on the topic of magnification, it is important to note what started the whole ordeal. When Buggin Out gets upset about the fact that there are no pictures of black people on the wall at the pizzeria, he becomes furious and tries to get a boycott going. However, not including a black person on the wall wasn’t meant to be an insult to the community. After all, Sal, as mentioned, loved black people, and all he wanted to do was put pictures on the wall of Italian Americans to reflect his heritage. This was what he had wanted his pizzeria to look like. Taking this small details and turning it into something it was not, is what eventually caused the riot and Radio Raheem’s death. Lee emphasizes this point by having the mentally challenged character put a picture of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King on the wall near the end of the film. The reaction Buggin Out had to there being no pictures of black people on the wall shows the sensitivity that he had and which was present throughout the film with nearly everyone involved. This is explained in “Unthinking Eurocentrism:” “The sensitivity around stereotypes and distortions largely arises, then, from the powerlessness of historically marginalized groups to control their own representations,” (184). But the question about whether Buggin Out was being sensitive is debatable. For example, as “Black Looks: Race and Representation,” points out, “From slavery on, white supremacists have recognized that control over images is central to the maintenance of any system of racial domination” (2).

The film also depicted the various power dynamics that were expressed between the white and black people. White people were usually in positions of power, such as was the position of Sal in the pizzeria, as Mookie was his employee. It was also evident in the police. However, when the white man driving the vehicle through the neighbourhood asked the black people to direct the water from the hydrant in another direction, he was rude to them, and they decided to instead direct the water at him and the vehicle in which he took so much pride. There was a consistent power struggle between the black and the white people, as Mookie continually questioned the authority that was on him. Furthermore, the black people were in control with the white man in the car wasn’t able to get by them without having his vehicle soaked. This shows the building tension that were simmering like the summer heat between the two races.

Also, when the biker accidently stepped on Buggin Out’s shoe and scuffed it, this shows how each culture was essentially walking all over each other, and there was little each could do to stay out of the others’ way. There was so much tension due to the fact that white people actually used black people as slaves at one point, and that there were so many other inequalities that were present with black people throughout the history of the United States. Much of the tension was also based on gentrification. For example, the black people were criticizing the white person for buying a home on their block, and they asked him why he would want to buy a home in a black neighbourhood. They also used the world gentrification when describing what they thought of the man who decided to move into what they considered to be their neighbourhood.

Sal and his son, Vito, weren’t Eurocentric, or feel that their race was somehow superior to the others. The same could be said of the South Korean couple who owned the corner store, although they could have been saying at the end of the film, “I am like you,” just so their store wouldn’t be burned down. Furthermore, Mookie seemed to be very accepting of white people, and wasn’t at all racist, even though he threw a garbage can through the pizza restaurant’s window, which essentially started the riot (However, he was aware the restaurant had insurance). But for the most part, each person depicted in the film felt that their race was superior. This is similar to what is said in “Unthinking Eurocentrism.” For example, the text talks about the typical perception of people who have an opinion on Eurocentrism. This attitude, whether it was by the police or by Sal’s son, or, for that matter, by Radio Raheem, who consistently played “Fight the Power.” Instead, an ethnocentric attitude would be more precise to describe the attitudes of many of the people in the film. However, “Unthinking Eurocentrism” shines an accurate light on the type of perceptions that were evident in the film. “Although Eurocentrism and racism are historically intertwined – for example, the erasure of Africa as historical subject reinforces racism against African-Americans – they are in no way equitable, for the simple reason that Eurocentrism is the ‘normal’ consensus view of history that most First Worlders and even many Third Worlders learn at school and from the media” (3).

Each group felt they had a right to the neighbourhood. The Italian-Americans had been in the neighbourhood for 25 years and they felt they were entitled to stay. The white biker owned a home in the neighbourhood and he thought it was “a free country.” The South Koreans saw a business opportunity and they wanted to serve somewhere, and for whatever reason they decided to open up shop in Brooklyn. Finally, the black people felt it was the only place they could afford to live, and anyone else who moved in were causing gentrification. Each of the relationships look to be appropriate for the time, and this might still be the way things are in that neighbourhood. The film achieved its mission of depicting the challenges, tensions and misunderstandings of each group in the film, and the depiction shows the progress that has been made in race relations throughout Canada.

References Hooks, Bell. Black Looks: Race and Representation . Boston: South End Press, 1992.

Shahat, Ella, and Robert Stab. Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media New York: Routledge, 1994.

Spike Lee, Do the Right Thing. Film, Spike Lee. (1989; Los Angeles: 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks/Universal Pictures, 1989). Film.

- Tags DO THE RIGHT THING: AN ANALYSIS

By Hanna Robinson

Hanna has won numerous writing awards. She specializes in academic writing, copywriting, business plans and resumes. After graduating from the Comosun College's journalism program, she went on to work at community newspapers throughout Atlantic Canada, before embarking on her freelancing journey.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Related Posts

College Essay Examples | March 30, 2022

Marital life Advice To get Wife — How to Make The Marriage Successful

College Essay Examples | May 15, 2023

How The Concept of Production in Finance Adds Value to The Medical Business Field?

