Counternarratives: The Power of Narrative

Having written recently about the “danger of narrative”—how stories can distract us from thinking critically to make harmfully distorted representations seem natural and true—I thought it insufficient, if not irresponsible, not to make room for that other equally important possibility: narrative’s positive power.

In her well-known TED Talk, “ The Danger of a Single Story ,” Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie argues for the importance of a multiplicity of stories, voices, and perspectives in order to do justice to the fullest range of experience and explode reductive stereotypes of people and places. “Stories matter,” she says. “Many stories matter. Stories have been used to dispossess and malign. But stories can also be used to empower and to humanize. Stories can break the dignity of a people, but stories can also repair that broken dignity.”

As individual writers contributing our own stories to this multiplicity we might ask ourselves which stories, of the ones we can tell, need to be told. But no matter which stories we end up telling, we must attend to the ways craft itself can create opportunities for constructive and responsible representation. Many misrepresentations, for example, speak to lazy characterization. Characters, after all, are people as far as we’re concerned, and so we must work to ensure our characters, our people, have the richness and complexity readers require in order to care about, inhabit, and empathize with them. I’ve always found inspiration in the way Tobias Wolff puts it in his Paris Review interview :

And the most radical political writing of all is that which makes you aware of the reality of another human being. Self-absorbed as we are, self-imprisoned even, we don’t feel that often enough. Most of the spiritualities we’ve evolved are designed to deliver us from that lockup, and art is another way out. Good stories slip past our defenses—we all want to know what happens next—and then slow time down, and compel our interest and belief in other lives than our own, so that we feel ourselves in another presence. It’s a kind of awakening, a deliverance, it cracks our shell and opens us up to the truth and singularity of others—to their very being. Writers who can make others, even our enemies, real to us have achieved a profound political end, whether or not they would call it that.

Note how Wolff suggests that what can make narrative dangerous—its ability to “slip past our defenses”—is the very same thing that can make it positively powerful. Instead of blunting our critical faculties, stories can disarm us of our misconceptions, biases, and fears.

What about writers and stories who keep us both thinking critically and, at the same time or by turns, drawn in empathetically? Consider John Keene’s recent and deeply rewarding collection out from New Directions, Counternarratives .

In “An Outtake from the Ideological Origins of the American Revolution,” for example, we follow the sinuous trajectory of the life of Zion, a chronically escaping slave in Boston at the dawn of the American Revolution. To call Zion’s story “An Outtake” is to draw attention to the “counter” stance of this narrative against the received narrative of our history (the title also references a Pulitzer prize-winning history book)—it’s the aspect of the story edited out, suppressed, silenced. But returning agency to Zion by telling his story isn’t quite enough for Keene; the story he tells also serves to disrupt the comforting and simplifying assumptions we might be tempted to make about a character like this. To represent any character, even one who has been historically mis- or underrepresented, as perfect or infallible is to deny that character full complex humanity. So in “An Outtake,” Keene allows Zion’s relationship to our sympathies to be just as slippery as his relationship to his owners—just as they literally cannot hold him in place, we cannot force him to be simply either good or bad. In one paragraph we admire his cunning and determination:

… Zion charmed a Dutch whore strolling by to untie his bindings, whereupon he set off to find the first loosely hitched horse. As he ran he proclaimed himself free. Under duress one’s actions assume a dream-like clarity. An unattended nag stood outside a tavern, and off Zion strode.

And in the next we recoil at his depravity:

After a spree which stretched from the city of Boston west to the edges of Middlesex County, the slave played his worst hand when he committed lascivious acts just across the county line on the person of a sleeping widow, Mary Shaftesbone, near Shrewsbury. Having broken into her home and reportedly taken violent liberties with her, unaccountably Zion did not flee the town, but entered a nearby tavern and began a round of popular songs, to the delight of the crowd and the horror of the violated woman.

For each different counternarrative, Keene pushes himself to find a form appropriate to his subject. While these formal experiments are part of the joy of the book—“What can he do next?”—they also help highlight the themes basic both to this specific project and, at the end of the day, to all fiction and storytelling.

In “On Brazil, or Dénouement: The Londônias-Figueiras,” we start with the image of a recent newspaper staff report on a corpse found in a São Paulo favela. From here Keene travels back to the early fifteenth-century to bring us slowly back to the found corpse, demonstrating how an awareness of the past can deepen our understanding of the present and suggesting the shortcomings of the officially sanctioned narrative (the newspaper text). In “A Letter on the Trials of the Counterreformation in New Lisbon,” the story of a priest sent to reform the wayward House of the Second Order of the Discalced Brothers of the Holy Ghost takes on increasingly charged meaning as we realize who, unexpectedly, is telling the story (that is, writing the letter).

Perhaps my favorite of Keene’s counternarratives is “Gloss on a History of Roman Catholics in the Early American Republic, 1790-1825; or the Strange History of Our Lady of the Sorrows.” Like “On Brazil” or “A Letter,” this novella draws our attention to the fact of its written-ness in a way that prompts us to think about who gets to tell what story, who is granted voice.

Formally, “Gloss” is an eighty-page footnote. An “outtake” of sorts, just as we’re acclimating to the dry, dense terrain of the title’s first “History,” in a subversive inversion the footnote interrupts and takes over to tell the story of Carmel, “the lone child among the handful of bondspeople” remaining on a Haitian coffee plantation in 1803. Carmel’s story carries her from Haiti to a convent in Kentucky, where she serves a demanding white teenage girl. At first Carmel is mute—a silenced voice, perhaps, someone marginalized to the point of near invisibility or at least inhumanity: “Up until this point [her owner] had not really noted her presence, considering her no more extensively than one might remember an extra utensil in a large hand-me-down table service.” Instead of communicating verbally, Carmel draws; her drawings, as well as her silence, are subject to unfair projection and interpretation by other people, though she herself, like many writers, doesn’t fully understand what she creates.

As “Gloss” goes on to cover a series of strange and harrowing events at the Kentucky convent, Carmel gradually gains agency; as she gains agency, her voice takes over the narration, first as a series of diary entries in a kind of pidgin shorthand, then as a more straightforward first-person narrative in Standard English. Towards the end of the novella, she even takes on supernatural powers of the kind projected onto her earlier mysterious silence. Like a writer manipulating his characters, Carmel brings what I think we could justify calling her Künstlerroman to a climax by employing her newly developed ability to physically move people through space, compelling them to do what she wants with her mind—all from a place, again authorial, of literal self-willed invisibility. At the end of “Gloss” we see Carmel retelling her story to a group of fellow escaped servants.

In this way Keene’s Counternarratives both demonstrate and enact the power of narrative. They not only use important stories to assert the dignity of misrepresented characters and invite our empathy, but they also ask us to think critically about how stories wield their power.

Related Posts

A Man and an Epigram Walk Into a Bar: A Review of Thomas Farber’s “The End of My Wits”

However obliquely: georges perec’s “la disparition”.

“The Collective,” Divided: A Review

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

English Studies

This website is dedicated to English Literature, Literary Criticism, Literary Theory, English Language and its teaching and learning.

Counter-Narratives in Literature & Theory

Counter-narratives, as a theoretical term, refer to alternative narratives or discourses that challenge and deconstruct prevailing dominant narratives, particularly those reflecting the perspectives of those in power.

Etymology of Counter-Narratives

Table of Contents

The term “counter-narratives” emerged in academic and social discourse in the late 20th century, particularly within the fields of postcolonial studies, critical theory, and cultural studies. Its etymology lies in its role as a response to dominant narratives and power structures.

Counter-narratives are stories or accounts that challenge, subvert, or deconstruct prevailing narratives, often those perpetuated by hegemonic groups, institutions, or historical accounts. These narratives aim to provide marginalized voices and perspectives, offering alternative interpretations of historical events, social dynamics, and power relations.

Counter-narratives have become a crucial tool in critical analysis, helping to shed light on hidden or suppressed histories and offering a means of empowerment and resistance for marginalized groups, while interrogating established paradigms of knowledge and representation.

Meanings of Counter-Narratives

Definition of counter-narratives as a theoretical term.

Counter-narratives, as a theoretical term , refer to alternative narratives or discourses that challenge and deconstruct prevailing dominant narratives, particularly those reflecting the perspectives of those in power. These alternative narratives provide voices and perspectives often marginalized or oppressed, disrupting established power structures and hierarchies.

Counter-narratives aim to shed light on hidden or suppressed histories, debunk stereotypes, empower marginalized groups, and promote social change by encouraging critical analysis and reevaluation of accepted paradigms.

Counter-Narratives: Theorists, Works and Arguments

- Michel Foucault: Foucault’s work on power and knowledge, particularly in The Archaeology of Knowledge and Discipline and Punish , laid the theoretical foundation for understanding counter-narratives as resistance to dominant power structures through alternative discourses .

- Edward Said: Said’s Orientalism highlighted the construction of stereotypes and counter-narratives in the context of the East-West relationship, emphasizing how counter-narratives can challenge colonialist narratives.

- Orientalism by Edward Said: This seminal work critiques the Eurocentric construction of knowledge about the Middle East and examines how counter-narratives can disrupt colonialist perspectives.

- The Archaeology of Knowledge by Michel Foucault: In this book, Foucault explores how knowledge is produced and how counter-narratives can deconstruct and challenge established discourses of power.

- Resistance to Hegemony : Counter-narratives are argued to be a form of resistance to hegemonic narratives, offering alternative viewpoints that challenge dominant ideologies and power structures.

- Empowerment of Marginalized Groups: Counter-narratives are seen as a means of empowering marginalized or oppressed groups by providing them a platform to express their own stories and experiences, countering the marginalization they may face in mainstream narratives.

- Reevaluation of Truth and Knowledge: These narratives encourage a reevaluation of accepted truths and knowledge, arguing that dominant narratives are often constructed to serve specific interests and that counter-narratives offer a more diverse and accurate understanding of complex issues.

Counter-Narratives and Literary Theories

- Postcolonial Theory : Counter-narratives are particularly relevant in postcolonial literary criticism, where they challenge the colonial narratives that have shaped the portrayal of colonized peoples and cultures. Postcolonial scholars use counter-narratives to provide alternative viewpoints and disrupt the hegemonic discourse of colonialism.

- Feminist Literary Criticism : In the realm of feminist literary criticism, counter-narratives are instrumental in critiquing traditional gender roles and the representation of women in literature. They offer alternative stories and perspectives that challenge the patriarchy and provide a voice for marginalized women.

- Queer Theory : Counter-narratives play a significant role in queer theory, where they subvert heteronormative narratives and provide alternative understandings of sexuality and gender. Queer theorists use counter-narratives to challenge societal norms and deconstruct conventional representations of LGBTQ+ individuals.

- African-American and Ethnic Studies : In the context of African-American and ethnic studies, counter-narratives are employed to challenge stereotypes and provide alternative perspectives on the experiences of marginalized racial and ethnic groups. These narratives shed light on the complexities of identity and representation.

- Reader-Response Theory : Counter-narratives are also relevant in reader-response theory, as they allow readers to engage with a text in ways that challenge the author’s intended meaning. Readers can create their own counter-narratives as they interact with the text, emphasizing the subjectivity of interpretation.

- Deconstruction : Counter-narratives align with deconstructionist theory, which seeks to expose the inherent contradictions and dualities in texts. Deconstructionists use counter-narratives to deconstruct dominant narratives and highlight the instability of meaning.

- Marxist Literary Criticism : In Marxist literary criticism, counter-narratives may be used to challenge capitalist and class-based narratives. They offer alternative perspectives on social and economic structures and may reveal the hidden struggles of the working class.

- Narratology : Counter-narratives also engage with narratological theory by subverting traditional narrative structures and expectations. They challenge the conventional ways stories are told and encourage experimentation with narrative form.

In literary studies, counter-narratives provide a valuable tool for critiquing and reimagining the ways in which stories are constructed and presented. They allow for a more inclusive and diverse literary landscape, offering alternative readings and interpretations that challenge the dominance of certain narratives.

Counter-Narratives in Literary Criticism

These novels show examples of the use of counter-narratives to challenge prevailing narratives and offer alternative perspectives, aligning with various literary theories and critical approaches. They invite readers to question dominant narratives and engage in critical discussions about identity, power, and resilience.

Suggested Readings

- Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth . Grove Press, 1963.

- Said, Edward W. Orientalism . Pantheon, 1978.

- Walker, Alice. The Color Purple . Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982.

- Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart . Anchor Books, 1959.

- Roy, Arundhati. The God of Small Things . Random House, 1997.

- Whitehead, Colson. The Underground Railroad . Doubleday, 2016.

- Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge . Vintage, 1972.

- Woolf, Virginia. Orlando . Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1928.

- Morrison, Toni. Beloved . Alfred A. Knopf, 1987.

- Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale . Houghton Mifflin, 1985.

Related posts:

- Differance in Literature & Literary Theory

- Logocentrism in Literature & Literary Theory

- Epistemology in Literature & Literary Theory

- Biopower in Literature & Literary Theory

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Publication

- Arts & Humanities

- Behavioural Sciences

- Business & Economics

- Earth & Environment

- Education & Training

- Health & Medicine

- Engineering & Technology

- Physical Sciences

- Thought Leaders

- Community Content

- Outreach Leaders

- Our Company

- Our Clients

- Testimonials

- Our Services

- Researcher App

- Podcasts & Video Abstracts

Subscribe To Our Free Publication

By selecting any of the topic options below you are consenting to receive email communications from us about these topics.

- Behavioral Science

- Engineering & Technology

- All The Above

We are able share your email address with third parties (such as Google, Facebook and Twitter) in order to send you promoted content which is tailored to your interests as outlined above. If you are happy for us to contact you in this way, please tick below.

- I consent to receiving promoted content.

- I would like to learn more about Research Outreach's services.

We use MailChimp as our marketing automation platform. By clicking below to submit this form, you acknowledge that the information you provide will be transferred to MailChimp for processing in accordance with their Privacy Policy and Terms .

Master and counter narratives: Same facts – different stories

The research of Professor Michael Bamberg of Clark University is dedicated to understanding narratives and the dynamics of narratives. His studies outline how dominant narratives emerge and how counter narratives get created and believed. Through the analysis of narrative practices , Professor Bamberg proposes that we can intentionally begin to present stories that enable social change, by looking beyond the story, to uncover and challenge the assumptions behind dominant narratives.

Storytelling is everywhere! We tell stories daily, from the simplest of stories about ordinary happenings to unexpected and unusual tales, and even up to dramatic events that may have life-changing consequences. In the process of telling, we craft the story by constructing characters, describing their actions, and putting the actions into sequences. When we listen to stories, we observe, try to make sense, and react with an evaluative position. We assume, surmise, speculate and place value vis-à-vis storytellers’ intent, and what we believe to be true.

Patriots or insurrectionists? On 6th of January 2021, millions of people watched a dramatic and unprecedented series of actions unfold on news screens, as Congress sat in session in the Capitol of Washington D.C. to certify the election of Joe Biden. A little further away, a large group of people gathered to hear the outgoing President. He told them how the election had been “stolen” and therefore, their voices had been silenced. He spoke about “reclaiming America’s greatness” and that “you have to show strength and you have to be strong.” Together, he said, they would march “over to the Capitol building to peacefully and patriotically” make their voices heard. He thanked them for their “extraordinary love” of the country.

On 6th of January, an insurrection took place when a mob of Trump supporters gathered outside the Capitol building. These thugs who were outright rioters, “white nationalists” and “supremacists” motivated by hatred and violence, and incited by the outgoing President, broke into the building and threatened Congress.

Lenses of truth Patriots or Insurrectionists? How is it that the same facts and series of events can have such different truths? Professor Michael Bamberg has devoted his research to examine how different versions of the same facts can have such different meanings and end up being told as countering, i.e., in stark contrast to each other.

Our stories are told using words and language habits that often imbue bias about people’s intent or specific actions.

Prof Bamberg explains that typically there is a dominant story (master narrative) that gets told against a background of assumptions which people believe to be true and which they use to make sense of events and of each other. Woven into these assumptions, are normative life experiences and shared meanings. These more dominant narratives with their background assumptions are used to infer the intent behind people’s action, and often are set within cultural, social, and political systems of power (hegemonic norms). From this perspective, the dominant background assumptions made when people tell and listen to stories, can in themselves be quite silencing of other stories that might be told against a different set of background assumptions. These alternate assumptions – when told as counter-narratives – enable a different “truth” to be told and heard, allowing alternate lenses of understanding of the same facts of an event.

Versions of the truth On the 8th of March 2021, millions of people tuned in to listen to an extraordinary story told to Oprah Winfrey, by Meghan Markle and Prince Harry, the Duchess and Duke of Sussex. They shared intimate stories about racism, emotional abandonment and loss of personal freedom, which the Duchess had endured after marrying into the British Royal Family. Meghan said: “Life is about storytelling. For us to be able to have storytelling through a truthful lens that is hopefully uplifting is going to be great knowing how many people that can land with and be able to give a voice to a lot of people that are underrepresented and aren’t really heard.”

Describing the press coverage to which she was subjected as a member of the Royal Family, the Duchess explained to Oprah, there was a “racist” element to the press coverage. The next day, on one side of the North Atlantic, an explosive debate about this interview erupted on live television between two presenters on Good Morning Britain. Emotions were high and one of the presenters walked off the show in outrage. He later described the Duchess as valuing her own “version of the truth above the actual truth”. A little later, on the other side of the Atlantic, the Los Angeles Times ran a story about the two presenters, saying that “the two differed in their interpretations of the Duchess of Sussex’s” revelations.

What is a version of truth and which version should we believe? How do we approach the analysis of different stories so that we can make sense of them?

Prof Bamberg says that stories are always linked to “the particular space and time” in which they are told. One way of approaching a story, is therefore to apply a “narrative practice approach” as a way to unpick or analyse a story. In this approach, the focus moves from trying to infer the storytellers’ subjective perspective, to analysing the “ethnographic interactive context” in which the story is told.

Recognising that there is a context in which a story is communicated and that the story itself serves a “social, relational, and situated” purpose for storytellers and their audience, allows a deeper understanding for how to interpret the story. This requires recognising that stories are fluid and dynamic and can be re-scripted and told differently, using the same overarching storyline or sets of facts.

What is plausible? And what is true? How does an alternate storyline – or anything that counters dominant (and hegemonic) versions – get believed and potentially can replace dominant versions? Professor Bamberg says that presenting a plausible alternative story that challenges dominant and hegemonic assumptions, enables the space for a new understanding of events to emerge. Thus, contributing to better understand how master, counter and hegemonic narratives get constructed, and the contexts in which they are employed, opens up the possibility to create space within which social change can be accomplished through the crafting of counter narrative.

When a story is intentionally crafted and positioned to plausibly challenge the dominant assumptions of power relations and identities, social change can begin to happen.

A good example of crafting a counter narrative is evident in court proceedings when both prosecuting and defence attorneys, present to the judge. As an example, Bamberg presents a detailed analysis of a case of an elderly man who has killed his wife and is on trial for murder. In this, the same way as when Derek Chauvin was on trial, the facts are not disputed: the death of a person has been consequential to the act of the accused. What is on trial, however, is the web of circumstances: the intentions and motives, what happened previous to the killing of George Floyd – up to the ‘fact’ that, in unprecedented ways, other police officers, including the Minneapolis police chief, testified against and denounced another officer’s actions. And if it hadn’t been for the 9 minutes and 29 seconds video by 17-year-old Darnella Frazier that successfully countered the original narrative of the police report, Derek Chauvin might very well still be part of the Minneapolis police force.

Purpose of the story – why this story here-and-now? The original police statement from May 25, 2020:

Man Dies After Medical Incident During Police Interaction… He was ordered to step from his car. After he got out, he physically resisted officers. Officers were able to get the suspect into handcuffs and noted he appeared to be suffering medical distress. Officers called for an ambulance. He was transported to Hennepin County Medical Center by ambulance where he died a short time later.

What Bamberg’s examples show is that the framing of a sequence of events is equally, and often probably more, important with regard to make sense of what actually happened. The words and language habits used to frame a sequence of events express assumptions about people’s intent and their motives, imbued with bias and stereotypes that easily sway the audience’s emotions and responses. To be able to account for how this happens, Prof Bamberg suggests that an analytic framework is required that goes beyond what’s been said – a framework that probes more deeply into how it’s been said as well as the wider contextual aspects within which particular narrative framings are situated.

We tell stories to share identities and create relationships with others who share our understandings. We tell stories to position ourselves and influence how people view us. We tell stories to maintain the dominant assumptions within our social groups and to direct outcomes. Our stories are dynamic and fluid, interactive and contextual, told and heard, through different identities and deliberate positionings and negotiations regarding the ‘truth’. Recognising the power of stories in this way, opens up a pathway towards social change. When a story is intentionally crafted and positioned to plausibly challenge the dominant and potentially hegemonic assumptions of power relations and identities, social change can begin to happen.

Personal Response

Fake news and fake stories often make the headlines. How can people counter these narratives?

To discern intentionally fabricated narratives (e.g., ‘COVID is a hoax’ or ‘Mexicans are rapists’) from counter narratives that intentionally challenge hegemonic narratives (such as ‘gay-love-is-unnatural’ or ‘non-aryans-are subhumans’) is a matter of analytic rigour. Fact checking, i.e., scrutinising the events that are referred to, will ultimately remain insufficient. What needs to be taken into account is who tells which sequence of events to whom, at which time, and in which context, and for what purpose. I agree that this sounds more complex to a seemingly simple question; but that’s what the narrative practice approach has in store.

This feature article was created with the approval of the research team featured. This is a collaborative production, supported by those featured to aid free of charge, global distribution.

Want to read more articles like this, sign up to our mailing list and read about the topics that matter to you the most., leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.1 Narration

Learning objectives.

- Determine the purpose and structure of narrative writing.

- Understand how to write a narrative essay.

Rhetorical modes simply mean the ways in which we can effectively communicate through language. This chapter covers nine common rhetorical modes. As you read about these nine modes, keep in mind that the rhetorical mode a writer chooses depends on his or her purpose for writing. Sometimes writers incorporate a variety of modes in any one essay. In covering the nine modes, this chapter also emphasizes the rhetorical modes as a set of tools that will allow you greater flexibility and effectiveness in communicating with your audience and expressing your ideas.

