- Science & Math

- Sociology & Philosophy

- Law & Politics

Prejudice in The Merchant of Venice

- Prejudice in The Merchant of…

William Shakespeare’s satirical comedy, The Merchant of Venice, believed to have been written in 1596 was an examination of hatred and greed. The premise deals with the antagonistic relationship between Shylock, a Jewish money-lender and Antonio, the Christian merchant, who is as generous as Shylock is greedy, particularly with his friend, Bassanio.

The two have cemented a history of personal insults, and Shylock’s loathing of Antonio intensifies when Antonio refuses to collect interest on loans. Bassanio wishes to borrow 3,000 ducats from Antonio so that he may journey to Belmont and ask the beautiful and wealthy Portia to marry him. Antonio borrows the money from Shylock, and knowing he will soon have several ships in port, agrees to part with a pound of flesh if the loan is not repaid within three months.

Shylock’s abhorrence of Antonio is further fueled by his daughter Jessica’s elopement with Lorenzo, another friend of Antonio’s. Meanwhile, at Belmont, Portia is being courted by Bassanio, and wedding plans continue when, in accordance with her father’s will, Bassanio is asked to choose from three caskets — one gold, one silver and one lead.

Bassanio correctly selects the lead casket that contains Portia’s picture. The couple’s joy is short-lived, however, when Bassanio receives a letter from Antonio, informing him of the loss of his ships and of Shylock’s determination to carry out the terms of the loan. Bassanio and Portia marry, as do his friend, Gratiano and Portia’s maid, Nerissa.

The men return to Venice, but are unable to assist Antonio in court. In desperation, Portia disguises herself as a lawyer and arrives in Venice with her clerk (Nerissa) to argue the case. She reminds Shylock that he can only collect the flesh that the agreement calls for, and that if any blood is shed, his property will be confiscated. At this point, Shylock agrees to accept the money instead of the flesh, but the court punishes him for his greed by forcing him to become a Christian and turn over half of his property to his estranged daughter, Jessica.

Prejudice is a dominant theme in The Merchant of Venice, most notably taking the form of anti-Semitism. Shylock is stereotypically described as “costumed in a recognizably Jewish way in a long gown of gabardine, probably black, with a red beard and/or wing like that of Judas, and a hooked putty nose or bottle nose” (Charney, p. 41).

Shylock is a defensive character because society is constantly reminding him he is different in religion, looks, and motivation. He finds solace in the law because he, himself, is an outcast of society. Shylock is an outsider who is not privy to the rights accorded to the citizens of Venice. The Venetians regard Shylock as a capitalist motivated solely by greed, while they saw themselves as Christian paragons of piety.

When Shylock considers taking Antonio’s bond using his ships as collateral, his bitterness is evident when he quips, “But ships are but board, sailors but men. There be land rats and water rats, water thieves and land thieves — I mean pirates — and then there is the peril of waters, winds, and rocks” (I.iii.25). Shylock believes the Venetians are hypocrites because of their slave ownership.

The Venetians justify their practice of slavery by saying simply, “The slaves are ours” (IV.i.98-100). During the trial sequence, Shylock persuasively argues, “You have among you many a purchased slave, which (like your asses and your dogs and mules). You us in abject and in slavish parts, because you bought them, shall I say to you, let them be free, marry them to your heirs… you will answer, `The slaves are ours,’ — so do I answer you: The pound of flesh (which I demand of him) is dearly bought, ’tis mine and I will have it” (IV.i.90-100).

Shakespeare’s depiction of the Venetians is paradoxical. They are, too, a capitalist people and readily accept his money, however, shun him personally. Like American society, 16th century Venice sought to solidify their commercial reputation through integration, but at the same time, practiced social exclusion. Though they extended their hands to his Shylock’s money, they turned their backs on him socially. When Venetian merchants needed usurer capital to finance their business ventures, Jews flocked to Venice in large numbers.

By the early 1500s, the influx of Jews posed a serious threat to the native population, such that the Venetian government needed to confine the Jews to a specific district. This district was called geto nuovo (New Foundry) and was the ancestor of the modern-day ghetto. In this way, Venetians could still accept Jewish money, but control their influence upon their way of life.

Antonio, though the main character in The Merchant of Venice remains a rather ambiguous figure. Although he has many friends, he still remains a solitary and somewhat melancholy figure. He is generous to a fault with his friends, especially Bassanio, which lends itself to speculation as to his sexuality. His perceived homosexuality makes him somewhat of a pariah among his countrymen, much like Shylock.

Shylock’s loathing of Antonio, he explains simply, “How like a fawning publican he looks! I hate him for he is a Christian” (I.iii.38-39). Antonio holds Shylock in the same contempt, trading barbs with him and spitting at him. His contempt for shylock is further demonstrated when he addresses Shylock in the third person, despite his presence.

