Obesity: Personal or Public Responsibility? Essay

Empirical arguments have provided the social, cultural, economic, and health justifications that obesity is more than just an issue concerning additional weight solely. Obesity is a personal health care responsibility. This vested responsibility implies that individuals should participate proactively and beyond a reasonable doubt in safeguarding healthy living. Obesity complications are associated with the choice of food eaten, and the shaped body takes as a result. The consumers should remain protected as well as educated on dietary habits as a way of enhancing their responsibility. The variables (environmental, economic, social, and health bottom-lines) affecting dietary choices as well as physical stature are largely manipulated in public. This makes it difficult for the majority to maintain an individual balance (based on these variables), particularly when prone to obesity complications. Based on a cost-benefit perspective and wide-scale impact assessment, a personalized approach will instill individual dietary discipline, while cushioning a shock from health risks involved. The public responsibility approach may be prone to finger-pointing or shifting blame, unnecessarily.

This means that due diligence should apply to avoid infringing the right to choice (and diversity) for the non-obese as well as to deny manufacturers the right to competitive bidding for a larger market share. Even if weight is gained due to eating fast foods at fast food retailers, an individual has the responsibility to control weight gaining (through fitness programs, for example) as well as understand their hereditary background which is linked to obesity problems. Before claiming a public agent, such as fast food retailer, to be responsible for the cause of obesity, hereditary or lack of fitness activities should be taken into account, and a preventive paradigm should substitute a damage control one. This negates the precautionary principle held by the due diligence concept. Public responsibility makes the food producer or manufacturer vulnerable to court cases and judicial decisions. The concept of demand-supply proves that personal responsibility referred to the customer demand for fast foods is the main power that forces the supplier to meet customer needs and requirements.

From a social and cultural perspective, legal action should focus on the individual right to choose as well as public education. Manufactured foods and fast food have wide market access across the world. Food manufacturers should legally be obliged to product labeling and explanation (duty to warn) to enhance consumer safety and awareness of the health risks involved. Obesity thrives against the backdrop of disparities in health care access and affordability. Moreover, there is a trend of a wealthy consumer lifestyle, which includes aggressive advertising that entices fast food addiction and market flooding of processed foods. These factors aggravate the proneness to obesity within a global society.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, February 13). Obesity: Personal or Public Responsibility? https://ivypanda.com/essays/obesity-personal-or-public-responsibility/

"Obesity: Personal or Public Responsibility?" IvyPanda , 13 Feb. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/obesity-personal-or-public-responsibility/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Obesity: Personal or Public Responsibility'. 13 February.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Obesity: Personal or Public Responsibility?" February 13, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/obesity-personal-or-public-responsibility/.

1. IvyPanda . "Obesity: Personal or Public Responsibility?" February 13, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/obesity-personal-or-public-responsibility/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Obesity: Personal or Public Responsibility?" February 13, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/obesity-personal-or-public-responsibility/.

- Coffee Demand & Supply in the United Arab Emirates

- AT&T Inc.'s Products, Demand & Supply, and Market

- Effects of Obesity on Neuroendocrine, and Immune Cell Responses to Stress

- International Environmental Law: Precautionary Principle

- The role of the state in defending and/or infringing Native Indian Civil Rights in United States

- Childhood Obesity and Cold Virus

- Elevator Pitch for Kernel Keto Company

- Communicable Diseases and Precautionary Measures

- Equations for Predicting Resting Energy Expenditure

- Precautionary Principle in Environmental Situations

- Encultured Eating Course: Nine Weeks of Experience

- Humans Are Herbivores: Arguments For and Against

- Problem of Food Overconsumption

- Childhood Obesity and Food Culture in Schools

- "Quit Meat" Vegetarian Diet: Pros and Cons

Prevention, prevention, prevention.

Losing weight is hard to do.

In the U.S., only one in six adults who have dropped excess pounds actually keep off at least 10 percent of their original body weight. The reason: a mismatch between biology and environment. Our bodies are evolutionarily programmed to put on fat to ride out famine and preserve the excess by slowing metabolism and, more important, provoking hunger. People who have slimmed down and then regain their weight don’t lack willpower—their bodies are fighting them every inch of the way.

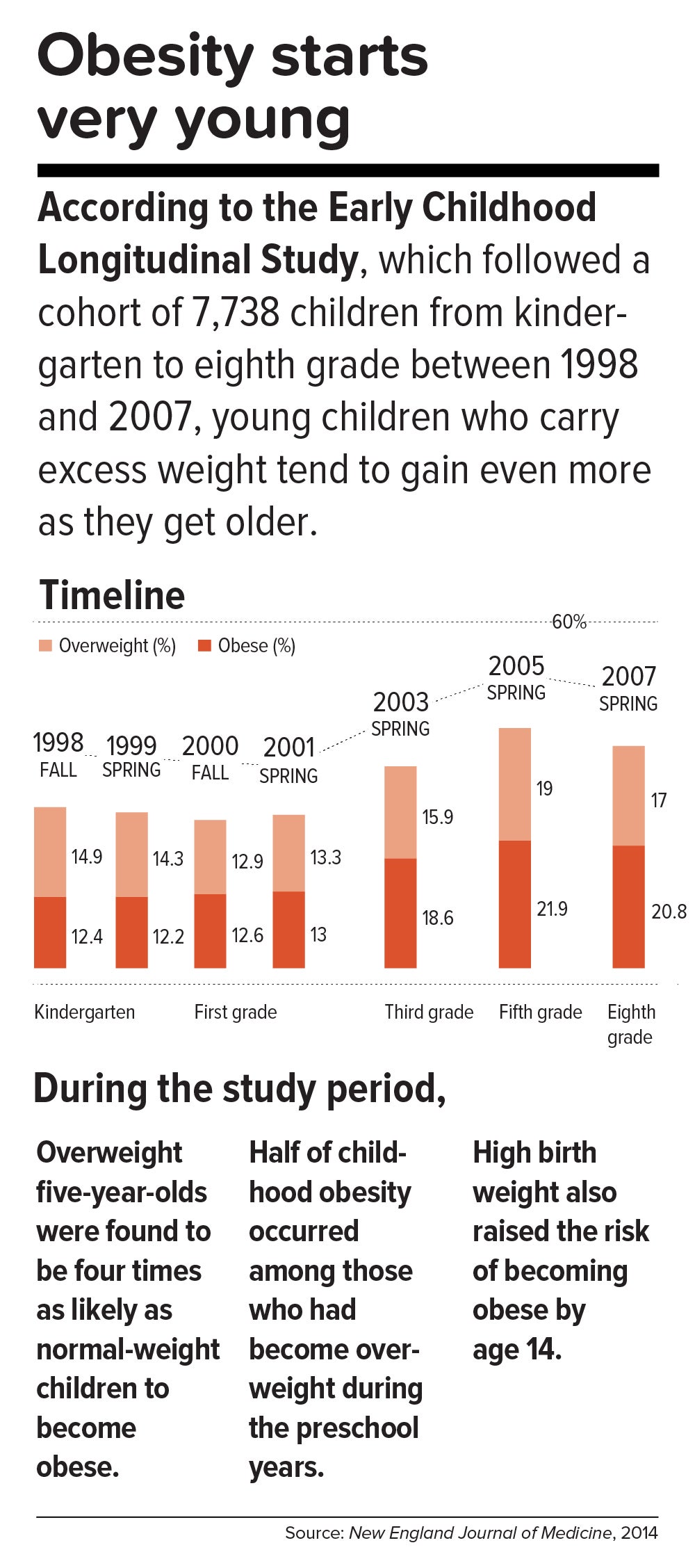

This inborn predisposition to hold on to added weight reverberates down the life course. Few children are born obese, but once they become heavy, they are usually destined to be heavy adolescents and heavy adults. According to a 2016 study in the New England Journal of Medicine , approximately 90 percent of children with severe obesity will become obese adults with a BMI of 35 or higher. Heavy young adults are generally heavy in middle and old age. Obesity also jumps across generations; having a mother who is obese is one of the strongest predictors of obesity in children.

All of which means that preventing child obesity is key to stopping the epidemic. By the time weight piles up in adulthood, it is usually too late. Luckily, preventing obesity in children is easier than in adults, partly because the excess calories they absorb are minimal and can be adjusted by small changes in diet—substituting water, for example, for sugary fruit juices or soda.

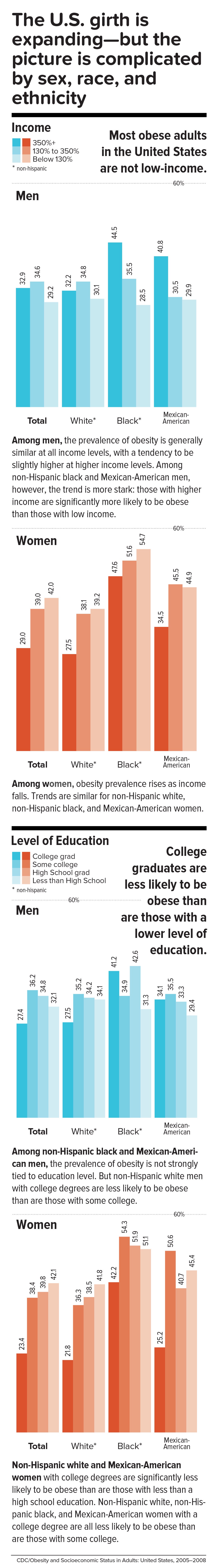

Still, the bulk of the obesity problem—literally—is in adults. According to Frank Hu, chair of the Harvard Chan Department of Nutrition, “Most people gain weight during young and middle adulthood. The weight-gain trajectory is less than 1 pound per year, but it creeps up steadily from age 18 to age 55. During this time, people gain fat mass, not muscle mass. When they reach age 55 or so, they begin to lose their existing muscle mass and gain even more fat mass. That’s when all the metabolic problems appear: insulin resistance, high cholesterol, high blood pressure.”

Adds Walter Willett, Frederick John Stare Professor of Epidemiology and Nutrition at Harvard Chan, “The first 5 pounds of weight gain at age 25—that’s the time to be taking action. Because someone is on a trajectory to end up being 30 pounds overweight by the time they’re age 50.”

The most realistic near-term public health goal, therefore, is not to reverse but rather to slow down the trend—and even this will require strong commitment from government at many levels. In May 2017, the Trump administration rolled back recently-enacted standards for school meals, delaying a rule to lower sodium and allowing waivers for regulations requiring cafeterias to serve foods rich in whole grains. If recent expansions in food entitlements and school meals are undermined, “It would be a ‘disaster,’ to use the president’s word,” says Marlene Schwartz, director of the Rudd Center for Obesity & Food Policy at the University of Connecticut. “The federal food programs are incredibly important, not just because of the food and money they provide families, but because supporting better nutrition in child care, schools, and the WIC [Women, Infants, and Children] program has created new social norms. We absolutely cannot undo the progress that we’ve made in helping this generation transition to a healthier diet.”

Get the science right.

It is impossible to prescribe solutions to obesity without reminding ourselves that nutrition scientists botched things decades ago and probably sent the epidemic into overdrive. Beginning in the 1970s, the U.S. government and major professional groups recommended for the first time that people eat a low-fat/high-carbohydrate diet. The advice was codified in 1977 with the first edition of The Dietary Goals for the United States , which aimed to cut diet-related conditions such as heart disease and diabetes. What ensued amounted to arguably the biggest public health experiment in U.S. history, and it backfired.

At the time, saturated fat and dietary cholesterol were believed to be the main factors responsible for cardiovascular disease—an oversimplified theory that ignored the fact that not all fats are created equal. Soon, the public health blitz against saturated fat became a war on all fat. In the American diet, fat calories plummeted and carb calories shot up.

“We can’t blame industry for this. It was a bandwagon effect in the scientific community, despite the lack of evidence—even with evidence to the contrary,” says Willett. “Farmers have known for thousands of years that if you put animals in a pen, don’t let them run around, and load them up with grains, they get fat. That’s basically what has been happening to people: We created the great American feedlot. And we added in sugar, coloring, and seductive promotion for low-fat junk food.”

Scientists now know that whole fruits and vegetables (other than potatoes), whole grains, high-quality proteins (such as from fish, chicken, beans, and nuts), and healthy plant oils (such as olive, peanut, or canola oil) are the foundations of a healthy diet.

But there is also a lot scientists don’t yet know. One unanswered question is why some people with obesity are spared the medical complications of excess weight. Another concerns the major mechanisms by which obesity ushers in disease. Although surplus body weight can itself directly cause problems—such as arthritis due to added load on joints, or breast cancer caused by hormones secreted by fat cells—in general, obesity triggers myriad biological processes. Many of the resulting conditions—such as atherosclerosis, diabetes, and even Alzheimer’s disease—are mediated by inflammation, in which the body’s immune response becomes damagingly self-perpetuating. In this sense, today’s food system is as inflammagenic as it is obesigenic.

Scientists also need to ferret out the nuanced effects of particular foods. For example, do fermented products—such as yogurt, tempeh, or sauerkraut—have beneficial properties? Some studies have found that yogurt protects against weight gain and diabetes, and suggest that healthy live bacteria (known as probiotics) may play a role. Other reports point to fruits being more protective than vegetables in weight control and diabetes prevention, although the types of fruits and vegetables make a difference.

A 2017 article in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition showed that substituting whole grains for refined grains led to a loss of nearly 100 calories a day—by speeding up metabolism, cutting the number of calories that the body hangs on to, and, more surprisingly, by changing the digestibility of other foods on the plate. That extra energy lost daily—by substituting, say, brown rice for white rice or barley for pita bread—was equivalent to a brisk 30-minute walk. One hundred calories a day, sustained over years, and multiplied by the population is one mathematical equivalent of the obesity epidemic.

