A complex God: why science and religion can co-exist

Associate Professor of Physics, The University of Melbourne

Disclosure statement

Associate Professor Martin Sevior receives ARC funding to conduct experiments in fundamental particle physics at the KEK National accelerator Laboratory in Japan and the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, Switzerland. He is also an Elder and the congregation chair of St. Columbas Uniting Church in Balwyn, Victoria. This essay grew out of a series of lectures on the topic of "Intelligent and Intelligible Design" delivered at St. Columbas in 2008 with Professor Emeritus Reverend Harry Wardlaw, also of St. Columbas. Martin gratefully acknowledges many fruitful conversations with Harry.

University of Melbourne provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Science and religion are often cast as opponents in a battle for human hearts and minds.

But far from the silo of strict creationism and the fundamentalist view that evolution simply didn’t happen lies the truth: science and religion are complementary.

God cast us in his own image. We have free will and intelligence. Without science we could only ever operate at the whim of God.

Discussion of the idea that our universe is fundamentally intelligible is even more profound. Through science and the use of mathematical rules, we can and do understand how nature works.

The fact our universe is intelligible has profound implications for humankind and perhaps for the existence of God.

Does science work?

It’s very clear that science “works”. We can explain and predict how nature will behave over an extraordinary range of scales.

There are various limits to scientific understanding but, within these limits, science makes a complete and compelling picture.

We know that the universe was created 13.7 billion years ago. The “Big Bang” model of universal creation makes a number of very specific and numerical predictions which are observed and measured with high accuracy.

The Standard Model of Particle Physics employs something known as “Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking” to explain the strength of the laws of nature.

Within the Standard Model the strength of these laws are not predicted. At present our current best theory is that they arose “by chance”.

But these strengths have to be exquisitely fine-tuned in order for life to exist. How so?

The strength of the gravitational attraction must be tuned to ensure that the expansion of the universe is not too fast and not too slow.

It must be strong enough to enable stars and planets to form but not too strong, otherwise stars would burn through their nuclear fuel too quickly.

The imbalance between matter and anti-matter in the early Universe must be fine tuned to 12 orders of magnitude to create enough mass to form stars and galaxies.

The strength of the strong, weak and electromagnetic interactions must be finely-tuned to create stable protons and neutrons.

They must also be fine-tuned to enable complex nuclei to be synthesized in supernovae.

Finally the mass of the electron and the strength of the electromagnetic interaction must be tuned to provide the chemical reaction rates that enables life to evolve over the timescale of the Universe.

The fine tuning of gravitational attraction and electromagnetic interactions which allow the laws of nature to enable life to form are too clever to be simply a coincidence.

Is intelligent life special?

It has taken 4.5 billion years for humans to evolve on earth. This is more than 25% of the age of the universe itself.

We are the only intelligent life that has existed on the planet and we have only been here for 0.005% of the time the planet has been here.

This is a mere blink in the age of the galaxy. If some other intelligent life had emerged elsewhere in the galaxy before us, why haven’t we seen it here?

To me this is a strong argument that we are the first intelligent life in the galaxy.

Designed for life

One interpretation of the collection of unlikely coincidences that lead to our existence is that a designer made the universe this way in order for it to create us; in other words, this designer created a dynamic evolving whole whose output is our creation.

Many take exception to this idea and argue instead that our universe is but one of an uncountable multitude that has happened to create us.

Other ideas are that there are as-yet unobserved principles of nature that will explain why the strengths of the forces are as they are.

To me, neither argument is in principle against an intelligent design.

The designer is simply clever enough to have devised either an evolving multitude of universes or to have devised a way to make our present universe create us.

Intelligible Design

We do know a lot about the design of the universe, so clearly the design is in good measure intelligible.

But why is it that we can understand nature so well?

One answer is that evolution favours organisms that can exploit their environment. Most organisms have a set of “wired” instructions passed from earlier generations.

Over the evolutionary history of Earth, organisms that can learn how to manipulate their surroundings have prospered.

Humans are not unique in this trait but we’re definitely the best at learning. So in other words nature has built us to understand the rules of nature.

Mathematics and science

All of this rests on the predictability which results from nature obeying rules. As we’ve learned about these rules we’ve discovered that they can be expressed in purely mathematical form.

Mathematics has a validity that is independent of its ability to describe nature and the universe.

One could imagine mathematics with its complex relationships being true outside of our universe and having the ability to exist outside it.

The outcome of humankind’s investigations into nature is science. And the fundamental tenet of science is that there is an objective reality which can be understood by anybody who is willing to learn.

A universe without laws?

The only way I can imagine a universe without rules is for every action to be the result of an off-screen director who controls all.

Such a thing is almost beyond comprehension as everything would need to be the result of premeditation.

Events would appear to occur by pure random chance. Furthermore the level of detail required for godly oversight is absolutely beyond human comprehension.

Each of the hundreds of billions of cells in our bodies operates within a complex set of biochemical reactions, all of which have to work individually and as well as collectively for just one human body to function.

So for a start our offscreen director would have to ensure that all these processes happen correctly for every one of the trillions of living organisms on earth.

We are all the stuff of the universe, absolutely embedded within, and subject to, the rules which govern nature. Because we’re self-aware, one can argue that the universe is self-aware.

Without an intelligible design it would be impossible for humans to have free will as all actions would be as a consequence of the will of the director. Free will is a fundamental element of Christian doctrine.

The Christian statement “God made man in His own image” implies both free will and intelligence for humans. Intelligible design is thus a necessary condition for the existence of a Christian God.

Given we are intelligent, we can imagine sharing this aspect with a God who made us in “His own image”.

Free will is only possible in a universe with rules and hence predictability.

Intelligence has application beyond our physical universe – which is indicative, but not proof of, God to me.

On the other hand, the existence of a God providing free will to humans requires the existence of science.

Otherwise we could only ever operate at the whim of God.

Science and religion go hand in hand.

We all know the subjective reality of experience. I personally feel the power of the redemption which is at the core of Christianity.

Each of us has access to that through our own free will to exercise choice.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Reverend Jim Martin.

Are science and religion compatible? Leave your views below.

- Science and religion

- Intelligent design

Research Process Engineer

Laboratory Head - RNA Biology

Head of School, School of Arts & Social Sciences, Monash University Malaysia

Chief Operating Officer (COO)

Data Manager

- Adventist Review

Science and Faith, Hand in Hand

What God teaches us through science and engineering

Science and faith went hand in hand for centuries, as numerous pioneers of mathematics and science were devout Christians, including Kepler, Pascal, Mendel, Kelvin, and Carver. They would have affirmed what David wrote: “The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament shows His handiwork” (Ps. 19:1). These scientists saw study of the laws of nature as an expression of their faith, like an act of worship.

Today talk about God and science gets clouded by evolution or cosmology, though I consider these in the category of empirical models of the past, rather than the scientific method of repeatable experiments.

PERSONAL TESTIMONY

In my own life the faith-science nexus has brought meaning and focus, personal development, ethics, and humility. As an engineering professor, I use targeted experiments to solve a problem. My own work at the intersection of materials, mechanical and chemical engineering, focuses on metal production and energy generation, conversion, and storage for greenhouse emissions reduction, elimination, or drawdown. Indeed, my focus on this topic is based in large part on my faith as a way to use my gifts to address an urgent problem.

The most direct intersection between my faith and work comes when I pray for insight. This is clearest when my own effort fails, as prayer clears my mind and focuses me, and humbles me. In one situation, after a conference presentation in which I had results only by God’s grace, an audience member approached me and asked whether I was Christian—he said that he could see humility in my demeanor, humility that had come from seeing God’s power in my weakness (cf. 2 Cor. 12:9).

Faith has also led me to prioritize people and their development. I often encourage students to change to a different institution or research group after completing a degree or milestone to further their careers, when my research might benefit more if they kept working with me. Again, this is not unique to science; all of us can and should promote the interests of those around us.

More specific to science, being at the forefront of a discipline, however narrow that discipline is, helps one see how much we don’t know and will likely never know. Harvard’s original crest had one of its three books facedown to represent the limits of reason, and the need for God’s revelation. Two hundred years after its design, Harvard turned the third book forward, as in 1843 its regents saw rapid progress in science and believed that all knowledge had either been revealed or soon would be. Because nearly all compulsory science education and media coverage of technology focus on settled facts and accomplishments, it is hard for many to understand limits and uncertainty.

PUTTING THEORY INTO PRACTICE

But it is even more humbling when people don’t act based on well-established knowledge, like the buried talents referenced by Jesus (Matt. 25:14-30), or Psalm 127. For example, in the COVID pandemic, United States scientists learned quickly about the virus and developed the first and most effective vaccines. But mixed messaging hobbled prevention efforts, and the infection rates and excess death rate of the United States dwarfed many significantly less developed economies.*

It is similar in my field of climate mitigation, where the United States is humbled by Norway’s switch to electric vehicles—many made in the USA; and even more by Bhutan and Costa Rica, which already are or soon will be carbon-neutral.

As a high school student, I verbalized this dichotomy between technology and its useful deployment. As an engineer, I wanted to help solve the world’s “little problems,” which I listed as:

- agriculture, to feed a growing planet;

- medical research, allowing people to lead longer, healthier lives;

- human interactions with the environment, for sustainable development;

- information access, as the biggest enemy of a dictator is the truth.

All of these are important, but if scientists and engineers do our jobs well, we help the artists, economists, social workers, church leaders, and politicians to address the “big problems,” which I listed as:

- peace between nations, and security in our neighborhoods;

- averting and mitigating famines;

- education to build agency and confidence, particularly for the marginalized;

- health care for those who need it most;

- justice, including fair economic distribution;

- truth in journalism and history;

- purpose and meaning for our lives, and artistic expression of that purpose and meaning;

TOLERANCE OF DIFFERENCES

An important consequence of this understanding of “little problems” and “big problems” is that being a scientist or engineer requires faith that our work will be used for good and not for evil. Even if we don’t work on nuclear science or weaponry, the events of September 11, 2001, showed that even if one focuses on nonmilitary technologies, a civilian jetliner— built to bring people together—can be abused, by people with sufficient hatred, as a weapon of mass destruction. This frightened me as an engineer, and I believe it requires us to have more faith in the people, institutions, and systems surrounding technology.

I would rather live in a world in which we solve the big problems but not the little ones—one with democracy, but also challenges with energy or nutrition, rather than the other way around, as in fascism or in dark visions of technological perfection. This doesn’t mean that work in STEM (science, technology, engineering , and math) doesn’t matter. Rather, it’s an enabler: new technology can dramatically reduce the impact of a pandemic, and the cost of reducing climate emissions. With economic incentives and research and development funding , wind and solar energy prices fell by 75 percent and 90 percent, respectively, from 2007 to 2019.

Thus we continue to explore God’s creation, more vast than even our imaginations can fathom. And we work hard to use God’s gifts of material and knowledge to fashion tools for improving each other’s lives. But we are humbled by our limitations, and must remain open to considering that what we think we know could be wrong. This openness is the essence of scientific pursuit, of engineering design, and of the Christian walk, as they go forward hand in hand.

* See https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2021/05/27/covid-19-is-a-developing-country-pandemic/ .

Adam Clayton Powell IV

Adam Clayton Powell IV, associate professor of mechanical engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, focuses on new zero-emissions technologies for aviation, etc. He is treasurer of Boston Temple Seventh-day Adventist Church and lives in Massachusetts, United States.

Related Posts

‘Here I Am—Send Me’

In Portugal, Ukrainian Family Finds Shelter in Adventist Businessman’s Home

Care in a Crisis

Evangelistic Plan Inspires Hispanic Ministries Coordinators

Being Connected to Christ

Maranatha Builds Dorm and Water Well for Kenya Rescue Center

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

Contact Information

© 2017 Adventist World

- Past Issues

- Prayer Request

How religion and science can go hand in hand: Opinion

- Published: Jun. 21, 2014, 9:00 p.m.

- Star-Ledger Guest Columnist

evolution.JPG

Scientists have proved evolution -- meet this model of Homo floresiensis, who roamed the planet some 50,000 years ago -- exists in the world, which people of religion should accept. Likewise, people of science should accept that people have religious faiths.

(2010 Washington Post file photo)

By Gerald L. Zelizer

So what do we religious folk say about the 42 percent who believe — according to a recent Gallup poll — that God created humans in their present form 10,000 years ago?

That creationist position has practical implications. Even our governor in 2011, when asked if he believed in creationism responded, “That is none of your business.” Actually, it is our business — the business of local school districts that have the option, if they choose, to teach creationism along side of evolution. This has already been mandated by some districts throughout the country.

There are lots of religious folk like me, constituting the other 58 percent who accept scientific explanations of the origins of the universe while simultaneously affirming their faith in many cases. That is because science and religion have two different functions.

Science explores the how of life. It utilizes the scientific method of observation to understand the mechanism by which things are as they are. Religion explores the why of life — not how things are, but why things are. Each faith searches for meaning, not mechanics, in life, death and our relationship to others and the world. Science cannot tell us why, only how. Religion cannot tell us how, only why.

So, for example, in the creation vs. evolution debate, if science says that evolution most fits the observable facts, then that is the truth, not creationism. By the same token, the first chapters of Genesis repeat after each day, “And God saw that it was good.” The religious truth of creation is that because the world is divine, it is worth preserving and not squandering.

Many secular folk beat up on religion by aiming at only the 42 percent. For example, Bill Maher, the political satirist and a consummate atheist, recently interviewed the politically active, Biblical literalist Ralph Reed. Maher's challenge was that, if the Bible is literally the word of God, why does it seem to accept issues such as slavery, stoning an adulterous woman, and genocide of the Canaanites — children included? Reed's answer was that those kinds of orders from God were part of the Old Testament, while Jesus in the New Testament upgraded the Old. To which Maher snapped, "So why did Jesus come along to correct his dad?"

As a believer who is a nonliteralist, I would have answered differently. Sure, the Bible, in addition to containing spiritually uplifting passages including “Thou shall not murder,” also includes spiritually degrading arguments, such as advocating slavery. That is because both the Hebrew and Christian Bibles are not the actual, literal words of God, conveyed as through a recording device, but the transmissions of human scribes, giving their impressions of what God expected of humankind.

That is why there are inconsistencies and contradictions in so much of the Bible. So for example, to Maher’s challenge that slavery was condoned in the Bible, I would have pointed to the later Prophets who instead emphasize the shared humanity of all races and classes. The sacredness of the Bible evolves.

There are many people of faith like me. For example, this year’s Laetare Medal of Notre Dame University was given to Kenneth R. Miller, professor of biology at Brown University, author of “Finding Darwin’s God: A Scientist’s Search for Common Ground Between God and Evolution.” Miller said: “The second great myth about science holds it to be the antithesis of faith. This is a myth that serves both the enemies of faith and science very well … . Such assertions ignore the very history of western science, which has its roots in a faith that views the study of nature and its mysteries as a way to praise and understand the glory of God.”

He cites Isaac Newton as an example and points out that science too has its own faith-based system: “All science proceeds on the assumption that nature is ordered in a rational and intelligible way ... a faith that would require one to reject scientific reason is not a faith worth having.”

So let’s put to bed the assumed antagonism between scientific and religious truth. They work distinctly and in tandem. Religious folk should accept scientific truth as “gospel” and secular folk should accept religious truth as “attributing meaning beyond the how.”

Do I expect the 42 percent who are Biblical literalists to forsake their belief in the creation of the world in six days and embrace scientific accounts? No. Do I expect scientists to relinquish their dire warnings of the planet’s demise resulting from we humans releasing too much carbon into the atmosphere, because the Bible says that man’s right is to “rule” the rest of God’s kingdom? Certainly not.

Both the Reeds and the Mahers of the world will never do that. But for the rest of us in the 58 percent, let’s publicly refute the assumed conflict between scientific and religious truth that we hear from many vocal atheists and religious fundamentalists. Once we acknowledge and disseminate these separate and distinctive functions, then an even more substantive conversation can follow on the details, which sometimes separate the two camps — such as birth control, homosexuality and global warming.

In the Gallup poll, 47 percent responded that the Bible is the inspired word of God, but not everything in the Bible should be taken literally. Nearly 1 in 3 responded that humans evolved with God’s guidance.

Hurray for those who blend religion and science. Let us set the tenor and agenda for this discussion of religion and science.

Gerald Zelizer is rabbi of Cong Neve Shalom in Metuchen: [email protected].

FOLLOW STAR-LEDGER OPINION: TWITTER • FACEBOOK

If you purchase a product or register for an account through a link on our site, we may receive compensation. By using this site, you consent to our User Agreement and agree that your clicks, interactions, and personal information may be collected, recorded, and/or stored by us and social media and other third-party partners in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.82(1); February, 2015

The harmonious relationship between faith and science from the perspective of some great saints: A brief comment

Manuel e. cortés.

1 Departamento de Ciencias Químicas y Biológicas, Universidad Bernardo O'Higgins, Santiago, Chile

2 Reproductive Health Research Institute, Santiago, Chile

Juan Pablo del Río

3 Escuela de Medicina, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Los Andes, Santiago, Chile

Pilar Vigil

4 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

The objective of this editorial is to show that a harmonious relationship between science and faith is possible, as exemplified by great saints of the Catholic Church. It begins with the definitions of science and faith, followed by an explanation of the apparent conflict between them. A few saints that constitute an example that a fruitful relationship between these two seemingly opposed realities has been possible are Saint Albert the Great, Saint John of the Cross, Saint Giuseppe Moscati, and Saint Edith Stein, among others, and this editorial highlights their deep contributions to the dialogue between faith and reason. This editorial ends with a brief discussion on whether it is possible to be both a scientist and a man of faith.

Introduction

In the current academic scene, it is quite common to hear of the alleged conflict and incompatibility between science and faith, between being a scientist and being a believer. Any scientist interested in establishing a dialogue with the world of faith would probably be frowned upon. The present editorial aims at showing that a harmonious, complementary, and productive coexistence between faith and true science (the one guided by reason) has indeed been possible—and is still possible in the present day. Such fruitful coexistence is exemplified by the remarkable work of some important saints and intellectuals of the Catholic Church who have made significant contributions to theology, philosophy, natural science, medicine, and bioethics.

A Definition of Science

Let us begin by establishing what is meant by the term “science.” Science 1 is a human activity aimed at acquiring a reliable knowledge of the causes and principles of things ( Cortés and Alfaro 2013 ). Science results from man's attempt to understand the natural world, comprehend the universe to which he belongs, and thus explain to himself his longing for transcendence. Hence, man seeks to satisfy his need to immerse himself in the world, reveal the unknown, and conquer it ( Cortés and Alfaro 2013 ). From this perspective, science and faith share the same fundamental concerns: the intimate wish to comprehend the infinite, be part of it, and decipher the role man plays in it. According to Aristotle, man's admiration for all that surrounds us would account for the search for knowledge; in this wider sense, science should be understood as natural philosophy.

A Definition of Faith

In line with our approach, we must now define “faith” 2 ; before doing so, one has to first accept an anthropology that acknowledges the presence of levels in man beyond the purely material levels. That is, it is necessary to assert the spiritual and transcendent dimension of man. This dimension connaturally implies a deep yearning for eternity, embodied in the search for Truth through the intellectual powers of man: memory, understanding, and will (cf. Aquinas 1947 ). We are especially concerned here with the power of understanding, where new life is given to intellectual pursuit, the one science is concerned with.

Saint John of the Cross (1542–1591), Doctor Mysticus , defines faith from an ontological and dynamic perspective as the supernatural means to achieve union of the understanding with God, enabling this power to participate in Divinity ( John of the Cross 2009 ; Wojtyla 1979 ). This means that through the free action of faith it is possible to walk toward a truth that transcends ourselves; faith itself, through the discovery of and participation in creation, leads us to this truth. According to Saint John of the Cross, faith does not deny the power of understanding, but rather, it raises it to its full potential so it can contemplate the mystery of the created ( John of the Cross 2009 ).

The Alleged Conflict between Science and Faith

In Carroll's ( 2003 ) words, science and faith in relation to one another should have been twin pillars of civilization. However, such a relationship is not as evident for the current scientific community. The reason for this would be that Descartes's statement “I think, therefore I am” ( Je pense, donc je suis , Descartes 1637 ), which constitutes a fundamental element to Western rationalism, has been misinterpreted by many scientists from the Enlightenment to our times, reducing human nature to mere intelligence, and thus, reducing him to an object. In fact, Saint John Paul II made extensive reference to the tragic division between faith and reason which originated with the emergence of modern science and lasts to the present day:

Particularly, beginning in the Enlightenment period, an extreme and one-sided rationalism led to the radicalization of positions in the realm of the natural sciences and in that of philosophy. The resulting split between faith and reason caused irreparable damage not only to religion but also to culture. ( John Paul II 1999 )

Hence, the apparent conflict and incompatibility between science and faith came to serve as a basis for two broadly antagonistic positions: on the one hand, a strict rationalism, reductionist to the point of not acknowledging the spiritual nature of the human being, thus denying its sense of transcendence. This can be exemplified in the opinion of Nobel laureate Francis C. Crick, one of the discoverers of DNA structure in 1953, who stated:

You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules. ( Crick 1994 )

And, on the other hand, we have creationism, a set of beliefs based on which the Earth and every current living being originated in an action of creation performed by one or more divine entities according to a divine intention ( Hayward 1998 ). Thus, most pseudoscientific and religious movements subscribing to creationism go against the theory (or theories) of evolution ( Ayala 2007 ). Hence, fundamentalists and creationists (not identical) have proposed that creationism be taught in school science class as a valid alternative to evolution ( Yahr 2008 ). This stream of thought denies part of the physical reality of creation. In view of the above, it is necessary to bear in mind Saint John Paul II's clear reference to this dichotomy in his Encyclical Letter Fides et ratio :

I make this strong and insistent appeal that faith and philosophy recover the profound unity which allows them to stand in harmony with their nature without compromising their mutual autonomy. ( John Paul II 1998 )

Hence, the apparent contradiction between pure materialism and creationism is a dissociation of faith and reason taken to the extreme. In contrast, a productive and enlightening relationship between faith and reason has constituted a striking feature of some remarkable Christian thinkers, as is briefly commented below.

