Persuasion/Argument

Writing for Success

Learning Objectives

- Determine the purpose and structure of persuasion in writing.

- Identify bias in writing.

- Assess various rhetorical devices.

- Distinguish between fact and opinion.

- Understand the importance of visuals to strengthen arguments.

- Write a persuasive essay.

THE PURPOSE OF PERSUASIVE WRITING

The purpose of persuasion in writing is to convince, motivate, or move readers toward a certain point of view, or opinion. The act of trying to persuade automatically implies more than one opinion on the subject can be argued.

The idea of an argument often conjures up images of two people yelling and screaming in anger. In writing, however, an argument is very different. An argument is a reasoned opinion supported and explained by evidence. To argue in writing is to advance knowledge and ideas in a positive way. Written arguments often fail when they employ ranting rather than reasoning.

Most of us feel inclined to try to win the arguments we engage in. On some level, we all want to be right, and we want others to see the error of their ways. More times than not, however, arguments in which both sides try to win end up producing losers all around. The more productive approach is to persuade your audience to consider your opinion as a valid one, not simply the right one.

THE STRUCTURE OF A PERSUASIVE ESSAY

The following five features make up the structure of a persuasive essay:

- Introduction and thesis

- Opposing and qualifying ideas

- Strong evidence in support of claim

- Style and tone of language

- A compelling conclusion

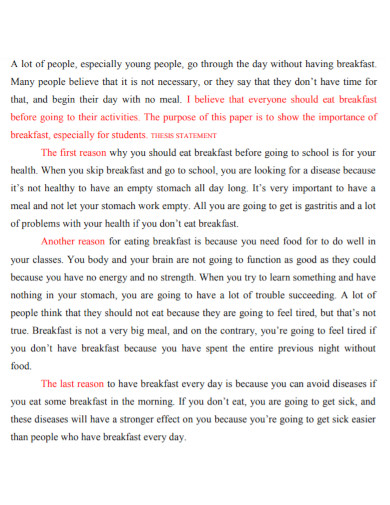

CREATING AN INTRODUCTION AND THESIS

The persuasive essay begins with an engaging introduction that presents the general topic. The thesis typically appears somewhere in the introduction and states the writer’s point of view.

Avoid forming a thesis based on a negative claim. For example, “The hourly minimum wage is not high enough for the average worker to live on.” This is probably a true statement, but persuasive arguments should make a positive case. That is, the thesis statement should focus on how the hourly minimum wage is low or insufficient.

ACKNOWLEDGING OPPOSING IDEAS AND LIMITS TO YOUR ARGUMENT

Because an argument implies differing points of view on the subject, you must be sure to acknowledge those opposing ideas. Avoiding ideas that conflict with your own gives the reader the impression that you may be uncertain, fearful, or unaware of opposing ideas. Thus it is essential that you not only address counterarguments but also do so respectfully.

Try to address opposing arguments earlier rather than later in your essay. Rhetorically speaking, ordering your positive arguments last allows you to better address ideas that conflict with your own, so you can spend the rest of the essay countering those arguments. This way, you leave your reader thinking about your argument rather than someone else’s. You have the last word.

Acknowledging points of view different from your own also has the effect of fostering more credibility between you and the audience. They know from the outset that you are aware of opposing ideas and that you are not afraid to give them space.

It is also helpful to establish the limits of your argument and what you are trying to accomplish. In effect, you are conceding early on that your argument is not the ultimate authority on a given topic. Such humility can go a long way toward earning credibility and trust with an audience. Audience members will know from the beginning that you are a reasonable writer, and audience members will trust your argument as a result. For example, in the following concessionary statement, the writer advocates for stricter gun control laws, but she admits it will not solve all of our problems with crime:

Although tougher gun control laws are a powerful first step in decreasing violence in our streets, such legislation alone cannot end these problems since guns are not the only problem we face.

Such a concession will be welcome by those who might disagree with this writer’s argument in the first place. To effectively persuade their readers, writers need to be modest in their goals and humble in their approach to get readers to listen to the ideas. See Table 10.5 “Phrases of Concession” for some useful phrases of concession.

Try to form a thesis for each of the following topics. Remember the more specific your thesis, the better.

- Foreign policy

- Television and advertising

- Stereotypes and prejudice

- Gender roles and the workplace

- Driving and cell phones

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers. Choose the thesis statement that most interests you and discuss why.

BIAS IN WRITING

Everyone has various biases on any number of topics. For example, you might have a bias toward wearing black instead of brightly colored clothes or wearing jeans rather than formal wear. You might have a bias toward working at night rather than in the morning, or working by deadlines rather than getting tasks done in advance. These examples identify minor biases, of course, but they still indicate preferences and opinions.

Handling bias in writing and in daily life can be a useful skill. It will allow you to articulate your own points of view while also defending yourself against unreasonable points of view. The ideal in persuasive writing is to let your reader know your bias, but do not let that bias blind you to the primary components of good argumentation: sound, thoughtful evidence and a respectful and reasonable address of opposing sides.

The strength of a personal bias is that it can motivate you to construct a strong argument. If you are invested in the topic, you are more likely to care about the piece of writing. Similarly, the more you care, the more time and effort you are apt to put forth and the better the final product will be.

The weakness of bias is when the bias begins to take over the essay—when, for example, you neglect opposing ideas, exaggerate your points, or repeatedly insert yourself ahead of the subject by using I too often. Being aware of all three of these pitfalls will help you avoid them.

THE USE OF I IN WRITING

The use of I in writing is often a topic of debate, and the acceptance of its usage varies from instructor to instructor. It is difficult to predict the preferences for all your present and future instructors, but consider the effects it can potentially have on your writing.

Be mindful of the use of I in your writing because it can make your argument sound overly biased. There are two primary reasons:

- Excessive repetition of any word will eventually catch the reader’s attention—and usually not in a good way. The use of I is no different.

- The insertion of I into a sentence alters not only the way a sentence might sound but also the composition of the sentence itself. I is often the subject of a sentence. If the subject of the essay is supposed to be, say, smoking, then by inserting yourself into the sentence, you are effectively displacing the subject of the essay into a secondary position. In the following example, the subject of the sentence is underlined:

Smoking is bad. I think smoking is bad.

In the first sentence, the rightful subject, smoking, is in the subject position in the sentence. In the second sentence, the insertion of I and think replaces smoking as the subject, which draws attention to I and away from the topic that is supposed to be discussed. Remember to keep the message (the subject) and the messenger (the writer) separate.

Developing Sound Arguments

Does my essay contain the following elements?

- An engaging introduction

- A reasonable, specific thesis that is able to be supported by evidence

- A varied range of evidence from credible sources

- Respectful acknowledgement and explanation of opposing ideas

- A style and tone of language that is appropriate for the subject and audience

- Acknowledgement of the argument’s limits

- A conclusion that will adequately summarize the essay and reinforce the thesis

FACT AND OPINION

Facts are statements that can be definitely proven using objective data. The statement that is a fact is absolutely valid. In other words, the statement can be pronounced as true or false. For example, 2 + 2 = 4. This expression identifies a true statement, or a fact, because it can be proved with objective data.

Opinions are personal views, or judgments. An opinion is what an individual believes about a particular subject. However, an opinion in argumentation must have legitimate backing; adequate evidence and credibility should support the opinion. Consider the credibility of expert opinions. Experts in a given field have the knowledge and credentials to make their opinion meaningful to a larger audience.

For example, you seek the opinion of your dentist when it comes to the health of your gums, and you seek the opinion of your mechanic when it comes to the maintenance of your car. Both have knowledge and credentials in those respective fields, which is why their opinions matter to you. But the authority of your dentist may be greatly diminished should he or she offer an opinion about your car, and vice versa.

In writing, you want to strike a balance between credible facts and authoritative opinions. Relying on one or the other will likely lose more of your audience than it gains.

The word prove is frequently used in the discussion of persuasive writing. Writers may claim that one piece of evidence or another proves the argument, but proving an argument is often not possible. No evidence proves a debatable topic one way or the other; that is why the topic is debatable. Facts can be proved, but opinions can only be supported, explained, and persuaded.

On a separate sheet of paper, take three of the theses you formed in Exercise 1, and list the types of evidence you might use in support of that thesis.

Using the evidence you provided in support of the three theses in Exercise 2, come up with at least one counterargument to each. Then write a concession statement, expressing the limits to each of your three arguments.

USING VISUAL ELEMENTS TO STRENGTHEN ARGUMENTS

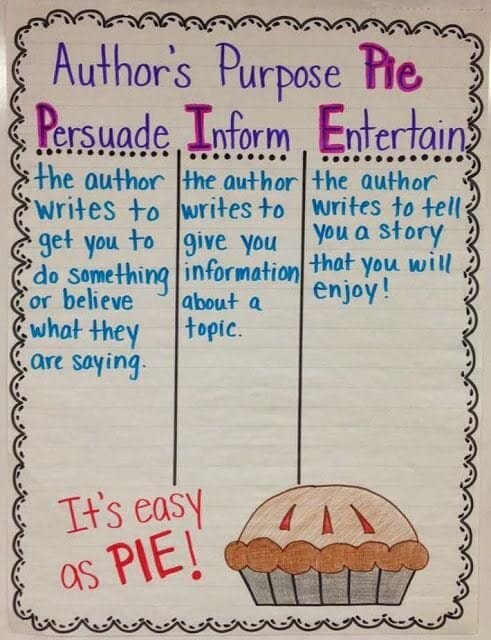

Adding visual elements to a persuasive argument can often strengthen its persuasive effect. There are two main types of visual elements: quantitative visuals and qualitative visuals.

Quantitative visuals present data graphically. They allow the audience to see statistics spatially. The purpose of using quantitative visuals is to make logical appeals to the audience. For example, sometimes it is easier to understand the disparity in certain statistics if you can see how the disparity looks graphically. Bar graphs, pie charts, Venn diagrams, histograms, and line graphs are all ways of presenting quantitative data in spatial dimensions.

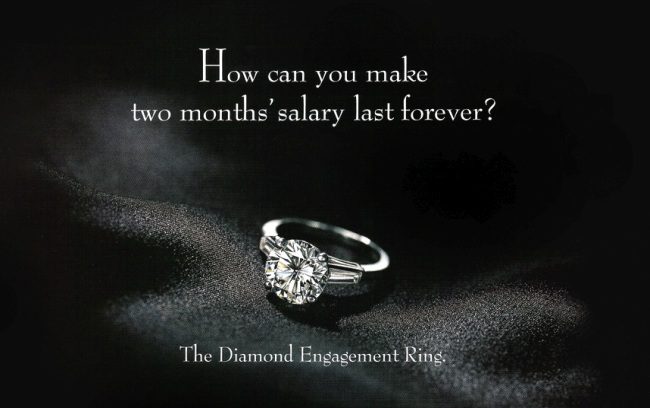

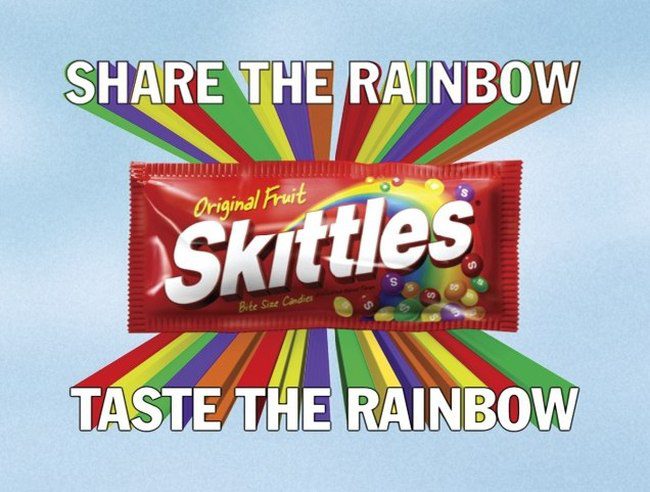

Qualitative visuals present images that appeal to the audience’s emotions. Photographs and pictorial images are examples of qualitative visuals. Such images often try to convey a story, and seeing an actual example can carry more power than hearing or reading about the example. For example, one image of a child suffering from malnutrition will likely have more of an emotional impact than pages dedicated to describing that same condition in writing.

WRITING AT WORK

When making a business presentation, you typically have limited time to get across your idea. Providing visual elements for your audience can be an effective timesaving tool. Quantitative visuals in business presentations serve the same purpose as they do in persuasive writing. They should make logical appeals by showing numerical data in a spatial design. Quantitative visuals should be pictures that might appeal to your audience’s emotions. You will find that many of the rhetorical devices used in writing are the same ones used in the workplace.

WRITING A PERSUASIVE ESSAY

Choose a topic that you feel passionate about. If your instructor requires you to write about a specific topic, approach the subject from an angle that interests you. Begin your essay with an engaging introduction. Your thesis should typically appear somewhere in your introduction.

Start by acknowledging and explaining points of view that may conflict with your own to build credibility and trust with your audience. Also state the limits of your argument. This too helps you sound more reasonable and honest to those who may naturally be inclined to disagree with your view. By respectfully acknowledging opposing arguments and conceding limitations to your own view, you set a measured and responsible tone for the essay.

Make your appeals in support of your thesis by using sound, credible evidence. Use a balance of facts and opinions from a wide range of sources, such as scientific studies, expert testimony, statistics, and personal anecdotes. Each piece of evidence should be fully explained and clearly stated.

Make sure that your style and tone are appropriate for your subject and audience. Tailor your language and word choice to these two factors, while still being true to your own voice.

Finally, write a conclusion that effectively summarizes the main argument and reinforces your thesis.

Choose one of the topics you have been working on throughout this section. Use the thesis, evidence, opposing argument, and concessionary statement as the basis for writing a full persuasive essay. Be sure to include an engaging introduction, clear explanations of all the evidence you present, and a strong conclusion.

Key Takeaways

- The purpose of persuasion in writing is to convince or move readers toward a certain point of view, or opinion.

- An argument is a reasoned opinion supported and explained by evidence. To argue, in writing, is to advance knowledge and ideas in a positive way.

- A thesis that expresses the opinion of the writer in more specific terms is better than one that is vague.

- It is essential that you not only address counterarguments but also do so respectfully.

- It is also helpful to establish the limits of your argument and what you are trying to accomplish through a concession statement.

- To persuade a skeptical audience, you will need to use a wide range of evidence. Scientific studies, opinions from experts, historical precedent, statistics, personal anecdotes, and current events are all types of evidence that you might use in explaining your point.

- Make sure that your word choice and writing style is appropriate for both your subject and your audience.

- You should let your reader know your bias, but do not let that bias blind you to the primary components of good argumentation: sound, thoughtful evidence and respectfully and reasonably addressing opposing ideas.

- You should be mindful of the use of I in your writing because it can make your argument sound more biased than it needs to.

- Facts are statements that can be proven using objective data.

- Opinions are personal views, or judgments, that cannot be proven.

- In writing, you want to strike a balance between credible facts and authoritative opinions.

- Quantitative visuals present data graphically. The purpose of using quantitative visuals is to make logical appeals to the audience.

- Qualitative visuals present images that appeal to the audience’s emotions.

Persuasion/Argument Copyright © 2016 by Writing for Success is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Feedback/errata.

Comments are closed.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write a Persuasive Essay: Tips and Tricks

Allison Bressmer

Most composition classes you’ll take will teach the art of persuasive writing. That’s a good thing.

Knowing where you stand on issues and knowing how to argue for or against something is a skill that will serve you well both inside and outside of the classroom.

Persuasion is the art of using logic to prompt audiences to change their mind or take action , and is generally seen as accomplishing that goal by appealing to emotions and feelings.

A persuasive essay is one that attempts to get a reader to agree with your perspective.

Ready for some tips on how to produce a well-written, well-rounded, well-structured persuasive essay? Just say yes. I don’t want to have to write another essay to convince you!

How Do I Write a Persuasive Essay?

What are some good topics for a persuasive essay, how do i identify an audience for my persuasive essay, how do you create an effective persuasive essay, how should i edit my persuasive essay.

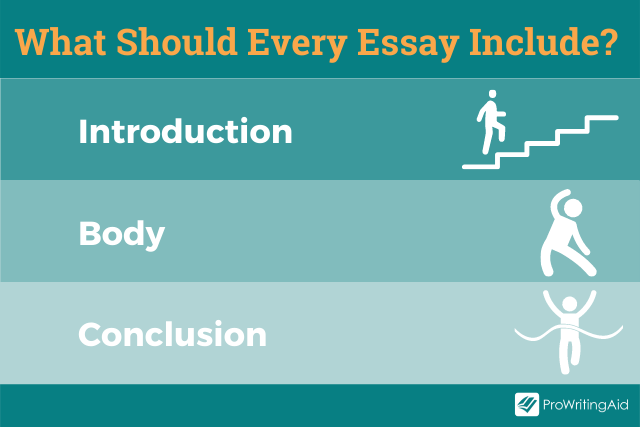

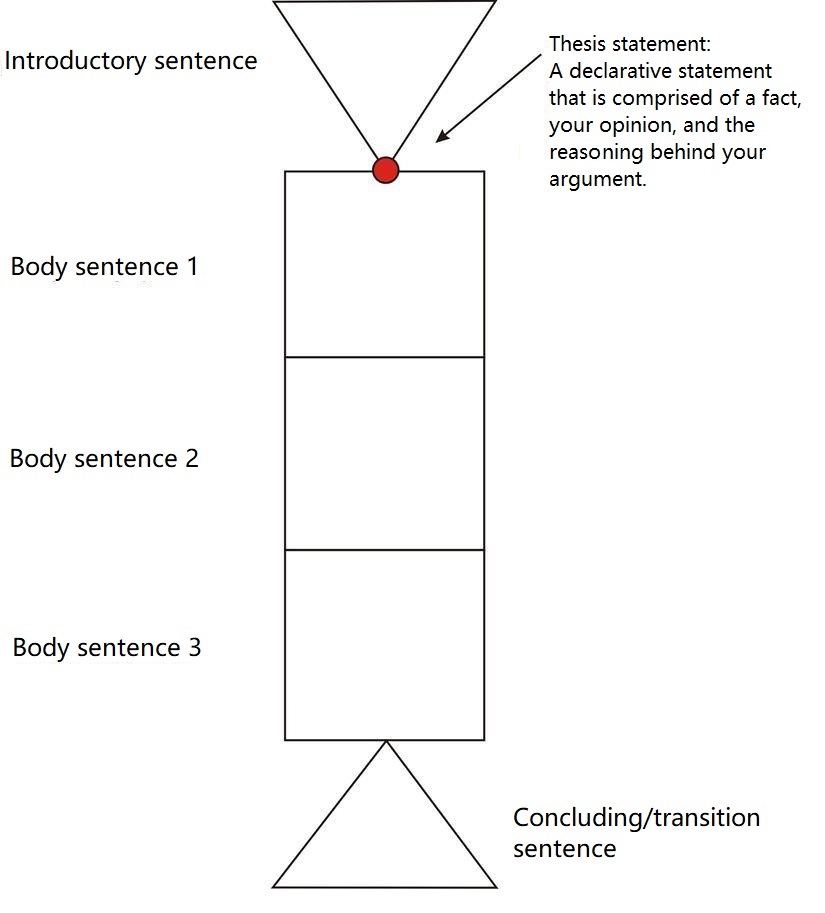

Your persuasive essay needs to have the three components required of any essay: the introduction , body , and conclusion .

That is essay structure. However, there is flexibility in that structure.

There is no rule (unless the assignment has specific rules) for how many paragraphs any of those sections need.

Although the components should be proportional; the body paragraphs will comprise most of your persuasive essay.

How Do I Start a Persuasive Essay?

As with any essay introduction, this paragraph is where you grab your audience’s attention, provide context for the topic of discussion, and present your thesis statement.

