- Log in / Register

- Getting started

- Criteria for a problem formulation

- Find who and what you are looking for

- Too broad, too narrow, or o.k.?

- Test your knowledge

- Lesson 5: Meeting your supervisor

- Getting started: summary

- Literature search

- Searching for articles

- Searching for Data

- Databases provided by your library

- Other useful search tools

- Free text, truncating and exact phrase

- Combining search terms – Boolean operators

- Keep track of your search strategies

- Problems finding your search terms?

- Different sources, different evaluations

- Extract by relevance

- Lesson 4: Obtaining literature

- Literature search: summary

- Research methods

- Combining qualitative and quantitative methods

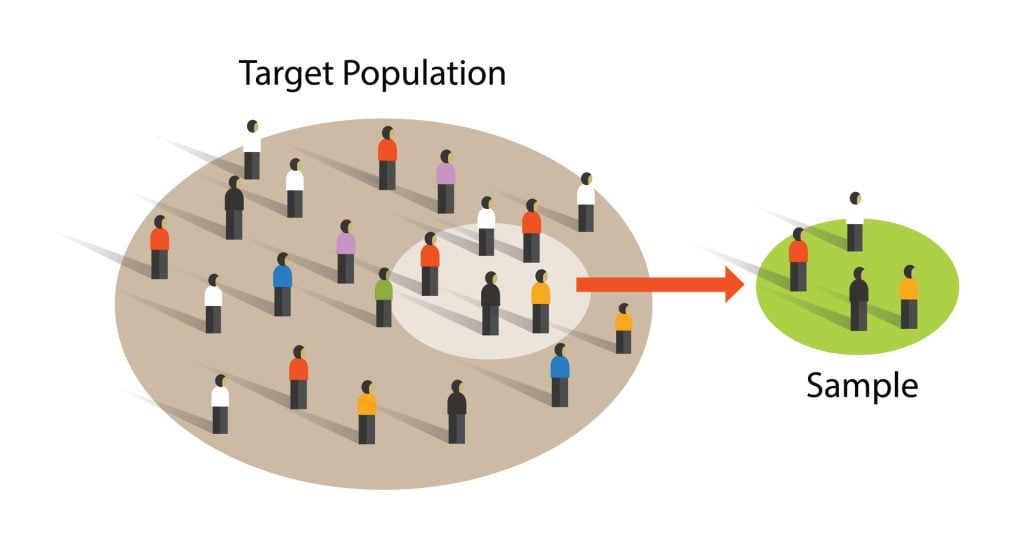

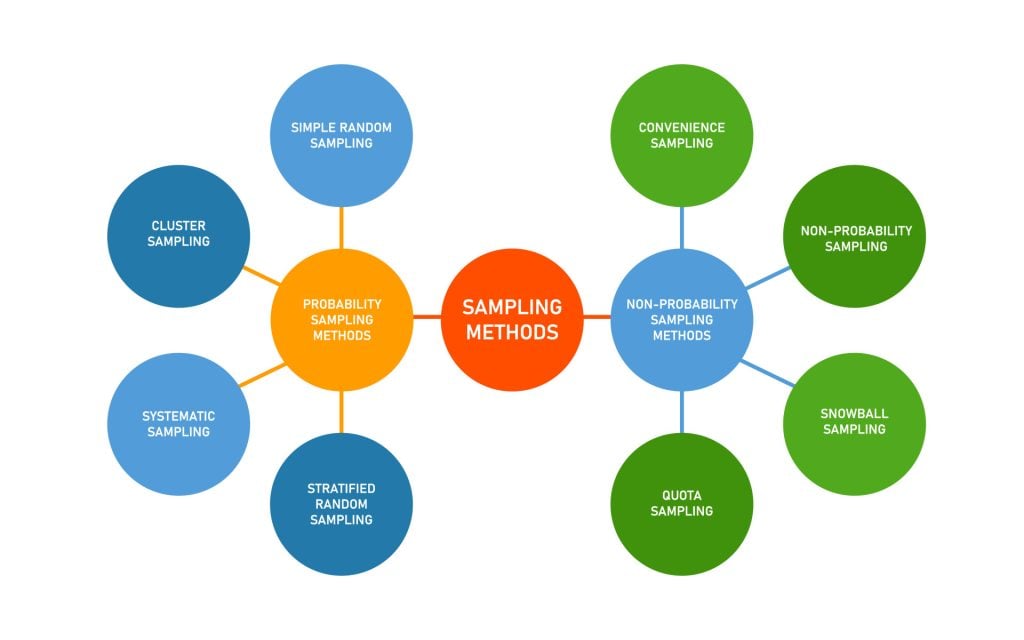

- Collecting data

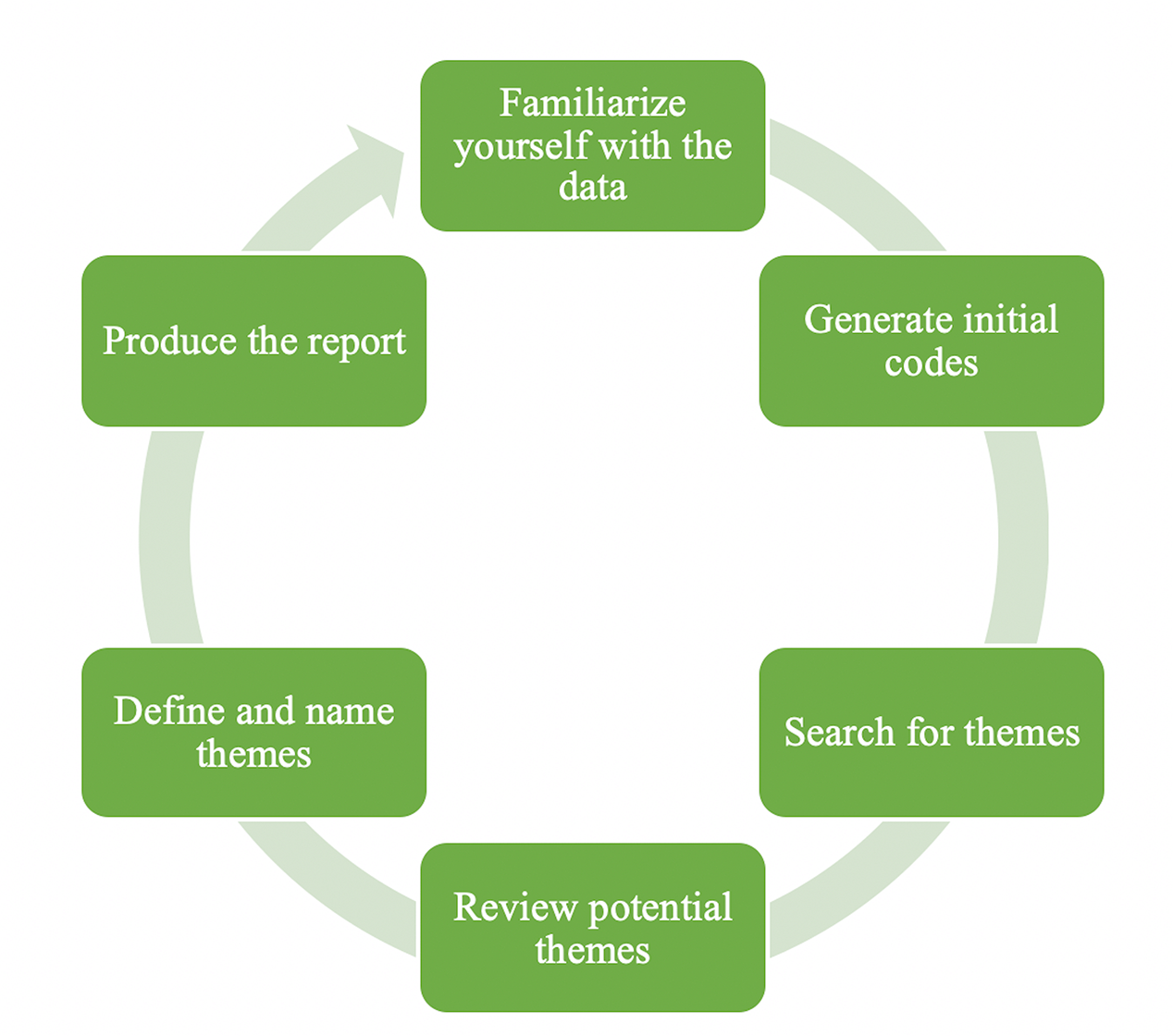

- Analysing data

Strengths and limitations

- Explanatory, analytical and experimental studies

- The Nature of Secondary Data

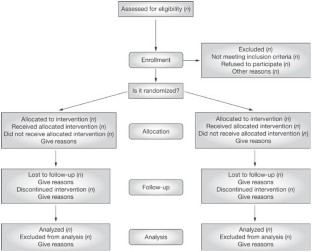

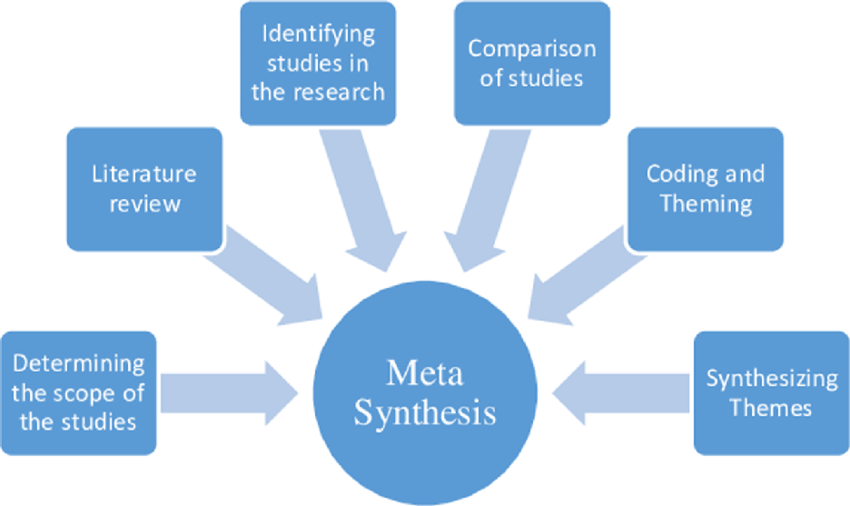

- How to Conduct a Systematic Review

- Directional Policy Research

- Strategic Policy Research

- Operational Policy Research

- Conducting Research Evaluation

- Research Methods: Summary

- Project management

- Project budgeting

- Data management plan

- Quality Control

- Project control

- Project management: Summary

- Writing process

- Title page, abstract, foreword, abbreviations, table of contents

- Introduction, methods, results

- Discussion, conclusions, recomendations, references, appendices, layout

- Use citations correctly

- Use references correctly

- Bibliographic software

- Writing process – summary

- Research methods /

- Lesson 1: Qualitative and quan… /

Quantitative method Quantitive data are pieces of information that can be counted and which are usually gathered by surveys from large numbers of respondents randomly selected for inclusion. Secondary data such as census data, government statistics, health system metrics, etc. are often included in quantitative research. Quantitative data is analysed using statistical methods. Quantitative approaches are best used to answer what, when and who questions and are not well suited to how and why questions.

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Findings can be generalised if selection process is well-designed and sample is representative of study population | Related secondary data is sometimes not available or accessing available data is difficult/impossible |

| Relatively easy to analyse | Difficult to understand context of a phenomenon |

| Data can be very consistent, precise and reliable | Data may not be robust enough to explain complex issues |

Qualitative method Qualitative data are usually gathered by observation, interviews or focus groups, but may also be gathered from written documents and through case studies. In qualitative research there is less emphasis on counting numbers of people who think or behave in certain ways and more emphasis on explaining why people think and behave in certain ways. Participants in qualitative studies often involve smaller numbers of tools include and utilizes open-ended questionnaires interview guides. This type of research is best used to answer how and why questions and is not well suited to generalisable what, when and who questions.

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Complement and refine quantitative data | Findings usually cannot be generalised to the study population or community |

| Provide more detailed information to explain complex issues | More difficult to analyse; don’t fit neatly in standard categories |

| Multiple methods for gathering data on sensitive subjects | Data collection is usually time consuming |

| Data collection is usually cost efficient |

Learn more about using quantitative and qualitative approaches in various study types in the next lesson.

Your friend's e-mail

Message (Note: The link to the page is attached automtisk in the message to your friend)

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Evaluating research methods: Assumptions, strengths, and weaknesses of three research paradigms

Related Papers

British Journal of Sociology

Solomon Tilahun

Introduction Educational researchers in every discipline need to be cognisant of alternative research traditions to make decisions about which method to use when embarking on a research study. There are two major approaches to research that can be used in the study of the social and the individual world. These are quantitative and qualitative research. Although there are books on research methods that discuss the differences between alternative approaches, it is rare to find an article that examines the design issues at the intersection of the quantitative and qualitative divide based on eminent research literature. The purpose of this article is to explain the major differences between the two research paradigms by comparing them in terms of their epistemological, theoretical, and methodological underpinnings. Since quantitative research has well-established strategies and methods but qualitative research is still growing and becoming more differentiated in methodological approaches, greater consideration will be given to the latter.

Katrin Niglas

Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung Forum Qualitative Social Research

Margrit Schreier

Kezang sherab

Issues in Educational Research

Noella Mackenzie

Flanny Alamparambil

Dr. Mustapha Kulungu

Darrell M Hull , Robin Henson , Cynthia S. Williams

How doctoral programs train future researchers in quantitative methods has important implications for the quality of scientifically based research in education. The purpose of this article, therefore, is to examine how quantitative methods are used in the literature and taught in doctoral programs. Evidence points to deficiencies in quantitative training and application in several areas: (a) methodological reporting problems, (b) researcher misconceptions and inaccuracies, (c) overreliance on traditional methods, and (d) a lack of coverage of modern advances. An argument is made that a culture supportive of quantitative methods is not consistently available to many applied education researchers. Collective quantitative proficiency is defined as a vision for a culture representative of broader support for quantitative methodology (statistics, measurement, and research design).

Research on Humanities and Social Sciences

Brian Mumba

How do we decide whether to use a quantitative or qualitative methodology for our study? Quantitative and qualitative research (are they a dichotomy or different ends on a continuum?). How do we analyse and write the results of a study for the research article or our thesis? Further questions can be asked such as; is the paradigm same as research design? How can we spot a paradigm in our research article? Although the questions are answered quietly explicitly, the discussion on the paradigm and research design remains technical. This can be evidenced by the confusion that people still face in differentiating between a paradigm, methodology, approach and design when doing research. The confusion is further worsened by the quantitative versus qualitative research dichotomies. This article addresses quantitative and qualitative research while discussing scientific research paradigms from educational measurement and evaluation perspective.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Feyisa Mulisa

Marta Costa

Zeinab NasserEddine

Oriol Iglesias

Educational Researcher

Kadriye Ercikan

Journal of Research in Nursing

William Firestone

Prince Kumar

Salome Schulze

Proceedings of the 4th European …

Sarah Kaplan

Ziabur Rahman

Reinaldo Furlan

BinVa Chang

New Directions for Program Evaluation

Sharon Rallis

Qualitative & Multi-Method Research

Hein Goemans

Quality & Quantity

Mansoor Niaz

Jeff Jawitz

EMOs Tanzania

Chong Ho Yu

Monika Jakubicz

Kathryn Pole

International Journal of Value-based Management

Deborah Brazeal

mubashar yaqoob

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Strengths and Limitations of Qualitative and Quantitative Research Methods

- September 2017

- 3(9):369-387

- Instituto Superior Politécnico Gaya

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Lama Al Thowaibi

- Khalid Allam

- Siham Lalaoui

- Tak Jie Chan

- Ravtesh Kaur

- Sarah Hyman

- Khutlang Lekhisa

- Occup Ther Health Care

- Yousef R Babish

- Lama Nammoura

- Kareemah Abu-Asabeh

- José Augusto Monteiro

- C.R.Kothari

- Hamza Alshenqeeti

- Looi Theam Choy

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Strengths Approach to Research

The University of Minnesota provided new students access to take the Gallup Strengths from 2011-2016. This page was created based on those results and a students "Top 5." What are your strengths? Strengths can be used to support your academic and library work from picking a topic for a research paper to finding the sources you need to citing. There are many ways to go about doing research -- having an awareness of different ways to do it--will help. Research in metacognition tells us that having an awareness of your strengths before you begin a task or project can help you to learn more effectively. Below is information about ways to use your unique strengths to do academic and library research more effectively, efficiently and even enjoyably.

