Related Expertise: Culture and Change Management , Business Strategy , Corporate Strategy

Five Case Studies of Transformation Excellence

November 03, 2014 By Lars Fæste , Jim Hemerling , Perry Keenan , and Martin Reeves

In a business environment characterized by greater volatility and more frequent disruptions, companies face a clear imperative: they must transform or fall behind. Yet most transformation efforts are highly complex initiatives that take years to implement. As a result, most fall short of their intended targets—in value, timing, or both. Based on client experience, The Boston Consulting Group has developed an approach to transformation that flips the odds in a company’s favor. What does that look like in the real world? Here are five company examples that show successful transformations, across a range of industries and locations.

VF’s Growth Transformation Creates Strong Value for Investors

Value creation is a powerful lens for identifying the initiatives that will have the greatest impact on a company’s transformation agenda and for understanding the potential value of the overall program for shareholders.

VF offers a compelling example of a company using a sharp focus on value creation to chart its transformation course. In the early 2000s, VF was a good company with strong management but limited organic growth. Its “jeanswear” and intimate-apparel businesses, although responsible for 80 percent of the company’s revenues, were mature, low-gross-margin segments. And the company’s cost-cutting initiatives were delivering diminishing returns. VF’s top line was essentially flat, at about $5 billion in annual revenues, with an unclear path to future growth. VF’s value creation had been driven by cost discipline and manufacturing efficiency, yet, to the frustration of management, VF had a lower valuation multiple than most of its peers.

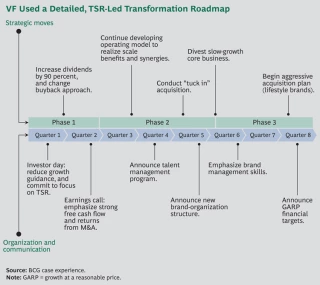

With BCG’s help, VF assessed its options and identified key levers to drive stronger and more-sustainable value creation. The result was a multiyear transformation comprising four components:

- A Strong Commitment to Value Creation as the Company’s Focus. Initially, VF cut back its growth guidance to signal to investors that it would not pursue growth opportunities at the expense of profitability. And as a sign of management’s commitment to balanced value creation, the company increased its dividend by 90 percent.

- Relentless Cost Management. VF built on its long-known operational excellence to develop an operating model focused on leveraging scale and synergies across its businesses through initiatives in sourcing, supply chain processes, and offshoring.

- A Major Transformation of the Portfolio. To help fund its journey, VF divested product lines worth about $1 billion in revenues, including its namesake intimate-apparel business. It used those resources to acquire nearly $2 billion worth of higher-growth, higher-margin brands, such as Vans, Nautica, and Reef. Overall, this shifted the balance of its portfolio from 70 percent low-growth heritage brands to 65 percent higher-growth lifestyle brands.

- The Creation of a High-Performance Culture. VF has created an ownership mind-set in its management ranks. More than 200 managers across all key businesses and regions received training in the underlying principles of value creation, and the performance of every brand and business is assessed in terms of its value contribution. In addition, VF strengthened its management bench through a dedicated talent-management program and selective high-profile hires. (For an illustration of VF’s transformation roadmap, see the exhibit.)

The results of VF’s TSR-led transformation are apparent. 1 1 For a detailed description of the VF journey, see the 2013 Value Creators Report, Unlocking New Sources of Value Creation , BCG report, September 2013. Notes: 1 For a detailed description of the VF journey, see the 2013 Value Creators Report, Unlocking New Sources of Value Creation , BCG report, September 2013. The company’s revenues have grown from $7 billion in 2008 to more than $11 billion in 2013 (and revenues are projected to top $17 billion by 2017). At the same time, profitability has improved substantially, highlighted by a gross margin of 48 percent as of mid-2014. The company’s stock price quadrupled from $15 per share in 2005 to more than $65 per share in September 2014, while paying about 2 percent a year in dividends. As a result, the company has ranked in the top quintile of the S&P 500 in terms of TSR over the past ten years.

A Consumer-Packaged-Goods Company Uses Several Levers to Fund Its Transformation Journey

A leading consumer-packaged-goods (CPG) player was struggling to respond to challenging market dynamics, particularly in the value-based segments and at the price points where it was strongest. The near- and medium-term forecasts looked even worse, with likely contractions in sales volume and potentially even in revenues. A comprehensive transformation effort was needed.

To fund the journey, the company looked at several cost-reduction initiatives, including logistics. Previously, the company had worked with a large number of logistics providers, causing it to miss out on scale efficiencies.

To improve, it bundled all transportation spending, across the entire network (both inbound to production facilities and out-bound to its various distribution channels), and opened it to bidding through a request-for-proposal process. As a result, the company was able to save 10 percent on logistics in the first 12 months—a very fast gain for what is essentially a commodity service.

Similarly, the company addressed its marketing-agency spending. A benchmark analysis revealed that the company had been paying rates well above the market average and getting fewer hours per full-time equivalent each year than the market standard. By getting both rates and hours in line, the company managed to save more than 10 percent on its agency spending—and those savings were immediately reinvested to enable the launch of what became a highly successful brand.

Next, the company pivoted to growth mode in order to win in the medium term. The measure with the biggest impact was pricing. The company operates in a category that is highly segmented across product lines and highly localized. Products that sell well in one region often do poorly in a neighboring state. Accordingly, it sought to de-average its pricing approach across locations, brands, and pack sizes, driving a 2 percent increase in EBIT.

Similarly, it analyzed trade promotion effectiveness by gathering and compiling data on the roughly 150,000 promotions that the company had run across channels, locations, brands, and pack sizes. The result was a 2 terabyte database tracking the historical performance of all promotions.

Using that information, the company could make smarter decisions about which promotions should be scrapped, which should be tweaked, and which should merit a greater push. The result was another 2 percent increase in EBIT. Critically, this was a clear capability that the company built up internally, with the objective of continually strengthening its trade-promotion performance over time, and that has continued to pay annual dividends.

Finally, the company launched a significant initiative in targeted distribution. Before the transformation, the company’s distributors made decisions regarding product stocking in independent retail locations that were largely intuitive. To improve its distribution, the company leveraged big data to analyze historical sales performance for segments, brands, and individual SKUs within a roughly ten-mile radius of that retail location. On the basis of that analysis, the company was able to identify the five SKUs likely to sell best that were currently not in a particular store. The company put this tool on a mobile platform and is in the process of rolling it out to the distributor base. (Currently, approximately 60 percent of distributors, representing about 80 percent of sales volume, are rolling it out.) Without any changes to the product lineup, that measure has driven a 4 percent jump in gross sales.

Throughout the process, management had a strong change-management effort in place. For example, senior leaders communicated the goals of the transformation to employees through town hall meetings. Cognizant of how stressful transformations can be for employees—particularly during the early efforts to fund the journey, which often emphasize cost reductions—the company aggressively talked about how those savings were being reinvested into the business to drive growth (for example, investments into the most effective trade promotions and the brands that showed the greatest sales-growth potential).

In the aggregate, the transformation led to a much stronger EBIT performance, with increases of nearly $100 million in fiscal 2013 and far more anticipated in 2014 and 2015. The company’s premium products now make up a much bigger part of the portfolio. And the company is better positioned to compete in its market.

A Leading Bank Uses a Lean Approach to Transform Its Target Operating Model

A leading bank in Europe is in the process of a multiyear transformation of its operating model. Prior to this effort, a benchmarking analysis found that the bank was lagging behind its peers in several aspects. Branch employees handled fewer customers and sold fewer new products, and back-office processing times for new products were slow. Customer feedback was poor, and rework rates were high, especially at the interface between the front and back offices. Activities that could have been managed centrally were handled at local levels, increasing complexity and cost. Harmonization across borders—albeit a challenge given that the bank operates in many countries—was limited. However, the benchmark also highlighted many strengths that provided a basis for further improvement, such as common platforms and efficient product-administration processes.

To address the gaps, the company set the design principles for a target operating model for its operations and launched a lean program to get there. Using an end-to-end process approach, all the bank’s activities were broken down into roughly 250 processes, covering everything that a customer could potentially experience. Each process was then optimized from end to end using lean tools. This approach breaks down silos and increases collaboration and transparency across both functions and organization layers.

Employees from different functions took an active role in the process improvements, participating in employee workshops in which they analyzed processes from the perspective of the customer. For a mortgage, the process was broken down into discrete steps, from the moment the customer walks into a branch or goes to the company website, until the house has changed owners. In the front office, the system was improved to strengthen management, including clear performance targets, preparation of branch managers for coaching roles, and training in root-cause problem solving. This new way of working and approaching problems has directly boosted both productivity and morale.

The bank is making sizable gains in performance as the program rolls through the organization. For example, front-office processing time for a mortgage has decreased by 33 percent and the bank can get a final answer to customers 36 percent faster. The call centers had a significant increase in first-call resolution. Even more important, customer satisfaction scores are increasing, and rework rates have been halved. For each process the bank revamps, it achieves a consistent 15 to 25 percent increase in productivity.

And the bank isn’t done yet. It is focusing on permanently embedding a change mind-set into the organization so that continuous improvement becomes the norm. This change capability will be essential as the bank continues on its transformation journey.

A German Health Insurer Transforms Itself to Better Serve Customers

Barmer GEK, Germany’s largest public health insurer, has a successful history spanning 130 years and has been named one of the top 100 brands in Germany. When its new CEO, Dr. Christoph Straub, took office in 2011, he quickly realized the need for action despite the company’s relatively good financial health. The company was still dealing with the postmerger integration of Barmer and GEK in 2010 and needed to adapt to a fast-changing and increasingly competitive market. It was losing ground to competitors in both market share and key financial benchmarks. Barmer GEK was suffering from overhead structures that kept it from delivering market-leading customer service and being cost efficient, even as competitors were improving their service offerings in a market where prices are fixed. Facing this fundamental challenge, Barmer GEK decided to launch a major transformation effort.

The goal of the transformation was to fundamentally improve the customer experience, with customer satisfaction as a benchmark of success. At the same time, Barmer GEK needed to improve its cost position and make tough choices to align its operations to better meet customer needs. As part of the first step in the transformation, the company launched a delayering program that streamlined management layers, leading to significant savings and notable side benefits including enhanced accountability, better decision making, and an increased customer focus. Delayering laid the path to win in the medium term through fundamental changes to the company’s business and operating model in order to set up the company for long-term success.

The company launched ambitious efforts to change the way things were traditionally done:

- A Better Client-Service Model. Barmer GEK is reducing the number of its branches by 50 percent, while transitioning to larger and more attractive service centers throughout Germany. More than 90 percent of customers will still be able to reach a service center within 20 minutes. To reach rural areas, mobile branches that can visit homes were created.

- Improved Customer Access. Because Barmer GEK wanted to make it easier for customers to access the company, it invested significantly in online services and full-service call centers. This led to a direct reduction in the number of customers who need to visit branches while maintaining high levels of customer satisfaction.

- Organization Simplification. A pillar of Barmer GEK’s transformation is the centralization and specialization of claim processing. By moving from 80 regional hubs to 40 specialized processing centers, the company is now using specialized administrators—who are more effective and efficient than under the old staffing model—and increased sharing of best practices.

Although Barmer GEK has strategically reduced its workforce in some areas—through proven concepts such as specialization and centralization of core processes—it has invested heavily in areas that are aligned with delivering value to the customer, increasing the number of customer-facing employees across the board. These changes have made Barmer GEK competitive on cost, with expected annual savings exceeding €300 million, as the company continues on its journey to deliver exceptional value to customers. Beyond being described in the German press as a “bold move,” the transformation has laid the groundwork for the successful future of the company.

Nokia’s Leader-Driven Transformation Reinvents the Company (Again)

We all remember Nokia as the company that once dominated the mobile-phone industry but subsequently had to exit that business. What is easily forgotten is that Nokia has radically and successfully reinvented itself several times in its 150-year history. This makes Nokia a prime example of a “serial transformer.”

In 2014, Nokia embarked on perhaps the most radical transformation in its history. During that year, Nokia had to make a radical choice: continue massively investing in its mobile-device business (its largest) or reinvent itself. The device business had been moving toward a difficult stalemate, generating dissatisfactory results and requiring increasing amounts of capital, which Nokia no longer had. At the same time, the company was in a 50-50 joint venture with Siemens—called Nokia Siemens Networks (NSN)—that sold networking equipment. NSN had been undergoing a massive turnaround and cost-reduction program, steadily improving its results.

When Microsoft expressed interest in taking over Nokia’s device business, Nokia chairman Risto Siilasmaa took the initiative. Over the course of six months, he and the executive team evaluated several alternatives and shaped a deal that would radically change Nokia’s trajectory: selling the mobile business to Microsoft. In parallel, Nokia CFO Timo Ihamuotila orchestrated another deal to buy out Siemens from the NSN joint venture, giving Nokia 100 percent control over the unit and forming the cash-generating core of the new Nokia. These deals have proved essential for Nokia to fund the journey. They were well-timed, well-executed moves at the right terms.

Right after these radical announcements, Nokia embarked on a strategy-led design period to win in the medium term with new people and a new organization, with Risto Siilasmaa as chairman and interim CEO. Nokia set up a new portfolio strategy, corporate structure, capital structure, robust business plans, and management team with president and CEO Rajeev Suri in charge. Nokia focused on delivering excellent operational results across its portfolio of three businesses while planning its next move: a leading position in technologies for a world in which everyone and everything will be connected.

Nokia’s share price has steadily climbed. Its enterprise value has grown 12-fold since bottoming out in July 2012. The company has returned billions of dollars of cash to its shareholders and is once again the most valuable company in Finland. The next few years will demonstrate how this chapter in Nokia’s 150-year history of serial transformation will again reinvent the company.

Managing Director & Senior Partner

San Francisco - Bay Area

Managing Director & Senior Partner, Chairman of the BCG Henderson Institute

ABOUT BOSTON CONSULTING GROUP

Boston Consulting Group partners with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities. BCG was the pioneer in business strategy when it was founded in 1963. Today, we work closely with clients to embrace a transformational approach aimed at benefiting all stakeholders—empowering organizations to grow, build sustainable competitive advantage, and drive positive societal impact.

Our diverse, global teams bring deep industry and functional expertise and a range of perspectives that question the status quo and spark change. BCG delivers solutions through leading-edge management consulting, technology and design, and corporate and digital ventures. We work in a uniquely collaborative model across the firm and throughout all levels of the client organization, fueled by the goal of helping our clients thrive and enabling them to make the world a better place.

© Boston Consulting Group 2024. All rights reserved.

For information or permission to reprint, please contact BCG at [email protected] . To find the latest BCG content and register to receive e-alerts on this topic or others, please visit bcg.com . Follow Boston Consulting Group on Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) .

Subscribe to our Business Transformation E-Alert.

JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser.

Hello! You are viewing this site in ${language} language. Is this correct?

Explore the Levels of Change Management

9 Successful Change Management Examples For Inspiration

Updated: February 9, 2024

Published: January 3, 2024

Welcome to our guide on change management examples, pivotal for steering through today's dynamic business terrain. Immerse yourself in the transformative power of change management, a tool for resilience, growth, innovation, and employee morale enhancement.

This guide equips you with strategies to promote an innovative, adaptable work environment and boost employee morale for lasting organizational success.

Uncover diverse types of change management with Prosci's established methodology and explore real-world examples that illustrate these principles in action.

What is Change Management?

Change management is a strategy for guiding an organization and its people through change. It goes beyond top-down orders, involving employees at all levels. This people-focused approach encourages everyone to participate actively, helping them adapt and use changes in their everyday work.

Effective change management aligns closely with a company's culture, values, and beliefs.

When change fits well with these cultural aspects, it feels more natural and is easier for employees to adopt. This contributes to smoother transitions and leads to more successful and lasting organizational changes.

Why is Change Management Important?

Change management is pivotal in guiding organizations through transitions, ensuring impactful and long-lasting results.

