- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Presentations

How to Write a Seminar Paper

Last Updated: October 17, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 16 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 628,537 times.

A seminar paper is a work of original research that presents a specific thesis and is presented to a group of interested peers, usually in an academic setting. For example, it might serve as your cumulative assignment in a university course. Although seminar papers have specific purposes and guidelines in some places, such as law school, the general process and format is the same. The steps below will guide you through the research and writing process of how to write a seminar paper and provide tips for developing a well-received paper.

Getting Started

- an argument that makes an original contribution to the existing scholarship on your subject

- extensive research that supports your argument

- extensive footnotes or endnotes (depending on the documentation style you are using)

- Make sure that you understand how to cite your sources for the paper and how to use the documentation style your professor prefers, such as APA , MLA , or Chicago Style .

- Don’t feel bad if you have questions. It is better to ask and make sure that you understand than to do the assignment wrong and get a bad grade.

- Since it's best to break down a seminar paper into individual steps, creating a schedule is a good idea. You can adjust your schedule as needed.

- Do not attempt to research and write a seminar in just a few days. This type of paper requires extensive research, so you will need to plan ahead. Get started as early as possible. [3] X Research source

- Listing List all of the ideas that you have for your essay (good or bad) and then look over the list you have made and group similar ideas together. Expand those lists by adding more ideas or by using another prewriting activity. [5] X Research source

- Freewriting Write nonstop for about 10 minutes. Write whatever comes to mind and don’t edit yourself. When you are done, review what you have written and highlight or underline the most useful information. Repeat the freewriting exercise using the passages you underlined as a starting point. You can repeat this exercise multiple times to continue to refine and develop your ideas. [6] X Research source

- Clustering Write a brief explanation (phrase or short sentence) of the subject of your seminar paper on the center of a piece of paper and circle it. Then draw three or more lines extending from the circle. Write a corresponding idea at the end of each of these lines. Continue developing your cluster until you have explored as many connections as you can. [7] X Research source

- Questioning On a piece of paper, write out “Who? What? When? Where? Why? How?” Space the questions about two or three lines apart on the paper so that you can write your answers on these lines. Respond to each question in as much detail as you can. [8] X Research source

- For example, if you wanted to know more about the uses of religious relics in medieval England, you might start with something like “How were relics used in medieval England?” The information that you gather on this subject might lead you to develop a thesis about the role or importance of relics in medieval England.

- Keep your research question simple and focused. Use your research question to narrow your research. Once you start to gather information, it's okay to revise or tweak your research question to match the information you find. Similarly, you can always narrow your question a bit if you are turning up too much information.

Conducting Research

- Use your library’s databases, such as EBSCO or JSTOR, rather than a general internet search. University libraries subscribe to many databases. These databases provide you with free access to articles and other resources that you cannot usually gain access to by using a search engine. If you don't have access to these databases, you can try Google Scholar.

- Publication's credentials Consider the type of source, such as a peer-reviewed journal or book. Look for sources that are academically based and accepted by the research community. Additionally, your sources should be unbiased.

- Author's credentials Choose sources that include an author’s name and that provide credentials for that author. The credentials should indicate something about why this person is qualified to speak as an authority on the subject. For example, an article about a medical condition will be more trustworthy if the author is a medical doctor. If you find a source where no author is listed or the author does not have any credentials, then this source may not be trustworthy. [12] X Research source

- Citations Think about whether or not this author has adequately researched the topic. Check the author’s bibliography or works cited page. If the author has provided few or no sources, then this source may not be trustworthy. [13] X Research source

- Bias Think about whether or not this author has presented an objective, well-reasoned account of the topic. How often does the tone indicate a strong preference for one side of the argument? How often does the argument dismiss or disregard the opposition’s concerns or valid arguments? If these are regular occurrences in the source, then it may not be a good choice. [14] X Research source

- Publication date Think about whether or not this source presents the most up to date information on the subject. Noting the publication date is especially important for scientific subjects, since new technologies and techniques have made some earlier findings irrelevant. [15] X Research source

- Information provided in the source If you are still questioning the trustworthiness of this source, cross check some of the information provided against a trustworthy source. If the information that this author presents contradicts one of your trustworthy sources, then it might not be a good source to use in your paper.

- Give yourself plenty of time to read your sources and work to understand what they are saying. Ask your professor for clarification if something is unclear to you.

- Consider if it's easier for you to read and annotate your sources digitally or if you'd prefer to print them out and annotate by hand.

- Be careful to properly cite your sources when taking notes. Even accidental plagiarism may result in a failing grade on a paper.

Drafting Your Paper

- Make sure that your thesis presents an original point of view. Since seminar papers are advanced writing projects, be certain that your thesis presents a perspective that is advanced and original. [18] X Research source

- For example, if you conducted your research on the uses of relics in medieval England, your thesis might be, “Medieval English religious relics were often used in ways that are more pagan than Christian.”

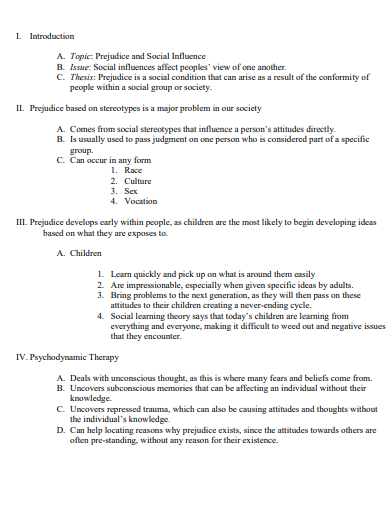

- Organize your outline by essay part and then break those parts into subsections. For example, part 1 might be your introduction, which could then be broken into three sub-parts: a)opening sentence, b)context/background information c)thesis statement.

- For example, in a paper about medieval relics, you might open with a surprising example of how relics were used or a vivid description of an unusual relic.

- Keep in mind that your introduction should identify the main idea of your seminar paper and act as a preview to the rest of your paper.

- For example, in a paper about relics in medieval England, you might want to offer your readers examples of the types of relics and how they were used. What purpose did they serve? Where were they kept? Who was allowed to have relics? Why did people value relics?

- Keep in mind that your background information should be used to help your readers understand your point of view.

- Remember to use topic sentences to structure your paragraphs. Provide a claim at the beginning of each paragraph. Then, support your claim with at least one example from one of your sources. Remember to discuss each piece of evidence in detail so that your readers will understand the point that you are trying to make.

- For example, in a paper on medieval relics, you might include a heading titled “Uses of Relics” and subheadings titled “Religious Uses”, “Domestic Uses”, “Medical Uses”, etc.

- Synthesize what you have discussed . Put everything together for your readers and explain what other lessons might be gained from your argument. How might this discussion change the way others view your subject?

- Explain why your topic matters . Help your readers to see why this topic deserve their attention. How does this topic affect your readers? What are the broader implications of this topic? Why does your topic matter?

- Return to your opening discussion. If you offered an anecdote or a quote early in your paper, it might be helpful to revisit that opening discussion and explore how the information you have gathered implicates that discussion.

- Ask your professor what documentation style he or she prefers that you use if you are not sure.

- Visit your school’s writing center for additional help with your works cited page and in-text citations.

Revising Your Paper

- What is your main point? How might you clarify your main point?

- Who is your audience? Have you considered their needs and expectations?

- What is your purpose? Have you accomplished your purpose with this paper?

- How effective is your evidence? How might your strengthen your evidence?

- Does every part of your paper relate back to your thesis? How might you improve these connections?

- Is anything confusing about your language or organization? How might your clarify your language or organization?

- Have you made any errors with grammar, punctuation, or spelling? How can you correct these errors?