Find your strength below

Enjoy hard work and being productive

- Talk to upperclassmen about their research.

- Set clear deadlines and goals. Meet them. Use the Assignment Calculator.

- Consider writing for publication.

- Meet with the librarian for your department or topic to learn in depth.

Turning thoughts into actions

- Pick a topic for a cause or organization you are involved with such as a service learning, volunteer or student group . Base your topic on how you can solve a problem or learn more about an issue in front of something in your real life or something you feel passionate about.

- Think of research as an active investigation and a way to learn more about something in your real life.

- Work to get a draft done and then share it with others for constructive feedback.

- Discuss your topic ideas with your instructor during office hours and clarify assignment requirements.

Adaptibility

Go with the flow

- Consider research as an adventure and enjoy the meandering path to learning. Research isn’t a race-your flexibility can lessen frustration when you don’t find exactly what you are looking for. Instead take time to enjoy finding something unexpected . Adjust and flex your topic based on the research you find. You are not stuck in one way of thinking.

- Pick a topic which has potential for humor, irony and look for ways to connect the unexpected.

- Do your research in the Libraries when you need to focus and give your full attention and find a quiet spot to concentrate.

Search for reason and causes.

- Pick topics about questions/problems you want to know the answers to and that you are already curious about.

- Use a wide variety of sources for research including data, facts, maps , primary sources , etc. and use this to dig deeper into the topic and to inform your thinking on the topic.

- Look for cause and effect relationships in your research such as in scientific discoveries, ethical lapses, legal judgements.

- Critically evaluate what you read and question an author’s conclusions.

- Draw mind maps to illustrate how your sub-topics, facts and ideas fit together.

- Identify your own biases before taking sides on an issue. Research all sides of an issue.

Figure out how all the pieces are organized

- Note dates on a calendar. Use the Assignment Calculator .

- Consider where environmentally you work best.

- Plan fun activities as a reward for yourself after you complete tasks such as turning in a research project.

- Break down your project into separate pieces.

Core values that are unchanging

- Select research project topics that appeal to your core values

- Consider learning more about individuals who have stood for noble causes

- Be aware and explore opposing points of views

Take control and make decisions

- Jot down questions while you do research as questioning accelerates your learning.

- Challenge facts and do more research to uncover the truth.

- Consider research a debate and research all sides of an issue then use this to make a decision on your own conclusions.

Communication

Easily put your thoughts into words

- Talk with friends and classmates about topics you are interested in. Use these conversations to shape and refine your topic.

- Visit office hours to talk with your instructor about your topic ideas or what you have found in your research.

- Consider cross purposing your research--if you have another class in which you need to do a presentation or speech -- use the research paper for a different angle.

- Remember writing is putting your thoughts in writing. Think of a research paper as a speech or presentation and develop an outline in this way.

Competition

Strive to win first place and enjoy contests

- Clarify how the points are given in research papers by your instructor and spend time on the project accordingly

- Work to find an unusual topic that will challenge you instead of an “easy” topic or work to find unusual or unexpected sources (e.g. archival letter, video, interview, etc.)

- Become a master on your topic and strive to gather deep knowledge of the subject.

- Look for opportunities to submit your paper to the instructor as a model to share with future students or for campus awards.

- Consider looking at opportunities to publish your writing in a school publication, for a professional organization or for an outside publication.

Connectedness

Enjoy links between all things

- Select research topics that speak to your greater purpose and life goals. Select topics that allow you to make connections to the greater community, world or historical events.

- Use freewriting as a strategy and focus on making connections between ideas and research on a topic.

- Make connections between authors or scholars on a topic. Look at the bibliography or a tool like Web of Science or Google Scholar which lets you see who has cited whom.

- Look for study spot in the Libraries that have a calm atmosphere .

- Help fellow students see connections to help their own research topics.

Consistency

Seek to treat people the same. Set up rules and adhere to them.

- Understand your research project and how points will be given.

- Use the Assignment Calculator to plan out the research and writing steps to complete your project.

- Balance facts gathered in research and focus on being objective. Create an outline to map out paper.

- Work to set up a routine when you get a new research paper assignment and follow those steps each time. Adjusting as needed.

Enjoy thinking about the past.

- Pick research topics which allow you to explore the past. For example -- Use a history database to search history journals.

- Study specific events, personalities or periods of history. Research political, natural, cultural aspects.

- Use the Libraries to find additional readings to support or give additional historical background on class topics.

- Consider exploring our Archives or Special Collections for a deeper look at the past and discover unique sources of information (e.g. public records, surveys, letters or legislation). Use unexpected sources of information such as photographs, paintings, blueprints, films, costumes, recipes, etc. These items will bring history to life.

- Work on a digital history project either your own or help to collect histories of others.

- If looking for a research mentor, use the Libraries to read the articles or writings of a potential mentor such as their doctoral dissertation, lectures, speeches, articles, etc.

- Consider enhancing a research paper by creating a narrative from the perspective of a person during that historical time period or a historical figure.

Deliberative

Anticipate obstacles. Take care in making decisions or choices.

- Prepare assignments in advance of due dates. Try the Assignment Calculator .

- Review research paper assignments and flag potential obstacles. Make a plan to overcome them.

- Set aside enough time for research. Do a complete job of research and reading.

- Be aware that settling on one topic may be challenging so do preliminary research on multiple topics. Then decide.

Cultivate the potential in others. See improvements in others.

- Select a few possible research topics. Do preliminary topics then explain to a friend or fellow student about what you have learned to help select a topic.

- Become a tutor or help someone else in class in their research or writing.

- Reflect on the sources you have selected and track how these have increase your own knowledge on the topic.

- Talk to your mentor about your research to reinforce what you have learned and to clarify your own thoughts on the topic.

- Reflect upon what you have learned in your research paper and how that has impacted you.

Enjoy routine and structure. Create order.

- If the project is large scale, develop your own structure to meet the class requirements.

- Make an outline to break down a topic into parts. Work on and complete those parts individually.

- Because you strive for an organized space for studying, consider studying in the Libraries .

Sense the feelings of others. Imagine yourself in other’s situations or lives.

- When possible, pick a topic involving people or historic figures.

- As you find sources, find out more about the authors such as their presence on social media, blogs, or research groups, etc.

- Be aware that research can be like a roller coaster with high points and low points.

- Imagine yourself in the place of the person or situation you are researching. Learn from this approach as you writing your paper.

- Consider enhancing a research paper by creating a narrative from the perspective of a person impacted by the topic you are writing about.

Prioritize, then act. Stay on track.

- Work with instructor to modify assignment to align it to your practical values if possible.

- Before doing research -- lists your accomplishments for that session of research.

- Outline the main points you plan to research and write about.

- Try to focus on one part of a large research paper at a time.

Visualize, but then use tools to manage deadlines.

- As someone who is fascinated by the future, share your grandiose ideas or perspectives when doing group research projects.

- Use your ability to visualize a final product as a launching pad.

- Consider creating a structured outline to your research and map out what is needed to complete each part.

- Do not get stuck in the dreaming and visualizing state. Consider using a tool like an Assignment Calculator to stay on schedule.

Find common ground. Be aware of opposing views.

- As someone who attempts to find common ground, be aware of opposing viewpoints in scholarly communication.

- Try Points of View Reference Center , a library database.

- When evaluating information sources, consider authority and credibility.

- Seek out group projects that may benefit from your stability, calmness, and productivity.

Enjoy generating ideas during topic development, but don’t forget to focus on other required tasks.

- Since you are fascinated by ideas, topic development should be fun for you. Engage with other imaginative peers to brainstorm concepts.

- Keep a journal where you capture all of your creative ideas.

