How Does Society Treat the Disabled People | Essay on Disability

Disability essay: introduction, disability in modern society, how does society treat the disabled person, disability essay: conclusion, works cited.

Disability is a mental or physical condition that restricts a person’s activities, senses or movements. Modern societies have recognized the problems faced by these individuals and passed laws that ease their interactions.

Some people, therefore, believe that life for the disabled has become quite bearable. These changes are not sufficient to eliminate the hurdles associated with their conditions.

The life of a person with a disability today is just as difficult as it was in the past because of the stigma in social relations as well as economic, mobility and motivational issues associated with such a condition.

A person with a disability would live a hard life today owing to the emotional issues associated with the condition. His or her identity would revolve around his or her disability rather than anything else that the person can do.

It does not matter whether the individuals is handsome or talented, like Tom Cruise. At the end of the day, he will always be a disabled man. This attitude obscures one’s accomplishments and may even discourage some people from accomplishing anything.

Other able-bodied individuals would always categorize such a person as a second-class citizen. It would take a lot of will power and resolve to get past these labels and merely lives one’s life. Opponents of this argument would claim that some great inventors of modern society are disabled.

A case in point was Dr. Stephen Hawkings, whose mathematical inventions led to several breakthroughs in the field of cosmology (Larsen 87). While such accomplishments exist, they do not represent the majority.

Persons like Hawkings have to work harder because they have their handicaps to cope with alongside their other scientific work. A disabled scientist is more diligent than a normal one because he has two forms of hurdles to tackle.

It is not common to find such immense willpower in the general population. Therefore, disability leads to a tough life owing to its emotional demands on its subjects.

How the Society Can Be Helpful to the Disabled People

Modern life has created several technologies designed to simplify movement. For instance, modern cities have stairs, trains, cars, doors and elevators to achieve this. However, these technologies are not easy to use for disabled people.

Many of them find that they cannot climb stairs, drive cars or even access trains without help from someone else. Therefore, while the rest of the world is enjoying the benefits of technology, a disabled person would still have to overcome these challenges in order to move from place to place.

Some opponents of this assertion would claim that the life of a disabled person today is unproblematic because a lot of devices have been developed to facilitate movement and other interactions. For instance, a person with amputated legs can buy artificial limbs or use a wheelchair.

However, some of the best assistive technologies for the disabled are quite expensive, and average citizens cannot afford them.

Many of them would have to contend with difficult -to-use devices like wheelchairs, which may not always fit into certain spaces. They would also have to exert themselves in order to use those regular devices.

Social relations are a serious challenge for disabled people today. A number of them live isolated lives or only interact with persons who have the same condition. Social stigma is still rife today even though progress has been made.

Friends would simply be unwilling to dedicate much of their free time to help this disabled person move. Additionally, finding a life partner or marrying someone would also be a laborious process because of the physical and psychological implications.

If one’s handicap is physical, and affects their kinetics, then they would not engage in sexual activity.

Alternatively, psychical deformities may be off putting as many individuals find them sexually unattractive. These social stigmas can impede a disabled person’s ability to enjoy normal relationships with others.

Economic hurdles are also another cause of unfulfilled lives amongst the disabled. Some jobs do not require an investment in one’s image, so these would be tenable for the disabled. However, a number of positions take into account one’s physical image.

These include television anchoring, sports, politics, and even sales jobs. The practical demands of these jobs, such as sales and sports, would not allow a disabled person to engage in them meaningfully.

Alternatively, the positions may also place too much emphasis on physical appearance to the point of making disabled persons unsuitable for them. While the latter might seem like discrimination, it is a given fact that the world is increasingly becoming superficial.

Companies only want to focus on what sells, so they have little time to be proactive or fair. In essence, these attitudes close the door t many opportunities for the disabled as they pigeonhole them into passive professions.

Modern societies have not eradicated the obstacles that persons with disabilities face. This is evident in their attitudinal inclinations as most of them reduce a disabled person’s identity to their inability rather than their accomplishments.

Difficulties in mobility and use of technology among the disabled also testify to their hardships. Social stigma concerning their physical attractiveness and demands in friendships also limit their social relationships.

Finally, their economic prospects are neutralized by their mobility challenges as well as their physical image. All these hurdles indicate that disability causes its victims to live painstaking lives.

Larsen, Kristine. Stephen Hawking: A biography . Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing, 2007. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 29). How Does Society Treat the Disabled People | Essay on Disability. https://ivypanda.com/essays/disability-in-modern-society/

"How Does Society Treat the Disabled People | Essay on Disability." IvyPanda , 29 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/disability-in-modern-society/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'How Does Society Treat the Disabled People | Essay on Disability'. 29 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "How Does Society Treat the Disabled People | Essay on Disability." October 29, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/disability-in-modern-society/.

1. IvyPanda . "How Does Society Treat the Disabled People | Essay on Disability." October 29, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/disability-in-modern-society/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "How Does Society Treat the Disabled People | Essay on Disability." October 29, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/disability-in-modern-society/.

- The Effects of Ergonomic Wheelchairs on Permanently Chair Bound People

- Michelangelo’s Madonna of the Stairs

- Smart Wheelchair Product Market Strategy

- AHP Company in the Automated Wheelchair Market

- Business Plan of the Art Wheelchairs Company

- Anaerobic Test: Sprint Stairs and Vertical Jump Field Method

- Accessible Design: Disability (Wheelchair)

- The Hurdles in the Lawmaking Process

- Communication and People With Disabilities

- Current Hurdles in Combating Terrorism

- Journal for Behavioral Intervention Project

- The Change of my Smoking Behavior

- Estimating the Healthy People 2020 Initiative

- Understanding How the Medical and Social Model of Disability Supports People With Disability

- Managing Occupational Health and Safety: A Multidisciplinary Approach

- Menopause & Aging Well

- Prevention & Screenings

- Sexual Health

- Pregnancy & Postpartum

- Health by Age

- Self-Care & Mental Health

- Nutrition & Movement

- Family & Caregiving

- Health Policy

- Access & Affordability

- Medication Safety

- Science & Technology

- Expert Perspectives

healthy women

Katie M. Golden

Katie M. Golden is a professional patient and advocate for people living with migraine.

Learn about our editorial policies

What’s a Typical Day Like When You Have a Disability?

Out of everything that was asked of me, i found answering this question to be the most important. “describe what you do in a typical day.” but our days aren’t typical, are they here was my reply. .

Katie Golden is a #teamHealthyWomen Contributor and this post is part of HealthyWomen's Real Women, Real Stories series.

Receiving mail from the Social Security Disability office is always a little frightening. Recently, an envelope showed up in my mailbox—it was time to recertify my disability .

It has been three years since I was awarded benefits. The Social Security Administration has the following guidelines on when and how often someone would be asked to recertify their condition:

If medical improvement is:

- “Expected,” your case will normally be reviewed within six to 18 months after your benefits start.

- “Possible,” your case will normally be reviewed no sooner than three years.

- “Not expected,” your case will normally be reviewed no sooner than seven years.

I fit into the “Possible” category. I rely on these benefits and can’t afford to miss anything in this process. I spend countless hours gathering up all the information I need so there would be no doubt that my chronic migraine disease was still stopping me from being able to have a “regular” job or lead a “regular” life.

On this particular form, out of everything that was asked of me, I found answering this question to be the most important: “Describe what you do in a typical day.”

But our days aren’t typical at all. Here was my reply.

Describe what you do in a typical day.

I do not have “typical days” anymore. I have low, medium, or high pain days. I have functioning, semi-functioning or debilitating days. With chronic migraine disease, I am never able to fully escape the pain as it is an everyday occurrence. My day depends on how intense the pain is and for how long.

I will illustrate how my days vary widely and without any warning. I make adjustments to my schedule throughout the day depending on the intensity of the symptoms, which I experience daily on varying levels. These symptoms include head pain, aphasia, allodynia, fatigue, phonophobia, photophobia, impaired cognitive dysfunction, nausea, akathisia and visual aura.

Low Pain/ Functioning Days

When I wake up at around 9 or 10 am with a pain level of 3-4, I know that this is the best I am going to feel all day. I am most productive for about an hour after waking up. I eat breakfast—usually yogurt and fruit. I take a handful of medication—both prescribed and over-the-counter—just to maintain a pain level that is tolerable.

I respond to emails and check the daily news. I may take some time to write, a practice that has become helpful to me in dealing with my illness. I also take this time to make doctor’s appointments and deal with insurance issues, which is a never-ending battle. Even on good days, if I do any housework I usually only focus on one area of my one-bedroom apartment, as this can be exhausting. During the day, my pain level spikes around 6-8, which forces me to take a nap for an hour or two mid-day. When I wake up, the pain has decreased slightly to about a 5.

I try to get in some form of exercise every day after napping. That may be taking a 30-minute walk, going to a yoga class or going on a bike ride. After one of these activities, I usually shower for the day. On a good day, I am able to run some errands, which I usually break up throughout the week in order to not increase my pain. The grocery store and laundry are two tasks that generally wear me out. While eating healthy is part of my life, making dinner can be challenging. I spend little time making dinner and my partner often helps in making meals and with clean-up.

I spend the evening watching TV, however, my pain increases and I become fidgety. With newly diagnosed Restless Leg Syndrome and Periodic Limb Movement Disorder, I find it very hard to sit still. Even with medications to manage the full-body, uncontrollable twitching and jerking movements, nighttime is very hard for me. The head pain generally spikes as well back up to a 7 or 8, making falling asleep difficult. I take another handful of medication to prevent worsening migraine attacks and to control the symptoms for the next day.

This is me on a low-pain / functioning day:

High Pain and Debilitating Days

I try to stick to a normal sleep schedule so that I wake up between 9 and 10 am. I eat breakfast depending on how nauseated I am. On these days, leaving the house, driving and exercise are out of the question. It is rare that my symptoms improve throughout the day—they typically get worse even when using rescue medication. Some of the medications I take to cut down the pain and inflammation on high pain/debilitating days cause side effects that make me drowsy. That, coupled with the excruciating pain, cause me to spend the majority of the day in bed. I spend little time on the internet or watching TV.

I use sleep as a coping mechanism. Even while sleeping, my body is tensed up to battle the pain. I curl into a ball to protect myself and often find fingernail marks in my palms because I’ve been clenching my fists while asleep. I also grind my teeth and need to wear a mouth guard.

During long stretches of time with high levels of pain, my sleep cycle is interrupted, my food intake is altered, showering is a chore and my body feels like it has been beaten up. I can be in this state for days, weeks or even months at a time. I rarely see friends or spend time outside when this happens. It can take weeks to build my strength back up.

I spend 80% of my time in my apartment. The 20% that I try to venture out has to be carefully planned out. Will there be any noise, lighting, food or other triggers that will make the migraine attacks worse?

I have to take medication before I leave and have all medications with me for any possible scenario when I leave the house. I need an exit strategy. Will I be able to lie down if the pain is suddenly unbearable? Do I have a way home if I feel I can’t drive? Will my impaired cognitive dysfunction cause me to become disoriented, forgetful, or lost?

I always carry a notebook with me because I can easily forget my tasks or what people tell me. I build in extra time because any task now takes me twice as long to complete. I have a small radius (about 5 miles) around my house where I am comfortable going by myself. Anywhere outside of my comfort zone, I prefer to have someone with me no matter what my pain level is that day.

These questions and considerations dictate my “typical day.”

A version of this post originally appeared at GoldenGraine.com .

Alopecia Areata: Losing Your Hair? Don’t Despair

What is alopecia it’s no laughing matter for millions of black american women, can you hear me and other people with disabilities, beyond the physical: how psoriatic arthritis can affect your mental and sexual health, más allá de lo físico: cómo la artritis psoriásica puede afectar tu salud mental y sexual, clinically speaking: questions to ask your hcp about psoriatic arthritis.

- Sharp Pain in Left Breast

- Signs of a Stroke

- Top 10 Sex Tips

- Covid Vaccine and Menstrual Cycle

- Pelvic Pain

- Sex and Vaginal Pain

- Perimenopause Weight Gain

- How to Last Longer in Bed

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

What is life really like for disabled people? The Disability Diaries reveal all

We asked seven people to keep diaries for a month to document the reality of being disabled in Britain today. Frances Ryan reflects on the issues that arose – public transport, employment, housing, attitudes – and meets four of the diarists

Seven things you should stop saying and doing to disabled people

O n her way from St Albans to Nottingham, Shona Cobb nearly found herself stuck on a train on three separate occasions. Cobb had booked wheelchair ramp assistance for each required change – but not one staff member turned up to help her. Instead, at one stop, she had to rely on a friendly couple to help her; at another, the only way to prevent the train door closing with her still on board was to stick her foot in it.

It is a neat and infuriating irony that Cobb struggled to get to an interview about the discrimination facing disabled people because she was experiencing just this kind of “disabilism”.

The Guardian asked seven people to document their everyday experiences of disability throughout September – including Cobb, 19, who has the connective tissue disorder Marfan syndrome. Their diaries capture the reality of being disabled in Britain today: the slights, broken systems and misunderstandings that stop disabled people from living as should be their right.

Hassles with public transport are a common theme – such as the extra half-hour Nina Grant has to set aside to reach any destination, as she navigates the London tube network. “I’m lucky I live just one bus ride away from an accessible tube station,” writes Grant, 31, who has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, another connective tissue disorder, and uses a power wheelchair.

Then there are the inquiries Sasha Saben Callaghan, who is visually impaired and has limited mobility, has to put up with from random strangers. When they ask: “How did that happen?”, she sometimes just makes something up. “Once I said: ‘I angered a magician.’ They weren’t expecting that.”

Pete Langman, 50, writes about the difficulties that come with negotiating the world when you have early onset Parkinson’s, which causes hand tremors and mobility problems – from bouncers at clubs asking if he’s drunk, to odd responses when internet dating. In a conversation with one potential date, who commented on the brevity of his texts, Langman explained: “I have Parkinson’s so phone texting is tough.” “U r joking right?” came the reply.

There’s the trickiness of negotiating the workplace. Luke Judge writes about a client who asks why he is clocking off at 4.30pm, the finishing time agreed by his doctor and employer. “He asked why I was leaving early. Cheeky! What could I say? I am epileptic and it’s a medical reason? A bit of an awkward conversation. I have had this with some colleagues, too, who jokingly call me a ‘part-timer’, which I laugh off. But most of them don’t know I’m epileptic, so I usually just say I have an appointment.”

The first day of a new job can be nerve-racking for anyone. “There’s always risk when moving jobs, but when you are disabled there’s another layer of risk: will I be subject to abuse or bullying because of my disability?” writes Sam Fowkes, who has cerebral palsy and has just been promoted as an NHS manager. “Will I be seen as inferior or troublesome because I’ll need adjustments? Will I even be considered fairly at the application stage if I disclose a disability?”

Over the course of the month, Craig Gilding’s insurance company calls him multiple times, “despite it being on their records that I am deaf. Luckily, I managed to answer and sort it. Another deaf friend has lost her no-claims bonus on her car insurance due to communication problems with insurers.” Gilding adds that he recently tried to change his address with the Department for Work and Pensions, but “they insisted I needed to call them (impossible) or post a letter” – which promptly got lost.

I meet with Cobb, Grant, Langman and Gilding at Nottingham Trent University to talk about their experiences of keeping the diaries. There are regular flashes of humour (while discussing the shocked stares of strangers who don’t expect wheelchair users ever to stand, Cobb and Grant exclaim sarcastically: “It’s a miracle!”) and shared frustrations: from similar battles with the social security system to discovering each had encountered prospective employers who, upon seeing their disability, turned them down for a job.

All four agree that the process of keeping a diary led to a spark of recognition: for the first time in their lives, they were consciously noting the inequality they regularly face. “Doing this made me realise how bad things are,” says Cobb. “It’s like everyday, normal: ‘I can’t get in there.’”

The picture the diaries paint reflect a well-documented landscape of prejudice and discrimination: this year, a major study by the Equality and Human Rights Commission found disabled people in the UK are “left behind in society”, with a lack of equal opportunities in education and employment, and barriers to access to transport, health services and housing. This came at the same time as a UN report that condemned the UK government for failing to uphold disabled people’s rights across a range of areas, including education and work.

One of the defining issues that runs through the disability diaries is access. Grant writes about shops she can’t get into because of large steps or raised doorframes, as well as battles with transport and even fellow passengers. When a mother with a buggy moved off the bus to leave room for Grant’s wheelchair (saying she was “the next stop anyway”), she found herself “facing an accusing set of faces who had just seen what looked like a young person with their own motorised vehicle force a mother and her child off the bus”. She adds: “It’s hard to describe the feeling of being scrutinised by multiple strangers at once.”

The diaries show how this carelessness (or outright hostility) from members of the public can combine with inaccessible infrastructure to make even simple tasks a headache: from luggage being piled up around a wheelchair on a train, to cramped shops with non-disabled shoppers not looking where they’re going. During one trip to the shops on a busy Saturday, Cobb writes that she got “hit in the shoulders by a lot of handbags”.

The difficulty of access can even mean missing out on a social life. “Every social invitation tends to require calling or emailing the venue to find out about accessibility,” Grant writes, “and then usually having to explain to the host why I can’t come.”

The last major government audit in 2014 (the largest ever of its kind) described access for disabled people on Britain’s high streets as “shocking”. Surveying more than 30,000 shops and restaurants, it found a fifth of shops have no wheelchair access, only 15% of restaurants and shops have hearing loops and three-quarters of restaurants don’t cater for people with visual impairments.

Commenting on a shopping trip in London, Cobb writes: “In River Island, I was shocked to find they don’t have a disabled changing room – I thought all places had to have them!” And when a new Topshop was built near her house recently, she found it had a flight of stairs but no lift. Cobb tells me she asked an assistant whether they would consider putting one in, but was told it would “inconvenience” other people. “It was: ‘We care more about our able-bodied customers than you.’”

It’s often the same with transport: bus drivers routinely refuse to let wheelchair users on board, despite their legal obligation to do so , while only about a quarter of London’s underground stations are accessible for wheelchairs. Grant routinely has to use a neighbouring tube station because her nearest one isn’t accessible – forcing her to take a 15-minute bus ride to the tube before “going back on herself”.

In one diary entry, Cobb chronicles a train journey from Leeds to Hull. It is the first time she has ever taken the train at night by herself: “My assistance didn’t turn up so everyone rushed on the train and filled the wheelchair spaces while I hunted down the guard for the train,” she writes. No one would move for her, so she ended up squeezing into a corner near the toilet for an hour: “It wasn’t exactly a safe way for me to travel, but I had no choice.”

For Fowkes, overcrowding on our rail networks presents him with a painful predicament on his daily commute in the West Midlands. Because his cerebral palsy is largely “invisible” (“unless you were looking, you wouldn’t know I was disabled”), he worries about asking commuters for a seat. “I’d have to try to explain my disability in front of a lot of people on the train, which would be massively uncomfortable – even forgetting the times I’ve been verbally and physically abused in the past,” he writes.

Fowkes’s disability can leave him with insomnia due to the pain. After one particularly bad night’s sleep, and another commute with no seat to work or back, he notes that by the end of the day “it feels like my left leg has been hit with a sledgehammer”. Wider adoption of badges like Transport for London’s Please Offer Me a Seat would help, he says.

Travelling around the country is little better for people with non-mobility-related disabilities. Gilding uses public transport frequently, but describes it as “a nightmare” for those like him with hearing problems. “If you have to speak to someone on train stations, say, you have these big help buttons – ring if you need assistance … I can’t hear a thing.”

Throughout his diary, Gilding, like Fowkes, notes how simple adaptations would make his commute accessible: “I’ve asked time and time again for departure boards, to no avail,” he writes.

The failure to address these problems speaks to a persistent, deeply embedded cultural attitude around disability: that disabled people aren’t quite like “normal people”. The belief that a wheelchair user doesn’t want a social life, say, makes it easier not to worry about ensuring transport networks are accessible. As Grant writes after yet another frustrating day, the most basic needs of disabled people are neglected “in a manner that wouldn’t happen if they were needed by everyone”.

In the same way, disabled people still routinely encounter negative reactions from other members of the public – ranging from being patronised to outright hostility – simply for going out.

Langman, from Brighton, says he frequently faces derogatory comments about the way he walks because of his Parkinson’s, and writes of “the stares, the laughter after I pass” from strangers. Some even imitate his walk.

But as much as the abuse, it’s the benevolent prejudice – well-meaning but ultimately damaging – that affects him. Langman plays cricket for a local team and says opponents often don’t know how to respond to his condition, either overcompensating or suggesting a positive outlook would help. “Someone asked me what the prognosis of Parkinson’s was. I said: ‘It’s progressive.’ He said: ‘Well, it will be if that’s your attitude.’ I nearly punched him.”

Cobb, who posts videos online filmed from her wheelchair , points out that this intrusive outlook means disabled people often encounter a strange phenomenon on the street: members of the public routinely asking, “Why are you like that?”, as if they feel disabled people “owe” them an explanation about their medical background.

At best, this can lead to a bizarre crossing of boundaries, akin to asking a complete stranger about their sexual history (Gilding says he can be in the supermarket, and a fellow shopper will point to his cochlear implant and ask him: “What’s that on your head?”). At its worst, it can create the uneasy feeling that those around you are monitoring your disability and behaviour, waiting for you to slip up.

For the first year Cobb had her powerchair, she was afraid to move her legs in case people saw it as a sign she was “faking”. At a time when media depictions of disabled people are predominantly negative and reports of disability hate crime are increasing , Cobb says she repeatedly noticed strangers staring at her legs: “In the end, I wouldn’t even cross my legs.” This fear affected her to such a degree that, for years, she didn’t apply for disability benefits because she internalised the idea that she wasn’t “disabled enough” to “deserve it”.

Both Grant and Langman have lost their disability benefits in the past three years (Grant got hers back on appeal), while Cobb – who has a cyst at the bottom of her spine that means she needs a reclining wheelchair to relieve the pain – tells me she has been turned down twice by NHS wheelchair services. Like an increasing number of disabled people, she has had to start crowdfunding to raise the £11,500 she needs for her new chair. “I’m halfway there,” she says.

In the meantime, without a suitable wheelchair and with limited pain medication, Cobb is living with a “two-hour limit” for being out the house: after a couple of hours being interviewed, she has to go back to her hotel to lie down.

The UK’s lack of accessible housing is another key problem. Cobb lives with her parents in a two-storey house, and can only access her own bedroom by “going up and down the stairs on my bum”. Similarly, Grant is living in inaccessible housing with her family in London, and for the past year has been searching fruitlessly for an accessible property: “Private landlords don’t want you making adaptations [that I need to live independently], and the council doesn’t have accessible housing stock,” she says. “I have literally no idea where I’m going to go.”

As we talk, Grant reveals that she did not mention the house search in her diary, because she is so disheartened that even looking on the Rightmove website is making her anxious.

The introduction of equality legislation over the past 20 years (giving disabled people the right to access work, transport and public venues ), coupled with high-profile events such as London’s 2012 Paralympics, may have created the impression that Britain is moving forwards in its treatment of disabled people, but day-to-day life is still riddled with barriers.

Grant sums it up: “I think we like to think [as a country] we’re making progress. But in reality, we still get turned away from buses. We still have nowhere to live.”

Some of the solutions to this inequality require large-scale change, often involving government policy – from requiring a certain proportion of new-build houses to be wheelchair accessible, to stricter enforcement of equality legislation on pubs and shops that aren’t meeting their legal access requirements.

But what the diaries underline is that seemingly minor measures can be just as important: shop owners ensuring access buttons for automatic doors are actually working, for example; more dropped kerbs on pavements; shop staff ensuring non-disabled people aren’t using the accessible changing room.

As well as practical changes, a further cultural shift is required: both Grant and Gilding say having greater visibility of disabled people in the media and politics would go some way to normalising disability in society. All the diarists stress one thing above all else: that the able-bodied public needs to understand that disabled people still face inequality in Britain every day.

As Langman tweets to the rest of the diarists on his way home from the interview: “If one thing improves as a result of this, we’re winning.”

- If you have experiences relating to this article that you’d like to share, please email us at inequality.project@ theguardian.com

- Follow the Inequality Project on Twitter here

- The disability diaries

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Disability and Health Stories from People Living with a Disability

- Nickole's Story

- Jerry's Story

- Justin's Story

- Suhana's Story

Real Stories from People living with a Disability

Nickole cheron’s story.

In 2008, a rare winter storm buried Portland, Oregon under more than a foot of snow. The city was gridlocked. Nickole Cheron was stuck in her home for eight days. Many people would consider that an inconvenience. For Nickole, whose muscles are too weak to support her body, those eight days were potentially life-threatening.

Born with spinal muscular atrophy, a genetic disease that progressively weakens the body’s muscles, Nickole is fully reliant on a wheelchair and full-time caregivers for most routine tasks. Being alone for eight days was not an option. So Nickole signed up for “ Ready Now! pdf icon [PDF – 4.8MB] external icon ,” an emergency preparedness training program developed through the Oregon Office of Disability and Health external icon .

“The most important thing I learned from ‘Ready Now!’ was to have a back-up plan in case of an emergency situation ,” she said. “When I heard the snow storm was coming, I emailed all my caregivers to find out who lived close by and would be available. I made sure I had a generator, batteries for my wheelchair, and at least a week’s supply of food, water and prescription medication.”

Nickole said the training was empowering, and reinforced her ability to live independently with a disability. She felt better informed about the potential risks people with disabilities could encounter during a disaster. For example, clinics might close, streets and sidewalks might be impassable, or caregivers might be unable to travel.

Among the tips Nickole learned from Oregon’s “Ready Now!” training are:

- Develop a back-up plan. Inform caregivers, friends, family, neighbors or others who might be able to help during an emergency.

- Stock up on food, water, and any necessary prescription medications, medical supplies or equipment. Have enough to last at least a week.

- Make a list of emergency contact information and keep it handy.

- Keep a charged car battery at home. It can power electric wheelchairs and other motorized medical equipment if there is an electricity outage.

- Learn about alternate transportation and routes.

- Understand the responsibilities and limitations of a “first responder” (for example, members of your local fire department of law enforcement office) during a disaster.

“This training shows people with disabilities that they can do more to triage their situation in a crisis than anyone else can,” she said. “‘Ready Now!’ encourages people with disabilities to take ownership of their own care.”

CDC would like to thank Nikole and the Oregon Office of Disability and Health external icon for sharing this personal story.

Learn about emergency preparedness for people with disabilities »

Jerry’s Story

Jerry is a 53 year old father of four children. He’s independent, has a house, raised a family and his adult kids still look to him for support. Jerry recently retired as a computer programmer in 2009, and competes and coaches in several sports. This “healthy, everyday Joe, living a normal life” has even participated in the Boston Marathon. Jerry also has had a disability for over 35 y ears. In 1976 on December 3 (the same day that International Persons with Disabilities Day is recognized) Jerry was hit by a drunk driver. The accident left him as a partial paraplegic.

Jerry’s life is not defined by his disability. He lives life just like anyone else without a disability would live their life. “There’s lots I can do, and there are some things that I can’t do,” said Jerry. “I drive, I invest money. I’m not rich, but I’m not poor. I enjoy being healthy, and being independent.”

As a person with a disability, however, Jerry has experienced many barriers. Recovering from recent rotator cuff surgery, his rehabilitation specialists “couldn’t see past his disability”, administering tests and delivering additional rehabilitation visits that a person without a disability wouldn’t receive. He once was being prepared for surgery when a nurse proclaimed “he doesn’t need an epidural, he’s a paraplegic.” Jerry had to inform the nurse that he was only a partial paraplegic and that he would indeed need an epidural.

Jerry was in line at an Alabama court house to renew his parking permit and also renew his son’s registration. He watched a worker walk down the line and ask people “what do you need?” When she got to Jerry and saw his wheelchair, he was asked “who are you here with?” And Jerry finds it difficult to go to concerts and baseball games with a large family or friends gathering, because rarely are handicap-accessible tickets available for more than two people.

Jerry has seen a lot in over 35 years as someone living with a disability. He’s seen many of the barriers and attitudes towards people with disabilities persist. But he’s also seen many positive changes to get people with disabilities physically active through recreational opportunities such as golf, fishing and even snow-skiing. There are now organizations such as Lakeshore Foundation external icon – where Jerry works part-time coaching youth basketball and track – that provide recreational opportunities.

Jerry states: “I don’t expect the world to revolve around us. I will adapt – just make it so I can adapt.”

Justin’s Story

Justin was first diagnosed with a disability in the form of ADD (attention deficit disorder, now known as ADHD, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) at the age of 5 years. The diagnosis resulted in his removal from a regular classroom environment to special education courses. Justin’s parents were informed by Justin’s educators that he probably wouldn’t graduate high school, much less college.

Years later, as a young adult, Justin developed Meniere disease (an inner ear disorder), which affected his hearing and balance. The onset of the disorder left Justin with the scary reality that he could permanently lose his hearing at any time. Justin recalled a former supervisor taking advantage of this knowledge with an inappropriate prank: While speaking in a one-on-one meeting, the sound from the supervisor’s mouth abruptly halted, while his lips continued to move. Justin thought he had gone deaf – until the supervisor started laughing – which Justin could hear. Behaviors like the above took its toll on Justin’s confidence – yet, he knew he could contribute in society.

Spurred in part by adversity, Justin went back to school, earned a business degree, and shortly after, entered the commercial marketing industry. However, despite his education and experience, Justin was still regularly subject to the same stigma. Many of Justin’s work experiences over the course of his career left him feeling ashamed, guilty, offended, and sometimes, even intimidated. Rather than instilling confidence, it left him demoralized – simply because he was differently abled.

In July of 2013, everything changed for Justin. He joined the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention working as a contractor in the Division of Human Development and Disability at the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. Justin’s colleagues put an emphasis on making him feel comfortable and respected as a member of a diverse and productive workforce. They welcomed Justin’s diversity, positively contributing to his overall health.

The mission of the Division of Human Development and Disability is to lead public health in preventing disease and promoting equity in health and development of children and adults with or at risk for disabilities. One in two adults with disabilities does not get enough aerobic physical activity 1 , and for Justin, regular physical activity is important to help him combat potentially lethal blood clots due to a genetic blood clotting disorder that he has. Every working hour, Justin walks for a few minutes, stretches, or uses his desk cycle. Justin also participates in walking meetings, which he believes leads to more creative and productive meetings.

Stories such as Justin’s are reminders that employment and health are connected. CDC is proud to support National Disability Employment Awareness Month every October. The awareness month aims to educate about disability employment issues and celebrate the many and varied contributions of America’s workers with disabilities.

Suhana’s Story

Suhana has a sister, Shahrine, who is older by 18 months. While Shahrine’s mother was pregnant with Suhana, their uncle came to town for a visit. During the visit, their uncle was quick to notice that Shahrine did not seem to be talking at an age appropriate level or respond when called upon. Shahrine would also turn up the volume on the television and radio when others could hear it without difficulty. Shahrine’s parents thought that her speech development and behavior were normal for a toddler, but thanks to the uncle expressing his concerns, the family soon took action. A hearing test found that Shahrine was hard of hearing.

Due to Shahrine’s diagnosis, Suhana received a hearing screening at birth and was found to be hard of hearing, as well. Had it not been for the concerns raised by the children’s uncle, not only would Shahrine’s hearing loss have possibly gone on longer without being detected, but Suhana would most likely not have had a hearing screening at birth.

As a result of their early diagnoses, Suhana and Shahrine’s parents were able to gain the knowledge they needed to make sure both of their children could reach their full potential in life. They had access to early services from a team of physicians, speech therapists, counselors, and teachers.

Suhana credits her parents for her own successes, saying that she couldn’t have made it as far as she has without their support and patience. Today, Suhana is employed at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as an epidemiologist with the agency’s Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) program. All children who are deaf or hard of hearing receive critical services they need as a result of the EHDI program, which funds the development of data systems and provides technical assistance to help improve screening, diagnosis and early intervention for these infants. When children who are deaf or hard of hearing receive services early, they are more likely to reach their full potential and live a healthy, productive adult life.

CDC is proud to support National Disability Employment Awareness Month every October. The goals of the awareness month are to educate the public about disability employment issues and celebrate the many and varied contributions of America’s workers with disabilities.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs. [updated 2014 May 6; cited 2014 October 10] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/disabilities/

If you would like to share your personal story, please contact us at Contact CDC-INFO

- Policy Makers

- CDC Employees and Reasonable Accommodations (RA)

To receive email updates about this topic, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book Reviews

In 2 essay collections, writers with disabilities tell their own stories.

Ilana Masad

Buy Featured Book

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

More than 1 in 5 people living in the U.S. has a disability, making it the largest minority group in the country.

Despite the civil rights law that makes it illegal to discriminate against a person based on disability status — Americans with Disabilities Act passed in 1990 — only 40 percent of disabled adults in what the Brookings Institute calls "prime working age," that is 25-54, are employed. That percentage is almost doubled for non-disabled adults of the same age. But even beyond the workforce — which tends to be the prime category according to which we define useful citizenship in the U.S. — the fact is that people with disabilities (or who are disabled — the language is, for some, interchangeable, while others have strong rhetorical and political preferences), experience a whole host of societal stigmas that range from pity to disbelief to mockery to infantilization to fetishization to forced sterilization and more.

But disabled people have always existed, and in two recent essay anthologies, writers with disabilities prove that it is the reactions, attitudes, and systems of our society which are harmful, far more than anything their own bodies throw at them.

About Us: Essays from the Disability Series of the New York Times, edited by Peter Catapano and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, collects around 60 essays from the column, which began in 2016, and divides them into eight self-explanatory sections: Justice, Belonging, Working, Navigating, Coping, Love, Family, and Joy. The title, which comes from the 1990s disability rights activist slogan "Nothing about us without us," explains the book's purpose: to give those with disabilities the platform and space to write about their own experiences rather than be written about.

While uniformly brief, the essays vary widely in terms of tone and topic. Some pieces examine particular historical horrors in which disability was equated with inhumanity, like the "The Nazis' First Victims Were the Disabled" by Kenny Fries (the title says it all) or "Where All Bodies Are Exquisite" by Riva Lehrer, in which Lehrer, who was born with spina bifida in 1958, "just as surgeons found a way to close the spina bifida lesion," visits the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia. There, she writes:

"I am confronted with a large case full of specimen jars. Each jar contains a late-term fetus, and all of the fetuses have the same disability: Their spinal column failed to fuse all the way around their spinal cord, leaving holes (called lesions) in their spine. [...] I stand in front of these tiny humans and try not to pass out. I have never seen what I looked like on the day I was born."

Later, she adds, "I could easily have ended up as a teaching specimen in a jar. But luck gave me a surgeon."

Other essays express the joys to be found in experiences unfamiliar to non-disabled people, such as the pair of essays by Molly McCully Brown and Susannah Nevison in which the two writers and friends describe the comfort and intimacy between them because of shared — if different — experiences; Brown writes at the end of her piece:

"We're talking about our bodies, and then not about our bodies, about her dog, and my classes, and the zip line we'd like to string between us [... a]nd then we're talking about our bodies again, that sense of being both separate and not separate from the skin we're in. And it hits me all at once that none of this is in translation, none of this is explaining. "

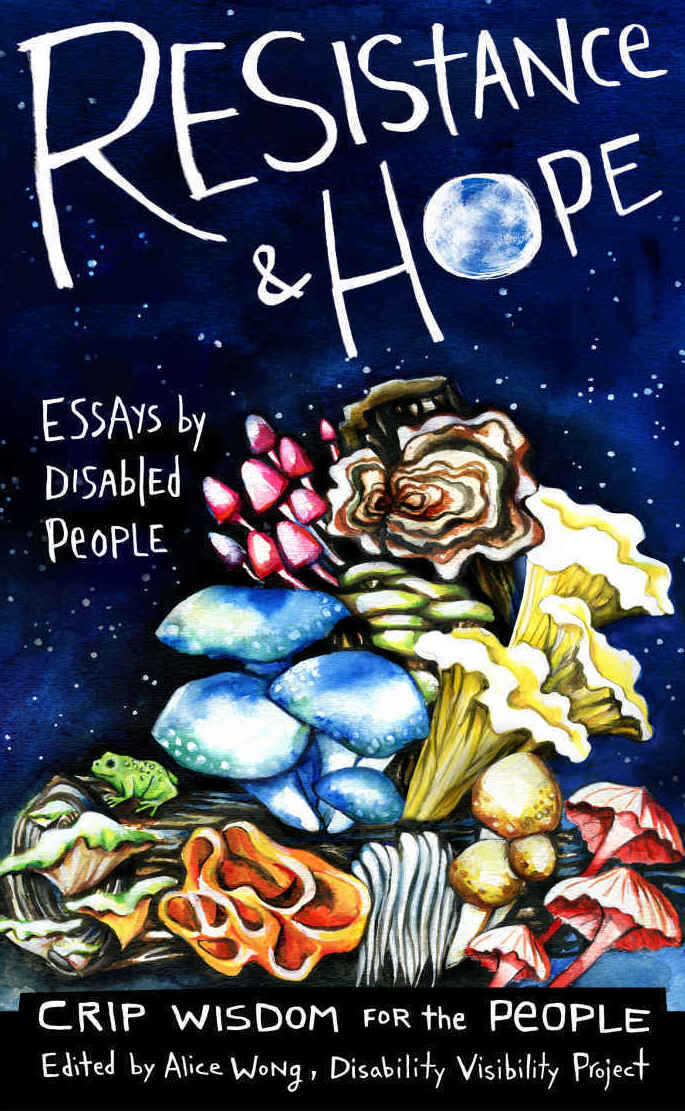

From the cover of Resistance and Hope: Essays by Disabled People, edited by Alice Wong Disability Visibility Project hide caption

From the cover of Resistance and Hope: Essays by Disabled People, edited by Alice Wong

While there's something of value in each of these essays, partially because they don't toe to a single party line but rather explore the nuances of various disabilities, there's an unfortunate dearth of writers with intellectual disabilities in this collection. I also noticed that certain sections focused more on people who've acquired a disability during their lifetime and thus went through a process of mourning, coming to terms with, or overcoming their new conditions. While it's true — and emphasized more than once — that many of us, as we age, will become disabled, the process of normalization must begin far earlier if we're to become a society that doesn't discriminate against or segregate people with disabilities.

One of the contributors to About Us, disability activist and writer Alice Wong, edited and published another anthology just last year, Resistance and Hope: Essays by Disabled People , through the Disability Visibility Project which publishes and supports disability media and is partnered with StoryCorps. The e-book, which is available in various accessible formats, features 17 physically and/or intellectually disabled writers considering the ways in which resistance and hope intersect. And they do — and must, many of these writers argue — intersect, for without a hope for a better future, there would be no point to such resistance. Attorney and disability justice activist Shain M. Neumeir writes:

"Those us who've chosen a life of advocacy and activism aren't hiding from the world in a bubble as the alt-right and many others accuse us of doing. Anything but. Instead, we've chosen to go back into the fires that forged us, again and again, to pull the rest of us out, and to eventually put the fires out altogether."

You don't go back into a burning building unless you hope to find someone inside that is still alive.

The anthology covers a range of topics: There are clear and necessary explainers — like disability justice advocate and organizer Lydia X. Z. Brown's "Rebel — Don't Be Palatable: Resisting Co-optation and Fighting for the World We Want" — about what disability justice means, how we work towards it, and where such movements must resist both the pressures of systemic attacks (such as the threatened cuts to coverage expanded by the Affordable Care Act) and internal gatekeeping and horizontal oppression (such as a community member being silenced due to an unpopular or uninformed opinion). There are essays that involve the work of teaching towards a better future, such as community lawyer Talila A. Lewis's "the birth of resistance: courageous dreams, powerful nobodies & revolutionary madness" which opens with a creative classroom writing prompt: "The year is 2050. There are no prisons. What does justice look like?" And there are, too, personal meditations on what resistance looks like for people who don't always have the mobility or ability to march in the streets or confront their lawmakers in person, as Ojibwe writer Mari Kurisato explains:

"My resistance comes from who I am as a Native and as an LGBTQIA woman. Instinctively, the first step is reaching out and making connections across social media and MMO [massively multiplayer online] games, the only places where my social anxiety lets me interact with people on any meaningful level."

The authors of these essays mostly have a clear activist bent, and are working, lauded, active people; they are gracious, vivid parts of society. Editor Alice Wong demonstrates her own commitments in the diversity of these writers' lived experiences: they are people of color and Native folk, they encompass the LGBTQIA+ spectrum, they come from different class backgrounds, and their disabilities range widely. They are also incredibly hopeful: Their commitment to disability justice comes despite many being multiply marginalized. Artist and poet Noemi Martinez, who is queer, chronically ill, and a first generation American, writes that "Not all communities are behind me and my varied identities, but I defend, fight, and work for the rights of the members of all my communities." It cannot be easy to fight for those who oppress parts of you, and yet this is part of Martinez's commitment.

While people with disabilities have long been subjected to serve as "inspirations" for the non-disabled, this anthology's purpose is not to succumb to this gaze, even though its authors' drive, creativity, and true commitment to justice and reform is apparent. Instead, these essays are meant to spur disabled and non-disabled people alike into action, to remind us that even if we can't see the end result, it is the fight for equality and better conditions for us all that is worth it. As activist and MFA student Aleksei Valentin writes:

"Inspiration doesn't come first. Even hope doesn't come first. Action comes first. As we act, as we speak, as we resist, we find our inspiration, our hope, that which helps us inspire others and keep moving forward, no matter the setbacks and no matter the defeats."

Ilana Masad is an Israeli American fiction writer, critic and founder/host of the podcast The Other Stories . Her debut novel, All My Mother's Lovers, is forthcoming from Dutton in 2020.

The Joy of a Disabled Life

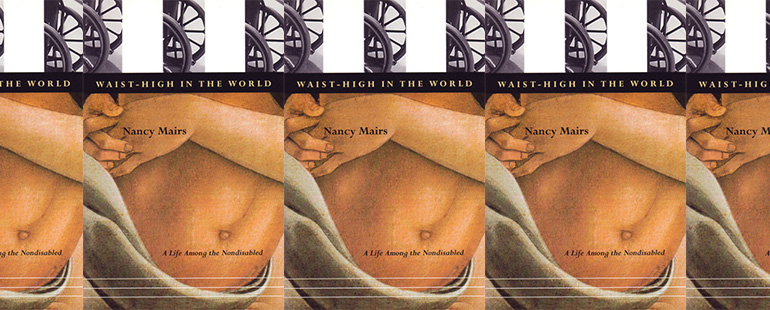

If, on the day of its publication, an author was told their book would still be relevant, perhaps even more so, in 30 years, they would likely be thrilled. I imagine Nancy Mairs, however, would let out a long, knowing sigh, one that says she’s not surprised, but she’s still disappointed.

Diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) in the 1960s, by the time Mairs published her essay collection Waist-High in the World: A Life Among the Nondisabled in 1996, the white matter of her brain had been “shot to hell,” and she primarily used a mobility aid—a Quickie P100 electric wheelchair—to move through the world. Throughout the book, Mairs has a clear, singular intention: to demonstrate to “readers . . . who need, for a tangle of reasons, to be told that a life commonly held to be insufferable can be full and funny. I’m living the life. I can tell them.” Such a concept was, and unfortunately still very much is, a radical one.

I count myself among those readers who needed Mairs’s voice. When I was first diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, I collapsed under a heavy wave of dread—an overwhelming sense that my life would be more complicated and thereby less joyful because of my disability. I know, however, that I’m not the only reader whom Mairs foresaw approaching her work from this perspective. In fact, she appears to have written these essays specifically with readers like me in mind, with the goal of creating a travel guide of sorts for living with a disability, an altruistic attempt to “make the terrain seem less alien, less perilous, and far more amusing than the myths and legends about it would suggest.” A quarter-century later, we are, in some ways, in need of Mairs’s words now more than ever.

In the midst of a global pandemic, what disability advocates are calling , after Imani Barbarin , a “mass disabling event,” there are some who would seek to strip disabled Americans of the few legal protections we have. This past fall, CVS Pharmacy was prepared to go to the Supreme Court to argue that so long as discrimination against the disabled was “unintentional,” it was not in violation of any law. Only after public outcry did CVS dismiss the case and release a joint statement with disability groups, committing to “affordable and equitable access to health care.”

The premise of this case is disturbing. Whether CVS was aware of it or not, the fact of the matter is that most discrimination against the disabled isn’t “intentional.” It is most often the result of thoughtlessness or neglect; but this doesn’t make the discrimination (or, to use legalese, “disparate impact”) any less harmful. In fact, this sort of negligence functions as an effective erasure of the disabled. If accommodations aren’t provided, if our environments aren’t structured in a way that allows for the disabled to fully participate in society, then we are behaving as if disabled people don’t exist. And as Nancy Mairs baldly states, “whatever goes unseen goes unchanged.”

In Waist-High , Mairs dedicates some pages to specifically unpacking the connection between accessibility and erasure, addressing the issue head-on in the essay “Opening Doors, Unlocking Hearts.” Before plunging into the details, such as how private residences aren’t constructed with door frames wide enough for a wheelchair or showers with grab bars, or how public spaces typically only meet these types of requirements under the threat of litigation, Mairs opens the essay with the sharpest of deductions: “The world as it is currently constructed does not especially want—and plainly does not need—me in it . . . I mean simply that much of the time, as a disabled woman, I find that my physical and social environments send the message that my presence is not unequivocally either welcome or vital.” She then goes further, reaching beyond the fact that we live in a world that’s hostile toward disabled people into the heart of the matter: Why is our world built this way in the first place? The answer: Disability is the nondisableds’ worst nightmare, and they assume it must be ours, too.

Nondisabled people’s fear of disability most often takes the form of pity, which manifests in one of two ways: avoidance or feigned adoration. Mairs addresses both of these reactions over and over again throughout the collection. While it’s rather obvious that those who practice, in Mairs’s words, “studied inattention” when interacting with a disabled person are made uncomfortable by the presence of disability, some may ask how the expression of (again, in Mairs’s words) “unmerited admiration” is a display of pity. Mairs breaks this concept down better than I could ever hope to:

‘You’re so brave,’ they gush, generally when I have done nothing more awesome than roll up to the dairy case and select a carton of vanilla yogurt. ‘I could never do what you do!’ Of course they could—and likely would—do exactly what I do, maybe do it better, but the very thought of ever being like me so horrifies them that they can’t permit themselves to put themselves on my wheels even for an instant. Admiration, masking a queasy pity and fear, serves as a distancing mechanism, in other words.

From this deep, Mairs plunges deeper still. How does this fear, whether it’s manifested through avoidance or fawning, work to keep our world inequitable? According to Mairs, “the people who seem most hostile to my presence are those most fearful of my fate. And since their fear keeps them emotionally distant from me, they are the ones least likely to learn that my life isn’t half so dismal as they assume.”

On some level, nondisabled people recognize that they are one car accident or diagnosis away from being just like us–and that terrifies them. They believe that we must be in so much pain and suffering at all times, that it must be so thoroughly awful to inhabit our bodies, that our lives are not worth living. What most nondisabled people have yet to untangle, however, is that the source of much, if not most, of the pain and discomfort disabled people face is the hostile structures of our society: the public health policies, the physically inaccessible spaces, the ableism—not our disabilities themselves. If these issues were remedied, if disabled people were not only welcomed but cherished by our society, for something other than their capacity to “inspire,” there would be no reason to fear becoming disabled.

As Mairs wades through these issues throughout her book, she deploys a sense of humor that keeps the reader laughing, even as they confront such serious topics as eugenics and medical fraud. Some might assume that Mairs employs a dark humor, trying to make us laugh so we don’t cry. In one passage, for example, she writes, “The other day, when my husband opened a closet door, I glimpsed myself in the mirror recently installed there. ‘Eek,’ I squealed, ‘a cripple!’ I was laughing, but as is usually the case, my humor betrayed a deeper, darker reaction.” Immediately afterward, Mairs presents an analysis of how our culture portrays “illness and deformity” as “the consequence of cosmic bad luck” and “deviations from the fully human condition, brought on by personal failing or divine judgment,” resulting in Mairs being “appalled by [her] own appearance.” I’d argue, however, that this excerpt is an exception rather than the rule and, on the whole, Mairs’s commentary and asides are simply intended as humor. In one essay, Mairs discusses traveling while disabled: “Now that I can no longer dress myself,” she writes, “traveling alone to any destination other than a nudist colony is impractical.” In another, Mairs shuns the term “mobility impaired” with a quip: “Certainly I am not mobility impaired; in fact, in my Quickie P100 with two twelve-volt batteries, I can shop till you drop at any mall you designate. I promise.” Perhaps my favorite comedic aside of the whole collection is when Mairs discusses how her sex life has evolved, considering both her MS and her husband’s impotence. She writes, “And since my wheelchair places me at the height of [my husband’s] penis (though Cock-High in the World struck me as too indecorous a book title) I may nuzzle it in return.” Let me tell you: I cackled.

You’ll notice that many of Mairs’s humorous comments point the reader back to her disability, but she is neither making us “laugh so we don’t cry,” nor is she being self-deprecating in an attempt to beat others to the punch. Instead, Mairs calls our attention, over and over again, to the innate humor to be found in disability, which, just like any other aspect of life, has its inherent moments of levity. Through this use of humor, Mairs challenges her nondisabled readers to push past any discomfort or pity they might have once felt and instead acknowledge the fact that a disabled life is very much worth living; it is full of laughter and joy, and not even in spite of one’s disability—often because of it.

Although we won’t know the full extent of long-COVID’s impact for some time, we can almost guarantee that thousands, if not millions, of individuals will newly identify as disabled in the coming years. And although Mairs is writing in 1996, when COVID-19 was only sci-fi fodder, she points out that through advances in medicine and technology, people are living longer, which statistically increases one’s chance of developing an illness or being involved in an accident that will “permanently alter physical capacities.” With an eerily prophetic tone, Mairs concludes that “something without precedent is taking place, and we need a theoretical and imaginative framework for evaluating and managing the repercussions.”

If we don’t restructure our environments and our understanding of disability, accessibility, and equity, we risk making the world worse for ourselves and the people we love, no matter our disability status. It’s past time we all do the work to root out the ableism we’ve internalized. Even though—or because—we have MS or Crohn’s or asthma or astigmatism, as Mairs says, “our lives are too precious and delightful to us as they are.”

Related Posts

About Author

My Joy Is My Freedom

On the revolutionary act of choosing happiness as a Black, disabled woman.

Embracing my own joy now means that I didn’t always. Hope is my favorite word, but I didn’t always have it. Unfortunately, we live in a society that assumes joy is impossible for disabled people, associating disability only with sadness and shame. So my joy—the joy of professional and personal wins, of pop culture and books, of expressing platonic love out loud—is revolutionary in a body like mine. I say this without hyperbole, though fully aware that the thought may confuse, frighten, or anger people. As a Black woman with cerebral palsy, I know what it is like to encounter all three.

The face of the disability community is very white. People don’t often think of people of color or of LGBTQ+ people when they think of us. Instead, they think of cis white male wheelchair users who hate themselves, because that is so often the way pop culture depicts us. I’m not a cis heterosexual white male wheelchair user, so in pop culture, I don’t exist. That’s not okay because it’s not reality. I exist, I am a real person behind these words, and I deserve to be seen.

.css-1aear8u:before{margin:0 auto 0.9375rem;width:34px;height:25px;content:'';display:block;background-repeat:no-repeat;}.loaded .css-1aear8u:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/elle/static/images/quote.fddce92.svg);} .css-1bvxk2j{font-family:SaolDisplay,SaolDisplay-fallback,SaolDisplay-roboto,SaolDisplay-local,Georgia,Times,serif;font-size:1.625rem;font-weight:normal;line-height:1.2;margin:0rem;margin-bottom:0.3125rem;}@media(max-width: 48rem){.css-1bvxk2j{font-size:2.125rem;line-height:1.1;}}@media(min-width: 40.625rem){.css-1bvxk2j{font-size:2.125rem;line-height:1.2;}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-1bvxk2j{font-size:2.25rem;line-height:1.1;}}@media(min-width: 73.75rem){.css-1bvxk2j{font-size:2.375rem;line-height:1.2;}}.css-1bvxk2j b,.css-1bvxk2j strong{font-family:inherit;font-weight:bold;}.css-1bvxk2j em,.css-1bvxk2j i{font-style:italic;font-family:inherit;}.css-1bvxk2j i,.css-1bvxk2j em{font-style:italic;} "I live as unapologetically as I can each day—for myself, of course, but also for those…who will walk through the doors I hope to break down."

When I created #DisabledAndCute in 2017, I did so to capture a moment, a moment of trust in myself to keep choosing joy every single day. The hashtag was for me, first, and for my Black disabled joy. I wanted to celebrate how I finally felt that, in this Black and disabled body, I, too, deserved joy. The hashtag went viral and then global by the end of week two. When disabled people took to it to share their stories and journeys, I was floored and honored. There were naysayers who hated that I used the word cute and accused me of making inspiration porn, but the good responses outweighed the bad. So I live as unapologetically as I can each day—for myself, of course, but also for those who will come up after me, who will walk through the doors I hope to break down.

Living unapologetically looks like retweeting praise for my work or my book on Twitter. Calling out ableism, racism, and homophobia in marginalized communities through my writing. It means that I’ve literally stopped apologizing for the space I take up on stages or in airports—especially in airports, since I use their wheelchairs to get from gate to gate to avoid body pain—or anywhere else I exist. I’ve stopped saying sorry to the people around me as the airport attendant pushes me to my gate. I feel liberated.

I may not find joy every day. Some days will just be hard, and I will simply exist, and that’s okay, too. No one should have to be happy all the time—no one can be, with the ways in which life throws curveballs at us. On those days, it’s important not to mourn the lack of joy but to remember how it feels, to remember that to feel at all is one of the greatest gifts we have in life. When that doesn’t work, we can remind ourselves that the absence of joy isn’t permanent; it’s just the way life works sometimes. The reality of disability and joy means accepting that not every day is good but every day has openings for small pockets of joy. On the days I can’t get out of bed because my body pain is too great (a reality of my cerebral palsy), I write in the notes app on my phone or spend the day reading books or watching romantic comedies on the Hallmark Channel. These days and others that I carve out for self-care are necessary for my well-being.

Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century

For most of my life, hope, like joy, seemed to elude me—it felt impossible in a body like mine. I was once a very self-deprecating and angry person who scoffed at the idea of happiness and believed that I would die before I ever saw a day where I felt excited at the prospect of being alive. I realized I was wrong on a snowy day in 2016 just after Christmas, when I vowed to try to hold on to and nurture the feeling of joy, even if skeptically. I championed the act of effort and patience with myself by forcing myself to reroute negative thoughts with positive ones. Instead of saying what I hated about myself, I spoke aloud what I liked about myself.

In doing this, hope and joy became precious, sacred, a singular and collective journey. I shared my journey with the people who loved me before I ever thought I could. I shared my journey with the world because I wanted them all to know that who I am becoming is only possible because of who I was, and that is what makes it so beautiful. My joy is my freedom—it allows me to live my life as I see fit. I won’t leave this earth without the world knowing that I chose to live a life that made me happy, made me think, made me whole. I won’t leave this earth without the world knowing that I chose to live.

From Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century edited by Alice Wong, to be published on June 30, 2020 by Vintage Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Compilation copyright (c) 2019 by Alice Wong.

What to Read in 2024

Shelf Life: Anne Lamott

How Yulin Kuang Found Her Own ‘Love Story’

Shelf Life: Aly Raisman

Shelf Life: Julia Alvarez

Cameron Russell Is Unafraid

Percival Everett on 'James'

Lauren Oyler on 'No Judgment' and Criticism

Shelf Life: Téa Obreht

Carissa Broadbent On the Next 'Crowns of Nyaxia'

The Best Mystery and Thriller Books of 2024

Shelf Life: Cathleen Schine

My Problem With College Admissions Essays as a Disabled Person

As a 20-year-old transfer student who spent a summer studying abroad, dragging out the old same elegized story of my life as a young person “robbed of a normal carefree youth” is a bit boring. I’m tired of hearing my story, too. The story isn’t untrue or unworthy of being heard; it’s just so often associated with the disabled community that it becomes the only story expected of me. The disabled community is the largest marginalized minority in the world. There are many narratives worthy of being told, but so often they are overlooked for the inspiration porn , instantly shareable Facebook headlines.

Don’t get me wrong, I love a good overcoming adversity story. These stories are valid and so important. The essays I write for those college admissions boards, outside of how my disability affects my life, are not necessarily a Penguin Classics level work ready to be sent off to the closest corporate bookstore. The essay I try to write focuses more on my personal journey of self-discovery that genuinely starts out with “I’m a cliche” and goes on to wax poetic about the magic of soul searching. But when does the disabled community get to stop “overcoming adversity” and allow members to be known as individuals? My multiple sclerosis is an important part of my life, but as I’m sure many disabled kids who have applied to college can attest: it’s also the hardest to make sound not boring.

Personally, before I was diagnosed my life was a whole lot of sleeping all day, then vomiting if I ate anything. Really fun to relive as you beg a school for scholarship money, right? This is why I wholeheartedly believe college application essays are inherently ableist. I understand my privilege in this world as someone who was diagnosed later in her youth and was fortunate enough to have opportunities — like study abroad, or even being able to afford my medical care.

This is not what colleges want to hear about, though. Sure, maybe under the veil of how my disability affects such experiences and how I overcame it. (Spoiler: Sometimes I don’t; life for disabled people isn’t endless amounts of awe-inspiring obstacle climbing.) The personhood of any disabled person cannot be boiled down to one label. A disabled life is more than just one bad thing after another, so let me revel in the good once in a while.

Now, excuse me as I finish my Common App essay with this last line of lamenting my disabled experience. Hey, I still need that scholarship money.

We want to hear your story. Become a Mighty contributor here .

Image by contributor.

My journey to self-acceptance as disabled was full of realizations about what labels are and who gets to define them. I am disabled with a lot to say and not talented enough to join a punk band.

Disability Visibility

75 pages • 2 hours read

Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-first Century

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Part I: Being

Part II: Becoming

Part III: Doing

Part IV: Connecting

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Summary and Study Guide

Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century (2020) is an anthology of 37 nonfiction essays collected by disability rights activist Alice Wong. Each essay concerns a different aspect of what it means to be disabled, and the volume includes writings from people with physical, intellectual, psychiatric, and sensory disabilities. These essays center a broad array of topics, including medical trauma, personal relationships, career success, family dysfunction, art, activism, history, and politics.

Disability Visibility ’s model of disability studies and activism is thoroughly intersectional. Most of the contributing authors are queer, women, and/or people of color. Many of them draw specific attention to how these identities intersect with their disabilities and disabled status. Many are also multiply disabled, which they explore in varying degrees of detail.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,400+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,900+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

This text is one part of a broader effort called the Disability Visibility Project (DVP). Spearheaded by Wong, DVP is an ongoing multimedia project and digital community dedicated to collecting, preserving, and sharing disability media and culture. This banner includes several other books, a digital archive, a podcast, and a blog. Like DVP, Disability Visibility aims to capture and share a broad range of disabled experiences and perspectives. To make the text widely accessible, it is available in a variety of formats including an audiobook, a braille edition, a plain language summary, and an adaptation for young readers.

This guide references the eBook edition from Vintage Books, published in 2020.

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

CONTENT WARNING: This text (and this guide) contains extended discussions and depictions of ableism , medical abuse/malpractice, sexual assault, racism, sexism, classism, antisemitism, islamophobia, anti-queerness, eugenics, Nazism, physical injury, serious illness, and compulsory institutionalization. This book also contains frank discussions and depictions of human bodies, bodily fluids/waste (e.g.: blood, vomit, excrement, urine), sex and sexuality, and physical pain.

In her Introduction , editor Alice Wong introduces her work and the ethos behind this book: “I want to center the wisdom of disabled people […] Collectively, through our stories, our connections, and our actions, disabled people will continue to confront and transform the status quo” (xxii). The anthology comprises 37 nonfiction essays written by people with disabilities.

Harriet McBryde Johnson’s “Unspeakable Conversations” recalls her formal debate with Dr. Peter Singer at Princeton. On a personal level, Johnson finds Singer respectful and pleasant, but she regards his beliefs as genocidal towards disabled people.

“For Ki’tay D. Davidson, Who Loved Us” is a eulogy for disability rights advocate Ki’tay Davidson written by his surviving partner, Talila Lewis. Lewis celebrates Davidson’s identity as a Black, disabled, transgender man.

“If You Can’t Fast, Give” is a reflection by Maysoon Zayid, a Muslim performer with cerebral palsy. She writes about her experiences fasting during Ramadan .

In “There’s a Mathematical Equation that Proves I’m Ugly,” Ariel Henley describes the difficulties of growing up with facial deformities. The essay is built around a seventh-grade art lesson in which she recalls being taught “the golden ratio,” a mathematical formula created to objectively measure facial attractiveness.

“The Erasure of Indigenous People in Chronic Illness” recalls Jen Deerinwater’s experiences with anti-Indigenous racism in medical settings.

June Eric-Udorie’s “When You Are Waiting to Be Healed” charts her journey of self-acceptance. She grew up in a deeply religious family; her family members only acknowledged her disability when praying for God to “heal” it. As a young adult, Eric-Udorie finds a greater level of independence and self-esteem by acknowledging and accepting her disability.

“The Isolation of Being a Deaf Person in Prison” describes Jeremy Woody’s traumatic experiences as a deaf prisoner.

“Common Cyborg” concerns author Jillian Weise’s exploration of cyborg identity. She uses a prosthetic leg and defines cyborgs as disabled people who have technology incorporated into their bodies. She also refutes transhumanism from a disabled perspective .

“I’m Tired of Chasing a Cure” follows Liz Moore as they navigate life with chronic pain and bipolar disorder. Though they identify many things “wrong” with their body, they are tired of seeking relief through medicine and spiritual healing.

“We Can’t Go Back” by Ricardo T. Thornton Sr. is an excerpt from his statement before the US Senate. In it, he recounts his life’s story and argues that the intellectually disabled are fully capable of participating in society.

“Radical Visibility” discusses Sky Cubacub’s clothing brand, Rebirth Garments. Rebirth’s stated mission is to create fashionable and functional clothing for disabled and gender-nonconforming people.

Haben Girma’s “Guide Dogs Don’t Lead People. We Wander as One” centers on the dynamic she shares with her seeing-eye dog Mylo and describes the sensory experience of navigating together.

“Taking Charge of My Story as a Cancer Patient at the Hospital Where I Work” follows Diana Cejas through her residency at a hospital, centering on the fallout from her stroke and cancer diagnosis. She notices a unique social element to working at the hospital where she received treatment and struggles to adjust. As she recovers and progresses in her career, Cejas starts talking about her experiences on her own terms and hears other people’s stories in return.