Some Great Saints as Examples of Fruitful Coexistence between Faith and Reason

First, we will refer to Saint Albert the Great (1206–1280), Doctor Universalis and “patron saint of natural scientists” ( Ortega 2010 ), whose humility and selfless intellectual endeavors served as an inspiration for a number of disciples, among them Saint Thomas Aquinas. His many contributions include his proposal that the Earth was round, a detailed description of plant morphology and, in the field of chemistry, the discovery or the element arsenic (cf. Ortega 2010 ; Reed 1980 ; Valderas 1987 ). Another intellectual possessing deep spirituality was the Italian physician Saint Giuseppe Moscati (1880–1927), a prominent figure both for his pioneer work in physiological biochemistry (particularly the study of reactions involved in glycogen transformation) ( Moscati 1906 1907 ), and for his integration of faith and reason, as particularly expressed through his disinterested work with the poor and incurably ill patients. He personally looked over the “incurabili” (incurable) patients in the hospital, where he remained stationed for several years. While taking care of the ill, Moscati never stopped doing research, balancing science, and faith. Edith Stein (1891–1942), also known as Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, co-patroness of Europe, was a German Carmelite who participated prominently in the dialogue between science and faith. Initially an atheist philosopher ascribing to phenomenology, following a long discernment period she entered religious life and devoted herself to deeply spiritual and philosophical writings, among them The Structure of the Human Person ( Stein 2003 ). Stein reaches the conclusion that “he who seeks the truth, whether aware of it or not, seeks God”; according to Stein, for philosophy, the meaning of faith is twofold:

if through faith a truth is reached that cannot be accessed by any other means, philosophy cannot deny such facts of faith without relinquishing its claim as universal truth, and moreover, without risking its inherent knowledge being tainted by error; due to the organic interdependence of truth, if separated from the core, any partial aspect of it will be poorly illuminated. Hence the material dependence of philosophy on faith. Therefore, if man's highest certainty is inherent to faith, and if philosophy intends to provide the highest accessible truth, it has to take ownership of faith. Such is the case when it accepts in itself the truths of faith, and even more, analyzes all other certainties in the light of such truths of faith, as the ultimate criterion. This also accounts for a formal dependence of philosophy on faith. ( Stein 1993 )

Given her Jewish origin and her allegiance to the teachings of Jesus Christ, Edith Stein died a Catholic martyr in Auschwitz concentration camp.

Concluding Remarks

In the light of the foregoing, the work of these saints shows us that it is possible to overcome scientific reductionism, which is based on a misinterpretation of “I think, therefore I am.” Such reductionism goes totally against the integral nature of the human person where the spiritual component is an essential part. Along the same line, an absolute creationism will focus exclusively on man's spiritual component, denying the possibility of finding the truth by contemplating creation through understanding. Both should be replaced by a much broader perspective integrating the communion between science and faith, and also between body and soul. In our personal opinion, the life and work of the aforementioned saints constitute a proof that shows us that it is possible to be an intellectual devoted to both science and faith, and that no contradiction exists between both when truth is genuinely sought; on the contrary, faith and reason are mutually supporting. In this way, the natural sciences collaborate with theology, and theology collaborates with the natural sciences ( Vicuña 2002 ). As way of synthesis, it is always worth remembering the words of Saint Augustine of Hippo, subsequently restated by Saint Anselm of Canterbury, credo ut intelligam et intelligo ut credam , i.e., we believe in order to understand and we understand in order to believe.

Biographies

Dr. Manuel E. Cortés is professor of physiology and physiopathology at the Departamento de Ciencias Químicas y Biológicas, Universidad Bernardo O'Higgins, Santiago; and a post-doctoral researcher at the Reproductive Health Research Institute (RHRI), Santiago Chile.

Juan Pablo del Río is currently pursuing a degree in medicine and surgery and studying philosophy at the Universidad de los Andes, Santiago, Chile.

Dr. Pilar Vigil is associate professor at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, and medical director of the RHRI, Santiago, Chile. In addition, Dr. Vigil is a member of the Ponfical Academy for Life, Vatican City, and president of Teen STAR International. The authors wish to thank Miss Isabella Montero for her useful comments about this editorial. The authors may be contacted through Dr. Manuel E. Cortés, Departamento de Ciencias Químicas y Biológicas, Universidad Bernardo O'Higgins, General Gana 1702, Santiago, Chile. Email: [email protected]

1 Science, from the Latin scientia , means knowledge, which comes from the verb scire , to know (cf. Eto 2008 ). However, the origin of the term “science” dates back to the Indo-European term skei , referring to the capacity to cut or separate one thing from another to distinguish them. Thus, from an epistemological and historical point of view, from ancient times science has been closely linked to identifying one thing as separate from the other in order get to know it.

2 Etymologically, “faith” comes from the Latin fidēs , a term related to the Proto-Indo-European *b h eyd h , that means “to trust.”

- Aquinas, Saint Thomas. 1947. Summa Theologica . North Carolina: Hayes Barton Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ayala F.J.2007. Darwin y el Diseño Inteligente . Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carroll W.E.2003. La Creación y las Ciencias Naturales. Actualidad de Santo Tomás de Aquino . Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cortés M.E. and Alfaro A.A.. 2013. Sobre los fundamentos epistemológicos e históricos de la ciencia: algunas reflexiones . Revista Chilena de Educación Científica 12 : 49–57. [ Google Scholar ]

- Crick F.1994. The astonishing hypothesis: The scientific search for the soul . New York: Scribner. [ Google Scholar ]

- Descartes R.1637. Discours de la Méthode pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la vérité dans les sciences . Leiden: Ian Maire. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eto H.2008. Scientometric definition of science: In what respect is the humanities more scientific than mathematical and social sciences? Scientometrics 76 : 23–42. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hayward J.L.1998. The creation/evolution controversy: An annotated bibliography . Lanham: Scarecrow Press/Salem Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- John of the Cross, Saint. ed. 2009. Subida al Monte Carmelo . In Obras Completas San Juan de la Cruz , 151–432. Madrid: Editorial de Espiritualidad. [ Google Scholar ]

- John Paul 1998. Faith and reason: Encyclical letter Fides et ratio of the Supreme Pontiff John Paul II to the bishops of the Catholic Church on the relationship between faith and reason . Washington, DC: Veritas. [ Google Scholar ]

- John Paul 1999 Address at meeting with rectors of academic institutions, Torun, Poland, June 7, 1999. http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/travels/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_07061999_torun_en.html .

- Moscati G.1906. La salda d'amido iniettata nell'organismo nota 2: Ritenzione dell'amido e trasformazione in glicogeno: ricerche sperimentali del Dott. Giuseppe Moscati . Atti della R. Accademia Medico-Chirurgica di Napoli 2 : 1–12. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moscati G.1907. Il glicogeno nella placenta muliebre andamento e meccanismo della sua scomparsa dopo l'emissione. Valore medico legale: ricerche sperimentali del Dott. Giuseppe Moscati . Atti della R. Accademia Medico-Chirurgica di Napoli 2 : 1–11. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ortega L.2010. Alberto Magno: Patrón de los Científicos . Revista de Química PUCP 24 : 26–30. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reed K.1980. Albert on the natural philosophy of plant life . In Albertus magnus and the sciences: Commemorative essays . ed. J.A. Weisheipl, 341–5. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stein E.1993. Erkenntnis und Glaube . Freiburg: Herder. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stein E.2003. La Estructura de la Persona Humana . Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos. [ Google Scholar ]

- Valderas J.M.1987. Anatomía vegetal en San Alberto Magno . Collectanea Botanica (Barcelona) 17 : 125–34. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vicuña R.2002. Las ciencias naturales colaboran con la teología . Teología y Vida 43 : 53–73. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wojtyla K.1979. La Fe Según San Juan de la Cruz . Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yahr M.G.2008. ¿Hay o no “diseño inteligente” en el origen de la vida? Es esta una controversia científica? Interciencia 33 : 165–6. [ Google Scholar ]

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

science, religion can walk hand in hand

We have been told that we can be people of faith or people of science, but we can't be both. That was historically not the case, and need not be the case today.

Related Papers

The Statesman

Govind Bhattacharjee

Religion has become corrupted and lost all its divinity. It is now for science to redeem it.

International Journal of Sciences

Graham Nicholson

“Many thanks for the video tape of your interview, which was provocative and (for most viewers I’m sure, uncomfortably) close to the mark. It’s hard to get frank talk on the relation of science and religion started, but it’s worth a few bumps and knocks to get it started.” Edward O Wilson—Professor Harvard University and Evolutionary Biologist

The Humanist

Josh Cuevas

Science progress

Taner Serdar

There is a widespread assumption that science and religion are incompatible with each other; it may be acceptable for a scientist to practise religion, but--it is believed--this should be seen as despite, not because of his or her scientific profession and knowledge. Such an assumption is wrong. Examination of conflicts between science and religion (such as those about evolution) show that they always arise through misinterpretation or tenacious presuppositions. Unfortunately protagonists (both anti-religion and anti-science) receive more publicity than conciliators. This paper reviews some of the background and development of arguments over creation and evolution and shows that there is no need to choose between a rigorous scientific approach and an avowedly religious acknowledgement of God as creator and sustainer.

Fraser Watts

Ludus Vitalis Revista De Filosofia De Las Ciencias De La Vida Journal of Philosophy of Life Sciences Revue De Philosophie Des Sciences De La Vie

Louw Feenstra

Pablo Zamorano

This paper was presented at the EPPA and at an NDSU colloquia in 2012

David Kyle Johnson

It is commonly maintained among academic theists that religion and science are not in conflict. I will argue, by analogy, that they undeniably are in conflict. I will begin by quickly defining religion and science. Then I will present multiple examples that are unquestionable instances of unscientific reasoning and beliefs and show how they precisely parallel common mainstream orthodox religious reasoning and doctrines. I will close by considering objections to my argument.

Journal of Religion

Thomas Olshewsky

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Dr. Alexander F. van Biezen

Arie Leegwater

Fernando A G Alcoforado

Jeffrey M . Shaw

Subhash Sharma

Albert Fiedeldey

Abdul B Shaikh

Resolution of Religion-Science Conflict

Rawel Singh Anand

Journal of Biosciences

Antonio G. Valdecasas

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Religion and Science: Conflict or Harmony?

Some of the nation’s leading journalists gathered in Key West, Fla., in May 2009 for the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life’s Faith Angle Conference on religion, politics and public life.

Francis S. Collins, the former director of the Human Genome Project and an evangelical Christian, discussed why he believes religion and science are compatible and why the current conflict over evolution vs. faith, particularly in the evangelical community, is unnecessary.

Barbara Bradley Hagerty, the religion correspondent for National Public Radio, discussed how the brain reacts to spiritual experiences and her belief that people can look at scientific evidence and conclude that everything is explained by material means or look at the universe and see the hand of God.

Speaker: Francis S. Collins, Former Director, National Human Genome Research Institute Respondent: Barbara Bradley Hagerty, Religion Correspondent, National Public Radio Moderator: Michael Cromartie, Vice President, Ethics and Public Policy Center; Senior Adviser, Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life

In the following excerpt ellipses have been omitted to facilitate reading. Read the full transcript, including audience discussion at pewresearch.org/pewresearch-org/religion .

Francis Collins

So let’s start with the science. I know there’s broad diversity and background in this room, but I’m not going to get deeply into the nitty-gritty of genomics. I will simply use this metaphor because I think it’s a pretty good one, that the DNA of an organism is its instruction book sitting there in the nucleus of the cell. All of the DNA of any organism is its genome. Ours happens to be about 3.1 billion of those letters of the code.

The Human Genome Project set itself up in 1990 as an international effort to read out all of those letters at a time when many people thought this was foolhardy because the technology to do this hadn’t been invented. But due to the ingenuity and commitment of a very dedicated group of over 2,000 scientists that I had the privilege of leading, we did in fact — two-and-a-half years early and about $400 million under-budget — achieve the goal of reading out all of those 3.1 billion letters in April of 2003. A lot of the effort on the genome since that time has been to understand how the instruction book actually does what it does. How do you read these instructions written in this funny language that has just four letters in its alphabet — A, C, G and T — the four bases of the DNA code?

But particularly, we’ve been interested in trying to identify the ticking time bombs in the human genome that put each of us at risk for something. Progress here has been actually quite exhilarating.We’re identifying all of these risk factors for almost any disease using the tools of the Human Genome Project. That in turn provides the opportunity to identify who’s at risk for what. You can already, for $400, send your money to one of these direct-to-consumer marketing companies, and they will tell you what your risk is for about 20 different diseases. I just recently finished a book on personalized medicine, which will be coming out early in 2010, designed to try to explain this for a non-scientific audience, namely the general public, to try to begin the process of people imagining how to incorporate this information into their own health care.

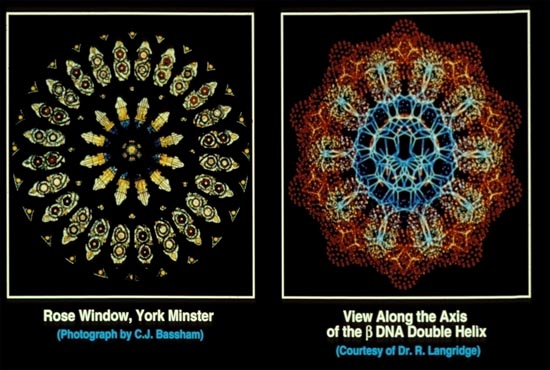

I’ve been talking about DNA; this is actually DNA.

It’s a different sort of picture than you’re used to, where instead of looking from the side, you’re looking down the barrel of the double helix. It’s quite a beautiful picture that way, and I think this is a provocative pair of images to introduce the main topic this morning, which is, are those two worldviews that you see there incompatible? On the left is the rose window of Westminster Cathedral, a beautiful stained glass window, and on the right, a picture of DNA.

There are certainly voices out there arguing that you can’t have both of those; you’ve got to take your pick. You either are going to approach questions from a purely scientific perspective or a purely spiritual perspective, and the two are locked in eternal combat. I don’t happen to agree with that, so perhaps I should say a bit of a word about how I got there.

