What is the Importance of Dangerous Drugs Law?

Dangerous drugs existed way centuries before. From herbal produce to chemical-based drugs, all of them have adverse effects to our body system.

Science has proven the detrimental effects of the usage of these dangerous drugs. Their chemical composition primarily affects our mental state, and their consequences are either short-term or permanent. Even when a person has stopped the use of said drugs, its damage may be continuous.

Dangerous drugs, just as human beings, evolve. When our ancestors discovered drugs as products of herbs and plants coupled with developing societies, people discovered the scientific mixing of various chemicals, which, in effect, produces these detrimental drugs.

Dangerous drugs can now be either injected, ingested, and inhaled. For instance, the effect of a drug injected goes directly in our bloodstream. Thus, the aftermath is immediate. Even a medically prescribed drug, when overused can cause adverse outcome, worse of which is death.

1) those prescribed by a duly licensed physician;

3) the most important is that the drug is not enlisted as one of those narcotics and other dangerous drugs.

| Brief Antecedents |

|---|

| In 1839, a war against drugs commenced between Qing Dynasty of China and Britain as the latter, as part of free trade, included opium in their barter. |

| This has been known as the First Opium War. However, British forces defeated the Qing Dynasty and the former imposed a treaty with open trades with China. |

| The Emperor wrote a letter to Queen Victoria to halt the opium trade completely. The war ended completely after China signed the unequal Treaty of Nanjing which effectively granted Britain’s free trade in the Chinese ports. |

Now, as the international community are well aware of the damaging side effects of these dangerous drugs not only to one’s person, but also to the greater society, these countries have promulgated their respective laws which regulate and sanction the use of dangerous drugs.

What is Dangerous Drug Act?

The first United States Anti-drug law was enacted way back November 15, 1875. It was enacted in San Francisco where it banned opium smoking and opium.

The measure on banning of opium smoking and opium dens were subsequently followed by Virginia City, and Carson in Nevada, Cheyenne, Wyoming and Montana on the succeeding years.

Due to this international treaty, the importation of opium has been vastly affected as the same was declined in several countries.

Then came 1946 when the defunct League of Nations transferred the drug control in international sphere to the newly created United Nations.

1) The Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, which was subsequently amended in 1972;

2) the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971; and

What is the Dangerous Drugs Act in the Philippines and What is its Purpose?

The new law in 1972 added heroin and morphine; coca leaf and its derivatives alpha and beta eucaine; hallucinogenic drugs, such as mescaline, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and other substances producing similar effects were added in the list of prohibited drugs.

The purpose of the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Law is anchored in its Declaration of Policy of the State to “safeguard the integrity of its territory and the well-being of its citizenry particularly the youth, from the harmful effects of dangerous drugs on their physical acts.” (Section 2, RA 9165)

What is the Target of Republic Act No. 9165

The State, in its capacity as Parens Patriae, has the obligation to ensure that its citizenry, particularly the youth, will not be destructed by the harmful effects of dangerous drugs.

Who are Punished by the Law and Why are they Punished?

1.b] Persons who are engaged in the trading or the transactions involving the illegal trafficking of dangerous drugs using electronic devices or acting such a broker in any of those transactions. It is necessary that there is money or consideration

1.c] Persons without the authority to administer dangerous drug into the body of any person, with or without the latter’s knowledge, by injection, inhalation, ingestion or other means, or by assisting any person in administering said dangerous drug to himself, unless these persons are duly licensed practitioner, and the purpose of administration is for medication.

1.d] The law also punishes any person who passed on possession of a dangerous drugs to another, and such delivery is not authorized by law. Further, for a person to be punished, the “accused must knowingly made the delivery. Worthy of note is that the delivery may be committed even without consideration.” (People vs. Maongco, G.R. No. 196966, October 23, 2013)

4] Those who operate or maintain a drug den, dive or resort where dangerous drug is used or sold in any form or any controlled precursor and essential chemical is used or sold in any form. Moreover, this provision also punishes the employee of such den, dive, or resort who is aware of the nature of such place, as well as those persons visiting the place who are also aware of the nature of such place. (Sec. 6, RA 9165

6] Those persons who are unnecessarily prescribing dangerous drugs and who unlawfully prescribe dangerous

What are the Common Acts Punished under RA 9165 and their Respective Penalties?

There are several acts punished under RA 9165, but these are the most common acts in our jurisdiction:

It is reasonable to impose maximum penalty of life imprisonment in acts transgressing and compromising the public order and integrity, and the State in its Parens Patriae capacity, has the obligation to protect to the fullest extent the interests beneficial to the youth of this country.

The penalties provided under the aforementioned provisions are again reasonable as the maintenance of drug dens, dives, or resort and the manufacture of any dangerous drugs play vital role in the malignant commerce of dangerous drugs in the society.

The penalty of life imprisonment to death and a fine ranging from P500,000.00 to P1,000,000.00 is imposable upon any person who shall unlawfully posses 10 grams or more of opium, morphine, heroine, cocaine, marijuana resin or marijuana resin oil, ecstasy, paramethoxyamphetamine (PMA), trimethoxyamphetamine (TMA), lysergic acid diethylamine (LSD), gamma hydroxyamphetamine (GHB), and those similarly designed; 50 grams or more of methamphetamine hydrochloride or “shabu”; and 500 grams or more of marijuana.

The penalty for illegal possession of drug paraphernalia is imprisonment ranging from 6 months and 1 day to 4 years and a fine ranging from P10,000.00 to P50,000.00.

Related Jurisprudence

The Supreme Court, through the years, have promulgated several cases in relation to violations of RA 9165 and set many precedents to be followed by all inferior courts in deciding drugs cases at trial court level.

Criminal intent is not an essential element.

“Marking vs. Chain of Custody”

“Marking” means the placing by the apprehending officer or the poseur-buyer of his/her initials and signature on the items seized to identify it as the subject matter of the prohibited sale. Marking after seizure is the starting point in the custodial link and is vital to be immediately undertaken because succeeding handlers of the specimens will use the markings as reference. Chain of custody is defined as “the duly recorded authorized movements and custody of seized drugs or controlled chemicals or plant sources of dangerous drugs or laboratory equipment of each stage, from the time of seizure/confiscation to receipt in the forensic laboratory to safekeeping to presentation in court for destruction.” Such record of movements and custody of seized item shall include the identity and signature of the person who held temporary custody of the seized item, the date and time when such transfer of custody were made in the course of safekeeping and use in court as evidence, and the final disposition. 7

The Supreme Court moreover added guidelines in chain of custody in a buy-bust situation.

Come 2018, when the Supreme Court imposed a stricter and mandatory requirement for drug enforcement authorities in conducting anti-dangerous drug operations. This was elucidated in the case of People vs. Romy Lim. Justice Peralta, stressed down the following policy to be enforced in connection with arrests and seizures in cases involving dangerous drugs, viz:

“In order to weed out early on from the courts’ already congested docket any orchestrated or poorly built up drug- related cases, the following should henceforth be enforced as a mandatory policy:

1] In the sworn statements/affidavits, the apprehending/seizing officers must state their compliance with the requirements of Section 21 (1) of R.A. No. 9165, as amended, and its IRR.

