Democracy and inequality

- Download the full chapter

Subscribe to the Center for Asia Policy Studies Bulletin

Andrew yeo , andrew yeo senior fellow - foreign policy , center for asia policy studies , sk-korea foundation chair in korea studies @andrewiyeo teresa s. encarnacion tadem , teresa s. encarnacion tadem professor and executive director, center for integrative and development studies - university of the philippines diliman meredith l. weiss , meredith l. weiss professor, rockefeller college of public affairs & policy - university at albany, suny @merweissphd kok-hoe ng , and kok-hoe ng senior research fellow and head, case study unit - lee kuan yew school of public policy byunghwan son byunghwan son associate professor - george mason university @byunghwan_son.

December 2022

- 11 min read

Introduction

A key challenge to democracies in Asia is persistent or rising inequality. The diversity of cases in Asia — characterized by varying levels of economic and political performance — indicates, at best, a complicated relationship between inequality and democracy. To help address this issue, four scholars examine inequality and democratic governance in the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, and South Korea and provide a set of policy prescriptions for policymakers, civil society, and the private sector. Although there is no one-size-fits-all solution, the case studies highlight several common challenges, such as the institutionalization of past unequal practices, and policy prescriptions, such as greater political decentralization. Taken collectively, the papers provide important insights and recommendations to combat inequality, with the aim of strengthening democracies in Asia.

The scholars were chiefly interested in economic inequality. However, in their assessments, they recognized other related dimensions of inequality, including limited or uneven access to education and government services, racial and ethnic inequality, and unequal access to the political process. Unsurprisingly, economic inequality is correlated with many others forms of inequality, which, in turn, limit democracy. For instance, the poor may not be able to exercise their right to vote to voice their concerns, whereas the rich may use their wealth and political connections to influence policy. Practitioners must therefore be mindful of how one form of inequality relates to other forms.

The scholars adopted a flexible understanding of democracy. However, there was greater emphasis on democratic governance given the wide variation in the quality of democracies in Asia. Procedural and normative conceptions of democracy were also considered to a lesser extent.

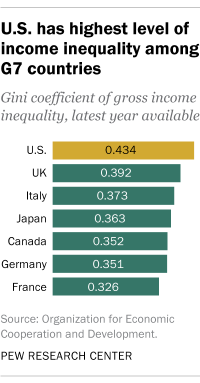

The Gini coefficients measuring inequality in the four countries ranged from 0.3 on the lower end to 0.5 on the higher end of the spectrum. Ordered from the highest to lowest degree of inequality are the Philippines (0.48), Malaysia (0.43), Singapore (0.40), and South Korea (0.31). 1 The Philippines and Malaysia are considered middle-income countries, and South Korea and Singapore are categorized as high-income countries. Even in a wealthy, highly democratic and low inequality society such as South Korea’s, perceptions of inequality can still linger, as depicted in popular Korean dramas and movies such as “Squid Games,” “Sky Castle,” and “Parasite.”

Challenges and recommendations

Despite wide economic and political variation among the four countries, several common challenges and policy recommendations were identified.

- Inequality is only loosely associated with weaker democracies. A loose correlation between inequality and reduced political freedoms (as measured by Freedom House index scores) can be identified when comparing the four countries. However, the fact that some nondemocracies in Asia are characterized by lower economic inequality (in other words, countries with low Gini coefficients) but limited political freedom, such as Cambodia, Myanmar, and Pakistan, indicates that there is no direct, linear relationship between inequality and democracy. Targeting inequality alone will therefore not necessarily improve democratic quality, as other variables such as corruption or racism also correlate with inequality and democracy.

- The problems of inequality and democratic decline are linked to deeper historical legacies and path dependent processes. For example, the dominance of political family dynasties (as seen in the Philippines) contributes to political inequality and corruption. And deep-rooted economic policies favoring particular ethnicities (as seen in Malaysia), as well as programs that single out specific demographic groups (as found in Singapore), lead to the marginalization and social stigmatism of targeted groups, which further contributes to inequality. Policies, both in their design and implementation, should therefore aim to not only fight inequality, but also gradually change public attitudes toward social welfare policies. Principles of universalism that contribute to normalizing access to public services are thus welcome.

- COVID-19 has exacerbated inequality in Asia, but it also provides a window of opportunity. The pandemic may have widened the gap between the rich and poor in Asian countries. However, governments could use the crisis to shift policy in a direction that helps alleviate rising inequality. For instance, in South Korea, the government could use its surplus fiscal capacity to support those small-business owners hit hardest by the pandemic. In the Philippines, additional revenue from a “wealth tax” applied to those at the highest income bracket could help cover the large cost of tackling the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Decentralization offers a means of addressing economic and political inequality. Three of the four papers advocate devolving political and economic processes from the national level to the regional and local levels. The rationale for decentralization may differ in each country, but it commonly helps to redistribute wealth and resources, enhance local political participation, and empower marginalized regions and populations.