- You may struggle with narrowing your topic. Try to focus on depth, not breadth.

- The Assignment Calculator may help you stay on task and meet deadlines.

- When presenting your findings, look for creative ways like new presentation software or infographics.

Be social and consider study space options that work for you.

- Since you enjoy social interaction and thrive at making others feel included be sure to have a social component to your research process.

- Meet in a social environment like a library or coffee shop to discuss findings.

- Encourage reserved or shy peers to share their findings and viewpoints.

Individualization

Consider different points of view. Pair and share.

- You excel at finding the distinctions between people. Consider qualitative research such as observation and ethnography.

- Since you enjoy learning about different points of view, pair and share while researching and writing.

- Consider meeting with a Peer Research Consultant . When writing, think about the uniqueness of contribution to the field of study.

Search, stay organized, and use tools to manage your time.

- You love collecting information. This will be beneficial in the information gathering stage of research and report writing. Search in the library catalog and databases.

- Use recommended citation managers for organizing your gathered notes, documents, and citations.

- Since you crave information, keep in mind that you may need to switch gears to writing or creation mode. Use the Assignment Calculator to help you manage your time.

Intellection

Study where you are most productive, and track your progress.

- As someone who is introspective, you may benefit from keeping a research journal. Keep track of what keywords and library databases have been successful.

- Be mindful of study spaces where you have been most productive. Consider quiet or group study spaces in the University Libraries .

- Since you likely enjoy reading, find all of the materials that will help you with your research.

- Seek out help from your subject librarian if you are having trouble locating information information.

- Consider citation managers like Zotero to help you organize your information.

Select new and exciting topics. Consider your study space options.

- As someone who loves to learn, dive right in.

- Since you love new information, select research topics that are new and exciting to you. Others may be intimidated by unfamiliar topics, but you thrive in this environment.

- If you prefer quiet spaces when reading or writing, check out the quiet study spaces in the University Libraries .

- Strive to stay focused on your selected topic as opposed to veering off into other exciting topics of interest.

Help peers maximize talents. Find mentors.

- You are productive and have high expectations. Focus on your research talents, whatever they may be, and use them to benefit your discipline or community.

- In group research projects, help your peers maximize their talents.

- Find mentors in professors, librarians, and community members; these relationships will be most beneficial if you value their wisdom.

Use tools to set goal deadlines. Consider productive study spaces.

- Regardless of setbacks during the research process, you tend to react positively.

- Set incremental goals and use the Assignment Calculator . Celebrate after each achievement.

- Since you work best in relaxed, social environments, consider researching and writing in public spaces like University Libraries .

- Select research topics that are exciting to you and your interests.

Work in groups. Take social breaks.

- Since you value relationships, work with others during the research process. Seek input and assistance from librarians , professors, and Peer Research Consultants .

- If your research focus is very independant, reach out to others for periodic social breaks.

- You are interested in personalities and character; consider this when selecting research topics.

Responsibility

Ethically use information. Find the best sources for your project.

- Your focus on ethics will guide you to make ethical decisions about properly citing your sources. For assistance, we recommend using library citation managers .

- Since you thrive on responsibility, go the extra mile with finding the best primary and secondary sources in library databases.

- Take the lead on group research projects.

Restorative

Solve problems. Research is an iterative process.

- As a natural problem solver, think about your research as a problem that needs to be solved.

- Analyze the problem as well as your research workflow.

- Searching is a strategic exploration. Use library databases.

- After finishing a draft, ask a peer to review for gaps. Make an effort to be comprehensive and complete by filling in the gaps and correcting the problems.

Self-Assurance

Be challenged. Solve problems.

- Since you enjoy being challenged, select a topic that others may find problematic.

- Trust your instincts when selecting paper topics and citation managers .

- You may want to follow your intuition when evaluating sources. Be skeptical about things like authority and credibility.

- Keyword searching is often trial and error, and this works well for you because you are able to bounce back from adversity.

Significance

Share your research. Scholarship is a conversation.

- Since you enjoy exposure, consider publishing in a journal or presenting on your research at a conference.

- Consider selecting unique topics where you may be publicly recognized for unique contributions.

- Pair up with peers and faculty members with similar research interests.

Searching is strategic exploration. Be persistent.

- Since working backward from a goal works well for you, consider this approach to research.

- Envision the final product but also realize that topics and themes often evolve during the research and writing process.

- Be aware that searching is a complex process.

- Select research projects that coincide with your creative thinking or creative problem solving.

Research happens in a variety of spaces. Exchange ideas.

- Write and research in social environments like libraries and coffee shops. Find a University Libraries space that works for you.

- Share ideas with your classmates since you find interacting with other people to be energizing.

- Exchange ideas within your social network.

- Consider that scholarship is a conversation. You are engaging in scholarly communication when adding your research to the discipline.

Child Care and Early Education Research Connections

Descriptive research studies.

Descriptive research is a type of research that is used to describe the characteristics of a population. It collects data that are used to answer a wide range of what, when, and how questions pertaining to a particular population or group. For example, descriptive studies might be used to answer questions such as: What percentage of Head Start teachers have a bachelor's degree or higher? What is the average reading ability of 5-year-olds when they first enter kindergarten? What kinds of math activities are used in early childhood programs? When do children first receive regular child care from someone other than their parents? When are children with developmental disabilities first diagnosed and when do they first receive services? What factors do programs consider when making decisions about the type of assessments that will be used to assess the skills of the children in their programs? How do the types of services children receive from their early childhood program change as children age?

Descriptive research does not answer questions about why a certain phenomenon occurs or what the causes are. Answers to such questions are best obtained from randomized and quasi-experimental studies . However, data from descriptive studies can be used to examine the relationships (correlations) among variables. While the findings from correlational analyses are not evidence of causality, they can help to distinguish variables that may be important in explaining a phenomenon from those that are not. Thus, descriptive research is often used to generate hypotheses that should be tested using more rigorous designs.

A variety of data collection methods may be used alone or in combination to answer the types of questions guiding descriptive research. Some of the more common methods include surveys, interviews, observations, case studies, and portfolios. The data collected through these methods can be either quantitative or qualitative. Quantitative data are typically analyzed and presenting using descriptive statistics . Using quantitative data, researchers may describe the characteristics of a sample or population in terms of percentages (e.g., percentage of population that belong to different racial/ethnic groups, percentage of low-income families that receive different government services) or averages (e.g., average household income, average scores of reading, mathematics and language assessments). Quantitative data, such as narrative data collected as part of a case study, may be used to organize, classify, and used to identify patterns of behaviors, attitudes, and other characteristics of groups.

Descriptive studies have an important role in early care and education research. Studies such as the National Survey of Early Care and Education and the National Household Education Surveys Program have greatly increased our knowledge of the supply of and demand for child care in the U.S. The Head Start Family and Child Experiences Survey and the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study Program have provided researchers, policy makers and practitioners with rich information about school readiness skills of children in the U.S.

Each of the methods used to collect descriptive data have their own strengths and limitations. The following are some of the strengths and limitations of descriptive research studies in general.

Study participants are questioned or observed in a natural setting (e.g., their homes, child care or educational settings).

Study data can be used to identify the prevalence of particular problems and the need for new or additional services to address these problems.

Descriptive research may identify areas in need of additional research and relationships between variables that require future study. Descriptive research is often referred to as "hypothesis generating research."

Depending on the data collection method used, descriptive studies can generate rich datasets on large and diverse samples.

Limitations:

Descriptive studies cannot be used to establish cause and effect relationships.

Respondents may not be truthful when answering survey questions or may give socially desirable responses.

The choice and wording of questions on a questionnaire may influence the descriptive findings.

Depending on the type and size of sample, the findings may not be generalizable or produce an accurate description of the population of interest.