Antonio’s prejudice is clearly evident when he asks, “Is he yet possessed? (I.iii.61). The word “possessed” is synonymous with the Devil in the Christian world. In his mind, his greed and his Judaism are one, and because Shylock lacks his (Antonio’s) Christian sensibilities, he is, therefore, the reincarnation of the Devil and the embodiment of all that is evil. Images of a dog, which is coincidentally God spelled backwards, are abound. Society must restrain the Jew because he is an untamed animal.

Shylock sees himself in society’s eyes and muses, “Thou call’dst me a dog before thou hadst a cause. But since I am a dog, beware my fangs (III.iii.6-7).” When Antonio spits on Shylock in public, this is perfectly acceptable behavior in a society where Jews are considered on the same level as dogs. Antonio is presented as a “good” Christian who ultimately shows mercy on his adversary, the “evil” Jew, Shylock. By calling for Shylock’s conversion to Christianity, Antonio is saving a sinner’s soul, and by embracing Christianity, he will be forced to repent and mend his avarice ways.

Most of the women in The Merchant of Venice, true to the Elizabethan time period, are little more than an attractive presence. Despite their immortalization in art, Shakespeare, like his contemporaries, appears to perceive women as little more than indulged play things with little to offer society than physical beauty.

Shylock is devastated when his daughter leaves him to marry a Christian, he regards her as little more than one of his possession, just as he regards jewels and ducats. Portia, though possessing both strength and intelligence, she, too, is inclined to prejudicial judgments. She takes a disdainful view of the lowly class, and dismisses the 3,000 ducats as “a petty debt.”

Although she truly loves Bassanio in spite of his low social rank, Bassanio is initially portrayed as a crass materialist who regards Portia as little more than a prize to be won. Only by marrying her can he achieve any kind of social nobility.

Although Portia plays a powerful role in the play’s climax, she must disguise herself as a man for her words to be taken seriously. Racial prejudice is also hinted at in The Merchant of Venice.

The Prince of Morocco, though elegant in both manner and dress, has a pomposity which perhaps stems from being a dark-skinned man not altogether accepted in the predominantly white Christian surroundings. The bias of the city-state ruler is evident when during the trial, the Duke of Venice tells Shylock, “We all expect a gentle answer, Jew” (IV.i.34).

The implication is that Christians are the models of gentility and social grace, whereas Jews are coarse in both manner and words. Is Shylock really the epitome of evil? Over the years, the “pound of flesh” phrase has been interpreted by both scholars and students alike. Author W.H. Auden draws a similarity between Shylock’s demand for payment in a pound of flesh with the crucifixion of Christ.

Auden wrote, “Christ may substitute himself for man, but the debt has to be paid by death on the cross. The devil is defeated, not because he has no right to demand a penalty, but because he does not know the penalty has been already suffered” (Auden, p. 227).

Shylock regards Antonio as his number one nemesis because of the countless public humiliations he has subjected him to and because Antonio has purposely hindered his business by refusing to collect interest on loans. Would Shylock have demanded a pound of flesh from anyone else in the world but Antonio? Does this make him a bad person or just a human one? By herding the Jews like cattle into the confines of the New Foundry district, aren’t the Venetians symbolically extracting their own pound of flesh from the Jewish people? Why is Shylock singled out for his behavior? Because he is Jewish and therefore incapable of humanity in the eyes of the Christian world?

III. Conclusion

Was William Shakespeare a bigot? His perceived anti-semitism in The Merchant of Venice depicts the Elizabethan perception of Jews, a people who were truly foreign to them in both appearance and demeanor. Edward, I banished Jews from his kingdom in the 11th century, however, Jewish stereotypes abound in England throughout the Renaissance.

Although the average Elizabethan had probably encountered only a few Jews in his lifetime, his church sermons condemned them with words like “blasphemous,” “vain,” and “deceitful.” The Christians considered the lending of money to be sacrilegious, but the using of this money to finance their businesses was not. The Merchant in Venice is no more anti-semitic than Christopher Marlowe’s earlier play, The Jew of Malta.

The parallels between Marlowe’s protagonist, Barabas, and Shylock are startling. Marlowe’s play begins with a description of Barabas “in his counting-house, with heaps of gold before him,” discussing with his comrades his world of “infinite riches” (I.i.37). Barabas’ self-serving deception and superficiality are identical to Shylock’s.

Marlowe’s character, Ferneze acts as a self-appointed spokesman for the Christian community when he dismisses Barabas and all Jews with the words, “No, Jew, like infidels. For through our sufferance of your hateful lives, who stand accursed in the sight of heaven” (I.ii.73-75). Couldn’t Antonio have uttered the same words to Shylock? Both authors were products of the Elizabethan world in which they lived, and their writings were bound to be a reflection of their times.