A companion study found that adults who ate a whole-grain-rich diet developed healthier gut bacteria and improved immune responses. That particular foods alter the gut microbiome—the dense and vital community of bacteria and other microorganisms that work symbiotically with the body’s own digestive system—is another critical insight. The microbiome helps determine weight by controlling how our bodies extract calories and store fat in the liver, and the microbiomes of obese individuals are startlingly efficient at harvesting calories from food. [To learn more about Harvard Chan research on the gut microbiome, read “ Bugs in the System .”] The hormonal effects of sleep deprivation and stress—two epidemics concurrent and intertwined with the obesity trend—are other promising avenues of research.

And then there are the mystery factors. One recent hypothesis is that an agent known as adenovirus 36 partly accounts for our collective heft. A 2010 article in The Royal Society described a study in which researchers examined samples of more than 20,000 animals from eight species living with or around humans in industrialized nations, a menagerie that included macaques, chimpanzees, vervets, marmosets, lab mice and rats, feral rats, and domestic dogs and cats. Like their Homo sapiens counterparts, all of the study populations had gained weight over the past several decades—wild, domestic, and lab animals alike. The chance that this is a coincidence is, according to the scientists’ estimate, 1 in 10 million. The stumped authors surmise that viruses, gene expression changes, or “as-of-yet unidentified and/or poorly understood factors” are to blame.

Master the art of persuasion.

A 2015 paper in the American Journal of Public Health revealed the philosophical chasm that hampers America’s progress on obesity prevention. It found that 72 to 98 percent of obesity-related media reports emphasize personal responsibility for weight, compared with 40 percent of scientific papers.

A recent study by Drexel University researchers also quantified the political polarization around public health measures. From 1998 through 2013, Democrats voted in line with recommendations from the American Public Health Association 88.3 percent of the time, on average, while Republicans voted for the proposals just 21.3 percent of the time.

Clearly, we can’t count on bipartisan goodwill to stem the obesity crisis. But we can ask what kinds of messages appeal to politically divergent audiences. A stealth strategy may be to avoid even uttering the word “obesity.” On January 1 of this year, Philadelphia’s 1.5-cents-per-ounce excise tax on sugar-sweetened and diet beverages took effect. When Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney lobbied voters to approve the tax, his bid centered not on improving health—the unsuccessful pitch of his predecessor—but on raising $91 million annually for prekindergarten programs.

“That’s something lots of people care about and can get behind—it’s a feel-good policy, and it makes sense,” says psychologist Christina Roberto, assistant professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania, and a former assistant professor of social and behavioral sciences and nutrition at Harvard Chan. The provision for taxing diet beverages was also shrewd, she adds, because it spread the tax’s pain; since wealthier people are more likely than less-affluent individuals to buy diet drinks, the tax could not be slapped with the label “regressive.”

But Roberto sees a larger lesson in the Philadelphia story. Public health messaging that appeals to values that transcend the individual is less fraught, less stigmatizing, and perhaps more effective. As she puts it, “It’s very different to hear the message, ‘Eat less red meat, help the planet’ versus ‘Eat less red meat, help yourself avoid saturated fat and cardiovascular disease.’”

Supermarket makeovers

Supermarket aisles are other places where public health can shuffle a deck stacked against healthy consumer choices.

With slim profit margins and 50,000-plus products on their shelves, grocery stores depend heavily on food manufacturers’ promotional incentives to make their bottom lines. “Manufacturers pay slotting fees to get their products on the shelf, and they pay promotion allowances: We’ll give you this much off a carton of Coke if you put it on sale for a certain price or if you put it on an end-of-aisle display,” says José Alvarez, former president and chief executive officer of Stop & Shop/Giant-Landover, now senior lecturer of business administration at Harvard Business School. Such promotional payments, Alvarez adds, often exceed retailers’ net profits.

Healthy new products—like flash-frozen dinners prepared with heaps of vegetables and whole grains, and relatively little salt—can’t compete for prized shelf space against boxed mac and cheese or cloying breakfast cereals. One solution, says Alvarez, is for established consumer packaged goods companies to buy out what he calls the “hippie in the basement” firms that have whipped up more nutritious items. The behemoths could apply their production, marketing, and distribution prowess to the new offerings—and indeed, this has started to happen over the last five years.

Another approach is to make nutritious foods more convenient to eat. “We have all of these cooking shows and upscale food magazines, but most people don’t have the time or inclination—or the skills, quite frankly—to cook,” says Alvarez. “Instead, we should focus on creating high-quality, healthy, affordable prepared foods.”

An additional model is suggested by Jeff Dunn, a 20-year veteran of the soft drink industry and former president of Coca-Cola North America, who went on to become an advocate for fresh, healthy food. Dunn served as president and chief executive officer of Bolthouse Farms from 2008 to 2015, where he dramatically increased sales of baby carrots by using marketing techniques common in the junk food business. “We operated on the principles of the three 3 A’s: accessibility, availability, and affordability,” says Dunn. “That, by the way, is Coke’s more-than-70-year-old formula for success.”

Show them the money.

Obesity kills budgets. According to the Campaign to End Obesity, a collaboration of leaders from industry, academia, public health, and policymakers, annual U.S. health costs related to obesity approach $200 billion. In 2010, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office reported that nearly 20 percent of the rise in health care spending from 1987 to 2007 was linked to obesity. And the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that full-time workers in the U.S. who are overweight or obese and have other chronic health conditions miss an estimated 450 million more days of work each year than do healthy employees—upward of $153 billion in lost productivity annually.

But making the money case for obesity prevention isn’t straightforward. For interventions targeting children and youth, only a small fraction of savings is captured in the first decade, since most serious health complications don’t emerge for many years. Long-term obesity prevention, in other words, doesn’t fit into political timetables for elected officials.

Yet lawmakers are keen to know how “best for the money” obesity-prevention programs can help them in the short run. Over the past two years, Harvard Chan’s Steve Gortmaker and his colleagues have been working with state health departments in Alaska, Mississippi, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Washington, and West Virginia and with the city of Philadelphia and other locales, building cost-effectiveness models using local data for a wide variety of interventions—from improved early child care to healthy school environments to communitywide campaigns. “We collaborate with health departments and community stakeholders, provide them with the evidence base, help assess how much different options cost, model the results over a decade, and they pick what they want to work on. One constant that we’ve seen—and these are very different political environments—is a strong interest in cost-effectiveness,” he says.

In a 2015 study in Health Affairs , Gortmaker and colleagues outlined three interventions that would more than pay for themselves: an excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages implemented at the state level; elimination of the tax subsidy for advertising unhealthy food to children; and strong nutrition standards for food and drinks sold in schools outside of school meals. Implemented nationally, these interventions would prevent 576,000, 129,100, and 345,000 cases of childhood obesity, respectively, by 2025. The projected net savings to society in obesity-related health care costs for each dollar invested: $31, $33, and $4.60, respectively.

Gortmaker is one of the leaders of a collaborative modeling effort known as CHOICES—for Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study—an acronym that seems a pointed rebuttal to the reflexive conservative argument that government regulation tramples individual choice. Having grown up not far from Des Plaines, Illinois, site of the first McDonald’s franchise in the country, he emphasizes to policymakers that at this late date, America cannot treat its way out of obesity, given current medical know-how. Only a thoroughgoing investment in prevention will turn the tide. “Clinical interventions produce too small an effect, with too small a population, and at high cost,” Gortmaker says. “The good news is that there are many cost-effective options to choose from.”

While Gortmaker underscores the importance of improving both food choices and options for physical activity, he has shown that upgrading the food environment offers much more benefit for the buck. This is in line with the gathering scientific consensus that what we eat plays a greater role in obesity than does sedentary lifestyle (although exercise protects against many of the metabolic consequences of excess weight). “The easiest way to explain it,” Gortmaker says, “is to talk about a sugary beverage—140 calories. You could quickly change a kid’s risk of excess energy balance by 140 calories a day just by switching from a sugary drink a day to water or sparkling water. But for a 10-year-old boy to burn an extra 140 calories, he’d have to replace an hour-and-a-half of sitting with an hour-and-a-half of walking.”

Small tweaks in adults’ diets can likewise make a big difference in short order. “With adults, health care costs rise rapidly with excess weight gain,” Gortmaker says. “If you can slow the onset of obesity, you slow the onset of diabetes, and potentially not only save health care costs but also boost people’s productivity in the workforce.”

One of Gortmaker’s most intriguing calculations spins off of the food industry’s estimated $633 million spent on television marketing aimed at kids. Currently, federal tax treatment of advertising as an ordinary business expense means that the government, in effect, subsidizes hawking of junk food to children. Gortmaker modeled a national intervention that would eliminate this subsidy of TV ads for nutritionally empty foods and beverages aimed at 2- to 19-year-olds. Drawing on well-delineated relationships between exposure to these advertisements and subsequent weight gain, he found that the intervention would save $260 million in downstream health care costs. Although the effect would probably be small at the individual level, it would be significant at the population level.

Level the playing field through taxes and regulation.

When public health took on cigarette smoking, starting in the 1960s, it did so with robust policies banning television ads and other marketing, raising taxes to increase prices, making public places smoke-free, and offering people treatment such as the nicotine patch. In 1965, the smoking rate for U.S. adults was 42.2 percent; today, it is 16.8 percent.

Similarly, America reduced the rate of deaths caused by motor vehicle accidents—a 90 percent decrease over the 20th century, according to the CDC—with mandatory seat belt laws, safer car designs, stop signs, speed limits, rumble strips, and the stigmatization of drunk driving.

Change the product. Change the environment. Change the culture. That is also the policy recipe for stopping obesity.

Laws that make healthy behaviors easier are often followed by positive changes in those behaviors. And people who are trying to adopt healthy behaviors tend to support policies that make their personal aspirations achievable, which in turn nudges lawmakers to back the proposals.

One debate today revolves around whether recipients of federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits (formerly known as food stamps) should be restricted from buying sodas or junk food. The largest component of the USDA budget, SNAP feeds one in seven Americans. A USDA report, issued last November, found that the number-one purchase by SNAP households was sweetened beverages, a category that included soft drinks, fruit juices, energy drinks, and sweetened teas, accounting for nearly 10 percent of SNAP money spent on food. Is the USDA therefore underwriting the soda industry and planting the seeds for chronic disease that the government will pay to treat years down the line?

Eric Rimm, a professor in the Departments of Epidemiology and Nutrition at the Harvard Chan School, frames the issue differently. In a 2017 study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine , he and his colleagues asked SNAP participants whether they would prefer the standard benefits package or a “SNAP-plus” that prohibited the purchase of sugary beverages but offered 50 percent more money for buying fruits and vegetables. Sixty-eight percent of the participants chose the healthy SNAP-plus option.

“A lot of work around SNAP policy is done by academics and politicians, without reaching out to the beneficiaries,” says Rimm. “We haven’t asked participants, ‘What’s your say in this? How can we make this program better for you?’” To be sure, SNAP is riddled with nutritional contradictions. Under current rules, for example, participants can use benefits to buy a 12-pack of Pepsi or a Snickers bar or a giant bag of Lay’s potato chips but not real food that happens to be heated, such as a package of rotisserie chicken. “This is the most vulnerable population in the country,” says Rimm. “We’re not listening well enough to our constituency.”

Other innovative fiscal levers to alter behavior could also drive down obesity. In 2014, a trio of strong voices on food industry practices—Dariush Mozaffarian, DrPH ’06, dean of Tufts University’s Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy and former associate professor of epidemiology at the Harvard Chan School; Kenneth Rogoff, professor of economics at Harvard; and David Ludwig, professor in the Department of Nutrition at Harvard Chan and a physician at Boston Children’s Hospital—broached the idea of a “meaningful” tax on nearly all packaged retail foods and many chain restaurants, with the proceeds used to pay for minimally processed foods and healthier meals for school kids. In essence, the tax externalizes the social costs of harmful individual behavior.

“We made a straightforward proposal to tax all processed foods and then use the income to subsidize whole foods in a short-term, revenue-neutral way,” explains Ludwig. “The power of this idea is that, since there is so much processed food consumption, even a modest tax—in the 10 to 15 percent range—is not going to greatly inflate the cost of these foods. Their price would increase moderately, but the proceeds would not disappear into government coffers. Instead, the revenue would make healthy foods affordable for virtually the entire population, and the benefits would be immediately evident. Yes, people will pay moderately more for their Coke or for their cinnamon bear claw but a lot less for nourishing, whole foods.”

Another suggestion comes from Sandro Galea, dean of the Boston University School of Public Health, and Abdulrahman M. El-Sayed, a public health physician and epidemiologist. In a 2015 issue of the American Journal of Public Health , they called for “calorie offsets,” similar to the carbon offsets used to mitigate environmental harm caused by the gas and oil industries. A “calorie offset” scheme could hand the food and beverage industries a chance at redemption by inviting them to invest in such undertakings as city farms, cooking classes for parents, healthy school cafeterias, and urban green spaces.

These ambitious proposals face almost impossibly high hurdles. Political battle lines typically pit public health against corporations, with Big Food casting doubt on solid nutrition science, deeming government regulation a threat to free choice, and making self-policing pledges that it has never kept. On the website for the Americans for Food and Beverage Choice, a group spearheaded by the American Beverage Association, is the admonition: “[W]hether it’s at a restaurant or in a grocery store, it’s never the government’s job to decide what you choose to eat and drink.”

Yet surprisingly, many public health professionals are convinced that the only way to stop obesity is to make common cause with the food industry. “This isn’t like tobacco, where it’s a fight to the death. We need the food industry to make healthier food and to make a profit,” says Mozaffarian. “The food industry is much more diverse and heterogeneous than tobacco or even cars. As long as we can help them—through carrots and sticks, tax incentives and disincentives—to move towards healthier products, then they are part of the solution. But we have to be vigilant, because they use a lot of the same tactics that tobacco did.”

