- Open access

- Published: 22 March 2021

Patient safety from the perspective of quality management frameworks: a review

- Amrita Shenoy ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8355-7792 1

Patient Safety in Surgery volume 15 , Article number: 12 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Patient safety is one of the overarching goals of patient care and quality management. Of the many quality management frameworks, Beauchamp and Childress’s four principles of biomedical ethics presents aspects of patient centeredness in clinical care. The Institute of Medicine’s six aims for improvement encapsulates elements of high-quality patient care. The Institute of Healthcare Improvement’s Triple Aim focuses on three aspects of care, cost, and health. Given the above frameworks, the present review was designed to emphasize the initiatives the system has taken to address various efforts of improving quality and patient safety. We, hereby, present a contemplative review of the concepts of informed consent, informed refusal, healthcare laws, policy programs, and regulations. The present review, furthermore, outlines measures and policies that management and administration implement and enforce, respectively, to ensure patient centered care. We, conclusively, explore prototype policies such as the Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment Program that imbues the elements of quality management frameworks, Hospital-Acquired Conditions Reduction Program that supports patient safety, and Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program that focuses on curbing readmissions.

The logistics of patient care and healthcare management revolve around many aspects of optimized high-quality care. The Joint Commission (TJC), Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA), and The Magnet Recognition Program signify healthcare accreditation, performance excellence, and nursing excellence, respectively [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. TJC is the recognized global leader of healthcare accreditation [ 4 ]. It is an independent not-for-profit organization that offers an unbiased assessment of quality achievement in patient care and safety [ 4 ]. MBNQA is the nation’s highest presidential honor for performance excellence [ 5 ]. The Magnet Recognition Program designates organizations worldwide where nursing leaders successfully align their nursing strategic goals to improve the organization’s patient outcomes [ 6 ]. In addition to the above healthcare recognition, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) categorizes aspects of care delivery with its six aims for improvement [ 7 ]. The Institute of Healthcare Improvement’s (IHI's) Triple Aim comprises of three aspects: improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing per capita costs of healthcare.

We, hereby, present a synthesis of how the perspectives of biomedical ethics, six aims for improvement, and the Triple Aim converge into a focal point of preserving patient safety and promoting improvement in care delivery. The present review elaborates and explains the clinical and managerial roles inherent in the logistics of patient safety in emergencies and non-emergencies. The impetus here is to exemplify existing policies supporting patient centeredness while preserving the parameters that improve patient care, preserve quality, and promote patient safety.

As one of the cornerstones of high-quality healthcare, patient safety is intrinsic to all healthcare professionals. Clinicians are involved in direct patient care. However, does that imply that policymakers, leadership, and managers are separate and distinct components not involved in patient safety? The answer to the above question is not likely because these entities devise and enforce policies to preserve and augment patient safety in communities, institutions, and departments. At the macro-level, policymakers devise and recommend healthcare policies that at the micro-level, leadership, management, and clinicians enforce, adopt, and practice, respectively, at the point of patient care.

Research questions and objectives

Past literature establishes quality management frameworks such as Beauchamp and Childress’s Principles of Biomedical Ethics, six aims for improvement and the Triple Aim. The above frameworks, broadly, capture the patient’s needs/preferences while aligning with improvement in care delivery. However, there are instances in which patients when presented in an unconscious or inebriated state cannot communicate their treatment preferences. Given the above case, the first research question is: what are some recourses that providers can choose to adopt as safe harbors while treating such patients? The second research question is: what are the practices that clinicians could potentially adhere when the patient consents or refuses to consent? As a close follow-up, the third research question is: what is the role of administration in implementing policies that fall outside the purview of already enforced laws? The objective of the present review is threefold. First, we aim to propose answers to the dos and don’ts that clinicians could potentially adopt in emergency and non-emergency cases, given the concepts of informed consent and informed refusal. Second, we attempt to explain how hospital leadership can best facilitate patient safety and manage risk while facilitating high-quality patient care. Finally, we explore prototype policies such as the Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment program, Quadruple Aim, Hospital-Acquired Conditions Reduction Program, and Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program which have been implemented more recently as systemic initiatives to preserve patient safety and promote measures in care delivery.

Literature review

Quality management frameworks preserving patient safety: an overview of three established frameworks, beauchamp and childress’s principles of biomedical ethics.

Faculty in medicine and surgery have a substantial role in ethically creating a culture of safety via medical and surgical treatments for patients. In this context, four principles of biomedical ethics come into the picture. Those principles are autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, and justice [ 9 ]. The above four principles are the four pillars of medical ethics and form the basis of ethical practice in medicine and surgery. Some more aspects of biomedical ethics stemming from the above four principles are considered in ethical medical and surgical decision making [ 10 ]. A list of those additional aspects are as follows: [ 10 ].

Truthfulness, Full Disclosure, and Confidentiality: On the one hand, truthfulness is not distorting facts while presenting information to the patient; full disclosure is accurately and completely informing the details of the patient’s medical condition. On the other hand, confidentiality is the principle of not revealing information about the patient’s medical condition to third parties [ 10 ].

Autonomy and Freedom: Autonomy is the principle of providing the patient discretion, freedom, and independence to choose treatment preferences. This concept particularly comes into the spotlight in end-of-life hospice treatments and medical terminations of pregnancies [ 10 ].

Beneficence is the principle of doing good and inflicting the least harm to the patient.

The Institute of medicine’s six aims for improvement model

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Patient Safety Network expands upon the definition of prevention of harm as, “freedom from accidental or preventable injuries produced by medical care” [ 11 ]. Furthermore, the IOM introduced six aims for improvement in healthcare to meet the patient’s healthcare needs and preserve patient safety. Those six aims are as follows: [ 7 ].

Safe: avoiding injuries to patients from the care that is intended to help them. Patient safety can be a system-wide approach when patients see measures adopted and practiced that create a safe environment [ 7 ].

Efficient: avoiding waste including waste from equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy. Healthcare wastes are also in the form of defensive medicine, malpractice litigation, systemic complexities, and administrative fraud and abuse. Cost-effective care potentially supports efficiency in healthcare [ 7 ].

Effective: providing services based on scientific knowledge to all those who could benefit. In this context, Evidence Based Medicine is incorporating scientific knowledge into treatment and procedure options [ 7 ].

Patient-centered: providing care that is respectful of and responsive to the patient’s needs, preferences, and values. Delivery of care is considered to be patient-centered when the patient can choose certain aspects of care. This approach towards patient care prospectively ingrains elements of cooperation and collaboration [ 7 ].

Timely: reducing waiting times and detrimental delays for both, recipients and providers of care. Waits and harmful delays potentially produce life threatening illnesses worsening quality outcomes throughout the continuum of a patient care [ 7 ].

Equitable: providing care that is consistent and does not vary in quality based on personal aspects such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status, etc. [ 7 ].

As per the IOM’s six aims for improvement, first, healthcare processes need to be safe which implies the provider makes an active attempt to ensure patient safety. Second, patient care prospectively needs to be aligned with recent developments to be potentially effective. Third, patient-centered care takes into consideration the patient’s culture, dietary and personal preferences incorporated into care delivery methods. The above concept plays an important role in end-of-life or hospice care provided to the elderly. Fourth, timeliness is providing and receiving care in a manner that reduces waiting times and delays. On the one hand, unforeseen wait periods may delay care and result in serious unintended harm to patients. On the other hand, the provision of timely care is essential to patient safety. Fifth, focusing on eliminating wastes and redundant processes could potentially help conserving resources and making care more affordable. Finally, providing equitable care is that which does not vary in terms of race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and income [ 7 ].

The Institute of healthcare improvement’s triple aim model

The Institute of Healthcare Improvement’s (IHI’s) Triple Aim model synthesizes and incorporates aspects of care, cost, and health [ 8 ]. The IHI’s Triple Aim model involves the following three components: [ 8 ].

Improving the experience of care: Implementing Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) and Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) surveys are few of the many ways of recording patient experience of care [ 12 , 13 ]. The National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB), additionally, assists in promoting quality health care and deterring fraud and abuse within health care delivery systems [ 14 ].

Reducing per capita costs of care: Cost of care could be reduced with the help of using generic drugs instead of brand name drugs for prescriptions, as an example [ 8 ].

Improving the health of populations [ 8 ].

The IHI's Triple Aim is a framework that describes an approach with a threefold purpose. First, improving the experience of care regarding healthcare quality, second, decreasing per capita costs of care that aims at reducing wastes and variation in healthcare, and third, improving the health of populations. The IHI’s Triple Aim model has universal applications that cover medical treatment, surgical care, therefore, opening avenues to solve administrative complexities for preserving health and wellness in populations.

The first component of the Triple Aim, improving the experience of care applies to advances in medical technology making a positive impact in the patient experience of care [ 8 ]. The second component of the Triple Aim, reducing per capita costs of care, applies to implementing telemedicine and telehealth projects, as an example. Telemedicine brings to fruition, efficient and timely care when physicians may not be in the vicinity of the patient [ 8 ]. On the one hand, one of pros of telemedicine is the potential to enhance access to care. On the other hand, it introduces this concept to some practitioners and patients who have little to no experience with e-health. The third component of the Triple Aim, improving the overall health of the population applies to facilitating a combination of the above two aims. The IHI’s Triple Aim model, therefore, is a three-pointed framework in which the first two aims are intrinsic to the third aim, improving population health [ 8 ].

The roles of clinical faculty and administration in patient safety: adoption and implementation of best practices in emergency and non-emergency cases

Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) is a federal law that requires anyone coming to an emergency department to be stabilized and treated, regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay [ 15 ]. As per EMTALA, the patient has a right to be treated and clinicians are bound to provide treatment [ 15 ]. In this context, let us consider an example of an unconscious patient in the emergency department that does not culturally prefer receiving blood transfusions. In the above case, hypothetically, if the treating provider is not knowledgeable of the cultural preference of the unconscious patient and proceeds to revive the patient via a blood transfusion, then, was patient centered care provided? The answer likely lies in the provider’s assessment in the context of EMTALA. The assessment, first and foremost, relates to the binding duty of the clinician to provide care to every patient, especially in times of emergencies.

The dynamics of the above hypothetical scenario entirely changes in non-emergency situations in which patients can choose a provider to treat them; and reciprocally, even providers can choose whom to treat. The rationale behind this is the physician-patient relationship that specifies the terms and conditions of a physician-patient contract [ 16 ]. This legal relationship is based on contract principles because the physician agrees to provide treatment in return for payment in the presence of the contract [ 16 ]. The law usually imposes no duty on the physician to treat the patient in the absence of a physician-patient contract [ 16 ].

In the process of providing treatment, obtaining informed consent is the concept in which the clinician explains the proposed line of treatment, duration, benefits, risks of opting in as well as opting out of the treatment, alternatives to the proposed treatment with an opportunity to answer patient questions [ 17 ]. In 1914, an American judge Benjamin Cardozo composed the foundational principle of informed consent as, “Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body; and a surgeon who performs an operation without his patient’s consent commits an assault for which he is liable in damages” [ 18 ]. An interesting aspect of treatment in non-emergency cases is when the patient does not agree to informed consent which brings forth the concept of “Informed Refusal” [ 19 , 20 ]. A living will is an example of an informed refusal document in which the patient states his or her end of life preferences [ 21 ]. In the above case, the provider honors the patient’s end of life preferences and/or withholds treatment for the patient as specified in the living will.

The role of leadership is to enforce EMTALA and help clinicians' awareness of informed consent and informed refusal processes in organizations. Moreover, they ensure that providers implement the above policies regarding patient preferences. In medical cases that fall outside the purview of the already enforced laws, leadership can prospectively make rules but with caution that those rules are not against public policy.

Macro-level healthcare programs focusing on patient safety: prototype policies

Delivery system reform incentive payment program: focusing on alignment with quality management frameworks.

The Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program is one prototype policy that incorporates six aims for improvement and the Triple Aim model. DSRIP has multiple healthcare projects that improve health statuses incorporating numerous metrics and milestones in primary care, specialty care, chronic care, navigation and case management, disease prevention and wellness, and general categories [ 23 , 24 ]. These projects are reimbursed by the State Department of Health in a systematic manner when adopted by healthcare institutions [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ].

DSRIP’s framework involves four components: (1) Infrastructure Development, (2) Program Innovation and Redesign, (3) Quality Improvement, and (4) Improvement in Population Health in states where its projects are implemented [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. In its third year of implementation, the Texas DSRIP program in the southeastern county region had about 172 projects in eight cohorts those being, primary care, emergency care, chronic care, navigation/case management, disease prevention and wellness, behavioral health/substance abuse prevention, and general.[ 22 , 23 , 25 ] Each cohort had a set number of projects that involve meeting patient care milestones and metrics, simultaneously incorporating IOM’s six patient care aims of medical care being safe, efficient, effective, patient centered, timely, and equitable [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ].

DSRIP, with all its projects implemented in the adopted regions and counties has been measured to improve population health [ 25 ]. A metric of measuring improvement in population health within the DSRIP program was preventable hospitalization rate [ 24 ]. The decrease in preventable hospitalization rates may have been attributed to the inherent design and dynamics of the DSRIP policy [ 23 , 24 ]. Those dynamics comprised of factors such as physician-administrator collaboration, mechanisms of incentive payments, types of measures for reporting outcomes in quality, and interplaying healthcare externalities [ 24 ]. In the adopted regions and counties, a statistically significant decrease in preventable hospitalization rates was observed when tested with an interrupted time series method [ 25 ].

There were two phases of the Texas DSRIP program, DSRIP 1.0 and 2.0. It was in DSRIP 2.0 that comprehensive Diabetes Care: eye exam metric improved by 16 % while Influenza immunization improved by 12 % in the latter [ 27 ]. Researchers Revere et al. have identified that in DSRIP 2.0, the metrics for Central Line Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI) rates, Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infections (CAUTI), and Surgical Site Infection (SSI) rates improved by 26 %, 10 %, and 9 %, respectively [ 27 ].

Quadruple aim framework: focusing on the evolution of the triple aim

The Triple Aim, formulated in 2008, drew focus on three aims which were based on care, cost, and health. Sikka and colleagues, in 2015, constructed a fourth aim, improving the experience of providing care. This was made to acknowledge the importance of physicians, nurses, and all employees in “finding joy and meaning in their work and in doing so improving the experience of providing care” [ 28 ]. At the core of the fourth aim is the experience of joy and meaning in providing care making it synonymous with acquiring accomplishment and meaning in their contributions. The Quadruple Aim has broad implications in theory and practice factoring inclusiveness in terms of all members in the healthcare workforce [ 28 ].

Hospital-Acquired conditions reduction program: focusing on patient safety

The Hospital-Acquired Conditions Reduction Program (HACRP) is a Medicare pay-for-performance program that supports the CMS’ long-standing effort to link Medicare payments to healthcare quality in the inpatient hospital setting [ 29 ]. HACRP focuses on specific conditions that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) healthcare- associated infection (HAI) measures which are: [ 30 ] (1) Central Line Associated Blood Stream Infection (CLABSI), (2) Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI), (3) Surgical Site Infection (SSI) for colon and hysterectomy, (4) Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) bacteremia, (5) Clostridium Difficile Infection (CDI).

Additionally, eight Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs) included in the program comprise of: [ 31 ] (1) PSI 03 - Pressure Ulcer Rate, (2) PSI 06 - Iatrogenic Pneumothorax Rate (3) PSI 07 - Central Venous Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection Rate, (4) PSI 08 - Postoperative Hip Fracture Rate, (5) PSI 12 - Perioperative Pulmonary Embolism or Deep Vein Thrombosis Rate, (6) PSI 13 - Postoperative Sepsis Rate, (7) PSI 14 - Postoperative Wound Dehiscence Rate, (8) PSI 15 - Accidental Puncture or Laceration Rate.

Hospital readmissions reduction program: focusing on patient safety

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) is a Medicare value-based purchasing program that reduces payments to hospitals with excess readmissions. The program supports the national goal of improving healthcare by linking payment to the quality of hospital care [ 32 ]. HRRP has a specific focus on the following conditions to reduce readmissions that in turn improve patient safety [ 32 ]. Those conditions are as follows: [ 32 ] (1) Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI), (2) Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), (3) Heart Failure (HF), (4) Pneumonia (5) Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) surgery, and (6) Elective Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty and/or Total Knee Arthroplasty (THA/TKA) [ 32 ].

The purpose of the present review was to analyze patient safety through the lens of the above quality management frameworks. We, specifically, illuminated policies and laws such as EMTALA, informed consent, informed refusal, and living will as examples. In emergency cases, the rules of EMTALA apply whereas in non-emergency cases, the same applies to obtaining informed consent from the patient. In the event the patient refuses treatment, documenting the informed refusal would be ideal. We underscored selective new prototype policies percolating from national policymaking to institutional levels with a focus on the initiatives the system has actively taken to preserve patient safety and promote improvement in care delivery.

Facts about The Joint Commission. Retrieved from https://www.jointcommission.org/about_us/about_the_joint_commission_main.aspx . Accessed 16 Feb 2021

Malcolm Baldrige Award. Retrieved from https://baldrigefoundation.org/ . Accessed 16 Feb 2021

Magnet Recognition Criteria. Retrieved from https://www.mghpcs.org/PCS/Magnet/Documents/Education_Toolbox/01_Intro-Ovrvw/Magnet-Overview-2017.pdf . Accessed 16 Feb 2021.

The Joint Commission is the recognized global leader of healthcare accreditation and offers an unbiased assessment of quality achievement in patient care and safety Retrieved from: https://www.jointcommission.org/accreditation-and-certification/why-the-joint-commission/ . Accessed 16 Feb 2021

The Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award being the nation's highest presidential honor for performance excellence. Retrieved from: https://asq.org/quality-resources/malcolm-baldrige-national-quality-award . Accessed 16 Feb 2021

The Magnet Recognition Program’s alignment of nursing strategic goals to improve the organization’s patient outcomes. Retrieved from: https://www.nursingworld.org/organizational-programs/magnet/ . Accessed 16 Feb 2021

The Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2001.

Google Scholar

Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008;27(3):759–69.

Article Google Scholar

Page K. The four principles: Can they be measured and do they predict ethical decision making? BMC Med Ethics. 2012;13(1):10.

Landau R, Osmo R. Professional and personal hierarchies of ethical principles. Int J Soc Welfare. 2003;12(1):42–9.

Mitchell PH. Defining patient safety and quality care. In: Hughes RG, editor Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. Chapter 1. NBK2681.

Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) Survey of Patient Perspectives. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/HospitalHCAHPS . Accessed 16 Feb 2021.

Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) Survey assessing patient experience. Retrieved from https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/about-cahps/cahps-program/index.html . Accessed 16 Feb 2021

National Practitioner Data Bank Web site. Retrieved from: https://www.npdb.hrsa.gov/topNavigation/aboutUs.jsp . Accessed 16 Feb 2021.

Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA). Retrieved from https://www.acep.org/life-as-a-physician/ethics--legal/emtala/emtala-fact-sheet/ . Accessed 16 Feb 2021.

Showalter JS. The Law of Healthcare Administration. Eighth Edition. Chicago, Washington, DC: Health Administration Press; 2017.

Boland GL. The doctrines of lack of consent and lack of informed consent in medical procedures in Louisiana. La L Rev. 1984;45:1.

Alexis O, Caldwell J. Administration of medicines–the nurse’s role in ensuring patient safety. Brit J Nurs. 2013;22(1):32–5.

Wagner RF Jr, Torres A, Proper S. Informed consent and informed refusal. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21(6):555–9.

Ridley DT. Informed consent, informed refusal, informed choice–what is it that makes a patient’s medical treatment decisions informed? Med Law. 2001;20(2):205–14.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Emanuel L. Living wills can help doctors and patients talk about dying. West J Med. 2000;173(6):368–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/ewjm.173.6.368 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Shenoy A, Revere L, Begley C, Linder S, Daiger S. The Texas DSRIP program: An exploratory evaluation of its alignment with quality assessment models in healthcare. Int J Healthcare Manage. 2017;12(2):165–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2017.1397339 .

Begley C, Hall J, Shenoy A, Hanke J, Wells R, Revere L, Lievsay N. Design and implementation of the Texas Medicaid DSRIP program. Popul Health Manag. 2017;20(2):139–45.

Shenoy A, Begley C, Revere L, Linder S, Daiger SP. Delivery system innovation and collaboration: A case study on influencers of preventable hospitalizations. Int J Healthcare Manage. 2017:1–8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2017.14057772017.1405777

Shenoy AG, Begley CE, Revere L, Linder SH, Daiger SP. Innovating patient care delivery: DSRIP’s interrupted time series analysis paradigm. Healthcare. 2019;7(1):44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.11.004 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Shenoy AG. DSRIP’s innovation and collaboration in population health management: A cross-sectional segmented time series model. Health Serv Manage Res. 2020;33(1):2–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951484819868679 .

Revere L, Kavarthapu N, Hall J, Begley C. Achieving triple aim outcomes: An evaluation of the Texas medicaid waiver. Inquiry. 2020;57:46958020923547. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958020923547 .

Sikka R, Morath JM, Leape L. The Quadruple aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Qual Safety. 2015;24:608–10.

Hospital Acquired Conditions Reduction Program. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-ServicePayment/AcuteInpatientPPS/HAC-Reduction-Program . Accessed 16 Feb 2021.

HACRP List of Conditions. Retrieved from https://qualitynet.cms.gov/inpatient/hac Accessed 16 Feb 2021.

List of PSI 90. Retrieved from https://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/Modules/PSI_TechSpec_ICD10_v2020.aspx . Accessed 16 Feb 2021

Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program . Accessed 16 Feb 2021

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest and financial disclosure statement

The authors collectively declare that there is no conflict of interest and have no financial interests with any sponsoring organization, for-profit or not-for-profit.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Public Affairs, School of Health and Human Services, Healthcare Administration Program, University of Baltimore, 1420 N. Charles Street, MD, 21201, Baltimore, USA

Amrita Shenoy

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The author read and approved the final manuscript. AS conducted the literature search and review, drafted the manuscript and responded the reviewer's comments.

Authors' information

Dr. Amrita Shenoy is an Assistant Professor of Healthcare Admin-istration at the University of Baltimore and the Winner of the 2011 McGraw-Hill/Irwin Distinguished Paper Award. She leverageseconometrics to quantify policy impact and qualitatively exploreshealthcare laws and policies for a deeper comprehension of its ana-lytical spectra. Dr. Shenoy received her PhD from the University ofTexas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health,MHA/MBA from the University of Houston — Clear Lake and MScfrom Nottingham Trent University, United Kingdom. Her researchareas spotlight topics in healthcare law, policy, and quality with abroad emphasis on public health and healthcare management.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Amrita Shenoy .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval and consent to participate on data involving the use of any animal/human tissue Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Shenoy, A. Patient safety from the perspective of quality management frameworks: a review. Patient Saf Surg 15 , 12 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-021-00286-6

Download citation

Received : 04 January 2021

Accepted : 23 February 2021

Published : 22 March 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-021-00286-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Quality management frameworks

- IOM’s six aims for improvement

- IHI’s Triple Aim

- Patient safety

- Patient centeredness

- High‐quality clinical care

Patient Safety in Surgery

ISSN: 1754-9493

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 05 December 2019

Networked information technologies and patient safety: a protocol for a realist synthesis

- Justin Keen 1 ,

- Joanne Greenhalgh 2 ,

- Rebecca Randell 3 ,

- Peter Gardner 4 ,

- Justin Waring 5 ,

- Roberta Longo 1 ,

- Jon Fistein 1 ,

- Maysam Abdulwahid 1 ,

- Natalie King 1 &

- Judy Wright 1

Systematic Reviews volume 8 , Article number: 307 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

1852 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

There is a widespread belief that information technologies will improve diagnosis, treatment and care. Evidence about their effectiveness in health care is, however, mixed. It is not clear why this is the case, given the remarkable advances in hardware and software over the last 20 years. This review focuses on interoperable information technologies, which governments are currently advocating and funding. These link organisations across a health economy, with a view to enabling health and care professionals to coordinate their work with one another and to access patient data wherever it is stored. Given the mixed evidence about information technologies in general, and current policies and funding, there is a need to establish the value of investments in this class of system. The aim of this review is to establish how, why and in what circumstances interoperable systems affect patient safety.

A realist synthesis will be undertaken, to understand how and why inter-organisational systems reduce patients’ clinical risks, or fail to do so. The review will follow the steps in most published realist syntheses, including (1) clarifying the scope of the review and identifying candidate programme and mid-range theories to evaluate, (2) searching for evidence, (3) appraising primary studies in terms of their rigour and relevance and extracting evidence, (4) synthesising evidence, (5) identifying recommendations, based on assessment of the extent to which findings can be generalised to other settings.

The findings of this realist synthesis will shed light on how and why an important class of systems, that span organisations in a health economy, will contribute to changes in patients’ clinical risks. We anticipate that the findings will be generalizable, in two ways. First, a refined mid-range theory will contribute to our understanding of the underlying mechanisms that, for a range of information technologies, lead to changes in clinical practices and hence patients’ risks (or not). Second, many governments are funding and implementing cross-organisational IT networks. The findings can inform policies on their design and implementation.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42017073004

Peer Review reports

There is a widespread belief, particularly among policy makers, that information technologies will improve diagnosis, treatment and care [ 1 ]. Evidence about the effectiveness of a range of IT applications is, however, mixed [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. A comprehensive review by Brenner and colleagues covered a number of technologies and focused on safety-related end-points including mortality, infection rates and medication error rates [ 2 ]. Twenty-five out of 69 studies included in their review reported a statistically significant positive effect. The other 44 studies reported no or negative effects. More recent systematic reviews report broadly similar findings [ 6 , 7 ]. Authors stress that evidence is uneven in both coverage and quality, and care needs to be taken in interpreting the findings, but the general picture is clear.

There is, therefore, a need to understand why the evidence has, to date, fallen short of expectations. We seek to shed light on the question in this systematic review. It focuses on the effects of a particular class of IT systems, interoperable systems, on patient safety. The term ‘system’ here refers to the combination of technologies and the people who used them. In a well-designed system, technologies are seamlessly integrated into users’ working practices. In poorly designed systems, in contrast, the technologies do not fit easily into users’ working practices, and in the worst cases can make it more difficult to deliver safe treatment and care. The term ‘interoperable’ refers to the ability of any two or more IT systems to exchange data, and for the receiving system to make use of the data. The IT systems of interest in this protocol allow professionals to access patients’ records held in other organisations.

Policy makers’ assumptions

Many people who live in their own homes, and who are frail or have chronic health problems, need support from a range of professionals. These include general (or family) practitioners, community nurses, therapists, social workers, and planned and emergency hospital services. There is good evidence that treatment and care is often fragmented [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Linking IT systems across a health economy can, policy makers reason, help to improve the coordination of services. Professionals can, the thinking goes, use the IT networks to communicate with one another, and hence effectively coordinate a patient’s treatment and care. The value of this function might be particularly evident at transition points, for example in a health emergency or at the point of returning from hospital to home. The IT systems can also be designed to enable access to all parts of a patient’s record, so that professionals can search for and locate information wherever it is held. The Obama administration in the USA committed considerable sums to linking hospital, family physician, pharmacy and other IT systems. Similarly, and more recently, the National Health Service in England has emphasised the importance of linking hitherto fragmented IT systems across organisations in local health economies [ 11 , 12 ].

- Realist synthesis

This protocol describes a realist synthesis, which seeks to understand how and why inter-organisational IT systems reduce patients’ clinical risks, or fail to do so. The realist synthesis method involves opening up the ‘black box’ of events that lie between an intervention and its effects [ 13 , 14 ]. It does so by identifying programme theories: these are sequences of decisions and actions that capture the intended effects of an intervention, and the underlying logic that links them together. A number of initial theories are typically identified.

Literature searches are then designed. It is not usually feasible to identify evidence about all of the sequences in all of the theories. Searches therefore focus on two or three theories, or on key sequences within those theories. Empirical evidence is then identified, assessed and synthesised, in order to evaluate the actual steps in the sequences. The evidence can, in addition, lead teams to realise that a programme is effective, but not in the way originally envisaged. A programme theory therefore needs to be reformulated. More searches may then be needed, to evaluate elements of the revised theory. That is, the cycle of programme theory formulation and evaluation can be iterative and—resources permitting—pursued until a settled, evidence-based account has been identified [ 15 ].

There are literatures that will enable us to develop and evaluate programme theories [ 16 ]. For example, the computer-supported cooperative work literature sits at the intersection of computer science and psychology, and is a source of evidence about the inter-relationships of IT systems and peoples’ working practices. A comprehensive review suggests that we have a reasonable understanding of the design features and organisational settings that are associated with the effective integration of systems into clinical working practices [ 17 ]. Similarly, there are literatures on health professionals’ decisions and actions, and their consequences for patients’ clinical risks. In particular, there is a substantial literature based on retrospective analysis of adverse events, both in health care and other sectors [ 18 ].

This protocol has been written in accordance with PRISMA-P guidelines [ 19 ].

We will undertake a realist synthesis. The aim of the study is to establish how, why and in what circumstances networked, inter-organisational IT systems affect patient safety. The objectives of the study are to:

Identify initial programme theories and prioritise theories to review;

Search systematically for evidence to test and refine the theories;

Undertake quality appraisal and use included texts to support, refine or reject programme theories;

Synthesise the findings;

Disseminate the findings to a range of audiences.

The following sections focus on the first four objectives.

Stage 1: Identification of programme and mid-range theories

This stage is essentially developmental in nature. The first step in this review will be to construct one or more programme theories, concerning the use of networked IT systems and their effects on patient safety. Mid-range theories, which are usefully thought of as a broader class of theory than programme theories, and which will be used to generalise findings at the end of the review, will also be identified. We will supplement our existing knowledge of candidate theories with literature searches to define and develop them. The programme theories will determine the scope (inclusion and exclusion criteria) for the searches and synthesis in the following stages, which will be used to support, refine or reject each theory examined.

Search strategy and information resources

Theories can be explicitly mentioned in research articles and policy documents, or they can be implied in the introductory or discussion sections of documents. They can also be found in commentaries and opinion pieces. We will use conventional literature searching using free text words, synonyms and subject index terms, and some CLUSTER searching techniques (identifying a few key relevant studies and finding further relevant studies via forwards and backwards citation searches, author searches, searching for reports of a particular project) [ 20 ]. Using this combined approach, we aim to identify literature that leads us to theories or fragments of theories that can be used to construct programme and mid-range theories.

We anticipate that three searches will supplement the policy documents and academic literature already known to the project team. MEDLINE (1946–present) and EMBASE (1947–present) will be searched as a core set of databases for all of the theory generating searches.

Background search of systematic reviews . We will search for systematic reviews that link IT systems and patient safety. This will identify any reviews on this topic that have been published since our scoping review, undertaken before the start of the project. The reviews may describe programme theories or fragments in their introduction or discussion sections, providing insights into the sequences of events linking the intervention and outcomes. We will search the core databases plus the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Epistemonikos database and Health Systems Evidence (McMaster University). An example MEDLINE search strategy containing a full set of search terms is available in the Additional file 1 (Search 1).

Policies, opinion pieces and research reports . We will search the core databases plus Health Management Information Consortium (1983–present) and Web of Science - Science Citation Index (1990–present) for policy documents, opinion pieces (e.g. editorials) and reports describing leading theories about the relationships between IT systems and patient safety (Additional file 1 Search 2). We will also undertake Google searches to locate reports on key policies, e.g. about the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act 2009, a major US initiative promoting the implementation of cross-organisational IT networks.

Author search and Citation search . We will search for reports and articles authored by influential commentators in the core databases plus Health Management Information Consortium (1983–present), Web of Science - Science Citation Index (1990–present), Google Scholar and Scopus (1823–present). Literature by David Bates, the most cited author in the health informatics literature, and Robert Wachter, the author of an influential report on IT in the NHS in England, will be searched (Additional file 1 Search 3). Citation searching may be required due to the iterative nature of developing searches for a realist synthesis.

Inclusion, analysis and synthesis

The records identified in the searches will be saved and managed in an EndNote library. Details of all search activities (databases, websites, date of search, number of records found, search strategies) will be recorded in a timeline spreadsheet. The inclusion criteria for the three searches will be:

IT networks that link two or more organisations outside (but possibly including) hospitals;

IT networks that support direct treatment and care;

Arguments that identify relationships between IT networks and patient safety;

Published in the English language between 2000 and 2018.

Non-English language articles will not be included. The project does not have sufficient resources to translate the full text of articles that may be relevant. In conventional systematic reviews, it is not necessary to translate whole papers, as it is only necessary to identify defined data. In this review, however, we will be looking for data that might occur anywhere in a paper, and a full translation would be needed.

The exclusion criteria will be for studies that:

Describe hospital-only IT systems;

Describe systems that do not link two or more distinct services;

Focus on IT systems that support secondary uses of data, e.g for service planning, research;

are published before 2000;

are published in languages other than English.

Two reviewers (MA and JK) will first independently screen the titles and abstracts of the records for relevance and then assess full-text reports. Any discrepancies will be solved by discussion, and if needed consultation with a third author (JG or RR). Data extraction forms will be developed to capture basic details of studies—authors, publication year, etc.—and passages on theories and theory fragments.

The selected studies will be used to develop visual representations of programme theories, with accompanying text that explains the reasoning that underpins those theories. Experience gained in earlier reviews suggests that there are likely to be several programme theories at this point, and that some of them will be partial, in the sense that the chains of reasoning are ‘high level’ and not fully articulated, or only cover some of the steps linking networked information technologies and patient safety. Where available, claims about the reasons why programmes succeed or fail in practice will be used to annotate the representations.

The programme theories will be used as the basis for consultation with three groups of stakeholders—policy makers, senior IT managers and frontline clinicians. We will use the nominal group technique, which has been used in a previous realist study [ 21 ]. At the nominal group meetings participants will be asked to comment critically on the programme theories, on the basis of their knowledge and experience. They will also be asked to develop and then prioritise theories, or particular chains of reasoning within theories, for further study. The prioritisation will take into account the potential to provide learning for the NHS, and the types of networked systems that NHS organisations are implementing. The groups will be re-convened for consultation by email at the end of stage 4 (see below).

The outputs of the three groups will be further reviewed by a patient and public involvement (PPI) group, and discussed with our project steering group. Following these meetings, we will decide on the programme theories, and key elements of those theories, that we will explore in depth in stages 2–4.

Stage 2: Systematic search for evidence

The next stage of the review is a search for empirical studies to test and refine the leading programme theories identified in stage 1. The initial searches will be designed to identify evidence about the steps in the chains of reasoning in each theory. Literatures often focus on one or other section in a chain of reasoning, and as a result, individual searches will often focus on sections rather than a whole programme theory [ 22 ]. We will undertake searches using resources which span health and computing literatures including—but not limited to—MEDLINE (1946–present), EMBASE (1947–present), Web of Science Core Collection (1900–present) and INSPEC (1896–present).

We anticipate hand searching papers from leading conferences which are not indexed, for example Software Engineering in Healthcare workshops papers, from the International Conference on Software Engineering. The search strategies for identifying empirical evidence for programme theories can only be fully developed once the programme theories are agreed. However, we anticipate they will contain search concepts for an aspect of patient safety such as medication reconciliation, inter-organisational IT networks and evaluative studies.

The search results will be reviewed in stage 3 (evidence review, see below) and further searches will develop iteratively to follow lines of enquiry. Initial searches may not identify empirical evidence that supports or rejects a programme theory. If that happens, the search will be re-designed to capture empirical evidence that may be found in a different discipline or information resource. For example, we could extend the scope of our searches to look for evidence about other IT applications, including hospital-based systems, and/or extend the scope of the populations of interest. As in stage 1, these searches may use CLUSTER search techniques as an efficient method for finding relevant papers [ 20 ].

The results of the electronic searches and all references that are retrieved for stage 2 will be kept in the same EndNote library as those found during stage 1. Details of all search activities during stage 2 will be recorded in the timeline spreadsheet.

Stage 3: Evidence review and quality appraisal

Titles and abstracts of records identified, and the full-text papers selected in stage 2, will be independently screened by two reviewers (MA and JK) to identify those which contain evidence that sheds light on one or more elements of the programme theories identified in stage 1. The RAMESES I guidance states that:

An appraisal of the contribution of any section of data (within a document) should be made on two criteria: • Relevance – whether it can contribute to theory building and/or testing; and • Rigour – whether the method used to generate that particular piece of data is credible and trustworthy [ 14 ].

We will follow Rycroft-Malone and colleagues in developing criteria for judging relevance [ 23 ]. We will, further, use the mid-range theory developed in stage 1 to refine the criteria. Rigour refers to the requirement for an investigation to be of sufficient standard within type , whether that is a process evaluation, an ethnography or other type of study [ 14 ].

The empirical data for supporting and/or refuting programme theories will be extracted from the included studies. It is anticipated that a significant proportion of the evidence will be in the form of narrative data and will accordingly be copied into Word files. To maximise accuracy and transparency, a proportion of data extraction will be performed independently by two members of the research team.

Stage 4: Synthesis

Synthesis involves two distinct, but linked, activities. In the first, the empirical evidence identified in stages 2 and 3 will be used to evaluate the programme theories developed in stage 1. In the most straightforward case, the evidence will support the chains of reasoning in one programme theory and serve to reject alternative or competing theories. Less straightforwardly, the evidence might provide support for one part of a programme theory and adverse evidence for another part of the same theory. Or, it might not ‘fit’ a programme theory, neither supporting nor undermining it. Both instances suggest that there may be a problem with the programme theory itself and will lead us to refine it, to achieve a better fit between evidence and theory. On the basis of experience of earlier realist syntheses, we expect that at least one of the selected theories—or theory fragments—will be reasonably well supported by empirical evidence, and at least one will not be not supported.

Second, when a settled programme theory or theories have been produced, they will be interpreted in the broader context of the mid-range theory. This involves abduction, where inferences that lead to the best available explanation are identified. The details of the abductive reasoning processes vary from review to review, but a key point is that it involves inter-play between situation-specific programme theories and broader mid-range theory [ 24 ]. In the simplest case, the (now evidence-based) programme theories will be consistent with the mid-range theory. If we find that a programme theory holds across a number of settings (e.g. different combinations of health services and/or different patient groups), this will increase our confidence in it. Alternatively, evidence or argument (or both) may point in different directions, and the wider project team will use the mid-range theory to ‘adjudicate’ between contending programme theories.

Nominal group email consultation

The nominal groups will be re-convened for email consultation. We will summarise our findings to this point, including our provisional syntheses, and present them to the groups. They will be asked to comment on the findings, including whether any of the theories can be rejected, and whether any further searches are merited. The PPI group will also meet at the end of this stage and review the findings and interpretations of the three nominal groups. We will refine our interpretations on the basis of the comments of all four groups.

Policy makers in many countries believe that IT systems can contribute to safer patient care. Interoperable systems are currently being promoted by governments, and funding made available for their development, in many countries. As noted above, though, the empirical evidence about this belief is mixed, and it is not clear why this is the case. We are using the realist synthesis method because we believe that it will shed light on how and why interoperable systems contribute to reductions in patients’ clinical risks, and hence help to explain why the evidence is so mixed.

As with any evidence synthesis, there are risks and limitations associated with the method. The most obvious risk, in common with other review methods that focus on effectiveness, is that we are not able to identify high-quality effectiveness evidence. This will necessarily limit the extent to which we are able to explain ‘what works’ when interoperable systems are deployed. Another significant risk is the flip side of a potential strength. The explicit inclusion of theory in the method means that the basis for interpreting the available evidence is clear. But, there must be a risk that—however much care is taken—a sub-optimal theoretical framework will be used, and valuable insights foregone. If we are able to mitigate these risks in the course of the review, though, it should produce two main outcomes. First, the refined mid-range theory will contribute to our understanding of the underlying mechanisms that lead to changes in clinical practices and hence patients’ risks (or not). Second, many governments are funding and implementing cross-organisational IT networks. The findings can be used to inform policies on their design and implementation.

Availability of data and materials

This is a protocol for a systematic review. We will make all searches, and the results of those searches, available publicly when the review is completed. This will, again, require clearance by NIHR—but we do not anticipate any problems, given the nature of the study.

Agboola SO, Bates DW, Kvedar JC. Digital health and patient safety. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1697–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Brenner SK, et al. Effects of health information technology on patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(5):1016–36.

Article Google Scholar

Black AD, et al. The impact of eHealth on the quality and safety of health care: a systematic overview. PLoS Med. 2011;8(1):e1000387.

Kruse CS, Beane A. Health information technology continues to show positive effect on medical outcomes: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(2):e41.

Chaudhry B, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):742–52.

Feldman SS, Buchalter S, Hayes LW. Health information technology in healthcare quality and patient safety: literature review. JMIR Med Inform. 2018;6(2):e10264.

Garavand A, et al. Factors influencing the adoption of health information technologies: a systematic review. Electron Physician. 2016;8(8):2713–8.

O’Hara JK, Aase K, Waring J. Scaffolding our systems? Patients and families ‘reaching in’ as a source of healthcare resilience. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(1):3–6.

Care Quality Commission, Building bridges, breaking barriers. Newcastle upon Tyne: CQC, 2017.

Leigh Johnston DR, Dorrans S, Dussin L. A.T. Barker, Integration 2020: Scoping research. p. 2017.

Jacob JA. On the road to interoperability, public and private organizations work to connect health care data. JAMA. 2015;314(12):1213–5.

Bates DW. Health information technology and care coordination: the next big opportunity for informatics? Yearb Med Inform. 2015;10(1):11–4.

Pawson R. Evidence Based Policy: A Realist Perspective. London: Sage; 2006.

Book Google Scholar

Wong G, et al. Development of methodological guidance, publication standards and training materials for realist and meta-narrative reviews: the RAMESES (Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses – Evolving Standards) project. Health Serv Del Res. 2014;2:30.

Google Scholar

Pawson R. The Science of Evaluation: A Realist Manifesto. London: Sage; 2013.

Pollock N, Williams R. Software and organisations. The biography of the enterprise-wide system or how SAP conquered the world. London: Routledge; 2009.

Fitzpatrick G, Ellingsen G. A review of 25 years of CSCW research in healthcare: contributions, challenges and future agendas. Comput Supp Coop Work (CSCW). 2013;22(4-6):609–65.

Vincent, C. and R. Amalberti, Safety strategies in hospitals, in Safer Healthcare. SpringerOpen, 2016, p. 73-91.

Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1.

Booth A, et al. Towards a methodology for cluster searching to provide conceptual and contextual “richness” for systematic reviews of complex interventions: case study (CLUSTER). BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:118.

Tolson D, et al. Developing a managed clinical network in palliative care: a realistic evaluation. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(2):183–95.

Ball SL, Greenhalgh J, Roland M. Referral management centres as a means of reducing outpatients attendances: how do they work and what influences successful implementation and perceived effectiveness? BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:37.

Rycroft-Malone J, et al. Improving skills and care standards in the support workforce for older people: a realist review. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5):e005356.

Pawson R. Evidence and policy and naming and shaming. Policy Stud. 2002;23(3):211–30.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This project is funded by the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research programme, project 16/53/03. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

National Institute for Health Research, Health Services and Delivery Research programme, project 16/53/03.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Leeds Institute of Health Sciences, University of Leeds, Worsley Building, Clarendon Way, Leeds, LS2 9NL, England

Justin Keen, Roberta Longo, Jon Fistein, Maysam Abdulwahid, Natalie King & Judy Wright

School of Sociology and Social Policy, University of Leeds, Leeds, England

Joanne Greenhalgh

School of Healthcare, University of Leeds, Leeds, England

Rebecca Randell

School of Psychology, University of Leeds, Leeds, England

Peter Gardner

Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, England

Justin Waring

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to writing the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Justin Keen .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics letter provided.

Consent for publication

The National Institute for Health Research operates a ‘negative consent’ model, whereby papers are submitted and if—after 30 days—no objections are raised, consent is deemed to have been given. This draft paper has been submitted to NIHR.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1..

Search strategies to identify reports for generating theory.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Keen, J., Greenhalgh, J., Randell, R. et al. Networked information technologies and patient safety: a protocol for a realist synthesis. Syst Rev 8 , 307 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1223-1

Download citation

Received : 13 February 2019

Accepted : 06 November 2019

Published : 05 December 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1223-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Patient safety

- Information technology

- Systems integration

- Health information exchange

- Health services research

- Systematic review

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Help & FAQ

Patient safety risks associated with telecare: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of the literature

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › Research › peer-review

Background: Patient safety risk in the homecare context and patient safety risk related to telecare are both emerging research areas. Patient safety issues associated with the use of telecare in homecare services are therefore not clearly understood. It is unclear what the patient safety risks are, how patient safety issues have been investigated, and what research is still needed to provide a comprehensive picture of risks, challenges and potential harm to patients due to the implementation and use of telecare services in the home. Furthermore, it is unclear how training for telecare users has addressed patient safety issues. A systematic review of the literature was conducted to identify patient safety risks associated with telecare use in homecare services and to investigate whether and how these patient safety risks have been addressed in telecare training. Methods: Six electronic databases were searched in addition to hand searches of key items, reference tracking and citation tracking. Strict inclusion and exclusion criteria were set. All included items were assessed according to set quality criteria and subjected to a narrative synthesis to organise and synthesize the findings. A human factors systems framework of patient safety was used to frame and analyse the results. Results: 22 items were included in the review. 11 types of patient safety risks associated with telecare use in homecare services emerged. These are in the main related to the nature of homecare tasks and practices, and person-centred characteristics and capabilities, and to a lesser extent, problems with the technology and devices, organisational issues, and environmental factors. Training initiatives related to safe telecare use are not described in the literature. Conclusions: There is a need to better identify and describe patient safety risks related to telecare services to improve understandings of how to avoid and minimize potential harm to patients. This process can be aided by reframing known telecare implementation challenges and user experiences of telecare with the help of a human factors systems approach to patient safety.

- Human factors

- Narrative synthesis

- Patient safety

- Systematic review

This output contributes to the following UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Access to Document

- 10.1186/s12913-014-0588-z Licence: CC BY

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

T1 - Patient safety risks associated with telecare

T2 - A systematic review and narrative synthesis of the literature

AU - Guise, Veslemøy

AU - Anderson, Janet

AU - Wiig, Siri

N1 - Funding Information: We would like to thank Grete Mortensen, special librarian at the University of Stavanger, for valuable assistance during the literature search process. We would also like to acknowledge The Research Council of Norway for funding the Safer@Home research project of which this study is a part (grant number 210799) and thank our partners in the project. Publisher Copyright: © 2014 Guise et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd.

PY - 2014/11

Y1 - 2014/11

N2 - Background: Patient safety risk in the homecare context and patient safety risk related to telecare are both emerging research areas. Patient safety issues associated with the use of telecare in homecare services are therefore not clearly understood. It is unclear what the patient safety risks are, how patient safety issues have been investigated, and what research is still needed to provide a comprehensive picture of risks, challenges and potential harm to patients due to the implementation and use of telecare services in the home. Furthermore, it is unclear how training for telecare users has addressed patient safety issues. A systematic review of the literature was conducted to identify patient safety risks associated with telecare use in homecare services and to investigate whether and how these patient safety risks have been addressed in telecare training. Methods: Six electronic databases were searched in addition to hand searches of key items, reference tracking and citation tracking. Strict inclusion and exclusion criteria were set. All included items were assessed according to set quality criteria and subjected to a narrative synthesis to organise and synthesize the findings. A human factors systems framework of patient safety was used to frame and analyse the results. Results: 22 items were included in the review. 11 types of patient safety risks associated with telecare use in homecare services emerged. These are in the main related to the nature of homecare tasks and practices, and person-centred characteristics and capabilities, and to a lesser extent, problems with the technology and devices, organisational issues, and environmental factors. Training initiatives related to safe telecare use are not described in the literature. Conclusions: There is a need to better identify and describe patient safety risks related to telecare services to improve understandings of how to avoid and minimize potential harm to patients. This process can be aided by reframing known telecare implementation challenges and user experiences of telecare with the help of a human factors systems approach to patient safety.

AB - Background: Patient safety risk in the homecare context and patient safety risk related to telecare are both emerging research areas. Patient safety issues associated with the use of telecare in homecare services are therefore not clearly understood. It is unclear what the patient safety risks are, how patient safety issues have been investigated, and what research is still needed to provide a comprehensive picture of risks, challenges and potential harm to patients due to the implementation and use of telecare services in the home. Furthermore, it is unclear how training for telecare users has addressed patient safety issues. A systematic review of the literature was conducted to identify patient safety risks associated with telecare use in homecare services and to investigate whether and how these patient safety risks have been addressed in telecare training. Methods: Six electronic databases were searched in addition to hand searches of key items, reference tracking and citation tracking. Strict inclusion and exclusion criteria were set. All included items were assessed according to set quality criteria and subjected to a narrative synthesis to organise and synthesize the findings. A human factors systems framework of patient safety was used to frame and analyse the results. Results: 22 items were included in the review. 11 types of patient safety risks associated with telecare use in homecare services emerged. These are in the main related to the nature of homecare tasks and practices, and person-centred characteristics and capabilities, and to a lesser extent, problems with the technology and devices, organisational issues, and environmental factors. Training initiatives related to safe telecare use are not described in the literature. Conclusions: There is a need to better identify and describe patient safety risks related to telecare services to improve understandings of how to avoid and minimize potential harm to patients. This process can be aided by reframing known telecare implementation challenges and user experiences of telecare with the help of a human factors systems approach to patient safety.

KW - Homecare

KW - Human factors

KW - Narrative synthesis

KW - Patient safety

KW - Systematic review

KW - Telecare

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=84988602909&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1186/s12913-014-0588-z

DO - 10.1186/s12913-014-0588-z

M3 - Article

C2 - 25421823

AN - SCOPUS:84988602909

SN - 1472-6963

JO - BMC Health Services Research

JF - BMC Health Services Research

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 12 March 2019

A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis on the risks of medical discharge letters for patients’ safety

- Christine Maria Schwarz 1 ,

- Magdalena Hoffmann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1668-4294 1 , 2 ,

- Petra Schwarz 3 ,

- Lars-Peter Kamolz 1 ,

- Gernot Brunner 1 &

- Gerald Sendlhofer 1 , 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 19 , Article number: 158 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

27k Accesses

45 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

The medical discharge letter is an important communication tool between hospitals and other healthcare providers. Despite its high status, it often does not meet the desired requirements in everyday clinical practice. Occurring risks create barriers for patients and doctors. This present review summarizes risks of the medical discharge letter.

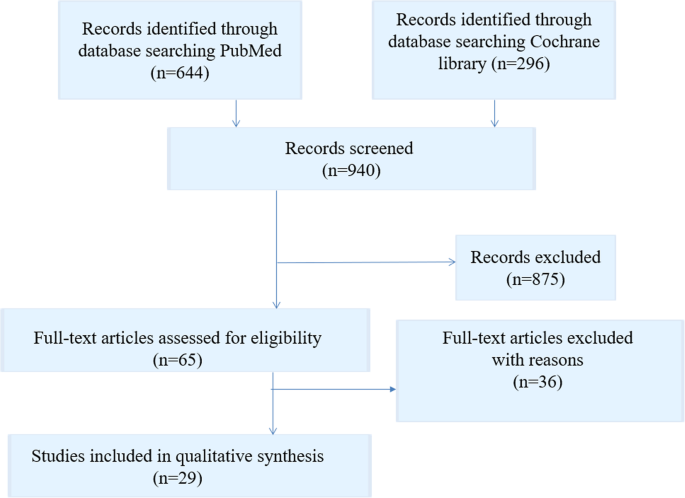

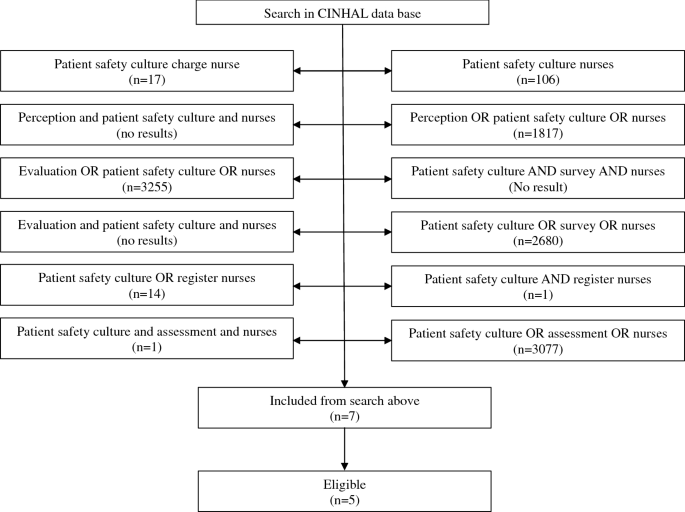

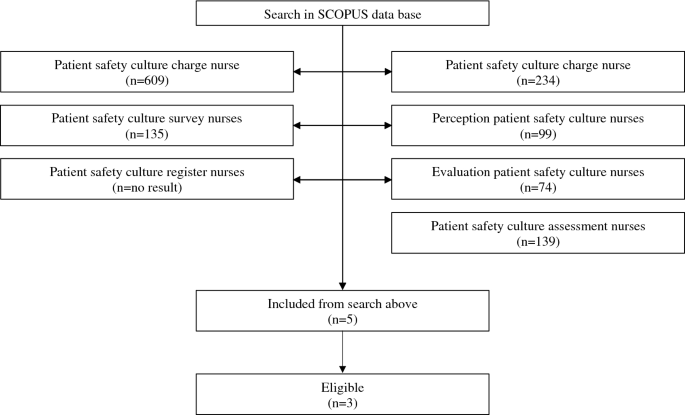

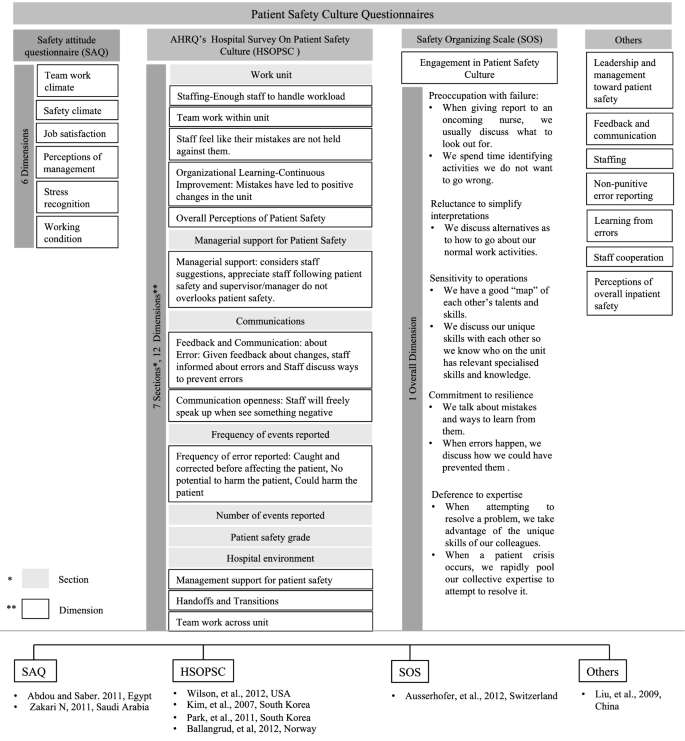

The research question was answered with a systematic literature research and results were summarized narratively. A literature search in the databases PubMed and Cochrane Library for Studies between January 2008 and May 2018 was performed. Two authors reviewed the full texts of potentially relevant studies to determine eligibility for inclusion. Literature on possible risks associated with the medical discharge letter was discussed.

In total, 29 studies were included in this review. The major identified risk factors are the delayed sending of the discharge letter to doctors for further treatments, unintelligible (not patient-centered) medical discharge letters, low quality of the discharge letter, and lack of information as well as absence of training in writing medical discharge letters during medical education.

Conclusions

Multiple risks factors are associated with the medical discharge letter. There is a need for further research to improve the quality of the medical discharge letter to minimize risks and increase patients’ safety.

Peer Review reports

The medical discharge letter is an important communication medium between hospitals and general practitioners (GPs) and an important legal document for any queries from insurance carriers, health insurance companies, and lawyers [ 1 ]. Furthermore, the medical discharge letter is an important document for the patient itself.

A timely transmission of the letter, a clear documentation of findings, an adequate assessment of the disease as well as understandable recommendations for follow-up care are essential aspects of the medical discharge letter [ 2 ]. Despite this importance, medical discharge letters are often insufficient in content and form [ 3 ]. It is also remarkable that writing of medical discharge letters is often not a particular subject in the medical education [ 4 ]. Nevertheless, the medical discharge letter is an important medical document as it contains a summary of the patient’s hospital admission, diagnosis and therapy, information on the patient’s medical history, medication, as well as recommendations for continuity of treatment. A rapid transmission of essential findings and recommendations for further treatment is of great interest to the patient (as well as relatives and other persons that are involved in the patients’ caring) and their current and future physicians. In most acute care hospitals, patients receive a preliminary medical discharge letter (short discharge letter) with diagnoses and treatment recommendations on the day of discharge [ 5 ]. Unfortunately, though, the full hospital medical discharge letter, which is often received with great delay, is an area of constant conflict between GPs and hospital doctors [ 1 ]. Thus the medical discharge letter does not only represent a feature of process and outcome quality of a clinic, but also influences confidence building and binding of resident physicians to the hospital [ 6 ].

Beside the transmission of patients’ findings from physician to physician, the delivery of essential information to the patient is an underestimated purpose of the medical discharge letter [ 7 ]. The medical discharge letter is often characterized by a complex medical language that is often not understood by the patients. In recent years, patient-centered/patient-directed medical discharge letters are more in discussion [ 8 ]. Thus, the medical discharge letter points out risks for patients and physicians while simultaneously creating barriers between them.

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken to identify patient safety risks associated with the medical discharge letter.

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted using the electronic databases PubMed and Cochrane Database. Additionally, we scanned the reference lists of selected articles (snowballing). The following search terms were used: “discharge summary AND risks”, “discharge summary AND risks AND patient safety” and “discharge letter AND risks” and “discharge letter AND risks AND patient safety”. We reviewed relevant titles and abstracts on English and German literature published between January 2008 and May 2018 and started the search at the beginning of February 2018 and finished it at the end of May 2018.

Eligibility criteria