How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

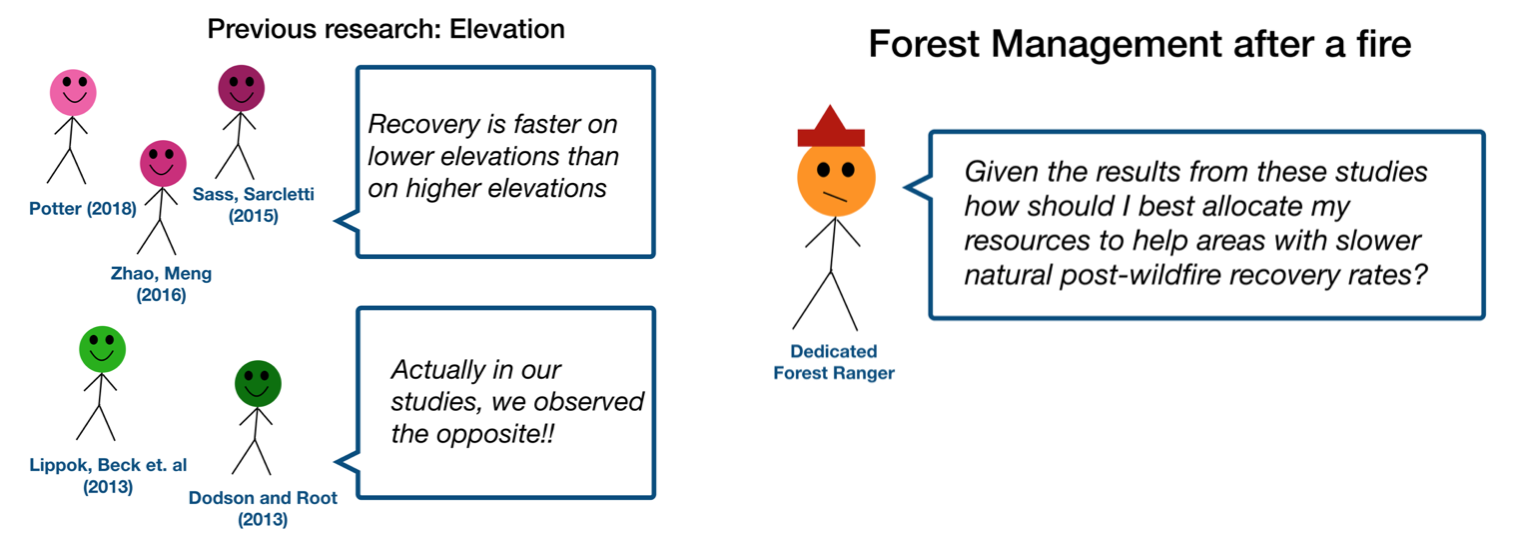

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications . If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 31 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Illustration by James Round

How to plan a research project

Whether for a paper or a thesis, define your question, review the work of others – and leave yourself open to discovery.

by Brooke Harrington + BIO

is professor of sociology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Her research has won international awards both for scholarly quality and impact on public life. She has published dozens of articles and three books, most recently the bestseller Capital without Borders (2016), now translated into five languages.

Edited by Sam Haselby

Need to know

‘When curiosity turns to serious matters, it’s called research.’ – From Aphorisms (1880-1905) by Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach

Planning research projects is a time-honoured intellectual exercise: one that requires both creativity and sharp analytical skills. The purpose of this Guide is to make the process systematic and easy to understand. While there is a great deal of freedom and discovery involved – from the topics you choose, to the data and methods you apply – there are also some norms and constraints that obtain, no matter what your academic level or field of study. For those in high school through to doctoral students, and from art history to archaeology, research planning involves broadly similar steps, including: formulating a question, developing an argument or predictions based on previous research, then selecting the information needed to answer your question.

Some of this might sound self-evident but, as you’ll find, research requires a different way of approaching and using information than most of us are accustomed to in everyday life. That is why I include orienting yourself to knowledge-creation as an initial step in the process. This is a crucial and underappreciated phase in education, akin to making the transition from salaried employment to entrepreneurship: suddenly, you’re on your own, and that requires a new way of thinking about your work.

What follows is a distillation of what I’ve learned about this process over 27 years as a professional social scientist. It reflects the skills that my own professors imparted in the sociology doctoral programme at Harvard, as well as what I learned later on as a research supervisor for Ivy League PhD and MA students, and then as the author of award-winning scholarly books and articles. It can be adapted to the demands of both short projects (such as course term papers) and long ones, such as a thesis.

