- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Context of the Study – Writing Guide and Examples

Context of the Study – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Context of the Study

The context of a study refers to the set of circumstances or background factors that provide a framework for understanding the research question , the methods used, and the findings . It includes the social, cultural, economic, political, and historical factors that shape the study’s purpose and significance, as well as the specific setting in which the research is conducted. The context of a study is important because it helps to clarify the meaning and relevance of the research, and can provide insight into the ways in which the findings might be applied in practice.

Structure of Context of the Study

The structure of the context of the study generally includes several key components that provide the necessary background and framework for the research being conducted. These components typically include:

- Introduction : This section provides an overview of the research problem , the purpose of the study, and the research questions or hypotheses being tested.

- Background and Significance : This section discusses the historical, theoretical, and practical background of the research problem, highlighting why the study is important and relevant to the field.

- Literature Review: This section provides a comprehensive review of the existing literature related to the research problem, highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of previous studies and identifying gaps in the literature.

- Theoretical Framework : This section outlines the theoretical perspective or perspectives that will guide the research and explains how they relate to the research questions or hypotheses.

- Research Design and Methods: This section provides a detailed description of the research design and methods, including the research approach, sampling strategy, data collection methods, and data analysis procedures.

- Ethical Considerations : This section discusses the ethical considerations involved in conducting the research, including the protection of human subjects, informed consent, confidentiality, and potential conflicts of interest.

- Limitations and Delimitations: This section discusses the potential limitations of the study, including any constraints on the research design or methods, as well as the delimitations, or boundaries, of the study.

- Contribution to the Field: This section explains how the study will contribute to the field, highlighting the potential implications and applications of the research findings.

How to Write Context of the study

Here are some steps to write the context of the study:

- Identify the research problem: Start by clearly defining the research problem or question you are investigating. This should be a concise statement that highlights the gap in knowledge or understanding that your research seeks to address.

- Provide background information : Once you have identified the research problem, provide some background information that will help the reader understand the context of the study. This might include a brief history of the topic, relevant statistics or data, or previous research on the subject.

- Explain the significance: Next, explain why the research is significant. This could be because it addresses an important problem or because it contributes to a theoretical or practical understanding of the topic.

- Outline the research objectives : State the specific objectives of the study. This helps to focus the research and provides a clear direction for the study.

- Identify the research approach: Finally, identify the research approach or methodology you will be using. This might include a description of the data collection methods, sample size, or data analysis techniques.

Example of Context of the Study

Here is an example of a context of a study:

Title of the Study: “The Effectiveness of Online Learning in Higher Education”

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced many educational institutions to adopt online learning as an alternative to traditional in-person teaching. This study is conducted in the context of the ongoing shift towards online learning in higher education. The study aims to investigate the effectiveness of online learning in terms of student learning outcomes and satisfaction compared to traditional in-person teaching. The study also explores the challenges and opportunities of online learning in higher education, especially in the current pandemic situation. This research is conducted in the United States and involves a sample of undergraduate students enrolled in various universities offering online and in-person courses. The study findings are expected to contribute to the ongoing discussion on the future of higher education and the role of online learning in the post-pandemic era.

Context of the Study in Thesis

The context of the study in a thesis refers to the background, circumstances, and conditions that surround the research problem or topic being investigated. It provides an overview of the broader context within which the study is situated, including the historical, social, economic, and cultural factors that may have influenced the research question or topic.

Context of the Study Example in Thesis

Here is an example of the context of a study in a thesis:

Context of the Study:

The rapid growth of the internet and the increasing popularity of social media have revolutionized the way people communicate, connect, and share information. With the widespread use of social media, there has been a rise in cyberbullying, which is a form of aggression that occurs online. Cyberbullying can have severe consequences for victims, such as depression, anxiety, and even suicide. Thus, there is a need for research that explores the factors that contribute to cyberbullying and the strategies that can be used to prevent or reduce it.

This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and cyberbullying among adolescents in the United States. Specifically, the study will examine the following research questions:

- What is the prevalence of cyberbullying among adolescents who use social media?

- What are the factors that contribute to cyberbullying among adolescents who use social media?

- What are the strategies that can be used to prevent or reduce cyberbullying among adolescents who use social media?

The study is significant because it will provide valuable insights into the relationship between social media use and cyberbullying, which can be used to inform policies and programs aimed at preventing or reducing cyberbullying among adolescents. The study will use a mixed-methods approach, including both quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon of cyberbullying among adolescents who use social media.

Context of the Study in Research Paper

The context of the study in a research paper refers to the background information that provides a framework for understanding the research problem and its significance. It includes a description of the setting, the research question, the objectives of the study, and the scope of the research.

Context of the Study Example in Research Paper

An example of the context of the study in a research paper might be:

The global pandemic caused by COVID-19 has had a significant impact on the mental health of individuals worldwide. As a result, there has been a growing interest in identifying effective interventions to mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic on mental health. In this study, we aim to explore the impact of a mindfulness-based intervention on the mental health of individuals who have experienced increased stress and anxiety due to the pandemic.

Context of the Study In Research Proposal

The context of a study in a research proposal provides the background and rationale for the proposed research, highlighting the gap or problem that the study aims to address. It also explains why the research is important and relevant to the field of study.

Context of the Study Example In Research Proposal

Here is an example of a context section in a research proposal:

The rise of social media has revolutionized the way people communicate and share information online. As a result, businesses have increasingly turned to social media platforms to promote their products and services, build brand awareness, and engage with customers. However, there is limited research on the effectiveness of social media marketing strategies and the factors that contribute to their success. This research aims to fill this gap by exploring the impact of social media marketing on consumer behavior and identifying the key factors that influence its effectiveness.