Was Shakespeare an anti-semitic person, or was The Merchant of Venice a piece of timely social commentary? This will be the fodder for much discussion and argument for years to come. There must be a distinction between Shakespeare the writer and Shakespeare the man, and while there may be similarities, they should be regarded as two separate entities. However, when one reads The Merchant of Venice and speeches illustrating the hypocrisy that was so prevalent in Christian society, one can almost sense Shakespeare is satirically winking at us.

Though the world has moved away from the rigid Elizabethan social convention, have times or people really changed? The continued bloodshed in the Middle East, the ongoing struggle for racial equality in Africa, religious strife in Northern Ireland, and the continued practice of genocide in the world suggest otherwise. What about American society? The recent criminal trial and a subsequent not guilty verdict in the O.J. Simpson case show that racial lines are still carefully drawn.

Isn’t O.J. Simpson reminiscent of Shylock, an outcast in white, Beverly Hills social strata in much the same way as Shylock was in Venice? His upbringing in the slums of San Francisco made him as foreign to southern California socialites as Shylock was to the Venetian bourgeoisie. Despite being found not guilty by a jury of his peers, he has been ostracized by this society nevertheless, and in establishments where his money was once accepted, he now is not. Pending the outcome of his civil trial, he may lose his money and property as did Shylock.

In The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare articulates the frustrations of the oppressed masses for all time with the words of Shylock. “Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions — fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you pick at us, do we not bleed?

If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrongs a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge! If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge! The villainy you teach me I will execute” (II.i.55-69). Quite simply, society teaches by example.

Auden, W.H. 1965. “Brothers and Others,” The Dyer’s Hands and Other Essays. New York: Random House. Charney, Maurice. 1993. All of Shakespeare. New York: Columbia University Press.

Marlowe, Christopher. Ed. Russell A. Fraser and Norman Rabkin. 1976. Drama of the English Renaissance I: The Tutor Period. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.

Shakespeare, William. Ed. Kenneth Myrick. 1965. The Merchant of Venice. New York: Signet Books.

Related Posts

- The Merchant of Venice: Appearance or Reality

- Religious Victimization of Shylock in The Merchant of Venice

- The Merchant of Venice Summary (Acts I-III)

- Merchant of Venice Act II: Theme of Love

- Merchant of Venice: Shylock Analysis

Author: William Anderson (Schoolworkhelper Editorial Team)

Tutor and Freelance Writer. Science Teacher and Lover of Essays. Article last reviewed: 2022 | St. Rosemary Institution © 2010-2024 | Creative Commons 4.0

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post comment

Prejudice In Shakespeare's The Merchant Of Venice Essay Example

Throughout William Shakespeare's play The Merchant of Venice, multiple aspects of prejudice can be seen from various viewpoints. The meaning of prejudice is preconceived perception which is not founded upon justification or on actual experience. Maya Angelou's quotation defining prejudice is, "Prejudice is a burden that confuses the past, threatens the future, and renders the present inaccessible." Angelou’s quotation regarding prejudice, translates to the prejudgment established well before relevant material has been obtained or analyzed, rendering it insufficient or fictional evidence. A significant theme of this play, as well as the major conflicts that emerge, are based upon characters which are racially prejudiced and discriminatory. By incorporating characters of diverse cultures in his play, Shakespeare reveals how most people hold prejudiced attitudes about any culture, religion, and ethnicity that is not their own. And by demonstrating how many conflicts, bias views can create in one's life, he proceeds to show the wrong side of prejudices. There are a variety of different behaviors that demonstrate the forms of prejudice in this play, as many prejudicial characters are prejudice to those of a different origin and have different perspectives as them. There are several biases, behaviors, and values that indicate this predominates: firstly, Portia is racially prejudiced towards her suitors who have dark complexions, this attitude of prejudice can be seen with the Prince of Morocco, secondly, Lancelet has prejudiced thoughts about Jewish people, and this behavior is evident when he makes a joke regarding Jessica’s past religion, and Jewish father, and eventually, Antonio is religions-wise prejudice towards Shylock due to his own beliefs of Shylock's religion, and ethnicity, this prejudicial behavior of Antonio is demonstrated throughout the whole play specifically through the way Antonio talks and behaves with Shylock.