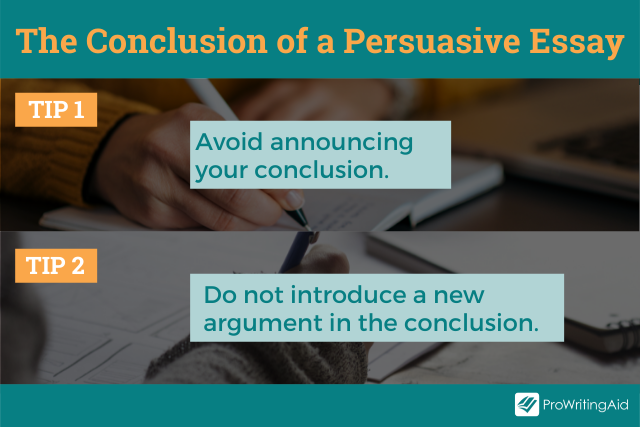

TIP 1: Some writers find it easier to write their introductions last. As long as you have your working thesis, this is a perfectly acceptable approach. From that thesis, you can plan your body paragraphs and then go back and write your introduction.

TIP 2: Avoid “announcing” your thesis. Don’t include statements like this:

- “In my essay I will show why extinct animals should (not) be regenerated.”

- “The purpose of my essay is to argue that extinct animals should (not) be regenerated.”

Announcements take away from the originality, authority, and sophistication of your writing.

Instead, write a convincing thesis statement that answers the question "so what?" Why is the topic important, what do you think about it, and why do you think that? Be specific.

How Many Paragraphs Should a Persuasive Essay Have?

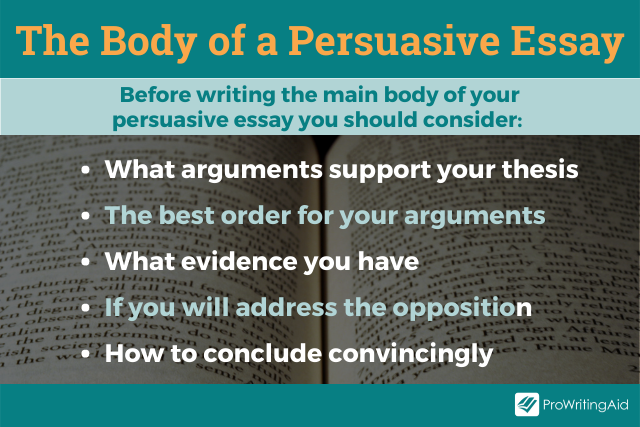

This body of your persuasive essay is the section in which you develop the arguments that support your thesis. Consider these questions as you plan this section of your essay:

- What arguments support your thesis?

- What is the best order for your arguments?

- What evidence do you have?

- Will you address the opposing argument to your own?

- How can you conclude convincingly?

TIP: Brainstorm and do your research before you decide which arguments you’ll focus on in your discussion. Make a list of possibilities and go with the ones that are strongest, that you can discuss with the most confidence, and that help you balance your rhetorical triangle .

What Should I Put in the Conclusion of a Persuasive Essay?

The conclusion is your “mic-drop” moment. Think about how you can leave your audience with a strong final comment.

And while a conclusion often re-emphasizes the main points of a discussion, it shouldn’t simply repeat them.

TIP 1: Be careful not to introduce a new argument in the conclusion—there’s no time to develop it now that you’ve reached the end of your discussion!

TIP 2 : As with your thesis, avoid announcing your conclusion. Don’t start your conclusion with “in conclusion” or “to conclude” or “to end my essay” type statements. Your audience should be able to see that you are bringing the discussion to a close without those overused, less sophisticated signals.

If your instructor has assigned you a topic, then you’ve already got your issue; you’ll just have to determine where you stand on the issue. Where you stand on your topic is your position on that topic.

Your position will ultimately become the thesis of your persuasive essay: the statement the rest of the essay argues for and supports, intending to convince your audience to consider your point of view.

If you have to choose your own topic, use these guidelines to help you make your selection:

- Choose an issue you truly care about

- Choose an issue that is actually debatable

Simple “tastes” (likes and dislikes) can’t really be argued. No matter how many ways someone tries to convince me that milk chocolate rules, I just won’t agree.

It’s dark chocolate or nothing as far as my tastes are concerned.

Similarly, you can’t convince a person to “like” one film more than another in an essay.

You could argue that one movie has superior qualities than another: cinematography, acting, directing, etc. but you can’t convince a person that the film really appeals to them.

Once you’ve selected your issue, determine your position just as you would for an assigned topic. That position will ultimately become your thesis.

Until you’ve finalized your work, consider your thesis a “working thesis.”

This means that your statement represents your position, but you might change its phrasing or structure for that final version.

When you’re writing an essay for a class, it can seem strange to identify an audience—isn’t the audience the instructor?

Your instructor will read and evaluate your essay, and may be part of your greater audience, but you shouldn’t just write for your teacher.

Think about who your intended audience is.

For an argument essay, think of your audience as the people who disagree with you—the people who need convincing.

That population could be quite broad, for example, if you’re arguing a political issue, or narrow, if you’re trying to convince your parents to extend your curfew.

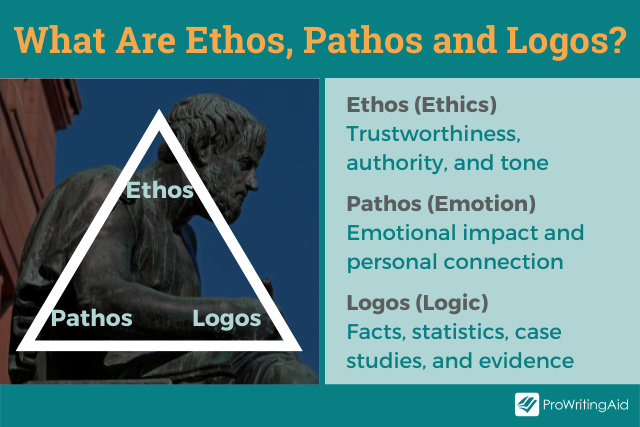

Once you’ve got a sense of your audience, it’s time to consult with Aristotle. Aristotle’s teaching on persuasion has shaped communication since about 330 BC. Apparently, it works.

Aristotle taught that in order to convince an audience of something, the communicator needs to balance the three elements of the rhetorical triangle to achieve the best results.

Those three elements are ethos , logos , and pathos .

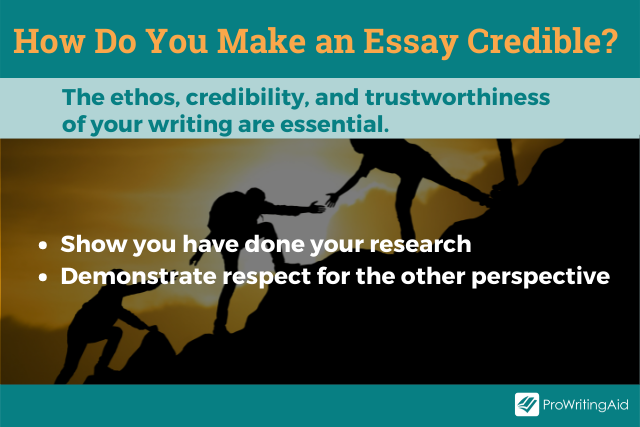

Ethos relates to credibility and trustworthiness. How can you, as the writer, demonstrate your credibility as a source of information to your audience?

How will you show them you are worthy of their trust?

- You show you’ve done your research: you understand the issue, both sides

- You show respect for the opposing side: if you disrespect your audience, they won’t respect you or your ideas

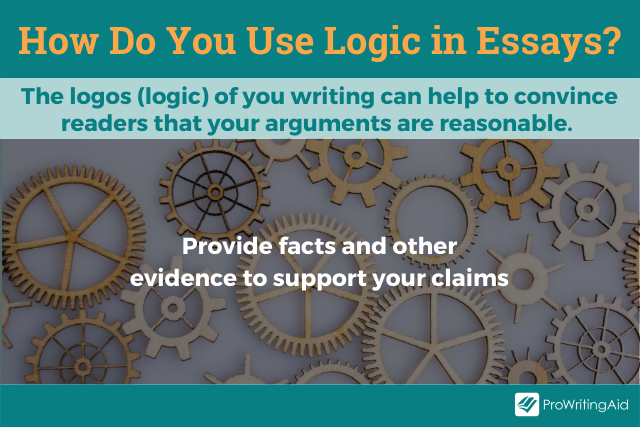

Logos relates to logic. How will you convince your audience that your arguments and ideas are reasonable?

You provide facts or other supporting evidence to support your claims.

That evidence may take the form of studies or expert input or reasonable examples or a combination of all of those things, depending on the specific requirements of your assignment.

Remember: if you use someone else’s ideas or words in your essay, you need to give them credit.

ProWritingAid's Plagiarism Checker checks your work against over a billion web-pages, published works, and academic papers so you can be sure of its originality.

Find out more about ProWritingAid’s Plagiarism checks.

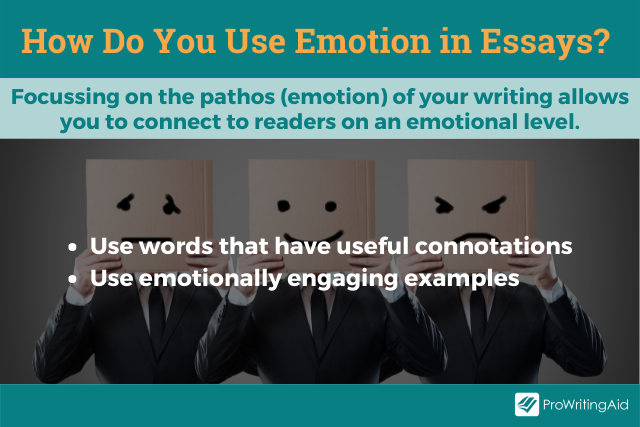

Pathos relates to emotion. Audiences are people and people are emotional beings. We respond to emotional prompts. How will you engage your audience with your arguments on an emotional level?

- You make strategic word choices : words have denotations (dictionary meanings) and also connotations, or emotional values. Use words whose connotations will help prompt the feelings you want your audience to experience.

- You use emotionally engaging examples to support your claims or make a point, prompting your audience to be moved by your discussion.

Be mindful as you lean into elements of the triangle. Too much pathos and your audience might end up feeling manipulated, roll their eyes and move on.

An “all logos” approach will leave your essay dry and without a sense of voice; it will probably bore your audience rather than make them care.

Once you’ve got your essay planned, start writing! Don’t worry about perfection, just get your ideas out of your head and off your list and into a rough essay format.

After you’ve written your draft, evaluate your work. What works and what doesn’t? For help with evaluating and revising your work, check out this ProWritingAid post on manuscript revision .

After you’ve evaluated your draft, revise it. Repeat that process as many times as you need to make your work the best it can be.

When you’re satisfied with the content and structure of the essay, take it through the editing process .

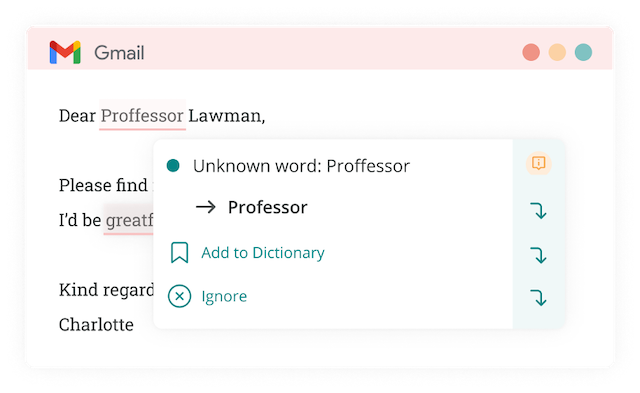

Grammatical or sentence-level errors can distract your audience or even detract from the ethos—the authority—of your work.

You don’t have to edit alone! ProWritingAid’s Realtime Report will find errors and make suggestions for improvements.

You can even use it on emails to your professors:

Try ProWritingAid with a free account.

How Can I Improve My Persuasion Skills?

You can develop your powers of persuasion every day just by observing what’s around you.

- How is that advertisement working to convince you to buy a product?

- How is a political candidate arguing for you to vote for them?

- How do you “argue” with friends about what to do over the weekend, or convince your boss to give you a raise?

- How are your parents working to convince you to follow a certain academic or career path?

As you observe these arguments in action, evaluate them. Why are they effective or why do they fail?

How could an argument be strengthened with more (or less) emphasis on ethos, logos, and pathos?

Every argument is an opportunity to learn! Observe them, evaluate them, and use them to perfect your own powers of persuasion.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Allison Bressmer is a professor of freshman composition and critical reading at a community college and a freelance writer. If she isn’t writing or teaching, you’ll likely find her reading a book or listening to a podcast while happily sipping a semi-sweet iced tea or happy-houring with friends. She lives in New York with her family. Connect at linkedin.com/in/allisonbressmer.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

How to Write a Persuasive Essay

Connecting With Readers on an Emotional Level Takes Skill and Careful Planning

- Writing Essays

- Writing Research Papers

- English Grammar

- M.A., English Literature, California State University - Sacramento

- B.A., English, California State University - Sacramento

When writing a persuasive essay, the author's goal is to sway the reader to share his or her opinion. It can be more difficult than making an argument , which involves using facts to prove a point. A successful persuasive essay will reach the reader on an emotional level, much the way a well-spoken politician does. Persuasive speakers aren't necessarily trying to convert the reader or listener to completely change their minds, but rather to consider an idea or a focus in a different way. While it's important to use credible arguments supported by facts, the persuasive writer wants to convince the reader or listener that his or her argument is not simply correct, but convincing as well.

The are several different ways to choose a topic for your persuasive essay . Your teacher may give you a prompt or a choice of several prompts. Or you may have to come up with a topic, based on your own experience or the texts you've been studying. If you do have some choice in the topic selection, it's helpful if you select one that interests you and about which you already feel strongly.

Another key factor to consider before you begin writing is the audience. If you're trying to persuade a roomful of teachers that homework is bad, for instance, you'll use a different set of arguments than you would if the audience was made up of high school students or parents.

Once you have the topic and have considered the audience, there are a few steps to prepare yourself before you begin writing your persuasive essay:

- Brainstorm. Use whatever method of brainstorming works best for you. Write down your thoughts about the topic. Make sure you know where you stand on the issue. You can even try asking yourself some questions. Ideally, you'll try to ask yourself questions that could be used to refute your argument, or that could convince a reader of the opposite point of view. If you don't think of the opposing point of view, chances are your instructor or a member of your audience will.

- Investigate. Talk to classmates, friends, and teachers about the topic. What do they think about it? The responses that you get from these people will give you a preview of how they would respond to your opinion. Talking out your ideas, and testing your opinions, is a good way to collect evidence. Try making your arguments out loud. Do you sound shrill and angry, or determined and self-assured? What you say is as important as how you say it.

- Think. It may seem obvious, but you really have to think about how you are going to persuade your audience. Use a calm, reasoning tone. While persuasive essay writing is at its most basic an exercise in emotion, try not to choose words that are belittling to the opposing viewpoint, or that rely on insults. Explain to your reader why, despite the other side of the argument, your viewpoint is the "right," most logical one.

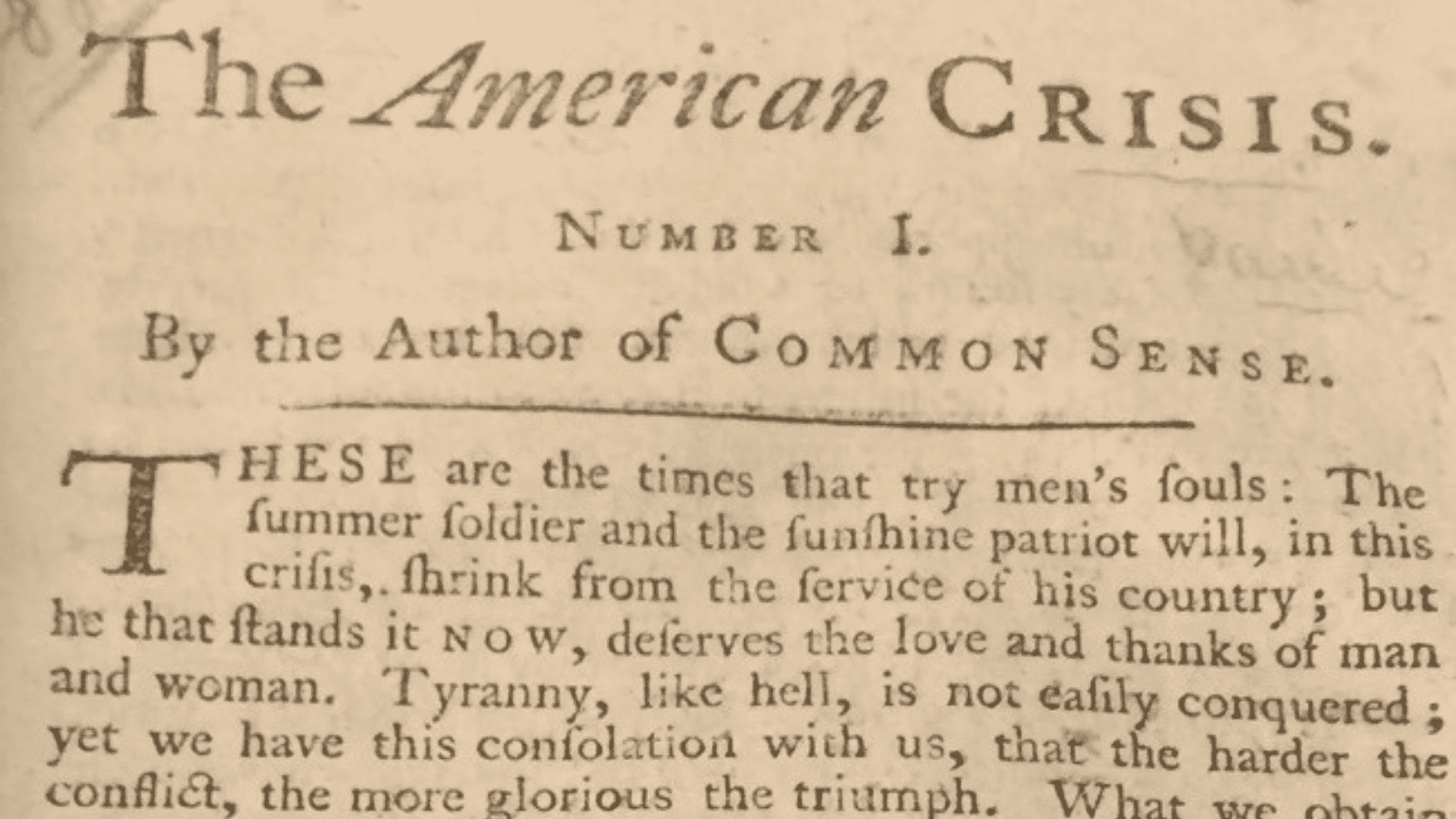

- Find examples. There are many writers and speakers who offer compelling, persuasive arguments. Martin Luther King Jr.'s " I Have a Dream " speech is widely cited as one of the most persuasive arguments in American rhetoric. Eleanor Roosevelt's " The Struggle for Human Rights " is another example of a skilled writer trying to persuade an audience. But be careful: While you can emulate a certain writer's style, be careful not to stray too far into imitation. Be sure the words you're choosing are your own, not words that sound like they've come from a thesaurus (or worse, that they're someone else's words entirely).

- Organize. In any paper that you write you should make sure that your points are well-organized and that your supporting ideas are clear, concise, and to the point. In persuasive writing, though, it is especially important that you use specific examples to illustrate your main points. Don't give your reader the impression that you are not educated on the issues related to your topic. Choose your words carefully.

- Stick to the script. The best essays follow a simple set of rules: First, tell your reader what you're going to tell them. Then, tell them. Then, tell them what you've told them. Have a strong, concise thesis statement before you get past the second paragraph, because this is the clue to the reader or listener to sit up and pay attention.

- Review and revise. If you know you're going to have more than one opportunity to present your essay, learn from the audience or reader feedback, and continue to try to improve your work. A good argument can become a great one if properly fine-tuned.

- 100 Persuasive Essay Topics

- 50 Argumentative Essay Topics

- 100 Persuasive Speech Topics for Students

- Examples of Great Introductory Paragraphs

- How to Write and Structure a Persuasive Speech

- Persuasion and Rhetorical Definition

- Persuasive Writing: For and Against

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- Ethos, Logos, Pathos for Persuasion

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- 5 Steps to Writing a Position Paper

- What Is Expository Writing?

- 49 Opinion Writing Prompts for Students

- How to Write a Narrative Essay or Speech

- Writing Prompt (Composition)

- Convince Me: A Persuasive Writing Activity

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

13.7: Writing a Persuasive Essay

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 6453

- Amber Kinonen, Jennifer McCann, Todd McCann, & Erica Mead

- Bay College Library

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Choose a topic that you feel passionate about. If your instructor requires you to write about a specific topic, approach the subject from an angle that interests you. Begin your essay with an engaging introduction. Your thesis should typically appear near the end of your introduction.

Make your appeals in support of your thesis by using sound, credible evidence. Use a balance of facts and opinions from a wide range of sources, such as scientific studies, expert testimony, statistics, and personal anecdotes. Each piece of evidence should be fully explained and clearly stated.

Acknowledge and explain points of view that may conflict with your own to build credibility and trust with your audience. Also state the limits of your argument. This, too, helps you sound more reasonable and honest to those who may naturally be inclined to disagree with your view. By respectfully acknowledging opposing arguments and conceding limitations to your own view, you set a measured and responsible tone for the essay.

Make sure that your style and tone are appropriate for your subject and audience. Tailor your language and word choice to these two factors, while still being true to your own voice.

Finally, write a conclusion that effectively summarizes the main argument and reinforces your thesis.

key takeaways

- The purpose of persuasion in writing is to convince or move readers toward a certain point of view, or opinion.

- An argument is a reasoned opinion supported and explained by evidence. To argue, in writing, is to advance knowledge and ideas in a positive way.

- A thesis that expresses the opinion of the writer in more specific terms is better than one that is vague.

- It is essential that you not only address counterarguments but also do so respectfully.

- It is also helpful to establish the limits of your argument and what you are trying to accomplish through a concession statement.

- To persuade a skeptical audience, you will need to use a wide range of evidence from credible sources. Scientific studies, opinions from experts, historical precedent, statistics, personal anecdotes, and current events are all types of evidence that you might use in explaining your point.

- Make sure that your word choice and writing style is appropriate for both your subject and your audience.

- You should let your reader know your bias, but do not let that bias blind you to the primary components of good argumentation: sound, thoughtful evidence and respectfully and reasonably addressing opposing ideas.

- You should be mindful of the use of I in your writing because it can make your argument sound more biased than it needs to.

- Facts are statements that can be proven using objective data.

- Opinions are personal views, or judgments, that cannot be proven.

- In writing, you want to strike a balance between credible facts and authoritative opinions.

- Quantitative visuals present data graphically. The purpose of using quantitative visuals is to make logical appeals to the audience.

- Qualitative visuals present images that appeal to the audience’s emotions.

Examples of Essays

- “The Case Against Torture,” by Alisa Solomon

- “The Case for Torture,” by Michael Levin

- “Supporting Family Values,” by Linda Chavez

- “Gay ‘Marriage’: Societal Suicide,” by Charles Colson

- “Waste Not, Want Not,” by Bill McKibben

- “Forget Shorter Showers” by Derrick Jensen

- “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All,” by Ann-Marie Slaughter

- “Having it All?’ How About; ‘Doing the Best I Can?’” by Andrew Cohen

- “Against Headphones” by Virgina Heffernan

- “I Have a Dream,” by Martin Luther King Jr.

How to Write a Persuasive Essay?

30 May, 2020

13 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

Did Shakespeare write all his own works? Is climate change real? Do dogs make better pets than cats? All these topics and more could be subjects for a persuasive essay. While other essays are meant to entertain, such as narrative essay, or inform such as informative essay, the goal of a persuasive essay is to champion a single belief.

What Is a Persuasive Essay?

It is a piece of academic writing that clearly outlines the author’s point of view on a specific issue or topic. The main purpose behind this type of paper is to lay out facts and present ideas that convince the reader to take the author’s side (on the issue or question raised).

There is a common misconception that a persuasive essay is the same as an argumentative essay . This is far from the truth. While an argumentative essay presents information that supports the claim or argument, it is the persuasive type that serves only one mission – to persuade the reader to take your side of the argument.

This article will cover the main steps of writing a good persuasive essay. Let’s get straight into it.

Which Steps to Take?

This guide will provide all the necessary information for students to create an outstanding essay. We’ll review the whole process from outline and research to drafting and revision. As with most academic essays, the persuasive essay should have an intro, several body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Your body paragraphs should present the research, whereas your introduction’s purpose is to provide background information, and the conclusion should review the strongest points of your essay.

1. Conduct research and pre-write

A good essay requires some work before you begin to write. It’s always helpful to sit down and do some prewriting. Consider answering the following questions before you conduct any research:

- What audience am I writing for?

- What information will be useful to my audience?

- What background information would be relevant to this topic?

- What are the different sides of this issue?

- What side will I persuade the audience to take?

- What type of primary resources would be best for this topic?

Related Post: 100 Persuasive essay topics

Once you’ve answered these prewriting questions, it’s time to choose your approach . Select an approach that you are comfortable arguing for, and look for sources that support this particular viewpoint. It’s imperative that you understand your target audience. Finally, it’s time to do your research. Go into the research process armed with the following tools:

- At least 10–20 different search terms relevant to the topic

- A list of best sources: books, journal articles, magazine articles, newspaper articles etc.

- Required citation method (MLA, APA, Chicago…)

- A note-taking method that works best for you (notecards, sentence outlines…) Organize ideas and examples

2. Organize ideas and examples

As you’re conducting research, save yourself some time and organize the ideas as you find them. All of your claims should be supported with proper examples – illustrate ideas with the help of vivid examples. Reflecting on your own real-life experiences can be just as good as using more conventional examples.

Evaluate the purpose of the research and place it in a section where it directly supports the main idea of the paragraph.

Persuasive essay example

Don’t hesitate to use this paper as an example of a persuasive essay. Remember that at Handmadewriting You may order a paper on any topic. We’re ready for your tasks 24/7!

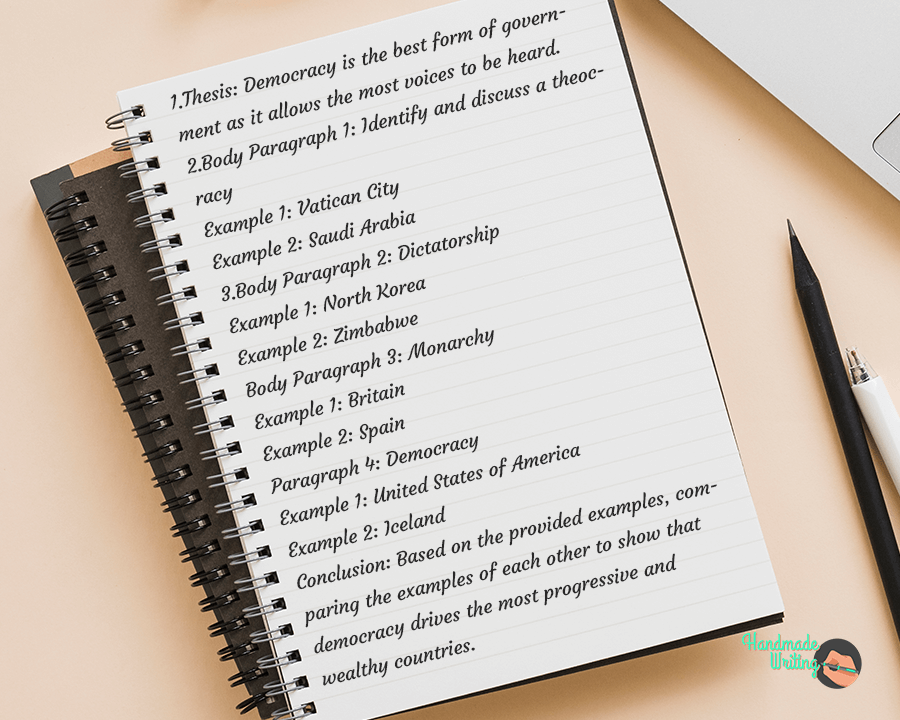

3. Create a persuasive essay outline

Outlines are a useful way to see what you’ve found, and what you still need to find to create a strong, balanced argument regarding the topic of your essay. By creating an outline, you’ll be able to see if you’ve found information that supports the idea within the topic sentence for everybody paragraph or for only two out of the three. The outline also helps you create an argument that flows. Remember: body paragraphs should always be organized weakest to strongest—that way the audience is left with the best paragraph.

Here is an outline example:

For this example outline, the student needs to find research for each country and its form of government. Once it has been gathered, it’s time to begin drafting the paragraphs.

Check our writing guide for a Persuasive Essay Outline:

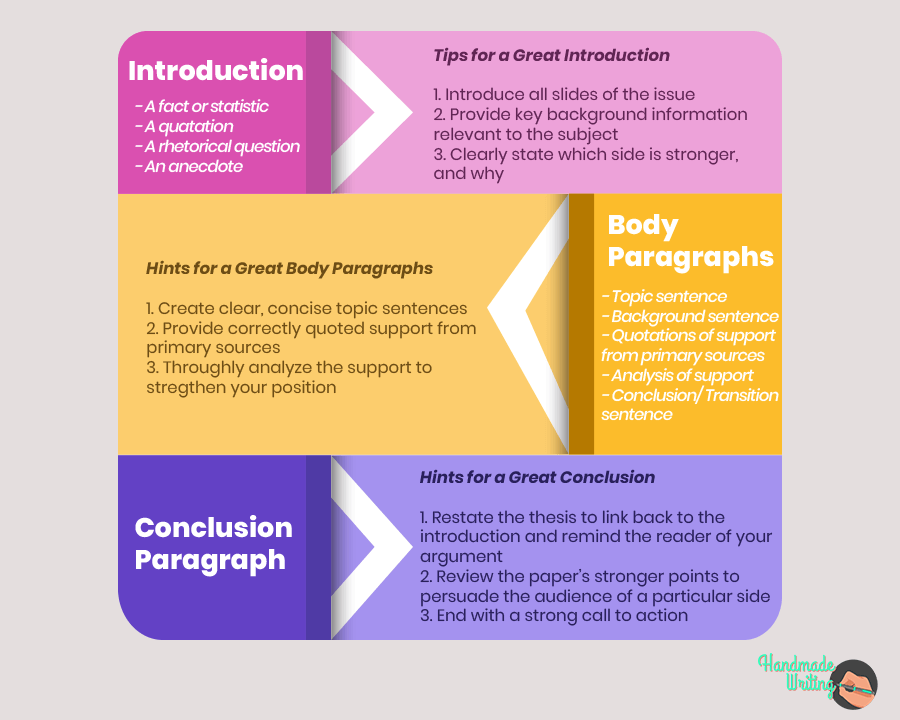

4. Compose the introduction

Each introduction should begin with a hook. This sentence draws the reader into the topic by “hooking” his or her interest. A hook is typically one of four types of sentences:

- A fact or statistic

- A quotation

- A rhetorical question

- An anecdote

In persuasive writing, the introduction paragraph tends to be longer than in other academic essays. This is because all sides of the controversial must be introduced and defined. Remember: not every issue will have two sides; many issues are very complex and may have three or four or more sides that need to be acknowledged, defined, and discussed before moving into the body paragraphs.