I grew up in a home where faith was not practiced. My parents were free spirits in the arts and theater and music. I was home schooled till the sixth grade. I was not taught that faith was ridiculous, but I was certainly not taught that it mattered very much. When I got to college and later graduate school in chemistry, I became an agnostic and then eventually an atheist. In my view at that point, the only thing that really mattered was the scientific approach to understand how the universe worked; everything else was superstition.

But then I went to medical school and discovered that those hypothetical questions about life and death and whether God exists weren’t so hypothetical anymore. I realized my atheism had been arrived at as the convenient answer, not on the basis of considering the evidence. A thoughtful person turned me onto the writings of C.S. Lewis, which was quite a revelation in terms of the depth of intellectual argument that undergirds a belief in a creator God and the existence of moral law. I began to realize that even in science, where I had spent most of my time, there were pointers to God that I had paid no attention to that were actually pretty interesting.

One obvious one, although maybe it’s not so obvious, is that there is something instead of nothing. There’s no reason there should be anything at all. Wigner’s wonderful phrase “the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics” also comes to mind — Eugene Wigner, the Nobel laureate in physics, talking about the amazing thing about the whole study of physics is that mathematics makes sense; it can describe the properties of matter and energy in simple, even beautiful, laws. Why should that be? Why should gravity follow an inverse square law? Why should Maxwell’s five equations describe electromagnetism in very simple terms, and they actually turn out to be true? A thoughtful and interesting question.

The Big Bang, the fact that the universe had a beginning out of nothingness, as far as we can tell — from this unimaginable singularity, the universe came into being and has been flying apart ever since — that cries out for some explanation. Since we have not observed nature to create itself, where did this come from? That seems to ask you to postulate a creator who must not be part of nature or you haven’t solved the problem. In fact, one can also make a pretty good philosophical argument that a creator of this sort must also be outside of time or you haven’t solved the problem.

So now we have the idea of a creator who is outside of time and space, and who is a pretty darn good mathematician, and apparently also must be an incredibly good physicist. An additional set of observations I found quite breathtaking is the fact that the physical constants that determine the nature of interactions between matter and the way in which energy behaves have precisely the values they would need to have for any kind of complexity or life to occur. Various people have written about this. Martin Rees has a book on this called Just Six Numbers . Depending on how you count them up, somewhere between six and a dozen of these constants are independent of each other, and I’m talking about things like the gravitational constant. Theory can tell you that gravity is an inverse square law, but there’s that constant in there to say how strong gravity is and you can’t derive that by theory. That is something you have to measure experimentally.

That second hypothesis, the multiverse hypothesis, does require a certain amount of faith because those are not other parallel universes that we ever expect we would be able to observe. So which of those is a more faith-requiring hypothesis? I would ask you to think about that from my perspective, using the Ockham’s Razor approach that the simplest explanation may in fact be the right one. This sounds a lot like all of these things are pointing us toward a creator who had an intention about the universe that would include setting these constants so that interesting things might happen.

Then there’s C.S. Lewis’ point that I discovered while reading the first chapter of Mere Christianity , “Right and Wrong as a Clue to the Meaning of the Universe.” Where does this notion of morality come from? Is this a purely evolutionary artifact, where we have been convinced by evolution that right and wrong have meanings and that we’re supposed to do the right thing, or is there something more profound going on?

But how can you be both a believer and a biologist? I’ve certainly been asked that question on numerous occasions by people who find out that I’m a geneticist who studies DNA every day and I’m a Christian. After all, don’t you realize that evolution is incompatible with faith? If you believe in evolution, how can you be a believer? That’s the usual kind of concern.

First of all, let me say the evidence for Darwin’s theory of descent from a common ancestor by gradual change over long periods of time operated on by natural selection is absolutely overwhelming. It is not possible, I think, to look at that evidence accumulated, especially in the last few years on the basis of the study of DNA, and not come to the conclusion that Darwin was right — right in ways that Darwin himself probably never could have imagined, not knowing about DNA, not knowing that we’d have a digital record of these events to study.

Among the evidences are the ability to compare the genomes of ourselves with other species. You can feed all of that data into a computer and say, make sense of this, without telling the computer anything about what these animals look like or what the fossil record said, and the computer comes up with this analysis with all of these species lined up in order. Humans are there as part of this story, and the computer says, this really only makes sense if you derive this back to a common ancestor in this case of vertebrates. We could even extend this to invertebrates, where we have lots of sequence as well.

When you look at the details of that tree in terms of which animals are clustered close together and how long the branches are, which says something about how long it’s been since they diverged, the matchup here with the fossil record and with anatomical descriptions is breathtaking. It’s all very internally consistent. Now you might say, looking at this tree, that that doesn’t prove anything about descent from a common ancestor. If you believe that Genesis says that all of these organisms were created as individual acts of special creation, wouldn’t it have made sense for God to use some of the same DNA motifs, modifying them along the way? And wouldn’t it therefore seem to show you that DNA is more similar between creatures that look more like each other, so this doesn’t prove anything.

But when you start looking at the details, that argument really can’t be sustained anymore. I could give you many examples, but I’ll just give you one because of the time. Here is one that I think really cannot be easily understood without the common ancestor hypothesis being correct and with it involving humans.

If you look across the genome of ourselves and other species, you find genes in a particular order with space in between them. Here’s a place, for example, in the human and the cow and the mouse genome where you have the same three genes. They’re lined up in the same order, which also is consistent with a common ancestor, although it doesn’t prove it. But I picked these three for a particular reason. These genes have funny names — so what do they actually do?

I’m not going to bother you about two of them, but GULO is an interesting gene. It codes for an enzyme called gulonolactone oxidase. That is the enzyme that catalyzes the final step in the synthesis of vitamin C, ascorbic acid. You probably know that vitamin C is something that’s a vitamin because we need it. We can’t make it ourselves, and the reason for that is that our GULO gene has sustained a knockout blow About half the gene has been deleted, and there’s a little remnant left behind that you can see. The tail end of it is still evidence that GULO used to be there, but it’s not in any of us. In fact, it’s not there in any primate.

So somewhere higher up in that lineage this happened in a single individual, and that happened to be spread throughout all of the following organisms, primates and humans. That’s why we humans get scurvy if we don’t have access to vitamin C. Apparently in most of human history and primate history, there was plenty of vitamin C in the environment, so there was no great loss sustained here until we went to sea for long periods of time. Cows and mice don’t need vitamin C; they make their own. They have a GULO gene that works.

Now looking at that, of course, that immediately suggests common ancestry for all three of these species — not only suggests it, but, it seems to me, demands it because if you’re going to try to argue that the human genome was somehow special, that God created us in a different way than these other organisms, you would also have to postulate that God intentionally put a defective gene in exactly the place where a common ancestry would say it should be. Does that sound like the action of a God of all truth? I could give other examples. But — once you look at the details — it is, I think, inescapable for somebody with an open mind to conclude that descent from a common ancestor is true and we’re part of it.

Despite that, we have issues, especially here in the U.S., about what people believe about this question. You all probably have seen the Gallup Poll that gets asked every year — given the choice among three options, what do people say? That first option, that God guided a process that happened over millions of years — 38 percent; the second option, that God had no part, that being a deist or an atheist perspective — 13 percent. But the largest number — 45 percent, almost half — choose the third option, that God created human beings in their present form in the last 10,000 years. You can’t arrive at that conclusion without throwing out pretty much all of the evidence from cosmology, geology, paleontology, biology, physics, chemistry, genomics and the fossil record. Yet that is the conclusion that many Americans prefer.