4] If the investigating fiscal filed the case despite such absence, the court may exercise its discretion to either refuse to issue a commitment order (or warrant of arrest) or dismiss the case outright for lack of probable cause in accordance with Section 5, Rule 112, Rules of Court”

The declaration as unconstitutional the prohibition against plea bargaining in drug cases, is a landmark case in drugs cases. In the case of Estipona vs. Lobrigo, 9 the Supreme Court held that:

“[t]he power to promulgate rules of pleading, practice and procedure is now [the Supreme Court’s] exclusive domain and no longer shared with the Executive and Legislative departments.”

Thus, the power to promulgate rules of procedure is lodged with the Supreme Court and this cannot be repealed or amended by subsequent substantive laws the Congress has to enact.

Final Thoughts

RA 9165 is a broad yet concise law. It was carefully crafted by our lawmakers. As I have mentioned, this law is a valid exercise of the State’s Police Power.

The proper exercise of the police power requires the concurrence of a lawful subject and a lawful method . ( Gerochi v. Department of Energy, as cited in Southern Luzon Drug Corporation vs. DSWD, G.R. No. 199669, April 25, 2017)

The lawful subject in here is the suppression of the dangerous drugs in our country and the lawful method is to impose the maximum penalty imposable in our jurisdiction to those who will be found guilty of the acts punishable under RA 9165.

This is a special penal law. Thus, defense of good faith is untenable .

It is an elementary rule in Criminal Law that the criminal intent in crimes malum prohibitum is not necessary and cannot be invoked as a defense.

It is because, crime malum prohibitum , in a literal term- PROHIBITS one from doing this and that, as in this case, in RA 9165, it is prohibited to possess dangerous drugs without lawful authority or satisfactory justification.

RALB Law | RABR & Associates Law Firm

Leave a reply.

Email * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

- Subscribe Now

The dangers of the Dangerous Drugs Act

Already have Rappler+? Sign in to listen to groundbreaking journalism.

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – It is one of the Philippines’ main weapons against illegal drugs yet Republic Act 9165 or the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002 looks good only on paper.

With President Rodrigo Duterte’s fight against drugs, this 14-year-old measure was suddenly put under the spotlight.

RA 9165 mandates the government to “pursue an intensive and unrelenting campaign against the trafficking and use of dangerous drugs and other similar substances.”

Under the law, those caught importing, selling, manufacturing, and using illegal drugs and its forms may be fined and imprisoned for at least 12 years to a lifetime, depending on the severity of the crime.

Since the law was passed at a time the death penalty was still applicable, it is the maximum punishment imposed by the original law. This, however, is moot at present as the death penalty was already abolished in 2006.

If such strict law was passed 14 years ago in 2002, the question remains: Why does the multi-billion drug industry remain unstoppable?

Duterte’s strong drive against drugs has raised more questions than answers involving the measure: Is the law effective? What else can be done? What went wrong?

For Senate Majority Leader Vicente Sotto III, principal sponsor of the law, the legislation is anything but a failure.

Had the law been implemented properly and consistently, Sotto said the country’s drug problem would not be as massive as it is now.

“Kaya lumala hindi inimplementa nang tama ang batas noong mga nakaraang taon. Mula 2002 hanggang ngayon, every now and then parang roller coaster, may panahon na aasikasuhin, may panahon na hindi. Talagang execution ang problema. Ang ganda na nga eh,” Sotto told Rappler.

(That’s why it got worse because the law was not properly implemented in the past year. Starting 2002 until now, it’s like a roller coaster. It’s implemented every now and then, there are times it would be prioritized, there are times not. Execution is really the problem. The law is already good.)

Past administrations had their own respective focus. Now, Duterte’s single agenda of fighting criminality has opened the floodgates of issues that had long been neglected.

Politics? PDEA vs DDB

RA 9165 repealed RA 6425 or the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1972. The law mandates the Dangerous Drugs Board to be the policy- and strategy-making body that plans and formulates programs on drug prevention and control.

Article 9, Section 77 of the law states that the DDB “shall develop and adopt a comprehensive, integrated, unified and balanced national drug abuse prevention and control strategy. It shall be under the Office of the President.”

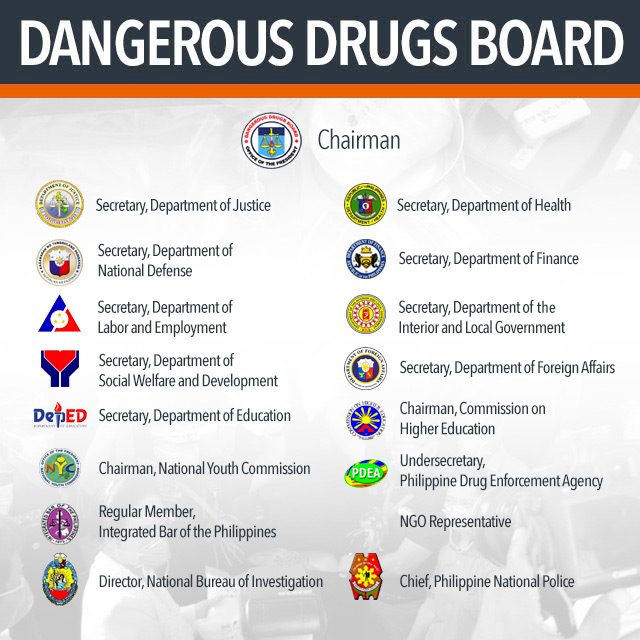

The DDB is composed of 17 members, including the chairman with the rank of Secretary.

The law also created the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA), which serves as the implementing arm of the DDB, and is automatically part of the 17-member DDB.

These two, ideally, work hand in hand to fight drugs. In reality, however, politics and bureaucracy get in the way of things.

The DDB chair has a rank of secretary, while the PDEA Director General is considered an undersecretary. But since it is PDEA that implements the law and does the operations on the ground, Sotto said PDEA tends to reject being under the DDB.

“May leadership problem. Yung PDEA at DDB chair, hindi nagkakasundo. May feeling sila di sila subservient sa isa’t isa. So ang nangyari, ang PDEA feeling nila di sila subservient sa DDB, di nga umaattend ng forum regularly. Magkasama yan sa opisina. Ilang taon yan. Ewan ko kung bakit,” Sotto said.

(There’s a leadership problem. The PDEA and the DDB chairmen are not on good terms. Each of them has a feeling that they are not subservient to each other. So what happens, PDEA feels it is not subservient to DDB, it does not attend regularly. They share the same office. It has been going on for years, I don’t know why.)

DDB Chairman Felipe Rojas Jr, for his part, admitted politics exists inside but downplayed its effect, saying it is not enough to jeopardize the entirety of the anti-drug effort.

“Yung appointment of officials, yung iba hindi qualified, minsan intervention ng pulitika, ” Rojas said. (The appointment of officials – some are not qualified, sometimes politics intervenes.)

This does not come as a surprise to some, as such is the situation in most government offices in the country.

Senator Grace Poe, former Senate committee chair on public order, said the track record of appointees should be checked.

“I really think it all boils down to the credibility of the people you will assign in those posts. In the past kasi, mga nandun sa PNP (Philippine National Police), nandun sa iba’t ibang organizations, so sila-sila pa rin (In the past, those from the PNP are also in other organizations, so it’s just always them). I really think kailangan ma-vet mabuti yung Dangerous Drugs Board (I really think those in the Dangerous Drugs Board should be properly vetted) ,” Poe said.

But while the suggestion is good, the reality is that appointments still depend on one person – the president. He himself chooses who leads the crucial agencies of PDEA and the executive offices that comprise the DDB.

As of posting time, Rojas was already relieved from his post after Duterte ordered appointees of former president Benigno Aquino III to submit a courtesy resignation. The President has now assigned the post to former assistant secretary Benjie Reyes.

As simple as quorum

The politics inside the board may have more repercussions than what meets the eye. Another problem of the board is the lack of quorum, which requires 9 out of 17 members. While it may not necessarily be political, such challenge shows the seemingly shaky dynamics inside, which in turn sheds light on the struggles of policy formation and implementation.

The DDB has 17 members from all aspects of drug rehabilitation precisely because the law wants a holistic approach to the complex drug problem. But while the intent is good, the same could not be said about the agencies involved.

The law mandates that the DDB meet once a week or “as often as necessary at the discretion of the Chairman or at the call of any 4 other members.”

One may call it lucky if the board gets to meet weekly. At the very least, the Board meets once a month, according to Rojas.

Asked if he, as chair, has powers to compel and convince other board members to attend, Rojas only had this to say:

“Very limited, in fact, wala talaga. In some agencies sa abroad, ang DDB ang may hawak ng pondo. As they say, the one who holds the gold rules. Kapag ikaw may hawak ng pondo susunod sa ‘yo yan pero wala sa akin,” he said.

(Very limited. In fact, none. In some agencies abroad, the DDB holds the funds. As they say, the one who holds the gold rules. If you hold the funds, they will follow you but it’s not with me.)

Sotto, former DDB chairman, echoed Rojas’ sentiment.

“’Di nagmi-meet regularly dahilan lagi walang quorum. Hindi uma-attend secretaries. Yung mga secretaries nagpapadala ng undersecretaries, puwede naman yun na representative lang, pero yun mga Usec nila di rin uma-attend eh,” said Sotto.

(The board does not meet regularly, the usual excuse is lack of quorum. The secretaries do not attend. The secretaries send their undersecretaries as their representatives, which is allowed, but the undersecretaries do not attend too.)

The surge in the popularity of Duterte’s anti-drug campaign has given the DDB a huge role to fill, something difficult to accomplish all at once, especially if institutions have long been weak.

“Matagal ang decision-making process – convene the board, magno-notice ka pa. You have to wait for the resolution. Unlike other countries, isa lang ang decision-making at mabilis,” Rojas said.

(The decision-making process takes a while – convene the board, you have to submit notice. You have to wait for the resolution. Unlike other countries, their decision-making process is unified and fast.)

To be concluded – Rappler.com

(READ: Part 2: The dangers of the Dangerous Drugs Act )

Add a comment

Please abide by Rappler's commenting guidelines .

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.

How does this make you feel?

Related Topics

Camille Elemia

Recommended stories, {{ item.sitename }}, {{ item.title }}.

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The War On Drugs: 50 Years Later

After 50 years of the war on drugs, 'what good is it doing for us'.

During the War on Drugs, the Brownsville neighborhood in New York City saw some of the highest rates of incarceration in the U.S., as Black and Hispanic men were sent to prison for lengthy prison sentences, often for low-level, nonviolent drug crimes. Spencer Platt/Getty Images hide caption

During the War on Drugs, the Brownsville neighborhood in New York City saw some of the highest rates of incarceration in the U.S., as Black and Hispanic men were sent to prison for lengthy prison sentences, often for low-level, nonviolent drug crimes.

When Aaron Hinton walked through the housing project in Brownsville on a recent summer afternoon, he voiced love and pride for this tightknit, but troubled working-class neighborhood in New York City where he grew up.

He pointed to a community garden, the lush plots of vegetables and flowers tended by volunteers, and to the library where he has led after-school programs for kids.

But he also expressed deep rage and sorrow over the scars left by the nation's 50-year-long War on Drugs. "What good is it doing for us?" Hinton asked.

Revisiting Two Cities At The Front Line Of The War On Drugs

Critics Say Chauvin Defense 'Weaponized' Stigma For Black Americans With Addiction

As the United States' harsh approach to drug use and addiction hits the half-century milestone, this question is being asked by a growing number of lawmakers, public health experts and community leaders.

In many parts of the U.S., some of the most severe policies implemented during the drug war are being scaled back or scrapped altogether.

Hinton, a 37-year-old community organizer and activist, said the reckoning is long overdue. He described watching Black men like himself get caught up in drugs year after year and swept into the nation's burgeoning prison system.

"They're spending so much money on these prisons to keep kids locked up," Hinton said, shaking his head. "They don't even spend a fraction of that money sending them to college or some kind of school."

Aaron Hinton, a 37-year-old veteran activist and community organizer, said it's clear Brownsville needed help coping with the cocaine, heroin and other drug-related crime that took root here in the 1970s and 1980s. His own family was devastated by addiction. Brian Mann hide caption

Aaron Hinton, a 37-year-old veteran activist and community organizer, said it's clear Brownsville needed help coping with the cocaine, heroin and other drug-related crime that took root here in the 1970s and 1980s. His own family was devastated by addiction.

Hinton has lived his whole life under the drug war. He said Brownsville needed help coping with cocaine, heroin and drug-related crime that took root here in the 1970s and 1980s.

His own family was scarred by addiction.

"I've known my mom to be a drug user my whole entire life," Hinton said. "She chose to run the streets and left me with my great-grandmother."

Four years ago, his mom overdosed and died after taking prescription painkillers, part of the opioid epidemic that has killed hundreds of thousands of Americans.

Hinton said her death sealed his belief that tough drug war policies and aggressive police tactics would never make his family or his community safer.

The nation pivots (slowly) as evidence mounts against the drug war

During months of interviews for this project, NPR found a growing consensus across the political spectrum — including among some in law enforcement — that the drug war simply didn't work.

"We have been involved in the failed War on Drugs for so very long," said retired Maj. Neill Franklin, a veteran with the Baltimore City Police and the Maryland State Police who led drug task forces for years.

He now believes the response to drugs should be handled by doctors and therapists, not cops and prison guards. "It does not belong in our wheelhouse," Franklin said during a press conference this week.

Aaron Hinton has lived his whole life under the drug war. He has watched many Black men like himself get caught up in drugs year after year, swept into the nation's criminal justice system. Brian Mann/NPR hide caption

Aaron Hinton has lived his whole life under the drug war. He has watched many Black men like himself get caught up in drugs year after year, swept into the nation's criminal justice system.

Some prosecutors have also condemned the drug war model, describing it as ineffective and racially biased.

"Over the last 50 years, we've unfortunately seen the 'War on Drugs' be used as an excuse to declare war on people of color, on poor Americans and so many other marginalized groups," said New York Attorney General Letitia James in a statement sent to NPR.

On Tuesday, two House Democrats introduced legislation that would decriminalize all drugs in the U.S., shifting the national response to a public health model. The measure appears to have zero chance of passage.

But in much of the country, disillusionment with the drug war has already led to repeal of some of the most punitive policies, including mandatory lengthy prison sentences for nonviolent drug users.

In recent years, voters and politicians in 17 states — including red-leaning Alaska and Montana — and the District of Columbia have backed the legalization of recreational marijuana , the most popular illicit drug, a trend that once seemed impossible.

Last November, Oregon became the first state to decriminalize small quantities of all drugs , including heroin and methamphetamines.

Many critics say the course correction is too modest and too slow.

"The war on drugs was an absolute miscalculation of human behavior," said Kassandra Frederique, who heads the Drug Policy Alliance, a national group that advocates for total drug decriminalization.

She said the criminal justice model failed to address the underlying need for jobs, health care and safe housing that spur addiction.

Indeed, much of the drug war's architecture remains intact. Federal spending on drugs — much of it devoted to interdiction — is expected to top $37 billion this year.

The Coronavirus Crisis

Drug overdose deaths spiked to 88,000 during the pandemic, white house says.

The U.S. still incarcerates more people than any other nation, with nearly half of the inmates in federal prison held on drug charges .

But the nation has seen a significant decline in state and federal inmate populations, down by a quarter from the peak of 1.6 million in 2009 to roughly 1.2 million last year .

There has also been substantial growth in public funding for health care and treatment for people who use drugs, due in large part to passage of the Affordable Care Act .

"The best outcomes come when you treat the substance use disorder [as a medical condition] as opposed to criminalizing that person and putting them in jail or prison," said Dr. Nora Volkow, who has been head of the National Institute of Drug Abuse since 2003.

Volkow said data shows clearly that the decision half a century ago to punish Americans who struggle with addiction was "devastating ... not just to them but actually to their families."

From a bipartisan War on Drugs to Black Lives Matter

Wounds left by the drug war go far beyond the roughly 20.3 million people who have a substance use disorder .

The campaign — which by some estimates cost more than $1 trillion — also exacerbated racial divisions and infringed on civil liberties in ways that transformed American society.

Frederique, with the Drug Policy Alliance, said the Black Lives Matter movement was inspired in part by cases that revealed a dangerous attitude toward drugs among police.

In Derek Chauvin's murder trial, the former officer's defense claimed aggressive police tactics were justified because of small amounts of fentanyl in George Floyd's body. Critics described the argument as an attempt to "weaponize" Floyd's substance use disorder and jurors found Chauvin guilty.

Breonna Taylor, meanwhile, was shot and killed by police in her home during a drug raid . She wasn't a suspect in the case.

"We need to end the drug war not just for our loved ones that are struggling with addiction, but we need to remove the excuse that that is why law enforcement gets to invade our space ... or kill us," Frederique said.

The United States has waged aggressive campaigns against substance use before, most notably during alcohol Prohibition in the 1920s and 1930s.

The modern drug war began with a symbolic address to the nation by President Richard Nixon on June 17, 1971.

Speaking from the White House, Nixon declared the federal government would now treat drug addiction as "public enemy No. 1," suggesting substance use might be vanquished once and for all.

"In order to fight and defeat this enemy," Nixon said, "it is necessary to wage a new all-out offensive."

President Richard Nixon's speech on June 17, 1971, marked the symbolic start of the modern drug war. In the decades that followed Democrats and Republicans embraced ever-tougher laws penalizing people with addiction.

Studies show from the outset drug laws were implemented with a stark racial bias , leading to unprecedented levels of mass incarceration for Black and brown men .

As recently as 2018, Black men were nearly six times more likely than white men to be locked up in state or federal correctional facilities, according to the U.S. Justice Department .

Researchers have long concluded the pattern has far-reaching impacts on Black families, making it harder to find employment and housing, while also preventing many people of color with drug records from voting .

In a 1994 interview published in Harper's Magazine , Nixon adviser John Ehrlichman suggested racial animus was among the motives shaping the drug war.

"We knew we couldn't make it illegal to be either against the [Vietnam] War or Black," Ehrlichman said. "But by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities."

Despite those concerns, Democrats and Republicans partnered on the drug war decade after decade, approving ever-more-severe laws, creating new state and federal bureaucracies to interdict drugs, and funding new armies of police and federal agents.

At times, the fight on America's streets resembled an actual war, especially in poor communities and communities of color.

Police units carried out drug raids with military-style hardware that included body armor, assault weapons and tanks equipped with battering rams.

President Richard Nixon explaining aspects of the special message sent to the Congress on June 17, 1971, asking for an extra $155 million for a new program to combat the use of drugs. He labeled drug abuse "a national emergency." Harvey Georges/AP hide caption

President Richard Nixon explaining aspects of the special message sent to the Congress on June 17, 1971, asking for an extra $155 million for a new program to combat the use of drugs. He labeled drug abuse "a national emergency."

"What we need is another D-Day, not another Vietnam, not another limited war fought on the cheap," declared then-Sen. Joe Biden, D-Del., in 1989.

Biden, who chaired the influential Senate Judiciary Committee, later co-authored the controversial 1994 crime bill that helped fund a vast new complex of state and federal prisons, which remains the largest in the world.

On the campaign trail in 2020, Biden stopped short of repudiating his past drug policy ideas but said he now believes no American should be incarcerated for addiction. He also endorsed national decriminalization of marijuana.

While few policy experts believe the drug war will come to a conclusive end any time soon, the end of bipartisan backing for punitive drug laws is a significant development.

More drugs bring more deaths and more doubts

Adding to pressure for change is the fact that despite a half-century of interdiction, America's streets are flooded with more potent and dangerous drugs than ever before — primarily methamphetamines and the synthetic opioid fentanyl.

"Back in the day, when we would see 5, 10 kilograms of meth, that would make you a hero if you made a seizure like that," said Matthew Donahue, the head of operations at the Drug Enforcement Administration.

As U.S. Corporations Face Reckoning Over Prescription Opioids, CEOs Keep Cashing In

"Now it's common for us to see 100-, 200- and 300-kilogram seizures of meth," he added. "It doesn't make a dent to the price."

Efforts to disrupt illegal drug supplies suffered yet another major blow last year after Mexican officials repudiated drug war tactics and began blocking most interdiction efforts south of the U.S.-Mexico border.

"It's a national health threat, it's a national safety threat," Donahue told NPR.

Last year, drug overdoses hit a devastating new record of 90,000 deaths , according to preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The drug war failed to stop the opioid epidemic

Critics say the effectiveness of the drug war model has been called into question for another reason: the nation's prescription opioid epidemic.

Beginning in the late 1990s, some of the nation's largest drug companies and pharmacy chains invested heavily in the opioid business.

State and federal regulators and law enforcement failed to intervene as communities were flooded with legally manufactured painkillers, including Oxycontin.

"They were utterly failing to take into account diversion," said West Virginia Republican Attorney General Patrick Morrisey, who sued the DEA for not curbing opioid production quotas sooner.

"It's as close to a criminal act as you can find," Morrisey said.

Courtney Hessler, a reporter for The (Huntington) Herald-Dispatch in West Virgina, has covered the opioid epidemic. As a child she wound up in foster care after her mother became addicted to opioids. "You know there's thousands of children that grew up the way that I did. These people want answers," Hessler told NPR. Brian Mann/NPR hide caption

Courtney Hessler, a reporter for The (Huntington) Herald-Dispatch in West Virgina, has covered the opioid epidemic. As a child she wound up in foster care after her mother became addicted to opioids. "You know there's thousands of children that grew up the way that I did. These people want answers," Hessler told NPR.

One of the epicenters of the prescription opioid epidemic was Huntington, a small city in West Virginia along the Ohio River hit hard by the loss of factory and coal jobs.

"It was pretty bad. Eighty-one million opioid pills over an eight-year period came into this area," said Courtney Hessler, a reporter with The (Huntington) Herald-Dispatch.

Public health officials say 1 in 10 residents in the area still battle addiction. Hessler herself wound up in foster care after her mother struggled with opioids.

In recent months, she has reported on a landmark opioid trial that will test who — if anyone — will be held accountable for drug policies that failed to keep families and communities safe.

"I think it's important. You know there's thousands of children that grew up the way that I did," Hessler said. "These people want answers."

A needle disposal box at the Cabell-Huntington Health Department sits in the front parking lot in 2019 in Huntington, W.Va. The city is experiencing a surge in HIV cases related to intravenous drug use following a recent opioid crisis in the state. Ricky Carioti/The Washington Post via Getty Images hide caption

A needle disposal box at the Cabell-Huntington Health Department sits in the front parking lot in 2019 in Huntington, W.Va. The city is experiencing a surge in HIV cases related to intravenous drug use following a recent opioid crisis in the state.

During dozens of interviews, community leaders told NPR that places like Huntington, W.Va., and Brownsville, N.Y., will recover from the drug war and rebuild.

They predicted many parts of the country will accelerate the shift toward a public health model for addiction: treating drug users more often like patients with a chronic illness and less often as criminals.

But ending wars is hard and stigma surrounding drug use, heightened by a half-century of punitive policies, remains deeply entrenched. Aaron Hinton, the activist in Brownsville, said it may take decades to unwind the harm done to his neighborhood.

"It's one step forward, two steps back," Hinton said. "But I remain hopeful. Why? Because what else am I going to do?"

- drug policy

- war on drugs

- public health

- opioid epidemic

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.335(7627); 2007 Nov 10

Head to Head

Should drugs be decriminalised no, joseph a califano, jr.

The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, 633 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017-6706, USA

Recent government figures suggest that the UK drug treatment programmes have had limited success in rehabilitating drug users, leading to calls for decriminalisation from some parties. Kailash Chand believes that this is the best way to reduce the harm drugs cause, but Joseph Califano thinks not

Drug misuse (usually called abuse in the United States) infects the world's criminal justice, health care, and social service systems. Although bans on the import, manufacture, sale, and possession of drugs such as marijuana, cocaine, and heroin should remain, drug policies do need a fix. Neither legalisation nor decriminalisation is the answer. Rather, more resources and energy should be devoted to research, prevention, and treatment, and each citizen and institution should take responsibility to combat all substance misuse and addiction.

Vigorous and intelligent enforcement of criminal law makes drugs harder to get and more expensive. Sensible use of courts, punishment, and prisons can encourage misusers to enter treatment and thus reduce crime. Why not treat a teenager arrested for marijuana use in the same way that the United States treats someone arrested for drink-driving when no injury occurs? See the arrest as an opportunity and require the teenager to be screened, have any needed treatment, and attend sessions to learn about the dangers of marijuana use.

The medical profession and the public health community should educate society that addiction is a complex physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual disease, not a moral failing or easily abandoned act of self indulgence. Children should receive education and prevention programmes that take into account cultural and sex differences and are relevant to their age. We should make effective treatment available to all who need it and establish high standards of training for treatment providers. Social service programmes, such as those to help abused children and homeless people, should confront the drug and alcohol misuse and addiction commonly involved, rather than ignore or hide it because of the associated stigma.

Availability is the mother of use

What we don't need is legalisation or decriminalisation, which will make illegal drugs cheaper, easier to obtain, and more acceptable to use. The United States has some 60 million smokers, up to 20 million alcoholics and alcohol misusers, but only around six million illegal drug addicts. 1 If illegal drugs were easier to obtain, this figure would rise.

Switzerland's “needle park,” touted as a way to restrict a few hundred heroin users to a small area, turned into a grotesque tourist attraction of 20 000 addicts and had to be closed before it infected the entire city of Zurich. 2 Italy, where personal possession of a few doses of drugs like heroin has generally been exempt from criminal sanction, 2 has one of the highest rates of heroin addiction in Europe, 3 with more than 60% of AIDS cases there attributable to intravenous drug use. 4

Most legalisation advocates say they would legalise drugs only for adults. Our experience with tobacco and alcohol shows that keeping drugs legal “for adults only” is an impossible dream. Teenage smoking and drinking are widespread in the United States, United Kingdom, and Europe.

The Netherlands established “coffee shops,” where customers could select types of marijuana just as they might choose ice cream flavours. 2 Between 1984 and 1992, adolescent use nearly tripled. 2 Responding to international pressure and the outcry from its own citizens, the Dutch government reduced the number of marijuana shops and the amount that could be sold and raised the age for admission from 16 to 18. 2 5 In 2007, the Dutch government announced plans to ban the sale of hallucinogenic mushrooms. 6

Restriction

Recent events in Britain highlight the importance of curbing availability. In 2005, the government extended the hours of operation for pubs, with some allowed to serve 24 hours a day. 7 Rather than curbing binge drinking, the result has been a sharp increase in crime between 3 am and 6 am, 8 in violent crimes in certain pubs, 9 and in emergency treatment for alcohol misusers. 7

Sweden offers an example of a successful restrictive drug policy. Faced with rising drug use in the 1990s, the government tightened drug control, stepped up police action, mounted a national action plan, and created a national drug coordinator. 10 The result: “Drug use is just a third of the European average.” 11

Almost daily we learn more about marijuana's addictive and dangerous characteristics. Today's teenagers' pot is far more potent than their parents' pot. The average amount of tetrahydrocannabinol, the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana, in seized samples in the United States has more than doubled since 1983. 12 Antonio Maria Costa, director of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), has warned, “Today, the harmful characteristics of cannabis are no longer that different from those of other plant-based drugs such as cocaine and heroin.” 13

Evidence that cannabis use can cause serious mental illness is mounting. 13 A study published in the Lancet “found a consistent increase in incidence of psychosis outcomes in people who had used cannabis.” 14 The study prompted the journal's editors to retract their 1995 statement that, “smoking of cannabis, even long term, is not harmful to health.” 15

Drugs are not dangerous because they are illegal; they are illegal because they are dangerous. A child who reaches age 21 without smoking, misusing alcohol, or using illegal drugs is virtually certain to never do so. 16 Today, most children don't use illicit drugs, but all of them, particularly the poorest, are vulnerable to misuse and addiction. Legalisation and decriminalisation—policies certain to increase illegal drug availability and use among our children—hardly qualify as public health approaches.

Competing interests: None declared.

Understanding the Demand for Illegal Drugs (2010)

Chapter: 1 introduction, 1 introduction.

A merica’s problem with illegal drugs seems to be declining, and it is certainly less in the news than it was 20 years ago. Surveys have shown a decline in the number of users dependent on expensive drugs (Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2001), an aging of the population in treatment (Trunzo and Henderson, 2007), and a decline in the violence related to drug markets (Pollack et al., 2010). Still, research indicates that illegal drugs remain a concern for the majority of Americans (Caulkins and Mennefee, 2009; Gallup Poll, 2009).

There is virtually no disagreement that the trafficking in and use of cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine continue to cause great harm to the nation, particularly to vulnerable minority communities in the major cities. In contrast, there is disagreement about marijuana use, which remains a part of adolescent development for about half of the nation’s youth. The disagreement concerns the amount, source, and nature of the harms from marijuana. Some note, for example, that most of those who use marijuana use it only occasionally and neither incur nor cause harms and that marijuana dependence is a much less serious problem than dependence on alcohol or cocaine. Others emphasize the evidence of a potential for triggering psychosis (Arseneault et al., 2004) and the strengthening evidence for a gateway effect (i.e., an opening to the use of other drugs) (Fergusson et al., 2006). The uncertainty of the causal mechanism is reflected in the fact that the gateway studies cannot disentangle the effect of the drug itself from its status as an illegal good (Babor et al., 2010).

The federal government probably spends $20 billion per year on a wide array of interventions to try to reduce drug consumption in the United States, from crop eradication in Colombia to mass media prevention programs aimed at preteens and their parents. 1 State and local governments spend comparable amounts, mostly for law enforcement aimed at suppressing drug markets. 2 Yet the available evidence, reviewed in detail in this report, shows that drugs are just as cheap and available as they have ever been.

Though fewer young people are starting to use drugs than in some previous years, for each successive birth cohort that turns 21, approximately half have experimented with illegal drugs. The number of people who are dependent on cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine is probably declining modestly, 3 and drug-related violence has appears to have declined sharply. 4 At the same time, injecting drug use is still a major vector for HIV transmission, and drug markets blight parts of many U.S. cities.

The declines in drug use that have occurred in recent years are probably mostly the natural working out of old epidemics. Policy measures— whether they involve prevention, treatment, or enforcement—have met with little success at the population level (see Chapter 4 ). Moreover, research on prevention has produced little evidence of any targeted interventions that make a substantial difference in initiation to drugs when implemented on a large scale. For treatment programs, there is a large body of evidence of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness (reviewed in Babor et al., 2010), but the supply of treatment facilities is inadequate and,

|

| The official estimate from the Office of National Drug Control Policy of $14.8 billion in fiscal 2009 excludes a number of major items, such as the cost of prosecuting and incarcerating those arrested by federal agencies for violations of drug laws. See Carnevale (2009) for a detailed analysis of the limits of the official estimate of the federal drug budget. |

|

| The only estimates of drug-related expenditures by state and local governments are for 1990 and 1991 (Office of National Drug Control Policy, 1993). Given the number of people prosecuted and incarcerated each year for drug offenses, that estimate remains a plausible but unsubstantiated claim. |

|

| The most recent published estimates only extend through 2000 (Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2001). |

|

| There are no specific indices that measure drug-related violence. The assumption of reduced violence reflects an inference from (1) the aging of the populations that are dependent on cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine as reflected in the Treatment Episode Data Set, maintained by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; (2) the declining share of arrests of drug users that are for violent crimes, as reflected in the Surveys of Prison and Jail Inmates (Pollack et al., 2010); (3) the 70 percent decline in homicides since 1991; and (4) the increasing share of drug transactions that are conducted in nonpublic settings. |

perversely, not enough of those who need treatment are persuaded to seek it (see Chapter 4 ). Efforts to raise the price of drugs through interdiction and other enforcement programs have not had the intended effects: the prices of cocaine and heroin have declined for more than 25 years, with only occasional upward blips that rarely last more than 9 months (Walsh, 2009).

STUDY PROJECT AND GOALS

Given the persistence of drug demand in the face of lengthy and expensive efforts to control the markets, the National Institute of Justice asked the National Research Council (NRC) to undertake a study of current research on the demand for drugs in order to help better focus national efforts to reduce that demand. In response to that request, the NRC formed the Committee on Understanding and Controlling the Demand for Illegal Drugs. The committee convened a workshop of leading researchers in October 2007 and held two follow-up meetings to prepare this report. The statement of task for this project is as follows:

An ad hoc committee will conduct a workshop-based study that will identify and describe what is known about the nature and scope of markets for illegal drugs and the characteristics of drug users. The study will include exploration of research issues associated with drug demand and what is needed to learn more about what drives demand in the United States. The committee will specifically address the following issues:

What is known about the nature and scope of illegal drug markets and differences in various markets for popular drugs?

What is known about the characteristics of consumers in different markets and why the market remains robust despite the risks associated with buying and selling?

What issues can be identified for future research? Possibilities include the respective roles of dependence, heavy use, and recreational use in fueling the market; responses that could be developed to address different types of users; the dynamics associated with the apparent failure of policy interventions to delay or inhibit the onset of illegal drug use for a large proportion of the population; and the effects of enforcement on demand reduction.

Drawing on commissioned papers and presentations and discussions at a public workshop that it will plan and hold, the committee will prepare a report on the nature and operations of the illegal drug market in the United States and the research issues identified as having potential for informing policies to reduce the demand for illegal drugs.

The committee drew on economic models and their supporting data, as well as other research, as one part of the evidentiary base for this

report. However, the context for and content of this report were informed as well by the general discussion and the presentations in the workshop. The committee was not able to fully address task 2 because research in that area is not strong enough to give an accurate description of consumers across different markets nor to address the questions about why markets remain robust despite the risks associated with buying and selling. The discussion at the workshop underscored the point that neither the available ethnographic research nor the limited longitudinal research on drug-seeking behavior is strong enough to inform these questions related to task 2. With regard to task 3, the committee benefitted considerably from the paper by Jody Sindelar that was presented at the workshop and its discussion by workshop participants.

This study was intended to complement Informing America’s Policy on Illegal Drugs: What We Don’t Know Keeps Hurting Us (National Research Council, 2001) by giving more attention to the sources of demand and assessing the potential of demand-side interventions to make a substantial difference to the nation’s drug problems. This report therefore refers to supply-side considerations only to the extent necessary to understand demand.

The charge to the committee was extremely broad. It could have included reviewing the literature on such topics as characteristics of substance users, etiology of initiation of use, etiology of dependence, drug use prevention programs, and drug treatments. Two considerations led to narrowing the focus of our work. The first was substantive. Each of the topics just noted involves a very large field of well-developed research, and each has been reviewed elsewhere. Moreover, each of these areas of inquiry is currently expanding as a result of new research initiatives 5 and new technologies (e.g., neuroimaging, genetics). The second consideration was practical: given the available resources, we could not undertake a complete review of the entire field.

Thus, we decided to focus our work and this report tightly on demand models in the field of economics and to evaluate the data needs for advancing this relatively undeveloped area of investigation. That is, this area has a relatively shorter history of accumulated findings than the more clinical, biological, and epidemiological areas of drug research. Yet it is arguably better situated to inform government policy at the national level. A report on economic models and supporting data seemed to us more timely than a report on drug consumers and drug interventions.

The rest of this chapter briefly lays out some concepts that provide a basis for understanding the committee’s work and the rest of the report.

|

| These include the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions and the Community Epidemiology Work Group of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. |

Chapter 2 presents the economic framework that seems most useful for studying the phenomenon of drug demand. It emphasizes the importance of understanding the responsiveness of demand and supply to price, which is the intermediate variable targeted by the principal government programs in the United States, namely, drug law enforcement. Chapter 3 then examines changes in the consumption of drugs and assesses the various indicators that are available to measure that consumption. Chapter 4 turns to the program type that most focuses specifically on reducing drug demand, the treatment of dependent users. It considers how well these programs work and how the treatment system might be expanded to further reduce consumption. Finally, Chapter 5 presents our recommendations for how the data and research base might be built to improve understanding of the demand for drugs and policies to reduce it.

PROGRAM CONCEPTS

A standard approach to considering drug policy is to divide programs into supply side and demand side. This approach accepts that drugs, as commodities, albeit illegal ones, are sold in markets. Supply-side programs aim to reduce drug consumption by making it more expensive to purchase drugs through increasing costs to producers and distributors. Demand-side programs try to lower consumption by reducing the number of people who, at a given price, seek to buy drugs; the amount that the average user wishes to consume; or the nonmonetary costs of obtaining the drugs. This approach has value, but it also raises questions.

The value of this framework is that it allows systematic evaluation of programs. A successful supply-side program will raise the price of drugs, as well as reduce the quantity available, while a demand-side program will lower both the number of users and the quantity consumed, as well as eventually reducing the price. As noted above, this report is primarily focused on improving understanding of the sources of demand.

There are two basic objections to this approach. First, some programs have both demand- and supply-side effects. Since many dealers are themselves heavy users, drug treatment will reduce supply, just as incarceration of drug dealers lowers demand. Second, there is a collection of programs that do not attempt to reduce demand or supply; rather, their goal is to reduce the damage that drug use and drug markets cause society, which are generally referred to as “harm-reduction” programs (Iversen, 2005; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2010). 6 Nonetheless, the classifi-

|

| An expanded classification to include harm-reduction programs is common in the drug control strategies of other countries, including Australia, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. |

cation of interventions into demand reduction and supply reduction is a very helpful heuristic for policy purposes, as well as being written into the legislation under which the Office of National Drug Control Policy operates.

What determines the demand for drugs? Clearly, many different factors play a role: cultural, economic, and social influences are all important. At the individual level, a rich set of correlates have been explored, either in large-scale cross-sectional surveys (such as the National Survey on Drug Use and Health and the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse) or in small-scale longitudinal studies (see, e.g., Wills et al., 2005). Below we briefly summarize the complex findings of those studies.

Less has been done at the population level. It is known that rich western countries differ substantially in the extent of drug use, in ways that do not seem to reflect policy differences. For example, despite the relatively easy access to marijuana in the Netherlands, that nation has a prevalence rate that is in the middle of the pack for Europe, while Britain, despite what may be characterized as a pragmatic and relatively evidence-oriented drug policy, has Europe’s highest rates of cocaine and heroin addiction (European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2007). There is only minimal empirical research that has attempted to explain those differences. Similarly, there is very little known about why epidemics of drug use occur at specific times. In the United States, for example, there is no known reason for the sudden spread of methamphetamine from its long-term West Coast concentration to the Midwest that began in the early 1990s. There are only the most speculative conjectures as to the proximate causes.

A DYNAMIC AND HETEROGENEOUS PROCESS

The committee’s starting point is that drug use is a dynamic phenomenon, both at the individual and community levels. In the United States there is a well-established progression of use of substances for individuals, starting with alcohol or cigarettes (or both) and proceeding through marijuana (at least until recently) possibly to more dangerous and expensive drugs (see, e.g., Golub and Johnson, 2001). Such a progression seems to be a common feature of drug use, although the exact sequence might not apply in other countries and may change over time. For example, cigarettes may lose their status as a gateway drug because of new restrictions on their use. 7 Recently, abuse of prescription drugs has emerged as a possible gateway, with high prevalence rates reported for youth aged 18-25;

|

| In Amsterdam, people can smoke marijuana at indoor cafes but not marijuana mixed with tobacco. |

however, because of limited economic research on this phenomenon, this report’s focus is on completely illegal drugs.

At the population level, there are epidemics, in which, like a fashion good, a new drug becomes popular rapidly in part because of its novelty and then, often just as rapidly, loses its appeal to those who have not tried it. For addictive substances (including marijuana but not hallucinogens, such as LSD), that leaves behind a cohort of users who experimented with the drug and then became habituated to it.

An important and underappreciated element of the demand for illegal drugs is its variation in many dimensions. For example, the demand for marijuana may be much more responsive to price changes than the demand for heroin because fewer of those who use marijuana are drug dependent (Iversen, 2005; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2010). Users who are employed, married, and not poor may be more likely to desist than users of the same drug who are unemployed, not part of an intact household, and poor. There may be differences in the characteristics of demand associated with when the specific drug first became available in a particular community, that is, whether it is early or late in a national drug “epidemic.”

There are also unexplained long-term differences in the drug patterns in cities that are close to each other. In Washington, DC, in 1987 half of all those arrested for a criminal offense (not just for drugs) tested positive for phencyclidine, while in Baltimore, 35 miles away, the drug was almost unknown. Although the Washington rate had fallen to approximately 10 percent in 2009 (District of Columbia Pretrial Services Agency, 2009), it remains far higher than in other cities. More recently, the spread of methamphetamine has shown the same unevenness: in San Antonio only 2.3 percent of arrestees tested positive for methamphetamine in 2002; in Phoenix, the figure was 31.2 percent (National Institute of Justice, 2003). These differences had existed for more than 10 years.

The implication of this heterogeneity is that programs that work for a particular drug, user type, place, or period may be much less effective under other circumstances, which substantially complicates any research task. It is hard to know how general are findings on, say, the effectiveness of a prevention program aimed at methamphetamine use by adolescents in a city where the drug has no history. Will this program also be effective for trying to prevent cocaine use among young adults in cities that have long histories of that drug?

This report does not claim to provide the answers to such ambitious questions. It does intend, however, to equip policy officials and the public to understand what is known and what needs to be done to provide a more sound base for answering them.

Arseneault, L., M. Cannon, J. Witten, and R. Murray. (2004). Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: Examination of the evidence. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184 , 110-117.

Babor, T., J. Caulkins, G. Edwards, D. Foxcroft, K. Humphreys, M.M. Mora, I. Obot, J. Rehm, P. Reuter, R. Room, I. Rossow, and J. Strang. (2010). Drug Policy and the Public Good . New York: Oxford University Press.

Carnevale, J. (2009). Restoring the Integrity of the Office of National Drug Control Policy. Testimony at the hearing on the Office of National Drug Control Policy’s Fiscal Year 2010 National Drug Control Budget and the Policy Priorities of the Office of National Drug Control Policy Under the New Administration. The Domestic Policy Subcommittee of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. May 19, 2009. Available: http://carnevaleassociates.com/Testimony%20of%20John%20Carnevale%20May%2019%20-%20FINAL.pdf [accessed August 2010].

Caulkins, J., and R. Mennefee. (2009). Is objective risk all that matters when it comes to drugs? Journal of Drug Policy Analysis , 2 (1), Art. 1. Available: http://www.bepress.com/jdpa/vol2/iss1/art1/ [accessed August 2010].

District of Columbia Pretrial Services Agency. (2009). PSA’s Electronic Reading Room—FOIA. Available: http://www.dcpsa.gov/foia/foiaERRpsa.htm [accessed May 2009].

European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2007). 2007 Annual Report: The State of the Drug Problem in Europe. Lisbon, Portugal. Available: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/annual-report/2007 [accessed May 2009].

Fergusson, D.M., J.M. Boden, and L.J. Horwood. (2006). Cannabis use and other illicit drug use: Testing the cannabis gateway hypothesis. Addiction, 6 (101), 556-569.

Gallup Poll. (2009). Illegal Drugs . Available: http://www.gallup.com/poll/1657/illegal-drugs.aspx [accessed April 2010].

Golub, A., and B. Johnson. (2001). Variation in youthful risks of progression from alcohol and tobacco to marijuana and to hard drugs across generations. American Journal of Public Health, 91 (2), 225-232.

Iversen, L. (2005). Long-term effects of exposure to cannabis. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 5 (1), 69-72. Available: http://www.safeaccessnow.org/downloads/long%20term%20cannabis%20effects.pdf [accessed July 2010].

National Institute of Justice. (2003). Preliminary Data on Drug Use & Related Matters Among Adult Arrestees & Juvenile Detainees 2002 . Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2010). NIDA InfoFacts: Heroin . Available: http://www.drugabuse.gov/infofacts/heroin.html [accessed August 2010].

National Research Council. (2001). Informing America’s Policy on Illegal Drugs: What We Don’t Know Keeps Hurting Us. Committee on Data and Research for Policy on Illegal Drugs, C.F. Manski, J.V. Pepper, and C.V. Petrie (Eds.). Committee on Law and Justice and Committee on National Statistics. Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Office of National Drug Control Policy. (1993). State and Local Spending on Drug Control Activities . NCJ publication no. 146138. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President.

Office of National Drug Control Policy. (2001). What America’s Users Spend on Illegal Drugs 1988–2000 . W. Rhodes, M. Layne, A.-M. Bruen, P. Johnston, and L. Bechetti. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President.

Pollack, H., P. Reuter., and P. Sevigny. (2010). If Drug Treatment Works So Well, Why Are So Many Drug Users in Prison? Paper presented at the meeting of the National Bureau of Economic Research on Making Crime Control Pay: Cost-Effective Alternatives to Incarceration, July, Berkeley, CA. Available: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c12098.pdf [accessed August 2010].

Trunzo, D., and L. Henderson. (2007). Older Adult Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment: Findings from the Treatment Episode Data Set . Paper presented at the meeting of the American Public Health Association, November 6, Washington, DC. Available: http://apha.confex.com/apha/135am/techprogram/paper_160959.htm [accessed August 2010].

Walsh, J. (2009). Lowering Expectations: Supply Control and the Resilient Cocaine Market. Available: http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/graficos/pdf09/wolareportcocaine.pdf [accessed August 2010].

Wills, T., C. Walker, and J. Resko. (2005). Longitudinal studies of drug use and abuse. In Z. Slobada (Ed.), Epidemiology of Drug Abuse (pp. 177-192). New York: Springer.

This page intentionally left blank.

Despite efforts to reduce drug consumption in the United States over the past 35 years, drugs are just as cheap and available as they have ever been. Cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamines continue to cause great harm in the country, particularly in minority communities in the major cities. Marijuana use remains a part of adolescent development for about half of the country's young people, although there is controversy about the extent of its harm.

Given the persistence of drug demand in the face of lengthy and expensive efforts to control the markets, the National Institute of Justice asked the National Research Council to undertake a study of current research on the demand for drugs in order to help better focus national efforts to reduce that demand.

This study complements the 2003 book, Informing America's Policy on Illegal Drugs by giving more attention to the sources of demand and assessing the potential of demand-side interventions to make a substantial difference to the nation's drug problems. Understanding the Demand for Illegal Drugs therefore focuses tightly on demand models in the field of economics and evaluates the data needs for advancing this relatively undeveloped area of investigation.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

| (1971), (1977), (1986), and numerous articles on law, philosophy, and political and moral theory. �1982 by Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-7525-4 (pbk.) | |

| is available for purchase from Amazon.com please use to order. |