- Improved data analysis and greater data transparency could help policymakers better understand and address problems of inequality and democracy. For example, further disaggregation of Bumiputera groups in Malaysian government statistics reveals disparities between peninsula Malays and other ethnic groups. Data disaggregation can help “refine categories and targets so that policy benefits reach the especially vulnerable segments.” The systemic collection of high-quality international data that can be easily compared, as well as increased data access for independent researchers, could help offer new insights and provide additional scrutiny of government policies. For instance, in Singapore, inequality indicators “should be calculated using all household income sources instead of work income only, as is current practice.”

Case study summaries

Philippines.

Raising the issue of inequality has been a major political challenge in the Philippines. Filipino politicians regularly mention poverty and corruption, but as Teresa S. Encarnacion Tadem notes, they rarely address class inequality and its effect on democracy, even though inequality in the country ranks among the highest in Asia. Tackling inequality would mean shedding an uncomfortable spotlight on political family dynasties and their dominance in Philippine political and economic life — a core factor perpetuating inequality and democratic weakness.

Related Books

Shadi Hamid

October 15, 2022

Bruce Jones

September 14, 2021

Tarun Chhabra, Rush Doshi, Ryan Hass, Emilie Kimball

June 22, 2021

To address the interrelated issues of inequality, corruption, and democracy, Tadem points to national and local efforts at decentralization. In particular, she reflects on the 1991 Local Government Code (LGC), a major decentralization policy that “sought to address inequality and empower people to take part in the decision-making process of their respective local government units.” In the spirit of the LGC, Tadem offers several remedies to address regional and class inequality. In the short term, the Philippine government could strengthen socioeconomic policies and nationwide social protection programs, such as the Universal Health Care Act and the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (more popularly known as the conditional cash transfer program) and “push for national programs that encourage popular participation.” In the longer term, Tadem advocates passing an anti-dynasty bill and levying higher taxes on the wealthy to help cover the large cost of addressing the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Malaysia, the relationship between inequality and democracy is also complicated and exacerbated by additional factors. As Meredith L. Weiss argues, “the tight interweaving of political stratification, racial identity, and economic interest in Malaysia” makes reducing inequality an “elusive target.” More specifically, the special status accrued to ethnic Malays and other indigenous communities vis-à-vis other groups (in other words, ethnic Chinese) has “rendered Malay political rights issues inseparable from economic issues.” And these issues have been made more acute by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Malaysia has made rapid economic progress in the past two decades. Its gross domestic product per capita nearly tripled during this period (excluding the 9% decline attributed to the pandemic), and its absolute poverty declined. Inequality has also steadily improved. However, other data point to more limited economic success. For instance, Weiss notes that “60% of the top 1% by income were Chinese and 33% were Bumiputera” in 2014. Although laws favoring the Bumiputera are unlikely to change, inequality can still be addressed by “prioritizing redistributive policies that benefit the many over the already-privileged few, and optimizing transparency and accountability in policy implementation and evaluation.” As a quick and immediate step, “given sharp disparities between peninsular Malays and other Bumiputera,” Weiss suggests disaggregating the Bumiputera in government statistics “to help refine categories and targets.” This step will help ensure that policy benefits reach the most vulnerable populations. In the longer term, institutional decentralization and the devolution of policy authority and fiscal resources could give those in more peripheral areas a greater voice, thereby enhancing democratic inclusivity.

Singapore remains an outlier. As Kok-Hoe Ng states, the country has an “enviable economic track record, high standards of social well-being, and a technically competent bureaucracy.” The public’s trust in government is also high. However, undemocratic practices persist, and Singapore’s pro-market approach to economic growth has resulted in greater inequality. Ng notes that “the top 1% own 32% of the wealth in the economy, while the bottom 50% own just 4%.” Although state intervention is generous in areas that encourage economic markets (for example, universal public education), welfare support for people toiling outside of these markets is minimal. Income (in)security and housing are two areas that highlight how neoliberal economics, existing political practices, and social policymaking hinder democratic growth in Singapore.

In light of these problems, Ng advocates changes in policy design, principles, and processes that could ultimately shift the mindset of Singapore’s relatively “high tolerance” for inequality. As he states, “Minor adjustments to policy design can amount to a shift in the policy paradigm if they are based on a consistent set of principles. From an equality perspective, the most important principles are espousing universalism, prioritizing needs, and normalizing access to public services.” Anti-welfare rhetoric could also be replaced with “policy rules and language that stress universal access and the importance of meeting needs.” Increased transparency would also strengthen policy accountability and efficacy. Greater access to information and the collection of high-quality, internationally comparable social and economic data for independent research and analysis could place checks on policymaking, particularly in polities such as Singapore where electoral competition remains limited.

South Korea

South Korea seems to present an ideal case in which inequality is relatively low and democratic governance and political freedoms are generally high. Moreover, somewhat contrary to popular beliefs, Byunghwan Son finds that economic inequality has not increased in recent years, nor have public perceptions of “unfairness.” However, although these and other data indicators suggest reason for optimism, a narrative of economic injustice seems to persist in popular media. If not managed carefully, Son warns of a potential democratic crisis created by perceptions of inequality, as evidenced by the importance of domestic economic issues in South Korea’s highly polarized 2022 presidential election. Most notable is the shortage in housing in and around Seoul, which reflects a deeper structural problem related to a growing wealth gap between the rich and poor.

