- Publication Recognition

What is a Good H-index?

- 4 minute read

- 362.3K views

Table of Contents

You have finally overcome the exhausting process of a successful paper publication and are just thinking that it’s time to relax for a while. Maybe you are right to do so, but don’t take very long…you see, just like the research process itself, pursuing a career as an author of published works is also about expecting results. In other words, today there are tools that can tell you if your publication(s) is/are impacting the number of people you believed it would (or not). One of the most common tools researchers use is the H-index score.

Knowing how impactful your publications are among your audience is key to defining your individual performance as a researcher and author. This helps the scientific community compare professionals in the same research field (and career length). Although scoring intellectual activities is often an issue of debate, it also brings its own benefits:

- Inside the scientific community: A standardization of researchers’ performances can be useful for comparison between them, within their field of research. For example, H-index scores are commonly used in the recruitment processes for academic positions and taken into consideration when applying for academic or research grants. At the end of the day, the H-index is used as a sign of self-worth for scholars in almost every field of research.

- In an individual point of view: Knowing the impact of your work among the target audience is especially important in the academic world. With careful analysis and the right amount of reflection, the H-index can give you clues and ideas on how to design and implement future projects. If your paper is not being cited as much as you expected, try to find out what the problem might have been. For example, was the research content irrelevant for the audience? Was the selected journal wrong for your paper? Was the text poorly written? For the latter, consider Elsevier’s text editing and translation services in order to improve your chances of being cited by other authors and improving your H-index.

What is my H-index?

Basically, the H-index score is a standard scholarly metric in which the number of published papers, and the number of times their author is cited, is put into relation. The formula is based on the number of papers (H) that have been cited, and how often, compared to those that have not been cited (or cited as much). See the table below as a practical example:

In this case, the researcher scored an H-index of 6, since he has 6 publications that have been cited at least 6 times. The remaining articles, or those that have not yet reached 6 citations, are left aside.

A good H-index score depends not only on a prolific output but also on a large number of citations by other authors. It is important, therefore, that your research reaches a wide audience, preferably one to whom your topic is particularly interesting or relevant, in a clear, high-quality text. Young researchers and inexperienced scholars often look for articles that offer academic security by leaving no room for doubts or misinterpretations.

What is a good H-Index score journal?

Journals also have their own H-Index scores. Publishing in a high H-index journal maximizes your chances of being cited by other authors and, consequently, may improve your own personal H-index score. Some of the “giants” in the highest H-index scores are journals from top universities, like Oxford University, with the highest score being 146, according to Google Scholar.

Knowing the H-index score of journals of interest is useful when searching for the right one to publish your next paper. Even if you are just starting as an author, and you still don’t have your own H-index score, you may want to start in the right place to skyrocket your self-worth.

See below some of the most commonly used databases that help authors find their H-index values:

- Elsevier’s Scopus : Includes Citation Tracker, a feature that shows how often an author has been cited. To this day, it is the largest abstract and citation database of peer-reviewed literature.

- Clarivate Analytics Web of Science : a digital platform that provides the H-index with its Citation Reports feature

- Google Scholar : a growing database that calculates H-index scores for those who have a profile.

Maximize the impact of your research by publishing high-quality articles. A richly edited text with flawless grammar may be all you need to capture the eye of other authors and researchers in your field. With Elsevier, you have the guarantee of excellent output, no matter the topic or your target journal.

Language Editing Services by Elsevier Author Services:

What is a Corresponding Author?

- Manuscript Review

Systematic Review VS Meta-Analysis

You may also like.

How to Make a PowerPoint Presentation of Your Research Paper

How to Submit a Paper for Publication in a Journal

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Explainer: what is an H-index and how is it calculated?

Professor of Organisational Behaviour, Cass Business School, City, University of London

Disclosure statement

Andre Spicer does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

City, University of London provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

A previously obscure scholarly metric has became an item of heated public debate. When it was announced that Bjorn Lomborg, a researcher who is sceptical about the relative importance of climate change, would be heading a research centre at the University of Western Australia, the main retort from most scientists was “just look at the guy’s H-index!”

Many scientists who were opposed to Lomborg’s new research centre pointed out that his H-index score was 3 . Usually, someone appointed to a professorship in the natural sciences would be expected to have an H score about ten times that.

For people outside of academia this measure probably makes little sense. So what exactly is an H-index and why should we use it to judge whether someone should be appointed to lead a research centre?

What is the H-index and how is it calculated?

The H-Index is a numerical indicator of how productive and influential a researcher is. It was invented by Jorge Hirsch in 2005, a physicist at the University of California. Originally, Professor Hirsch wanted to create a numerical indication of the contribution a researcher has made to the field.

At the time, an established measure was raw citation counts. If you wanted to work out how influential a researcher was, you would simply add up the number of times other research papers had cited papers written by that researcher.

Although this was relatively straightforward, researchers quickly discovered a significant problem with this score – you could get a huge citation count through being the scientific equivalent of a one-hit wonder.

If you published one paper that was widely cited and then never published a paper again after that, you would technically be successful. In such situations, outliers would have an undue and even distorting effect on our overall evaluation of a researcher’s contribution.

To rectify this problem, Hirsch suggested another approach for calculating the value of researchers, which he rather immodestly called the H-index (H for Hirsch of course). This is how he explains it:

A scientist has index h if h of his/her Np papers have at least h citations each, and the other (Np−h) papers have no more than h citations each.

To put it in a slightly more simple way - you give an H-index to someone on the basis of the number of papers (H) that have been cited at least H times. For instance, according to Google Scholar, I have an H-index of 28. This is because I have 28 papers that are cited at least 28 times by other research papers. What this means is that a scientist is rewarded for having a range of papers with good levels of citations rather than one or two outliers with very high citations.

It also means that if I want to increase my H-index, it is best to focus on encouraging people to read and cite my papers with more modest citation levels – rather than having them focus on one or two well-known papers which are already widely cited.

The influence of the H-index

While the H-index might have been created for the purpose of evaluating researchers in the area of theoretical physics, its influence has spread much further. The index is routinely used by researchers in a wide range of disciplines to evaluate both themselves and others within their field.

For instance, H-indexes are now a common part of the process of evaluating job applicants for academic positions. They are also used to evaluate applicants for research grants. Some scholars even use them as a sign of self-worth.

Calculating a scholar’s H-index has some distinct advantages. It gives some degree of transparency about the influence they have in the field. This makes it easy for non-experts to evaluate a researcher’s contribution to the field.

If I was sitting on an interview panel in a field that I know nothing about (like theoretical physics), I would find it very difficult to judge the quality of their research. With an H-index, I am given a number that can be used to judge how influential or otherwise the person we are interviewing actually is.

This also has the advantage of taking out many of the idiosyncratic judgements that often cloud our perception of a researcher’s relative merits. If for instance I prefer “salt water” economics to “fresh water” economics, then I am most likely to be positively disposed to hiring the salt water economist and coming up with any argument possible to not accept the fresh water economist.

If however, we are simply given an H-index, then it it becomes possible to assess each scholar in a slightly more objective fashion.

The problems with the H-index

There are some dangers that come with the increasing prevalence of H-scores. It is difficult to compare H-scores across fields. H-scores can often be higher in one field (such economics) than another field (such as literary criticism).

Like any citation metric, H-scores are open to manipulation through practices like self-citation and what one of my old colleagues liked to call “citation soviets” (small circles of people who routinely cite each other’s work).

The H-index also strips out any information about author order. The result is that there is little information about whether you published an article in a top journal on your own or whether you were one member of a huge team.

But perhaps the most worrying thing about the rise of H-scores, or any other measure of research productivity or influence for that matter, is they actually strip out the ideas. They allow us to talk about intellectual endeavour without any reference at all to the actual content.