For example, a $28B electronic components and services company with 18,000 employees realized the importance of enhancing its processes. They knew to adopt more streamlined, efficient approaches, known as Lean initiatives .

However, they encountered challenges because they needed a more structured method for effectively managing the human aspects of these changes.

The company formed a specialized group focused on change to address their challenges and initiate key projects. These projects aligned with their culture of innovation and precision, which helped ensure that the changes were well-received and effectively implemented within the organization.

Matching change management to an organization's unique style and structure contributes to more effective transformations and strengthens the business for future challenges.

What Are the Main Types of Change Management?

Discover Prosci's change management models: from individual application and organizational strategies to enterprise-wide integration and effective portfolio management, all are vital for transformative success.

Individual change management

At Prosci, we understand that change begins with the individual.

The Prosci ADKAR ® Model ( Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability and Reinforcement ) is expertly designed to equip change leaders with tools and strategies to engage your team.

This model is a framework that will guide and support you in confidently navigating and adapting to new changes.

Organizational change management

In organizational change management , we focus on the core elements of your company to fully understand and address each aspect of the change.

Our approach involves creating tailored strategies and detailed plans that benefit you and manage you to manage challenges effectively, which include:

- Clear communication

- Strong leadership support

- Personalized coaching

- Practical training

Our strategies are specifically aimed at meeting the diverse needs within your organization, ensuring a smooth and well-supported transition for everyone involved.

Enterprise change management capability

At the enterprise level, change management becomes an embedded practice, a core competency woven throughout the organization.

When you implement change capabilities:

- Employees know what to ask during change to reach success

- Leaders and managers have the training and skills to guide their teams during change

- Organizations consistently apply change management to initiatives

- Organizations embed change management in roles, structures, processes, projects and leadership competencies

It's a tactical effort to integrate change management into the very DNA of an organization—nurturing a culture that's ready and able to adapt to any change.

Change portfolio management

While distinct from project-level change management, managing a change portfolio is vital for an organization to stay flexible and responsive.

9 Dynamic Change Management Success Stories to Revolutionize Your Business

Prosci case studies reveal how diverse organizations spanning different sectors address and manage change. These cases illustrate how change management can provide transformative solutions from healthcare to finance:

1. Hospital system

A major healthcare organization implemented an extensive enterprise resource planning (ERP) system and adapted to healthcare reform. This case study highlights overcoming significant challenges through strategic change management:

Industry: Healthcare Revenue: $3.7 billion Employees: 24,000 Facilities: 11 hospitals

Major changes:

- Implemented a new ERP system across all hospitals

- Prepared for healthcare reform

Challenges:

- Managing significant, disruptive changes

- Difficulty in gaining buy-in for change management

- Align with culture: Strategically implemented change management to support staff, reflecting the hospital's core value of caring for people

- Focus on a key initiative: Applied change management in the electronic health record system implementation

- Integrate with existing competencies: Recognized change leadership as crucial at various leadership levels

This example shows that when change management matches a healthcare organization's values, it can lead to successful and smooth transitions.

2. Transportation department

A state government transportation department leveraged change management to effectively manage business process improvements amid funding and population challenges. This highlights the value of comprehensive change management in a public sector setting:

Industry: State Government Transportation Revenue: $1.3 billion Employees: 3,000 Challenges:

- Reduced funding

- Growing population

- Increasing transportation needs

Initiative:

- Major business process improvement

Hurdles encountered:

- Change fatigue

- Need for widespread employee adoption

- Focus on internal growth

- Implemented change management in process improvement

This department's experience teaches us the vital role of change management in successfully navigating government projects with multiple challenges.

3. Pharmaceuticals

A global pharmaceutical company navigated post-merger integration challenges. Using a proactive change management approach, they addressed resistance and streamlined operations in a competitive industry:

Industry: Pharma (Global Biopharmaceutical Company) Revenue: $6 billion Number of employees: 5,000

Recent activities: Experienced significant merger and acquisition activity

- Encountered resistance post-implementation of SAP (Systems, Applications and Products in Data Processing)

- They found themselves operating in a purely reactive mode

- Align with your culture: In this Lean Six Sigma-focused environment, where measurement is paramount, the ADKAR Model's metrics were utilized as the foundational entry point for initiating change management processes.

This company's journey highlights the need for flexible and responsive change management.

4. Home fixtures

A home fixtures manufacturing company’s response to the recession offers valuable insights on effectively managing change. They focused on aligning change management with their disciplined culture, emphasizing operational efficiency:

Industry: Home Fixtures Manufacturing Revenue: $600 million Number of employees: 3,000

Context: Facing the lingering effects of the recession

Necessity: Need to introduce substantial changes for more efficient operations

Challenge: Change management was considered a low priority within the company

- Align with your culture: The company's culture, characterized by discipline in projects and processes, ensured that change management was implemented systematically and disciplined.

This company’s experience during the recession proves that aligning change with company culture is key to overcoming tough times.

5. Web services

A web services software company transformed its culture and workspace. They integrated change management into their IT strategy to overcome resistance and foster innovation:

Industry : Web Services Software Revenue : $3.3 billion Number of employees : 10,000

Initiatives : Cultural transformation; applying an unassigned seating model

Challenges : Resistance in IT project management

- Focus on a key initiative: Applied change management in workspace transformation

- Go where the energy is: Establishing a change management practice within its IT department, developing self-service change management tools, and forming thoughtful partnerships

- I ntegrate with existing competencies: "Leading change" was essential to the organization's newly developed leadership competency model.

This case demonstrates the importance of weaving change management into the fabric of tech companies, especially for cultural shifts.

6. Security systems

A high-tech security company effectively managed a major restructuring. They created a change network that shifted change management from HR to business processes:

Industry : High-Tech (Security Systems) Revenue : $10 billion Number of employees: 57,000

Major changes : Company separation; division into three segments

Challenge : No unified change management approach

- Formed a network of leaders from transformation projects

- Go where the energy is: Shifted change management from HR to business processes

- Integrate with existing competencies: Included principles of change management in the training curriculum for the project management boot camp.

- Treat growing your capability like a change: Executive roadshow launch to gain support for enterprise-wide change management

This company’s innovative approach to restructuring shows h ow reimagining change management can lead to successful outcomes.

7. Clothing store

A major clothing retailer’s journey to unify its brand model. They overcame siloed change management through collaborative efforts and a community-driven approach:

Industry : Retail (Clothing Store) Revenue : $16 billion Number of employees : 141,000

Major change initiative : Strategic unification of the brand operating model

Historical challenge : Traditional management of change in siloes

- Build a change network : This retailer established a community of practice for change management, involving representatives from autonomous units to foster consensus on change initiatives.

The story of this retailer illustrates how collaborative efforts in change management can unify and strengthen a brand in the retail world.

A major Canadian bank initiative to standardize change management across its organization. They established a Center of Excellence and tailored communities of practice for effective change:

Industry : Financial Services (Canadian Bank) Revenue : $38 billion Number of employees : 78,000

Current state : Absence of enterprise-wide change management standards

Challenge :

- Employees, contractors, and consultants using individual methods for change management

- Reliance on personal knowledge and experience to deploy change management strategies

- Build a change network: The bank established a Center of Excellence and created federated communities of practice within each business unit, aiming to localize and tailor change management efforts.

This bank’s journey in standardizing change management offers valuable insights for large organizations looking to streamline their processes.

9. Municipality

You can learn from a Canadian municipality’s significant shift to enhance client satisfaction. They integrated change management across all levels to achieve profound organizational change and improved public service:

Industry : Municipal Government (Canadian Municipality) Revenue : $1.9 billion Number of employees : 3,000

New mandate:

- Implementing a new deliberate vision focusing on each individual’s role in driving client satisfaction

Nature of shift :

- A fundamental change within the public institution

Scope of impact :

- It affected all levels, from leadership to front-line staff

Solution :

- Treat growing your capability like a change: Change leaders promoted awareness and cultivated a desire to adopt change management as a standard enterprise-wide practice.

The municipality's strategy shows us how effective change management can significantly improve public services and organizational efficiency.