Sow what we want to reap.

Americans overeat what our farmers overproduce.

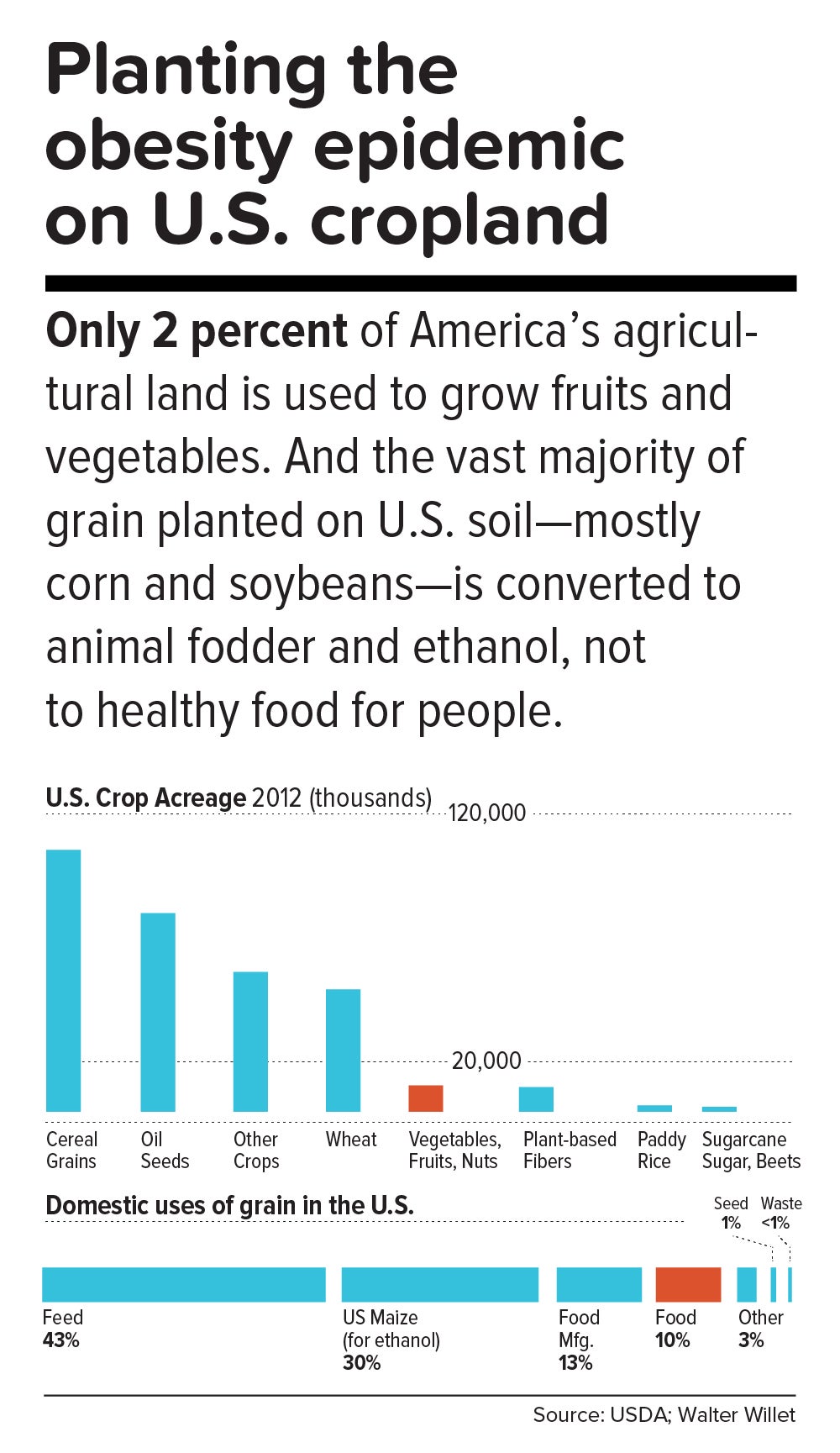

“The U.S. food system is egregiously terrible for human and planetary health,” says Walter Willett. It’s so terrible, Willett made a pie chart of American grain production consumed domestically. It shows that most of the country’s agricultural land goes to the two giant commodity crops: corn and soy. Most of those crops, in turn, go to animal fodder and ethanol, and are also heavily used in processed snack foods. Today, only about 10 percent of grain grown in the U.S. for domestic use is eaten directly by human beings. According to a 2013 report from the Union of Concerned Scientists, only 2 percent of U.S. farmland is used to grow fruits and vegetables, while 59 percent is devoted to commodity crops.

Historically, those skewed proportions made sense. Federal food policies, drafted with the goal of alleviating hunger, preferentially subsidize corn and soy production. And whereas corn or soybeans could be shipped for days on a train, fruits and vegetables had to be grown closer to cities by truck farmers so the produce wouldn’t spoil. But those long-ago constraints don’t explain today’s upside-down agricultural priorities.