Although Portia is attempting to be the least problematic person with appearances in this play, and is polite to people regardless of gender, race, culture, and religion, her character is also very dishonest, and she is secretly prejudicial and oppressive to those who are not of her own nationality, this is demonstrated by Portia's behavior towards the Prince of Morocco. Portia is, in general, very prejudicial to all her love interests, and cries to Nerissa about the weak characteristics each of them has, she is particularly prejudicial to the Prince of Morocco, as she argues, even if he behaves wonderfully, she still will not be interested in him due to his dark complexion. When the Prince of Morocco arrives and meets Portia, he assures her that she should not be displeased by him or be prejudice against him, as he has the same blood as a man with the fairest skin. Portia then begins to tell him that she does not pick a suitor based on his appearances, in reality she is not driven to choose her own husband at all. When the Prince of Morocco agrees to the terms of Portia's lottery and selects a casket, but fails and leaves, Portia is quite pleased, since her prejudice to those of darker complexions, would not have enabled her to have a successful partnership with the Prince of Morocco. The prejudice feature of Portia is confirmed when the Prince has departed, and she states, "A gentle riddance! Draw the curtains, go. / Let all of his complexion choose me so" (2.7.86-87). Which clearly indicates that she wishes for any suitor with his complexion to make the same selection as him. As mentioned, the whole time that the Prince of Morocco is present with Portia, she is unable to see past his complexion, and her prejudicial characteristic is making her insensitive to the positive attributes about him, and, with Portia as an illustration of prejudices, Shakespeare attempts to remind the reader how prejudicial perceptions can blind an individual to the positive side and make the individual concentrate on the negative side.

In addition, Shakespeare extends this idea of prejudice in his play as he exposes how Lancelet talks to, and teases Jessica about her religion and nationality. Lancelet's character is humorous, and he likes to make himself a comic, but a few of his jokes prove that he is prejudicing Jews, and that he is also racist. Although Lancelet does not like to associate with Shylock, he speaks and jokes with Jessica, and makes a few remarks about Jessica's background that prove his prejudice thoughts about Judaism. Lancelet informs Jessica jokingly, that children are punished for the sins of their fathers, and he says that he's concerned about her, as he thinks that Jessica is going to hell, and he tells her that he believes there's only one hope for her. As Jessica asks him what hope he is talking about, Lancelet says, “Marry, you may partly hope that your father got you not, that you are not the Jew’s daughter” (3.5.10-11). And what he means by his statement is that Jessica can only hope that Shylock is not her true father, that her mother may have fooled around, and that she is not the daughter of “the Jew.” Despite Jessica's attempts to stay away from Shylock, to change her religion from Judaism to Christianity, and to marry Lorenzo, a Christian, she still experiences prejudice against her, only because of her background and her Jewish father. By saying how Jessica would go to hell, not because of her sins, but because of her fathers, who is a Jew, and by referring to Shylock as "the Jew," Lancelet reveals that he is anti-Semitic, and that he has religious prejudiced thoughts towards the Jewish community. In conclusion, Lancelet proves himself religious prejudicial when he jokes about Judaism with Jessica and is judging her based on her background and her Jewish father, and not based on who she is as a person, with this illustration, Shakespeare demonstrates how Christian characters, such as Lancelet, use the religion of the Jewish people and make jokes about it, utterly disrespecting it, and having prejudiced thoughts about it.

Moreover, Antonio, a Christian, is religious prejudiced towards Shylock only because he is a Jew and has a history, religion, and background different from him, not because of Shylock as a human, and this prejudicial attitude of Antonio is proved through his words and actions towards Shylock. Shylock refers to Antonio directly, informing him that Antonio mistreats Shylock because of his religion. This argument occurs when Bassanio requests for a loan from Shylock, using the credit of Antonio. Shylock hates Antonio because of Antonio's prejudice towards him, and because he doesn't like the way Antonio does business. The difference in opinion between Antonio and Shylock sparks Antonio's cruelty towards Shylock and, in return, Shylock's hatred for Antonio. The idea that Antonio is blind to the insensitivity and indignation of his religious slurs is evidenced by the intolerance that is common to their society. Antonio's prejudice to Shylock is evidenced by the fact that Shylock reminds him of all the wrongs he has done to him by insulting his business, calling him a dog, spitting on his Jewish clothing, and kicking him, to which Antonio replies, "I am as like to call thee so again, /To spet on thee again, to spurn thee too" (1.3.140-141). And what Antonio means is that he's going to call Shylock the names again, spit on him, and criticize him again, which simply demonstrates the racial prejudice he has for Jewish people. To conclude, Antonio displays his religious prejudice to Shylock by his actions and his comments to him, and all their dispute is that Antonio is prejudicing Shylock, and Shakespeare, including a character like Antonio in his play, shows the reader how many complications prejudice can bring to one's existence.

