- Make a Gift

- Directories

Search form

You are here.

- Programs & Courses

- Undergraduate

- Undergraduate Research

What is Humanities Research?

Research in the humanities is frequently misunderstood. When we think of research, what immediately comes to mind for many of us is a laboratory setting, with white-coated scientists hunched over microscopes. Because research in the humanities is often a rather solitary activity, it can be difficult for newcomers to gain a sense of what research looks like within the scope of English Studies. (For examples, see Student Research Profiles .)

A common misconception about research is reinforced when we view it solely in terms of the discovery of things previously unknown (such as a new species or an archaelogical artifact) rather than as a process that includes the reinterpretation or rediscovery of known artifacts (such as texts and other cultural products) from a critical or creative perspective to generate innovative art or new analyses. Fundamental to the concept of research is precisely this creation of something new. In the humanities, this might consist of literary authorship, which creates new knowledge in the form of art, or scholarly research, which adds new knowledge by examining texts and other cultural artifacts in the pursuit of particular lines of scholarly inquiry.

Research is often narrowly construed as an activity that will eventually result in a tangible product aimed at solving a world or social problem. Instead, research has many aims and outcomes and is a discipline-specific process, based upon the methods, conventions, and critical frameworks inherent in particular academic areas. In the humanities, the products of research are predominantly intellectual and intangible, with the results contributing to an academic discipline and also informing other disciplines, a process which often effects individual or social change over time.

The University of Washington Undergraduate Research Program provides this basic definition of research:

"Very generally speaking, most research is characterized by the evidence-based exploration of a question or hypothesis that is important to those in the discipline in which the work is being done. Students, then, must know something about the research methodology of a discipline (what constitutes "evidence" and how do you obtain it) and how to decide if a question or line of inquiry that is interesting to that student is also important to the discipline, to be able to embark on a research project."

While individual research remains the most prevalent form in the humanities, collaborative and cross-disciplinary research does occur. One example is the "Modern Girl Around the World" project, in which a group of six primary UW researchers from various humanities and social sciences disciplines explored the international emergence of the figure of the Modern Girl in the early 20th century. Examples of other research clusters are "The Race/Knowledge Project: Anti-Racist Praxis in the Global University," "The Asian American Studies Research Cluster," " The Queer + Public + Performance Project ," " The Moving Images Research Group ," to name a few.

English Studies comprises, or contains elements of, many subdisciplines. A few examples of areas in which our faculty and students engage are Textual Studies , Digital Humanities , American Studies , Language and Rhetoric , Cultural Studies , Critical Theory , and Medieval Studies . Each UW English professor engages in research in one or more specialty areas. You can read about English faculty specializations, research, and publications in the English Department Profiles to gain a sense of the breadth of current work being performed by Department researchers.

Undergraduates embarking on an independent research project work under the mentorship of one or more faculty members. Quite often this occurs when an advanced student completes an upper-division class and becomes fascinated by a particular, more specific line of inquiry, leading to additional investigation in an area beyond the classroom. This also occurs when students complete the English Honors Program , which culminates in a guided research-based thesis. In order for faculty members to agree to mentor a student, the project proposal must introduce specific approaches and lines of inquiry, and must be deemed sufficiently well defined and original enough to contribute to the discipline. If a faculty member in English has agreed to support your project proposal and serve as your mentor, credit is available through ENGL 499.

Beyond English Department resources, another source of information is the UW Undergraduate Research Program , which sponsors the annual Undergraduate Research Symposium . They also offer a one-credit course called Research Exposed (GEN ST 391) , in which a variety of faculty speakers discuss their research and provide information about research methods. Another great campus resource is the Simpson Center for the Humanities which supports interdisciplinary study. A number of our students have also been awarded Mary Gates Research Scholarships .

Each year, undergraduate English majors participate in the UW's Annual Undergraduate Research Symposium as well as other symposia around the nation. Here are some research abstracts from the symposia proceedings archive by recent English-major participants.

UW English Majors Recently Presenting at the UW's Annual Undergraduate Research Symposium

For additional examples, see Student Profiles and Past Honors Students' Thesis Projects .

- Newsletter

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Humanities Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Humanities Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Humanities Research

Definition:

Humanities research is a systematic and critical investigation of human culture, values, beliefs, and practices, including the study of literature, philosophy, history, art, languages, religion, and other aspects of human experience.

Types of Humanities Research

Types of Humanities Research are as follows:

Historical Research

This type of research involves studying the past to understand how societies and cultures have evolved over time. Historical research may involve examining primary sources such as documents, artifacts, and other cultural products, as well as secondary sources such as scholarly articles and books.

Cultural Studies

This type of research involves examining the cultural expressions and practices of a particular society or community. Cultural studies may involve analyzing literature, art, music, film, and other forms of cultural production to understand their social and cultural significance.

Linguistics Research

This type of research involves studying language and its role in shaping cultural and social practices. Linguistics research may involve analyzing the structure and use of language, as well as its historical development and cultural variations.

Anthropological Research

This type of research involves studying human cultures and societies from a comparative and cross-cultural perspective. Anthropological research may involve ethnographic fieldwork, participant observation, interviews, and other qualitative research methods.

Philosophy Research

This type of research involves examining fundamental questions about the nature of reality, knowledge, morality, and other philosophical concepts. Philosophy research may involve analyzing philosophical texts, conducting thought experiments, and engaging in philosophical discourse.

Art History Research

This type of research involves studying the history and significance of art and visual culture. Art history research may involve analyzing the formal and aesthetic qualities of art, as well as its historical context and cultural significance.

Literary Studies Research

This type of research involves analyzing literature and other forms of written expression. Literary studies research may involve examining the formal and structural qualities of literature, as well as its historical and cultural context.

Digital Humanities Research

This type of research involves using digital technologies to study and analyze cultural artifacts and practices. Digital humanities research may involve analyzing large datasets, creating digital archives, and using computational methods to study cultural phenomena.

Data Collection Methods

Data Collection Methods in Humanities Research are as follows:

- Interviews : This method involves conducting face-to-face, phone or virtual interviews with individuals who are knowledgeable about the research topic. Interviews may be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured, depending on the research questions and objectives. Interviews are often used in qualitative research to gain in-depth insights and perspectives.

- Surveys : This method involves distributing questionnaires or surveys to a sample of individuals or groups. Surveys may be conducted in person, through the mail, or online. Surveys are often used in quantitative research to collect data on attitudes, behaviors, and other characteristics of a population.

- Observations : This method involves observing and recording behavior or events in a natural or controlled setting. Observations may be structured or unstructured, and may involve the use of audio or video recording equipment. Observations are often used in qualitative research to collect data on social practices and behaviors.

- Archival Research: This method involves collecting data from historical documents, artifacts, and other cultural products. Archival research may involve accessing physical archives or online databases. Archival research is often used in historical and cultural studies to study the past.

- Case Studies : This method involves examining a single case or a small number of cases in depth. Case studies may involve collecting data through interviews, observations, and archival research. Case studies are often used in cultural studies, anthropology, and sociology to understand specific social or cultural phenomena.

- Focus Groups : This method involves bringing together a small group of individuals to discuss a particular topic or issue. Focus groups may be conducted in person or online, and are often used in qualitative research to gain insights into social and cultural practices and attitudes.

- Participatory Action Research : This method involves engaging with individuals or communities in the research process, with the goal of promoting social change or addressing a specific social problem. Participatory action research may involve conducting focus groups, interviews, or surveys, as well as involving participants in data analysis and interpretation.

Data Analysis Methods

Some common data analysis methods used in humanities research:

- Content Analysis : This method involves analyzing the content of texts or cultural artifacts to identify patterns, themes, and meanings. Content analysis is often used in literary studies, media studies, and cultural studies to analyze the meanings and representations conveyed in cultural products.

- Discourse Analysis: This method involves analyzing the use of language and discourse to understand social and cultural practices and identities. Discourse analysis may involve analyzing the structure, meaning, and power dynamics of language and discourse in different social contexts.

- Narrative Analysis: This method involves analyzing the structure, content, and meaning of narratives in different cultural contexts. Narrative analysis may involve analyzing the themes, symbols, and narrative devices used in literary texts or other cultural products.

- Ethnographic Analysis : This method involves analyzing ethnographic data collected through participant observation, interviews, and other qualitative methods. Ethnographic analysis may involve identifying patterns and themes in the data, as well as interpreting the meaning and significance of social and cultural practices.

- Statistical Analysis: This method involves using statistical methods to analyze quantitative data collected through surveys or other quantitative methods. Statistical analysis may involve using descriptive statistics to describe the characteristics of the data, or inferential statistics to test hypotheses and make inferences about a population.

- Network Analysis: This method involves analyzing the structure and dynamics of social networks to understand social and cultural practices and relationships. Network analysis may involve analyzing patterns of social interaction, communication, and influence.

- Visual Analysis : This method involves analyzing visual data, such as images, photographs, and art, to understand their cultural and social significance. Visual analysis may involve analyzing the formal and aesthetic qualities of visual products, as well as their historical and cultural context.

Examples of Humanities Research

Some Examples of Humanities Research are as follows:

- Literary research on diversity and representation: Scholars of literature are exploring the representation of different groups in literature and how those representations have changed over time. They are also studying how literature can promote empathy and understanding across different cultures and communities.