College Essay Examples | March 31, 2022

Getting a Foreign Partner

College Essay Examples | May 31, 2024

Writing Assignment 2: The Concepts of Good and Evil Are Obsolete

Begin typing your search term above and press enter to search. Press ESC to cancel.

8 Shockingly Easy Shortcuts to Get Your Essay Done Fast

Free 6-page report.

- Get your essay finished

- Submit your work on time

- Get a high grade

No thanks. I don't want the FREE report.

I’ll risk missing the deadline.

Get that Essay Finished in No Time

Yale University Library

Yale film archive.

- Ask Yale Library

- Your Library Account

- Search the Collection

- Guide to Searching 35mm/16mm

- Streaming Video at Yale

- Film Resources at Yale & Beyond

- Film Studies Research Guide

- Search Library Catalog (Orbis)

- Search Articles+

- Search Worldcat

- Search Borrow Direct

Collections

- Film Collection

- Video Collection

- Screenplay Collection

- Notable Holdings

- Preserved Films

- Copyright Guidance

- Fix Account Problems

- Curricular Support

- Arranging Screenings

- Purchase Request Form

- Clip Capture

- About the Yale Film Archive

- Film Archive Staff

- Hours & Location

- Access & Circulation

- Viewing Facilities

- Food & Drink Policy

- Public Screenings

- Treasures from the Yale Film Archive

- Past Series

- Film Notes: 3 IDIOTS

- Film Notes: A.I.: ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

- Film Notes: AIR FORCE ONE

- Film Notes: THE ADVENTURES OF MARK TWAIN

- Film Notes: ALL ABOUT MY MOTHER

- Film Notes: AMISTAD

- Film Notes: ANTONIA'S LINE

- Film Notes: APOLLO 13

- Film Notes: THE AVIATOR

- Film Notes: BAD EDUCATION

- Film Notes: BARTON FINK

- Film Notes: THE BATTLE OF ALGIERS

- Film Notes: BEING JOHN MALKOVICH

- Film Notes: THE BIG LEBOWSKI

- Film Notes: BLACK AT YALE: A FILM DIARY

- Film Notes: BLACK SWAN

- Film Notes: BOYS DON'T CRY

- Film Notes: BOYZ N THE HOOD

- Film Notes: BRICK

- Film Notes: BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID

- Film Notes: CANDY MOUNTAIN

- Film Notes: CHOCOLAT

- Film Notes: CHINATOWN

- Film Notes: THE CIRCLE

- Film Notes: CITIZEN KANE

- Film Notes: THE CITY OF LOST CHILDREN

- Film Notes: CLASS PICTURES #1

- Film Notes: CLASS PICTURES #2

- Film Notes: CLASS PICTURES #3

- Film Notes: CLASS PICTURES #4

- Film Notes: CLUELESS

- Film Notes: CONSERVATORY WITHOUT WALLS: JAZZ AT YALE AND BEYOND

- Film Notes: CROOKLYN

- Film Notes: CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON

- Film Notes: DAISIES / END OF THE ART WORLD

- Film Notes: DAUGHTERS OF THE DUST

- Film Notes: DESERT HEARTS

- Film Notes: DIRECTED BY YALE WOMEN

Film Notes: DO THE RIGHT THING

- Film Notes: DR. STRANGELOVE

- Film Notes: EIGHT MEN OUT

- Film Notes: EMMA

- Film Notes: THE EMPEROR JONES

- Film Notes: ENCOUNTERS AT THE END OF THE WORLD

- Film Notes: AN EVENING WITH FRANK AND CAROLINE MOURIS

- Film Notes: AN EVENING WITH NICK DOOB

- Film Notes: AN EVENING WITH NORMAN WEISSMAN

- Film Notes: AN EVENING WITH WILLIE RUFF

- Film Notes: EXPERIMENTS IN FRENCH SILENT CINEMA

- Film Notes: FANTASTIC MR. FOX

- Film Notes: FARGO

- Film Notes: FAST CHEAP & OUT OF CONTROL

- Film Notes: FILMS FROM THE HERB GRAFF COLLECTION

- Film Notes: THE FUGITIVE

- Film Notes: THE GODFATHER

- Film Notes: THE GODFATHER, PART II

- Film Notes: GODS AND MONSTERS

- Film Notes: GOOD NIGHT, AND GOOD LUCK.