At its simplest, research planning involves the four distinct steps outlined below: orienting yourself to knowledge-creation; defining your research question; reviewing previous research on your question; and then choosing relevant data to formulate your own answers. Because the focus of this Guide is on planning a research project, as opposed to conducting a research project, this section won’t delve into the details of data-collection or analysis; those steps happen after you plan the project. In addition, the topic is vast: year-long doctoral courses are devoted to data and analysis. Instead, the fourth part of this section will outline some basic strategies you could use in planning a data-selection and analysis process appropriate to your research question.

Step 1: Orient yourself

Planning and conducting research requires you to make a transition, from thinking like a consumer of information to thinking like a producer of information. That sounds simple, but it’s actually a complex task. As a practical matter, this means putting aside the mindset of a student, which treats knowledge as something created by other people. As students, we are often passive receivers of knowledge: asked to do a specified set of readings, then graded on how well we reproduce what we’ve read.

Researchers, however, must take on an active role as knowledge producers . Doing research requires more of you than reading and absorbing what other people have written: you have to engage in a dialogue with it. That includes arguing with previous knowledge and perhaps trying to show that ideas we have accepted as given are actually wrong or incomplete. For example, rather than simply taking in the claims of an author you read, you’ll need to draw out the implications of those claims: if what the author is saying is true, what else does that suggest must be true? What predictions could you make based on the author’s claims?

In other words, rather than treating a reading as a source of truth – even if it comes from a revered source, such as Plato or Marie Curie – this orientation step asks you to treat the claims you read as provisional and subject to interrogation. That is one of the great pieces of wisdom that science and philosophy can teach us: that the biggest advances in human understanding have been made not by being correct about trivial things, but by being wrong in an interesting way . For example, Albert Einstein was wrong about quantum mechanics, but his arguments about it with his fellow physicist Niels Bohr have led to some of the biggest breakthroughs in science, even a century later.

Step 2: Define your research question

Students often give this step cursory attention, but experienced researchers know that formulating a good question is sometimes the most difficult part of the research planning process. That is because the precise language of the question frames the rest of the project. It’s therefore important to pose the question carefully, in a way that’s both possible to answer and likely to yield interesting results. Of course, you must choose a question that interests you, but that’s only the beginning of what’s likely to be an iterative process: most researchers come back to this step repeatedly, modifying their questions in light of previous research, resource limitations and other considerations.

Researchers face limits in terms of time and money. They, like everyone else, have to pose research questions that they can plausibly answer given the constraints they face. For example, it would be inadvisable to frame a project around the question ‘What are the roots of the Arab-Israeli conflict?’ if you have only a week to develop an answer and no background on that topic. That’s not to limit your imagination: you can come up with any question you’d like. But it typically does require some creativity to frame a question that you can answer well – that is, by investigating thoroughly and providing new insights – within the limits you face.

In addition to being interesting to you, and feasible within your resource constraints, the third and most important characteristic of a ‘good’ research topic is whether it allows you to create new knowledge. It might turn out that your question has already been asked and answered to your satisfaction: if so, you’ll find out in the next step of this process. On the other hand, you might come up with a research question that hasn’t been addressed previously. Before you get too excited about breaking uncharted ground, consider this: a lot of potentially researchable questions haven’t been studied for good reason ; they might have answers that are trivial or of very limited interest. This could include questions such as ‘Why does the area of a circle equal π r²?’ or ‘Did winter conditions affect Napoleon’s plans to invade Russia?’ Of course, you might be able to make the argument that a seemingly trivial question is actually vitally important, but you must be prepared to back that up with convincing evidence. The exercise in the ‘Learn More’ section below will help you think through some of these issues.

Finally, scholarly research questions must in some way lead to new and distinctive insights. For example, lots of people have studied gender roles in sports teams; what can you ask that hasn’t been asked before? Reinventing the wheel is the number-one no-no in this endeavour. That’s why the next step is so important: reviewing previous research on your topic. Depending on what you find in that step, you might need to revise your research question; iterating between your question and the existing literature is a normal process. But don’t worry: it doesn’t go on forever. In fact, the iterations taper off – and your research question stabilises – as you develop a firm grasp of the current state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 3: Review previous research

In academic research, from articles to books, it’s common to find a section called a ‘literature review’. The purpose of that section is to describe the state of the art in knowledge on the research question that a project has posed. It demonstrates that researchers have thoroughly and systematically reviewed the relevant findings of previous studies on their topic, and that they have something novel to contribute.

Your own research project should include something like this, even if it’s a high-school term paper. In the research planning process, you’ll want to list at least half a dozen bullet points stating the major findings on your topic by other people. In relation to those findings, you should be able to specify where your project could provide new and necessary insights. There are two basic rhetorical positions one can take in framing the novelty-plus-importance argument required of academic research:

- Position 1 requires you to build on or extend a set of existing ideas; that means saying something like: ‘Person A has argued that X is true about gender; this implies Y, which has not yet been tested. My project will test Y, and if I find evidence to support it, that will change the way we understand gender.’

- Position 2 is to argue that there is a gap in existing knowledge, either because previous research has reached conflicting conclusions or has failed to consider something important. For example, one could say that research on middle schoolers and gender has been limited by being conducted primarily in coeducational environments, and that findings might differ dramatically if research were conducted in more schools where the student body was all-male or all-female.

Your overall goal in this step of the process is to show that your research will be part of a larger conversation: that is, how your project flows from what’s already known, and how it advances, extends or challenges that existing body of knowledge. That will be the contribution of your project, and it constitutes the motivation for your research.

Two things are worth mentioning about your search for sources of relevant previous research. First, you needn’t look only at studies on your precise topic. For example, if you want to study gender-identity formation in schools, you shouldn’t restrict yourself to studies of schools; the empirical setting (schools) is secondary to the larger social process that interests you (how people form gender identity). That process occurs in many different settings, so cast a wide net. Second, be sure to use legitimate sources – meaning publications that have been through some sort of vetting process, whether that involves peer review (as with academic journal articles you might find via Google Scholar) or editorial review (as you’d find in well-known mass media publications, such as The Economist or The Washington Post ). What you’ll want to avoid is using unvetted sources such as personal blogs or Wikipedia. Why? Because anybody can write anything in those forums, and there is no way to know – unless you’re already an expert – if the claims you find there are accurate. Often, they’re not.

Step 4: Choose your data and methods

Whatever your research question is, eventually you’ll need to consider which data source and analytical strategy are most likely to provide the answers you’re seeking. One starting point is to consider whether your question would be best addressed by qualitative data (such as interviews, observations or historical records), quantitative data (such as surveys or census records) or some combination of both. Your ideas about data sources will, in turn, suggest options for analytical methods.

You might need to collect your own data, or you might find everything you need readily available in an existing dataset someone else has created. A great place to start is with a research librarian: university libraries always have them and, at public universities, those librarians can work with the public, including people who aren’t affiliated with the university. If you don’t happen to have a public university and its library close at hand, an ordinary public library can still be a good place to start: the librarians are often well versed in accessing data sources that might be relevant to your study, such as the census, or historical archives, or the Survey of Consumer Finances.

Because your task at this point is to plan research, rather than conduct it, the purpose of this step is not to commit you irrevocably to a course of action. Instead, your goal here is to think through a feasible approach to answering your research question. You’ll need to find out, for example, whether the data you want exist; if not, do you have a realistic chance of gathering the data yourself, or would it be better to modify your research question? In terms of analysis, would your strategy require you to apply statistical methods? If so, do you have those skills? If not, do you have time to learn them, or money to hire a research assistant to run the analysis for you?

Please be aware that qualitative methods in particular are not the casual undertaking they might appear to be. Many people make the mistake of thinking that only quantitative data and methods are scientific and systematic, while qualitative methods are just a fancy way of saying: ‘I talked to some people, read some old newspapers, and drew my own conclusions.’ Nothing could be further from the truth. In the final section of this guide, you’ll find some links to resources that will provide more insight on standards and procedures governing qualitative research, but suffice it to say: there are rules about what constitutes legitimate evidence and valid analytical procedure for qualitative data, just as there are for quantitative data.

Circle back and consider revising your initial plans

As you work through these four steps in planning your project, it’s perfectly normal to circle back and revise. Research planning is rarely a linear process. It’s also common for new and unexpected avenues to suggest themselves. As the sociologist Thorstein Veblen wrote in 1908 : ‘The outcome of any serious research can only be to make two questions grow where only one grew before.’ That’s as true of research planning as it is of a completed project. Try to enjoy the horizons that open up for you in this process, rather than becoming overwhelmed; the four steps, along with the two exercises that follow, will help you focus your plan and make it manageable.

Key points – How to plan a research project

- Planning a research project is essential no matter your academic level or field of study. There is no one ‘best’ way to design research, but there are certain guidelines that can be helpfully applied across disciplines.

- Orient yourself to knowledge-creation. Make the shift from being a consumer of information to being a producer of information.

- Define your research question. Your question frames the rest of your project, sets the scope, and determines the kinds of answers you can find.

- Review previous research on your question. Survey the existing body of relevant knowledge to ensure that your research will be part of a larger conversation.

- Choose your data and methods. For instance, will you be collecting qualitative data, via interviews, or numerical data, via surveys?

- Circle back and consider revising your initial plans. Expect your research question in particular to undergo multiple rounds of refinement as you learn more about your topic.

Good research questions tend to beget more questions. This can be frustrating for those who want to get down to business right away. Try to make room for the unexpected: this is usually how knowledge advances. Many of the most significant discoveries in human history have been made by people who were looking for something else entirely. There are ways to structure your research planning process without over-constraining yourself; the two exercises below are a start, and you can find further methods in the Links and Books section.

The following exercise provides a structured process for advancing your research project planning. After completing it, you’ll be able to do the following:

- describe clearly and concisely the question you’ve chosen to study

- summarise the state of the art in knowledge about the question, and where your project could contribute new insight

- identify the best strategy for gathering and analysing relevant data

In other words, the following provides a systematic means to establish the building blocks of your research project.

Exercise 1: Definition of research question and sources

This exercise prompts you to select and clarify your general interest area, develop a research question, and investigate sources of information. The annotated bibliography will also help you refine your research question so that you can begin the second assignment, a description of the phenomenon you wish to study.

Jot down a few bullet points in response to these two questions, with the understanding that you’ll probably go back and modify your answers as you begin reading other studies relevant to your topic:

- What will be the general topic of your paper?

- What will be the specific topic of your paper?

b) Research question(s)

Use the following guidelines to frame a research question – or questions – that will drive your analysis. As with Part 1 above, you’ll probably find it necessary to change or refine your research question(s) as you complete future assignments.

- Your question should be phrased so that it can’t be answered with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

- Your question should have more than one plausible answer.

- Your question should draw relationships between two or more concepts; framing the question in terms of How? or What? often works better than asking Why ?

c) Annotated bibliography

Most or all of your background information should come from two sources: scholarly books and journals, or reputable mass media sources. You might be able to access journal articles electronically through your library, using search engines such as JSTOR and Google Scholar. This can save you a great deal of time compared with going to the library in person to search periodicals. General news sources, such as those accessible through LexisNexis, are acceptable, but should be cited sparingly, since they don’t carry the same level of credibility as scholarly sources. As discussed above, unvetted sources such as blogs and Wikipedia should be avoided, because the quality of the information they provide is unreliable and often misleading.

To create an annotated bibliography, provide the following information for at least 10 sources relevant to your specific topic, using the format suggested below.

Name of author(s):

Publication date:

Title of book, chapter, or article:

If a chapter or article, title of journal or book where they appear:

Brief description of this work, including main findings and methods ( c 75 words):

Summary of how this work contributes to your project ( c 75 words):

Brief description of the implications of this work ( c 25 words):

Identify any gap or controversy in knowledge this work points up, and how your project could address those problems ( c 50 words):

Exercise 2: Towards an analysis

Develop a short statement ( c 250 words) about the kind of data that would be useful to address your research question, and how you’d analyse it. Some questions to consider in writing this statement include:

- What are the central concepts or variables in your project? Offer a brief definition of each.

- Do any data sources exist on those concepts or variables, or would you need to collect data?

- Of the analytical strategies you could apply to that data, which would be the most appropriate to answer your question? Which would be the most feasible for you? Consider at least two methods, noting their advantages or disadvantages for your project.

Links & books

One of the best texts ever written about planning and executing research comes from a source that might be unexpected: a 60-year-old work on urban planning by a self-trained scholar. The classic book The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) by Jane Jacobs (available complete and free of charge via this link ) is worth reading in its entirety just for the pleasure of it. But the final 20 pages – a concluding chapter titled ‘The Kind of Problem a City Is’ – are really about the process of thinking through and investigating a problem. Highly recommended as a window into the craft of research.

Jacobs’s text references an essay on advancing human knowledge by the mathematician Warren Weaver. At the time, Weaver was director of the Rockefeller Foundation, in charge of funding basic research in the natural and medical sciences. Although the essay is titled ‘A Quarter Century in the Natural Sciences’ (1960) and appears at first blush to be merely a summation of one man’s career, it turns out to be something much bigger and more interesting: a meditation on the history of human beings seeking answers to big questions about the world. Weaver goes back to the 17th century to trace the origins of systematic research thinking, with enthusiasm and vivid anecdotes that make the process come alive. The essay is worth reading in its entirety, and is available free of charge via this link .

For those seeking a more in-depth, professional-level discussion of the logic of research design, the political scientist Harvey Starr provides insight in a compact format in the article ‘Cumulation from Proper Specification: Theory, Logic, Research Design, and “Nice” Laws’ (2005). Starr reviews the ‘research triad’, consisting of the interlinked considerations of formulating a question, selecting relevant theories and applying appropriate methods. The full text of the article, published in the scholarly journal Conflict Management and Peace Science , is available, free of charge, via this link .

Finally, the book Getting What You Came For (1992) by Robert Peters is not only an outstanding guide for anyone contemplating graduate school – from the application process onward – but it also includes several excellent chapters on planning and executing research, applicable across a wide variety of subject areas. It was an invaluable resource for me 25 years ago, and it remains in print with good reason; I recommend it to all my students, particularly Chapter 16 (‘The Thesis Topic: Finding It’), Chapter 17 (‘The Thesis Proposal’) and Chapter 18 (‘The Thesis: Writing It’).

Goals and motivation

How to do mental time travel

Feeling overwhelmed by the present moment? Find a connection to the longer view and a wiser perspective on what matters

by Richard Fisher

How to cope with climate anxiety

It’s normal to feel troubled by the climate crisis. These practices can help keep your response manageable and constructive

by Lucia Tecuta

Emerging therapies

How to use cooking as a form of therapy

No matter your culinary skills, spend some reflective time in the kitchen to nourish and renew your sense of self

by Charlotte Hastings

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

How to Get Started With a Research Project

Last Updated: October 3, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Chris Hadley, PhD . Chris Hadley, PhD is part of the wikiHow team and works on content strategy and data and analytics. Chris Hadley earned his PhD in Cognitive Psychology from UCLA in 2006. Chris' academic research has been published in numerous scientific journals. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 312,500 times.

You'll be required to undertake and complete research projects throughout your academic career and even, in many cases, as a member of the workforce. Don't worry if you feel stuck or intimidated by the idea of a research project, with care and dedication, you can get the project done well before the deadline!

Development and Foundation

- Don't hesitate while writing down ideas. You'll end up with some mental noise on the paper – silly or nonsensical phrases that your brain just pushes out. That's fine. Think of it as sweeping the cobwebs out of your attic. After a minute or two, better ideas will begin to form (and you might have a nice little laugh at your own expense in the meantime).

- Some instructors will even provide samples of previously successful topics if you ask for them. Just be careful that you don't end up stuck with an idea you want to do, but are afraid to do because you know someone else did it before.

- For example, if your research topic is “urban poverty,” you could look at that topic across ethnic or sexual lines, but you could also look into corporate wages, minimum wage laws, the cost of medical benefits, the loss of unskilled jobs in the urban core, and on and on. You could also try comparing and contrasting urban poverty with suburban or rural poverty, and examine things that might be different about both areas, such as diet and exercise levels, or air pollution.

- Think in terms of questions you want answered. A good research project should collect information for the purpose of answering (or at least attempting to answer) a question. As you review and interconnect topics, you'll think of questions that don't seem to have clear answers yet. These questions are your research topics.

- Don't limit yourself to libraries and online databases. Think in terms of outside resources as well: primary sources, government agencies, even educational TV programs. If you want to know about differences in animal population between public land and an Indian reservation, call the reservation and see if you can speak to their department of fish and wildlife.

- If you're planning to go ahead with original research, that's great – but those techniques aren't covered in this article. Instead, speak with qualified advisors and work with them to set up a thorough, controlled, repeatable process for gathering information.

- If your plan comes down to “researching the topic,” and there aren't any more specific things you can say about it, write down the types of sources you plan to use instead: books (library or private?), magazines (which ones?), interviews, and so on. Your preliminary research should have given you a solid idea of where to begin.

Expanding Your Idea with Research

- It's generally considered more convincing to source one item from three different authors who all agree on it than it is to rely too heavily on one book. Go for quantity at least as much as quality. Be sure to check citations, endnotes, and bibliographies to get more potential sources (and see whether or not all your authors are just quoting the same, older author).

- Writing down your sources and any other relevant details (such as context) around your pieces of information right now will save you lots of trouble in the future.

- Use many different queries to get the database results you want. If one phrasing or a particular set of words doesn't yield useful results, try rephrasing it or using synonymous terms. Online academic databases tend to be dumber than the sum of their parts, so you'll have to use tangentially related terms and inventive language to get all the results you want.

- If it's sensible, consider heading out into the field and speaking to ordinary people for their opinions. This isn't always appropriate (or welcomed) in a research project, but in some cases, it can provide you with some excellent perspective for your research.

- Review cultural artifacts as well. In many areas of study, there's useful information on attitudes, hopes, and/or concerns of people in a particular time and place contained within the art, music, and writing they produced. One has only to look at the woodblock prints of the later German Expressionists, for example, to understand that they lived in a world they felt was often dark, grotesque, and hopeless. Song lyrics and poetry can likewise express strong popular attitudes.

Expert Q&A

- Start early. The foundation of a great research project is the research, which takes time and patience to gather even if you aren't performing any original research of your own. Set aside time for it whenever you can, at least until your initial gathering phase is complete. Past that point, the project should practically come together on its own. Thanks Helpful 1 Not Helpful 0

- When in doubt, write more, rather than less. It's easier to pare down and reorganize an overabundance of information than it is to puff up a flimsy core of facts and anecdotes. Thanks Helpful 1 Not Helpful 0

- Respect the wishes of others. Unless you're a research journalist, it's vital that you yield to the wishes and requests of others before engaging in original research, even if it's technically ethical. Many older American Indians, for instance, harbor a great deal of cultural resentment towards social scientists who visit reservations for research, even those invited by tribal governments for important reasons such as language revitalization. Always tread softly whenever you're out of your element, and only work with those who want to work with you. Thanks Helpful 8 Not Helpful 2

- Be mindful of ethical concerns. Especially if you plan to use original research, there are very stringent ethical guidelines that must be followed for any credible academic body to accept it. Speak to an advisor (such as a professor) about what you plan to do and what steps you should take to verify that it will be ethical. Thanks Helpful 6 Not Helpful 2

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.butte.edu/departments/cas/tipsheets/research/research_paper.html

- ↑ https://www.nhcc.edu/academics/library/doing-library-research/basic-steps-research-process

- ↑ https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803&p=185905

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/research_papers/choosing_a_topic.html

- ↑ https://www.unr.edu/writing-speaking-center/student-resources/writing-speaking-resources/using-an-interview-in-a-research-paper

- ↑ https://www.science.org/content/article/how-review-paper

About This Article

The easiest way to get started with a research project is to use your notes and other materials to come up with topics that interest you. Research your favorite topic to see if it can be developed, and then refine it into a research question. Begin thoroughly researching, and collect notes and sources. To learn more about finding reliable and helpful sources while you're researching, continue reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Jun 30, 2016

Did this article help you?

Maooz Asghar

Aug 14, 2016

Jun 27, 2016

Calvin Kiyondi

Apr 24, 2017

Nov 2, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Methodology – Types, Examples and writing Guide

Research Methodology – Types, Examples and writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Methodology

Definition:

Research Methodology refers to the systematic and scientific approach used to conduct research, investigate problems, and gather data and information for a specific purpose. It involves the techniques and procedures used to identify, collect , analyze , and interpret data to answer research questions or solve research problems . Moreover, They are philosophical and theoretical frameworks that guide the research process.

Structure of Research Methodology

Research methodology formats can vary depending on the specific requirements of the research project, but the following is a basic example of a structure for a research methodology section:

I. Introduction

- Provide an overview of the research problem and the need for a research methodology section

- Outline the main research questions and objectives

II. Research Design

- Explain the research design chosen and why it is appropriate for the research question(s) and objectives

- Discuss any alternative research designs considered and why they were not chosen

- Describe the research setting and participants (if applicable)

III. Data Collection Methods

- Describe the methods used to collect data (e.g., surveys, interviews, observations)

- Explain how the data collection methods were chosen and why they are appropriate for the research question(s) and objectives

- Detail any procedures or instruments used for data collection

IV. Data Analysis Methods

- Describe the methods used to analyze the data (e.g., statistical analysis, content analysis )

- Explain how the data analysis methods were chosen and why they are appropriate for the research question(s) and objectives

- Detail any procedures or software used for data analysis

V. Ethical Considerations

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise from the research and how they were addressed

- Explain how informed consent was obtained (if applicable)

- Detail any measures taken to ensure confidentiality and anonymity

VI. Limitations

- Identify any potential limitations of the research methodology and how they may impact the results and conclusions

VII. Conclusion

- Summarize the key aspects of the research methodology section

- Explain how the research methodology addresses the research question(s) and objectives

Research Methodology Types

Types of Research Methodology are as follows:

Quantitative Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the collection and analysis of numerical data using statistical methods. This type of research is often used to study cause-and-effect relationships and to make predictions.

Qualitative Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the collection and analysis of non-numerical data such as words, images, and observations. This type of research is often used to explore complex phenomena, to gain an in-depth understanding of a particular topic, and to generate hypotheses.

Mixed-Methods Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that combines elements of both quantitative and qualitative research. This approach can be particularly useful for studies that aim to explore complex phenomena and to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a particular topic.

Case Study Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves in-depth examination of a single case or a small number of cases. Case studies are often used in psychology, sociology, and anthropology to gain a detailed understanding of a particular individual or group.

Action Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves a collaborative process between researchers and practitioners to identify and solve real-world problems. Action research is often used in education, healthcare, and social work.

Experimental Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the manipulation of one or more independent variables to observe their effects on a dependent variable. Experimental research is often used to study cause-and-effect relationships and to make predictions.

Survey Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the collection of data from a sample of individuals using questionnaires or interviews. Survey research is often used to study attitudes, opinions, and behaviors.

Grounded Theory Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the development of theories based on the data collected during the research process. Grounded theory is often used in sociology and anthropology to generate theories about social phenomena.

Research Methodology Example

An Example of Research Methodology could be the following:

Research Methodology for Investigating the Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Reducing Symptoms of Depression in Adults

Introduction:

The aim of this research is to investigate the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in reducing symptoms of depression in adults. To achieve this objective, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) will be conducted using a mixed-methods approach.

Research Design:

The study will follow a pre-test and post-test design with two groups: an experimental group receiving CBT and a control group receiving no intervention. The study will also include a qualitative component, in which semi-structured interviews will be conducted with a subset of participants to explore their experiences of receiving CBT.

Participants:

Participants will be recruited from community mental health clinics in the local area. The sample will consist of 100 adults aged 18-65 years old who meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder. Participants will be randomly assigned to either the experimental group or the control group.

Intervention :

The experimental group will receive 12 weekly sessions of CBT, each lasting 60 minutes. The intervention will be delivered by licensed mental health professionals who have been trained in CBT. The control group will receive no intervention during the study period.

Data Collection:

Quantitative data will be collected through the use of standardized measures such as the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). Data will be collected at baseline, immediately after the intervention, and at a 3-month follow-up. Qualitative data will be collected through semi-structured interviews with a subset of participants from the experimental group. The interviews will be conducted at the end of the intervention period, and will explore participants’ experiences of receiving CBT.

Data Analysis:

Quantitative data will be analyzed using descriptive statistics, t-tests, and mixed-model analyses of variance (ANOVA) to assess the effectiveness of the intervention. Qualitative data will be analyzed using thematic analysis to identify common themes and patterns in participants’ experiences of receiving CBT.

Ethical Considerations:

This study will comply with ethical guidelines for research involving human subjects. Participants will provide informed consent before participating in the study, and their privacy and confidentiality will be protected throughout the study. Any adverse events or reactions will be reported and managed appropriately.

Data Management:

All data collected will be kept confidential and stored securely using password-protected databases. Identifying information will be removed from qualitative data transcripts to ensure participants’ anonymity.

Limitations:

One potential limitation of this study is that it only focuses on one type of psychotherapy, CBT, and may not generalize to other types of therapy or interventions. Another limitation is that the study will only include participants from community mental health clinics, which may not be representative of the general population.

Conclusion:

This research aims to investigate the effectiveness of CBT in reducing symptoms of depression in adults. By using a randomized controlled trial and a mixed-methods approach, the study will provide valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying the relationship between CBT and depression. The results of this study will have important implications for the development of effective treatments for depression in clinical settings.

How to Write Research Methodology

Writing a research methodology involves explaining the methods and techniques you used to conduct research, collect data, and analyze results. It’s an essential section of any research paper or thesis, as it helps readers understand the validity and reliability of your findings. Here are the steps to write a research methodology:

- Start by explaining your research question: Begin the methodology section by restating your research question and explaining why it’s important. This helps readers understand the purpose of your research and the rationale behind your methods.

- Describe your research design: Explain the overall approach you used to conduct research. This could be a qualitative or quantitative research design, experimental or non-experimental, case study or survey, etc. Discuss the advantages and limitations of the chosen design.

- Discuss your sample: Describe the participants or subjects you included in your study. Include details such as their demographics, sampling method, sample size, and any exclusion criteria used.

- Describe your data collection methods : Explain how you collected data from your participants. This could include surveys, interviews, observations, questionnaires, or experiments. Include details on how you obtained informed consent, how you administered the tools, and how you minimized the risk of bias.

- Explain your data analysis techniques: Describe the methods you used to analyze the data you collected. This could include statistical analysis, content analysis, thematic analysis, or discourse analysis. Explain how you dealt with missing data, outliers, and any other issues that arose during the analysis.

- Discuss the validity and reliability of your research : Explain how you ensured the validity and reliability of your study. This could include measures such as triangulation, member checking, peer review, or inter-coder reliability.

- Acknowledge any limitations of your research: Discuss any limitations of your study, including any potential threats to validity or generalizability. This helps readers understand the scope of your findings and how they might apply to other contexts.

- Provide a summary: End the methodology section by summarizing the methods and techniques you used to conduct your research. This provides a clear overview of your research methodology and helps readers understand the process you followed to arrive at your findings.

When to Write Research Methodology

Research methodology is typically written after the research proposal has been approved and before the actual research is conducted. It should be written prior to data collection and analysis, as it provides a clear roadmap for the research project.

The research methodology is an important section of any research paper or thesis, as it describes the methods and procedures that will be used to conduct the research. It should include details about the research design, data collection methods, data analysis techniques, and any ethical considerations.

The methodology should be written in a clear and concise manner, and it should be based on established research practices and standards. It is important to provide enough detail so that the reader can understand how the research was conducted and evaluate the validity of the results.

Applications of Research Methodology

Here are some of the applications of research methodology:

- To identify the research problem: Research methodology is used to identify the research problem, which is the first step in conducting any research.

- To design the research: Research methodology helps in designing the research by selecting the appropriate research method, research design, and sampling technique.

- To collect data: Research methodology provides a systematic approach to collect data from primary and secondary sources.

- To analyze data: Research methodology helps in analyzing the collected data using various statistical and non-statistical techniques.

- To test hypotheses: Research methodology provides a framework for testing hypotheses and drawing conclusions based on the analysis of data.

- To generalize findings: Research methodology helps in generalizing the findings of the research to the target population.

- To develop theories : Research methodology is used to develop new theories and modify existing theories based on the findings of the research.

- To evaluate programs and policies : Research methodology is used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs and policies by collecting data and analyzing it.

- To improve decision-making: Research methodology helps in making informed decisions by providing reliable and valid data.

Purpose of Research Methodology

Research methodology serves several important purposes, including:

- To guide the research process: Research methodology provides a systematic framework for conducting research. It helps researchers to plan their research, define their research questions, and select appropriate methods and techniques for collecting and analyzing data.

- To ensure research quality: Research methodology helps researchers to ensure that their research is rigorous, reliable, and valid. It provides guidelines for minimizing bias and error in data collection and analysis, and for ensuring that research findings are accurate and trustworthy.

- To replicate research: Research methodology provides a clear and detailed account of the research process, making it possible for other researchers to replicate the study and verify its findings.

- To advance knowledge: Research methodology enables researchers to generate new knowledge and to contribute to the body of knowledge in their field. It provides a means for testing hypotheses, exploring new ideas, and discovering new insights.

- To inform decision-making: Research methodology provides evidence-based information that can inform policy and decision-making in a variety of fields, including medicine, public health, education, and business.

Advantages of Research Methodology

Research methodology has several advantages that make it a valuable tool for conducting research in various fields. Here are some of the key advantages of research methodology:

- Systematic and structured approach : Research methodology provides a systematic and structured approach to conducting research, which ensures that the research is conducted in a rigorous and comprehensive manner.

- Objectivity : Research methodology aims to ensure objectivity in the research process, which means that the research findings are based on evidence and not influenced by personal bias or subjective opinions.

- Replicability : Research methodology ensures that research can be replicated by other researchers, which is essential for validating research findings and ensuring their accuracy.

- Reliability : Research methodology aims to ensure that the research findings are reliable, which means that they are consistent and can be depended upon.

- Validity : Research methodology ensures that the research findings are valid, which means that they accurately reflect the research question or hypothesis being tested.

- Efficiency : Research methodology provides a structured and efficient way of conducting research, which helps to save time and resources.

- Flexibility : Research methodology allows researchers to choose the most appropriate research methods and techniques based on the research question, data availability, and other relevant factors.

- Scope for innovation: Research methodology provides scope for innovation and creativity in designing research studies and developing new research techniques.

Research Methodology Vs Research Methods

About the author.

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

15 Steps to Good Research

- Define and articulate a research question (formulate a research hypothesis). How to Write a Thesis Statement (Indiana University)

- Identify possible sources of information in many types and formats. Georgetown University Library's Research & Course Guides

- Judge the scope of the project.

- Reevaluate the research question based on the nature and extent of information available and the parameters of the research project.

- Select the most appropriate investigative methods (surveys, interviews, experiments) and research tools (periodical indexes, databases, websites).

- Plan the research project. Writing Anxiety (UNC-Chapel Hill) Strategies for Academic Writing (SUNY Empire State College)