This can create a very strange academic culture where it is quite possible to discuss academic matters for hours without once mentioning an idea. I have been to meetings where people are perfectly comfortable chatting about the ins and outs of research metrics at great length. But little discussion is had about the actual content of a research project.

As this attitude to research becomes more common, aspirational academics will start to see themselves as H-index entrepreneurs. When this happens, universities will cease to be knowledge creators and instead become metric maximisers.

Events and Communications Coordinator

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

What is the h-index?

- Research Process

In this article, we explain where the h-index comes from and how it is calculated. You will be ready to put the h-index into context and discuss what it means to you as a researcher, where you can find it, and why it is important.

Updated on November 3, 2022

Knowing your h -index is an essential step to measuring the impact your research is having on your field and discipline. In this article, you will learn the basics of the h -index and how it applies to your research career.

You are getting your research out into the world, preprints, presentations, publications. People are reading it, discussing it, citing it. And you know this is important, not only for current projects but also for all those in the future.

How do you measure and share this exciting progress?

With so many metrics used to assess the quality and impact of your research, it can be hard to

tell them apart. The h -index deserves some undivided attention, though. It is often used to rank candidates for grant funding, fellowships and other research positions.

In this article, we will talk about where the h -index comes from and how it is calculated. And with that background, we will be ready to put the h -index into context and discuss what it means to you as a researcher, where you can find it when you need it, and why it is important to seriously consider.

Background of the h -index

J.E. Hirsch first proposed the h -index in 2005 in his article An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output. He argued that two individuals with similar hs would be comparable in terms of their overall scientific impact, even if their total number of papers or their total number of citations were very different (Hirsch, 2005). Making the metric an equalizer of sorts.

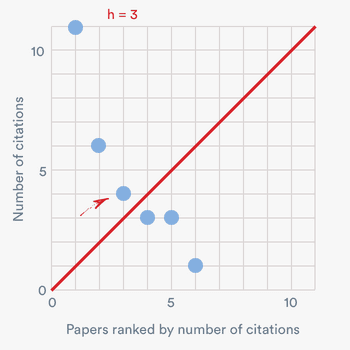

In practice, the total number of citations and papers are plotted on a graph like this (Wikimedia Commons, 2008). The h -index, then, is defined as the maximum value of h such that the given author or journal has published at least h papers that have each been cited at least h times (McDonald, 2005). Making an author's greatest possible h -index limited to their total number of papers. As shown by the green square that is intersected by the dashed line on the graph.

In other words, an author with 1 paper that has 1 or more citations can have a maximum h -index of 1. In the same way, an author with several papers that each have 1 citation would also have a h -index of 1.

How do you calculate the h -index?

We can start by looking at the h -index in the simplest terms. If an author has 10 papers where each has at least 10 citations, then their h -index is 10. If, however, an author has five papers with 12, 6, 5, 2, and 1 citations respectively, then the author's h -index is 3. This is because the author has only three papers with 3 or more citations. So, the h -index of 3 is where the h citations and the h papers would meet at the top corner of the green square in the graph we looked at above.

If you want to calculate an h -index manually, make a table with two columns. In the left column, assign ascending numbers beginning with 1 and going all the way to account for the author's total number of papers. In the right column, arrange the number of citations for the author's papers in descending order, where the biggest number is paired with the 1st paper.

Next, you move down the list until the paper number on the left is greater than the citation number on the right. Draw a line just above this position to look like the table below (MUHC Libraries, 2015). The h -index then equals the paper number just above the line. In this case the h -index is 8 because 8 articles have been cited at least 8 or more times. The remaining articles have been cited 8 times or less.

In this way, the h -index provides a more comprehensive view of the productivity and impact of a researcher's work than the simpler metrics of the total number of papers or the total number of citations. And, at the same time, the h -index simplifies the same information by converting it into one easy to digest number.

h -index tools and resources

While knowing your h -index is useful, gathering all the data and calculating it yourself can be a pain. Fortunately, many of the resources you are already using to promote and track research papers offer convenient tools for generating h -index metrics.

- Google Scholar - Finding h -index in Google Scholar - Ask Us

- Publish or Perish- Results pane from Publish or Perish 4.22 onward

- Web of Science - Tutorial: h -index in Web of Science - Evaluating scholarly publications - LibGuides at Tritonia

- Scopus - Tutorial: h -index in Scopus - Evaluating scholarly publications - LibGuides at Tritonia

- Pure - Pure | The world’s leading RIMS or CRIS | Elsevier Solutions

It is a good idea to periodically check and compare your h -index from each of these resources. Chances are, the results will not match.

Each database calculates the h -index based only on the citations it contains. In the same way, software programs like Publish or Perish and management systems like Pure use a limited amount of citation data.

No single system retrieves and analyzes all citation information from all sources. This results in dissimilar h -index values. The databases also cover different journals over different ranges of years, which makes the h -index results vary.

Looking at how individual sources calculate your h -index and how it changes over time will help you recognize which of these is more accurate for your personal research career, field, and situation.

What is a good h -index?

Just as your h -index may vary from source to source, its weight and value are also on a sliding scale. An h -index number that is considered good in one area of research may only be subpar in another.

This is because every organization, institution, funding group, and hiring committee has its own set of requirements for any given research project or position. So, the idea of an acceptable or competitive h -index will change accordingly.

Many agree, however, that a satisfactory h -index will closely mirror the number of years a person has been working in their field. For example, h -index scores between 3 and 5 are common for new assistant professors, scores between 8 and 12 are standard for promotion to tenured associate professor, and scores between 15 and 20 are appropriate for becoming a full professor (Tetzner, 2021).

This is not a set guideline by any means. Rather a general explanation to use when setting your professional goals. That being said, you need to also stay current with your field's practices regarding the h -index. And, always thoroughly check the h -index requirements for all applications you submit.

What are the pros and cons of the h -index?

Some people appreciate the h -index, some loathe it, and others have no opinion at all. Most who are familiar with the h -index, though, have a healthy level of respect while understanding that, like all metrics, it is imperfect.

Even at the dawn of its creation, Hirsch recognized the following advantages and disadvantages of his h -index (Hirsch, 2005):

- It combines a measure of quantity (publications) and impact (citations).

- It allows us to characterize the scientific output of a researcher with objectivity.

- It performs better than other single-number criteria used to evaluate the scientific output of a researcher (impact factor, total number of documents, total number of citations, citation per paper rate and number of highly cited papers).

- The h -index can be easily obtained by anyone.

- There are inter-field differences in typical h values due to differences among fields in productivity and citation practices.

- The h -index depends on the duration of each scientist's career because the pool of publications and citations increases over time.

- There are also technical limitations, such as the difficulty to obtain the complete output of scientists with very common names, or whether self-citations should be removed or not.

- “A single number can never give more than a rough approximation to an individual's multifaceted profile, and many other factors should be considered in combination in evaluating an individual (Hirsch, 2005).”

Final thoughts

During your research career, there will be many circumstances when you will inevitably have to interact with the h -index. Having a foundation of knowledge before that time comes is key to ensuring that your h -index is an asset and not a liability.

The information in this article will help you start laying the groundwork for clearly understanding the h -index. Where it comes from, how it is calculated, where to find it, and how it impacts your research career. It is one more vital step to ensuring that your valuable research finds its way out into the world.