- Film Notes: GRAND ILLUSION

- Film Notes: HOLD 'EM YALE

- Film Notes: HOME FOR THE HOLIDAYS

- Film Notes: HOUSE OF GAMES

- Film Notes: THE HUSTLER

- Film Notes: IN THE REALMS OF THE UNREAL / MESHES OF THE AFTERNOON

- Film Notes: INDIANA JONES AND THE LAST CRUSADE

- Film Notes: KAPAUKU 1954/55 - 1959

- Film Notes: KATHO UPANISHAD

- Film Notes: THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI

- Film Notes: LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD

- Film Notes: LITTLE MISS SUNSHINE

- Film Notes: THE LIVES OF OTHERS

- Film Notes: LONE STAR

- Film Notes: LOSING GROUND

- Film Notes: M

- Film Notes: THE MADNESS OF KING GEORGE

- Film Notes: MARIE ANTOINETTE

- Film Notes: MEDIUM COOL

- Film Notes: MILDRED PIERCE

- Film Notes: MILK

- Film Notes: MINARI

- Film Notes: MISSISSIPPI MASALA

- Film Notes: MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING

- Film Notes: MY BRILLIANT CAREER

- Film Notes: NOTHING BUT A MAN

- Film Notes: ORLANDO

- Film Notes: PALM SPRINGS

- Film Notes: PAN'S LABYRINTH

- Film Notes: PARIAH

- Film Notes: PASSAGES

- Film Notes: PASSAGES FROM JAMES JOYCE'S FINNEGANS WAKE

- Film Notes: PERSEPOLIS

- Film Notes: THE PIANO

- Film Notes: PRESERVING THE MUSIC OF THE STREETS: TWO BY NICK DOOB

- Film Notes: PRESERVING THE REVOLUTION: JAMES BALDWIN AND THE BLACK PANTHERS

- Film Notes: PRINCESS MONONOKE

- Film Notes: UN PROPHÈTE

- Film Notes: THE PURPLE ROSE OF CAIRO

- Film Notes: RACHEL GETTING MARRIED

- Film Notes: REAR WINDOW

- Film Notes: REBEL WITHOUT A CAUSE

- Film Notes: RUN LOLA RUN

- Film Notes: THE SCENT OF GREEN PAPAYA

- Film Notes: SCHOOL OF ROCK

- Film Notes: SHADOW OF A DOUBT

- Film Notes: SMOKE SIGNALS

- Film Notes: SPEED RACER

- Film Notes: SPRING, SUMMER, FALL, WINTER...AND SPRING

- Film Notes: A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE

- Film Notes: SUNSET BLVD.

- Film Notes: TERMINATOR 2

- Film Notes: THE THIRD MAN

- Film Notes: THE THIN RED LINE

- Film Notes: THREE KINGS

- Film Notes: TO BE A MAN

- Film Notes: TO CATCH A THIEF

- Film Notes: THE TRAIN

- Film Notes: THE TRIPLETS OF BELLEVILLE

- Film Notes: THE UNTOUCHABLES

- Film Notes: VENGEANCE IS MINE / THE PLOT AGAINST HARRY

- Film Notes: VERTIGO

- Film Notes: LA VIE EN ROSE

- Film Notes: VOLVER

- Film Notes: WADJDA

- Film Notes: WAITING FOR GUFFMAN

- Film Notes: WANDA

- Film Notes: WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT KEVIN

- Film Notes: THE WEDDING BANQUET

- Film Notes: WHAT TIME IS IT THERE?

- Film Notes: WHEN WE WERE KINGS

- Film Notes: THE WIZARD OF OZ

- Film Notes: WITHIN OUR GATES

- Film Notes: YALE COLLECTION OF CLASSIC FILMS

- Film Notes: YI YI: A ONE AND A TWO...

DO THE RIGHT THING, 30th Anniversary Screening 7 p.m. Thursday, September 19, 2019 53 Wall Street Auditorium Co-presented with the Democracy in America film series; introduction by Matthew Jacobson and Michael Kerbel; post-screening discussion with Daphne Brooks, Aimee Cox, and Daniel HoSang Film Notes by Michael Kerbel PDF

Written, produced, and directed by Spike Lee (1989) 120 mins Cinematography by Ernest Dickerson Produced by Universal Pictures Starring Danny Aiello, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Richard Edson, Giancarlo Esposito, Spike Lee, Bill Nunn, John Turturro, Paul Benjamin, Frankie Faison, Robin Harris, Joie Lee, Samuel L. Jackson, Rosie Perez, John Savage, Roger Guenveur Smith, Martin Lawrence, Steve Park, and Frank Vincent

Like many other Spike Lee “joints,” DO THE RIGHT THING–which opened in the U.S. on June 30, 1989–incisively depicts America’s continuing problems with race. The film examines the complex and uneasy racial dynamic of a predominantly black neighborhood that still feels the effects of the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. Lee views this from three perspectives: that of languid older residents who lived through that era, that of a disjointed and floundering younger generation, and that of a white Italian-American family whose pizzeria has served the neighborhood for 25 years, but who live elsewhere.

Lee dedicated the film to the families of six black people who died as a result of racism and/or police actions during the previous decade. Lee: “I wanted the film to take place in one day, the hottest day in the summer. And I wanted to reflect the racial climate of New York City. The day would get longer and hotter, and things would escalate until they exploded.” An immediate motivation was to “dump Koch,” the mayor whose 12-year administration had seen major racial conflicts, and whose opponent in the upcoming Democratic primary was a black man, David Dinkins. (Dinkins prevailed, and went on to become the city’s first black mayor.)