- What might someone who disagrees with you say about your paper? How can you address these opposing arguments in your paper? [26] X Research source

Features of Seminar Papers and Sample Thesis Statements

Community Q&A

- Keep in mind that seminar papers differ by discipline. Although most seminar papers share certain features, your discipline may have some requirements or features that are unique. For example, a seminar paper written for a Chemistry course may require you to include original data from your experiments, whereas a seminar paper for an English course may require you to include a literature review. Check with your student handbook or check with your advisor to find out about special features for seminar papers in your program. Make sure that you ask your professor about his/her expectations before you get started as well. [27] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- When coming up with a specific thesis, begin by arguing something broad and then gradually grow more specific in the points you want to argue. Thanks Helpful 23 Not Helpful 11

- Choose a topic that interests you, rather than something that seems like it will interest others. It is much easier and more enjoyable to write about something you care about. Thanks Helpful 6 Not Helpful 1

- Do not be afraid to admit any shortcomings or difficulties with your argument. Your thesis will be made stronger if you openly identify unresolved or problematic areas rather than glossing over them. Thanks Helpful 13 Not Helpful 6

- Plagiarism is a serious offense in the academic world. If you plagiarize your paper you may fail the assignment and even the course altogether. Make sure that you fully understand what is and is not considered plagiarism before you write your paper. Ask your teacher if you have any concerns or questions about your school’s plagiarism policy. Thanks Helpful 7 Not Helpful 2

You Might Also Like

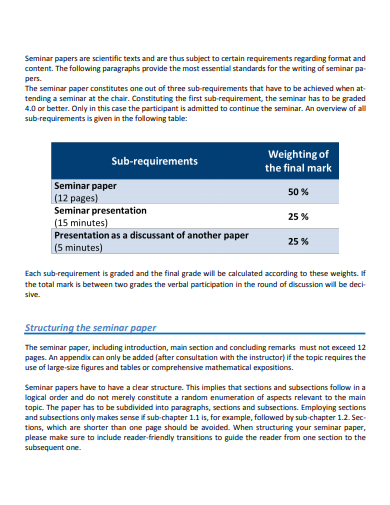

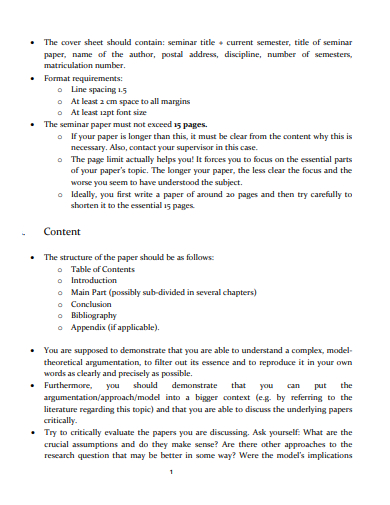

- ↑ https://umweltoekonomie.uni-hohenheim.de/fileadmin/einrichtungen/umweltoekonomie/1-Studium_Lehre/Materialien_und_Informationen/Guidelines_Seminar_Paper_NEW_14.10.15.pdf

- ↑ https://www.bestcolleges.com/blog/how-to-ask-professor-feedback/

- ↑ http://www.law.georgetown.edu/library/research/guides/seminar_papers.cfm

- ↑ https://www.stcloudstate.edu/writeplace/_files/documents/writing%20process/choosing-and-narrowing-an-essay-topic.pdf

- ↑ http://writing.ku.edu/prewriting-strategies

- ↑ http://www.kuwi.europa-uni.de/en/lehrstuhl/vs/politik3/Hinweise_Seminararbeiten/haenglish.html

- ↑ https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/faq/reliable

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/673/1/

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/thesis-statements/

- ↑ https://www.irsc.edu/students/academicsupportcenter/researchpaper/researchpaper.aspx?id=4294967433

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/engagement/2/2/58/

- ↑ http://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/beginning-academic-essay

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/589/02/

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/561/05/

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/ReverseOutlines.html

About This Article

To write a seminar paper, start by writing a clear and specific thesis that expresses your original point of view. Then, work on your introduction, which should give your readers relevant context about your topic and present your argument in a logical way. As you write, break up the body of your paper with headings and sub-headings that categorize each section of your paper. This will help readers follow your argument. Conclude your paper by synthesizing your argument and explaining why this topic matters. Be sure to cite all the sources you used in a bibliography. For advice on getting started on your seminar paper, keep reading. Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Patrick Topf

Jul 4, 2017

Did this article help you?

Flora Ballot

Oct 10, 2016

Igwe Uchenna

Jul 19, 2017

Saudiya Kassim Aliyu

Oct 11, 2018

Susan Wyman

Mar 29, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

Home Blog Presentation Ideas How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

Every research endeavor ends up with the communication of its findings. Graduate-level research culminates in a thesis defense , while many academic and scientific disciplines are published in peer-reviewed journals. In a business context, PowerPoint research presentation is the default format for reporting the findings to stakeholders.

Condensing months of work into a few slides can prove to be challenging. It requires particular skills to create and deliver a research presentation that promotes informed decisions and drives long-term projects forward.

Table of Contents

What is a Research Presentation

Key slides for creating a research presentation, tips when delivering a research presentation, how to present sources in a research presentation, recommended templates to create a research presentation.

A research presentation is the communication of research findings, typically delivered to an audience of peers, colleagues, students, or professionals. In the academe, it is meant to showcase the importance of the research paper , state the findings and the analysis of those findings, and seek feedback that could further the research.

The presentation of research becomes even more critical in the business world as the insights derived from it are the basis of strategic decisions of organizations. Information from this type of report can aid companies in maximizing the sales and profit of their business. Major projects such as research and development (R&D) in a new field, the launch of a new product or service, or even corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives will require the presentation of research findings to prove their feasibility.

Market research and technical research are examples of business-type research presentations you will commonly encounter.

In this article, we’ve compiled all the essential tips, including some examples and templates, to get you started with creating and delivering a stellar research presentation tailored specifically for the business context.

Various research suggests that the average attention span of adults during presentations is around 20 minutes, with a notable drop in an engagement at the 10-minute mark . Beyond that, you might see your audience doing other things.

How can you avoid such a mistake? The answer lies in the adage “keep it simple, stupid” or KISS. We don’t mean dumbing down your content but rather presenting it in a way that is easily digestible and accessible to your audience. One way you can do this is by organizing your research presentation using a clear structure.

Here are the slides you should prioritize when creating your research presentation PowerPoint.

1. Title Page

The title page is the first thing your audience will see during your presentation, so put extra effort into it to make an impression. Of course, writing presentation titles and title pages will vary depending on the type of presentation you are to deliver. In the case of a research presentation, you want a formal and academic-sounding one. It should include:

- The full title of the report

- The date of the report

- The name of the researchers or department in charge of the report

- The name of the organization for which the presentation is intended

When writing the title of your research presentation, it should reflect the topic and objective of the report. Focus only on the subject and avoid adding redundant phrases like “A research on” or “A study on.” However, you may use phrases like “Market Analysis” or “Feasibility Study” because they help identify the purpose of the presentation. Doing so also serves a long-term purpose for the filing and later retrieving of the document.

Here’s a sample title page for a hypothetical market research presentation from Gillette .

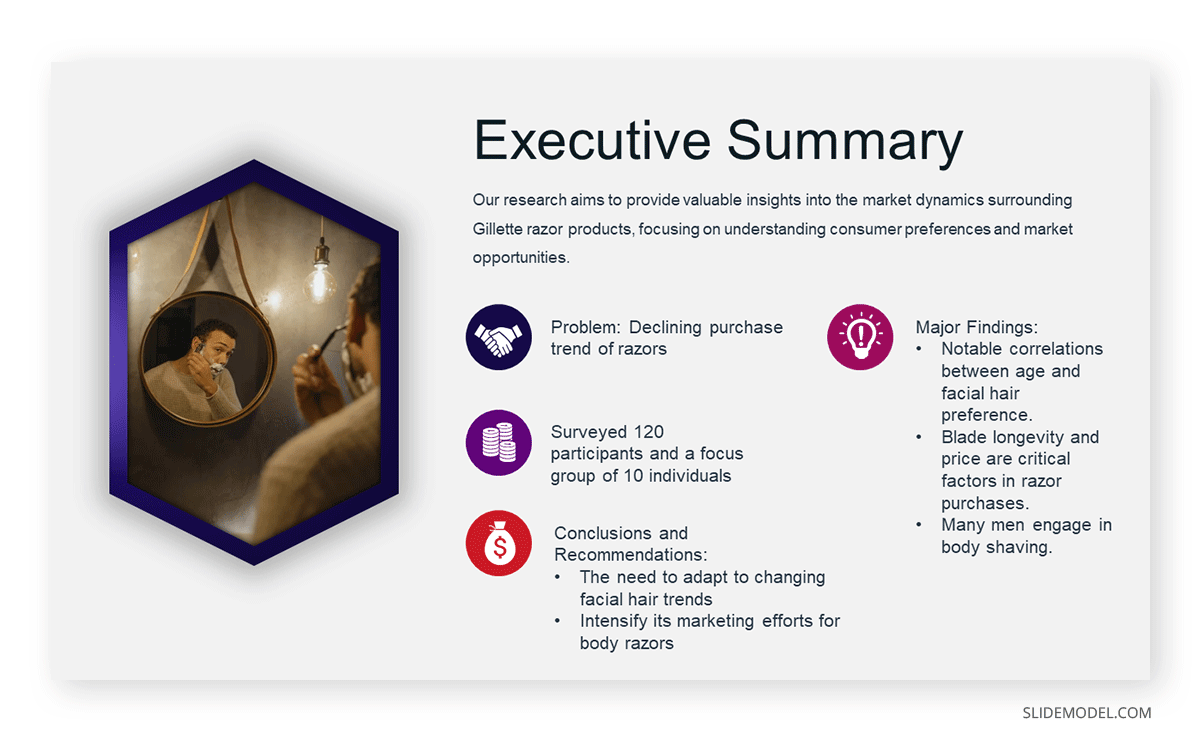

2. Executive Summary Slide

The executive summary marks the beginning of the body of the presentation, briefly summarizing the key discussion points of the research. Specifically, the summary may state the following:

- The purpose of the investigation and its significance within the organization’s goals

- The methods used for the investigation

- The major findings of the investigation

- The conclusions and recommendations after the investigation

Although the executive summary encompasses the entry of the research presentation, it should not dive into all the details of the work on which the findings, conclusions, and recommendations were based. Creating the executive summary requires a focus on clarity and brevity, especially when translating it to a PowerPoint document where space is limited.

Each point should be presented in a clear and visually engaging manner to capture the audience’s attention and set the stage for the rest of the presentation. Use visuals, bullet points, and minimal text to convey information efficiently.

3. Introduction/ Project Description Slides

In this section, your goal is to provide your audience with the information that will help them understand the details of the presentation. Provide a detailed description of the project, including its goals, objectives, scope, and methods for gathering and analyzing data.

You want to answer these fundamental questions:

- What specific questions are you trying to answer, problems you aim to solve, or opportunities you seek to explore?

- Why is this project important, and what prompted it?

- What are the boundaries of your research or initiative?

- How were the data gathered?

Important: The introduction should exclude specific findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

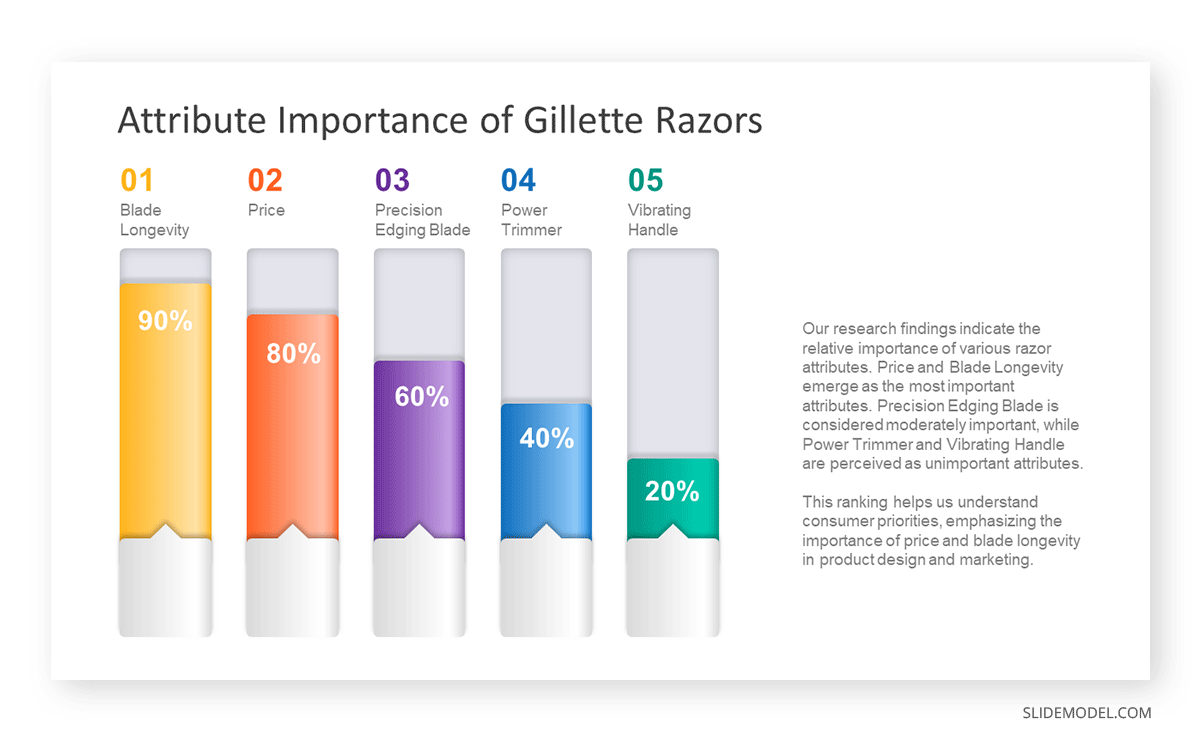

4. Data Presentation and Analyses Slides

This is the longest section of a research presentation, as you’ll present the data you’ve gathered and provide a thorough analysis of that data to draw meaningful conclusions. The format and components of this section can vary widely, tailored to the specific nature of your research.

For example, if you are doing market research, you may include the market potential estimate, competitor analysis, and pricing analysis. These elements will help your organization determine the actual viability of a market opportunity.

Visual aids like charts, graphs, tables, and diagrams are potent tools to convey your key findings effectively. These materials may be numbered and sequenced (Figure 1, Figure 2, and so forth), accompanied by text to make sense of the insights.

5. Conclusions

The conclusion of a research presentation is where you pull together the ideas derived from your data presentation and analyses in light of the purpose of the research. For example, if the objective is to assess the market of a new product, the conclusion should determine the requirements of the market in question and tell whether there is a product-market fit.

Designing your conclusion slide should be straightforward and focused on conveying the key takeaways from your research. Keep the text concise and to the point. Present it in bullet points or numbered lists to make the content easily scannable.

6. Recommendations

The findings of your research might reveal elements that may not align with your initial vision or expectations. These deviations are addressed in the recommendations section of your presentation, which outlines the best course of action based on the result of the research.

What emerging markets should we target next? Do we need to rethink our pricing strategies? Which professionals should we hire for this special project? — these are some of the questions that may arise when coming up with this part of the research.

Recommendations may be combined with the conclusion, but presenting them separately to reinforce their urgency. In the end, the decision-makers in the organization or your clients will make the final call on whether to accept or decline the recommendations.

7. Questions Slide

Members of your audience are not involved in carrying out your research activity, which means there’s a lot they don’t know about its details. By offering an opportunity for questions, you can invite them to bridge that gap, seek clarification, and engage in a dialogue that enhances their understanding.

If your research is more business-oriented, facilitating a question and answer after your presentation becomes imperative as it’s your final appeal to encourage buy-in for your recommendations.

A simple “Ask us anything” slide can indicate that you are ready to accept questions.

1. Focus on the Most Important Findings

The truth about presenting research findings is that your audience doesn’t need to know everything. Instead, they should receive a distilled, clear, and meaningful overview that focuses on the most critical aspects.

You will likely have to squeeze in the oral presentation of your research into a 10 to 20-minute presentation, so you have to make the most out of the time given to you. In the presentation, don’t soak in the less important elements like historical backgrounds. Decision-makers might even ask you to skip these portions and focus on sharing the findings.

2. Do Not Read Word-per-word

Reading word-for-word from your presentation slides intensifies the danger of losing your audience’s interest. Its effect can be detrimental, especially if the purpose of your research presentation is to gain approval from the audience. So, how can you avoid this mistake?

- Make a conscious design decision to keep the text on your slides minimal. Your slides should serve as visual cues to guide your presentation.

- Structure your presentation as a narrative or story. Stories are more engaging and memorable than dry, factual information.

- Prepare speaker notes with the key points of your research. Glance at it when needed.

- Engage with the audience by maintaining eye contact and asking rhetorical questions.

3. Don’t Go Without Handouts

Handouts are paper copies of your presentation slides that you distribute to your audience. They typically contain the summary of your key points, but they may also provide supplementary information supporting data presented through tables and graphs.

The purpose of distributing presentation handouts is to easily retain the key points you presented as they become good references in the future. Distributing handouts in advance allows your audience to review the material and come prepared with questions or points for discussion during the presentation.

4. Actively Listen

An equally important skill that a presenter must possess aside from speaking is the ability to listen. We are not just talking about listening to what the audience is saying but also considering their reactions and nonverbal cues. If you sense disinterest or confusion, you can adapt your approach on the fly to re-engage them.

For example, if some members of your audience are exchanging glances, they may be skeptical of the research findings you are presenting. This is the best time to reassure them of the validity of your data and provide a concise overview of how it came to be. You may also encourage them to seek clarification.

5. Be Confident

Anxiety can strike before a presentation – it’s a common reaction whenever someone has to speak in front of others. If you can’t eliminate your stress, try to manage it.

People hate public speaking not because they simply hate it. Most of the time, it arises from one’s belief in themselves. You don’t have to take our word for it. Take Maslow’s theory that says a threat to one’s self-esteem is a source of distress among an individual.

Now, how can you master this feeling? You’ve spent a lot of time on your research, so there is no question about your topic knowledge. Perhaps you just need to rehearse your research presentation. If you know what you will say and how to say it, you will gain confidence in presenting your work.

All sources you use in creating your research presentation should be given proper credit. The APA Style is the most widely used citation style in formal research.

In-text citation

Add references within the text of your presentation slide by giving the author’s last name, year of publication, and page number (if applicable) in parentheses after direct quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

The alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (Smith, 2020, p. 27).

If the author’s name and year of publication are mentioned in the text, add only the page number in parentheses after the quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

According to Smith (2020), the alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (p. 27).

Image citation

All images from the web, including photos, graphs, and tables, used in your slides should be credited using the format below.

Creator’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Image.” Website Name, Day Mo. Year, URL. Accessed Day Mo. Year.

Work cited page

A work cited page or reference list should follow after the last slide of your presentation. The list should be alphabetized by the author’s last name and initials followed by the year of publication, the title of the book or article, the place of publication, and the publisher. As in:

Smith, J. A. (2020). Climate Change and Biodiversity: A Comprehensive Study. New York, NY: ABC Publications.

When citing a document from a website, add the source URL after the title of the book or article instead of the place of publication and the publisher. As in:

Smith, J. A. (2020). Climate Change and Biodiversity: A Comprehensive Study. Retrieved from https://www.smith.com/climate-change-and-biodiversity.

1. Research Project Presentation PowerPoint Template

A slide deck containing 18 different slides intended to take off the weight of how to make a research presentation. With tons of visual aids, presenters can reference existing research on similar projects to this one – or link another research presentation example – provide an accurate data analysis, disclose the methodology used, and much more.

Use This Template

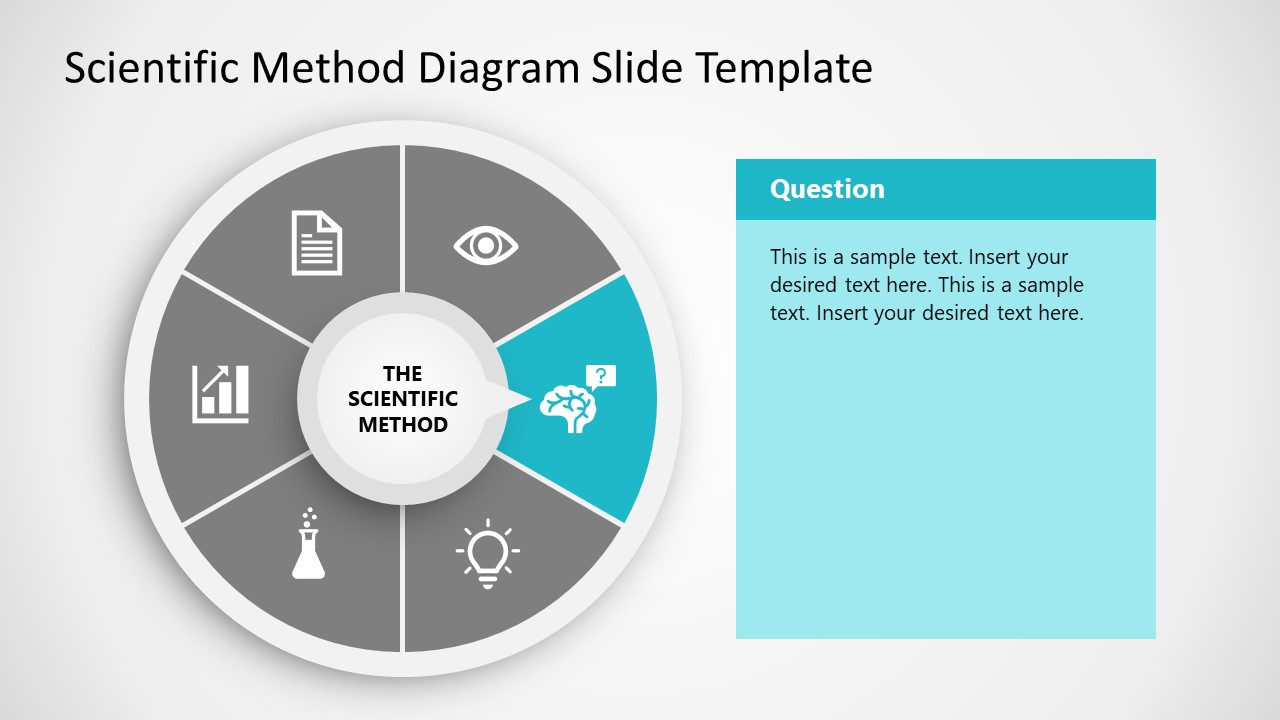

2. Research Presentation Scientific Method Diagram PowerPoint Template

Whenever you intend to raise questions, expose the methodology you used for your research, or even suggest a scientific method approach for future analysis, this circular wheel diagram is a perfect fit for any presentation study.

Customize all of its elements to suit the demands of your presentation in just minutes.

3. Thesis Research Presentation PowerPoint Template

If your research presentation project belongs to academia, then this is the slide deck to pair that presentation. With a formal aesthetic and minimalistic style, this research presentation template focuses only on exposing your information as clearly as possible.

Use its included bar charts and graphs to introduce data, change the background of each slide to suit the topic of your presentation, and customize each of its elements to meet the requirements of your project with ease.

4. Animated Research Cards PowerPoint Template

Visualize ideas and their connection points with the help of this research card template for PowerPoint. This slide deck, for example, can help speakers talk about alternative concepts to what they are currently managing and its possible outcomes, among different other usages this versatile PPT template has. Zoom Animation effects make a smooth transition between cards (or ideas).

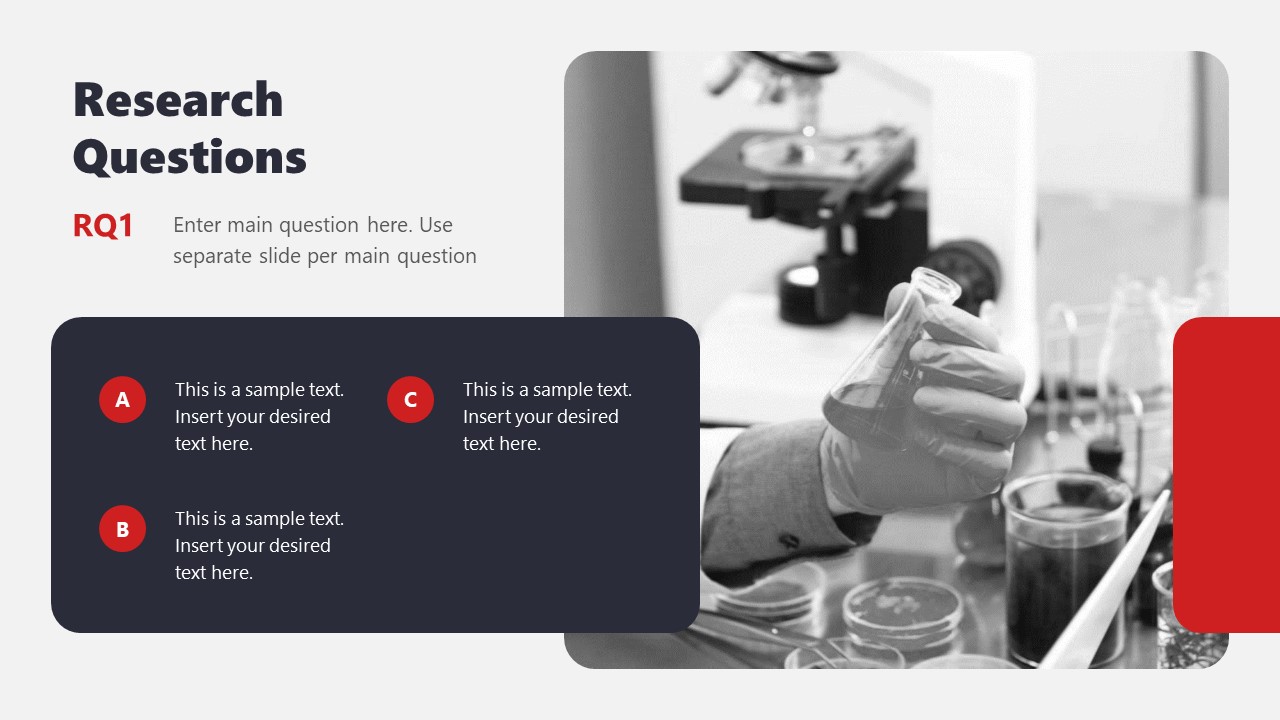

5. Research Presentation Slide Deck for PowerPoint

With a distinctive professional style, this research presentation PPT template helps business professionals and academics alike to introduce the findings of their work to team members or investors.

By accessing this template, you get the following slides:

- Introduction

- Problem Statement

- Research Questions

- Conceptual Research Framework (Concepts, Theories, Actors, & Constructs)

- Study design and methods

- Population & Sampling

- Data Collection

- Data Analysis

Check it out today and craft a powerful research presentation out of it!

A successful research presentation in business is not just about presenting data; it’s about persuasion to take meaningful action. It’s the bridge that connects your research efforts to the strategic initiatives of your organization. To embark on this journey successfully, planning your presentation thoroughly is paramount, from designing your PowerPoint to the delivery.

Take a look and get inspiration from the sample research presentation slides above, put our tips to heart, and transform your research findings into a compelling call to action.

Like this article? Please share

Academics, Presentation Approaches, Research & Development Filed under Presentation Ideas

Related Articles

Filed under Education • July 10th, 2024

How to Memorize a Presentation: Guide + Templates

Become a proficient presenter by mastering the art of how to memorize a presentation. Nine different techniques + PPT templates here.

Filed under Design • July 3rd, 2024

ChatGPT Prompts for Presentations

Make ChatGPT your best ally for presentation design. Learn how to create effective ChatGPT prompts for presentations here.

Filed under Design • July 1st, 2024

Calculating the Slide Count: How Many Slides Do I Need for a Presentation?

There’s no magical formula for estimating presentation slides, but this guide can help us approximate the number of slides we need for a presentation.

Leave a Reply

Home » Blog » How to Write a Seminar Paper: A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Write a Seminar Paper: A Step-by-Step Guide

Table of Contents

Learn How to Write a Seminar Paper

Writing and planning a seminar paper can be quite a challenge for any student. For many students, it is unusual to deal scientifically with a question or research question. In addition, you must be able to identify the overall problem and then derive specific work steps.

In this article, we would like to show you how to successfully plan and write a seminar paper. It’s not that difficult at all. If you have already dealt with the topic thoroughly, you are already on the right track. In addition to the content, the formal aspect of the work, namely the layout, should not be disregarded.

What is a seminar paper?

You write a seminar paper over a long period. As a result, this type of work is a headache for many students. With an exam, you learn at short notice and therefore you do not have to deal with the topic for a long time. When planning and preparing a seminar paper, you will have to deal with the work and the problem every day. Planning a seminar paper alone takes a lot of time. You must find a suitable topic. Furthermore, you must find a scientific problem that you want to solve with your seminar paper. Then you must research the literature operate and create a plan for the processing of all work steps so that you can submit your work on time. The curious thing is that planning your work will take you a lot more time than writing your work. If you have planned your term paper correctly from the beginning, then writing will only take up a fraction of the total time. Writing a seminar paper is exhausting. Therefore, you will also learn important key competencies and skills that you will need later in your job. During the planning and writing of your thesis, you will acquire the following important skills:

- You will acquire techniques of scientific work. This includes literature research, indirect and direct quotations, and dealing with a scientific problem over a longer period.

- You will acquire the relevant specialist vocabulary.

- You will understand the topic and be able to find a solution.

Tips for planning a seminar paper

You should not underestimate the planning of a seminar paper. Believe it or not, it represents the bulk of your work. Planning takes the most time. But if you do this correctly, the writing process will be very easy for you. In the following, we will show you what you need to consider when planning.

Find a seminar paper topic

It is not that easy to find a topic for the seminar paper. If your lecturer does not specify a topic, then you are on your own. In general, it would be good if you look again at all the topics, contents, and discussion points of the seminar. This gives you a basis for finding your topic. You should also proceed in such a way that you structure and prioritize the ideas found in a brainstorming session. But you must find a topic that interests you.

Literature research seminar paper

Now we come to the literature research. You should always have the goal in mind to back up you’re reasoning with sources. Finally, you can search for suitable sources for your work in the following places:

- The library: There is hardly a better place at the university to look for literature. In a library, you will not only find books but also electronic media that you can use for research. For example, you can use the OPAC (Online Public Access Catalog). In this way, you will ensure an excellent overview of the available literature on your topic.

- Electronic journal directory: The electronic journal directory allows you to search for magazines or specialist journals. Scientific journals are often seen as sources. They are often written in sophisticated language and deal with current and practical cases.

- Internet: The Internet is also a convenient way to find suitable sources. You can use the services of Google Scholar and Google Books. It can also happen from time to time that some books are not fully illustrated on these services. You will find a good overview of the sources that you need here. The tables of contents also give you a good reference point for your further research.

Discussion of the topic of a seminar paper

You have now carried out a thorough literature search. So, you can start to create the first outline for your work. In the beginning, your outline should be rough, as it will adapt in the course of your work. The best way to do this is to secure a consultation hour with your lecturer to discuss your topic together. Your professor can also give you useful tips on your topic. This conversation is extremely valuable for you because in this way your approach will be approved, and you are on the safe side.

Structure of a seminar paper

Now it’s down to the nitty-gritty. You have certainly already started primary research. Furthermore, it can be assumed that you have already recorded the first research results. Now you must have a big mess of all kinds of data. When writing your seminar paper, it is now a matter of putting down all results, analyses, and interpretations in writing. But that’s not that easy at all. In this step, you must acquire the ability to structure and order all results. It is best to start with the introduction.

Is it difficult for you to write or do you think you have writer’s block and are pushing this part in front of you? Then you should simply find out here how you can solve your writer’s block. Of course, correct academic work also means being able to quote correctly.

Introduction:

In the introduction to the seminar paper for you, it is now a matter of presenting your topic. Now you must justify why you want to deal with the topic you have chosen. So, you should not only have an interest in the topic but also be able to convince future readers of your views. In a further step, you have justified your topic and now bring your question to the fore. In this way, you create a foundation for yourself and prevent your seminar paper from becoming a mere string of facts. Rather, you deliver a paper with information that will answer your research questions. Finally, you explain the approach you have chosen. Here you go into which research methods you have used.

The main part of the seminar paper represents the most demanding part. The most important thing is that a common thread is recognizable in your work. To do this, you should structure your work in such a way that your arguments and sub-chapters are logically linked. The literature you have analysed serves as a basis for developing a comprehensible argumentation. You use it to show the gaps that exist in the research. Then you start with the practical part. Here you show what results in your analysis and interpretation have brought.

Conclusion:

In the final part of the conclusion of the seminar paper, you formulate the answers to your question. You must match the ending with your introduction. Then you summarize everything that you have shown in the main part. Be careful not to deliver any new results. At the end of the conclusion, you give a prognosis or an outlook.

Final Thought

As you can see, when writing a seminar paper, the precise planning of the individual work steps in advance is particularly important. This not only saves you from careless gaps in your argumentation structure but also helps you to bring systematics into the recording and solution of your research question. Once you’ve got the hang of the extensive preparatory work, your argumentative analysis develops almost by itself. The nice thing about writing a seminar paper is that you can gain completely new insights into a scientific topic and make them accessible to a wider public.

If you like this article, see others like it:

Balancing Work and Life: Achieving Success in Nigeria’s Competitive Job Market

2024 complete nigeria current affairs pdf free download, 2024 nigeria current affairs quiz questions & answers, learn how to trade forex: a beginner’s guide, 5 corporate team building activities ideas for introverted employees, related topics, how to search for journals for a research project, a step-by-step guide to writing a comparative analysis, signs it’s time to re-evaluate your career goals, 5 common career change fears and what to do, how to plan an affordable vacation as a student.

- Funding Opportunities

- Discussion-Based Events

- Graduate Programs

- Ideas that Shape the World

- Digital Community

- Planned Giving

- Donor Events

How to Prepare for a Paper Presentation at an Academic Conference

In my previous post, I laid out a timeline for choosing an academic conference. This post will lay out four steps to help you successfully prepare for a paper presentation at an academic conference.

Pay attention to the deadline for proposals .

Your proposal outlines the paper you are going to write, not a paper you have written . You may treat your proposal as a commitment device to “force” you to write the paper, but the final paper may well differ from your original intention.

The Claremont Graduate University Writing Center offers some good examples of proposals here .

Write a winning abstract to get your paper accepted into the conference.

Abstracts are an afterthought to many graduate students, but they are the what the reviewer looks at first. To get your paper accepted to a conference, you’ll need to write an abstract of 200 to 500 words .

The emphasis should be on brevity and clarity. It should tell the reader what your paper is about, why the reader should be interested, and why the paper should be accepted.

Additionally, it should:

- Specify your thesis

- Identify your paper fills a gap in the current literature.

- Outline what you actually do in the paper.

- Point out your original contribution.

- Include a concluding sentence.

Academic Conferences and Publishing International offers some additional advice on writing a conference abstract as you prepare for your paper presentation at an academic conference.

Pay attention to your presentation itself.

In order to convey excitement about your paper, you need to think about your presentation as well as the findings you are communicating.

Note the conference time limit and stick to it. Practice while timing yourself, and do it in front of a mirror. I also recommend practicing in front of your peers; organizing a departmental brown bag lunch could be a great way to do this. As you are preparing, keep in mind that reading from notes is better than reading directly from your paper.

Once you arrive at the conference, check the location of the room as soon as you can before the event. Arrive early to make sure any audiovisual equipment you plan to use is working, and be ready to present without it in case it is not.

Always stand when giving your paper presentation at an academic conference. Begin by stating your name and institution. Establish eye contact across the room, and speak slowly and clearly to your audience. Explain the structure of your presentation. End with your contribution to your discipline. Finally, be polite (not defensive) when engaging in discussion and answering questions about your research.

By focusing on (a) making sure your work contributes something to your field (b) adhering to deadlines and convincing conference organizers that your paper is worth presenting and (c) creating a compelling presentation that aptly highlights the content of your research, you’ll make the most of your time at the conference.

Nigel Ashford

Previous post should i get a phd 5 questions to ask yourself before you decide, next post how to choose and prepare for academic conferences as a graduate student.

Comments are closed.

- Privacy Policy

© 2024 Institute for Humane Studies at George Mason University

Here is the timeline for our application process:

- Apply for a position

- An HR team member will review your application submission

- If selected for consideration, you will speak with a recruiter

- If your experience and skills match the role, you will interview with the hiring manager

- If you are a potential fit for the position, you will interview with additional staff members

- If you are the candidate chosen, we will extend a job offer

All candidates will be notified regarding the status of their application within two to three weeks of submission. As new positions often become available, we encourage you to visit our site frequently for additional opportunities that align with your interests and skills.

Conference Papers

What this handout is about.

This handout outlines strategies for writing and presenting papers for academic conferences.

What’s special about conference papers?

Conference papers can be an effective way to try out new ideas, introduce your work to colleagues, and hone your research questions. Presenting at a conference is a great opportunity for gaining valuable feedback from a community of scholars and for increasing your professional stature in your field.

A conference paper is often both a written document and an oral presentation. You may be asked to submit a copy of your paper to a commentator before you present at the conference. Thus, your paper should follow the conventions for academic papers and oral presentations.

Preparing to write your conference paper

There are several factors to consider as you get started on your conference paper.

Determine the structure and style

How will you structure your presentation? This is an important question, because your presentation format will shape your written document. Some possibilities for your session include:

- A visual presentation, including software such as PowerPoint or Prezi

- A paper that you read aloud

- A roundtable discussion

Presentations can be a combination of these styles. For example, you might read a paper aloud while displaying images. Following your paper, you might participate in an informal conversation with your fellow presenters.

You will also need to know how long your paper should be. Presentations are usually 15-20 minutes. A general rule of thumb is that one double-spaced page takes 2-2.5 minutes to read out loud. Thus an 8-10 page, double-spaced paper is often a good fit for a 15-20 minute presentation. Adhere to the time limit. Make sure that your written paper conforms to the presentation constraints.

Consider the conventions of the conference and the structure of your session

It is important to meet the expectations of your conference audience. Have you been to an academic conference previously? How were presentations structured? What kinds of presentations did you find most effective? What do you know about the particular conference you are planning to attend? Some professional organizations have their own rules and suggestions for writing and presenting for their conferences. Make sure to find out what they are and stick to them.

If you proposed a panel with other scholars, then you should already have a good idea of your panel’s expectations. However, if you submitted your paper individually and the conference organizers placed it on a panel with other papers, you will need additional information.

Will there be a commentator? Commentators, also called respondents or discussants, can be great additions to panels, since their job is to pull the papers together and pose questions. If there will be a commentator, be sure to know when they would like to have a copy of your paper. Observe this deadline.

You may also want to find out what your fellow presenters will be talking about. Will you circulate your papers among the other panelists prior to the conference? Will your papers address common themes? Will you discuss intersections with each other’s work after your individual presentations? How collaborative do you want your panel to be?

Analyze your audience

Knowing your audience is critical for any writing assignment, but conference papers are special because you will be physically interacting with them. Take a look at our handout on audience . Anticipating the needs of your listeners will help you write a conference paper that connects your specific research to their broader concerns in a compelling way.

What are the concerns of the conference?

You can identify these by revisiting the call for proposals and reviewing the mission statement or theme of the conference. What key words or concepts are repeated? How does your work relate to these larger research questions? If you choose to orient your paper toward one of these themes, make sure there is a genuine relationship. Superficial use of key terms can weaken your paper.

What are the primary concerns of the field?

How do you bridge the gap between your research and your field’s broader concerns? Finding these linkages is part of the brainstorming process. See our handout on brainstorming . If you are presenting at a conference that is within your primary field, you should be familiar with leading concerns and questions. If you will be attending an interdisciplinary conference or a conference outside of your field, or if you simply need to refresh your knowledge of what’s current in your discipline, you can:

- Read recently published journals and books, including recent publications by the conference’s featured speakers

- Talk to people who have been to the conference

- Pay attention to questions about theory and method. What questions come up in the literature? What foundational texts should you be familiar with?

- Review the initial research questions that inspired your project. Think about the big questions in the secondary literature of your field.

- Try a free-writing exercise. Imagine that you are explaining your project to someone who is in your department, but is unfamiliar with your specific topic. What can you assume they already know? Where will you need to start in your explanation? How will you establish common ground?

Contextualizing your narrow research question within larger trends in the field will help you connect with your audience. You might be really excited about a previously unknown nineteenth-century poet. But will your topic engage others? You don’t want people to leave your presentation, thinking, “What was the point of that?” By carefully analyzing your audience and considering the concerns of the conference and the field, you can present a paper that will have your listeners thinking, “Wow! Why haven’t I heard about that obscure poet before? She is really important for understanding developments in Romantic poetry in the 1800s!”

Writing your conference paper

I have a really great research paper/manuscript/dissertation chapter on this same topic. Should I cut and paste?

Be careful here. Time constraints and the needs of your audience may require a tightly focused and limited message. To create a paper tailored to the conference, you might want to set everything aside and create a brand new document. Don’t worry—you will still have that paper, manuscript, or chapter if you need it. But you will also benefit from taking a fresh look at your research.

Citing sources

Since your conference paper will be part of an oral presentation, there are special considerations for citations. You should observe the conventions of your discipline with regard to including citations in your written paper. However, you will also need to incorporate verbal cues to set your evidence and quotations off from your text when presenting. For example, you can say: “As Nietzsche said, quote, ‘And if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you,’ end quote.” If you use multiple quotations in your paper, think about omitting the terms “quote” and “end quote,” as these can become repetitive. Instead, signal quotations through the inflection of your voice or with strategic pauses.

Organizing the paper

There are numerous ways to effectively organize your conference paper, but remember to have a focused message that fits the time constraints and meets the needs of your audience. You can begin by connecting your research to the audience’s concerns, then share a few examples/case studies from your research, and then, in conclusion, broaden the discussion back out to general issues in the field.

Don’t overwhelm or confuse your audience

You should limit the information that you present. Don’t attempt to summarize your entire dissertation in 10 pages. Instead, try selecting main points and provide examples to support those points. Alternatively, you might focus on one main idea or case study and use 2-4 examples to explain it.

Check for clarity in the text

One way to anticipate how your ideas will sound is to read your paper out loud. Reading out loud is an excellent proofreading technique and is a great way to check the clarity of your ideas; you are likely to hear problems that you didn’t notice in just scanning your draft. Help listeners understand your ideas by making sure that subjects and verbs are clear and by avoiding unnecessarily complex sentences.

Include verbal cues in the text

Make liberal use of transitional phrases like however, therefore, and thus, as well as signpost words like first, next, etc.

If you have 5 main points, say so at the beginning and list those 5 ideas. Refer back to this structure frequently as you transition between sections (“Now, I will discuss my fourth point, the importance of plasma”).

Use a phrase like “I argue” to announce your thesis statement. Be sure that there is only one of these phrases—otherwise your audience will be confused about your central message.

Refer back to the structure, and signal moments where you are transitioning to a new topic: “I just talked about x, now I’m going to talk about y.”

I’ve written my conference paper, now what?

Now that you’ve drafted your conference paper, it’s time for the most important part—delivering it before an audience of scholars in your field! Remember that writing the paper is only one half of what a conference paper entails. It is both a written text and a presentation.

With preparation, your presentation will be a success. Here are a few tips for an effective presentation. You can also see our handout on speeches .

Cues to yourself

Include helpful hints in your personal copy of the paper. You can remind yourself to pause, look up and make eye contact with your audience, or employ body language to enhance your message. If you are using a slideshow, you can indicate when to change slides. Increasing the font size to 14-16 pt. can make your paper easier to read.

Practice, practice, practice

When you practice, time yourself. Are you reading too fast? Are you enunciating clearly? Do you know how to pronounce all of the words in your paper? Record your talk and critically listen to yourself. Practice in front of friends and colleagues.

If you are using technology, familiarize yourself with it. Check and double-check your images. Remember, they are part of your presentation and should be proofread just like your paper. Print a backup copy of your images and paper, and bring copies of your materials in multiple formats, just in case. Be sure to check with the conference organizers about available technology.

Professionalism

The written text is only one aspect of the overall conference paper. The other is your presentation. This means that your audience will evaluate both your work and you! So remember to convey the appropriate level of professionalism.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Adler, Abby. 2010. “Talking the Talk: Tips on Giving a Successful Conference Presentation.” Psychological Science Agenda 24 (4).

Kerber, Linda K. 2008. “Conference Rules: How to Present a Scholarly Paper.” The Chronicle of Higher Education , March 21, 2008. https://www.chronicle.com/article/Conference-Rules-How-to/45734 .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Biomedical Engineering and the Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, United States of America

- Kristen M. Naegle

Published: December 2, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

- Reader Comments

Citation: Naegle KM (2021) Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides. PLoS Comput Biol 17(12): e1009554. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

Copyright: © 2021 Kristen M. Naegle. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The author has declared no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The “presentation slide” is the building block of all academic presentations, whether they are journal clubs, thesis committee meetings, short conference talks, or hour-long seminars. A slide is a single page projected on a screen, usually built on the premise of a title, body, and figures or tables and includes both what is shown and what is spoken about that slide. Multiple slides are strung together to tell the larger story of the presentation. While there have been excellent 10 simple rules on giving entire presentations [ 1 , 2 ], there was an absence in the fine details of how to design a slide for optimal effect—such as the design elements that allow slides to convey meaningful information, to keep the audience engaged and informed, and to deliver the information intended and in the time frame allowed. As all research presentations seek to teach, effective slide design borrows from the same principles as effective teaching, including the consideration of cognitive processing your audience is relying on to organize, process, and retain information. This is written for anyone who needs to prepare slides from any length scale and for most purposes of conveying research to broad audiences. The rules are broken into 3 primary areas. Rules 1 to 5 are about optimizing the scope of each slide. Rules 6 to 8 are about principles around designing elements of the slide. Rules 9 to 10 are about preparing for your presentation, with the slides as the central focus of that preparation.

Rule 1: Include only one idea per slide

Each slide should have one central objective to deliver—the main idea or question [ 3 – 5 ]. Often, this means breaking complex ideas down into manageable pieces (see Fig 1 , where “background” information has been split into 2 key concepts). In another example, if you are presenting a complex computational approach in a large flow diagram, introduce it in smaller units, building it up until you finish with the entire diagram. The progressive buildup of complex information means that audiences are prepared to understand the whole picture, once you have dedicated time to each of the parts. You can accomplish the buildup of components in several ways—for example, using presentation software to cover/uncover information. Personally, I choose to create separate slides for each piece of information content I introduce—where the final slide has the entire diagram, and I use cropping or a cover on duplicated slides that come before to hide what I’m not yet ready to include. I use this method in order to ensure that each slide in my deck truly presents one specific idea (the new content) and the amount of the new information on that slide can be described in 1 minute (Rule 2), but it comes with the trade-off—a change to the format of one of the slides in the series often means changes to all slides.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Top left: A background slide that describes the background material on a project from my lab. The slide was created using a PowerPoint Design Template, which had to be modified to increase default text sizes for this figure (i.e., the default text sizes are even worse than shown here). Bottom row: The 2 new slides that break up the content into 2 explicit ideas about the background, using a central graphic. In the first slide, the graphic is an explicit example of the SH2 domain of PI3-kinase interacting with a phosphorylation site (Y754) on the PDGFR to describe the important details of what an SH2 domain and phosphotyrosine ligand are and how they interact. I use that same graphic in the second slide to generalize all binding events and include redundant text to drive home the central message (a lot of possible interactions might occur in the human proteome, more than we can currently measure). Top right highlights which rules were used to move from the original slide to the new slide. Specific changes as highlighted by Rule 7 include increasing contrast by changing the background color, increasing font size, changing to sans serif fonts, and removing all capital text and underlining (using bold to draw attention). PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554.g001

Rule 2: Spend only 1 minute per slide

When you present your slide in the talk, it should take 1 minute or less to discuss. This rule is really helpful for planning purposes—a 20-minute presentation should have somewhere around 20 slides. Also, frequently giving your audience new information to feast on helps keep them engaged. During practice, if you find yourself spending more than a minute on a slide, there’s too much for that one slide—it’s time to break up the content into multiple slides or even remove information that is not wholly central to the story you are trying to tell. Reduce, reduce, reduce, until you get to a single message, clearly described, which takes less than 1 minute to present.

Rule 3: Make use of your heading

When each slide conveys only one message, use the heading of that slide to write exactly the message you are trying to deliver. Instead of titling the slide “Results,” try “CTNND1 is central to metastasis” or “False-positive rates are highly sample specific.” Use this landmark signpost to ensure that all the content on that slide is related exactly to the heading and only the heading. Think of the slide heading as the introductory or concluding sentence of a paragraph and the slide content the rest of the paragraph that supports the main point of the paragraph. An audience member should be able to follow along with you in the “paragraph” and come to the same conclusion sentence as your header at the end of the slide.

Rule 4: Include only essential points

While you are speaking, audience members’ eyes and minds will be wandering over your slide. If you have a comment, detail, or figure on a slide, have a plan to explicitly identify and talk about it. If you don’t think it’s important enough to spend time on, then don’t have it on your slide. This is especially important when faculty are present. I often tell students that thesis committee members are like cats: If you put a shiny bauble in front of them, they’ll go after it. Be sure to only put the shiny baubles on slides that you want them to focus on. Putting together a thesis meeting for only faculty is really an exercise in herding cats (if you have cats, you know this is no easy feat). Clear and concise slide design will go a long way in helping you corral those easily distracted faculty members.

Rule 5: Give credit, where credit is due

An exception to Rule 4 is to include proper citations or references to work on your slide. When adding citations, names of other researchers, or other types of credit, use a consistent style and method for adding this information to your slides. Your audience will then be able to easily partition this information from the other content. A common mistake people make is to think “I’ll add that reference later,” but I highly recommend you put the proper reference on the slide at the time you make it, before you forget where it came from. Finally, in certain kinds of presentations, credits can make it clear who did the work. For the faculty members heading labs, it is an effective way to connect your audience with the personnel in the lab who did the work, which is a great career booster for that person. For graduate students, it is an effective way to delineate your contribution to the work, especially in meetings where the goal is to establish your credentials for meeting the rigors of a PhD checkpoint.

Rule 6: Use graphics effectively

As a rule, you should almost never have slides that only contain text. Build your slides around good visualizations. It is a visual presentation after all, and as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. However, on the flip side, don’t muddy the point of the slide by putting too many complex graphics on a single slide. A multipanel figure that you might include in a manuscript should often be broken into 1 panel per slide (see Rule 1 ). One way to ensure that you use the graphics effectively is to make a point to introduce the figure and its elements to the audience verbally, especially for data figures. For example, you might say the following: “This graph here shows the measured false-positive rate for an experiment and each point is a replicate of the experiment, the graph demonstrates …” If you have put too much on one slide to present in 1 minute (see Rule 2 ), then the complexity or number of the visualizations is too much for just one slide.

Rule 7: Design to avoid cognitive overload

The type of slide elements, the number of them, and how you present them all impact the ability for the audience to intake, organize, and remember the content. For example, a frequent mistake in slide design is to include full sentences, but reading and verbal processing use the same cognitive channels—therefore, an audience member can either read the slide, listen to you, or do some part of both (each poorly), as a result of cognitive overload [ 4 ]. The visual channel is separate, allowing images/videos to be processed with auditory information without cognitive overload [ 6 ] (Rule 6). As presentations are an exercise in listening, and not reading, do what you can to optimize the ability of the audience to listen. Use words sparingly as “guide posts” to you and the audience about major points of the slide. In fact, you can add short text fragments, redundant with the verbal component of the presentation, which has been shown to improve retention [ 7 ] (see Fig 1 for an example of redundant text that avoids cognitive overload). Be careful in the selection of a slide template to minimize accidentally adding elements that the audience must process, but are unimportant. David JP Phillips argues (and effectively demonstrates in his TEDx talk [ 5 ]) that the human brain can easily interpret 6 elements and more than that requires a 500% increase in human cognition load—so keep the total number of elements on the slide to 6 or less. Finally, in addition to the use of short text, white space, and the effective use of graphics/images, you can improve ease of cognitive processing further by considering color choices and font type and size. Here are a few suggestions for improving the experience for your audience, highlighting the importance of these elements for some specific groups:

- Use high contrast colors and simple backgrounds with low to no color—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment.

- Use sans serif fonts and large font sizes (including figure legends), avoid italics, underlining (use bold font instead for emphasis), and all capital letters—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment [ 8 ].

- Use color combinations and palettes that can be understood by those with different forms of color blindness [ 9 ]. There are excellent tools available to identify colors to use and ways to simulate your presentation or figures as they might be seen by a person with color blindness (easily found by a web search).

- In this increasing world of virtual presentation tools, consider practicing your talk with a closed captioning system capture your words. Use this to identify how to improve your speaking pace, volume, and annunciation to improve understanding by all members of your audience, but especially those with a hearing impairment.

Rule 8: Design the slide so that a distracted person gets the main takeaway

It is very difficult to stay focused on a presentation, especially if it is long or if it is part of a longer series of talks at a conference. Audience members may get distracted by an important email, or they may start dreaming of lunch. So, it’s important to look at your slide and ask “If they heard nothing I said, will they understand the key concept of this slide?” The other rules are set up to help with this, including clarity of the single point of the slide (Rule 1), titling it with a major conclusion (Rule 3), and the use of figures (Rule 6) and short text redundant to your verbal description (Rule 7). However, with each slide, step back and ask whether its main conclusion is conveyed, even if someone didn’t hear your accompanying dialog. Importantly, ask if the information on the slide is at the right level of abstraction. For example, do you have too many details about the experiment, which hides the conclusion of the experiment (i.e., breaking Rule 1)? If you are worried about not having enough details, keep a slide at the end of your slide deck (after your conclusions and acknowledgments) with the more detailed information that you can refer to during a question and answer period.

Rule 9: Iteratively improve slide design through practice

Well-designed slides that follow the first 8 rules are intended to help you deliver the message you intend and in the amount of time you intend to deliver it in. The best way to ensure that you nailed slide design for your presentation is to practice, typically a lot. The most important aspects of practicing a new presentation, with an eye toward slide design, are the following 2 key points: (1) practice to ensure that you hit, each time through, the most important points (for example, the text guide posts you left yourself and the title of the slide); and (2) practice to ensure that as you conclude the end of one slide, it leads directly to the next slide. Slide transitions, what you say as you end one slide and begin the next, are important to keeping the flow of the “story.” Practice is when I discover that the order of my presentation is poor or that I left myself too few guideposts to remember what was coming next. Additionally, during practice, the most frequent things I have to improve relate to Rule 2 (the slide takes too long to present, usually because I broke Rule 1, and I’m delivering too much information for one slide), Rule 4 (I have a nonessential detail on the slide), and Rule 5 (I forgot to give a key reference). The very best type of practice is in front of an audience (for example, your lab or peers), where, with fresh perspectives, they can help you identify places for improving slide content, design, and connections across the entirety of your talk.

Rule 10: Design to mitigate the impact of technical disasters

The real presentation almost never goes as we planned in our heads or during our practice. Maybe the speaker before you went over time and now you need to adjust. Maybe the computer the organizer is having you use won’t show your video. Maybe your internet is poor on the day you are giving a virtual presentation at a conference. Technical problems are routinely part of the practice of sharing your work through presentations. Hence, you can design your slides to limit the impact certain kinds of technical disasters create and also prepare alternate approaches. Here are just a few examples of the preparation you can do that will take you a long way toward avoiding a complete fiasco:

- Save your presentation as a PDF—if the version of Keynote or PowerPoint on a host computer cause issues, you still have a functional copy that has a higher guarantee of compatibility.

- In using videos, create a backup slide with screen shots of key results. For example, if I have a video of cell migration, I’ll be sure to have a copy of the start and end of the video, in case the video doesn’t play. Even if the video worked, you can pause on this backup slide and take the time to highlight the key results in words if someone could not see or understand the video.

- Avoid animations, such as figures or text that flash/fly-in/etc. Surveys suggest that no one likes movement in presentations [ 3 , 4 ]. There is likely a cognitive underpinning to the almost universal distaste of pointless animations that relates to the idea proposed by Kosslyn and colleagues that animations are salient perceptual units that captures direct attention [ 4 ]. Although perceptual salience can be used to draw attention to and improve retention of specific points, if you use this approach for unnecessary/unimportant things (like animation of your bullet point text, fly-ins of figures, etc.), then you will distract your audience from the important content. Finally, animations cause additional processing burdens for people with visual impairments [ 10 ] and create opportunities for technical disasters if the software on the host system is not compatible with your planned animation.

Conclusions

These rules are just a start in creating more engaging presentations that increase audience retention of your material. However, there are wonderful resources on continuing on the journey of becoming an amazing public speaker, which includes understanding the psychology and neuroscience behind human perception and learning. For example, as highlighted in Rule 7, David JP Phillips has a wonderful TEDx talk on the subject [ 5 ], and “PowerPoint presentation flaws and failures: A psychological analysis,” by Kosslyn and colleagues is deeply detailed about a number of aspects of human cognition and presentation style [ 4 ]. There are many books on the topic, including the popular “Presentation Zen” by Garr Reynolds [ 11 ]. Finally, although briefly touched on here, the visualization of data is an entire topic of its own that is worth perfecting for both written and oral presentations of work, with fantastic resources like Edward Tufte’s “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information” [ 12 ] or the article “Visualization of Biomedical Data” by O’Donoghue and colleagues [ 13 ].

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the countless presenters, colleagues, students, and mentors from which I have learned a great deal from on effective presentations. Also, a thank you to the wonderful resources published by organizations on how to increase inclusivity. A special thanks to Dr. Jason Papin and Dr. Michael Guertin on early feedback of this editorial.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 3. Teaching VUC for Making Better PowerPoint Presentations. n.d. Available from: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/making-better-powerpoint-presentations/#baddeley .

- 8. Creating a dyslexia friendly workplace. Dyslexia friendly style guide. nd. Available from: https://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/advice/employers/creating-a-dyslexia-friendly-workplace/dyslexia-friendly-style-guide .

- 9. Cravit R. How to Use Color Blind Friendly Palettes to Make Your Charts Accessible. 2019. Available from: https://venngage.com/blog/color-blind-friendly-palette/ .

- 10. Making your conference presentation more accessible to blind and partially sighted people. n.d. Available from: https://vocaleyes.co.uk/services/resources/guidelines-for-making-your-conference-presentation-more-accessible-to-blind-and-partially-sighted-people/ .

- 11. Reynolds G. Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery. 2nd ed. New Riders Pub; 2011.