The gender pay gap

- Research Briefing

- Work and incomes

- Brigid Francis-Devine

- Patrick Brione

This briefing paper provides statistics on the size of the gender pay gap in the UK and how it varies by factors such as age, occupation and location.

Documents to download

The gender pay gap (590 KB , PDF)

Supporting documents

- Data tables Data tables (29 KB , Excel Spreadsheet ) (29 KB , Excel Spreadsheet)

The gender pay gap measures the difference between average (median) hourly earnings of men and women, usually shown by the percentage men earn more than women.

Note that figures for 2020 especially, but also 2021, should be treated with some caution. Some people were on furlough with reduced pay and figures for 2020 were particularly affected by disruptions to the collection of data from businesses.

How big is the gender pay gap?

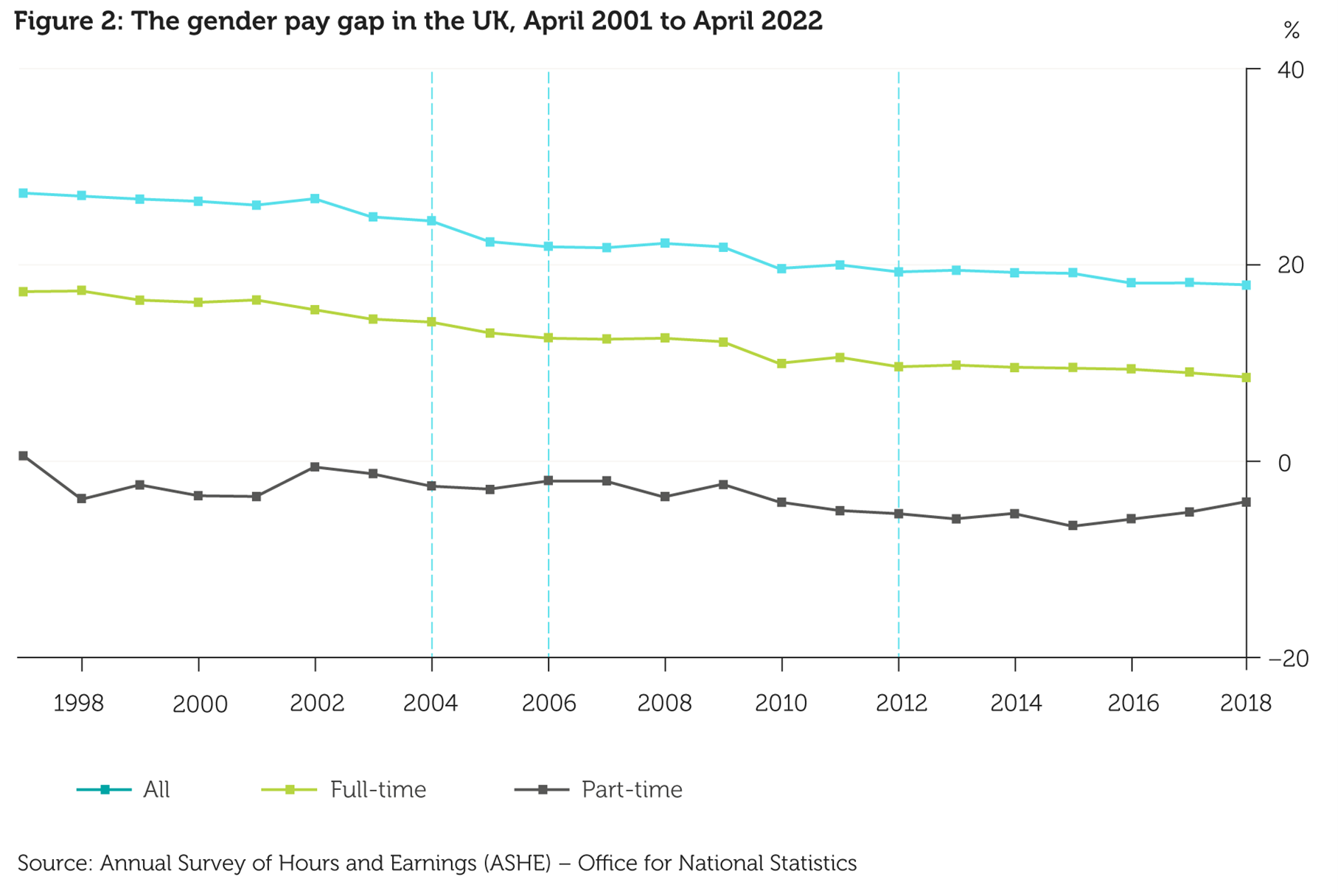

According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), median hourly pay for full-time employees was 7.7% less for women than for men in April 2023, while median hourly pay for part-time employees was 3.3% higher for women than for men (figures exclude overtime pay). The median is the point at which half of employees earn more and half earn less. It is regarded a better measure of pay of the ‘typical’ employee than taking an average.

Because a larger proportion of women are employed part-time, and part-time workers tend to earn less per hour, the gender pay gap for all employees is considerably larger than the full-time and part-time gaps. Median pay for all employees was 14.3% less for women than for men in April 2023.

The full-time pay gap has been getting smaller since 1997 and the overall pay gap has also decreased over the period. The part-time pay gap has generally remained small and negative, with women earning more than men on average.

Why is there a gender pay gap?

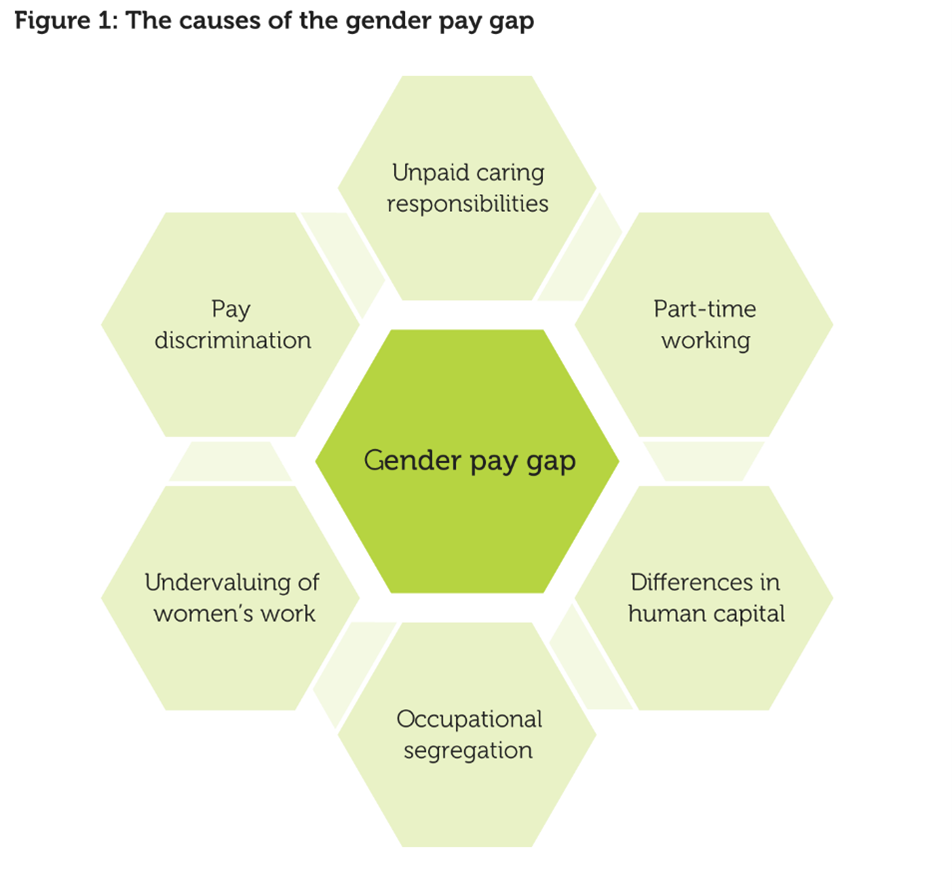

The size of the gender pay gap depends on several factors, including:

- Age: There is little difference in median hourly pay for male and female full-time employees aged in their 20s and 30s, but a substantial gap emerges among full-time employees aged 40 and over. This links to parenthood – the gap between male and female hourly earnings grows gradually but steadily in the years after parents have their first child.

- Occupation: The gap tends to be smaller for occupation groups where a larger proportion of employees are women;

- Industry: The pay gap is largest in the financial and insurance industry, and smallest in the accommodation and food services industry;

- Public and private sector: For full-time workers, the pay gap is slightly smaller in the public sector than the private sector. There is a negligible gender pay gap for part-time workers in the private sector, which contrasts with a large part-time pay gap in the public sector;

- Region and nation: The full-time gender pay gap is highest in the South East and London and negative in Northern Ireland;

- Pay: The highest earners have a larger pay gap than the lowest earners.

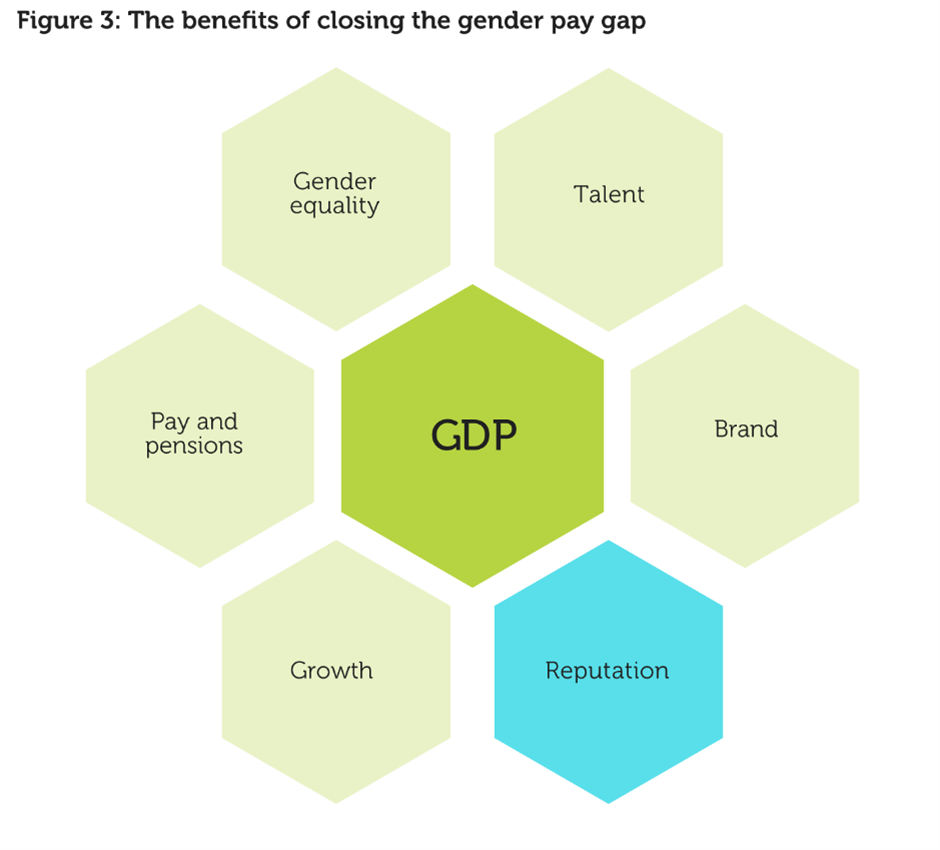

Gender pay gap reporting

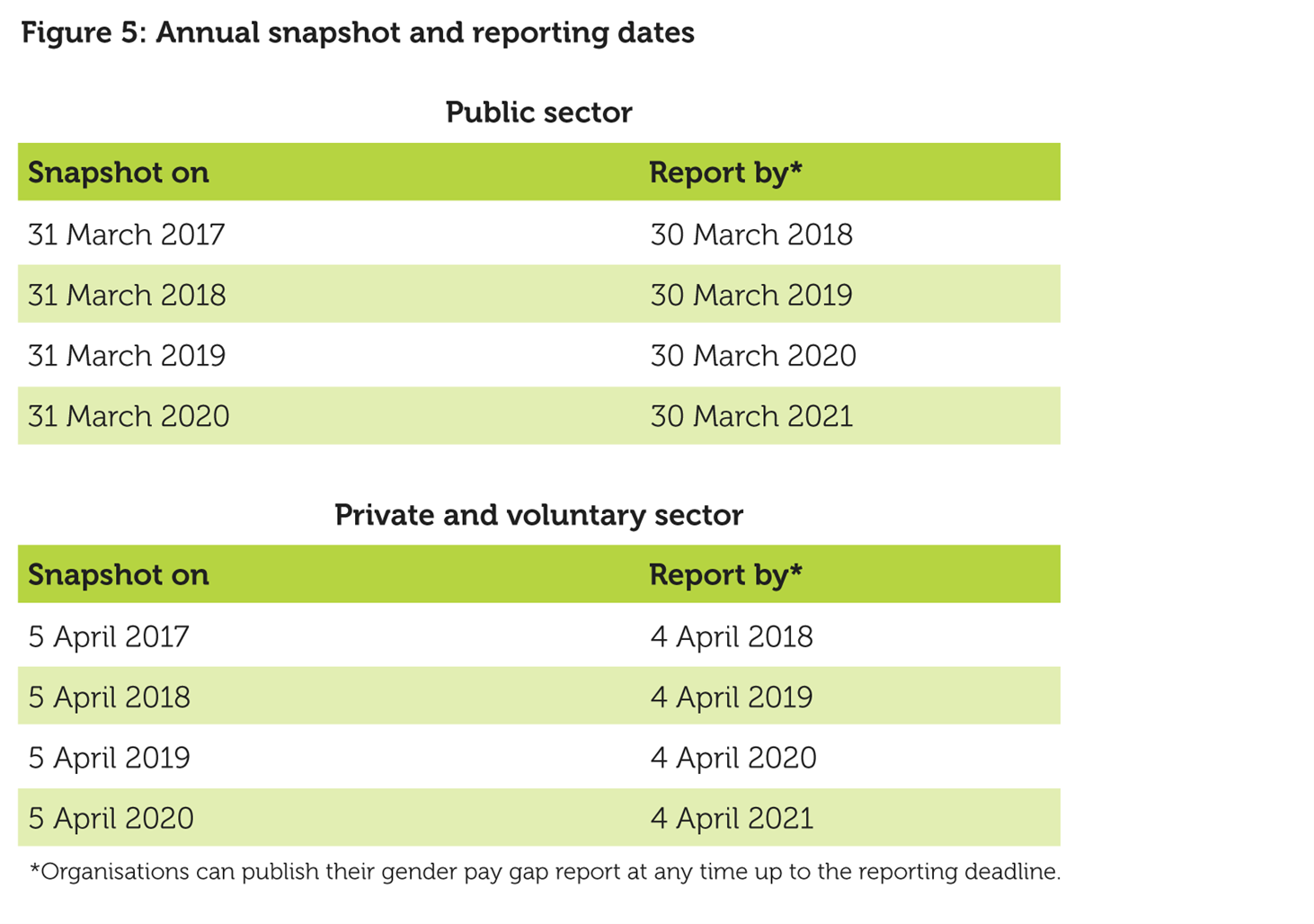

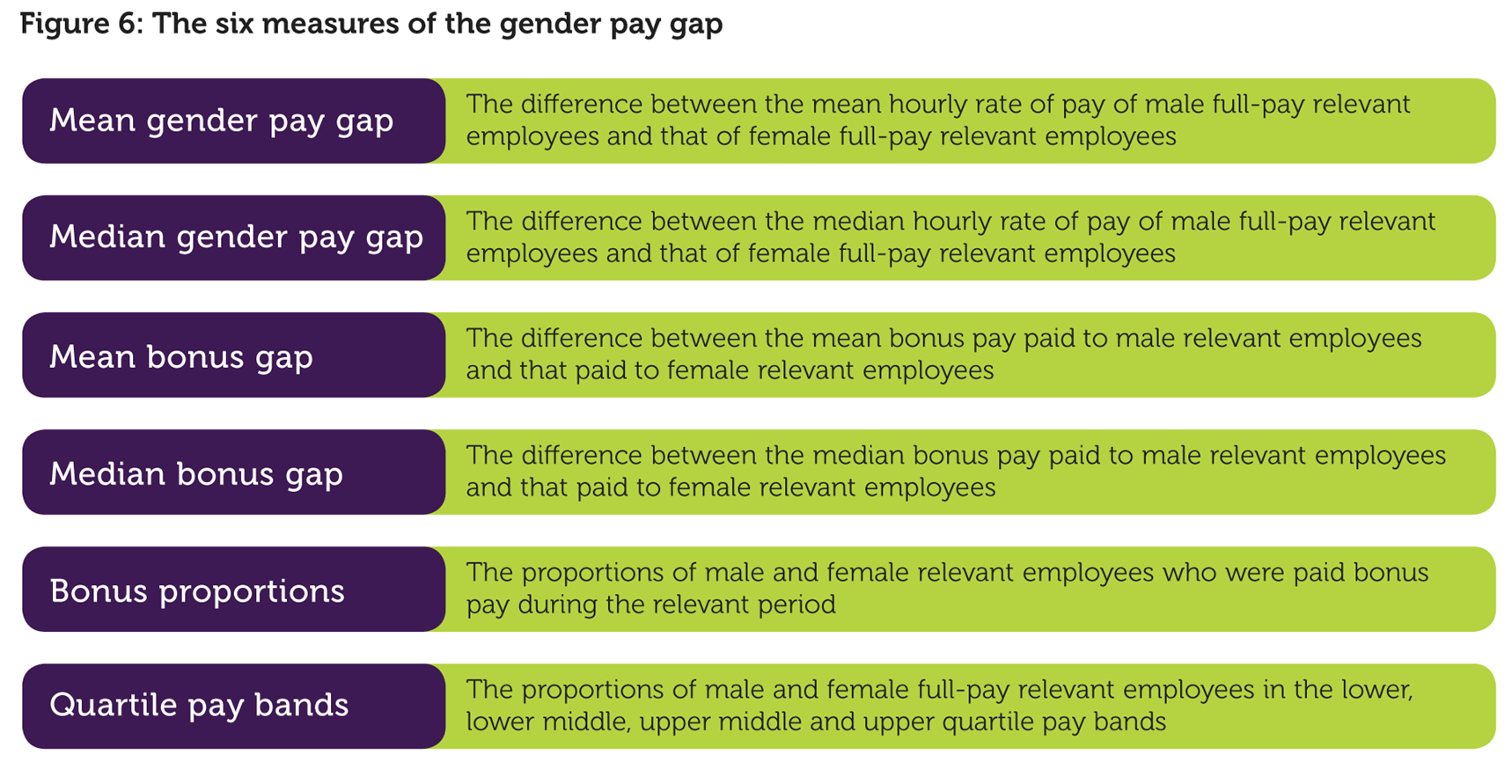

Since 2017/18, public and private sector employers with 250 or more employees have been required annually to publish data on the gender pay gap within their organisations. They must report the data to the Government, who publishes it.

In 2022/23, 79% of reporting employers stated that median hourly pay was higher for men than for women in their organisation, while 13% of employers stated median hourly pay was higher for women. 8% stated that median hourly pay was the same for women as for men.

Related Links

- ONS, Gender Pay Gap 2021

- Commons Library, Women and the economy briefing

Share this with

- Facebook Share this with Facebook

- Twitter Share this with Twitter

- LinkedIn Share this with LinkedIn

- Email Share this with Email

Related posts

Household debt: statistics and impact on economy.

This briefing provides statistics and forecasts for household debt, guidance on how to interpret debt statistics and analysis on how debt effects the economy.

- Economic policy

- Economic situation

Food banks in the UK

The Trussell Trust, an anti-poverty charity that operates a network of food banks across the UK, reported a 37% increase in the number of three-day emergency food parcels it distributed between 31 March 2022 and 1 April 2023, compared to the year before.

- Environment

Key Employment Rights

This briefing provides an overview of a range of key statutory employment rights in Great Britain, including unfair dismissal, deduction from wages and working time.

- Afghanistan Albania Algeria American Samoa Andorra Angola Anguilla Antarctica Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Aruba Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bermuda Bhutan Bolivia Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Bouvet Island Brazil British Indian Ocean Territory Brunei Darussalam Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Canada Cape Verde Cayman Islands Central African Republic Chad Chile China Christmas Island Cocos (Keeling) Islands Colombia Comoros Congo Congo, The Democratic Republic of the Cook Islands CostaRica Croatia Cuba Curaçao Cyprus Czech Republic Côte d'Ivoire Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Faeroe Islands Falkland Islands (Malvinas) Fiji Finland France French Guiana French Polynesia French Southern Territories Gabon Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Gibraltar Greece Greenland Grenada Guadeloupe Guam Guatemala Guernsey Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Heard Island and McDonald Islands Holy See (Vatican City State) Honduras Hong Kong Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iran, Islamic Republic of Iraq Ireland Isle of Man Israel Italy Jamaica Japan Jersey Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati Korea, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Republic of Kosovo Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Lao People's Democratic Republic Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Macau Macedonia, FYR Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Martinique Mauritania Mauritius Mayotte Mexico Micronesia, Fed States of Moldova, Republic of Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Montserrat Morocco Mozambique Myanmar Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands New Caledonia New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Niue Norfolk Island Northern Mariana Islands Norway Oman Pakistan Palau Palestinian Territory Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Pitcairn Poland Portugal Puerto Rico Qatar Reunion Romania Russian Federation Rwanda Saint Barthélemy Saint Helena Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Martin (French part) Saint Pierre and Miquelon Saint Vincent and The Grenadines Samoa San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Sint Maarten Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands Somalia South Africa South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Suriname Svalbard and Jan Mayen Swaziland Sweden Switzerland Syrian Arab Republic Taiwan Tajikistan Tanzania, United Republic of Thailand Timor-Leste Togo Tokelau Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Turks and Caicos Islands Tuvalu Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom United States United States Minor Outlying Islands Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Venezuela Viet Nam VirginIslands (British) VirginIslands (US) Wallis and Futuna Western Sahara Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe

- Sign In My Account

It's not about catching up,

Subscribe to the FT today and navigate your world with confidence.

Explore our plans...

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism. Cancel anytime during your trial.

Decode global events and their impact on your industry with updates and analysis from our worldwide network of 700+ journalists.

Enjoy trusted insights and challenging perspectives from our leading experts.

Stay up to date wherever you are with breaking news alerts, offline reading and automatic downloads of the latest edition

Our new iPhone and iPad app , delivering 8 hand-picked stories every weekday to surprise and inform you.

Start your day with our unmissable morning briefing - the first stop to get you up to speed.

Discover exclusive content and great reads through our expert newsletters, including Inside Politics, Working It and FT Weekend, delivered directly to your inbox.

Track the content that matters to you via your own curated feed .

Watch and listen to the headlines via exclusive interviews, handy explainers and in-depth discussions featuring leading experts.

Share industry-leading content with your colleagues, friends and family for free.

Share more industry-leading content with your colleagues, friends and family for free.

Focus your day with Lex, our agenda-setting column that’s first to highlight emerging risks and opportunities.

Gain valuable insight from our exclusive newsletters including Unhedged, Moral Money and Europe Express, delivered straight to your inbox. Explore our newsletters here.

A digitised version of our current and previous print editions , including FT Weekend, on your desktop, laptop, tablet and mobile.

Standard Digital

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

Premium Digital

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

FT Digital Edition

The new FT Digital Edition: today’s FT, cover to cover on any device. This subscription does not include access to ft.com or the FT App.

Compare our plans Compare our plans

Understand the differences between our plans and find what works best for you. Understand the differences between our plans and find what works best for you.

FT Videos & Podcasts ビデオ&ポッドキャスト More info 表示 Less info 非表示

From the city to the Serengeti, our stories will inform and inspire you to lead the way in business and beyond, to rethink existing political and economic models and follow crucial trends. Included with the Standard Digital and Premium Digital plans.

都会からサバンナまで。FTの記事は、ビジネスやその先の道を切り開き、既存の政治・経済モデルを見直し、重要なトレンドを追うために、あなたに情報とインスピレーションを与えます。 デジタル、スタンダード及びプレミアムプランに含まれます。

Included with: 含まれているもの:

FT App on Android & iOS Android・iOSアプリ More info 表示 Less info 非表示

Our apps allow you to read the FT anywhere, even when you’re offline, never miss a story with breaking news alerts and monitor your portfolio while you're on the move. Included with the Standard Digital and Premium Digital plans.

アプリをダウンロード頂くと、通知を設定すると最新のニュースを入手でき、移動中にポートフォリオも確認することが可能です。 デジタルスタンダードプランまたはプレミアムデジタルプランに含まれています。

FT Edit FT Editアプリ More info 表示 Less info 非表示

The FT Edit app, available for iPhone and iPad, delivers 8 hand-picked stories every weekday to surprise and inspire. Included with the Standard Digital and Premium Digital plans, or available on its own.

平日に、毎日8本の記事を読むことができる最新のiPhone・iPadアプリ。スタンダードデジタルプランまたはプレミアムデジタルプランに含まれていますが、FT Editのみでも購読することが可能です。

Gift Articles 1カ月に10本のギフト記事 More info 表示 Less info 非表示

Share articles with family, friends and colleagues who aren’t subscribers. Up to 10 per month with the Standard Digital plan and up to 20 per month with the Premium Digital plan.

購読者ではない家族・友達・同僚と記事を共有することが可能です。デジタルスタンダードプランの場合は月10本の記事までデジタルプレミアムプランは月20本の記事まで共有可能です。

Lex Lex More info 表示 Less info 非表示

Lex is arguably the world's most influential column of its kind. An award-winning team across four time zones helps readers make better investment decisions by highlighting key risks and opportunities. Included with the Print and Premium Digital plans.

Lexは、世界で最も影響のあるコラムと言えます。4つのタイムゾーンにまたがる受賞歴のあるチームが、主要な投資リスクと機会を強調することで、読者がより良い投資判断を下せるよう支援します。新聞版とデジタルプレミアムプランに含まれます。

Premium Newsletters プレミアム・ニュースレター More info 表示 Less info 非表示

An expansive suite of specialist newsletters providing deep-dive, expert analysis on a broad range of topics from tech to trade. Included with the Premium Digital plan.

テクノロジーから貿易まで、業界の牽引者に執筆される様々なトピックのニュースレターにご購読頂けます。

FT Digital Edition: our digitised print edition ePaper More info 表示 Less info 非表示

An easy-to-navigate digital replica of the weekday print edition and FT Weekend, available on your desktop, laptop, tablet and phone. Included with the Print , FT Digital Edition and Premium Digital plans.

PC、タブレット、スマートフォン等でお気軽にお読み頂ける、紙の新聞の電子レプリカ版。 新聞・ePaper・デジタル版 プレミアムプランに含まれています。

Terms & Conditions apply

Download the FT Edit app on iOS. A daily selection of the very best FT journalism.

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

For individuals.

Discover all the plans currently available in: Russian Federation

Professional

Complete digital access for multiple users, with integrations and admin tools.

Check whether you already have access via your university or organisation

Why the FT?

Global business, politics and so much more..

While the Financial Times is renowned for its award-winning business reporting, the topics we cover are much broader than many realise.

Over 300,000 global finance professionals use the FT’s unique tools, insights, analysis and data to spot trends, risks and opportunities.

Follow the trillions made and lost in tech with crisp analysis, expert opinions and two dedicated newsletters guiding you on the latest trends.

Life & Arts

Get the best out of life with thought-provoking reads, high profile interviews, the latest travel reviews and much more.

Keep abreast of the latest climate-related developments and technologies and understand the stories behind the data.

Work & Careers

Discover the big ideas shaping today’s workplaces with our thoughtful, comprehensive coverage of the new world of work.

Our global network of over 700 journalists work tirelessly to bring you the finest reporting on worldwide events as they unfold.

Expert reporting and opinion.

Our network of 700+ journalists report from all over the world, ensuring a truly global view of key events and decoding their impact on global business, finance, economics and politics.

Roula Khalaf

Roula Khalaf is Editor of the Financial Times. She was previously deputy editor from 2016 to 2020, overseeing a range of newsroom initiatives and award winning editorial projects and leading a global network of over 100 foreign correspondents.

The rumours are true: Orcel on European banking deals

John Burn-Murdoch

John Burn-Murdoch is the Financial Times’ Chief Data Reporter. He led the FT’s data-driven coverage of the pandemic, exploring its impacts on health, the economy and wider society. When pandemics are not happening, he uses data and graphics to tell stories on topics including politics, economics, climate change and sport, and is a visiting lecturer at the London School of Economics.

The seeds of the Tory collapse were sown in 2019

Stephen Bush

Stephen Bush is an associate editor and columnist at the Financial Times. He writes a daily newsletter, Inside Politics, charting the course of politics and policy in the United Kingdom, and a wide-ranging weekly column.

The Lib Dem strategy to restore their third party status

Elaine Moore

Elaine Moore is deputy editor of the FT’s Lex column and writes commentary on the technology industry from the San Francisco bureau. Prior to this she covered global government debt from London, with a particular focus on the debt crisis in Greece, Ukraine and Venezuela.

Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s ‘Napoleon’ sees the chip company soar

Pilita Clark

Pilita Clark is an associate editor and business columnist at the FT where she writes on corporate life and climate change. Formerly the FT’s environment correspondent, her writing has won awards in the US and Asia and in 2019 she was named Environment Journalist of the Year for the third year in a row at the British Press Awards.

Introducing The Economics Show with Soumaya Keynes

Jan Dalley is the FT’s arts editor. She is responsible for the FT’s coverage of all the art forms, from opera to hiphop, sculpture to pop, film, theatre and more in the weekday pages as well as in Life & Arts in FT Weekend. She also writes features, interviews and occasional columns.

Beyond boycotts at the Venice Biennale

Edward Luce

Edward Luce is the US national editor and columnist at the Financial Times. Before that he was the FT's Washington Bureau chief. Other roles have included South Asia bureau chief, Capital Markets editor, and Philippines Correspondent.

Why Nikki Haley still looms over the White House race

Enuma Okoro

Enuma Okoro is a weekly columnist for FT Weekend's Life & Arts. She writes on the intersection of arts, culture and life. Based in New York, she is a writer, speaker and cultural curator.

The beauty and burdens we carry

Anjana Ahuja

Anjana Ahuja is a contributing writer on science, offering weekly opinion on significant developments in global science, health and technology. She was previously a feature writer and columnist at The Times in London.

Hot jobs report suggests US rates could stay higher for longer

Gillian Tett

Gillian Tett is chair of the editorial board and editor-at-large, US of the Financial Times. She writes weekly columns, covering a range of economic, financial, political and social issues and co-founded Moral Money, the FT sustainability newsletter.

FirstFT: Emmanuel Macron calls snap election after Marine Le Pen victory

Rana Foroohar

Rana Foroohar is Global Business Columnist and an Associate Editor at the Financial Times, based in New York. She is also CNN’s global economic analyst.

Janan Ganesh

Janan Ganesh is a biweekly columnist and associate editor for the FT. He writes on international politics for the FT and culture for FT Weekend. He was previously political correspondent for The Economist for five years.

The last best hope against populism is to expose it to government

Robert Shrimsley

Robert Shrimsley is UK chief political commentator and UK editor at large of the Financial Times. He writes a weekly column on British politics and for the FT weekend magazine. Before this, he served as the FT’s chief political correspondent, news editor, managing editor of FT.com and editorial director.

Transcript: Tory morale plunges

Martin Wolf

Martin Wolf is chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, London. He was awarded the CBE (Commander of the British Empire) in 2000 “for services to financial journalism”.

Tariffs are bad policy, but good politics

NEWSLETTERS

Specialist insight from our top writers..

We offer an impressive roster of newsletters, written by our award-winning journalists. These cover a wide range of topics from climate change to finance, American politics to trade - all sent straight to your inbox.

Inside Politics

Stephen Bush’s guide to everything you need to know about power, politics and policy in the United Kingdom.

Robert Armstrong dissects the most important market trends and discusses how Wall Street’s best minds respond to them.

US Election Countdown

Join the FT’s Washington reporter Steff Chávez for your essential guide to the twists and turns of the 2024 presidential election.

Europe Express

Your essential guide to what matters in Europe today, including news on the war in Ukraine.

The Lex Newsletter

Lex is the FT’s incisive daily column on investment. Sign up for our newsletter on local and global trends from expert writers in four great financial centres.

Moral Money

News and analysis on the drive for a fairer, cleaner and more sustainable world economy.

Everything you need to get ahead at work, in your inbox every Wednesday.

FT Swamp Notes

Rana Foroohar and Edward Luce discuss the intersection of money and power in US politics.

Martin Sandbu’s Free Lunch

Your weekly guide to the global economic policy debate, written by our European Economics Commentator.

VIDEOS & PODCASTS

Be informed and inspired by our audiovisual journalism..

From the city to the Serengeti, our stories will inform and inspire you to lead the way in business and beyond, to rethink existing political and economic models and follow crucial trends.

Hedge funds

Crispin Odey: the fall of a hedge fund maverick

FT Standpoint

Capture: who's looking after the children?

Cryptocurrencies

FTX: the legend of Sam Bankman-Fried

The Brexit effect: how leaving the EU hit the UK

News in-depth

Credit Suisse: what next for the crisis-hit bank?

North Korea and the triads: gangsters, ghost ships and spies

From personalisation to portfolio planning.

A Financial Times subscription gives you so much more than just award-winning reporting, commentary and analysis. Take advantage of our range of complimentary tools to maximise the value of your investment.

Saved articles

Save articles of interest to your myFT account with a single click for easy recall.

Instant alerts

Never miss a story with instant alerts on the topics, stories and journalists that matter to you most.

Gift articles

Share articles with friends, family and colleagues who aren't subscribers with unique gift links.

Monitor performance and view relevant news stories and fundamentals related to your holdings portfolio.

Engage with our global community of journalists and subscribers and add your voice to the conversation.

Currency Converter

Browse news and rates across dozens of currencies, or select a currency pair for spot rate charting and data.

Track the topics, stories and journalists that matter to you most in your own personalised news feed.

Republishing

Leverage the power of FT journalism by republishing our content to your website or publication. Additional fees apply.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Browse content in A - General Economics and Teaching

- Browse content in A1 - General Economics

- A10 - General

- A11 - Role of Economics; Role of Economists; Market for Economists

- A12 - Relation of Economics to Other Disciplines

- A13 - Relation of Economics to Social Values

- A14 - Sociology of Economics

- Browse content in A2 - Economic Education and Teaching of Economics

- A20 - General

- A23 - Graduate

- Browse content in A3 - Collective Works

- A31 - Collected Writings of Individuals

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B0 - General

- B00 - General

- Browse content in B1 - History of Economic Thought through 1925

- B10 - General

- B12 - Classical (includes Adam Smith)

- B16 - History of Economic Thought: Quantitative and Mathematical

- Browse content in B2 - History of Economic Thought since 1925

- B22 - Macroeconomics

- B26 - Financial Economics

- B27 - International Trade and Finance

- B29 - Other

- Browse content in B3 - History of Economic Thought: Individuals

- B31 - Individuals

- Browse content in B4 - Economic Methodology

- B40 - General

- B41 - Economic Methodology

- Browse content in B5 - Current Heterodox Approaches

- B50 - General

- B52 - Institutional; Evolutionary

- B54 - Feminist Economics

- B55 - Social Economics

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C0 - General

- C02 - Mathematical Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C10 - General

- C11 - Bayesian Analysis: General

- C13 - Estimation: General

- C14 - Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods: General

- C15 - Statistical Simulation Methods: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C20 - General

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- C22 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes

- C23 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- Browse content in C4 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: Special Topics

- C45 - Neural Networks and Related Topics

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C50 - General

- C51 - Model Construction and Estimation

- C53 - Forecasting and Prediction Methods; Simulation Methods

- C54 - Quantitative Policy Modeling

- C55 - Large Data Sets: Modeling and Analysis

- Browse content in C6 - Mathematical Methods; Programming Models; Mathematical and Simulation Modeling

- C61 - Optimization Techniques; Programming Models; Dynamic Analysis

- C63 - Computational Techniques; Simulation Modeling

- C68 - Computable General Equilibrium Models

- Browse content in C7 - Game Theory and Bargaining Theory

- C72 - Noncooperative Games

- C78 - Bargaining Theory; Matching Theory

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C80 - General

- C81 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Microeconomic Data; Data Access

- C88 - Other Computer Software

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C90 - General

- C93 - Field Experiments

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D00 - General

- D01 - Microeconomic Behavior: Underlying Principles

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- D04 - Microeconomic Policy: Formulation; Implementation, and Evaluation

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D10 - General

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- D15 - Intertemporal Household Choice: Life Cycle Models and Saving

- D18 - Consumer Protection

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D21 - Firm Behavior: Theory

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D23 - Organizational Behavior; Transaction Costs; Property Rights

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D30 - General

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- D33 - Factor Income Distribution

- Browse content in D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- D40 - General

- D42 - Monopoly

- D43 - Oligopoly and Other Forms of Market Imperfection

- D44 - Auctions

- D45 - Rationing; Licensing

- D47 - Market Design

- Browse content in D5 - General Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

- D50 - General

- D51 - Exchange and Production Economies

- D53 - Financial Markets

- D57 - Input-Output Tables and Analysis

- D58 - Computable and Other Applied General Equilibrium Models

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D60 - General

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- D64 - Altruism; Philanthropy

- D69 - Other

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D70 - General

- D71 - Social Choice; Clubs; Committees; Associations

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- D78 - Positive Analysis of Policy Formulation and Implementation

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D81 - Criteria for Decision-Making under Risk and Uncertainty

- D82 - Asymmetric and Private Information; Mechanism Design

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D84 - Expectations; Speculations

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D90 - General

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice, Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E0 - General

- E00 - General

- E01 - Measurement and Data on National Income and Product Accounts and Wealth; Environmental Accounts

- E02 - Institutions and the Macroeconomy

- E03 - Behavioral Macroeconomics

- Browse content in E1 - General Aggregative Models

- E10 - General

- E12 - Keynes; Keynesian; Post-Keynesian

- E13 - Neoclassical

- E17 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E21 - Consumption; Saving; Wealth

- E22 - Investment; Capital; Intangible Capital; Capacity

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- E25 - Aggregate Factor Income Distribution

- E26 - Informal Economy; Underground Economy

- E27 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E3 - Prices, Business Fluctuations, and Cycles

- E30 - General

- E31 - Price Level; Inflation; Deflation

- E32 - Business Fluctuations; Cycles

- E37 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E40 - General

- E42 - Monetary Systems; Standards; Regimes; Government and the Monetary System; Payment Systems

- E43 - Interest Rates: Determination, Term Structure, and Effects

- E44 - Financial Markets and the Macroeconomy

- E47 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E50 - General

- E51 - Money Supply; Credit; Money Multipliers

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E60 - General

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E63 - Comparative or Joint Analysis of Fiscal and Monetary Policy; Stabilization; Treasury Policy

- E64 - Incomes Policy; Price Policy

- E65 - Studies of Particular Policy Episodes

- E66 - General Outlook and Conditions

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F0 - General

- F00 - General

- F02 - International Economic Order and Integration

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F11 - Neoclassical Models of Trade

- F12 - Models of Trade with Imperfect Competition and Scale Economies; Fragmentation

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- F16 - Trade and Labor Market Interactions

- F17 - Trade Forecasting and Simulation

- F18 - Trade and Environment

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F20 - General

- F21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital Movements

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- F24 - Remittances

- F29 - Other

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F30 - General

- F31 - Foreign Exchange

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F33 - International Monetary Arrangements and Institutions

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F35 - Foreign Aid

- F36 - Financial Aspects of Economic Integration

- F37 - International Finance Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- F38 - International Financial Policy: Financial Transactions Tax; Capital Controls

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F40 - General

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- F45 - Macroeconomic Issues of Monetary Unions

- F47 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F50 - General

- F51 - International Conflicts; Negotiations; Sanctions

- F52 - National Security; Economic Nationalism

- F53 - International Agreements and Observance; International Organizations

- F55 - International Institutional Arrangements

- F59 - Other

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F60 - General

- F61 - Microeconomic Impacts

- F62 - Macroeconomic Impacts

- F63 - Economic Development

- F64 - Environment

- F65 - Finance

- F66 - Labor

- F68 - Policy

- F69 - Other

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions

- G12 - Asset Pricing; Trading volume; Bond Interest Rates

- G13 - Contingent Pricing; Futures Pricing

- G14 - Information and Market Efficiency; Event Studies; Insider Trading

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- G17 - Financial Forecasting and Simulation

- G18 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G24 - Investment Banking; Venture Capital; Brokerage; Ratings and Ratings Agencies

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G31 - Capital Budgeting; Fixed Investment and Inventory Studies; Capacity

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G34 - Mergers; Acquisitions; Restructuring; Corporate Governance

- G35 - Payout Policy

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- G39 - Other

- Browse content in G4 - Behavioral Finance

- G41 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making in Financial Markets

- Browse content in G5 - Household Finance

- G50 - General

- G51 - Household Saving, Borrowing, Debt, and Wealth

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H0 - General

- H00 - General

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H10 - General

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- H12 - Crisis Management

- H13 - Economics of Eminent Domain; Expropriation; Nationalization

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H20 - General

- H21 - Efficiency; Optimal Taxation

- H22 - Incidence

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H24 - Personal Income and Other Nonbusiness Taxes and Subsidies; includes inheritance and gift taxes

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- H29 - Other

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H30 - General

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H41 - Public Goods

- H43 - Project Evaluation; Social Discount Rate

- H44 - Publicly Provided Goods: Mixed Markets

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H50 - General

- H51 - Government Expenditures and Health

- H52 - Government Expenditures and Education

- H53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare Programs

- H54 - Infrastructures; Other Public Investment and Capital Stock

- H55 - Social Security and Public Pensions

- H56 - National Security and War

- H57 - Procurement

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H60 - General

- H62 - Deficit; Surplus

- H63 - Debt; Debt Management; Sovereign Debt

- H68 - Forecasts of Budgets, Deficits, and Debt

- H69 - Other

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H70 - General

- H71 - State and Local Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H73 - Interjurisdictional Differentials and Their Effects

- H75 - State and Local Government: Health; Education; Welfare; Public Pensions

- H77 - Intergovernmental Relations; Federalism; Secession

- Browse content in H8 - Miscellaneous Issues

- H81 - Governmental Loans; Loan Guarantees; Credits; Grants; Bailouts

- H83 - Public Administration; Public Sector Accounting and Audits

- H84 - Disaster Aid

- H87 - International Fiscal Issues; International Public Goods

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I0 - General

- I00 - General

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I10 - General

- I11 - Analysis of Health Care Markets

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I14 - Health and Inequality

- I15 - Health and Economic Development

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- I19 - Other

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I20 - General

- I21 - Analysis of Education

- I23 - Higher Education; Research Institutions

- I24 - Education and Inequality

- I26 - Returns to Education

- I28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in I3 - Welfare, Well-Being, and Poverty

- I30 - General

- I31 - General Welfare

- I32 - Measurement and Analysis of Poverty

- I38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J00 - General

- J01 - Labor Economics: General

- J08 - Labor Economics Policies

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J11 - Demographic Trends, Macroeconomic Effects, and Forecasts

- J12 - Marriage; Marital Dissolution; Family Structure; Domestic Abuse

- J13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth

- J14 - Economics of the Elderly; Economics of the Handicapped; Non-Labor Market Discrimination

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- J17 - Value of Life; Forgone Income

- J18 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J20 - General

- J21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and Structure

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J23 - Labor Demand

- J24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor Productivity

- J26 - Retirement; Retirement Policies

- J28 - Safety; Job Satisfaction; Related Public Policy

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J31 - Wage Level and Structure; Wage Differentials

- J33 - Compensation Packages; Payment Methods

- J38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J40 - General

- J41 - Labor Contracts

- J44 - Professional Labor Markets; Occupational Licensing

- J46 - Informal Labor Markets

- J48 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J5 - Labor-Management Relations, Trade Unions, and Collective Bargaining

- J58 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J60 - General

- J61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant Workers

- J62 - Job, Occupational, and Intergenerational Mobility

- J63 - Turnover; Vacancies; Layoffs

- J64 - Unemployment: Models, Duration, Incidence, and Job Search

- J65 - Unemployment Insurance; Severance Pay; Plant Closings

- J68 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J7 - Labor Discrimination

- J70 - General

- J71 - Discrimination

- Browse content in J8 - Labor Standards: National and International

- J88 - Public Policy

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K0 - General

- K00 - General

- Browse content in K1 - Basic Areas of Law

- K10 - General

- K11 - Property Law

- K12 - Contract Law

- Browse content in K2 - Regulation and Business Law

- K20 - General

- K21 - Antitrust Law

- K22 - Business and Securities Law

- K29 - Other

- Browse content in K3 - Other Substantive Areas of Law

- K31 - Labor Law

- K32 - Environmental, Health, and Safety Law

- K33 - International Law

- K34 - Tax Law

- K37 - Immigration Law

- K38 - Human Rights Law: Gender Law

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K40 - General

- K41 - Litigation Process

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- K49 - Other

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L12 - Monopoly; Monopolization Strategies

- L13 - Oligopoly and Other Imperfect Markets

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- L16 - Industrial Organization and Macroeconomics: Industrial Structure and Structural Change; Industrial Price Indices

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L21 - Business Objectives of the Firm

- L22 - Firm Organization and Market Structure

- L24 - Contracting Out; Joint Ventures; Technology Licensing

- L25 - Firm Performance: Size, Diversification, and Scope

- L26 - Entrepreneurship

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L31 - Nonprofit Institutions; NGOs; Social Entrepreneurship

- L33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises and Nonprofit Institutions; Privatization; Contracting Out

- L38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in L4 - Antitrust Issues and Policies

- L40 - General

- L41 - Monopolization; Horizontal Anticompetitive Practices

- L42 - Vertical Restraints; Resale Price Maintenance; Quantity Discounts

- Browse content in L5 - Regulation and Industrial Policy

- L50 - General

- L51 - Economics of Regulation

- L52 - Industrial Policy; Sectoral Planning Methods

- L53 - Enterprise Policy

- L59 - Other

- Browse content in L6 - Industry Studies: Manufacturing

- L60 - General

- L65 - Chemicals; Rubber; Drugs; Biotechnology

- Browse content in L7 - Industry Studies: Primary Products and Construction

- L71 - Mining, Extraction, and Refining: Hydrocarbon Fuels

- Browse content in L8 - Industry Studies: Services

- L80 - General

- L81 - Retail and Wholesale Trade; e-Commerce

- L86 - Information and Internet Services; Computer Software

- L88 - Government Policy

- Browse content in L9 - Industry Studies: Transportation and Utilities

- L90 - General

- L92 - Railroads and Other Surface Transportation

- L94 - Electric Utilities

- L98 - Government Policy

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M1 - Business Administration

- M10 - General

- M11 - Production Management

- M12 - Personnel Management; Executives; Executive Compensation

- M13 - New Firms; Startups

- M14 - Corporate Culture; Social Responsibility

- M16 - International Business Administration

- M2 - Business Economics

- Browse content in M4 - Accounting and Auditing

- M41 - Accounting

- M42 - Auditing

- M48 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M50 - General

- M51 - Firm Employment Decisions; Promotions

- M53 - Training

- M54 - Labor Management

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- Browse content in N1 - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics; Industrial Structure; Growth; Fluctuations

- N10 - General, International, or Comparative

- N12 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N13 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N14 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in N2 - Financial Markets and Institutions

- N20 - General, International, or Comparative

- N23 - Europe: Pre-1913

- Browse content in N3 - Labor and Consumers, Demography, Education, Health, Welfare, Income, Wealth, Religion, and Philanthropy

- N33 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N34 - Europe: 1913-

- N36 - Latin America; Caribbean

- N37 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N4 - Government, War, Law, International Relations, and Regulation

- N44 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in N5 - Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Extractive Industries

- N55 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N6 - Manufacturing and Construction

- N60 - General, International, or Comparative

- N64 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in N7 - Transport, Trade, Energy, Technology, and Other Services

- N70 - General, International, or Comparative

- Browse content in N9 - Regional and Urban History

- N94 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O10 - General

- O11 - Macroeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary Products

- O14 - Industrialization; Manufacturing and Service Industries; Choice of Technology

- O15 - Human Resources; Human Development; Income Distribution; Migration

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements

- O18 - Urban, Rural, Regional, and Transportation Analysis; Housing; Infrastructure

- O19 - International Linkages to Development; Role of International Organizations

- Browse content in O2 - Development Planning and Policy

- O20 - General

- O21 - Planning Models; Planning Policy

- O22 - Project Analysis

- O23 - Fiscal and Monetary Policy in Development

- O24 - Trade Policy; Factor Movement Policy; Foreign Exchange Policy

- O25 - Industrial Policy

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O30 - General

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O32 - Management of Technological Innovation and R&D

- O33 - Technological Change: Choices and Consequences; Diffusion Processes

- O34 - Intellectual Property and Intellectual Capital

- O35 - Social Innovation

- O38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate Productivity

- O40 - General

- O41 - One, Two, and Multisector Growth Models

- O42 - Monetary Growth Models

- O43 - Institutions and Growth

- O44 - Environment and Growth

- O47 - Empirical Studies of Economic Growth; Aggregate Productivity; Cross-Country Output Convergence

- O49 - Other

- Browse content in O5 - Economywide Country Studies

- O51 - U.S.; Canada

- O52 - Europe

- O53 - Asia including Middle East

- O55 - Africa

- O57 - Comparative Studies of Countries

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P0 - General

- P00 - General

- Browse content in P1 - Capitalist Systems

- P10 - General

- P12 - Capitalist Enterprises

- P14 - Property Rights

- P16 - Political Economy

- P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional Economies

- Browse content in P3 - Socialist Institutions and Their Transitions

- P30 - General

- P36 - Consumer Economics; Health; Education and Training; Welfare, Income, Wealth, and Poverty

- Browse content in P4 - Other Economic Systems

- P46 - Consumer Economics; Health; Education and Training; Welfare, Income, Wealth, and Poverty

- P48 - Political Economy; Legal Institutions; Property Rights; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Regional Studies

- Browse content in P5 - Comparative Economic Systems

- P50 - General

- P51 - Comparative Analysis of Economic Systems

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q0 - General

- Q00 - General

- Q01 - Sustainable Development

- Q02 - Commodity Markets

- Browse content in Q1 - Agriculture

- Q10 - General

- Q11 - Aggregate Supply and Demand Analysis; Prices

- Q12 - Micro Analysis of Farm Firms, Farm Households, and Farm Input Markets

- Q13 - Agricultural Markets and Marketing; Cooperatives; Agribusiness

- Q14 - Agricultural Finance

- Q15 - Land Ownership and Tenure; Land Reform; Land Use; Irrigation; Agriculture and Environment

- Q17 - Agriculture in International Trade

- Q18 - Agricultural Policy; Food Policy

- Browse content in Q2 - Renewable Resources and Conservation

- Q20 - General

- Q21 - Demand and Supply; Prices

- Q23 - Forestry

- Q25 - Water

- Q27 - Issues in International Trade

- Q28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q3 - Nonrenewable Resources and Conservation

- Q30 - General

- Q32 - Exhaustible Resources and Economic Development

- Q33 - Resource Booms

- Q34 - Natural Resources and Domestic and International Conflicts

- Q35 - Hydrocarbon Resources

- Q38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q4 - Energy

- Q40 - General

- Q41 - Demand and Supply; Prices

- Q42 - Alternative Energy Sources

- Q43 - Energy and the Macroeconomy

- Q48 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q50 - General

- Q51 - Valuation of Environmental Effects

- Q52 - Pollution Control Adoption Costs; Distributional Effects; Employment Effects

- Q53 - Air Pollution; Water Pollution; Noise; Hazardous Waste; Solid Waste; Recycling

- Q54 - Climate; Natural Disasters; Global Warming

- Q55 - Technological Innovation

- Q56 - Environment and Development; Environment and Trade; Sustainability; Environmental Accounts and Accounting; Environmental Equity; Population Growth

- Q57 - Ecological Economics: Ecosystem Services; Biodiversity Conservation; Bioeconomics; Industrial Ecology

- Q58 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R10 - General

- R11 - Regional Economic Activity: Growth, Development, Environmental Issues, and Changes

- R12 - Size and Spatial Distributions of Regional Economic Activity

- R14 - Land Use Patterns

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R21 - Housing Demand

- R23 - Regional Migration; Regional Labor Markets; Population; Neighborhood Characteristics

- R28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R30 - General

- R31 - Housing Supply and Markets

- R32 - Other Spatial Production and Pricing Analysis

- R38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R4 - Transportation Economics

- R40 - General

- R41 - Transportation: Demand, Supply, and Congestion; Travel Time; Safety and Accidents; Transportation Noise

- R42 - Government and Private Investment Analysis; Road Maintenance; Transportation Planning

- R48 - Government Pricing and Policy

- Browse content in R5 - Regional Government Analysis

- R50 - General

- R51 - Finance in Urban and Rural Economies

- R52 - Land Use and Other Regulations

- R53 - Public Facility Location Analysis; Public Investment and Capital Stock

- R58 - Regional Development Planning and Policy

- Browse content in Z - Other Special Topics

- Browse content in Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology

- Z13 - Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology; Social and Economic Stratification

- Z18 - Public Policy

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Oxford Review of Economic Policy

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

I.introduction, iii.descriptive analysis, viii.concluding remarks, acknowledgement.

- < Previous

The gender pay gap in the UK: children and experience in work

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Monica Costa Dias, Robert Joyce, Francesca Parodi, The gender pay gap in the UK: children and experience in work, Oxford Review of Economic Policy , Volume 36, Issue 4, Winter 2020, Pages 855–881, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/graa053

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In this study, we document the evolution of the gender pay gap in the UK over the past three decades and its association with fertility, examining the role of various differences in career patterns between men and women and how they change with the arrival of the first child. We show that differences in accumulated years of labour market experience play an important role, while differences in industry, occupation, and job characteristics explain less, conditional on working experience. We develop an empirical wage model to estimate the causal effect of working experience on the wages of women. Estimates from this model are then used to simulate two counterfactual scenarios in which women who are employed always work full-time, or women’s rates of both part-time and full-time work are the same as men’s. We find that differences in working experience explain up to two-thirds of the gender pay gap of college graduates 20 years after the first childbirth, and that the gap is largely driven by differences in full-time experience. The role of working experience is more moderate for individuals with no college education, but it can still account for about one-third of the overall long-term gender wage gap.

Gender differences in earnings are essentially universal across countries. Within the developed world those gaps have tended to fall greatly over the last century, although progress has stalled in recent decades and the gaps remain sizeable ( Goldin, 2014 ; Blau and Kahn, 2017). The opening of the pay gap happens gradually over the course of life and is strongly related with the arrival of children and its strong negative effects on the hourly wage rates, employment rates, and hours of paid work of women (Paull, 2008; Adda et al ., 2017; Kleven et al ., 2019 a ).

Countries differ significantly in the relative importance of these determinants of the gender pay gap. Figure 1 shows the wide cross-country variation in the employment and working hours of mothers. For instance, Scandinavian and northern European countries have the highest maternal employment rates, almost 30 percentage points higher than the employment rates in some of the southern European countries, such as Greece and Italy, and over 50 percentage points higher than employment rates in Turkey. The employment rates of mothers in English-speaking countries tend to fall in the middle of the table, close to the average for OECD and EU countries. In some countries, including Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, and the UK, a large fraction of working mothers do short working hours, while in other places, including the Scandinavian countries, most mothers in work do full-time hours.

Maternal employment rates across OECD countries Note : Data from OECD Family Database. Shows PT–FT (part time–full time) employment rates (%) of women aged 15–64 with at least one child aged 0–14 in 2014 or latest available year.

Recent research (Kleven et al ., 2019 a ) also documented that in countries where mothers stay longer out of work after childbirth, such as the US and UK as compared to the Scandinavian countries, the drop in women’s earnings relative to men’s persists for longer after childbirth. This is partly the mechanical effect of mothers continuing to work less than fathers do many years after their first child is born, and partly a consequence of the price of labour as measured by the wage rate per hour being differentially affected by parenthood for mothers and fathers.

In this paper we investigate some of the drivers of the gender wage gap among parents. We document that the gap in hourly wages does not open immediately after childbirth, contrary to what happens to earnings, but instead widens gradually as the child grows up. We then consider two mechanisms that can partly account for that gradual but permanent opening of the gender wage gap. First, taking time away from paid work and working short hours—two prevalent features of maternal, but not paternal, labour supply—may inhibit the wage growth of women through skill depreciation, slow accumulation of skills, or lack of career progression, hence denting their future earnings capacity persistently. Second, mothers and fathers sort into different types of jobs—in different industries, occupations, and offering a different set of amenities such as flexibility in working hours—perhaps because of how difficult or easy it is to combine such jobs with the responsibilities of parenthood. If mothers cluster into jobs that can easily be coordinated with their childcare responsibilities, even if at the cost of higher pay, while fathers assume the main bread-winner role and sort into high-paying jobs, the resulting diverging careers could be reflected in diverging wage profiles. These two mechanisms are likely to lead to a gradual accumulation of persistent losses in the wage rates of mothers as compared to fathers and contribute to explaining the widening of the gender wage gap after childbirth. They are also likely related. Indeed, mothers who take time away from paid work may see their prospects of progressing to higher paying jobs curtailed, at least partly as they fail to accumulate the working experience they need to progress.

Using longitudinal data for the UK spanning the 27 years that start in 1991, we assess the quantitative importance of these mechanisms. We find that ‘experience capital’ gained in work has the potential to account for a large share of the gender wage gap, including the way that it evolves over the life cycle. In contrast, conditionally on accumulated working experience, the different job characteristics (including industry and occupation) in which fathers and mothers concentrate do not further explain much of the opening of the gap after childbirth. This is not to say that sorting into jobs with different characteristics is not an important driver of the gender gap in wages. Instead, our result reflects that gender differences in job sorting happen together with the expansion in the gender experience gap, as mothers taking time away from paid work fail to progress in their careers and may even move down the job ladder.

Building on this evidence, we set up and estimate an empirical model of wage dynamics that allows us to assess the causal impact of accumulated work experience capital on the wage progression of women over their life-cycle. Our model formalizes, in a flexible way, the intertemporal connection between hourly wages and labour supply at the extensive and intensive margins. In particular, it accounts for the possibility that working part-time hours impacts hourly wages not only today, but also in future years by having implications for wage progression that are different from those of full-time work. It also allows for depreciation in experience capital during periods of no work. Given the importance of education in driving labour market outcomes, we fully interact our model with education attainment. We consider three education levels, corresponding to less than high-school qualifications, high-school qualifications, and university degree. To deal with endogenous participation and hours selection, we adopt a control function approach exploiting the many policy reforms that changed the incentives to work of mothers over the period covered by the data. For exclusion restrictions we use simulated family disposable income variables that are constructed for different working hours of the woman (Blundell et al ., 1998).

We find that working full-time hours is a key determinant of wage progression, particularly for women earlier in the career. Moreover, there is a clear positive education gradient on the impact of working full-time hours on wage growth. This means that educated women have more to gain from working full-time hours but also that they are the ones who have most to lose from not doing so. In contrast, we find no statistically significant impact of working part-time hours.

Our model can be used to simulate the role of experience losses in explaining the opening of the gender wage gap after the birth of the first child. We do so in two counterfactual simulations: the first simulation imposes that employed women always work full-time, and the second simulation further imposes that women are paid for their work at the same rate of men. For university graduates we find that losses in working experience after the birth of the first child can explain up to two-thirds of the opening of the gap in wages when the child reaches 20 years of age. This is not merely because mothers spend more time out of the labour force after childbirth than fathers; it is also because, when in paid work, they are likely to work shorter hours, and part-time work shuts down progression in hourly wages. The role of working experience is more moderate for individuals with no university education, but it can still account for about one-third of the overall gender wage gap 20 years after childbirth.

Some of the channels we investigate have been studied in the large empirical literature on gender gaps. For instance, Bertrand et al . (2010) identify career interruptions and working hours as key drivers of the pay gap among MBA graduates; Goldin, (2014) discusses the high penalty from career breaks and flexibility in some high-wage occupations as drivers of the persisting gender wage gap; Blau and Kahn (2017) find that the three most important factors explaining the current gender wage gap in the US are occupation, industry, and experience; Kleven et al . (2019 b ) point to occupation, sector, and firm choices as mechanisms driving child penalties in Denmark. Our study adds to this literature by considering the causal impact of current working choices on wage growth and how these effects cumulate over time to explain the gradual opening of the gender wage gap after childbirth. We also document that other mechanisms, such as occupation, industry, or specific job characteristics, are comparatively less important once cumulative differences in working experience are accounted for.

One other set of papers uses structural models of the life-cycle to study female labour supply and wages. Among others, Olivetti (2006) builds a life-cycle model with human capital accumulation and home production to investigate the change in women’s supply of hours of market work; Attanasio et al . (2008) construct a life-cycle model of female participation decisions and savings with a process for human capital accumulation that accounts for periods out of work; Blundell et al . (2016) estimate a dynamic model of employment, human capital accumulation, and savings for women and use it to analyse the effects of welfare policy in the UK; Adda et al . (2017) model fertility and labour supply decisions of women over the life-cycle to quantify the long-run impact of fertility incentivizing policies. We depart from these papers by adopting a more flexible empirical model that is nevertheless well suited to quantify the role of present and past experiences in work in explaining female wage dynamics. We then use our framework to study the extent to which our mechanisms explain gender differences in pay among parents. 1

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section II describes the data and defines the main variables. Section III shows descriptive evidence on the evolution of the gender pay gap and its relation to childbirth and to the different working lives of mothers and fathers. It then shows that opening differences in experience capital are strongly related with the growing gender pay gap after childbirth. Section IV outlines the econometric model and estimation technique we use to identify the causal impact of working experience on the wages of women. Section V reports the empirical estimates and section VI discusses the model predictions by simulating counterfactual wage gaps if women were to work at the same rate as men do. Section VII suggests policy implications. Finally, section VIII draws some concluding remarks.

We use two data sources for our empirical analysis. All analysis requiring longitudinal data is based on the UK Household Longitudinal Study (UKHLS). This is a combination of two panel studies of families with the same structure and overlapping samples, the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) and the Understanding Society (USoc). 2 The UKHLS has been following the lives of families and their offshoots since 1991. The survey started with a representative sample of 5,050 households living in Great Britain; it was later replenished in 1997 and 2001 with 1,000 households from the former European Community Household Panel, in 1999 with two samples of 1,500 households each from the Welsh and Scottish extensions, and in 2001 with the first set of households from Northern Ireland, totalling 1,900. It has undergone a large expansion and restructuring in 2009 that was marked with the adoption of its new label, USoc. Some 40,000 new families were added from across the UK. Except for attrition—which was particularly large in the transition between the two studies in 2009, affecting just over 30 per cent of the existing sample—all household members in the original samples remain in the sample until the end of the period, which for this paper is 2017. Other individuals have also been added to the sample, as they formed families with original members of the panel or were born into them. In our analysis, we exclude families living in Northern Ireland as the region is only sampled from 2001 onwards.

All members of the household aged 16 and above are interviewed yearly, and a large set of demographic, education, and labour-market information is recorded. The UKHLS also collects historical information documenting the history of full-time and part-time employment and the socio-economic environment of the parental household of each interviewee.

We use the sub-sample of individuals observed during their main working years, between the ages of 20 and 55, after they left full-time education. In each annual wave, the UKHLS collects information on employment status, usual weekly working hours, paid and unpaid overtime, and gross pay including for overtime. We discretize the distribution of working hours into three bins that we label as no-work (4 hours per week or fewer), part-time work (5–24 weekly hours), and full-time work (25 and more weekly hours). Those who report being disabled or long-term sick are dropped from the sample.

Table 1 shows the sample sizes in UKHLS for our population of interest. Overall, our sample includes almost 150,000 observations of over 27,000 individuals. Among these, over 7,000 were first interviewed in the BHPS period, prior to 2009, of which just over 1,400 are present in both periods. The median length of the observation period is 6 years, though it is longer for those who enter the sample earlier during the BHPS period, particularly if followed into the USoc period.

UKHLS—sample sizes and distribution of education

| . | Men . | Women . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size: number of individuals | |||

| All | 11,899 | 15,144 | 27,043 |

| In BHPS | 3,112 | 3,985 | 7,097 |

| In BHPS and USoc | 630 | 778 | 1,408 |

| Sample size: number of observations | |||

| All | 63,159 | 84,062 | 147,221 |

| In BHPS | 23,841 | 31,732 | 55,573 |

| In BHPS and USoc | 8,825 | 11,069 | 19,894 |

| Median duration of observation spells (years) | |||

| All | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| In BHPS | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| In BHPS and USoc | 18 | 19 | 18 |

| Distribution of education | |||

| GCSEs | 0.460 | 0.474 | 0.468 |

| A-levels | 0.404 | 0.417 | 0.412 |

| University degree | 0.136 | 0.109 | 0.121 |

| . | Men . | Women . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size: number of individuals | |||

| All | 11,899 | 15,144 | 27,043 |

| In BHPS | 3,112 | 3,985 | 7,097 |

| In BHPS and USoc | 630 | 778 | 1,408 |

| Sample size: number of observations | |||

| All | 63,159 | 84,062 | 147,221 |

| In BHPS | 23,841 | 31,732 | 55,573 |

| In BHPS and USoc | 8,825 | 11,069 | 19,894 |

| Median duration of observation spells (years) | |||

| All | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| In BHPS | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| In BHPS and USoc | 18 | 19 | 18 |

| Distribution of education | |||

| GCSEs | 0.460 | 0.474 | 0.468 |

| A-levels | 0.404 | 0.417 | 0.412 |

| University degree | 0.136 | 0.109 | 0.121 |

Notes: The row labels ‘all’, ‘in BHPS’, and ‘in BHPS and USoc’ stand for, respectively, the entire UKHLS sample used in this study, the subset of individuals who enter the sample prior to 2009, and the subset of individuals who enter the sample prior to 2009 and remain until after 2009 or later.

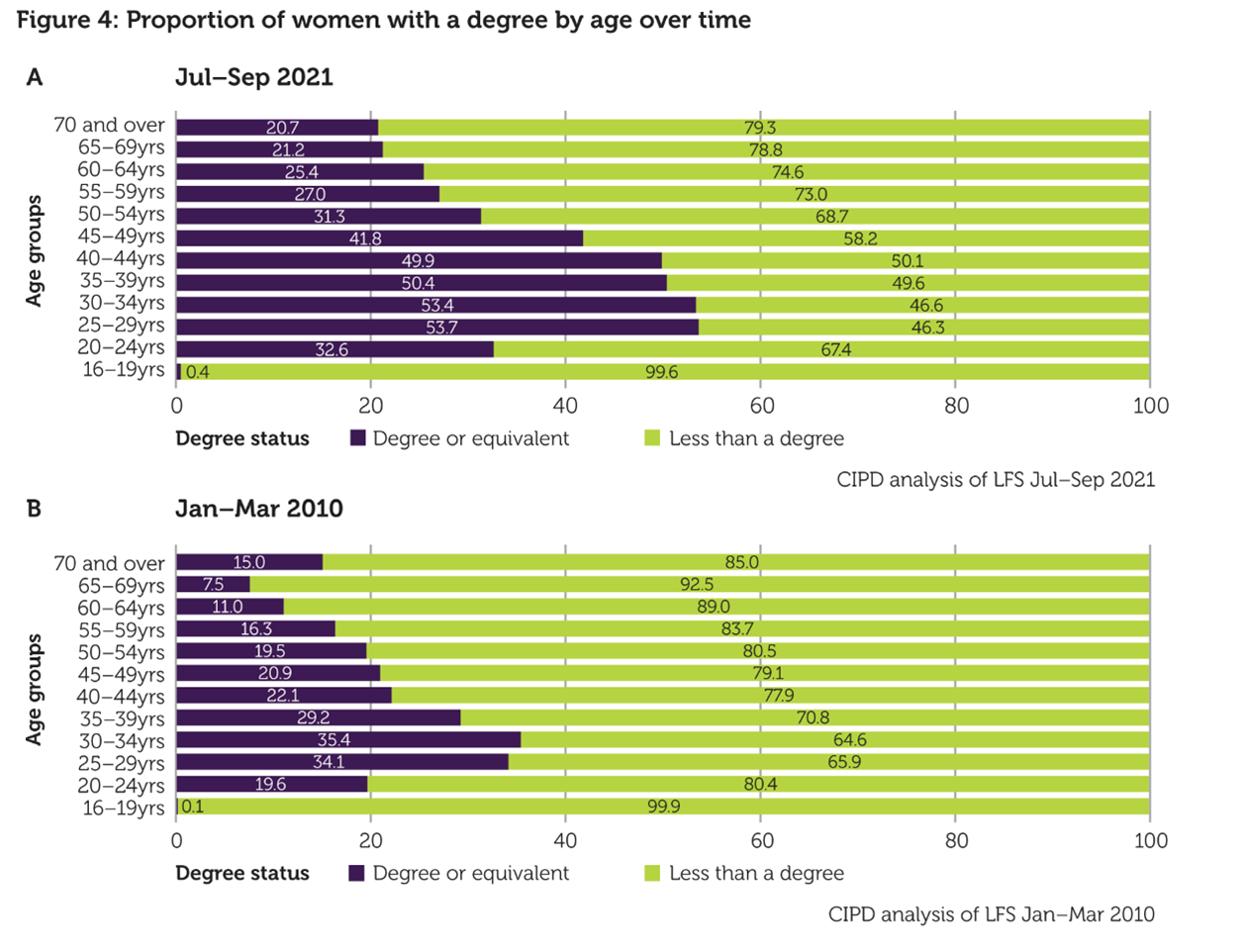

We consider three education groups: GCSEs, representing those who leave education at 16 without completing high-school education; A-levels, representing those with a high-school diploma or equivalent; and degree, representing those who graduate from university (3-year degree). The distribution of education in the population is shown at the bottom of Table 1 . The largest group is that with lower education attainment, and this is true for both men and women. Men in our age group and time window are more likely to have a degree than women, but, as we show, this does not hold in the more recent periods. Only about 12 per cent of our sample has a degree.

Wages are measured in hourly rates built as the ratio of the total gross weekly pay by total hours, both measures including paid and unpaid overtime. We remove aggregate wage growth from the wage rate and trim it at percentiles 2 and 99 from below and above, respectively, to limit the impact of measurement error in wages and hours. All results in monetary quantities are in 2016 prices.

The historical labour supply information is collected in waves 1992, 2001, 2002, 2009, and 2013. It exists for over 70 per cent of our sample. We use the history of employment and working hours to construct, for these years, two experience variables that measure accumulated experience time in part-time and full-time jobs since the beginning of the working life. We then complete the experience variables over the entire observation window using year-on-year information on employment spells and hours.

We complement the UKHLS with data from the British Labour Force Survey (LFS). It is used by the Office for National Statistics to produce official quarterly labour market statistics and has the advantage of being a much larger sample than the UKHLS. We use it for two purposes. First, to show some descriptive evidence of labour market trends. The LFS has a larger sample than the UKHLS, which enables us to characterize trends more accurately when the longitudinal feature of the data is not required. We find similar but more volatile patterns when reproducing the figures on UKHLS data. And second, to construct two measures of ‘women/family friendliness’ of jobs at the industry or occupation levels, that we then merge with the UKHLS data. Specifically, we merge in information on: the percentage of female employees by 3-digit occupation from the SOC classification; the percentage of employees doing part-time hours by occupation at the same level of disaggregation; and the percentage of female managers by 2-digit industry from the SIC classification.

(i)Differences in wages between men and women over time

We start by looking at the long-term trends in the gender wage gap in the UK. As for many other developed economies, gender wage disparities in the UK remain high despite a steady convergence over time since the 1980s. Figure 2 plots the average hourly wages of male and female employees over time according to the LFS. 3 It also plots, in black and on the right-hand axis, the proportional difference between the two. The gap has decreased over the last 20 years from almost 30 per cent in 1993. Currently, the average female employee earns around a fifth less per hour than the average male employee.

Trends in real hourly wages and the gender wage gap Notes : LFS 1993–2018. Real wage rates per hour in 2016 prices; observations in the top one and bottom two percentiles of the wage distribution by gender and year are excluded. Wage gap measured in proportion to male wages.

This wage gap is what it says on the tin: the difference between average female wages and average male wages. It is not a ‘like-for-like’ comparison between otherwise-identical workers or jobs. One reason why wage differentials between men and women might have changed over this period is that their relative levels of education have also changed. This is actually an important aspect to take into account in interpreting the declining wage gap over time.

Figure 3 shows a rapid increase in the level of education of the working population over the past 20 years. The take-up of education happened mostly at the top, with university graduation rates more than doubling over the period, while the proportion of individuals leaving school with minimal qualifications dropped strongly to compensate. The increase in education was faster for women, who overtook men by the late 2000s and are now more likely than men to have a university degree. Because graduates tend to earn more than non-graduates, these differential trends in educational attainment have contributed to reducing the gender wage gap.

Trends in education attainment, by gender Source : LFS 1993–2018.

Figure 4 shows the evolution of the gender wage gap as a proportion of male earnings over time, by education. For those with GCSE-level qualifications, this plot confirms that indeed the gender pay gap has fallen over the past two decades. However, it reveals no clear downward trend for the higher education groups. As a result, there has been a notable change in the nature of the gender wage gap. The gap used to be bigger (in proportional terms) for those with less formal qualifications than for university and high-school graduates, whereas the reverse is now the case. In summary, the fall in the overall gender wage gap over the past 20 years has been driven mostly by the lowest-educated individuals, and by an increase in the number of women who are highly educated.

Trends in the gender wage gap by education Notes : LFS 1993–2018. Wage gap measured in proportion to male wages.

(ii)Children, career patterns, and the gender wage gap over the life-cycle

A crucial starting point for disentangling the drivers of wage differences between men and women, which simple aggregate figures miss, is that those differences evolve over the life-cycle. This in turn is highly related to the arrival of children and changes in labour market behaviour associated with that. Figure 5 shows how average wages for male and female employees relate to their age (pooling those observed at the relevant ages between the start of 1993 and the middle of 2017). Notice that the sets of individuals who are employed at each age are different, so it is possible, for example, that women with low levels of experience return to employment in their 40s, thereby dragging down average female wages at that age. Wages are shown in 2016 constant-wage terms, so the increasing profile with age means that wages increase over the course of life by more than would be expected simply due to economy-wide growth.

Mean hourly wages across the life-cycle by gender and education Notes : LFS 1993 to 2018. Wage rates per hour in constant 2016 wage levels; observations in the top one and bottom two percentiles of the wage distribution by gender and year are excluded.