Purpose of Context of the Study

The purpose of providing context for a study is to help readers understand the background, scope, and significance of the research being conducted. By contextualizing the study, researchers can provide a clear and concise explanation of the research problem, the research question or hypothesis, and the research design and methodology.

The context of the study includes information about the historical, social, cultural, economic, and political factors that may have influenced the research topic or problem. This information can help readers understand why the research is important, what gaps in knowledge the study seeks to address, and what impact the research may have in the field or in society.

Advantages of Context of the Study

Some advantages of considering the context of a study include:

- Increased validity: Considering the context can help ensure that the study is relevant to the population being studied and that the findings are more representative of the real world. This can increase the validity of the study and help ensure that its conclusions are accurate.

- Enhanced understanding: By examining the context of the study, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of the factors that influence the phenomenon under investigation. This can lead to more nuanced findings and a richer understanding of the topic.

- Improved generalizability: Contextualizing the study can help ensure that the findings are applicable to other settings and populations beyond the specific sample studied. This can improve the generalizability of the study and increase its impact.

- Better interpretation of results: Understanding the context of the study can help researchers interpret their results more accurately and avoid drawing incorrect conclusions. This can help ensure that the study contributes to the body of knowledge in the field and has practical applications.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Surviving and Thriving in Postgraduate Research pp 305–348 Cite as

How Should I Contextualise and Position My Study?

- Ray Cooksey 3 &

- Gael McDonald 4

- First Online: 28 June 2019

1853 Accesses

The focus of this chapter is on contextualising and positioning your research, which involves clarifying your assumptions, stating your intentions and goals and drawing boundaries around your research and its context(s). When you appropriately contextualise your study, you are making clear (1) where you, as researcher, well as your data sources, as participants, are coming from (‘positioning’ arguments) as well as larger contextual considerations (e.g., ethics, stakeholders); (2) what assumptions you are making in order to make your research ‘do-able’; (3) what you will/will not be addressing in your research (e.g., encompassing research goals, frames, literature foundations, questions and/or hypotheses) and why; (4) what contributions and impacts you see your research making, and, importantly, (5) what your research context(s) are and their implications for what you can do and what you may learn. Influences on your research may come from any of these domains, so a crucial part of your research journey will be recognising, balancing and managing the most relevant and impactful of these contextual influences, dealing effectively with constraints and being opportunistic where the need arises – all in pursuit of carrying out a convincing research project.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

AIATSIS. (2012). Guidelines for ethical research in Australian Indigenous studies . Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Google Scholar

Allen, P., Maguire, S., & McKelvey, B. (Eds.). (2011). The Sage handbook of complexity and management . Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Beach, L. R. (Ed.). (1998). Image theory: Theoretical and empirical foundations . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Benzies, K. M., Premji, S., Hayden, K. A., & Serrett, K. (2006). State-of-the-evidence reviews: Advantages and challenges of including grey literature. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 2, 55–61.

Article Google Scholar

Brunswik, E. (1952). The conceptual framework of psychology . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brunswik, E. (1956). Perception and the representative design of psychological experiments (2nd ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2015). Business research methods (4th ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, R., et al. (2012). Evaluating meta ethnography: Systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technology Assessment , 15 (43).

Cooksey, R. W. (1996). Judgment analysis: Theory, methods, and applications . San Diego: Academic Press.

Chilisa, B. (2012). Indigenous research methodologies . Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education (7th ed.). New York: Routledge.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Doyle, L. H. (2003). Synthesis through meta-ethnography: Paradoxes, enhancements, and possibilities. Qualitative Research, 3 (3), 321–344.

Fisher, C. (2010). Researching and writing a dissertation: A guidebook for business students (3rd ed.). Harlow, UK: Prentice Education Ltd.

Gigerenzer, G., Todd, P. M., & The ABC Research Group. (1999). Simple heuristics that make us smart . New York: Oxford University Press.

Gregson, W. (2016). Harnessing sources of innovation, useful knowledge and leadership within a complex public sector agency network: A reflective practice perspective. Unpublished PhD.I portfolio, UNE Business School, University of New England, Armidale, NSW.

Hammond, K. R. (1996). Human judgment and social policy . New York: Oxford University Press.

Hammond, K. R., & Stewart, T. R. (Eds.). (2001). The essential Brunswik: Beginnings, explications, applications . New York: Oxford University Press.

Hattie, J. A. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement . London: Routledge.

Kaptchuk, T. J. (2001). The double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial: Gold standard or golden calf? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54 (6), 541–549.

Kaptchuk, T. J. (2003). Effect of interpretive bias on research evidence. BMJ, 326 , 1453–1455.

Kovach, M. (2009). Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations, and contexts . Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Lewis, V., & Habeshaw, S. (1997). 53 interesting ways to supervise student projects, dissertations and theses . Bristol, UK: Technical and Educational Services Ltd.

Lichtenstein, S. A., & Slovic, P. (Eds.). (2006). The construction of preference . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mauthner, M., Jessop, J., Miller, T., & Birch, M. (2012). Ethics in qualitative research (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

NHMRC, ARC, & UA (2018). National statement on ethical conduct in human research 2007 (updated 2018) . The National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian Research Council and Universities Australia. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

NHMRC. (2018). Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities: Guidelines for researchers and stakeholders . Canberra, Australia: The National Health and Medical Research Council.

Robson, M. (2011). The use and disclosure of intuition(s) by leaders in Australian organisations: A grounded theory . Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, School of Economics, Business & Public Policy, University of New England, Armidale, NSW.

Schuelka, M., & Maxwell, T. W. (Eds.). (2016). Education in Bhutan: Culture, schooling, and gross national happiness . Singapore: Springer Science.

Senge, P. M. (1994). The fifth discipline fieldbook: Strategies and tools for building a learning organization . New York: Crown Business.

Sinclair, M. (Ed.). (2014). Handbook of research methods on intuition . Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishers.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (Eds.). (2010). Sage handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Thomas, R. M., & Brubaker, D. L. (2008). Theses and dissertations: A guide to planning, research and writing (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Walsh, D., & Downe, S. (2005). Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 50 (2), 204–211.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

UNE Business School, University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia

Ray Cooksey

RMIT University Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Gael McDonald

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ray Cooksey .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Cooksey, R., McDonald, G. (2019). How Should I Contextualise and Position My Study?. In: Surviving and Thriving in Postgraduate Research. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7747-1_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7747-1_10

Published : 28 June 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-13-7746-4

Online ISBN : 978-981-13-7747-1

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 22 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Chapter 4: Writing the Methods Section

Methods Goal 1: Contextualize the Study’s Methods

The first goal of writing your Methods section is to contextualize (provide context or a “picture” of) the procedures you followed to conduct the research. Doing this requires attention to detail. Some of the possible ways that you can accomplish this goal will be discussed later in the chapter, but first, let’s look at some examples of Methods sections from published research articles in high-impact journals (the parts of the Methods that contain Goal 1 language are bolded ):

- Volumetric gas concentrations obtained from the gas analyzers were converted into mass concentrations with the ideal gas law by using the mean reactor room temperature and assuming one atmosphere pressure. Gas release is defined in this article as the process of gas transferring through the liquid manure surface into the free air stream of the reactor headspace. Gas emission is defined as the process of gas emanating from the reactor into the outdoor atmosphere. Gas release does not equal gas emission under transient conditions, although it does under steady-state conditions. The rate of gas emission from a reactor was calculated with equation 1: Equation (1) where QGe is gas emission rate (mass min-1), CGex is exhaust gas concentration (mass L-1), CGin is inlet gas concentration (mass L-1), and Qv is reactor airflow rate (L min-1). The gas release rate was approximated with the rates of change in gas mass in the reactor headspace with equation 2: Equation (2) where QGr is gas release rate (mass min-1), CGh is gas concentration in the headspace (mass L-1), and Vh is headspace air volume (L). In this article, we assumed that CGh was equal to CGex. To use the sampled data obtained in this study, equation 2 was discretized to equation 3: Equation (3) where __delta__t is sampling interval (min), and k is sample number (k = 0, 1, 2, … ). Gas release flux was calculated with equation 4: Equation (4) where qGr is gas release flux (mass m-2 in-1), and A is area of reactor manure surface (m2) . [1]

- The participants were employees of a medium-sized firm in the telecommunications industry. The sampling frame was the list of 3,402 potential users of the new ERP system. We received 2,794 usable responses across all points of measurement, resulting in an effective response rate of just over 82 percent. Our sample comprised 898 women (32 percent). The average age of the participants was 34.7, with a standard deviation of 6.9. All levels of the organizational hierarchy were adequately represented in the sample and were in proportion to the sampling frame. While ideally we would have wanted all potential participants to provide responses in all waves of the data collection, this was particularly difficult given that the study duration was 12 months and had multiple points of measurement. Thus, the final sample of 2,794 was determined after excluding those who did not respond despite follow-ups, those who had left the organization, those who provided incomplete responses, or who did not choose to participate for other reasons. Yet, we note that the response rate was quite high for a longitudinal field study; this was, in large part, due to the strong organizational support for the survey and the employees’ desire to provide reactions and feedback to the new system. Although we did not have any data from the non-respondents, we found that the percentage of women, average age, and percentages of employees in various organizational levels in the sample were consistent with those in the sampling frame. Employees were told that they would be surveyed periodically for a year in order to help manage the new ERP system implementation. Employees were told that the data would also be used as part of a research study and were promised confidentiality, which was strictly maintained . [2]

So, as you can see in the excerpts above, the writers are providing lots of detailed information that contextualizes the study. To contextualize methods means that you explain all of the conditions in which the study occurred. It might be helpful for you to think of answering the questions who, what, when, where, how, and why.

Goal 1, Contextualizing the Study Methods, means that you completely describe the circumstances surrounding the research. There are several strategies you can use to help you successfully achieve this goal in a detailed manner.

Strategies for Methods Communicative Goal 1: Contextualizing the Study Methods

- Referencing previous works

- Providing general information

- Identifying the methodological approach

- Describing the setting

- Introducing the subjects/participants

- Rationalizing pre-experiment decisions

Methods Goal 1 Strategy: Referencing Previous Works

Referencing previous works is a strategy used to relate your research to the literature. The strategy involves a direct reference to another author or an explicit mention of a study.

Here are two examples taken from published research articles:

- The entire experiment consisted of six situations, and each situation was tested employing one advertisement. The balanced Latin-square method proposed by Edwards (1951) was used to arrange the six experimental situations. To simplify the respondents’ choices with regard to order and sequence, all of the print advertisements tested were appropriately arranged in the experimental design. [3]

- The Eulerian-granular model in ANSYS 12.0 was used to model the interactions between three phases: one gaseous phase and two granular particle phases within a fluidized bed taken from the literature [32] . This model was chosen over the Eulerian-Lagrangian models as it is computationally more efficient with regards to time and memory. [4]

Methods Goal 1 Strategy: Providing General Information

Providing general information allows a writer to give the background that is specific to the methods. This can be theoretical, empirical, informational, or experiential background to the methodology of the study. You can use this strategy to build a bridge for the reader. The bridge should connect your study to other studies that have utilized the same or similar methodology. This strategy also encompasses any preliminary hypotheses or interpretations that you may want to make.

- The animals used during this study were slaughtered in accredited slaughterhouses according to the rules on animal protection defined by French law (Code Rural, articles R214-64 to R214-71, http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr). The Qualvigene program, described in detail elsewhere (Allais et al., 2010), was a collaborative research program involving AI companies, INRA (the French National Institute for Agricultural Research) and the Institut de l’Elevage (Breeding Institute) in France. The program was initiated to study the genetic determinism of beef and meat quality traits (Malafosse et al., 2007). [5]

- This study focused on stemwood when examining alternative woody biomass management regimes for loblolly pine. PTAEDA3.1, developed with data from a wide range of loblolly pine plantations in the southern United States, was used to simulate growth as well as competition and mortality effects and predict yields of various management scenarios (Bullock and Burkhart 2003, Burkhart et al. 2004). [6]

Methods Goal 1 Strategy: Identifying the Methodological Approach

Identifying the methodological approach allows a writer to pinpoint the exact method that was adopted to accomplish the study’s goals. This is a strategy you would use if there was a specific set of procedures for your approach or, in some cases, even a predetermined framework for how to carry out the study. The main purpose of this step is to introduce the methodological approach or experimental design used for the current study to inform the reader of the selected approach, announce credible research practices known in the field, and possibly transition to describing the experimental procedures.

Consider the following examples:

- In both seasons, the experiments were arranged in a complete randomized block design with four replications, using a plot size of 3.45m x 15m each containing 114 plants. Three levels of organic supplementation [0 kgm-2 (S0), 0.35 kgm-2 (S0.35) and 0.70 kgm-2 (S0.70)] were incorporated into the soil 2 days before solarization. [7]

- To address these hypotheses rigorously, we conducted a randomized controlled trial with children clustered within schools. All three interventions were delivered by the same teaching assistant in each school. [8]

Methods Goal 1 Strategy: Describing the Setting

Describing the setting of the study is simply telling the reader about where or under what conditions the study happened. The setting is all about the place , conditions, and surroundings. In other words, this strategy details the characteristics of the environment in which the research was conducted, which often answers the “where” and “when” questions. Information may include details about the place and temperature; it may also include some temporal (or time-related) descriptors such as the time of the year. It should be noted that this step may overlap with some steps in Goal 2 (which describes the tools used or the experimental procedures conducted), but it remains distinct from them in that describing the setting specifically references the inherent characteristics of the context or environment in which the study took place, and not the characteristics of the materials used to accomplish the experiment or to affect some change in the subject that is being examined. You’ll read more about this in the next chapter.

- The mares were admitted at day 310 of pregnancy, housed in wide straw bedding boxes and fed with hay and concentrates twice a day. [9]

- All three studies were performed in the eastern half of the SRS in the RCW management area (US Department of Energy 2005). [10]

Methods Goal 1 Strategy: Introducing the Subjects/Participants

Introducing the subjects or participants in your study helps you to describe the characteristics of your sample. Whether you have human, animal, or inanimate participants or subjects, you will still need to provide the reader with a careful description of them. For a study involving humans, this answers the “who” question. For studies without humans, this often answers the “what” question. It should be noted, however, that not all disciplines have subjects/participants, but when subjects/participants can be identified, this step helps to describe subjects/participants and their original/pre-experimental characteristics, properties, origin, number, composition/construction, etc. The step also details the process by which subjects/participants were recruited/selected.

Below are a couple of examples excerpted from published reports of research with the relevant language in bold to illustrate how the words/phrases work to implement the strategy, which then works to accomplish the goal:

- Participants in this study included 10 TAs enrolled in this French doctoral program. [11]

- The Mexican populations, Chetumal and Tulum ( Mex-1 and Mex-2, respectively) , have large resin-producing glands, while the Venezuelan populations, Tovar and Caracas (Ven-1 and Ven-2, respectively) , have smaller glands. [12]

The Academic Phrasebank website provides a list of sentence starters that would indicate the use of this strategy. Here are a few examples:

Methods Goal 1 Strategy: Rationalizing Pre-Experiment Conditions

Rationalizing pre-experiment conditions is a way to show the reader how you attained your specific sample or how you decided about the methods you chose prior to actually carrying out the experimental procedures of the study.

- The literature review presented above leads us to formulate our research questions more precisely. First, we ask whether there is a difference in well-being between the unemployed and those currently employed. [13]

- We defined two sub-samples of LAEs split at R = 25.5. The continuum-bright (UV-bright hereafter) sub-sample of 118 LAEs enables a direct comparison with the SED parameters of R less than 25.5 “BX,” star-forming galaxies in the same range of redshift (Steidel et al. 2004). The remaining 98 LAEs are classified as UV-faint. [14]

Keep in mind that the Methods section is very important. Even if readers are skimming a published article, they typically read the methods with careful attention to the details provided. Because Methods sections are often rote narratives of procedures, there are several frequently adopted words or phrases that are standard. The Academic Phrasebank website provides a list of these, which are summarized in the table below:

Overall, there is a lot of example language that you may use to incorporate as you write the Methods section. Using the goals and strategies as a guide, you can choose the words and phrases suggested to ensure that your methods are appropriately detailed and clear.

Key Takeaways

Goal #1 of writing the Methods section is related to Contextualizing the Study’s Methods. There are six possible strategies that you can use to accomplish this goal:

- Referencing previous works and/or

- Providing general information and/or

- Identifying the methodological approach and/or

- Describing the setting and/or

- Introducing the subjects/participants and/or

Remember: You do not need to include all of these strategies — they are simply possibilities for reaching the goal of Contextualizing the Study’s Methods.

- Ni, J. Q., Heber, A. J., Kelly, D. T., & Sutton, A. L. (1998). Mechanism of gas release from liquid swine wastes. In 2001 ASAE Annual Meeting (p. 1). American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers . ↵

- Morris, M. G., & Venkatesh, V. (2010). Job characteristics and job satisfaction: Understanding the role of enterprise resource planning system implementation. Mis Quarterly, 143-161. ↵

- Lin, P. C., & Yang, C. M. (2010). Impact of product pictures and brand names on memory of Chinese metaphorical advertisements. International Journal of Design, 4 (1). ↵

- Armstrong, L. M., Gu, S., & Luo, K. H. (2011). Effects of limestone calcination on the gasification processes in a BFB coal gasifier. Chemical Engineering Journal, 168 (2), 848-860. ↵

- Allais, S., Journaux, L., Levéziel, H., Payet-Duprat, N., Raynaud, P., Hocquette, J. F., ... & Renand, G. (2011). Effects of polymorphisms in the calpastatin and µ-calpain genes on meat tenderness in 3 French beef breeds. Journal of Animal Science, 89 (1), 1-11. ↵

- Guo, Z., Grebner, D., Sun, C., & Grado, S. (2010). Evaluation of Loblolly pine management regimes in Mississippi for biomass supplies: a simulation approach. Southern Journal of Applied Forestry, 34 (2), 65-71. ↵

- Mauromicale, G., Longo, A. M. G., & Monaco, A. L. (2011). The effect of organic supplementation of solarized soil on the quality of tomato fruit. Scientia Horticulturae, 129 (2), 189-196. ↵

- Clarke, P. J., Snowling, M. J., Truelove, E., & Hulme, C. (2010). Ameliorating children’s reading-comprehension difficulties: A randomized controlled trial. Psychological Science, 21( 8), 1106-1116. ↵

- Castagnetti, C., Mariella, J., Serrazanetti, G. P., Grandis, A., Merlo, B., Fabbri, M., & Mari, G. (2007). Evaluation of lung maturity by amniotic fluid analysis in equine neonate. Theriogenology, 67 (9), 1455-1462. ↵

- Goodrick, S. L., Shea, D., & Blake, J. (2010). Estimating fuel consumption for the upper coastal plain of South Carolina. Southern Journal of Applied Forestry, 34 (1), 5-12. ↵

- Mills, N. (2011). Teaching assistants’ self‐efficacy in teaching literature: Sources, personal assessments, and consequences. The Modern Language Journal, 95 (1), 61-80. ↵

- Pélabon, C., Carlson, M. L., Hansen, T. F., Yoccoz, N. G., & Armbruster, W. S. (2004). Consequences of inter‐population crosses on developmental stability and canalization of floral traits in Dalechampia scandens (Euphorbiaceae). Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 17 (1), 19-32. ↵

- Ervasti, H., & Venetoklis, T. (2010). Unemployment and subjective well-being: An empirical test of deprivation theory, incentive paradigm and financial strain approach. Acta Sociologica, 53 (2), 119-139. ↵

- Guaita, L., Acquaviva, V., Padilla, N., Gawiser, E., Bond, N. A., Ciardullo, R., ... & Schawinski, K. (2011). Lyα-emitting galaxies at z= 2.1: Stellar masses, dust, and star formation histories from spectral energy distribution fitting. The Astrophysical Journal, 733 (2), 114. ↵

Preparing to Publish Copyright © 2023 by Sarah Huffman; Elena Cotos; and Kimberly Becker is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Five steps every researcher should take to ensure participants are not harmed and are fully heard

Professor of Physical Geography, University of the Witwatersrand

Disclosure statement

Jasper Knight does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of the Witwatersrand provides support as a hosting partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

Academic research is not always abstract or theoretical. Nor does it take place in a vacuum. Research in many different disciplines is often grounded in the real world; it aims to understand and address problems that affect people and the environment, such as climate change, poverty, migration or natural hazards.

This means researchers often have to interact with and collect data from a wide range of different people in government, industry and civil society. These are known as research participants.

Over the last 50 years, the relationship between researcher and participant has fundamentally changed . Previously, research participants were viewed merely as objects of study. They had little input into the research process or its outcomes. Now, participants are increasingly viewed as collaborative partners and co-creators of knowledge. There are also many ways in which they can engage with researchers. This shift has been largely driven by the need for research that is relevant to today’s world as well as greater recognition of the diversity of people and cultures, and the internet, social media and other communication tools.

In this context, ethical research practices are more important than ever. However, guidelines and standards for research ethics vary between country and institution. Expectations may also vary between disciplines. So, it’s a good time to identify the key issues in human research ethics that transcend institutional or disciplinary differences.

Issues to consider

I am a long-time chair of one my institutions’ research ethics committees, and I do research ethics training for researchers and managers across southern Africa. I have also published on research ethics. Based on this experience and drawing from other work done on the topic , I suggest there are five critical ethics issues for researchers to consider.

Managing vulnerability: Research participants, especially in the developing world, may be potentially vulnerable to coercion, exploitation and the exertion of soft power.

This vulnerability may arise because of systemic social, economic, political and cultural inequalities, which are particularly marked in developing countries. And it may be amplified by inequalities in healthcare and education. Some groups in any society – among them minors, people with disabilities, prisoners, orphans, refugees, and those with stigmatised conditions like HIV and AIDS or albinism – may be more vulnerable than others.

This issue can be managed by considering what the participant group is like and by making sure that the data collection process does not increase any existing vulnerabilities.

Obtaining informed consent: This is a key precondition for participation in any study. Potential participants should first be informed about the nature of the study and the terms and conditions of their participation. That includes details about anonymity, confidentiality and their right to withdraw.

The researcher then needs to ensure that the potential participant understands this information and has the opportunity to ask questions. This should be done in a language and using words that the person can understand. After these steps are taken, the participant can give informed consent. Informal (verbal or any other non-written) consent is more appropriate if participants are not literate or are particularly vulnerable.

Protecting people: The overarching principle of protecting research participants was articulated in the landmark Belmont Report . The report emerged from a national commission in the US in the 1970s to consider research ethics principles. It called for researchers in any study to demonstrate non-maleficence (the principle of not doing harm) and ensure that they protect both participants and their data.

This can be done at different stages through the research process: by decreasing the potential for risk or harm through careful study design; by providing support or counselling services to participants during or after data collection; and by maintaining confidentiality and anonymity in data collection and reporting. Finally, personal data must be protected or de-identified if they are being stored for later analysis.

Managing risk: Potential sources of risk or harm to participants should, as far as possible, be identified and mitigated when the study is being designed. Risk may arise in any study, either at the time of data collection or afterwards. Sometimes this is unexpected, such as where data collection becomes more dangerous due to civil unrest or under COVID-19 restrictions.

It is important that researchers provide the details of support or counselling service for participants in case these are needed. Any trade-offs between risk and benefits can be considered through a risk-benefits analysis. But researchers should be realistic about any potential benefits that may result from their study.

Championing human rights: Researchers have responsibilities: to their disciplines, funders, institutions and participants. This means they should not merely be passive analysers of data. Instead they should be positive role models in society by seeking solutions, advocating for change and upholding human rights and social justice through their actions.

Research activities, especially those involving participants, should address and find solutions for local and global problems. They ought to result in positive societal and environmental outcomes. This should be the context for all types of research activities in a 21st century world.

Making it happen

Increasingly, there are national and international codes of research ethics, guiding researchers in different fields. An example is the 2010 Singapore Statement on Research Integrity . It emphasises the principles of honesty, accountability, professional courtesy and fairness, and good stewardship of data. These are the characteristics not just of ethical researchers, but of good researchers too.

These principles and processes should make research less risky and protect the rights of participants by building trust between researchers and participants. These principles can also help in making research more transparent, accountable and equitable – critical in an increasingly divided and unequal world.

- Risk management

- Research ethics

- Data privacy

- Informed consent

- Researchers

Senior Lecturer - Earth System Science

Operations Coordinator

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

Reporting Participant Characteristics in a Research Paper

A report on a scientific study using human participants will include a description of the participant characteristics. This is included as a subsection of the “Methods” section, usually called “Participants” or “Participant Characteristics.” The purpose is to give readers information on the number and type of study participants, as a way of clarifying to whom the study findings apply and shedding light on the generalizability of the findings as well as any possible limitations. Accurate reporting is needed for replication studies that might be carried out in the future.

The “Participants” subsection should be fairly short and should tell readers about the population pool, how many participants were included in the study sample, and what kind of sample they represent, such as random, snowball, etc. There is no need to give a lengthy description of the method used to select or recruit the participants, as these topics belong in a separate “Procedures” subsection that is also under “Methods.” The subsection on “Participant Characteristics” only needs to provide facts on the participants themselves.

Report the participants’ genders (how many male and female participants) and ages (the age range and, if appropriate, the standard deviation). In particular, if you are writing for an international audience, specify the country and region or cities where the participants lived. If the study invited only participants with certain characteristics, report this, too. For example, tell readers if the participants all had autism, were left-handed, or had participated in sports within the past year.

Related: Finished preparing the methods sections for your research paper ? Find out why the “Methods” section is so important now!

Next, use your judgment to identify other pieces of information that are relevant to the study. For a detailed tutorial on reporting “Participant Characteristics,” see Alice Frye’s “Method Section: Describing participants.” Frye reminds authors to mention if only people with certain characteristics or backgrounds were included in the study. Did all the participants work at the same company? Were the students at the same school? Did they represent a range of socioeconomic backgrounds? Did they come from both urban and rural backgrounds? Were they physically and emotionally healthy? Similarly, mention if the study sample excluded people with certain characteristics.

If you are going to examine any participant characteristics as factors in the analysis, include a description of these. For instance, if you plan to examine the influence of teachers’ years of experience on their attitude toward new technology, then you should report the range of the teachers’ years of experience. If you plan to study how children’s socioeconomic level relates to their test scores, you should briefly mention that the children in the sample came from low, middle, and high-income backgrounds. Finally, mention whether the participants participated voluntarily. Include information on whether they gave informed consent (if the participants were children, mention that their parents consented to their participation). Also, mention if the participants received any sort of compensation or benefit for their participation, such as money or course credit.

Case Studies and Qualitative Reports

Case studies and qualitative reports may have only a few participants or even a single participant. If there is space to do so, you can write a brief background of each participant in the “Participants” section and include relevant information on the participant’s birthplace, current place of residence, language, and any life experience that is relevant to the study theme. If you have permission to use the participant’s name, do so. Otherwise, use a different name and add a note to readers that the name is a pseudonym. Alternatively, you might label the participants with numbers (e.g., Student 1, Student 2) or letters (e.g., Doctor A, Doctor B, etc.), or use initials to identify them (e.g., KY, JM).

Use Past Tense

Remember to use past tense when writing the “Participants” section . This is because you are describing what the participants’ characteristics were at the time of data collection . By the time your article is published, the participants’ characteristics may have changed. For example, they may be a year older and have more work experience. Their socioeconomic level may have changed since the study. In some cases, participants may even have passed away. While characteristics like gender and race are either unlikely or impossible to change, the whole section is written in the past tense to maintain a consistent style and to avoid making unsupported claims about what the participants’ current status is.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- AI in Academia

- Infographic

- Manuscripts & Grants

- Reporting Research

- Trending Now

Can AI Tools Prepare a Research Manuscript From Scratch? — A comprehensive guide

As technology continues to advance, the question of whether artificial intelligence (AI) tools can prepare…

Abstract Vs. Introduction — Do you know the difference?

Ross wants to publish his research. Feeling positive about his research outcomes, he begins to…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Demystifying Research Methodology With Field Experts

Choosing research methodology Research design and methodology Evidence-based research approach How RAxter can assist researchers

- Manuscript Preparation

- Publishing Research

How to Choose Best Research Methodology for Your Study

Successful research conduction requires proper planning and execution. While there are multiple reasons and aspects…

Top 5 Key Differences Between Methods and Methodology

While burning the midnight oil during literature review, most researchers do not realize that the…

How to Draft the Acknowledgment Section of a Manuscript

Discussion Vs. Conclusion: Know the Difference Before Drafting Manuscripts

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Writing Survey Questions

Perhaps the most important part of the survey process is the creation of questions that accurately measure the opinions, experiences and behaviors of the public. Accurate random sampling will be wasted if the information gathered is built on a shaky foundation of ambiguous or biased questions. Creating good measures involves both writing good questions and organizing them to form the questionnaire.

Questionnaire design is a multistage process that requires attention to many details at once. Designing the questionnaire is complicated because surveys can ask about topics in varying degrees of detail, questions can be asked in different ways, and questions asked earlier in a survey may influence how people respond to later questions. Researchers are also often interested in measuring change over time and therefore must be attentive to how opinions or behaviors have been measured in prior surveys.

Surveyors may conduct pilot tests or focus groups in the early stages of questionnaire development in order to better understand how people think about an issue or comprehend a question. Pretesting a survey is an essential step in the questionnaire design process to evaluate how people respond to the overall questionnaire and specific questions, especially when questions are being introduced for the first time.

For many years, surveyors approached questionnaire design as an art, but substantial research over the past forty years has demonstrated that there is a lot of science involved in crafting a good survey questionnaire. Here, we discuss the pitfalls and best practices of designing questionnaires.

Question development

There are several steps involved in developing a survey questionnaire. The first is identifying what topics will be covered in the survey. For Pew Research Center surveys, this involves thinking about what is happening in our nation and the world and what will be relevant to the public, policymakers and the media. We also track opinion on a variety of issues over time so we often ensure that we update these trends on a regular basis to better understand whether people’s opinions are changing.

At Pew Research Center, questionnaire development is a collaborative and iterative process where staff meet to discuss drafts of the questionnaire several times over the course of its development. We frequently test new survey questions ahead of time through qualitative research methods such as focus groups , cognitive interviews, pretesting (often using an online, opt-in sample ), or a combination of these approaches. Researchers use insights from this testing to refine questions before they are asked in a production survey, such as on the ATP.

Measuring change over time

Many surveyors want to track changes over time in people’s attitudes, opinions and behaviors. To measure change, questions are asked at two or more points in time. A cross-sectional design surveys different people in the same population at multiple points in time. A panel, such as the ATP, surveys the same people over time. However, it is common for the set of people in survey panels to change over time as new panelists are added and some prior panelists drop out. Many of the questions in Pew Research Center surveys have been asked in prior polls. Asking the same questions at different points in time allows us to report on changes in the overall views of the general public (or a subset of the public, such as registered voters, men or Black Americans), or what we call “trending the data”.

When measuring change over time, it is important to use the same question wording and to be sensitive to where the question is asked in the questionnaire to maintain a similar context as when the question was asked previously (see question wording and question order for further information). All of our survey reports include a topline questionnaire that provides the exact question wording and sequencing, along with results from the current survey and previous surveys in which we asked the question.

The Center’s transition from conducting U.S. surveys by live telephone interviewing to an online panel (around 2014 to 2020) complicated some opinion trends, but not others. Opinion trends that ask about sensitive topics (e.g., personal finances or attending religious services ) or that elicited volunteered answers (e.g., “neither” or “don’t know”) over the phone tended to show larger differences than other trends when shifting from phone polls to the online ATP. The Center adopted several strategies for coping with changes to data trends that may be related to this change in methodology. If there is evidence suggesting that a change in a trend stems from switching from phone to online measurement, Center reports flag that possibility for readers to try to head off confusion or erroneous conclusions.

Open- and closed-ended questions

One of the most significant decisions that can affect how people answer questions is whether the question is posed as an open-ended question, where respondents provide a response in their own words, or a closed-ended question, where they are asked to choose from a list of answer choices.

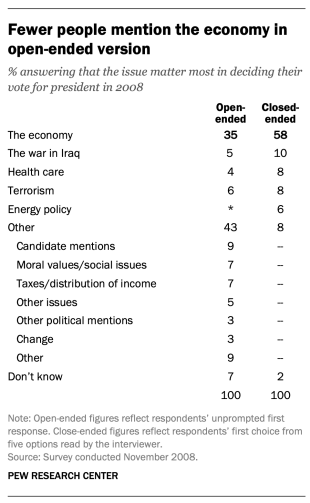

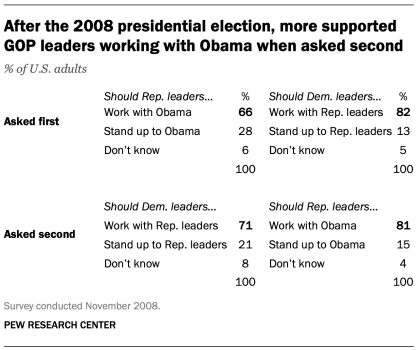

For example, in a poll conducted after the 2008 presidential election, people responded very differently to two versions of the question: “What one issue mattered most to you in deciding how you voted for president?” One was closed-ended and the other open-ended. In the closed-ended version, respondents were provided five options and could volunteer an option not on the list.

When explicitly offered the economy as a response, more than half of respondents (58%) chose this answer; only 35% of those who responded to the open-ended version volunteered the economy. Moreover, among those asked the closed-ended version, fewer than one-in-ten (8%) provided a response other than the five they were read. By contrast, fully 43% of those asked the open-ended version provided a response not listed in the closed-ended version of the question. All of the other issues were chosen at least slightly more often when explicitly offered in the closed-ended version than in the open-ended version. (Also see “High Marks for the Campaign, a High Bar for Obama” for more information.)

Researchers will sometimes conduct a pilot study using open-ended questions to discover which answers are most common. They will then develop closed-ended questions based off that pilot study that include the most common responses as answer choices. In this way, the questions may better reflect what the public is thinking, how they view a particular issue, or bring certain issues to light that the researchers may not have been aware of.

When asking closed-ended questions, the choice of options provided, how each option is described, the number of response options offered, and the order in which options are read can all influence how people respond. One example of the impact of how categories are defined can be found in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in January 2002. When half of the sample was asked whether it was “more important for President Bush to focus on domestic policy or foreign policy,” 52% chose domestic policy while only 34% said foreign policy. When the category “foreign policy” was narrowed to a specific aspect – “the war on terrorism” – far more people chose it; only 33% chose domestic policy while 52% chose the war on terrorism.

In most circumstances, the number of answer choices should be kept to a relatively small number – just four or perhaps five at most – especially in telephone surveys. Psychological research indicates that people have a hard time keeping more than this number of choices in mind at one time. When the question is asking about an objective fact and/or demographics, such as the religious affiliation of the respondent, more categories can be used. In fact, they are encouraged to ensure inclusivity. For example, Pew Research Center’s standard religion questions include more than 12 different categories, beginning with the most common affiliations (Protestant and Catholic). Most respondents have no trouble with this question because they can expect to see their religious group within that list in a self-administered survey.

In addition to the number and choice of response options offered, the order of answer categories can influence how people respond to closed-ended questions. Research suggests that in telephone surveys respondents more frequently choose items heard later in a list (a “recency effect”), and in self-administered surveys, they tend to choose items at the top of the list (a “primacy” effect).

Because of concerns about the effects of category order on responses to closed-ended questions, many sets of response options in Pew Research Center’s surveys are programmed to be randomized to ensure that the options are not asked in the same order for each respondent. Rotating or randomizing means that questions or items in a list are not asked in the same order to each respondent. Answers to questions are sometimes affected by questions that precede them. By presenting questions in a different order to each respondent, we ensure that each question gets asked in the same context as every other question the same number of times (e.g., first, last or any position in between). This does not eliminate the potential impact of previous questions on the current question, but it does ensure that this bias is spread randomly across all of the questions or items in the list. For instance, in the example discussed above about what issue mattered most in people’s vote, the order of the five issues in the closed-ended version of the question was randomized so that no one issue appeared early or late in the list for all respondents. Randomization of response items does not eliminate order effects, but it does ensure that this type of bias is spread randomly.

Questions with ordinal response categories – those with an underlying order (e.g., excellent, good, only fair, poor OR very favorable, mostly favorable, mostly unfavorable, very unfavorable) – are generally not randomized because the order of the categories conveys important information to help respondents answer the question. Generally, these types of scales should be presented in order so respondents can easily place their responses along the continuum, but the order can be reversed for some respondents. For example, in one of Pew Research Center’s questions about abortion, half of the sample is asked whether abortion should be “legal in all cases, legal in most cases, illegal in most cases, illegal in all cases,” while the other half of the sample is asked the same question with the response categories read in reverse order, starting with “illegal in all cases.” Again, reversing the order does not eliminate the recency effect but distributes it randomly across the population.

Question wording

The choice of words and phrases in a question is critical in expressing the meaning and intent of the question to the respondent and ensuring that all respondents interpret the question the same way. Even small wording differences can substantially affect the answers people provide.

[View more Methods 101 Videos ]

An example of a wording difference that had a significant impact on responses comes from a January 2003 Pew Research Center survey. When people were asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule,” 68% said they favored military action while 25% said they opposed military action. However, when asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule even if it meant that U.S. forces might suffer thousands of casualties, ” responses were dramatically different; only 43% said they favored military action, while 48% said they opposed it. The introduction of U.S. casualties altered the context of the question and influenced whether people favored or opposed military action in Iraq.