Resources in Chinese

Translate this page from English...

*Machine translated pages not guaranteed for accuracy. Click Here for our professional translations.

Learning to Think Things Through

By Gerald Nosich View Book Sample including Table of Contents, overviews and selected pages.

The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking: Concepts and Tools, Chinese

Translation of this Guide was generously provided by the Wenzao Ursuline College of Languages. The file below is a Microsoft Word Document with Chinese character formatting. You must have a Chinese language pack or operating system to view the characters in the document.

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, how do chinese undergraduates understand critical thinking a phenomenographic approach.

- 1 Faculty of Education, Southwest University, Chongqing, China

- 2 Centre for Higher Education Studies, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, China

The cultivation of critical thinking in undergraduates is crucial for teaching in higher education. Although scholars have defined critical thinking in various ways, limited study about critical thinking from the learner’s perspective. In this phenomenographic research, we collect essays written by 80 Chinese undergraduates with multiple disciplinary backgrounds to reveal their understandings of critical thinking. Four conceptions of critical thinking were found, namely critical thinking as query and reflection on the irrationality of things (Conception 1); an objective and comprehensive understanding of things (Conception 2); independent thinking with innovation (Conception 3), as well as a willingness and attitude (Conception 4). Further analysis in the light of the referential-structural framework helps to construct a hierarchical relationship between different conceptions, with Conception 1 the least complex and Conception 3 the most complex. While Conceptions 1–3 are skill-oriented, Conception 4 is deposition-oriented, and there is no hierarchical relationship between the two groups of conceptions. They deal with different dimensions of critical thinking. University lecturers can use these findings to help equip undergraduates with deepened conceptions of critical thinking in their daily routine teaching.

Introduction

Critical thinking has almost become “one of the defining concepts of the Western University” ( Barnett, 1997 , p. 3). In the United States, school education has always emphasized the cultivation of citizens who are able to adapt themselves to modern society’s development and to independently judge and process information since Dewey advocated “reflective thinking” in the early twentieth century ( Zhong, 2002 ). The critical-thinking movement was popular in western countries in the 1960s, and regarded as a major goal of higher education ( Yuan, 2012 ), and it has now generally been accepted as a significant competence and an important objective for higher education ( Bali, 2015 ). In fact, studies have indicated that critical thinking has a significant impact on Students’ academic performance and achievements in higher education ( Fong et al., 2017 ; Ghanizadeh, 2017 ; Ren et al., 2020 ).

Over the past decades, several scholarly issues related to critical thinking have become prominent ( Cáceres et al., 2020 ). Teaching for critical thinking, or pedagogical strategies for promoting critical thinking is a key research theme throughout the years at all education levels (e.g., Cáceres et al., 2020 ; Aktoprak and Hursen, 2022 ) and for diverse disciplines (e.g., McLaughlin and McGill, 2017 ; Bellaera et al., 2021 ), since critical thinking has been viewed as skills and dispositions that can be learned instead of an innate and unmodifiable mental function ( Liyanage et al., 2021 ). Researchers also endeavor to measure critical thinking skills, which heavily relies on standardized multiple-choice tests ( Larsson, 2017 ). Numerous measurement tools have been made, such as the Cornell Critical Thinking Test (CCTT), the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST), the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal-FS (WGCTA-FS) ( Behar-Horenstein and Niu, 2011 ) and the HEIghten <reg>(</reg> critical thinking assessment ( Liu et al., 2018 ; Shaw et al., 2020 ). Noticeably, as Larsson (2017) contends, there is an ongoing extensive debate on the definition of critical thinking.

Scholars define critical thinking in diverse ways ( Arisoy and Aybek, 2021 ), one of which is “reasonable reflective thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do” as proposed by Ennis (1991 , p. 6). Paul and Elder (1999) argue that critical thinking is a process of interpreting, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating the information which dominates beliefs and behaviors in a positive and skillful manner and which is collected from observation, experiments, reflection, reasoning, and communications. Bailin et al. (1999) believe that critical thinking is a process of problem-solving in nature, stressing the key role of real problem situations in critical thinking training. Facione (1990) found that critical thinking is characterized by purposeful and self-disciplined judgment in obtaining the interpretation, analysis, evaluation, deduction, and explanation for the evidential, conceptual, methodological, standard, and situational thinking. Chinese scholars have also expressed their understanding. Yuan (2012) suggests that critical thinking is a review and query of, and reflection on existing knowledge, thoughts, and theories, and the problems therein. It includes critical spirit and skills. Yu et al. (2015) believe that critical thinking is exhibited by an inclination to make value judgments on the relevant information according to certain criteria and constantly improve problem-solving skills.

Based on these studies, critical thinking is a combination of the skill and disposition aspects ( Liu et al., 2021 ). The former refers to the elements selected as essential advanced cognitive skills and which are taught to students. As proposed by Schmaltz et al. (2017 , p. 1) “the term critical thinking has come to refer to an ever-widening range of skills and abilities.” The latter (disposition aspect) refers to “the extent to which an individual is inclined or willing to perform a given thinking skill” ( Dwyer and Walsh, 2019 , p. 18). While critical thinking has been defined in multiple ways, Ennis (2018 , p. 166) contends that these definitions do not differ significantly from each other, as each seems to be “a different way of cutting the same conceptual pie.” Although scholars hold different views on elements of skills, the commonalities can be summarized as clarifying the meaning, analyzing and demonstrating, evaluating evidence, judging and inducing rationality, and making reliable conclusions. In addition, the common points in mentality and attitudes also involve open-mindedness, fair mentality, evidence seeking, comprehensive and full understanding as much as possible, concern for others’ opinions and reasons, matching between beliefs and evidence, and willingness to accept alternative selection and belief revision ( Dai et al., 2012 ).

Researchers express distinct definitions of critical thinking and the divergence mainly lies in their emphases. However, there must be some common factors as they show different understanding modes for a common concept. For instance, researchers recognize critical thinking as a kind of thinking, focus on reflection, review, and re-examination, and attach great importance to the evidence. They also stress the explicit judgment as well as the consideration of both critical thinking capability and attitude inclination.

Researchers tend to define critical thinking based on personal experience and reflection, but this may not be enough for pertinent educational implications. In relation to higher education, better insights into how undergraduates understand critical thinking are important if we are to improve their critical thinking. Therefore, a change from the researcher’s perspective to that of the students is necessary. Only if educators fully understand Students’ conceptions of critical thinking can they suit the remedy to the case and complete the cultivation work with a definite purpose. The overarching question for this study is: what are the conceptions of critical thinking held by Chinese undergraduates? A phenomenographic approach was employed. The next section will outline this methodology, followed by data collection, analysis, and the presentation of the findings. Then the elements within each conception will be discussed, before we propose some practical implications.

Research design

Phenoemnography.

The focus of this research is conceptions, that is, people’s understanding and specific views of certain things. We use phenomenography, defined as an empirical research method aiming to study the qualitatively different ways in which people perceive, understand, and experience various phenomena or aspects of the surrounding world ( Marton, 1981 ). In phenomenographic studies, a number of terms like “conceptions,” “understandings,” and “views” are used to refer to the same thing, the same object of study. Researchers group similar ways of experiencing (conceptions) together into categories to highlight “qualitatively different” ways of experiencing. The focus is on “stripped” rather than rich descriptions of conceptions, because phenomenographers highlight the key aspects of experience/conceptions.

Phenomenography takes a “from-the-inside” perspective, with a focus on uncovering others’ understanding and perceptions of some phenomena (second-order perspective), rather than the researcher’s understanding and perspectives (first-order perspective). This is in line with phenomenography’s non-dualistic philosophical foundation. The focus is on the relationship between the subject (the experiencer) and the object (the phenomenon experienced). From a phenomenographic perspective, meaning is seen as constructed in the relationship between the experiencer and the experienced.

Qualitative research methods (such as interviews, reflective writing, and observation) are used to collect data. The objective lies in uncovering the different ways of experiencing a phenomenon as variously as possible and the selection of the participants should adhere to this principle. Maximum variation, the interest of which lies in heterogeneity or diversity ( Green, 2005 ), is an appropriate sampling method. Åkerlind et al. (2005, p. 79) contend that “[i]n phenomenography, small sample sizes with maximum variation sampling, that is, the selection of a research sample with a wide range of variation across key indicators (such as age, gender, experience, discipline areas, and so on), is traditional.”

Phenomenographic analysis involves a search for both commonalities and variations in the data and categories. Searching for qualitatively different categories, phenomenographers maximize the similarities between data within a category, and also maximize the differences between data representing different categories.

Data collection

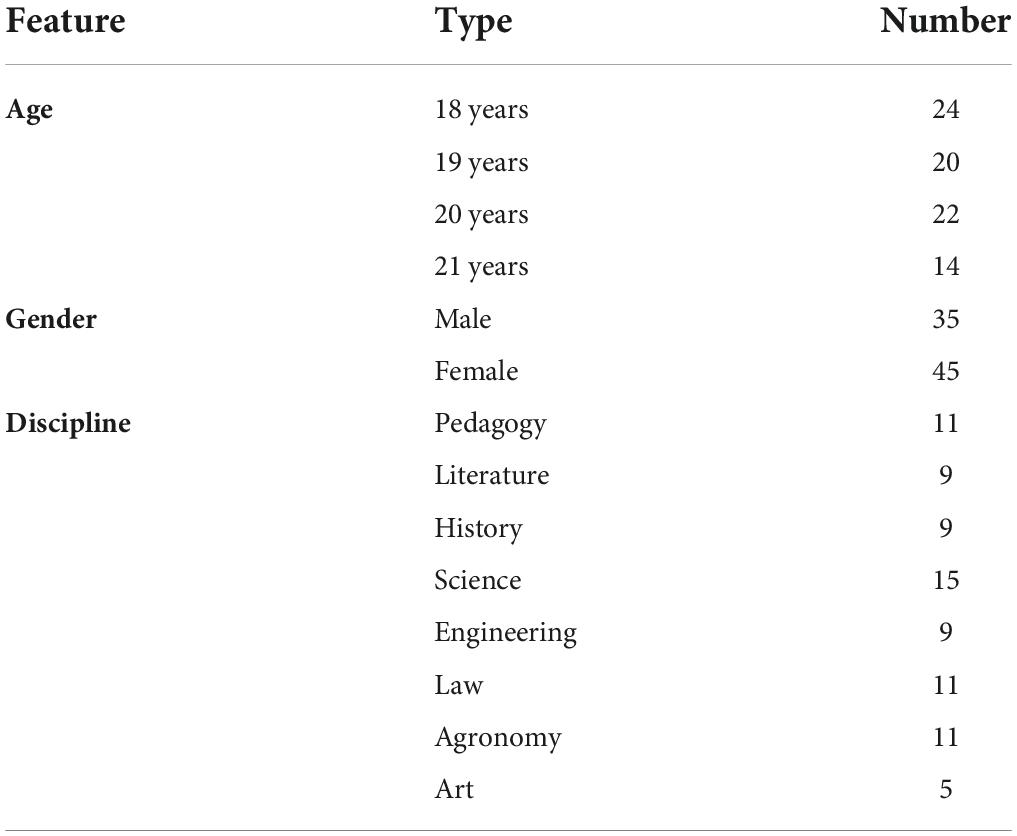

Qualitative data were collected through the Students’ written essays. The first author was teaching a course named Basics of Education which undergraduates from different disciplines attended. An essay writing task was given to all the 80 undergraduates in the middle of the semester as the midterm assignment. The students were asked to give their understanding and the perceived importance of critical thinking in Chinese. They knew that the essays would be used as data for the study. Once the essays were collected, we asked a professional translator to translate Chinese into English for analysis. One reason for choosing this way to collect data was to minimize the amount of researcher intervention, compared to, for example, an interview approach. Another reason was that this method allows the students sufficient time to organize their thoughts and ideas, fostering the expression of their viewpoints in a clear and thoughtful way. The third reason for choosing this way to collect data was the large number of students which allowed the inclusion of student participants from diverse disciplines (such as pedagogy, literature, history, science, engineering, law, agronomy, and art) and of different genders and ages, which ensured the maximum variation required by phenomenography. The background information of the respondents has been listed below ( Table 1 ):

Table 1. The background information of the respondents.

Although the requirements of critical thinking may vary according to different disciplines ( Grussendorf and Rogol, 2018 ), it is not the aim of the present research to explicate the relation between academic discipline and critical thinking. The goal of this study is to attain a general picture of critical thinking conceptions across different disciplines. Moreover, given the qualitative nature of this investigation, it is inappropriate to claim that certain students can represent a discipline as a whole.

Data analysis

We read the essays repeatedly to ensure sufficient familiarity with the essay data after the essays were collected. Subsequently, the expressions related to the research question were extracted to form a “pool of meanings,” and the analytical focus was transferred to this pool. Using the “pool of meaning” approach, we could better focus on the collective-level analysis. The collective interpretation aims to uncover people’s understandings across the group under investigation ( Åkerlind et al., 2005 ), rather than focusing on any individual’s understanding. As Åkerlind et al. (2005, p. 76) contend, the analysis should be “based on the interviews as a holistic group, not as a series of individual interviews.” The approach may also help to highlight the key characteristics of the meanings ( Åkerlind, 2005 ). From a practical perspective, extracting the meaning-laden statements from the whole transcripts into a pool of meanings make the data manageable ( Svensson and Theman, 1983 ).

Similarities and differences were found by carefully comparing, contrasting and distinguishing the extracted expressions, and then categorization and naming (labeling of the categories) was carried out to form a preliminary list of categories. The list was then continuously corrected, inspected, polished and confirmed, and each category checked for supporting empirical data. It was an iterative process to guarantee that the materials (expressions related to the research question) were rationally allocated to the categories and the borders between the categories were becoming increasingly clear to generate the categories. Each category was interconnected rather than separated. We finally concentrated on the establishment of the hierarchical relationship between different categories and ended up with the outcome space.

Research findings

The results showed that the participant undergraduates expressed four categories of conception of critical thinking. The corresponding explanations were as follows.

Critical thinking is query and reflection on the irrationality of things

This conception highlighted criticism as its core, where questioning, negating, reflecting on, and analyzing things and information served as a key part of critical thinking. The students argued that “critical thinking is nothing more than reflection and criticism in essence” (S66). Similar statements included: “Critical thinking is to view problems through critical thinking and figure out the inappropriate points in the problems” (S19); “Critical thinking is mainly represented by suspicion, which means finding fault with anything” (S27); and, “Critical thinking is criticizing and correcting others” (S41). One reason for holding this conception was the maladies of the virtual world in the information age. As S46 wrote:

We are in an era of information explosion. The arrival of the Internet gives information wings, and information sources vary from the traditional media to the We-Media in large quantity. Everyone can be an information publisher. For these reasons, we need to make efforts to screen the true or false information on the network.

The other reason was the social context as observed by S49:

Confronted with various information everywhere in society, we should have critical thinking and a questionable attitude. We ought to explicitly know whether the information is useful or useless, and good or bad.

In addition to questioning and reflecting on the people, things, and objects, critical thinking also involves the re-examination, negation, and correction of judgments, deductions, analysis, and explanations of individuals themselves, which is equivalent to “self-correction,” consciously monitoring one’s own cognitive activities. Taking what S52 said as an example, “Critical thinking refers to correcting one’s own original immature or false ideas while absorbing knowledge.” When it comes to the attitudes of querying and reflection, students thought individuals should remain rational and reduce subjective sensibility: “They can question the existing views but cannot blindly object or quarrel. Critical thinking is reasonable speculation and discussion instead of groundless non-senses” (S55).

This category focuses on a uni-directional search for what is incorrect, misleading, irrational, inappropriate, and/or not useful. This may be compared with the search for and balancing of multiple perspectives that is seen in next category.

Critical thinking is an objective and comprehensive understanding of things

Compared with the previous conception, this category of critical thinking seemed to be more comprehensive as the rationality and irrationality of things could be considered with negative aspects criticized and positive aspects affirmed. The undergraduates were able to objectively and comprehensively see things from multiple perspectives.

First, the ability to distinguish between two sides of the same thing was needed when judging and evaluating certain things. Students holding such a conception were aware of analyzing the internal contradictoriness of things and were able to actively think about both sides of the various things and phenomena they encountered. S9 felt that he “generally considers a thing from two sides, namely advantages and disadvantages.” S21 also believed that “Critical thinking means taking the good and bad aspects of a thing into account, namely strengths and weaknesses.” S25 said that:

Critical thinking is to view the problem in a critical manner, through which both sides should be discovered in things and problems. For example, both benefits and harms of Internet development in our life should not be ignored in the age of rapid Internet development.

S50 realized that critical thinking “helps me distinguish true or false better and screen the right information beneficial to me from a great deal of information obtained every day.” The reason why we are supposed to consider both sides of things was because in real life, “we are perhaps immersed in a sea of information, confused by specious solutions, and misguided by others’ ill-intentioned lies” (S33).

Second, observation and thinking should be performed from multiple perspectives to gain a more comprehensive and abundant understanding of things beyond a dichotomous analysis of only the positive and negative aspects. The perspective for observing and interpreting the external world is not limited to positive and negative sides. As S12 mentioned, “We should consider problems from another perspective beyond the positive and negative impacts considered, which usually brings about different feelings and understandings.” S69 also pointed out the importance of diverse perspectives and argued that “critical thinking refers to regarding problems and events from different points of view. We are considered to have critical thinking when we interpret things or problems on the basis of different angles.”

Compared with the dualist approach, employing diverse perspectives to deal with problems can be more conducive to students’ analyzing the full view of things and phenomena and acquiring a more comprehensive cognition. As S50 put forward, “Efforts should be made to analyze an object from multiple perspectives to achieve the effect of overall understanding.” S18 “independently takes objective things into consideration from various aspects, perspectives, and levels” in daily life. In the process of thinking from diverse perspectives, individuals should be able to decrease the interference of personal experience and prejudice, and take an objective, rational, and neutral position as far as possible. As S26 stated, “objective knowledge should not be looked at through rose-colored spectacles and excessive personal preference.”

Critical thinking is independent thinking with innovation

This conception attaches special importance to independence, that is, critical thinking is not seen as constituting a relationship of subordination or dependence with any person, theory or point of view. It neither relies on other things to exist nor depends on others for independence. In describing the necessity of independent thinking, many students took into account the prominent features of the information age. They believed that it was of great significance to be able to engage in rational and independent thinking in the current information environment. S43 believed:

If a person is capable of thinking independently, he/she will not be confused by wrong information from the outside world. One can obtain the information needed from a large amount of information and develop his/her own thinking.

The basis of thinking was the knowledge that individuals searched for and utilized in their argument, because “the foundation of critical thinking is knowledge, and the more knowledge and experience one accumulates in a field, the easier it is for one to have his/her own ideas subjectively, and he/she won’t blindly repeat what others say” (S44).

Independent thinking does not necessarily mean being different from others, but emphasizes the whole process of making a careful analysis of things and arriving at one’s own opinion without outside interference as much as possible. The final result may not be “astonishing,” yet it is a subjective and well-founded opinion and judgment. For instance, S50 said:

I think critical thinking is not about standing on the opposite of the public to be different, but about having one’s own independent thinking. As an independent person, one has a new point of view or way of thinking to support the events that he/she describes. It’s neither fault-finding nor dismissal, disbelief, or skepticism. Instead, it is a process of reflection, rationality, logic, comparison, discrimination, and evaluation that goes deep into the essence of things with a full understanding of the situation.

According to S80, critical thinking was:

[…] having one’s own unique ideas and cognition, opinions, and insights based on facts. Even if one doesn’t agree with many people, he/she doesn’t easily deny himself/herself because of hearsay. Instead, one carefully analyzes the events and comes up with your own opinion.

Independent thinking usually leads to independent personal views, opinions, judgments, and even innovation. Therefore, some students closely linked their understanding of critical thinking to innovation, seeing the former as an important source and logical basis for the latter. For instance, S26 stated, “I think that critical thinking is a kind of innovative thinking, which refers to the abandonment and innovation based on the generalization of previous or old thinking.” S10 also remarked that “critical thinking can stimulate our imagination and creativity, and spark our thinking.” S25 argued that “innovation is the soul of a nation, while critical thinking is the foundation of innovation, in which logic plays a vital role.” S68 claimed that “without criticism, there is no innovation. Without critical thinking, the source of innovation will be nowhere to be found, and the technological development of the society will be limited.” S80, from a wider perspective, believed that the cultivation of critical thinking is of great significance for the cultivation of innovative talents.

Critical thinking cannot be separated from the innovation capability, and lack of critical thinking directly gives rise to weak innovation capability; only by achieving the goal of cultivating critical thinking in education can we truly cultivate a large number of innovative talents.

Critical thinking is a willingness and attitude

In the final category, the Students’ emphasized their willingness and attitude to thinking critically. Without willingness and attitude, they thought it was unlikely that people would be able to think critically, thus failing to exercise and develop their critical thinking skills. This willingness and attitude were regarded as a prerequisite for critical skills and abilities in this sense. Meanwhile, the willingness and attitude also served as pillars in the process of skill development. With them, the students are perceived as more likely to develop critical thinking habits that will motivate them to think positively, question, express their opinions, and explain themselves, so as to allow themselves to exert autonomy and take initiatives in their studies and lives. In short, willingness and attitude are perceived as prerequisites for skill cultivation, always reflected in the demonstration of skills and provide support for the development of skills. Willingness and attitude are more implicit than skills, yet they are indispensable.

In this category, students’ willingness was first reflected in the fact that they had no blind faith in authority. For example, many mentioned the need to have a questioning willingness and attitude, “not to follow authority, to dare to question authority” (S18), and “to have a critical perspective, to dare to question, and to dare to seek evidence” (S58). Second, it was also reflected in independence, which was already evident in the analysis of the previous conception. Third, students were willing to think and remain curious. As S53 stated:

Critical thinking, I think, means … to ask questions and think about the phenomena that occur in life. Maintaining curiosity is a motivation for learning … though some may say Chinese education kills curiosity. We can gain a lot by finding problems and learning to solve problems.

Relationships between the conceptions

In addition to the qualitatively different ways of understanding, phenomenography also seeks to explore the potential structural relationship between various conceptions. This enables the conceptions to be ordered hierarchically, in terms of increasing complexity of understanding.

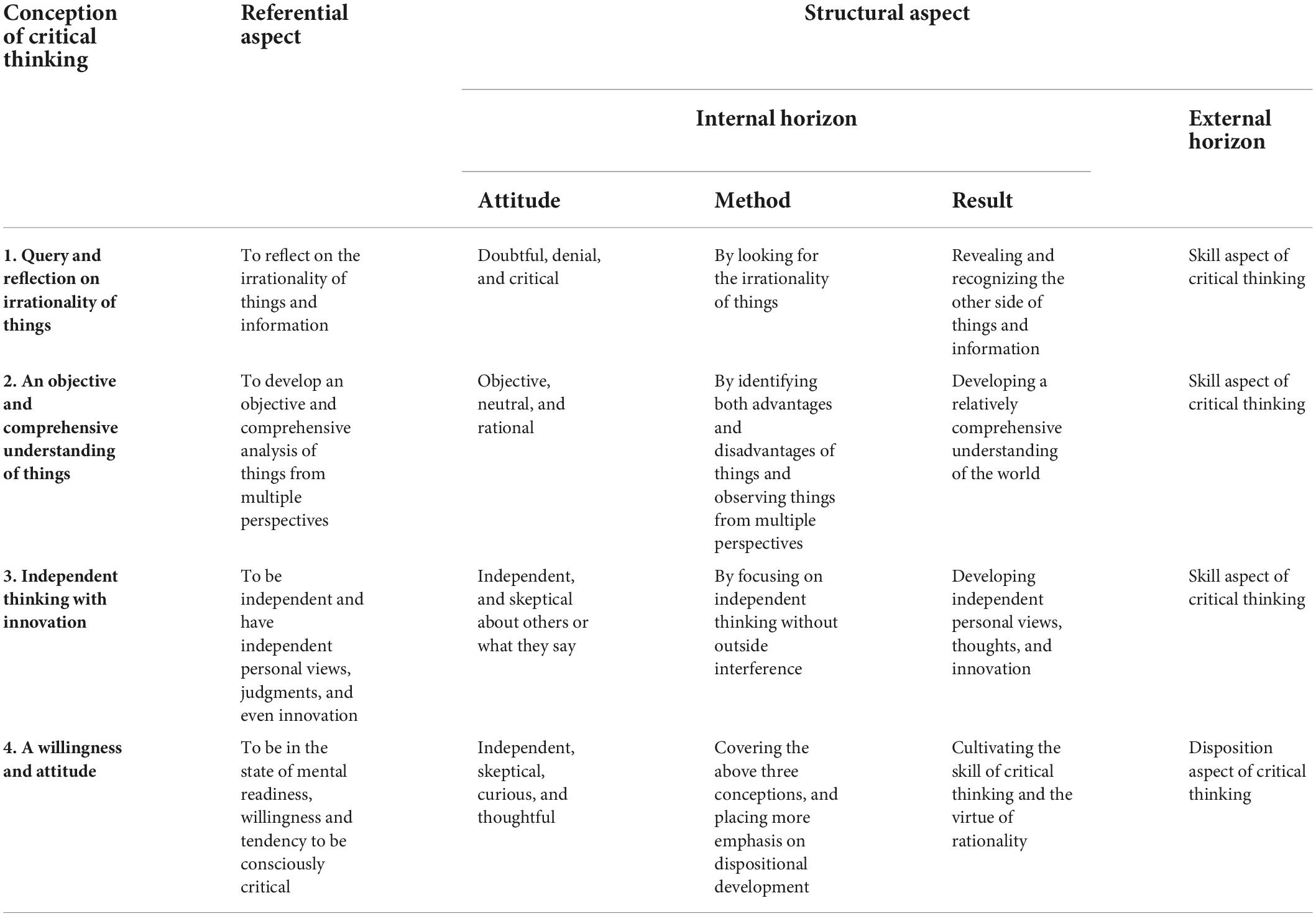

As for phenomenography’s analysis of different conceptions, there is a specific theoretical framework provided by phenomenography for analysis of relationships between conceptions. Within this framework, each conception is composed of a referential aspect and a structural aspect. The former refers to the global meaning of the phenomenon, while the latter consists of the internal horizon (the elements simultaneously present in consciousness and the relationship between them) and the external horizon (the environment in which the conception is present). With the help of this framework, the four abovementioned conceptions of critical thinking, as well as their internal components, can be analyzed one by one, and the relationship between them can be constructed ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. Critical thinking in the “referential-structural” analytical framework.

The different components of these four conceptions of critical thinking are analyzed and compared in Table 2 . It can be seen that Conceptions 1–3 generally demonstrate a trend from simple to complex, from one-sided to comprehensive. For example, from the perspectives of Method and Result, only looking for the irrational information is focused on in Conception 1, developing a relatively comprehensive understanding is targeted in Conception 2, and developing personal views with innovation on the basis of careful analysis is encouraged in Conception 3, placing more emphasis on dispositional development is highlighted in Conception 4.

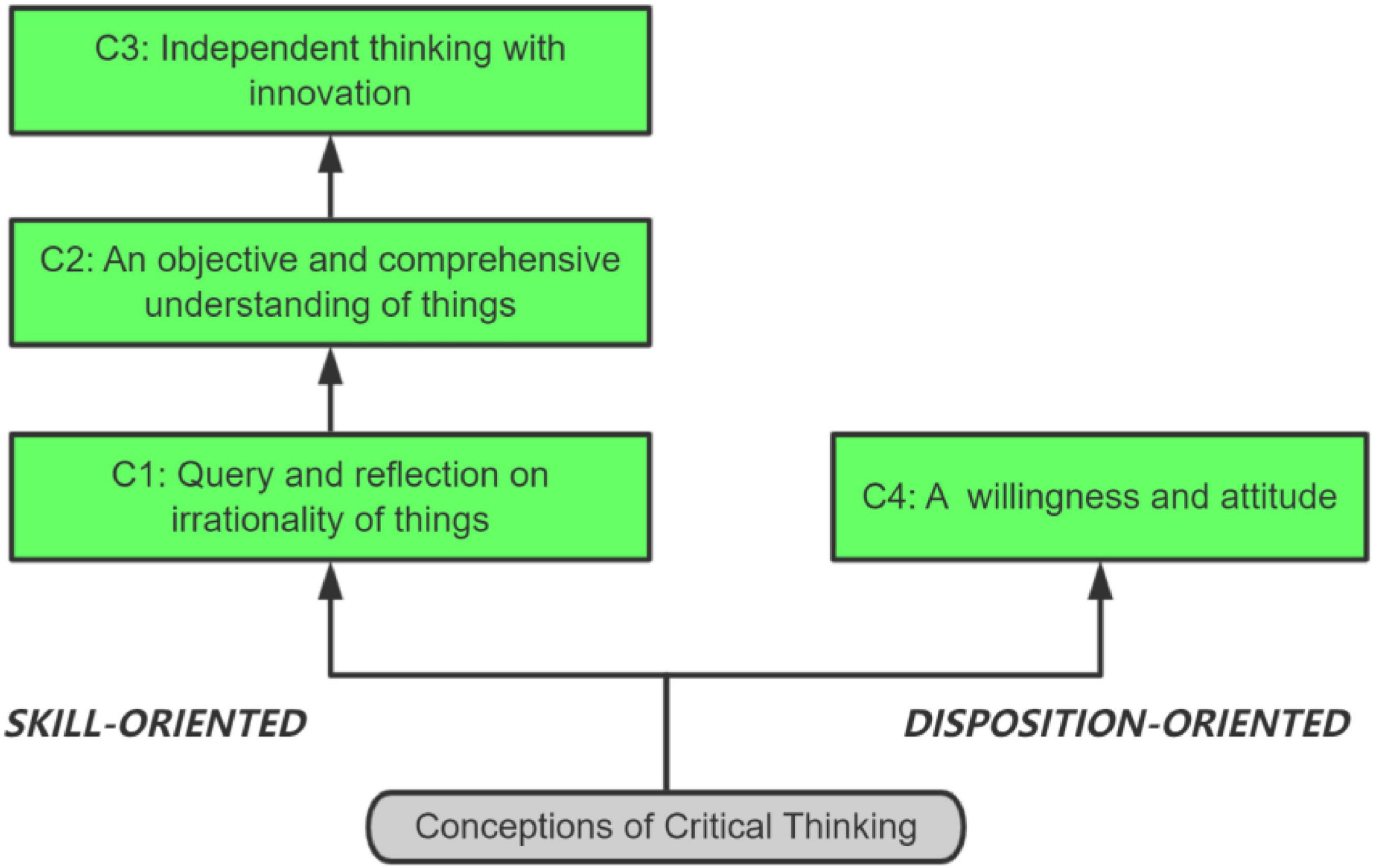

Based on the above findings, the four conceptions can be presented as a structurally related “outcome space” of conceptions of critical thinking (as seen in Figure 1 ). In the light of the theory of phenomenography, each conception of critical thinking is a reflection of different dimensions of experience and has qualitative differences from the other three conceptions. Furthermore, there is a hierarchical relationship between the four conceptions. In contrast with lower-ranked conceptions, higher-ranked conceptions are much more complex and contain new elements.

Figure 1. The outcome space.

Conception 1 is the most basic type of conception of critical thinking exemplified by questioning and reflecting on the irrationality of things—but only one side of things is considered in this way. Although “questioning” and “denying” are indeed two of the prominent features of critical thinking, they are not the only ones. People are not required to immediately deny things absolutely in critical thinking about certain views, judgments, and phenomena. However, many people equate critical thinking with absolute opposition and negation, which is a narrow or even wrong understanding. From this point of view, Conception 2, which can recognize both advantages and disadvantages of things and observe from multiple perspectives, is superior to Conception 1.

Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy of learning objectives is a starting point for identifying the necessary skills of critical thinking. He put forward the six classifications of educational goals in the cognitive field: knowledge, understanding, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) revised the stage of the human cognitive process to progress from a lower to higher advancement, that is, memorization, understanding, application, analysis, evaluation, and innovation. Comparing the six classifications with the findings of this study, it can be seen that the students’ behaviors in analyzing problems, such as identifying different levels of things, phenomena, and views to acquire a more objective and comprehensive understanding, are fully embodied in Conception 2.

Corresponding to the innovation level, and regarded as the highest level of thinking, Conception 3, the emphasis on the construction of new conceptions or solutions with strong originality based on independent personal thinking, is a display of the rich imagination and creativity of students, as well as a reflection of their pioneering spirit in response to their existing knowledge and information. According to the six-level theory of cognitive process proposed by Bloom (1956) and Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) , Conceptions 2 and 3 should be in a progressive hierarchical relationship.

The hierarchy between conceptions can be seen in Figure 1 , which shows a hierarchy of increasing complexity based on inclusively expanding awareness. Like Conception 1, Conception 2 includes awareness of searching for irrationality as part of critical thinking, but adds awareness of using multiple perspectives. Similar to Conception 2, Conception 3 includes awareness of multiple perspectives, but adds the notion of independent thinking and innovation. However, Conception 4 shifts the focus from skills to dispositions. As stated, both skill and disposition are indispensable aspects for critical thinking ( Liu et al., 2021 ), the former deals with the abilities and the latter deals with inclination or willingness. Nevertheless, it may not be reasonable to contend which aspect is more superior to the other, as they deal with different dimensions of critical thinking ( Hemming, 2000 ).

Support for each of the conceptions of critical thinking found in this study may be found in the literature. For Conception 1, the undergraduates are critical of both others and themselves. They have a tendency to find fault with others ( Wu, 2011 ), which is similar to what Moore (2013, p. 512) refers to as “a propensity to judge in a negative way.” Additionally, they are able to exercise self-reflection or self-correction. The analogous expressions can also be found in Moore’s (2013) finding of self-reflexivity, where the participants claimed that it was important to critically inspect their own conceptions and opinions. In general, the participants holding this conception place great emphasis on flaw finding or criticizing, which might be due to a translation problem ( Chen, 2017 ). The word “critical” has been translated into Chinese as pi pan , the meaning of which resembles criticizing ( Wu, 2011 ). Other important meanings, such as logical thinking and decision making are devalued or even ignored, which implies that it is not easy for some western concepts to be accurately understood and assimilated in the Chinese context.

The participants holding Conception 2 see both sides of things: in Phillips and Bond’s (2004, p. 284) words, they weigh up both “pros and cons, positives and negatives.” They also emphasize being objective, fair, neutral, and less biased ( Phillips and Bond, 2004 ). Chen (2017, p. 147) terms this conception “ the omnipresence of the opposite point of view ,” the root of which can be found in indigenous Chinese philosophy. The dialectics of Chinese philosophy hold that black and white are ubiquitous, meaning that contradictions have always existed in the world. People should look at things from both sides. Another reason, as the students in the research add, is to better distinguish and filter useful and beneficial information. As S33 states, “one would be overwhelmed and misled by the information ocean unless he/she can weigh up the positives and negatives.” Other participants go beyond the simple differentiation of black and white to view things from diverse perspectives. For them, the value judgment of right or wrong, positive and negative is less important. As Phillips and Bond (2004, p. 285) contend, the emphasis is put on “seeing multiple angles and perspectives.” The interviewees in Phillips and Bond’s (2004) study stress the outcome or, more specifically, the diverse decisions and solutions as a result of standing in varying positions. Our participants, however, aim to achieve more comprehensive ways to understand things around them because of different perspectives. Regardless of both sides or multiple angles, the core of this conception of critical thinking is about the perspectives from which students view the world.

Conception 3 is similar to the intellectual autonomy, with which people tend to accept only what they have found themselves, and rely only on their own cognitive, investigative and inferential capacities ( Fricker, 2006 ). Likewise, Chen (2017) also uses the term in his study with Chinese college students, who stress the significance of originality. While the students in Chen’s (2017) research talk about having their own opinions that differ from those of teachers or parents, the participants in this study relate independent thinking to the situations where they have to face an overwhelming amount of information. Also in this conception, the participants relate critical thinking to innovation, which verifies Lucas’ (2019) finding that Chinese students connect critical thinking with innovative activities. Moore (2013) terms it “a simple originality,” which goes beyond challenging existing ideas and knowledge to produce something new to contribute to knowledge. The students attach importance to the “ownership of their ideas” ( Chen, 2017 , p. 145) and the production of thinking, or more specifically, the generation of new insights ( Lucas, 2019 ). The difference in this study is that the participants discuss the innovation of thinking at a macro level, i.e., the contribution of innovative thinking to society and the whole nation, rather than being confined to knowledge or scholarship.

Conception 4 is inherently a focus on disposition and attitudes, not just skills, in critical thinking. Undoubtedly, epistemic skills are crucial for critical thinking, yet scholars have contended that dispositions and attitudes are equally important to carry out the skills ( Pithers and Soden, 2000 ; Stapleton, 2001 ; Davies and Barnett, 2015 ). Critical spirit has been defined as the tendency or disposition to think critically in a variety of contexts in a regular manner ( Siegel, 1988 ). To be a critical thinker, one should have the “willingness to inquire” ( Hamby, 2015 , p. 77). As Davson-Galle (2004 , p. 504) argues, “[i]t is one thing to be able to think critically; it is another thing to be willing to exercise that ability.” Critical spirit is the driving force for people’s engagement in critical thinking ( Siegel, 1988 ); that is, it helps to understand what motivates individuals to apply critical skills and view phenomena from a critical perspective ( Hemming, 2000 ). Furthermore, those who possess critical thinking skills may not have a well-developed critical spirit, yet others “may have developed a disposition which views the world with a more critical eye,” even if they do not possess as many skills as others ( Hemming, 2000 , p. 177).

Students have demonstrated attitudes such as “dare to question authority” (S18), “dare to seek evidence” (S58), and “keep curiosity” (S53). However, the essays relating to dispositions or attitudes are few and only mention limited dispositional traits of critical thinking as proposed by Facione and Facione (1992) , such as inquisitiveness and truth-seeking. The findings are also consistent with early surveys which conclude that Chinese students have negative dispositions toward critical thinking ( Tiwari et al., 2003 ; Zhu et al., 2005 ; He et al., 2006 ).

Conclusion and implications for teaching in higher education

To sum up, the research found that Chinese undergraduates possessed four different conceptions of critical thinking and revealed a progressively hierarchical relationship between the four. Conception 1, questioning and reflecting on the irrationality of things, is the least complex conception. To scrutinize and recognize things comprehensively is encouraged in the more complex Conception 2. Conception 3, independent thinking with innovation is more complex than Conceptions 1 and 2, and creativity is emphasized. Conception 4 elevates critical thinking to a kind of willingness and attitude.

Based on the above analysis, two key problems are revealed: first, the progress of cultivating undergraduates’ critical thinking in higher education is not satisfactory as some students only recognize some basic and superficial conceptions instead of deep understandings. Second, the cultivation of critical thinking is mainly focused on tangible rather than intangible aspects, as evidenced by the fact that most students can be aware of the skill dimension, but only a minority realize the dispositional dimension.

The first implication for university teaching is that lecturers should play an active role in equipping undergraduates with deepened conceptions of critical thinking in the daily routine of teaching and learning. To this end, it is vital that teachers should have acquired correct and comprehensive understandings and can undertake the responsibility of advocating the critical disposition. Lecturers are expected to be motivators for students rather than the embodiment of authority and possessors of knowledge. Students should be encouraged to question, criticize, make independent judgments from different perspectives, and search for relevant evidence to support their views. Furthermore, teachers should strive to create a democratic, active and free academic discussion environment where different viewpoints are accepted and tolerated. Efforts should be made to enable students to realize that critical thinking is not only a skill, but also an attitude and willingness. It is not enough to only focus on the skills: critical thinking cannot be acquired and maintained through repeated, mechanical, uninteresting training. If students do not have a clear understanding and a deep recognition of mastering critical thinking, they will not agree with the value of critical thinking from their hearts. As a result, their conscious support for critical thinking may be lost, and students’ motivation for learning will decrease or even disappear. Qian (2018) points out that critical thinking education can not only improve students’ thinking ability, but also shape their values and life attitudes.

Second, critical thinking should be promoted in both specific and integrated ways. Even though some researchers question the possibility of teaching critical thinking ( Willingham, 2008 ; Weissberg, 2013 ), there is an emerging consensus that critical thinking should be taught and viewed as a component of education ( Aktoprak and Hursen, 2022 ). It is expected that universities will develop critical thinking skills through institutionalized and formalized courses, i.e., individual critical thinking course ( Ennis, 2018 ), which can be proved by recent empirical evidence ( Abrami et al., 2015 ). Yu and Gao (2017) claim that critical thinking is a unique way of thinking with unique rules, formation mechanisms, and promotion strategies and needs to be cultivated in a targeted manner. Critical thinking requires certain thinking skills and techniques acquired through specific courses. Additionally, the integrated courses are more implicit. For such courses, the fostering of critical thinking skills and disposition is valued while maintaining the professional or disciplinary teaching mode. In this way, the training of skills and the disposition of critical thinking are both developed. More group discussions, debates and presentations are used to stimulate students to express and defend their own opinions and ideas, and doubt, criticize and argue against others’ viewpoints. Meanwhile, more real cases or events can be introduced to bridge the course content and the real world and stimulate thinking. Moreover, routine learning tasks can be added with more critical elements. For example, students could choose some reading material (books, articles, etc.) and then write a reasoned critique on its flaws and omissions.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Southwest University. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

XZ wrote and refined the introduction, research design, and findings sections. XL wrote and refined the study’s discussion and conclusion sections. Both authors were involved in preparing the manuscript.

This research was supported by the Chinese National Education Science Planning Project (BIA210200).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Waddington, D. I., Wade, C. A., and Persson, T. (2015). Strategies for Teaching Students to Think Critically. Rev. Educ. Res. 85, 275–314. doi: 10.3102/0034654314551063

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Åkerlind, G. S. (2005). Variation and commonality in phenomenographic research methods. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 24, 321–334.

Google Scholar

Åkerlind, G., Bowden, J. A., and Green, P. (2005). “Learning to do phenomenography: A reflective discussion,” in Doing Developmental Phenomenography , eds J. Bowden and P. Green (Melbourne: RMIT University Press).

Aktoprak, A., and Hursen, C. (2022). A bibliometric and content analysis of critical thinking in primary education. Think. Skills Creat. 44, 1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2022.101029

Anderson, L. W., and Krathwohl, D. R. (eds) (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Complete Edition. New York, NY: Longman.

Arisoy, B., and Aybek, B. (2021). The Effects of Subject-Based Critical Thinking Education in Mathematics on Students’ Critical Thinking Skills and Virtues. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 21, 99–120. doi: 10.14689/ejer.2021.92.6

Bailin, S., Case, R., Coombs, J. R., and Daniels, L. B. (1999). Conceptualizing critical thinking. J. Curr. Stud. 31, 285–302. doi: 10.1080/002202799183133

Bali, M. (2015). “Critical thinking through a multicultural lens: Cultural challenges of teaching critical thinking,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education , eds M. Davies and R. Barnett (Berlin: Springer), 317–334. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2019-105866

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Barnett, R. (1997). Higher Education: A Critical Business. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Behar-Horenstein, L. S., and Niu, L. (2011). Teaching critical thinking skills in higher education: A review of the literature. J. Coll. Teach. Learn. 8, 25–42.

Bellaera, L., Weinstein-Jones, Y., Ilie, S., and Baker, S. T. (2021). Critical thinking in practice: The priorities and practices of instructors teaching in higher education. Think. Skills Creat. 41;100856.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). “Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational goals,” in Handbook 1, Cognitive Domain , Ed. B. S. Bloom (New York, NY: Longman).

Cáceres, M., Nussbaum, M., and Ortiz, J. (2020). Integrating critical thinking into the classroom: A teacher’s perspective. Think. Skills Creat. 37:100674.

Chen, L. (2017). Understanding critical thinking in Chinese sociocultural contexts: A case study in a Chinese college. Think. Skills Creat. 24, 140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2017.02.015

Dai, C. Y., Chen, T. W., and Rau, D. C. (2012). “The application of mobile-learning in collaborative problem-based learning environments,” in Instrumentation, Measurement, Circuits and Systems (Berlin: Springer), 823–828.

Davies, M., and Barnett, R. (2015). “Introduction,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education , eds M. Davis and R. Barnett (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan), 1–26.

Davson-Galle, P. (2004). Philosophy of science, critical thinking and science education. Sci. Educ. 13, 503–517. doi: 10.1023/b:sced.0000042989.69218.77

Dwyer, C. P., and Walsh, A. (2019). An exploratory quantitative case study of critical thinking development through adult distance learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 68, 17–35. doi: 10.1007/s11423-019-09659-2

Ennis, R. (1991). Critical thinking. Teach. Philos. 14, 5–24. doi: 10.5840/teachphil19911412

Ennis, R. H. (2018). Critical thinking across the curriculum: A vision. Topoi 37, 165–184. doi: 10.1007/s11245-016-9401-4

Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction. Research Findings and Recommendations. Newark, DE: American Philosophical Association. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED315423).

Facione, P. A., and Facione, N. C. (1992). The California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CCTDI) Test Administration Manual. Millbrae, CA: California Academic Press.

Fong, C. J., Kim, Y., Davis, C. W., Hoang, T., and Kim, Y. W. (2017). A meta-analysis on critical thinking and community college student achievement. Think. Skills Creat. 26, 71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2017.06.002

Fricker, E. (2006). “Testimony and Epistemic Authority,” in The Epistemology of Testimony , eds J. Lackey and E. Sosa (New York, NY: Oxford University Press).

Ghanizadeh, A. (2017). The interplay between reflective thinking, critical thinking, self-monitoring, and academic achievement in higher education. High. Educ. 74, 101–114. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0031-y

Green, P. (2005). “A rigorous journey into phenomenography: From a naturalistic inquirer standpoint,” in Doing Developmental Phenomenography , eds J. Bowden and P. Green (Melbourne: RMIT University Press).

Grussendorf, J., and Rogol, N. C. (2018). Reflections on Critical Thinking: Lessons from a Quasi-Experimental Study. J. Polit. Sci. Educ. 14, 151–166. doi: 10.1080/15512169.2017.1381613

Hamby, B. (2015). “Willingness to Inquire: The cardinal critical thinking virtue,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education , eds M. Davis and R. Barnett (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan), 77–87.

He, H., Zhang, Y. M., and Zhao, Y. Q. (2006). A survey of critical thinking ability in college students. Chin. Nurs. Res. 20, 775–776.

Hemming, H. (2000). Encouraging critical thinking: “But.what does that mean?”. McGill J. Educ. 35, 173–186.

Larsson, K. (2017). Understanding and teaching critical thinking—A new approach. Int. J. Educ. Res. 84, 32–42. doi: 10.1187/cbe.12-11-0201

Liu, C., Yu, P., Hou, J., and Wang, Y. (2021). How interactive discussion pattern affects learners’ critical thinking in online learning. e-Education Res. 3, 48-54+61. [In Chinese]

Liu, O. L., Shaw, A., Gu, L., Li, G., Hu, S., Yu, N., et al. (2018). Assessing college critical thinking: preliminary results from the Chinese HEIghten ® Critical Thinking assessment. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 37, 999–1014.

Liyanage, I., Walker, T., and Shokouhi, H. (2021). Are we thinking critically about critical thinking? Uncovering uncertainties in internationalised higher education. Think. Skills Creat. 39:100762.

Lucas, K. J. (2019). Chinese Graduate Student Understandings and Struggles with Critical Thinking: A Narrative-Case Study. Int. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 13:5. doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2019.130105

Marton, F. (1981). Phenomenography - Describing conceptions of the world around us. Instr. Sci. 10, 177–200. doi: 10.1007/bf00132516

McLaughlin, A. C., and McGill, A. E. (2017). Explicitly teaching critical thinking skills in a history course. Sci. Educ. 26, 93–105.

Moore, T. (2013). Critical thinking: seven definitions in search of a concept. Stud. High. Educ. 38, 506–522. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2011.586995

Paul, R., and Elder, L. (1999). Critical thinking: Teaching student to seek the logic of things. J. Dev. Educ. 1, 34–35.

Phillips, V., and Bond, C. (2004). Undergraduates’ experiences of critical thinking. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 23, 277–294. doi: 10.1080/0729436042000235409

Pithers, R. T., and Soden, R. (2000). Critical thinking in education: A review. Educ. Res . 237–249.

Qian, Y. (2018). Educating students in critical thinking and creative thinking: Theory and practice. Tsinghua J. Educ. 39, 1–16.

Ren, X., Tong, Y., Peng, P., and Wang, T. (2020). Critical thinking predicts academic performance beyond general cognitive ability: evidence from adults and children. Intelligence 82:101487. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2020.101487

Schmaltz, R. M., Jansen, E., and Wenckowski, N. (2017). Redefining critical thinking: Teaching students to think like scientists. Front. Psychol. 8:459. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00459

Shaw, A., Liu, O. L., Gu, L., Kardonova, E., Chirikov, I., Li, G., et al. (2020). Thinking critically about critical thinking: validating the Russian HEIghten ® critical thinking assessment. Stud. High. Educ. 45, 1933–1948.

Siegel, H. (1988). Educating Reason: Rationality, Critical Thinking and Education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Stapleton, P. (2001). Assessing critical thinking in the writing of Japanese University students. Writ. Commun. 18, 506–548. doi: 10.1177/0741088301018004004

Svensson, L., and Theman, J. (1983). The Relation Between Categories of Description and an Interview Protocol in a Case of Phenomenographic Research (Research Report No. 1983:02). Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, Department of Education.

Tiwari, A., Avery, A., and Lai, P. (2003). Critical thinking disposition of Hong Kong Chinese and Australian nursing students. J. Adv. Nurs. 44, 298–307. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02805.x

Weissberg, R. (2013). Critically thinking about critical thinking. Acad. Quest. 26, 317–328. doi: 10.1007/s12129-013-9375-2

Willingham, D. T. (2008). Critical thinking: Why is it so hard to teach? Arts Educ. Policy Rev. 109, 21–32. doi: 10.3200/aepr.109.4.21-32

Wu, H. (2011). Critical thinking: Study of the semantics. J. Yanan Univ. 33, 5–17.

Yu, S., Wang, G., Nie, S., and Yuan, M. (2015). Research on promoting the problem-solving learning activity model for critical thinking development. e-Education Research 7, 35–41+72.

Yu, Y., and Gao, S. (2017). The mode and implications of the cultivation of critical thinking in the US. Modern Univ. Educ. 4, 61–68.

Yuan, G. (2012). The way to produce innovative talents: From the perspective of critical thinking. J. High. Educ. Manag. 6, 50–54.

Zhong, Q. (2002). Critical thinking and teaching. Glob. Educ. 1, 34–38.

Zhu, X. L., Feng, W. H., and Yan, W. H. (2005). Testing critical thinking ability among college nursing students. Chin. Nurs. Res. 20, 84–86.

Keywords : critical thinking, undergraduates, conceptions, phenomenography, teaching

Citation: Zhao X and Liu X (2022) How do Chinese undergraduates understand critical thinking? A phenomenographic approach. Front. Educ. 7:956428. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.956428

Received: 30 May 2022; Accepted: 05 September 2022; Published: 20 September 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Zhao and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xu Liu, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Probability and its Paradoxes for Critical Thinking

Journals By Subject

- Proceedings

Information

Study on the Characteristics of the Chinese Students’ Critical Thinking

School of Culture and Media, Central University of Finance and Economics, Beijing, China

Contributor Roles: Shi Jing is the sole author. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Add to Mendeley

The critical thinking trait is the premise and foundation of innovative thinking, and has become the necessary ability and core quality for cultivating innovative talents. Different scholars have different understandings about the definition and constituent elements of the characteristics of thinking and critical thinking. Their common view is that the characteristics of thinking is the intention and will of thinking activity, and the characteristics of critical thinking is the individual tendency of critical thinking. Facts have proved that the general lack of critical thinking ability of Chinese students has become a defect in their qualities. Thus, the education of critical thinking should start from primary education, and the cultivation of critical thinking at university stage should strengthen the existing foundation laid in primary and secondary schools. Faced with the educational growth process of these potential innovative talents of the Chinese students, this paper puts forward five countermeasures and suggestions on the cultivation of critical thinking characteristics, which have theoretical and practical significance for promoting the reform of critical thinking teaching, improving the level of critical thinking of the Chinese students, improving the qualities of cultivating innovative talents and promoting independent innovation.

Characteristics of Thinking, Critical Thinking, Innovative Talents, Teaching Reform

Shi Jing. (2020). Study on the Characteristics of the Chinese Students’ Critical Thinking. Higher Education Research , 5 (3), 94-102. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.her.20200503.14

Shi Jing. Study on the Characteristics of the Chinese Students’ Critical Thinking. High. Educ. Res. 2020 , 5 (3), 94-102. doi: 10.11648/j.her.20200503.14

Shi Jing. Study on the Characteristics of the Chinese Students’ Critical Thinking. High Educ Res . 2020;5(3):94-102. doi: 10.11648/j.her.20200503.14

Cite This Article

- Author Information

Verification Code/

The verification code is required.

Verification code is not valid.

Science Publishing Group (SciencePG) is an Open Access publisher, with more than 300 online, peer-reviewed journals covering a wide range of academic disciplines.

Learn More About SciencePG

- Special Issues

- AcademicEvents

- ScholarProfiles

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Conference Organizers

- For Librarians

- Article Processing Charges

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Peer Review at SciencePG

- Open Access

- Ethical Guidelines

Important Link

- Manuscript Submission

- Propose a Special Issue

- Join the Editorial Board

- Become a Reviewer

Exploring Criticality in Chinese Philosophy: Refuting Generalisations and Supporting Critical Thinking

- Open access

- Published: 09 November 2022

- Volume 42 , pages 123–141, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ian H. Normile ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1828-0034 1

2943 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Much of the literature exploring Chinese international student engagement with critical thinking in Western universities draws on reductive essentialisations of ‘Confucianism’ in efforts to explain cross-cultural differences. In this paper I review literature problematising these tendencies. I then shift focus from inferences about how philosophy shapes culture and individual students, toward drawing on philosophy as a ‘living’ resource for understanding and shaping the ideal of critical thinking. A cross disciplinary approach employs historical overview and philosophical interpretation within and beyond the Confucian tradition to exemplify three types of criticality common in Chinese philosophy. These are criticality within tradition, criticality of tradition, and critical integration of traditions. The result is a refutation of claims or inferences (intentional or implicit) that Chinese philosophy is not conducive to criticality. While this paper focuses on types of criticality, it also reveals a common method of criticality within Chinese philosophy, in the form of ‘creation through transmission’. This resonates with recent research calling for less confrontational and more dialogical engagement with critical processes. However, I also draw attention to examples of confrontational argumentation within Chinese philosophy, which may provide valuable resources for educators and students. Finally, I conclude careful and explicit consideration is needed regarding the types of criticality sought within Western universities to prevent educators and students from ‘speaking past’ one and other instead of ‘speaking with’ one and other in critical dialogue.

Similar content being viewed by others

A Practitioner-Research Study of Criticality Development in an Academic English Language Programme

Transformative Critique: What Confucianism Can Contribute to Contemporary Education

‘critical thinking’ and pedagogical implications for higher education.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Scholars reviewing research on Chinese international student engagement with critical thinking in Western Footnote 1 universities have identified tendencies to draw on reductive essentialisations of ‘Confucian heritage’ to explain difficulties engaging with critical thinking (Clark and Gieve, 2006 ; Heng, 2018 ; Li, 2017 ; Moosavi, 2020 ; O'Dwyer, 2016 ). This paper reviews and contributes to a growing body of literature problematising such essentialism and generalisation. To avoid these problems, I shift focus from inferences about how philosophy manifests in contemporary culture, specific practices, or groups of students, toward drawing on philosophy—past and present—as a ‘living’ resource for understanding and actively shaping the normative concept of critical thinking. This theoretical shift is justified by the fact that critical thinking is not a description of how people do think, but an ideal of how people ought to think in certain situations for certain purposes. Furthermore, the norms and ideals shaping dominant conceptions of critical thinking are typically rooted in, and derived from, the Western philosophic traditions (Tan, 2017 ). However, this is not because ‘the West’ (an equally problematic term of generalisation) has any monopoly on criticality. Consequently, exploring Chinese philosophy may shed new light on an old concept. Light much needed in the increasingly international contexts of Western higher education.

I begin by providing an outline of critical thinking and its relationship to traditions. The aim is to draw on commonly agreed features of criticality to facilitate exploration of its manifestations within Chinese philosophy. I then review literature problematising tendencies toward cultural generalisation and reductive essentialisation of Chinese philosophy within existing research. Next, I draw on a cross-disciplinary approach, employing historical overview and philosophical analysis to show three types of criticality within Chinese philosophy. These are criticality within tradition, criticality of tradition, and critical integration of traditions. This is done by exploring criticality within the Confucian tradition through examples from the Analects and the critical evolution of Confucian theory through Mencius and Xunzi. I then briefly consider the influence of Buddhist metaphysics on Neo-Confucianism to exemplify critical integration of traditions within Chinese philosophy. Next, I shift attention beyond Confucianism, to show criticality of tradition along with further critical integration of traditions. This is done by looking at Daoist and Mohist philosophy of the ancient Warring States Period and the impact of Western philosophy in China beginning in the nineteenth century. I conclude by considering the implications of this work for research and practice.

The prioritisation of breadth over depth in this approach is deemed necessary because the diversity of Chinese philosophy is not well represented in Anglophone critical thinking literature (Moosavi, 2020 ). Furthermore, attention to breadth serves my primary aims of problematising reductive generalisations and refuting claims or inferences (intentional or implicit) that Chinese philosophy is not conducive to criticality. Importantly, in demonstrating the critical capacity of Chinese philosophy, I make no effort to ‘explain’ or describe Chinese culture or students, both of which are too diverse and dynamic to generalise. This is not to deny the interconnectivity of philosophy, culture, and individuals but simply an analytical separation facilitating focus on one aspect of an interrelated totality. My point is that if Chinese international students struggle with critical thinking, it is not the inevitable result of inherently uncritical philosophy. Quite the contrary, Chinese philosophy contains great potential as a ‘living’ resource capable of informing the conceptualisation and practice of critical thinking. In service of actualising this potential, I provide examples of criticality within Chinese philosophy. Importantly, while the focus here is on Chinese philosophy, this work has relevance for anyone interested in exploring and better understanding criticality within and across traditions more generally.

Criticality and Tradition

Critical thinking has a long history of definition and redefinition (Ennis, 2016 ; Johnson and Hamby, 2015 ). For the purposes of this paper, I draw on basic but broadly agreed aspects of critical thinking, conceived of as a process of reasoning about what to believe and how to act, the exercising of which requires a combination of knowledge, skills, and dispositions (Bailin and Siegel, 2003 ; Ennis, 2016 ; Facione, 1990 ). Such a simplified definition cannot capture the complexity of all criticality. However, this very general approach highlights a key aspect of critical thinking; the fact that it is necessarily criteriological (ibid). There must be some form of criteria by which reasons for thought and action are justified. The origin and nature of the criteriological framework(s) guiding criticality within and across contexts are the source of much philosophical debate. Some suggest such frameworks can only be achieved through consensus and practice (Rorty, 1991 ). Others argue the very possibility of commensurability between critical frameworks logically entails transcendent meta-criteria capable of guiding universal rationality, and thus criticality (Siegel, 2017 ). Biesta and Stams draw on Derrida to claim, “…there are no pure, uncontaminated, original criteria on which we can simply and straightforwardly base our judgments” (2001, p. 68). In this view we are always embedded within a context of assumptions, the ultimate boundaries of which cannot be comprehended or transcended, yet criticality can reveal new possibilities without recourse to foundational, self-selected, or transcendent criteria (2001). This is an important debate for criticality, the justification of critique within philosophy, and questions about the nature of rationality. However, it is not a debate I can settle here. In this paper, I am not claiming to provide a ‘new’ conception of critical thinking. Instead, I am pointing out the unsettled complexity of the topic and drawing on examples from Chinese philosophy to provide perspectives typically not considered in the critical thinking literature.

What is most relevant for this paper is that the sources of criteria guiding criticality are commonly understood to be contextually dependent on factors such as discipline, practice, and culture (Evers, 2007 ; McPeck, 2016 ). What constitutes good reasons, which values guide judgment, and how those values are conceived may vary depending on the purposes toward which critical thinking is directed and the context in which it is practiced. Consequently, to account for contextual variance, the preceding conception of critical thinking can be expanded to include reflexive examination, and potential transformation, of the aims, assumptions, and criteria guiding critical thinking and action. Barnett and Davies call this a form of ‘metacritique’ (Barnett, 1997 ; Davies, 2015 ) and Lipman identifies it as the ‘self-correcting’ aspect of criticality (2012). Critical thinking, then, is not only a process of reasoning about what to believe and how to act, but also a process that questions the aims, assumptions, and criteria guiding reasoning itself. This conception of critical thinking recognises the ‘internal’ coherence of reasoning may vary by context. However, it also requires questioning the aims and assumptions that guide that reasoning. Consequently, the antithesis of criticality is ideology, the unquestioning adherence to any set of aims and assumptions as an immutable guide to reasoning, belief, and action.

The primary ‘contexts’ under consideration in this paper are various traditions of Chinese philosophy. While the boundaries of traditions are difficult to delineate, they also provide enough pragmatic clarity to meaningfully explore criticality without having to resolve debates on the ‘ultimate’ nature of criticality. Traditions are defined by constellations of aims, assumptions, and criteria. For example, ancient Confucian traditions assume the value of learning and ritual in meeting the aims of social harmony. These, and other aims and assumptions, guide reasoning within the tradition. The fact that traditions (philosophical and otherwise) are shaped by pre-existing aims and assumptions does not preclude, but in fact creates, the possibility for criticality. For example, a tradition may encounter what MacIntyre calls an ‘epistemic crisis’ resulting from inadequacy in practical explanation or breakdowns of internal coherence (1990; 1988). This can derive from new experiences and ideas or contact with other traditions, which creates opportunities for criticality within tradition, of tradition, or critical integration between traditions. However, holding any assumptions as unassailable, particularly in the face of epistemic crisis or when encountering alternatives, constitutes uncritical dogmatism.

These different types of criticality and how they articulate with traditions can be understood through analogy with the playing of a game. In such an analogy, one of the most fundamental assumptions is that a particular game (a tradition) ought to be played. The most likely underlying aim is to ‘win’ the game. However, other aims, such as enjoyment or display of style may also influence the nature of play. The rules of the game are equivalent to the criteria guiding criticality. Using this analogy, dogmatism is playing the game without questioning the aims or rules. This may be highly uncritical if it involves playing in a proscribed manner or by a dictated strategy. However, it may also include a degree of critical (perhaps calculated is a better word) reasoning about overall aims and what moves to make in service of achieving those aims without questioning the rules of the game . Criticality within tradition, questions the rules of the game. This does not require breaking the rules, as there are means by which the rules of a game can be agreeably changed by the participants. Criticality of tradition suggests playing a new game altogether. This may result in radical transformation akin to a Kuhnian paradigm shift or serve to strengthen existing assumptions and reaffirm the value of the current game. Critical integration between traditions arises when a new game is encountered, providing opportunities to combine criticality within and of tradition to either internally transform the rules of the existing game, or perhaps create a new game altogether. It is not, however, simply abandoning one game to play another, as that would lack integration.

Finally, I must note why I use criticality and critical thinking as interchangeable synonyms. A case can be made for separating the two concepts (Davies, 2015 ). While I am open to the possibility of such a distinction having value in many contexts, I make no such distinction here because I think this separation sells short the broader aims, and spirit, of criticality in higher education. Many theorists and practitioners lament critical thinking being taught and practiced in Western universities as an instrumentalised processes of proposition evaluation and argumentation (Barnett, 1997 ; Davies, 2015 ; Thayer-Bacon, 1998 ) . The intention here is not to diminish the centrality of thinking, or value of logic, to critical thinking, but simply to recognise the types of criticality I aim to identify within Chinese philosophy are not focused only on procedures of thought or discursive processes, but on critical changes to the way people reason and judge what to believe and how to act. I am concerned with demonstrating criticality that changes the ‘rules’ of the game or proposes an entirely new ‘game’ to play. This is the type of criticality many suggest is absent from Chinese philosophical traditions. My aim is to refute any such assumption.

Problematising the ‘Construct of the Chinese Learner’

Why do Chinese international students struggle to think critically while studying in Western universities? This is a problematic question, laden with assumptions (that they do), cultural generalisation (that all Chinese students are somehow similar), and, very often, philosophical reductivism (the nature of that similarity is a homogeneous form of ‘Confucianism’). Despite these problems, it is also a question many educators and students find themselves asking, because many students do struggle with critical thinking while studying abroad (Durkin, 2007 ; Sun et al., 2018 ; Wu and Hammond, 2011 ; Wu, 2015 ). Research also shows challenges with critical thinking within Chinese higher education (Jiang, 2013 ; Li and Wegerif, 2013 ; Tan, 2020 ; Tian and Low, 2011 ). This leads some scholars to claim ‘Confucian culture’ is not conducive to ‘Western’ style criticality (Atkinson, 1997 ; McBride et al., 2002 ). In an example of extreme generalisation, Dong claims,

It has been commonly acknowledged that Chinese traditional culture is generally uncritical… Confucianism shaped a tradition that valued respect for parents and the elderly, the collective good, social order, and harmony. This is in contrast with ancient Greek civilization, which valued independent thought, reason, and ability to debate and argue in public (2015, p. 357).

It is unclear why respect for elders and pursuit of social harmony (aims shared by many Ancient Greek philosophers) are necessarily uncritical. Furthermore, implicit in this statement is the idea that ‘Chinese traditional culture’ is essentially ‘Confucian’. While there is no doubt Confucian philosophy has an immense impact on Chinese culture, such an observation overlooks the diversity and plurality of culture, while also obscuring the complexities of Confucian philosophy as a resource for actively reshaping culture and reconceptualising normative concepts like critical thinking.

Reductive essentialisation of Confucian philosophy is increasingly seen as problematic. Ryan and Louie contend that treating 2,500 years of ‘Confucianism’ as the same thing is like treating the various manifestations of Christianity as essentially homogenous (2007). After all, it could be (rather reductively) argued that Catholics, Quakers, and the Ku Klux Klan are all ‘Christians’. Furthermore, contemporary politics probably exert more influence on culture, and certainly on the teaching and learning of critical thinking in contemporary China, than any philosophical tradition (Zhang, 2017 ). Along these lines, any lack of opportunity to cultivate and practice critical thinking in Chinese education as the result of historical or contemporary political circumstances does not necessarily indicate a cultural or philosophical disinclination toward, or lack of ability to engage in, critical thinking (Bali, 2015 ; Tian and Low, 2011 ). It is also important to note research showing the challenges of engaging with critical thinking in a foreign language (Floyd, 2011 ). Linguistic barriers should not be misconstrued as conceptual impediments or lack of capacity. Furthermore, research also shows that while many Chinese students initially struggle with critical thinking while studying abroad, they are capable of developing and learning the required skills and dispositions over time (Wu, 2015 ). Thus, it is problematic to assume the difficulties some Chinese students face while studying abroad are the result of ‘deficit’ instead of merely challenges arising from difference (Heng, 2018 ). Indeed, it is likely most Chinese students do not lack critical thinking, but simply engage in the process differently (Evers, 2007 ; Mason, 2013 ; Shaheen, 2016 ).

This leads some to argue that imposing a Western-centric theory of critical thinking in culturally diverse contexts could be construed as a form of ‘intellectual colonialism’ (Indelicato and Prazic, 2019 ; Moosavi, 2020 ). Indeed, as Hammersley–Fletcher and Hanley point out, critical thinking may become ironically uncritical if it finds itself as a mechanism for “reproducing the interests of particular groups and constraining thought within the boundaries of Western traditions” ( 2016 , p. 990). However, there is nothing ‘colonial’ about Western universities drawing on Western intellectual traditions and practices. Indeed, many international students may choose to study abroad precisely because they want exposure and experience with these traditions and practices. Nevertheless, it is important to recognise the teaching and practice of critical thinking without consideration of its conceptual heritage and underlying assumptions may simply fail to be as efficient or effective in cross-cultural contexts. What is at stake is not necessarily a matter of aims but of effectiveness. However, as I discuss in the conclusion of this paper, questions about the aims of students, educators, and institutions regarding they type of criticality each seeks are important and potentially problematic if inexplicit or unaligned.