Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Prewriting (Invention) General Questions

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Beyond the strategies outlined in the previous section, these questions might help you begin writing.

Explore the problem — not the topic

- Who is your reader?

- What is your purpose?

- Who are you, the writer? (What image or persona do you want to project?)

Make your goals operational

- How can you achieve your purpose?

- Can you make a plan?

Generate some ideas

- Keep writing

- Don't censor or evaluate

- Keep returning to the problem

Talk to your reader

- What questions would they ask?

- What different kinds of readers might you have?

Ask yourself questions

Journalistic questions

Who? What? Where? When? Why? How? So What?

Stasis questions

Conjecture: what are the facts? Definition: what is the meaning or nature of the issue? Quality: what is the seriousness of the issue? Policy: what should we do about the issue? For more information on the stases, please go to the OWL resource on stasis theory .

Classical topics (patterns of argument)

- How does the dictionary define ____?

- What do I mean by ____?

- What group of things does ____ belong to?

- How is ____ different from other things?

- What parts can ____ be divided into?

- Does ____ mean something now that it didn't years ago? If so, what?

- What other words mean about the same as ____?

- What are some concrete examples of ____?

- When is the meaning of ____ misunderstood?

Comparison/Contrast

- What is ____ similar to? In what ways?

- What is ____ different from? In what ways?

- ____ is superior (inferior) to what? How?

- ____ is most unlike (like) what? How?

Relationship

- What causes ____?

- What are the effects of ____?

- What is the purpose of ____? - What is the consequence of ____?

- What comes before (after) ____?

- What have I heard people say about ____?

- What are some facts of statistics about ____?

- Can I quote any proverbs, poems, or sayings about ____?

- Are there any laws about ____?

Circumstance

- Is ____ possible or impossible?

- What qualities, conditions, or circumstances make ____ possible or impossible?

- When did ____ happen previously?

- Who can do ____?

- If ____ starts, what makes it end?

- What would it take for ____ to happen now?

- What would prevent ___ from happening?

Contrastive features

- How is ____ different from things similar to it?

- How has ____ been different for me?

- How much can ____ change and still be itself?

- How is ____ changing?

- How much does ____ change from day to day?

- What are the different varieties of ____?

Distribution

- Where and when does ____ take place?

- What is the larger thing of which ___ is a part?

- What is the function of ____ in this larger thing?

Cubing (considering a subject from six points of view)

- *Describe* it (colors, shapes, sizes, etc.)

- *Compare* it (What is it similar to?)

- *Associate* it (What does it make you think of?)

- *Analyze* it (Tell how it's made)

- *Apply* it (What can you do with it? How can it be used?)

- *Argue* for or against it

Make an analogy

Choose an activity from column A to explain it by describing it in terms of an activity from column B (or vice-versa).

Rest and incubate.

(Adapted from Linda Flower's Problem-Solving Strategies for Writing, Gregory and Elizabeth Cowan's Writing, and Gordon Rohman and Albert Wlecke's Prewriting.)

Flower, Linda. Problem-Solving Strategies for Writing . Third Edition. Orders, 1989.

Neeld, Elizabeth Cowan, and Gregory Cowan. Writing . Scott, Foresman, 1986.

- LEARN WITH CHLOE

- ABOUT CHLOE

7 Powerful Questions to Ask Yourself Before You Start Your Essay

Do you ever find yourself diving into writing without much planning before you start your essay?

I see this A LOT with the students I work with and a few things tend to happen:

– the writing process takes a lot longer – the writing process is more stressful – they end up having to cut loads of words that aren’t relevant – they go off on tangents and don’t answer the question – they get lower grades because of it.

I don’t want this to happen to you. Instead, follow my simple planning process before you start your essay, and you’ll find the whole process much easier AND you’ll achieve higher grades.

In this episode, I take you through a worked example essay question, and teach you the 7 simple but powerful questions you should ask yourself before you start your essay to ensure your arguments are strong, coherent, and that you actually answer the task you’ve been set.

~ FREE TRAINING ~

How to Actually START Your Essay

Workbook + video training to take you from procrastination and overwhelm to understanding your question and mapping out your ideas with momentum. Easier, faster essay writing (and higher grades) await.

Ways to listen:

- Listen in the player above

- Click to listen on Apple Podcasts .

- Click to listen on Spotify .

- Click to listen on Google Podcasts .

Resources and links:

- Check out my membership, the Kickbutt Students Club .

- Check out my range of study skills trainings .

- Sign up to my awesome email newsletter – Students Who Graduate .

- Grab a copy of my book – The Return to Study Handbook .

- Find out more and enrol in Essays With Ease .

You may also like...

7 ways to write a sh*te essay (and how to write a great essay instead).

In this episode, you’ll learn the do’s and don’ts of academic writing to help you write a great essay. We’ll start by highlighting seven common mistakes that lead to subpar essays – or what I refer to as shite essays. Because learning what NOT to do can really help you get clear on what you

How to Become the Student Who Graduates With Their Dream Grades

If you’ve ever wondered how to graduate with dream grades, here’s your roadmap. Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed and stressed out on your academic journey? It’s time to break free from that cycle. We’ll explore the powerful concept that results are a product of behaviors, which are rooted in your identity. You’ll learn how

7 Essential Ways to Ensure This Is Your Best Academic Year Yet

Are you ready to embark on your best academic year ever? Getting ready for the new academic year is about more than buying new stationery and setting up your study space. It IS possible to take a few simple, intentional actions now to set the stage for an easier studying life AND epic grades. The

What do you want to learn?

Either select the study skill you want to dive into, or choose whether you're in the mood to check out a blog post or podcast episode.

- Confident learning

- Critical thinking

- Distance learning

- Essay writing

- Exam preparation

- Higher grades

- Mature student

- Note taking

- Organisation

- Procrastination

- Productivity

- Study challenge

- Study habits

- Studying while working

FREE EMAIL SERIES

How to Build Unshakeable Studying Confidence in Just 5 Days

Learn 5 powerful strategies to build an unshakeable foundation of studying confidence.

Say goodbye to self-doubt and traumatic school memories getting in the way of you acing your learning as an adult.

And instead say hello to studying with more motivation, positivity and ease so that you can graduate with the grades you want.

~ ENROL IN THIS FREE TRAINING ~

It's time to say goodbye to procrastination and overwhelm and hello to easier, faster essay writing.

I will never sell your information to third parties and will protect it in accordance with my privacy policy . You may withdraw this consent at any time by unsubscribing.

Add Project Key Words

36 Questions to Ask Yourself Before Writing Your Personal Statement

April 25, 2017

Phase I of Writing Your Personal Statement: 36 Questions to Ask Yourself Before You Begin

In less than 650 words, you have to persuade a stranger to care about you and your application. That’s why the Common App personal statement is one of the most discussed aspects of the college application. Think about how much time you spend on homework, standardized testing, and extracurriculars. This single essay will influence admissions officers as much as these other factors. You could be the perfect applicant, but if your reader doesn’t get to know you and CARE about YOU, you won’t be admitted.

There is no formula for creating the perfect personal statement. The best personal statement topic for your friend might not work well as a topic for you. The topic that might inspire your friend to show his most unique thoughts, the challenges he’s overcome, and the maturity he has gained, might not help you reveal what’s most interesting and compelling about you.

So, how can you write the best possible personal statement for you and your application? Here are the first steps in the process.

1. Start early!

The worst thing you can do is rush the creation of your personal statement. The next two steps below might take weeks...and these occur before you even have a good first draft and can start multiple rounds of edits. You should edit your personal statement multiple times. You should get feedback from as many family members, friends, and teachers as you can.

But, before you get to this stage, you need to choose the perfect topic (and the best Common App essay prompt ) for you .

So, when is the right time to start the process of writing your personal statement ? You should start brainstorming for your personal statement as early as the spring of your junior year and as late as the summer between junior and senior year.

Why shouldn’t I start earlier? A successful personal statement relies on having a strong and mature sense of yourself. It can also rely on your understanding of what you’d like to do in college, what type of college community you’d like to be a part of, and why you care about your education. Starting too soon might mean you need to start over (see step 3) after you really do some soul-searching about college.

There is a lot of thinking and planning that happens before you start writing, so that’s why you should start early. You will complete your best work when you’re not up against a deadline and you’ll be able to start over (again, see step 3) if this is in your best interests.

2. Brainstorm

If you complete this stage of the process with care and attention, you won’t be faced with Step 3. This step in the process helps you pinpoint that perfect topic for you... which won’t be the same perfect topic for someone else.

To start the process of writing your personal statement , ask yourself the series of 36 questions below. These will help generate topics that will be important and meaningful to you. Keep a written list of possible topics you could choose.

- What’s your main academic area of interest?

- Why does this matter to you?

- When did this interest first start to matter to you? Was there a specific event that sparked your interest?

- How did your interest evolve over time?

- Did you ever face a really big challenge in continuing to learn about or study this topic?

- Was this challenge the result of your gender, race, or religion?

- Was this challenge the result of your family’s socio-economic background or the result of the culture of the place you lived?

- Would you still pursue this academic interest if you earned a very small income with your future job in this area?

Activities:

- What’s an extracurricular activity you do that’s incredibly rare?

- What’s an extracurricular activity that has shaped your personality and character?

- Why does this activity matter so much to you?

- When did this activity first start to matter to you? Was there a specific event that sparked your interest?

- How did your interest in and commitment to this activity evolve over time?

- Have you done something with this activity that no one else you know has done?

- Did you ever face a really big challenge in continuing to pursue this activity?

- Was this challenge the result of your family’s socio-economic background?

- Was this challenge the result of the culture of the place you lived?

Life-events:

- Is there something you’ve done or experienced that changed you forever in a positive way?

- How did this event make you more mature, compassionate, self-aware, determined, or strong?

- Is there a day from your life that you reflect on often? Why is this day so memorable to you?

- Are you similar to or different from your parents / siblings? What made you this way?

- When did you feel like you didn’t fit in with a group of people? What made you different than others?

- Is there something (non-academic / extracurricular) that you devote A LOT of time to? Why do you do this?

- What have you done that didn’t earn you praise, attention, or success?

- What makes you feel like your life is meaningful and important to you?

- What is one thing that you would never change about yourself or your life experiences?

Once you’ve created your list of topics, you’ll need to start narrowing them down. For each topic, ask yourself:

- Is this a topic I care about?

- Is this a topic that I’ve cared about for more than 1-2 years?

- Is this a topic I think shows something about my character and personality?

- Is this a topic that shows something impressive and / or unique about my achievements or activities?

- Is this topic memorable to me? Do I think about this fairly often in my life?

- Am I the only student in my high school class who would write about this topic?

- Does this topic show only positive things about my character, maturity, and perspective on life?

- Would I be interested in reading about this topic if someone else wrote about it?

- Could I write 10 pages about this topic (far more than you’ll need to write, of course)?

If the answer to most or all these questions is “yes!” you’ve probably landed on an ideal topic for you! And get started with writing your personal statement !

I talk more about choosing your personal statement topic, as well as some of the best topics and worst topics here:

3. Start over?

Have you already written your 650 words? Ask yourself: is this best possible story I could tell about myself to admissions officers? What does this story show about me? Is there anything that’s negative in this essay? Is there anything that would make me appear privileged, immature, irresponsible, unfriendly, boring, or unmotivated?

One of the best skills you can develop while writing your personal statement is not to be too attached to your writing. Good editors make BIG changes. And sometimes “big change” means starting over from scratch.

I’ll share my story as a cautionary tale. After careful planning, I wrote the first draft of my personal statement during the summer before my senior year of high school. I was really proud of it. I’d developed a (I thought) complicated and literary metaphor throughout the personal statement. I printed it off. I gave it to my dad to read. He read it through once and said, “you should start over from scratch.”

I was shocked and horrified. What about the more than 5 hours I’d spent planning and writing this essay? My dad pointed out to me the ways in which my personal statement didn’t show the most impressive things about me. It was fine. But it wasn’t unique. It wasn’t personal.

Writing your personal statement is a very strategic part of your college application. There are many "bad" topics you should avoid , there are many “good” topics you could choose, but there are a few that are “outstanding” because they bring a new, personal, thoughtful, and insightful angle to your application and your personal story. This is the personal statement you want to write! Your personal statement needs to engage your readers in less than 650 words in a way that convinces them to believe in you. Your admissions officer will need to advocate for you in order for you to be admitted. You want this person on your side.

Ask your family, friends, and teachers to read your personal statement or consider the topic you’ve selected. Do they feel like this piece of writing or this topic shows the person they know and love? Could this topic make a stranger care about you in the way that your family, friends, teachers care about and support you? This is your personal statement topic selection goal!

Tags : common app , common app essay prompts , personal statement for college , writing your personal statement , college application , applying to college , college application essay , common app personal statement , Personal Statement

Schedule a free consultation

to find out how we can help you get accepted.

Introduction

Background on the Course

CO300 as a University Core Course

Short Description of the Course

Course Objectives

General Overview

Alternative Approaches and Assignments

(Possible) Differences between COCC150 and CO300

What CO300 Students Are Like

And You Thought...

Beginning with Critical Reading

Opportunities for Innovation

Portfolio Grading as an Option

Teaching in the computer classroom

Finally. . .

Classroom materials

Audience awareness and rhetorical contexts

Critical thinking and reading

Focusing and narrowing topics

Mid-course, group, and supplemental evaluations

More detailed explanation of Rogerian argument and Toulmin analysis

Policy statements and syllabi

Portfolio explanations, checklists, and postscripts

Presenting evidence and organizing arguments/counter-arguments

Research and documentation

Writing assignment sheets

Assignments for portfolio 1

Assignments for portfolio 2

Assignments for portfolio 3

Workshopping and workshop sheets

On workshopping generally

Workshop sheets for portfolio 1

Workshop sheets for portfolio 2

Workshop sheets for portfolio 3

Workshop sheets for general purposes

Sample materials grouped by instructor

Questions to Ask Yourself as you Revise Your Essay

COACHING + PUBLISHING

FORMATTING + DESIGN

FREELANCE COMMUNITY

Writing a Salable Personal Essay: 5 Key Questions to Ask Yourself

by Amy Paturel | Jun 3, 2015

Even if you’ve spent weeks crafting the perfect personal essay — and friends and family have declared it brilliant, compelling, powerful prose — that doesn’t mean it’s a shoo-in for publication.

On the contrary. Editors have limited space for personal essays , and often the only way to snag that real estate is to touch them with your story.

In 2005, I wrote an essay about coming to terms with my flat breasts and boyish shape. It was rejected five times , but I kept up my relentless pursuit to find a published home and before long, Health Magazine snapped it up. Since that first sale, I’ve continued to publish essays (and get paid!) in print and online pubs including Newsweek, The Los Angeles Times, Spirituality & Health, Parents and Women’s Health.

While I’d like to believe every piece I write is essay gold, the truth is, I never give up on my pursuit of a sale. And that’s more than half the battle when it comes to personal essays.

Think you have a salable piece? Here are five key questions you need to ask yourself:

1. Do I have a great story?

The experience you’re writing about doesn’t have to be life-changing, or even a huge event, but the story should involve some personal transformation. Maybe you survived a pit bull attack, received flowers from a stranger or trashed your wedding dress.

No matter what the event or experience, it should result in you seeing the world differently than you did before. If your story is something your reader may have experienced (like feeling your baby kick for the first time), you have the extra burden of saying something profound, funny or otherwise important, so you’re not revisiting old territory.

2. Is this the right time to tell my story?

If you have an essay that’s relevant to current events or an upcoming holiday, you have a better chance of making a sale.

Due to publication lag time, if you’re going to claim something is newsworthy, it should have happened within the past few weeks. On the plus side, unless you’re dealing with a newspaper, local magazine or weekly news magazine, timing may not be as critical.

If you’re looking for a sale though, it doesn’t hurt to send your essay about your relationship with your mother four to six weeks before Mother’s Day (convert weeks to months if you’re targeting a national newsstand magazine).

3. Does my story have a universal theme?

A salable essay isn’t just about you! Sure, it may start with your experience, your journal entry or memories and eventually the lesson you learned, but the essay is a way of connecting your unique experience to something your reader can relate to .

Bottom line: People don’t want to read about your uterus — or your favorite little black dress — unless it means something to them.

Ask yourself whether your story will touch readers or make them think about an issue differently. Will it motivate them to act (by calling their moms, for example), or change in some way?

Good essays aren’t just about the first time you fell in love; they’re about the first time I fell in love, too. If you can make your readers recall an event or life experience of their own, then you’re on your way to a great essay.

4. Does my story have great characters?

The best essays have identifiable characters. Readers can visualize them, hear them and feel them. They might even recognize the character as someone in their own lives.

Whether you’re painting a picture of your best friend, a lover or a giant stuffed Elmo, your essay should contain vivid characters . And vivid characters create conflict — either within themselves or with those around them — and that promotes change.

In personal essays, the character who changes and evolves is you. So in your essays, strive for conflict, both within yourself and with other characters.

5. Does my story have a clear take-home message?

Write one sentence describing your take home message. If you find that difficult, you might need to re-work your piece.

Once you know what the “take-home message” is, re-read every paragraph in your essay and ask yourself if it supports your point.

It’s tempting to throw in funny anecdotes that are related to your story but don’t apply to the bigger message or theme. Avoid the temptation. After reading your story, readers should be able to clearly state what it’s about. If they can’t, chances are you don’t have a salable piece.

Even if your story has all of these components, you might not make a sale. The truth is, essay markets are dwindling and the real estate for essays is slim.

But writing essays isn’t just about making a sale. The practice is also a journey in self-discovery. It allows you to experience your life events twice — once in reality and the second time on the page.

Think of writing essays as a cathartic exploration of yourself. They’re a form of writing therapy; a method for discovering your own truth; a way to find your true story. These are an essay’s sweetest rewards. The sale is just the frosting.

How have you sold personal essays? Share your stories in the comments!

If you’re interested in learning more tools of the essay-writing trade, sign up for Amy Paturel’s six-week online essay-writing workshop. Her next class begins June 15, 2015. Visit www.amypaturel.com/classes for details. Bonus: TWL readers get a 10-percent discount! Contact [email protected] to sign up at the discounted rate.

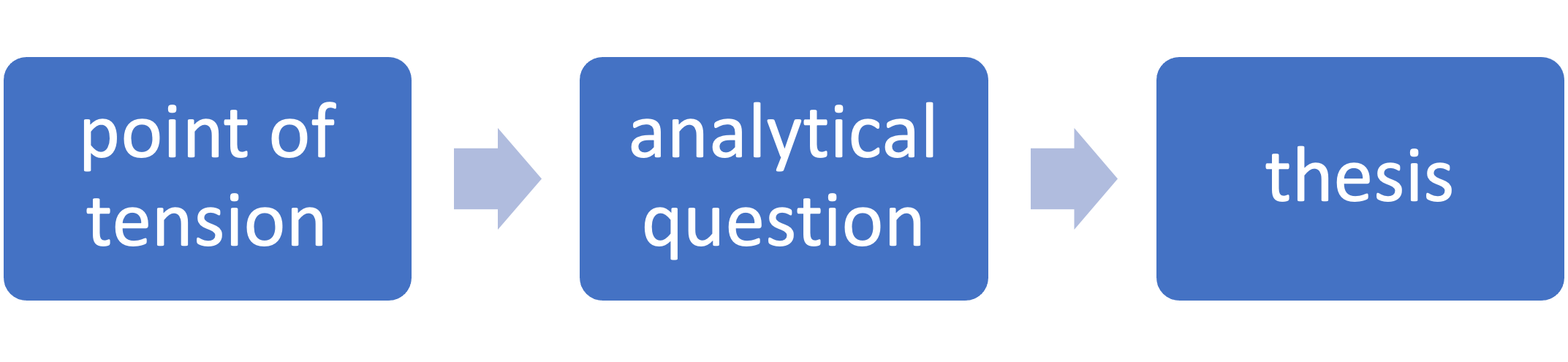

A strong analytical question

- speaks to a genuine dilemma presented by your sources . In other words, the question focuses on a real confusion, problem, ambiguity, or gray area, about which readers will conceivably have different reactions, opinions, or ideas.

- yields an answer that is not obvious . If you ask, "What did this author say about this topic?” there’s nothing to explore because any reader of that text would answer that question in the same way. But if you ask, “how can we reconcile point A and point B in this text,” readers will want to see how you solve that inconsistency in your essay.

- suggests an answer complex enough to require a whole essay's worth of discussion. If the question is too vague, it won't suggest a line of argument. The question should elicit reflection and argument rather than summary or description.

- can be explored using the sources you have available for the assignment , rather than by generalizations or by research beyond the scope of your assignment.

How to come up with an analytical question

One useful starting point when you’re trying to identify an analytical question is to look for points of tension in your sources, either within one source or among sources. It can be helpful to think of those points of tension as the moments where you need to stop and think before you can move forward. Here are some examples of where you may find points of tension:

- You may read a published view that doesn’t seem convincing to you, and you may want to ask a question about what’s missing or about how the evidence might be reconsidered.

- You may notice an inconsistency, gap, or ambiguity in the evidence, and you may want to explore how that changes your understanding of something.

- You may identify an unexpected wrinkle that you think deserves more attention, and you may want to ask a question about it.

- You may notice an unexpected conclusion that you think doesn’t quite add up, and you may want to ask how the authors of a source reached that conclusion.

- You may identify a controversy that you think needs to be addressed, and you may want to ask a question about how it might be resolved.

- You may notice a problem that you think has been ignored, and you may want to try to solve it or consider why it has been ignored.

- You may encounter a piece of evidence that you think warrants a closer look, and you may raise questions about it.

Once you’ve identified a point of tension and raised a question about it, you will try to answer that question in your essay. Your main idea or claim in answer to that question will be your thesis.

- "How" and "why" questions generally require more analysis than "who/ what/when/where” questions.

- Good analytical questions can highlight patterns/connections, or contradictions/dilemmas/problems.

- Good analytical questions establish the scope of an argument, allowing you to focus on a manageable part of a broad topic or a collection of sources.

- Good analytical questions can also address implications or consequences of your analysis.

- picture_as_pdf Asking Analytical Questions

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

11.2: Getting Ready- Questions to Ask Yourself About Your Research Essay

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 6532

- Steven D. Krause

- Eastern Michigan University

If you are coming to this chapter after working through some of the writing exercises in Part Two, “Exercises in the Process of Research,” then you are ready to dive into your research essay. By this point, you probably have done some combination of the following things:

- Thought about different kinds of evidence to support your research;

- Been to the library and the internet to gather evidence;

- Developed an annotated bibliography for your evidence;

- Written and revised a working thesis for your research;

- Critically analyzed and written about key pieces of your evidence;

- Considered the reasons for disagreeing and questioning the premise of your working thesis; and

- Categorized and evaluated your evidence.

In other words, you already have been working on your research essay through the process of research writing.

But before diving into writing a research essay, you need to take a moment to ask yourself, your colleagues, and your teacher some important questions about the nature of your project.

- What is the specific assignment?

It is crucial to consider the teacher’s directions and assignment for your research essay. The teacher’s specific directions will in large part determine what you are required to do to successfully complete your essay, just as they did with the exercises you completed in part two of this book.

If you have been given the option to choose your own research topic, the assignment for the research essay itself might be open-ended. For example:

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\):

Write a research essay about the working thesis that you have been working on with the previous writing assignments. Your essay should be about ten pages long, it should include ample evidence to support your point, and it should follow MLA style.

Some research writing assignments are more specific than this, of course. For example, here is a research writing assignment for a poetry class:

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\):

Write a seven to ten page research essay about one of the poets discussed in the last five chapters of our textbook and his or her poems. Besides your analysis and interpretation of the poems, be sure to cite scholarly research that supports your points. You should also include research on the cultural and historic contexts the poet was working within. Be sure to use MLA documentation style throughout your essay.

Obviously, you probably wouldn’t be able to write a research project about the problems of advertising prescription drugs on television in a History class that focused on the American Revolution.

- What is the main purpose of your research essay?

Has the goal of your essay been to answer specific questions based on assigned reading material and your research? Or has the purpose of your research been more open-ended and abstract, perhaps to learn more about issues and topics to share with a wider audience? In other words, is your research essay supposed to answer questions that indicate that you have learned about a set and defined subject matter (usually a subject matter which your teacher already more or less understands), or is your essay supposed to discover and discuss an issue that is potentially unknown to your audience, including your teacher.

The “demonstrating knowledge about a defined subject matter” purpose for research is quite common in academic writing. For example, a political science professor might ask students to write a research project about the Bill of Rights in order to help her students learn about the Bill of Rights and to demonstrate an understanding of these important amendments to the U.S. Constitution. But presumably, the professor already knows a fair amount the Bill of Rights, which means she is probably more concerned with finding out if you can demonstrate that you have learned and have formed an opinion about the Bill of Rights based on your research and study.

“Discovering and discussing an issue that is potentially unknown to your audience” is also a very common assignment, particularly in composition courses. As the examples included throughout The Process of Research Writing suggest, the subject matter for research essays that are designed to inform your audience about something new is almost unlimited.

Hyperlink: See Chapter 5: The Working Thesis Exercise” and the guidelines for “Working With Assigned Topics” and “Coming Up With a Topic of Your Own Idea.”

Even if all of your classmates have been researching a similar research idea, chances are your particular take on that idea has gone in a different direction. For example, you and some of your classmates might have begun your research by studying the effect on children of violence on television, either because that was a topic assigned by the teacher or because you simply shared an interest in the general topic. But as you have focused and refined this initially broad topic, you and your classmates will inevitably go into different directions, perhaps focusing on different genres (violence in cartoons versus live-action shows), on different age groups (the effect of violent television on pre-schoolers versus the effect on teen-agers), or on different conclusions about the effect of television violence in the first place (it is harmful versus there is no real effect).

- Who is the main audience for your research writing project?

Besides your teacher and your classmates, who are you trying to reach with your research? Who are you trying to convince as a result of the research you have done? What do you think is fair to assume that this audience knows or doesn’t know about the topic of your research project? Purpose and audience are obviously closely related because the reason for writing something has a lot to do with who you are writing it for, and who you are writing something for certainly has a lot to do with your purposes in writing in the first place.

In composition classes, it is usually presumed that your audience includes your teacher and your classmates. After all, one of the most important reasons you are working on this research project in the first place is to meet the requirements of this class, and your teacher and your classmates have been with you as an audience every step of the way.

Contemplating an audience beyond your peers and teachers can sometimes be difficult, but if you have worked through the exercises in Part Two of The Process of Research Writing, you probably have at least some sense of an audience beyond the confines of your class. For example, one of the purposes “Critique Exercise” in Chapter 7 is to explain to your readers why they might be interested in reading the text that you are critiquing. The goal of the “Antithesis Exercise” in Chapter 8 is to consider the position of those who would disagree with the position you are taking. So directly and indirectly, you’ve probably been thinking about your readers for a while now.

Still, it might be useful for you to try to be even more specific about your audience as you begin your research essay. Do you know any “real people” (friends, neighbors, relatives, etc.) who might be an ideal reader for your research essay? Can you at least imagine what an ideal reader might want to get out of reading your research essay?

I’m not trying to suggest that you ought to ignore your teacher and your classmates as your primary audience. But research essays, like most forms of writing, are strongest when they are intended for a more specific audience, either someone the writer knows or someone the writer can imagine. Teachers and classmates are certainly part of this audience, but trying to reach an audience of potential readers beyond the classroom and the assignment will make for a stronger essay.

- What sort of “voice” or “authority” do you think is appropriate for your research project?

Do you want to take on a personal and more casual tone in your writing, or do you want to present a less personal and less casual tone? Do you want to use first person, the “I” pronoun, or do you want to avoid it?

My students are often surprised to learn that it is perfectly acceptable in many types of research and academic writing for writers to use the first person pronoun, “I.” It is the tone I’ve taken with this textbook, and it is an approach that is very common in many fields, particularly those that tend to be grouped under the term “the humanities.

For example, consider this paragraph from Kelly Ritter’s essay “The Economics of Authorship: Online Paper Mills, Student Writers, and First-Year Composition,” which appeared in June 2005 issue of one of the leading journals in the field of composition and rhetoric, College Composition and Communication :

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\):

When considering whether, when, and how often to purchase an academic paper from an online paper-mill site, first-year composition students therefore work with two factors that I wish to investigate here in pursuit of answering the questions posed above: the negligible desire to do one’s own writing, or to be an author, with all that entails in this era of faceless authorship vis-á-vis the Internet; and the ever-shifting concept of “integrity,” or responsibility when purchasing work, particularly in the anonymous arena of online consumerism. (603, emphasis added)

Throughout her thoughtful and well-researched essay, Ritter uses first person pronouns (“I” and “my,” for example) when it is appropriate: “I think,” “I believe,” “my experiences,” etc.

This sort of use of the personal pronoun is not limited to publications in English studies. This example comes from the journal Law and Society Review (Volume 39, Issue 2, 2005), which is an interdisciplinary journal concerned with the connections between society and the law. The article is titled “Preparing to Be Colonized: Land Tenure and Legal Strategy in Nineteenth-Century Hawaii” and it was written by law professor Stuart Banner:

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\):

The story of Hawaii complicates the conventional account of colonial land tenure reform. Why did the land tenure reform movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries receive its earliest implementation in, of all places, Hawaii? Why did the Hawaiians do this to themselves? What did they hope to gain from it? This article attempts to answer these questions. At the end, I briefly suggest why the answers may shed some light on the process of colonization in other times and places, and thus why the answers may be of interest to people who are not historians of Hawaii. (275, emphasis added)

Banner uses both “I” and “my” throughout the article, again when it’s appropriate.

Even this cursory examination of the sort of writing academic writers publish in scholarly journals will demonstrate my point: academic journals routinely publish articles that make use of the first person pronoun. Writers in academic fields that tend to be called “the sciences” (chemistry, biology, physics, and so forth, but also more “soft” sciences like sociology or psychology) are more likely to avoid the personal pronoun or to refer to themselves as “the researcher,” “the author,” or something similar. But even in these fields, “I” does frequently appear.

The point is this: using “I” is not inherently wrong for your research essay or for any other type of academic essay. However, you need to be aware of your choice of first person versus third person and your role as a writer in your research project.

Generally speaking, the use of the first person “I” pronoun creates a greater closeness and informality in your text, which can create a greater sense of intimacy between the writer and the reader. This is the main reason I’ve used “I” in The Process of Research Writing: using the first person pronoun in a textbook like this lessens the distance between us (you as student/reader and me as writer), and I think it makes for easier reading of this material.

If you do decide to use a first person voice in your essay, make sure that the focus stays on your research and does not shift to you the writer. When teachers say “don’t use I,” what they are really cautioning against is the overuse of the word “I” such that the focus of the essay shifts from the research to “you” the writer. While mixing autobiography and research writing can be interesting (as I will touch on in the next chapter on alternatives to the research essay), it is not the approach you want to take in a traditional academic research essay.

The third person pronoun (and avoidance of the use of “I”) tends to have the opposite effect of the first person pronoun: it creates a sense of distance between writer and reader, and it lends a greater formality to the text. This can be useful in research writing because it tends to emphasize research and evidence in order to persuade an audience.

(I should note that much of this textbook is presented in what is called second person voice, using the “you” pronoun. Second person is very effective for writing instructions, but generally speaking, I would discourage you from taking this approach in your research project.)

In other words, “first person” and “third person” are both potentially acceptable choices, depending on the assignment, the main purpose of your assignment, and the audience you are trying to reach. Just be sure to consistent—don’t switch between third person and first person in the same essay.

- What is your working thesis and how has it changed and evolved up to this point?

If you’ve worked through some of the exercises in part two of The Process of Research Writing, you already know how important it is to have an evolving working thesis. If you haven’t read this part of the textbook, you might want to do so before getting too far along with your research project. Chapter Five, “The Working Thesis Exercise,” is an especially important chapter to read and review.

Remember: a working thesis is one that changes and evolves as you write and research. It is perfectly acceptable to change your thesis in the writing process based on your research.

Exercise 10.1

Working alone or in small groups, answer these questions about your research essay before you begin writing it:

- What is the specific research writing assignment? Do you have written instructions from the teacher for this assignment? Are there any details regarding page length, arrangement, or the amount of support evidence that you need to address? In your own words, restate the assignment for the research essay.

- What is the purpose of the research writing assignment? Is the main purpose of your research essay to address specific questions, to provide new information to your audience, or some combination of the two?

- Who is the audience for your research writing assignment? Besides your teacher and classmates, who else might be interested in reading your research essay?

- What sort of voice are you going to use in your research essay? What do you think would be more appropriate for your project, first person or third person?

- What is your working thesis? Think back to the ways you began developing your working thesis in the exercises in part two of The Process of Research Writing. In what ways has your working thesis changed?

If you are working with a small group of classmates, do each of you agree with the basic answers to these questions? Do the answers to these questions spark other questions that you have and need to have answered by your classmates and your teacher before you begin your research writing project?

Once you have some working answers to these basic questions, it’s time to start thinking about actually writing the research essay itself. For most research essay projects, you will have to consider at least most of these components in the process:

- The Formal Outline

- The Introduction

- Background Information

- Evidence to Support Your Points

- Antithetical Arguments and Answers

- The Conclusion

- Works Cited or Reference Information

The rest of this chapter explains these parts of the research essay and it concludes with an example that brings these elements together.

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- Focus and Precision: How to Write Essays that Answer the Question

About the Author Stephanie Allen read Classics and English at St Hugh’s College, Oxford, and is currently researching a PhD in Early Modern Academic Drama at the University of Fribourg.

We’ve all been there. You’ve handed in an essay and you think it’s pretty great: it shows off all your best ideas, and contains points you’re sure no one else will have thought of.

You’re not totally convinced that what you’ve written is relevant to the title you were given – but it’s inventive, original and good. In fact, it might be better than anything that would have responded to the question. But your essay isn’t met with the lavish praise you expected. When it’s tossed back onto your desk, there are huge chunks scored through with red pen, crawling with annotations like little red fire ants: ‘IRRELEVANT’; ‘A bit of a tangent!’; ‘???’; and, right next to your best, most impressive killer point: ‘Right… so?’. The grade your teacher has scrawled at the end is nowhere near what your essay deserves. In fact, it’s pretty average. And the comment at the bottom reads something like, ‘Some good ideas, but you didn’t answer the question!’.

If this has ever happened to you (and it has happened to me, a lot), you’ll know how deeply frustrating it is – and how unfair it can seem. This might just be me, but the exhausting process of researching, having ideas, planning, writing and re-reading makes me steadily more attached to the ideas I have, and the things I’ve managed to put on the page. Each time I scroll back through what I’ve written, or planned, so far, I become steadily more convinced of its brilliance. What started off as a scribbled note in the margin, something extra to think about or to pop in if it could be made to fit the argument, sometimes comes to be backbone of a whole essay – so, when a tutor tells me my inspired paragraph about Ted Hughes’s interpretation of mythology isn’t relevant to my essay on Keats, I fail to see why. Or even if I can see why, the thought of taking it out is wrenching. Who cares if it’s a bit off-topic? It should make my essay stand out, if anything! And an examiner would probably be happy not to read yet another answer that makes exactly the same points. If you recognise yourself in the above, there are two crucial things to realise. The first is that something has to change: because doing well in high school exam or coursework essays is almost totally dependent on being able to pin down and organise lots of ideas so that an examiner can see that they convincingly answer a question. And it’s a real shame to work hard on something, have good ideas, and not get the marks you deserve. Writing a top essay is a very particular and actually quite simple challenge. It’s not actually that important how original you are, how compelling your writing is, how many ideas you get down, or how beautifully you can express yourself (though of course, all these things do have their rightful place). What you’re doing, essentially, is using a limited amount of time and knowledge to really answer a question. It sounds obvious, but a good essay should have the title or question as its focus the whole way through . It should answer it ten times over – in every single paragraph, with every fact or figure. Treat your reader (whether it’s your class teacher or an external examiner) like a child who can’t do any interpretive work of their own; imagine yourself leading them through your essay by the hand, pointing out that you’ve answered the question here , and here , and here. Now, this is all very well, I imagine you objecting, and much easier said than done. But never fear! Structuring an essay that knocks a question on the head is something you can learn to do in a couple of easy steps. In the next few hundred words, I’m going to share with you what I’ve learned through endless, mindless crossings-out, rewordings, rewritings and rethinkings.

Top tips and golden rules

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been told to ‘write the question at the top of every new page’- but for some reason, that trick simply doesn’t work for me. If it doesn’t work for you either, use this three-part process to allow the question to structure your essay:

1) Work out exactly what you’re being asked

It sounds really obvious, but lots of students have trouble answering questions because they don’t take time to figure out exactly what they’re expected to do – instead, they skim-read and then write the essay they want to write. Sussing out a question is a two-part process, and the first part is easy. It means looking at the directions the question provides as to what sort of essay you’re going to write. I call these ‘command phrases’ and will go into more detail about what they mean below. The second part involves identifying key words and phrases.

2) Be as explicit as possible

Use forceful, persuasive language to show how the points you’ve made do answer the question. My main focus so far has been on tangential or irrelevant material – but many students lose marks even though they make great points, because they don’t quite impress how relevant those points are. Again, I’ll talk about how you can do this below.

3) Be brutally honest with yourself about whether a point is relevant before you write it.

It doesn’t matter how impressive, original or interesting it is. It doesn’t matter if you’re panicking, and you can’t think of any points that do answer the question. If a point isn’t relevant, don’t bother with it. It’s a waste of time, and might actually work against you- if you put tangential material in an essay, your reader will struggle to follow the thread of your argument, and lose focus on your really good points.

Put it into action: Step One

Let’s imagine you’re writing an English essay about the role and importance of the three witches in Macbeth . You’re thinking about the different ways in which Shakespeare imagines and presents the witches, how they influence the action of the tragedy, and perhaps the extent to which we’re supposed to believe in them (stay with me – you don’t have to know a single thing about Shakespeare or Macbeth to understand this bit!). Now, you’ll probably have a few good ideas on this topic – and whatever essay you write, you’ll most likely use much of the same material. However, the detail of the phrasing of the question will significantly affect the way you write your essay. You would draw on similar material to address the following questions: Discuss Shakespeare’s representation of the three witches in Macbeth . How does Shakespeare figure the supernatural in Macbeth ? To what extent are the three witches responsible for Macbeth’s tragic downfall? Evaluate the importance of the three witches in bringing about Macbeth’s ruin. Are we supposed to believe in the three witches in Macbeth ? “Within Macbeth ’s representation of the witches, there is profound ambiguity about the actual significance and power of their malevolent intervention” (Stephen Greenblatt). Discuss. I’ve organised the examples into three groups, exemplifying the different types of questions you might have to answer in an exam. The first group are pretty open-ended: ‘discuss’- and ‘how’-questions leave you room to set the scope of the essay. You can decide what the focus should be. Beware, though – this doesn’t mean you don’t need a sturdy structure, or a clear argument, both of which should always be present in an essay. The second group are asking you to evaluate, constructing an argument that decides whether, and how far something is true. Good examples of hypotheses (which your essay would set out to prove) for these questions are:

- The witches are the most important cause of tragic action in Macbeth.

- The witches are partially, but not entirely responsible for Macbeth’s downfall, alongside Macbeth’s unbridled ambition, and that of his wife.

- We are not supposed to believe the witches: they are a product of Macbeth’s psyche, and his downfall is his own doing.

- The witches’ role in Macbeth’s downfall is deliberately unclear. Their claim to reality is shaky – finally, their ambiguity is part of an uncertain tragic universe and the great illusion of the theatre. (N.B. It’s fine to conclude that a question can’t be answered in black and white, certain terms – as long as you have a firm structure, and keep referring back to it throughout the essay).

The final question asks you to respond to a quotation. Students tend to find these sorts of questions the most difficult to answer, but once you’ve got the hang of them I think the title does most of the work for you – often implicitly providing you with a structure for your essay. The first step is breaking down the quotation into its constituent parts- the different things it says. I use brackets: ( Within Macbeth ’s representation of the witches, ) ( there is profound ambiguity ) about the ( actual significance ) ( and power ) of ( their malevolent intervention ) Examiners have a nasty habit of picking the most bewildering and terrifying-sounding quotations: but once you break them down, they’re often asking for something very simple. This quotation, for example, is asking exactly the same thing as the other questions. The trick here is making sure you respond to all the different parts. You want to make sure you discuss the following:

- Do you agree that the status of the witches’ ‘malevolent intervention’ is ambiguous?

- What is its significance?

- How powerful is it?

Step Two: Plan

Having worked out exactly what the question is asking, write out a plan (which should be very detailed in a coursework essay, but doesn’t have to be more than a few lines long in an exam context) of the material you’ll use in each paragraph. Make sure your plan contains a sentence at the end of each point about how that point will answer the question. A point from my plan for one of the topics above might look something like this:

To what extent are we supposed to believe in the three witches in Macbeth ? Hypothesis: The witches’ role in Macbeth’s downfall is deliberately unclear. Their claim to reality is uncertain – finally, they’re part of an uncertain tragic universe and the great illusion of the theatre. Para.1: Context At the time Shakespeare wrote Macbeth , there were many examples of people being burned or drowned as witches There were also people who claimed to be able to exorcise evil demons from people who were ‘possessed’. Catholic Christianity leaves much room for the supernatural to exist This suggests that Shakespeare’s contemporary audience might, more readily than a modern one, have believed that witches were a real phenomenon and did exist.

My final sentence (highlighted in red) shows how the material discussed in the paragraph answers the question. Writing this out at the planning stage, in addition to clarifying your ideas, is a great test of whether a point is relevant: if you struggle to write the sentence, and make the connection to the question and larger argument, you might have gone off-topic.

Step Three: Paragraph beginnings and endings

The final step to making sure you pick up all the possible marks for ‘answering the question’ in an essay is ensuring that you make it explicit how your material does so. This bit relies upon getting the beginnings and endings of paragraphs just right. To reiterate what I said above, treat your reader like a child: tell them what you’re going to say; tell them how it answers the question; say it, and then tell them how you’ve answered the question. This need not feel clumsy, awkward or repetitive. The first sentence of each new paragraph or point should, without giving too much of your conclusion away, establish what you’re going to discuss, and how it answers the question. The opening sentence from the paragraph I planned above might go something like this:

Early modern political and religious contexts suggest that Shakespeare’s contemporary audience might more readily have believed in witches than his modern readers.

The sentence establishes that I’m going to discuss Jacobean religion and witch-burnings, and also what I’m going to use those contexts to show. I’d then slot in all my facts and examples in the middle of the paragraph. The final sentence (or few sentences) should be strong and decisive, making a clear connection to the question you’ve been asked:

Contemporary suspicion that witches did exist, testified to by witch-hunts and exorcisms, is crucial to our understanding of the witches in Macbeth. To the early modern consciousness, witches were a distinctly real and dangerous possibility – and the witches in the play would have seemed all-the-more potent and terrifying as a result.

Step Four: Practice makes perfect

The best way to get really good at making sure you always ‘answer the question’ is to write essay plans rather than whole pieces. Set aside a few hours, choose a couple of essay questions from past papers, and for each:

- Write a hypothesis

- Write a rough plan of what each paragraph will contain

- Write out the first and last sentence of each paragraph

You can get your teacher, or a friend, to look through your plans and give you feedback . If you follow this advice, fingers crossed, next time you hand in an essay, it’ll be free from red-inked comments about irrelevance, and instead showered with praise for the precision with which you handled the topic, and how intently you focused on answering the question. It can seem depressing when your perfect question is just a minor tangent from the question you were actually asked, but trust me – high praise and good marks are all found in answering the question in front of you, not the one you would have liked to see. Teachers do choose the questions they set you with some care, after all; chances are the question you were set is the more illuminating and rewarding one as well.

Image credits: banner ; Keats ; Macbeth ; James I ; witches .

Comments are closed.

- Educational Assessment

Good Questions for Better Essay Prompts (and Papers)

- April 8, 2020

- Jessica McCaughey

Most professors would admit that they’ve found themselves frustrated when grading papers. Yes, sometimes those frustrations might stem from students ignoring your clear, strategic, and explicit instructions, but more often, I’d argue, “bad” papers are a result of how and what we’re asking of students, and how well we really understand our goals for them. Further, we often struggle to strike a balance between providing too much information and too little, and placing ourselves in a novice’s shoes is difficult. In an effort to combat these challenges, I present a series of questions to ask yourself as you begin developing or revising prompts.

1. What do you want your students to learn or demonstrate through this writing assignment? Is an essay the best way reach these goals? If so, do they understand those learning goals? Assigning an essay is, for many instructors, our go-to. But paper writing isn’t always the best assessment tool. Think hard about what it is you’re hoping for your students to take away from an assignment. Are there other, better forms the assignment might take? And if the answer is a resounding, “This paper is the right venue!” you should consider whether you are explicitly conveying to your students why you’re asking them to do certain work. Transparency benefits them tremendously. Transparent assignment design—being explicit about how and why you are facilitating their learning in the ways that you are—helps all students, but it particularly helps those students who may not have the experience, networks, or models in college that other students have, such as first-generation college students, minorities, or students with disabilities. Whether in class discussion or in the written prompt itself, strive to follow these transparent assignment design principles . 2. Who is the audience (real or imagined) for the assignment, and what is the purpose of the text? For most writing assignments, the “audience” is, of course, the instructor, and students strive to meet that instructor’s expectations, even if they’re guessing about what this instructor knows, wants, and expects.Even assignments as specific as “Write a letter to the Editor on X topic” beg for more detail. (Is this for my hometown paper or the New York Times ? Those letters will of course read very differently.) And when it comes to purpose or goals, while it might seem obvious to you what the purpose of this paper is, it might not be to your students. Work to be as explicit as possible as you can in what you’d like them to achieve in their paper. You might use language such as, “In this paper you are writing to an audience of scholars in X field, who are/are not familiar with your topic,” or “Your overarching purpose in this paper is to persuade your reader towards a specific, implementable solution to the problem at hand, and support your argument with scholarship in the field.”

3. Do you want to read their papers? This question may seem silly, but it’s not. In every field, professors have the capacity to set students up for authentic, engaging assignments. If you don’t feel excited to read the paper, you can likely imagine how difficult it will be for students to engage in the much more substantial process of writing it. So, consider retooling the assignment into something you look forward to spending time reading. Might you consider new genres, audiences, or purposes for their writing? Develop a traditional essay into a problem-solving task ?

4. What does good writing look like in your field? How can you convey this to students? We all know what good writing looks like in our fields, but students sometimes don’t even understand that writing forms, expectations, and conventions vary from discipline to discipline. Whether we like it or not, and whether we think we have time for it or not, it is our job to teach students about texts in our specific disciplines. Maybe that includes offering them annotated sample papers. Maybe this happens over a series of beginning-of-class conversations as they’re drafting. Maybe it’s showing them some of your own work or looking closely at the writing in a flagship journal. Regardless of how you do it, be sure that a part of the writing process for your students includes exposure and at least an introductory understanding to what “good” writing is to you and your field.

5. Are your grading criteria clear—and thoughtful and reasonable? We know that clear grading criteria—whether in the form of a rubric or a narrative—is key to student writer success, but it’s not as simple as assignment weights to columns such as “Grammar” and “Thesis.” In order to think deeply about how we’re grading, we also have to interrogate what assumptions we have about our student writers? What do we think they already know? Why do we think this? What do we prioritize in an essay, and more importantly, why is that the priority? Do our priorities align with our learning goals for students? These answers to these questions too should be transparent to students as they embark on your writing assignments.

6. What support and structure are you able to provide? Traci Gardner’s Designing Writing Assignments illustrates that the kinds of prompts that allow students to write strong papers share certain characteristics, and among the most important is providing support, both materially and in their process (35). How are you going to facilitate the writing that you want to see your students develop and showcase it in your prompt? Can the assignment be broken down into smaller, scaffolded steps? Or, if you want the students to practice managing projects and figure this out themselves, how can you serve as a guide as they work through time and resource management in order to do so? As scholars, we are not expected to create excellent work without feedback, and we shouldn’t expect it of our students either. We’re not only teaching content and, as noted above, what writing looks like in our discipline, but we’re also working to instill a writing process. Before assigning a paper, be clear about how you’ll build in steps, support, and this process of feedback and revision into your assignment.

7. Does it make sense for this particular assignment and your particular class to include a reflective element? Research shows that metacognition and reflection aid in the transfer of knowledge and skills , so building in some way for students to reflect on the writing and learning they’ve done through your assignment is a valuable way to help them take that knowledge forward, into other classrooms and, later, the workplace. 8. How can you go through the writing process yourself to create the most productive possible prompt? Ask for feedback from colleagues—or your students! There’s no shame in showing students a prompt and revising it based on their questions, perceptions, and, after the semester ends to benefit your next class, their writing.

Bio: Jessica McCaughey is an assistant professor in the University Writing Program at George Washington University , where she teaches academic and professional writing. In this role, Professor McCaughey has developed a growing professional writing program consisting of workshops, assessment, and coaching that helps organizations improve the quality of their employees’ professional and technical writing. In 2016, she was nominated for the Columbian College’s Robert W. Kenny Prize for Innovation in Teaching of Introductory Courses, and in 2017, she won the Conference on College Composition and Communication’s Emergent Researcher Award.

References:

Elon Statement on Writing Transfer. (29 July 2013). Retrieved from http://www.elon.edu/ e-web/academics/teaching/ers/writing_transfer/statement.xhtml

Gardner, Traci. (2008). Designing Writing Assignments . National Council of Teachers of English. https://wac.colostate.edu/books/gardner/

- Jessica McCaughey is an assistant professor in the University Writing Program at George Washington University, where she teaches academic and professional writing. In this role, Professor McCaughey has developed a growing professional writing program consisting of workshops, assessment, and coaching that helps organizations improve the quality of their employees’ professional and technical writing. In 2016, she was nominated for the Columbian College’s Robert W. Kenny Prize for Innovation in Teaching of Introductory Courses, and in 2017, she won the Conference on College Composition and Communication’s Emergent Researcher Award.

Stay Updated with Faculty Focus!

Get exclusive access to programs, reports, podcast episodes, articles, and more!

- Opens in a new tab

Welcome Back

Username or Email

Remember Me

Already a subscriber? log in here.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

19.2 Getting Ready: Questions to Ask Yourself About Your Research Essay

If you are coming to this chapter after working through some of the earlier chapters in this book, then you are ready to dive into your research essay. By this point, you probably have done some combination of the following things:

- Thought about different kinds of evidence to support your research;

- Been to the library and/or the internet to gather evidence;

- Developed an annotated bibliography for your evidence;

- Written and revised a working thesis for your research;

- Critically analyzed and written about key pieces of your evidence;

- Considered the reasons for disagreeing with and/or questioning the premise of your working thesis;

- Categorized and evaluated your evidence.

In other words, you already have been working on your research essay through the process of researched writing.

But before diving into writing a research essay, you need to take a moment to ask yourself, your peers, and your teacher some important questions about the nature of your project.

What is the specific assignment?

It is crucial to consider the teacher’s directions and assignment for your research essay. The teacher’s specific directions will in large part determine what you are required to do to successfully complete your essay. They may specify how many sources you need to consult, how your essay should be organized, and how long it should be. The directions may even determine your topic. If you have been given the option to choose your own research topic, the assignment for the research essay itself might be open-ended. Alternatively, your instructor may have assigned you a topic to write about.

What is the main purpose of your research essay?

Has the goal of your essay been to answer specific questions based on assigned reading material and your research? Or has the purpose of your research been more open-ended and abstract, perhaps to learn more about issues and topics to share with a wider audience? In other words, is your research essay supposed to answer questions that indicate that you have learned about specific subject matter (usually a topic that your teacher already more or less understands), or is your essay supposed to discover and discuss an issue that is potentially unknown to your audience, including your teacher?

The “demonstrating knowledge about a specific topic” purpose for research is quite common in academic writing. For example, a political science professor might ask students to write a research project about the Bill of Rights in order to help her students learn about the Bill of Rights and to demonstrate an understanding of these important amendments to the U.S. Constitution. But presumably, the professor already knows a fair amount the Bill of Rights, which means she is probably more concerned with finding out if you can demonstrate that you have learned and have formed an opinion about the Bill of Rights based on your research and study.

“Discovering and discussing an issue that is potentially unknown to your audience” is also a very common assignment, particularly in composition courses. As the examples included throughout this chapter suggest, the subject matter for research essays that are designed to inform your audience about something new is almost unlimited.

How do you select a topic?

If your instructor allows you free choice of topics, the choices can be almost overwhelming. How do you narrow the task to something that interests you, is manageable, and that has enough sources in the library or online to sustain an engaging argument? The best place to start looking for a research project topic is to examine your own interests, passions, and hobbies. What topics, events, people, or natural phenomena, or stories interest, concern you, or make you passionate? What have you always wanted to find out more about or explore in more depth?

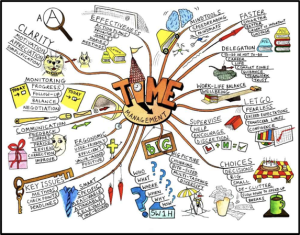

To narrow the focus of your topic, you may try freewriting exercises, such as mindmapping or brainstorming. As the example below suggests, you can create a map with both images and text, which are related to branches centered on the main focus, “time management.” Based on this kind of mindmap, you have to narrow down or choose specific parts of your ideas instead of including all the ideas and topics that you had during the mindmapping process. You simultaneously want to ask a question–a broad, open-ended question that will guide your research. It is not necessary to propose a possible answer or working thesis at this stage, but you can speculate about a kind of argument that you can build through research. You may use your research question and working thesis to create a research proposal. For this part of writing, see “ Identifying Issues for Research .”

Looking into the storehouse of your knowledge and life experiences will allow you to choose a topic for your research project in which you are genuinely interested and in which you will be willing to invest plenty of time, effort, and enthusiasm. Simultaneously with being interesting and important to you, your research topic should, of course, interest your readers. As you have learned from the chapter on rhetoric, writers always write with a purpose and for a specific audience.

Therefore, whatever topic you choose and whatever argument you will build about it through research should provoke a response in your readers. And while almost any topic can be treated in an original and interesting way, simply choosing the topic that interests you, the writer, is not, in itself, a guarantee of success of your research project.

Here is some advice on how to select a promising topic for your next research project. As you think about possible topics for your paper, remember that writing is a conversation between you and your readers. Whatever subject you choose to explore and write about has to be something that is interesting and important to them as well as to you.

When selecting topics for research, consider the following factors:

- Your existing knowledge about the topic

- What else you need or want to find out about the topic

- What questions about the topic (or what aspects of it) are important not only for you but for others around you

- Resources (libraries, internet access, primary research sources, and so on) available to you in order to conduct a high quality investigation of your topic.

Read about and “around” various topics that interest you. As we argue later on in this chapter, reading is a powerful invention tool capable of teasing out subjects, questions, and ideas which would not have come to mind otherwise. Reading also allows you to find out what questions, problems, and ideas are circulating among your potential readers, thus enabling you to better and more quickly enter the conversation with those readers through research and writing.

If you have an idea of the topic or issue you want to study, try asking the following questions

- Why do I care about this topic?

- What do I already know or believe about this topic?

- How did I receive my knowledge or beliefs (personal experiences, stories of others, reading, and so on)?

- What do I want to find out about this topic?

- Who else cares about or is affected by this topic? In what ways and why?

- What do I know about the kinds of things that my potential readers might want to learn about it?

- Where do my interests about the topic intersect with my readers’ potential interests, and where they do not?

- Which topic or topics have the most potential to interest not only you, the writer, but also your readers?

Let’s practice how to select a topic and how to narrow down a scope for a research paper within a reasonable timeline. Suppose that, in one first-year seminar on Sociology, you are assigned to write a research-based argumentative essay on social media and privacy.

- Start a free writing or draw a mindmap in relation to the two key terms: social media and privacy. What words come to your mind? How would you relate them to the key terms or to one another? What questions do you have? Write and/or draw them down.

- Examine your initial thoughts. What part of your free writing or mindmap particularly attracts your attention and why? As if you have a magnifying glass, let’s zoom in that part. What specific topics do you like to have under the umbrella of social media and privacy? What would you argue about them?

- List what kinds of information and studies you may need to delve into these topics for an argument.

- Consider where you can find them including campus and local libraries, databases, and other digitally open sources.

- Assume that you have two weeks to complete a five-page research essay. Then, how would you plan a research and writing schedule to meet the deadline? By considering the steps above, make a timeline for the project.

- Compare your timeline with those of your classmates, and exchange each other’s rationales of timelines. Why do they look alike or different? How are the timelines realistic or ideal? After the discussion, if you’d like to revise your schedule for the research and writing, what compels you to reconsider the initial plan?

Continue Reading: 19.3 Planning Your Research

Composition for Commodores Copyright © 2023 by Mollie Chambers; Karin Hooks; Donna Hunt; Kim Karshner; Josh Kesterson; Geoff Polk; Amy Scott-Douglass; Justin Sevenker; Jewon Woo; and other LCCC Faculty is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The Personal Statement: Questions to Ask Before Writing

Written by Lisa Bleich.

As we meet with our clients to brainstorm for their personal statements (or college essays), it reminds us how much we enjoy delving into the depths of our clients and helping them think about how best to tell their story. We are always amazed by their unique experiences and how they approach their lives differently depending on their interests or background.

However, it is also the most challenging part of the application process for most students. Up until now the bulk of their writing has been in the form of a non-fiction, analytical essay about a book they read or a history paper. Many struggle with what they should write about because they don’t know exactly what they want to communicate. And for those 17 year olds who know what they want to write about, very few know how to tell it in a compelling, interesting way. The personal statement must not only be compelling and interesting, but it should also convey the writer’s voice and personality in approximately 650 words.