How to create a helpful research paper outline

Last updated

21 December 2023

Reviewed by

You need to structure your research paper in an orderly way that makes it easy for readers to follow your reasoning and supporting data. That's where a research paper outline can help.

Writing a research paper outline will help you arrange your ideas logically and allow your final paper to flow. It will make the entire process more manageable and help you work out which details to include and which are better left out.

- What is a research paper outline?

Write your research paper outline before starting your first draft. The outline provides a map of how you will structure your ideas throughout the paper. A research paper outline will help you to be more efficient when ordering the sections of your thesis, rather than trying to make structural changes after finishing an entire first draft.

An outline consists of the main topics and subtopics of your paper, listed in a logical order. The main topics will become the sections of your research paper, and the subtopics reveal the content you want to include or discuss under the main topics.

Under each subtopic, you can also jot down items you don't want to forget to include in your research paper, such as:

Topic ideas

Paragraph ideas

Direct quotes

Once you start listing these under your main topics, you can focus your thoughts as you plan and write the research paper using the evidence and data you collected and any additional information.

- Why use an outline?

If your research paper does not have a clear, logical order, readers may not understand the ideas you're trying to share, or they may lose interest and not bother to read the whole paper. An outline helps you structure your research paper so readers can easily connect the content, ideas, and theories you're trying to prove or maintain.

- Are there different kinds of research paper outlines?

Different kinds of research paper outlines might seem similar but have different purposes. You can select an outline type that provides a clear road map and thoroughly explores each point.

Other types will help structure content logically or with a segmented flow and progression of ideas that align closely with the theme of your research.

- The 3 types of outlines

The three outline formats available to research paper writers are:

Alphanumeric or topic outlines

Sentence or full-sentence outlines

Decimal outlines

Let’s look at the differences between each type and see how one may be more beneficial than another, depending on the nature of your research.

This type of research paper outline allows you to segment main headings and subheadings with an alphanumeric arrangement.

The alphanumeric characters of Roman numerals, capital letters, numbers, and lowercase letters define the hierarchy of main topic headings, subtopic headings, and third- and fourth-tier subtopic headings. (e.g., I, A, 1, a)

This method uses minimal words to describe the main and subtopic headings. You'll mostly use this type of research paper outline to focus on the organization of the content while allowing you to review it for unrelated or irrelevant information.

Full-sentence outlines

You will format this type of research paper outline as an alphanumeric outline, using the same alphanumeric characters. However, it contains complete sentences rather than a few words for each main and subtopic heading.

This formatting method allows the writer to focus on looking for inaccuracies and inconsistencies in each point before starting the first draft.

Instead of using alphanumeric characters to define main headings, subheadings, and third- and fourth-tier subheadings, the decimal outline uses a decimal numbering system.

This system shows a logical progression of the content by using 1.0 for the main section heading (and 2.0, 3.0, etc., for subsequent sections), 1.1 for the subheading, 1.1.1 for a third-tier subheading, and 1.1.1.1 for the fourth-tier subheading.

The headings and subheadings will be just a few words, as in the alphanumerical research paper outline. Decimal outlines allow the writer to focus on the content's overall coherence, increasing your writing efficiency and reducing the time it takes to write your research paper.

- How to write a research paper outline

Before you begin your research paper outline, you need to determine your topic and gather your information. Let’s look at these steps first, then dive into how to write your outline.

1. Determine your topic

You'll need to establish a topic or the main point you intend to write about.

For example, you may want to research and write about whether influencers are the most beneficial way to promote products in your industry. This topic is the main point around which your essay will revolve.

2. Gather information

You'll need evidence, data, statistics, and facts to prove or disprove that influencers are the best method of promoting products in your industry.

You'll insert any of these things you collect to substantiate your findings into the outline to support your topic.

3. Determine the type of essay you'll be writing

There are many types of essays or research papers you can write. The kinds of essays include:

Argumentative: Builds logic and support for an argument

Cause and effect: Explains relationships between specific conditions and their results

Analytical: Presents a claim on what is being analyzed

Interpretive: Informative and persuasive explanations on how something is perceived

Experimental: Reports on experimental results and the reasoning behind the results

Review: Offers an understanding and analysis of primary sources on a given topic

Definition: Defines what a term or concept means

Persuasive: Uses logic and reason to show that one idea is more justified than another

Narrative: Tells a story of personal experience from the author’s point of view

Expository: Shows an objective view of a subject by exploring various angles

Descriptive: Describes objects, people, places, experiences, emotions, situations, etc.

Once you understand the essay format you are writing, you'll know how to structure your outline.

4. Include basic sections

You'll begin to structure your outline using basic sections. Your main topic headings for these sections may include an introduction, multiple body paragraph sections, and a conclusion.

Once you establish the sections, you can insert the subtopics under each main topic heading.

5. Organize your outline

For example, if you're writing an argumentative essay taking the position that brand influencers (e.g., social media stars on Instagram or TikTok) are the best way to promote products in your industry, you will argue for that particular position.

You'll organize your argumentative essay outline with a main topic section supporting the position. The subtopics will include the reasoning behind your arguments, and the third-tier subtopics will contain the supporting evidence and data you gathered during your research.

You'll add another main topic section to counter and respond to any opposing arguments. Once you've organized and included all the information in this way, this will provide the structure to start your argumentative essay draft.

6. Consider compare-and-contrast essays

A compare-and-contrast essay is a form of essay that analyzes the differences between two opposing theories or subjects. If you have multiple subjects that are the same or different in just one aspect, you can write a point-by-point outline exploring each subject in terms of this characteristic.

The main topic headings will list that one characteristic, and the subtopic headings will list the subjects or items that are the same or different in relation to this characteristic.

Conversely, if you have multiple items to compare, but they have many characteristics that are similar or different, you can write a block method outline. The main topic headings will contain the items to be compared, while the subtopic headings will contain the aspects in which they are similar or different.

7. Consider advanced organizers for longer essays

An advanced organizer is a sentence that introduces new topics by connecting already-known information to new information. It can also prepare the reader for what they may expect to learn from the entire essay, or each section or paragraph.

Incorporating advanced organizers makes it easier for the reader to process and understand the information you are trying to convey. If you choose to use advanced organizers, depending on how often you want to use them throughout your paper, you can add them to your outline at the end of the introduction, the beginning of a section, or the beginning of each paragraph.

- Do outlines need periods (full stops)?

If you're constructing alphanumerical or decimal topic outlines, they do not need periods because the entries are usually not complete sentences. However, outlines containing full sentences will need to be punctuated as any sentence is, including using periods.

- An example research paper outline

Here is an example of an alphanumerical outline that argues brand influencers are the best method of promoting products in a particular industry:

I. Introduction

A. Background information about the issue and the position being argued.

B. Thesis statement: Influencers are the best way to promote products in this industry.

II. Reasons that support the thesis statement

A. Reason or argument #1

1. Supporting evidence

2. Supporting evidence

B. Reason or argument #2

C. Reason or argument #3

1. Supporting evidence

2. Supporting evidence

III. Counterarguments and responses

A. Arguments from the other point of view

B. Rebuttals against those arguments

IV. Conclusion

- How long is a thesis outline?

There is no set length for a research paper outline or thesis outline. Your outline can be as long as it needs to be to organize your thoughts constructively.

You can start with a short outline containing an introduction , background, methodology, data and analysis, and conclusion. Or you can break these sections into more specific segments according to the content you want to share.

Why make writing a research paper more complicated than it needs to be? Knowing the elements of an outline and how to insert them into a cohesive structure will make your final paper understandable and interesting to the reader.

Understanding how to outline a research paper will make the writing process more efficient and less time-consuming.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 7 March 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Applied Statistics

11. Statistical report writing

Learning to write useful, productive and readable statistical reports is a critical data analysis skill.

- Undergraduate Statistics Project

- Statistical Report Writing

- The book R eport Writing for Data Science in R by Roger D. Peng (freely dowloaded from LeanPub) is a useful reference for statistical report writing, especially when using the R programming language.

- The book C ommunicating with Data by Deborah Nolan and Sara Stoudt consists of five parts. Part I helps the novice learn to write by reading the work of others. Part II delves into the specifics of how to describe data at a level appropriate for publication, create informative and effective visualizations, and communicate an analysis pipeline through well-written, reproducible code. Part III demonstrates how to reduce a data analysis to a compelling story and organize and write the first draft of a technical paper. Part IV addresses revision; this includes advice on writing about statistical findings in a clear and accurate way, general writing advice, and strategies for proof reading and revising. Part V offers advice about communication strategies beyond the page, which include giving talks, building a professional network, and participating in online communities

One model for a self-contained statistical report, especially one containing empirical methods, has the following sections:

- Give an informative title to your project.

- Assessment : Does the title give an accurate preview of what the report is about? Is it informative, specific and precise?

- The abstract provides a brief summary of the paper (background, methods, results and conclusions). The suggested length is no more than 150 words. This allows you approximately 1 sentence (and likely no more than 2 sentences) summarizing each of the following sections. Typically, abstracts are the last thing you write.

- Assessment : Are the main points of the report described clearly and succinctly?

- In this section you are providing the background of the report – the topic for analysis – and arguing its significance. Well-accepted facts or referenced statements should serve as the majority of content of this section. Typically, the background and significance section starts very broad and moves towards the specific area of analysis.

- Assessment :

Does the background and significance have a logical organization? Does it move from the general to the specific?

Has sufficient background been provided to understand the report?

Does this section end with statements about the goals of the report?

- Data collection . Explain how the data was collected/experiment was conducted.

- Variable creation . Detail the variables in your analysis and how they are defined (if necessary). For example, if you created a combined (frequency times quantity) drinking variable you should describe how. If you are talking about gender no further explanation is really needed.

- Analytic Methods . Explain the statistical procedures that will be used to analyze your data. E.g. Boxplots are used to illustrate differences in GPA across gender and class standing. Correlations are used to assess the impacts of gender and class standing on GPA.

- Assessment : Could the study be repeated based on the information given here? Is the material organized into logical categories (like those above)?

- Typically, results sections start with descriptive statistics, e.g. what percent of the sample is male/female, what is the mean GPA overall, in the different groups, etc. Figures can be nice to illustrate these differences! However, information presented must be relevant in helping to answer the research question(s) of interest. Typically, inferential (i.e. hypothesis tests) statistics come next. Tables can often be helpful for results from multiple regression. Do not give computer output here! This should look like a peer-reviewed journal article results section. Tables and figures should be labeled, embedded in the text, and referenced appropriately. The results section typically makes for fairly dry reading. It does not explain the impact of findings, it merely highlights and reports statistical information.

Is the content appropriate for a results section? Is there a clear description of the results?

Are the results/data analyzed well? Given the data in each figure/table is the interpretation accurate and logical? Is the analysis of the data thorough? Is anything relevant ignored?

Are the figures/tables appropriate for the data being discussed? Are the figure legends and titles clear and concise?

- Restate your objective and draw connections between your analyses and objective. In other words, how did (or didn’t) you answer/address your objective. Place these all in the larger scope of the relevant chapter of the text. Talk about the limitations of your findings and possible areas for future research to better investigate your research question. End with a concluding sentence or two that summarizes your key findings and impact on the field.

Do you clearly state whether the results answer any question posed?

Were specific data cited from the results to support each interpretation? Do you clearly articulate the basis for supporting or rejecting any hypotheses?

- You can copy & paste different style references from Google Scholar: here’s an example (click on the “Cite” link to see the different style citations).

- Assessment : Are references appropriate and of adequate quality? Are the cited properly (both in the text and at the end of the paper)?

Writing quality

- Is your report well-organized, with paragraphs organized in a logical manner?

- Is each paragraph well-written, with a clear topic sentence, and single major point?

- Is your report generally well-written, with good use of language, and sentence structure?

- Are tables and figures labeled correctly and referenced accordingly?

- Does the entire report flow and answer any question(s) sufficiently?

- Is there extraneous information presented (if so, delete it)?

Advice on writing statistical reports

Andrew Gelman

Andrew Gelman , Professor of Statistics and Political Science and Director of the Applied Statistics Center at Columbia University, wrote the following as a guide to preparing statistical research articles; it works equally well for writing statistical reports.

Please try to follow it, and see how your planning for writing for, and actual writing of, statistical reports improves:

- Start writing the conclusions (the final part of your report, before the references). Write up to a couple pages on what you’ve found and what you recommend. In writing these conclusions, you should also be writing some of the introduction, in that you’ll need to give enough background so that general readers can understand what you’re talking about and why they should care. But you want to start with the conclusions, because that will determine what sort of background information you’ll need to give.

- Now step back. What is the principal evidence for your conclusions? Make some graphs and pull out some key numbers that represent your research findings which back up your claims.

- Back one more step, now. What are the methods and data you used to obtain your findings?

- Now go back and write the literature review and the introduction .

- Moving forward one last time: go to your results and conclusions and give alternative explanations . Why might you be wrong? What are the limits of applicability of your findings? What future work would be appropriate to follow up on these loose ends?

- Write the abstract . An easy way to start is to take the first sentence from each of the first five paragraphs of the article. This probably won’t be quite right, but I bet it will be close to what you need.

- Give the article to a friend, ask them to spend 15 minutes looking at it, then ask what they think your message was, and what evidence you have for it. Your friend should read the article as a potential consumer, not as a critic. You can find typos on your own time, but you need somebody else’s eyes to get a sense of the message you’re sending.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

The Beginner's Guide to Statistical Analysis | 5 Steps & Examples

Statistical analysis means investigating trends, patterns, and relationships using quantitative data . It is an important research tool used by scientists, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

To draw valid conclusions, statistical analysis requires careful planning from the very start of the research process . You need to specify your hypotheses and make decisions about your research design, sample size, and sampling procedure.

After collecting data from your sample, you can organize and summarize the data using descriptive statistics . Then, you can use inferential statistics to formally test hypotheses and make estimates about the population. Finally, you can interpret and generalize your findings.

This article is a practical introduction to statistical analysis for students and researchers. We’ll walk you through the steps using two research examples. The first investigates a potential cause-and-effect relationship, while the second investigates a potential correlation between variables.

Table of contents

Step 1: write your hypotheses and plan your research design, step 2: collect data from a sample, step 3: summarize your data with descriptive statistics, step 4: test hypotheses or make estimates with inferential statistics, step 5: interpret your results, other interesting articles.

To collect valid data for statistical analysis, you first need to specify your hypotheses and plan out your research design.

Writing statistical hypotheses

The goal of research is often to investigate a relationship between variables within a population . You start with a prediction, and use statistical analysis to test that prediction.

A statistical hypothesis is a formal way of writing a prediction about a population. Every research prediction is rephrased into null and alternative hypotheses that can be tested using sample data.

While the null hypothesis always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

- Null hypothesis: A 5-minute meditation exercise will have no effect on math test scores in teenagers.

- Alternative hypothesis: A 5-minute meditation exercise will improve math test scores in teenagers.

- Null hypothesis: Parental income and GPA have no relationship with each other in college students.

- Alternative hypothesis: Parental income and GPA are positively correlated in college students.

Planning your research design

A research design is your overall strategy for data collection and analysis. It determines the statistical tests you can use to test your hypothesis later on.

First, decide whether your research will use a descriptive, correlational, or experimental design. Experiments directly influence variables, whereas descriptive and correlational studies only measure variables.

- In an experimental design , you can assess a cause-and-effect relationship (e.g., the effect of meditation on test scores) using statistical tests of comparison or regression.

- In a correlational design , you can explore relationships between variables (e.g., parental income and GPA) without any assumption of causality using correlation coefficients and significance tests.

- In a descriptive design , you can study the characteristics of a population or phenomenon (e.g., the prevalence of anxiety in U.S. college students) using statistical tests to draw inferences from sample data.

Your research design also concerns whether you’ll compare participants at the group level or individual level, or both.

- In a between-subjects design , you compare the group-level outcomes of participants who have been exposed to different treatments (e.g., those who performed a meditation exercise vs those who didn’t).

- In a within-subjects design , you compare repeated measures from participants who have participated in all treatments of a study (e.g., scores from before and after performing a meditation exercise).

- In a mixed (factorial) design , one variable is altered between subjects and another is altered within subjects (e.g., pretest and posttest scores from participants who either did or didn’t do a meditation exercise).

- Experimental

- Correlational

First, you’ll take baseline test scores from participants. Then, your participants will undergo a 5-minute meditation exercise. Finally, you’ll record participants’ scores from a second math test.

In this experiment, the independent variable is the 5-minute meditation exercise, and the dependent variable is the math test score from before and after the intervention. Example: Correlational research design In a correlational study, you test whether there is a relationship between parental income and GPA in graduating college students. To collect your data, you will ask participants to fill in a survey and self-report their parents’ incomes and their own GPA.

Measuring variables

When planning a research design, you should operationalize your variables and decide exactly how you will measure them.

For statistical analysis, it’s important to consider the level of measurement of your variables, which tells you what kind of data they contain:

- Categorical data represents groupings. These may be nominal (e.g., gender) or ordinal (e.g. level of language ability).

- Quantitative data represents amounts. These may be on an interval scale (e.g. test score) or a ratio scale (e.g. age).

Many variables can be measured at different levels of precision. For example, age data can be quantitative (8 years old) or categorical (young). If a variable is coded numerically (e.g., level of agreement from 1–5), it doesn’t automatically mean that it’s quantitative instead of categorical.

Identifying the measurement level is important for choosing appropriate statistics and hypothesis tests. For example, you can calculate a mean score with quantitative data, but not with categorical data.

In a research study, along with measures of your variables of interest, you’ll often collect data on relevant participant characteristics.

| Variable | Type of data |

|---|---|

| Age | Quantitative (ratio) |

| Gender | Categorical (nominal) |

| Race or ethnicity | Categorical (nominal) |

| Baseline test scores | Quantitative (interval) |

| Final test scores | Quantitative (interval) |

| Parental income | Quantitative (ratio) |

|---|---|

| GPA | Quantitative (interval) |

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

In most cases, it’s too difficult or expensive to collect data from every member of the population you’re interested in studying. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

Statistical analysis allows you to apply your findings beyond your own sample as long as you use appropriate sampling procedures . You should aim for a sample that is representative of the population.

Sampling for statistical analysis

There are two main approaches to selecting a sample.

- Probability sampling: every member of the population has a chance of being selected for the study through random selection.

- Non-probability sampling: some members of the population are more likely than others to be selected for the study because of criteria such as convenience or voluntary self-selection.

In theory, for highly generalizable findings, you should use a probability sampling method. Random selection reduces several types of research bias , like sampling bias , and ensures that data from your sample is actually typical of the population. Parametric tests can be used to make strong statistical inferences when data are collected using probability sampling.

But in practice, it’s rarely possible to gather the ideal sample. While non-probability samples are more likely to at risk for biases like self-selection bias , they are much easier to recruit and collect data from. Non-parametric tests are more appropriate for non-probability samples, but they result in weaker inferences about the population.

If you want to use parametric tests for non-probability samples, you have to make the case that:

- your sample is representative of the population you’re generalizing your findings to.

- your sample lacks systematic bias.

Keep in mind that external validity means that you can only generalize your conclusions to others who share the characteristics of your sample. For instance, results from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic samples (e.g., college students in the US) aren’t automatically applicable to all non-WEIRD populations.

If you apply parametric tests to data from non-probability samples, be sure to elaborate on the limitations of how far your results can be generalized in your discussion section .

Create an appropriate sampling procedure

Based on the resources available for your research, decide on how you’ll recruit participants.

- Will you have resources to advertise your study widely, including outside of your university setting?

- Will you have the means to recruit a diverse sample that represents a broad population?

- Do you have time to contact and follow up with members of hard-to-reach groups?

Your participants are self-selected by their schools. Although you’re using a non-probability sample, you aim for a diverse and representative sample. Example: Sampling (correlational study) Your main population of interest is male college students in the US. Using social media advertising, you recruit senior-year male college students from a smaller subpopulation: seven universities in the Boston area.

Calculate sufficient sample size

Before recruiting participants, decide on your sample size either by looking at other studies in your field or using statistics. A sample that’s too small may be unrepresentative of the sample, while a sample that’s too large will be more costly than necessary.

There are many sample size calculators online. Different formulas are used depending on whether you have subgroups or how rigorous your study should be (e.g., in clinical research). As a rule of thumb, a minimum of 30 units or more per subgroup is necessary.

To use these calculators, you have to understand and input these key components:

- Significance level (alpha): the risk of rejecting a true null hypothesis that you are willing to take, usually set at 5%.

- Statistical power : the probability of your study detecting an effect of a certain size if there is one, usually 80% or higher.

- Expected effect size : a standardized indication of how large the expected result of your study will be, usually based on other similar studies.

- Population standard deviation: an estimate of the population parameter based on a previous study or a pilot study of your own.

Once you’ve collected all of your data, you can inspect them and calculate descriptive statistics that summarize them.

Inspect your data

There are various ways to inspect your data, including the following:

- Organizing data from each variable in frequency distribution tables .

- Displaying data from a key variable in a bar chart to view the distribution of responses.

- Visualizing the relationship between two variables using a scatter plot .

By visualizing your data in tables and graphs, you can assess whether your data follow a skewed or normal distribution and whether there are any outliers or missing data.

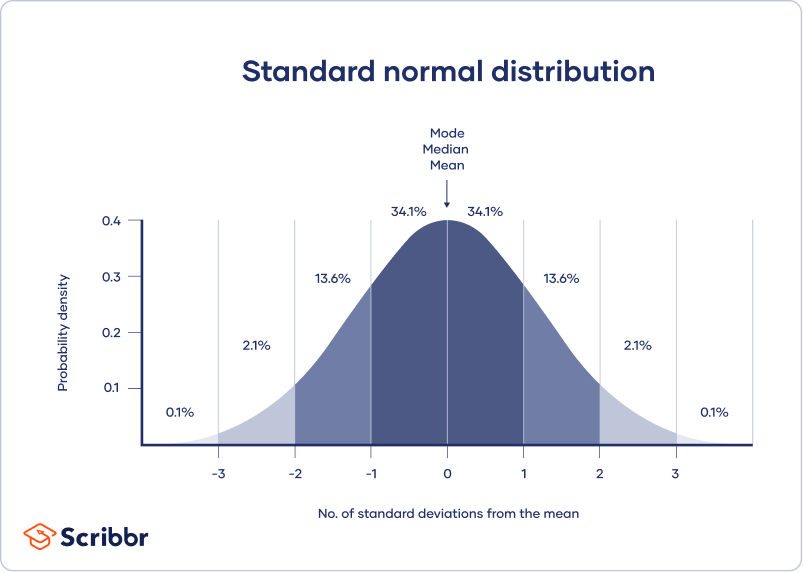

A normal distribution means that your data are symmetrically distributed around a center where most values lie, with the values tapering off at the tail ends.

In contrast, a skewed distribution is asymmetric and has more values on one end than the other. The shape of the distribution is important to keep in mind because only some descriptive statistics should be used with skewed distributions.

Extreme outliers can also produce misleading statistics, so you may need a systematic approach to dealing with these values.

Calculate measures of central tendency

Measures of central tendency describe where most of the values in a data set lie. Three main measures of central tendency are often reported:

- Mode : the most popular response or value in the data set.

- Median : the value in the exact middle of the data set when ordered from low to high.

- Mean : the sum of all values divided by the number of values.

However, depending on the shape of the distribution and level of measurement, only one or two of these measures may be appropriate. For example, many demographic characteristics can only be described using the mode or proportions, while a variable like reaction time may not have a mode at all.

Calculate measures of variability

Measures of variability tell you how spread out the values in a data set are. Four main measures of variability are often reported:

- Range : the highest value minus the lowest value of the data set.

- Interquartile range : the range of the middle half of the data set.

- Standard deviation : the average distance between each value in your data set and the mean.

- Variance : the square of the standard deviation.

Once again, the shape of the distribution and level of measurement should guide your choice of variability statistics. The interquartile range is the best measure for skewed distributions, while standard deviation and variance provide the best information for normal distributions.

Using your table, you should check whether the units of the descriptive statistics are comparable for pretest and posttest scores. For example, are the variance levels similar across the groups? Are there any extreme values? If there are, you may need to identify and remove extreme outliers in your data set or transform your data before performing a statistical test.

| Pretest scores | Posttest scores | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 68.44 | 75.25 |

| Standard deviation | 9.43 | 9.88 |

| Variance | 88.96 | 97.96 |

| Range | 36.25 | 45.12 |

| 30 | ||

From this table, we can see that the mean score increased after the meditation exercise, and the variances of the two scores are comparable. Next, we can perform a statistical test to find out if this improvement in test scores is statistically significant in the population. Example: Descriptive statistics (correlational study) After collecting data from 653 students, you tabulate descriptive statistics for annual parental income and GPA.

It’s important to check whether you have a broad range of data points. If you don’t, your data may be skewed towards some groups more than others (e.g., high academic achievers), and only limited inferences can be made about a relationship.

| Parental income (USD) | GPA | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 62,100 | 3.12 |

| Standard deviation | 15,000 | 0.45 |

| Variance | 225,000,000 | 0.16 |

| Range | 8,000–378,000 | 2.64–4.00 |

| 653 | ||

A number that describes a sample is called a statistic , while a number describing a population is called a parameter . Using inferential statistics , you can make conclusions about population parameters based on sample statistics.

Researchers often use two main methods (simultaneously) to make inferences in statistics.

- Estimation: calculating population parameters based on sample statistics.

- Hypothesis testing: a formal process for testing research predictions about the population using samples.

You can make two types of estimates of population parameters from sample statistics:

- A point estimate : a value that represents your best guess of the exact parameter.

- An interval estimate : a range of values that represent your best guess of where the parameter lies.

If your aim is to infer and report population characteristics from sample data, it’s best to use both point and interval estimates in your paper.

You can consider a sample statistic a point estimate for the population parameter when you have a representative sample (e.g., in a wide public opinion poll, the proportion of a sample that supports the current government is taken as the population proportion of government supporters).

There’s always error involved in estimation, so you should also provide a confidence interval as an interval estimate to show the variability around a point estimate.

A confidence interval uses the standard error and the z score from the standard normal distribution to convey where you’d generally expect to find the population parameter most of the time.

Hypothesis testing

Using data from a sample, you can test hypotheses about relationships between variables in the population. Hypothesis testing starts with the assumption that the null hypothesis is true in the population, and you use statistical tests to assess whether the null hypothesis can be rejected or not.

Statistical tests determine where your sample data would lie on an expected distribution of sample data if the null hypothesis were true. These tests give two main outputs:

- A test statistic tells you how much your data differs from the null hypothesis of the test.

- A p value tells you the likelihood of obtaining your results if the null hypothesis is actually true in the population.

Statistical tests come in three main varieties:

- Comparison tests assess group differences in outcomes.

- Regression tests assess cause-and-effect relationships between variables.

- Correlation tests assess relationships between variables without assuming causation.

Your choice of statistical test depends on your research questions, research design, sampling method, and data characteristics.

Parametric tests

Parametric tests make powerful inferences about the population based on sample data. But to use them, some assumptions must be met, and only some types of variables can be used. If your data violate these assumptions, you can perform appropriate data transformations or use alternative non-parametric tests instead.

A regression models the extent to which changes in a predictor variable results in changes in outcome variable(s).

- A simple linear regression includes one predictor variable and one outcome variable.

- A multiple linear regression includes two or more predictor variables and one outcome variable.

Comparison tests usually compare the means of groups. These may be the means of different groups within a sample (e.g., a treatment and control group), the means of one sample group taken at different times (e.g., pretest and posttest scores), or a sample mean and a population mean.

- A t test is for exactly 1 or 2 groups when the sample is small (30 or less).

- A z test is for exactly 1 or 2 groups when the sample is large.

- An ANOVA is for 3 or more groups.

The z and t tests have subtypes based on the number and types of samples and the hypotheses:

- If you have only one sample that you want to compare to a population mean, use a one-sample test .

- If you have paired measurements (within-subjects design), use a dependent (paired) samples test .

- If you have completely separate measurements from two unmatched groups (between-subjects design), use an independent (unpaired) samples test .

- If you expect a difference between groups in a specific direction, use a one-tailed test .

- If you don’t have any expectations for the direction of a difference between groups, use a two-tailed test .

The only parametric correlation test is Pearson’s r . The correlation coefficient ( r ) tells you the strength of a linear relationship between two quantitative variables.

However, to test whether the correlation in the sample is strong enough to be important in the population, you also need to perform a significance test of the correlation coefficient, usually a t test, to obtain a p value. This test uses your sample size to calculate how much the correlation coefficient differs from zero in the population.

You use a dependent-samples, one-tailed t test to assess whether the meditation exercise significantly improved math test scores. The test gives you:

- a t value (test statistic) of 3.00

- a p value of 0.0028

Although Pearson’s r is a test statistic, it doesn’t tell you anything about how significant the correlation is in the population. You also need to test whether this sample correlation coefficient is large enough to demonstrate a correlation in the population.

A t test can also determine how significantly a correlation coefficient differs from zero based on sample size. Since you expect a positive correlation between parental income and GPA, you use a one-sample, one-tailed t test. The t test gives you:

- a t value of 3.08

- a p value of 0.001

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The final step of statistical analysis is interpreting your results.

Statistical significance

In hypothesis testing, statistical significance is the main criterion for forming conclusions. You compare your p value to a set significance level (usually 0.05) to decide whether your results are statistically significant or non-significant.

Statistically significant results are considered unlikely to have arisen solely due to chance. There is only a very low chance of such a result occurring if the null hypothesis is true in the population.

This means that you believe the meditation intervention, rather than random factors, directly caused the increase in test scores. Example: Interpret your results (correlational study) You compare your p value of 0.001 to your significance threshold of 0.05. With a p value under this threshold, you can reject the null hypothesis. This indicates a statistically significant correlation between parental income and GPA in male college students.

Note that correlation doesn’t always mean causation, because there are often many underlying factors contributing to a complex variable like GPA. Even if one variable is related to another, this may be because of a third variable influencing both of them, or indirect links between the two variables.

Effect size

A statistically significant result doesn’t necessarily mean that there are important real life applications or clinical outcomes for a finding.

In contrast, the effect size indicates the practical significance of your results. It’s important to report effect sizes along with your inferential statistics for a complete picture of your results. You should also report interval estimates of effect sizes if you’re writing an APA style paper .

With a Cohen’s d of 0.72, there’s medium to high practical significance to your finding that the meditation exercise improved test scores. Example: Effect size (correlational study) To determine the effect size of the correlation coefficient, you compare your Pearson’s r value to Cohen’s effect size criteria.

Decision errors

Type I and Type II errors are mistakes made in research conclusions. A Type I error means rejecting the null hypothesis when it’s actually true, while a Type II error means failing to reject the null hypothesis when it’s false.

You can aim to minimize the risk of these errors by selecting an optimal significance level and ensuring high power . However, there’s a trade-off between the two errors, so a fine balance is necessary.

Frequentist versus Bayesian statistics

Traditionally, frequentist statistics emphasizes null hypothesis significance testing and always starts with the assumption of a true null hypothesis.

However, Bayesian statistics has grown in popularity as an alternative approach in the last few decades. In this approach, you use previous research to continually update your hypotheses based on your expectations and observations.

Bayes factor compares the relative strength of evidence for the null versus the alternative hypothesis rather than making a conclusion about rejecting the null hypothesis or not.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

Methodology

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Likert scale

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Framing effect

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hostile attribution bias

- Affect heuristic

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- Descriptive Statistics | Definitions, Types, Examples

- Inferential Statistics | An Easy Introduction & Examples

- Choosing the Right Statistical Test | Types & Examples

More interesting articles

- Akaike Information Criterion | When & How to Use It (Example)

- An Easy Introduction to Statistical Significance (With Examples)

- An Introduction to t Tests | Definitions, Formula and Examples

- ANOVA in R | A Complete Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Central Limit Theorem | Formula, Definition & Examples

- Central Tendency | Understanding the Mean, Median & Mode

- Chi-Square (Χ²) Distributions | Definition & Examples

- Chi-Square (Χ²) Table | Examples & Downloadable Table

- Chi-Square (Χ²) Tests | Types, Formula & Examples

- Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test | Formula, Guide & Examples

- Chi-Square Test of Independence | Formula, Guide & Examples

- Coefficient of Determination (R²) | Calculation & Interpretation

- Correlation Coefficient | Types, Formulas & Examples

- Frequency Distribution | Tables, Types & Examples

- How to Calculate Standard Deviation (Guide) | Calculator & Examples

- How to Calculate Variance | Calculator, Analysis & Examples

- How to Find Degrees of Freedom | Definition & Formula

- How to Find Interquartile Range (IQR) | Calculator & Examples

- How to Find Outliers | 4 Ways with Examples & Explanation

- How to Find the Geometric Mean | Calculator & Formula

- How to Find the Mean | Definition, Examples & Calculator

- How to Find the Median | Definition, Examples & Calculator

- How to Find the Mode | Definition, Examples & Calculator

- How to Find the Range of a Data Set | Calculator & Formula

- Hypothesis Testing | A Step-by-Step Guide with Easy Examples

- Interval Data and How to Analyze It | Definitions & Examples

- Levels of Measurement | Nominal, Ordinal, Interval and Ratio

- Linear Regression in R | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- Missing Data | Types, Explanation, & Imputation

- Multiple Linear Regression | A Quick Guide (Examples)

- Nominal Data | Definition, Examples, Data Collection & Analysis

- Normal Distribution | Examples, Formulas, & Uses

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses | Definitions & Examples

- One-way ANOVA | When and How to Use It (With Examples)

- Ordinal Data | Definition, Examples, Data Collection & Analysis

- Parameter vs Statistic | Definitions, Differences & Examples

- Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) | Guide & Examples

- Poisson Distributions | Definition, Formula & Examples

- Probability Distribution | Formula, Types, & Examples

- Quartiles & Quantiles | Calculation, Definition & Interpretation

- Ratio Scales | Definition, Examples, & Data Analysis

- Simple Linear Regression | An Easy Introduction & Examples

- Skewness | Definition, Examples & Formula

- Statistical Power and Why It Matters | A Simple Introduction

- Student's t Table (Free Download) | Guide & Examples

- T-distribution: What it is and how to use it

- Test statistics | Definition, Interpretation, and Examples

- The Standard Normal Distribution | Calculator, Examples & Uses

- Two-Way ANOVA | Examples & When To Use It

- Type I & Type II Errors | Differences, Examples, Visualizations

- Understanding Confidence Intervals | Easy Examples & Formulas

- Understanding P values | Definition and Examples

- Variability | Calculating Range, IQR, Variance, Standard Deviation

- What is Effect Size and Why Does It Matter? (Examples)

- What Is Kurtosis? | Definition, Examples & Formula

- What Is Standard Error? | How to Calculate (Guide with Examples)

What is your plagiarism score?

Reference management. Clean and simple.

Getting started with your research paper outline

Levels of organization for a research paper outline

First level of organization, second level of organization, third level of organization, fourth level of organization, tips for writing a research paper outline, research paper outline template, my research paper outline is complete: what are the next steps, frequently asked questions about a research paper outline, related articles.

The outline is the skeleton of your research paper. Simply start by writing down your thesis and the main ideas you wish to present. This will likely change as your research progresses; therefore, do not worry about being too specific in the early stages of writing your outline.

A research paper outline typically contains between two and four layers of organization. The first two layers are the most generalized. Each layer thereafter will contain the research you complete and presents more and more detailed information.

The levels are typically represented by a combination of Roman numerals, Arabic numerals, uppercase letters, lowercase letters but may include other symbols. Refer to the guidelines provided by your institution, as formatting is not universal and differs between universities, fields, and subjects. If you are writing the outline for yourself, you may choose any combination you prefer.

This is the most generalized level of information. Begin by numbering the introduction, each idea you will present, and the conclusion. The main ideas contain the bulk of your research paper 's information. Depending on your research, it may be chapters of a book for a literature review , a series of dates for a historical research paper, or the methods and results of a scientific paper.

I. Introduction

II. Main idea

III. Main idea

IV. Main idea

V. Conclusion

The second level consists of topics which support the introduction, main ideas, and the conclusion. Each main idea should have at least two supporting topics listed in the outline.

If your main idea does not have enough support, you should consider presenting another main idea in its place. This is where you should stop outlining if this is your first draft. Continue your research before adding to the next levels of organization.

- A. Background information

- B. Hypothesis or thesis

- A. Supporting topic

- B. Supporting topic

The third level of organization contains supporting information for the topics previously listed. By now, you should have completed enough research to add support for your ideas.

The Introduction and Main Ideas may contain information you discovered about the author, timeframe, or contents of a book for a literature review; the historical events leading up to the research topic for a historical research paper, or an explanation of the problem a scientific research paper intends to address.

- 1. Relevant history

- 2. Relevant history

- 1. The hypothesis or thesis clearly stated

- 1. A brief description of supporting information

- 2. A brief description of supporting information

The fourth level of organization contains the most detailed information such as quotes, references, observations, or specific data needed to support the main idea. It is not typical to have further levels of organization because the information contained here is the most specific.

- a) Quotes or references to another piece of literature

- b) Quotes or references to another piece of literature

Tip: The key to creating a useful outline is to be consistent in your headings, organization, and levels of specificity.

- Be Consistent : ensure every heading has a similar tone. State the topic or write short sentences for each heading but avoid doing both.

- Organize Information : Higher levels of organization are more generally stated and each supporting level becomes more specific. The introduction and conclusion will never be lower than the first level of organization.

- Build Support : Each main idea should have two or more supporting topics. If your research does not have enough information to support the main idea you are presenting, you should, in general, complete additional research or revise the outline.

By now, you should know the basic requirements to create an outline for your paper. With a content framework in place, you can now start writing your paper . To help you start right away, you can use one of our templates and adjust it to suit your needs.

After completing your outline, you should:

- Title your research paper . This is an iterative process and may change when you delve deeper into the topic.

- Begin writing your research paper draft . Continue researching to further build your outline and provide more information to support your hypothesis or thesis.

- Format your draft appropriately . MLA 8 and APA 7 formats have differences between their bibliography page, in-text citations, line spacing, and title.

- Finalize your citations and bibliography . Use a reference manager like Paperpile to organize and cite your research.

- Write the abstract, if required . An abstract will briefly state the information contained within the paper, results of the research, and the conclusion.

An outline is used to organize written ideas about a topic into a logical order. Outlines help us organize major topics, subtopics, and supporting details. Researchers benefit greatly from outlines while writing by addressing which topic to cover in what order.

The most basic outline format consists of: an introduction, a minimum of three topic paragraphs, and a conclusion.

You should make an outline before starting to write your research paper. This will help you organize the main ideas and arguments you want to present in your topic.

- Consistency: ensure every heading has a similar tone. State the topic or write short sentences for each heading but avoid doing both.

- Organization : Higher levels of organization are more generally stated and each supporting level becomes more specific. The introduction and conclusion will never be lower than the first level of organization.

- Support : Each main idea should have two or more supporting topics. If your research does not have enough information to support the main idea you are presenting, you should, in general, complete additional research or revise the outline.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper Outline – Types, Example, Template

Research Paper Outline – Types, Example, Template

Table of Contents

By creating a well-structured research paper outline, writers can easily organize their thoughts and ideas and ensure that their final paper is clear, concise, and effective. In this article, we will explore the essential components of a research paper outline and provide some tips and tricks for creating a successful one.

Research Paper Outline

Research paper outline is a plan or a structural framework that organizes the main ideas , arguments, and supporting evidence in a logical sequence. It serves as a blueprint or a roadmap for the writer to follow while drafting the actual research paper .

Typically, an outline consists of the following elements:

- Introduction : This section presents the topic, research question , and thesis statement of the paper. It also provides a brief overview of the literature review and the methodology used.

- Literature Review: This section provides a comprehensive review of the relevant literature, theories, and concepts related to the research topic. It analyzes the existing research and identifies the research gaps and research questions.

- Methodology: This section explains the research design, data collection methods, data analysis, and ethical considerations of the study.

- Results: This section presents the findings of the study, using tables, graphs, and statistics to illustrate the data.

- Discussion : This section interprets the results of the study, and discusses their implications, significance, and limitations. It also suggests future research directions.

- Conclusion : This section summarizes the main findings of the study and restates the thesis statement.

- References: This section lists all the sources cited in the paper using the appropriate citation style.

Research Paper Outline Types

There are several types of outlines that can be used for research papers, including:

Alphanumeric Outline

This is a traditional outline format that uses Roman numerals, capital letters, Arabic numerals, and lowercase letters to organize the main ideas and supporting details of a research paper. It is commonly used for longer, more complex research papers.

I. Introduction

- A. Background information

- B. Thesis statement

- 1 1. Supporting detail

- 1 2. Supporting detail 2

- 2 1. Supporting detail

III. Conclusion

- A. Restate thesis

- B. Summarize main points

Decimal Outline

This outline format uses numbers to organize the main ideas and supporting details of a research paper. It is similar to the alphanumeric outline, but it uses only numbers and decimals to indicate the hierarchy of the ideas.

- 1.1 Background information

- 1.2 Thesis statement

- 1 2.1.1 Supporting detail

- 1 2.1.2 Supporting detail

- 2 2.2.1 Supporting detail

- 1 2.2.2 Supporting detail

- 3.1 Restate thesis

- 3.2 Summarize main points

Full Sentence Outline

This type of outline uses complete sentences to describe the main ideas and supporting details of a research paper. It is useful for those who prefer to see the entire paper outlined in complete sentences.

- Provide background information on the topic

- State the thesis statement

- Explain main idea 1 and provide supporting details

- Discuss main idea 2 and provide supporting details

- Restate the thesis statement

- Summarize the main points of the paper

Topic Outline

This type of outline uses short phrases or words to describe the main ideas and supporting details of a research paper. It is useful for those who prefer to see a more concise overview of the paper.

- Background information

- Thesis statement

- Supporting detail 1

- Supporting detail 2

- Restate thesis

- Summarize main points

Reverse Outline

This is an outline that is created after the paper has been written. It involves going back through the paper and summarizing each paragraph or section in one sentence. This can be useful for identifying gaps in the paper or areas that need further development.

- Introduction : Provides background information and states the thesis statement.

- Paragraph 1: Discusses main idea 1 and provides supporting details.

- Paragraph 2: Discusses main idea 2 and provides supporting details.

- Paragraph 3: Addresses potential counterarguments.

- Conclusion : Restates thesis and summarizes main points.

Mind Map Outline

This type of outline involves creating a visual representation of the main ideas and supporting details of a research paper. It can be useful for those who prefer a more creative and visual approach to outlining.

- Supporting detail 1: Lack of funding for public schools.

- Supporting detail 2: Decrease in government support for education.

- Supporting detail 1: Increase in income inequality.

- Supporting detail 2: Decrease in social mobility.

Research Paper Outline Example

Research Paper Outline Example on Cyber Security:

A. Overview of Cybersecurity

- B. Importance of Cybersecurity

- C. Purpose of the paper

II. Cyber Threats

A. Definition of Cyber Threats

- B. Types of Cyber Threats

- C. Examples of Cyber Threats

III. Cybersecurity Measures

A. Prevention measures

- Anti-virus software

- Encryption B. Detection measures

- Intrusion Detection System (IDS)

- Security Information and Event Management (SIEM)

- Security Operations Center (SOC) C. Response measures

- Incident Response Plan

- Business Continuity Plan

- Disaster Recovery Plan

IV. Cybersecurity in the Business World

A. Overview of Cybersecurity in the Business World

B. Cybersecurity Risk Assessment

C. Best Practices for Cybersecurity in Business

V. Cybersecurity in Government Organizations

A. Overview of Cybersecurity in Government Organizations

C. Best Practices for Cybersecurity in Government Organizations

VI. Cybersecurity Ethics

A. Definition of Cybersecurity Ethics

B. Importance of Cybersecurity Ethics

C. Examples of Cybersecurity Ethics

VII. Future of Cybersecurity

A. Overview of the Future of Cybersecurity

B. Emerging Cybersecurity Threats

C. Advancements in Cybersecurity Technology

VIII. Conclusion

A. Summary of the paper

B. Recommendations for Cybersecurity

- C. Conclusion.

IX. References

A. List of sources cited in the paper

B. Bibliography of additional resources

Introduction

Cybersecurity refers to the protection of computer systems, networks, and sensitive data from unauthorized access, theft, damage, or any other form of cyber attack. B. Importance of Cybersecurity The increasing reliance on technology and the growing number of cyber threats make cybersecurity an essential aspect of modern society. Cybersecurity breaches can result in financial losses, reputational damage, and legal liabilities. C. Purpose of the paper This paper aims to provide an overview of cybersecurity, cyber threats, cybersecurity measures, cybersecurity in the business and government sectors, cybersecurity ethics, and the future of cybersecurity.

A cyber threat is any malicious act or event that attempts to compromise or disrupt computer systems, networks, or sensitive data. B. Types of Cyber Threats Common types of cyber threats include malware, phishing, social engineering, ransomware, DDoS attacks, and advanced persistent threats (APTs). C. Examples of Cyber Threats Recent cyber threats include the SolarWinds supply chain attack, the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack, and the Microsoft Exchange Server hack.

Prevention measures aim to minimize the risk of cyber attacks by implementing security controls, such as firewalls, anti-virus software, and encryption.

- Firewalls Firewalls act as a barrier between a computer network and the internet, filtering incoming and outgoing traffic to prevent unauthorized access.

- Anti-virus software Anti-virus software detects, prevents, and removes malware from computer systems.

- Encryption Encryption involves the use of mathematical algorithms to transform sensitive data into a code that can only be accessed by authorized individuals. B. Detection measures Detection measures aim to identify and respond to cyber attacks as quickly as possible, such as intrusion detection systems (IDS), security information and event management (SIEM), and security operations centers (SOCs).

- Intrusion Detection System (IDS) IDS monitors network traffic for signs of unauthorized access, such as unusual patterns or anomalies.

- Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) SIEM combines security information management and security event management to provide real-time monitoring and analysis of security alerts.

- Security Operations Center (SOC) SOC is a dedicated team responsible for monitoring, analyzing, and responding to cyber threats. C. Response measures Response measures aim to mitigate the impact of a cyber attack and restore normal operations, such as incident response plans (IRPs), business continuity plans (BCPs), and disaster recovery plans (DRPs).

- Incident Response Plan IRPs outline the procedures and protocols to follow in the event of a cyber attack, including communication protocols, roles and responsibilities, and recovery processes.

- Business Continuity Plan BCPs ensure that critical business functions can continue in the event of a cyber attack or other disruption.

- Disaster Recovery Plan DRPs outline the procedures to recover from a catastrophic event, such as a natural disaster or cyber attack.

Cybersecurity is crucial for businesses of all sizes and industries, as they handle sensitive data, financial transactions, and intellectual property that are attractive targets for cyber criminals.

Risk assessment is a critical step in developing a cybersecurity strategy, which involves identifying potential threats, vulnerabilities, and consequences to determine the level of risk and prioritize security measures.

Best practices for cybersecurity in business include implementing strong passwords and multi-factor authentication, regularly updating software and hardware, training employees on cybersecurity awareness, and regularly backing up data.

Government organizations face unique cybersecurity challenges, as they handle sensitive information related to national security, defense, and critical infrastructure.

Risk assessment in government organizations involves identifying and assessing potential threats and vulnerabilities, conducting regular audits, and complying with relevant regulations and standards.

Best practices for cybersecurity in government organizations include implementing secure communication protocols, regularly updating and patching software, and conducting regular cybersecurity training and awareness programs for employees.

Cybersecurity ethics refers to the ethical considerations involved in cybersecurity, such as privacy, data protection, and the responsible use of technology.

Cybersecurity ethics are crucial for maintaining trust in technology, protecting privacy and data, and promoting responsible behavior in the digital world.

Examples of cybersecurity ethics include protecting the privacy of user data, ensuring data accuracy and integrity, and implementing fair and unbiased algorithms.

The future of cybersecurity will involve a shift towards more advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and quantum computing.

Emerging cybersecurity threats include AI-powered cyber attacks, the use of deepfakes and synthetic media, and the potential for quantum computing to break current encryption methods.

Advancements in cybersecurity technology include the development of AI and machine learning-based security tools, the use of blockchain for secure data storage and sharing, and the development of post-quantum encryption methods.

This paper has provided an overview of cybersecurity, cyber threats, cybersecurity measures, cybersecurity in the business and government sectors, cybersecurity ethics, and the future of cybersecurity.

To enhance cybersecurity, organizations should prioritize risk assessment and implement a comprehensive cybersecurity strategy that includes prevention, detection, and response measures. Additionally, organizations should prioritize cybersecurity ethics to promote responsible behavior in the digital world.

C. Conclusion

Cybersecurity is an essential aspect of modern society, and organizations must prioritize cybersecurity to protect sensitive data and maintain trust in technology.

for further reading

X. Appendices

A. Glossary of key terms

B. Cybersecurity checklist for organizations

C. Sample cybersecurity policy for businesses

D. Sample cybersecurity incident response plan

E. Cybersecurity training and awareness resources

Note : The content and organization of the paper may vary depending on the specific requirements of the assignment or target audience. This outline serves as a general guide for writing a research paper on cybersecurity. Do not use this in your assingmets.

Research Paper Outline Template

- Background information and context of the research topic

- Research problem and questions

- Purpose and objectives of the research

- Scope and limitations

II. Literature Review

- Overview of existing research on the topic

- Key concepts and theories related to the research problem

- Identification of gaps in the literature

- Summary of relevant studies and their findings

III. Methodology

- Research design and approach

- Data collection methods and procedures

- Data analysis techniques

- Validity and reliability considerations

- Ethical considerations

IV. Results

- Presentation of research findings

- Analysis and interpretation of data

- Explanation of significant results

- Discussion of unexpected results

V. Discussion

- Comparison of research findings with existing literature

- Implications of results for theory and practice

- Limitations and future directions for research

- Conclusion and recommendations

VI. Conclusion

- Summary of research problem, purpose, and objectives

- Discussion of significant findings

- Contribution to the field of study

- Implications for practice

- Suggestions for future research

VII. References

- List of sources cited in the research paper using appropriate citation style.

Note : This is just an template, and depending on the requirements of your assignment or the specific research topic, you may need to modify or adjust the sections or headings accordingly.

Research Paper Outline Writing Guide

Here’s a guide to help you create an effective research paper outline:

- Choose a topic : Select a topic that is interesting, relevant, and meaningful to you.

- Conduct research: Gather information on the topic from a variety of sources, such as books, articles, journals, and websites.

- Organize your ideas: Organize your ideas and information into logical groups and subgroups. This will help you to create a clear and concise outline.

- Create an outline: Begin your outline with an introduction that includes your thesis statement. Then, organize your ideas into main points and subpoints. Each main point should be supported by evidence and examples.

- Introduction: The introduction of your research paper should include the thesis statement, background information, and the purpose of the research paper.

- Body : The body of your research paper should include the main points and subpoints. Each point should be supported by evidence and examples.

- Conclusion : The conclusion of your research paper should summarize the main points and restate the thesis statement.

- Reference List: Include a reference list at the end of your research paper. Make sure to properly cite all sources used in the paper.

- Proofreading : Proofread your research paper to ensure that it is free of errors and grammatical mistakes.

- Finalizing : Finalize your research paper by reviewing the outline and making any necessary changes.

When to Write Research Paper Outline

It’s a good idea to write a research paper outline before you begin drafting your paper. The outline will help you organize your thoughts and ideas, and it can serve as a roadmap for your writing process.

Here are a few situations when you might want to consider writing an outline:

- When you’re starting a new research project: If you’re beginning a new research project, an outline can help you get organized from the very beginning. You can use your outline to brainstorm ideas, map out your research goals, and identify potential sources of information.

- When you’re struggling to organize your thoughts: If you find yourself struggling to organize your thoughts or make sense of your research, an outline can be a helpful tool. It can help you see the big picture of your project and break it down into manageable parts.

- When you’re working with a tight deadline : If you have a deadline for your research paper, an outline can help you stay on track and ensure that you cover all the necessary points. By mapping out your paper in advance, you can work more efficiently and avoid getting stuck or overwhelmed.

Purpose of Research Paper Outline

The purpose of a research paper outline is to provide a structured and organized plan for the writer to follow while conducting research and writing the paper. An outline is essentially a roadmap that guides the writer through the entire research process, from the initial research and analysis of the topic to the final writing and editing of the paper.

A well-constructed outline can help the writer to:

- Organize their thoughts and ideas on the topic, and ensure that all relevant information is included.

- Identify any gaps in their research or argument, and address them before starting to write the paper.

- Ensure that the paper follows a logical and coherent structure, with clear transitions between different sections.

- Save time and effort by providing a clear plan for the writer to follow, rather than starting from scratch and having to revise the paper multiple times.

Advantages of Research Paper Outline

Some of the key advantages of a research paper outline include:

- Helps to organize thoughts and ideas : An outline helps to organize all the different ideas and information that you want to include in your paper. By creating an outline, you can ensure that all the points you want to make are covered and in a logical order.

- Saves time and effort : An outline saves time and effort because it helps you to focus on the key points of your paper. It also helps you to identify any gaps or areas where more research may be needed.

- Makes the writing process easier : With an outline, you have a clear roadmap of what you want to write, and this makes the writing process much easier. You can simply follow your outline and fill in the details as you go.

- Improves the quality of your paper : By having a clear outline, you can ensure that all the important points are covered and in a logical order. This makes your paper more coherent and easier to read, which ultimately improves its overall quality.

- Facilitates collaboration: If you are working on a research paper with others, an outline can help to facilitate collaboration. By sharing your outline, you can ensure that everyone is on the same page and working towards the same goals.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

APA Research Paper Format – Example, Sample and...

Research Contribution – Thesis Guide

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

Chapter Summary & Overview – Writing Guide...

Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and...

Informed Consent in Research – Types, Templates...

Still have questions? Leave a comment

Add Comment

Checklist: Dissertation Proposal

Enter your email id to get the downloadable right in your inbox!

Examples: Edited Papers

Need editing and proofreading services, research paper outline: templates & examples.

- Tags: Academic Research , Academic Writing , Research , Research Paper

Writing research papers is an extensive, time-consuming, and complicated task. Forming a research paper outline does, however, simplify this process. It helps organize your thoughts, create a logical flow, and give structure to otherwise haphazardly arranged information.

As your academic editors and proofreaders , we have provided you with all the necessary resources such as an outline for a research paper template, plenty of research paper outline examples, and tips and tricks to construct your research paper outline. Our goal is to help you write a well-structured, clear, and succinct research paper outline.

Ensure flawless formatting for your research paper. Get started

What is a paper outline?