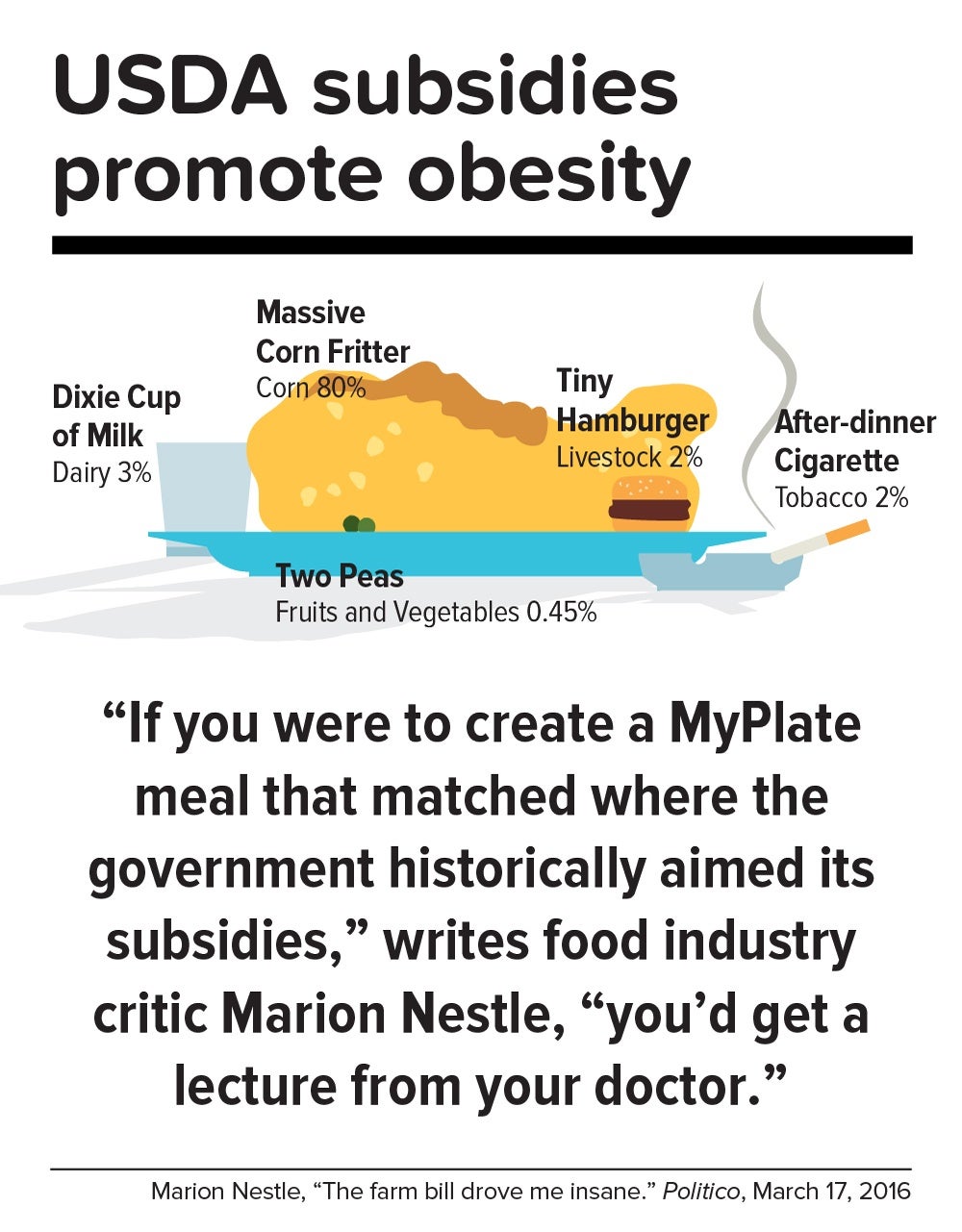

In a now-classic 2016 Politico article titled “The farm bill drove me insane,” Marion Nestle illustrated the irrational gap between what the government recommends we eat and what it subsidizes: “If you were to create a MyPlate meal that matched where the government historically aimed its subsidies, you’d get a lecture from your doctor. More than three-quarters of your plate would be taken up by a massive corn fritter (80 percent of benefits go to corn, grains and soy oil). You’d have a Dixie cup of milk (dairy gets 3 percent), a hamburger the size of a half dollar (livestock: 2 percent), two peas (fruits and vegetables: 0.45 percent) and an after-dinner cigarette (tobacco: 2 percent). Oh, and a really big linen napkin (cotton: 13 percent) to dab your lips.”

In this sense, the USDA marginalizes human health. Many of the foods that nutritionists agree are best for us—notably, fruits, vegetables, and tree nuts—fall under the bureaucratic rubric “specialty crops,” a category that also includes “dried fruits, horticulture, and nursery crops (including floriculture).” Farm bills, which get passed every five years or so, fortify the status quo. The 2014 Farm Bill, for example, provided $73 million for the Specialty Crop Block Grant Program in 2017, out of a total of about $25 billion for the USDA’s discretionary budget. (The next Farm Bill, now under debate, will be coming out in 2018.)

By contrast, a truly anti-obesigenic agricultural system would stimulate USDA support for crop diversity—through technical assistance, research, agricultural training programs, and financial aid for farmers who are newly planting or transitioning their land into produce. It would also enable farmers, most of whom survive on razor-thin profit margins, to make a decent living.

In the early 1970s, Finland’s death rate from coronary heart disease was the highest in the world, and in the eastern region of North Karelia—a pristine, sparsely populated frontier landscape of forest and lakes—the rate was 40 percent worse than the national average. Every family saw physically active men, loggers and farmers who were strong and lean, dying in their prime.

Thus was born the North Karelia Project, which became a model worldwide for saving lives by transforming lifestyles. The project was launched in 1972 and officially ended 25 years later. While its initial goal was to reduce smoking and saturated fat in the diet, it later resolved to increase fruit and vegetable consumption.

The North Karelia Project fulfilled all of these ambitions. When it started, for example, 86 percent of men and 82 percent of women smeared butter on their bread; by the early 2000s, only 10 percent of men and 4 percent of women so indulged. Use of vegetable oil for cooking jumped from virtually zero in 1970 to 50 percent in 2009. Fruit and vegetables, once rare visitors to the dinner plate, became regulars. Over the project’s official quarter-century existence, coronary heart disease deaths in working-age North Karelian men fell 82 percent, and life expectancy rose seven years.

The secret of North Karelia’s success was an all-out philosophy. Team members spent innumerable hours meeting with residents and assuring them that they had the power to improve their own health. The volunteers enlisted the assistance of an influential women’s group, farmers’ unions, homemakers’ organizations, hunting clubs, and church congregations. They redesigned food labels and upgraded health services. Towns competed in cholesterol-cutting contests. The national government passed sweeping legislation (including a total ban on tobacco advertising). Dairy subsidies were thrown out. Farmers were given strong incentives to produce low-fat milk, or to get paid for meat and dairy products based not on high-fat but on high-protein content. And the newly established East Finland Berry and Vegetable Project helped locals switch from dairy farming—which had made up more than two-thirds of agriculture in the region—to cultivation of cold-hardy currants, gooseberries, and strawberries, as well as rapeseed for heart-healthy canola oil.

“A mass epidemic calls for mass action,” says the project’s director, Pekka Puska, “and the changing of lifestyles can only succeed through community action. In this case, the people pulled the government—the government didn’t pull the people.”

Could the United States in 2017 learn from North Karelia’s 1970s grand experiment?

“Americans didn’t become an obese nation overnight. It took a long time—several decades, the same timeline as in individuals,” notes Frank Hu. “What were we doing over the past 20 years or 30 years, before we crossed this threshold? We haven’t asked these questions. We haven’t done this kind of soul-searching, as individuals or society as a whole.”

Today, Americans may finally be willing to take a hard look at how food figures in their lives. In a July 2015 Gallup phone poll of Americans 18 and older, 61 percent said they actively try to avoid regular soda (the figure was 41 percent in 2002); 50 percent try to avoid sugar; and 93 percent try to eat vegetables (but only 57.7 percent in 2013 reported they ate five or more servings of fruits and vegetables at least four days of the previous week).

Individual resolve, of course, counts for little in problems as big as the obesity epidemic. Most successes in public health bank on collective action to support personal responsibility while fighting discrimination against an epidemic’s victims. [To learn more about the perils of stigma against people with obesity, read “ The Scarlet F .”]

Yet many of public health’s legendary successes also took what seems like an agonizingly long time to work. Do we have that luxury?

“Right now, healthy eating in America is like swimming upstream. If you are a strong swimmer and in good shape, you can swim for a little while, but eventually you’re going to get tired and start floating back down,” says Margo Wootan, SD ’93, director of nutrition policy for the Center for Science in the Public Interest. “If you’re distracted for a second—your kid tugs on your pant leg, you had a bad day, you’re tired, you’re worried about paying your bills—the default options push you toward eating too much of the wrong kinds of food.”