- Hirsch, J. E. (2005). An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output. PNAS, 102(46), 16569-72. PMC. Retrieved Oct 26, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1283832/

- McDonald, K. (2005, November 8). Physicist Proposes New Way to Rank Scientific Output. Phys.org. Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://phys.org/news/2005-11-physicist-scientific-output.html

- MUHC Libraries. (2015, Jul 01). What's your impact? Calculating your h-index | McGill University Health Centre Libraries. MUHC Libraries. Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://www.muhclibraries.ca/training-and-consulting/guides-and-tutorials/whats-your-impact-calculating-your-h-index/

- Tetzner, R. (2021, September 3). What Is a Good h-Index Required for an Academic Position? Journal-Publishing.com. Retrieved October 27, 2022, from https://www.journal-publishing.com/blog/good-h-index-required-academic-position/

- Wikimedia Commons. (2008, Feb 01). File:h-index-en.svg. Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:h-index-en.svg

Charla Viera, MS

See our "Privacy Policy"

- Research guides

Assessing Article and Author Influence

Finding an author's h-index, the h-index: a brief guide.

This page provides an overview of the H-Index, an attempt to measure the research impact of a scholar. The topics include:

What is the H-Index?

How is the h-index computed, factors to bear in mind.

- Using Harzing's Publish or Publish to Assess the H-Index

Using Web of Science to Assess the H-Index

- H-Index Video

Contemporary H-Index

Selected further reading.

The h-index, created by Jorge E. Hirsch in 2005, is an attempt to measure the research impact of a scholar. In his 2005 article Hirsch put forward "an easily computable index, h, which gives an estimate of the importance, significance, and broad impact of a scientist's cumulative research contributions." He believed "that this index may provide a useful yardstick with which to compare, in an unbiased way, different individuals competing for the same resource when an important evaluation criterion is scientific achievement." There has been much controversy over the value of the h-index, in particular whether its merits outweigh its weaknesses. There has also been much debate concerning the optimal methodology to use in assessing the index. In locating someone's h-index a number of methodologies/databases may be used. Two major ones are ISI's Web of Science and the free Harzing's Publish or Perish which uses Google Scholar data.

An h-index of 20 signifies that a scientist has published 20 articles each of which has been cited at least 20 times. Sometimes the h=index is, arguably, misleading. For example, if a scholar's works have received, say, 10,000 citations he may still have a h-index of only 12 as only 12 of his papers have been cited at least 12 times. This can happen when one of his papers has been cited thousands and thousands of times. So, to have a high h-index one must have published a large number of papers. There have been instances of Nobel Prize winners in scientific fields who have a relatively low h-index. This is due to them having published one or a very small number of extremely influential papers and maybe numerous other papers that were not so important and, consequently, not well cited.

- As citation practices/patterns can vary quite widely across disciplines, it is not advisable to use h-index scores to assess the research impact of personnel in different disciplines.

- The h-index is not very widely used in the Arts and Humanities.

- H-index scores can vary widely depending on the methodology/database used. This is because different methodologies draw upon different citation data. When comparing different people’s H-Index it’s essential to use the same methodology. The h-index does not distinguish the relative contributions of authors in multi-author articles.

- The h-index may vary significantly depending on how long the scholar has been publishing and on the number of articles they’ve published. Older, more prolific scholars will tend to have a higher h-index than younger, less productive ones.

- The h-index can never decrease. This, at times, can be a problem as it does not indicate the decreasing productivity and influence of a scholar.

Using Harzing's Publish or Publish to Assess the H-Index

Publish or Perish utilizes data from Google Scholar. Its software may be downloaded from the Publish or Perish website . A person's h-index located through Publish or Perish is often higher than the same person's index located by means of ISI's Web of Science . This is primarily because the Google Scholar data utilized by Publish or Perish includes a much wider range of sources, e.g. working papers, conference papers, technical reports etc., than does Web of Science . It has often been observed that Web of Science may sometimes produce a more authoritative h-index than Publish or Perish. This tends to be more likely in certain disciplines in the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences.

After you've launched the application, click on "Author impact" on top. Enter the author's name as initial and surname enclosed with quotation marks, e.g. "S Helluy". Then click "Lookup" (top right). You'll see a screen with a listing of S. Helluy's works arranged by number of citations. Above this listing is a smaller panel where one may see the h-index score of 17:

Publish or Perish uses Google Scholar data and these data occasionally split a single paper into multiple entries. This is usually due to incorrect or sloppy referencing of a paper by others, which causes Google Scholar to believe that the referenced works are different. However, you can merge duplicate records in the Publish or Perish results list. You do this by dragging one item and dropping it onto another; the resulting item has a small "double document" icon as illustrated below:

- Alan Marnett (2010). "H-Index: What It Is and How to Find Yours"

- Harzing, Anne-Wil (2008) Reflections on the H-Index .

- Hirsch, J. E. (15 November 2005). "An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output" . PNAS 102 (46): 16569–16572.

- A. M. Petersen, H. E. Stanley, and S. Succi (2011). "Statistical Regularities in the Rank-Citation Profile of Scientists" Nature Scientific Reports 181 : 1–7.

- Williams, Antony (2011). Calculating my H Index With Free Available Tools .

If you are using Clarivate's Web of Science database to assess a h-index, it is important to remember that Web of Science uses only those citations in the journals listed in Web of Science . However, a scholar’s work may be published in journals not covered by Web of Science . It is not possible to add these to the database’s citation report and go towards the h-index. Also, Web of Science only includes citations to journal articles – no books, chapters, working papers etc.). Moreover, Web of Science ’s coverage of journals in the Social Sciences and the Humanities is relatively sparse. This is especially so for the Humanities.

Select the option "Cited Reference Search" (on top). Enter the person’s last name and first initial followed by an asterisk, e.g. Helluy S* If the person always uses a second first name include the second initial followed by an asterisk, e.g. Franklin KT* .

If other authors have the same name, it’s important that you omit their articles. You can use the check boxes to the left of each article to remove individual items that are not by the author you are searching. The “Refine Results” column on the left can also help by limiting to relevant “Organizations – Enhanced”, by “Research Areas”, by “Publication Years”.

When you've determined that all the articles in the list are by the author, S. Helluy , you're searching for click on “Create Citation Report” on the right. The h-index for S. Helluy will be displayed as well as other citation stats.

Notice the two bar charts that graph the number of items published each year and the number of citations received each year.

If you wish to see how the person's h-index has changed over a time period you can use the drop-down menus below to specify a range of years. Web of Science will then re-calculate the h-index using only those articles added for those particular years.

Contending that Hirsch's H-Index does not take into account the "age" of an article, Sidiropoulos et al. (2006) came up with a modification, i.e. the Contemporary H-Index . They argued that though some older scholars may have have been "inactive" for a long period their h-index may still be high since the h-index cannot decline. This may be considered as somewhat unfair to older, senior scholars who continue to produce (if one has published a lot and already has a high h-index it is more and more difficult to incease the index). It may also be seen as unfair to younger brilliant scholars who have had time only to publish a small number of significant articles and consequently have only a low h-index. Hirsch's h-index, it is argued, doesn't distinguish between the different productivity/citations of these different kinds of scholars. The solution of Sidiropoulos et al. is to give weightings to articles according to the year in which they're published. For example, "for an article published during the current year, its citations account four times. For an article published 4 year ago, its citations account only one time. For an article published 6 year ago, its citations account 4/6 times, and so on. This way, an old article gradually loses its 'value', even if it still gets citations." Thus, more emphasis is given to recent articles thereby favoring the h-index of scholars who are actively publishing.

One of the easiest ways to obtain someone's contemporary h-index, or "hc-index", is to use Harzing's Publish or Perish software.

- << Previous: AltMetrics

- Next: "Times Cited" >>

- Last Updated: Mar 20, 2024 11:33 AM

- Subjects: General

- Tags: altmetrics , author ID , h-index , impact factor

Reference management. Clean and simple.

What is the h-index?

A simple definition of the h-index

Step-by-step outline: how to calculate your h-index, why it is important for your career to know about the h-index, can all your academic achievements be summarized by a single number, frequently asked questions about h-index, related articles.