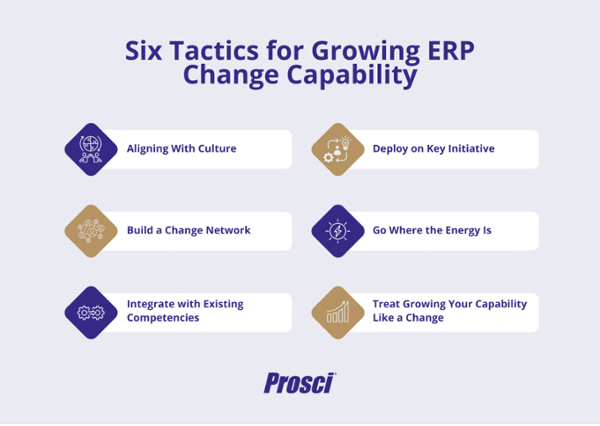

6 Tactics for Growing Enterprise Change Management Capability

Prosci's exploration with 10 industry leaders uncovered six primary tactics for enterprise change growth , demonstrating a "universal theme, unique application" approach.

This framework goes beyond standard procedures, focusing on developing a deep understanding and skill in managing change. It offers transformative tactics, guiding organizations towards excelling in adapting to change. Here, we uncover these transformative tactics, guiding organizations toward mastery of change.

1. Align with Your culture

Organizational culture profoundly influences how change management should be deployed.

Recognizing whether your organization leans towards traditional practices or innovative approaches is vital. This understanding isn't just about alignment; it's an opportunity to enhance and sometimes shift your cultural environment.

When effectively combined with an organization's unique culture, change management can greatly enhance key initiatives. This leads to widespread benefits beyond individual projects and promotes overall growth and development within the organization.

Embrace this as a fundamental tool to strengthen and transform your company's cultural fabric.

2. Focus on key initiatives

In the early phase of developing change management capabilities, selecting noticeable projects with executive backing is important.

This helps demonstrate the real-world impact of change management, making it easier for employees and leadership to understand its benefits. This strategy helps build support and maintain the momentum of change management initiatives within your organization.

Focus on capturing and sharing these successes to encourage buy-in further and underscore the importance of change management in achieving organizational goals.

3. Build a change network

Building change capability isn't just about a few advocates but creating a network of change champions across your organization.

This network, essential in spreading the message and benefits of change management, varies in composition but is universally crucial. It could include departmental practitioners, business unit leaders, or a mix of roles working together to enhance awareness, credibility, and a shared purpose.

Our Best Practices in Change Management study shows that 45% of organizations leverage such networks. These groups boost the effectiveness of change management and keep it moving forward.

4. Go where the energy is

To build change capabilities throughout an organization effectively, the focus should be on matching the organization's current readiness rather than just pushing new methods.

Identify and focus on parts of your organization that are ready for change. Align your change initiatives with these sectors. Involve senior leaders and those enthusiastic about change to naturally generate demand for these transformations.

Showcasing successful initiatives encourages a collaborative culture of change, making it an organic part of your organization's growth.

5. Integrate with existing competencies

Change management is a vital skill across various organizational roles.

Integrating it into competency models and job profiles is increasingly common, yet often lacks the necessary training and tools.

When change management skills expand beyond the experts, they become an integral part of the organization's culture—nurturing a solid foundation of effective change leadership.

This approach embeds change management deeper within the company and cultivates leaders who can support and sustain this essential practice.

6. Treat growing your capability like a change

Growing change capability is a transformative journey for your business and your employees. It demands a structured, strategic approach beyond telling your network that change is coming.

Applying the ADKAR Model universally and focusing on your organization's unique needs is pivotal. It's about building awareness, sparking a desire for change across the enterprise, and equipping employees with the knowledge and skills for effective, lasting change.

Treating capability-building like a change ensures that change management becomes a core part of your organization's fabric, benefitting every team member.

These six tactics are powerful tools for enhancing your organization's ability to adapt and remain resilient in a rapidly changing business environment.

Comprehensive Insights From Change Management Examples

These diverse change management examples provide field-tested savvy and offer a window into how varied organizations successfully manage change.

Case studies , from healthcare reform to innovative corporate restructuring, exemplify how aligning with organizational culture, building strong change networks, and focusing on tactical initiatives can significantly impact change management outcomes.

This guide, enriched with real-world applications, enhances understanding and execution of effective change management, setting a benchmark for future transformations.

To learn more about partnering with Prosci for your next change initiative, discover Prosci's Advisory services and enterprise training options and consider practitioner certification .

Founded in 1994, Prosci is a global leader in change management. We enable organizations around the world to achieve change outcomes and grow change capability through change management solutions based on holistic, research-based, easy-to-use tools, methodologies and services.

See all posts from Prosci

You Might Also Like

Enterprise - 8 MINS

What Is Change Management in Healthcare?

20 Change Management Questions Employees Ask and How To Answer Them

Subscribe here.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What Really Makes Toyota’s Production System Resilient

- Willy C. Shih

“Just-in-time” only works as part of a comprehensive suite of strategies.

Toyota has fared better than many of its competitors in riding out the supply chain disruptions of recent years. But focusing on how Toyota had stockpiled semiconductors and the problems of other manufacturers, some observers jumped to the conclusion that the era of the vaunted Toyota Production System was over. Not the case, say Toyota executives. TPS is alive and well and is a key reason Toyota has outperformed rivals.

The supply chain disruptions triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic caused major headaches for manufacturers around the world. Nowhere was this felt more acutely than in the auto industry, which faced severe shortages of semiconductor chips and other components. This led many people to argue that just-in-time and lean production methods were dead and being superseded by “just-in-case” stocking of more inventory.

- Willy C. Shih is a Baker Foundation Professor of Management Practice at Harvard Business School.

Partner Center

Do people fear change?

Do people resist change?

If we do resist change, why and when do we resist change? How do we as leaders, change agents, project managers, coaches or scrum masters respond when we find resistance?

Change resistance is a positive for me!

It gives me a number of insights - maybe the change isn’t the correct one or perhaps the timing of bringing the change isn’t right or so many other reasons!

Pushing the change at people impacted by the change is not going to give me any additional benefit (unless I want to just put a check in the box - which I would not ofcourse!).

So, what do I do? What approaches could I take, given my unique context? What's your perspective?

Bringing you a real-life case study from my experience, along with a meaningful dialogue with you, around responding to change.

Join me Wednesday 15 June 1230 - 1330 CEST

A Lean Approach for Reducing Downtimes in Healthcare: A Case Study

- Conference paper

- First Online: 12 February 2023

- Cite this conference paper

- Stefano Frecassetti ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9649-314X 19 ,

- Matteo Ferrazzi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9035-0773 19 &

- Alberto Portioli-Staudacher ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9807-1215 19

Part of the book series: IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology ((IFIPAICT,volume 668))

Included in the following conference series:

- European Lean Educator Conference

447 Accesses

Lean Management is considered one of the most successful management paradigms for enhancing operational performance in the manufacturing environment. However, it has been applied throughout the years to several sectors and organisational areas, such as service, healthcare, and office departments. After the Covid-19 outbreak, increasing attention has been given to potential performance improvements in healthcare organisations by leveraging Lean. This paper intends to add further knowledge to this field by presenting a case study in a hospital. In this paper, a pilot project is presented carried out in a healthcare organisation. Lean methods were used to improve the operating room performance, particularly by reducing the operating room changeover time. The A3 template was used to drive the project and implement a new procedure using the Single Minute Exchange of Die (SMED) method. With the implementation of the new procedure, the changeover time between two different surgeries in the operating room was significantly reduced, together with a more stable and reliable process.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Lean Healthcare

Lean Healthcare: How to Start the Lean Journey

Lean Transformation in Healthcare: A French Case Study

Amati, M., et al.: Reducing changeover time between surgeries through lean thinking: an action research project. Front. Med. 9 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.822964

Bharsakade, R.S., Acharya, P., Ganapathy, L., Tiwari, M.K.: A lean approach to healthcare management using multi criteria decision making. Opsearch 58 (3), 610–635 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12597-020-00490-5

Article Google Scholar

Costa, F., Kassem, B., Staudacher, A.P.: Lean office in a manufacturing company. In: Powell, D.J., Alfnes, E., Holmemo, M.D.Q., Reke, E. (eds.) Learning in the Digital Era. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, pp. 351–356. Springer, Cham (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92934-3_36

Chapter Google Scholar

Costa, F., Kassem, B., Portioli-Staudacher, A.: Lean thinking application in the healthcare sector. In: Powell, D.J., Alfnes, E., Holmemo, M.D.Q., Reke, E. (eds.) Learning in the Digital Era. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, pp. 357–364. Springer, Cham (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92934-3_37

Curatolo, N., Lamouri, S., Huet, J.C., Rieutord, A.: A critical analysis of Lean approach structuring in hospitals. Bus. Process Manag. J. 20 (3), 433–454 (2014)

D’Andreamatteo, A., Iannia, L., Lega, F., Sargiacomo, M.: Lean in healthcare: a comprehensive review. Health Policy 119 (9), 1197–1209 (2015)

Guercini, J., et al.: Application of SMED methodology for the improvement of operations in operating theatres. The case of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese. Mecosan 24 (98), 83–203 (2016). https://doi.org/10.3280/mesa2016-098005

Henrique, D.B., Godinho Filho, M.: A systematic literature review of empirical research in Lean and Six Sigma in healthcare. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 31 (3–4), 429–449 (2020)

Henrique, D.B., Filho, M.G., Marodin, G., Jabbour, A.B.L.D.S., Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.: A framework to assess sustaining continuous improvement in lean healthcare. Int. J. Prod. Res. 59 (10), 2885–2904 (2020)

Holweg, M.: The genealogy of lean production. J. Oper. Manag. 25 (2), 420–437 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2006.04.001

Sales-Coll, M., de Castro, R., Hueto-Madrid, J.A.: Improving operating room efficiency using lean management tools. Prod. Plan. Control 1–14 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2021.1998932

Matos, I.A., Alves, A.C., Tereso, A.P.: Lean principles in an operating room environment: an action research study. J. Health Manag. 18 (2), 239–2577 (2016)

Portioli-Staudacher, A.: Lean healthcare. An experience in Italy. In: Koch, T. (ed.) APMS 2006. ITIFIP, vol. 257, pp. 485–492. Springer, Boston, MA (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-77249-3_50

Rosa, A., Marolla, G., Lega, F., et al.: Lean adoption in hospitals: the role of contextual factors and introduction strategy. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21 , 889 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06885-4

Rosa, C., Silva, F.J.G., Ferreira, L.P., Campilho, R.D.S.G.: SMED methodology: the reduction of setup times for Steel Wire-Rope assembly lines in the automotive industry. Procedia Manuf. 13 , 1034–1042 (2017)

Shah, R., Ward, P.T.: Lean manufacturing: context, practice bundles, and performance. J. Oper. Manag. 21 (2), 129–149 (2003)

Sunder, M.V., Mahalingam, S., Krishna, M.S.N.: Improving patients’ satisfaction in a mobile hospital using Lean Six Sigma – a design-thinking intervention. Prod. Plan. Control 31 (6), 512–526 (2020)

Torri, M., Kundu, K., Frecassetti, S., Rossini, M.: Implementation of Lean in IT SME company: an Italian case. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma (2021)

Google Scholar

Welsh, I., Lyons, C.M.: Evidence-based care and the case for intuition and tacit knowledge in clinical assessment and decision making in mental health nursing practice: an empirical contribution to the debate. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 8 (4), 299–305 (2001)

Yin, R.K.: Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th edn. Sage, Los Angeles (2018)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Politecnico di Milano, Department of Management, Economics and Industrial Engineering, Milano, Italy

Stefano Frecassetti, Matteo Ferrazzi & Alberto Portioli-Staudacher

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stefano Frecassetti .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Galway, Galway, Ireland

Olivia McDermott

LUM University "Giuseppe Degennaro", Casamassima, Italy

Angelo Rosa

Instituto Superior de Engenharia do Porto, Porto, Portugal

José Carlos Sá

Aidan Toner

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 IFIP International Federation for Information Processing

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Frecassetti, S., Ferrazzi, M., Portioli-Staudacher, A. (2023). A Lean Approach for Reducing Downtimes in Healthcare: A Case Study. In: McDermott, O., Rosa, A., Sá, J.C., Toner, A. (eds) Lean, Green and Sustainability. ELEC 2022. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, vol 668. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25741-4_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25741-4_8

Published : 12 February 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-25740-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-25741-4

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

Societies and partnerships

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Change Management Case Study- Toyota

Change management is a critical aspect of any organization’s success, especially in today’s fast-paced and constantly evolving business environment.

One company that has been widely recognized for its innovative and successful approach to change management is Toyota.

Over the years, Toyota has implemented a range of initiatives aimed at improving its operations, products, and services, from introducing the world’s first mass-produced hybrid car to adopting robots in its production lines.

In this blog post, we will explore Toyota’s approach to change management, looking at how the company’s philosophy and practices have enabled it to continuously innovate and improve.

Overview of Toyota and its history of innovation and improvement

Toyota is a Japanese multinational automotive manufacturer that was founded in 1937. The company is widely recognized for its innovative and efficient production system, known as the Toyota Production System (TPS), which has become a model for manufacturing excellence.

Toyota’s commitment to continuous improvement and innovation has resulted in many breakthroughs in the automotive industry, including the introduction of the first mass-produced hybrid car, the Toyota Prius, in 1997. The company has also been a pioneer in the use of robotics in production and has continuously worked to improve the safety and efficiency of its vehicles. Today, Toyota is one of the largest automakers in the world, with a reputation for quality, reliability, and innovation.

Toyota Production System

The Toyota Production System (TPS) is a lean manufacturing system developed by Toyota that focuses on reducing waste and maximizing efficiency in production. At the heart of TPS are two key principles: the first is to identify and eliminate all forms of waste in the production process, and the second is to continuously improve the production process.

TPS involves several key concepts and tools, including just-in-time (JIT) production, kanban (visual signals used to control the flow of materials), and andon (alerts used to signal production problems).

JIT involves producing only what is needed, when it is needed, and in the exact amount required. Kanban is a scheduling system that uses visual signals to control the flow of materials, while andon allows workers to stop production when a problem arises and signal for help.

TPS is not just a set of tools and concepts, but also a philosophy and way of working that involves change management at every level of the organization. All employees are encouraged to identify and suggest improvements to the production process, which are then tested and implemented on a small scale before being rolled out across the organization. This approach to continuous improvement is known as kaizen, and it has become a central part of Toyota’s culture and way of working.

Change Management at Toyota

Change management is also built into TPS through a system called Hoshin Kanri, which involves a top-down approach to strategic planning and goal setting. In this system, senior leaders set the direction for the organization, and then work with middle managers and front-line workers to implement changes and improvements that align with the overall strategy. This ensures that change is managed in a structured and coordinated way across the organization, with everyone working towards the same goals.

Examples of change management at Toyota

Toyota’s approach to change management is grounded in its core values of respect for people and continuous improvement. The company has a long history of successful change initiatives that have allowed it to stay at the forefront of the automotive industry. Here are two examples of successful change initiatives at Toyota:

- The Prius Hybrid: In 1997, Toyota introduced the world’s first mass-produced hybrid car, the Toyota Prius. The Prius was a radical departure from conventional gasoline-powered vehicles and represented a significant technological breakthrough. Toyota invested heavily in the development of the Prius, taking a long-term view of the potential for hybrid technology. The company faced numerous challenges in bringing the Prius to market, including concerns about the high cost of the hybrid system and doubts about consumer demand. However, Toyota remained committed to its vision of a more sustainable future and persisted in its efforts to improve and refine the Prius. Today, the Prius is a popular and widely recognized brand, with more than 10 million units sold worldwide.