The Purpose of Narrative Writing

Narration means the art of storytelling, and the purpose of narrative writing is to tell stories. Any time you tell a story to a friend or family member about an event or incident in your day, you engage in a form of narration. In addition, a narrative can be factual or fictional. A factual story is one that is based on, and tries to be faithful to, actual events as they unfolded in real life. A fictional story is a made-up, or imagined, story; the writer of a fictional story can create characters and events as he or she sees fit.

The big distinction between factual and fictional narratives is based on a writer’s purpose. The writers of factual stories try to recount events as they actually happened, but writers of fictional stories can depart from real people and events because the writers’ intents are not to retell a real-life event. Biographies and memoirs are examples of factual stories, whereas novels and short stories are examples of fictional stories.

Because the line between fact and fiction can often blur, it is helpful to understand what your purpose is from the beginning. Is it important that you recount history, either your own or someone else’s? Or does your interest lie in reshaping the world in your own image—either how you would like to see it or how you imagine it could be? Your answers will go a long way in shaping the stories you tell.

Ultimately, whether the story is fact or fiction, narrative writing tries to relay a series of events in an emotionally engaging way. You want your audience to be moved by your story, which could mean through laughter, sympathy, fear, anger, and so on. The more clearly you tell your story, the more emotionally engaged your audience is likely to be.

On a separate sheet of paper, start brainstorming ideas for a narrative. First, decide whether you want to write a factual or fictional story. Then, freewrite for five minutes. Be sure to use all five minutes, and keep writing the entire time. Do not stop and think about what to write.

The following are some topics to consider as you get going:

The Structure of a Narrative Essay

Major narrative events are most often conveyed in chronological order , the order in which events unfold from first to last. Stories typically have a beginning, a middle, and an end, and these events are typically organized by time. Certain transitional words and phrases aid in keeping the reader oriented in the sequencing of a story. Some of these phrases are listed in Table 10.1 “Transition Words and Phrases for Expressing Time” . For more information about chronological order, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” and Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” .

Table 10.1 Transition Words and Phrases for Expressing Time

The following are the other basic components of a narrative:

- Plot . The events as they unfold in sequence.

- Characters . The people who inhabit the story and move it forward. Typically, there are minor characters and main characters. The minor characters generally play supporting roles to the main character, or the protagonist .

- Conflict . The primary problem or obstacle that unfolds in the plot that the protagonist must solve or overcome by the end of the narrative. The way in which the protagonist resolves the conflict of the plot results in the theme of the narrative.

- Theme . The ultimate message the narrative is trying to express; it can be either explicit or implicit.

Writing at Work

When interviewing candidates for jobs, employers often ask about conflicts or problems a potential employee has had to overcome. They are asking for a compelling personal narrative. To prepare for this question in a job interview, write out a scenario using the narrative mode structure. This will allow you to troubleshoot rough spots, as well as better understand your own personal history. Both processes will make your story better and your self-presentation better, too.

Take your freewriting exercise from the last section and start crafting it chronologically into a rough plot summary. To read more about a summary, see Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content” . Be sure to use the time transition words and phrases listed in Table 10.1 “Transition Words and Phrases for Expressing Time” to sequence the events.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your rough plot summary.

Writing a Narrative Essay

When writing a narrative essay, start by asking yourself if you want to write a factual or fictional story. Then freewrite about topics that are of general interest to you. For more information about freewriting, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

Once you have a general idea of what you will be writing about, you should sketch out the major events of the story that will compose your plot. Typically, these events will be revealed chronologically and climax at a central conflict that must be resolved by the end of the story. The use of strong details is crucial as you describe the events and characters in your narrative. You want the reader to emotionally engage with the world that you create in writing.

To create strong details, keep the human senses in mind. You want your reader to be immersed in the world that you create, so focus on details related to sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch as you describe people, places, and events in your narrative.

As always, it is important to start with a strong introduction to hook your reader into wanting to read more. Try opening the essay with an event that is interesting to introduce the story and get it going. Finally, your conclusion should help resolve the central conflict of the story and impress upon your reader the ultimate theme of the piece. See Chapter 15 “Readings: Examples of Essays” to read a sample narrative essay.

On a separate sheet of paper, add two or three paragraphs to the plot summary you started in the last section. Describe in detail the main character and the setting of the first scene. Try to use all five senses in your descriptions.

Key Takeaways

- Narration is the art of storytelling.

- Narratives can be either factual or fictional. In either case, narratives should emotionally engage the reader.

- Most narratives are composed of major events sequenced in chronological order.

- Time transition words and phrases are used to orient the reader in the sequence of a narrative.

- The four basic components to all narratives are plot, character, conflict, and theme.

- The use of sensory details is crucial to emotionally engaging the reader.

- A strong introduction is important to hook the reader. A strong conclusion should add resolution to the conflict and evoke the narrative’s theme.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

coun ter nar ra tive

Definition of counternarrative, examples of counternarrative in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'counternarrative.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

counter- + narrative entry 1

circa 1685, in the meaning defined above

Dictionary Entries Near counternarrative

counternaiant

counternarrative

counteroffensive

Cite this Entry

“Counternarrative.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/counternarrative. Accessed 1 Jun. 2024.

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

More commonly misspelled words, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - may 31, pilfer: how to play and win, 9 superb owl words, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, your favorite band is in the dictionary, games & quizzes.

Talking About Poverty: Narratives, Counter-Narratives, and Telling Effective Stories

For communicators, activists, advocates, and content creators to understand what kinds of stories they can tell to convey the realities of poverty, they need first to understand what existing narratives they’re up against. This report identifies the major poverty narratives found in the existing body of narrative research and offers practical advice about how to deploy counter-narratives to create better stories—and, ultimately, create social change.

Share this page

Related content, moving toward collective health and prosperity means putting hunger and poverty in the rearview mirror.

The terrain of public thinking about hunger and poverty is fraught with unhelpful assumptions and associations—including harmful, dehumanizing stereotypes. Fortunately, certain helpful public...

Using narrative to shift mindsets and make change

Three dominant American cultural mindsets block progress on a wide range of progressive issues. Understanding these mindsets and how they are activated is key in developing strategies to counter...

Understanding how culture is changing and what this means for grant makers

The Culture Change Project has been studying cultural mindsets for the last three years. The project looks at whether culture is changing and if so, how and for whom. One of the changes that we...

Staging the counter-narrative in Don DeLillo’s Falling Man

Publication status, file version.

- Accepted version

Place of publication

Department affiliated with.

- English Publications

Full text available

Peer reviewed, legacy posted date, first open access (foa) date, first compliant deposit (fcd) date, usage metrics.

The Ultimate Narrative Essay Guide for Beginners

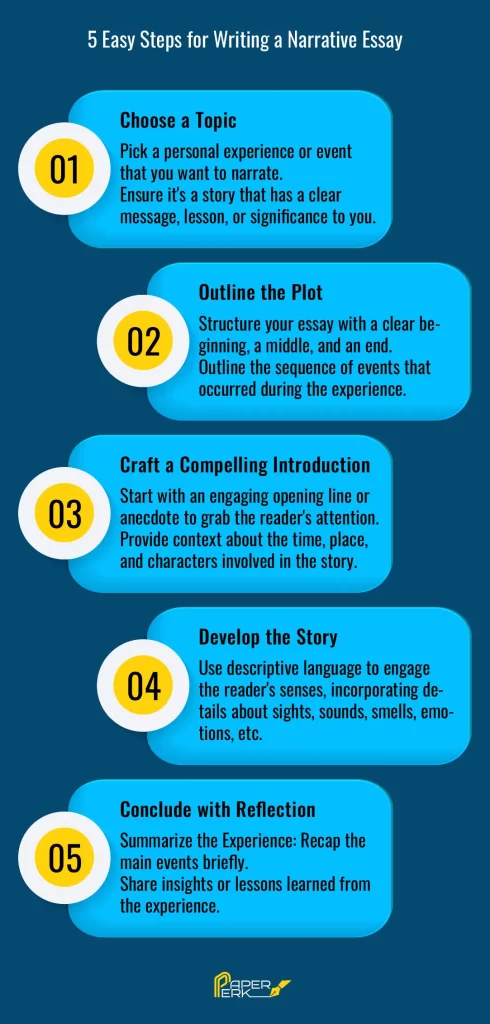

A narrative essay tells a story in chronological order, with an introduction that introduces the characters and sets the scene. Then a series of events leads to a climax or turning point, and finally a resolution or reflection on the experience.

Speaking of which, are you in sixes and sevens about narrative essays? Don’t worry this ultimate expert guide will wipe out all your doubts. So let’s get started.

Table of Contents

Everything You Need to Know About Narrative Essay

What is a narrative essay.

When you go through a narrative essay definition, you would know that a narrative essay purpose is to tell a story. It’s all about sharing an experience or event and is different from other types of essays because it’s more focused on how the event made you feel or what you learned from it, rather than just presenting facts or an argument. Let’s explore more details on this interesting write-up and get to know how to write a narrative essay.

Elements of a Narrative Essay

Here’s a breakdown of the key elements of a narrative essay:

A narrative essay has a beginning, middle, and end. It builds up tension and excitement and then wraps things up in a neat package.

Real people, including the writer, often feature in personal narratives. Details of the characters and their thoughts, feelings, and actions can help readers to relate to the tale.

It’s really important to know when and where something happened so we can get a good idea of the context. Going into detail about what it looks like helps the reader to really feel like they’re part of the story.

Conflict or Challenge

A story in a narrative essay usually involves some kind of conflict or challenge that moves the plot along. It could be something inside the character, like a personal battle, or something from outside, like an issue they have to face in the world.

Theme or Message

A narrative essay isn’t just about recounting an event – it’s about showing the impact it had on you and what you took away from it. It’s an opportunity to share your thoughts and feelings about the experience, and how it changed your outlook.

Emotional Impact

The author is trying to make the story they’re telling relatable, engaging, and memorable by using language and storytelling to evoke feelings in whoever’s reading it.

Narrative essays let writers have a blast telling stories about their own lives. It’s an opportunity to share insights and impart wisdom, or just have some fun with the reader. Descriptive language, sensory details, dialogue, and a great narrative voice are all essentials for making the story come alive.

The Purpose of a Narrative Essay

A narrative essay is more than just a story – it’s a way to share a meaningful, engaging, and relatable experience with the reader. Includes:

Sharing Personal Experience

Narrative essays are a great way for writers to share their personal experiences, feelings, thoughts, and reflections. It’s an opportunity to connect with readers and make them feel something.

Entertainment and Engagement

The essay attempts to keep the reader interested by using descriptive language, storytelling elements, and a powerful voice. It attempts to pull them in and make them feel involved by creating suspense, mystery, or an emotional connection.

Conveying a Message or Insight

Narrative essays are more than just a story – they aim to teach you something. They usually have a moral lesson, a new understanding, or a realization about life that the author gained from the experience.

Building Empathy and Understanding

By telling their stories, people can give others insight into different perspectives, feelings, and situations. Sharing these tales can create compassion in the reader and help broaden their knowledge of different life experiences.

Inspiration and Motivation

Stories about personal struggles, successes, and transformations can be really encouraging to people who are going through similar situations. It can provide them with hope and guidance, and let them know that they’re not alone.

Reflecting on Life’s Significance

These essays usually make you think about the importance of certain moments in life or the impact of certain experiences. They make you look deep within yourself and ponder on the things you learned or how you changed because of those events.

Demonstrating Writing Skills

Coming up with a gripping narrative essay takes serious writing chops, like vivid descriptions, powerful language, timing, and organization. It’s an opportunity for writers to show off their story-telling abilities.

Preserving Personal History

Sometimes narrative essays are used to record experiences and special moments that have an emotional resonance. They can be used to preserve individual memories or for future generations to look back on.

Cultural and Societal Exploration

Personal stories can look at cultural or social aspects, giving us an insight into customs, opinions, or social interactions seen through someone’s own experience.

Format of a Narrative Essay

Narrative essays are quite flexible in terms of format, which allows the writer to tell a story in a creative and compelling way. Here’s a quick breakdown of the narrative essay format, along with some examples:

Introduction

Set the scene and introduce the story.

Engage the reader and establish the tone of the narrative.

Hook: Start with a captivating opening line to grab the reader’s attention. For instance:

Example: “The scorching sun beat down on us as we trekked through the desert, our water supply dwindling.”

Background Information: Provide necessary context or background without giving away the entire story.

Example: “It was the summer of 2015 when I embarked on a life-changing journey to…”

Thesis Statement or Narrative Purpose

Present the main idea or the central message of the essay.

Offer a glimpse of what the reader can expect from the narrative.

Thesis Statement: This isn’t as rigid as in other essays but can be a sentence summarizing the essence of the story.

Example: “Little did I know, that seemingly ordinary hike would teach me invaluable lessons about resilience and friendship.”

Body Paragraphs

Present the sequence of events in chronological order.

Develop characters, setting, conflict, and resolution.

Story Progression : Describe events in the order they occurred, focusing on details that evoke emotions and create vivid imagery.

Example : Detail the trek through the desert, the challenges faced, interactions with fellow hikers, and the pivotal moments.

Character Development : Introduce characters and their roles in the story. Show their emotions, thoughts, and actions.

Example : Describe how each character reacted to the dwindling water supply and supported each other through adversity.

Dialogue and Interactions : Use dialogue to bring the story to life and reveal character personalities.

Example : “Sarah handed me her last bottle of water, saying, ‘We’re in this together.'”

Reach the peak of the story, the moment of highest tension or significance.

Turning Point: Highlight the most crucial moment or realization in the narrative.

Example: “As the sun dipped below the horizon and hope seemed lost, a distant sound caught our attention—the rescue team’s helicopters.”

Provide closure to the story.

Reflect on the significance of the experience and its impact.

Reflection : Summarize the key lessons learned or insights gained from the experience.

Example : “That hike taught me the true meaning of resilience and the invaluable support of friendship in challenging times.”

Closing Thought : End with a memorable line that reinforces the narrative’s message or leaves a lasting impression.

Example : “As we boarded the helicopters, I knew this adventure would forever be etched in my heart.”

Example Summary:

Imagine a narrative about surviving a challenging hike through the desert, emphasizing the bonds formed and lessons learned. The narrative essay structure might look like starting with an engaging scene, narrating the hardships faced, showcasing the characters’ resilience, and culminating in a powerful realization about friendship and endurance.

Different Types of Narrative Essays

There are a bunch of different types of narrative essays – each one focuses on different elements of storytelling and has its own purpose. Here’s a breakdown of the narrative essay types and what they mean.

Personal Narrative

Description : Tells a personal story or experience from the writer’s life.

Purpose: Reflects on personal growth, lessons learned, or significant moments.

Example of Narrative Essay Types:

Topic : “The Day I Conquered My Fear of Public Speaking”

Focus: Details the experience, emotions, and eventual triumph over a fear of public speaking during a pivotal event.

Descriptive Narrative

Description : Emphasizes vivid details and sensory imagery.

Purpose : Creates a sensory experience, painting a vivid picture for the reader.

Topic : “A Walk Through the Enchanted Forest”

Focus : Paints a detailed picture of the sights, sounds, smells, and feelings experienced during a walk through a mystical forest.

Autobiographical Narrative

Description: Chronicles significant events or moments from the writer’s life.

Purpose: Provides insights into the writer’s life, experiences, and growth.

Topic: “Lessons from My Childhood: How My Grandmother Shaped Who I Am”

Focus: Explores pivotal moments and lessons learned from interactions with a significant family member.

Experiential Narrative

Description: Relays experiences beyond the writer’s personal life.

Purpose: Shares experiences, travels, or events from a broader perspective.

Topic: “Volunteering in a Remote Village: A Journey of Empathy”

Focus: Chronicles the writer’s volunteering experience, highlighting interactions with a community and personal growth.

Literary Narrative

Description: Incorporates literary elements like symbolism, allegory, or thematic explorations.

Purpose: Uses storytelling for deeper explorations of themes or concepts.

Topic: “The Symbolism of the Red Door: A Journey Through Change”

Focus: Uses a red door as a symbol, exploring its significance in the narrator’s life and the theme of transition.

Historical Narrative

Description: Recounts historical events or periods through a personal lens.

Purpose: Presents history through personal experiences or perspectives.

Topic: “A Grandfather’s Tales: Living Through the Great Depression”

Focus: Shares personal stories from a family member who lived through a historical era, offering insights into that period.

Digital or Multimedia Narrative

Description: Incorporates multimedia elements like images, videos, or audio to tell a story.

Purpose: Explores storytelling through various digital platforms or formats.

Topic: “A Travel Diary: Exploring Europe Through Vlogs”

Focus: Combines video clips, photos, and personal narration to document a travel experience.

How to Choose a Topic for Your Narrative Essay?

Selecting a compelling topic for your narrative essay is crucial as it sets the stage for your storytelling. Choosing a boring topic is one of the narrative essay mistakes to avoid . Here’s a detailed guide on how to choose the right topic:

Reflect on Personal Experiences

- Significant Moments:

Moments that had a profound impact on your life or shaped your perspective.

Example: A moment of triumph, overcoming a fear, a life-changing decision, or an unforgettable experience.

- Emotional Resonance:

Events that evoke strong emotions or feelings.

Example: Joy, fear, sadness, excitement, or moments of realization.

- Lessons Learned:

Experiences that taught you valuable lessons or brought about personal growth.

Example: Challenges that led to personal development, shifts in mindset, or newfound insights.

Explore Unique Perspectives

- Uncommon Experiences:

Unique or unconventional experiences that might captivate the reader’s interest.

Example: Unusual travels, interactions with different cultures, or uncommon hobbies.

- Different Points of View:

Stories from others’ perspectives that impacted you deeply.

Example: A family member’s story, a friend’s experience, or a historical event from a personal lens.

Focus on Specific Themes or Concepts

- Themes or Concepts of Interest:

Themes or ideas you want to explore through storytelling.

Example: Friendship, resilience, identity, cultural diversity, or personal transformation.

- Symbolism or Metaphor:

Using symbols or metaphors as the core of your narrative.

Example: Exploring the symbolism of an object or a place in relation to a broader theme.

Consider Your Audience and Purpose

- Relevance to Your Audience:

Topics that resonate with your audience’s interests or experiences.

Example: Choose a relatable theme or experience that your readers might connect with emotionally.

- Impact or Message:

What message or insight do you want to convey through your story?

Example: Choose a topic that aligns with the message or lesson you aim to impart to your readers.

Brainstorm and Evaluate Ideas

- Free Writing or Mind Mapping:

Process: Write down all potential ideas without filtering. Mind maps or free-writing exercises can help generate diverse ideas.

- Evaluate Feasibility:

The depth of the story, the availability of vivid details, and your personal connection to the topic.

Imagine you’re considering topics for a narrative essay. You reflect on your experiences and decide to explore the topic of “Overcoming Stage Fright: How a School Play Changed My Perspective.” This topic resonates because it involves a significant challenge you faced and the personal growth it brought about.

Narrative Essay Topics

50 easy narrative essay topics.

- Learning to Ride a Bike

- My First Day of School

- A Surprise Birthday Party

- The Day I Got Lost

- Visiting a Haunted House

- An Encounter with a Wild Animal

- My Favorite Childhood Toy

- The Best Vacation I Ever Had

- An Unforgettable Family Gathering

- Conquering a Fear of Heights

- A Special Gift I Received

- Moving to a New City

- The Most Memorable Meal

- Getting Caught in a Rainstorm

- An Act of Kindness I Witnessed

- The First Time I Cooked a Meal

- My Experience with a New Hobby

- The Day I Met My Best Friend

- A Hike in the Mountains

- Learning a New Language

- An Embarrassing Moment

- Dealing with a Bully

- My First Job Interview

- A Sporting Event I Attended

- The Scariest Dream I Had

- Helping a Stranger

- The Joy of Achieving a Goal

- A Road Trip Adventure

- Overcoming a Personal Challenge

- The Significance of a Family Tradition

- An Unusual Pet I Owned

- A Misunderstanding with a Friend

- Exploring an Abandoned Building

- My Favorite Book and Why

- The Impact of a Role Model

- A Cultural Celebration I Participated In

- A Valuable Lesson from a Teacher

- A Trip to the Zoo

- An Unplanned Adventure

- Volunteering Experience

- A Moment of Forgiveness

- A Decision I Regretted

- A Special Talent I Have

- The Importance of Family Traditions

- The Thrill of Performing on Stage

- A Moment of Sudden Inspiration

- The Meaning of Home

- Learning to Play a Musical Instrument

- A Childhood Memory at the Park

- Witnessing a Beautiful Sunset

Narrative Essay Topics for College Students

- Discovering a New Passion

- Overcoming Academic Challenges

- Navigating Cultural Differences

- Embracing Independence: Moving Away from Home

- Exploring Career Aspirations

- Coping with Stress in College

- The Impact of a Mentor in My Life

- Balancing Work and Studies

- Facing a Fear of Public Speaking

- Exploring a Semester Abroad

- The Evolution of My Study Habits

- Volunteering Experience That Changed My Perspective

- The Role of Technology in Education

- Finding Balance: Social Life vs. Academics

- Learning a New Skill Outside the Classroom

- Reflecting on Freshman Year Challenges

- The Joys and Struggles of Group Projects

- My Experience with Internship or Work Placement

- Challenges of Time Management in College

- Redefining Success Beyond Grades

- The Influence of Literature on My Thinking

- The Impact of Social Media on College Life

- Overcoming Procrastination

- Lessons from a Leadership Role

- Exploring Diversity on Campus

- Exploring Passion for Environmental Conservation

- An Eye-Opening Course That Changed My Perspective

- Living with Roommates: Challenges and Lessons

- The Significance of Extracurricular Activities

- The Influence of a Professor on My Academic Journey

- Discussing Mental Health in College

- The Evolution of My Career Goals

- Confronting Personal Biases Through Education

- The Experience of Attending a Conference or Symposium

- Challenges Faced by Non-Native English Speakers in College

- The Impact of Traveling During Breaks

- Exploring Identity: Cultural or Personal

- The Impact of Music or Art on My Life

- Addressing Diversity in the Classroom

- Exploring Entrepreneurial Ambitions

- My Experience with Research Projects

- Overcoming Impostor Syndrome in College

- The Importance of Networking in College

- Finding Resilience During Tough Times

- The Impact of Global Issues on Local Perspectives

- The Influence of Family Expectations on Education

- Lessons from a Part-Time Job

- Exploring the College Sports Culture

- The Role of Technology in Modern Education

- The Journey of Self-Discovery Through Education

Narrative Essay Comparison

Narrative essay vs. descriptive essay.

Here’s our first narrative essay comparison! While both narrative and descriptive essays focus on vividly portraying a subject or an event, they differ in their primary objectives and approaches. Now, let’s delve into the nuances of comparison on narrative essays.

Narrative Essay:

Storytelling: Focuses on narrating a personal experience or event.

Chronological Order: Follows a structured timeline of events to tell a story.

Message or Lesson: Often includes a central message, moral, or lesson learned from the experience.

Engagement: Aims to captivate the reader through a compelling storyline and character development.

First-Person Perspective: Typically narrated from the writer’s point of view, using “I” and expressing personal emotions and thoughts.

Plot Development: Emphasizes a plot with a beginning, middle, climax, and resolution.

Character Development: Focuses on describing characters, their interactions, emotions, and growth.

Conflict or Challenge: Usually involves a central conflict or challenge that drives the narrative forward.

Dialogue: Incorporates conversations to bring characters and their interactions to life.

Reflection: Concludes with reflection or insight gained from the experience.

Descriptive Essay:

Vivid Description: Aims to vividly depict a person, place, object, or event.

Imagery and Details: Focuses on sensory details to create a vivid image in the reader’s mind.

Emotion through Description: Uses descriptive language to evoke emotions and engage the reader’s senses.

Painting a Picture: Creates a sensory-rich description allowing the reader to visualize the subject.

Imagery and Sensory Details: Focuses on providing rich sensory descriptions, using vivid language and adjectives.

Point of Focus: Concentrates on describing a specific subject or scene in detail.

Spatial Organization: Often employs spatial organization to describe from one area or aspect to another.

Objective Observations: Typically avoids the use of personal opinions or emotions; instead, the focus remains on providing a detailed and objective description.

Comparison:

Focus: Narrative essays emphasize storytelling, while descriptive essays focus on vividly describing a subject or scene.

Perspective: Narrative essays are often written from a first-person perspective, while descriptive essays may use a more objective viewpoint.

Purpose: Narrative essays aim to convey a message or lesson through a story, while descriptive essays aim to paint a detailed picture for the reader without necessarily conveying a specific message.

Narrative Essay vs. Argumentative Essay

The narrative essay and the argumentative essay serve distinct purposes and employ different approaches:

Engagement and Emotion: Aims to captivate the reader through a compelling story.

Reflective: Often includes reflection on the significance of the experience or lessons learned.

First-Person Perspective: Typically narrated from the writer’s point of view, sharing personal emotions and thoughts.

Plot Development: Emphasizes a storyline with a beginning, middle, climax, and resolution.

Message or Lesson: Conveys a central message, moral, or insight derived from the experience.

Argumentative Essay:

Persuasion and Argumentation: Aims to persuade the reader to adopt the writer’s viewpoint on a specific topic.

Logical Reasoning: Presents evidence, facts, and reasoning to support a particular argument or stance.

Debate and Counterarguments: Acknowledge opposing views and counter them with evidence and reasoning.

Thesis Statement: Includes a clear thesis statement that outlines the writer’s position on the topic.

Thesis and Evidence: Starts with a strong thesis statement and supports it with factual evidence, statistics, expert opinions, or logical reasoning.

Counterarguments: Addresses opposing viewpoints and provides rebuttals with evidence.

Logical Structure: Follows a logical structure with an introduction, body paragraphs presenting arguments and evidence, and a conclusion reaffirming the thesis.

Formal Language: Uses formal language and avoids personal anecdotes or emotional appeals.

Objective: Argumentative essays focus on presenting a logical argument supported by evidence, while narrative essays prioritize storytelling and personal reflection.

Purpose: Argumentative essays aim to persuade and convince the reader of a particular viewpoint, while narrative essays aim to engage, entertain, and share personal experiences.

Structure: Narrative essays follow a storytelling structure with character development and plot, while argumentative essays follow a more formal, structured approach with logical arguments and evidence.

In essence, while both essays involve writing and presenting information, the narrative essay focuses on sharing a personal experience, whereas the argumentative essay aims to persuade the audience by presenting a well-supported argument.

Narrative Essay vs. Personal Essay

While there can be an overlap between narrative and personal essays, they have distinctive characteristics:

Storytelling: Emphasizes recounting a specific experience or event in a structured narrative form.

Engagement through Story: Aims to engage the reader through a compelling story with characters, plot, and a central theme or message.

Reflective: Often includes reflection on the significance of the experience and the lessons learned.

First-Person Perspective: Typically narrated from the writer’s viewpoint, expressing personal emotions and thoughts.

Plot Development: Focuses on developing a storyline with a clear beginning, middle, climax, and resolution.

Character Development: Includes descriptions of characters, their interactions, emotions, and growth.

Central Message: Conveys a central message, moral, or insight derived from the experience.

Personal Essay:

Exploration of Ideas or Themes: Explores personal ideas, opinions, or reflections on a particular topic or subject.

Expression of Thoughts and Opinions: Expresses the writer’s thoughts, feelings, and perspectives on a specific subject matter.

Reflection and Introspection: Often involves self-reflection and introspection on personal experiences, beliefs, or values.

Varied Structure and Content: Can encompass various forms, including memoirs, personal anecdotes, or reflections on life experiences.

Flexibility in Structure: Allows for diverse structures and forms based on the writer’s intent, which could be narrative-like or more reflective.

Theme-Centric Writing: Focuses on exploring a central theme or idea, with personal anecdotes or experiences supporting and illustrating the theme.

Expressive Language: Utilizes descriptive and expressive language to convey personal perspectives, emotions, and opinions.

Focus: Narrative essays primarily focus on storytelling through a structured narrative, while personal essays encompass a broader range of personal expression, which can include storytelling but isn’t limited to it.

Structure: Narrative essays have a more structured plot development with characters and a clear sequence of events, while personal essays might adopt various structures, focusing more on personal reflection, ideas, or themes.

Intent: While both involve personal experiences, narrative essays emphasize telling a story with a message or lesson learned, while personal essays aim to explore personal thoughts, feelings, or opinions on a broader range of topics or themes.

A narrative essay is more than just telling a story. It’s also meant to engage the reader, get them thinking, and leave a lasting impact. Whether it’s to amuse, motivate, teach, or reflect, these essays are a great way to communicate with your audience. This interesting narrative essay guide was all about letting you understand the narrative essay, its importance, and how can you write one.

Order Original Papers & Essays

Your First Custom Paper Sample is on Us!

Timely Deliveries

No Plagiarism & AI

100% Refund

Try Our Free Paper Writing Service

Related blogs.

Connections with Writers and support

Privacy and Confidentiality Guarantee

Average Quality Score

100+ Narrative Essay Topics for your Next Assignment

Writing a narrative essay should be fun and easy in theory. Just tell your readers a story, often about yourself. Who knows you better than you? You should ace this!

Unfortunately, narrative writing can be very difficult for some. When a teacher leaves the topic choice wide open, it’s tough to even know what to write about. What anecdote from your life is worth sharing? What story is compelling enough to fill an entire essay?

Narrative writing will show up for the rest of your life. You’ll need to tell life stories in college essays, in grad school applications, in wedding speeches, and more. So learning how to write a narrative essay is a skill that will stick with you forever.

But where do you begin?

You can always check out essay examples to get you started, but this will only get you so far.

At the end of the day, you still need to come up with a story of your own. This is often the toughest part.

To help you get things kicked off, we’ve put together this list of more than a hundred topic ideas that could easily be turned into narrative essays. Take a look and see what stands out to you!

Choosing a Topic

Narrative essays fall into several categories. Your first task is to narrow down your choices by choosing which category you want to explore.

Each of these categories offers a stepping off point from which you can share a personal experience. If you have no idea where to begin, reflecting on these main categories is a great place to start. You can pick and choose what you feel comfortable sharing with your readers. This list is not exclusive—there are other areas of your life you can explore. These are just some of the biggies.

As you explore categories, think about which one would be the best fit for your assignment. Which category do you have the strongest ideas for? Which types of stories do you tell the best?

These categories include:

Childhood Tales

Educational background, travel and adventure, friends and relationships, experiences and defining moments, my favorite things, ethics and values.

Once you’ve selected a category, it’s time to see which topic piques your interest and might intrigue your audience as well. These topics are all a natural fit for a story arc , which is a central part of a narrative essay.

Writing about your childhood can be a great choice for a narrative essay. We are growing and learning during this delicate and often awkward time. Sharing these moments can be funny, endearing, and emotional. Most people can relate to childhood events because we have all survived it somehow!

- A childhood experience that defined who I am today

- A childhood experience that made me grow up quickly

- My best/worst childhood memory

- My favorite childhood things (games, activities, stories, fairy tales, TV shows, etc.)

- What I remember most about my childhood

- How I used to celebrate holidays/birthdays

- My best/worst holiday/birthday memory

- What I used to believe was true

- The oldest memory I have

- The most valuable possession from my childhood

- What I would tell my younger self

- What my friends were like when I was younger

Your educational experience offers a wealth of ideas for an essay . How you’ve learned and have been inspired can help others be inspired too. Although we were all educated in one way or another, your educational experience is uniquely your own to share.

- First day of school/junior high/high school/college

- First/most memorable school event

- My favorite/worst school years

- My favorite/worst teachers

- My favorite/worst school subjects

- What recess was like for me

- My experiences in the school cafeteria

- How I succeeded/failed in certain classes

- Life as a student (elementary, junior high, high school, college)

- The best/worst assignment I ever completed for a class

- Why I chose my college

- First novel I read for school

- First speech I had to give

People love to read about adventures. Sharing your travel stories transports your reader to a different place. And we get to see it through your eyes and unique perspective. Writing about travel experiences can allow your passion for diving into the world shine through.

- My first time traveling alone

- My first time traveling out of the country

- The place I travel where I feel most at home

- My favorite/worst travel experience

- The time I spent living in a hostel/RV

- The time I spent backpacking around a country

- Traveling with friends/family/significant other

- Best/worst family vacation

- Most memorable travel experience ever

- Places I want to visit

- Why I travel

- Why I cruise/climb mountains/camp/fly/drive

- Trying to speak another language

- How I prefer to travel

- How I pack to travel

The good, the bad, and the ugly. We all have family stories that range from jubilantly happy and hilarious to sad and more serious. Writing about family can show your reader about who you are and where you come from.

- Family traditions that you enjoy/dislike

- What your parents/siblings are like

- What your family members (mom, dad, grandparents, siblings, etc.) have taught you

- What being the oldest/youngest/middle/only child was like

- Family members who made the most impact on your life

- Most memorable day with a family member

- How a pet changed my family’s life/my life

Friends, enemies, and loved ones come in and out of our lives for a reason. And they provide great material for writing. If relationships exist to teach you something, what have you learned? Writing about those you’ve connected with demonstrates how others have influenced your life.

- My most important relationship

- How I work on my relationships

- What I value in my relationships

- My first love/relationship/breakup

- Losing/Gaining a close friend

- How my friendships have changed/evolved

- The person I’m afraid of losing the most

- How technology has affected my relationships

- The worst argument I’ve had with someone

- What happened when I was rejected

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times... sharing your best times and sharing your worst times can make great stories. These highs and lows can be emotional, funny, and thought-provoking.

- The event that most defines who I am today

- The best/worst day of my life

- The most embarrassing/frightening moment of my life

- A moment that taught me something

- A moment where I succeeded/failed

- A time when I was hurt (physically or emotionally)

- A time when I gave up hope

- An experience when I had to overcome challenges (fear, intimidation, rejection, etc.)

- My greatest accomplishment

- The time I learned to accept/love/be okay with myself

- The most difficult time in my life

- The toughest thing I’ve ever done

- My first time surviving something alone

Explaining to others what you love and why can really paint a picture of who you are and what you value. It’s important to note that simply sharing a favorite isn’t a very deep topic. However, you can take this topic deeper by expressing how this favorite has impressed you, inspired you, and affected your life.

- My favorite author/poet/playwright

- My favorite movie/book/song/play/character

- My favorite actor/actress/director

- My favorite singer/musician

- My role model

- What I like to do to relax

- My favorite activities/games/sports

- How I handle stress and tough times

- Why I dance/sing/write/journal/play sports/bake

Where you stand on deep issues tells a lot about you. Taking a stance and explaining your opinion on tough topics reveals some insight into your ethical reasoning.

- The most difficult decision I have made

- How I treat people/strangers

- A time I faced a moral/ethical dilemma

- A decision I regret

- A lie I have told

- When I rebelled against someone in authority

- My most important life rule

- The principle I always live by

Situational prompts allow you to step out of your past and picture a different future. If digging into your past experiences seems scary and intimidating, then look to your future. What you imagine can be insightful about your life and where you see yourself heading.

- If I had a million dollars...

- If I were famous...

- If I could change history...

- If I had no fear...

- If I could change one thing about myself...

- If I had one extra hour a day...

- If I could see the future...

- If I could change the world...

- If I could have one do-over in life...

Writing a narrative essay can seem daunting at first. Sharing a bit of yourself with the world is a scary thing sometimes. Choosing the right topic, however, can make the process much smoother and easier.

Browsing through topic ideas can inspire you to pick a topic you feel you can tell a story about and that can take up a full essay. Once you have a quality story to tell, the rest of the pieces will fall into place.

How to Write Essay Titles and Headers

Don’t overlook the title and section headers when putting together your next writing assignment. Follow these pointers for keeping your writing organized and effective.

101 Standout Argumentative Essay Topic Ideas

Need a topic for your upcoming argumentative essay? We've got 100 helpful prompts to help you get kickstarted on your next writing assignment.

Writing a Standout College Admissions Essay

Your personal statement is arguably the most important part of your college application. Follow these guidelines for an exceptional admissions essay.

Assessing the Classification of the Dominican Republic as a Third World Country

This essay is about evaluating whether the Dominican Republic can be classified as a Third World country. It examines the country’s significant economic growth, driven by tourism and manufacturing, alongside persistent challenges like poverty, income inequality, and limited access to quality healthcare and education. The essay discusses the country’s relative political stability and infrastructure development, noting disparities between urban and rural areas. It argues that the term “Third World country” is outdated and that the Dominican Republic is better described as an emerging market. This classification reflects its progress and ongoing challenges, providing a more nuanced understanding of its development status.

How it works

The term “Third World country” frequently denotes territories with diminished economic advancement, inferior standards of livelihood, and amplified degrees of destitution and political volatility relative to more industrialized realms. Originally formulated during the Cold War to delineate countries not allied with NATO or the Communist Bloc, the phrase has since transformed, often carrying a derogatory undertone. When scrutinizing whether the Dominican Republic conforms to this categorization, it is imperative to scrutinize diverse socio-economic benchmarks and the country’s developmental trajectory.