To avoid a crisis, Son suggests maintaining, if not further improving, levels of income distribution through fiscal expansion. In the short term, more aggressive social spending is warranted given South Korea’s surplus fiscal capacity, as noted by the International Monetary Fund, and its below average spending compared to other member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. In particular, it would be prudent to further support those small-business owners hit hardest by the COVID-19 pandemic (and that comprise a significant portion of South Korea’s real economy). Also, instituting supply-driven housing policies could help staunch the surge in housing prices and reduce the wealth gap. In the longer term, “decentralization of the national economy, which is heavily centered around Seoul, needs to be more aggressively pursued.” Son argues that decentralization would help “ease up the asymmetric population pressure on the capital area and offer a structural solution to the wealth inequality problem.”

Related Content

Brookings Institution, Washington DC

10:00 am - 11:30 am EST

The authors would like to thank McCall Mintzer, Adrien Chorn, and Jennifer Mason for their assistance with this project, Lori Merritt for editing, Chris Krupinski for layout, Rachel Slattery for web design, and Alexandra Dimsdale for assisting with the publication process.

- Gini coefficient scores are based on data from the World Economic Forum Inclusive Development Index. The scores provided reflect pre-COVID-19 levels. See “The Inclusive Development Index 2018: Summary and Data Highlights,” (Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2018), https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Forum_IncGrwth_2018.pdf .

Foreign Policy

Asia & the Pacific

Center for Asia Policy Studies

The Brookings Institution, Washington DC

10:00 am - 11:15 am EDT

Norman Eisen, Jonathan Katz, Robin J. Lewis

March 19, 2024

Norman Eisen, Fred Dews

March 14, 2024

For democracy to work, racial inequalities must be addressed, Stanford scholars say

The Stanford Center for Racial Justice is taking a hard look at the policies perpetuating systemic racism in America today and asking how we can imagine a more equitable society.

Last summer, a profound racial reckoning swept the United States and, to some extent, the world. The deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other Black Americans killed by the police, coupled with a pandemic disproportionately afflicting Black Americans, made the persistence of racism undeniable, says Stanford legal scholar Ralph Richard Banks .

Stanford Law Professor Ralph Richard Banks and Associate Dean for Public Service and Public Interest Law Diane Chin have established the Stanford Center for Racial Justice to address racial inequality and division in America. (Image credit: Courtesy Stanford Law School)

“It seems hard to argue against racial inequality in society. I think that has motivated people to want to do something and to ask, ‘Is this the society I want to live in?’ The question is, how long will people continue to have that sense of the urgency to do something?” said Banks, the Jackson Eli Reynolds Professor of Law at Stanford Law School (SLS).

That’s where the Stanford Center for Racial Justice (SCRJ) fits in. While situated within the law school, the aim of the SCRJ is to leverage the resources and capabilities of the broader university to further racial justice in ways that strengthen democracy.

Banks and Diane Chin , the associate dean for public service and public interest law and center’s acting director, launched the SCRJ in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement to help do the hard work of dismantling the policies and practices that perpetuate systemic racism and to identify solutions that could bring forth a more equitable world.

“Our goal is to create systems, policies, structures that ensure that racial barriers no longer persist,” Chin said, “and that each of us has a way to pursue and feel supported in pursuing the work that we want, living where we want, the schools we want for our children, healthcare access that is not racialized.”

Since the center launched in June 2020, Banks and Chin have been working tirelessly with faculty, students and outside organizations. To start, SCRJ is focusing on three areas where systemic change is urgently needed: criminal justice and policing, educational equity, and economic security and opportunity.

Some of those efforts are already underway.

This quarter, the SCRJ is working with the Graduate School of Education (GSE) to examine how to dismantle structural racism in the U.S. public school system and put an anti-racist education in its place. In a policy lab, The Youth Justice Lab: Imagining an Anti-Racist Public Education System, students from both the GSE and SLS are working with two nonprofit groups to develop specific policy and research interventions that can counter the racial disparities perpetuated by school programs, such as racially segregated academic placements (e.g. special education or advanced placement) and exclusionary school discipline policies.

Policy labs are a way for students to examine how such structures and systems can block or boost opportunity. In the practicums, students and their clients aim to craft new policies that policymakers can realistically roll out and fund because, as Chin observed, “That’s where the rubber hits the road. We can draft beautiful policies that are based on our values and our ideals – and that’s important – but they also have to be very practical to be implemented.”

Another recent policy lab explored at the intersection between law enforcement and race, specifically the role of policing in the local communities.

Last fall, students who took Selective De-Policing: Operationalizing Concrete Reforms (a collaboration with the Stanford Center for Criminal Justice) examined the various responsibilities of police, including their involvement in dealing with nonviolent issues, such as mental health, school discipline or homelessness. Students worked with the African American Mayors Association , a Washington D.C. organization that represents Black mayors across the country, to identify how cities might move some of their work away from armed, uninformed officers to other agencies and organizations that are better prepared to handle those situations in nonviolent ways. A report with their recommendations is set to publish later this year.

Tackling problems that transcend race

Because racial injustice crosscuts myriad problems in society, Banks said he hopes that the work the SCRJ does will also address issues that trouble people from all backgrounds and demographics.

“We’re using race to figure out how to address problems that transcend race. Racial injustices are emblematic of so many other problems we have,” he said.

Take policing for example, which Banks said is not working well for Black Americans nor for people of all races. “It raises questions about how we address not only crime but other problems like mental illness and homelessness because police officers have been used as a frontline for all these different problems.”

Banks acknowledges that it will take more than just a change in policy to inspire meaningful change; culture plays an important role too.

“The problems we confront are not problems that are going to be solved by the government alone,” said Banks. “The hardest thing, I think, is to recognize the ways that we are all implicated in the brokenness of our society.”

He added, “No matter how well-intentioned we are, we are all kind of the problem. The problems wouldn’t be as big as they are if we weren’t all contributing to them.”

Society cannot work without addressing the racial disparities that undermine the functioning of its democratic and social institutions, he added. “The challenge of racial justice is actually the challenge of democracy because we can’t make society work unless we can address racial division, distrust, inequality and racism.”

SCRJ is hosting periodic lectures over Zoom – titled “Tuesday Race Talks” – that are open to members of the public. The next event will be held Feb. 23 at 12:45 p.m. and will feature Steve Philips, a national political leader, civil rights lawyer and podcast host, who will talk on the state of Black politics.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

2 Is Inequality a Threat to Democracy?

- Published: October 2009

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Many believe that the government bears an active role and responsibility on how wealth and income are generated and distributed. With the rapid increase in income inequality in a number of the advanced democracies, it has now become a concern on whether or not this should be considered as a threat. This chapter first examines what types of equality brings concern to the people. An outline of a normative theory of legitimacy which roots regime legitimacy in the satisfaction of an “interest tracking” condition and a political theory suggesting how income inequality can weaken democratic rule is then given.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Democracy, Redistribution and Inequality

In this paper we revisit the relationship between democracy, redistribution and inequality. We first explain the theoretical reasons why democracy is expected to increase redistribution and reduce inequality, and why this expectation may fail to be realized when democracy is captured by the richer segments of the population; when it caters to the preferences of the middle class; or when it opens up disequalizing opportunities to segments of the population previously excluded from such activities, thus exacerbating inequality among a large part of the population. We then survey the existing empirical literature, which is both voluminous and full of contradictory results. We provide new and systematic reduced-form evidence on the dynamic impact of democracy on various outcomes. Our findings indicate that there is a significant and robust effect of democracy on tax revenues as a fraction of GDP, but no robust impact on inequality. We also find that democracy is associated with an increase in secondary schooling and a more rapid structural transformation. Finally, we provide some evidence suggesting that inequality tends to increase after democratization when the economy has already undergone significant structural transformation, when land inequality is high, and when the gap between the middle class and the poor is small. All of these are broadly consistent with a view that is different from the traditional median voter model of democratic redistribution: democracy does not lead to a uniform decline in post-tax inequality, but can result in changes in fiscal redistribution and economic structure that have ambiguous effects on inequality.

Prepared for the Handbook of Income Distribution edited by Anthony Atkinson and François Bourguignon. We are grateful to the editors for their detailed comments on an earlier draft and to participants in the Handbook conference in Paris, particularly to our discussant José-Víctor Ríos-Rull. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

Published Versions

Handbook of Income Distribution Volume 2, 2015, Pages 1885–1966 Handbook of Income Distribution Cover image Chapter 21 – Democracy, Redistribution, and Inequality Daron Acemoglu*, Suresh Naidu†, Pascual Restrepo*, James A. Robinson‡

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

Advertisement

Wealth inequality and democracy

- Published: 05 July 2023

- Volume 197 , pages 89–136, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Sutirtha Bagchi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0022-981X 1 &

- Matthew J. Fagerstrom 2

1110 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Scholars have studied the relationship between land inequality, income inequality, and democracy extensively, but have reached contradictory conclusions that have resulted from competing theories and methodologies. However, despite its importance, the effects of wealth inequality on democracy have not been examined empirically. We use a panel dataset of billionaire wealth from 1987 to 2012 to determine the impact of wealth inequality on the level of democracy. We measure democracy using Polity scores, Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) indices, and the continuous Machine Learning index. We find limited empirical support for the hypothesis that overall wealth inequality or inherited wealth inequality has an impact on democracy. However, we find evidence that politically connected wealth inequality lowers V-Dem and Machine Learning democracy scores. Following Boix (Democracy and redistribution, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2003), we investigate the hypothesis that capital mobility moderates the relationship between wealth inequality and democracy and find evidence that increased capital mobility mitigates the negative impact of politically connected wealth inequality on democracy.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Relationship Between Income Inequality and Economic Growth: Are Transmission Channels Effective?

The KOF Globalisation Index – revisited

Financial development and income inequality: a panel data approach.

Krieger and Meierrieks ( 2016 ) investigate the relationship between inequality and economic freedom, rather than democracy.

We have four groups of billionaires: self-made and politically unconnected (e.g. Bill Gates), self-made and politically connected (e.g. Russian oligarch, Roman Abramovich), inherited and politically unconnected (e.g. David Rockefeller), and inherited and politically connected (e.g. the sons of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri).

We could also consider the political agency of poor voters, who may prefer democracy if inequality is high if they think they can influence the choice of policies that will address inequality. Absent such a belief, they may not seek democracy, believing that it is ineffective in resolving inequality (Krieckhaus et al., 2014 ). Empirically, there is evidence that high levels of inequality depress voter turnout (Dash et al., 2023 ).

The use of continuous measures of democracy is important for this point; to the extent that fundamental rights to political participation are still present, we might see a decline in the quality of democracy without seeing a transition to outright autocracy.

For this result, we are using politically connected billionaire wealth as a share of GDP.

For a similar exposition of how a rising bourgeoisie class led to a push towards dismantling rent-seeking and demands for political participation in the case of Ancien Régime France, see Ekelund and Thornton ( 2020 ).

Tullock ( 1986 ) anticipates this point, noting that in the typical dictatorship or monarchy, it is common to find a great deal of rent seeking activity and the “granting of monopolies of one sort or another to friends of the ruler is very common and one of the major forms of enterprise is to ‘court’ the ruler in hopes of getting such special privileges.”

See also: https://www.nytimes.com/1993/10/01/business/worldbusiness/IHT-a-giant-joins-jakarta-exchange.html which describes the Indonesian business environment in the following dire terms: “All the really big conglomerates in Indonesia have strong political connections. That is how they get favorable contracts and concessions from the government and loans from state banks.”

These regime characteristics can also be redundant, which can artificially increase or decrease a country’s Polity score relative to a hypothetical “true” level of democracy.

On the other hand, many theories of the relationship between inequality and democracy posit that the links are between inequality and particular aspects of democracy, for instance, the ability of the poor to vote for redistribution. In this case, using broad measures of democracy may mask the “true” impact of inequality on democracy by mixing different concepts of democracy together (Knutsen & Dahlum, 2022 ).

More specifically, the Electoral Democracy index measures the foundational aspects of democracy, such as freedom of association and expression, voting rights, free and fair elections, and elections for the executive (Coppedge et al., 2022b ).

We find it important to note that the Egalitarian Democracy index is not mechanically related to our measure of wealth inequality. The egalitarian component of the index consists of three sub-indexes. The equal protection index measures the extent to which the law equally protects citizens across social groups and classes. The equal access index measures the de facto ability of all people to actively participate in government. The equal distribution of resources index measures how government welfare and infrastructure expenditures, education, and healthcare are distributed in society (Coppedge et al., 2022b ). No component of the Egalitarian Democracy index measures the distribution of privately owned assets or wealth.

V-Dem’s conceptualization of democracy is also narrower than Polity’s. It includes fewer components and hence is less likely to overlap with other institutional outcomes, such as the rule of law or corruption.

For the codebook and methodology, see Coppedge et al. ( 2022b , 2022c ).

Polity and V-Dem scores are generated using different processes. While Polity uses in-house experts that code all countries using country-specific reports, V-Dem uses observational data, expert surveys, and in-house experts (Skaaning, 2018 ).

Restrictions on suffrage or institutional rules that make voting onerous are one such potential mechanism. To the extent that increased voter turnout increases top marginal tax rates (Sabet, 2023 ) economic elites may have incentives to lobby for rules that make voting more difficult in order to protect their incomes.

Myanmar’s 2008 constitution provides a great example of this phenomenon. As Nehru ( 2015 ) notes, it included several provisions to ensure that the reins of power remained firmly in the hands of the military, chief among them being “Article 436 that gives the military one-quarter of the seats in the upper and lower houses of the national parliament and one-third of the seats in the state/regional parliaments. In addition, because constitutional amendments must receive more than 75 percent of the vote in parliament, the military’s mandated 25 percent presence gives it effective veto power over any proposed changes.”

Our results for overall wealth inequality are robust to dropping these countries.

Although we operationalize wealth inequality by normalizing billionaire wealth by GDP throughout the paper, we also present results obtained by normalizing billionaire wealth by population and the country’s capital stock in Online Appendix Tables A.7 and A.8.

A full classification of billionaires into the two categories of politically connected and politically unconnected is available from the authors on request.

https://www.forbes.com/billionaires2002/LIRKZ32.html .

https://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/moscow/potanin.html .

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1986/04/27/corruption-issue-could-cloud-suhartos-impressive-record/49e076d5-a764-464e-b314-1f212a06b352/ .

Fisman ( 2001 ) attempts to quantify the value of political connections and finds Indonesia to be especially fertile territory. It obtains estimates of the value of such connections by exploiting a string of rumors about President Suharto’s health during his last few years in office. The paper scores the companies affiliated with “longtime Suharto allies", the Salim Group run by Liem Sioe Liong and the Barito Pacific Group run by Prajogo Pangestu, as five on a scale of five—the highest score that it also assigns to companies associated with President Suharto’s children. Thus our classifications of Indonesian billionaires, while undertaken independently, are consistent with those in a very well-cited paper that examines political connections.

https://www.opensecrets.org/news/2020/10/adelsons-set-new-donation-record .

A higher rank on the Corruption Perceptions Index indicates that a country is perceived as being more corrupt by experts knowledgeable about the country. In the 2019 rankings by Transparency International, Denmark and New Zealand shared the 1st spot and were viewed as the least corrupt countries in the world whereas Yemen, Syria, South Sudan, and Somalia were perceived as the most corrupt countries in the world.

This list is calculated using the average of politically connected wealth inequality in years where these countries had at least one billionaire. These results are comparable to those found in Bagchi and Svejnar ( 2015 ) (refer Table A2, p. 528).

Furthermore, in a univariate regression between politically connected wealth as a share of GDP and either the proportion of firms that are politically connected or the fraction of market capitalization represented by politically connected firms, the regression coefficients are significant at the 5% level (or higher) and additionally, the values of R-squared, with just a single variable included, exceed 0.40. Those additional regressions provide further assurance that our measure of politically connected wealth inequality is reasonable as it lines up well with measures in Faccio ( 2006 )—a well-cited paper that arrives at political connections using an entirely different approach.

We note though that in many constitutional monarchies, the monarch or other royals are often legally unable to put the institutional wealth of the crown for personal use. For example, in the United Kingdom the Crown Estate manages the property of the King but they note that "it is not the private property of the monarch —it cannot be sold by the monarch, nor do revenues from it belong to the monarch."

The Kernel Density of KAOPEN can be found in the bottom panel of Fig. 2 .

The choice of 1996 is motivated by a change in the way Forbes covered billionaire wealth in 1997. As Bagchi and Svejnar ( 2015 ) explains: “ Forbes magazine changed its editorial policy for four years, between 1997 and 2000. In these years, they included only those billionaires who were either self-made (e.g., Warren Buffett) or those who inherited their wealth and were actively managing it themselves (e.g., Carlos Slim Helu of Mexico). This leads to the exclusion of billionaires from around the world who simply inherited their wealth and were no longer actively involved themselves in growing their businesses, such as the duPonts and Rockefellers in the U.S. [...] Given this limitation of the 1997 list, we use the 1996 list instead." Because we are interested in how inherited wealth inequality impacts democracy, it is important that we include all inherited billionaires and not just those who are actively managing their fortunes.

As can be seen from Online Appendix Table A.2, our results are robust to dropping such countries.

Section 1 in the Online Appendix lists all of the controls, including their justification for inclusion.

However, we also confirm that all our results are robust to the use of random effects specifications.

These null results hold when we limit our sample to only those countries that have had billionaires at least once. See Online Appendix Table A.1.

A 5.5 percentage point increase in wealth inequality implies a decline in V-Dem scores of \(5.5*(-0.00391+(0.00899*0.166)) = -0.0133\) points. A decline in V-Dem scores of 0.031 points implies that \(0.0133/0.031 = 0.43\) , or 43 percent of the decline in V-Dem scores can be explained by politically connected wealth inequality.

We use Polity as our threshold for sample selection because although the translation from a continuous to a dichotomous measure of democracy is ad-hoc (Gründler & Krieger, 2022 ) we want to base our sample selection on a democracy measure which is not related to our inequality measure. We replicate these results using the dichotomous Machine Learning index in Online Appendix Table A.4.

Over that same time period, overall billionaire wealth in South Africa increased from 2.79 to 4.07 percent of GDP.

In additional checks not included in the paper, we confirm that our baseline results in Table 3 survive the introduction of each measure of wealth inequality or income inequality from the WID, such as the top percentile wealth share, the top decile wealth share, the Gini coefficient of wealth, etc. as controls.

See Online Appendix Tables A.9 and A.10 for overall, A.11 and A.12 for inherited, and A.13 and A.14 for politically connected wealth inequality results. Table A.15 shows that the results for politically connected wealth inequality hold for democracies as well.

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy does cause growth. Journal of Political Economy, 127 (1), 47–100.

Article Google Scholar

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2006). Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Ahlquist, J. S., & Wibbels, E. (2012). Riding the wave: World trade and factor-based models of democratization. American Journal of Political Science, 56 (2), 447–464.

Albertus, M., & Menaldo, V. (2018). Authoritarianism and the elite origins of democracy . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ansell, B., & Samuels, D. (2010). Inequality and democratization: A contractarian approach. Comparative Political Studies, 43 (12), 1543–1574.

Bagchi, S., Curran, M., & Fagerstrom, M. J. (2019). Monetary growth and wealth inequality. Economics Letters, 182 , 23–25.

Bagchi, S., & Svejnar, J. (2015). Does wealth inequality matter for growth? The effect of billionaire wealth, income distribution, and poverty. Journal of Comparative Economics, 43 (3), 505–530.

Bagchi, S. & Svejnar, J. (2016). Inequality and growth: Patterns and policy , chapter Does Wealth Distribution and the Source of Wealth Matter for Economic Growth? Inherited v. Uninherited Billionaire Wealth and Billionaires’ Political Connections, pp. 163–194. Palgrave Macmillan, UK.

Baltagi, B. H., Demetriades, P. O., & Law, S. H. (2009). Financial development and openness: Evidence from panel data. Journal of Development Economics, 89 (2), 285–296.

Bernhard, M., Reenock, C., & Nordstrom, T. (2004). The legacy of western overseas colonialism on democratic survival. International Studies Quarterly, 48 (1), 225–250.

Black, B. S., Kraakman, R., & Tarassova, A. (2000). Russian privatization and corporate governance: What went wrong? Stanford Law Review, 52 (6), 1731–1808.

Boix, C. (2003). Democracy and redistribution . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Buchanan, J. M., & Congleton, R. D. (1998). Politics by principle, not interest: Towards nondiscriminatory democracy . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Buchanan, J. M. & Tullock, G. (1999). The calculus of consent . Liberty Fund.

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2010). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143 , 67–101.

Chinn, M. D., & Ito, H. (2006). What matters for financial development? Capital controls, institutions, and interactions. Journal of Development Economics, 81 (1), 163–192.

Coppedge, M., Edgell, A. B., Knutsen, C. H., & Lindberg, S. I. (2022a). Why democracies develop and decline , chapter V-dem reconsiders democratization, pp. 1–28. Cambridge University Press.

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Cornell, A., Fish, M. S., Gastaldi, L., Gjerløw, H., Glynn, A., Grahn, S., Hicken, A., Kinzelbach, K., Marquardt, K. L., McMann, K., Mechkova, V., Paxton, P., Pemstein, D., von Römer, J., Seim, B., Sigman, R., Skaaning, S.-E., Staton, J., Tzelgov, E., Uberti, L., ting Wang, Y., Wig, T., & Ziblatt, D. (2022b). V-Dem Codebook v12. Varieties of democracy (V-Dem) project .

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Marquardt, K. L., Medzihorsky, J., Pemstein, D., Alizada, N., Gastaldi, L., Hindle, G., Pernes, J., von Römer, J., Tzelgov, E., ting Wang, Y., & Wilson, S. (2022c). V-dem methodology v12. Varieties of democracy (V-Dem) project .

Dahl, R. A. (1972). Polyarchy: Participation and opposition . Yale University Press.

Dash, B. B., Ferris, J. S., & Voia, M.-C. (2023). Inequality, transaction costs and voter turnout: Evidence from Canadian provinces and Indian states. Public Choice, 194 , 325–346.

Diamond, L. (2015). Facing up to the democratic recession. Journal of Democracy, 26 (1), 141–155.

Easterly, W. (2007). Inequality does cause underdevelopment: Insights from a new instrument. Journal of Development Economics, 84 (2), 755–776.

Ekelund, R. B., & Thornton, M. (2020). Rent seeking as an evolving process: The case of the Ancien Régime. Public Choice, 182 , 139–155.

Faccio, M. (2006). Politically connected firms. American Economic Review, 96 (1), 369–386.

Fisman, R. (2001). Estimating the value of political connections. American Economic Review, 91 (4), 1095–1102.

Foa, R. S., & Mounk, Y. (2016). The danger of deconsolidation: The democratic disconnect. Journal of Democracy, 27 (3), 5–17.

Gorodnichenko, Y., & Roland, G. (2021). Culture, institutions and democratization. Public Choice, 187 , 165–195.

Gründler, K., & Krieger, T. (2021). Using machine learning for measuring democracy: A practicioners guide and a new updated dataset for 186 Countries from 1919 to 2019. European Journal of Political Economy , 70.

Gründler, K. & Krieger, T. (2022). Should we care (more) about data aggregation? European Economic Review , 142.

Holcombe, R. G. (2018). Political capitalism: How economic and political power is made and maintained . Cambridge University Press.

Houle, C. (2009). Inequality and democracy: Why inequality harms consolidation but does not affect democratization. World Politics, 61 (4), 589–622.

Houle, C. (2016). Inequality, economic development, and democratization. Studies in Comparative International Development, 51 (4), 503–529.

Houle, C. (2019). Social mobility and political instability. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63 (1), 85–111.

Husted, T. A., & Kenny, L. W. (1997). The effect of the expansion of the voting franchise on the size of government. Journal of Political Economy, 105 (1), 54–82.

Högström, J. (2013). Does the choice of democracy measure matter? Comparisons between the two leading democracy indices, Freedom House and Polity IV. Government and Opposition, 48 (2), 201–221.

Ilzetzki, E., Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2019). Exchange arrangements entering the twenty-first century: Which anchor will hold? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134 (2), 599–646.

Islam, M. N., & Winer, S. L. (2004). Tinpots, totalitarians (and democrats): An empirical investigation of the effects of economic growth on civil liberties and political rights. Public Choice, 118 (3/4), 289–323.

Islam, M. R., & McGillivray, M. (2020). Wealth inequality, governance and economic growth. Economic Modelling, 88 , 1–13.

Kaufman, R. R. (2009). The political effects of inequality in Latin America: Some inconvenient facts. Comparative Politics, 41 (3), 359–379.

Knutsen, C. H. & Dahlum, S. (2022). Why democracies develop and decline , chapter Economic Determinants, pp. 119–160. Cambridge University Press.

Krieckhaus, J., Byunghwan, S., Bellinger, N. M., & Wells, J. M. (2014). Economic inequality and democratic support. The Journal of Politics, 76 (1), 139–151.

Krieger, T., & Meierrieks, D. (2016). Political capitalism: The interaction between income inequality, economic freedom and democracy. European Journal of Political Economy, 45 , 115–132.

Lambsdorff, J. G. (2002). Corruption and rent-seeking. Public Choice, 113 , 97–125.

Leeson, P. T. (2005). Endogenizing fractionalization. Journal of Institutional Economics, 1 (1), 75–98.

Leeson, P. T., & Dean, A. M. (2009). The democratic domino theory: An empirical investigation. American Journal of Political Science, 53 (3), 533–551.

Lührmann, A., & Lindberg, S. I. (2019). A third wave of autocratization is here: What is new about it? Democratization, 26 (7), 1095–1113.

Marshall, M. G., Gurr, T. R., & Jaggers, K. (2017). Polity IV project dataset users’ manual . Center for Systemic Peace.

Meltzer, A. H., & Richard, S. F. (1981). A rational theory of the size of government. Journal of Political Economy, 89 (5), 914–927.

Midlarsky, M. I. (1992). The origins of democracy in agrarian society: Land inequality and political rights. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 36 (3), 454–477.

Miller, M. (2023). Who values democracy? Working paper . https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3488208 .

Mizuno, N., Naito, K., & Okazawa, R. (2017). Inequality, extractive institutions, and growth in nondemocratic regimes. Public Choice, 170 (1–2), 115–142.

Mounk, Y. (2018). The People vs. Democracy: Why our freedom is in danger and how to save it . Harvard University Press.

Muller, E. N. (1995). Economic determinants of democracy. American Sociological Review, 60 (6), 966–982.

Nehru, V. (2015). Myanmar’s military keeps firm grip on democratic transition. In Carnegie endowment for international piece working paper .

Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica, 49 (6), 1417–1426.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century . Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

Policardo, L., & Carrera, E. J. S. (2020). Can income inequality promote democratization? Metroeconomica, 71 (3), 510–532.

Ross, M. (2001). Does oil hinder democracy. World Politics, 53 (3), 325–361.

Rowley, C. K., & Smith, N. (2009). Islam’s democracy paradox: Muslims claim to like democracy, so why do they have so little? Public Choice, 139 (3/4), 273–299.

Rød, E. G., Knutsen, C. H., & Hegre, H. (2020). The determinants of democracy: A sensitivity analysis. Public Choice, 185 , 87–111.

Sabet, N. (2023). Turning out for redistribution: The effect of voter turnout on top marginal tax rates. Public Choice, 194 , 347–367.

Skaaning, S.-E. (2018). Different types of data and the validity of democracy measures. Politics and Governance, 6 (1), 105–116.

Treisman, D. (2020). Economic development and democracy: Predispositions and triggers. Annual Review of Political Science, 23 (1), 241–257.

Tullock, G. (1986). Industrial organization and rent seeking in dictatorships. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 142 (1), 4–15.

Vaccaro, A. (2021). Comparing measures of democracy: Statistical properties, convergence, and interchangeability. European Political Science, 20 , 666–684.

Wintrobe, R. (1990). The Tinpot and the totalitarian: An economic theory of dictatorship. The American Political Science Review, 84 (3), 849–872.

Woodberry, R. (2012). The missionary roots of liberal democracy. American Political Science Review, 106 (2), 244–274.

Ziblatt, D. (2008). Does landholding inequality block democratization?: A test of the “Bread and Democracy’’ thesis and the case of Prussia. World Politics, 60 (4), 610–641.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Peter Calcagno, Joshua Hall, Christopher Kilby, Laura Meinzen-Dick, Olukunle Owolabi, Daniel Treisman, two anonymous referees, and participants at a session of the 2019 National Tax Association Conference for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Villanova University, Villanova, PA, USA

Sutirtha Bagchi

The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Matthew J. Fagerstrom

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sutirtha Bagchi .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file 1 (pdf 283 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article