Related post: Complete Essay Introduction Guide

Not sure how a subject could have more than merely two sides? Let’s take a look at a typical persuasive essay assigned in social studies or history class: what kind of government is the best? In order to answer this question, the student would have to acknowledge and consider the most common forms of government including a democracy, theocracy, dictatorship, and monarchy. A well-written persuasive essay would introduce all the forms and define them in the intro before delving into the strengths and weaknesses within the body paragraphs.

5. Create a thesis statement

The final part of your introduction should cover the thesis statement . A thesis statement is a brief summary that describes the main argument of your paper. It helps you demonstrate your knowledge of the subject and create a context for your arguments. After reading your thesis statement, a reader should be able to understand your position and recognize your expertise in a particular field.

This statement should be argumentative in nature and clearly state which side you are going to take. As the last sentence in the introduction, it acts as a natural transition to the first body paragraph. A thesis statement is usually only one or two sentences long , but it can sometimes extend to a full paragraph. You are not presenting any evidence since it is merely a description of intent at this stage.

Thesis statement does not state your opinion or list facts but rather identifies what you will be arguing for or against within the body of your essay. Thesis statements should be accurate, clear, and on-topic.

Tips for a great introduction

- Introduce all sides of the issue

- Provide key background information relevant to the subject

- Clearly state which side is stronger, and why

- Formulate body paragraphs

Like most other academic essays, the body paragraphs should follow the typical format of including five kinds of sentences:

- Topic sentence

- Background sentence

- Quotations of support from primary sources

- Analysis of support

- Conclusion/transition sentence

While there are five kinds of sentences, there will likely be more than five sentences in the paragraph. There may be several background sentences, and in your research, you may find quotations from several different sources to include in one paragraph…that’s great! The most important part of the paragraph is the analysis section; this is where you make your case for supporting or weakening an argument.

If you are still unsure on whether you can cope with your task – you are in the right place to buy persuasive essay

6. Counter Arguments

A key aspect of a persuasive essay is the counter-argument. This form of argument allows the writer to acknowledge any opposition to their stance and then pick it apart. For example, if the essay writer is arguing that democracy is the best form of government, he or she needs to take the time to acknowledge counter-arguments FOR other forms of governments and then disprove them. Including counter arguments as paragraphs themselves ultimately strengthens one’s own argument.

Hints for Great Body Paragraphs

- Create clear, concise topic sentences

- Provide correctly quoted support from primary sources

- Thoroughly analyze the support to strengthen your position

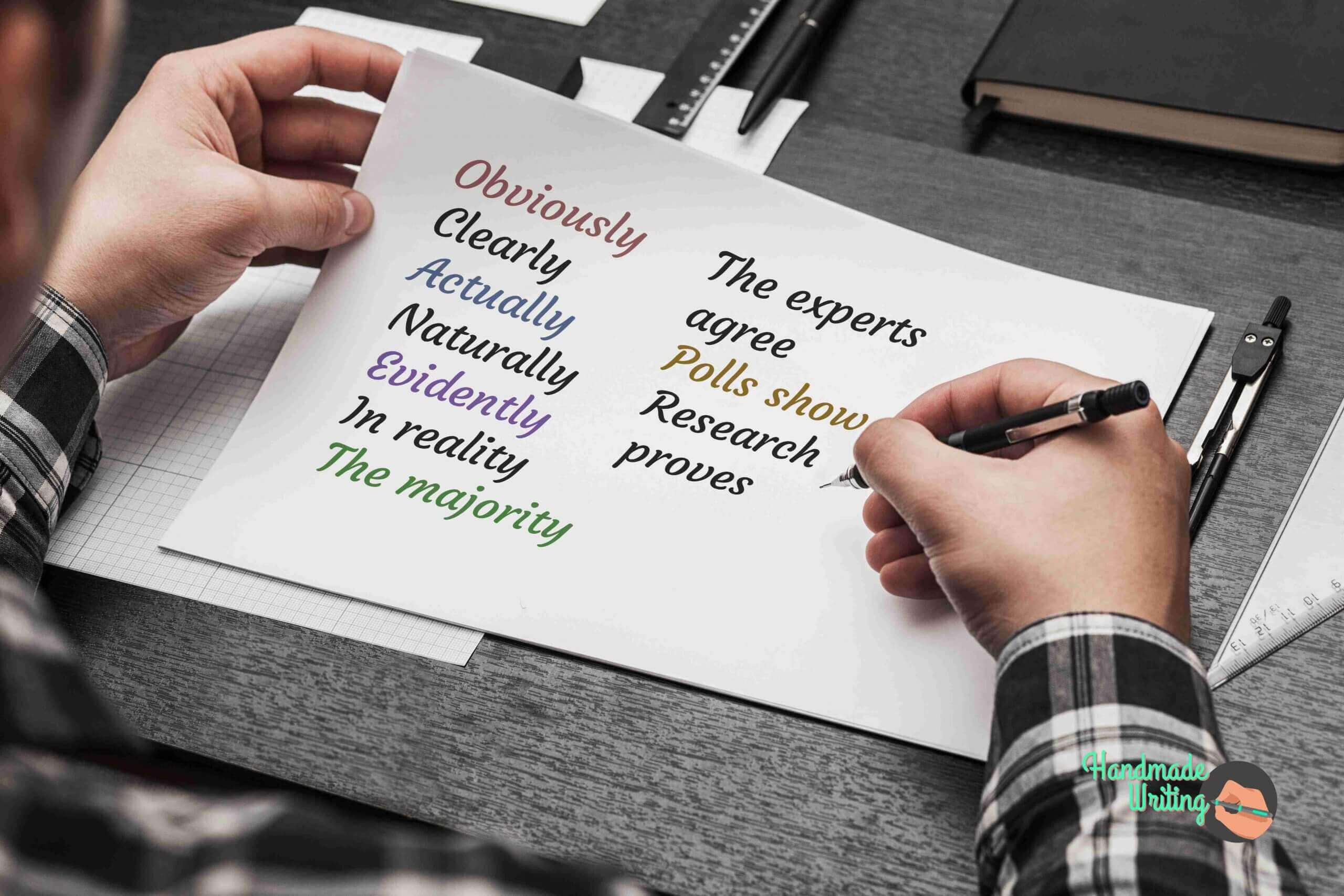

- Use strong persuasive language such as:

7. Sum up the conclusion

This paragraph signals the end of your essay. Want to know how to write a stellar conclusion? First, don’t introduce any new information. The cardinal rule of conclusion paragraphs is this: only discuss what’s already in the paper. Begin by restating the thesis; this reminds the audience about the essay’s goals and purpose. Next, review the main points covered in the body paragraphs.

Finally, here’s where the persuasive essay is a bit different than other academic essays: the call to action . In this type of essay, the conclusion should offer a call to action; if the reader agrees with the writer’s thesis then he or she should be willing to take some form of action. Set forth a call to action before ending the essay.

In order to create a proper conclusion, ask yourself a question: “what’s the takeaway for the reader?” Unlike the conclusion in an informative essay , the final section of your persuasive essay should emphasize your own view on the argument or issue.

Hints for a Great Conclusion

- Restate the thesis to link back to the introduction and remind the reader of your argument

- Review the paper’s stronger points to persuade the audience of a particular side

- End with a strong call to action

8. Revise your essay

Done the first draft? Then, it’s time to revise to make the essay stronger both content-wise and grammatically. Check out these great questions to help you:

- Does the essay begin with a hook that captures the reader’s interest?

- Does the introduction introduce all sides of the issue and provide background information?

- Does the introduction end with a clearly worded thesis statement?

- Does the essay clearly convey a specific position regarding the topic?

- Are the counter-arguments stated and refuted?

- Do the body paragraph offer relevant and reliable research to substantiate claims?

- Does the conclusion review the main points made within the paper?

- Are all sentences complete and grammatically correct?

Once you are through with the seven steps of persuasive essay writing, you can happily enjoy what you have accomplished. Feel free to submit the final piece to your professor/instructor.

Be sure to check the persuasive essay sample, completed by our essay writers . Link: Persuasive essay on Global Warming

Remember: writing is more of triathlon than a walk in the park. Just like a triathlon involves three key components, so too does writing: brainstorming, drafting, and revising. Begin your essay early and work through the various stages of writing to ensure that the final product is polished and grammatically flawless. If your school offers a Writing Center, use these resources.

It’s hard to catch one’s own mistakes, so ask a classmate or friend to review your paper. And don’t forget about your professional essay writing service! Skip the stress of beginning the assignment the night before it’s due and instead plan out your writing process and begin as soon as you receive the assignment. While content and grammar are the major players “gradewise”, don’t discount formatting. How you format your final paper is the first impression your professor will have of your work. Therefore, take the time to check the margins, font, headings, spacing, title page, and Works Cited page to ensure that they meet the professor’s expectations.

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

persuasive essay

What is persuasive essay definition, usage, and literary examples, persuasive essay definition.