- Philosophical research on ethics and technology: Philosophers are examining the ethical implications of emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence and biotechnology. They are asking questions about what it means to be human in a world where technology is becoming increasingly advanced.

- Anthropological research on cultural identity: Anthropologists are studying the ways in which culture shapes individual and collective identities. They are exploring how cultural practices and beliefs can shape social and political systems, as well as how individuals and communities resist or adapt to dominant cultural norms.

- Linguistic research on language and communication: Linguists are studying the ways in which language use and communication can impact social and political power dynamics. They are exploring how language can reinforce or challenge social hierarchies and how language use can reflect cultural values and norms.

How to Conduct Humanities Research

Conducting humanities research involves a number of steps, including:

- Define your research question or topic : Identify a question or topic that you want to explore in-depth. This can be a broad or narrow topic, depending on the scope of your research project.

- Conduct a literature review: Before beginning your research, read extensively on your topic. This will help you understand the existing scholarship and identify gaps in the literature that your research can address.

- Develop a research methodology: Determine the methods you will use to collect and analyze data, such as interviews, surveys, archival research, or textual analysis. Your methodology should be appropriate to your research question and topic.

- Collect data: Collect data using the methods you have chosen. This may involve conducting interviews, surveys, or archival research, or analyzing primary or secondary sources.

- Analyze data: Once you have collected data, analyze it using appropriate methods. This may involve coding, categorizing, or comparing data, or interpreting texts or other sources.

- Draw conclusions: Based on your analysis, draw conclusions about your research question or topic. These conclusions should be supported by your data and should contribute to existing scholarship.

- Communicate your findings : Communicate your findings through writing, presentations, or other forms of dissemination. Your work should be clearly written and accessible to a broad audience.

Applications of Humanities Research

Humanities research has many practical applications in various fields, including:

- Policy-making: Humanities research can inform policy-making by providing insights into social, cultural, and historical contexts. It can help policymakers understand the impact of policies on communities and identify potential unintended consequences.

- Education: Humanities research can inform curriculum development and pedagogy. It can provide insights into how to teach critical thinking, cross-cultural understanding, and communication skills.

- Cultural heritage preservation: Humanities research can help to preserve cultural heritage by documenting and analyzing cultural practices, traditions, and artifacts. It can also help to promote cultural tourism and support local economies.

- Business and industry: Humanities research can provide insights into consumer behavior, cultural preferences, and historical trends that can inform marketing, branding, and product design.

- Healthcare : Humanities research can contribute to the development of patient-centered healthcare by exploring the impact of social and cultural factors on health and illness. It can also help to promote cross-cultural understanding and empathy in healthcare settings.

- Social justice: Humanities research can contribute to social justice by providing insights into the experiences of marginalized communities, documenting historical injustices, and promoting cross-cultural understanding.

Purpose of Humanities Research

The purpose of humanities research is to deepen our understanding of human experience, culture, and history. Humanities research aims to explore the human condition and to provide insights into the diversity of human perspectives, values, and beliefs.

Humanities research can contribute to knowledge in various fields, including history, literature, philosophy, anthropology, and more. It can help us to understand how societies and cultures have evolved over time, how they have been shaped by various factors, and how they continue to change.

Humanities research also aims to promote critical thinking and creativity. It encourages us to question assumptions, to challenge dominant narratives, and to seek out new perspectives. Humanities research can help us to develop empathy and understanding for different cultures and communities, and to appreciate the richness and complexity of human experience.

Overall, the purpose of humanities research is to contribute to a deeper understanding of ourselves, our communities, and our world. It helps us to grapple with fundamental questions about the human experience and to develop the skills and insights needed to address the challenges of the future.

When to use Humanities Research

Humanities research can be used in various contexts where a deeper understanding of human experience, culture, and history is required. Here are some examples of when humanities research may be appropriate:

- Exploring social and cultural phenomena: Humanities research can be used to explore social and cultural phenomena such as art, literature, religion, and politics. It can help to understand how these phenomena have evolved over time and how they relate to broader social, cultural, and historical contexts.

- Understanding historical events: Humanities research can be used to understand historical events such as wars, revolutions, and social movements. It can provide insights into the motivations, experiences, and perspectives of the people involved, and help to contextualize these events within broader historical trends.

- Promoting cultural understanding : Humanities research can be used to promote cross-cultural understanding and to challenge stereotypes and biases. It can provide insights into the diversity of human experiences, values, and beliefs, and help to build empathy and mutual respect across different cultures and communities.

- Informing policy-making: Humanities research can be used to inform policy-making by providing insights into social, cultural, and historical contexts. It can help policymakers understand the impact of policies on communities and identify potential unintended consequences.

- Promoting innovation and creativity : Humanities research can be used to promote innovation and creativity in various fields. It can help to generate new ideas, perspectives, and approaches to complex problems, and to challenge conventional thinking and assumptions.

Characteristics of Humanities Research

Some of the key characteristics of humanities research:

- Focus on human experience: Humanities research focuses on the study of human experience, culture, and history. It aims to understand the human condition, explore human values and beliefs, and analyze the ways in which societies and cultures have evolved over time.

- Interpretive approach: Humanities research takes an interpretive approach to data analysis. It seeks to understand the meaning behind texts, artifacts, and cultural practices, and to explore the multiple perspectives and contexts that shape human experience.

- Contextualization : Humanities research emphasizes the importance of contextualization. It seeks to understand how social, cultural, and historical factors shape human experience, and to place individual phenomena within broader cultural and historical contexts.

- Subjectivity : Humanities research recognizes the subjective nature of human experience. It acknowledges that human values, beliefs, and experiences are shaped by individual perspectives, and that these perspectives can vary across cultures, communities, and time periods.

- Narrative analysis : Humanities research often uses narrative analysis to explore the stories, myths, and cultural narratives that shape human experience. It seeks to understand how these narratives are constructed, how they evolve over time, and how they influence individual and collective identity.

- Multi-disciplinary: Humanities research is often interdisciplinary, drawing on a range of disciplines such as history, literature, philosophy, anthropology, and more. It seeks to bring together different perspectives and approaches to understand complex human phenomena.

Advantages of Humanities Research

Some of the key advantages of humanities research:

- Promotes critical thinking: Humanities research encourages critical thinking by challenging assumptions and exploring different perspectives. It requires researchers to analyze and interpret complex texts, artifacts, and cultural practices, and to make connections between different phenomena.

- Enhances cultural understanding : Humanities research promotes cross-cultural understanding by exploring the diversity of human experiences, values, and beliefs. It helps to challenge stereotypes and biases and to build empathy and mutual respect across different cultures and communities.

- Builds historical awareness: Humanities research helps us to understand the historical context of current events and social issues. It provides insights into how societies and cultures have evolved over time and how they have been shaped by various factors, and helps us to contextualize current social, political, and cultural trends.

- Contributes to public discourse: Humanities research contributes to public discourse by providing insights into complex social, cultural, and historical phenomena. It helps to inform public policy and public debate by providing evidence-based analysis and insights into social issues and problems.

- Promotes creativity and innovation: Humanities research promotes creativity and innovation by challenging conventional thinking and assumptions. It encourages researchers to generate new ideas and perspectives and to explore alternative ways of understanding and addressing complex problems.

- Builds communication skills: Humanities research requires strong communication skills, including the ability to analyze and interpret complex texts, artifacts, and cultural practices, and to communicate findings and insights in a clear and compelling way.

Limitations of Humanities Research

Some of the key limitations of humanities research:

- Subjectivity: Humanities research relies heavily on interpretation and analysis, which are inherently subjective. Researchers bring their own perspectives, biases, and values to the analysis, which can affect the conclusions they draw.

- Lack of generalizability : Humanities research often focuses on specific texts, artifacts, or cultural practices, which can limit the generalizability of findings to other contexts. It is difficult to make broad generalizations based on limited samples, which can be a challenge when trying to draw broader conclusions.

- Limited quantitative data : Humanities research often relies on qualitative data, such as texts, images, and cultural practices, which can be difficult to quantify. This can make it difficult to conduct statistical analyses or to draw quantitative conclusions.

- Limited replicability: Humanities research often involves in-depth analysis of specific texts, artifacts, or cultural practices, which can make it difficult to replicate studies. This can make it challenging to test the validity of findings or to compare results across studies.

- Limited funding: Humanities research may not always receive the same level of funding as other types of research. This can make it challenging for researchers to conduct large-scale studies or to have access to the same resources as other researchers in different fields.

- Limited impact : Humanities research may not always have the same level of impact as research in other fields, particularly in terms of policy and practical applications. This can make it challenging for researchers to demonstrate the relevance and impact of their work.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Documentary Research – Types, Methods and...

Scientific Research – Types, Purpose and Guide

Original Research – Definition, Examples, Guide

Historical Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Artistic Research – Methods, Types and Examples

What’s the Value of Humanities Research?

What’s the Value of Humanities Research? Panel Presentations and Open Discussion

Monday, September 8, 2014 3:00 P.M. – 5:00 P.M. Banquet Room, University Club Building

W e in the humanities face widespread clamor for STEM fields, public demand for measurable and monetary value for research and majors, and rapidly changing landscapes of knowledge in the unfolding Digital Revolution and globalized Information Age. With the humanities “in crisis”—yet again—many are effectively defending the importance of the humanities for a college education.

But what about research in the humanities? Does it matter ? How and why?

- What’s the value of research in the humanities in the 21st century? What’s its use or usefulness? How do we define value in reference to our work?

- What’s the matter of humanities research? Is our task preservation or creation? Interpretation or discovery? Critical analysis or recovery? Innovations or replications? Instrumentalist solutions to problems or joyful expansions of knowledge?

- Should our research engage more substantially with the issues facing the world today? Is it sufficient to pursue knowledge as an end in itself?

- Do the “pure humanities” parallel “pure science” in as-yet-undetermined future value?

- Can we justify the humanities’ conventional focus on human meaning-making in a “posthuman” age of massive climate change, the declining diversity of species, the rise of robots, cyborgs, and chimeras?

- Can or should humanities research become more collaborative? What forms of collaboration beyond the model of lab science might work in the humanities? Is there still a role for individual research?

- Who do we do humanities research for? And to what purpose? A small circle of specialists? A wide range of fields? Our students? The “public”? Ourselves?

- What’s the value of humanities research for a liberal arts education? For students? For the “public”? For individuals? For familial, communal, and global relations?

- How do we affirm and communicate humanities research in the face of constant pressure to justify the value and usefulness of what we do?

Panel Presentations followed by open discussion. Come with your ideas!

Biographies of Panelists

Guillermina De Ferrari is Professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature and the Director of the Center for Visual Cultures. Her research focuses on contemporary Caribbean narrative and art. Her first book Vulnerable States: Bodies of Memory in Contemporary Caribbean Fiction (2007) studies the metaphorical power of the vulnerable body in Caribbean narrative from the perspective of postcolonial theory. Her second book Community and Culture in Post-Soviet Cuba (2014), which analyzes contemporary literature and art produced in Cuba since 1991, attributes the extraordinary survival of the Cuban Revolution to a social contract based on deeply ingrained notions of gender, community, and ethics. She is currently curating an exhibit called Apertura: Photography in Cuba Today to be held at the Chazen Museum in spring 2015.

Sara Guyer is Professor of English and Director of the Center for the Humanities. She also teaches in the Center for Jewish Studies and the Department of Comparative Literature and Folklore Studies, and has designed a new graduate certificate in public humanities that will launch this spring. Her research focuses on romanticism and its legacies, on biopolitics and critical theory, and more recently on institutional questions of the humanities. She is the author of Romanticism after Auschwitz (2007) and the forthcoming Reading with John Clare: Biopoetics, Sovereignty, Romanticism (2015). She is currently at work on a collection of essays on “strategic anthropomorphism” and a special issue of South Atlantic Quarterly on biopolitics. She edits the new book series at Fordham, Lit Z and serves on the International Advisory Committee of the Consortium of Humanities Centers and Institutes.

Caroline Levine is Professor and Chair of the English Department. She specializes in Victorian literature, world literature, and literary and cultural theory. Particularly interested in relations between art and politics, she is the author of three books that address this question from different perspectives: The Serious Pleasures of Suspense: Victorian Realism and Narrative Doubt (2003); Provoking Democracy: Why We Need the Arts (2007); and Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network (forthcoming, 2015). She is also the nineteenth-century editor of the Norton Anthology of World Literature and co-convener of the World Literatures Research Group and Sawyer Seminar (2015-17).

David Loewenstein is the Helen C. White Professor of English and the Humanities; he is an affiliate of the UW Religious Studies Program. His research has focused on literature in relation to politics and religion in early modern England. Noted Milton scholar and author of many books, he has most recently published Treacherous Faith: The Specter of Heresy in Early Modern English Literature and Culture (2013), a book that studies the culture of religious fear-mongering and the construction of heretics and heresies in early modern England from Thomas More to John Milton; much of the research for this book was done while he was a Senior Fellow at the IRH.

Daegan Miller is a Mellon Post-doctoral Fellow and a cultural and environmental historian of the 19th-century American landscape. His work focuses on how nineteenth-century Americans conceived of alternative, countermodern landscapes, ones that contest the legacy of Manifest Destiny, scientific racism, and the cultural hegemony of capitalism. Besides cultural and environmental history, he draws on eco-criticism, visual culture, cultural landscape studies, the history of science and technology, the various spatial turns in the humanities, and radical politics. He has published work in Rethinking History , Environmental Humanities , the creative writing journal Stone Canoe , and currently has pieces working their way through Raritan and The American Historical Review . He is completing a book manuscript, Witness Tree: Essays on Landscape and Dissent from the 19th-Century United States.

Lynn Nyhart is Vilas-Bablitch-Kelch Distinguished Achievement Professor of the History of Science, with affiliations in the Holtz Center for Science and Technology Studies, the Center for German and European Studies, and Gender and Women’s Studies. Nyhart’s main research interests lie in the history of European and American biology in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and the relations between popular and professional science. With Scott Lidgard at the Field Museum (Chicago), she is currently working on a history of concepts of biological part-whole relations and individuality in the nineteenth century. She is the author of Modern Nature: The Rise of the Biological Perspective in Germany (2009), and Biology Takes Form: Animal Morphology and the German Universities, 1800-1900 (1996). She is immediate past president of the History of Science Society.

References for the Curious

Sources addressing the “crisis in the humanities” and what we should do about it abound. For the curious, the Institute is making available the following resources located in Room 201 (the Copy Room) for reading in the building.

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences. The Heart of the Matter: The Humanities and Social Sciences . Report Brief. Summary of Report submitted to Congress. June 2013.

- Peter Brooks, ed. The Humanities and Public Life . Essays by Appiah, Butler, and many others. New York: Fordham UP, 2014.

- Helen Small. The Value of the Humanities . Oxford: Oxford UP, 2013.

Stanford Humanities Today

Arcade: a digital salon.

Why Do the Humanities Matter?

Discovering Humanities Research at Stanford

Stanford Humanities Center

Advancing Research in the Humanities

Humanities Research for a Digital Future

The Humanities in the World

- Annual Reports

- Humanitrees

- Humanities Center Fellows

- Advisory Council

- Director's Alumni Cabinet

- Honorary Fellows

- Hume Honors Fellows

- International Visitors

- Workshop Coordinators

- Why Humanities Matter

- Fellowships for External Faculty

- Fellowships for Stanford Faculty

- Mellon Fellowship of Scholars in the Humanities

- Dissertation Fellowships FAQs

- Career Launch Fellowships

- Fellowships for Stanford Undergraduates

- International Visitors Program

- FAQ Mellon Fellowship

- Faculty Fellowships FAQ

- Events Archive

- Public Lectures

- Checklist for Event Coordinators

- Facilities Guidelines

- co-sponsorship from the Stanford Humanities Center

- Call for Proposals

- Manuscript Workshops

- Past Workshops

- Research Workshops

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

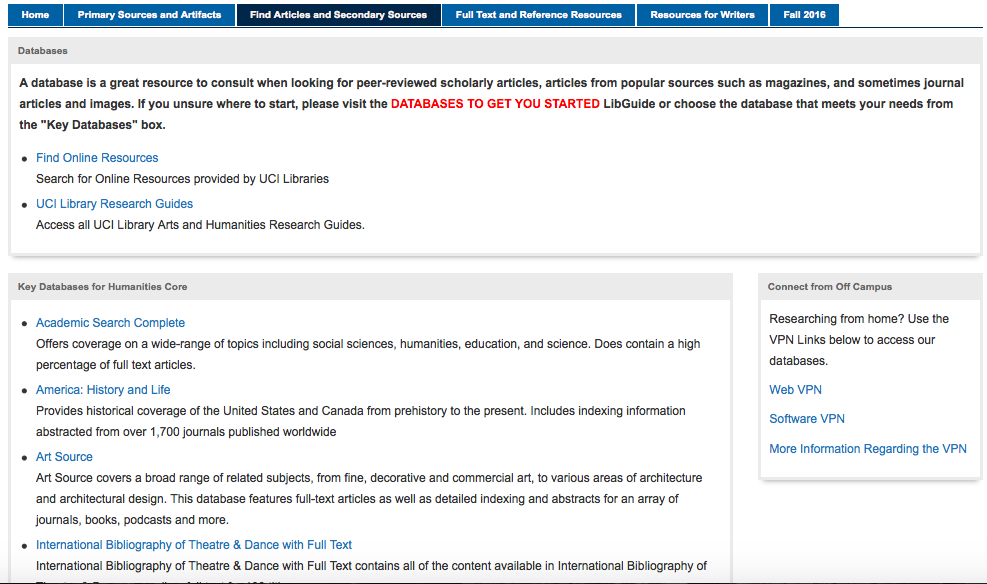

UCI Humanities Core

Research in the Humanities

By Matt Roberts Revised for 2018-19

Introduction

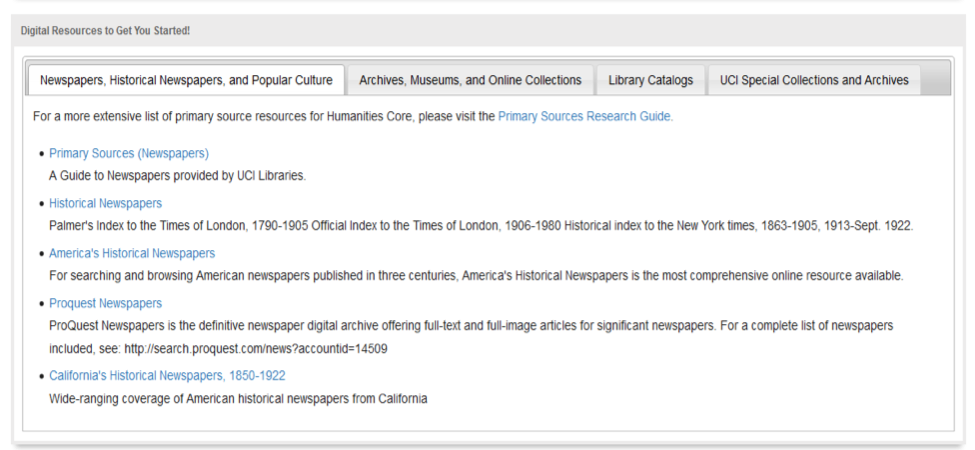

Welcome to the University of California, Irvine! As a student enrolled in the Humanities Core program, you will study a variety of cultural artifacts related to the theme of “Empire and Its Ruins.” Research will be important to your engagement with course material and topics, and the UCI Libraries is here to help you.

The UCI Libraries is home to several research librarians, who can provide you with expert service. To learn more, please visit the UCI Libraries’ Directory of Research Librarians .

To take advantage of the UCI Libraries’ resources for Humanities Core, please visit the Humanities Core Research Guide . You find the guide by visiting the UCI Libraries’ home page. Then click on the “ Research Guides ” Quick Link.

What is Humanities Research?

It is worth asking what it means to do research in the Humanities. As David Pan (Professor of German, UCI School of Humanities) writes, “[i]nterpretation is the primary method of the humanities because the meaning that humanities scholars search for is not a constant one. Rather, standards of meaning change when one moves in time and space from one cultural context to another. Negotiating this movement is the primary task in humanities inquiry” (6) .

As Pan emphasizes, humanities work is an interpretive process. For instance, for your first major writing assignment, you must perform a close reading of a passage from the Aeneid . You will describe how the selection’s formal elements—such as symbolism or diction—support an overarching theme in the epic as a whole. While this assignment does not require that you conduct research related to the Aeneid , it nevertheless invites you to research the meaning of “symbolism” or “diction.” Let us therefore assess our information need and design a process to find the definition of, for example, diction.

Question: Where do we find the definition of a word or specialized term such as “diction”?

Answer: We find definitions in a dictionary.

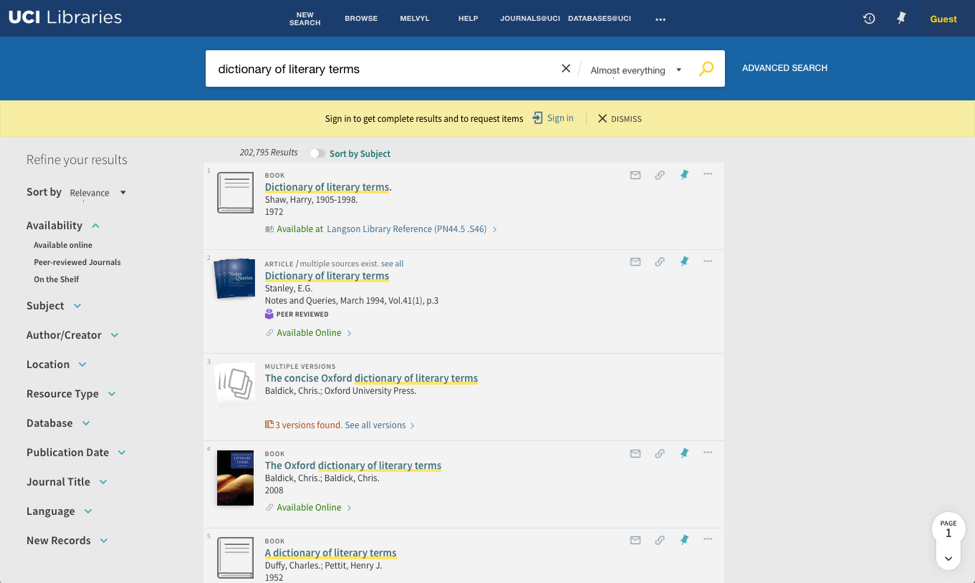

Note that as the Aeneid is an epic poem, it is important to determine what “diction” means within a literary context. Therefore, let’s consult a dictionary of literary terms.

Question : How do we find a dictionary of literary terms?

Answer: Consult the UCI Libraries’ webpage . Then search Library Search , the new finding aid for the UCI Libraries’ catalog. Since we don’t know the exact title of the dictionary that we might use, we can simply search for “dictionary of literary terms.”

We must choose the title that best matches our information need. I chose The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms because Oxford University Press publishes exemplary reference materials. The green “Available Online” link takes me directly to this resource. I can then use the resource to search for the definition of “Diction.”

So, what have we learned?

- Research begins with a question (“What is diction?”).

- The research question(s) that we ask helps us to discover information.

- The kind of information that we need to discover will often determine what UCI Libraries’ resource to consult (e.g., a book, reference resource, database, etc.).

- Discovering information helps us to interpret an object of study.

- The interpretation of the object of study enables us to craft clearly argued responses to writing assignments.

In other words, humanities research is a strategic exploration whereby information discovery facilitates your interpretive abilities.

Doing Research: Primary Sources and Secondary Sources

As we have already noticed, the research process involves the ability to discover a source that provides information of some kind. It is therefore important to distinguish between sources so that you can readily access that information.

Scholars typically distinguish between kinds of sources, particularly between primary and secondary sources. As you will be reading a variety of texts this year, it is important to recognize that texts are not objectively primary or secondary. Ultimately, the extent to which sources are primary depends upon the questions you ask about them and the way that you use them (Arndt 93). For instance, a primary source is an object that bears witness to a historical event. Primary sources therefore call us to consider how they make meaning of the event to which they bear witness. On the other hand, secondary sources interpret a primary source. For example, if you were to write a paper that interprets how diction in the Aeneid characterizes human experience, you would be creating a secondary source.

Determining the difference between a primary source and a secondary source can be difficult. Let us explore each type of source in greater detail so that we can begin to understand what types of question we can ask of primary sources, and how we can engage with them in order to research secondary source material.

Primary Sources

On your syllabus, you will find a variety of texts, or sources, that you will read over the course of the year. In the fall quarter, these texts include, but are not limited to:

- Virgil’s Aeneid (19 B.C.E.)

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality among Men” (1754/1755)

- J.M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians (1980)

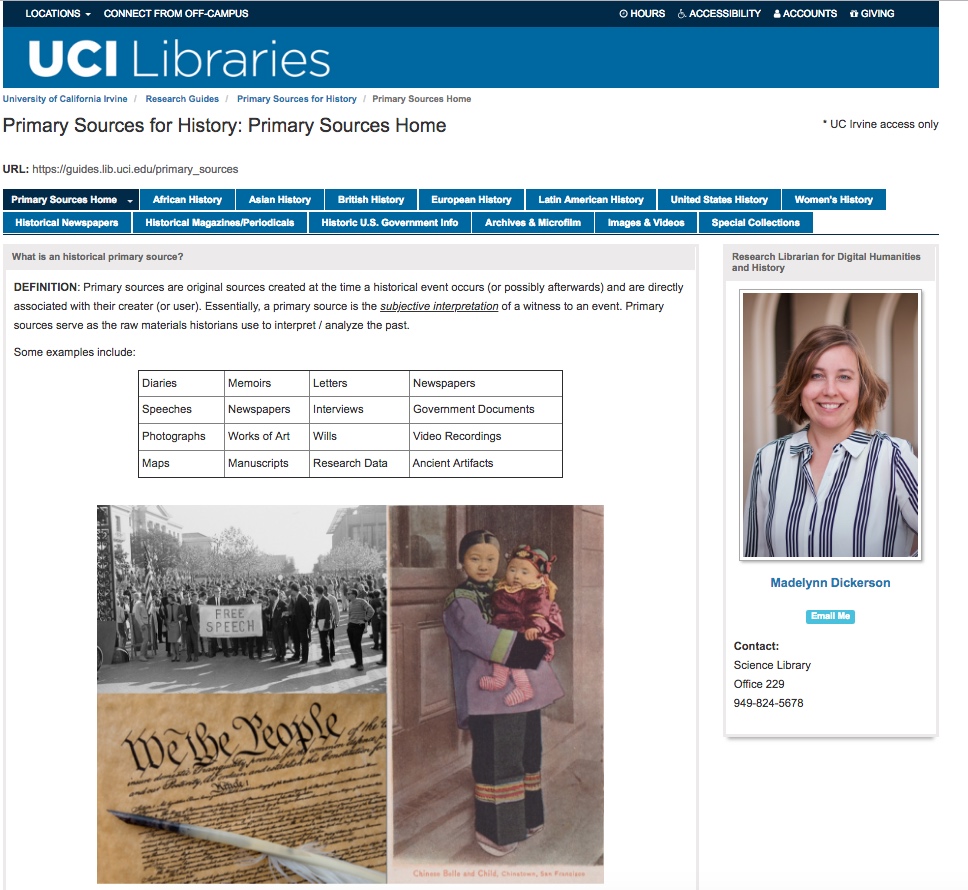

These are generally considered to be primary sources, but how can you be sure? To answer this question, consult the Primary Sources Research Guide , curated by the UCI Libraries’ History Librarian, Madelynn Dickerson.

According to this Research Guide, primary sources can include diaries, memoirs, letters, newspapers, speeches, interviews, government documents, photographs, works of art, video recordings, maps, manuscripts, data, and physical artifacts.

Question: Is the Aeneid a primary source?

Answer: Yes. Most often it qualifies because it is a work of art, specifically an epic poem. However, one might use the Fagles’ version of The Aeneid as a secondary source, demonstrating how the translation is an interpretation of the original Latin text and using that analysis to offer one’s own interpretation of the epic poem. You can learn more about the interpretive politics of translation from Giovanna Fogli and Nuccia Malinverni’s chapter on “Translation” in your Writer’s Handbook .

Throughout the year, you will be encouraged to find primary sources related to the topic of Empire and Its Ruins. To do this, it is useful to visit the Humanities Core Research Guide . Select the “ Primary Sources and Artifacts” tab to locate primary source discovery resources.

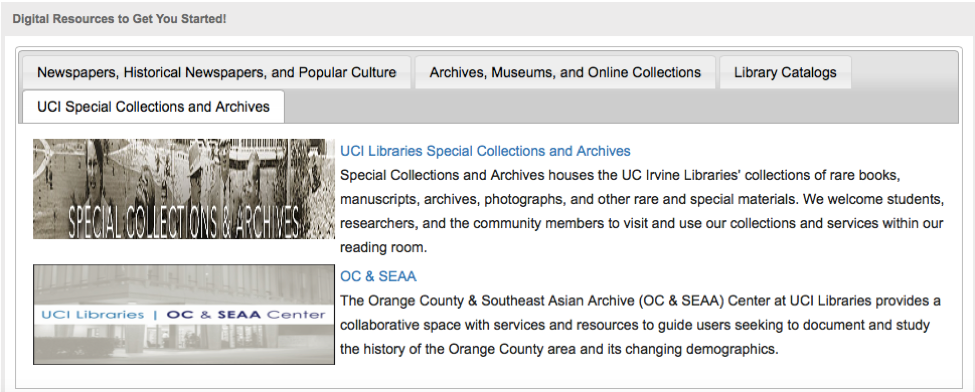

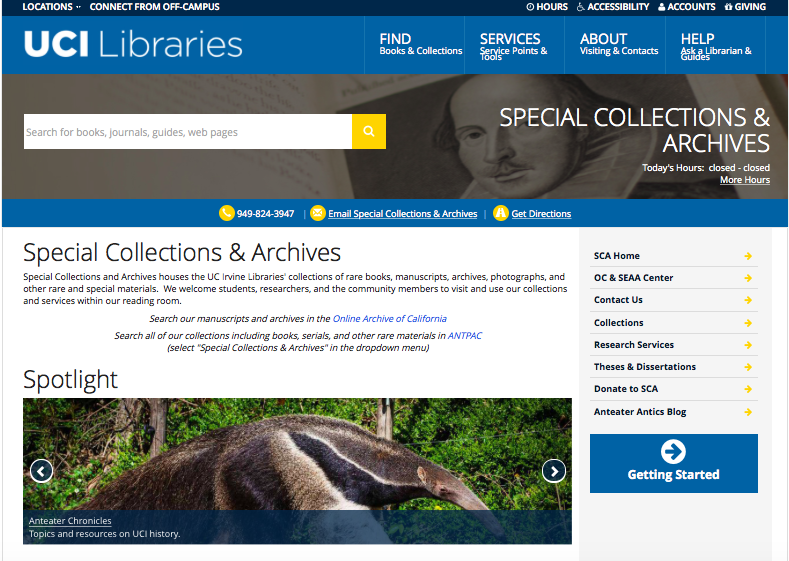

Additionally, you will have the unique opportunity to visit the Special Collections and Archives .

Follow the link to the SCA webpage, and you can discover a variety of primary source collections. Be sure to also visit the UCI Libraries’ Southeast Asian Archive webpage for a wealth of primary sources related to Empire and Its Ruins.

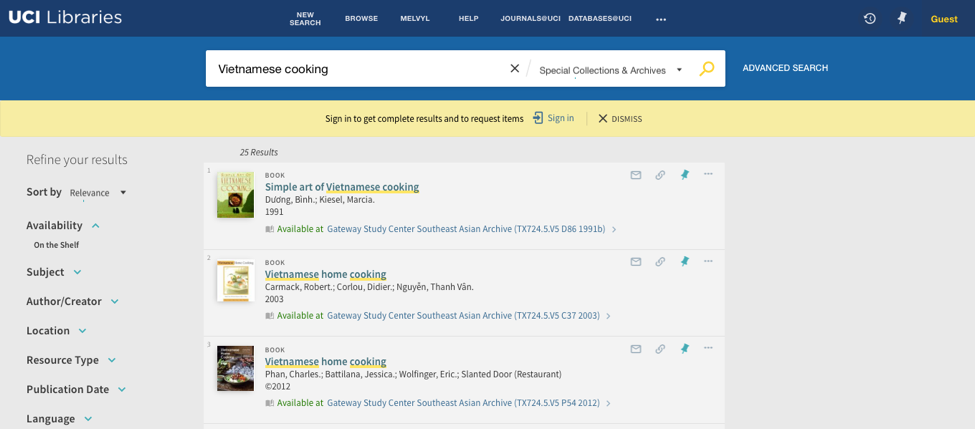

You can also use Library Finder to find primary sources and cultural artifacts in the SCA collection.

When analyzing a primary source, it is important to ask certain questions. Questions such as those listed below will help you to discover information, which you can use to interpret a primary source. In other words, questions such as these will help you to determine how a primary source makes meaning of the event to which they bear witness.

- Who made the primary source? What was that person’s race, gender, class? How, if at all, would that matter within the historical period in which the source is created? (Authorship)

- Where, when, and why was the primary source written/made? Does it describe specific attitudes of a historical period and place? What motivated its production? (Historical Context)

- For whom was the primary source written/made? For public or private use? Was it reproduced for a mass audience? How might that audience have used or responded to this source? (Audience)

- Of what is the primary source made? How might that shape how the source is understood and interpreted? (Materiality)

- What are the limitations of this type of source? What can’t it tell us? For whom is it not made available?

Simple questions such as these can help you to formulate more sophisticated research questions or topics of inquiry. You may therefore want to examine other primary sources or search for how expert scholars interpret the primary source that interests you.

Secondary Sources

When you do research, you are embarking on a journey that requires you to engage with how others interpret the primary source or sources that interest you. Whereas primary sources are original works that document an event as it took place, a secondary source interprets a primary source, often long after it was created. Secondary sources include, but are not limited to: Peer-reviewed academic books; chapters published in peer-reviewed academic books; peer-reviewed journal articles; newspaper and magazine articles published after, and therefore not explicitly covering, a historical event. Peer-reviewed works are considered to be most reliable in academic settings because they have been scrutinized and vetted by scholars to determine if the research presented makes a significant contribution.

Question : How do we find peer-reviewed journal articles?

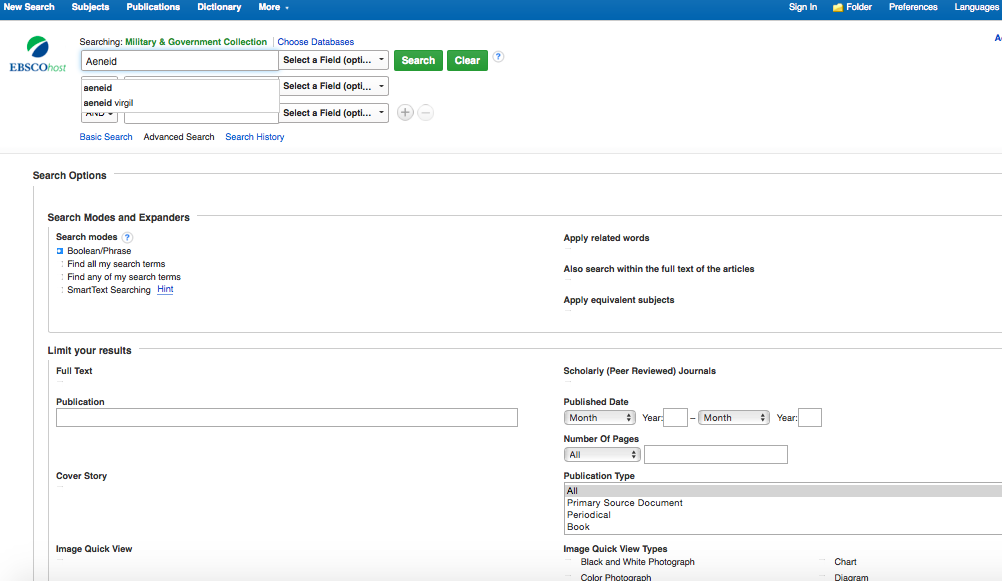

Answer: Let’s return to the Humanities Core Research Guide, where we will find links to, and descriptions of, the databases related to Humanities Core. Select the “ Find Articles and Secondary Sources” tab to find peer-review journal articles.

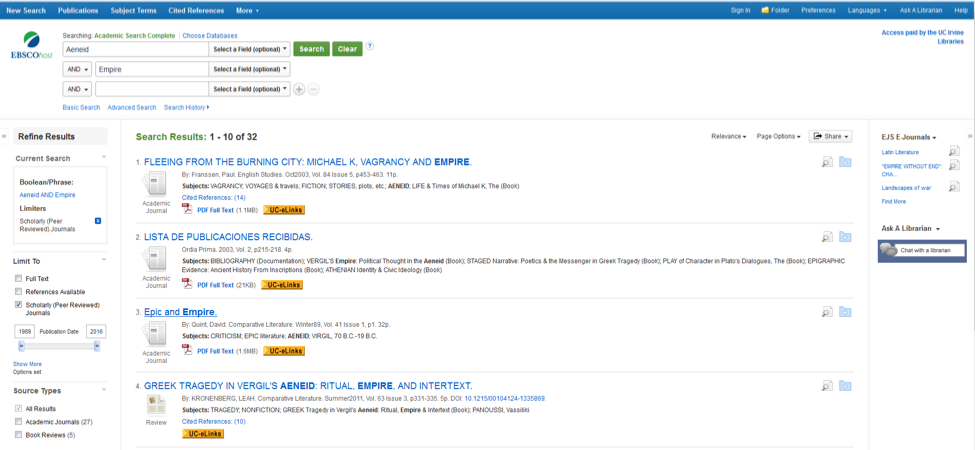

I began my search with Academic Search Complete , which covers a wide-range of topics including social sciences, humanities, education, and science. It is therefore a good place to begin to do secondary source research. However, you can consult other databases such as the MLA International Bibliography , Project Muse , or JSTOR .

The above screen shot indicates how one might find scholarly articles related to the topic of the Aeneid and Empire. I also checked the “Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals” box to limit my results. This search populates the following result list:

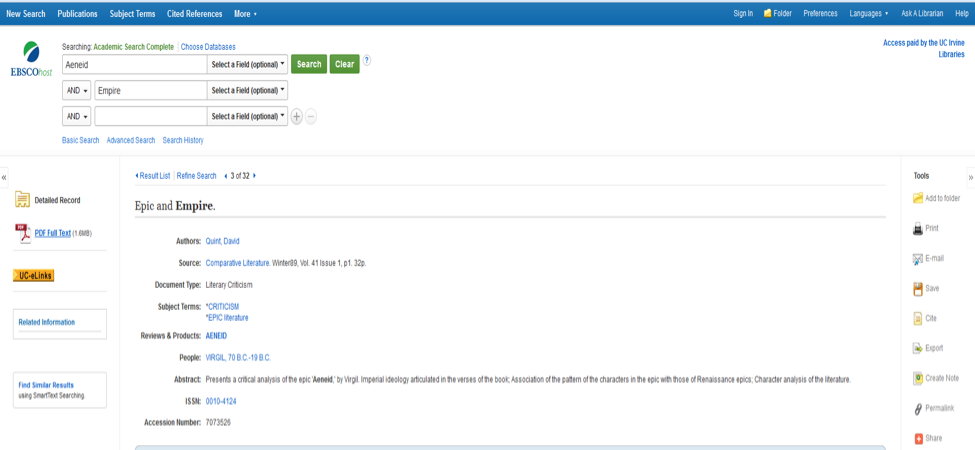

The article entitled “ Epic and Empire” appears directly related to our search. Selecting that article will open up the record for the article.

For this article, we can click on the “PDF Full Text” icon and download the article. For articles that do not have a link to the PDF, please click on the “UC E-Links” icon to search for alternative methods of access.

Please remember that secondary sources are interpretations. Consequently, as a researcher, situate yourself in an active role. In this way, you will understand that secondary sources should not speak for you or instead of you. Rather, you should integrate them into your analysis of a primary source to demonstrate your own contribution to a scholarly conversation on a topic that interests you. We do not do research simply to communicate how others have interpreted a primary source. We do research to discover how to interpret something for ourselves.

- Primary sources are original sources created at the time a historical event occurs and are directly associated with their creator. A primary source is the subjective interpretation of a witness to an event.

- Secondary sources are scholarly or popular sources that interpret a primary source and can be created long after the primary source was created.

- Research is a process that requires us to question and interrogate the information that we discover in order to interpret an object of study. It requires the evaluation and integration of both primary and secondary sources.

- The UCI Libraries have several research resources that can help you to discover and choose primary sources and secondary sources that interest you.

- Research Librarians at the UCI Libraries are here to help you!

Please note that you will be able to take advantage of several of the UCI Libraries’ instruction and reference services throughout the year. You can meet with research librarians who specialize in specific disciplines to learn more about conducting searches and vetting sources.

Works Cited

Arndt, Ava. “What to do with Primary Sources.” Humanities Core Writer’s Handbook: War, edited by Larisa Castillo, Pearson, 2014, pp. 90-94.

Baldick, Chris. “Diction.” The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms . 3 rd ed., 2008. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199208272.001.0001. Accessed 12 September 2016.

Imamoto, Rebecca. Primary Sources for History: Primary Sources . University of California, Irvine. Sept. 2016. http://guides.lib.uci.edu/primary_sources. Accessed 12 September 2016.

Pan, David. “What are the Humanities?” Humanities Core Writer’s Handbook: War , edited by Larisa Castillo, Pearson, 2014, pp. 5-9.

Quint, David. “Epic and Empire.” Comparative Literature , vol. 26, no. 1, 2001, pp. 620-26.1. Academic Search Complete . Web. 16 Sept. 2016. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=7073526&site=ehost-live&scope=site. Accessed 16 September 2016.

Roberts, Matthew. Humanities Core Course . University of California, Irvine. Sept. 2016. http://guides.lib.uci.edu/primary_sources. Accessed 12 September 2016.

185 Humanities Instructional Building, UC Irvine , Irvine, CA 92697 [email protected] 949-824-1964 Instagram Privacy Policy

Instructor Access

New research shows how studying the humanities can benefit young people’s future careers and wider society

Studying a humanities degree at university gives young people vital skills which benefit them throughout their careers and prepare them for changes and uncertainty in the labour market, according to new research by Oxford University.

The report, called ‘The Value of the Humanities’, used an innovative methodology to understand how humanities graduates have fared over their whole careers – not just at a fixed point in time after graduation.

In the largest study of its kind, the report followed the career destinations of over 9,000 Oxford humanities graduates aged between 21 and 54 who entered the job market between 2000 and 2019, cross-referenced with UK government data on graduate outcomes and salaries. This was combined with in-depth interviews with around 100 alumni and current students, and interviews with employers from many sectors.

Further interviews with employers were carried out after the onset of COVID-19 and the impact it has had on the economy and the labour market to test how the report’s findings held up in a post-pandemic world. In fact, the report suggests that the pandemic has accelerated trends towards automation, digitalisation and flexible modes of working, and the resilience of humanities graduates makes them particularly well suited to navigate this changing environment. Recent developments in AI such as ChatGPT have only advanced predictions about imminent changes to the workplace brought by technology.

The report was commissioned by Oxford University’s Humanities Division and its lead author was Dr James Robson of the Oxford University’s Centre for Skills, Knowledge and Organisational Performance (SKOPE). It comes shortly after a report from the Higher Education Policy Institute which quantified the strength of the humanities in the UK.

Professor Dan Grimley, Head of Humanities at Oxford University, said: 'This report confirms what I and so many humanities graduates will already recognise: that the skills and experiences conferred by studying a humanities subject can transform their working life, their life as a whole, and the world around them.

'Students, graduates and employers noted that the resilience and adaptability developed during a humanities degree is particularly useful during big changes in the labour market – whether that’s triggered by a global financial crisis, changes caused by the rise of automation and AI technologies, or indeed a global pandemic.

'I often hear young people saying that they would love to continue studying music or languages or history or classics at A-level and beyond, but they fear it would compromise their ability to get an impactful job. I hope this report will convince them – and their parents and teachers – that they can continue studying the humanities subject they love and at the same time develop skills which employers report they are valuing more and more.'

Dame Emma Walmsley, CEO of GlaxoSmithKline who studied Classics and Modern Languages at Oxford, said: 'Being a humanities student at Oxford was foundational - to the curiosity, reserves of courage, and appetite for connectivity I have relied on deeply in life so far.'

The report’s key findings include:

1) Humanities graduates develop resilience, flexibility and skills to adapt to challenging and changing labour markets.

Employers interviewed for the report highlighted that disruption caused by COVID-19 and increased automation and digitisation will significantly change the nature of work in the next 5-10 years. The report said the “skills related to human interaction, communication and negotiation” learned while studying humanities will help them to meet future employer demands. This resilience helped graduates to cope and respond well to the impacts of the 2008 financial crisis. It seems set to have the same effect for graduates entering a post-COVID labour market characterised by increased digitalisation and remote working.

2) Humanities careers open a path to success in a wide range of employment sectors.

The business sector was the most common destination of humanities graduates (21%) over the period. 13% entered the legal profession and 13% went into the creative sector. There was a notable increase over time of graduates entering the ICT sector, particularly among women.

3) The skills developed by studying a humanities degree, such as communication, creativity and working in a team, are “highly valued and sought out by employers”.

Interviews with employers found they particularly valued the following traits in Humanities graduates:

- Critical thinking

- Strategic thinking

- An ability to synthesise and present complex information

- Empathy

- Creative problem-solving

This supports recent research by SKOPE and funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council which revealed how business leaders in the UK see “narrative” as an integral part of doing business in the 21 st century. They found that being able to devise, craft and deliver a successful narrative is a “pre-requisite” for senior executives and becoming increasingly necessary for employees at all levels.

4) Humanities graduates benefit from subject-specific learning.

As well as the more transferrable skills like communication, graduates interviewed in the report showed that they draw throughout their careers on the sense of self-formation and the deep understanding they gain through studying histories, languages, cultures and literature on a humanities course.

5) Studying humanities helps graduates to make “wider contributions to society”.

Many interviewees in the report said their degree has enabled them to make an essential contribution to addressing the major issues facing humanity, and informed their sense of public mission and commitment. This includes navigating “fake news” and social media manipulation; climate change; energy needs; and the ethical implications of Artificial Intelligence.

6) Humanities graduates have high levels of job satisfaction and many said their primary motivation for studying their subject was not financial.

The report found that studying humanities subjects had a “transformative impact” on people’s identities and lives. Nonetheless, the average earnings of graduates assessed in the report were well above the national average, with History and Modern Languages graduates earning the most.

Dr James Robson and his co-authors for the report concluded: 'These findings clearly show that Oxford Humanities graduates are successful at navigating the labour market and financially rewarded, but also see value as existing beyond measurable returns and linked with knowledge, personal development, individual agency, and public goods.

'They highlight the need to take a more nuanced approach to analysing the value of degree subjects in order to take into account longer term career trajectories, individual agency within the labour market, the transformative power of knowledge, and broader public contributions of degrees within economic, social, and political discourses.'

The report makes recommendations to universities, employers and government to help young people make a transition into work:

- Offer support for a smooth transition into the workplace

- Provide internships, focused in particular on less advantaged students

- Support skills development in digital and working in a team, and provide students with insights into the changing labour market.

The full report can be found at:

pdf Value of Humanities report.pdf 1.77 MB

DISCOVER MORE

- Support Oxford's research

- Partner with Oxford on research

- Study at Oxford

- Research jobs at Oxford

You can view all news or browse by category

Hilbert College Global Online Blog

Why are the humanities important, written by: hilbert college • feb 9, 2023.

Why Are the Humanities Important? ¶

Do you love art, literature, poetry and philosophy? Do you crave deep discussions about societal issues, the media we create and consume, and how humans make meaning?

The humanities are the academic disciplines of human culture, art, language and history. Unlike the sciences, which apply scientific methods to answer questions about the natural world and behavior, the humanities have no single method or tools of inquiry.

Students in the humanities study texts of all kinds—from ancient books and artworks to tweets and TV shows. They study the works of great thinkers throughout history, including the Buddha, Homer, Aristotle, Dante, Descartes, Nietzsche, Austen, Thoreau, Darwin, Marx, Du Bois and King.

Humanities careers can be deeply rewarding. For students having trouble choosing between the disciplines that the humanities have to offer, a degree in liberal studies may be the perfect path. A liberal studies program prepares students for various exciting careers and teaches lifelong learning skills that can aid graduates in any career path they take.

Why We Need the Humanities ¶

The humanities play a central role in shaping daily life. People sometimes think that to understand our society they must study facts: budget allocations, environmental patterns, available resources and so on. However, facts alone don’t motivate people. We care about facts only when they mean something to us. No one cares how many blades of grass grow on the White House lawn, for example.

Facts gain meaning in a larger context of human values. The humanities are important because they offer students opportunities to discover, understand and evaluate society’s values at various points in history and across every culture.

The fields of study in the humanities include the following:

- Literature —the study of the written word, including fiction, poetry and drama

- History —the study of documented human activity

- Philosophy —(literally translated from Greek as “the love of wisdom”) the study of ideas; comprising many subfields, including metaphysics, epistemology, ethics and aesthetics

- Visual arts —the study of artworks, such as painting, drawing, ceramics and sculpture

- Performing arts —the study of art created with the human body as the medium, such as theater, dance and music

Benefits of Studying the Humanities ¶

There are many reasons why the humanities are important, from personal development and intellectual curiosity to preparation for successful humanities careers—as well as careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) and the social sciences.

1. Learn How to Think and Communicate Well ¶

A liberal arts degree prepares students to think critically. Because the study of the humanities involves analyzing and understanding diverse and sometimes dense texts—such as ancient Greek plays, 16th century Dutch paintings, American jazz music and contemporary LGBTQ+ poetry—students become skilled at noticing and appreciating details that students educated in other fields might miss.

Humanities courses often ask students to engage with complex texts, ideas and artistic expressions; this can help them develop the critical thinking skills they need to understand and appreciate art, language and culture.

Humanities courses also give students the tools they need to communicate complex ideas in writing and speaking to a wide range of academic and nonacademic audiences. Students learn how to organize their ideas in a clear, organized way and write compelling arguments that can persuade their audiences.

2. Ask the Big Questions ¶

Students who earn a liberal arts degree gain a deeper understanding of human culture and history. Their classes present opportunities to learn about humans who lived long ago yet faced similar questions to us today:

- How can I live a meaningful life?

- What does it mean to be a good person?

- What’s it like to be myself?

- How can we live well with others, especially those who are different from us?

- What’s really important or worth doing?

3. Gain a Deeper Appreciation for Art, Language and Culture ¶

Humanities courses often explore art, language and culture from different parts of the world and in different languages. Through the study of art, music, literature and other forms of expression, students are exposed to a wide range of perspectives. In this way, the humanities help students understand and appreciate the diversity of human expression and, in turn, can deepen their enjoyment of the richness and complexity of human culture.

Additionally, the study of the humanities encourages students to put themselves in other people’s shoes, to grapple with their different experiences. Through liberal arts studies, students in the humanities can develop empathy that makes them better friends, citizens and members of diverse communities.

4. Understand Historical Context ¶

Humanities courses place artistic and cultural expressions within their historical context. This can help students understand how and why certain works were created and how they reflect the values and concerns of the time when they were produced.

5. Explore What Interests You ¶

Ultimately, the humanities attract students who have an interest in ideas, art, language and culture. Studying the humanities has the benefit of enabling students with these interests to explore their passions.

The bottom line? Studying the humanities can have several benefits. Students in the humanities develop:

- Critical thinking skills, such as the ability to analyze dense texts and understand arguments

- A richer understanding of human culture and history

- Keen communication and writing skills

- Enhanced capacity for creative expression

- Deeper empathy for people from different cultures

6. Prepare for Diverse Careers ¶

Humanities graduates are able to pursue various career paths. A broad liberal arts education prepares students for careers in fields such as education, journalism, law and business. A humanities degree can prepare graduates for:

- Research and analysis , such as market research, policy analysis and political consulting

- Nonprofit work , social work and advocacy

- Arts and media industries , such as museum and gallery support and media production

- Law, lobbying or government relations

- Business and management , such as in marketing, advertising or public relations

- Library and information science , or information technology

- Education , including teachers, curriculum designers and school administrators

- Content creation , including writing, editing and publishing

Employers value the strong critical thinking, communication and problem-solving skills that humanities degree holders possess.

5 Humanities Careers ¶

Humanities graduates gain the skills and experience to thrive in many different fields. Consider these five humanities careers and related fields for graduates with a liberal studies degree.

1. Public Relations Specialist ¶

Public relations (PR) specialists are professionals who help individuals, organizations and companies communicate with public audiences. First and foremost, their job is to manage their organizations’ or clients’ reputation. PR specialists use various tactics, such as social media, events like fundraisers and other media relations activities to shape and maintain their clients’ public image.

PR specialists have many different roles and responsibilities as part of their daily activities:

- Creating and distributing press releases

- Monitoring and analyzing media coverage (such as tracking their clients’ names in the news)

- Organizing events

- Responding to media inquiries

- Evaluating the effectiveness of PR campaigns

How a Liberal Studies Degree Prepares Graduates for PR ¶

Liberal studies majors are required to participate in class discussions and presentations, which can help them develop strong speaking skills. PR specialists often give presentations and speak to the media, so strong speaking skills are a must.

PR specialists must also be experts in their audience. The empathy and critical thinking skills that graduates develop while they earn their degree enables them to craft tailored, effective messages to diverse audiences as PR specialists.

Public Relations Specialist Salary ¶

The median annual salary for PR specialists was $62,800 in May 2021, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The BLS expects the demand for PR specialists to grow by 8% between 2021 and 2031, faster than the average for all occupations.

The earning potential for PR specialists can vary. The size of the employer can affect the salary, as can the PR specialist’s level of experience and education and the specific duties and responsibilities of the job.

In general, PR specialists working for big companies in dense urban areas tend to earn more than those working for smaller businesses or in rural areas. Also, PR specialists working in science, health care and technology tend to earn more than those working in other industries.

BLS data is a national average, and the salary can also vary by location; for example, since the cost of living is higher in California and New York, the average salaries in those states tend to be higher compared with those in other states.

2. Human Resources Specialist ¶

Human resources (HR) specialists are professionals who are responsible for recruiting, interviewing and hiring employees for an organization. They also handle employee relations, benefits and training. They play a critical role in maintaining a positive and productive work environment for all employees.

How a Liberal Studies Degree Prepares Graduates for HR ¶

Liberal studies majors hone their communication skills through coursework that requires them to write essays, discussion posts, talks and research papers. These skills are critical for HR specialists, who must communicate effectively with company stakeholders, such as employees, managers and corporate leaders.

Additionally, because students who major in liberal studies get to understand the human experience, their classes can provide deeper insight into human behavior, motivation and communication. This understanding can be beneficial in handling employee relations, conflict resolution and other HR-related issues.

Human Resources Specialist Salary ¶

The median annual salary for HR in the U.S. was $122,510 in May 2021, according to the BLS. The demand for HR specialists is expected to grow by 8% between 2021 and 2031, per the BLS, faster than the average for all occupations.

3. Political Scientist ¶

A liberal studies degree not only helps prepare students for media and HR jobs—careers that may be more commonly associated with humanities—but also prepares graduates for successful careers as political scientists.

Political scientists are professionals who study the theory and practice of politics, government and political systems. They use various research methods, such as statistical analysis and historical analysis, to study political phenomena: elections, public opinions, the effects of policy changes. They also predict political trends.

How the Humanities Help With Political Science Jobs ¶

Political scientists need to have a deep understanding of political institutions. They have the skills to analyze complex policy initiatives, evaluate campaign strategies and understand political changes over time.

A liberal studies program provides a solid foundation of critical thinking skills that can sustain a career in political science. First, liberal studies degrees can teach students about the histories and theories of politics. Knowing the history and context of political ideas can be useful when understanding and evaluating current political trends.

Second, graduates with a liberal studies degree become accustomed to communicating with diverse audiences. This is a must to communicate with the public about complex policies and political processes.

Political Scientist Specialist Salary ¶

According to the BLS, the median annual wage for political scientists was $122,510 in May 2021. The BLS projects that employment prospects for political scientists will grow by 6% between 2021 and 2031, about as fast as the average for all occupations.

4. Community Service Manager ¶

Community service managers are professionals who are responsible for overseeing and coordinating programs and services that benefit the local community. They may work for a government agency, nonprofit organization or community-based organization in community health, mental health or community social services.

Community service management includes the following:

- Training and overseeing community service staff and volunteers

- Securing and allocating resources to provide services such as housing assistance, food programs, job training and other forms of social support

- Developing and implementing efficient and effective community policies

- Fundraising and applying for grants grant to secure funding for their programs

In these and many other ways, community service managers play an important role in addressing social issues and improving the quality of life for people in their community.

Community Service Management and Liberal Studies ¶

Liberal studies prepares graduates for careers in community service management by providing the tools for analyzing and evaluating complex issues. These include tools to work through common dilemmas that community service managers may face. Such challenges include the following:

- What’s the best way to allocate scarce community mental health resources, such as limited numbers of counselors and social workers to support people experiencing housing instability?

- What’s the best way to monitor and measure the success of a community service initiative, such as a Meals on Wheels program to support food security for older adults?

- What’s the best way to recruit and train volunteers for community service programs, such as afterschool programs?

Because the humanities teach students how to think critically, graduates with a degree in liberal studies have the skills to think through these complex problems.

Community Service Manager Salary ¶

According to the BLS, the median annual wage for social and community managers was $74,000 in May 2021. The BLS projects that employment prospects for social and community managers will grow by 12% from 2021 to 2031, much faster than the average for all occupations.

5. High School Teacher ¶

High school teachers educate future generations, and graduates with a liberal studies degree have the foundation of critical thinking and communication skills to succeed in this important role.

We need great high school teachers more than ever. The U.S. had a shortage of 300,000 teachers in 2022, according to NPR and the National Education Association The teacher shortage particularly affected rural school districts, where the need for special education teachers is especially high.

How the Humanities Prepare Graduates to Teach ¶

Having a solid understanding of the humanities is important for individuals who want to become a great high school teacher. First, a degree that focuses on the humanities provides graduates with a deep understanding of the subjects that they’ll teach. Liberal studies degrees often include coursework in literature, history, visual arts and other subjects taught in high school, all of which can give graduates a strong foundation in the material.

Second, liberal studies courses often require students to read, analyze and interpret texts, helping future teachers develop the skills they need to effectively teach reading, writing and critical thinking to high school students.

Third, liberal studies courses often include coursework in research methods, which can help graduates develop the skills necessary to design and implement engaging and effective lesson plans.

Finally, liberal studies degrees often include classes on ethics, philosophy and cultural studies, which can give graduates the ability to understand and appreciate different perspectives, cultures and life experiences. This can help future teachers create inclusive and respectful learning environments and help students develop a sense of empathy and understanding toward others.

Overall, a humanities degree can provide graduates with the knowledge, skills and abilities needed to be effective high school teachers and make a positive impact on the lives of their students.

High School Teacher Salary ¶

According to the BLS, the median annual wage for high school teachers was $61,820 in May 2021. The BLS projects that the number of high school teacher jobs will grow by 5% between 2021 and 2031.

Take the Next Step in Your Humanities Career ¶

A bachelor’s degree in liberal studies is a key step toward a successful humanities career. Whether as a political scientist, a high school teacher or a public relations specialist, a range of careers awaits you. Hilbert College Global’s online Bachelor of Science in Liberal Studies offers students the unique opportunity to explore courses across the social sciences, humanities and natural sciences and craft a degree experience around the topics they’re most interested in. Through the liberal studies degree, you’ll gain a strong foundation of knowledge while developing critical thinking and communication skills to promote lifelong learning. Find out how Hilbert College Global can put you on the path to a rewarding career.

Indeed, “13 Jobs for Humanities Majors”

NPR, The Teacher Shortage Is Testing America’s Schools

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, High School Teachers

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Human Resources Specialists

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Political Scientists

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Public Relations Specialists

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Social and Community Service Managers

Recent Articles

Humanities vs. Liberal Arts: How Are They Different?

Hilbert college, feb 6, 2023.

What Is Liberal Studies? Curriculum, Benefits and Careers

Oct 27, 2022.

Starting a Podcast: Checklist and Resources

Dec 13, 2023, learn more about the benefits of receiving your degree from hilbert college.

- Accessibility Options:

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Search

- Skip to footer

- Office of Disability Services

- Request Assistance

- 305-284-2374

- High Contrast

- School of Architecture

- College of Arts and Sciences

- Miami Herbert Business School

- School of Communication

- School of Education and Human Development

- College of Engineering

- School of Law

- Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science

- Miller School of Medicine

- Frost School of Music

- School of Nursing and Health Studies

- The Graduate School

- Division of Continuing and International Education

- People Search

- Class Search

- IT Help and Support

- Privacy Statement

- Student Life

University of Miami

- Division of University Communications

- Office of Media Relations

- Miller School of Medicine Communications

- Hurricane Sports

- UM Media Experts

- Emergency Preparedness

Explore Topics

- Latest Headlines

- Arts and Humanities

- People and Community

- All Topics A to Z

Related Links

- Subscribe to Daily Newsletter

- Special Reports

- Social Networks

- Publications

- For the Media

- Find University Experts

- News and Info

- People and Culture

- Benefits and Discounts

- More Life@TheU Topics

- About Life@the U

- Connect and Share

- Contact Life@theU

- Faculty and Staff Events

- Student Events

- TheU Creates (Arts and Culture Events)

- Undergraduate Students: Important Dates and Deadlines

- Submit an Event

- Miami Magazine

- Faculty Affairs

- Student Affairs

- More News Sites

The importance of the humanities

By Amanda M. Perez 04-10-2019

The Center for the Humanities is highlighting the importance of the humanities at the University of Miami. Since its inception in 2009, the center has been committed to promoting and celebrating scholarly pursuits in the humanities and in interdisciplinary fields. In an effort to feature the stellar work of faculty and students pursuing various topics in the field, the center is collaborating with several student organizations and campus partners to offer an exhibition: “Inquiring Minds: Undergraduate Opportunities in Humanities Research.”

Daniela Baboun, a junior majoring in biology, classics and English, is one of six students participating in the event. She said she first became interested in humanities research during her second semester, after she enrolled in a “Greek and Roman Mythology” course taught by senior lecturer Han Tran. Seeking a way to get involved in research, Baboun immediately reached out to Tran, who suggested she assist her with her own research.

Baboun describes her decision to assist Tran as a turning point for her, and said that research in the humanities has helped her develop critical thinking skills, understand the viewpoints of others, and cultivate empathy.

As an aspiring physician, Baboun said she “values the research experience tremendously” and believes that by expanding her horizons, she has gained greater cultural competence, a critical component for the development of a good physician.