There are a lot of forces trying to encourage that view. If you’ve been to the Creation Museum — I haven’t, but I gather some of you have — it will show you this perspective of humans and dinosaurs frolicking together in a way that’s consistent with the 6,000-year-old Earth. Again, many children going to see this are probably walking away thinking, yeah, that makes sense. I get e-mails practically every week from people who were raised in this tradition — many of them home schooled or schooled in a Christian high school where young Earth creationism is the only view that they’re exposed to. Then they get to university and they see the actual data that supports the age of the Earth as 4.5, 5 billion years old, and they see the data that supports evolution as being correct, and they go into an intense personal crisis.

We’ve set those folks up for a terrible struggle by what we’re doing right now in this country. It seems to me that atheism is, of all of the choices, the least rational because it assumes that you know enough to exclude the possibility of God. And which of us could claim we know enough to make such a grand statement? G.K. Chesterton says this quite nicely: “Atheism is the most daring of all dogmas, the assertion of a universal negative.”

So how, then, do we put this synthesis together? I’ll give you the view that I’ve arrived at, which in my experience is also the view that about 40 percent of working scientists who believe in a personal God have arrived at. So here it is — God, who is not limited in space or time, created this universe 13.7 billion years ago with its parameters precisely tuned to allow the development of complexity over long periods of time. That plan included the mechanism of evolution to create this marvelous diversity of living things on our planet and to include ourselves, human beings. Evolution, in the fullness of time, prepared these big-brained creatures, but that’s probably not all we are from the perspective of a believer.

Some would say, evolution just doesn’t seem like a very efficient method. Why would God spend so much time getting to the point? Remember, a few steps back there, we said the only way you’ve really solved the creator problem without ending up in an infinite regress is to have God be outside of time. So, basically, it might be a long time to us, but it might be a blink of an eye to God.

The intelligent design perspective, which is so prominent now in the evangelical church and, of course, is a flashpoint for debates about the teaching of science in schools, is basically that evolution might be OK in some ways, but it can’t account for the complexity of things like the bacterial flagellum, which are considered to be irreducibly complex because they have so many working parts and they don’t work with any of the parts dropping out, so you can’t imagine how evolution could have produced them.

This is showing severe cracks scientifically in that the supposedly irreducibly complex structures are, increasingly, yielding up their secrets, and we can see how they have been arrived at by a stepwise mechanism that’s quite comfortable from an evolutionary perspective. So intelligent design is turning out to be — and probably could have been predicted to be — a God-of-the-gaps theory, which inserts God into places that science hasn’t quite yet explained, and then science comes along and explains them.

I think I would also say intelligent design is not only bad science; it’s questionable theology. It implies that God was an underachiever and started this evolutionary process and then realized it wasn’t going to quite work and had to keep stepping in all along the way to fix it. That seems like a limitation of God’s omniscience.

I think we need only go back before Darwin and see what theologians thought about Genesis to have a better conversation about this. Go back all the way to Augustine in 400 A.D. Augustine is writing here specifically about Genesis: “In matters that are so obscure and far beyond our vision, we find in Holy Scripture passages which can be interpreted in very different ways without prejudice to the faith we have received. In such cases, we should not rush in headlong and so firmly take our stand on one side that, if further progress in the search for truth justly undermines this position, we too fall with it.” And is that not what is happening in the current climate with, in fact, insistence that the only acceptable interpretation for a serious Christian now is a literal acceptance of the six days of creation, which, again, Augustine would have argued is not required by the language?

[ The Fingerprints of God: The Search for the Science of Spirituality ]

Barbara Bradley Hagerty

For the past century, materialism had reigned triumphant. But the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago has done extensive polling on people who have spiritual experiences — not just believe in God, but a spiritual experience. It turns out that 51 percent of people have had a spiritual experience that absolutely transformed their lives. That’s a lot of people.So now I think there is a move afoot among scientists to, if not embrace, then at least study this thing called spiritual experience. They can do that because they have the technology to do that or at least to start to make inroads. They have brain scanners and EEGs, which allow them to peer into the brain.

Back in 2006, I took a year off from NPR to just study, to look at what I think of as the emerging science of spirituality. My litmus test in doing my research was this: Basically, if a prominent scientist or if prominent scientists were investigating some aspect of spiritual experience, then it was fair game for me to report on it. So I encountered questions like, is there a “God spot” in the brain? Is there a God chemical? Is God all in your head?

First I attacked the question of the “God spot” in the brain: Is there an area of the brain that handles or mediates spiritual experience — by spiritual experience I mean that notion, that transcendent moment that you have, that sense that there’s another being in the room or around you. The question is, if you can locate the place that mediates spiritual experience, does that mean that God is nothing more than brain tissue?

People have long suspected that the temporal lobe has something to do with religious experience. The temporal lobe runs along the side of your head, and it handles things like hearing and smell and memory and emotion. The first concrete evidence that there was a connection between the temporal lobe and spiritual experience was made by a Canadian neurosurgeon named Wilder Penfield. Back in the 1940s and ’50s, he began mucking around in the brains of patients as he operated on them. There aren’t any pain receptors in the brain, so he’d go in and he could take an electrode and prod a part of the brain — keep them awake — prod a part of the brain and see what part of the body corresponded with that part of the brain. Well, when he prodded the temporal lobe, something very strange happened. People reported having out-of-body experiences and hearing voices and seeing apparitions. He hypothesized that he might have found the physical seat of religious experience.

So science figured out that one way to try to explore spiritual experience and look at the brain mechanics of religious experience is to look at people with temporal lobe epilepsy on the theory that the extreme elucidates the normal. Temporal lobe epilepsy is basically an electrical storm in the brain where all the cells fire together. Usually seizures are really horrible things. I went to a Henry Ford hospital to the epilepsy clinic and it was just — it’s a horrifying experience to watch a seizure. But in a few rare cases, people have ecstatic seizures, and they believe that they are having a religious experience. They may hear snatches of music or words, presumably from their memory bank, and they interpret it as a message from God or the music from the heavenly spheres. They may see a snatch of light and think that that’s an angel.

Today a lot of neuroscientists have kind of retrofitted a lot of major religious leaders with temporal lobe epilepsy. Like Saul on the road to Damascus — was he blinded by God and heard Jesus’ voice or did he suffer, as one neurologist said, “visual and auditory hallucinations with photism and transient blindness”? Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, did he see a pillar of light and two angels or did he suffer a complex partial seizure? What about Moses and the burning bush, hearing God’s voice?

Now I’ve got to say, I have a little trouble with this kind of retrofitting, because it’s hard to imagine something as debilitating as epilepsy being helpful in writing, say, the bulk of Christian doctrine, as did Paul; guiding a nation through the wilderness for 40 years, as did Moses; or founding one of the three monotheistic religions, as did Mohammed. But I do think that scientists are onto something. I think the temporal lobe may in fact be the place that mediates spiritual experience.

One of the people who convinced me of this is a guy named Jeff Schimmel. Jeff is a writer in Hollywood. He was raised Jewish, never believed in God, had no interest in spirituality. Then a few years ago, nine years ago, when he was 40 years old, he had a benign tumor in his left temporal lobe removed. The surgery was a snap, but a couple of years later, unknown to him, he began to suffer from mini-seizures. He began hearing things and having visions. He remembers twice lying in bed when he looked up at the ceiling and saw a kind of swirl of blue and gold and green all settle into a shape, a pattern. He said, then it dawned on me, it was the Virgin Mary. Then he thinks, why would the Virgin Mary appear to a Jewish guy? But a few other things began to happen to Jeff. He became fascinated with spirituality. He found himself weeping at the drop of a hat when he saw pain in other people. He became fairly obsessed with Buddhism.