Find what you need to study

1.2 Research Methods in Psychology

4 min read • june 18, 2024

Sadiyya Holsey

Jillian Holbrook

Overview of Research Methods

There are various types of research methods in psychology with different purposes, strengths, and weaknesses.

| 🧪 | Manipulates one or more to determine the effects of certain behavior. | (1) can determine (2) can be retested and proven | (1) could have potential |

| (2) artificial environment creates low (people know they are being researched, which could impact what they say and do) | |||

| 📈 | Involves looking at the relationships between two or more variables and is used when performing an experiment is not possible. | (1) easier to conduct than an experiment (2) | |

| can be used when an experiment is impossible. For example, a researcher may want to examine the relationship between and . It would not be ethical to force students to take high doses of . So, one can only rely on participants’ responses | cannot determine | ||

| 💭 | The collection of information reported by people about a particular topic. | (1) cost-effective (2) mostly reliable | (1) low (2) can’t verify the accuracy of an individual’s response |

| 👀 | A researcher observes a subject's behavior without intervention. | natural setting is more reliable than a lab setting | (1) people behave differently when they know they are being watched, which could impact the results ( ) (2) two researchers could see the same behavior but draw different conclusions |

| 💼 | A case study is an in-depth study of an individual or a small group. Usually, are done on people with rare circumstances. For example, a girl named Genie was locked in her room, causing a delay in development. Researchers did a case study about her to understand more about language and . | provides detailed information | (1) cannot to a wider population (2) difficult to (3) time-consuming |

| ↔️ | The same individuals are studied over a long period of time from years up to decades. | (1) can show the effects of changes over time (2) more powerful than | (1) require large amounts of time (2) expensive |

| A examines people of different groups at the same time. For example, studying people that are different ages at the same time to see what differences can be attributed to age. | (1) quick and easy to conduct (2) generalizable results | (1) difficult to find a population that differs by only one factor (2) cannot measure changes over time |

Experiment 🧪

Whenever researchers want to prove or find causation, they would run an experiment.

An experiment you'll learn about in Unit 9 that was run by Solomon Asch investigated the extent to which one would conform to a group's ideas.

Image Courtesy of Wikipedia .

Each person in the room would have to look at these lines above and state which one they thought was of similar length to the original line. The answer was, of course, obvious, but Asch wanted to see if the "real participant" would conform to the views of the rest of the group.

Asch gathered together what we could call "fake participants" and told them not to say line C. The "real participant" would then hear wrong answers, but they did not want to be the odd one out, so they conformed with the rest of the group and represented the majority view.

In this experiment, the "real participant" was the control group , and about 75% of them, over 12 trials, conformed at least once.

Correlational Study 📈

There could be a correlational study between anything. Say you wanted to see if there was an association between the number of hours a teenager sleeps and their grades in high school. If there was a correlation, we cannot say that sleeping a greater number of hours causes higher grades. However, we can determine that they are related to each other. 💤

Remember in psychology that a correlation does not prove causation!

Survey Research 💭

Surveys are used all the time, especially in advertising and marketing. They are often distributed to a large number of people, and the results are returned back to researchers.

Naturalistic Observation 👀

If a student wanted to observe how many people fully stop at a stop sign, they could watch the cars from a distance and record their data. This is a naturalistic observation since the student is in no way influencing the results.

Case Study 💼

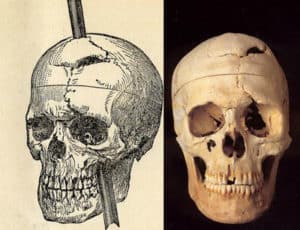

A notable psychological case study is the study of Phineas Gage :

Image Courtesy of Vermont Journal

Phineas Gage was a railroad construction foreman who survived a severe brain injury in 1848. The accident occurred when an iron rod was accidentally driven through Gage's skull, damaging his frontal lobes . Despite the severity of the injury, Gage was able to walk and talk immediately after the accident and appeared to be relatively uninjured.

However, Gage's personality underwent a dramatic change following the injury. He became impulsive, irresponsible, and prone to outbursts of anger, which were completely out of character for him before the accident. Gage's case is famous in the history of psychology because it was one of the first to suggest that damage to the frontal lobes of the brain can have significant effects on personality and behavior.

Key Terms to Review ( 27 )

Stay Connected

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

AP® and SAT® are trademarks registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 20 January 2009

How to critically appraise an article

- Jane M Young 1 &

- Michael J Solomon 2

Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology volume 6 , pages 82–91 ( 2009 ) Cite this article

52k Accesses

100 Citations

446 Altmetric

Metrics details

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article in order to assess the usefulness and validity of research findings. The most important components of a critical appraisal are an evaluation of the appropriateness of the study design for the research question and a careful assessment of the key methodological features of this design. Other factors that also should be considered include the suitability of the statistical methods used and their subsequent interpretation, potential conflicts of interest and the relevance of the research to one's own practice. This Review presents a 10-step guide to critical appraisal that aims to assist clinicians to identify the most relevant high-quality studies available to guide their clinical practice.

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article

Critical appraisal provides a basis for decisions on whether to use the results of a study in clinical practice

Different study designs are prone to various sources of systematic bias

Design-specific, critical-appraisal checklists are useful tools to help assess study quality

Assessments of other factors, including the importance of the research question, the appropriateness of statistical analysis, the legitimacy of conclusions and potential conflicts of interest are an important part of the critical appraisal process

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Making sense of the literature: an introduction to critical appraisal for the primary care practitioner

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 2: systematic reviews and meta-analyses

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 1: randomised controlled trials

Druss BG and Marcus SC (2005) Growth and decentralisation of the medical literature: implications for evidence-based medicine. J Med Libr Assoc 93 : 499–501

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Glasziou PP (2008) Information overload: what's behind it, what's beyond it? Med J Aust 189 : 84–85

PubMed Google Scholar

Last JE (Ed.; 2001) A Dictionary of Epidemiology (4th Edn). New York: Oxford University Press

Google Scholar

Sackett DL et al . (2000). Evidence-based Medicine. How to Practice and Teach EBM . London: Churchill Livingstone

Guyatt G and Rennie D (Eds; 2002). Users' Guides to the Medical Literature: a Manual for Evidence-based Clinical Practice . Chicago: American Medical Association

Greenhalgh T (2000) How to Read a Paper: the Basics of Evidence-based Medicine . London: Blackwell Medicine Books

MacAuley D (1994) READER: an acronym to aid critical reading by general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract 44 : 83–85

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hill A and Spittlehouse C (2001) What is critical appraisal. Evidence-based Medicine 3 : 1–8 [ http://www.evidence-based-medicine.co.uk ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Public Health Resource Unit (2008) Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) . [ http://www.phru.nhs.uk/Pages/PHD/CASP.htm ] (accessed 8 August 2008)

National Health and Medical Research Council (2000) How to Review the Evidence: Systematic Identification and Review of the Scientific Literature . Canberra: NHMRC

Elwood JM (1998) Critical Appraisal of Epidemiological Studies and Clinical Trials (2nd Edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2002) Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence? Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 47, Publication No 02-E019 Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Crombie IK (1996) The Pocket Guide to Critical Appraisal: a Handbook for Health Care Professionals . London: Blackwell Medicine Publishing Group

Heller RF et al . (2008) Critical appraisal for public health: a new checklist. Public Health 122 : 92–98

Article Google Scholar

MacAuley D et al . (1998) Randomised controlled trial of the READER method of critical appraisal in general practice. BMJ 316 : 1134–37

Article CAS Google Scholar

Parkes J et al . Teaching critical appraisal skills in health care settings (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 3. Art. No.: cd001270. 10.1002/14651858.cd001270

Mays N and Pope C (2000) Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 320 : 50–52

Hawking SW (2003) On the Shoulders of Giants: the Great Works of Physics and Astronomy . Philadelphia, PN: Penguin

National Health and Medical Research Council (1999) A Guide to the Development, Implementation and Evaluation of Clinical Practice Guidelines . Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council

US Preventive Services Taskforce (1996) Guide to clinical preventive services (2nd Edn). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins

Solomon MJ and McLeod RS (1995) Should we be performing more randomized controlled trials evaluating surgical operations? Surgery 118 : 456–467

Rothman KJ (2002) Epidemiology: an Introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: sources of bias in surgical studies. ANZ J Surg 73 : 504–506

Margitic SE et al . (1995) Lessons learned from a prospective meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 43 : 435–439

Shea B et al . (2001) Assessing the quality of reports of systematic reviews: the QUORUM statement compared to other tools. In Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context 2nd Edition, 122–139 (Eds Egger M. et al .) London: BMJ Books

Chapter Google Scholar

Easterbrook PH et al . (1991) Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 337 : 867–872

Begg CB and Berlin JA (1989) Publication bias and dissemination of clinical research. J Natl Cancer Inst 81 : 107–115

Moher D et al . (2000) Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUORUM statement. Br J Surg 87 : 1448–1454

Shea BJ et al . (2007) Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 7 : 10 [10.1186/1471-2288-7-10]

Stroup DF et al . (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283 : 2008–2012

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: evaluating surgical effectiveness. ANZ J Surg 73 : 507–510

Schulz KF (1995) Subverting randomization in controlled trials. JAMA 274 : 1456–1458

Schulz KF et al . (1995) Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 273 : 408–412

Moher D et al . (2001) The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology 1 : 2 [ http://www.biomedcentral.com/ 1471-2288/1/2 ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Rochon PA et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 1. Role and design. BMJ 330 : 895–897

Mamdani M et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ 330 : 960–962

Normand S et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 3. Analytical strategies to reduce confounding. BMJ 330 : 1021–1023

von Elm E et al . (2007) Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 335 : 806–808

Sutton-Tyrrell K (1991) Assessing bias in case-control studies: proper selection of cases and controls. Stroke 22 : 938–942

Knottnerus J (2003) Assessment of the accuracy of diagnostic tests: the cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol 56 : 1118–1128

Furukawa TA and Guyatt GH (2006) Sources of bias in diagnostic accuracy studies and the diagnostic process. CMAJ 174 : 481–482

Bossyut PM et al . (2003)The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 138 : W1–W12

STARD statement (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies). [ http://www.stard-statement.org/ ] (accessed 10 September 2008)

Raftery J (1998) Economic evaluation: an introduction. BMJ 316 : 1013–1014

Palmer S et al . (1999) Economics notes: types of economic evaluation. BMJ 318 : 1349

Russ S et al . (1999) Barriers to participation in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 52 : 1143–1156

Tinmouth JM et al . (2004) Are claims of equivalency in digestive diseases trials supported by the evidence? Gastroentrology 126 : 1700–1710

Kaul S and Diamond GA (2006) Good enough: a primer on the analysis and interpretation of noninferiority trials. Ann Intern Med 145 : 62–69

Piaggio G et al . (2006) Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA 295 : 1152–1160

Heritier SR et al . (2007) Inclusion of patients in clinical trial analysis: the intention to treat principle. In Interpreting and Reporting Clinical Trials: a Guide to the CONSORT Statement and the Principles of Randomized Controlled Trials , 92–98 (Eds Keech A. et al .) Strawberry Hills, NSW: Australian Medical Publishing Company

National Health and Medical Research Council (2007) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 89–90 Canberra: NHMRC

Lo B et al . (2000) Conflict-of-interest policies for investigators in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 343 : 1616–1620

Kim SYH et al . (2004) Potential research participants' views regarding researcher and institutional financial conflicts of interests. J Med Ethics 30 : 73–79

Komesaroff PA and Kerridge IH (2002) Ethical issues concerning the relationships between medical practitioners and the pharmaceutical industry. Med J Aust 176 : 118–121

Little M (1999) Research, ethics and conflicts of interest. J Med Ethics 25 : 259–262

Lemmens T and Singer PA (1998) Bioethics for clinicians: 17. Conflict of interest in research, education and patient care. CMAJ 159 : 960–965

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

JM Young is an Associate Professor of Public Health and the Executive Director of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney,

Jane M Young

MJ Solomon is Head of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre and Director of Colorectal Research at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney, Australia.,

Michael J Solomon

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jane M Young .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Young, J., Solomon, M. How to critically appraise an article. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 6 , 82–91 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Download citation

Received : 10 August 2008

Accepted : 03 November 2008

Published : 20 January 2009

Issue Date : February 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Emergency physicians’ perceptions of critical appraisal skills: a qualitative study.

- Sumintra Wood

- Jacqueline Paulis

- Angela Chen

BMC Medical Education (2022)

An integrative review on individual determinants of enrolment in National Health Insurance Scheme among older adults in Ghana

- Anthony Kwame Morgan

- Anthony Acquah Mensah

BMC Primary Care (2022)

Autopsy findings of COVID-19 in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Anju Khairwa

- Kana Ram Jat

Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology (2022)

The use of a modified Delphi technique to develop a critical appraisal tool for clinical pharmacokinetic studies

- Alaa Bahaa Eldeen Soliman

- Shane Ashley Pawluk

- Ousama Rachid

International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy (2022)

Critical Appraisal: Analysis of a Prospective Comparative Study Published in IJS

- Ramakrishna Ramakrishna HK

- Swarnalatha MC

Indian Journal of Surgery (2021)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

11.2: Strengths and weaknesses of survey research

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 25662

- Matthew DeCarlo

- Radford University via Open Social Work Education

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Identify and explain the strengths of survey research

- Identify and explain the weaknesses of survey research

Survey research, as with all methods of data collection, comes with both strengths and weaknesses. We’ll examine both in this section.

Strengths of survey methods

Researchers employing survey methods to collect data enjoy a number of benefits. First, surveys are an excellent way to gather lots of information from many people. In a study of older people’s experiences in the workplace, researchers were able to mail a written questionnaire to around 500 people who lived throughout the state of Maine at a cost of just over $1,000. This cost included printing copies of a seven-page survey, printing a cover letter, addressing and stuffing envelopes, mailing the survey, and buying return postage for the survey. I realize that $1,000 is nothing to sneeze at, but just imagine what it might have cost to visit each of those people individually to interview them in person. You would have to dedicate a few weeks of your life at least, drive around the state, and pay for meals and lodging to interview each person individually. We could double, triple, or even quadruple our costs pretty quickly by opting for an in-person method of data collection over a mailed survey. Thus, surveys are relatively cost-effective.

Related to the benefit of cost-effectiveness is a survey’s potential for generalizability. Because surveys allow researchers to collect data from very large samples for a relatively low cost, survey methods lend themselves to probability sampling techniques, which we discussed in Chapter 10. Of all the data collection methods described in this textbook, survey research is probably the best method to use when one hopes to gain a representative picture of the attitudes and characteristics of a large group.

Survey research also tends to be a reliable method of inquiry. This is because surveys are standardized in that the same questions, phrased in exactly the same way, are posed to participants. Other methods, such as qualitative interviewing, which we’ll learn about in Chapter 13, do not offer the same consistency that a quantitative survey offers. This is not to say that all surveys are always reliable. A poorly phrased question can cause respondents to interpret its meaning differently, which can reduce that question’s reliability. Assuming well-constructed questions and survey design, one strength of this methodology is its potential to produce reliable results.

The versatility of survey research is also an asset. Surveys are used by all kinds of people in all kinds of professions. The versatility offered by survey research means that understanding how to construct and administer surveys is a useful skill to have for all kinds of jobs. Lawyers might use surveys in their efforts to select juries, social service and other organizations (e.g., churches, clubs, fundraising groups, activist groups) use them to evaluate the effectiveness of their efforts, businesses use them to learn how to market their products, governments use them to understand community opinions and needs, and politicians and media outlets use surveys to understand their constituencies.

In sum, the following are benefits of survey research:

- Cost-effectiveness

- Generalizability

- Reliability

- Versatility

Weaknesses of survey methods

As with all methods of data collection, survey research also comes with a few drawbacks. First, while one might argue that surveys are flexible in the sense that we can ask any number of questions on any number of topics in them, the fact that the survey researcher is generally stuck with a single instrument for collecting data, the questionnaire. Surveys are in many ways rather inflexible . Let’s say you mail a survey out to 1,000 people and then discover, as responses start coming in, that your phrasing on a particular question seems to be confusing a number of respondents. At this stage, it’s too late for a do-over or to change the question for the respondents who haven’t yet returned their surveys. When conducting in-depth interviews, on the other hand, a researcher can provide respondents further explanation if they’re confused by a question and can tweak their questions as they learn more about how respondents seem to understand them.

Depth can also be a problem with surveys. Survey questions are standardized; thus, it can be difficult to ask anything other than very general questions that a broad range of people will understand. Because of this, survey results may not be as valid as results obtained using methods of data collection that allow a researcher to more comprehensively examine whatever topic is being studied. Let’s say, for example, that you want to learn something about voters’ willingness to elect an African American president, as in our opening example in this chapter. General Social Survey respondents were asked, “If your party nominated an African American for president, would you vote for him if he were qualified for the job?” Respondents were then asked to respond either yes or no to the question. But what if someone’s opinion was more complex than could be answered with a simple yes or no? What if, for example, a person was willing to vote for an African American woman but not an African American man? [1]

In sum, potential drawbacks to survey research include the following:

- Inflexibility

- Lack of depth

Key Takeaways

- Strengths of survey research include its cost effectiveness, generalizability, reliability, and versatility.

- Weaknesses of survey research include inflexibility and issues with depth.

Image attributions

experience by mohamed_hassan CC-0

- I am not at all suggesting that such a perspective makes any sense. ↵

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 10: Qualitative Data Collection & Analysis Methods

10.7 Strengths and Weaknesses of Qualitative Interviews

As the preceding sections have suggested, qualitative interviews are an excellent way to gather detailed information. Whatever topic is of interest to the researcher can be explored in much more depth by employing this method than with almost any other method. Not only are participants given the opportunity to elaborate in a way that is not possible with other methods, such as survey research, but, in addition, they are able share information with researchers in their own words and from their own perspectives, rather than attempting to fit those perspectives into the perhaps limited response options provided by the researcher. Because qualitative interviews are designed to elicit detailed information, they are especially useful when a researcher’s aim is to study social processes, or the “how” of various phenomena. Yet another, and sometimes overlooked, benefit of qualitative interviews that occurs in person is that researchers can make observations beyond those that a respondent is orally reporting. A respondent’s body language, and even her or his choice of time and location for the interview, might provide a researcher with useful data.

As with quantitative survey research, qualitative interviews rely on respondents’ ability to accurately and honestly recall whatever details about their lives, circumstances, thoughts, opinions, or behaviors are being examined. Qualitative interviewing is also time-intensive and can be quite expensive. Creating an interview guide, identifying a sample, and conducting interviews are just the beginning of the process. Transcribing interviews is labor-intensive, even before coding begins. It is also not uncommon to offer respondents some monetary incentive or thank-you for participating, because you are asking for more of the participants’ time than if you had mailed them a questionnaire containing closed-ended questions. Conducting qualitative interviews is not only labor intensive but also emotionally taxing. Researchers embarking on a qualitative interview project with a subject that is sensitive in nature should keep in mind their own abilities to listen to stories that may be difficult to hear.

Research Methods for the Social Sciences: An Introduction Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Strengths and weaknesses of survey research

Learning objectives.

- Identify and explain the strengths of survey research

- Identify and explain the weaknesses of survey research

Survey research, as with all methods of data collection, comes with both strengths and weaknesses. We’ll examine both in this section.

Strengths of survey methods

Researchers employing survey methods to collect data enjoy a number of benefits. First, surveys are an excellent way to gather lots of information from many people. In a study of older people’s experiences in the workplace, researchers were able to mail a written questionnaire to around 500 people who lived throughout the state of Maine at a cost of just over $1,000. This cost included printing copies of a seven-page survey, printing a cover letter, addressing and stuffing envelopes, mailing the survey, and buying return postage for the survey. I realize that $1,000 is nothing to sneeze at, but just imagine what it might have cost to visit each of those people individually to interview them in person. You would have to dedicate a few weeks of your life at least, drive around the state, and pay for meals and lodging to interview each person individually. We could double, triple, or even quadruple our costs pretty quickly by opting for an in-person method of data collection over a mailed survey. Thus, surveys are relatively cost-effective.

Related to the benefit of cost-effectiveness is a survey’s potential for generalizability. Surveys allow researchers to collect data from very large samples for a relatively low cost, therefore survey methods lend themselves to the probability sampling techniques discussed in Chapter 10. Of all the data collection methods described in this textbook, survey research is probably best to use when the researcher wishes to gain a representative picture of the attitudes and characteristics of a large group.

Survey research also tends to be a reliable method of inquiry. This is because surveys are standardized in that the same questions, phrased in exactly the same way, are posed to participants. Other methods like qualitative interviewing, which we’ll learn about in Chapter 13, do not offer the same consistency that a quantitative survey offers. This is not to say that all surveys are always reliable. A poorly phrased question can cause respondents to interpret its meaning differently, which can reduce that question’s reliability. Assuming well-constructed questions and survey design, one strength of this methodology is its potential to produce reliable results.

The versatility of survey research is also an asset. Surveys are used by all kinds of people in all kinds of professions, which means that understanding how to construct and administer surveys is a useful skill to have. Lawyers might use surveys in their efforts to select juries. Social services and other organizations (e.g., churches, clubs, fundraising groups, activist groups) use them to evaluate the effectiveness of their efforts. Businesses utilize surveys to inform marketing strategies for their products. Governments use surveys to understand community opinions and needs. Politicians and media outlets use surveys to understand their constituencies.

In sum, the following are benefits of survey research:

- Cost-effectiveness

- Generalizability

- Reliability

- Versatility

Weaknesses of survey methods

As with all methods of data collection, survey research comes with a few drawbacks. While some may argue that surveys are flexible because researchers can ask many different questions on a plethora of topics, survey researchers are generally confined to a single instrument for collecting data, the questionnaire. Surveys are in many ways rather inflexible . Let’s say you mail a survey out to 1,000 people and then discover, as responses start coming in, that your phrasing on a particular question seems to be confusing a number of respondents. At this stage, it’s too late for a do-over or to change the question for the respondents who haven’t yet returned their surveys. When conducting in-depth interviews, on the other hand, a researcher can provide respondents further explanation if they’re confused by a question and can tweak their questions as they learn more about how respondents seem to understand them.

Depth can also be a problem with surveys. Survey questions are standardized; thus, it can be difficult to ask anything other than very general questions that a broad range of people will understand. Due to the general nature of questions, survey results may not be as valid as results obtained using other methods of data collection that allow a researcher to comprehensively examine the topic being studied. For example, let’s think back to the opening example of this chapter and say that you want to learn something about voters’ willingness to elect an African American president. General Social Survey respondents were asked, “If your party nominated an African American for president, would you vote for him if he were qualified for the job?” Respondents were then asked to respond either yes or no to the question. What if someone’s opinion was more complex than a simple yes or no? What if, for example, a person was willing to vote for an African American woman but not an African American man? [1]

In sum, potential drawbacks to survey research include the following:

- Inflexibility

- Lack of depth

Key Takeaways

- Strengths of survey research include its cost effectiveness, generalizability, reliability, and versatility.

- Weaknesses of survey research include inflexibility and lack of potential depth.

Image attributions

experience by mohamed_hassan CC-0

- I am not at all suggesting that such a perspective makes any sense. ↵

Scientific Inquiry in Social Work Copyright © 2018 by Matthew DeCarlo is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Warning: The NCBI web site requires JavaScript to function. more...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Electroconvulsive Therapy Performed Outside of Surgical Suites: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness, Safety, and Guidelines [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2015 Jan 14.

Electroconvulsive Therapy Performed Outside of Surgical Suites: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness, Safety, and Guidelines [Internet].

Appendix 4 summary of study strengths and limitations.

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Systematic reviews (SR) | ||

| Micallef-Trigona, 2014, Malta | ||

| Ren, 2014, China | ||

| Gaynes, 2011, USA (AHRQ report) | ||

| Randomized controlled trials (RCT) | ||

| Brakemeier, 2014, Germany | ||

| Polster, 2014, Germany | ||

| Kayser, 2010, Germany | ||

AHRQ = = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; GRADE = Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

Copyright : This report contains CADTH copyright material and may contain material in which a third party owns copyright. This report may be used for the purposes of research or private study only . It may not be copied, posted on a web site, redistributed by email or stored on an electronic system without the prior written permission of CADTH or applicable copyright owner.

Links : This report may contain links to other information available on the websites of third parties on the Internet. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third party sites is governed by the owners’ own terms and conditions.

Except where otherwise noted, this work is distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

- Cite this Page Electroconvulsive Therapy Performed Outside of Surgical Suites: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness, Safety, and Guidelines [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2015 Jan 14. APPENDIX 4, Summary of Study Strengths and Limitations.

- PDF version of this title (671K)

Other titles in this collection

- CADTH Rapid Response Reports

Recent Activity

- Summary of Study Strengths and Limitations - Electroconvulsive Therapy Performed... Summary of Study Strengths and Limitations - Electroconvulsive Therapy Performed Outside of Surgical Suites: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness, Safety, and Guidelines

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

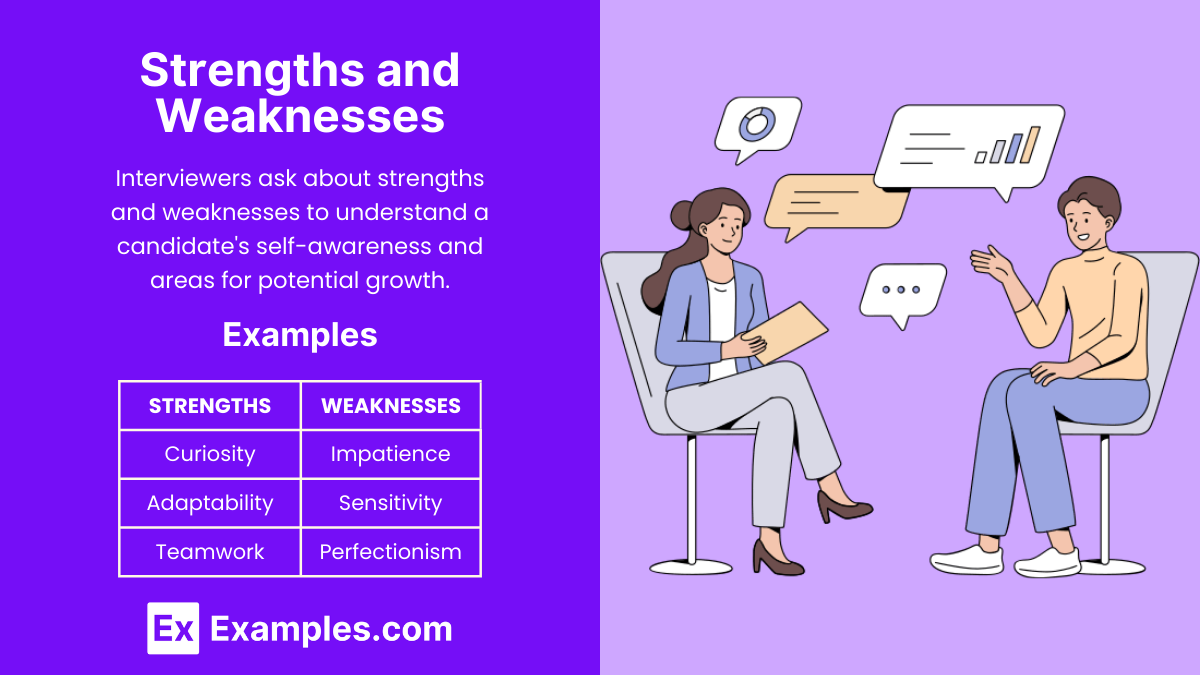

Strengths and Weaknesses

Ai generator.

After one has submitted their best resume or perfect resume to a hiring manager, recruiter, or employer, they will be endorsed to the next step of the hiring or application process. Most application processes will let the person continue to the interview where the hiring manager or the HR will try to gauge the person’s personality, knowledge, and skills .

What Are the Strengths and Weaknesses?

Strengths are the skills, attributes, or areas of knowledge where an individual excels, providing a distinct advantage in certain situations or tasks. Conversely, weaknesses are aspects where an individual may lack proficiency, confidence, or capability, which can hinder progress in both personal and professional contexts. Recognizing the nature of these traits is the first step towards effective personal development.

Strengths and Weaknesses Examples for Students

- Curiosity – Eagerness to learn and explore new subjects.

- Time Management – Balancing schoolwork, hobbies, and social activities effectively.

- Organizational Skills – Keeping study materials and schedules well-organized.

- Critical Thinking – Ability to analyze information and form reasoned conclusions.

- Persistence – Continuing effort to achieve in spite of difficulties.

- Active Listening – Paying full attention in class and grasping new concepts quickly.

- Public Speaking – Comfort with presenting in front of peers.

- Adaptability to Technology – Proficiency in using digital tools for learning.

- Self-motivation – Initiating and completing tasks without external encouragement.

- Group Collaboration – Working effectively in project teams or study groups.

- Shyness – Difficulty in speaking up in class or group discussions.

- Distraction – Easily sidetracked by social media or other interests.

- Over-planning – Spending too much time on planning rather than doing.

- Fear of Public Speaking – Anxiety when required to present or speak publicly.

- Impulsiveness – Making decisions or actions without adequate thought.

- Prioritization – Struggling to identify which tasks or studies are most important.

- Test Anxiety – Nervousness that impairs performance during exams.

- Over-Reliance on Help – Depending too much on assistance from peers or teachers.

- Underestimating Deadlines – Frequently underestimating the time needed to complete assignments.

- Rigid Thinking – Difficulty adapting to new methods or different perspectives.

Strengths and Weaknesses Examples for Freshers

- Eagerness to Learn – High enthusiasm for acquiring new skills and knowledge.

- Flexibility – Willingness to take on various roles or responsibilities.

- Tech-Savvy – Strong familiarity with latest technology and software.

- Innovative Thinking – Bringing new ideas to the team.

- Cultural Awareness – Understanding and adapting to diverse workplace environments.

- Positive Attitude – Maintaining optimism and energy.

- Strong Work Ethic – Commitment to working hard and achieving results.

- Quick Learner – Ability to grasp new concepts and processes swiftly.

- Networking Skills – Building relationships within and outside the organization.

- Open-Mindedness – Receptive to feedback and different ideas.

- Limited Industry Experience – Lack of practical experience in a professional setting.

- Tendency to Overpromise – Committing to more than can be realistically delivered.

- Difficulty with Constructive Criticism – Taking feedback too personally.

- Lack of Confidence – Uncertainty in one’s abilities due to inexperience.

- Time Management in Work Settings – Adapting to managing work tasks efficiently.

- Fear of Asking Questions – Hesitation to seek clarification when needed.

- Struggle with Authority – Adjusting to hierarchical structures in the workplace.

- Over-Enthusiasm – Sometimes overwhelming others with intense energy.

- Lack of Negotiation Skills – Difficulty in bargaining or advocating for oneself.

- Inexperience with Office Politics – Naivety about navigating professional relationships.

Strengths and Weaknesses Examples for Job Interviews

- Professionalism – Consistent display of mature behavior and attitude.

- Communication Skills – Clarity in expressing thoughts and understanding others.

- Leadership Potential – Ability to guide and inspire others.

- Reliability – Dependability in completing tasks and meeting deadlines.

- Emotional Intelligence – Understanding and managing one’s emotions and those of others.

- Conflict Resolution – Skill in resolving disagreements effectively.

- Analytical Abilities – Competence in examining information and solving problems.

- Strategic Planning – Proficiency in setting goals and determining actions to achieve them.

- Customer Service Orientation – Dedication to fulfilling the needs and expectations of clients.

- Goal-Oriented – Focused on achieving specified outcomes.

- Perfectionistic Tendencies – Often spending too much time perfecting minor details.

- Overthinking – Complicating situations by thinking too much about them.

- High Self-Criticism – Frequently finding faults in one’s own work.

- Discomfort with Uncertainty – Struggling in situations where outcomes are unpredictable.

- Limited Experience in a Specific Role – Lack of specific skills due to limited role exposure.

- Difficulty Saying No – Tendency to take on more than can be handled.

- Inexperience with Remote Work – Adjusting to working outside a traditional office.

- Impatience with Slow Processes – Frustration with tasks that progress more slowly than expected.