But Wootan has not lowered her sights. “What we need is mobilization,” she says. “Mobilize the public to address nutrition and obesity as societal problems—recognizing that each of us makes individual choices throughout the day, but that right now the environment is stacked against us. If we don’t change that, stopping obesity will be impossible.”

The passing of power to younger generations may aid the cause. Millennials are more inclined to view food not merely as nutrition but also as narrative—a trend that leaves Duke University’s Kelly Brownell optimistic. “Younger people have been raised to care about the story of their food. Their interest is in where it came from, who grew it, whether it contributes to sustainable agriculture, its carbon footprint, and other factors. The previous generation paid attention to narrower issues, such as hunger or obesity. The Millennials are attuned to the concept of food systems.”

We are at a public health inflection point. Forty years from now, when we gaze at the high-resolution digital color photos from our own era, what will we think? Will we realize that we failed to address the obesity epidemic, or will we know that we acted wisely?

The question brings us back to the 1970s, and to Pekka Puska, the physician who directed the North Karelia Project during its quarter-century existence. Puska, now 71, was all of 27 and burning with big ideas when he signed up to lead the audacious effort. He knows the promise and the perils of idealism. “Changing the world may have been utopic,” he says, “but changing public health was possible.”

News from the School

From public servant to public health student

Exploring the intersection of health, mindfulness, and climate change

Conference aims to help experts foster health equity

Building solidarity to face global injustice

The Role of Personal Responsibility in the Obesity Epidemic

How the power of the “eat more” food environment can overcome our conscious controls.

Below is an approximation of this video’s audio content. To see any graphs, charts, graphics, images, and quotes to which Dr. Greger may be referring, watch the above video.

Food and beverage companies frame body weight as a matter of personal choice. Even when we’re not distracted, the power of the “eat more” food environment may sometimes overcome our conscious controls over eating. One look around the room at a dietician convention can tell you that even nutrition professionals are vulnerable to the aggressively marketed ubiquity of tasty, cheap, convenient calories. This suggests there are aspects of our eating behaviors that defy personal insight by flying below the radar of conscious awareness. Appetite physiologists call the result of these subconscious actions “passive overconsumption.”

Remember that brain scan study where the thought of a milkshake lit up the same reward pathways in the brain as substance abuse? That was triggered just by a picture of a milkshake. Dopamine gets released, cravings get activated, and we’re motivated to eat. Intellectually, we know it’s just an image, but our lizard brain just sees survival. It’s just a reflexive response over which we have little control––which is why marketers ensure there are pictures of milkshakes and their equivalents everywhere.

Maintaining a balance between calories in and calories out feels like a series of voluntary acts under conscious control, but it may be more akin to bodily functions such as blinking, breathing, coughing, swallowing, or sleeping. You can try to will yourself power over any of these, but by and large, they just happen automatically, driven by ancient scripts.

Not only are food ads ubiquitous; so is the food. The types of establishments selling food products expanded dramatically in the 1970s and 1980s. Now there’s candy and snacks at the checkout counters of gas stations, drug stores, bookstores, and places that used to just sell clothes, hardware, home furnishings, or building supplies. The largest food retailer in the United States is Walmart. There’s that jolt of dopamine, and the artificially-stimulated feelings of hunger around every turn. Every day we run the gauntlet.

And it’s become socially acceptable to eat anywhere—in your car, on the street, or packed in a crowded bus. We’ve become a snacking society. Vending machines are everywhere. Daily eating episodes seem to have gone up by about a quarter since the late 1970s––increasing from about four to five occasions a day, potentially accounting for twice the calorie increase attributed to increasing portion sizes. Snacks and beverages alone could account for the bulk of the calorie surplus implicated in the obesity epidemic.

And think of the children. Here we are trying to do the best for our kids, role-modeling healthy habits, feeding them healthy foods, but then they venture out into a veritable tornado of junky food and manipulative messages. This commentary in the New England Journal of Medicine asked why should our efforts to protect our children from life-threatening illness be undermined by massive marketing campaigns from the manufacturers of junk food. Pediatricians are now encouraged to have the “french fry discussion” with parents at the 12-month well-child visit and not wait all the way until year two. And even that may be too late. Two-thirds of infants are being fed junk food by their first birthday.

Dr. David Katz may have said it best in the Harvard Health Policy Review : “Those who contend that parental or personal responsibility should carry the day despite these environmental temptations might consider the implications of generalizing the principle. Perhaps children should be encouraged, but not required, to attend school, and tempted each morning by alternatives, such as buses to the circus, zoo, or beach.”

Please consider volunteering to help out on the site.

- Nestle M. Utopian dream: a new farm bill. Dissent. 2012;59(2):15-9.

- Cohen DA. Neurophysiological pathways to obesity: below awareness and beyond individual control. Diabetes. 2008;57(7):1768-73.

- Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):804-14.

- Gearhardt AN, Yokum S, Orr PT, Stice E, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Neural correlates of food addiction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(8):808-16.

- Zimmerman FJ. Using marketing muscle to sell fat: the rise of obesity in the modern economy. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:285-306.

- Taillie LS, Ng SW, Popkin BM. Global growth of “big box” stores and the potential impact on human health and nutrition. Nutr Rev. 2016;74(2):83-97.

- Nestle M. Counting the cost of calories. Interview by Ben Jones. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(8):566-7.

- Duffey KJ, Popkin BM. Energy density, portion size, and eating occasions: contributions to increased energy intake in the United States, 1977–2006. PLoS Med. 2011;8(6):e1001050.

- Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity—the shape of things to come. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(23):2325-7.

- Bonnet J, George A, Evans P, Silberberg M, Dolinsky D. Rethinking obesity counseling: having the French Fry Discussion. J Obes. 2014;2014:525021.

- Grummer-Strawn LM, Scanlon KS, Fein SB. Infant feeding and feeding transitions during the first year of life. Pediatrics. 2008;122 Suppl 2:S36-42.

- Katz D. Obesity . . . be dammed!: what it will take to turn the tide. Harvard Health Policy Rev. 2006;7(2):135-51.

Acknowledgements

Video production by Glass Entertainment

Motion graphics by Avocado Video

- Dr. David Katz

- processed foods

- weight gain

- weight loss

View Transcript

Sources cited, republishing "the role of personal responsibility in the obesity epidemic".

You may republish this material online or in print under our Creative Commons licence . You must attribute the article to NutritionFacts.org with a link back to our website in your republication.

If any changes are made to the original text or video, you must indicate, reasonably, what has changed about the article or video.

You may not use our material for commercial purposes.

You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that restrict others from doing anything permitted here.

If you have any questions, please Contact Us

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

Doctor's note.