An h-index is a rough summary measure of a researcher’s productivity and impact. Productivity is quantified by the number of papers, and impact by the number of citations the researchers' publications have received.

The h-index can be useful for identifying the centrality of certain researchers as researchers with a higher h-index will, in general, have produced more work that is considered important by their peers.

The h-index was originally defined by J. E. Hirsch in a Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences article as the number of papers with citation number ≥ h . An h-index of 3 hence means that the author has published at least three articles, of which each has been cited at least three times.

The h-index can also simply be determined by charting the article's citation counts. The h-index is then determined by the interception of the chart's diagonal with the citation data. In this case, there are 3 papers that are above the diagonal, and hence the h-index is 3.

The definition of the h-index comes with quite a few desirable features:

- First, it is relatively unaffected by outliers. If e.g. the top-ranked article had been cited 1,000 times, this would not change the h-index.

- Second, the h-index will generally only increase if the researcher continues to produce good work. The h-index would increase to 4 if another paper was added with 4 citations, but would not increase if papers were added with fewer citations.

- Third, the h-index will never be greater than the number of papers the author has published; to have an h-index of 20, the author must have published at least 20 articles which have each been cited at least 20 times.

- Step 1 : List all your published articles in a table.

- Step 2 : For each article gather the number of how often it has been cited.

- Step 3 : Rank the papers by the number of times they have been cited.

- Step 4 : The h-index can now be inferred by finding the entry at which the rank in the list is greater than the number of citations.

Here is an example of a table where articles have been ranked by their citation count and the h-index has been inferred to be 3.

Luckily, there are services like Scopus , Web of Science , and Google Scholar that can do the heavy lifting and automatically provide the citation count data and calculate the h-index.

The h-index is not something that needs to be calculated on a daily basis, but it's good to know where you are for several reasons. First, climbing the h-index ladder is something worth celebrating. If it's worth opening a bottle of champagne or just getting a cafe latte, that's up to you, but seriously take your time to celebrate this achievement (there aren't that many in academia). But more importantly, the h-index is one of the measures funding agencies or the university's hiring committee calculate when you apply for a grant or a position. Given the often huge number of applications, the h-index is calculated in order to rank candidates and apply a pre-filter.

Of course, funding agencies and hiring committees do use tools for calculating the h-index, and so can you.

It is important to note that depending on the underlying data that these services have collected, your h-index might be different. Let's have a look at the h-index of the well-known physicist Stephen W. Hawking to illustrate it:

So, if you are aware of a number of citations of your work that are not listed in these databases, e.g. because they are in conference proceedings not indexed in these databases, then please state that in your application. It might give your h-index an extra boost.

➡️ Learn more: What is a good h-index?

Definitely not! People are aware of this, and there have been many attempts to address particular shortcomings of the h-index, but in the end, it's just another number that is meant to emphasize or de-emphasize certain aspects of the h-index. Anyway, you have to know the rules in order to play the game, and you have to know the rules in order to change them. If you feel that your h-index does not properly reflect your academic achievements, then be proactive and mention it in your application!

An h-index is a rough summary measure of a researcher’s productivity and impact . Productivity is quantified by the number of papers, and impact by the number of citations the researchers' publications have received.

Google Scholar can automatically calculate your h-index, read our guide How to calculate your h-index on Google Scholar for further instructions.

Even though Scopus needs to crunch millions of citations to find the h-index, the look-up is pretty fast. Read our guide How to calculate your h-index using Scopus for further instructions.

Web of Science is a database that has compiled millions of articles and citations. This data can be used to calculate all sorts of bibliographic metrics including an h-index. Read our guide How to use Web of Science to calculate your h-index for further instructions.

The h-index is not something that needs to be calculated on a daily basis, but it's good to know where you are for several reasons. First, climbing the h-index ladder is something worth celebrating. But more importantly, the h-index is one of the measures funding agencies or the university's hiring committee calculate when you apply for a grant or a position. Given the often huge number of applications, the h-index is calculated in order to rank candidates and apply a pre-filter.

- Library Hours

- (314) 362-7080

- [email protected]

- Library Website

- Electronic Books & Journals

- Database Directory

- Catalog Home

- Library Home

Tools for Authors: What is the h index?

- Preparing for Publication

- Selecting a Journal for Publication

- Finding Collaborators

- Responsible Conduct of Research

- Tracking Your Work

- Enhancing Your Impact

- Establishing Your Author Profile

What is the h index?

- My Bibliography

- NIH Biosketch

- About the Library

The h index was proposed by J.E. Hirsch in 2005 and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America . [i] The h index is a quantitative metric based on analysis of publication data using publications and citations to provide “an estimate of the importance, significance, and broad impact of a scientist’s cumulative research contributions .” [ii] According to Hirsch, the h index is defined as: “ A scientist has index h if h of his or her Np papers have at least h citations each and the other (Np – h) papers have ≤h citations each .”

As an example, an h index of 10 means that among all publications by one author, 10 of these publications have received at least 10 citations each.

Hirsch argues that the h index is preferable to other single-number criteria, such as the total number of papers, the total number of citations and citations per paper. However, Hirsch includes several caveats:

- A single number can never give more than a rough approximation to an individual’s multifaceted profile;

- Other factors should be considered in combination in evaluating an individual;

- There will be differences in typical h values in different fields, determined in part by the average number of references in a paper in the field, the average number of papers produced by each scientist in the field, and the size (number of scientists) of the field; and

- For an author with a relatively low h that has a few seminal papers with extraordinarily high citation counts, the h index will not fully reflect that scientist’s accomplishments. [iii]

Since Hirsch introduced the h index in 2005, this measure of academic impact has garnered widespread interest as well as proposals for other indices based on analyses of publication data such as the g index, h (2) index, m quotient, r index, to name a few.

Several commonly used databases, such as Elsevier’s Scopus , Clarivate Analytics’ Web of Science , and Google Scholar provide h index values for authors.

[i] Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 November 15; 102(46): 16569–16572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507655102

[ii] Ibid. p. 16569.

[iii] Ibid. p. 16571

Resources to Find the h index

- Google Scholar Google Scholar provides the h index for authors who have created a profile.

- Publish or Perish Publish or Perish is a software program that retrieves and analyzes academic citations from Google Scholar and provides the h index among other metrics. Publish or Perish is handy for obtaining the h index for authors who do not have a Google Scholar profile.

- Scopus Scopus provides a Citation Tracker feature that allows for generation of a Citation Overview chart to generate a h index for publications and citations from 1970 to current. The feature also allows for removal of self-citations from the overall citation counts.

- Web of Science Core Collection Web of Science allows for generation of the h index for publications and citations from 1970 to current using the "Create Citation Report" feature.

Understanding the h index

Do You Need an h index Report?

Do you need an h index report.

We provide h index reports (Scopus and/or Web of Science) to members of the Washington University in St. Louis community.

Contact Amy Suiter to request a report.

Strengths and Shortcomings

Strengths of the h index

- The h index is a metric for evaluating the cumulative impact of an author’s scholarly output and performance; measures quantity with quality by comparing publications to citations.

- The h index corrects for the disproportionate weight of highly cited publications or publications that have not yet been cited.

- Several resources automatically calculate the h index as part of citation reports for authors.

Shortcomings of the h index

- The h index is a metric to assess the entire body of scholarly output by an author; not intended for a specific timeframe.

- The h index is insensitive to publications that are rarely cited such as meeting abstracts and to publications that are frequently cited such as reviews.

- Author name variant issues and multiple versions of the same work pose challenges in establishing accurate citation data for a specific author.

- The h index does not provide the context of the citations.

- The h index is not considered a universal metric as it is difficult to compare authors of different seniority or disciplines. Young investigators are at a disadvantage and academic disciplines vary in the average number of publications, references and citations.

- Self-citations or gratuitous citations among colleagues can skew the h index.

- The h index will vary among resources depending on the publication data that is included in the calculation of the index.

- The h index disregards author ranking and co-author characteristics on publications.

- There are instances of “paradoxical situations” for authors who have the same number of publications, with varying citation counts, but have the same h index. As an example, Author A has eight publications which have been cited a total of 338 times and Author B also has eight publications which have been cited a total of 28 times. Author A and Author B have the same h index of 5 but Author A has a higher citation rate than Author B. See Balaban, AT. 2012. Positive and negative aspects of citation indices and journal impact factors. Scientometrics. DOI: 10.1007/s11192-102-0637-5

Is There an Alternative to the h index?: The m value

The m value is a correction of the h index for time (m = h/y). According to Hirsch, m is an “ indicator of the successfulness of a scientist ” and can be used to compare scientists of different seniority. The m value can be seen as an indicator for “scientific quality” with the advantage (as compared to the h index) that the m value is corrected for career length.

What are the Ranges?

Per Hirsch:

- h index of 20 after 20 years of scientific activity, characterizes a successful scientist

- h index of 40 after 20 years of scientific activity, characterizes outstanding scientists, likely to be found only at the top universities or major research laboratories.

- h index of 60 after 20 years, or 90 after 30 years, characterizes truly unique individuals.

- h index of 15-20, fellowship in the National Physical Society.

- h index of 45 or higher, membership in the National Academy of Sciences.

Other works that discuss the h index in comparison to various medical specialties are noted here .

- << Previous: Establishing Your Author Profile

- Next: NCBI Tools >>

- Last Updated: Mar 21, 2024 7:07 PM

- URL: https://beckerguides.wustl.edu/authors

Measuring your research impact: H-Index

Getting Started

Journal Citation Reports (JCR)

Eigenfactor and Article Influence

Scimago Journal and Country Rank

Google Scholar Metrics

Web of Science Citation Tools

Google Scholar Citations

PLoS Article-Level Metrics

Publish or Perish

- Author disambiguation

- Broadening your impact

Table of Contents

Author Impact

Journal Impact

Tracking and Measuring Your Impact

Author Disambiguation

Broadening Your Impact

Other H-Index Resources

- An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output This is the original paper by J.E. Hirsch proposing and describing the H-index.

H-Index in Web of Science

The Web of Science uses the H-Index to quantify research output by measuring author productivity and impact.

H-Index = number of papers ( h ) with a citation number ≥ h .

Example: a scientist with an H-Index of 37 has 37 papers cited at least 37 times.

Advantages of the H-Index:

- Allows for direct comparisons within disciplines

- Measures quantity and impact by a single value.

Disadvantages of the H-Index:

- Does not give an accurate measure for early-career researchers

- Calculated by using only articles that are indexed in Web of Science. If a researcher publishes an article in a journal that is not indexed by Web of Science, the article as well as any citations to it will not be included in the H-Index calculation.

Tools for measuring H-Index:

- Web of Science

- Google Scholar

This short clip helps to explain the limitations of the H-Index for early-career scientists:

- << Previous: Author Impact

- Next: G-Index >>

- Last Updated: Dec 7, 2022 1:18 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/impact

Calculate your h-index

What is the h-index, find your h-index, metrics, impact and engagement.

Use metrics to provide evidence of:

- engagement with your research, and

- the impact of your research.

Reusing content from this guide

Attribute our work under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The h-index is a measure of the number of publications published (productivity), as well as how often they are cited .

h-index = the number of publications with a citation number greater than or equal to h.

For example, 15 publications cited 15 times or more, is a h-index of 15.

Read more about the h-index, first proposed by J.E. Hirsch, as An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output .

- Do an author search for yourself in Scopus

- Click on your name to display your number of publications, citations and h-index.

Google Scholar

- Create a Google Scholar Citations Profile

- Make sure your publications are listed.

Web of Science

Create a citation report of your publications that will display your h-index in Web of Science .

Watch Using Web of Science to find your publications and track record metrics

h-index tips

- Citation patterns vary across disciplines . For example, h-indexes in Medicine are much higher than in Mathematics

- h-indexes are dependent on the coverage and related citations in the database. Always provide the data source and date along with the h-index

- h-indexes do not account for different career stages

- Your h-index changes over time . Recalculate it each time you include it in an application

Provide additional information about your metrics when talking about your h-index.

Example statement

A statement about your h-index could follow this format:

"My h-index, based on papers indexed in Web of Science, is 10. It has been 5 years since I finished my PhD. I have 4 papers (A, B, C, D) with more than 20 citations and 1 paper (E) with 29 citations (Web of Science, 05/08/19). I also have an additional 3 papers not indexed by WoS, with 29 citations based on Scopus data (01/12/20)"

Other indices

- i10 index calculation includes the number of papers with at least 10 citations

- g-index modification of the h-index to give more weight to highly cited papers

- m-Quotient accounts for career length, the h-index divided by the number of years since an author's first publication

- h-index and Variants overview of various indices, including a look at the advantages and disadvantages

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 10:32 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.uq.edu.au/for-researchers/h-index

- Maps & Floorplans

- Libraries A-Z

- Ellis Library (main)

- Engineering Library

- Geological Sciences

- Journalism Library

- Law Library

- Mathematical Sciences

- MU Digital Collections

- Veterinary Medical

- More Libraries...

- Instructional Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Guides

- Schedule a Library Class

- Class Assessment Forms

- Recordings & Tutorials

- Research & Writing Help

- More class resources

- Places to Study

- Borrow, Request & Renew

- Call Numbers

- Computers, Printers, Scanners & Software

- Digital Media Lab

- Equipment Lending: Laptops, cameras, etc.

- Subject Librarians

- Writing Tutors

- More In the Library...

- Undergraduate Students

- Graduate Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Researcher Support

- Distance Learners

- International Students

- More Services for...

- View my MU Libraries Account (login & click on My Library Account)

- View my MOBIUS Checkouts

- Renew my Books (login & click on My Loans)

- Place a Hold on a Book

- Request Books from Depository

- View my ILL@MU Account

- Set Up Alerts in Databases

- More Account Information...

Measuring Research Impact and Quality

- Times cited counts

- h-index for resesarchers-definition

h-index for journals

H-index for institutions, computing your own h-index, ways to increase your h-index, limitations of the h-index, variations of the h-index.

- Using Scopus to find a researcher's h-index

- Additional resources for finding a researcher's h-index

- Journal Impact Factor & other journal rankings

- Journal acceptance rates

- Altmetrics This link opens in a new window

- Impact by discipline

- Researcher Profiles

h-index for researchers-definition

- The h-index is a measure used to indicate the impact and productivity of a researcher based on how often his/her publications have been cited.

- The physicist, Jorge E. Hirsch, provides the following definition for the h-index: A scientist has index h if h of his/her N p papers have at least h citations each, and the other (N p − h) papers have no more than h citations each. (Hirsch, JE (15 November 2005) PNAS 102 (46) 16569-16572)

- The h -index is based on the highest number of papers written by the author that have had at least the same number of citations.

- A researcher with an h-index of 6 has published six papers that have been cited at least six times by other scholars. This researcher may have published more than six papers, but only six of them have been cited six or more times.

Whether or not a h-index is considered strong, weak or average depends on the researcher's field of study and how long they have been active. The h-index of an individual should be considered in the context of the h-indices of equivalent researchers in the same field of study.

Definition : The h-index of a publication is the largest number h such that at least h articles in that publication were cited at least h times each. For example, a journal with a h-index of 20 has published 20 articles that have been cited 20 or more times.

Available from:

- SJR (Scimago Journal & Country Rank)

Whether or not a h-index is considered strong, weak or average depends on the discipline the journal covers and how long it has published. The h-index of a journal should be considered in the context of the h-indices of other journals in similar disciplines.

Definition : The h-index of an institution is the largest number h such that at least h articles published by researchers at the institution were cited at least h times each. For example, if an institution has a h-index of 200 it's researchers have published 200 articles that have been cited 200 or more times.

Available from: exaly

In a spreadsheet, list the number of times each of your publications has been cited by other scholars.

Sort the spreadsheet in descending order by the number of times each publication is cited. Then start counting down until the article number is equal to or not greater than the times cited.

Article Times Cited

1 50

2 15

3 12

4 10

5 8

6 7 == =>h index is 6

7 5

8 1

How to successfully boost your h-index (enago academy, 2019)

Glänzel, Wolfgang On the Opportunities and Limitations of the H-index. , 2006

- h -index based upon data from the last 5 years

- i-10 index is the number of articles by an author that have at least ten citations.

- i-10 index was created by Google Scholar .

- Used to compare researchers with different lengths of publication history

- m-index = ___________ h-index _______________ # of years since author’s 1 st publication

Using Scopus to find an researcher's h-index

Additional resources for finding a researcher's h-index.

Web of Science Core Collection or Web of Science All Databases

- Perform an author search

- Create a citation report for that author.

- The h-index will be listed in the report.

Set up your author profile in the following three resources. Each resource will compute your h-index. Your h-index may vary since each of these sites collects data from different resources.

- Google Scholar Citations Computes h-index based on publications and cited references in Google Scholar .

- Researcher ID

- Computes h-index based on publications and cited references in the last 20 years of Web of Science .

- << Previous: Times cited counts

- Next: Journal Impact Factor & other journal rankings >>

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2024 2:18 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.missouri.edu/impact

We want to hear from you! Fill out the Library's User Survey and enter to win.

Calculate Your Academic Footprint: Your H-Index

- Get Started

- Author Profiles

- Find Publications (Steps 1-2)

- Track Citations (Steps 3-5)

- Count Citations (Steps 6-10)

- Your H-Index

What is an H-Index?

The h-index captures research output based on the total number of publications and the total number of citations to those works, providing a focused snapshot of an individual’s research performance. Example: If a researcher has 15 papers, each of which has at least 15 citations, their h-index is 15.

- Comparing researchers of similar career length.

- Comparing researchers in a similar field, subject, or Department, and who publish in the same journal categories.

- Obtaining a focused snapshot of a researcher’s performance.

Not Useful For

- Comparing researchers from different fields, disciplines, or subjects.

- Assessing fields, departments, and subjects where research output is typically books or conference proceedings as they are not well represented by databases providing h-indices.

1 Working Group on Bibliometrics. (2016). Measuring Research Output Through Bibliometrics. University of Waterloo. Retrieved from https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/bitstream/handle/10012/10323/Bibliometrics%20White%20Paper%20 2016%2 0Final_March2016.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y

2 Alakangas, S. & Warburton, J. Research impact: h-index. The University of Melbourne. Retrieved from http://unimelb.libguides.com/c.php?g=402744&p=2740739

Calculate Manually

To manually calculate your h-index, organize articles in descending order, based on the number of times they have been cited.

In the below example, an author has 8 papers that have been cited 33, 30, 20, 15, 7, 6, 5 and 4 times. This tells us that the author's h-index is 6.

- An h-index of 6 means that this author has published at least 6 papers that have each received at least 6 citations.

More context:

- The first paper has been cited 33 times, and gives us a 1 (there is one paper that has been cited at least once).

- The second paper has been cited 30 times, and gives us a 2 (there are two papers that have been cited at least twice).

- The third paper gives us a 3 and all the way up to 6 with the sixth highest paper.

- The final two papers have no effect in this case as they have been cited less than six times (Ireland, MacDonald & Stirling, 2012).

1 Ireland, T., MacDonald, K., & Stirling, P. (2012). The h-index: What is it, how do we determine it, and how can we keep up with it? In A. Tokar, M. Beurskens, S. Keuneke, M. Mahrt, I. Peters, C. Puschmann, T. van Treeck, & K. Weller (Eds.), Science and the internet (pp. 237-247). D ü sseldorf University Press.

Calculate Using Databases

- Given Scopus and Web of Science 's citation-tracking functionality, they can also calculate an individual’s h-index based on content in their particular databases.

- Likewise, Google Scholar collects citations and calculates an author's h-index via the Google Scholar Citations Profile feature.

Each database may determine a different h-index for the same individual as the content in each database is unique and different.

- << Previous: Count Citations (Steps 6-10)

- Last Updated: Oct 5, 2023 7:37 AM

- URL: https://subjectguides.uwaterloo.ca/calculate-academic-footprint

Research guides by subject

Course reserves

My library account

Book a study room

News and events

Work for the library

Support the library

We want to hear from you. You're viewing the newest version of the Library's website. Please send us your feedback !

- Contact Waterloo

- Maps & Directions

- Accessibility

Research Impact and Author Profiles

- Journal Level Impact

- Author Level Impact (H-index)

- Article Level Impact

- Researcher Profiles

- Populate your ORCID profile

- ORCID settings

- ORCID & SciENcv

- Access to University of Toronto Libraries

- Report a problem, or give us feedback

What is the H-index?

- The H-index is a measure of an individual's impact on the research community based upon the number of papers published and the number of citations these papers have received.

Image source: h -index from a plot of decreasing citations for numbered papers , Public Domain

The index was first proposed by J. E. Hirsch in 2005 and is defined as:

A scientist has index h if h of his/her Np papers have at least h citations each, and the other (Np-h) papers have no more than h citations each. As an example, a researcher with an H-index of 15 has (of their total number of publications) 15 papers which have been cited at least 15 times each.

An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output

J.E. Hirsch's original article in which the h-index was proposed, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005; 102(46):16569-16572.

Limitations and considerations

There are a number of limitations and cautions to be taken into account when using the H-index. These include:

- Academic disciplines differ in the average number of references per paper and the average number of papers published by each author. The length of the academic career will impact the number of papers published and the amount of time papers have had to be cited. The H-index is therefore a less appropriate measure for junior academics.

- There are different patterns of co-authorship in different disciplines. Individual highly cited papers may not be accurately reflected in an H-index.

Calculating Your H-index

The H-index can be calculated using the University of Toronto Library-subscribed databases Web of Science or Scopus , using Scoups free author lookup , or also using the My Citations feature of Google Scholar or the freely downloadable program Publish or Perish , which also takes its citation information from Google Scholar.

However if you wish to create a true H-index based on all unique citations to your publications from all sources, you will need to calculate it manually. The fewer papers you have the more significant each citation becomes in terms of calculating your H-index. Please contact Information Specialists for more information on this process.

Tools for Determining H-Index :

Scopus provides citation tracking and a number of other visualization and analysis tools. Scopus is particularly useful for citations in the Sciences

Steps:

- Start with author search , select your name (you may appear more than once)

- Show documents

- Add to list

- Search and add missing publications to list, if necessary

- When this temporary list is complete, view list, select all

- View citation overview. This will give you your career h-index. The date range is for the graph only!

- To calculate your 3, 4, or 5 year h-index, go back to your list and select the appropriate years of publication i.e. for last 3 years, choose publications from 2016, 2015, 2014, (2013 ) and view citation overview

Web of Science tracks citations across the Sciences, Social Sciences, and Humanities, and includes conference proceedings as well. The Web of Science is particularly useful for citations in the Sciences.

- Choose author search from the drop-down menu, fill in the details. If you’ve published under variations of your name (e.g. with and without your middle initial, be sure to search on author variant name.

- View author sets , select yours, add to marked list

- View marked records , scroll down to see publications, create citation report

Google Scholar is useful for finding citations in books, grey literature, government and legal publications, and non-English resources. Google Scholar also indexes journals in the Sciences, Social Sciences, and Humanities, though the scope of this is unknown.

- Follow the steps to create your Google Scholar “My Citations” author profile and it will generate your h-index.

- The 5 year h-index calculates your score from citations made within the last 5 years to all of your publications. Note that Web of Science and Scopus calculates the 5-year h-index from the citations to the articles you have published over the last 5 years.

If you do not have a "My Citations" Profile, you can download the Publish or Perish software to calculate your Google Scholar h-index.

Read more about the H-index:

- Reflections on the h-index

A commentary on the h-index by Professor Ann-Wil Harzing of the University of Melbourne (2008). Also discusses other indicies used to calculate researcher impact.

- << Previous: Journal Level Impact

- Next: Article Level Impact >>

- Last Updated: Jul 31, 2023 1:09 PM

- URL: https://guides.hsict.library.utoronto.ca/SMH/impact

Do researchers know what the h-index is? And how do they estimate its importance?

- Open access

- Published: 26 April 2021

- Volume 126 , pages 5489–5508, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Pantea Kamrani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8880-8105 1 ,

- Isabelle Dorsch ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7391-5189 1 &

- Wolfgang G. Stock ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2697-3225 1 , 2

9947 Accesses

5 Citations

27 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The h-index is a widely used scientometric indicator on the researcher level working with a simple combination of publication and citation counts. In this article, we pursue two goals, namely the collection of empirical data about researchers’ personal estimations of the importance of the h-index for themselves as well as for their academic disciplines, and on the researchers’ concrete knowledge on the h-index and the way of its calculation. We worked with an online survey (including a knowledge test on the calculation of the h-index), which was finished by 1081 German university professors. We distinguished between the results for all participants, and, additionally, the results by gender, generation, and field of knowledge. We found a clear binary division between the academic knowledge fields: For the sciences and medicine the h-index is important for the researchers themselves and for their disciplines, while for the humanities and social sciences, economics, and law the h-index is considerably less important. Two fifths of the professors do not know details on the h-index or wrongly deem to know what the h-index is and failed our test. The researchers’ knowledge on the h-index is much smaller in the academic branches of the humanities and the social sciences. As the h-index is important for many researchers and as not all researchers are very knowledgeable about this author-specific indicator, it seems to be necessary to make researchers more aware of scholarly metrics literacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Multiple versions of the h-index: cautionary use for formal academic purposes

Rejoinder to “multiple versions of the h-index: cautionary use for formal academic purposes”.

Dispersion measures for h-index: a study of the Brazilian researchers in the field of mathematics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2005, Hirsch introduced his famous h-index. It combines two important measures of scientometrics, namely the publication count of a researcher (as an indicator for his or her research productivity) and the citation count of those publications (as an indicator for his or her research impact). Hirsch ( 2005 , p. 1569) defines, “A scientist has index h if h of his or her N p papers have at least h citations each and the other ( N p – h ) papers have < h citations each.” If a researcher has written 100 articles, for instance, 20 of these having been cited at least 20 times and the other 80 less than that, then the researcher’s h-index will be 20 (Stock and Stock 2013 , p. 382). Following Hirsch, the h-index “gives an estimate of the importance, significance, and broad impact of a scientist’s cumulative research contribution” (Hirsch 2005 , p. 16,572). Hirsch ( 2007 ) assumed that his h-index may predict researchers’ future achievements. Looking at this in retro-perspective, Hirsch had hoped to create an “objective measure of scientific achievement” (Hirsch 2020 , p. 4) but also starts to believe that this could be the opposite. Indeed, it became a measure of scientific achievement, however a very questionable one.

Also in 2005, Hirsch derives the m-index with the researcher’s “research age” in mind. Let the number of years after a researcher’s first publication be t p . The m-index is the quotient of the researcher’s h-index and her or his research age: m p = h p / t p (Hirsch 2005 , p. 16,571). An m -value of 2 would mean, for example, that a researcher has reached an h-value of 20 after 10 research years. Meanwhile, the h-index is strongly wired in our scientific system. It became one of the “standard indicators” in scientific information services and can be found on many general scientific bibliographic databases. Besides, it is used in various contexts and generated a lot of research and discussions. This indicator is used or rather misused—dependent on the way of seeing—in decisions about researchers’ career paths, e.g. as part of academics’ evaluation concerning awards, funding allocations, promotion, and tenure (Ding et al. 2020 ; Dinis-Oliveira 2019 ; Haustein and Larivière 2015 ; Kelly and Jennions 2006 ). For Jappe ( 2020 , p. 13), one of the arguments for the use of the h-index in evaluation studies is its “robustness with regards to incomplete publication and citation data.” Contrary, the index is well-known for its inconsistencies, incapability for comparisons between researchers with different career stages, and missing field normalization (Costas and Bordons 2007 ; Waltman and van Eck 2012 ). There already exist various advantages and disadvantages lists on the h-index (e.g. Rousseau et al. 2018 ). And it is still questionable what the h-index underlying concept represents, due to its conflation of the two concepts’ productivity and impact resulting in one single number (Sugimoto and Larivière, 2018 ).

It is easy to identify lots of variants of the h-index concerning both, the basis of the data as well as the concrete formula of calculation. Working with the numbers of publications and their citations, there are the data based upon the leading general bibliographical information services Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, Google Scholar, and, additionally, on ResearchGate (da Silva and Dobranszki 2018 ); working with publication numbers and the number of the publications’ reads, there are data based upon Mendeley (Askeridis 2018 ). Depending of an author’s visibility on an information service (Dorsch 2017 ), we see different values for the h-indices for WoS, Scopus, and Google Scholar (Bar-Ilan 2008 ), mostly following the inequation h( R ) WoS < h( R ) Scopus < h( R ) Google Scholar for a given researcher R (Dorsch et al. 2018 ). Having in mind that WoS consists of many databases (Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Science Citation Index, Arts & Humanities Citation Index, Emerging Sources Citation Index, Book Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index, etc.) and that libraries not always provide access to all (and not to all years) it is no surprise that we will find different h-indices on WoS depending on the subscribed sources and years (Hu et al. 2020 ).

After Hirsch’s publication of the two initial formulas (i.e. the h-index and the time-adjusted m-index) many scientists felt required to produce similar, but only slightly mathematically modified formulas not leading to brand-new scientific insights (Alonso et al. 2009 ; Bornmann et al. 2008 ; Jan and Ahmad 2020 ), as there are high correlations between the values of the variants (Bornmann et al. 2011 ).

How do researchers estimate the importance of the h-index? Do they really know the concrete definition and its formula? In a survey for Springer Nature ( N = 2734 authors of Springer Nature and Biomed Central), Penny ( 2016 , slide 22) found that 67% of the asked scientists use the h-index and further 22% are aware of it but have not used it before; however, there are 10% of respondents who do not know what the h-index is. Rousseau and Rousseau ( 2017 ) asked members of the International Association of Agricultural Economists and gathered 138 answers. Here, more than two-fifth of all questionees did not know what the h-index is (Rousseau and Rousseau 2017 , p. 481). Among Taiwanese researchers ( n = 417) 28.78% self-reported to have heard about the h-index and fully understood the indicator, whereas 22.06% never heard about it. The remaining stated to hear about it and did not know its content or only some aspects (Chen and Lin 2018 ). For academics in Ireland ( n = 19) “journal impact factor, h-index, and RG scores” are familiar concepts, but “the majority cannot tell how these metrics are calculated or what they represent” (Ma and Ladisch 2019 , p. 214). Likewise, the interviewed academics ( n = 9) could name “more intricate metrics like h-index or Journal Impact Factor, [but] were barely able to explain correctly how these indicators are calculated” (Lemke et al. 2019 , p. 11). The knowledge about scientometric indicators in general “is quite heterogeneous among researchers,” Rousseau and Rousseau ( 2017 , p. 482) state. This is confirmed by further studies on the familiarity, perception or usage of research evaluation metrics in general (Aksnes and Rip 2009 ; Derrick and Gillespie 2013 ; Haddow and Hammarfelt 2019 ; Hammarfelt and Haddow 2018 ).

In a blog post, Tetzner ( 2019 ) speculates on concrete numbers of a “good” h-index for academic positions. Accordingly, an h-index between 3 and 5 is good for a new assistant professor, an index between 8 and 12 for a tenured associate professor, and, finally, an index of more than 15 for a full professor. However, these numbers are gross generalizations without a sound empirical foundation. As our data are from Germany, the question arises: What kinds of tools do German funders, universities, etc. use for research evaluation? Unfortunately, there are only few publications on this topic. For scientists at German universities, bibliometric indicators (including the h-index and the impact factor) are important or very important for scientific reputation for more than 55% of the questionees (Neufeld and Johann 2016 , p.136). Those indicators have also relevance or even great relevance concerning hiring on academic positions in the estimation of more than 40% of the respondents (Neufeld and Johann 2016 , p.129). In a ranking of aspects of reputation of medical scientists, the h-index takes rank 7 (with a mean value of 3.4 with 5 being the best one) out of 17 evaluation criteria. Top-ranked indicators are the reputation of the journals of the scientists’ publications (4.1), the scientists’ citations (4.0), and their publication amount (3.7) (Krempkow et al. 2011 , p. 37). For hiring of psychology professors in Germany, the h-index had factual relevance for the tenure decision with a mean value of 3.64 (on a six-point scale) and ranks on position 12 out of more than 40 criteria for professorship (Abele-Brehm and Bühner 2016 ). Here, the number of peer-reviewed publications is top-ranked (mean value of 5.11). Obviously, these few studies highlight that the h-index indeed has relevance for research evaluation in Germany next to publication and citation numbers.

What is still a research desideratum is an in-depth description of researchers’ personal estimations on the h-index and an analysis of possible differences concerning researchers’ generation, their gender, and the discipline.

What is about the researchers’ state of knowledge on the h-index? Of course, we may ask, “What’s your knowledge on the h-index? Estimate on a scale from 1 to 5!” But personal estimations are subjective and do not substitute a test of knowledge (Kruger and Dunning 1999 ). Knowledge tests on researchers’ state of knowledge concerning the h-index are—to our best knowledge—a research desideratum, too.

In this article, we pursue two goals, namely on the one hand—similar to Buela-Casal and Zych ( 2012 ) on the impact factor—the collection of data about researchers’ personal estimations of the importance of the h-index for themselves as well as their discipline, and on the other hand data on the researchers’ concrete knowledge on the h-index and the way of its calculation. In short, these are our research questions:

RQ1: How do researchers estimate the importance of the h-index?

RQ2: What is the researchers’ knowledge on the h-index?

In order to answer RQ1, we asked researchers on their personal opinions; to answer RQ2, we additionally performed a test of their knowledge.

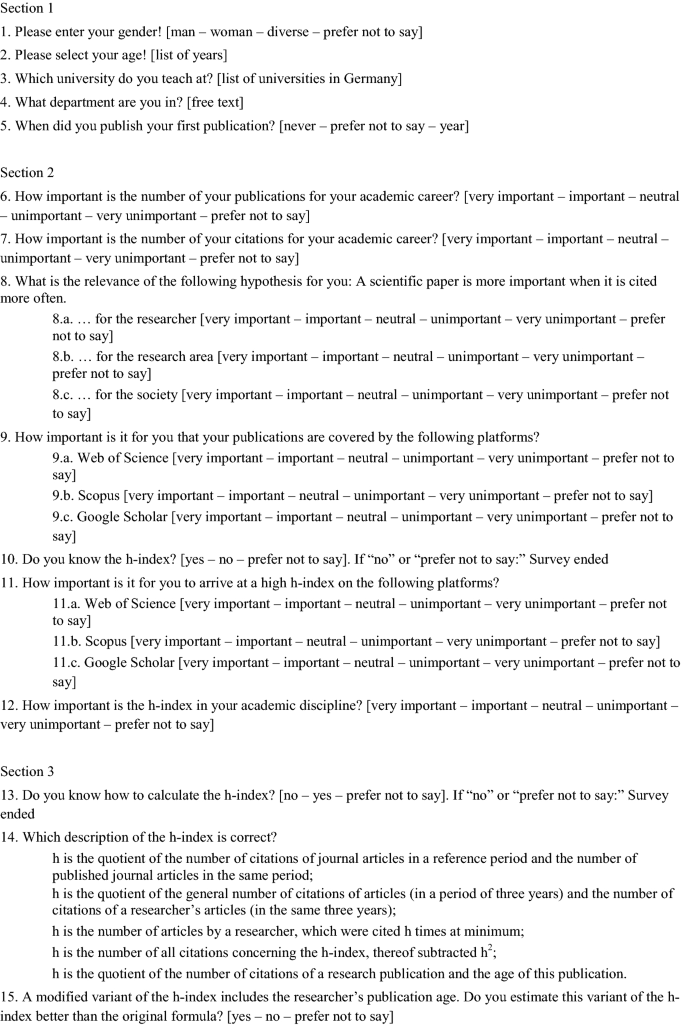

Online survey

Online-survey-based questionnaires provide a means of generating quantitative data. Furthermore, they ensure anonymity, and thus, a high degree of unbiasedness to bare personal information, preferences, and own knowledge. Therefore, we decided to work with an online survey. As we live and work in Germany, we know well the German academic landscape and thus restricted ourselves to professors working at a German university. We have focused on university professors as sample population (and skipped other academic staff in universities and also professors at universities of applied sciences), because we wanted to concentrate on persons who have (1) an established career path (in contrast to other academic staff) and (2) are to a high extent oriented towards publishing their research results (in contrast to professors at universities of applied science, formerly called Fachhochschulen , i.e. polytechnics, who are primarily oriented towards practice).

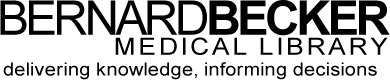

The online questionnaire (see Appendix 1 ) in German language contained three different sections. In Sect. 1 , we asked for personal data (gender, age, academic discipline, and university). Section 2 is on the professors’ personal estimations of the importance of publications, citations, their visibility on WoS, Scopus, and Google Scholar, the h-index on the three platforms, the importance of the h-index in their academic discipline, and, finally, their preferences concerning h-index or m-index. We chose those three information services as they are the most prominent general scientific bibliographic information services (Linde and Stock 2011 , p. 237) and all three present their specific h-index in a clearly visible way. Section 3 includes the knowledge test on the h-index and a question concerning the m-index.

In this article, we report on all aspects in relation with the h-index (for other aspects, see Kamrani et al. 2020 ). For the estimations, we used a 5-point Likert scale (from 1: very important via 3: neutral to 5: very unimportant) (Likert 1932 ). It was possible for all estimations to click also on “prefer not to say.” The test in Sect. 3 was composed of two questions, namely a subjective estimation of the own knowledge on the h-index and an objective knowledge test on this knowledge with a multiple-choice test (items: one correct answer, four incorrect ones as distractors, and the option “I’m not sure”). Those were the five items (the third one being counted as correct):

h is the quotient of the number of citations of journal articles in a reference period and the number of published journal articles in the same period;

h is the quotient of the general number of citations of articles (in a period of three years) and the number of citations of a researcher’s articles (in the same three years);

h is the number of articles by a researcher, which were cited h times at minimum;