- Introduction of Robots in Production: Toyota has been a pioneer in the use of robotics in production, starting with the introduction of the first industrial robot in 1967. Over the years, the company has continued to invest in robotics and automation, using these technologies to improve safety, quality, and efficiency in its production process. One example of a successful change initiative in this area was the introduction of collaborative robots, or “cobots,” in the assembly line. These robots work alongside human workers to perform repetitive or physically demanding tasks, freeing up workers to focus on more complex tasks that require human skills and judgment. This change has not only improved efficiency and safety but has also created a more engaging and satisfying work environment for employees.

These examples illustrate how Toyota’s commitment to continuous improvement and innovation has allowed it to successfully manage change and stay ahead of the curve in a rapidly evolving industry. By investing in new technologies and working collaboratively across the organization, Toyota has been able to achieve significant breakthroughs and maintain its position as a leader in the automotive industry.

Challenges faced by Toyota and how did it respond

Despite its many successes, Toyota has also faced several significant challenges in implementing change over the years. One of the most notable challenges was the series of recalls that the company experienced in the late 2000s and early 2010s.

These recalls were related to safety issues and quality problems with several models of Toyota vehicles, including issues with unintended acceleration and faulty brakes. These recalls had a significant impact on Toyota’s reputation and credibility, and the company faced intense scrutiny from regulators, consumers, and the media.

Toyota successfully implemented crisis management strategy in response to these challenges, Toyota implemented a number of changes to its production and quality control processes. The company established a new position of Chief Quality Officer and created a new division dedicated to product quality and safety.

Toyota also implemented new measures to improve communication and collaboration across the organization, including the creation of a global quality task force and the establishment of a new system for reporting and addressing quality issues.

Despite these challenges, Toyota has continued to innovate and improve, staying true to its commitment to continuous improvement and kaizen. The company has continued to invest in new technologies and has introduced several new models of hybrid and electric vehicles in recent years, including the Toyota Mirai hydrogen fuel cell vehicle.

Toyota has also continued to refine its production processes, implementing new systems and tools to improve efficiency and quality.

One notable example of Toyota’s continued innovation is the development of the Toyota New Global Architecture (TNGA) platform. This platform is designed to be more flexible and adaptable than previous platforms, allowing Toyota to build a wider range of vehicles with greater efficiency and quality.

The TNGA platform has already been used in several models, including the Toyota Camry and the Toyota Prius, and has received widespread praise for its performance and capabilities.

Results and Impact of successful implementation of change by Toyota

The successful implementation of change by Toyota has had a significant impact on the company, its employees, and the automotive industry as a whole. Here are some of the key results and impacts of Toyota’s successful change initiatives:

- Improved Efficiency and Quality : Toyota’s focus on continuous improvement and innovation has led to significant gains in efficiency and quality. The company’s production processes are now more streamlined and standardized, and its vehicles are known for their reliability and durability. This has helped Toyota to maintain its reputation as a leader in the automotive industry and has helped the company to remain competitive in a rapidly changing market.

- Increased Innovation: Toyota’s commitment to innovation has resulted in the development of several groundbreaking technologies, including the Prius hybrid, the Mirai fuel cell vehicle, and the TNGA platform. These innovations have not only helped to improve the performance and sustainability of Toyota’s vehicles but have also helped to push the entire industry forward, setting new standards and raising the bar for other automakers.

- Enhanced Employee Engagement and Satisfaction: Toyota’s focus on respect for people and employee engagement has created a culture of collaboration and teamwork within the organization. Employees are encouraged to contribute ideas and participate in continuous improvement initiatives, which has helped to create a more engaging and fulfilling work environment. This has contributed to high levels of employee satisfaction and retention at Toyota.

- Improved Safety and Sustainability: Toyota’s commitment to safety and sustainability has led to the development of several technologies and processes aimed at reducing the environmental impact of its vehicles and improving the safety of its customers. These efforts have helped to reduce carbon emissions and improve safety on the road, making Toyota a leader in corporate social responsibility and sustainability.

Final Words

The experience of Toyota demonstrates the critical importance of effective change management in driving success and growth in any organization. By committing to a culture of continuous improvement, Toyota has been able to maintain its position as a leader in the automotive industry and set new standards for efficiency, quality, and innovation.

Effective change management is essential to driving success and growth in any organization. By learning from Toyota’s experience and embracing the lessons outlined above, organizations can create a culture of continuous improvement and innovation that drives long-term success and sustainability.

About The Author

Tahir Abbas

Related posts.

Tesla Change Management Case Study

08 Ways Change Managers Benefit from Resistance to Change

Too Much Change in an Organization – Consequences and How to Avoid it?

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 28 August 2021

Lean adoption in hospitals: the role of contextual factors and introduction strategy

- Angelo Rosa 1 ,

- Giuliano Marolla ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2095-8641 1 ,

- Federico Lega 2 &

- Francesco Manfredi 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 21 , Article number: 889 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

4792 Accesses

14 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

In the scientific literature, many studies describe the application of lean methodology in the hospital setting. Most of the articles focus on the results rather than on the approach adopted to introduce the lean methodology. In the absence of a clear view of the context and the introduction strategy, the first steps of the implementation process can take on an empirical, trial and error profile. Such implementation is time-consuming and resource-intensive and affects the adoption of the model at the organizational level. This research aims to outline the role contextual factors and introduction strategy play in supporting the operators introducing lean methodology in a hospital setting.

Methodology

The methodology is revealed in a case study of an important hospital in Southern Italy, where lean has been successfully introduced through a pilot project in the pathway of cancer patients. The originality of the research is seen in the detailed description of the contextual elements and the introduction strategy.

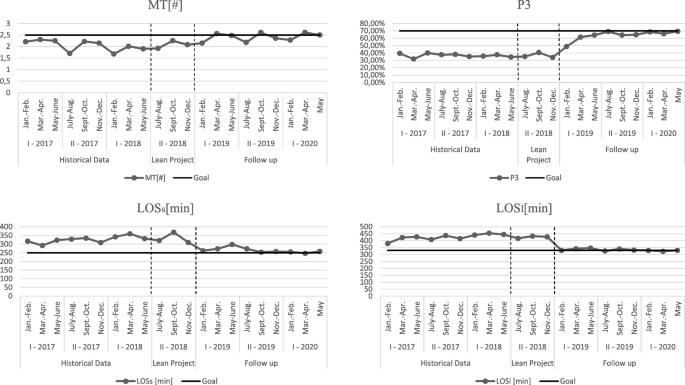

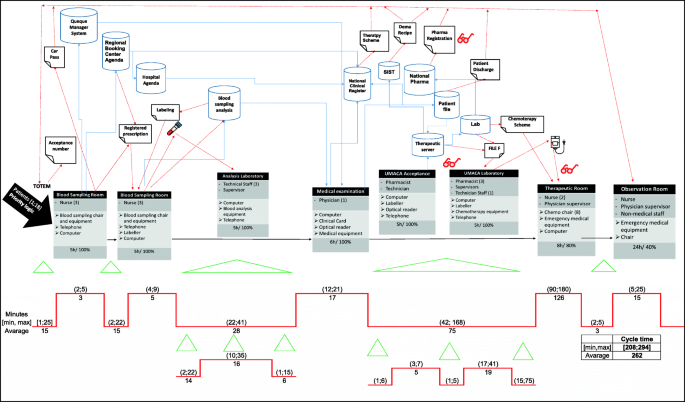

The results show significant process improvements and highlight the spontaneous dissemination of the culture of change in the organization and the streamlined adoption at the micro level.

The case study shows the importance of the lean introduction strategy and contextual factors for successful lean implementation. Furthermore, it shows how both factors influence each other, underlining the dynamism of the organizational system.

Peer Review reports

Over the last decade, healthcare has been called upon to respond to the increasing pressures arising from changes in demand – due to epidemiological changes and the demand for quality and safety – and increased costs due to the introduction of new technologies [ 1 , 2 ]. These major challenges are exacerbated by the shrinking resources available in health systems and, for most countries, by the principle of universal access to patient care. In order to meet the patients’ needs, a hospital must utilize a number of scarce resources at the right time: beds, technological equipment, staff with appropriate clinical skills, medical devices, diagnostic reports, etc. [ 1 , 2 ].

One of the most relevant issues for the management of a healthcare provider is the management of patient flows in order to purchase, make available, and use these scarce resources at the right time and in the right way, and to ensure the best possible care [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. In this scenario, hospitals need to focus on the patient pathways in order to ensure fast, safe, and high-quality service [ 3 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. The search for solutions to these challenges has extended beyond the boundaries of healthcare practices to study organizational methods and paradigms that have been successfully implemented in other sectors [ 3 , 5 ]. Among these, lean thinking has proven to be one of the most effective solutions for improving operational performance and process efficiency and for reducing waste [ 5 , 9 ]. Lean is a process-based methodology focused on improving processes to achieve a customer ideal state and the elimination of waste [ 10 ]. Waste is defined as the results of unnecessary or wrong tasks, actions or process steps that do not directly benefit the patient. The taxonomy of waste is: overproduction, defects, waiting, transportation, inventory, motion, extra-processing and unused talent [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. In addition, lean addresses other key service issues such as continuous improvement and employee empowerment, whether healthcare professionals or managers [ 1 , 11 , 12 ]. Lean healthcare is defined as a strategic approach to increasing the reliability and stability of healthcare processes [ 7 , 13 , 14 ].

The first documented cases of lean applications in a hospital setting (HS) date back to the late 1990s. These aimed at improving patient care processes, interdepartmental interaction, and employee satisfaction [ 1 , 2 ]. The Virginia Mason Medical Center is one of the first and most emblematic examples of a successful migration of lean methodology from the manufacturing sector to healthcare. The hospital, based on the principles of the Toyota Production System, created the Virginia Mason Production System, a holistic management model in continuous evolution that not only had a strong impact on the quality of the services provided and on the reduction of lead time, but it also led to a decrease in operating costs [ 14 , 15 ]. Over time, many hospitals have followed in the footsteps of the Virginia Mason Medical Center [ 8 , 16 , 17 ]. The lean paradigm crossed the US border and spread to other countries such as Canada and England [ 5 , 12 ]. It was not until the early 2000 that the model was introduced in European hospitals [ 12 , 16 ].

The implementation of the lean paradigm in HS environments has increasingly attracted the attention of researchers and professionals. The interest in lean in HSs was fostered by the idea that the paradigm was particularly suitable for hospitals because its concepts are intuitive, compelling, and, therefore, easy for medical staff to use [ 18 , 19 ]. However, over time, alongside the evidence of successful implementation of lean in HSs, much of the research has shown failures in adopting the paradigm [ 5 , 20 , 21 ]. Moreover, a literature review showed that most of the cases were characterized by a partial implementation of lean methodologies and concerned single processes in the value chain or restricted technical applications [ 20 , 22 ]. Even today, few hospitals apply lean principles at a systemic level [ 23 , 24 ].

The failure of lean implementation is a hot topic. Many authors who have focused their studies on social and managerial issues have highlighted the existence of factors that either enable or hinder the implementation of lean. These factors are mostly related to the context and the implementation strategies [ 5 , 16 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. Lean implementation is not self-evident, and the process of transforming an organization into a lean organization requires a long-term strategic vision, a commitment by management, and a culture of change in the entire organization [ 5 , 16 , 26 ]. Contextual factors influence successful implementation and introduction strategy; lean adoption, in turn, changes contextual factors. A lean transformation must be planned and managed; it is not a quick solution, but a strategic plan in constant evolution [ 5 , 28 , 29 ]. From this point of view, the introduction phase plays a fundamental role in implementation because it facilitates the dissemination of the lean principle in hospitals and enables the contextual elements that support change. Although most researchers have recognized the role of the introduction step, the impact of this phase on contextual factors has been poorly reported on in the literature [ 5 , 12 , 20 ]. Most of the articles have focused more on the benefits of this phase than on how to manage it.

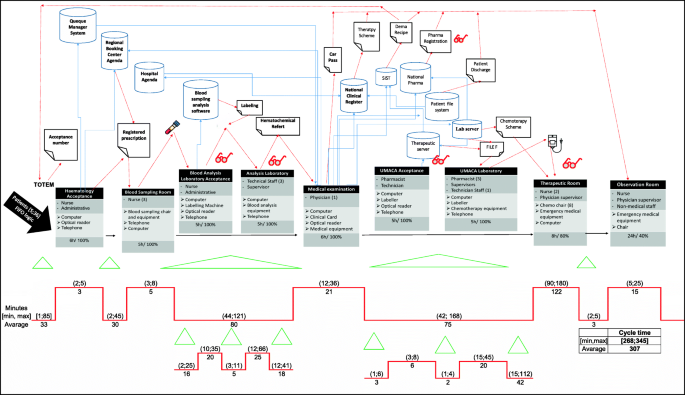

In light of this, it is necessary to examine how hospitals introduce lean into their clinical pathways in order to explain the success of the lean implementation. Starting with an in-depth analysis of the contextual factors discussed in the literature, the document helps to clarify what drives success in lean implementation within the hospital. The research has therefore undertaken a critical study of the introduction of lean in the case study of the haematology ward at a university hospital in the south of Italy. The objective is to highlight: (a) the role of contextual factors for successful lean introduction and implementation in a hospital ward; (b) how the pilot project has improved the pathway of a cancer patient undergoing chemotherapy infusion; and, (c) how the success of the pilot project modified the contextual factors, facilitating the spread of lean within the organization.

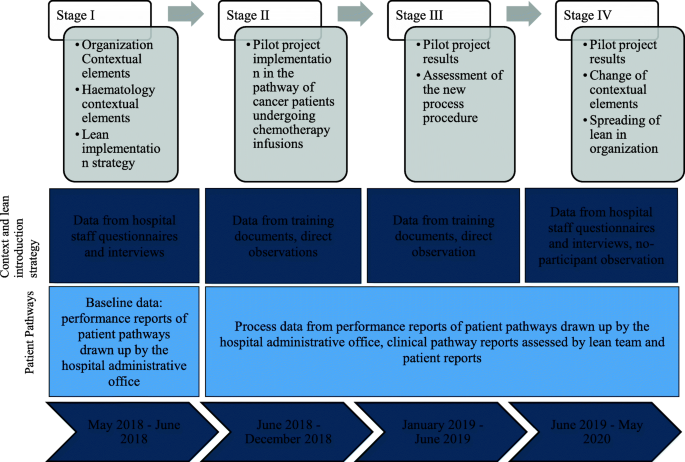

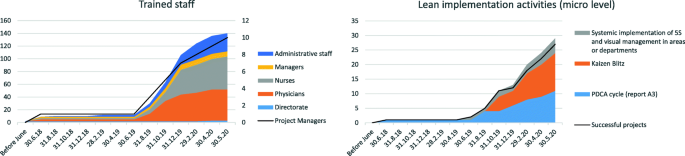

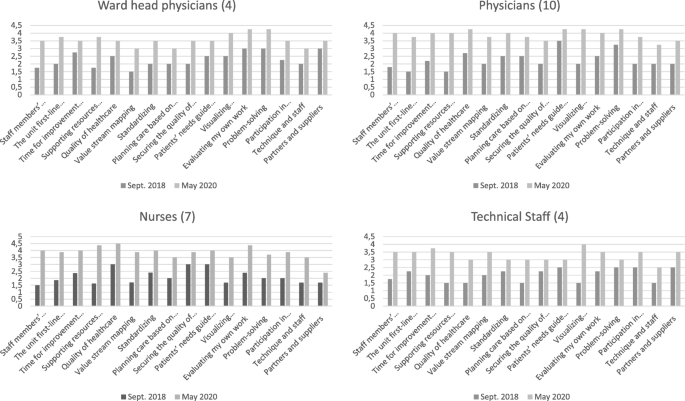

The study has the merit of detailing all the lean introduction phases. The analysis period is about 2 years. The lean introduction started in May 2018 and lasted 7 months. The pilot project results refer to the follow-up period of December 2018 to May 2020, while the dissemination results refer to the period from December 2019 to May 2020.

The paper is structured as follows: In the following section, the theoretical background is provided. Section 3 describes the research methods, while Section 4 presents the results of the pilot project. Finally, Section 5 presents the conclusion, highlights some limitations of this study, and proposes some directions for further research.

Theoretical background

Most authors point out that the introduction phase is a crucial moment in lean implementation [ 10 , 12 , 16 ]. This phase reduces distrust of the method and organizational resistance to change. It shows the benefits of lean and assesses the organization’s ability to undertake continuous improvement. Many case studies report the success of lean in HSs by describing the use of lean instruments [ 8 , 30 , 31 ]. They offer the practitioners some methodological support, but not in a structured way since they do not provide a clear implementation roadmap [ 5 , 32 , 33 ]. Some authors have tried to fill this gap in the literature by offering guidelines for implementation. Augusto and Tortorella [ 33 ] suggests carrying out a feasibility study focused on the desired performance before implementing continuous improvement activities. The author suggests defining the techniques, roles, and results related to the improvement path. Curatolo et al. [ 5 ] argue that the improvement procedure has to take into account six core operational activities of business process improvement and five support activities. The six core operational activities are: selecting projects, understanding process flows, measuring process performance, process analysis, process improvement, and implementing of lean solutions. The five support activities are: monitoring, managing change, organizing a project team, establishing top management support, and understanding the environment. These studies, while offering further guidance on the process of introducing lean into a hospital, do not describe either the organizational context in which the method is being implemented or the strategies for its implementation [ 5 , 12 , 25 ]. The introduction of lean into a HS is not an easy task; there are many organizational issues to be addressed. Among these, the analysis of the context and the definition of the implementation strategy are the ones with the greatest impact on the success of the introduction [ 16 , 26 , 34 ].

The contextual elements are the special organizational characteristics that must be considered to understand how a set of interventions may play out [ 35 , 36 ]. They interact and influence the intervention and its effectiveness [ 34 , 36 ]. Two of the most cited contextual element are the drive to improve processes and the level of maturity [ 5 , 10 ]. The drive for improvement is represented by the exogenous and endogenous needs that act as triggers for the introduction of improvement methodologies [ 25 , 26 , 35 , 37 ]. The level of maturity refers to knowledge and experience in process improvement initiatives. It includes knowledge of methodologies and tools, experience gained, confidence, trust, and dissemination within the organization. Where the maturity is low, there is a risk of lean introduction failure in both the processes and the organization as a whole [ 5 , 16 , 38 ]. As long as the organization does not reach a fair level of maturity, the rate of change tends to be slow and sometimes frustrating. However, as the degree of maturity increases, lean implementation becomes a “day-to-day job” rather than a series of projects that take place at discreet moments [ 10 , 21 , 39 ]. Hasle et al. [ 39 ] highlighted that a high level of maturity allows for the implementation of principle-driven lean. Contextual elements include organizational and technological barriers such as resistance to change, lack of motivation, skepticism, and a lack of time and resources that inhibits the introduction and the implementation process [ 4 , 8 , 21 , 40 ]. The lean introduction process in HS is also complicated by the organizational context and the double line of clinical and management authority in hospitals [ 41 , 42 ].

With regard to internal contextual factors, many authors explored the readiness and sustainability factors influencing the adoption of lean. Readiness factors are those elements that improve the chances of lean implementation success; they provide the necessary skills and knowledge to enable organizational change [ 23 , 43 , 44 , 45 ]. The readiness and sustainability factors include any practices or characteristics that allow organizational transformation by reducing or nullifying potential inhibitors of success. High commitment and strong leadership of managers and physicians, continuous training, value flow orientation, and the hospital’s involvement in continuous improvement are just some of the most discussed topics [ 5 , 10 , 16 , 43 ]. Other examples include understanding employees needs, identifying the organization’s strategic objectives, project management, and teamwork [ 5 , 12 , 16 , 46 ].

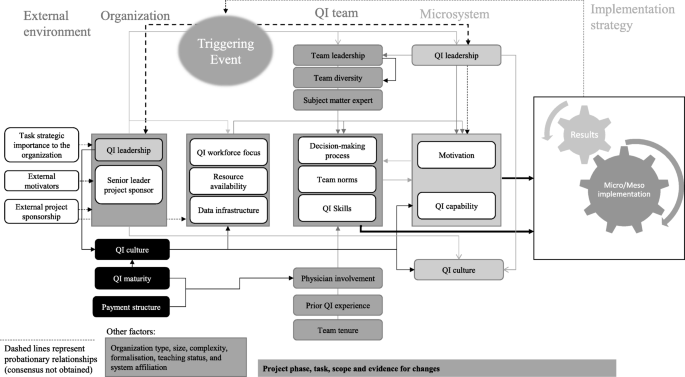

From the study of the contextual elements described so far, some authors have developed models to assess the impact of context on the implementation of organizational improvement activities. Kaplan et al. [ 36 ] put forth the Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ). The authors identified 25 key contextual factors at different organizational levels that influence the success of quality improvement efforts. They defined five domains: the microsystem, the quality improvement team, quality improvement support and capacity, organization, and the external environment. Kaplan et al. [ 36 ] suggest that an organization that disregards contextual factors is doomed to fail in implementing an improvement program; an organization that adopts a context-appropriate implementation strategy can change the outcome by triggering implementation enablers. Previous studies of lean adoption in HSs suggest that the fit between the approach taken and the circumstances will influence the chances of success [ 3 , 12 , 34 ].

There are two strategies for introducing lean in a HS, and they are characterized by the implementation level. The level of implementation refers to either micro or meso implementation. Brandao de Souza [ 16 ] defined meso-level implementation as the condition under which lean is spread throughout the organization and is implemented at the strategic level, while micro-level implementation is where lean is implemented at a single process level in discrete moments. Meso-level implementation is crucial for long-term success because a lack of integration in a lean system can lead to the achievement of local rather than global objectives and can also affect the sustainability of the paradigm [ 23 , 26 , 47 ]. However, organizations that want to implement lean at the strategic level often do not recognize the need for a long-term implementation program and introduce lean as a “big-bang initiative”. This leads in many cases to a failure to introduce the method [ 16 , 47 ]. Many researchers suggest introducing the lean approach through a pilot project run by a specially formed lean team [ 12 , 16 , 48 , 49 ]. The pilot project should be challenging, involve a process relevant to the organization, and require the use of a systemic approach. In particular, it should not be limited to the application of “pockets of good practice” or lean tools, but should include the systemic adoption of improvement programs such as the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle [ 21 , 48 ]. Brandao de Souza [ 16 ] asserts that the first initiative should be tested on a relevant patient pathway. The lean team should be composed of clinical and non-clinical staff actively involved in the patient pathway. A pilot project that meets these conditions is a useful tool for increasing the maturity of the method within the organization [ 21 , 39 ]. It can increase the confidence of the team and staff in the lean approach and can promote the learning of lean methodologies and techniques [ 21 , 39 ]. Moreover, the pilot project activates the contextual elements, enabling the introduction of the model [ 10 , 12 ]. The successes of the pilot initiative must be celebrated and communicated within the organization [ 10 ]. When the first initiative leads to visible and easily quantifiable results, the method has a greater chance of spreading throughout the organization [ 10 , 12 , 16 ]. In light of these considerations, the lean implementation requires that the contextual elements and the introduction strategy be assessed at the same time. In addition, it would seem fair to assume that as contextual factors influence the introduction strategy, the results of the implementation strategy will influence the contextual factors.

In Fig. 1 , we propose an adaptation of the MUSIQ model [ 36 ] that shows the impact that the lean implementation strategy has on the contextual elements.

Our adaptation of the MUSIQ model

Study setting and design

This is an explanatory single-case study of the introduction of lean at a university hospital in Southern Italy. In particular, the introduction of lean in the pathway of a cancer patient undergoing infusion chemotherapy in a haematology ward will be discussed. This study was designed to evaluate how the contextual elements discussed so far have influenced the introduction of the method and how the successful pilot project has enhanced the internal context. We used the adaptation of the MUSIQ model [ 36 ] proposed in Fig. 1 to systematically trace the antecedents of the lean introduction and to explain how the success of the implementation strategy changes the contextual elements.