It can be helpful, perhaps, to take a step back and think of what’s at stake here. We’re not just talking about being manipulated into buying a different brand of toothpaste. The obesity pandemic has resulted in millions of deaths and untold suffering. And if you’re not mad yet, brace yourself for my next video, The Role of Corporate Influence in the Obesity Epidemic .

This is the ninth in this 11-part series. If you missed any, see:

- The Role of Diet vs. Exercise in the Obesity Epidemic

- The Role of Genes in the Obesity Epidemic

- The Thrifty Gene Theory: Survival of the Fattest

- Cut the Calorie-Rich-And-Processed Foods

- The Role of Processed Foods in the Obesity Epidemic

- The Role of Taxpayer Subsidies in the Obesity Epidemic

- The Role of Marketing in the Obesity Epidemic

The Role of Food Advertisements in the Obesity Epidemic

If you haven’t yet, you can subscribe to my videos for free by clicking here . Read our important information about translations here .

Subscribe to our free newsletter and receive our Daily Dozen Meal Planning Guide .

Flashback Friday: Coffee and Mortality

Subscribe to nutritionfacts.org videos.

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest videos emailed to you or downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select the subscription method below that best fits your lifestyle.

Or subscribe with your favorite app by using the address below:

iOS (iPhone, iPad, and iPod)

To subscribe, select the "Subscribe on iTunes" button above.

To subscribe, select the "Subscribe via E-Mail" button above.

Mac and Windows

Android and amazon fire.

To subscribe, select the "Subscribe on Android" button above.

Using Your Favorite Application

Copy the address found in the box above and paste into your favorite podcast application or news reader.

Bookmarking NutritionFacts.org

To bookmark this site, press the Ctrl + D keys on your Windows keyboard, or Command + D for Mac.

Pin It on Pinterest

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

27 Obesity and Responsibility

Beth Dixon is Professor of Philosophy at S.U.N.Y College at Plattsburgh.

- Published: 11 January 2018

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter explores whether obese individuals are morally responsible for their condition of obesity. The main argument is that some who are classified as obese are exempt from moral responsibility for two possible reasons. Either food situationism may interfere with an individual’s capacity to detect the moral considerations that favor healthy eating. Or, structural inequalities may interfere with an individual’s capacity to act on moral considerations that favor healthy eating. The account of situated moral agency employed here makes it possible to resist the false dichotomy of saying that either all obese individuals are morally responsible for being obese or that they are exempt from responsibility altogether. If moral exemptions apply in the way suggested, then a large number of individuals who are obese do not deserve to be the targets of moral blame, nor do they deserve the moral indignation that is sometimes directed toward them.

Introduction

There is almost no accounting for personal responsibility. People should be (and I believe they are) capable of not consuming everything the market throws their way. — Julie Guthman, Weighing In: Obesity, Food Justice, and the Limits of Capitalism 1

In this essay, I take a closer look at what personal responsibility means in connection to the “problem” of obesity and recommended solutions. 2 What we find in obesity discourse is that the language of personal responsibility sometimes has a moral dimension to it; although the attribution of moral responsibility rarely comes equipped with any clear criteria of application. This is true across a wide range of settings where the expression ‘personal responsibility’ is employed by academics, policy analysts, representatives of the food industry, or by ordinary citizens. This supplies us with sufficient rationale for engaging in a conceptual analysis of moral responsibility and how it applies in these contexts. As I will argue, such an analysis reveals that many who are classified as obese are actually exempt from moral responsibility, contrary to popular opinion.

A second reason for demanding clarity about the concept of moral responsibility as it applies to obesity discourse is that we may be able to use such an account to resist a false dichotomy about moral agency. 3 A prevalent idea about responsibility and obesity seems to suggest one of two possibilities. Either individuals are unequivocally responsible for their condition of being obese or individuals are excused from moral accountability because their condition of obesity is owed primarily to external conditions, namely, the “toxic” food environment, social institutions, public policy, the corporate food industry, or more fundamental unjust structural conditions. 4 As an example of the first position, when defenders of freedom of choice resist the regulation of processed foods and foods high in salt, sugar, and fat, they assume a much too expansive and liberal account of moral agency. They suppose (or want to convince us) that individual consumers already enjoy complete knowledge about the health dangers of processed food, and that they have an ideal kind of freedom to choose what to eat and how much to eat. 5 However, it is more realistic to suppose that moral agents are actually embedded in situations that, to a greater or lesser degree, constrain their knowledge of ethically salient features of the world which influence the control they have over their actions. Alternatively, when basic structural features of the world are implicated as part of a causal explanation for obesity, we are better able to focus on those social and political background conditions that disadvantage populations of people. 6 These contexts, to a greater or lesser degree, limit a person’s access to knowledge and create obstacles to eating healthy food. But, by exclusively emphasizing these structural conditions, it is easy to lose sight of the agency of individuals; what they know and how they can choose to act within the spheres of opportunity open to them. To capture this more realistic idea we should try to formulate a precise way of describing the kind of situated moral agency of individuals that continues to operate even in circumstances that constrain choices and limit opportunities. 7

A practically useful theory of moral responsibility should allow us to apply this account to the case study of obesity. Such an account should do the following: (1) identify what features of individuals matter for assessing moral responsibility. This should include what kinds of conditions count as exemptions from responsibility and blame; (2) allow us to say something specific about environmental circumstances that are salient to the issue of obesity. Since the food environment plays a significant role in discussions about the causes of and solutions to obesity, our theory of moral responsibility should be sensitive to features of these contextual background conditions; (3) specify the relevant kind of individual agency that makes sense of our way of talking about persons who are capable of giving reasons for what they do, and who are capable of exhibiting the relevant kind of control over their actions; and (4) identify a way of extending responsibility ascriptions beyond individual agents to collectives who may be suitable targets for moral blame as institutional or corporate “players” that contribute significantly to producing obesity in particular populations.

Here I employ a particular theory of moral responsibility formulated by Manuel Vargas in order to explain what it means to say that an individual is morally responsible for being obese (or not). 8 Vargas holds what he calls a “revisionist reasons” account of moral responsibility. 9 What is central to reasons accounts, in general, is that in order for a moral agent to be morally responsible for an action she performs, she must have the capacity to respond to reasons. 10 First, she must be capable of having the relevant kind of knowledge about herself and the world to recognize good reasons for acting. And second, she must be capable of responding to reasons by exerting the relevant kind of freedom and control over her actions. In other words, the agent must have the capacity to translate these reasons into motivations for acting and successfully perform an action based on these reasons. I will not argue for Vargas’s theory, per se, but I believe that it is independently plausible and, furthermore, possesses suitable resources for addressing the complexity of the case study of obesity. 11 This is so because it allows us to include in our assessment of individual responsibility those particular features of the environment that are relevant to an individual’s knowledge about, and control over, what she eats. This kind of situated agency is important for preserving our intuitions about how and why people act in practical and real world settings. 12

Finding Fault

In ordinary discourse about obesity and personal responsibility, we can detect a moral complaint about those who are obese and how they came to be that way. Consider the following student comments as reported by Guthman: