Advertisement

- Previous Issue

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Clarifying the Research Purpose

Methodology, measurement, data analysis and interpretation, tools for evaluating the quality of medical education research, research support, competing interests, quantitative research methods in medical education.

Submitted for publication January 8, 2018. Accepted for publication November 29, 2018.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

- Search Site

John T. Ratelle , Adam P. Sawatsky , Thomas J. Beckman; Quantitative Research Methods in Medical Education. Anesthesiology 2019; 131:23–35 doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000002727

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

There has been a dramatic growth of scholarly articles in medical education in recent years. Evaluating medical education research requires specific orientation to issues related to format and content. Our goal is to review the quantitative aspects of research in medical education so that clinicians may understand these articles with respect to framing the study, recognizing methodologic issues, and utilizing instruments for evaluating the quality of medical education research. This review can be used both as a tool when appraising medical education research articles and as a primer for clinicians interested in pursuing scholarship in medical education.

Image: J. P. Rathmell and Terri Navarette.

There has been an explosion of research in the field of medical education. A search of PubMed demonstrates that more than 40,000 articles have been indexed under the medical subject heading “Medical Education” since 2010, which is more than the total number of articles indexed under this heading in the 1980s and 1990s combined. Keeping up to date requires that practicing clinicians have the skills to interpret and appraise the quality of research articles, especially when serving as editors, reviewers, and consumers of the literature.

While medical education shares many characteristics with other biomedical fields, substantial particularities exist. We recognize that practicing clinicians may not be familiar with the nuances of education research and how to assess its quality. Therefore, our purpose is to provide a review of quantitative research methodologies in medical education. Specifically, we describe a structure that can be used when conducting or evaluating medical education research articles.

Clarifying the research purpose is an essential first step when reading or conducting scholarship in medical education. 1 Medical education research can serve a variety of purposes, from advancing the science of learning to improving the outcomes of medical trainees and the patients they care for. However, a well-designed study has limited value if it addresses vague, redundant, or unimportant medical education research questions.

What is the research topic and why is it important? What is unknown about the research topic? Why is further research necessary?

What is the conceptual framework being used to approach the study?

What is the statement of study intent?

What are the research methodology and study design? Are they appropriate for the study objective(s)?

Which threats to internal validity are most relevant for the study?

What is the outcome and how was it measured?

Can the results be trusted? What is the validity and reliability of the measurements?

How were research subjects selected? Is the research sample representative of the target population?

Was the data analysis appropriate for the study design and type of data?

What is the effect size? Do the results have educational significance?

Fortunately, there are steps to ensure that the purpose of a research study is clear and logical. Table 1 2–5 outlines these steps, which will be described in detail in the following sections. We describe these elements not as a simple “checklist,” but as an advanced organizer that can be used to understand a medical education research study. These steps can also be used by clinician educators who are new to the field of education research and who wish to conduct scholarship in medical education.

Steps in Clarifying the Purpose of a Research Study in Medical Education

Literature Review and Problem Statement

A literature review is the first step in clarifying the purpose of a medical education research article. 2 , 5 , 6 When conducting scholarship in medical education, a literature review helps researchers develop an understanding of their topic of interest. This understanding includes both existing knowledge about the topic as well as key gaps in the literature, which aids the researcher in refining their study question. Additionally, a literature review helps researchers identify conceptual frameworks that have been used to approach the research topic. 2

When reading scholarship in medical education, a successful literature review provides background information so that even someone unfamiliar with the research topic can understand the rationale for the study. Located in the introduction of the manuscript, the literature review guides the reader through what is already known in a manner that highlights the importance of the research topic. The literature review should also identify key gaps in the literature so the reader can understand the need for further research. This gap description includes an explicit problem statement that summarizes the important issues and provides a reason for the study. 2 , 4 The following is one example of a problem statement:

“Identifying gaps in the competency of anesthesia residents in time for intervention is critical to patient safety and an effective learning system… [However], few available instruments relate to complex behavioral performance or provide descriptors…that could inform subsequent feedback, individualized teaching, remediation, and curriculum revision.” 7

This problem statement articulates the research topic (identifying resident performance gaps), why it is important (to intervene for the sake of learning and patient safety), and current gaps in the literature (few tools are available to assess resident performance). The researchers have now underscored why further research is needed and have helped readers anticipate the overarching goals of their study (to develop an instrument to measure anesthesiology resident performance). 4

The Conceptual Framework

Following the literature review and articulation of the problem statement, the next step in clarifying the research purpose is to select a conceptual framework that can be applied to the research topic. Conceptual frameworks are “ways of thinking about a problem or a study, or ways of representing how complex things work.” 3 Just as clinical trials are informed by basic science research in the laboratory, conceptual frameworks often serve as the “basic science” that informs scholarship in medical education. At a fundamental level, conceptual frameworks provide a structured approach to solving the problem identified in the problem statement.

Conceptual frameworks may take the form of theories, principles, or models that help to explain the research problem by identifying its essential variables or elements. Alternatively, conceptual frameworks may represent evidence-based best practices that researchers can apply to an issue identified in the problem statement. 3 Importantly, there is no single best conceptual framework for a particular research topic, although the choice of a conceptual framework is often informed by the literature review and knowing which conceptual frameworks have been used in similar research. 8 For further information on selecting a conceptual framework for research in medical education, we direct readers to the work of Bordage 3 and Irby et al. 9

To illustrate how different conceptual frameworks can be applied to a research problem, suppose you encounter a study to reduce the frequency of communication errors among anesthesiology residents during day-to-night handoff. Table 2 10 , 11 identifies two different conceptual frameworks researchers might use to approach the task. The first framework, cognitive load theory, has been proposed as a conceptual framework to identify potential variables that may lead to handoff errors. 12 Specifically, cognitive load theory identifies the three factors that affect short-term memory and thus may lead to communication errors:

Conceptual Frameworks to Address the Issue of Handoff Errors in the Intensive Care Unit

Intrinsic load: Inherent complexity or difficulty of the information the resident is trying to learn ( e.g. , complex patients).

Extraneous load: Distractions or demands on short-term memory that are not related to the information the resident is trying to learn ( e.g. , background noise, interruptions).

Germane load: Effort or mental strategies used by the resident to organize and understand the information he/she is trying to learn ( e.g. , teach back, note taking).

Using cognitive load theory as a conceptual framework, researchers may design an intervention to reduce extraneous load and help the resident remember the overnight to-do’s. An example might be dedicated, pager-free handoff times where distractions are minimized.

The second framework identified in table 2 , the I-PASS (Illness severity, Patient summary, Action list, Situational awareness and contingency planning, and Synthesis by receiver) handoff mnemonic, 11 is an evidence-based best practice that, when incorporated as part of a handoff bundle, has been shown to reduce handoff errors on pediatric wards. 13 Researchers choosing this conceptual framework may adapt some or all of the I-PASS elements for resident handoffs in the intensive care unit.

Note that both of the conceptual frameworks outlined above provide researchers with a structured approach to addressing the issue of handoff errors; one is not necessarily better than the other. Indeed, it is possible for researchers to use both frameworks when designing their study. Ultimately, we provide this example to demonstrate the necessity of selecting conceptual frameworks to clarify the research purpose. 3 , 8 Readers should look for conceptual frameworks in the introduction section and should be wary of their omission, as commonly seen in less well-developed medical education research articles. 14

Statement of Study Intent

After reviewing the literature, articulating the problem statement, and selecting a conceptual framework to address the research topic, the final step in clarifying the research purpose is the statement of study intent. The statement of study intent is arguably the most important element of framing the study because it makes the research purpose explicit. 2 Consider the following example:

This study aimed to test the hypothesis that the introduction of the BASIC Examination was associated with an accelerated knowledge acquisition during residency training, as measured by increments in annual ITE scores. 15

This statement of study intent succinctly identifies several key study elements including the population (anesthesiology residents), the intervention/independent variable (introduction of the BASIC Examination), the outcome/dependent variable (knowledge acquisition, as measure by in In-training Examination [ITE] scores), and the hypothesized relationship between the independent and dependent variable (the authors hypothesize a positive correlation between the BASIC examination and the speed of knowledge acquisition). 6 , 14

The statement of study intent will sometimes manifest as a research objective, rather than hypothesis or question. In such instances there may not be explicit independent and dependent variables, but the study population and research aim should be clearly identified. The following is an example:

“In this report, we present the results of 3 [years] of course data with respect to the practice improvements proposed by participating anesthesiologists and their success in implementing those plans. Specifically, our primary aim is to assess the frequency and type of improvements that were completed and any factors that influence completion.” 16

The statement of study intent is the logical culmination of the literature review, problem statement, and conceptual framework, and is a transition point between the Introduction and Methods sections of a medical education research report. Nonetheless, a systematic review of experimental research in medical education demonstrated that statements of study intent are absent in the majority of articles. 14 When reading a medical education research article where the statement of study intent is absent, it may be necessary to infer the research aim by gathering information from the Introduction and Methods sections. In these cases, it can be useful to identify the following key elements 6 , 14 , 17 :

Population of interest/type of learner ( e.g. , pain medicine fellow or anesthesiology residents)

Independent/predictor variable ( e.g. , educational intervention or characteristic of the learners)

Dependent/outcome variable ( e.g. , intubation skills or knowledge of anesthetic agents)

Relationship between the variables ( e.g. , “improve” or “mitigate”)

Occasionally, it may be difficult to differentiate the independent study variable from the dependent study variable. 17 For example, consider a study aiming to measure the relationship between burnout and personal debt among anesthesiology residents. Do the researchers believe burnout might lead to high personal debt, or that high personal debt may lead to burnout? This “chicken or egg” conundrum reinforces the importance of the conceptual framework which, if present, should serve as an explanation or rationale for the predicted relationship between study variables.

Research methodology is the “…design or plan that shapes the methods to be used in a study.” 1 Essentially, methodology is the general strategy for answering a research question, whereas methods are the specific steps and techniques that are used to collect data and implement the strategy. Our objective here is to provide an overview of quantitative methodologies ( i.e. , approaches) in medical education research.

The choice of research methodology is made by balancing the approach that best answers the research question against the feasibility of completing the study. There is no perfect methodology because each has its own potential caveats, flaws and/or sources of bias. Before delving into an overview of the methodologies, it is important to highlight common sources of bias in education research. We use the term internal validity to describe the degree to which the findings of a research study represent “the truth,” as opposed to some alternative hypothesis or variables. 18 Table 3 18–20 provides a list of common threats to internal validity in medical education research, along with tactics to mitigate these threats.

Threats to Internal Validity and Strategies to Mitigate Their Effects

Experimental Research

The fundamental tenet of experimental research is the manipulation of an independent or experimental variable to measure its effect on a dependent or outcome variable.

True Experiment

True experimental study designs minimize threats to internal validity by randomizing study subjects to experimental and control groups. Through ensuring that differences between groups are—beyond the intervention/variable of interest—purely due to chance, researchers reduce the internal validity threats related to subject characteristics, time-related maturation, and regression to the mean. 18 , 19

Quasi-experiment

There are many instances in medical education where randomization may not be feasible or ethical. For instance, researchers wanting to test the effect of a new curriculum among medical students may not be able to randomize learners due to competing curricular obligations and schedules. In these cases, researchers may be forced to assign subjects to experimental and control groups based upon some other criterion beyond randomization, such as different classrooms or different sections of the same course. This process, called quasi-randomization, does not inherently lead to internal validity threats, as long as research investigators are mindful of measuring and controlling for extraneous variables between study groups. 19

Single-group Methodologies

All experimental study designs compare two or more groups: experimental and control. A common experimental study design in medical education research is the single-group pretest–posttest design, which compares a group of learners before and after the implementation of an intervention. 21 In essence, a single-group pre–post design compares an experimental group ( i.e. , postintervention) to a “no-intervention” control group ( i.e. , preintervention). 19 This study design is problematic for several reasons. Consider the following hypothetical example: A research article reports the effects of a year-long intubation curriculum for first-year anesthesiology residents. All residents participate in monthly, half-day workshops over the course of an academic year. The article reports a positive effect on residents’ skills as demonstrated by a significant improvement in intubation success rates at the end of the year when compared to the beginning.

This study does little to advance the science of learning among anesthesiology residents. While this hypothetical report demonstrates an improvement in residents’ intubation success before versus after the intervention, it does not tell why the workshop worked, how it compares to other educational interventions, or how it fits in to the broader picture of anesthesia training.

Single-group pre–post study designs open themselves to a myriad of threats to internal validity. 20 In our hypothetical example, the improvement in residents’ intubation skills may have been due to other educational experience(s) ( i.e. , implementation threat) and/or improvement in manual dexterity that occurred naturally with time ( i.e. , maturation threat), rather than the airway curriculum. Consequently, single-group pre–post studies should be interpreted with caution. 18

Repeated testing, before and after the intervention, is one strategy that can be used to reduce the some of the inherent limitations of the single-group study design. Repeated pretesting can mitigate the effect of regression toward the mean, a statistical phenomenon whereby low pretest scores tend to move closer to the mean on subsequent testing (regardless of intervention). 20 Likewise, repeated posttesting at multiple time intervals can provide potentially useful information about the short- and long-term effects of an intervention ( e.g. , the “durability” of the gain in knowledge, skill, or attitude).

Observational Research

Unlike experimental studies, observational research does not involve manipulation of any variables. These studies often involve measuring associations, developing psychometric instruments, or conducting surveys.

Association Research

Association research seeks to identify relationships between two or more variables within a group or groups (correlational research), or similarities/differences between two or more existing groups (causal–comparative research). For example, correlational research might seek to measure the relationship between burnout and educational debt among anesthesiology residents, while causal–comparative research may seek to measure differences in educational debt and/or burnout between anesthesiology and surgery residents. Notably, association research may identify relationships between variables, but does not necessarily support a causal relationship between them.

Psychometric and Survey Research

Psychometric instruments measure a psychologic or cognitive construct such as knowledge, satisfaction, beliefs, and symptoms. Surveys are one type of psychometric instrument, but many other types exist, such as evaluations of direct observation, written examinations, or screening tools. 22 Psychometric instruments are ubiquitous in medical education research and can be used to describe a trait within a study population ( e.g. , rates of depression among medical students) or to measure associations between study variables ( e.g. , association between depression and board scores among medical students).

Psychometric and survey research studies are prone to the internal validity threats listed in table 3 , particularly those relating to mortality, location, and instrumentation. 18 Additionally, readers must ensure that the instrument scores can be trusted to truly represent the construct being measured. For example, suppose you encounter a research article demonstrating a positive association between attending physician teaching effectiveness as measured by a survey of medical students, and the frequency with which the attending physician provides coffee and doughnuts on rounds. Can we be confident that this survey administered to medical students is truly measuring teaching effectiveness? Or is it simply measuring the attending physician’s “likability”? Issues related to measurement and the trustworthiness of data are described in detail in the following section on measurement and the related issues of validity and reliability.

Measurement refers to “the assigning of numbers to individuals in a systematic way as a means of representing properties of the individuals.” 23 Research data can only be trusted insofar as we trust the measurement used to obtain the data. Measurement is of particular importance in medical education research because many of the constructs being measured ( e.g. , knowledge, skill, attitudes) are abstract and subject to measurement error. 24 This section highlights two specific issues related to the trustworthiness of data: the validity and reliability of measurements.

Validity regarding the scores of a measurement instrument “refers to the degree to which evidence and theory support the interpretations of the [instrument’s results] for the proposed use of the [instrument].” 25 In essence, do we believe the results obtained from a measurement really represent what we were trying to measure? Note that validity evidence for the scores of a measurement instrument is separate from the internal validity of a research study. Several frameworks for validity evidence exist. Table 4 2 , 22 , 26 represents the most commonly used framework, developed by Messick, 27 which identifies sources of validity evidence—to support the target construct—from five main categories: content, response process, internal structure, relations to other variables, and consequences.

Sources of Validity Evidence for Measurement Instruments

Reliability

Reliability refers to the consistency of scores for a measurement instrument. 22 , 25 , 28 For an instrument to be reliable, we would anticipate that two individuals rating the same object of measurement in a specific context would provide the same scores. 25 Further, if the scores for an instrument are reliable between raters of the same object of measurement, then we can extrapolate that any difference in scores between two objects represents a true difference across the sample, and is not due to random variation in measurement. 29 Reliability can be demonstrated through a variety of methods such as internal consistency ( e.g. , Cronbach’s alpha), temporal stability ( e.g. , test–retest reliability), interrater agreement ( e.g. , intraclass correlation coefficient), and generalizability theory (generalizability coefficient). 22 , 29

Example of a Validity and Reliability Argument

This section provides an illustration of validity and reliability in medical education. We use the signaling questions outlined in table 4 to make a validity and reliability argument for the Harvard Assessment of Anesthesia Resident Performance (HARP) instrument. 7 The HARP was developed by Blum et al. to measure the performance of anesthesia trainees that is required to provide safe anesthetic care to patients. According to the authors, the HARP is designed to be used “…as part of a multiscenario, simulation-based assessment” of resident performance. 7

Content Validity: Does the Instrument’s Content Represent the Construct Being Measured?

To demonstrate content validity, instrument developers should describe the construct being measured and how the instrument was developed, and justify their approach. 25 The HARP is intended to measure resident performance in the critical domains required to provide safe anesthetic care. As such, investigators note that the HARP items were created through a two-step process. First, the instrument’s developers interviewed anesthesiologists with experience in resident education to identify the key traits needed for successful completion of anesthesia residency training. Second, the authors used a modified Delphi process to synthesize the responses into five key behaviors: (1) formulate a clear anesthetic plan, (2) modify the plan under changing conditions, (3) communicate effectively, (4) identify performance improvement opportunities, and (5) recognize one’s limits. 7 , 30

Response Process Validity: Are Raters Interpreting the Instrument Items as Intended?

In the case of the HARP, the developers included a scoring rubric with behavioral anchors to ensure that faculty raters could clearly identify how resident performance in each domain should be scored. 7

Internal Structure Validity: Do Instrument Items Measuring Similar Constructs Yield Homogenous Results? Do Instrument Items Measuring Different Constructs Yield Heterogeneous Results?

Item-correlation for the HARP demonstrated a high degree of correlation between some items ( e.g. , formulating a plan and modifying the plan under changing conditions) and a lower degree of correlation between other items ( e.g. , formulating a plan and identifying performance improvement opportunities). 30 This finding is expected since the items within the HARP are designed to assess separate performance domains, and we would expect residents’ functioning to vary across domains.

Relationship to Other Variables’ Validity: Do Instrument Scores Correlate with Other Measures of Similar or Different Constructs as Expected?

As it applies to the HARP, one would expect that the performance of anesthesia residents will improve over the course of training. Indeed, HARP scores were found to be generally higher among third-year residents compared to first-year residents. 30

Consequence Validity: Are Instrument Results Being Used as Intended? Are There Unintended or Negative Uses of the Instrument Results?

While investigators did not intentionally seek out consequence validity evidence for the HARP, unanticipated consequences of HARP scores were identified by the authors as follows:

“Data indicated that CA-3s had a lower percentage of worrisome scores (rating 2 or lower) than CA-1s… However, it is concerning that any CA-3s had any worrisome scores…low performance of some CA-3 residents, albeit in the simulated environment, suggests opportunities for training improvement.” 30

That is, using the HARP to measure the performance of CA-3 anesthesia residents had the unintended consequence of identifying the need for improvement in resident training.

Reliability: Are the Instrument’s Scores Reproducible and Consistent between Raters?

The HARP was applied by two raters for every resident in the study across seven different simulation scenarios. The investigators conducted a generalizability study of HARP scores to estimate the variance in assessment scores that was due to the resident, the rater, and the scenario. They found little variance was due to the rater ( i.e. , scores were consistent between raters), indicating a high level of reliability. 7

Sampling refers to the selection of research subjects ( i.e. , the sample) from a larger group of eligible individuals ( i.e. , the population). 31 Effective sampling leads to the inclusion of research subjects who represent the larger population of interest. Alternatively, ineffective sampling may lead to the selection of research subjects who are significantly different from the target population. Imagine that researchers want to explore the relationship between burnout and educational debt among pain medicine specialists. The researchers distribute a survey to 1,000 pain medicine specialists (the population), but only 300 individuals complete the survey (the sample). This result is problematic because the characteristics of those individuals who completed the survey and the entire population of pain medicine specialists may be fundamentally different. It is possible that the 300 study subjects may be experiencing more burnout and/or debt, and thus, were more motivated to complete the survey. Alternatively, the 700 nonresponders might have been too busy to respond and even more burned out than the 300 responders, which would suggest that the study findings were even more amplified than actually observed.

When evaluating a medical education research article, it is important to identify the sampling technique the researchers employed, how it might have influenced the results, and whether the results apply to the target population. 24

Sampling Techniques

Sampling techniques generally fall into two categories: probability- or nonprobability-based. Probability-based sampling ensures that each individual within the target population has an equal opportunity of being selected as a research subject. Most commonly, this is done through random sampling, which should lead to a sample of research subjects that is similar to the target population. If significant differences between sample and population exist, those differences should be due to random chance, rather than systematic bias. The difference between data from a random sample and that from the population is referred to as sampling error. 24

Nonprobability-based sampling involves selecting research participants such that inclusion of some individuals may be more likely than the inclusion of others. 31 Convenience sampling is one such example and involves selection of research subjects based upon ease or opportuneness. Convenience sampling is common in medical education research, but, as outlined in the example at the beginning of this section, it can lead to sampling bias. 24 When evaluating an article that uses nonprobability-based sampling, it is important to look for participation/response rate. In general, a participation rate of less than 75% should be viewed with skepticism. 21 Additionally, it is important to determine whether characteristics of participants and nonparticipants were reported and if significant differences between the two groups exist.

Interpreting medical education research requires a basic understanding of common ways in which quantitative data are analyzed and displayed. In this section, we highlight two broad topics that are of particular importance when evaluating research articles.

The Nature of the Measurement Variable

Measurement variables in quantitative research generally fall into three categories: nominal, ordinal, or interval. 24 Nominal variables (sometimes called categorical variables) involve data that can be placed into discrete categories without a specific order or structure. Examples include sex (male or female) and professional degree (M.D., D.O., M.B.B.S., etc .) where there is no clear hierarchical order to the categories. Ordinal variables can be ranked according to some criterion, but the spacing between categories may not be equal. Examples of ordinal variables may include measurements of satisfaction (satisfied vs . unsatisfied), agreement (disagree vs . agree), and educational experience (medical student, resident, fellow). As it applies to educational experience, it is noteworthy that even though education can be quantified in years, the spacing between years ( i.e. , educational “growth”) remains unequal. For instance, the difference in performance between second- and third-year medical students is dramatically different than third- and fourth-year medical students. Interval variables can also be ranked according to some criteria, but, unlike ordinal variables, the spacing between variable categories is equal. Examples of interval variables include test scores and salary. However, the conceptual boundaries between these measurement variables are not always clear, as in the case where ordinal scales can be assumed to have the properties of an interval scale, so long as the data’s distribution is not substantially skewed. 32

Understanding the nature of the measurement variable is important when evaluating how the data are analyzed and reported. Medical education research commonly uses measurement instruments with items that are rated on Likert-type scales, whereby the respondent is asked to assess their level of agreement with a given statement. The response is often translated into a corresponding number ( e.g. , 1 = strongly disagree, 3 = neutral, 5 = strongly agree). It is remarkable that scores from Likert-type scales are sometimes not normally distributed ( i.e. , are skewed toward one end of the scale), indicating that the spacing between scores is unequal and the variable is ordinal in nature. In these cases, it is recommended to report results as frequencies or medians, rather than means and SDs. 33

Consider an article evaluating medical students’ satisfaction with a new curriculum. Researchers measure satisfaction using a Likert-type scale (1 = very unsatisfied, 2 = unsatisfied, 3 = neutral, 4 = satisfied, 5 = very satisfied). A total of 20 medical students evaluate the curriculum, 10 of whom rate their satisfaction as “satisfied,” and 10 of whom rate it as “very satisfied.” In this case, it does not make much sense to report an average score of 4.5; it makes more sense to report results in terms of frequency ( e.g. , half of the students were “very satisfied” with the curriculum, and half were not).

Effect Size and CIs

In medical education, as in other research disciplines, it is common to report statistically significant results ( i.e. , small P values) in order to increase the likelihood of publication. 34 , 35 However, a significant P value in itself does necessarily represent the educational impact of the study results. A statement like “Intervention x was associated with a significant improvement in learners’ intubation skill compared to education intervention y ( P < 0.05)” tells us that there was a less than 5% chance that the difference in improvement between interventions x and y was due to chance. Yet that does not mean that the study intervention necessarily caused the nonchance results, or indicate whether the between-group difference is educationally significant. Therefore, readers should consider looking beyond the P value to effect size and/or CI when interpreting the study results. 36 , 37

Effect size is “the magnitude of the difference between two groups,” which helps to quantify the educational significance of the research results. 37 Common measures of effect size include Cohen’s d (standardized difference between two means), risk ratio (compares binary outcomes between two groups), and Pearson’s r correlation (linear relationship between two continuous variables). 37 CIs represent “a range of values around a sample mean or proportion” and are a measure of precision. 31 While effect size and CI give more useful information than simple statistical significance, they are commonly omitted from medical education research articles. 35 In such instances, readers should be wary of overinterpreting a P value in isolation. For further information effect size and CI, we direct readers the work of Sullivan and Feinn 37 and Hulley et al. 31

In this final section, we identify instruments that can be used to evaluate the quality of quantitative medical education research articles. To this point, we have focused on framing the study and research methodologies and identifying potential pitfalls to consider when appraising a specific article. This is important because how a study is framed and the choice of methodology require some subjective interpretation. Fortunately, there are several instruments available for evaluating medical education research methods and providing a structured approach to the evaluation process.

The Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) 21 and the Newcastle Ottawa Scale-Education (NOS-E) 38 are two commonly used instruments, both of which have an extensive body of validity evidence to support the interpretation of their scores. Table 5 21 , 39 provides more detail regarding the MERSQI, which includes evaluation of study design, sampling, data type, validity, data analysis, and outcomes. We have found that applying the MERSQI to manuscripts, articles, and protocols has intrinsic educational value, because this practice of application familiarizes MERSQI users with fundamental principles of medical education research. One aspect of the MERSQI that deserves special mention is the section on evaluating outcomes based on Kirkpatrick’s widely recognized hierarchy of reaction, learning, behavior, and results ( table 5 ; fig .). 40 Validity evidence for the scores of the MERSQI include its operational definitions to improve response process, excellent reliability, and internal consistency, as well as high correlation with other measures of study quality, likelihood of publication, citation rate, and an association between MERSQI score and the likelihood of study funding. 21 , 41 Additionally, consequence validity for the MERSQI scores has been demonstrated by its utility for identifying and disseminating high-quality research in medical education. 42

Kirkpatrick’s hierarchy of outcomes as applied to education research. Reaction = Level 1, Learning = Level 2, Behavior = Level 3, Results = Level 4. Outcomes become more meaningful, yet more difficult to achieve, when progressing from Level 1 through Level 4. Adapted with permission from Beckman and Cook, 2007. 2

The Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument for Evaluating the Quality of Medical Education Research

The NOS-E is a newer tool to evaluate the quality of medication education research. It was developed as a modification of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale 43 for appraising the quality of nonrandomized studies. The NOS-E includes items focusing on the representativeness of the experimental group, selection and compatibility of the control group, missing data/study retention, and blinding of outcome assessors. 38 , 39 Additional validity evidence for NOS-E scores includes operational definitions to improve response process, excellent reliability and internal consistency, and its correlation with other measures of study quality. 39 Notably, the complete NOS-E, along with its scoring rubric, can found in the article by Cook and Reed. 39

A recent comparison of the MERSQI and NOS-E found acceptable interrater reliability and good correlation between the two instruments 39 However, noted differences exist between the MERSQI and NOS-E. Specifically, the MERSQI may be applied to a broad range of study designs, including experimental and cross-sectional research. Additionally, the MERSQI addresses issues related to measurement validity and data analysis, and places emphasis on educational outcomes. On the other hand, the NOS-E focuses specifically on experimental study designs, and on issues related to sampling techniques and outcome assessment. 39 Ultimately, the MERSQI and NOS-E are complementary tools that may be used together when evaluating the quality of medical education research.

Conclusions

This article provides an overview of quantitative research in medical education, underscores the main components of education research, and provides a general framework for evaluating research quality. We highlighted the importance of framing a study with respect to purpose, conceptual framework, and statement of study intent. We reviewed the most common research methodologies, along with threats to the validity of a study and its measurement instruments. Finally, we identified two complementary instruments, the MERSQI and NOS-E, for evaluating the quality of a medical education research study.

Bordage G: Conceptual frameworks to illuminate and magnify. Medical education. 2009; 43(4):312–9.

Cook DA, Beckman TJ: Current concepts in validity and reliability for psychometric instruments: Theory and application. The American journal of medicine. 2006; 119(2):166. e7–166. e116.

Franenkel JR, Wallen NE, Hyun HH: How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education. 9th edition. New York, McGraw-Hill Education, 2015.

Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, Grady DG, Newman TB: Designing clinical research. 4th edition. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011.

Irby BJ, Brown G, Lara-Alecio R, Jackson S: The Handbook of Educational Theories. Charlotte, NC, Information Age Publishing, Inc., 2015

Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (American Educational Research Association & American Psychological Association, 2014)

Swanwick T: Understanding medical education: Evidence, theory and practice, 2nd edition. Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

Sullivan GM, Artino Jr AR: Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert-type scales. Journal of graduate medical education. 2013; 5(4):541–2.

Sullivan GM, Feinn R: Using effect size—or why the P value is not enough. Journal of graduate medical education. 2012; 4(3):279–82.

Tavakol M, Sandars J: Quantitative and qualitative methods in medical education research: AMEE Guide No 90: Part II. Medical teacher. 2014; 36(10):838–48.

Support was provided solely from institutional and/or departmental sources.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Citing articles via

Most viewed, email alerts, related articles, social media, affiliations.

- ASA Practice Parameters

- Online First

- Author Resource Center

- About the Journal

- Editorial Board

- Rights & Permissions

- Online ISSN 1528-1175

- Print ISSN 0003-3022

- Anesthesiology

- ASA Monitor

- Terms & Conditions Privacy Policy

- Manage Cookie Preferences

- © Copyright 2024 American Society of Anesthesiologists

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 06 January 2021

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students: a multicenter quantitative study

- Aaron J. Harries ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7107-0995 1 ,

- Carmen Lee 1 ,

- Lee Jones 2 ,

- Robert M. Rodriguez 1 ,

- John A. Davis 2 ,

- Megan Boysen-Osborn 3 ,

- Kathleen J. Kashima 4 ,

- N. Kevin Krane 5 ,

- Guenevere Rae 6 ,

- Nicholas Kman 7 ,

- Jodi M. Langsfeld 8 &

- Marianne Juarez 1

BMC Medical Education volume 21 , Article number: 14 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

139k Accesses

166 Citations

38 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the United States (US) medical education system with the necessary, yet unprecedented Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) national recommendation to pause all student clinical rotations with in-person patient care. This study is a quantitative analysis investigating the educational and psychological effects of the pandemic on US medical students and their reactions to the AAMC recommendation in order to inform medical education policy.

The authors sent a cross-sectional survey via email to medical students in their clinical training years at six medical schools during the initial peak phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Survey questions aimed to evaluate students’ perceptions of COVID-19’s impact on medical education; ethical obligations during a pandemic; infection risk; anxiety and burnout; willingness and needed preparations to return to clinical rotations.

Seven hundred forty-one (29.5%) students responded. Nearly all students (93.7%) were not involved in clinical rotations with in-person patient contact at the time the study was conducted. Reactions to being removed were mixed, with 75.8% feeling this was appropriate, 34.7% guilty, 33.5% disappointed, and 27.0% relieved.

Most students (74.7%) agreed the pandemic had significantly disrupted their medical education, and believed they should continue with normal clinical rotations during this pandemic (61.3%). When asked if they would accept the risk of infection with COVID-19 if they returned to the clinical setting, 83.4% agreed.

Students reported the pandemic had moderate effects on their stress and anxiety levels with 84.1% of respondents feeling at least somewhat anxious. Adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) (53.5%) was the most important factor to feel safe returning to clinical rotations, followed by adequate testing for infection (19.3%) and antibody testing (16.2%).

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the education of US medical students in their clinical training years. The majority of students wanted to return to clinical rotations and were willing to accept the risk of COVID-19 infection. Students were most concerned with having enough PPE if allowed to return to clinical activities.

Peer Review reports

The COVID-19 pandemic has tested the limits of healthcare systems and challenged conventional practices in medical education. The rapid evolution of the pandemic dictated that critical decisions regarding the training of medical students in the United States (US) be made expeditiously, without significant input or guidance from the students themselves. On March 17, 2020, for the first time in modern US history, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the largest national governing body of US medical schools, released guidance recommending that medical students immediately pause all clinical rotations to allow time to obtain additional information about the risks of COVID-19 and prepare for safe participation in the future. This decisive action would also conserve scarce resources such as personal protective equipment (PPE) and testing kits; minimize exposure of healthcare workers (HCWs) and the general population; and protect students’ education and wellbeing [ 1 ].

A similar precedent was set outside of the US during the SARS-CoV1 epidemic in 2003, where an initial cluster of infection in medical students in Hong Kong resulted in students being removed from hospital systems where SARS surfaced, including Hong Kong, Singapore and Toronto [ 2 , 3 ]. Later, studies demonstrated that the exclusion of Canadian students from those clinical environments resulted in frustration at lost learning opportunities and students’ inability to help [ 3 ]. International evidence also suggests that medical students perceive an ethical obligation to participate in pandemic response, and are willing to participate in scenarios similar to the current COVID-19 crisis, even when they believe the risk of infection to themselves to be high [ 4 , 5 , 6 ].

The sudden removal of some US medical students from educational settings has occurred previously in the wake of local disasters, with significant academic and personal impacts. In 2005, it was estimated that one-third of medical students experienced some degree of depression or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after Hurricane Katrina resulted in the closure of Tulane University School of Medicine [ 7 ].

Prior to the current COVID-19 pandemic, we found no studies investigating the effects of pandemics on the US medical education system or its students. The limited pool of evidence on medical student perceptions comes from two earlier global coronavirus surges, SARS and MERS, and studies of student anxiety related to pandemics are also limited to non-US populations [ 3 , 8 , 9 ]. Given the unprecedented nature of the current COVID-19 pandemic, there is concern that students may be missing out on meaningful educational experiences and months of clinical training with unknown effects on their current well-being or professional trajectory [ 10 ].

Our study, conducted during the initial peak phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, reports students’ perceptions of COVID-19’s impact on: medical student education; ethical obligations during a pandemic; perceptions of infection risk; anxiety and burnout; willingness to return to clinical rotations; and needed preparations to return safely. This data may help inform policies regarding the roles of medical students in clinical training during the current pandemic and prepare for the possibility of future pandemics.

We conducted a cross-sectional survey during the initial peak phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, from 4/20/20 to 5/25/20, via email sent to all clinically rotating medical students at six US medical schools: University of California San Francisco School of Medicine (San Francisco, CA), University of California Irvine School of Medicine (Irvine, CA), Tulane University School of Medicine (New Orleans, LA), University of Illinois College of Medicine (Chicago, Peoria, Rockford, and Urbana, IL), Ohio State University College of Medicine (Columbus, OH), and Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell (Hempstead, NY). Traditional undergraduate medical education in the US comprises 4 years of medical school with 2 years of primarily pre-clinical classroom learning followed by 2 years of clinical training involving direct patient care. Study participants were defined as medical students involved in their clinical training years at whom the AAMC guidance statement was directed. Depending on the curricular schedule of each medical school, this included intended graduation class years of 2020 (graduating 4th year student), 2021 (rising 4th year student), and 2022 (rising 3rd year student), exclusive of planned time off. Participating schools were specifically chosen to represent a broad spectrum of students from different regions of the country (West, South, Midwest, East) with variable COVID-19 prevalence. We excluded medical students not yet involved in clinical rotations. This study was deemed exempt by the respective Institutional Review Boards.

We developed a survey instrument modeled after a survey used in a previously published peer reviewed study evaluating the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Emergency Physicians, which incorporated items from validated stress scales [ 11 ]. The survey was modified for use in medical students to assess perceptions of the following domains: perceived impact on medical student education; ethical beliefs surrounding obligations to participate clinically during the pandemic; perceptions of personal infection risk; anxiety and burnout related to the pandemic; willingness to return to clinical rotations; and preparation needed for students to feel safe in the clinical environment. Once created, the survey underwent an iterative process of input and review from our team of authors with experience in survey methodology and psychometric measures to allow for optimization of content and validity. We tested a pilot of our preliminary instrument on five medical students to ensure question clarity, and confirm completion of the survey in approximately 10 min. The final survey consisted of 29 Likert, yes/no, multiple choice, and free response questions. Both medical school deans and student class representatives distributed the survey via email, with three follow-up emails to increase response rates. Data was collected anonymously.

For example, to assess the impact on students’ anxiety, participants were asked, “How much has the COVID-19 pandemic affected your stress or anxiety levels?” using a unipolar 7-point scale (1 = not at all, 4 = somewhat, 7 = extremely). To assess willingness to return to clinical rotations, participants were asked to rate on a bipolar scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = somewhat disagree, 4 = neither disagree nor agree, 5 = somewhat agree, 6 = agree, and 7 = strongly agree) their agreement with the statement: “to the extent possible, medical students should continue with normal clinical rotations during this pandemic.” (Survey Instrument, Supplemental Table 1 ).

Survey data was managed using Qualtrics hosted by the University of California, San Francisco. For data analysis we used STATA v15.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). We summarized respondent characteristics and key responses as raw counts, frequency percent, medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). For responses to bipolar questions, we combined positive responses (somewhat agree, agree, or strongly agree) into an agreement percentage. To compare differences in medians we used a signed rank test with p value < 0.05 to show statistical difference. In a secondary analysis we stratified data to compare questions within key domains amongst the following sub-groups: female versus male, graduation year, local community COVID-19 prevalence (high, medium, low), and students on clinical rotations with in-person patient care. This secondary analysis used a chi square test with p value < 0.05 to show statistical difference between sub-group agreement percentages.

Of 2511 students contacted, we received 741 responses (29.5% response rate). Of these, 63.9% of respondents were female and 35.1% were male, with 1.0% reporting a different gender identity; 27.7% of responses came from the class of 2020, 53.5% from the class of 2021, and 18.7% from the class of 2022. (Demographics, Table 1 ).

Most student respondents (74.9%) had a clinical rotation that was cut short or canceled due to COVID-19 and 93.7% reported not being involved in clinical rotations with in-person patient contact at the time of the study. Regarding students’ perceptions of cancelled rotations (allowing for multiple reactions), 75.8% felt this was appropriate, 34.7% felt guilty for not being able to help patients and colleagues, 33.5% felt disappointed, and 27.0% felt relieved.

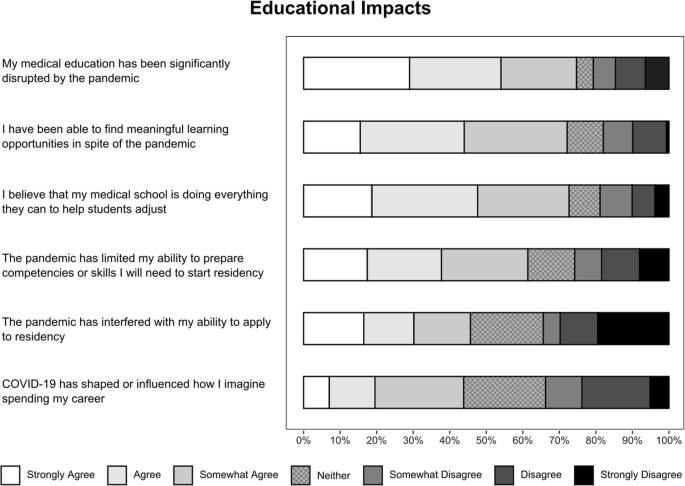

Most students (74.7%) agreed that their medical education had been significantly disrupted by the pandemic. Students also felt they were able to find meaningful learning experiences during the pandemic (72.1%). Free response examples included: taking a novel COVID-19 pandemic elective course, telehealth patient care, clinical rotations transitioned to virtual online courses, research or education electives, clinical and non-clinical COVID-19-related volunteering, and self-guided independent study electives. Students felt their medical schools were doing everything they could to help students adjust (72.7%). Overall, respondents felt the pandemic had interfered with their ability to develop skills needed to prepare for residency (61.4%), though fewer (45.7%) felt it had interfered with their ability to apply to residency. (Educational Impact, Fig. 1 ).

Perceived educational impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students

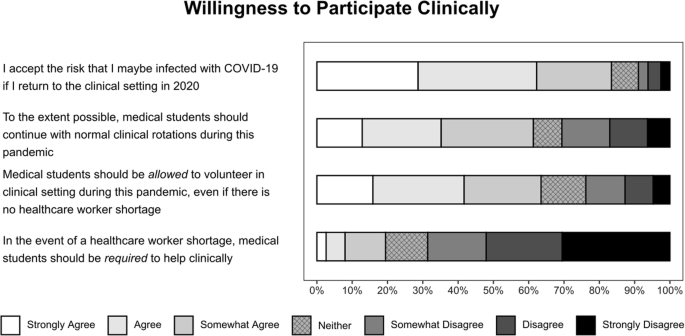

A majority of medical students agreed they should be allowed to continue with normal clinical rotations during this pandemic (61.3%). Most students agreed (83.4%) that they accepted the risk of being infected with COVID-19, if they returned. When asked if students should be allowed to volunteer in clinical settings even if there is not a healthcare worker (HCW) shortage, 63.5% agreed; however, in the case of a HCW shortage only 19.5% believed students should be required to volunteer clinically. (Willingness to Participate Clinically, Fig. 2 ).

Willingness to participate clinically during the COVID-19 pandemic

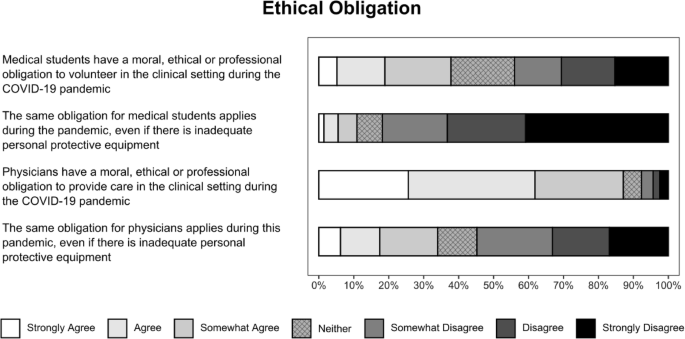

When asked if they perceived a moral, ethical, or professional obligation for medical students to help, 37.8% agreed that medical students have such an obligation during the current pandemic. This is in contrast to their perceptions of physicians: 87.1% of students agreed with a physician obligation to help during the COVID-19 pandemic. For both groups, students were asked if this obligation persisted without adequate PPE: only 10.9% of students believed medical students had this obligation, while 34.0% agreed physicians had this obligation. (Ethical Obligation, Fig. 3 ).

Ethical obligation to volunteer during the COVID-19 pandemic

Given the assumption that there will not be a COVID-19 vaccine until 2021, students felt the single most important factor in a safe return to clinical rotations was having access to adequate PPE (53.3%), followed by adequate testing for infection (19.3%) and antibody testing for possible immunity (16.2%). Few students (5%) stated that nothing would make them feel comfortable until a vaccine is available. On a 1–7 scale (1 = not at all, 4 = somewhat, 7 = extremely), students felt somewhat prepared to use PPE during this pandemic in the clinical setting, median = 4 (IQR 4,6), and somewhat confident identifying symptoms most concerning for COVID-19, median = 4 (IQR 4,5). Students preferred to learn about PPE via video demonstration (76.7%), online modules (47.7%), and in-person or Zoom style conferences (44.7%).

Students believed they were likely to contract COVID-19 in general (75.6%), independent of a return to the clinical environment. Most respondents believed that missing some school or work would be a likely outcome (90.5%), and only a minority of students believed that hospitalization (22.1%) or death (4.3%) was slightly, moderately, or extremely likely.

On a 1–7 scale (1 = not at all, 4 = somewhat, and 7 = extremely), the median (IQR) reported effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ stress or anxiety level was 5 (4, 6) with 84.1% of respondents feeling at least somewhat anxious due to the pandemic. Students’ perceived emotional exhaustion and burnout before the pandemic was a median = 2 (IQR 2,4) and since the pandemic started a median = 4 (IQR 2,5) with a median difference Δ = 2, p value < 0.001.

Secondary analysis of key questions revealed statistical differences between sub-groups. Women were significantly more likely than men to agree that the pandemic had affected their anxiety. Several significant differences existed for the class of 2020 when compared to the classes of 2021 and 2022: they were less likely to report disruptions to their education, to prefer to return to rotations, and to report an effect on anxiety. There were no significant differences with students who were still involved with in-person patient care compared with those who were not. In comparing areas with high COVID-19 prevalence at the time of the survey (New York and Louisiana) with medium (Illinois and Ohio) and low prevalence (California), students were less likely to report that the pandemic had disrupted their education. Students in low prevalence areas were most likely to agree that medical students should return to rotations. There were no differences between prevalence groups in accepting the risk of infection to return, or subjective anxiety effects. (Stratification, Table 2 ).

The COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally transformed education at all levels - from preschool to postgraduate. Although changes to K-12 and college education have been well documented [ 12 , 13 ], there have been very few studies to date investigating the effects of COVID-19 on undergraduate medical education [ 14 ]. To maintain the delicate balance between student safety and wellbeing, and the time-sensitive need to train future physicians, student input must guide decisions regarding their roles in the clinical arena. Student concerns related to the pandemic, paired with their desire to return to rotations despite the risks, suggest that medical students may take on emotional burdens as members of the patient care team even when not present in the clinical environment. This study offers insight into how best to support medical students as they return to clinical rotations, how to prepare them for successful careers ahead, and how to plan for their potential roles in future pandemics.

Previous international studies of medical student attitudes towards hypothetical influenza-like pandemics demonstrated a willingness (80%) [ 4 ] and a perceived ethical obligation to volunteer (77 and 70%), despite 40% of Canadian students in one study perceiving a high likelihood of becoming infected [ 5 , 6 ]. Amidst the current COVID-19 pandemic, our participants reported less agreement with a medical student ethical obligation to volunteer in the clinical setting at 37.8%, but believed in a higher likelihood of becoming infected at 75.6%. Their willingness to be allowed to volunteer freely (63.5%) may suggest that the stresses of an ongoing pandemic alter students’ perceptions of the ethical requirement more than their willingness to help. Students overwhelmingly agreed that physicians had an ethical obligation to provide care during the COVID-19 pandemic (87.1%), possibly reflecting how they view the ethical transition from student to physician, or differences between paid professionals and paying for an education.

At the time our study was conducted, there were widespread concerns for possible HCW shortages. It was unclear whether medical students would be called to volunteer when residents became ill, or even graduate early to start residency training immediately (as occurred at half of schools surveyed). This timing allowed us to capture a truly unique perspective amongst medical students, a majority of whom reported increased anxiety and burnout due to the pandemic. At the same time, students felt that their medical schools were doing everything possible to support them, perhaps driven by virtual town halls and daily communication updates.

Trends in secondary analysis show important differences in the impacts of the pandemic. Women were more likely to report increased anxiety as compared to men, which may reflect broader gender differences in medical student anxiety [ 15 ] but requires more study to rule out different pandemic stresses by gender. Graduating medical students (class of 2020) overall described less impact on medical education and anxiety, a decreased desire to return to rotations, but equal acceptance of the risk of infection in clinical settings, possibly reflecting a focus on their upcoming intern year rather than the remaining months of undergraduate medical education. Since this class’s responses decreased overall agreement on these questions, educational impacts and anxiety effects may have been even greater had they been assessed further from graduation. Interestingly, students from areas with high local COVID-19 prevalence (New York and Louisiana) reported a less significant effect of the pandemic on their education, a paradoxical result that may indicate that medical student tolerance for the disruptions was greater in high-prevalence areas, as these students were removed at the same, if not higher, rates as their peers. Our results suggest that in future waves of the current pandemic or other disasters, students may be more patient with educational impacts when they have more immediate awareness of strains on the healthcare system.

A limitation of our study was the survey response rate, which was anticipated given the challenges students were facing. Some may not have been living near campus; others may have stopped reading emails due to early graduation or limited access to email; and some would likely be dealing with additional personal challenges related to the pandemic. We attempted to increase response rates by having the study sent directly from medical school deans and leadership, as well as respective class representatives, and by sending reminders for completion. The survey was not incentivized, and a higher response rate in the class of 2021 across all schools may indicate that students who felt their education was most affected were most likely to respond. We addressed this potential source of bias in the secondary analysis, which showed no differences between 2021 and 2022 respondents. Another limitation was the inherent issue with survey data collection of missing responses for some questions that occurred in a small number of surveys. This resulted in slight variability in the total responses received for certain questions, which were not statistically significant. To be transparent about this limitation, we presented our data by stating each total response and denominator in the Tables.

This initial study lays the groundwork for future investigations and next steps. With 72.1% of students agreeing that they were able to find meaningful learning in spite of the pandemic, future research should investigate novel learning modalities that were successful during this time. Educators should consider additional training on PPE use, given only moderate levels of student comfort in this area, which may be best received via video. It is also important to study the long-term effects of missing several months of essential clinical training and identifying competencies that may not have been achieved, since students perceived a significant disruption to their ability to prepare skills for residency. Next steps could be to study curriculum interventions, such as capstone boot camps and targeted didactic skills training, to help students feel more comfortable as they transition into residency. Educators must also acknowledge that some students may not feel comfortable returning to the clinical environment until a vaccine becomes available (5%) and ensure they are equally supported. Lastly, it is vital to further investigate the mental health effects of the pandemic on medical students, identifying subgroups with additional stressors, needs related to anxiety or possible PTSD, and ways to minimize these negative effects.

In this cross-sectional survey, conducted during the initial peak phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, we capture a snapshot of the effects of the pandemic on US medical students and gain insight into their reactions to the unprecedented AAMC national recommendation for removal from clinical rotations. Student respondents from across the US similarly recognized a significant disruption to their medical education, shared a desire to continue with in-person rotations, and were willing to accept the risk of infection with COVID-19. Our novel results provide a solid foundation to help shape medical student roles in the clinical environment during this pandemic and future outbreaks.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Interim Guidance on Medical Students’ Participation in Direct Patient Contact Activities: Principles and Guidelines. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/important-guidance-medical-students-clinical-rotations-during-coronavirus-covid-19-outbreak . Published March 17, 2020. Accessed April 1, 2020.

Clark J. Fear of SARS thwarts medical education in Toronto. BMJ. 2003;326(7393):784. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7393.784/c .

Article Google Scholar

Loh LC, Ali AM, Ang TH, Chelliah A. Impact of a spreading epidemic on medical students. Malays J Med Sci. 2006;13(2):30–6.

Google Scholar

Mortelmans LJ, Bouman SJ, Gaakeer MI, Dieltiens G, Anseeuw K, Sabbe MB. Dutch senior medical students and disaster medicine: a national survey. Int J Emerg Med. 2015;8(1):77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-015-0077-0 .

Huapaya JA, Maquera-Afaray J, García PJ, Cárcamo C, Cieza JA. Conocimientos, prácticas y actitudes hacia el voluntariado ante una influenza pandémica: estudio transversal con estudiantes de medicina en Perú [Knowledge, practices and attitudes toward volunteer work in an influenza pandemic: cross-sectional study with Peruvian medical students]. Medwave. 2015;15(4):e6136Published 2015 May 8. https://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2015.04.6136 .

Herman B, Rosychuk RJ, Bailey T, Lake R, Yonge O, Marrie TJ. Medical students and pandemic influenza. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(11):1781–3. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1311.070279 .

Kahn MJ, Markert RJ, Johnson JE, Owens D, Krane NK. Psychiatric issues and answers following hurricane Katrina. Acad Psychiatry. 2007;31(3):200–4. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.31.3.200 .

Al-Rabiaah A, Temsah MH, Al-Eyadhy AA, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome-Corona virus (MERS-CoV) associated stress among medical students at a university teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(5):687–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.01.005 .

Wong JG, Cheung EP, Cheung V, et al. Psychological responses to the SARS outbreak in healthcare students in Hong Kong. Med Teach. 2004;26(7):657–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590400006572 .

Stokes DC. Senior medical students in the COVID-19 response: an opportunity to be proactive. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(4):343–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13972 .

Rodriguez RM, Medak AJ, Baumann BM, et al. Academic emergency medicine physicians’ anxiety levels, stressors, and potential mitigation measures during the acceleration phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(8):700–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14065 .

Sahu P. Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus. 2020;12(4):e7541Published 2020 Apr 4. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7541 .

Reimers FM, Schleicher A. A framework to guide an education response to the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020: OECD. https://www.hm.ee/sites/default/files/framework_guide_v1_002_harward.pdf .

Choi B, Jegatheeswaran L, Minocha A, Alhilani M, Nakhoul M, Mutengesa E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on final year medical students in the United Kingdom: a national survey. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:206–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02117-1 .

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad Med. 2006;81(4):354–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009 .

Download references

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Newton Addo, UCSF Statistician.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Emergency Medicine, University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, San Francisco General Hospital, 1001 Potrero Avenue, Building 5, Room #6A4, San Francisco, California, 94110, USA

Aaron J. Harries, Carmen Lee, Robert M. Rodriguez & Marianne Juarez

University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, San Francisco, California, USA

Lee Jones & John A. Davis

Clinical Emergency Medicine, University of California Irvine School of Medicine, Irvine, CA, USA

Megan Boysen-Osborn

University of Illinois College of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA

Kathleen J. Kashima

Deming Department of Medicine, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA

N. Kevin Krane

Basic Science Education, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA

Guenevere Rae

Emergency Medicine, Ohio State College of Medicine, Columbus, OH, USA

Nicholas Kman

Department of Science Education, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, New York, USA

Jodi M. Langsfeld

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the study and met the specific conditions listed in the BMC Medical Education editorial policy for authorship. All authors have read and approved the manuscript. AH as principal investigator contributed to study design, survey instrument creation, IRB submission for his respective medical school, acquisition of data and recruitment of other participating medical schools, data analysis, writing and editing the manuscript. CL contributed to background literature review, study design, survey instrument creation, acquisition of data, data analysis, writing and editing the manuscript. LJ contributed to study design, survey instrument creation, acquisition of data from his respective medical school and recruitment of other participating medical schools, data analysis, and editing the manuscript. RR contributed to study design, survey instrument creation, data analysis, writing and editing the manuscript. JD contributed to study design, survey instrument creation, recruitment of other participating medical schools, data analysis, and editing the manuscript. MBO contributed as individual site principal investigator obtaining IRB exemption acceptance and acquisition of data from her respective medical school along with editing the manuscript. KK contributed as individual site principal investigator obtaining IRB exemption acceptance and acquisition of data from her respective medical school along with editing the manuscript. NKK contributed as individual site co-principal investigator obtaining IRB exemption acceptance and acquisition of data from his respective medical school along with editing the manuscript. GR contributed as individual site co-principal investigator obtaining IRB exemption acceptance and acquisition of data from her respective medical school along with editing the manuscript. NK contributed as individual site principal investigator obtaining IRB exemption acceptance and acquisition of data from his respective medical school along with editing the manuscript. JL contributed as individual site principal investigator obtaining IRB exemption acceptance and acquisition of data from her respective medical school along with editing the manuscript. MJ contributed to study design, survey instrument creation, data analysis, writing and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Aaron J. Harries or Marianne Juarez .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was reviewed and deemed exempt by each participating medical school’s Institutional Review Board (IRB): University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, IRB# 20–30712, Reference# 280106, Tulane University School of Medicine, Reference # 2020–331, University of Illinois College of Medicine), IRB Protocol # 2012–0783, Ohio State University College of Medicine, Study ID# 2020E0463, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Reference # 20200527-SOM-LAN-1, University of California Irvine School of Medicine, submitted self-exemption IRB form. In accordance with the IRB exemption approval, each survey participant received an email consent describing the study and their optional participation.

Consent for publication

This manuscript does not contain any individualized person’s data, therefore consent for publication was not necessary according to the IRB exemption approval.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: table s1..

Survey Instrument

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Harries, A.J., Lee, C., Jones, L. et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students: a multicenter quantitative study. BMC Med Educ 21 , 14 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02462-1

Download citation

Received : 29 July 2020

Accepted : 16 December 2020

Published : 06 January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02462-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Undergraduate medical education

- COVID-19 pandemic

- Medical student anxiety

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology