The Current State of Critical Thinking in EMS

Critical thinking is not something that one can just begin to do, writes Radu Venter It is a skill that must first be taught, developed over time and regularly maintained.

Emergency medical services (EMS) journals regularly discuss a lack of critical thinking evident in paramedics and how this deficiency is a significant flaw in the profession. Some provide tips and tricks to paramedics looking to develop their critical thinking. Others outline examples of mindsets to follow and biases to avoid. These articles stand by the need for further critical thinking training in EMS, but there are some significant absences that limit their ability to assist practitioners seeking to develop their skills.

Before continuing, we must ask whether critical thinking is a valuable skill for paramedics. Is there a benefit to having paramedics make decisions on their own? Should we instead have them strictly follow flowcharts in patient assessment, initial treatment and prompt transport to a hospital where a doctor can oversee definitive care? Alternately, do we want more basic practitioners to follow the flowcharts and those of higher levels to think critically?

- Critical Thinking, Part One

- Critical Thinking, Part Two

- EMS Providers Use Detective Skills to Solve Case

The current system is largely based on the third option. Paramedics working at advanced levels are expected to be able to critically think. Certain treatments available to these practitioners may be detrimental to the patient, so it falls on the practitioner to assess, reason and treat appropriately. Paramedics working at a more basic level do not have such expectations. Their training encompasses a more limited scope, prioritizing treatment of only more severe conditions. While critical thinking skills may be a goal of advanced care education, at the basic level, the goal is to create technicians. Technicians prioritize practical skills, with less focus on the theoretical. Thus, it is possible to educate a technician rapidly — basic life support programs are thus much shorter. As explained by Daniel Limmer in his EMS World article, “A technician is not expected to use high levels of reasoning skills. Technicians are strictly protocol driven and respond in a specific way when a certain group of signs and symptoms appear.” 1

Why, then, is there all this frustration with a lack of critical thinking in our profession, even with practitioners working at the basic level? The simplest answer is that when the practitioner aspires to the next level of training, critical thinking becomes more important. Unfortunately, to become an advanced level practitioner, the technician must then re-learn a fair amount of their practice. The second reason critical thinking is necessary for all paramedics has to do with the fluidity of patient assessment and treatment. Every skill performed requires an element of critical thinking. The practitioner must be able to select an appropriate diagnostic to perform or therapy to administer. They must then be able to verify the information received or confirm the therapy was effective. Kelly Grayson supports this point, noting that our current focus is more on what skills paramedics can perform, rather than the underlying knowledge necessary to determine when the skill is required and the ability to perform it proficiently. 2 A further avenue of exploration is whether the skill was even necessary in the first place.

Further, paramedics must be able to determine which algorithm for patient treatment will provide the greatest benefit. They must also be able to identify treatment priorities, and which hospital is most appropriate for transport. Finally, there is no effective flowchart for the patient who is suffering from a serious medical condition and wishes to stay at home. Paramedics of any ability level forced to operate in these novel situations without clear directions must then be able to think through the situation and work through the problem.

Two Elements of Critical Thinking

Current EMS articles on how to develop critical thinking fall into the trap of providing guidelines without going into enough depth. Scott Cormier’s two-part article on critical thinking provides a few examples of approaches to critical thinking as well as biases to avoid. 3,4 Unfortunately, they do not touch on the foundation of critical thinking, such as the traits of a good critical thinker, or provide examples to the reader to be able to apply these approaches in their own practice.

Others are more mechanical in nature than cognitive. In Daniel Limmer’s article, he states that practitioners should aspire to be clinicians instead of merely technicians. Where a technician identifies a symptom and works to treat it, a clinician strives to obtain a complete picture of the patient through a thorough assessment and the use of a differential diagnosis, prior to initiating a treatment. Performing thorough assessments of the patient, prioritizing focus on immediate threats to airway, breathing and circulation, and creating a differential diagnosis do not require as much critical thinking as might be expected.

I would suggest that a clinician’s approach has less to do with their ability to critically think, but more to do with thoroughness. In the example Limmer provides, the only difference between a technician and a clinician is the completion of a more thorough assessment that leads to a different diagnosis and, therefore, a different treatment plan. Though creating a differential diagnosis involves elements of critical thinking, it can also be a largely mechanical process — paramedics can easily memorize medical conditions to rule out in the case of a patient presenting with a specific complaint. Of the six steps suggested, only the last two involve critical thinking. Unfortunately, these are the shortest steps in the article. The best example I was able to discover is Rom Duckworth’s article, urging practitioners to assess sources of information for accuracy, validity, and a lack of bias, while also questioning currently-held beliefs. 5 This article focuses on the cognitive skills inherent in critical thinking, avoiding the mechanical pitfalls other articles fall into. However, like the other articles, it is very brief and does not provide examples for practitioners to either follow or practice.

The second major flaw underlying these articles is the assumption that the readers have enough background knowledge of the topic in order to be able to make critical decisions. For example, students in an advanced care paramedic class are asked to create a treatment plan for a cardiac complaint. The patient has sudden onset chest pain, radiating to the left arm, as well as significant pitting edema to upper and lower extremities. The patient also has a significant cardiac history. At the chest, wheezes are auscultated. Several students in the class treat the patient with salbutamol and ipratropium bromide, working to improve air entry and decrease wheezing through bronchodilation. A subsequent discussion introduced the existence of cardiac wheezes, caused not by bronchospasm, but by the presence of fluid in the lungs due to diminished cardiac output. The therapy selected by the students would be minimally effective at best, potentially detrimental to the patient at worst.

Reflecting on this experience, are the students at fault for not determining the patient’s wheezing to be cardiac in origin? Prior learning at the primary care paramedic level focused on treating wheezing as a symptom. Little focus was given to other potential causes of wheezing and treatment plans had a linear approach. Wheezing at that level is an automatic indication for nebulizer therapy.

The flaw lies not in a lack of critical thinking, because there was no room for the students to critically think. The assessment revealed wheezing, the students presumed that it was caused by bronchospasm, and then followed the appropriate protocol. The issue is that the students lacked enough background knowledge to understand the anatomy and physiology of the lungs and the pathophysiology of cardiac wheezing. A critical thinker with this background knowledge would have been able to determine the cause of the wheezing, weigh the benefits of available treatments and choose to initiate or withhold treatments based on the information given to them.

The Next Step

Critical thinking is not something that one can just begin to do. It is a skill that must first be taught, developed over time and regularly maintained. It is a combination of traits that one must possess and processes that must be developed and followed. A critical thinker must be sufficiently open-minded to other ideas and be willing to challenge current knowledge and experience.

This skill should be introduced at the earliest level possible, to benefit practitioners from the beginning of their career. Alongside critical thinking, a foundation of strong clinical knowledge must be present to allow for effective decisions to be made.

1. EMSWorld. Beyond the Basics: The Art of Critical Thinking Part 1 [Internet]. Emsworld.com; April 2008 [cited 2020 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.emsworld.com/article/10321160/beyond-basics-art-critical-thinking-part-1 .

2. EMS1. EMS 2.0: Critical Thinking in Prehospital Training [Internet] EMS1.com; Oct 2009 [cited 2020 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.ems1.com/ems-products/education/articles/ems-20-critical-thinking-in-prehospital-training-eCjskymt7gQYBFLe/ .

3. JEMS. Critical Thinking: Part 1 [Internet]. JEMS.com; May 2017 [cited 2020 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.jems.com/2017/05/15/critical-thinking-part-one/ .

4. JEMS. Critical Thinking: Part 2 [Internet]. JEMS.com; May 2017 [cited 2020 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.jems.com/2017/05/15/critical-thinking-part-two/ .

5. EMS1. 5 Critical Thinking Skills Crucial to EMS Professional Development [Internet]. EMS1.com; August 2017 [cited 2020 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.ems1.com/ems-management/articles/5-critical-thinking-skills-crucial-to-ems-professional-development-fQIz2bctBpYHktUP/ .

Related Posts

Latest Jems News

Advertisement

“Starting from a higher place”: linking Habermas to teaching and learning clinical reasoning in the emergency medicine context

- Published: 31 January 2020

- Volume 25 , pages 809–824, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Clare Delany ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6156-2347 1 ,

- Barbara Kameniar 2 , 3 ,

- Jayne Lysk 1 &

- Brett Vaughan 1

1159 Accesses

2 Citations

9 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Teaching clinical reasoning in emergency medicine requires educators to foster diagnostic accuracy and judicious decision-making amidst chaotic ambient factors including clinician fatigue, high cognitive load, and diverse patient expectations. The current study applies the early work of Jurgen Habermas and his knowledge-constitutive interests as a lens to explore an educational approach where physician-educators were asked to make their expert reasoning visible to emergency medicine trainees, to more deliberately make visible and accessible the context-specific thinking that emergency physicians routinely use. An action research methodology was used. The ‘making thinking visible’ teaching approach was introduced to five emergency medicine educators working in large public hospital emergency departments. Participants were asked to trial this teaching method and document its impact on student learning over two reporting cycles. Based on written reports of trialing the teaching approach, participants identified a need to change from: (1) introducing thinking structures to cultivating enquiry; and, (2) providing explanations based on cognitive thinking routines towards encouraging the learner to see the relevance of the clinical context. Educators described how they developed a more diagnostic and reflexive approach to learners, recognized the need to cultivate independent thinking, and valued the opportunity to reflect on their usual teaching. Teaching clinical reasoning using the ‘making thinking visible’ approach prompted educators to decrease the emphasis on providing technical information to assisting learners to understand the purposes and meanings behind clinical reasoning in emergency medicine. The knowledge-constitutive interests work of Jurgen Habermas was found to provide a robust framework supporting this emancipatory teaching approach.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The development of clinical thinking in trainee physicians: the educator perspective

Rachel Locke, Alice Mason, … Mike G. Masding

Learning clinical reasoning in the workplace: a student perspective

Larissa IA Ruczynski, Marjolein HJ van de Pol, … Cornelia RMG Fluit

Constructing critical thinking in health professional education

Renate Kahlke & Kevin Eva

Ackerman, S. L., Boscardin, C., Karliner, L., Handley, M. A., Cheng, S., et al. (2016). The action research program: Experiential learning in systems-based practice for first-year medical students. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 28 , 183–191.

Google Scholar

Adams, E., Goyder, C., Heneghan, C., Brand, L., & Ajjawi, R. (2016). Clinical reasoning of junior doctors in emergency medicine: A grounded theory study. Emergency Medicine Journal . https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2015-205650 .

Article Google Scholar

Angus, L., Chur-Hansen, A., & Duggan, P. (2018). A qualitative study of experienced clinical teachers' conceptualisation of clinical reasoning in medicine: Implications for medical education. Focus on Health Professional Education: A Multi-disciplinary Journal, 19 , 52.

Barnett, R. (2015). A curriculum for critical being. In M. Davies & R. Barnett (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of critical thinking in higher education. (pp. 63–76). Springer.

Barras, C. (2019). Training the physician of the future. Nature Medicine, 25 , 532–534. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0354-1 .

Bartlett, M., Gay, S. P., List, P. A., & McKinley, R. K. (2015). Teaching and learning clinical reasoning: Tutors’ perceptions of change in their own clinical practice. Education for Primary Care, 26 , 248–254.

Billett, S., & Pavlova, M. (2005). Learning through working life: Self and individuals’ agentic action. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 24 , 195–211.

Bohman, J., & Rehg, W. (1997). Deliberative democracy: Essays on reason and politics . London: MIT Press.

Breckwoldt, J., Ludwig, J. R., Plener, J., Schröder, T., Gruber, H., et al. (2016). Differences in procedural knowledge after a “spaced” and a “massed” version of an intensive course in emergency medicine, investigating a very short spacing interval. BMC Medical Education, 16 , 249.

Brown, J., Bearman, M., Kirby, C., Molloy, E., Colville, D., et al. (2019). Theory, a lost character? As presented in general practice education research papers. Medical Education . https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13793

Buber, M. (2003). Between man and man . New York: Routledge.

Chan, T., Mercuri, M., Van Dewark, K., Sherbino, J., Schwartz, A., et al. (2017). Managing multiplicity: Conceptualizing physician cognition in multi-patient environments. Academic Medicine, 93 , 786–793. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002081 .

Cianciolo, A. T., Eva, K. W., & Colliver, J. A. (2013). Theory development and application in medical education. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 25 , S75–S80.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (1998). Teacher research: The question that persists. International Journal of Leadership in Education Theory and Practice, 1 , 19–36.

Coghlan, D., & Casey, M. (2001). Action research from the inside: Issues and challenges in doing action research in your own hospital. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 35 , 674–682.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2002). Research methods in education . London: Routledge.

Croskerry, P. (2003). Cognitive forcing strategies in clinical decision making. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 41 , 110–120.

Croskerry, P., & Sinclair, D. (2001). Emergency medicine: A practice prone to error? Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 3 , 271–276.

Crow, J., Smith, L., & Keenan, I. (2006). Journeying between the Education and Hospital Zones in a collaborative action research project. Educational Action Research, 14 , 287–306.

Delany, C., & Golding, C. (2014). Teaching clinical reasoning by making thinking visible: An action research project with allied health clinical educators. BMC Medical Education, 14 , 20.

Delany, C., Golding, C., & Bialocerkowski, A. (2013). Teaching for thinking in clinical education: Making explicit the thinking involved in allied health clinical reasoning. Focus on Health Professional Education: A Multi-disciplinary Journal, 14 , 44.

Dumas, D., Torre, D. M., & Durning, S. (2018). Using relational reasoning strategies to help improve clinical reasoning practice. Academic Medicine, 93 , 709–714. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002114 .

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62 , 107–115.

Farrell, L., Bourgeois-Law, G., Ajjawi, R., & Regehr, G. (2017). An autoethnographic exploration of the use of goal oriented feedback to enhance brief clinical teaching encounters. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 22 , 91–104.

Frenk, J., Chen, L., Bhutta, Z. A., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., et al. (2010). Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lancet, 376 , 1923–1958.

Gay, S., Bartlett, M., & McKinley, R. (2013). Teaching clinical reasoning to medical students. The Clinical Teacher, 10 , 308–312.

Ghanizadeh, A. (2017). The interplay between reflective thinking, critical thinking, self-monitoring, and academic achievement in higher education. Higher Education, 74 , 101–114.

Gimpel, N., Kindratt, T., Dawson, A., & Pagels, P. (2018). Community action research track: Community-based participatory research and service-learning experiences for medical students. Perspectives on Medical Education, 7 , 139–143.

Golding, C. (2011). Educating for critical thinking: Thought-encouraging questions in a community of inquiry. Higher Education Research & Development, 30 , 357–370.

Groundwater-Smith, S., Mitchell, J., & Mockler, N. (2016). Praxis and the language of improvement: Inquiry-based approaches to authentic improvement in Australasian schools. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 27 , 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.975137 .

Grundy, S. (1987). Critical pedagogy and the control of professional knowledge. The Australian Journal of Education Studies, 7 , 21–36.

Habermas, J. (2015). Knowledge and human interests. New York: Wiley

Heath, T. (1990). Education for the professions: Contemplations and reflections. Higher education in the late twentieth century: Reflections on a changing system . University of Queensland: Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australia.

Higgs, J., Jones, M., Loftus, S., & Christensen, N. (2018). Clinical reasoning in the health professions. Elsevier Health Sciences

Houchens, N., Harrod, M., Fowler, K. E., Moody, S. & Saint, S. (2017). How exemplary inpatient teaching physicians foster clinical reasoning. American Journal of Medicine, 130 , 1113. e1–1113. e8.

Humbert, A. J., Besinger, B., & Miech, E. J. (2011). Assessing clinical reasoning skills in scenarios of uncertainty: Convergent validity for a script concordance test in an emergency medicine clerkship and residency. Academic Emergency Medicine, 18 , 627–634.

Kameniar, B., Davies, L. M., Kinsman, J., Reid, C., Tyler, D., et al. (2017). Clinical praxis exams: Linking academic study with professional practice knowledge. A Companion to Research in Teacher Education (pp. 53–67). New York: Springer.

Kaufman, D. M., & Mann, K. V. (2014). Teaching and learning in medical education: how theory can inform practice. Understanding medical education: Evidence, theory and practice (pp. 7–30). West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Kovacs, G., & Croskerry, P. (1999). Clinical decision making: An emergency medicine perspective. Academic Emergency Medicine, 6 , 947–952.

Kumagai, A. K. (2014). From competencies to human interests: Ways of knowing and understanding in medical education. Academic Medicine, 89 , 978–983.

Laidley, T. L., & Braddock, C. H. (2000). Role of adult learning theory in evaluating and designing strategies for teaching residents in ambulatory settings. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 5 , 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009863211233 .

Mann, K., Gordon, J., & MacLeod, A. (2009). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 14 , 595.

McNiff, J., & Whitehead, J. (2011). All you need to know about action research . London: Sage Publications.

Michaels, S., O’Connor, C., & Resnick, L. B. (2008). Deliberative discourse idealized and realized: Accountable talk in the classroom and in civic life. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 27 , 283–297.

Monrouxe, L. V. (2010). Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Medical Education, 44 , 40–49.

Monteiro, S. M., & Norman, G. (2013). Diagnostic reasoning: Where we've been, where we’re going. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 25 , S26–S32.

Morse, J. M., & Singleton, J. (2001). Exploring the technical aspects of “fit” in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 11 , 841–847.

Padela, A. I., Davis, J., Hall, S., Dorey, A., & Asher, S. (2018). Are emergency medicine residents prepared to meet the ethical challenges of clinical practice? Findings from an exploratory national survey. AEM Education and Training, 2 , 301–309.

Pelaccia, T., Tardif, J., Triby, E., Ammirati, C., Bertrand, C., et al. (2014). How and when do expert emergency physicians generate and evaluate diagnostic hypotheses? A qualitative study using head-mounted video cued-recall interviews. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 64 , 575–585.

Pinnock, R., Young, L., Spence, F., Henning, M., & Hazell, W. (2015). Can think aloud be used to teach and assess clinical reasoning in graduate medical education? Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 7 , 334–337.

Pinnock, R., Fisher, T. L., & Astley, J. (2016). Think aloud to learn and assess clinical reasoning. Medical Education, 50 , 585–586.

Pinnock, R., Anakin, M., Lawrence, J., Chignell, H., & Wilkinson, T. (2019). Identifying developmental features in students’ clinical reasoning to inform teaching. Medical Teacher, 41 , 297–302.

Rees, C. E., & Monrouxe, L. V. (2010). Theory in medical education research: how do we get there? Medical Education, 44 , 334–339.

Ritchhart, R., & Perkins, D. N. (Eds.). (2005). Learning to think: The challenges of teaching thinking . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sadler, D. R. (2010). Beyond feedback: Developing student capability in complex appraisal. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35 , 535–550.

Schon, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner . New York: Basic Books.

Stenfors-Hayes, T., Hult, H., & Dahlgren, L. O. (2011). What does it mean to be a good teacher and clinical supervisor in medical education? Advances in Health Sciences Education, 16 , 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9255-2 .

Trede, F., & Higgs, J. (2009). Models and philosophy of practice. In J. Higgs, M. Smith, G. Webb, M. Skinner, & A. Croker (Eds.), Contexts of physiotherapy practice (pp. 90–101). Chatswood: Elsevier.

Trevitt, C. (2008). Learning in academia is more than academic learning: Action research in academic practice for and with medical academics. Educational Action Research, 16 , 495–515.

University Grants Committee. (1964). Report of the committee on university teaching methods (Hale Committee) . London: HMSO.

Walker, P., & Lovat, T. (2015). Applying Habermasian "ways of knowing" to medical education. Journal of Contemporary Medical Education, 3 , 123–126. https://doi.org/10.5455/jcme.20151102103550 .

Whipp, J. (2000). Rethinking knowledge and pedagogy in dental education. Journal of Dental Education, 64 , 860–866.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the participating educators for generously giving their time and for their enthusiastic participation.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medical Education, University of Melbourne, Grattan Street,, Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, 3010, Australia

Clare Delany, Jayne Lysk & Brett Vaughan

Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

Barbara Kameniar

Faculty of Education, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Clare Delany .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval was been granted by the University of Melbourne, Department of Medical Education Human Ethics Advisory Group (1137166.1).

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Delany, C., Kameniar, B., Lysk, J. et al. “Starting from a higher place”: linking Habermas to teaching and learning clinical reasoning in the emergency medicine context. Adv in Health Sci Educ 25 , 809–824 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-09958-x

Download citation

Received : 18 June 2019

Accepted : 14 January 2020

Published : 31 January 2020

Issue Date : October 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-09958-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Clinical reasoning

- Education theory

- Emancipation

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Educational advances in emergency medicine

- Open access

- Published: 16 April 2020

How to think like an emergency care provider: a conceptual mental model for decision making in emergency care

- Nasser Hammad Al-Azri 1

International Journal of Emergency Medicine volume 13 , Article number: 17 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

12 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

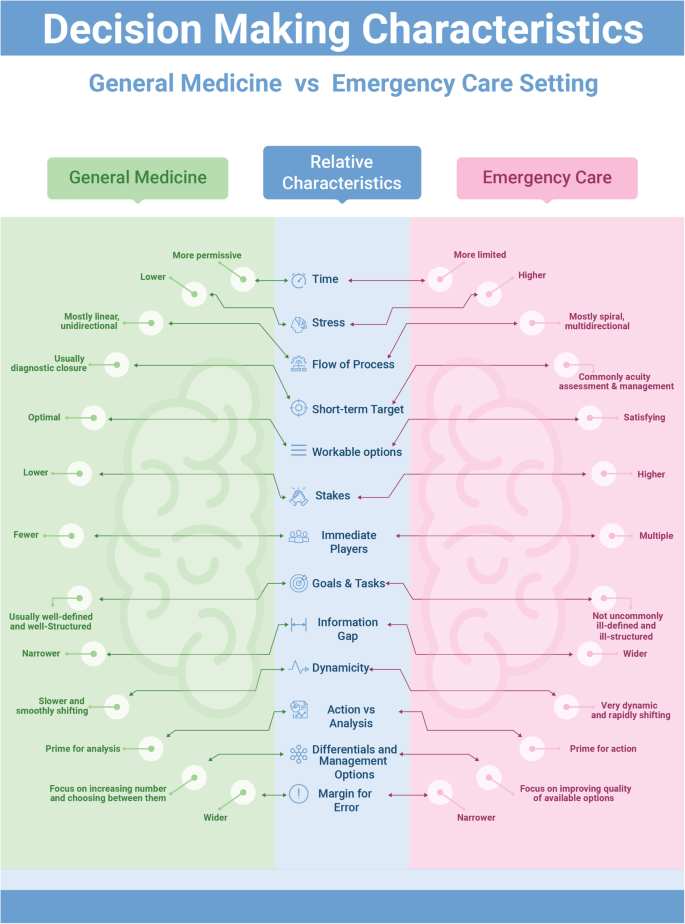

General medicine commonly adopts a strategy based on the analytic approach utilizing the hypothetico-deductive method. Medical emergency care and education have been following similarly the same approach. However, the unique milieu and task complexity in emergency care settings pose a challenge to the analytic approach, particularly when confronted with a critically ill patient who requires immediate action. Despite having discussions in the literature addressing the unique characteristics of medical emergency care settings, there has been hardly any alternative structured mental model proposed to overcome those challenges.

This paper attempts to address a conceptual mental model for emergency care that combines both analytic as well as non-analytic methods in decision making.

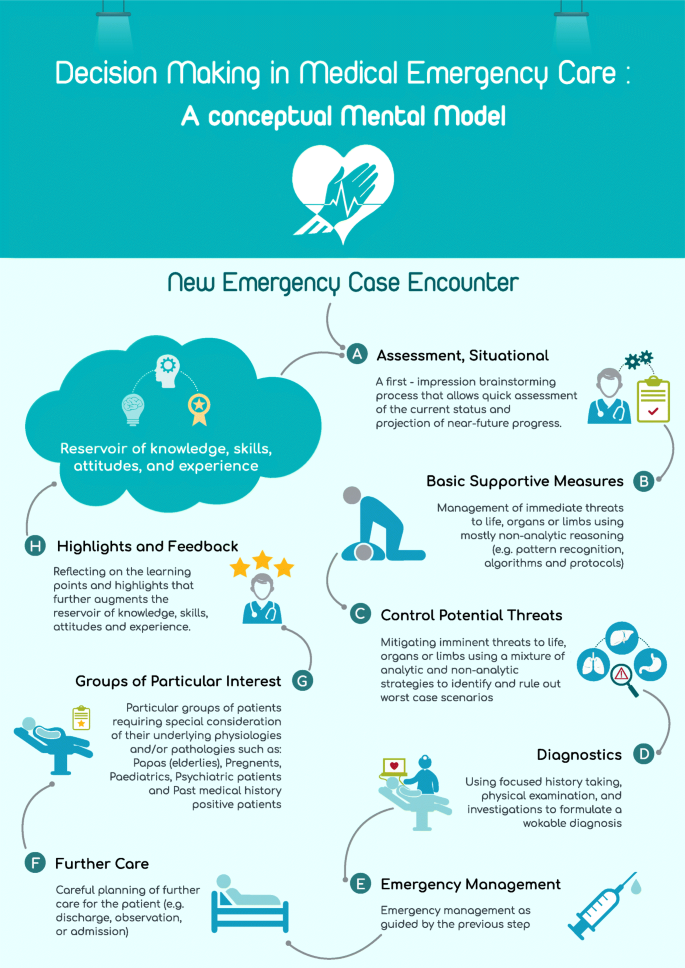

The proposed model is organized in an alphabetical mnemonic, A–H. The proposed model includes eight steps for approaching emergency cases, viz., awareness, basic supportive measures, control of potential threats, diagnostics, emergency care, follow-up, groups of particular interest, and highlights. These steps might be utilized to organize and prioritize the management of emergency patients.

Metacognition is very important to develop practicable mental models in practice. The proposed model is flexible and takes into consideration the dynamicity of emergency cases. It also combines both analytic and non-analytic skills in medical education and practice.

Combining various clinical reasoning provides better opportunity, particularly for trainees and novices, to develop their experience and learn new skills. This mental model could be also of help for seasoned practitioners in their teaching, audits, and review of emergency cases.

“It is one thing to practice medicine in an emergency department; it is quite another to practice emergency medicine. The effective practice of emergency medicine requires an approach, a way of thinking that differs from other medical specialties” [ 1 ]. Yet, common teaching trains future emergency practitioners to “practice medicine in an emergency department.”

Emergency care is a complex activity. Emergency practitioners are like circus performers who have to “spin stacks of plates, one on top of another, of all different shapes and weights” [ 2 ]. This can be further complicated by simultaneous demands from various and multiple stakeholders such as administrators, patients, and colleagues. Add to that the time-bound interventions and parallel tasks required and it can be thought of no less than being chaotic.

There is a tendency to distinguish emergency care from other medical practices as being more action-driven than thought-oriented [ 3 ]. This probably stems from the presumption that emergency medicine follows the same strategy as other medical disciplines so it is judged within the same parameters. Another explanation for this is that emergency practitioners are seen to act immediately on their patients when other medical specialties might take longer time preparing for this action. However, the chaotic environment is different and it requires complex decision-making skills and strategies. Unlike general medical settings, in EM, often a history is unobtainable, and a physical examination and medical investigations are not readily available in a critically ill patient. Despite this, emergency medicine is still being taught using the conceptual model of general medicine that follows an information-gathering approach seeking optimal decision-making. In medical decision-making, the commonly adopted hypothetico-deductive method involving history taking, physical examination, and investigations corresponds to the general approach of medicine.

Importance of rethinking existing medical emergency care mental model

Education in medical emergency care adopts a strategy similar to that of general medicine despite the fact that it is not optimal in emergency departments. Emergency care providers cannot anticipate what condition their patients will be in and they cannot follow the steps of detailed history taking, complete physical examination, ordering required investigations, and, using the results, plan the management of their patient. Classical clinical decision theory may not fit dynamic environments like emergency care. Patients in the emergency department are usually critical, time is limited, and information is scarce or even absent, and decisions are still urgently required.

Croskerry (2002) has noted: “In few other workplace settings, and in no other area of medicine, is decision density as high” [ 4 ] as in emergency medicine. In an area where an information gap can be found in one third of emergency department visits, and more so in critical cases [ 5 ], an information-seeking strategy is unlikely to succeed. Moreover, diagnostic closure is usually the short-term target in the hypothetico-deductive method while this is less of a concern in emergency care. Instead, the short-term priorities in emergency care include assessment of acuity and life-saving [ 6 ]. Figure 1 presents a comparison of the conventional general medicine decision-making approach and how emergency care setting differs relatively with regard to those basic characteristics.

Comparing conventional decision-making in general medicine vs. emergency care setting

Hence, a different mental model with a distinctive approach for emergency care is required. Mental models are important to describe, explain, and predict situations [ 7 ]. This is the roadmap through the wilderness of emergency care rather than a guide on driving techniques. Experts are differentiated from novices in several aspects: sorting and categorizing problems, using different reasoning processes, developing mental models, and organizing content knowledge better [ 8 ]. In addition, experienced physicians form more rapid, higher quality working hypotheses and plans of management than novices do. Novices are especially challenged in this area, since teaching general problem solving was replaced with problem-based learning, as the emphasis shifted toward “helping students acquire a functional organization of content with clinically usable schemas” [ 9 ]. The proposed model is intended to better organize the knowledge and approach required in emergency care, which may eventually help improve the practice, particularly of novices.

Clinical decision-making in emergency care requires a unique approach that is sensitive to the distinctive milieu where emergency care takes place [ 10 ]. Xiao et al. (1996) have identified four components of task complexity in emergency medical care [ 11 ]. These include multiple and concurrent tasks, uncertainty, changing plans of management, and compressed work procedures with high workload. Such complex components require an approach that accommodates such factors and balances the various needs in a timely and priority-based, situationally adaptable methodology.

A different model for emergency care

This article addresses a general mental approach involving eight steps arranged with an initialism mnemonic, A–H. Figure 2 presents an infographic of the lifecycle of this A–H decision-making process. These steps represent the lifecycle of decision-making in emergency practice and form the core of the proposed conceptual model. Every emergency care encounter starts with the first step of situational awareness (A) where the provider starts to build up a workable mental template of the case presentation. This process is ongoing throughout the encounter to reflect the dynamic nature of emergency cases. The second to fourth steps (B–D) involve a triaging process in order to prioritize the most appropriate management at that point in time, through a series of risk-stratification stages. Then, additional emergency management (E) follows based on the flow of the case from earlier steps. Following emergency management, a planning step regarding further care (F) for the patient is required. The following step concerns emergency patients who may represent special high risk groups (G) with special precautions and particular diagnostic and management approaches to be considered. This step is, in fact, a mandate throughout the process but included here as a reminder. The final step is a reflection of the entire process that highlights (H) the learning aspects from the case management. Throughout the process, the first and last steps are ongoing as they reflect the dynamicity of the situation.

Situational decision-making model lifecycle

A: (awareness, situational)

It is likely that the first thought of an emergency care provider, when confronted with an acutely ill patient, is the issue of time: “how much time do I have to act and how much time do I have to think?” [ 12 ]. The mental brainstorming that takes place in a matter of seconds is a very valuable and indispensable part of every single emergency encounter. Providers’ prior beliefs, expectations, emotions, knowledge, skills, and experience all contribute to the initial approach adopted. Individuals vary in the importance they attach to different factors [ 13 ], and this variation is reflected in the decisions they make. The importance of this mental process is, unfortunately, not reflected in either general medicine or emergency medicine education and research. Traditionally, “medical education has focused on the content rather than the process of clinical decision making” [ 6 ].

The notion of “situational awareness” (SA) is a useful concept to borrow from aviation sciences. Situational awareness has been defined as the individual’s “perception of the elements of the environment within a volume of time and space, the comprehension of their meaning and the projection of their status in the near future” [ 14 ]. As noted from the definition, SA tries to amalgamate the experiences and background of the practitioner with the current situation in order to enable a more educated prediction of what will happen next. Although the concept originated outside of the medical field, it has already been utilized in several medical disciplines including surgery, anesthesiology, as well as quality care, and patient safety [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Moreover, SA has been discussed in several emergency care mandates and it is recommended for inclusion in the non-technical skills training of teams in acute medicine [ 15 ].

This emphasizes that an attentiveness to the dynamic nature of priorities in emergency management is as important as knowledge and skills. As such, SA provides a mental model that encourages emergency care practitioners to stay alert for changes in the surrounding environment and relate those changes to case management. The importance of this step in the model is that it prods us to go beyond our immediate perceptions and gut feelings and develop an overall view of the situation [ 18 ]. Practically, decision-making in emergency care has historically depended more on rapid situational assessment rather than optimal decision-making strategies as in the hypothetico-deductive method [ 19 ]. SA is probably one of the most neglected, yet distinguishing, skills in emergency medicine education.

B: (basic life, organ, and limb supportive measures)

The second step in emergency decision-making involves a clinical triaging process. The purpose of this triage is to prioritize time-bound interventions or treatment for the patient. Immediate risks to life, organs, or limbs take priority in case management. This precedes any analytical thinking provided by detailed history taking, physical examination, or investigations, even though a focused approach might be necessary. This step maintains the dynamicity of the process of decision-making and allows the practitioner a holistic view of available and appropriate options rather than ordinary linear thinking. It also provides flexibility of movement between treatment options in response to dynamic changes in the condition.

Life-threatening conditions always take precedence in emergency management. The next priority is to manage immediate risks to body organs or limbs; this is the essence of medical emergency management. Therefore, the aim of this step on basic supportive action (B) is to save the vitals of the patient. This is where advanced cardiac and trauma life support algorithms and emergency management protocols are important.

A useful approach at this step is pattern recognition. In real practice, when confronted with a critically ill or crashing patient, the emergency care provider usually abandons the time-consuming hypothetico-deductive method; pattern recognition offers a rapid assessment and clinical plan that permits immediate life-, organ-, or limb-saving measures to take place [ 20 ]. Pattern recognition, known also as non-analytic reasoning, is a central feature of the expert medical practitioner’s ability to rapidly diagnose and respond appropriately, compared to novices who struggle with linear thinking skills [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]. This approach could be further augmented by the availability of algorithms and protocols that allow immediacy of perception and initiation of management [ 4 ], as well as by including it in clinical teaching and education.

C: (control potential life, organ, and limb threats)

While emergency care providers must prioritize immediate threats to life, organs, and limbs, they must also anticipate and recognize imminent threats to the same and control them (C). This is one of the biggest challenges in emergency care compared to other medical settings; oftentimes, the grey cases are the hidden tigers. In fact, seasoned emergency care providers know that even the most unremarkable patients may have a catastrophic outcome within moments [ 24 ]. Emergency care providers usually adopt mental templates for the top diagnoses that they need to exclude for every particular presentation. This is a step of “ruling out” worst diagnoses before proceeding. Croskerry (2002) asserts that this “rule out the worst case” strategy is almost pathognomonic of decision-making in the emergency department [ 4 ]. Many emergency presentations (e.g., poisoning, head injury, and chest pain) are true time bombs that any emergency care provider should be alert to.

This step presents an intermediate stage between the previous step (B) where pattern recognition and non-analytic reasoning dominates decision-making, and the next step (D) where the hypothetico-deductive approach with its analytic reasoning starts to play a major role in decision-making. As such, this step utilizes a mixture of the analytic and non-analytic reasoning to aid emergency care practitioners the “rule out the worst case” scenario in their patients. Examples of presentation-wise “worst case” scenarios are illustrated in Table 1 .

Once a potential threat is discovered, the practitioner will be situationally more aware and this will help to initiate measures that could prevent further deterioration of the condition. Again, this step is another that is practiced commonly by expert practitioners but is presented informally or insufficiently in emergency medicine training or education. Emergency care practitioners should focus more on this step due to its centrality in emergency care practice as well as its importance for ensuring safety of patients.

D: (diagnostics)

Once immediate and/ or imminent threats have either been excluded or managed, the emergency care provider may move on to the next step of formulating a workable clinical diagnosis (D) through the commonly adopted hypothetico-deductive medical model via a focused history taking, physical examination, and investigations. This is basically what all medical students are trained for in their undergraduate and postgraduate medical education. This step involves the utilization of existing tools for optimal decision-making within the available resources in the emergency department. Nevertheless, a final diagnosis may not be reachable in the emergency department setting.

E: (emergency management)

This is the step that naturally follows the diagnostic step (D). After collecting appropriate information regarding patient presentation through a focused history, examination and investigations, the emergency care provider may start emergency management and treatment as indicated. This does not contradict utilizing appropriate interventions in earlier steps (B, C) that aim to save life, organs, or limbs.

F: (further care)

While decisions about intervention(s) in emergency care are very difficult, often decisions about the further management of the patient are just as difficult [ 25 ]. Grey cases present the dilemma of whether to admit, keep for observation, or discharge. This decision is problematic because it entails not only technical aspects of the clinical status of the patient but also social, political, economic, and administrative factors along with the availability of supportive resources.

The initial brainstorm regarding imminent threats to life, organs, and limbs (C) continues to play a major role in the emergency provider’s decision-making. Discharging patients to their home carries risks related to a lack of clinical care and formal monitoring compared to admitted patients [ 26 ]. Hence, this step is pivotal in the emergency care of patients with significant implications in terms of outcome. Incorporating this step in the model is essential for the emergency care provider to have an integrative and holistic view of the case.

G: (groups of particular interest)

Certain groups of patients warrant particular concern while being managed in emergency care settings [ 27 ]. There are different reasons to consider these groups as high risk. Often, it is because they have underlying pathologies and/or physiologies that make them more prone for complications, acute exacerbations, and/or they are less likely to withstand the stress of acute illness. These groups include the elderly, pregnant women, children, psychiatric patients, and patients with a significant past medical history. These patients should cause particular concern that may justify a different and/or altered path of management at any step during the emergency care process.

H: (highlights)

Lack of informative feedback is one of the major drawbacks in emergency medicine that hinders learning and maintaining of cognitive and practical emergency care skills [ 28 ]. Feedback and highlighting of learning points is a crucial step in medical education and can be done in a variety of methods [ 29 ]. This is an ongoing step that starts at the case encounter and never ends during a practitioner’s career. Here, the practitioner reflects on the care and management provided during the encounter and makes a case for learning and advancing his knowledge, skills, and attitudes in emergency care. This step is usually done unconsciously. However, exposing this process to scrutiny and making it a formal step in the process of emergency care is likely to enhance experiential learning of the provider and, more importantly, offer feedback for the first step in the model that further augments situational awareness (A). This will add to the reservoir of understanding and attentiveness for future cases.

Thinking about thinking, also called metacognition, in emergency care is likely to reveal the strengths and weaknesses in current approaches and open doors for further development and improvement of emergency care. It is also likely to aid in recognizing opportunities for interventional thinking strategies [ 18 ]. This could be a step forward in preparing a broad-based, critical thinking pattern for physicians, who may save lives, organs, and limbs based on undifferentiated cases without having to depend on a diagnosis to do so.

The presented conceptual model attempts to contribute to the exposition and development of the forgotten skill of clinical reasoning with a particular reference to emergency and acute care. Moreover, it dissects the usually overlooked process of decision-making in emergency care [ 28 ]. The arrangement of the model components in alphabetical mnemonics may act as a reminder of a decision process that will reduce omission errors in clinical settings. Furthermore, functional categorization of the steps involved in decision-making, as well as in actual practice, will provide and develop further insight and awareness of cognitive strengths and weaknesses at different stages.

A significant advantage of the proposed conceptual mental model for emergency care is that it combines both analytic as well as non-analytic (also called naturalistic decision-making, NDM) strategies to aid medical emergency management. This model does not eliminate the need for the hypothetico-deductive analytic method but rather incorporates it within a more comprehensive approach and utilizes it when it is situationally appropriate along with the non-analytic method (Fig. 3 ). Combining different clinical reasoning strategies helps novice practitioners have greater diagnostic accuracy, improve performance, and avoid giving misleading information [ 30 , 31 ].

Situationally combined analytical and non-analytical decision-making methods

In addition, emergency care has been described as chaotic. Chaotic contexts are characterized by dominance of the unknowables, indeterminate relationships between the cause and effect, and a lack of existing manageable patterns [ 32 ]. In such contexts, the best approach to management is to act to establish order, then sense where stability is present and where it is not, and then respond to transform the situation from chaos to complexity [ 32 ]. The described model addresses those activities in order where the emergency care provider first acts (B), then senses (C), and finally responds (D, E) to establish a more stable context.

The suggested approach can be utilized by various groups of practitioners, such as physicians, nurses, and paramedics, hence the use of the term emergency care. Moreover, novices and trainees learn better by being exposed to the decision-making process involved, rather than just mimicking the actions of experts [ 3 ].

Medical education is required to produce a “broad-based physician, geared to solving undifferentiated clinical problems” [ 33 ]. Emergency medicine, as a generalist discipline, has probably high potential for that. The presented model could be used in several contexts. It could be used as a mental model that guides the practice of emergency care for novice practitioners or it could be used as a teaching tool for medical students and trainees, in not only emergency care, but also other specialties that may have exposure to emergency cases. In addition to novice providers, it has implications for physicians in emergency departments, paramedics in emergency medical services, general practitioners in rural clinics, nurse practitioners, or anyone else practicing emergency care. This may lead to the development of training and educational methods that suit each stage separately, as well as recognizing cognitive biases and avoiding them.

The model may also be used for audits and reviews of emergency case management, including self-audits, departmental or institutional audits, or peer reviews. Moreover, clinical decision-making aids could be further developed and tailored to the needs of the practice. For example, algorithms and pattern recognition are suitable for steps B and C teaching and decision-making, while event-driven and hypothetico-deductive approaches are more suitable for step D. This model is very broad-based. It is hoped that this conceptual model will help practitioners develop a more focused approach, a broader perspective, and a better ability to detect critical signals when managing undifferentiated emergency cases.

Availability of data and materials

Wears RL. Introduction: the approach to the emergency department patient. In: Wolfson AB, Hendey GW, Hendry PL, et. al. (eds). Harwood-Nuss’ Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. 4th edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005.

Groopman J. How doctors think. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company; 2007.

Google Scholar

Geary U, Kennedy U. Clinical decision making in emergency medicine. Emergencias. 2010;22:56–60.

Croskerry P. Achieving quality in clinical decision making: cognitive strategies and detection of bias. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(11):1184–204.

Article Google Scholar

Stiell A, Forster AJ, Stiell IG, et al. Prevalence of information gaps in the emergency department and the effect on patient outcomes. CMAJ. 2003;169(10):1023–8.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kovacs G, Croskerry P. Clinical decision making: an emergency medicine perspective. Acad Emergency Med. 1999;6(9):947–52.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Burns K. Mental models and normal errors. In: Montgomery H, Lipshitz R, Brehmer B, editors. How Professionals Make Decisions. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005.

Gambrill E. Critical Thinking in clinical practice: improving the quality of judgments and decisions. 2nd ed. New Jersey: Wiley & Sons; 2005.

Elstein AS, Schwarz A. Clinical problem solving and diagnostic decision making: selective review of the cognitive literature. BMJ. 2002;324:729–32.

Croskerry P. Critical thinking and decisionmaking: avoiding the perils of thin-slicing. Ann Emergency Med. 2006;48(6):720–2.

Xiao Y, Hunter WA, Mackenzie CF, Jefferies NJ. Task complexity in emergency medical care and its implications for team coordination. Hum Factors. 1996;38(4):636–45.

Dailey RH. Approach to the patient in the emergency department. In: Rosen P, editor. Emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice. St. Louis: Mosby; 2010. p. 137–50.

Lockey AS, Hardern RD. Decision making by emergency physicians when assessing cardiac arrest patients on arrival to hospital. Resuscitation. 2001;50(1):51–6.

Endsley MR. Design and evaluation for situation awareness enhancement. In: Proceedings of the Human Factors Society 32 nd Annual Meeting. Santa Monica, CA: Human factors Society; 1998. p. 97–101.

Flin R, Maran N. Identifying and training non-technical skills for teams in acute medicine. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(Suppl 1):i80–4.

McIlvaine WB. Situational awareness in the operating room: a primer for the anesthesiologist. Seminars Anesthesia Perioperative Med Pain. 2007;26:167–72.

Wright MC, Taekman JM, Endsley MR. Objective measures of situation awareness in a simulated medical environment. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(Suppl 1):i65–71.

Croskerry P. Cognitive forcing strategies in clinical decisionmaking. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2003;41(1):110–20.

Bond S, Cooper S. Modelling emergency decisions: recognition-primed decision making. The literature in relation to an ophthalmic critical incident. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:1023–32.

Sandhu H, Carpenter C. Clinical decisionmaking: opening the black box of cognitive reasoning. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(6):713–9.

Norman G, Young M, Brooks L. Non-analytical models of clinical reasoning: the role of experience. Med Edu. 2007;41(12):1140–5.

Sklar DP, Hauswald M, Johnson DR. Medical problem solving and uncertainty in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(9):987–91.

Szolovits P, Pauker S. Categorical and probabilistic reasoning in medical diagnosis. Artif Intell. 1978;11:115–44.

Mattu A, Goyal D. Emergency medicine: avoiding the pitfalls and improving the outcomes. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing; 2007.

Book Google Scholar

Frank LR, Jobe KA. Admission & discharge decisions in emergency medicine . Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus; 2001.

Croskerry P, Campbell S, Forster AJ. Discharging safely from the emergency department. In Croskerry P. Patient safety in emergency medicine . Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2009.

Garmel GM. Approach to the emergency patient. In: Mahadevan SV, Garmel GM, editors. An introduction to clinical emergency medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Croskerry P, Sinclair D. Emergency medicine: a practice prone to error? CJEM. 2001;3(4):271–6.

Wald DA, Choo EK. Providing feedback in the emergency department. In: Rogers RL, Mattu A, Winters M, Martinez J, editors. Practical teaching in emergency medicine. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. p. 60–71.

Chapter Google Scholar

Ark TK, Brooks LR, Eva KW. Giving learners the best of both worlds: do clinical teachers need to guard against teaching pattern recognition to novices? Acad Med. 2006;81(4):405–9.

Eva KW, Hatala RM, Leblanc VR, et al. Teaching from the clinical reasoning literature: combined reasoning strategies help novice diagnosticians overcome misleading information. Med Educ. 2007;41(12):1152–8.

Snowden DJ, Boone ME. A leader’s framework for decision making. Harv Bus Rev. 2007;85(1):68–76.

PubMed Google Scholar

Burdick WP. Emergency medicine’s role in the education of medical students: directions for change. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(6):688–91.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Nil declared

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Emergency Department, Ibri Hospital, Ministry of Health, POB 134, 516 Akhdar, Ibri, Oman

Nasser Hammad Al-Azri

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Solo author. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nasser Hammad Al-Azri .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Solo author

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Al-Azri, N.H. How to think like an emergency care provider: a conceptual mental model for decision making in emergency care. Int J Emerg Med 13 , 17 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-020-00274-0

Download citation

Received : 05 December 2019

Accepted : 25 March 2020

Published : 16 April 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-020-00274-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Decision-making

- Emergency care

- Emergency medicine

- Mental model

- Situational model

International Journal of Emergency Medicine

ISSN: 1865-1380

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Critical thinking, curiosity and parsimony in (emergency) medicine: 'Doing nothing' as a quality measure?

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Emergency Medicine, Gold Coast University Hospital, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia.

- 2 Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia.

- 3 School of Medicine, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia.

- PMID: 28452114

- DOI: 10.1111/1742-6723.12782

Current medical decision-making is influenced by many factors, such as competing interests, distractions, as well as fear of missing an important diagnosis. This can result in ordering tests or providing treatments that can be harmful. Unnecessary tests are more likely to lead to false positive diagnosis or incidental findings that are of uncertain clinical relevance. Estimates indicate that almost one-third of all health spending is wasteful. The 'Choosing Wisely' campaign has identified many of these wasteful tests and treatments. This perspective proposes some suggestions to focus on our critical thinking, embrace shared decision-making and stay curious about the patient we are treating. Most importantly, 'doing nothing' could be a quality indicator for EDs, and ACEM supported audits and research to develop benchmarks for certain tests and procedures in the ED are important to achieve a cultural change.

Keywords: choosing wisely; emergency department; evidence-based medicine; guidelines; parsimony.

© 2017 Australasian College for Emergency Medicine and Australasian Society for Emergency Medicine.

- Decision Making*

- Emergency Medicine*

- Emergency Service, Hospital / organization & administration

- Exploratory Behavior*

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Med Sci Monit

- v.17(1); 2011

Evidence and its uses in health care and research: The role of critical thinking

Milos jenicek.

1 Department of Clinical Epidemiology & Biostatistics, Michael G. de Groote School of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

Pat Croskerry

2 Department of Emergency Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

David L. Hitchcock

3 David L. Hitchcock, Department of Philosophy, Faculty of Humanities, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

Obtaining and critically appraising evidence is clearly not enough to make better decisions in clinical care. The evidence should be linked to the clinician’s expertise, the patient’s individual circumstances (including values and preferences), and clinical context and settings. We propose critical thinking and decision-making as the tools for making that link.

Critical thinking is also called for in medical research and medical writing, especially where pre-canned methodologies are not enough. It is also involved in our exchanges of ideas at floor rounds, grand rounds and case discussions; our communications with patients and lay stakeholders in health care; and our writing of research papers, grant applications and grant reviews.

Critical thinking is a learned process which benefits from teaching and guided practice like any discipline in health sciences. Training in critical thinking should be a part or a pre-requisite of the medical curriculum.

Sackett et al. originally defined evidence based medicine (EBM) as ‘… the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients’, and its integration with individual clinical expertise [ 1 ].’ In the nearly two decades that have intervened, there has been significant uptake of the idea that clinical care should be based upon sound, systematically researched evidence. There has been less emphasis on how clinical expertise itself might be improved, perhaps because the concept is more amorphous and difficult to define.

Clinical expertise is an amalgam of several things: there must be a solid knowledge base, some considerable clinical experience, and an ability to think, reason, and decide in a competent and well-calibrated fashion. Our focus here is on this last component: the faculties of thinking, reasoning and decision making. Clinicians must be able to integrate the best available critically appraised evidence with insights into their patients, the clinical context, and themselves [ 2 ]. To accomplish this integration, physicians need to develop their critical thinking skills. Yet historically this need has not received explicit attention in medical training. We believe that it should.

As an illustration of the use of critical thinking in clinical care, consider the following clinical scenario from emergency medicine : A 52-year-old male presents to the emergency department of a community centre with a complaint of constipation and is triaged with a low level acuity score to a ‘minors’ area. The department is extremely busy and several hours elapse before he is seen by the emergency physician. His principal complaint is constipation; he hasn’t had a bowel movement for 4 days. His abdomen is soft and non-tender. A large amount of firm stool is evident on rectal examination. He recalls a minor back strain a few days earlier. The physician orders a soapsuds enema and continues seeing other patients. After about 30 minutes he finds the nurse who administered the enema; she reports that it was ineffective. He orders a fleet enema which again proves ineffective. The nurse expresses her opinion that the patient is taking up too much time and suggests he be given an oral laxative and another fleet enema to take home with him. She is clearly unwilling to continue investing her effort in a patient with a trivial complaint. Nevertheless, the physician decides to administer a third enema himself. The third enema is only marginally effective and he then decides to disimpact the patient. The physician notes poor rectal tone and enquires further about the patient’s urination. He says he has been unable to urinate that day. On catheterisation he is found to have 1200cc. Neurological findings are equivocal: reflexes are present in both legs and there is some subjective diminished sensation.

A diagnosis of cauda equina syndrome is made and the emergency physician calls the neurosurgery service at a tertiary care hospital. It is now late in the evening. The neurosurgeon is reluctant to accept the working diagnosis. He suggests that the loss of sphincter tone might be due to the disimpaction, and argues that there was no significant history of back injury or convincing neurological findings. When the ED physician persists, the neurosurgeon suggests transferring the patient to the tertiary hospital ED for further evaluation and asks for a CT investigation of the patient’s lower spine before seeing him. The CT reveals only some minor abnormalities and the patient is kept overnight. An MRI is done in the morning. It shows extensive disc herniation with compression of nerve roots. The patient subsequently undergoes prolonged back surgery.

This case had a good outcome, although things might have been dramatically different. The patient might have suffered permanent neurological injury requiring lifelong catheterisation for urination.

Our scenario illustrates some key points about clinical decision making. At the outset, the patient presents with an apparently benign condition – constipation. The impression of a benign condition is incorporated at triage and results in a low-level acuity score and prolonged wait. The patient’s nurse also incorporates this diagnosis and exerts coercive pressure on the physician to discharge the patient. The neurosurgeon is dismissive of a physician’s assessment in a community centre ED, creating considerable inertia against referral. Thus the ED physician faces a variety of obstacles to ensure optimal patient care. These have little to do with EBM. He must resist and overcome a variety of cognitive, affective and systemic biases, his own as well as others’, and various contextual constraints. He must continue to think critically and persist in a course that has become increasingly challenging.

Our scenario also illustrates some key points about critical thinking. The initial impression of a benign condition of constipation is not the only diagnosis compatible with the patient’s symptoms. A health care professional reaching a preliminary diagnosis must be aware of the danger of fixing prematurely on this diagnosis and ignoring (or failing to look for) subsequent evidence that tells against it, as the nurse in our scenario was inclined to do. Observational and textual studies both indicate that the most common source of errors in reasoning is to close prematurely on a favoured conclusion and then ignore evidence that argues against that conclusion [ 3 ]. It is also important to keep in mind that a patient’s signs or symptoms may have more than one cause. Data that may confirm one of the causes does not necessarily rule out all the others. Attentive listening to the patient and careful looking in the data-gathering stage are essential to good medical practice, as Groopman has recently pointed out [ 4 ]. From a logical point of view, the physician’s diagnostic task is to gather data that will determine which one (or ones) of the possible causes is (or are) responsible for the patient’s problem. This goal will guide the selection of data and of additional tests. ‘Parallel’ or ‘lateral’ thinking [ 5 ] will help with the differential diagnosis.

Critical Thinking

Dewey’s original conceptualization [ 6 ] of what he called “reflective thinking” has spawned in the intervening century a variety of definitions of critical thinking, most notably that of Ennis as “ reasonable reflective thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or what to do” [ 7 ] . Scriven and Paul have elaborated this definition as “… the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skilfully conceptualizing, applying, synthesizing or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication as a guide to belief or action ” [ 8 ].

The consensus of 48 specialists in critical thinking from the fields of education, philosophy and psychology was that it should be defined as ‘ purposeful self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgement is based ’ [ 9 ]. The list of additional definitions remains impressive [ 10 , 11 ].

Even more useful than these definitions are various lists of dispositions and skills characteristic of a “critical thinker” [ 7 , 9 , 12 ]. More useful still are criteria and standards for measuring possession of those skills and dispositions [ 13 ], criteria that have been used to develop standardized tests of critical thinking skills and dispositions [ 14 – 17 ] including some with specific reference to health sciences [ 18 ].

The elements of critical thinking subsume what has variously been described as clinical judgment [ 19 ] , logic of medicine [ 20 , 21 ] , logic in medicine [ 22 ] , philosophy of medicine [ 23 ] , causal inference [ 24 ] , medical decision making [ 25 ], clinical decision making [ 26 ], clinical decision analysis [ 27 ], and clinical reasoning [ 28 ]. An increasing number of monographs on logic and critical thinking in general have appeared [ 29 – 34 ] and their content is being adapted for medicine [ 35 – 37 ].

Everyday medical practice, whether in physicians’ offices or emergency departments or hospital wards, clearly involves “ reasonable reflective thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe (meaning the understanding of the problem) and/or what to do (i.e. deciding what to do to solve the problem)” [ 7 , 38 ]. Table 1 lists specific abilities underlying critical thinking in medical practice.

Specific abilities underlying critical thinking in medical practice.

Critical thinking is also called for in medical research and medical writing. Editors of leading medical journals have called for it. Edward Huth [ 39 , 40 ], former editor of Annals of Internal Medicine, has urged that medical articles reflect better and more organized ways of reasoning. Richard Horton [ 41 , 42 ], former editor of The Lancet , has proposed the use in medical writing of a contemporary approach to argument along the lines used by the philosopher Toulmin [ 40 , 41 ]. Subsequently, two of us have developed this approach in detail for medicine [ 43 , 44 ]. Dickinson [ 45 ] has called for an argumentative approach in medical problem solving and brought it to the attention to the world of medical informatics and beyond.

Dual Process Theory

An important component of critical thinking is being aware of one’s own thinking processes. In recent years, two general modes of thinking have been described under an approach described as dual process theory. The model is universal and has been directly applied to medicine [ 46 – 48 ] and nursing [ 49 ]. One mode is fast, reflexive, autonomous, and generally referred to as intuitive or System 1 thinking. The other is slow, deliberate, rule-based, and referred to as analytical or System 2 thinking. The mechanisms that underlie System 1 thinking are based on associative learning and innate dispositions: the latter are hard-wired, as a result of the evolutionary history of our species, to respond reflexively to certain cues in the environment. We have discrete, functionally-specialized mental programs that were selected when the brain was undergoing significant development especially spanning the last 6 million years of hominid evolution [ 50 ]. Although these programs may have served us well in our ancestral past, they may not be appropriate in some aspects of modern living. Some of this System 1 substrate also underlies various heuristics and biases in our thinking – the tendency to take mental short-cuts, or demonstrate reflexive responses in certain situations, often on the basis of past experience. Not surprisingly, most error occurs in System 1 thinking.

Contemplative , or fully reflective thinking, is System 2 thinking. It suits any practice of medicine or medical research activity where there is time to utilise the best critically appraised evidence in a step-by-step process of reasoning and argument. Contemplative, fully reflective thinking is appropriate, for example, in internal medicine, psychiatry, public health, and other specialties, in etiological research and clinical trials, and in writing up the results of such research [ 35 ].

In contrast, a shortcut or heuristic approach [ 51 ] with somehow truncated thinking is often dictated by the realities of emergency medicine, surgery, obstetrics or any situation where there is incomplete information, bounded rationality, and insufficient time to be fully reflective. The extant findings and the decision maker’s experience are all that is available. The quintessential challenge for well-calibrated decision making is to optimise performance in System 1. Hogarth [ 52 ] sees this challenge as educating our intuitive processes and has delineated a variety of strategies through which this might be accomplished.

No responsible physician would engage in reflective thinking on every occasion when a decision has to be made. Such acute emergencies as sudden complications of labour and delivery, ruptured aneurysms, multiple trauma victims and other immediately life-threatening situations generally leave no time for fully reflective thinking. A shortcut or heuristic approach is required [ 51 ], involving pattern recognition, steepest ascent reasoning, or algorithmic paths [ 21 , 53 ]. There is of course a place for reflective thinking before and after such time-constrained emergency decisions. More generally, reflective thinking is called for in any aspect of medical practice where there is time and reason for it.

The distinction should be made between the involuntary autonomous nature of System 1 thinking and a deliberate decision to use a shortcut for expediency, which is System 2 thinking. There is normally an override function of System 2 over System 1 but this may be deliberately lifted under extreme conditions.

Future Direction

Critical thinking is a learned process which benefits from teaching and guided practice like any other discipline in health sciences. It was already proposed as part of an early medical curriculum [ 54 ]. If we are to train future generations of health professionals as critical thinkers, we should do so in the spirit of critical thinking as it stands today. Clinical teachers should know how to run a Socratic discourse, and in which situations it is appropriate. They should be aware of contemporary models of argument. Clinical teachers should be trained and experienced in engaging with their interns and residents in meaningful discourse while presenting and discussing morning reports, at floor and other rounds, in morbidity and mortality conferences, or at less informal ‘hallway’, ‘elevator’ or ‘coffee-maker/drinking fountain’ teaching sites for busy clinicians. Such discourse is better than so-called “pimping”, i.e. quizzing of juniors with objectives ranging from knowledge acquisition to embarrassment and humiliation [ 37 , 55 ].

Also, somebody should point out to trainees the relevance to the health context of some basics of informal logic, critical thinking and argumentation, if those basics have been acquired as the result of studying for their first undergraduate degree.

Unquestionably, the appropriate critically appraised best evidence should be used as a foundation for reasoning and argument about how to care for patients. But, if we want to link the best available evidence to a patient’s biology, the patient’s values and preferences, the clinical or community setting, and other circumstances, we should take all these factors into account in using the best available evidence to get to the beliefs and decisions that have the best possible support.