But he began to wonder, could his newfound spirituality have anything to do with his brain? So the next time he visited his neurologist, he asked to see a picture of his brain scan, the most recent one. And, in fact, the temporal lobe was very different before and after the surgery. It had kind of pulled away from the skull. His temporal lobe was smaller, a different shape, it was covered with scar tissue, and those changes had begun to spark electrical firings in his brain. He essentially developed temporal lobe epilepsy. But there was no question in his mind that his faith, his newfound love for his fellow man, all of that, came from his brain.

Are transcendent experiences — not just Jeff Schimmel’s, but Teresa of Avila’s — are they merely a physiological event or could it possibly reflect an encounter with another dimension? I want to propose that how you come down on that issue depends on whether you think of the brain as a CD player or a radio. Most scientists who think that everything is explainable through material processes think that the brain is like a CD player: The content, the CD with the song on it, for example, is playing in a closed system, and if you take a hammer to the machine, you know, destroy it, the song is not going to play. All spiritual experience is inside the brain, and when you alter the brain, God and spirituality disappear.

Now there is some scientific support for this line of thinking. These days scientists can make transcendent realities, or God, disappear or appear at will. It’s kind of a party trick. Recently a group of Swiss researchers found out that when they electrically stimulated a certain part of the brain in a woman, she suddenly felt a sensed presence, that there was another being in the room enveloping her. A lot of people describe God that way: a sensed presence, a being nearby enveloping them. So they could conjure up God just by poking part of the brain.

Making spiritual experiences disappear is, of course, far more common. It’s what epilepsy specialists are trained to do: You remove part of the temporal lobe or you medicate the brain and tamp down the electrical spikes and, voila, God disappears, all spiritual experience goes away. But suppose the brain isn’t a CD player. Suppose it’s a radio. Now in this analogy, everyone possesses the neural equipment to receive the radio program in varying degrees. So some have the volume turned low. Other people hear their favorite programs every now and again, maybe some of you all, like me, who have had brief transcendent moments. Some people have the volume way too high or they’re caught between stations and they hear a cacophony, and those people actually need medical help.

So that’s one debate about the brain and whether spiritual experience is just something within the brain or something that may transcend the brain. Another argument that God is all in your head comes from neuropharmacologists. They propose that God is nothing more than chemical reactions in your brain.

Peyote like other psychedelic drugs, including LSD and magic mushrooms seem to prompt mystical experience. Scientists have discovered recently that these psychedelic drugs have a couple of interesting things in common. Chemically, they all look a lot like serotonin, which is a neurotransmitter that affects parts of the brain that relate to emotions and perception. Now scientists at Johns Hopkins University have discovered that they all target the same serotonin receptor, serotonin HT2A. So what that receptor does is, it allows the serotonin or the psilocybin or the active ingredient of these psychedelics to create a cascade of chemical reactions, which then create the sounds and sights and smells and perceptions of a mystical experience. Essentially, they’ve discovered a “God neurotransmitter,” in a way.

He raises a third issue, which Francis alluded to, which is, why? Why are we wired to have mystical experiences in the first place? Is it possible that there is a God or an intelligence who’s created this way? I mean, if there is a God who wants to communicate with us, he probably wouldn’t use the big toe; he’d probably use the brain. Doesn’t it make sense that this is how God would communicate?

Now in the end, I don’t think science will be able to prove or disprove God, but I do think there’s a really fascinating debate that’s circling around spiritual issues. We may actually make some headway about it. There may be a way to tackle this issue in a definitive way. It’s the mind-brain debate, or can consciousness operate when the brain is stilled?

Read the full transcript including discussion at pewresearch.org/pewresearch-org/religion .

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

Most Popular

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Religion and Science

The relationship between religion and science is the subject of continued debate in philosophy and theology. To what extent are religion and science compatible? Are religious beliefs sometimes conducive to science, or do they inevitably pose obstacles to scientific inquiry? The interdisciplinary field of “science and religion”, also called “theology and science”, aims to answer these and other questions. It studies historical and contemporary interactions between these fields, and provides philosophical analyses of how they interrelate.

This entry provides an overview of the topics and discussions in science and religion. Section 1 outlines the scope of both fields, and how they are related. Section 2 looks at the relationship between science and religion in five religious traditions, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism. Section 3 discusses contemporary topics of scientific inquiry in which science and religion intersect, focusing on divine action, creation, and human origins.

1.1 A brief history

1.2 what is science, and what is religion, 1.3 taxonomies of the interaction between science and religion, 1.4 the scientific study of religion, 2.1 christianity, 2.3 hinduism, 2.4 buddhism, 2.5 judaism, 3.1 divine action and creation, 3.2 human origins, works cited, other important works, other internet resources, related entries, 1. science, religion, and how they interrelate.

Since the 1960s, scholars in theology, philosophy, history, and the sciences have studied the relationship between science and religion. Science and religion is a recognized field of study with dedicated journals (e.g., Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science ), academic chairs (e.g., the Andreas Idreos Professor of Science and Religion at Oxford University), scholarly societies (e.g., the Science and Religion Forum), and recurring conferences (e.g., the European Society for the Study of Science and Theology’s biennial meetings). Most of its authors are theologians (e.g., John Haught, Sarah Coakley), philosophers with an interest in science (e.g., Nancey Murphy), or (former) scientists with long-standing interests in religion, some of whom are also ordained clergy (e.g., the physicist John Polkinghorne, the molecular biophysicist Alister McGrath, and the atmospheric scientist Katharine Hayhoe). Recently, authors in science and religion also have degrees in that interdisciplinary field (e.g., Sarah Lane Ritchie).

The systematic study of science and religion started in the 1960s, with authors such as Ian Barbour (1966) and Thomas F. Torrance (1969) who challenged the prevailing view that science and religion were either at war or indifferent to each other. Barbour’s Issues in Science and Religion (1966) set out several enduring themes of the field, including a comparison of methodology and theory in both fields. Zygon, the first specialist journal on science and religion, was also founded in 1966. While the early study of science and religion focused on methodological issues, authors from the late 1980s to the 2000s developed contextual approaches, including detailed historical examinations of the relationship between science and religion (e.g., Brooke 1991). Peter Harrison (1998) challenged the warfare model by arguing that Protestant theological conceptions of nature and humanity helped to give rise to science in the seventeenth century. Peter Bowler (2001, 2009) drew attention to a broad movement of liberal Christians and evolutionists in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries who aimed to reconcile evolutionary theory with religious belief. In the 1990s, the Vatican Observatory (Castel Gandolfo, Italy) and the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences (Berkeley, California) co-sponsored a series of conferences on divine action and how it can be understood in the light of various contemporary sciences. This resulted in six edited volumes (see Russell, Murphy, & Stoeger 2008 for a book-length summary of the findings of this project).

The field has presently diversified so much that contemporary discussions on religion and science tend to focus on specific disciplines and questions. Rather than ask if religion and science (broadly speaking) are compatible, productive questions focus on specific topics. For example, Buddhist modernists (see section 2.4 ) have argued that Buddhist theories about the self (the no-self) and Buddhist practices, such as mindfulness meditation, are compatible and are corroborated by neuroscience.