In summary, this play reveals the prejudices individuals carry and how their lives and the lives of those in their society are influenced by it. It shows the many effects of putting labels on people that are different from the standard of society. Shakespeare demonstrates how characters like Portia see themselves as superior to anyone else in society, and have prejudiced thoughts about people that are different from them in nationality or race, how characters like Lancelet are religiously prejudiced, and see all religions that are not their own as a joke, and eventually, characters like Antonio who are religiously prejudiced, and utter hurtful things, and cause trouble just because they dislike the religion of others. No matter what form of prejudice one may have, biases blind a person to facts, and prejudging someone on the basis of race, ethnicity, nationality and religion, will make an individual construct an image in their heads, which is not valid in most situations. Overall, by seeing the diverse characters in this play, their different perspectives and the difficulties they encounter, one can see the many negative implications that come with being prejudicial to what is considered "different" from the "normal" in a community.

Related Samples

- The Role of Violence in Shakespeare's Macbeth (Essay Sample)

- Bullet in the Brain by Tobias Wolff Analysis Essay Example

- Oedipus' Downfall Essay Example

- Home Definition In Mohsin Hamid’s novel Exit West

- Sweetness by Toni Morrison Analysis Example

- Richard Lederer: The Case for Short Words

- Strong Love Theme of Pyramus and Thisbe and Romeo and Juliet (Essay Sample)

- The Consequences Of Romeo And Juliet Essay Example

- The Ruined Maid Analysis Essay

- The Power of Your Beliefs (The Crucible by Arthur Miller Book Review)

Didn't find the perfect sample?

You can order a custom paper by our expert writers

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Merchant of Venice — Depiction Of Religious And Racial Prejudice In The Merchant Of Venice

Depiction of Religious and Racial Prejudice in The Merchant of Venice

- Categories: Merchant of Venice Prejudice William Shakespeare

About this sample

Words: 2070 |

11 min read

Published: Aug 6, 2021

Words: 2070 | Pages: 5 | 11 min read

Works Cited

- Ackermann, A. (2015). Merchant of Venice: Stereotypes and the Shylock Problem. Oxford University Press.

- Al-Mahmood, S. M. (2019). A Study of Racial Prejudice in Shakespeare's "The Merchant of Venice." International Journal of Language and Literature, 7(2), 30-36.

- Battenhouse, R. W. (1981). Shakespearean Tragedy: Its Art and Christian Premises. Indiana University Press.

- Black, J. (2000). The Politics of Shakespeare's Performance: An Introduction. Routledge.

- Callaghan, D. (2002). The Merchant of Venice: New Critical Essays. Routledge.

- Greenblatt, S. (2004). Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Hall, K. (2019). Race, Ethnicity and Beyond: The Merchant of Venice and Racial Prejudice. Journal of Human Values, 25(2), 143-150.

- Lamb, M. (2015). “The Quality of Mercy”: Mercy, Forgiveness, and Revenge in Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice. Journal of Literature and Art Studies, 5(7), 598-606.

- Loomba, A. (2018). Shakespeare, Race, and Colonialism. Oxford University Press.

- Shakespeare, W. (2008). The Merchant of Venice. Cambridge University Press.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1.5 pages / 763 words

2 pages / 820 words

7 pages / 3216 words

3.5 pages / 1580 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Merchant of Venice

Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream is a play that reveals its scaffolding. Behavior and motive are explained for comic consistency and unity, almost as if the playwright did not trust our capacity to intuit them. This is [...]

In “The Merchant of Venice”, William Shakespeare explores the cities of contrast which are Venice and Belmont. These two locations in Italy are so antithetic to each other that even characters’ behaviours fluctuate from city to [...]

The definition of loyalty is a strong feeling of support or allegiance. In The Merchant of Venice by William Shakespeare, dependability, integrity, honesty, and faithfulness are key character traits that exhibit the true meaning [...]

Here in Canada, we do not have the death penalty as punishment. Our judicial system shows mercy even to the worst of criminals by sparing their lives. Yet even to this day, in some countries like the USA, the death penalty still [...]

Exciting tales, nail-biting storylines, literature consumes the minds of readers because of its intriguing ideas. With a range of ideas, topics, and views, audiences are compelled to trust writers. Literature remains a known [...]

Tennessee Williams’s play, A Streetcar Named Desire, illustrates the struggle of power between economic classes and the changes taking place in America at that time, regarding social status. The constant tension between Blanche [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

ARTS & CULTURE

Four hundred years later, scholars still debate whether shakespeare’s “merchant of venice” is anti-semitic.

Deconstructing what makes the Bard’s play so problematic

Brandon Ambrosino

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/78/46/78468e8e-a7f2-4823-9608-97546dcf2168/sf37426.jpg)

The Merchant of Venice , with its celebrated and moving passages, remains one of Shakespeare’s most beautiful plays.

Depending on whom you ask, it also remains one of his most repulsive.

"One would have to be blind, deaf and dumb not to recognise that Shakespeare's grand, equivocal comedy The Merchant of Venice is nevertheless a profoundly anti-semitic work,” wrote literary critic Harold Bloom in his 1998 book Shakespeare and the Invention of the Human. In spite of his “ Bardolatry ,” Bloom admitted elsewhere that he’s pained to think the play has done “real harm … to the Jews for some four centuries now.”

Published in 1596, The Merchant of Venice tells the story of Shylock, a Jew, who lends money to Antonio on the condition that he get to cut off a pound of Antonio’s flesh if he defaults on the loan. Antonio borrows the money for his friend Bassanio, who needs it to court the wealthy Portia. When Antonio defaults, Portia, disguised as a man, defends him in court, and ultimately bests Shylock with hair-splitting logic: His oath entitles him to a pound of the Antonio’s flesh, she notes, but not his blood, making any attempt at collecting the fee without killing Antonio, a Christian, impossible. When Shylock realizes he’s been had, it’s too late: He is charged with conspiring against a Venetian citizen, and therefore his fortune is seized. The only way he can keep half his estate is by converting to Christianity.

It doesn’t take a literary genius like Bloom to spot the play’s anti-Jewish elements. Shylock plays the stereotypical greedy Jew, who is spat upon by his Christian enemies, and constantly insulted by them. His daughter runs away with a Christian and abandons her Jewish heritage. After being outsmarted by the gentiles, Shylock is forced to convert to Christianity— at which point, he simply disappears from the play, never to be heard of again.

The fact that The Merchant of Venice was a favorite of Nazi Germany certainly lends credence to the charge of anti-Semitism. Between 1933 and 1939, there were more than 50 productions performed there. While certain elements of the play had to be changed to suit the Nazi agenda, “Hitler's willing directors rarely failed to exploit the anti-Semitic possibilities of the play,” writes Kevin Madigan , professor of Christian history at Harvard Divinity School. And theatergoers responded the way the Nazis intended. In one Berlin production, says Madigan, “the director planted extras in the audiences to shout and whistle when Shylock appeared, thus cuing the audience to do the same.”

To celebrate that Vienna had become Judenrein , “cleansed of Jews,” in 1943, a virulently anti-Semitic leader of the Nazi Youth, Baldur von Schirach, commissioned a performance. When Werner Krauss entered the stage as Shylock, the audience was noticeably repulsed, according to a newspaper account , which John Gross includes in his book Shylock: A Legend and Its Legacy . “With a crash and a weird train of shadows, something revoltingly alien and startlingly repulsive crawled across the stage.”

Of course, Shylock hasn’t always been played like a monster. There’s little argument that he was initially written as a comic figure, with Shakespeare’s original title being The Comical History of The Merchant of Venice . But interpretations began to shift in the 18th century. Nicholas Rowe, one of the first Shakespearean editors, wrote in 1709 that even though the play had up until that point been acted and received comedically, he was convinced it was “designed tragically by the author.” By the middle of that century, Shylock was being portrayed sympathetically, most notably by English stage actor Edmund Kean, who, as one critic put it, “was willing to see in Shylock what no one but Shakespeare had seen — the tragedy of a man.”

But just what exactly did Shakespeare see in the character? Was Shakespeare being anti-Semitic, or was he merely exploring anti-Semitism?

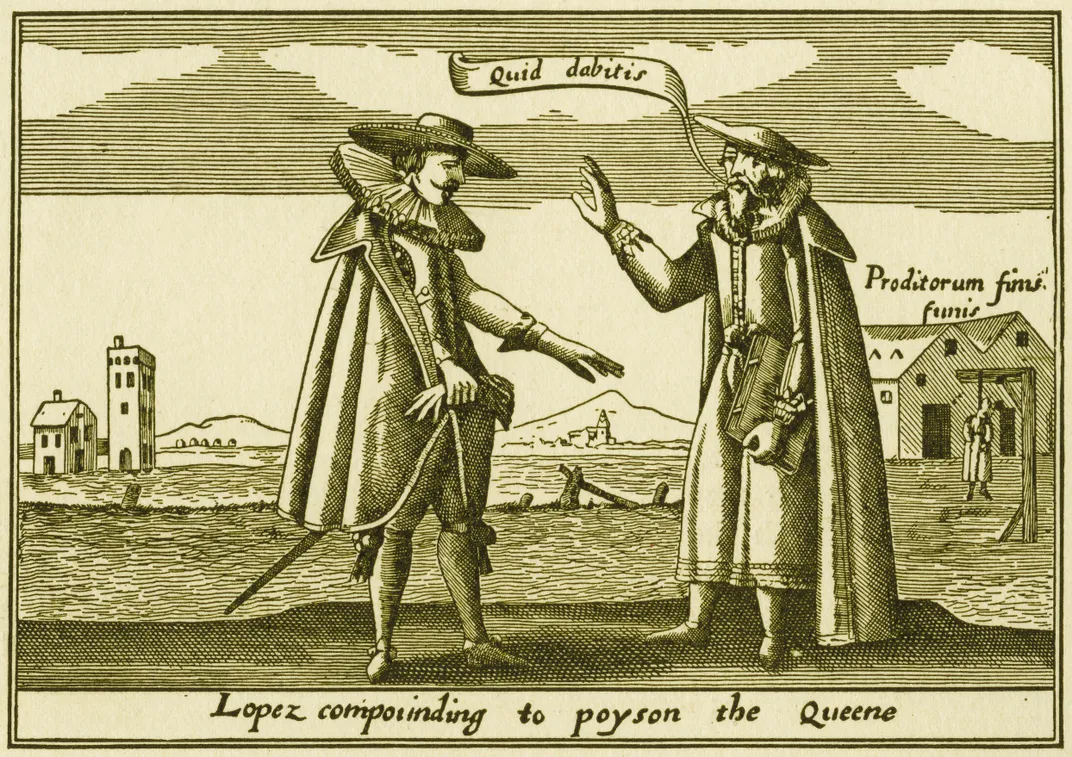

Susannah Heschel, professor of Jewish studies at Dartmouth College, says that critics have long debated what motivated Shakespeare to write this play. Perhaps Christopher Marlowe’s 1590 Jew of Malta , a popular play featuring a Jew seeking revenge against a Christian, had something to do with it. Or perhaps Shakespeare was inspired by the Lopez Affair in 1594, in which the Queen’s physician, who was of Jewish descent, was hanged for alleged treason. And of course, one has to bear in mind that because of the Jews’ expulsion from England in 1290, most of what Shakespeare knew about them was either hearsay or legend.

Regardless of his intentions, Heschel is sure of one thing: “If Shakespeare wanted to write something sympathetic to Jews, he would have done it more explicitly.”

According to Michele Osherow, professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County and Resident Dramaturg at the Folger Theatre in Washington, D.C., many critics think sympathetic readings of Shylock are a post-Holocaust invention. For them, contemporary audiences only read Shylock sympathetically because reading him any other way, in light of the horrors of the Holocaust, would reflect poorly on the reader.

“[Harold] Bloom thinks that no one in Shakespeare's day would have felt sympathy for Shylock,” she says. “But I disagree.”

Defenders of Merchant , like Osherow, usually offer two compelling arguments: Shakespeare’s sympathetic treatment of Shylock, and his mockery of the Christian characters.

While Osherow admits that we don’t have access to Shakespeare’s intentions, she’s convinced that it’s no accident that the Jewish character is given the most humanizing speech in the play.

“Hath not a Jew eyes?” Shylock asks those who question his bloodlust.

Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that.

“Even if you hate Shylock,” says Osherow, “when he asks these questions, there’s a shift: you have an allegiance with him, and I don’t think you ever really recover from it.”

In these few humanizing lines, the curtain is pulled back on Shylock’s character. He might act the villain, but can he be blamed? As he explains to his Christian critics early in the play, “The villainy you teach me I will execute.” In other words, says Osherow, what he’s telling his Christian enemies is, “I’m going to mirror back to you what you really look like.”

Consider general Christian virtues, says Osherow, like showing mercy, or being generous, or loving one’s enemies. “The Christian characters do and do not uphold these principles in varying degrees,” she said. Antonio spits on Shylock, calls him a dog, and says he’d do it again if given the chance. Gratiano, Bassanio’s friend, isn’t content with Shylock losing his wealth, and wants him hanged in the end of the courtroom scene. Portia cannot tolerate the thought of marrying someone with a dark complexion.

“So ‘loving one’s enemies?’” asks Osherow. “Not so much.” The play’s Christian characters, even the ones often looked at as the story’s heroes, aren’t “walking the walk,” she says. “And that’s not subtle.”

The clearest example of the unchristian behavior of the play’s Christians comes during Portia’s famous “ The quality of mercy ” speech. Although she waxes eloquent about grace, let’s not forget, says Heschel, “the way she deceives Shylock is through revenge, and hair-splitting legalism.” She betrays her entire oration about showing people mercy when she fails to show Shylock mercy. Of course, Portia’s hypocrisy should come as no surprise — she announces it during her very first scene. “I can easier teach twenty what were good to be do than to be one of the twenty to follow mine own teaching,” she tells her maid, Nerissa.

As a result of Portia’s sermonizing about how grace resists compulsion, Shylock is forced to convert, clearly the play’s most problematic event. But Osherow thinks some of Shakespeare’s audiences, like contemporary audiences, would’ve understood that as such. “There was so much written about conversion in the early modern period that some churchgoers would have thought [Shakespeare’s Christians] were going about it in completely the wrong way.”

For example, according to A Demonstration To The Christians In Name, Without The Nature Of It: How They Hinder Conversion Of The Jews, a 1629 pamphlet by George Fox, conversion is not as simple as “bringing others to talk as you.” In other words, says Osherow, the forced conversion of Shylock “isn’t how it’s supposed to work according to early modern religious texts.”

Late American theatre critic Charles Marowitz, author of Recycling Shakespeare , noted the importance of this interpretation in the Los Angeles Times . “There is almost as much evil in the defending Christians as there is in the prosecuting Jew, and a verdict that relieves a moneylender of half his wealth and then forces him to convert to save his skin is not really a sterling example of Christian justice.”

Though it’s true that Shakespeare’s mockery (however blatant one finds it) of the play’s Christians doesn’t erase its prejudice, “it goes some way toward redressing the moral balance,” notes Marowitz. In other words, by making the Jew look a little less bad, and the Christians look a little less good, Shakespeare is leveling the moral playing field — which is perhaps what the play hints at when Portia, upon entering the courtroom, seems unable to tell the difference between the Christian and his opponent. “Which is the merchant here, and which the Jew?” she asks.

Now, with all of this in mind, is it accurate to label The Merchant of Venice an anti-Semitic play?

Heschel is correct to point out that Shakespeare isn’t championing Jewish rights (though it might be anachronistic of us to hold him culpable for failing to do so). But she’s also onto something when she suggests the play “opens the door for a questioning” of the entrenched anti-Semitism of his day.

“One thing I’ve always loved about this play is, it’s a constant struggle,” says Osherow. “It feels, on one hand, like it going to be be very conventional in terms of early modern attitudes toward Jews. But then Shakespeare subverts those conventions.”

Aaron Posner, playwright of District Merchants , the Folger’s upcoming adaptation of Merchant , also finds himself struggling to come to terms with the text.

“You can’t read Hath not a Jew eyes?, and not believe Shakespeare was humanizing Shylock and engaging with his humanity. But if you read [the play] as Shakespeare wrote it, he also had no problem making Shylock an object of ridicule.”

“Shakespeare is not interested in having people be consistent,” says Posner.

Like any good playwright, Shakespeare defies us to read his script as anything resembling an after-school special — simple, quick readings and hasty conclusions just won’t do for the Bard.

For District Merchants , Posner has reimagined Shakespeare’s script as being set among Jews and Blacks in a post-Civil War Washington, D.C. In a way, he says, the adaptation reframes the original racism question, because it’s now about two different underclasses — not an overclass and an underclass.

“It was an interesting exercise to take issues raised in Merchant of Venice , and see if they could speak to issues that are part of American history,” he says.

Posner sees it as his prerogative to engage with the moral issues of the play “with integrity and compassion.” Part of that means approaching the play without having his mind made up about some of these tough questions. “If I knew what the conclusion was, I’d be writing essays not plays. I don’t have conclusions or lessons or ‘therefores.’”

Four hundred years after his death, and we’re still confused by the ethical ambiguities of Shakespeare’s plays. That doesn’t mean we stop reading the difficult ones. If anything, it means we study them more intently.

“I think it is absolute idiocy for people to say [of Merchant ], ‘It’s Anti-Jewish’ and therefore they don’t want to study it,” says Heschel. “It’s a treason to Western Civilization. You might as well go live on the moon.”

Despite its negativity towards Judaism, Heschel thinks Merchant is one of the most important pieces of literature from Western Civilization. “What’s important about is to read the play — as I do — in a more complex way, to see whether we are able to read against the grain. That’s important for all of us.”

Perhaps, on one level, Merchant is a play about interpretation.

“Remember Portia’s caskets,” says Osherow, referring to one of the play’s subplots, which has Portia’s would-be suitors try to win her hand by correctly choosing a casket pre-selected by her father. Those quick to be wooed by the silver and gold caskets are disappointed to learn they’ve made the wrong choice. The lead casket is in fact the correct one.

The lesson? “Things are not always what they seem,” says Osherow.

Indeed, a Jewish villain turns out to deserve our sympathy. His Christian opponents turn out to deserve our skepticism. And the play which tells their story turns out to be more complicated than we originally assumed.

Get the latest Travel & Culture stories in your inbox.

Home / Essay Samples / Literature / The Merchant of Venice / Mercantilism And Prejudice In The Merchant Of Venice

Mercantilism And Prejudice In The Merchant Of Venice

- Category: Social Issues , Literature

- Topic: The Merchant of Venice , William Shakespeare

Pages: 2 (850 words)

- Downloads: -->

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

2Nd Amendment Essays

Censorship Essays

Civil Rights Essays

Discrimination Essays

Gender Inequality Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->