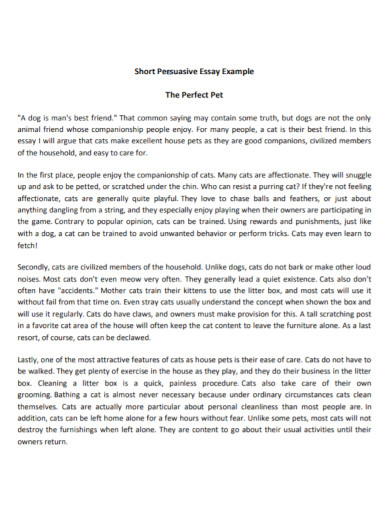

A persuasive essay (purr-SWEY-siv ESS-ey) is a composition in which the essayist’s goal is to persuade the reader to agree with their personal views on a debatable topic. A persuasive essay generally follows a five-paragraph model with a thesis, body paragraphs, and conclusion, and it offers evidential support using research and other persuasive techniques.

Persuasive Essay Topic Criteria

To write an effective persuasive essay, the essayist needs to ensure that the topic they choose is polemical, or debatable. If it isn’t, there’s no point in trying to persuade the reader.

For example, a persuasive essayist wouldn’t write about how honeybees make honey; this is a well-known fact, and there’s no opposition to sway. The essayist might, however, write an essay on why the reader shouldn’t put pesticides on their lawn, as it threatens the bee population and environmental health.

A topic should also be concrete enough that the essayist can research and find evidence to support their argument. Using the honeybee example, the essayist could cite statistics showing a decline in the honeybee population since the use of pesticides became prevalent in lawncare. This concrete evidence supports the essayist’s opinion.

Persuasive Essay Structure

The persuasive essay generally follows this five-paragraph model.

Introduction

The introduction includes the thesis, which is the main argument of the persuasive essay. A thesis for the essay on bees and pesticides might be: “Bees are essential to environmental health, and we should protect them by abstaining from the use of harmful lawn pesticides that dwindle the bee population.”

The introductory paragraph should also include some context and background info, like bees’ impact on crop pollination. This paragraph may also include common counterarguments, such as acknowledging how some people don’t believe pesticides harm bees.

Body Paragraphs

The body consists of two or more paragraphs and provides the main arguments. This is also where the essayist’s research and evidential support will appear. For example, the essayist might elaborate on the statistics they alluded to in the introductory paragraph to support their points. Many persuasive essays include a counterargument paragraph to refute conflicting opinions.

The final paragraph readdresses the thesis statement and reexamines the essayist’s main arguments.

Types of Persuasive Essays

Persuasive essays can take several forms. They can encourage the reader to change a habit or support a cause, ask the reader to oppose a certain practice, or compare two things and suggest that one is superior to the other. Here are thesis examples for each type, based on the bee example:

- Call for Support, Action, or Change : “Stop using pesticides on your lawns to save the environmentally essential bees.”

- Call for Opposition : “Oppose the big businesses that haven’t conducted environmental studies concerning bees and pesticides.”

- Superior Subject : “Natural lawn care is far superior to using harmful pesticides.”

The Three Elements of Persuasion

Aristotle first suggested that there were three main elements to persuading an audience: ethos, pathos, and logos. Essayists implement these same tactics to persuade their readers.

Ethos refers to the essayist’s character or authority; this could mean the writer’s name or credibility. For example, a writer might seem more trustworthy if they’ve frequently written on a subject, have a degree related to the subject, or have extensive experience concerning a subject. A writer can also refer to the opinions of other experts, such as a beekeeper who believes pesticides are harming the bee population.

Pathos is an argument that uses the reader’s emotions and morality to persuade them. An argument that uses pathos might point to the number of bees that have died and what that suggests for food production: “If crop production decreases, it will be impoverished families that suffer, with perhaps more poor children having to go hungry.” This argument might make the reader empathetic to the plight of starving children and encourage them to take action against pesticide pollution.

The logos part of the essay uses logic and reason to persuade the reader. This includes the essayist’s research and whatever evidence they’ve collected to support their arguments, such as statistics.

Terms Related to Persuasive Essays

Argumentative Essays

While persuasive essays may use logic and research to support the essayist’s opinions, argumentative essays are more solely based on research and refrain from using emotional arguments. Argumentative essays are also more likely to include in-depth information on counterarguments.

Persuasive Speeches

Persuasive essays and persuasive speeches are similar in intent, but they differ in terms of format, delivery, emphasis, and tone .

In a speech, the speaker can use gestures and inflections to emphasize their points, so the delivery is almost as important as the information a speech provides. A speech requires less structure than an essay, though the repetition of ideas is often necessary to ensure that the audience is absorbing the material. Additionally, a speech relies more heavily on emotion, as the speaker must hold the reader’s attention and interest. In Queen Elizabeth I’s “Tilbury Speech,” for example, she addresses her audience in a personable and highly emotional way: “My loving people, We have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit our selves to armed multitudes for fear of treachery; but I assure you I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people. Let tyrants fear.”

Examples of Persuasive Essay

1. Martin Luther King, Jr., “Letter From Birmingham Jail”

Dr. King directs his essay at the Alabama clergymen who opposed his call for protests. The clergymen suggested that King had no business being in Alabama, that he shouldn’t oppose some of the more respectful segregationists, and that he has poor timing. However, here, King attempts to persuade the men that his actions are just:

I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eight century B.C. left their villages and carried their ‘thus saith the Lord’ far beyond the boundaries of their hometowns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the Greco-Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my hometown.

Here, King is invoking the ethos of Biblical figures who the clergymen would’ve respected. By comparing himself to Paul, he’s claiming to be a disciple spreading the “gospel of freedom” rather than an outsider butting into Alabama’s affairs.

2. Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of Commons”

Hardin argues that a society that shares resources is apt to overuse those resources as the population increases. He attempts to persuade readers that the human population’s growth should be regulated for the sake of preserving resources:

The National Parks present another instance of the working out of the tragedy of commons. At present, they are open to all, without limit. The parks themselves are limited in extent—there is only one Yosemite Valley—whereas population seems to grow without limit. The values that visitors seek in the parks are steadily eroded. Plainly, we must soon cease to treat the parks as commons, or they will be of no value to anyone.

In this excerpt, Harden uses an example that appeals to the reader’s logic. If the human population continues to rise, causing park visitors to increase, parks will continue to erode until there’s nothing left.

Further Resources on Persuasive Essays

We at SuperSummary offer excellent resources for penning your own essays .

Find a list of famous persuasive speeches at Highspark.co .

Read up on the elements of persuasion at the American Management Association website.

Related Terms

- Argumentative Essay

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.9 Persuasion

Learning objectives.

- Determine the purpose and structure of persuasion in writing.

- Identify bias in writing.

- Assess various rhetorical devices.

- Distinguish between fact and opinion.

- Understand the importance of visuals to strengthen arguments.

- Write a persuasive essay.

The Purpose of Persuasive Writing

The purpose of persuasion in writing is to convince, motivate, or move readers toward a certain point of view, or opinion. The act of trying to persuade automatically implies more than one opinion on the subject can be argued.

The idea of an argument often conjures up images of two people yelling and screaming in anger. In writing, however, an argument is very different. An argument is a reasoned opinion supported and explained by evidence. To argue in writing is to advance knowledge and ideas in a positive way. Written arguments often fail when they employ ranting rather than reasoning.

Most of us feel inclined to try to win the arguments we engage in. On some level, we all want to be right, and we want others to see the error of their ways. More times than not, however, arguments in which both sides try to win end up producing losers all around. The more productive approach is to persuade your audience to consider your opinion as a valid one, not simply the right one.

The Structure of a Persuasive Essay

The following five features make up the structure of a persuasive essay:

- Introduction and thesis

- Opposing and qualifying ideas

- Strong evidence in support of claim

- Style and tone of language

- A compelling conclusion

Creating an Introduction and Thesis

The persuasive essay begins with an engaging introduction that presents the general topic. The thesis typically appears somewhere in the introduction and states the writer’s point of view.

Avoid forming a thesis based on a negative claim. For example, “The hourly minimum wage is not high enough for the average worker to live on.” This is probably a true statement, but persuasive arguments should make a positive case. That is, the thesis statement should focus on how the hourly minimum wage is low or insufficient.

Acknowledging Opposing Ideas and Limits to Your Argument

Because an argument implies differing points of view on the subject, you must be sure to acknowledge those opposing ideas. Avoiding ideas that conflict with your own gives the reader the impression that you may be uncertain, fearful, or unaware of opposing ideas. Thus it is essential that you not only address counterarguments but also do so respectfully.

Try to address opposing arguments earlier rather than later in your essay. Rhetorically speaking, ordering your positive arguments last allows you to better address ideas that conflict with your own, so you can spend the rest of the essay countering those arguments. This way, you leave your reader thinking about your argument rather than someone else’s. You have the last word.

Acknowledging points of view different from your own also has the effect of fostering more credibility between you and the audience. They know from the outset that you are aware of opposing ideas and that you are not afraid to give them space.

It is also helpful to establish the limits of your argument and what you are trying to accomplish. In effect, you are conceding early on that your argument is not the ultimate authority on a given topic. Such humility can go a long way toward earning credibility and trust with an audience. Audience members will know from the beginning that you are a reasonable writer, and audience members will trust your argument as a result. For example, in the following concessionary statement, the writer advocates for stricter gun control laws, but she admits it will not solve all of our problems with crime:

Although tougher gun control laws are a powerful first step in decreasing violence in our streets, such legislation alone cannot end these problems since guns are not the only problem we face.

Such a concession will be welcome by those who might disagree with this writer’s argument in the first place. To effectively persuade their readers, writers need to be modest in their goals and humble in their approach to get readers to listen to the ideas. See Table 10.5 “Phrases of Concession” for some useful phrases of concession.

Table 10.5 Phrases of Concession

Try to form a thesis for each of the following topics. Remember the more specific your thesis, the better.

- Foreign policy

- Television and advertising

- Stereotypes and prejudice

- Gender roles and the workplace

- Driving and cell phones

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers. Choose the thesis statement that most interests you and discuss why.

Bias in Writing

Everyone has various biases on any number of topics. For example, you might have a bias toward wearing black instead of brightly colored clothes or wearing jeans rather than formal wear. You might have a bias toward working at night rather than in the morning, or working by deadlines rather than getting tasks done in advance. These examples identify minor biases, of course, but they still indicate preferences and opinions.

Handling bias in writing and in daily life can be a useful skill. It will allow you to articulate your own points of view while also defending yourself against unreasonable points of view. The ideal in persuasive writing is to let your reader know your bias, but do not let that bias blind you to the primary components of good argumentation: sound, thoughtful evidence and a respectful and reasonable address of opposing sides.

The strength of a personal bias is that it can motivate you to construct a strong argument. If you are invested in the topic, you are more likely to care about the piece of writing. Similarly, the more you care, the more time and effort you are apt to put forth and the better the final product will be.

The weakness of bias is when the bias begins to take over the essay—when, for example, you neglect opposing ideas, exaggerate your points, or repeatedly insert yourself ahead of the subject by using I too often. Being aware of all three of these pitfalls will help you avoid them.

The Use of I in Writing

The use of I in writing is often a topic of debate, and the acceptance of its usage varies from instructor to instructor. It is difficult to predict the preferences for all your present and future instructors, but consider the effects it can potentially have on your writing.

Be mindful of the use of I in your writing because it can make your argument sound overly biased. There are two primary reasons:

- Excessive repetition of any word will eventually catch the reader’s attention—and usually not in a good way. The use of I is no different.

- The insertion of I into a sentence alters not only the way a sentence might sound but also the composition of the sentence itself. I is often the subject of a sentence. If the subject of the essay is supposed to be, say, smoking, then by inserting yourself into the sentence, you are effectively displacing the subject of the essay into a secondary position. In the following example, the subject of the sentence is underlined:

Smoking is bad.

I think smoking is bad.

In the first sentence, the rightful subject, smoking , is in the subject position in the sentence. In the second sentence, the insertion of I and think replaces smoking as the subject, which draws attention to I and away from the topic that is supposed to be discussed. Remember to keep the message (the subject) and the messenger (the writer) separate.

Developing Sound Arguments

Does my essay contain the following elements?

- An engaging introduction

- A reasonable, specific thesis that is able to be supported by evidence

- A varied range of evidence from credible sources

- Respectful acknowledgement and explanation of opposing ideas

- A style and tone of language that is appropriate for the subject and audience

- Acknowledgement of the argument’s limits

- A conclusion that will adequately summarize the essay and reinforce the thesis

Fact and Opinion

Facts are statements that can be definitely proven using objective data. The statement that is a fact is absolutely valid. In other words, the statement can be pronounced as true or false. For example, 2 + 2 = 4. This expression identifies a true statement, or a fact, because it can be proved with objective data.

Opinions are personal views, or judgments. An opinion is what an individual believes about a particular subject. However, an opinion in argumentation must have legitimate backing; adequate evidence and credibility should support the opinion. Consider the credibility of expert opinions. Experts in a given field have the knowledge and credentials to make their opinion meaningful to a larger audience.

For example, you seek the opinion of your dentist when it comes to the health of your gums, and you seek the opinion of your mechanic when it comes to the maintenance of your car. Both have knowledge and credentials in those respective fields, which is why their opinions matter to you. But the authority of your dentist may be greatly diminished should he or she offer an opinion about your car, and vice versa.

In writing, you want to strike a balance between credible facts and authoritative opinions. Relying on one or the other will likely lose more of your audience than it gains.

The word prove is frequently used in the discussion of persuasive writing. Writers may claim that one piece of evidence or another proves the argument, but proving an argument is often not possible. No evidence proves a debatable topic one way or the other; that is why the topic is debatable. Facts can be proved, but opinions can only be supported, explained, and persuaded.

On a separate sheet of paper, take three of the theses you formed in Note 10.94 “Exercise 1” , and list the types of evidence you might use in support of that thesis.

Using the evidence you provided in support of the three theses in Note 10.100 “Exercise 2” , come up with at least one counterargument to each. Then write a concession statement, expressing the limits to each of your three arguments.

Using Visual Elements to Strengthen Arguments

Adding visual elements to a persuasive argument can often strengthen its persuasive effect. There are two main types of visual elements: quantitative visuals and qualitative visuals.

Quantitative visuals present data graphically. They allow the audience to see statistics spatially. The purpose of using quantitative visuals is to make logical appeals to the audience. For example, sometimes it is easier to understand the disparity in certain statistics if you can see how the disparity looks graphically. Bar graphs, pie charts, Venn diagrams, histograms, and line graphs are all ways of presenting quantitative data in spatial dimensions.

Qualitative visuals present images that appeal to the audience’s emotions. Photographs and pictorial images are examples of qualitative visuals. Such images often try to convey a story, and seeing an actual example can carry more power than hearing or reading about the example. For example, one image of a child suffering from malnutrition will likely have more of an emotional impact than pages dedicated to describing that same condition in writing.

Writing at Work

When making a business presentation, you typically have limited time to get across your idea. Providing visual elements for your audience can be an effective timesaving tool. Quantitative visuals in business presentations serve the same purpose as they do in persuasive writing. They should make logical appeals by showing numerical data in a spatial design. Quantitative visuals should be pictures that might appeal to your audience’s emotions. You will find that many of the rhetorical devices used in writing are the same ones used in the workplace. For more information about visuals in presentations, see Chapter 14 “Creating Presentations: Sharing Your Ideas” .

Writing a Persuasive Essay

Choose a topic that you feel passionate about. If your instructor requires you to write about a specific topic, approach the subject from an angle that interests you. Begin your essay with an engaging introduction. Your thesis should typically appear somewhere in your introduction.

Start by acknowledging and explaining points of view that may conflict with your own to build credibility and trust with your audience. Also state the limits of your argument. This too helps you sound more reasonable and honest to those who may naturally be inclined to disagree with your view. By respectfully acknowledging opposing arguments and conceding limitations to your own view, you set a measured and responsible tone for the essay.

Make your appeals in support of your thesis by using sound, credible evidence. Use a balance of facts and opinions from a wide range of sources, such as scientific studies, expert testimony, statistics, and personal anecdotes. Each piece of evidence should be fully explained and clearly stated.

Make sure that your style and tone are appropriate for your subject and audience. Tailor your language and word choice to these two factors, while still being true to your own voice.

Finally, write a conclusion that effectively summarizes the main argument and reinforces your thesis. See Chapter 15 “Readings: Examples of Essays” to read a sample persuasive essay.

Choose one of the topics you have been working on throughout this section. Use the thesis, evidence, opposing argument, and concessionary statement as the basis for writing a full persuasive essay. Be sure to include an engaging introduction, clear explanations of all the evidence you present, and a strong conclusion.

Key Takeaways

- The purpose of persuasion in writing is to convince or move readers toward a certain point of view, or opinion.

- An argument is a reasoned opinion supported and explained by evidence. To argue, in writing, is to advance knowledge and ideas in a positive way.

- A thesis that expresses the opinion of the writer in more specific terms is better than one that is vague.

- It is essential that you not only address counterarguments but also do so respectfully.

- It is also helpful to establish the limits of your argument and what you are trying to accomplish through a concession statement.

- To persuade a skeptical audience, you will need to use a wide range of evidence. Scientific studies, opinions from experts, historical precedent, statistics, personal anecdotes, and current events are all types of evidence that you might use in explaining your point.

- Make sure that your word choice and writing style is appropriate for both your subject and your audience.

- You should let your reader know your bias, but do not let that bias blind you to the primary components of good argumentation: sound, thoughtful evidence and respectfully and reasonably addressing opposing ideas.

- You should be mindful of the use of I in your writing because it can make your argument sound more biased than it needs to.

- Facts are statements that can be proven using objective data.

- Opinions are personal views, or judgments, that cannot be proven.

- In writing, you want to strike a balance between credible facts and authoritative opinions.

- Quantitative visuals present data graphically. The purpose of using quantitative visuals is to make logical appeals to the audience.

- Qualitative visuals present images that appeal to the audience’s emotions.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

How to Write a Persuasive Essay (This Convinced My Professor!)

.png)

Table of contents

Meredith Sell

You can make your essay more persuasive by getting straight to the point.

In fact, that's exactly what we did here, and that's just the first tip of this guide. Throughout this guide, we share the steps needed to prove an argument and create a persuasive essay.

This AI tool helps you improve your essay > This AI tool helps you improve your essay >

Key takeaways: - Proven process to make any argument persuasive - 5-step process to structure arguments - How to use AI to formulate and optimize your essay

Why is being persuasive so difficult?

"Write an essay that persuades the reader of your opinion on a topic of your choice."

You might be staring at an assignment description just like this 👆from your professor. Your computer is open to a blank document, the cursor blinking impatiently. Do I even have opinions?

The persuasive essay can be one of the most intimidating academic papers to write: not only do you need to identify a narrow topic and research it, but you also have to come up with a position on that topic that you can back up with research while simultaneously addressing different viewpoints.

That’s a big ask. And let’s be real: most opinion pieces in major news publications don’t fulfill these requirements.

The upside? By researching and writing your own opinion, you can learn how to better formulate not only an argument but the actual positions you decide to hold.

Here, we break down exactly how to write a persuasive essay. We’ll start by taking a step that’s key for every piece of writing—defining the terms.

What Is a Persuasive Essay?

A persuasive essay is exactly what it sounds like: an essay that persuades . Over the course of several paragraphs or pages, you’ll use researched facts and logic to convince the reader of your opinion on a particular topic and discredit opposing opinions.

While you’ll spend some time explaining the topic or issue in question, most of your essay will flesh out your viewpoint and the evidence that supports it.

The 5 Must-Have Steps of a Persuasive Essay

If you’re intimidated by the idea of writing an argument, use this list to break your process into manageable chunks. Tackle researching and writing one element at a time, and then revise your essay so that it flows smoothly and coherently with every component in the optimal place.

1. A topic or issue to argue

This is probably the hardest step. You need to identify a topic or issue that is narrow enough to cover in the length of your piece—and is also arguable from more than one position. Your topic must call for an opinion , and not be a simple fact .

It might be helpful to walk through this process:

- Identify a random topic